#prosumption

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

So at some point in time, I read a post on tumblr about 50 shades of grey and its intersection with fandom culture (i'm pretty sure it was 50 shades), and how it was a successful money grab of the kindle unlimited (idk what to call it) of the time. There were screenshots of Amazon books of dozens of knock offs. And it really got into the ethics of fandom turning main stream trad pub. I think about this post so much but I cannot find it!!!!! If anyone has a link or knows what i'm talking about, please send it to me, I'm begging. I know I've reblogged it before which is the real kicker.

#fandom culture#fandom meta#50 shades of gray#i was trying to explain fandom ethics and culture to a coworker last night#it did not go well#50 shades was the example#and i was trying to draw comparisons of these cycles of things like 50 shades to the romantasy genre#and lbr contemporary romance in general#and she was like bottom line if i enjoyed it then its good#and i was like oh its more complicated than that for me bcuz of the history of the book and how it kinda of exploited fandom#and i completely lost her#understandably so#its very nuanced but i was like if i could just make u read this essay#i did find something called fannish prosumption on a website called society pages which i will def read tomorrow#sigh i want to do an ma in pop culture so bad!!!!!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hatsune Miku - The False Idol and Her Fandom as a Body Without Organs

Hatsune Miku is a Vocal synthesiser, a commercially produced software that comes paired with an illustrated girl as the “performer.” People use this software to create digital performances, borrowing Hatsune Miku’s image and posting them online, where they often evolve as they are circulated. Her image is free to share, adapt and create with - the surrounding “Vocaloid fandom” uses this image and voice to explore and navigate complex and heavy topics, often extremely personal, such as grief, sexuality, depression and relationships. While there are some works in this area, they are lacking in depth and evidence, which is the gap I aim to fill. This study aims to examine the appeal of using Hatsune Miku as a vehicle for these complex representations, looking further at the surrounding fandom. Using semi-structured interviews on participants from fandom sites such as Tumblr, gaining a breadth of qualitative information on their connection to Miku, I am to investigate my hypothesis that the connections between fandom and figure is comparable to that of a Body Without Organs, which in this case, occurs with ease, due to Miku’s freely accessible image, prosumption encouraging background and narrative lacking nature.

Back in April 2024, I was interviewed for an academic paper on Hatsune Miku and the VOCALOID fandom. The author finally shared the finished work with me at the very end of 2024, and I've created a site where you can read the paper in full!

605 notes

·

View notes

Note

Tell me about how the structure of the medium impacts the story 🔫

My brother in Christ, prepare yourself for the most boring essay you could possibly imagine. I'm going to over-simplify a few things here for the sake of Getting To The Point, so bear with me.

I think a good starting place is that DSMP is an example of New Media. The go-to definition most folks use is this one: that New Media are stories told via "communication technologies that enable or enhance interaction between users as well as interaction between users and content." In other words, NM is basically this category of stories made up of convergent elements, which satisfy a multimedia requirement, and are heavily reliant on both participatory fan culture and recent advances in technology that allow creators/audiences to communicate with one another instantly.

There's a couple ways you can understand DSMP as a New Media, but as far as I'm concerned, one of the most interesting is prosumption. The term "prosumption" describes a creative situation where a piece of art is being produced (at least in part) by the same people that consume it; they're both audience and creator. DSMP is a really great example of this phenomenon, because A) it's serial and therefore the CCs had ample opportunity to respond to and engage with the audience's reception of their story; and B) because the chat feature allows CCs to interact directly with their audience during roleplay rather than after the fact. These features, among others, kinda set the stage for DSMP to function as a highly prosumptive piece of media.

In particular, the stuff that interests me is the stuff to do with storytelling convention (genre, perspective, etc) and how prosumption turns all that on its head. There are a number of altercations in DSMP canon where the course of the story is altered because of real-time interactions between the CCs and their chat - particularly times when a CC's chat warns them about events happening at the same time elsewhere in the server. In this kind of scenario, the CCs are static, they can't really leave their own stream. Their viewers, on the other hand, are able to jump between streams and talk to each other to figure out what's happening in the overarching story. When this happens, viewers have choices to make: are they going to tell a CC what's going down on the other side of the server? If so, how are viewers going to communicate those events? Viewers are biased, they directly inform CCs, and the information they divulge (as well as how they divulge that info) goes on to influence CCs' actions and thus the events of the story, to some degree. In my opinion, this is a pretty new and exciting way to prosumptively construct a narrative! Media has always been interactive to some extent (especially serial works), but the interaction being live and in real-time is pretty significant in my view because it can exert unique pressures on a narrative.

Speaking of audience choice, that brings me to the next thing I want to yap about: ergodic storytelling, a term that refers to stories “negotiated by processes of choice, discernment, and decision-making.” For reference, a good non-MCYT example of this would be hypertext fiction, because it's generally characterized by the ability of the interactant (that's the reader, in this hypothetical example) to explore material provided by someone else, either as a kind of conceptual landscape (think setting in a video game), or as puzzle pieces that must be put together in order to give the interaction the "big picture" of the story. Basically, with hypertext fiction, there is a core text (the main document that forms the skeleton of the story) and there are multiple hypertexts branching off of the core text - and whether the reader ends up reading those branches, and in what order, inevitably shapes that reader's perception of the whole story.

So here's where it gets tricky. In the case of DSMP, where is the core text located? Is there any one identifiable core text at all? Or is it more appropriate to consider each individual stream or VOD as its own singular core text, with the related Twitch channels and Youtube recommended in the sidebar being "branches"? Alternatively, if the streams and recordings distributed on the server members’ official channels are the central text in the grand hypertext fiction that is DSMP, then can adjacent spaces where audiences do the work of creating and archiving lore be considered their own story branches? I don't have answers to these questions. No one does. That's part of what makes DSMP exciting.

To translate the above quote out of Academia Hellspeak: in an ergodic story, the audience has agency, but the agency enabled and allowed by the text varies in its intensity and mode. Yes, stories told ergodically necessitate choice — and therefore enable agency, turning the reader or viewer into interactant — but that element of choice doesn't always look the same. Some hypertexts are more choice-reliant than others, or are choice-reliant in different ways. So, rather than being a choose-your-own-adventure story, DSMP is more closely analogous to a story where the audience chooses the perspective through which they view plot developments, in addition to having some influence over how plot developments unfold.

(☝️From a 2021 Polygon article, if you think I sound crazy☝️)

The web of choices DSMP presents to viewers is very complex, even compared to other forms of choose-your-own-adventure game. Because each CC approaches the task of story-creation from their own angle (bringing their own narrative baggage to the writers’ room, so to speak), those shifts in perspective this Polygon article describes often also constitute shifts in genre. For instance, cc!Wilbur brought his music production experience and interest in musical theater to the server, cited operas and stage musicals as some of his main inspirations; and accordingly, much of c!Wilbur's most crucial arcs observably draw from those sources. When you watch a c!Wilbur stream, you’re watching a story about statecraft, about revolution, about the triumphs and tragedies of ego that play out during the process of nation-building. On the other hand, cc!Quackity has repeatedly identified Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul as his primary influences; accordingly, his RP character’s story is closer to a piece of gritty prestige television in some places (especially LN series). Unlike with c!Wilbur, a lot of c!Quackity's tension does not revolve around a romanticized fantasy of revolution but around more personal conflicts: securing your place in a new regime, navigating exploitation as both exploited and exploiter, etc. In terms of both plot beats and character arcs, Wilbur and Quackity’s respective storylines embody many of the genre conventions the content creators are working within.

Moreover, a shift in genre often entails a shift in style or mode. Because cc!Wilbur was heavily inspired by musical theater, the presentation style of his character’s storyline is correspondingly both theatrical (i.e. only loosely scripted, nearly always televised live, and improv-heavy) and musical (featuring multiple instances of Wilbur singing in-character ballads and anthems.) On the flipside, Quackity’s streams (especially the later ones, since I'm mostly focusing on Las Nevadas era here) demonstrably mimic the prestige TV shows the CC draws his inspiration from, with lore sessions being pre-recorded rather than televised live, featuring distinctive sonic and visual aesthetics popularized by neo-Western thriller dramas. So, where a piece of media like DSMP is concerned, shifts in perspective entail shifts in genre, which in turn entail pronounced shifts in style. I don't think it's an exaggeration to say it's an entirely new story depending on which character the viewer decides to follow. In that regard, what initially appears to be a single choice (whose perspective to watch a plot event through) has the power to determine a wide array of other elements, as viewers’ responses to the options presented to them will decide the overall tone of the section of the story they're about to watch.

While I think the genre-switching is genuinely super cool, lately I'm a lot more interested in perspective-switching and how it's related to viewer empathy. One side-effect of DSMP being televised live is that yes, you can watch a plot event from 30+ different POVs, but you can't watch every POV live. Typically, you either have to switch between multiple streams, or you need to pick one streamer to watch live and maybe later you'll watch other characters' POVs as you see fit. This has an impact on your perception of how that plot point went down because watching something live feels very different from watching something after-the-fact. I haven't done study on this, so what I'm about to say is mostly conjecture, but I wouldn't be surprised if viewers felt greater empathy for (and greater degrees of kinship with) characters whose POVs they watched live.

The choice of which character to follow also has observable impacts on other kinds of narrative conventions (who is the main character of DSMP? the boring answer is c!Dream because the server's named after him, but the real answer is the protagonist is whoever's POV you watched most of the major plot events through) but to be honest, those questions don't interest me as much.

So, going back to perspective and empathy. I think viewers' reactions to Exile are a really solid way of exemplifying the thing I'm trying to say, so this is the part of the yapping where we gotta bring up the dreaded Exile discourse.

Even though the Exile VODs are available and new viewers can go back and watch them, those viewers experience the Exile arc in a way that is fundamentally different from the experience had by viewers who had to wait in between updates as the videos were being streamed serially in real-time. I would argue that viewers who were “present” during the whole arc noticeably felt the brutality of c!Tommy’s treatment to a greater degree, because the audience was effectively forced to sit in exile alongside Tommy’s character - stewing in anxiety, looking forward to the possibility of appearances from other characters, and living in fear of Dream’s next visit, etc etc. Obviously you could also make this point using c!Dream's time in Pandora as an example, but I'm using Exile here because I've actually seen a lot of fans bring this up when discussing the arc: "people who didn't watch live Don't Get It," "the reason newer fans don't see Exile as scary is because they didn't have to watch it live," that sort of thing. And while I have certain qualms with some of the implications here, I do think these are really fascinating responses! These sorts of responses show that viewers consciously perceive their viewing experience as having been fundamentally different from others' based on a temporal element that's unique to serial fiction!

This instance of a divergence in collective fan experience is an example of choice being rendered unavailable to viewers by virtue of the story’s structure and means of distribution; audience members who happen to accidentally miss streams or who begin following the story after major events have occurred will never be able to engage with and witness those events as LIVE viewers, merely as retrospective ones. They don’t get to make that choice, but they do get to make choices about which perspective (and therefore genre) they get to experience the story through. So it follows that each aspect of DSMP, a semi-ergodic story, can be categorized as either ergodic or non-ergodic, and whether a particular storytelling element is ergodic can change depending on WHEN the viewer began tuning in to the story.

I have a lot more shit to say (shocker) but I'm gonna cap it here for now. Though I do want to add that this is kinda why I have a lot of patience for the crazy diversity of interpretation you tend to get in DSMP fandom. If you took a random sample of fans and asked them what they think of various arcs, characters, and plot events, chances are they would all have fairly different things to say. To me, that's a feature, not a bug. Obviously I have my own opinions, and obviously I do think it's possible for a given interpretation to be "bad," i.e. not grounded in the text - but I have a lot more patience for it here, in a fandom where agreeing on what "the text" EVEN IS presents a challenge. We can't all agree on who the main character is, so I don't ever expect us to agree on more nuanced questions of theme and conflict resolution in the narrative. Again, that's a feature, not a bug. I don't think it was ever possible to reach a consensus with a piece of media like DSMP because of how inextricable the audience is from the story.

#dream smp#tw cc!Wilbur mention#in case anyone wants to avoid that right now for obvious reasons#sorry for yapping for so long but I did warn you#also sorry for letting this sit in my inbox for ages#I got so busy and it was hard finding a spare moment to sit down and collect my thoughts#dsmp exile arc#asks#long post

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

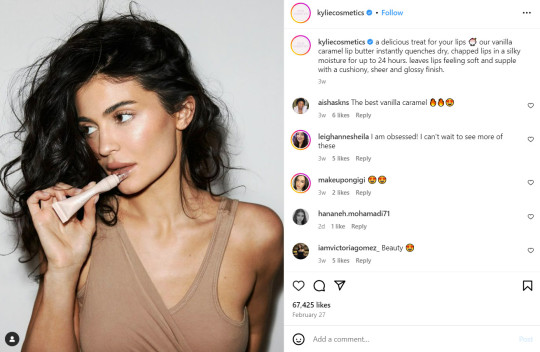

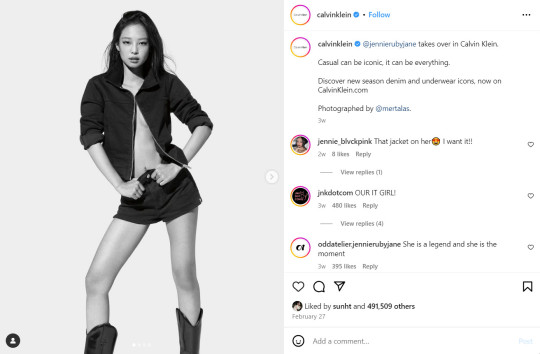

Week 8: Digital Citizenship and Health Education: Body Modification on Visual Social Media

Setting the scene

Scroll through Instagram for five minutes and you will notice a striking sameness: sculpted abs, pore‑less skin, and carefully posed selfies. These recurring “aesthetic templates” have become cultural scripts that teach users how a “successful” body should look online. While such curation feels routine, scholars warn that it represents a new form of identity work that merges marketing logic with personal expression (Marwick ,2015). This post explores how aesthetic templates circulate, why they matter for public health, and what can be done to resist their more harmful effects.

Aesthetic Templates & Micro-celebrity Labour

Micro‑celebrity culture incentivises ordinary users to manage themselves like brands, trading constant visibility for imagined influence. On image‑centric platforms this involves intensive “aesthetic labour”: shooting in flattering light, adopting signature poses, and editing away perceived flaws to fit the prevailing template (Carrotte, Prichard & Lim ,2017). The process is not trivial; it represents unpaid promotional work in which users become both the worker and the product, blurring leisure and labour in ways that benefit platforms (Ritzer & Jurgenson ,2010).

Body Image Dissatisfaction & Malaysian Youth

The psychological toll of template chasing is increasingly documented. Fardouly et al. (2015) found that social comparisons on Facebook heightened young women’s body dissatisfaction and negative mood within minutes. Closer to home, Khodabakhsh and Chan (2020) surveyed 316 Malaysian youths and reported a significant negative correlation between heavy social‑media use and body image evaluation. Their findings echo international evidence linking highly curated feeds with identity dissonance and, in severe cases, body dysmorphic disorder (BDD).

Gendered Pornification and Visibility Asymmetries

Templates are highly gendered. “Fitspiration” images aimed at women often combine fitness tropes with sexualised framing an aesthetic Drenten and Gurrieri (2019) label “porn‑chic”. Men’s visibility, in contrast, is rewarded when posts emphasise athletic competence over overt sexuality, reinforcing hegemonic masculinity while marginalising queer male expression. Such asymmetries show that template adoption is not simply personal choice; it is shaped by platform logics that privilege certain identities and desires over others.

Public Health Campaigns

Well‑intentioned public‑health campaigns sometimes repurpose these same templates to attract attention. #Movember’s moustache selfies, for example, successfully mobilise peer‑to‑peer diffusion but also risk reinforcing narrow ideals of male appearance. Perloff (2014) cautions that without critical media literacy, campaigns can unintentionally normalise unhealthy standards even as they promote wellness, reproducing the very anxieties they aim to solve.

Algorithms, Prosumption & Feedback Loop

Platform algorithms amplify high‑engagement visuals, meaning polished bodies receive more exposure and, in turn, set new norms for what “performs” well online. Users respond by investing even more labour into conforming templates to gain visibility,a classic prosumption feedback loop (Ritzer & Jurgenson 2010). Left unchecked, this loop externalises psychological costs onto users while internalising ad revenue for platforms.

Healthier Digital Cultures

Resistance is possible. Evidence suggests that exposure to body‑positive or diverse‑sized content can buffer negative effects, improving mood and satisfaction (Brown & Tiggemann 2020). Researchers therefore advocate a multi‑level strategy: (1) integrating critical digital‑literacy modules into school curricula; (2) incentivising influencers to disclose edits and endorse diverse bodies; and (3) pushing regulators to demand algorithmic transparency. For practitioners, embedding alternative visuals, (e.g., unfiltered “Instagram vs Reality” sliders or TikTok #BodyPositivity compilations) , can re‑balance feeds and model more attainable standards.

Conclusion

Aesthetic templates operate at the intersection of culture, commerce and code. They frame bodies as projects, circulate through micro‑celebrity labour, and can undermine mental health,yet they are not immutable. By combining evidence‑based literacy, platform accountability and grassroots creativity, educators and users alike can reclaim the feed for healthier, more inclusive representations.

References

Brown, Z & Tiggemann, M 2020, ‘Attractive celebrity and peer images on Instagram: Effect on women’s mood and body dissatisfaction’, Body Image, vol. 33, pp. 138–143.

Carrotte, ER, Prichard, I & Lim, MSC 2017, ‘‘Fitspiration’ on social media: A content analysis of gendered images’, Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 19, no. 3, e95.

Drenten, J & Gurrieri, L 2019, ‘Sexualized labour in digital culture: Instagram influencers, porn chic and the monetization of attention’, Gender, Work & Organization, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 12–30.

Fardouly, J, Diedrichs, PC, Vartanian, LR & Halliwell, E 2015, ‘Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood’, Body Image, vol. 13, pp. 38–45.

Khodabakhsh, S & Chan, SL 2020, ‘Relationship between social media usage and body image evaluation in Malaysian youth’, Malaysian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 13–21.

Marwick, AE 2015, ‘Instafame: Luxury selfies in the attention economy’, Public Culture, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 137–160.

Perloff, RM 2014, ‘Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: Theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research’, Sex Roles, vol. 71, pp. 363–377.

Ritzer, G & Jurgenson, N 2010, ‘Production, consumption, prosumption: The nature of capitalism in the age of the digital “prosumer”’, Journal of Consumer Culture, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 13–36.

#mda20009#Movember's moustache#body modification#gender representation#media literacy#youth mental health#social media culture#body positivity

0 notes

Text

Week 10 – Playing Together: Gaming Communities, Streaming Culture, and Digital Belonging

During this week’s guest lecture, Taylor Hardwick discussed digital gaming communities and how these communities arise from play, personal identity, and technology. Today, people are recognising that games help people bond, become engaged, and share their knowledge.

An important idea that caught my attention was “knowledge communities”. For Jenkins (2006), these are called transient communities created by fans based on their interests and feelings. Here, people discuss the game by swapping strategies, trading thoughts on its plot, and forming friendships online. The main strength of these communities is that both playing and making things together keeps them going.

Among other things, Hardwick pointed out that Twitch and YouTube Gaming have made gaming a sport people often watch instead of play. Through streaming, active viewers are able to connect very closely to their favorite streamers. They are no longer only a source of entertainment; they also turn into digital “third places” for people to meet informally.

But the lecture made sure to discuss some of the problems in gaming culture. The image of the usual gamer as a white man prevents everyone from being fully included both in sports and everyday gaming activities. It fits with how scholars explain gender conflict and the toxic meaning of being a “gamer” (Consalvo, 2012). Although games are for anyone, some people still feel like they are not accepted by others.

It also talked about how people can modify games with modding to help them create unique experiences. This trend clearly shows that digital culture has moved from having consumers to people who actively rework and change the content they consume (Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010). It proves that gaming communities involve following the rules, but they mostly focus on changing them.

All in all, I realized that playing videos games is more than just finding a chance to escape or compete. It involves people, new ideas, and important reflection. Instead of only using online communities, we should help make them more safe and for everyone to benefit.

References (Harvard style):

Consalvo, M., 2012. Confronting toxic gamer culture: A challenge for feminist game studies scholars. Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology, 1. Available at: https://adanewmedia.org/2012/11/issue1-consalvo/

Jenkins, H., 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: NYU Press.

Ritzer, G. & Jurgenson, N., 2010. Production, consumption, prosumption: The nature of capitalism in the age of the digital ‘prosumer’. Journal of Consumer Culture, 10(1), pp.13–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540509354673

Sotamaa, O., 2010. When the Game Is Not Enough: Motivations and Practices Among Computer Game Modding Culture. Games and Culture, 5(3), pp.239–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412009359765

0 notes

Text

Why Are We So Obsessed with Bodies and Beauty?

Our obsession with bodies isn’t just skin deep - it’s shaped by evolution, culture, capitalism, and code. From ancient survival instincts to today’s Instagram filters, our understanding of beauty is constantly constructed, surveilled, and sold back to us.

🧬 Evolutionary Psychology

From a biological standpoint, humans are drawn to traits associated with fertility and health - symmetry, clear skin, and certain body ratios. This is rooted in evolutionary psychology, where beauty signals reproductive fitness (Etcoff, 1999).

But in the age of TikTok and face filters, this instinct gets hijacked. Platforms amplify hyper-idealized versions of beauty, shaping what we think is attractive through repetition and algorithmic reward. As Carah and Dobson (2016) describe, this results in algorithmic hotness, where attractiveness isn’t just about looks - it’s about platform-optimized performance.

Feminist Body Theory: The Body as Text

Feminist scholars like Sandra Bartky (1990) and Susan Bordo (1993) argue that the body is a social construct, shaped by discipline and power. What’s considered “beautiful” or “normal” is written by dominant cultures - and upheld by industries, media, and now... platforms.

Postfeminist culture rebrands sexualized self-presentation as empowerment, but in practice, it often demands unpaid aesthetic labor (Drenten et al., 2020). So, your body isn’t just you - it’s content, currency, and capital.

#ThatGirl TikTok. Aesthetic wellness? Or a soft filter over class, privilege, and disordered eating?

youtube

Platformization and Prosumption

As theorized by Theocharis et al. (2022), platform affordances (like likes, filters, and discoverability) reshape how we perform online. Beauty becomes a data-driven project - curated for maximum engagement. Prosumption (Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010) explains how we’re both producers and consumers - creating content that simultaneously expresses identity and feeds the platform's profit model. Your mirror selfie? It’s not just self-expression; it’s monetized microcelebrity.

Sexualized Labour & Digital Capital

Drenten et al. (2020) introduce the idea of sexualized labour, where influencers, especially women, strategically blend emotional work, aesthetic work, and sexual appeal to maintain visibility and income.

They also define connective labour - the hustle of staying relevant through hashtags, tags, and engagement. It’s not just looking good - it’s doing good (for the algorithm), 24/7.

🧠 Beauty is also a talent!

But hey, let’s not throw our skincare routines out with the critical theory. There’s also an upside to our collective obsession with beauty. When channeled positively, the pursuit of aesthetics can motivate people to live healthier, care more about themselves, and embrace self-improvement. As the trend of “beauty from within” grows - think: gut health, mental clarity, clean eating - it shows that the definition of beauty is slowly expanding beyond just the surface.

This aligns with Choi and Cristol’s (2021) notion of digital citizenship, where participating in online beauty conversations can also mean sharing health knowledge, supporting wellness communities, and building body-positive spaces. Even the pressure to “look good” can push people to exercise, sleep better, drink more water, and explore holistic well-being - not just for the algorithm, but for themselves. So yes, beauty culture can be messy, but it can also be a gateway to personal growth, health education, and even joy.

💅 Is your beauty routine just for the ‘gram, or does it feed your soul too? Drop your fave “feel-good” habit or wellness creator in the comments - because beauty is better when it’s holistic.

References

Bartky, S. L. (1990). Femininity and domination: Studies in the phenomenology of oppression. Routledge.

Bordo, S. (1993). Unbearable weight: Feminism, Western culture, and the body. University of California Press.

Etcoff, N. (1999). Survival of the prettiest: The science of beauty. Anchor Books.

Carah, N., & Dobson, A. S. (2016). Algorithmic hotness: Young women’s “promotion” and “prosumer labor” on social media. Social Media + Society, 2(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116672885

Theocharis, Y., Barbera, P., Fazekas, Z., & Popa, S. A. (2022). Platform affordances and political participation: How social media reshape political engagement. West European Politics, 46(4), 788–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2087410

Drenten, J., Gurrieri, L., & Tyler, M. (2020). Sexualized labour in digital culture: Instagram influencers, porn chic and the monetization of attention. Marketing Theory, 20(4), 435–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593119826141

Ritzer, G., & Jurgenson, N. (2010). Production, consumption, prosumption: The nature of capitalism in the age of the digital “prosumer”. Journal of Consumer Culture, 10(1), 13–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540509354673

Choi, M., & Cristol, D. (2021). Digital citizenship with intersectionality lens: Towards participatory democracy driven digital citizenship education. Theory Into Practice, 60(4), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2021.1987094

1 note

·

View note

Text

Reader

Bowman N. D., Ahn S. J., and Kollar L. M. M., 2018. The paradox of interactive media: The potential for video games and virtual reality as tools for violence preventation. Frontier in Psychology, 9, p.1188. Available at https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/communication/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2020.580965/full (Accessed 12 October 2024)

This article is a great example of how immersive and interactive media tools such as VR&AR and gaming can be used in a good way prevent violence and such behaivors. Although, media always link up with agression and sensitive content, the authors explore how interactive media may have the effects which are just the opposite and serve in a way to reduce violent behaviors. By allowing the users witness the consequences of violence with multiple simulations, it might impact common sense and knowledge through such actions. The research recommend that with bespoke designs gaming environments and VR&AR could become important asset for the public awareness through violence and crime.

Duong Q. H. T., (2022) 'Digital transformation in education: A comprehensive review' Education and Information Technologies, 28(3), pp. 1-22. Available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10639-022-11313-z (Accessed 12 October 2024)

The article 'Digital transformation in education'' focuses on how important interactive media started to be in schools. Especially, how does it reflect learning outcomes and benefits is getting quiet remarkable. What I geniunely find interesting about this essay is that how interactive media make the learning system more fun, immersive and long-lasting in the long run. Apperantly, tools like, simulations, VR&AR, online platforms where the users do things together and multi-media programmes are able to encourage deeper understanding and dynamic feedbacks in learning environment. It seems to me that it gives an idea of what the future education system should be like for the students if we keen to get better outcomes.

Do, T., Nguyen, T. and Nguyen, D., (2022) The effect of media literacy on effective learning outcomes in online learning. Education and Information Technologies, 27, pp.10093-10112. Available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10639-022-11313-z (Accessed 12 October 2024)

In this academical study, the findings show that how the media inlfluence online education system in a good way in Vietnam. In the text, functional consumption, critical consumption, functional prosumption and critical prosumption were observed. In the end, the findings were shown that critical consumption is the most effective aspect that impact importance of creating and perceived learning. Additionally, they were illustrated that the education system with various of media tools is actually support online learning system. According to this article, media literacy is significant for obtaining better learning outcomes. Especially, in my opinion it may benefit distant learning and digital context greatly.

García-Casaus, M., Lampropoulos, G., & Arias, M. (2024) 'Impact of Gamification on Motivation and Academic performance: A systematic review', Education Sciences, 14(639). Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7102/14/6/639 (Acessed 17 October 2024)

The article 'Impact of Gamification on Motivation and Academic performance: A systematic review' illustrates important insightful informations related with how gamification elements are able to influence motivation and learning objectives in a good way. In my opinion it makes learning fun and particularly stronger as it convert the classroom environments something more collaborative and dynamic. This approach could be a milestone for overall education system to make the traditional methods more contemporary and interesting. Last but not least, the article also underscores that in this way student performances across various of subjects could be influenced or even changed for good in a positive way.

Griffey, J., 2020. Introduction to Interactive Digital Media: Concept and Practice. 1st ed. NewYork: Routledge.

Introduction to Interactive Digital Media: Concept and Practice by Julia Griffey is a book that transfers the fundamentals of interactive digital media. Especially for the people who are interested in interactive digital media and have a lack of informations, its a very important source because it shares basic datas in relation with coding, interface design and multimedia. I think it's a very plus for new learners that get the essentail informations from both theory and application in such a book. Overall, it's a book that must to have for those who are seeking to learn creating user friendly digital experiences.

Majewska, D., (2017). Interactivity in social media: educational potential. International Journal of Psycho-Educational Science, 6(3), pp.56-61 Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1254649.pdf (Accessed 13 October 2024)

The essay focus on some terminologies such as constructivism and connectivism which uses education as a social artefact that conduct through interaction with others in digital platforms. I think it's a great idea to use social media platforms as an object where students dynamicly participate, exchange informations and construct communities. It could lead users to meaningful learning experience as well as extend learning phase beyond classrooms and allow to global interactions. The study illustrates by making social media platforms more interactive and viable, it's possible to reshape the education system in a better way. It also underscore the significance of social engegament and creating a worldwide network within these social platforms. In my opinion, it could be very convienent idea to bring people together from all around the world and share knowledge as easily as possible.

Perez, E., Manca, S., Fernandes-Pascual, R., McGuckin, C. (2023) 'A Systematic Review of Social Media as a Teaching and Learning Tool in Higher Education: A Theoratical Grounding Perspective 28(9), pp. 11921-11950 Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368882072_A_systematic_review_of_social_media_as_a_teaching_and_learning_tool_in_higher_education_A_theoretical_grounding_perspective (Accessed 17 October 2024)

The article explores how social platforms like Facebook, Twitter,Tiktok and Youtube so on can be used in higher education (post graduate or Phd programmes) to assist students to learn the objectives as effective as possible. In addition to this, the authors also thinks that to make social media platforms feasible and more secure in regards of education, it should contains more teaching methods that encourage cooperation and dynamic learning. In my opinion its possible to convert and changed in a way them as a learning environment by creating educational aspects inside of the apps which provides more secure and convienient for education dynamics.

Podara, A., Giomelakis D., Nicolaou C., Matsiola M., Kostakis R. (2021). Digital storytelling in cultural heritage: Audience engagement in the interactive documentary New Life. Sutainability, 133, p.1193 Available at https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/3/1193 (Accessed 13 October 2024)

The article indicates one of the many advantages of using interactive media as a way to keep the audience motivated and more interested. It's a great example of interactive documentaries where the users create a personal connection to the content by using multi media and interactive elements. The article focused on a Greek interactive documentary called ''New Life'' which includes a strong story behind and efective promotion and dynamic updates based on target audience. It makes me amazed that how interactive media even make the cultural content more accesible and engaging. This demonstrates that digital storytelling could make learning a lot personal and unforgettable by involving the audience.

Tussyadiah, I. P., Park, S., & Fesenmaier, D.R. (2021) 'Interactive advertising: the role of interactivity in shaping costumer experiences with online ads p. e0258936 Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1254649.pdf (Accessed 17 October 2024)

Interactive advertising is becoming a thing day by day. This is because it attracts a lot of user's attention more than anything which makes the best way to sell the goods for companies. The article illustrates how interactive adds influence people minds to remember them in an efficient way. They study shows when the advertisements more interactive, they hold people's attention better and permanent impression leading to better recall. I think the more interactive elements exist in the campaings, more engaging and effective feedbacks the companies likely to get which is quiet amazing how interactive media impact marketing all over.

Zhou Q., Zhang H., Li F., (2024) 'User Engagement with Interactive Media: A Communication Framework Available at https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7102/14/6/664 ( Accessed 17 October 2024)

The article 'User Engagement with Interactive Media: A Communication Framework' demonstrates interesting perspective through interactive media in which how can it seek and hold users attention. With concentrating on visuals and tactile elements, it shows how these experiences are able to create stronger user engagement. In my opinion, this idea makes a lot of sense as they are very important for upgrading user experiences drastically. The framework they offer is convinient for the fields like entertainment and education where holding users attention is matter. However, although the study focus on sensory simulation, it could have also explored more on how preferences and environment might be able to influence engagement levels seperately based on each user.

0 notes

Text

Week 7: Digital Citizenship and Health Education: Body Modification on Visual Social Media

With the development of technology and communication, people today have many opportunities to access new knowledge and gain new experiences in an easier and more positive way. Those changes come not only from thinking, perception or lifestyle but also from appearance. The rapid development of media and society also creates more favorable conditions for people with high needs for beauty to enhance their beauty through body modification and body image building.

According to Bradley University, we tend to think of the human body as simply a product of nature. However, our bodies are also products of culture. This shows that what we show on our appearance not only shows our personality and personality, but also shows the cultural features we live in or have experienced. Building body image also helps us not only express our personality or opinions and ideas about something, but also build a cultural community like us. In today's times, cosmetic surgery has become familiar to everyone as the need for beauty is growing and the economy is growing to meet those needs. Cosmetic surgery is the use of human technology and techniques on one's body to transform and change them as desired. Although cosmetic surgery is an inevitable result of the development and growing beauty needs of many people, it is also a topic that is always discussed today.

While some say it can improve self-esteem and combat negative body image. Others see surgical intervention as a sad indictment of a culture with rigid and narrow notions of beauty - a culture that values youth, sexuality and physical appearance over is experience, character and nature (Jeffreys 2000). Critics also note the potential risks associated with cosmetic surgery. In addition to the risk of post-operative infection and other surgical complications, a recent study revealed a correlation between cosmetic surgery, substance abuse, and suicide (Lipworth, 2007). The rapid development of social networking platforms also makes building self-image more important than ever. Building a good image on anfy platforms also creates many influencers related to many topics such as sports, beauty and even sex work. The rise of digital platforms has blurred the lines between consumers and workers, creating a phenomenon known as “prosumption.” (Büscher & Igoe 2013; Ritzer & Jurgenson 2010 cited in Drenten et al. 2020). The development of the sex industry gives many people the opportunity to approach more sensitive issues, which can help people pay more attention to issues such as sex education or sexual safety. But there needs to be selection and control. With social networking platforms becoming increasingly popular and without age restrictions, harmful information can have a negative impact on underage users or children when using social platforms. Therefore, these digital platforms need to demonstrate their ability to play a role in controlling sensitive information and content as well as having policies for users and sensitive content. feelings related to sex, violence, ... The actions of anfy platforms not only help ensure user safety, but also help classify the content and topics necessary to build more active and independent communities.

References:

Drenten, J, Gurrieri, L & Tyler, M 2020, “Sexualized labour in digital culture: Instagram influencers, porn chic and the monetization of attention,” Gender, work, and organization, vol. 27, no. 1, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford, pp. 41–66.

Bradley University, Body Modification & Body Image.

https://www.bradley.edu/sites/bodyproject/disability/modification/

0 notes

Text

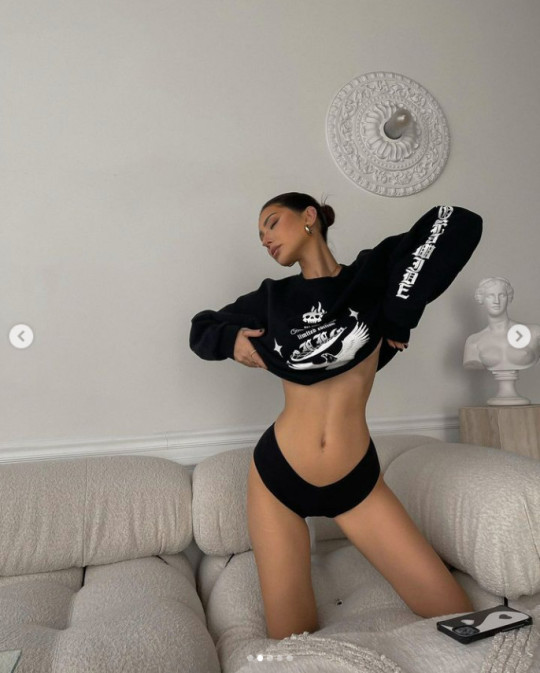

Week 7: Aesthetic Labor

Prosumers

The emergence of the prosumer concept facilitated by digital technologies has led to the fusion of consumption and production (Dujarier, 2014), evident in the widespread proliferation of user-generated content online (Bonsu & Darmody, 2008).

This phenomenon raises inquiries into the intersection between prosumption and sexualized labor, particularly on platforms like Instagram, where the monetization of prosumer labor heavily hinges on capturing attention in the "attention economy" (Davenport & Beck, 2001). Notably, predominantly women influencers shape cultural norms and endorse products on Instagram without commensurate compensation, often conforming to heteronormative standards of attractiveness and femininity, thereby presenting highly sexualized self-representations. This trend aligns with the phenomenon termed "porn chic," where elements of commercial pornography permeate mainstream culture, influencing perceptions of female desirability (Tyler & Quek, 2016).

The convergence of pornographic imagery with non-pornographic media, facilitated by digital technologies, further contributes to this trend (Attwood, 2011). Additionally, within contemporary digital culture, the act of taking selfies is often interpreted as a manifestation of sexualized labor, with women frequently presenting themselves online in highly sexualized ways to adhere to conventional beauty ideals (Carrotte, Prichard & Lim, 2017). Termed "pornification", this phenomenon involves the portrayal of a heteronormative display of sexuality or a 'porn chic' aesthetic, predominantly targeted towards a male audience. Fontenelle (2015) suggests that the prosumption reinforces existing power dynamics by perpetuating heteronormative advertising models, with female influencers positioning themselves as objects alongside the products they endorse, emphasizing bodily curves and other enhanced features associated with femininity. Many successful Instagram brands adopt aspects of the pornification template, emphasizing enhanced features and exaggerated femininity, including accentuated lips, jawline, cheeks, waist, and buttocks.

Sexualized labor

Sexualized labor, defined as work associated with sexuality, sexual desire, and pleasure (Spiess & Waring, 2005), emerged from the need to understand how employee corporeality and sexualization impact emotional and aesthetic labor. Two main conceptualizations of sexualized labor are drawn upon: the “conceptual double shift” (Waehurst & Nickson, 2009, p. 385), transitioning from sanctioned to strategically prescribed employee sexuality, and the process linking work with sexual pleasure. Emotion, aesthetics, and sexualization underpin the performance of sexualized labor, where emotional labor involves managing feelings for wage exchange (Hochschild, 1983, p. 7), and aesthetic labor incorporates workers' embodied capacities to evoke affect in customers (Entwistle & Wissinger, 2006). The notion of sexualization remains ambiguous, encompassing sexual appeal and employee-driven sexualization. Distinguishing between sexualization and healthy sexuality is crucial, as sexualization often involves objectification and degradation, creating tensions in understanding the term 'sexualized' in the context of labor (Drenten, Gurrieri & Tyler, 2019, p. 45). Hopefuls, aspiring influencers on social media, perform sexualized labor without monetary compensation, seeking brand affiliation and follower attention. They adopt a consistent 'porn chic' aesthetic (Hall & Bishop, 2007), emphasizing body-highlighting poses and upbeat captions, contributing to the digital economy unrecognized.

Boasters participate in sexualized labor without receiving direct monetary compensation, relying on informal brand connections for credibility (Drenten, Gurrieri & Tyler, 2019, pp. 52-53). They showcase products in their content, skillfully managing heightened visibility and potential harassment. Boasters frequently receive branded freebies, product trials, and coupon codes, all aimed at promoting external brands but lacking in substantial monetary compensation for the influencer.

Engagers, formally affiliated with external brands, perform sexualized labor for monetary compensation, endorsing products through staged, professionally captured images (Turley & Moore, 1995).

Boosters market their own products using porn-chic aesthetics, engaging in ongoing conversations with followers while driving traffic to external e-commerce platforms (Rich, 1980).

Performers monetize their online presence by offering access to themselves as commodities, redirecting followers to external platforms for personalized interactions for a fee, despite challenges in controlling and protecting their digital content (Drenten, Gurrieri & Tyler, 2019, pp. 58-60).

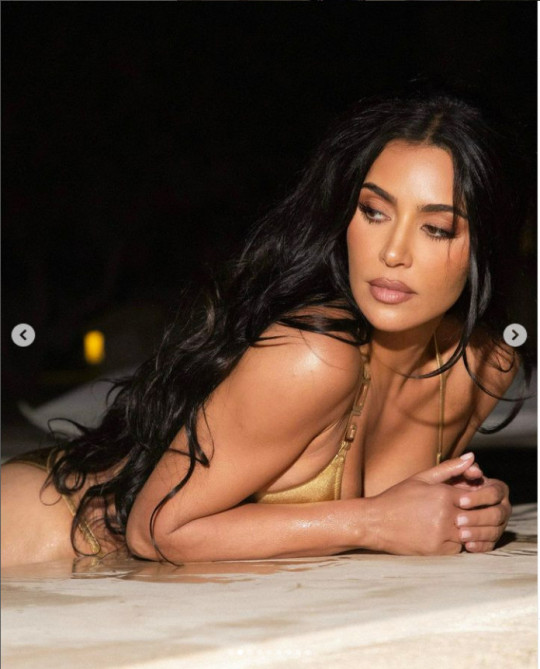

“Body heat” on social media

The concept of "body heat" on social media encompasses both conforming to visual standards of "hetero-sexy" through body production and using an attractive body to influence others (Dobson, 2015). Social media platforms rely on users' curation of "hot" body images to regulate attention flows, especially leveraging hot female bodies in promoting nightlife events. User interactions generate data that informs algorithmic procedures, which learn to prioritize hot female body images due to their profitability. Consequently, naturalized assumptions about gendered desire become embedded in social media platforms' procedural choices.

Scholarly attention to girls' and young women's online identities exceeds that of young men's, with research focusing on their identity constructions and self-branding (Brandes & Levin, 2013). The internet, perceived as a space for challenging normative feminine identities, offers opportunities for empowerment but also involves navigating complex processes of digital identity production (Banet-Weiser, 2012). Social media platforms reflect a political economy of gendered visual images, privileging certain bodies capable of generating affective engagement and profit, while algorithmic media platforms reinforce conventional standards of attractiveness (Carah & Dobson, 2016, p. 3). Promo work in nightlife involves extensive reconnaissance practices focused on registering attention and affect generated by attractive bodies on social media, reflecting vernacular theories of the "male gaze" (Mulvey, 1989) and highlighting how platforms mobilize bodies for attention and affective exchange. "Hotness" operates as both gendered visual characteristics and an ability to influence others, shaping online and offline interactions (Carah & Dobson, 2016, p. 7). Female bodies take center stage in algorithmic media platforms, perpetuating gendered encounters influenced by an assumed male gaze but also offering possibilities for social shifts. Analyzing the interplay between media platforms, branding, and gendered experiences illuminates how gender is reproduced in algorithmic media cultures.

Case Study: Kim Kardashian's Instagram posts

Kim Kardashian's rise to fame, despite lacking a discernible talent, has led to her being revered, particularly among teenage girls, for her entertaining persona (Setiawan, 2020, p. 1).

This portrayal of success prompts viewers to aspire to emulate internet celebrities, who often dictate idealized appearances and body images, further normalizing societal norms through Kardashian's influential social media presence (Juntiwasarakij, 2018, p. 555). This process aligns with the concept of media equation, where viewers respond to communication media as if they were real social actors, solidifying the influence of internet celebrities. However, the portrayal of women, especially through sexually appealing images on social media, can result in both empowerment and exploitation, perpetuating the concept of sexualization, where women are solely evaluated based on their sexual appeal (Liss, Erchull & Ramsey, 2010, p. 65). This representation risks dehumanizing women by reducing them to mere sexual objects, reinforcing self-objectification and emphasizing sexual appeal over their intrinsic value as individuals (Rudman & Hagiwara, 1992, p. 87). Kim Kardashian's Instagram posts frequently feature her wearing revealing clothing, emphasizing her sexuality and allure (Amin, 2015, p. 47). This portrayal, coupled with seductive poses, gestures, and strategically chosen attire such as bodysuits and skirts, accentuates specific body parts like breasts, waist, hips, and buttocks, contributing to her sexualized image (Setiawan, 2020).

Kardashian's promotion of her products through this sexualized persona capitalizes on the effectiveness of sex appeal in advertising, particularly in capturing viewer attention (Poorani, 2012, p. 10).

By embodying societal beauty ideals and normative standards of sexuality, Kardashian reinforces her position as a trendsetter and influencer, shaping viewers' perceptions of attractiveness (Overstreet, Quinn & Agocha, 2010, p. 91). This normalization of her sexually stimulating image is facilitated by Kardashian's control and monitoring of her body, including cosmetic surgeries and rigorous fitness regimens, positioning her as both a subject and object in the capitalist system. Viewers, especially female ones, internalize these standards, aspiring to emulate Kardashian's seductive persona, while male viewers respond favorably to the sexual appeal portrayed (Setiawan, 2018, p. 17). However, Kardashian's hyperreal portrayal blurs the lines between reality and constructed beauty ideals, challenging viewers' perceptions of authenticity and reinforcing unattainable standards of beauty (Baudrillard, 1994, p. 11). In short, Kim Kardashian's Instagram posts demonstrate how she conforms to societal norms and the capitalist system by regulating her body and sexuality (Kress & Leeuwen, 2006). Through revealing clothing, cosmetic procedures, and suggestive imagery, Kardashian strives to maintain an idealized appearance for her audience. This commodifies her body and sexuality, reducing her to a sexual object for profit. However, her Instagram portrayal is a distorted simulation, detached from reality (Baudrillard, 1994).

References

Amin, A., 2015. Conflicts of Fitness: Islam, America, and Evolutionary Psychology. Morrisville: Lulu Publishing Services. Attwood, F., 2011. The Paradigm Shift: Pornography Research, Sexualization and Extreme Images. Sociology Compass, 5(1), p. 2011. Banet-Weiser, S., 2012. Authentic: The Politics of Ambivalence in a Brand Culture. New York: New York University Press. Baudrillard, J., 1994. The Precession of Simulacra. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. Bonsu & Darmody, 2008. Co‐creating Second Life: Market–consumer cooperation in contemporary economy. Journal of Macromarketing, 28(4), pp. 355-368. Brandes & Levin, 2013. “Like My Status”: Israeli teenage girls constructing their social connections on the Facebook social network. Feminist Media Studies, Volume 14, pp. 743-758. Carah & Dobson, 2016. Algorithmic Hotness: Young Women’s “Promotion” and “Reconnaissance” Work via Social Media Body Images. Social Media + Society, 2(4), pp. 1-10. Carrotte, Prichard & Lim, 2017. “Fitspiration” on Social Media: A Content Analysis of Gendered Images. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(3). Davenport & Beck, 2001. The attention economy: Understanding the new currency of business. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Dobson, A., 2015. Postfeminist Digital Cultures: Femininity, Social Media, and Self-Representation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Drenten, Gurrieri & Tyler, 2019. Sexualized labour in digital culture: Instagram influencers, porn chic and the monetization of attention. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(1), pp. 41-66. Dujarier, M.-A., 2014. The three sociological types of consumer work. Journal of Consumer Culture, 16(2), pp. 555-571. Entwistle & Wissinger, 2006. Keeping up appearances: Aesthetic labour in the fashion modelling industries of London. The Sociological Review, 54(4), pp. 774-794. Fontenelle, I. A., 2015. Organisations as producers of consumers. Organization, 22(5), pp. 644-660. Hall & Bishop, 2007. Hot bodies on campus: The performance of porn chic. In: Pop‐porn: Pornography in American culture. Westport: Praeger, pp. 57-74. Hochschild, A. R., 1983. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling, Updated with a New Preface. Berkeley: University of California Press. Juntiwasarakij, S., 2018. Framing emerging behaviors influenced by internet celebrity. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 39(3), pp. 550-555. Kress & Leeuwen, 2006. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge. Liss, Erchull & Ramsey, 2010. Empowering or Oppressing? Development and Exploration of the Enjoyment of Sexualization Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(1), pp. 55-68. Mulvey, L., 1989. Visual and other pleasures. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. Overstreet, Quinn & Agocha, 2010. Beyond Thinness: The Influence of a Curvaceous Body Ideal on Body Dissatisfaction in Black and White Women. Sex Roles, 63(1), pp. 91-103. Poorani, A., 2012. Who determines the ideal body? A Summary of Research Findings on Body Image. New Media and Mass Communication, pp. 1-12. Rich, A., 1980. Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence. The University of Chicago Press, 5(4), pp. 631-660. Rudman & Hagiwara, 1992. Sexual exploitation in advertising health and wellness products. Journal Women & Health, 18(4), pp. 77-89. Setiawan, A. R., 2018. Eny Rochmawati Octaviani. Majalah Santri, pp. 15-18. Setiawan, A. R., 2020. Commodification of the Sexuality in Kim Kardashian’s Instagram Posts. Λlobatniɔ Research Society (ΛRS), pp. 1-12. Spiess & Waring, 2005. Aesthetic labour, cost minimisation and the labour process in the Asia Pacific airline industry. Employee Relations, Volume 27, pp. 193-207. Turley & Moore, 1995. Brand name strategies in the service sector. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 12(4), pp. 42-50. Tyler & Quek, 2016. Conceptualizing pornographication. Sexualization, Media, & Society, 2(2), pp. 1-14. Waehurst & Nickson, 2009. Who's got the look?’ Emotional, aesthetic and sexualized labour in interactive services. Gender, Work and Organization, Volume 16, pp. 385-404.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Week 1 - Introduction

Dear, TAs, students, Ms. Good, and unfortunately for some of you, other random visitors:

Welcome to my COMM 3P18 Audience Studies blog. Prepare to be amazed. Through this blog, I will be demonstrating my understandings of the course while also relating its content to my personal audience experiences.

The first thing I would like to do is present the concept of audience. As seen in lecture, audiences and their definition have changed multiple times throughout the years. Audience, as defined in the Merriam-Webster dictionary, takes many forms. It takes the form of: ‘’the act or state of hearing’’, ‘’an opportunity of being heard’’, ‘’a group of listeners or spectators’’, and similarly it takes the form of ‘’a reading, viewing, or listening public���’. As explained by professor Good in lecture, the history of audience, like telling stories around a fire, is not something new. What is brand new, when looking at the timeline of what it means to be an audience, is what we do as an audience now, like social media for example. Social media open a brand new world to audience studies and allows for new definitions of audience.

My point of view as an audience member varies according to the occasion in which I find myself. I used to see myself as member of audiences that was mostly from a consumer point of view. After taking many communication courses, specifically COMM 3P18 Audience studies, I realize that I have been part of different audiences all my life. I am now also able to critically analyze the content I consume. Another main part of my point of view as an audience member is the fact that I do not only consume content, but I also produce content. In our very first class, professor Good talked about the concept of ‘’prosumer’’. According to Halassi, S., Semeijn, J., & Kiratli, N. (2019) in their article ‘’From consumer to prosumer: a supply chain revolution in 3D printing’’, prosumer means someone who participates in the ‘’production as well as consumption’’ (p.201). My blog will be the perfect example of ‘’prosumption’’. As a member of audiences, I consume content, which I then use to produce these blog posts.

A good example of this could be The Seven Deadly Sins, which is a Netflix series that I often watch is a very good example of content that generates a big audience and even prosumption. After watching this series, many fans, including myself, created fan art such as the one below:

In my next blog post, I will be discussing more about John S. Sullivan’s definition of an audience. I will also be further discussing the history and concept of the audience, so make sure you tune in next week!

-Comm King

1 note

·

View note

Note

I'd love to hear your structural hot takes

I already rambled a lot about this here, but alright okay yes I got more. I am here to talk about bullshit and nonsense after all 😤

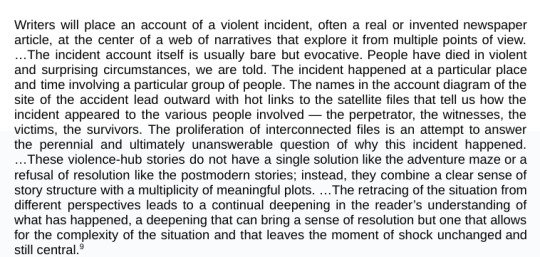

If we're still talking about how DSMP is a prime example of New Media, and various frameworks you might use to understand it as an example of New Media, then I think it could be useful to bring up the concept of the violence hub.

Before I get into all that I need to define another term: rhizomatic storytelling, which means a narrative that is decentralized, nonlinear, and intricately networked. Does DSMP fit into this category? I would say so, even though it doesn't necessarily fulfill all criteria. It's definitely decentralized (I've already talking a bit about how it's difficult to pin down the parameters of the "core text" when it comes to MCYTRP) and it's definitely a network of little stories coming together to form a cohesive(ish) narrative. But one thing DSMP isn't is nonlinear. It's a very linear story, in the same way that professional wrestling (which is famously fictionalized) is very linear. It's been pointed out by fans that the storylines in pro wrestling pass at the same rate as time passes in the real world - which is pretty unique! You can't say that about most stories, even most forms of serial fiction! But, interestingly, DSMP is the same: time in the story passes at more or less the same rate as time passes IRL, with the exception of periods spent in limbo. This raises some interesting questions about who determines linearity in a prosumptive (co-created by writers and audiences) piece of media. If you're looking at DSMP from the perspective of the CCs, it's a linear narrative in the ways I've just described. But if you look at it from the perspective of the audience (who are given the option to switch between streams, watch live, watch VODs afterwards, watch VODs out-of-order, or refuse to watch some streams/VODs altogether), then it can be - and often is - a very non linear story. In a straightforward narrative where the creators create and the consumers consume, this isn't even a question. But in the case of something like DSMP, which is a collaboration by creators and audiences, those lines of authority blur and we're left wondering whose timeline we're on.

So let's say, for the sake of this argument, that DSMP is a rhizomatic story. It doesn't check off all the boxes, but I would still say it qualifies for reasons I hope I've outlined above in at least a semi-comprehensible way. Well, there's this framework that's been developed for understanding these types of non-linear, decentralized stories: the violence hub.

The violence hub was proposed as a way of furthering our understanding of these participatory “multithreaded” stories that offer many voices at once without giving any particular one of those voices the final word.

Personally, I think DSMP is sort of the perfect example of a violence hub story, obviously because of the way it's constructed (talked about this a lot already here so I won't rehash it rn) but also because, quite frankly, it is a violent story. DSMP is bleak as fuck. Warfare, conflict, and abuse are core motifs. Like, even in a fandom as divided as this one, it's not controversial to say that DSMP is a story that's fixated on suffering, and that fixation is one of its main selling points. Not all fans are interested in those parts of the story, of course, but I think it's safe to say a lot of fans find DSMP's treatment of suffering pretty compelling. This is why people are insane about Exile and Pandora and Pogtopia and, and, and. You get the picture.

The violence hub is also a useful way of looking at not just how the story is structured, but how it is consumed. When fans talk about a violent incident in the story, whether it's Exile or c!Dream's imprisonment or something else, oftentimes we talk about these events in relation to other characters' perspectives and POVs. What's c!Tubbo up to during c!Tommy's exile? Who does or doesn't try to visit Logstedshire, and at what points in the Exile timeline? What's c!Dream doing during the Exile period when he's not at Logstedshire? This interactivity with the incident (Exile) through various other POVs deepens viewers' understandings of that incident, what it means to the characters involved, what it means in the larger narrative, and most importantly - what it means to us, the viewers. The same thing could be said about any period that qualifies as a "violent incident" described in the article screenshotted above. Take Pandora, for instance: how many times have you heard someone say "You really need to watch c!Sapnap's prison visit to get a sense of what it was like," or "c!Techno's prison podcast is vital to understanding what happens in Pandora," or something else to that effect. We all have specific streams we see as crucial puzzle pieces, but we don't all agree on what those streams are. And, depending on which streams you see as vital, your idea of what went down during a particular violence hub incident may be very different from my perception of that event, and vice-versa. Be that as it may, consuming the story this way, rather than in the form of a traditional linear narrative, allows viewers to come to more nuanced understandings of not just the incident in question, but also why the incident happened, what other events led up to it, the later impacts it had on the story, how character relationships and dynamics may have shifted as a result of the incident, etc. The decentralized nature of this structure enables an understanding of the story that appropriately accounts for its complexity.

Now that all that's out of the way, I want to talk about the structure of the violence hub in relation to audience expectations. When the finale aired, I was pretty confused by a lot of folks' reactions, partly because of how I perceived the DSMP and how I see its structure interacting with its themes. To me, DSMP is a story largely about cyclical violence, so an ending where c!Tommy (a main character, driving force for the narrative, and sometimes the protagonist depending on who you ask) chooses to put an end to that cycle made sense to me. I never saw the finale as being about an abuse victim forgiving his abuser, I saw it as being about an abuse victim purposefully stepping back, seeing the cycle of violence for what it is, and choosing to opt out. This is a fairly unpopular interpretation of the finale, but it's one that I stand by because it's firmly grounded in the text: the dialogue, the scenecraft, the structure. Up until the finale, c!Tommy perceives the DSMP as a linear, centralized story - his own! He acts accordingly, rarely stopping to consider consequences or other characters' perspectives. When he's sent to limbo in the finale, c!Tommy is suddenly able to see into c!Dream's past memories from c!Dream's perspective. In this moment, c!Tommy's experience of the narrative ceases to be linear and centralized; in this moment, he is experiencing the story in the same way that we, the audience have been experiencing the story. c!Tommy, placed in the audience's shoes, is presented with what is essentially a "branch" to the violence hub that is Exile, that is Pandora, that is the aftermath of both of those arcs. Upon seeing that "branch" (the memory), c!Tommy is given context for some of the events that have happened on the server. This newfound context allows him to understand his own story as a part of the stories of the people around him. This newfound context enables him to understand the story in a way that accounts for its complexities. He doesn't forgive c!Dream, but he is able to recognize the cycle of violence and choose not to participate anymore.

So, back to the thing I said about structure and audience expectations. As I mentioned, a lot of fans hated the finale for a lot of reasons. It wasn't to everyone's taste, and that's fine. But I would like to posit that one reason people didn't like the finale was because the rhizomatic structure of the story (which c!Tommy becomes aware of) subverted their own expectations about storytelling in general and this story in particular. I'd argue that a lot of people hated the finale because they were still clinging to the possibility of a non-rhizomatic narrative: one that has a traditional beginning/middle/end, one that has clear heroes and villains, one in which unambiguous good vanquishes unambiguous evil. Which isn't a bad thing to want, it's just...not what DSMP is, or ever was.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bibliography

- Bruns, A. (2016) "Prosumption, Produsage," in Jensen, K. B.; Craig, R. (eds) The International Encyclopedia of Communication Theory and Philosophy. JohnWiley & Sons, Inc. - Burrell, I. 2013. Dan & Phil: The YouTube stars tasked with bringing new young listeners to Radio 1. Online. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/media/tv-radio/dan-phil-the-youtube-stars-tasked-with-bringing-new-young-listeners-to-radio-1-8639836.html?r=17008 - Cynicalromanticaf. July 14th 2019. [online]. Available at: https://cynicalromanticaf.tumblr.com/post/186274909140/ill-ding-myself-if-you-dont-ding-me-and. [Accessed 11th April 2022]. - Djhquiff. March 7th 2019. [online]. Available at: https://djhquiff.tumblr.com/post/183299044737/i-dont-understand-how-a-six-foot-man-can-be-so. [Accessed 11th April 2022]. - djhquiff. October 19th, 2021. [online] Available at: https://grrten.tumblr.com/post/665451822115438592/happy-12-years [Accessed 11th Apr. 2022]. - Goodman, Cynthia. “The Digital Revolution: Art in the Computer Age.” Art Journal, vol. 49, no. 3, 1990, pp. 248–52, https://doi.org/10.2307/777115. - Grrten, October 19th 2021. [online]. Available at: https://grrten.tumblr.com/post/665451822115438592/happy-12-years. [Accessed 11th April 2022]. - Henry Jenkins. Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. Taylor and Francis, 2012. Web. - Howell, D. 2022. Daniel Howell. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/user/danisnotonfire. Online. - Howell, D. December 8th 2015. [online]. Available at: https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=the+urge+dan+howell&docid=608022899603500023&mid=C231A5E9BFC97EF94987C231A5E9BFC97EF94987&view=detail&FORM=VIRE. [Accessed 11th April 2022]. - Jenkins, H. (2006) Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York & London: New York University Press. Chapter 1 ‘Worship at the Alter of Convergence’. - Lamerichs, Nicolle. “Shared Narratives: Intermediality in Fandom.” Productive Fandom: Intermediality and Affective Reception in Fan Cultures, Amsterdam University Press, 2018, pp. 11–34, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv65svxz.4. - Lester, P. 2022. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/c/AmazingPhil. Online. - Lonelylestowell, March 19th 2018. [online]. Available at: https://lonelylestowell.tumblr.com/post/172031966144/dan-and-phils-life-in-a-nutshell-pt-2phil-hey/ [Accessed 11th April 2022]. - Polkadotphan. December 19th 2016. [online]. Available at: https://polkadotphan.tumblr.com/post/154665068191. [Accessed 11th April 2022]. - Polkadotphan. February 19th, 2017. [online]. Available at: https://polkadotphan.tumblr.com/post/157428259251/phans-bi-girl-phan-is-literally-on-fire. [Accessed 11th April 2022]. - Polkadotphan. January 17th 2017. [online]. Available at: https://polkadotphan.tumblr.com/post/156021999716/starscream-this-image-made-me-break-into-a-cold. [Accessed 11th April 2022]. - Ritzer, George, Paul Dean, and Nathan Jurgenson. “The Coming of Age of the Prosumer.” The American behavioral scientist (Beverly Hills) 56.4 (2012): 379–398. Web. - Succubusphan, December 5th 2021. [online]. Available at: https://succubusphan.tumblr.com/post/669749219677077504/the-box-under-the-bed. [Accessed 11th April 2022]. - Til-death-do-we-art. 7th June 2021. [online]. Available at: https://til-death-do-we-art.tumblr.com/post/653393402717667328/so-happy-for-danielhowell-and-amazingphil-and. [Accessed 11th April 2022].

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Johnlock fan fiction on Achieve Of Our Own (AO3) and the potential threats

Fan fiction is a remarkable form of fandom culture. It is the phenomenon that fans are started to become the prosumer, both the producer and consumer (Ritzer, 2014), and present their enthusiasm to the story and the character. It could be consider as prosumption phenomenon itself. Fan fiction is the text that reader can consume and respond to, and could inspire more fan fiction based on it (Banerjee, 2015). It is the catalyst of the creation of other transformative fan works, such as fan arts and fan videos.

As the digital involution creates more probabilities and opportunities, several online fan fiction media thrives. Online fan fiction can be shared and posted on different media platforms. For example, website (eg. AO3, Tumblr), social platforms (a Chinese social App ‘Weblog’, Instagram) and reading Apps (a Chinese App ‘Jing Jiang’).

Achieve Of Our Own (AO3), is one of the biggest fan fiction website. There are incredibly over 136 thousand fan fictions tagged Sherlock Holmes & related fandoms (BBC version) on AO3, while ‘Johnlock’ fictions, the stories about the romantic relationship between John Watson and Sherlock Holmes, ranked first by 20 thousands works (Sherlock Holmes & John Watson - Works | Archive of Our Own, 2014)! However, the characteristic of online fan fiction and sexual orientation embedded in could cause several concerns.

- False expectation

One of the concerns is this might cause criticism due to a false expectation of the LGBTQIA+ viewers toward the original television series. Fan fiction could be one of the most significant ways of bringing diverse representation in a mass media culture, when in the most text in 21st century, sexual minorities, racial and gender are given insufficient exposure. As Johnlock fan fiction depicts the two character as two gay man, considerable part of LGBTQIA+ viewers would be attracted by the romantic text (or subtext). They would consider this queer couple as a representation (Frenk, 2018) of them and expect to see this relationship to be presented on the television series. Considerable LGBTQIA+ viewers predict this will be developed officially in season four (the season after John lost his wife), however, this prediction didn’t come true. This result these audience displayed negative emotions, ranging from confusion to intense disappointment. Steven, the show co-creator also claimed that ‘People want to fantasize about it. It’s fine. But it’s not in the show,’(quoted by Roxy Simons, Mail Online, 2019).

Extreme actions towards the actors would be caused due to the effect of Johnlock fan fiction. Martin Freeman, the actor of ‘John Watson’ in the television serials ‘Sherlock Holmes’, claimed that he was struggled by serval death threats he revived on Tweeter due to ‘John Watson’ married a woman (Meadows, 2013). Meanwhile, the actress of ‘Marry Watson’, the wife of ‘John Watson’, also received vicious comments and messages. Freeman criticized those Johnlock fans are not the fans of the show, but are the ‘fans of a show going on their heads’. He added that he hope the audience can split the show with fan fiction, and don’t unleashed their anger towards any of the actors (Meadows, 2013).

- Sexualized text

Minor texts are highly sexualized and free accessed. For an example, there are 21.9% Johnlock texts on AO3 (achieve of our own) website are tagged as ‘explicit: only suitable for adults’ (Miranda, 2017, pp.8), while 112 texts among them has tag ‘underage’,’rape’ and ‘violence’ simultaneously (Sherlock Holmes & John Watson - Works | Archive of Our Own, 2014). As a positive aspect, those tags allows the Johnlock fans to find the text they suitable to more easily, and are able to avoid content that could be potentially harmful. The rating could also gives an indication of how much violence or sexual content will be present in the fiction, while “Archive Warnings” in AO3 allow the identification of particularly triggering content. For instance, major character death or rape, and therefore, readers can search for what they feel comfortable with, which shows consideration towards the community undergoes mental health concerns. However, the website does not strict the access of the underaged users to explicate contents, this would cause the improper imitation of the underaged reader. Considerable teenage girls started become Johnlock fans by sexualized fan fiction and developed by started to write their own Johnlock texts.

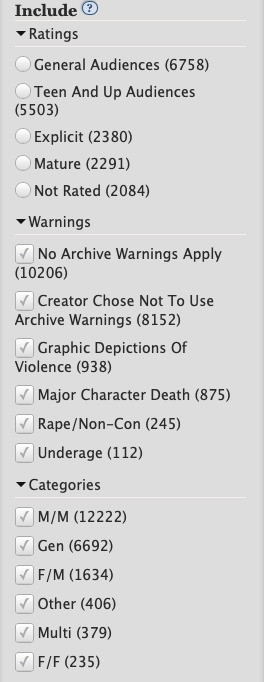

Filters on AO3 about ‘Sherlock Holmes & John Watson’ (Sherlock Holmes & John Watson - Works | Archive of Our Own, 2014)

Some Johnlock fan fiction would cause a fault choosing due to improper tags. The tag adding on AO3 is not compulsory, authors can add the tags they want or even don’t add any tags (Miranda, 2017, pp.14). This would be problematic that the readers cannot make an accurate choice as not every sexual or violence text is tagged with corresponding warnings. This would increase the threat that underaged population and other population who feel uncomfortable with certain actions would exposed to those texts with out intention.

- Lack of authority protection

There are lack of authority protection of the fan fiction writers. As fanfiction is published mainly in online communities, fanfiction authors usually use pseudonyms and obfuscatory usernames in order to to maintain anonymity (Banerjee, 2015). This would result to a lack of solidify identity that their readers could refer to. Combing with the free access of the texts, the authors’ rights are hard to preserve due to plagiarism and imposters.