#pseudoscience is not the same word as... eugenics

Text

this person doesn't even particularly seem to understand what IQ tests have to do with eugenics (though I totally would get what they are trying to say here if the other examples would make any sense at all), but someone claiming that the MBTI test and the HOGWARTS HOUSE TEST were designed to group people into hierarchies so we can kill or eradicate certain groups has got to be the most insane thing ive read this morning

#myposts#like. words have meanings hello#pseudoscience is not the same word as... eugenics#like yes. none of these things have a real scientific foundational basis#but only one of them is used as shorthand for something it can barely define#(because spoiler: the iq test wasn't at all designed to BE a catch-all intelligence measurer)#and only one of these groups things into a hierarchy people can actually discriminate against#like is this person saying people refuse to have children with Slytherin because theyre scared their children would be slytherin??#or like. that some politician is advocating for not allowing ENFPs to have children anymore?#or would try to fund better programmes for INTPs only??#like hello do you know what eugenics are??

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I was gonna ask you some stuff about Quincey and the aftermath of the Civil War, but that wasn't really near the 1890s so idk if it's relevant.

Also similar to Mina maybe supporting eugenics I would imagine Seward probably engages in a lot of pseudosciences

But more interestingly, what do you think Dracula's politics would be? He's pretty removed from human society by being a vampire and his home in Transylvania is pretty remote, but he was still a nobleman there and he was moving to England, which he planned to conquer. I'm curious where he'd fall, when pretending to be and working with (?) humans in Romanian politics (if you feel like researching it) and English politics. Another cool layer to this is if you subscribe to the popular theory that he's really Vlad the Impaler. What would a warlord from the mid-1400s think of the politics 400 or so years later? That's barely even thinking about him being a vampire.

Also, what would Renfield's politics be like?

Quincey and the aftermath of the Civil War is a fascinating question that I will definitely leave for someone who knows more US history than I do.

Dracula, on the other hand... first of all, the relevant set of politics is Hungarian, not Romanian. Transylvania was part of Austria-Hungary in the 1890s. There's actually an interesting story here, in that vampire myth was originally associated primarily with Hungary. Then Bram Stoker set Dracula in Transylvania, which became part of Romania in 1920, and Romania ended up inheriting vampire myths in the process. Which has generally done the Romanian tourist industry no harm at all. (Though when I was in Bucharest last weekend, my lovely tour guide, Andrea, was clearly a bit annoyed by people asking about it).

Anyway, we have a decent sense of what Dracula's politics are, because he spells them out on May 8: he's proud to be part of a fighting, conquering race, he values "warlike days", he disdains peasants, and he generally holds that might makes right.

Given his pride in "beating the Turk on his own ground", I think we can assume that he didn't approve of Austria-Hungary's neutrality in the Russo-Turkish War in 1877-8.

In some ways he fits into contemporary society. He is a boyar, one of the highest rank of feudal nobility, who retained a great deal of power in 1890s Austria-Hungary. Where in the UK the growth of industry made the middle classes wealthier, in Austria-Hungary that wealth often went straight back to the nobility. Just six percent of the population had the right to vote in general elections, compared with 18% in the UK (meanwhile New Zealand had universal suffrage from 1893).

But Dracula is still a product of an earlier time. He wants to increase his power through conquest, not through modernising his estate or being appointed to the board of directors of a bank. And while Austria-Hungary did grow through conquest (occupying Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878, for instance), it wasn't at nearly the same scale as other contemporary empires - for example, Austria-Hungary didn't take part in the Scramble for Africa.

Honestly, it makes perfect sense that Dracula would want to come to Britain. If he wanted conquest, carried out with indifference to cruelty, he would have got on extremely well with Cecil Rhodes. To an extent this is what the story of Dracula is about: what if foreigners came to Britain and did to us what we do to them? The War of the Worlds, published at the same time, asks essentially the same question but with aliens.

(This is the bit where someone comes along and says yes, but don't forget that Bram Stoker was Irish. Which is true, but he was also a supporter of the British Empire.)

As for Renfield, most of what we learn about his politics comes from October 1. He's from high society and is a member of the Windham Club. He celebrates the roles Quincey, Van Helsing and Arthur play "by nationality, by heredity, or by the possession of natural gifts" - in other words, he seems to be open to people advancing themselves through meritocracy, but also through hereditary rights. To me, this reads as conservative, but not reactionary.

One thing that does strike me is that his point about Texas - celebrating its admittance to the Union - relates to history that was 50 years old at that point (Unless I'm misunderstanding the reference?). Renfield is 59 during the events of Dracula. Is the implication here that he's stuck in the past? We don't know how long he's been institutionalised, but since his memories of Arthur's father relate to youthful drinking games, it could be 30 years or more. He may be disconnected from contemporary politics - and given how much the world changed in the late 19th century, that could make for quite a shock if he'd ever had the chance to learn more.

As ever, I'm not a historian, and other people should feel free to offer corrections.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

-- Awful Archaeology Ep. 8: The Nebraska Man --

I've heard it argued that science and pseudoscience are one in the same because they share discursive similarities and jargons. That, the medium being the message, the form being the content, the brand being the product, anything selling itself as science is, ipso facto, science. I consider this framework dangerous bunk.

Science is not a discourse, it is a methodology - and a constantly self-correcting and -refining one, at that. The case of H. haroldcookii is a prime example of the scientific method working. An overhasty and -confident hypothesis was published and promulgated. Colleagues questioned it with all appropriate skepticism, demanding extraordinary evidence to support an extraordinary claim. Further investigation determined the original hypothesis to be faulty. This is exactly what is supposed to happen. Science is supposed to be critical, not supportive; deliberate, not exuberant. Finally, no one paper is ever the final word on a subject: responses, questions, experimentation, replication or the failure thereof always follow for years after an initial purported discovery.

Contrast that to pseudoscience, with its conspiracist mindset, absolute statements of world-changing, instant paradigm shifts, and appeals to emotion. Too often, those who regard science and pseudoscience as equivalent are quick to approve of new theories and models for ideological and political reasons before they have been suitably tested and interrogated. Some even take offense at that interrogation. That is not worthy of the academy whether in the sciences and humanities, yet the rejection of rigorous methodology has become a proud feature of many supposed "scholars", especially in the humanities. The danger is that such an approach to knowledge, even in the name of social justice, will only lead us down the path of such figures as pseudoscience as eugenics and phrenology, with the potential for similarly disastrous consequences.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ch. 01 Dune Analysis

“A beginning is the time for taking the most delicate care that balances are

correct” Princess Irulan tells us in the very first printed sentence of Dune, and she is correct. As an introduction to an introduction, this first excerpt of Irulan’s writings does a remarkable amount of footwork. It introduces us to the two most important worlds of the story (Arrakis and Caladan) and places them in a hierarchy. It tells us that this will be a coming of age story, Muad’Dib going from his birthplace to his ‘place’ in Arrakis. And, perhaps most importantly, it begins the work of elevating this story to one of mythological proportions.

It then moves on to introducing us to Castle Caladan and the Reverend Mother of the Bene Gesserit. It does this with broad strokes, giving us a feel for the character before she ever speaks. ‘The old woman was a witch shadow...” With simple yet evocative language we learn so much about who she is, and her relationship to the world around her. Then, this ‘Witch Shadow’ gives us our first characterization of Pual. ‘Sly little rascal... But royalty has need of slyness.’ Before Paul speaks, before he is seen before even his perspective is introduced, we are given a remark on him. Of course as our protagonist and this ultimately being a coming of age story for a messiah there’s a lot of characterization that needs doing, but it’s interesting that again our dear Frank Herbert does a remarkable job of elevating Paul, even as a child.

More world building occurs, words like Bene Gesserit, and Gom Jabbar are thrown around, but to many of these things are as strange to Paul as they are to us. What is a Gom Jabbar? What is a Kwizatz Haderach? Neither Paul us readers have any idea, and yet Paul tastes them on his tongue, repeats them, he understands that they are important, and will center the story going forward.

The story continues with more worldbuilding and exposition, Paul, through his memory of Thufir Hawat, relaying to us complex power structures such as the rivalry between House Atreides and House Harkonnen, as well as bits of the CHOAM Company and some of the significance of Dune. Finally we are introduced to Paul’s precognitive abilities, not through some vision of Jihad or doom, but through a vision of the sacred. Figures moving in a sandy cavern, and the drip of the water of life, although we don’t know it yet. Then Paul awakes.

As the novel moves forward it introduces us to some techniques of the Bene Gesserit, their control over their bodies and their powers of observation. There’s so much ground to cover, and so much we are to know if we are to swim in the water of this story, and so Herbert methodically introduces us to everything we need know. There isn’t a wasted word here, and though the novel is certainly a thick one, as far as stories go it is tight and compact. That’s an easy thing to understand in the broad sense, but here we can see its excellent execution from the first sentence all the way down to Paul’s actual first meeting with the Reverend Mother.

The meeting between Gaius Helen Mohiam and Paul Atreides plays out much like a duel. There’s the opening bows, the careful studies of one another whilst they posture for position and power, and there’s a mutual respect.

The story moves on, Jessica leaves the room, and Mohiam introduces Paul to the Gom Jabbar. (As an aside, my reading comprehension was a little rough when I was younger, and I always saw the box as the Gom Jabbar and not the poisoned needle. In later readings I was confused that I had misremembered such an important event, and struggled with it. Now I know. Reading and understanding Dune is a process that for many takes multiple reads. This in part makes the novel less accessible but at the same time it adds a richness to the experience of reading the novel.) Paul passes the test to prove he’s human, and resists the urge to pull his hand from the box in spite of the pain. There’s some discussion of various wide ranging topics that the book covers, and its first delve into the pseudoscience of eugenics that is so important to the book. I’ll have more on that later, but suffice it to say for now:in the World of Dune, eugenics works. In ours, it is ineffective.

Finally Paul asks Mohiam my oft overlooked question, “Kwizatz Haderach, what’s that? A human Gom Jabbar?” Here is the first seed for the later books that is often almost but never truly explored in this novel. If you believe in the efficacy of the Golden Path then you believe that Paul was a human Gom Jabbar, and his jihad the crucible through which humanity is tested. It’s a bold move on Herbert’s part, stating one of his theses and never touching on it again except through the material of the book. I don’t know if I agree that it was the best move, but it’s interesting that I’m analyzing it even now, over half a century after Herbert originally published the novel.

The chapter ends with saying that other eugenically potential Kwizatz Haderachs tried the test and died failing it. An ominous note to be sure, but another step towards the mythologization of Paul that this book performs. All other who came before him died, but only he the messiah was able to live!

So that ends my summary of the first chapter. I’ll certainly be doing less in depth summaries of events as I move through the book, and will likely analyze multiple chapters at a time. But before I go I want to reiterate a few points, and make a few new points.

Frank Herbert’s world is remarkably well realized for a creation of its time. I think this plays a serious part in the remarkable success of the series (which, admittedly, was not overnight). Herbert’s worldbuilding choices weren’t just bold (although they certainly were) and they didn’t just elevate the themes and morals of the story, they did both! Sure Shelley’s FRANKENSTEIN had discussed high minded ideas, and sure noir writers were mastering compelling plots that flung you through well plotted stories, but I don’t believe there had been a work that came before Dune the properly wed theme and plot. Event and Idea. They play back into one another, compounding one another, forming a perfect soliton of impact upon our collective psyche. And here in the first chapter we can see the microcosm of that writing style. The suspense of the danger of the Gom Jabbar, the terrible purpose of the Kwizatz Haderach, the corrupt and unstable world that gave birth to both. It’s quite simply, a compelling story with compelling ideas.

The other interesting phenomena is that Herbert certainly wasn’t the last to do such things, although those who write such stories well inevitably see those stories succeed (Bladerunner and ASoIaF being other exemplary examples of wedding excellent plot to excellent theme) but his was the one who did it first, so his is the classic. Like the mountain dropped in the lake whose ravage all the world around it, none can survive the coming of Dune unchanged.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Futurology: how a group of visionaries looked beyond the possible a century ago and predicted today's world

by Max Saunders

We need more blue-sky thinking. Yolanda Sun/Unsplash

From shamanic ritual to horoscopes, humans have always tried to predict the future. Today, trusting predictions and prophecies has become part of daily life. From the weather forecast to the time the sat-nav says we will reach our destination, our lives are built around futuristic fictions.

Of course, while we may sometimes feel betrayed by our local meteorologist, trusting their foresight is a lot more rational than putting the same stock in a TV psychic. This shift toward more evidence-based guesswork came about in the 20th century: futurologists began to see what prediction looked like when based on a scientific understanding of the world, rather than the traditional bases of prophecy (religion, magic, or dream). Genetic modification, space stations, wind power, artificial wombs, video phones, wireless internet, and cyborgs were all foreseen by “futurologists” from the 1920s and 1930s. Such visions seemed like science fiction when first published.

They all appeared in the brilliant and innovative “To-Day and To-Morrow” books from the 1920s, which signal the beginning of our modern conception of futurology, in which prophecy gives way to scientific forecasting. This series of over 100 books provided humanity – and science fiction – with key insights and inspiration. I’ve been immersed in them for the last few years while writing the first book about these fascinating works – and have found that these pioneering futurologists have a lot to teach us.

In their early responses to the technologies emerging then – aircraft, radio, recording, robotics, television – the writers grasped how those innovations were changing our sense of who we are. And they often gave startlingly canny previews of what was coming next, as in the case of Archibald Low, who in his 1924 book Wireless Possibilities, predicted the mobile phone: “In a few years time we shall be able to chat to our friends in an aeroplane and in the streets with the help of a pocket wireless set.”

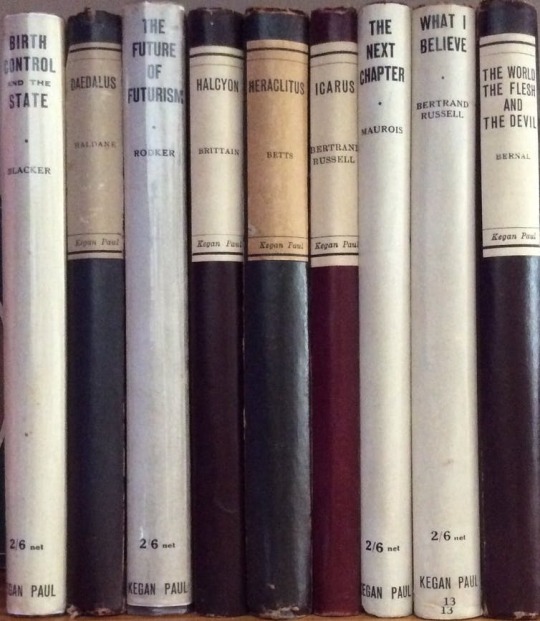

Some of the books in the series. Max Saunders, Author provided

My immersion in these historic visions of the future has also shown me that looking at this collection of sparkling projections can teach us a lot about current prediction attempts, which today are dominated by methodologies claiming scientific rigour, such as “horizon scanning”, “scenario planning” and “anticipatory governance”. Unlike the corporate, bland way in which most of this professional future gazing takes place within government, think-tanks and corporations, the scientists, writers, and experts who wrote these books produced very individual visions.

They were committed to thinking about the future on a scientific basis. But they were also free to imagine futures that would exist for other reasons than corporate or governmental advantage. The resulting books are sometimes fanciful, but their fancy occasionally gets them further than today’s more cautious and methodical projections.

Forecasting future discoveries

Take J B S Haldane, the brilliant mathematical geneticist, whose book Daedalus; or: Science and the Future inspired the whole series in 1923. It ranges widely across the sciences, trying to imagine what remained to be done in each.

Haldane thought the main work in physics had been done with the Theory of Relativity and the development of quantum mechanics. The main tasks left seemed to him to be the delivery of better engineering: faster travel and better communications.

Chemistry, too, he saw as likely to be concerned more with practical applications, such as inventing new flavours or developing synthetic food, rather than making theoretical advances. He also realised that alternatives would be needed to fossil fuels and predicted the use of wind power. Most of his predictions have been fulfilled (though we’re still waiting eagerly for those new flavours, which have to be better than salted caramel).

The first cultured hamburger, 2013. World Economic Forum, CC BY

It’s chastening, though, how much even such a clear-sighted and ingenious scientist missed, especially in the future of theoretical physics. He doubted nuclear power would be viable. He couldn’t know about future discoveries of new particles leading to radical changes to the model of the atom. Nor, in astronomy, could he see the theoretical prediction of black holes, the theory of the big bang or the discovery of gravitational waves.

But, at the dawn of modern genetics, he saw that biology held some of the most exciting possibilities for future science. He foresaw genetic modification, arguing that: “We can already alter animal species to an enormous extent, and it seems only a question of time before we shall be able to apply the same principles to our own.” If this sounds like Haldane supported eugenics, it’s important to note that he was vocally opposed to forced sterilisation, and didn’t subscribe to the overtly racist and ableist eugenics movement that was en vogue in America and Germany at the time.

But the development that caught the eye of so many readers was what Haldane called “ectogenesis” – his term for growing embryos outside the body, in artificial wombs. Many of the other contributors took up the idea, as did other thinkers – the most notable being Haldane’s close friend Aldous Huxley, who was to use it in Brave New World, with its human “hatcheries” cloning the citizens and workers of the future. It was also Haldane who coined the word “clone”.

Ectogenesis still seems like science fiction. But the reality is getting closer. It was announced in May 2016 that human embryos had been successfully grown in an “artificial womb” for 13 days – just one day short of the legal limit, which prompting an inevitable ethical row. And in April 2017 an artificial womb designed to nurture premature human babies was successfully trialled on sheep. So even that prediction of Haldane’s may well be realised soon, perhaps within a century after it was made. Although artificial wombs will probably be used, at first, as a prosthesis to cope with medical emergencies, before they become routine options, on a par with caesareans or surrogacy.

youtube

Science, then, was not just science for these writers. It had social and political consequences, as does prediction. Many of the contributors of this series were social progressives, in sexual as well as political matters. Haldane looked forward to the doctor taking over from the priest and science separating sexual pleasure from reproduction. In ectogenesis, he foresaw that women could be relieved of the pain and inconvenience of bearing children. As such, the idea could be seen as a feminist thought experiment – though some feminists might now see it as a male attempt to control women’s bodies.

What this reveals is how shrewd these writers were about the controversies and social proclivities of the age. At a time when too many thinkers were seduced by the pseudoscience of eugenics, Haldane was scathing about it. He had better ideas about how humanity might want to transform itself.

What this reveals is how shrewd these writers were about the controversies and social proclivities of the age. At a time when too many thinkers were seduced by the pseudoscience of eugenics, Haldane was scathing about it. He had better ideas about how humanity might want to transform itself. While most of the scholars musing on eugenics merely supported white supremacy, Haldane’s motives suggest he’d be delighted at the advent of technologies like CRISPR – a method by which humankind could better itself in ways that mattered, like curing congenital disease.

Alternate futures

Some of To-Day and To-Morrow’s predictions of technological developments are impressively accurate, such as video phones, space travel to the moon, robotics and air attacks on capital cities. But others are charmingly inaccurate.

Oliver Stewart’s 1927 volume, Aeolus or: The Future of the Flying Machine, argued that British craftsmanship would triumph over American mass production. He was excited by autogiros – small aircraft with a propeller for thrust and a freewheeling rotor on top, for which there was a craze at the time. He thought travellers would use those for short-haul flights, transferring for long-haul to flying boats – passenger planes with boat-like bodies that could take off from, and land on, the sea. Flying boats certainly had their vogue for glamorous voyages across the ocean, but disappeared as airliners became bigger and longer range and as more airports were built.

The Dornier Do X was the largest, heaviest, and most powerful flying boat in the world when it was produced by the Dornier company in Germany in 1929. Wikipedia, CC BY

The To-Day and To-Morrow series, like all futurology, is full of such parallel universes. Paths history could well have taken, but didn’t. In the rousing 1925 feminist volume Hypatia or: Woman and knowledge, Bertrand Russell’s wife Dora proposed that women should be paid for household work. Unfortunately, this has not come to pass either.

The film critic Ernest Betts, meanwhile, writes in 1928’s Heraclitus; or The Future of films that “the film of a hundred years hence, if it is true to itself, will still be silent, but it will be saying more than ever”. His timing was terrible, as the first “talkie”, The Jazz Singer, had just come out. But Betts’s vision of film’s distinctiveness and integrity – the expressive possibilities open to it when it brackets off sound – and of its potential as a universal human language, cutting across different linguistic cultures, remains admirable.

The difficulty with future thinking is to guess which of the forking paths leads to our real future. In most of the books, moments of surprisingly accurate prediction are tangled up with false prophecies. This isn’t to say that the accuracy is just a matter of chance. Take another of the most dazzling examples, The World, the Flesh and the Devil by the scientist J D Bernal, one of the great pioneers of molecular biology. This has influenced science fiction writers, including Arthur C Clarke, who called it “the most brilliant attempt at scientific prediction ever made”.

Bernal sees science as enabling us to transcend limits. He doesn’t think we should settle for the status quo if we can imagine something better. He imagines humans needing to explore other worlds and to get them there he imagines the construction of huge life-supporting space stations called bio-spheres, now named after him as “Bernal spheres”. Imagine the international space station, scaled up to small planet or asteroid size.

youtube

Brain in a vat

When Bernal turns to the flesh, things get rather stranger. A lot of the To-Day and To-Morrow writers were interested in how we use technologies as prosthesis, to extend our faculties and abilities through machines. But Bernal takes it much further. First, he thinks about mortality – or more specifically – about the limit of our lifespan. He wonders what science might be able to do to extend it.

In most deaths the person dies because the body fails. So what if the brain could be transferred to a machine host, which could keep it, and therefore the thinking person, alive much longer?

Bernal’s thought experiment develops the first elaboration of what philosophers now call the “brain in a vat” hypothesis. Except they’re usually concerned with questions of perception and illusion (if my brain in a vat was sent electrical signals identical to the ones sent by my legs, would I think I was walking? Would I be able to tell the difference?). But Bernal has more pragmatic ends in view. Not only would his Dalek-like machines be able to extend our brain life, they’d be able to extend our capabilities. They would give us stronger limbs and better senses.

youtube

Bernal wasn’t the first to postulate what we’d now call the cyborg. It had already appeared in pulp science fiction a couple of years earlier – talking, believe it or not, about ectogenesis.

But it’s where Bernal takes the idea next that is so interesting. Like Haldane’s, his book is one of the founding texts of transhumanism – the idea that humanity should improve its species. He envisions a small sense organ for detecting wireless frequencies, eyes for infra-red, ultra-violet and X-rays, ears for supersonics, detectors of high and low temperatures, of electrical potential and current.

With that wireless sense Bernal imagined how humanity could be in touch with others, regardless of distance. Even fellow humans across the galaxy in their biospheres could be within reach. And, like several of the series’ authors, he imagines such interconnection as augmenting human intelligence, of producing what science fiction writers have called a hive mind, or what Haldane calls a “super-brain”.

It’s not AI exactly because its components are natural: individual human brains. And in some ways, coming from Marxist intellectuals like Haldane and Bernal, what they’re imagining is a particular realisation of solidarity. Workers of the world uniting, mentally. Bernal even speculates that if your thoughts could be broadcast direct to other minds in this way, then they would continue to exist even after the individual brain that thought them had died. And so would offer a form of immortality guaranteed by science instead of religion.

Blind spots

But from a modern point of view what’s more interesting is how Bernal effectively imagined the world wide web, more than 60 years before its invention by Tim Berners Lee. What neither Bernal, nor any of the To-Day and To-Morrow contributors could imagine, though, was the computers needed to run it – even though they were only about 15 years away when he was writing. And it is these computers that have so ramped up and transformed these early attempts at futurology into the industry it is today.

How can we account for this computer-shaped hole at the centre of so many of these prophecies? It was partly that mechanical or “analogue” computers such as punched card machines and anti-aircraft gun “predictors” (which helped gunners aim at rapidly moving targets) had become so good at calculation and information retrieval. So good, in fact, that to the inventor and To-day and To-morrow author H Stafford Hatfield what was needed next was what he called “the mechanical brain”.

So these thinkers could see that some form of artificial intelligence was required. But even though electronics were developing rapidly, in radios and even televisions, it didn’t yet seem obvious – it didn’t even seem to occur to people – that if you wanted to make something that functioned more like a brain it would need to be electronic, rather than mechanical or chemical. But that was exactly the moment when neurological experiments by Edgar Adrian and others in Cambridge were beginning to show that what made the human brain tick was actually the electrical impulses that powered the nervous system.

Just 12 years later, in 1940 – before the development of the first digital computer, Colossus at Bletchley Park – it was possible for Haldane (again) to see that what he called “Machines that Think” were beginning to appear, combining electrical and mechanical technologies. In some ways our situation is comparable, as we sit poised just before the next great digital disruption: AI.

A Colossus codebreaking computer, 1943. Wikimedia Commons

Bernal’s book is a fascinating example of just how far extended future thinking can go. Further than actual science, or science fiction, or philosophy or anything else. But it also shows where it reaches its limits. If we can understand why the To-Day and To-Morrow authors were able to predict biospheres, mobile phones and special effects, but not the computer, the crisis in obesity, or the resurgence of religious fundamentalisms, then maybe we can learn about the blind spots in our own forward vision and horizon scanning.

Beyond the simple wows and comedic effects of these hits and misses, we need more than ever to learn from these past examples about the potential and dangers of future thinking. We would do well to look closely at what might helps us to be better futurologists, as well as at what might be blocking our vision.

Yesterday and today

The pairing of scientific knowledge and imagination in these books created something unique – a series of hypotheticals somewhat lodged between futurology and science fiction. It is this sense of hopeful imagination that I think urgently needs to be injected back into today’s predictions.

Because computers have transformed contemporary futurology in major ways: especially in terms of where and how it is carried out. As I have mentioned, computer modelling of the future mainly happens in businesses or organisations. Banks and other financial companies want to anticipate shifts in the markets. Retailers need to be aware of trends. Governments need to understand demographic shifts and military threats. Universities want to drill down into the data of these or other fields to try to understand and theorise what is happening.

To do this kind of complex forecasting well, you have to be a fairly large corporation or organisation with adequate resources. The bigger the data, the hungrier the exercise becomes for computing power. You need access to expensive equipment, specialist programmers and technicians. Information that citizens freely offer to companies such as Facebook or Amazon is sold on to other companies for their market research – as many were shocked to discover in the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

The main techniques which today’s governments and industries use to try to prepare for or predict the future – horizon scanning and scenario planning – are all well and good. They may help us nip wars and financial crashes in the bud – though rather obviously, they don’t always get it right either. But as a model for thinking about the future more generally, or for thinking about other aspects of the future, such methods are profoundly reductive.

They’re all about maintaining the status quo, about risk aversion. Any interesting ideas or innovative speculations that are about anything other than risk avoidance are likely to get pushed aside. The group nature of think-tanks and foresight teams also has a levelling down effect. Future thinking by committee has a tendency to come out in bureaucratese: bland, impersonal, insipid. The opposite of science fiction.

Horizon scanning doesn’t tend to produce any particularly exciting ideas. Zhao jiankang/Shutterstock.com

Which is perhaps why science fiction needs to put its imagination in hyperdrive: to boldly go where the civil servants and corporate aparatchiks are too timid to venture. To imagine something different. Some science fiction is profoundly challenging in the sheer otherness of its imagined worlds.

That was the effect of 2001 or Solaris, with their imagining of other forms of intelligence, as humans adapt to life in space. Kim Stanley Robinson takes both ideas further in his novel 2312, imagining humans with implanted quantum computers and different colony cultures as people find ways of living on other planets, building mobile cities to keep out of the sun’s heat on Mercury, or terraforming planets, even hollowing out asteroids to create new ecologies as art works.

When we compare To-Day and To-Morrow with the kinds of futurology on offer nowadays, what’s most striking is how much more optimistic most of the writers were. Even those like Haldane and Vera Brittain (she wrote a superb volume about women’s rights in 1929) who had witnessed the horrors of modern technological war, saw technology as being the solution rather than the problem.

Imagined futures nowadays are more likely to be shadowed by risk, by anxieties about catastrophes, whether natural (asteroid collision, mega-tsunami) or man-made (climate change and pollution). The damage industrial capitalism has inflicted on the planet has made technology seem like the enemy now. Certainly, until anyone has any better ideas, and tests them, reducing carbon emissions, energy waste, pollution, and industrial growth seem like our best bet.

Imagining positive change

The only thing that looks likely to convince us to change our ways is the dawning conviction that we have left it too late. That even if we cut emissions to zero now, global warming has almost certainly passed the tipping point and will continue to rise to catastrophic levels regardless of what we do to try to stop it.

That realisation is beginning to generate new ideas about technological solutions – ways of extracting carbon from the atmosphere or of artificially reducing sunlight over the polar ice caps. Such proposals are controversial, attacked as encouragements to carry on with Anthropocene vandalism and expect someone else to clear up our mess.

But they might also show that we are at an impasse in future thinking, and are in danger of losing the ability to imagine positive change. That too is where comparison with earlier attempts to predict the future might be able to help us. They could show us how different societies in different periods have different orientations towards the past or the future.

Where the modernism of the 1920s and 30s was very much oriented towards the future, we are more obsessed with the past, with nostalgia. Ironically, the very digital technology that came with such a futuristic promise is increasingly used in the service of heritage and the archive. Cinematic special effects are more likely to deliver feudal warriors and dragons, rather than rockets and robots.

But if today’s futurologists could get back in touch with the imaginative energies of their predecessors, perhaps they would be better equipped to devise a future we could live with.

About The Author:

Max Saunders is Professor of English at King's College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

13 notes

·

View notes

Link

By Kevin Reed

17 August 2019

Recently published news reports and legal studies have revealed that the US government has been violating basic democratic rights by using facial recognition to monitor and track the public. These reports have also shown that facial recognition is used widely as a preferred form of police biometrics, i.e., the science of identification and tracking through facial signatures and other kinds of unique individual measurements such as finger, palm and voice prints and dental and DNA profiles.

Every level of law enforcement—from city and state police departments to federal border patrol and military-intelligence—has been participating in the mass collection and analysis of facial images. This includes photos taken for government-issued ID cards and driver’s licenses and others captured from hidden surveillance cameras in public places such as border crossings, highways, parks, sporting events, sidewalks and airports as well as those scraped from social media accounts.

Georgetown Law published a study on May 19 called “America Under Watch” which documented the widespread use of facial recognition by the city governments and police departments of Detroit and Chicago. As part of its conclusion, the Georgetown report said, “real-time video surveillance threatens to create a world where, once you set foot outside, the government can track your every move. For the 3.3 million Americans residing in Detroit and Chicago, this may already be a reality.”

However, just as public outrage over these revelations had begun to emerge and several cities have been forced to ban the use of facial recognition—including San Francisco and Oakland, California as well as Somerville, Massachusetts—it became clear that the latest media exposures have a twofold political purpose.

On the one hand, the most conscious sections of the ruling establishment are concerned about the explosive reaction of millions of people to unfettered 24/7 state monitoring of their activities and whereabouts. Therefore, significant political pressure is being applied to force Congress to adopt as soon as possible a federal regulatory framework for the expanding biometric surveillance apparatus.

On the other hand, Democratic Party representatives and their supporters are using identity politics to conceal the serious implications of secret facial profiling and the trend toward a police state that it represents. By focusing exclusively on studies indicating race and gender bias in facial recognition tools, the Democrats are seeking to divert public anger away from a mass struggle by the working class in defense of democratic rights and into support for laws that will legalize the surveillance.

Among the most often referenced of the race and gender bias studies has been the MIT Media Lab Gender Shades project by Joy Buolamwini—a self-proclaimed “poet of code” and campaigner against “algorithmic bias”—who published her first results in 2017. The initial Gender Shades analysis of facial analysis technology from IBM, Microsoft and Face++ showed that “male subjects were more accurately classified than female subjects,” “lighter subjects were more accurately classified than darker individuals” and “all classifiers performed worst on darker female subjects.”

A follow-up study in 2018 by Buolamwini also showed that facial recognition tools from Amazon and Kairos exhibited the same trends performing “better on male faces than female faces” and “better on lighter faces than darker faces” and “have the current worst performance for the darker female sub-group.”

A similar—although far less scientific—test was performed by the ACLU on Amazon’s Rekognition facial analysis software in July 2018. A database of 25,000 mugshots was compared against public photos of every member of the US House and Senate. Amazon’s tool returned 28 false matches identifying them “as other people who have been arrested for a crime.”

The ACLU report then said, “The false matches were disproportionately of people of color … 40 percent of Rekognition’s false matches in our test were of people of color, even though they make up only 20 percent of Congress.” Since Amazon’s Rekognition is currently being used as the facial analysis tool of choice by city, county and state police departments across the country, false identification rates of minorities are of legitimate concern among workers and young people.

However, the political objective behind the Gender Shades and ACLU studies is not to prove that facial recognition should be stopped immediately, but to insist that the technology can be improved upon. The ACLU says that what is needed is “transparency and accountability in artificial intelligence” and a moratorium on law enforcement use of facial recognition until “all necessary steps are taken to prevent them from harming vulnerable communities.”

In other words, according to the ACLU, police surveillance with facial recognition of the working class is fine and can go forward with appropriate technical adjustments that reduce false identification of minorities and with the adoption of acceptable federal government guidelines for its use.

Essentially, the MIT and ACLU findings have been seized upon by the New York Times, the Democrats and organizations such as the Democratic Socialists of America as a means of burying fundamental democratic questions beneath race and gender politics. What they are advocating is, in essence, a racialist ideology and politics that serve to divide the working class and prevent a unified struggle against the growing threat of a police state in America.

For example, in entirely predictable fashion, the Times published a snide article on February 8, 2018 with the headline “Facial recognition is accurate, if you’re a white guy,” which featured Joy Buolamwini and her Algorithmic Justice League.

What becomes clear in the course of the Times interview with Buolamwini is that she is on a mission for “inclusion” of minorities and women into the corrupt corporate world of government-sponsored artificial intelligence surveillance technology. Through the efforts of the Gender Shades study and others, organizations like IBM and the Ford Foundation—who talk to the Times about how they are “deeply committed” to “unbiased” and “transparent” spying on the public—get to pose as “progressive” companies.

On July 10 of this year, the Times also published a comment by its graphics editor Sahil Chinoy headlined, “The Racist History Behind Facial Recognition,” that mechanically and ahistorically sought to draw a direct line of causality between the reactionary eugenics and racialist pseudoscience of the 19th and early 20th centuries—that claimed head shape and facial morphology characteristics were predictive of behavior and mental capacities—with modern biometrics.

The purpose of the Times reporting is to show that, through the anti-bias efforts of Buolamwini and others who call for “fairness and inclusion” in facial recognition, the corporate partners of the FBI and the surveillance state itself can be convinced of the value of “standards for accountability and transparency.”

However, as was clearly shown in the second Gender Shades study, the result of this campaign against race and gender bias has been the improvement of software algorithms by the developers. Although this aspect of Buolamwini’s study has been given little attention, the 2018 results showed, “Within 7 months, all targeted corporations were able to significantly reduce error gaps … revealing that if prioritized, the disparities in performance between intersectional subgroups can be addressed and minimized in a reasonable amount of time.”

This was also echoed in a statement sent to Buolamwini by IBM which, according to the Times, said that within a month of her second study results, the company “will roll out an improved service with a nearly 10-fold increase in accuracy on darker-skinned women.”

The race and gender bias campaign has also fueled efforts by Democratic Party politicians across the country to cover up their own role in the creation and maintenance of the surveillance state apparatus by posturing as opponents of the false identification flaws of the software.

The racialist character of identity politics was on full display during a hearing of the House Oversight and Reform Committee on May 22, for example, when Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (Democrat of New York)—a member of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA)—concluded her questioning of the panelists with a stage-managed exchange with Buolamwini who was a key witness. After being asked by Ocasio-Cortez what demographic facial recognition tools are “mostly effective on” and “who are the primary engineers and designers of these algorithms?” Buolamwini responded multiple times with “white men.”

Ultimately, the efforts of the Democrats, the DSA and identity politics advocates are aimed at diverting the anger of the working class against the mass surveillance into demands for congressional action that would make it legal to spy on the public with facial recognition tools as long as it is “fair and unbiased.”

The defense of democratic rights cannot be entrusted to these representatives of the affluent middle class who are employing methods of deception to conceal their own moneyed interests in getting on board with the private surveillance industry as well as the true meaning and historical implications of what is unfolding in society.

The growth of extreme economic inequality, the unending US wars in the Middle East and elsewhere and the evolution of the administration of President Donald Trump toward authoritarian rule—with the support of the Democratic Party—are all aspects of decaying democracy in advance of a massive confrontation between the working class and the ruling establishment in America and internationally.

It is in preparation for this conflict that the surveillance state is being erected and perfected. Workers, students and young people must unify across all national, racial, gender and language differences—independently of the government, the corporations and the middle-class pseudo-left—to make their own preparations for the major class battles now on the horizon.

#racism#identity politics#democratic socialists of america#democratic party#facial recognition technology#racialism#racial identity

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

sorry if you dont know much about mbti stuff but i know while in kinshift the way you act can change etc… but is it possible for the mbti type to change i know mbti types cant change in general but if you’re in kinshift can it?? i know kintypes share the same body but can the mbti change? im sorry if i worded this confusingly

Hi anon,

Unfortunately I actually have a bit of a problem with the whole concept of MBTI. And actually, your MBTI type can change. In fact, it's pretty much guaranteed to change - people have documented getting different MBTI personality types within five months of taking the test for the first time. It's not exactly an accurate judge of character.

The test itself is complete pseudoscience, created not by a psychologist but by a mystery novel author. A mystery novel author whose books reeked of racism and eugenics.

I would not worry too much about your MBTI personality type in relation to your kintypes. You are always going to be you.

0 notes

Text

How predicting the future shifted from fiction to fact—and what we lost along the way

New Post has been published on https://nexcraft.co/how-predicting-the-future-shifted-from-fiction-to-fact-and-what-we-lost-along-the-way/

How predicting the future shifted from fiction to fact—and what we lost along the way

We could use a little more whimsy in our forecasting. (Unsplash/)

The findings of this research were first covered by The Conversation as part of its Insights series.

From shamanic ritual to horoscopes, humans have always tried to predict the future. And while some of those practices may sound arcane, modern life still relies on prophecy. From the weather forecast to the time the GPS says we’ll reach our destination, our lives are built around futuristic fictions.

Of course, while we may sometimes feel betrayed by our local meteorologist, trusting their foresight is a lot more rational than putting the same stock in a TV psychic. This shift toward more evidence-based guesswork came about in the 20th century: futurologists began to see what prediction looked like when based on a scientific understanding of the world, rather than the traditional bases of prophecy (religion, magic, or dream). Genetic modification, space stations, wind power, artificial wombs, video phones, wireless internet, and cyborgs were all foreseen by “futurologists” from the 1920s and 1930s. Such visions seemed like science fiction when first published.

They all appeared in the brilliant and innovative “To-Day and To-Morrow” books from the 1920s, which signal the beginning of our modern conception of futurology, in which prophecy gives way to scientific forecasting. This series of more than 100 books provided humanity— and science fiction—with key insights and inspiration. I’ve been immersed in them for the last few years while writing the first book about these fascinating works, and have found that these pioneering futurologists have a lot to teach us.

In their early responses to the technologies emerging at the time—aircraft, radio, recording, robotics, television—the writers grasped how those innovations were changing our sense of who we are. And they often gave startlingly canny previews of what was coming next, as in the case of Archibald Low, who in his 1924 book “Wireless Possibilities” predicted the mobile phone: “In a few years time we shall be able to chat to our friends in an aeroplane and in the streets with the help of a pocket wireless set.”

Looking at this collection of sparkling projections can teach us a lot about current prediction attempts, which are dominated by methodologies claiming scientific rigour, such as “horizon scanning,” “scenario planning,” and “anticipatory governance.” Most of this professional future gazing takes place within government, think-tanks, and corporations, resulting in bland and narrowly targeted projections. But the scientists, writers, and experts who wrote these futurology books produced very individual visions.

They were committed to thinking about the future on a scientific basis, but they were also free to imagine worlds that would emerge for reasons other than corporate or governmental advantage. The resulting narratives are sometimes fanciful, but this whimsy occasionally gets them further than today’s more cautious and methodical projections.

Forecasting future discoveries

Take J B S Haldane, the brilliant mathematical geneticist, whose 1923 book “Daedalus; or: Science and the Future” inspired the rest of the series. It ranges widely across the sciences, trying to imagine what remained to be done in each.

Haldane thought physics had wrapped up most of its mysteries with the Theory of Relativity and the development of quantum mechanics. The main tasks left seemed to him to be the delivery of better engineering: faster travel and better communications.

Chemistry, too, he saw as likely to be concerned more with practical applications, such as inventing new flavors or developing synthetic food, rather than making theoretical advances. He also realized that alternatives to fossil fuels would be necessary, and forecast the use of wind power. Most of his predictions have been fulfilled.

It’s chastening, though, how much even such a clear-sighted and ingenious scientist missed, especially in the future of theoretical physics. He doubted nuclear power would be viable. He couldn’t know about future discoveries of new particles leading to radical changes to the model of the atom. Nor, in astronomy, could he see the theoretical prediction of black holes, the theory of the big bang, or the discovery of gravitational waves.

But, at the dawn of modern genetics, he saw that biology held some of the most exciting possibilities for future science. He foresaw genetic modification, arguing that: “We can already alter animal species to an enormous extent, and it seems only a question of time before we shall be able to apply the same principles to our own.” If this sounds like Haldane supported eugenics, it’s important to note that he was vocally opposed to forced sterilization, and didn’t subscribe to the overtly racist and ableist eugenics movement that was en vogue in America and Germany at the time.

To-Day and To-Morrow. (Max Saunders/)

The development that caught the eye of so many readers was what Haldane called “ectogenesis”—his term for growing embryos outside the body in artificial wombs. Many other futurologists and thinkers took up the idea, the most notable being Haldane’s close friend Aldous Huxley, who was to use it in “Brave New World,” with its human “hatcheries” cloning the citizens and workers of the future. It was also Haldane who coined the word “clone.”

Ectogenesis still seems like science fiction, but the reality is getting closer. It was announced in May 2016 that human embryos had been successfully grown in an “artificial womb” for 13 days—just one day short of the legal limit, which prompted an inevitable ethical row. And in April 2017 an artificial womb designed to nurture premature human babies was successfully trialled on sheep. So even that prediction of Haldane’s may well be realized soon, perhaps within a century after he dreamed it up. Artificial wombs will probably be used first as a prosthesis to cope with medical emergencies, but they could eventually become as routine as caesareans or surrogacy.

Science, then, was not just science for these writers. It had social and political consequences. Many of the contributors of this series were social progressives, in sexual as well as political matters. Haldane looked forward to the doctor taking over from the priest, with science finally separating sexual pleasure from reproduction. In ectogenesis, he foresaw that women could be relieved of the pain and inconvenience of bearing children. As such, the idea could be seen as a feminist thought experiment.

What this reveals is how shrewd these writers were about the controversies and social proclivities of the age. At a time when too many thinkers were seduced by the pseudoscience of eugenics, Haldane was scathing about it. He had better ideas about how humanity might want to transform itself. While most of the scholars musing on eugenics merely supported white supremacy, Haldane’s motives suggest he’d be delighted at the advent of technologies like CRISPR—a method by which humankind could better itself in ways that mattered, like curing congenital disease.

Alternate futures

Some of To-Day and To-Morrow’s predictions of technological developments are impressively accurate, such as video phones, space travel to the moon, robotics, and air attacks on capital cities. But others are charmingly misguided.

The Dornier Do X was the largest, heaviest, and most powerful flying boat in the world when it was produced by the Dornier company in Germany in 1929. (Wikipedia, CC BY/)

Oliver Stewart’s 1927 volume, “Aeolus or: The Future of the Flying Machine,” argued that British craftsmanship would triumph over American mass production. He was excited by autogiros—a small aircraft with a propeller for thrust and a freewheeling rotor on top—for which there was a craze at the time. He thought travelers would use those for short-haul flights, transferring for long-haul to flying boats: passenger planes with boat-like bodies that could take off from, and land on, the sea. Flying boats certainly had their vogue for glamorous voyages across the ocean, but disappeared as airliners became bigger and longer range and as more airports were built.

The To-Day and To-Morrow series, like all futurology, is full of such parallel universes. In the rousing 1925 feminist volume “Hypatia or: Woman and knowledge,” activist Dora Russell (wife of the philosopher Bertrand) proposed that women should be paid for household work. Unfortunately, this has not come to pass (though modern science is at least interested in calculating how traditionally feminine tasks cut into productivity and wellbeing).

The film critic Ernest Betts, meanwhile, writes in 1928’s “Heraclitus; or The Future of films” that “the film of a hundred years hence, if it is true to itself, will still be silent, but it will be saying more than ever.” His timing was terrible, as the first “talkie,” The Jazz Singer, had just come out. But Betts’s vision of film’s distinctiveness and integrity—the expressive possibilities open to it when it brackets off sound—and of its potential as a universal human language, cutting across different linguistic cultures, remains admirable.

It’s difficult to guess which of the forking paths before us leads to our real future. In most of the books, moments of surprisingly accurate prediction are tangled up with false prophecies. This isn’t to say that the accuracy is just a matter of chance. Take another of the most dazzling examples, “The World, the Flesh and the Devil” by the scientist J D Bernal, one of the great pioneers of molecular biology. This has influenced science fiction writers, including Arthur C Clarke, who called it “the most brilliant attempt at scientific prediction ever made.”

Bernal sees science as enabling us to transcend limits. He doesn’t think we should settle for the status quo if we can imagine something better. He imagines humans needing to explore other worlds, and to get them there he imagines the construction of huge, life-supporting space stations called bio-spheres, now named after him as “Bernal spheres.” Imagine the international space station, scaled up to small planet or asteroid size.

Brain in a vat

When Bernal turns to the flesh, things get rather stranger. A lot of the To-Day and To-Morrow writers were interested in how we use technologies as prostheses, to extend our faculties and abilities through machines. But Bernal takes it much further. First, he thinks about mortality, or more specifically about the limit of our lifespan. He wonders what science might be able to do to extend it.

In most deaths, the person dies because the body fails. So what if the brain could be transferred to a machine host, which could keep it—and therefore the thinking person—alive much longer?

Bernal’s thought experiment develops the first elaboration of what philosophers now call the “brain in a vat” hypothesis. Modern discussions of said brains in said vats are usually concerned with questions of perception and illusion (if my brain in a vat was sent electrical signals identical to the ones sent by my legs, would I think I was walking? Would I be able to tell the difference?). But Bernal has more pragmatic ends in view. Not only would his Dalek-like machines be able to extend human brain life, but they’d also be able to extend our capabilities. They would give us stronger limbs and better senses.

Bernal wasn’t the first to postulate what we’d now call the cyborg. It had already appeared in pulp science fiction a couple of years earlier—talking, believe it or not, about ectogenesis.

But it’s where Bernal takes the idea next that is so interesting. Like Haldane’s, his book is one of the founding texts of transhumanism: the idea that humanity should improve its species. He envisions a small sense organ for detecting wireless frequencies, eyes for infrared, ultraviolet and X-rays, ears for supersonics, detectors of high and low temperatures, of electrical potential and current.

With that wireless sense Bernal imagined how humanity could be in touch with others, regardless of distance. Even fellow humans across the galaxy in separate biospheres could be within reach. And, like several of the series’ authors, he imagines such interconnection as augmenting human intelligence, producing what science fiction writers have called a hive mind, or what Haldane calls a “super-brain.”

It’s not AI, exactly, because its components are natural: individual human brains. And in some ways, coming from Marxist intellectuals like Haldane and Bernal, what they’re imagining is a particular realization of solidarity—workers of the world uniting, mentally. Bernal even speculates that if thoughts could be broadcast to other minds in this way, then they would continue to exist even after the brain that thought them had died. In this he offers a form of immortality guaranteed by science instead of religion.

Blind spots

Bernal also imagined the world wide web more than 60 years before its invention by Tim Berners Lee. What neither Bernal, nor any of the To-Day and To-Morrow contributors could imagine, though, was the computers needed to run it—even though they were only about 15 years away when he was writing. And it is these inconceivable computers that have so ramped up and transformed early attempts at futurology into the industry it is today.

How can we account for this computer-shaped hole at the center of so many of these prophecies? It was partly that mechanical or “analogue” computers such as punched card machines and anti-aircraft gun “predictors” (which helped gunners aim at rapidly moving targets) had gotten extremely good at calculation and information retrieval. So good, in fact, that inventor and To-day and To-morrow author H Stafford Hatfield thought what was needed next was a “mechanical brain.”

A Colossus codebreaking computer, 1943. (Wikimedia Commons/)

So these thinkers could see that some form of artificial intelligence was required. But even though electronics were developing rapidly, in radios and even televisions, it didn’t seem to occur to people that if you wanted to make something that functioned like a brain it would need to be electronic, rather than mechanical or chemical. This was exactly the moment in history when neurological experiments by Edgar Adrian and others in Cambridge began to show that electrical impulses actually made the human brain tick.

Just 12 years later, in 1940—before the development of the first digital computer, Colossus at Bletchley Park—it was possible for Haldane (again) to see that what he called “Machines that Think” were beginning to appear, combining electrical and mechanical technologies. In some ways our situation is comparable, as we sit poised just before the next great digital disruption: AI.

Bernal’s book is a fascinating example of just how far extended future thinking can go. But it also shows where it reaches its limits. If we can understand why the To-Day and To-Morrow authors were able to predict biospheres, mobile phones, and special effects, but not the computer, the obesity crisis, or the resurgence of religious fundamentalisms, then maybe we can catch some of the blind spots in our own forward vision and horizon scanning.

Yesterday and today

The pairing of scientific knowledge and imagination in these books created something unique—a series of hypotheticals somewhat lodged between futurology and science fiction. It is this sense of hopeful imagination that I think urgently needs to be injected back into today’s predictions.

As I have mentioned, computer modeling of the future mainly happens in businesses or organizations. Banks and other financial companies want to anticipate shifts in the markets. Retailers need to be aware of trends. Governments need to understand demographic shifts and military threats. Universities want to drill down into the data of these or other fields to try to understand and theorize what is happening.

To do this kind of complex forecasting well, you have to be a fairly large corporation or organization with adequate resources. The bigger the data pool, the hungrier the exercise becomes for computing power. You need access to expensive equipment, specialist programmers, and technicians. Information that citizens freely offer to companies such as Facebook or Amazon is sold on to other companies for their market research—as many were shocked to discover in the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

The main techniques which today’s governments and industries use to try to prepare for or predict the future—horizon scanning and scenario planning—are all well and good. They may help us nip wars and financial crashes in the bud (though rather obviously, they don’t always get it right either). But as a model for thinking about the future more generally, such methods are profoundly reductive.

They’re all about maintaining the status quo. Any interesting ideas or innovative speculations about anything other than risk avoidance are likely to get pushed aside. The group nature of think-tanks and foresight teams also has a leveling down effect. Future thinking by committee has a tendency to come out in bureaucratese: bland, impersonal, insipid. The opposite of science fiction.

Which is perhaps why science fiction needs to put its imagination in hyperdrive: to boldly go where the civil servants and corporate drones are too timid to venture. To imagine something different. Some science fiction is profoundly challenging in the sheer otherness of its imagined worlds.

That was the effect of “2001” or “Solaris,” with their imagining of other forms of intelligence, as humans adapt to life in space. Kim Stanley Robinson takes both ideas further in his novel “2312,” imagining humans with implanted quantum computers and different colony cultures as people find ways of living by building mobile cities to keep out of the sun’s heat on Mercury, terraforming planets, and even hollowing out asteroids to create new ecologies as art works.

When we compare To-Day and To-Morrow with the kinds of futurology on offer nowadays, what’s most striking is how much more optimistic most of the writers were. Even those like Haldane and Vera Brittain (the author of a superb volume on women’s rights in 1929) who had witnessed the horrors of modern technological war, saw technology as being the solution rather than the problem.

Imagined futures nowadays are more likely to be shadowed by risk and anxieties about catastrophes, whether natural (asteroid collision, mega-tsunami) or man-made (climate change and pollution). The damage industrial capitalism has inflicted on the planet has made technology seem like the enemy. Certainly, until anyone has any better ideas, reducing carbon emissions, energy waste, pollution, and industrial growth seems like our best bet for survival.

Imagining positive change

The only thing that looks likely to convince us to change our ways is the dawning conviction that we have left it too late; that even if we cut emissions to zero now, global warming has almost certainly passed the tipping point and will continue to rise to catastrophic levels regardless of what we do to try to stop it.

That realization is beginning to generate new ideas about technological solutions, like ways of extracting carbon from the atmosphere or of artificially reducing sunlight over the polar ice caps. Such proposals are controversial, and sometimes attacked as encouragement to carry on with Anthropocene vandalism while someone else clears up our mess.

But they might also show that we are at an impasse in future thinking, and are in danger of losing the ability to imagine positive change. That too is where comparison with earlier attempts to predict the future might be able to help us. Where the modernism of the 1920s and 30s was very much oriented towards the future, we are more obsessed with the past, with nostalgia. Ironically, the very digital technology that came with such a futuristic promise is increasingly used in the service of heritage and the archive. Cinematic special effects are more likely to deliver feudal warriors and dragons, rather than rockets and robots.

But if today’s futurologists could get back in touch with the imaginative energies of their predecessors, perhaps they would be better equipped to devise a future we could live with.

Max Saunders is a Professor of English at King’s College London. The findings of this research were first covered by The Conversation as part of its Insights series.

Written By Max Saunders/The Conversation

0 notes

Link

(Joshua Paladino, Liberty Headlines) Instagram censored a pro-life meme that exposed abortion as “genocide” against the black community, Radiance Foundation reported.

Clueless @dailydot @draytontiffanie denounce our latest meme on historical @PPFA / KKK comparison & invoke Fannie Lou Hamer. The anti-poverty activist was a victim of the same vile pseudoscience that birthed PPFA–eugenics. She called abortion “genocide”. https://t.co/nGB5Gnqnsz pic.twitter.com/0CqCHhksed

— Radiance Foundation (@lifehaspurpose) July 19, 2018

Ryan Scott Bomberger, the chief creative officer and co-founder of the Radiance Foundation, posted the meme on July 11, and Instagram removed it shortly thereafter.

“The meme juxtaposes the vile, racist and elitist worldview of those in white coats who unapologetically set out to control the population with the same racism that drove the murderous acts of a bunch of cowards in white sheets,” wrote Bomberger, who is black.

Instagram — a video- and photo-sharing platform owned by Facebook — said they remove “extreme graphic violence,” “posts that encourage violence” based on race, ethnicity or religion, and “specific threats of physical harm, theft, vandalism, or financial harm.”

Instagram did not specify which community guideline Bomberger violated, though the company threatened to restrict or disable his account if he violates the arbitrary and vague guidelines again.

The meme even linked to an article titled, “Politifact aborts the facts about abortion being the leading killer of black lives,” to justify the statement.

Abortion takes 259,336 black lives every year — more than HIV, drugs, homicides, diabetes, accidents, cancer, heart disease, more than the top 15 leading causes of death combined.

He also justified the comparison of Planned Parenthood to the Ku Klux Klan.

Bomberger included NAACP statistics, showing the KKK lynched about 3,500 African Americans from 1882 to 1968, while 1,300 lynchings were against white people.

In comparison, abortionists at Planned Parenthood take the lives of about 247 unborn black babies every day.

“So, the meme is the problem, not the genocide. And yes, I used the word genocide. Fannie Lou Hamer did, too. Oh, and so did pre-pro-abortion Rev. Jesse Jackson,” Bomberger wrote. “What do you call it when more black babies are killed by abortion than are born alive? This is the grim reality in NYC where Planned Parenthood was spawned.”

Original Source -> Instagram Censors Pro-Life Meme Calling Out Planned Parenthood

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Text

New Books (September Part II)

Sorted by Call Number / Author. New books are shelved in the "New Books" Section of the Slaughter Reading Room under the superhero posters. Books marked "On Reserve" are in Mrs VanHorn's office for use by faculty or students in particular classes-- just ask us if you can't find something. Librarians like to help you.

Thank you to the Wiatreks and Dr. Thomas for donating many of these materials!

142.78 B

Barrett, William, 1913-. Irrational man : a study in existential philosophy. Anchor Books ed. New York : Anchor Books, 1990.

Addresses existentialist philosophy in America during the 1990s with a discussion of the roots of existentialism and personal views from some of the foremost existentialists such as Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Sartre.

174.28 W

Washington, Harriet A. Medical apartheid : the dark history of medical experimentation on Black Americans from colonial times to the present. 1st Anchor Books (Broadway Books) ed. New York : Anchor Books, 2008.

The first comprehensive history of medical experimentation on African Americans. Starting with the earliest encounters between Africans and Western medical researchers and the racist pseudoscience that resulted, it details the way both slaves and freedmen were used in hospitals for experiments conducted without a hint of informed consent--a tradition that continues today within some black populations. It shows how the pseudoscience of eugenics and social Darwinism was used to justify experimental exploitation and shoddy medical treatment of blacks, and a view that they were biologically inferior, oversexed, and unfit for adult responsibilities. New details about the government's Tuskegee experiment are revealed, as are similar, less well-known medical atrocities conducted by the government, the armed forces, and private institutions. This book reveals the hidden underbelly of scientific research and makes possible, for the first time, an understanding of the roots of the African American health deficit.--*** Recommended by Visiting Writer Kwoya Fagin Maples

180 A

Adamson, Peter. Classical Philosophy : A history of philosophy without any gaps. Oxford, UK : Oxford UP, 2014.

180 A

Adamson, Peter, 1972- author. Philosophy in the Hellenistic and Roman worlds : a history of philosophy without any gaps. First edition.

Peter Adamson offers an accessible, humorous tour through a period of eight hundred years when some of the most influential of all schools of thought were formed: from the third century BC to the sixth century AD. He introduces us to Cynics and Skeptics, Epicureans and Stoics, emperors and slaves, and traces the development of Christian and Jewish philosophy and of ancient science. Chapters are devoted to such major figures as Epicurus, Lucretius, Cicero, Seneca, Plotinus, and Augustine. But in keeping with the motto of the series, the story is told 'without any gaps, ' providing an in-depth look at less familiar topics that remains suitable for the general reader. For instance, there are chapters on the fascinating but relatively obscure Cyrenaic philosophical school, on pagan philosophical figures like Porphyry and Iamblichus, and extensive coverage of the Greek and Latin Christian Fathers who are at best peripheral in most surveys of ancient philosophy. A major theme of the book is in fact the competition between pagan and Christian philosophy in this period, and the Jewish tradition also appears in the shape of Philo of Alexandria. Ancient science is also considered, with chapters on ancient medicine and the interaction between philosophy and astronomy. Considerable attention is paid also to the wider historical context, for instance by looking at the ascetic movement in Christianity and how it drew on ideas from Hellenic philosophy. From the counter-cultural witticisms of Diogenes the Cynic to the subtle skepticism of Sextus Empiricus, from the irreverent atheism of the Epicureans to the ambitious metaphysical speculation of Neoplatonism, from the ethical teachings of Marcus Aurelius to the political philosophy of Augustine, the book gathers together all aspects of later ancient thought in an accessible and entertaining way.

301 C

Hill Collins, Patricia, author. Intersectionality.

305 H

Hancock, Ange-Marie, author. Intersectionality : an intellectual history.

Intersectionality theory has emerged over the past thirty years as a way to think about the avenues by which inequalities (most often dealing with, but not limited to, race, gender, class and sexuality) are produced. Rather than seeing such categories as signaling distinct identities that can be adopted, imposed or rejected, intersectionality theory considers the logic by which each of these categories is socially constructed as well as how they operate within the diffusion of power relations. In other words, social and political power are conferred through categories of identity, and these identities bear vastly material effects. Rather than look at inequalities as a relationship between those at the center and those on the margins, intersectionality maps the relative ways in which identity politics create power. Though intersectionality theory has emerged as a highly influential school of thought in ethnic studies, gender studies, law, political science, sociology and psychology, no scholarship to date exists on the evolution of the theory. In the absence of a comprehensive intellectual history of the theory, it is often discussed in vague, ahistorical terms. And while scholars have called for greater specificity and attention to the historical foundations of intersectionality theory, their idea of the history to be included is generally limited to the particular currents in the United States. This book seeks to remedy the vagueness and murkiness attributed to intersectionality by attending to the historical, geographical, and cross-disciplinary myopia afflicting current intersectionality scholarship. This comprehensive intellectual history is an agenda-setting work for the theory.