#san三 is third/three

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

无挂碍 - 音速行星 Unencumbered - Sonic Planet

制作人: 泰然 Producer: Tai Ran

三娃嘞 Sanwa le

你杳无音信 I've never heard from you

一走就十载 You've been gone for ten years

你喜欢的姑娘 The girl you like

嫁了个好人 Married a good man

去年生了双胞胎 She gave birth to twins last year

你养的小黑狗 The little black puppy you raised

变成了老黑狗 Turned into an old black dog

就快要爬不起来 She's about to die

逢人都有常问 People always ask

你何时归来 When are you coming back

三娃嘞 Sanwa Le

你杳无音信 I've never heard from you

一走就二十载 You've been gone for 20 years

你种的树苗苗 The saplings you planted

长成了大树 Have grown into big trees

年年结出果子来 Every year they bear fruits

对面的山坡坡 On the other side of the mountain

油菜花漫山遍野 Rapeseed blossoms are everywhere

金灿灿的开 Blooming with gold

你二哥他在问 Your second brother is asking

你何时归来 When will you come back?

三娃嘞 Sanwa le

你杳无音信 I haven't heard a word from you

一走就三十载 You've been gone for 30 years

你二哥两爷子战死沙场 Your second brother and your dad died in battle

就���掩埋没有回来 They were buried on the spot and never came back

娘亲她泪洗面眼浑浊 Mom's eyes are clouded with tears

颤颤巍巍双鬓都斑白 She walks shakily and her hair is gray

她常年独坐村头 She sits alone in the village entrance all year round

你何时归来 When will you come back?

三娃嘞 Sanwa Le

你杳无音信 I haven't heard a word from you

转眼就四十载 It's been 40 years

娘走那天残阳似火 The sun was burning on the day mom passed away

天边有雁群展翅来 Wild geese spreading their wings in the sky

她说都回来接她了 She said they all came back for her

唯独其中寻你不在 Only you're not here

心有遗憾 She felt sorry for you

你何时归来 When will you come back?

三娃嘞 Sanwa Le

你杳无音信 I haven't heard a word from you

一走就五十载 You've been gone for 50 years

我弓腰驼背坡坡坎坎 I've been hunching over and walking uphill

力不从心走不快 I can't walk as fast as I'd like

想起带你下河抓鱼 I think of taking you to the river to catch fish

草鞋冲走笑出声来 We were laughing as our straw sandals washed away

我心头默默在念 I've been thinking of you

你何时归来 When will you come back?

何时归来 When will you come back?

何时归来 When will you come back?

何时归来 When will you come back?

何时归来 When will you come back?

何时归来 When will you come back?

何时归来 When will you come back?

何时归来 When will you come back?

何时归来 When will you come back?

#Youtube#china#synthwave#electronic music#the perspective of the lyrics is his big brother#sanwa is the nickname of the third child in a family#le嘞 is a modal particle#san三 is third/three#wa娃 is child/kid in chinese dialects#music

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

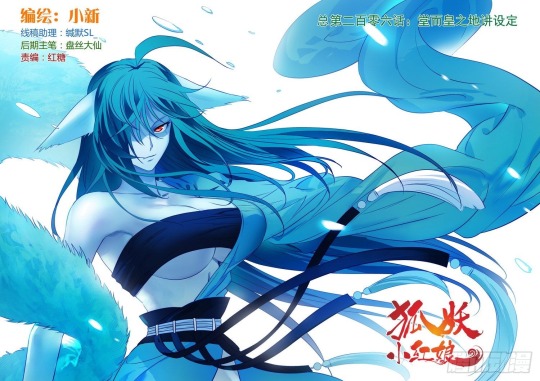

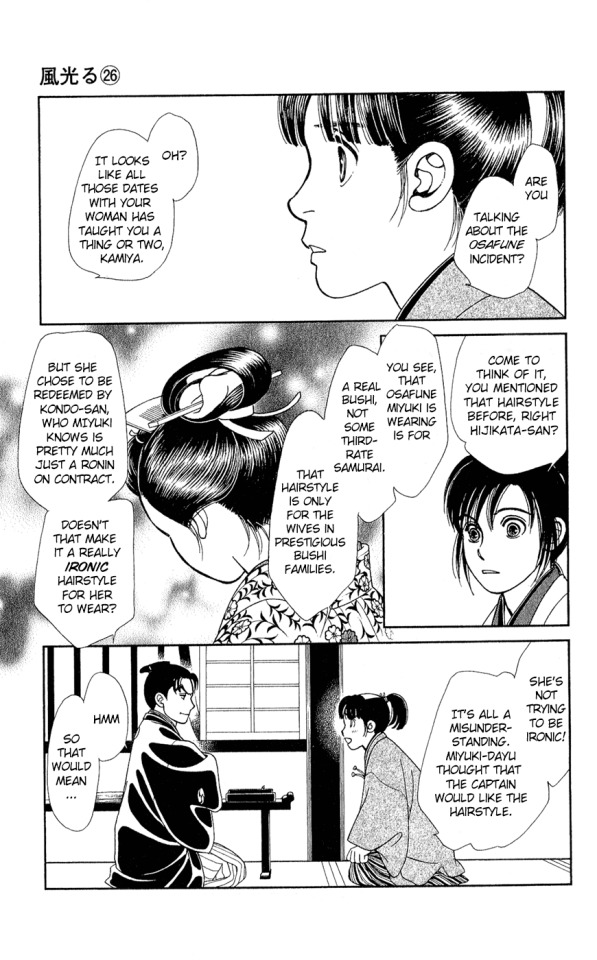

The Chinese Drama (Fake) Version DOES NOT EQUAL The Manhua & The Donghua (Original) Version !!!!

This is Fox Spirit Matchmaker !!!!

This is The Plight Tree !!!!

This is YueHong (Tushan Honghong x Dongfang Yuechu) !!!!

This is SanYa (Tushan Yaya x San Shaoye) !!!!

This is Tushan Rongrong !!!!

#狐妖小红娘#huyao xiao hongniang#fox spirit matchmaker#FSMM#FSMM Manhua#FSMM Donghua#The Plight Tree#Plight Tree#Tushan#The Three Sisters Of Tushan#Tushan Honghong#Tushan Yaya#Tushan Rongrong#The Third Young Master Of Aolai Kingdom#The Third Young Master#The Third Master#San Shaoye#Dongfang Yuechu#月红#YueHong#三雅#SanYa#Fox Spirit x Human Taoist#Fox Spirit x Monkey Spirit#Power Couple#Fox Spirit#Manhua#Donghua#庹小新#Tuo Xiaoxin

1 note

·

View note

Text

刺し違える sashichigaeru - This word is an expression used in traditional Japanese. In Japanese the term 'sashichigaru' refers to stabbing each other with a blade; it is a method of harming one person while risking harm to oneself or sacrificing one's life to kill the opponent. In essence, this indicates that while you may not emerge unscathed, you have the ability to wreak havoc on your opponent. So, to stab each other means that both you and the other person will die. This method is often employed as a desperate measure against a superior opponent. This word is often used in situations where people are accusing each other or disagreeing with each other or in a conflict. The origin of this word is not known, but it is believed to have originated in the world of swordsmanship and martial arts.

In swordsmanship training and warfare, it was necessary to read each other's attacks and skillfully avoid them in order to prevent oneself from being stabbed, while at the same time seeking to instantly stab through the opponent.

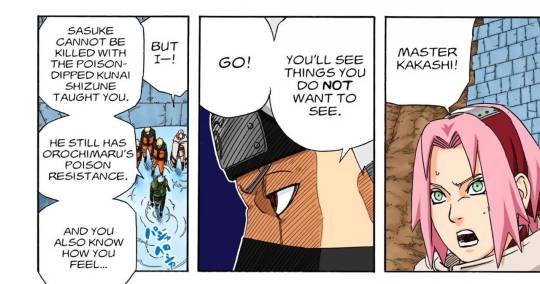

If I'm not mistaken this term was used by two people in the series, 1. Kakashi 2. Sakura

• Kakashi

KAKASHI: いくらあんたがあの三忍の一人でも...今のオレならアンタと差し違える��とくらいは出来るぞ...!

ikura anta ga ano san nin no ichi nin demo ... ima no ore nara anta to sashichigaeru koto kurai wa dekiru zo ...!

Even if you're one of the three ninja... At least, I can kill you as you kill me/stab at each other...!

差し違える= kill each other/stabbing each other (or try to assasinate) → get fight back → both dead.

差し違える - It was originally used when a samurai charges towards an opponent with a sword or short sword. In such a case, you may be able to kill the other person, but there is a high possibility that the other person will also be able to kill you at the same time. It shows the determination that it doesn't matter. This is also a desperate strategy/tactic.

差し (sashi) not only means two people facing each other, but also ``present'' and ``send back''. It is used with verbs to emphasize the meaning or adjust the tone, such as in ``replace.''

刺し is a continuous form of 刺す. It is mainly used to mean to pierce something with a sharp point.

Even though he knew that if he had a fight with one of the Sannin, he would probably lose, but he felt the need to protect Sasuke from Orochimaru

But....

When Kakashi saw himself decapitated when he stood between Sasuke and Orochimaru:

ORO: やってみれば? できればだけど...

yattemireba ? dekireba da kedo ...

Why not try it? If you can, that is...

this expression could come across as dismissive. Using such expressions can come across as sarcastic and undermine the other person's confidence or abilities.

KAKASHI: ...くつ 刺し違える...!? バカか...オレは...!!!

ku....sashichigaeru...!? baka ka ...ore wa ...!!!

Ugh...Kill you as you kill me/stab at each other...!? Am I an idiot...!!!

くつ...!! - Uses when Someone probably noticed the impossibility to deal with something which is faced now unexpectedly.

Often, small sweat drops are drawn on the cheek of characters to make their expression appears more tense than normal. The more sweat drops there are, the stronger the anxiety or nervous.

Kakashi was initially confident in facing Orochimaru, but his confidence changed when Orochimaru released his killer intent.... it was enough to scare Kakashi

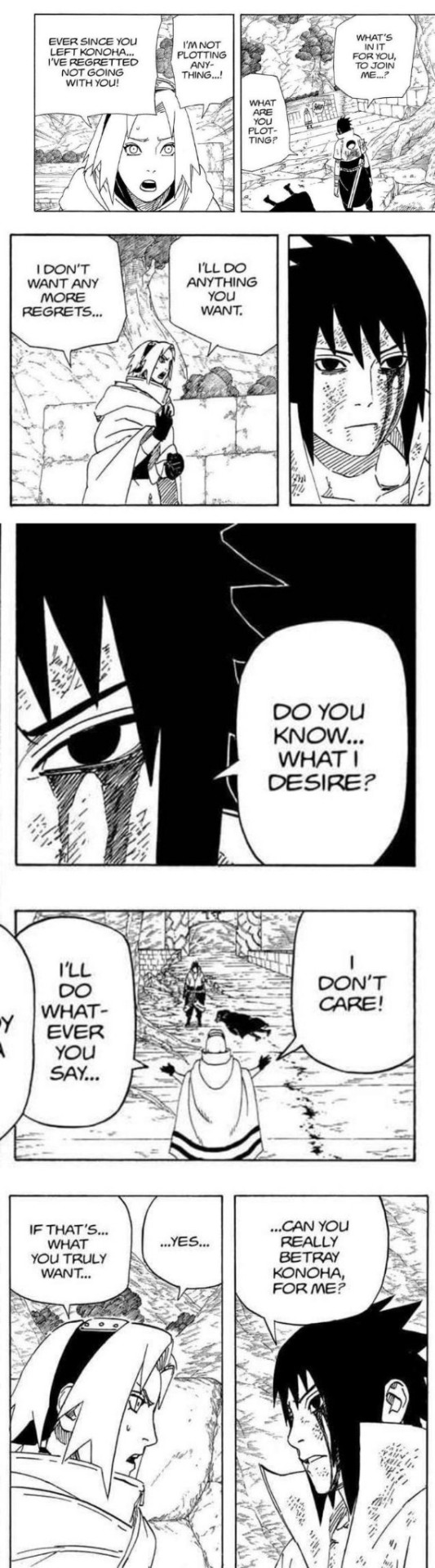

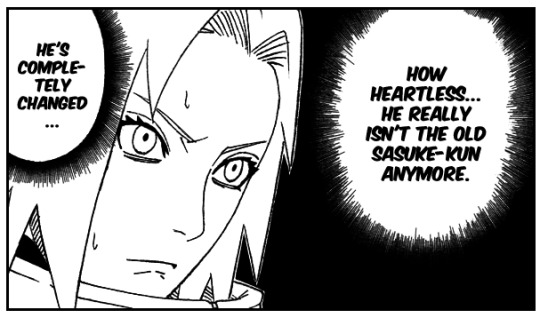

• Sakura

In 482, Sasuke was about to finish the job to kill his teammate karin when Sakura suddenly appears. In which case, Sasuke is already suspicious of her motives.

At first, Sakura lied about betraying Konoha. Second, she lied about joining Sasuke even though she was there to kill him. Third, she doesn't really care what Sasuke really wants and why he's doing this.

Her first remark about Sasuke is "He's completely changed"...well, yes...he's changed...but has she ever tried to figure out why he's changed???

She must have been in a hurry to get rid of Sasuke before others got rid of him first. [Sakura chose a sleeping gas bomb to put Kiba, Lee, and the others to sleep, and she left them there without even make sure that they were safe and not exposed to enemies. But...Kakashi was the one who carries Kiba and the others to a safe place]

Sasuke says, "Try to finish off Karin," and she quietly approaches Karin with a kunai to "stab Sasuke."

He saw through her lies and only see her as a "hated enemy of Konoha" now... rather than a former Team mate. He didn't even warn her but instead goes behind her back and wanted to finish her off. Sakura's eyes widened with shock and couldn't even run away (even though medical ninjas are supposed to be trained to avoid enemy attacks). I guess she never expected Sasuke to do something like that. It was Kakashi who was able to stop it just in the nick of time.

Even though she was told to stay out of the way, Sakura appeared again with a kunai in hand...but she fails to stab Sasuke. Twice.

Kakashi, who has decided to confront Sasuke, orders Naruto and Sakura to leave the place. Kakashi then interrupted Sakura's words... "Sasuke won't die from the poisoned kunai you learned from Shizune... He still has orochimaru's poison resistance..."

Specifically, he tells Sakura the realistic facts: "Sasuke won't die from your poison kunai. That poison won't work on Sasuke, so it's useless"

The fact that Sakura, a medical ninja, tried to kill Sasuke with a kunai...means it's easy to determine that the kunai was a poisoned kunai. "Poison" is a typical choice for a medical ninja. so the fact that Sakura chose "poison" is also evidence that she was "seriously thinking about getting rid of Sasuke."

In chapter 311, Sakura, who came to visit Kakashi at Konoha Hospital, said to him,

Sakura knew that Orochimaru might have been given drugs or some kind of forbidden jutsu to train Sasuke. Therefore, she should have known that "Sasuke might also immune to poison". Sakura herself had said that to Kakashi. So, Sakura naturally knows this but she chose the poison she had learned from Shizune to coat the kunai with to kill Sasuke. In general, even Kakashi knew that "Sasuke was resistant to poison," but... all of a sudden, she forgot all the facts she remembers and decided to kill Sasuke with just a Poisoned Kunai.

So Sakura's attempt to kill him would have been futile whether she stabbed him or not. Instead of bothering to find out why Sasuke suddenly acted like that, she concocts this plan where she lies about liking Naruto to get him to stop chasing Sasuke. She then drugs her comrades and leaves them unconscious in the forest and tries to stab Sasuke not once but twice with her poisoned kunai. Again, she fails to even come close to her own goals that she has set for herself. She constantly making a fool out of herself, crying pathetically and needing to be rescued. And She heard Naruto talking to Sasuke that Tobi had told him about "the truth about Itachi" and heard Sasuke ranting about how Konoha was responsible for his misery, but she never bothered to ask anyone about it.

In chapter 693, When Sasuke tells Naruto to come with him, we sees this angry look on her face and starts screaming about her feelings. However what's important to notice is this highlighted part when she is having this meltdown :

寄りそうことも刺し違えることもできずに...

yorisō koto mo sashichigaeru koto mo dekizu ni...

I can't get close to you or stab at each other...

I think she clearly referring to Naruto. Naruto is the only one who gets through to Sasuke, close to him, and he even said during the 5 Kage Summit that he'd bear the burden of Sasuke's hatred and they'd die together [double-suicide]. And Sakura is clearly upset. Sakura is also very telling of her jealousy of Naruto and Sasuke's bond. She knows Naruto can do things for Sasuke and get a reaction out of him, but she can't. Only Naruto could do these two things, not her. All this time all she could do was cry and beg.

Then Kakashi says that Sakura still loves him despite Sasuke trying to kill her, while conveniently omitting the fact that Sakura went there to kill Sasuke. Kakashi, who not only admits to not understand Sasuke, but he also clearly doesn't understand Sakura either. And She doesn't understand Sasuke either.

#from the drafts#my stuff#edited: Sorry I wrote Sasuke instead of Sakura in the second to last para.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

四手辛夷[Shidekobushi] Magnolia stellata

四手[Shide] : Sacred paper streamer used in Shintō

辛夷[Kobushi] : M. kobus

The petals are usually a rather pale pink, but some are darker, and their buds and the beginning of bloom are even darker.

Shide is also written as 垂, 紙垂, 椣 or 幣. But 幣 is most commonly read as nusa or hei, and shide and nusa are slightly different. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gohei

糸子は黙って聴いている。小野さんも黙って聴いている。花曇りの空がだんだん擦り落ちて来る。重い雲がかさなり合って、弥生をどんよりと抑えつける。昼はしだいに暗くなる。戸袋を五尺離れて、袖垣のはずれに幣辛夷の花が怪しい色を併べて立っている。木立に透かしてよく見ると、折々は二筋、三筋雨の糸が途切れ途切れに映る。斜めにすうと見えたかと思うと、はや消える。空の中から降るとは受け取れぬ、地の上に落つるとはなおさら思えぬ。糸の命はわずかに尺余りである。

[Itoko wa damatte kiite iru. Ono san mo damatte kiite iru. Hanagumori no sora ga dandan zuriochite kuru. Omoi kumo ga kasanariatte, yayoi wo don'yori to osaetsukeru. Hiru wa shidai ni kuraku naru. Tobukuro wo go shaku hanarete, sodegaki no hazure ni shidekobushi no hana ga ayashii iro wo narabete tatte iru. Kodachi ni sukashite yoku miruto, oriori wa futasuji, misuji ame no ito ga togire togire ni utsuru. Naname ni sū to mietaka to omouto, haya kieru. Sora no naka kara furu towa uketorenu, chi no ue ni otsuru towa naosara omoenu. Ito no inochi wa wazuka ni shaku amari dearu.]

Itoko listens in silence. Ono-san also listens in silence. The hazy sky when sakura blooms gradually descend. Heavy clouds pile up, weighing down Yayoi(the third month of the lunar calendar) with a gloomy mood. The daytime gradually darkens. Goshaku(5-shaku, about 1.5 meters) away from the Tobukuro(box for containing shuttersdoor pocket,) on the Sodegaki(low fence flanking a gate or entrance,) the flowers of Shidekobushi stand in a line of mysterious colors. Looking closely through the trees, two or three intermittent threads of rain are seen on occasion. It was thought they appeared (to run) momentarily in a diagonal direction, but then disappear right away. It is difficult to believe that they are falling from the sky, much less that they are falling to the ground. The life of the threads lasts just over Isshaku(1-shaku, about 30 centimeters.) 虞美人草[Gubijinsō](Field Poppy) by 夏目 漱石[Natsume Sōseki] Source: https://www.aozora.gr.jp/cards/000148/files/761_14485.html https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/219618541 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HwO1kruewsA

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Numbers in Japanese

0(zero) : 零(れい/rei or ゼロ/zero)

1(one) : 一(いち/ichi)

2(two) : 二(に/ni)

3(three) : 三(さん/san)

4(four) : 四(よん/yon or し/shi)

5(five) : 五(ご/go)

6 (six) : 六(ろく/roku)

7(seven) : 七(なな/nana or しち/shichi)

8(eight) : 八(はち/hachi)

9(nine) : 九(きゅう/kyu or く/ku)

10(ten) : 十(じゅう/ju)

11(eleven) : 十一(じゅういち/ju-ichi)

12(twelve) : 十二(じゅうに/ju-ni)

:

20(twenty) : 二十(にじゅう/ni-ju)

21(twenty-one) : 二十一(にじゅういち/niju-ichi)

22(twenty-two) : 二十二(にじゅうに/niju-ni)

:

30(thirty) : 三十(さんじゅう/san-ju)

31(thirty-one) : 三十一(さんじゅういち/sanju-ichi)

:

40(forty) : 四十(よんじゅう/yon-ju or しじゅう/shi-ju)

50 (fifty) : 五十(ごじゅう/go-ju)

60 (sixty) : 六十(ろくじゅう/roku-ju)

70(seventy) : 七十(ななじゅう/nana-ju or しちじゅう/shichi-ju)

80(eighty) : 八十(はちじゅう/hachi-ju)

90(ninety) : 九十(きゅうじゅう/kyu-ju)

100(hundred) : 百(ひゃく/hyaku)

101(one hundred one) : 百一(ひゃくいち/hyaku-ichi)

111(one hundred eleven) : 百十一(ひゃくじゅういち/hyaku-ju-ichi)

1,000(thousand) : 千(せん/sen)、一千(いっせん/issen)

10,000(ten thousand) : 万(まん/man)、一万(いちまん/ichi-man)

100,000(one hundred thousand) : 十万(じゅうまん/ju-man)

1,000,000(one million) : 百万(ひゃくまん/hyaku-man)

10,000,000(ten million) : 千万(せんまん/sen-man)、一千万(いっせんまん/issen-man)

100,000,000(one hundred million) : 億(おく/oku)、一億(いちおく/ichi-oku)

1,000,000,000(one billion) : 十億(じゅうおく/ju-oku)

10,000,000,000(ten billion) : 百億(ひゃくおく/hyaku-oku)

100,000,000,000(one hundred billion) : 千億(せんおく/sen-oku)、一千億(issen-oku)

1,000,000,000,000(one trillion) : 兆(ちょう/cho)、一兆(いっちょう/iccho)

Decimal number : 小数(しょうすう/Sho-su)

Point : 点(てん/ten, しょうすうてん/shosu-ten)

ex. 1.2345(one point two three four five) : いちてんにさんよんご/Ichi-ten-ni-san-yon-go or いってんにさんしご/Itten-ni-san-shi-go

Fraction : 分数(ぶんすう/bun-su)

ex. 1/5(one fifth) : 五分の一(ごぶんのいち/go-bun-no-ichi)

2/3(two third) : 三分の二(さんぶんのに/san-bun-no-ni)

1/2(half) : 半分(はんぶん/han-bun) or 二分の一(にぶんのいち/ni-bun-no-ichi)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

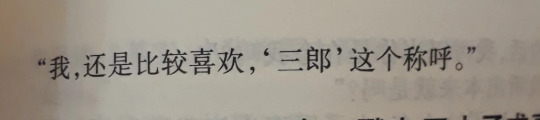

The Lost Tomb 2: Ep. 1

Okay, casting for third Uncle this season is very different. Gonna take me a minute to get used to this.

Wait is San (三) part of his actual name? I've been calling him Third Uncle because that makes more sense to me as a translation than Uncle Three, if he's actually Wu Xie's Third Uncle. But now the subtitles for this season are saying Uncle San Xing. Should I be calling him Uncle Three???

Right the Uncle had been kidnapped at the end of season 1.

Nice white backpack Wu Xie. Perfect for tomb raiding.

Wait, was Xiao-ge actually there or was Wu Xie just seeing similarities in his and the Zhang guy's movements?

Again a shot where it looks like Xiao-ge is there. (I'm assuming the emo haired guy dressed all in black is Xiao-ge.) Is the Zhang character a disguise???

Okay no, that's just a sailor, not Xiao-ge. *crying* But he was there on the ghost ship.

The first episode of this season was already creepier than the last season was.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vajrabhairava (Buddhist Deity) - (Retinue Figure)

Tibetan: རྡོ་རྗེ་འཇིགས་འབྱེད། Chinese: 金刚大威德(佛教本尊)

(item no. 69404)

Origin Location Tibet

Date Range 1700 - 1799

Lineages Gelug and Buddhist

Size 87.63x55.88cm (34.50x22in)

Material Ground Mineral Pigment on Cotton

Collection Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

Interpretation / Description

Moha Yamari, a retinue deity in the mandala of the complex meditational deity known as Vajrabhairava. This single composition belongs to a set of at least nine paintings, if not more, depicting all of the principal figures of a Vajrabhairava mandala.

Moha Yamari is a directional retinue deity located in the Eastern direction of the Vajrabhairava mandala. (See an example in the mandala painting number #65463). He has three faces and six hands, wrathful in appearance, white in colour and in a standing posture embracing a consort. His proper right face is blue and the left red. The first pair of hands hold a curved knife and skullcup. the second pair holds a sword and flower and the third a golden wheel and a green jewel.

As a principal meditational deity Vajrabhairava, sometimes referred to as Yamantaka, belongs to the Bhairava and Yamari class of tantras and specifically arises from the Vajrabhairava Root Tantra (Tib.: jig je tsa gyu). The Sanskrit source text belongs to the method (father) classification of Anuttaryoga Tantra. The practice of Vajrabhairava is common to the three new (sarma) Schools of Tibetan Buddhism from the 11th century onwards: Sakya, Kagyu and Gelug. Among the Sakya it is counted as one of the four main tantric deities along with Hevajra, Guhyasamaja and Chakrasamvara (Tib.: gyu de shi). Amongst the various Kagyu Schools the Drigungpa are strong upholders of the practice. There are numerous forms and styles of practice from the very complex with multiple heads and arms along with numerous deities to the very concise with a single Heruka form and no attendant retinue deities. From amongst the many different lineages of teaching transmissions to enter Tibet the main ones were those of Rwa Lotsawa and Mal Lotsawa.

Lineage: Shri Vajrabhairava, Jnana Dakini, Mahasiddha Lalitavajra, Amoghavajra, Yeshe Jungne Bepa, Mahasiddha Padmavajra, Marmedze Srungwa, Rwa Lotsawa Dorje Drag, Rwa Chorab, Rwa Yeshe Sengge, Rwa Bum Seng, Rongpa Gwalo Namgyal Dorje, Rongpa Sherab Sengge, Lamdrepa Yeshe Palwa, Je Sonam Lhundrup, Choje Dondrup Rinchen, Je Tsongkapa Lobzang Dragpa (1357-1419), etc.

Jeff Watt 4-2009

摩哈亞瑪利 (Moha Yamari) 是複雜冥想神靈金剛大威德 (Vajrabhairava) 的曼陀羅中的眷屬神。這幅作品屬於至少九幅畫作的系列,甚至更多,描繪了金剛曼陀羅的所有主要人物。

摩哈耶瑪利 (Moha Yamari) 是位於金剛壇城東方的一位方位眷屬神。 (參見曼陀羅畫編號#65463 中的範例)。他有三面六臂,面容憤怒,膚色白色,站立姿勢,懷抱明妃。他的右臉是藍色的,左臉是紅色的。第一雙手握著彎刀和顱碗。第二對手持寶劍和花朵,第三對手持金輪和綠寶石。

作為主要的禪定神祇,大威德金剛(Vajrabhairava)有時也被稱為閻魔金剛(Yamantaka),屬於毘濕奴(Bhairava)和閻魔利(Yamari)類密宗,具體而言,源自大威德金剛根本密宗(藏文:jig je tsa gyu)。梵文原文屬於無上瑜珈續的方法(父)類別。�� 11 世紀以來,大威德金剛的修行為藏傳佛教三個新宗派(薩迦派、噶舉派和格魯派)所共有。在薩迦派中,它與喜金剛、密集金剛和勝樂金剛(藏文:gyu de shi)一起被視為四大主要密宗神祇之一。在噶舉派的各個流派中,直貢巴是這項修持法門的堅定支持者。修持的形式和風格多種多樣,從有多個頭和手臂以及眾多神像的複雜形式,到只有單一嘿嚕嘎形式且沒有侍從神像的簡潔形式。在進入西藏的眾多不同傳承的教法中,主要的傳承是 Rwa Lotsawa 和 Mal Lotsawa。

傳承: 威德金剛、智空行母、拉利塔金剛大成就者、不空金剛、耶喜榮涅貝巴、大成就者蓮花金剛、Marmedze Srungwa、魯瓦洛薩瓦多傑扎、魯瓦喬拉、魯瓦耶喜森格、魯瓦範勝、榮巴瓜羅南傑多傑、榮巴謝拉森格、拉姆哲巴益西巴瓦、傑索南倫珠、秋傑頓珠仁欽、宗喀巴洛桑扎巴(1357-1419)等。

傑夫·瓦特 4-2009

1 note

·

View note

Text

Episode 27 : An Era of Humans / 第27話『人間の時代(Ningenno Jidai)』

*Green colored words are only in anime, not in original manga, and we usually call them "ani-ori(anime-original)".

武のおじいさん「確かに武の道に果てはない。極意へとまた一歩近づいたな。お主に教えることはもう何もない。」

Buno Ojiisan “Tashikani buno michini hatewa nai. Gokui-eto mata ippo chikazuitana. Onushini oshieru kotowa mo nanimo nai.”

Martial Old Man “The path of the warrior is without end. You’ve taken yet another step toward mastering its secrets. There is nothing left for me to teach you.”

シュタルク「それ毎日言ってるよね…?」

Shutaruku “Sore Mainichi itteru yone…?”

Stark “You say that every time.”

シュタルク「…あれ?フェルン?」

Shutaruku “…Are? Ferun?”

Stark “Huh? Fern?”

フェルン「むっすー」

Ferun “Mussū”

Fern “Hmph.”

シュタルク「ブチギレてる!?なんで!?怖い!!」

Shutaruku “Buchi-gire-teru!? Nande!? Kowai!!”

Stark “She’s pissed? Why?! I’m scared…”

フェルン「フリーレン様と喧嘩しました。」

Ferun “Furīren-samato kenka shimashita.”

Fern “Ms.Frieren and I had an argument.”

シュタルク「またなの… 最近そういうの多くない?次の第三次試験が最終試験なんだろ。喧嘩なんかしている場合じゃ――」

Shutaruku “Matanano… Saikin soiuno ookunai? Tsugino dai-sanji-shikenga saishu-shiken nandaro. Kenka nanka shiteiru baaija――”

Stark “Again? You’ve been arguing a lot recently, don’t you think? Isn’t the third test the final one? This is hardly the time to be squabbling.”

フェルン「今回ばかりは酷すぎます。零落の王墓での戦いで杖が壊れてしまったので、直しに行きたいとフリーレン様に伝えました。そうしたら、古い杖は捨てて新しい杖を買った方がいいと…」

Ferun “Konkai bakariwa hido-sugimasu. Reirakuno Obodeno tatakaide tsuega kowarete shimatta-node, naoshini ikitaito Furīren-samani tsutae-mashita. Soshitara, furui tsuewa sutete atarashii tsueo katta-hoga iito…”

Fern “She was truly awful this time. My staff broke in battle in the Ruins of the King’s Tomb, so I told Ms.Frieren I wanted to get it repaired. She told me it’d be better to buy a new staff than to repair my old one.”

シュタルク「あの杖だろ。粉々だからもう直せないって言っていたぜ。」

Shutaruku “Ano tsue daro. Kona-gona dakara mo naosenaitte itteitaze.”

Stark “You mean that staff, don’t you? She said it couldn’t be repaired since it was already in pieces.”

フェルン「それでもあれはハイター様からもらった杖です。小さな頃からずっと一緒だったんです。」

Ferun “Soredemo arewa Haitā-sama kara moratta tsue desu. Chiisana korokara zutto issho dattandesu.”

Fern “Still, Mr.Heiter gave me that staff. It’s been with me ever since I was little.”

シュタルク「フリーレンだぜ?悪気があったわけじゃ…」

Shutaruku “Furīren daze? Warugiga atta wakeja…”

Stark “We’re talking about Frieren, though. I doubt she meant any harm.”

フェルン「少なくとも私には、捨てるだなんて発想はありませんでした。」

Ferun “Sukunakutomo watashi-niwa, suteru danante hassowa arimasen-deshita.”

Fern “At the very least, I never even would have thought of throwing it away.”

ーーーーー

カンネ「次の一級試験まで三年か…三年は長いよね。」

Kanne “Tsugino ikkyu-shiken made san-nenka… San-nenwa nagai-yone.”

Kanne “Three years until the next first-class mage exam, huh? Three years is a long time.”

ラヴィーネ「いつもみたいに馬鹿にしろよ。」

Ravīne “Itsumo mitaini bakani shiroyo.”

Lawine “Just make fun of me like you always do.”

カンネ「馬鹿にしてほしいの?」

Kanne “Bakani shite hoshiino?”

Kanne “Do you want me to?”

ラヴィーネ「…いいや。」

Ravīne “…Iiya.”

Lawine “No.”

カンネ「じゃあ、ラヴィーネちゃん。なでなでしてあげよっか?」

Kanne “Jaa Ravīne-chan. Nade-nade shite ageyokka?”

Kanne “In that case, Little Miss Lawine, shall I pat your head?”

カンネ「おっ?やんのか?」

Kanne “O? Yannoka?”

Kanne “What? You wanna fight?”

ラヴィーネ「早くしろ。」

Ravīne “Hayaku shiro.”

Lawine “Hurry up.”

カンネ「…こりゃ重症だね。」

Kanne “…Korya jushodane.”

Kanne “You’re in really rough shape.”

カンネ「…あ、フリーレンだ。」

Kanne “…A, Furīrenda.”

Kanne “Hey, it’s Frieren.”

カンネ「何その袋?」

Kanne “Nani sono fukuro?”

Kanne “What’s with the bag?”

ーーーーー

リヒター「おい。いつまでいるつもりだ。俺はもう試験に落ちたんだ。もう他人だろう。商売の邪魔だから帰れ。」

Rihitā “Oi. Itsumade iru tsumorida. Orewa mo shikenni ochitanda. Mo tanin daro. Shobaino jama-dakara kaere.”

Richter “Hey, how long are you going to hang around here? I failed the test. There’s nothing keeping us together anymore. You’re interfering with my business. Get out of here.”

デンケン「儂は今、客としてここにいる。」

Denken “Washiwa ima kyakuto shite kokoni iru.”

Denken “I’m here as a customer.”

リヒター「…なら、さっさと選べ。」

Rihitā “…Nara sassato erabe.”

Richter “Then hurry up and choose something.”

ラオフェン「…あげる。」

Raofen “…Ageru.”

Laufen “You can have some.”

リヒター「いらん。」

Rihitā “Iran.”

Richter “I don’t want any.”

デンケン「今回は運が悪かったな。損な役回りだ。あの場にいた誰もがそうなる可能性があった。」

Denken “Konkaiwa unga warukattana. Sonna yakumawarida. Ano bani ita daremoga so naru kanoseiga atta.”

Denken “You were unlucky this time. You got the short end of the stick. It could’ve happened to anyone in that position.”

リヒター「負けは負けだ。俺の実力が足りなかった。だがその話は二度とするな。こう見えて俺は今、最悪な気分なんだ。」

Rihitā “Makewa makeda. Oreno jitsuryokuga tarinakatta. Daga sono hanashiwa nidoto suruna. Ko miete orewa ima saiakuna kibun nanda.”

Richter “A loss is a loss. I wasn’t strong enough. Either way, don’t bring that up again. I may seem fine, but I’m actually in a terrible mood right now.”

デンケン「それでも店はやるんだな。」

Denken “Soredemo misewa yarundana.”

Denken “But you opened your shop regardless.”

リヒター「デンケン。お前は知らないだろうが、どんな最悪な気分でも人は食っていくために働かなければならん。」

Rihitā “Denken. Omaewa shiranai-daroga, donna saiakuna kibundemo hitowa kutte-ikutameni hataraka-nakereba naran.”

Richter “Denken, you may not realize this, but people have to work to make a living no matter how foul their mood.”

デンケン「そうか。」

Denken “Soka.”

Denken “Is that right?”

リヒター「まあ、落ちたのが俺でよかったんじゃないのか。一級試験は三年に一度。デンケン。お前みたいな老いぼれに三年後はないかもしれないからな。」

Rihitā “Maa ochitanoga orede yokattanja nainoka. Ikkyu-shikenwa san-nenni-ichido. Denken. Omae mitaina oiboreni san-nengowa naikamo shirenai karana.”

Richter “Maybe it’s for the best that I’m the one who failed. The first-class mage exam is held once every three years. A decrepit old man like you might not be around three years from now.”

デンケン「…確かにな。」

Denken “…Tashikanina.”

Denken “You’re right.”

リヒター「言い返せ。」

Rihitā “Iikaese.”

Richter “Don’t agree with me.”

デンケン「リヒター、お前は本当に生意気な若造だ。権威を馬鹿にし、目的のためなら弱者を足蹴にすることも厭わない。とても褒められたような人間ではない。なのに儂はお前になんの嫌悪も抱いていない。きっと昔、儂がそういう生意気な若造だったからだ。」

Denken “Rihitā, omaewa hontoni namaikina wakazoda. Ken’io bakani shi, mokutekino tamenara jakushao ashigeni surukotomo itowanai. Totenmo homerareta-yona ningen dewan ai. Nanoni washiwa omaeni nanno ken’omo idaite-inai. Kitto mukashi, washiga soiu namaikina wakazo datta-karada.”

Denken “Richter, you truly are an insolent youngster. You mock authority and have no qualms about mistreating the weak in order to achieve your goals. Your behavior is hardly praiseworthy. And yet I feel no hatred for you at all, probably because I was once an insolent youngster too.”

デンケン「そんな儂が、今は宮廷魔法使いの地位にいる。」

Denken “Sonna washiga imawa kyutei-mahotsukaino chiini iru.”

Denken “And now, I’m an imperial mage.”

リヒター「…何が言いたい?」

Rihitā “…Naniga iitai?”

Richter “What are you trying to say?”

デンケン「そう悲観するなということだ。三年後のお前は、今よりずっと強くなっている。ラオフェン、帰るぞ。」

Denken “So hikan-surunato iukotoda. San-nengono omaewa imayori zutto tsuyoku natteiru. Raofen, kaeruzo.”

Denken “I’m telling you not to be so discouraged. Three years from now, you’ll be far stronger than you are today. Laufen, let’s go.”

ラオフェン「ごめんね。爺さん不器用なんだ。」

Raofen “Gomenne. Jiisan bukiyo nanda.”

Laufen “Sorry. The old man’s not good with people.”

リヒター「お前はデンケンのなんなんだよ…」

Rihitā “Omaewa Denkenno nan-nandayo…”

Richter “What’s your relationship with Denken, exactly?”

リヒター「老いぼれが… 結局、何も買ってかないのかよ。」

Rihitā “Oiborega… Kekkyoku nanimo katteka-nainokayo.”

Richter “Damn it, old man. He didn’t buy anything after all.”

リヒター「今日は厄日か何かなのか?」

Rihitā “Kyowa yakubika nanika nanoka?”

Richter “Is today my unlucky day or something?”

フリーレン「街の人たちに聞いて回ったんだけど。ここならどんなに壊れた杖でも修理できるんだよね。」

Furīren “Machino hito-tachini kiite mawattan-dakedo. Koko-nara donnani kowareta tsue-demo shuri dekirun-dayone.”

Frieren “I asked around town and was told this shop can fix any staff, no matter how broken.”

リヒター「…見せてみろ。」

Rihitā “…Misete-miro.”

Richter “Show me.”

リヒター「このバラバラの物体はなんだ?まさか杖なのか?こんなゴミを寄こされても困る。」

Rihitā “Kono bara-barano buttaiwa nanda? Masaka tsue nanoka? Konna gomio yokosaretemo komaru.”

Richter “What is this broken pile of scrapwood? Don’t tell me this is meant to be a staff. I’m not a trash disposal service, you know.”

フリーレン「ゴミじゃないよ。…たぶん。」

Furīren “Gomija naiyo. …Tabun.”

Frieren “It’s not trash. Probably.”

リヒター「少しは気分が��くなっていたが、お前のせいで最悪な気分に逆戻りだ。俺にだって仕事を選ぶ権利はある。この杖は諦めろ。」

Rihitā “Sukoshiwa kibunga yoku-natteitaga, omaeno seide saiakuna kibunni gyaku-modorida. Oreni-datte shigoto’o erabu kenriwa aru. Kono tsuewa akiramero.”

Richter “My mood was starting to improve, but because of you, I feel terrible again. I have the right to choose which jobs I work on. You should give up on this staff.”

フリーレン「そう。できないならいいや。」

Furīren “So. Dekinai-nara iiya.”

Frieren “I see. If you can’t do it, then never mind.”

リヒター「フリーレン。お前はほんとに癇(かん)に障る奴だ。俺がいつ、できないとまで言った?」

Rihitā “Furīren. Omaewa hontoni kanni sawaru yatsuda. Orega itsu dekinaito-made itta?”

Richter “Frieren, you really get on my nerves. When did I say I couldn’t do it?”

フリーレン「今日中にできそう?第三次試験には間に合わせたいから。」

Furīren “Kyojuni dekiso? Dai-sanji-shiken niwa mani awasetai-kara.”

Frieren “Can you finish today? I want it to be repaired in time for the third test.”

リヒター「無茶を言いやがって。」

Rihitā “Muchao iiyagatte.”

Richter “Don’t be ridiculous.”

リヒター「フリーレン。」

Rihitā “Furīren.”

Richter “Frieren.”

フリーレン「何?」

Furīren “Nani?”

Frieren “What?”

リヒター「ゴミだなんて言って悪かった。手入れの行き届いた、いい杖だ。さぞかし大事にされていたんだろう。」

Rihitā “Gomida nante itte warukatta. Teireno ikitodoita ii tsueda. Sazokashi daijini sarete itandaro.”

Richter “I’m sorry for calling it trash. It’s a good, well-maintained staff. Someone must’ve taken really good care of it.”

ーーーーー

シュタルク「フェルン。もう帰ろうぜ。」

Shutaruku “Ferun. Mo kaeroze.”

Stark “Fern, let’s head back already.”

フェルン「フリーレン様は私のことをまるでわかっていません。」

Ferun “Furīren-samawa watashino koto’o marude wakatte-imasen.”

Fern “Ms.Frieren doesn’t understand me at all.”

シュタルク「そんなの俺だってわかんねぇよ。」

Shutaruku “Sonnano oredatte wakan-neeyo.”

Stark “I don’t understand you either.”

シュタルク「やめてよぉ!!俺に当たらないで!!」

Shutaruku “Yameteyoo!! Oreni atara-naide!!”

Stark “Stop! Don’t take it out on me!”

シュタルク「…だからさ、わかろうとするのが大事だと思うんだよ。フリーレンは頑張っていると思うぜ。」

Shutaruku “…Dakarasa, wakaroto surunoga daiji dato omoundayo. Furīrenwa ganbatte-iruto omouze.”

Stark “What matters is that she tries to understand you. I think Frieren is doing her best.”

リヒター「ん?ああ、お前、フリーレンとこの。弟子…か?ん?違ったか?」

Rihitā “N? Aa, omae, Furīren tokono. Deshi…ka? N? Chigattaka?”

Richter “You’re Frieren’s kid. Her student, right? Am I wrong?”

シュタルク「ああ、いや、そうだよ。」

Shutaruku “Aa, iya, sodayo.”

Stark “No, that’s right.”

リヒター「ま、どっちでもいいが…二次試験が終わったばかりだっていうのに、今日はお前の師匠のおかげで散々だった。いっそのこと新調してくれた方が、こっちも儲かるってのにな。」

Rihitā “Ma, docchi-demo iiga… Niji-shikenga owatta-bakari datte iunoni, kyowa omaeno shishono okagede san-zan datta. Issono koto shincho shite kureta-hoga, kocchimo mokarutte-nonina.”

Richter “Either way, the second test only ended yesterday, but I had another terrible day because of your master. I would’ve made more profit if you’d just bought a new one.”

リヒター「大事にしろよ。」

Rihitā “Daijini shiroyo.”

Richter “Take good care of it.”

ーーーーー

フェルン「…私の杖。」

Ferun “…Watashino tsue.”

Fern “My staff.”

ハイター「フリーレンは、感情や感性に乏しい。それが原因で、困難や行き違いが起こることもあるでしょう。でも一つだけ、いいこともあります。その分だけきっと、フリーレンはあなたのために思い悩んでくれる。彼女以上の師はなかなかいませんよ。」

Haitā “Furīrenwa kanjoya kanseini toboshii. Sorega gen’inde konnan’ya ikichigaiga okoru-kotomo arudesho. Demo hitotsu-dake iikotomo arimasu. Sono bundake kitto Furīrenwa anatano tameni omoi-nayande kureru. Kanojo ijono shiwa nakanaka imasen’yo.”

Heiter “Frieren struggles to understand emotions. I’m sure it will cause difficulties and disagreements. But there is one good thing about it. Frieren will worry and care about you just as much. Few masters are better than her.”

フリーレン「ん…暗い…」

Furīren “N… Kurai…”

Frieren “It’s dark…”

ーーーーー

フェルン「あの、フリーレン様。昨日は…」

Ferun “Ano, Furīren-sama. Kinowa…”

Fern “Ms.Frieren, about yesterday…”

フリーレン「何?」

Furīren “Nani?”

Frieren “What?”

フェルン「いえ、やっぱり何でもありません。」

Ferun “Ie, yappari nandemo arimasen.”

Fern “Actually, never mind.”

フリーレン「そう。」

Furīren “So.”

Frieren “I see.”

ファルシュ「それでは、これより第三次試験を始めます。」

Farushu “Soredewa, koreyori dai-sanji-shiken’o hajimemasu.”

Falsch “The third test will now begin.”

ーーーーー

ゼーリエ「何故、私がここまで出向いたか、理由はわかるか?ゼンゼ。」

Zērie “Naze, watashiga kokomade demuitaka, riyuwa wakaruka? Zenze.”

Serie “Do you know why I came all the way here, Sense?”

ゼーリエ「だんまりか。都合が悪いときは、いつもそうだな。」

Zērie “Danmarika. Tsugoga warui Tokiwa itsumo sodana.”

Serie “Nothing to say, huh? You always remain silent in troublesome situations.”

ゼーリエ「第二次試験の��格者は12名。異例の合格者数だ。多すぎる。全員協力型の試験は大いに結構だ。今の一級魔法使いには協調性がないからな。」

Zērie “Dai-niji-shikenno gokakushawa ju-ni-mei. Ireino gokakusha-suda. Oosugiru. Zen’in kyoryoku-gatano shikenwa ooini kekkoda. Imano ikkyu-mahotsukai-niwa kyocho-seiga nai-karana.”

Serie “Twelve test-takers passed the second test. It’s an anomaly. It’s too many. I have no problem with a test that requires all participants to work together, as the current first-class mages lack cooperativeness.”

ファルシュ「面目ありません。」

Farushu “Menboku arimasen.”

Falsch “Forgive us.”

ゼーリエ「だがその中に、あってはならないほどの実力を持った者がいた。」

Zērie “Daga sono nakani, attewa naranai hodono jitsuryokuo motta-monoga ita.”

Serie “But there is one among the test-takers who is far too powerful.”

レルネン「…フリーレン様ですね。」

Rerunen “…Furīren-sama desune.”

Lernen “You mean Ms.Frieren.”

ゼーリエ「お陰で実力に見合わない者まで大勢合格した。従来通りの第三次試験では、そいつらは全員死ぬことになる。」

Zērie “Okagede jitsuryokuni miawanai monomade oozei gokaku shita. Jurai-doorino dai-sanji-shiken dewa, soitsurawa zen’in shinu kotoni naru.”

Serie “Because of her, many have passed despite lacking the requisite strength. A typical third test would kill all of them.”

ゼーリエ「ゼンゼ。それはお前の望みとは掛け離れたものだ。それに私とて、そこまでの無駄死には流石に望んでいない。」

Zērie “Zenze. Sorewa omaeno nozomi-towa kake-hanareta monoda. Soreni watashi-tote, sokomadeno mudajiniwa sasugani nozonde inai.”

Serie “Sense, that’s hardly what you want, and not even I wish to see such pointless deaths.”

ゼンゼ「ゼーリエ様…」

Zērie “Zērie-sama…”

Sense “Ms.Serie.”

ゼーリエ「謝る必要はない。すべてフリーレンが悪い。異例には異例を。第三次試験は私が担当する。平和的に選別してやる。従来の担当はお前だったな。異論はないな、レルネン。」

Zērie “Ayamaru hitsuyowa nai. Subete Furīrenga warui. Irei niwa ireio. Dai-sanji-shikenwa watashiga tanto-suru. Heiwa-tekini senbetsu shiteyaru. Juraino tantowa omae dattana. Ironwa naina, Rerunen.”

Serie “There’s no need to apologize. It’s all Frieren’s fault. An anomaly calls for an anomaly. I will proctor the third test. It will be a peaceful selection. In past years, you’ve proctored the test. You don’t object, do you, Lernen?”

レルネン「ゼーリエ様のわがままは、今に始まったことではありませんから。それに私はフリーレン様を試すような器ではありません。一目見てわかりました。彼女は魔力を制限しています。絶大な魔力です。ゼーリエ様に匹敵するほどの。」

Rerunen “Zērie-samano wagamamawa, Imani hajimatta kotodewa arimasen-kara. Soreni watashiwa Furīren-samao tamesu-yona utsuwa dewa arimasen. Hitome mite wakari-mashita. Kanojowa maryokuo seigen shite-imasu. Zetsudaina maryoku desu. Zērie-samani hitteki-suru-hodono.”

Lernen “Your willfulness is nothing new, Ms.Serie. Besides, I could not possibly test Ms.Frieren. I could tell at a glance that she’s suppressing her own mana. Her mana is tremendous, equal to yours.”

ゼーリエ「ファルシュ。気が付いたか?」

Zērie “Farushu. Kiga tsuitaka?”

Serie “Falsch, did you notice?”

ファルシュ「いえ、何の話だか… 彼女の魔力は試験会場で直接見ました。あの魔力は制限されたものとは思えません。制限特有の魔力の揺らぎもなかった。この揺らぎは、魔力を持った生物である限り、消せるものではありません。仮にそれが可能だったとしても、途方もない時間が必要でしょう。とても実用的な技術とは思えません。」

Farushu “Ie, nanno hanashi-daka… Kanojono maryokuwa shiken-kaijode chokusetsu mimashita. Ano maryokuwa seigen sareta-mono-towa omoe-masen. Seigen tokuyuno maryokuno yuragimo nakatta. Kono yuragiwa maryokuo motta seibutsude aru kagiri keseru-monodewa arimasen.”

Falsch “No, I have no idea what he’s talking about. I observed her mana myself at the testing area. It didn’t seem to me like she was suppressing it. I observed none of the typical fluctuations. No living creature with mana can conceal these fluctuations. Even if it were possible, it would take an extraordinary amount of time to master.”

ゼーリエ「その実用的でない技術にフリーレンは生涯を捧げた。魔族を欺くために。」

Zērie “Sono jitsuyo-tekide nai gijutsuni Furīrenwa shogaio sasageta. Mazokuo azamuku tameni.”

Serie “It would hardly be a practical skill. Frieren has devoted her life to mastering that impractical skill in order to deceive demons.”

ゼーリエ「魔族は私達人類よりも遥かに魔力に敏感だ。生まれ持った才覚でもなければ、百年や二百年制限したところで欺けるものじゃない。正に時間の無駄だ。その時間を別の鍛錬に使えば、何倍も強くなれる。非効率極まりない。」

Zērie “Mazokuwa Watashi-tachi jinrui yorimo harukani maryokuni binkanda. Umare-motta saikaku-demo nakereba, hyaku-nen’ya nihyaku-nen seigen shita tokorode azamukeru monoja nai. Masani jikanno mudada. Sono jikan’o betsuno tanrenni tsukaeba, nanbaimo tsuyoku nareru. Hi-koritsu kiwamari-nai.”

Serie “Demons are far more sensitive to mana than us humanoids. Without innate talent, it takes more than a century or two of practice to fool them. It truly is a waste of time. You’d become far more powerful devoting your efforts to training something else. It’s incredibly inefficient.”

ゼーリエ「だがその非効率が相手の隙を生み出すこともある。熟練の魔法使いの戦いにおいて、相手の魔力を見誤るというのは、死に直結しかねない。現にフリーレンは、歳の割には技術の甘い魔法使いだが、そうやって魔族を打ち倒してきた。それほどまでに、フリーレンの魔力制限は洗練されている。私の知る限り、それをたったひと目で見破ったのは魔王だけだ。今この瞬間まではな。レルネン。」

Zērie “Daga sono hikoritsuga aiteno sukio umidasu kotomo aru. Jukurenno mahotsukaino tatakaini oite, aiteno maryokuo miayamaruto iunowa, shini chokketsu shi-kanenai. Genni Furirenwa, toshino wariniwa gijutsuno amai mahotsukai daga, soyatte mazokuo uchitaosite kita. Sorehodo-madeni, Furīrenno maryoku-seigenwa senren sarete iru. Watashino shiru-kagiri, soreo tatta hitomede miyabutta-nowa Mao dakeda. Ima kono shunkan madewana. Rerunen.”

“But that inefficiency breeds weakness in others. In a battle between experienced mages, miscalculating your opponent’s mana can lead directly to death. Frieren is in fact relatively unskilled for her age, and yet she’s defeated demons. Her mana control is simply that refined. As far as I knew, only the Demon King was able to see through it at first glance. That is, until this moment, Lernen.”

レルネン「偶然です。偶然僅かな揺らぎが見えた。それだけです。」

Rerunen “Guzen desu. Guzen, wazukana yuragiga mieta. Soredake desu.”

Lernen “It was a coincidence. I just happened to see a minor fluctuation. That’s all.”

ゼーリエ「実に謙虚で堅実だ。お前が最初の一級魔法使いになってから半世紀が過ぎた。お前は臆病な坊やのままだな。それだけに残念でならん。これだけの境地に立っておきながら、老い先はもう短い。フリーレンと戦うことは、この先一生無いだろう。それがたとえ勝てる戦いであっても。」

Zērie “Jitsuni kenkyode kenjitsuda. Omaega saishono ikkyu-mahotsukaini nattekara han-seikiga sugita. Omaewa okubyona boyano mamadana. Soredakeni zannende naran. Koredakeno kyochini tatte-okinagara, oisakiwa mo mijikai. Furīrento tatakau-kotowa, konosaki Issho naidaro. Sorega tatoe kateru tatakaide attemo.”

Serie “Ever modest and dependable. It’s been more than half a century since you became the first first-class mage. But you’re still the same timid boy. That’s my only disappointment. You’ve achieved this level, and yet you don’t have much longer to live. I doubt you’ll ever get the chance to fight Frieren, even if it’s a battle you could win.”

ゼーリエ「やはり人間の弟子は取るものではないな。」

Zērie “Yahari ningenno deshiwa torumonodewa naina.”

Serie “I shouldn’t take on human students.”

ゼーリエ「本当に残念だ。」(結局あの子にも見えなかったか。私の魔力の“揺らぎ”が。)

Zērie “Hontoni zannenda.” (Kekkyoku anokonimo mienakattaka. Watashino maryokuno ‘yuragi’ga.)

Serie “It’s truly disappointing.” (In the end, that boy never saw the fluctuations in my mana either.)

ーーーーー

ファルシュ「第三次試験の内容は、大魔法使いゼーリエ様による面接です。準備出来次第、順番に呼ぶので、それまで別室で待機してください。」

Farushu “Dai-sanji-shikenno naiyowa, dai-mahotsukai Zērie-samani yoru mensetsu desu. Junbi deki shidai junbanni yobunode, soremade besshitsude taiki shite kudasai.”

Falsch “The third test will be an interview with Serie the Great Mage. You will be called one at a time when she is ready for you. Please wait here until then.”

フリーレン「そう来たか。ゼーリエは私とフェルンを受からせる気はないね。」

Furīren “So kitaka. Zēriewa watashito Ferun’o ukaraseru kiwa naine.”

Frieren “So that’s how it’s going to be. Serie intends to fail us both.”

フェルン「お知り合いなんですか?」

Ferun “Oshiriai nandesuka?”

Fern “You know her?”

フリーレン「昔のね。たぶん直感で合格者を選ぶつもりだろうね。でもゼーリエの直感は、いつも正しい。現に私は、未だにゼーリエが望むほどの魔法使いにはなれていない。」

Furīren “Mukashi-no-ne. Tabun chokkande gokakushao erabu tsumori-darone. Demo Zērieno chokkanwa itsumo tadashii. Genni watashiwa imadani Zēriega nozomu-hodono mahotsukai-niwa narete-inai.”

Frieren “From a long time ago. She probably intends to choose who passes based on her intuition. But Serie’s intuition is always right. I still haven’t become the mage Serie wishes I were.”

ーーーーー

カンネ「あの…」

Kanne “Ano…”

Kanne “Excuse me.”

ゼーリエ「不合格だ。帰れ。」

Zērie “Fugokakuda. Kaere.”

Serie “You fail. Now leave.”

カンネ「…理由を聞いてもいい?」

Zērie Kanne “May I ask why?”

ゼーリエ「今もお前は私の魔力に恐怖を感じている。自分の身の丈が、よくわかっているんだ。一級魔法使いになった自分の姿がイメージできないだろう。魔法の世界ではイメージできないものは実現できない。基礎の基礎だ。帰れ。」

Zērie “Imamo omaewa watashino maryokuni kyofuo kanjite-iru. Jibunno mino takega yoku wakatte-irunda. Ikkyu-mahotsukaini natta jibunno sugataga imēji dekinai daro. Mahono sekaidewa imēji dekinai monowa jitsugen dekinai. Kisono kisoda Kaere.”

Serie “My mana frightens you. You know the limits of your own abilities. You can’t imagine yourself as a first-class mage, can you? In the world of magic, that which can’t be visualized cannot be. It’s the most fundamental principle. Now leave.”

ゼーリエ「不合格。」

Zērie “Fugokaku.”

Serie “Fail.”

ゼーリエ「不合格。」

Zērie “Fugokaku.”

Serie “Fail.”

ゼーリエ「不合格。」

Zērie “Fugokaku.”

Serie “Fail.”

ゼーリエ「不合格だ。」

Zērie “Fugokakuda.”

Serie “Fail.”

ゼーリエ「フリーレン。お前も一級魔法使いになった自分の姿をイメージできていないな。だが他の受験者とは異なる理由だ。お前は私が合格を出すとは、微塵も思っていない。」

Zērie “Furīren. Omaemo ikkyu-mahotsukaini natta jibunno sugatao imēji dekite-inaina. Daga hokano jukensha-towa kotonaru riyuda. Omaewa watashiga gokakuo dasutowa mijinmo omotteinai.”

Serie “Frieren, you can’t imagine yourself as a first-class mage either, but for a different reason from the rest of the test-takers. You don’t believe I’d ever let you pass.”

フリーレン「事実でしょ。」

Furīren “Jijitsu desho.”

Frieren “It’s true, isn’t it?”

ゼーリエ「一度だけチャンスをやる。好きな魔法を言ってみろ。」

Zērie “Ichido dake chansuo yaru. Sukina maho’o itte-miro.”

Serie “I’ll give you one chance. Tell me your favorite spell.

フリーレン「花畑を出す魔法。」

Furīren “Hana-batakeo dasu maho.”

Frieren “A spell to create a field of flowers.”

ゼーリエ「フランメから教わった魔法か。実にくだらない。不合格だ。」

Zērie “Furanme kara osowatta mahoka. Jitsuni kudaranai. Fugokakuda.”

Serie “That’s the spell Flamme taught you. How truly useless. You fail.”

フリーレン「そう。」

Furīren “So.”

Frieren “Uh-huh.”

ゼーリエ「愚弄された���に、食い下がりすらしないのか。お前のような魔法使いが魔王を倒したとは、到底信じられん。」

Zērie “Guro sareta-noni, kui-sagari sura shinai-noka. Omaeno yona mahotsukaiga Mao’o taoshita-towa, totei shinji-raren.”

Serie “You won’t even stand your ground when I mock you? I find it hard to believe a mage like you defeated the Demong King.”

フリーレン「私一人の力じゃないよ。ヒンメル、アイゼン、ハイター、私、一人でも欠けていたら倒せなかった。」

Furīren “Watashi hitorino chikaraja naiyo. Hinmeru, Aizen, Haitā, watashi, hitori-demo kakete-itara taose-nakatta.”

Frieren “I didn’t do it alone. Himmel, Eisen, Heither, and me. If any one of us hadn’t been there, we couldn’t have won.”

ゼーリエ「仲間に恵まれたか。運が良かったな。」

Zērie “Nakamani megumaretaka. Unga yokattana.”

Serie “So you were blessed with strong allies. You were lucky.”

フリーレン「そうだよ。運が良かった。」

Furīren “Sodayo. Unga yokatta.”

Frieren “That’s right. I was lucky.”

ーーーーー

フリーレン「ねぇ、ヒンメル。どうして私を仲間にしたの?」

Furīren “Nee, Hinmeru. Doshite watashio nakamani shitano?”

Frieren “Himmel, why did you recruit me?”

ヒンメル「強い魔法使いを探していたからね。」

Hinmeru “Tsuyoi mahotsukaio sagashite-ita-karane.

Himmel “Because I was looking for a powerful mage.”

フリーレン「それなら王都にいくらでもいるでしょ。私じゃなくてもいい。」

Furīren “Sorenara Otoni ikura-demo irudesho. Watashija nakutemo ii.”

Frieren “There are plenty of powerful mages in the royal capital. It didn’t have to be me.”

ヒンメル「君がいいと思ったんだ。」

Hinmeru “Kimiga iito omottanda.”

Himmel “I wanted you.”

フリーレン「なんで?」

Furīren “Nande?”

Frieren “Why?”

ヒンメル「フリーレン。君は覚えていないだろうけれども、昔、僕は一度だけ君と会ったことがある。」

Hinmeru “Furīren. Kimiwa oboete-inai daro-keredomo, mukashi, bokuwa ichido-dake kimito atta kotoga aru.”

Himmel “Frieren, you may not remember, but I once met you a long time ago.”

フリーレン「うん。全然覚えていない。」

Furīren “Un. Zen-zen oboete-inai.”

Frieren “Yeah, I don’t remember that at all.”

ヒンメル「だろうね。子供の頃、森に薬草を取りに入ったとき道に迷った。長い間、夜の森をさまよって、人生で初めて孤独を味わった。もう二度と村に帰れないかと思ったよ。」

Hinmeru “Darone. Kodomono koro, morini yakuso’o torini haitta-toki michini mayotta. Nagai aida yoruno morio samayotte jinseide hajimete kodokuo ajiwatta. Mo nidoto murani kaerenai-kato omottayo.”

Himmel “I know you don’t. When I was a child, I got lost while gathering herbs in the forest. Wandering the woods for hours at night, I experienced loneliness for the first time in my life. I thought I’d never be able to return to my village.

ヒンメル「そのとき一人のエルフが人里の方向を教えてくれた。本当に方向を教えるだけで、励ましの言葉一つ口にしなかった。子供心に、なんて冷たい人だと思ったよ。」

Hinmeru “Sonotoki hitorino erufuga hitozatono hoko’o oshiete kureta. Hontoni hoko’o oshieru-dakede, hagemashino kotoba hitotsu kuchini shinakatta. Kodomo-gokoroni nante tsumetai hitodato omottayo.”

Himmel “That was when a lone elf pointed me in the direction of the village. All she did was show me which way it was. She spoke not a word of encouragement. To the eye of a child, she seemed so cold-hearted.”

ヒンメル「僕のそんな不安を感じ取ったのか、それともただの気まぐれだったのか、君は僕に花畑を出す魔法を見せてくれた。綺麗だと思ったんだ。生まれて初めて魔法が綺麗だと思った。」

Hinmeru “Bokuno sonna fuan’o kanji-tottanoka, soretomo Tadano kimagure-dattanoka, kimiwa bokuni hana-batakeo dasu maho’o misete kureta. Kireidato omottanda. Umarete hajimete mahoga kireidato omotta.”

Himmel “Perhaps she sensed my unease, or perhaps it was on a whim… You showed me a spell to create a field of flowers. I thought it was beautiful. For the first time in my life, I thought magic was beautiful.”

ーーーーー

フリーレン「きっとこれはただの偶然に過ぎないことだけれども、ヒンメル達と出会わせてくれたのは、師匠(せんせい)が教えてくれたくだらない魔法だよ。」

Furīren “Kitto korewa tadano guzenni suginai kotoda-keredomo, Hinmeru-tachito deawasete-kuretanowa, senseiga oshiete-kureta kudaranai maho dayo.”

Frieren “It’s probably just a coincidence, but it was that useless spell my master taught me that brought me and my companions together.”

フリーレン「それからゼーリエ。フェルンも同じように不合格にするつもりだろうけれども多分それはできないよ。あの子はゼーリエの想像を超えるよ。人間の時代がやってきたんだ。」

Furīren “Sorekara Zērie. Ferunmo onaji-yoni fugokakuni suru-tsumori-daro-keredomo tabun sorewa dekinaiyo. Ano kowa Zērieno sozo’o koeruyo. Ningenno jidaiga yatte-kitanda.”

Frieren “Also, Serie, I’m sure you intend to fail Fern as well, but I doubt you’ll be able to. She will exceed your expectations. The era of humans has arrived.”

ゼーリエ(何が想像を超えるだ。私の魔力を見て立ち竦んでいる。他の受験者となんら変わらん。)

Zērie (Naniga sozo’o koeruda. Watashino maryokuo mite tachi-sukunde-iru. Hokano jukenshato nanra kawaran.)

Serie (Exceed my expectations? Hardly. The sight of my mana has her frozen in place. She’s no different from the other test-takers.)

ゼーリエ「……待て。お前、何が見えている?」

Zērie “……Mate. Omae, naniga miete-iru?”

Serie “Wait. What do you see?”

フェルン「…揺らいでいる。」

Ferun “…Yuraide-iru.”

Fern “It’s fluctuating.”

ゼーリエ「…フェルンとか言ったな。お前、私の弟子になれ。」

Zērie “…Ferun toka ittana. Omae watashino deshini nare.”

Serie “Fern, was it? Be my student.”

フェルン「え、嫌です。」

Ferun “E, iya desu.”

Fern “What? No.”

(The end of comic vol.6 / コミックス6巻 完)

ーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーー

(The beginning of comic vol.7 / コミックス7巻 冒頭)

ゼーリエ「悪いようにはしない。私ならお前を、より高みへと連れていける。未だかつて魔法使いが辿り着いたことのないほどの高みへ。」

Zērie “Warui-yoniwa shinai. Watashi-nara omaeo yori takami-eto tsurete-ikeru. Imada-katsute mahotsukaiga tadori-tsuita kotono naihodono takamie.”

Serie “I’ll treat you well. I can take you to greater heights. To heights no other mage has ever reached.”

フェルン「それは合否と関係があるのですか。」

Ferun “Sorewa gohito kankeiga aruno-desuka.”

Fern “Does this affect whether or not I pass?”

ゼーリエ「あるかもしれない。」

Zērie “Arukamo shirenai.”

Serie “Perhaps.”

フェルン「そうですか。ゼーリエ様。」

Ferun “Sodesuka. Zērie-sama.”

Fern “I see. Ms.Serie.”

ーーーーー

フリーレン「フェルン。ゼーリエが色々と言ってくると思うけれども、要求を呑む必要はないよ。私がゼーリエに何を言っても不合格になるように、フェルンは何を言っても合格になる。だってゼーリエの直感はいつも正しいから。」

Furīren “Ferun. Zēriega iro-iroto itte-kuruto omou-keredomo, yokyuo nomu hitsuyowa naiyo. Watashiga Zērieni nanio ittemo fugokakuni naruyoni, Ferunwa nanio ittemo gokakuni naru. Datte Zērieno chokkanwa itsumo tadashii-kara.”

Frieren “Fern. I’m sure Serie will have a lot of things to say to you, but there’s no need for you to accept her demands. Just as Serie will fail me no matter what I say, she will pass you no matter what you say. After all, Serie’s intuition is always right.”

ーーーーー

フェルン「私はフリーレン様の弟子です。」

Ferun “Watashiwa Furīren-samano deshi desu.”

Fern “I am Ms.Frieren’s student.”

ゼーリエ「フリーレンの入れ知恵だな。…私は有望な魔法使いを見逃すほど馬鹿じゃない。」

Zērie “Furīrenno irejie dana. …Watashiwa yubona mahotsukaio minogasu-hodo bakaja nai.”

Serie “Frieren coached you, didn’t she? I’m not foolish enough to overlook a promising mage.”

ゼーリエ「合格だ。」

Zērie “Gokakuda.”

Serie “You pass.”

ゼーリエ「次。」

Zērie “Tsugi.”

Serie “Next.”

(Continue to Episode 28)

0 notes

Text

The Chanoyu Hyaku-shu [茶湯百首], Part I: Poem 18.

〽 San-puku no jiku wo kakeru ha naka wo kake jiku-saki wo kake tsugi ni jiku-moto

[三幅の軸を掛けるは中を掛け、 軸先を掛け次に軸本].

“When a set of three scrolls¹ will be hung [in the toko], the middle [scroll] is hung [first], [then] the scroll where the composition begins is hung, and next the scroll where the composition ends.”

During the Kamakura period, in the mansions of the military leaders², the preference seems to have been to display a set of three scrolls in the toko.

[The writing (in red) on the sketch reads, from the left, migi (右), right; hon-son (本尊), the revered principal (image); hidari [㔫 = 左], left.]

The earliest clear explanation of the meaning of this poem (of which I am aware) can be found in Sōami’s O-kazari ki [御飾記].

The underlined portion of the text that follows the sketch reads:

e no kake-yo no koto, dai-ichi chu-son wo kake, dai ni hidari, dai san ni migi wo to shirushi

[繪の掛様之事、第一中尊をかけ、第二㔫、第三に右をと記].

“Concerning the way to hang the paintings: first the chū-son is hung up; secondly, the [painting on the] left; and third, the [painting on the] right -- so it has been recorded....”

Chū-son [中尊] is the more widely accepted name for what the drawing calls the hon-son [本尊]. Both names refer honorifically to the principal image.

This means that first the middle painting (which is usually an image of the Buddha, or one of the Bodhisattvas or patriarchs -- in this example the Bodhisattva Kannon) is hung up first,

then (as is clearly marked on the sketch), the scroll to its left (which is the painting on the host’s right -- a landscape, in this case, of a misty mountain hamlet³) is hung up,

and finally the painting on the right (which is the scroll on the host’s left; in this triptych it is a painting of the sun setting behind a fishing village) is added, completing the set.

Because Jōō is following this same way of doing things, the term jiku-saki is associated with the right side of the toko (the side near the bokuseki-mado), while jiku-moto is associated with the left side (the side closest to the toko-bashira).

Later, exceptionally wide scrolls were displayed as well -- scrolls so wide that their kake-o [掛緒] (the cord, secured to the upper half-roller, by which the scroll was suspended from the hooks) was long enough to contact all three hooks. When scrolls of this sort were being hung up, first the kake-o would be slipped over the central hook. Then over the hook to its right (jiku-saki), and finally over the hook to its left (jiku-moto). And sets of three scrolls made by cutting a larger painting into sections were also hung up in the same way⁴.

And finally, with the appearance of wabi-no-chanoyu during the second half of the fifteenth century, bokuseki (which were long texts almost always written from right to left) came to be hung in the wabi setting; and these, too, were usually wide enough to be hung from three hooks.

Jiku-saki [軸先], thus, came to be associated with the side of a composition where the writing (or painting) began, which was also the side closest to the katte²; and jiku-moto [軸本, 軸元] meant the side where the composition ends (in other words, where the artist’s signature and name-seals were found) -- this side was also the side closest to the toko-bashira⁵.

The confusion over the meaning of jiku-saki and jiku-moto appears to date from a time when Sōami’s instructions came to be separated from his drawing. This may not be as outlandish as it at first sounds, because, even today, many editions reproducing the texts of works like Nōami’s Kun-dai kan sa-u chō ki [君臺觀左右帳記] and Sōami’s O-kazari ki [御飾記] not infrequently leave out some (or all) of the drawings. In this case, without Sōami’s notations on his representations of the scrolls, there would be no way for a reader to understand that “left” and “right” were being used relative to the chū-son, rather than to the scrolls when seen from the host’s perspective.

As an odd aside, while searching for an on-line version of the O-kazari ki, several of the search results linked to editions of the Tokugawa bakufu’s O-kazari sho [御飾書]⁶ (though they had been mislabeled by their sources as O-kazari ki). This is unnerving because the two texts are distinctly different things (even though the O-kazari sho was based on the O-kazari ki) -- with the latter work often deviating from the former in subtle ways.

And, as a completely relevant example, while the O-kazari sho includes a version of the same sketch (shown above), that sketch lacks any indication that the painting on the right is supposed to be considered to be the “left” painting, or that the painting to the left of the central image was actually considered to be the “right” painting; but neither does this book contain the text indicating the order in which the scrolls were to be hung up, suggesting that the teaching was either no longer considered to be important, or that it had been lost or forgotten.

To further confuse things, when a set of four portraits (hito-kata [人形]) were displayed at the same time, the rule was that they were hung up “in order” -- that is, starting with the painting on the right side of the series, and ending with that on the left (which is why the scrolls in the following sketch, from a different copy of the O-kazari sho, are numbered 1 [一], 2 [二], 3 [三], and 4 [四]).

Once the rule defining the relationships between the three scrolls of a triptych was forgotten, it was only logical that “left” would mean the scroll on the host’s left, and “right” would mean the one on his right.

This misunderstanding appears to be how jiku-saki came to refer to the side of the toko closest to the toko-bashira, in certain writings from the Edo period, and jiku-moto to the side closest to the bokuseki-mado⁷. Yet once this came to be the more or less generally accepted interpretation, it was still recognized that, in the case of horizontal hand-scrolls, jiku-moto would still refer to the side closest to the roller, while jiku-saki would refer to the opposite side, the side where the maki-o [巻緒] (the cord that is used to secure the scroll when it is rolled up) was attached. This idea, then, when applied to a bokuseki (many of which were hand-scrolls that were only mounted as kakemono from the late fifteenth century onward), meant that jiku-moto would be the side where the signature and seals were found, while the opposite side of the scroll, where the text began, would be jiku-saki. This is why it came to be said that the locations of jiku-saki and jiku-moto were reversed when a bokuseki was hung in the toko (bokuseki were originally only displayed in the wabi small room; thus, even during those periods when the tea world was arguing that jiku-saki referred to the part of the toko closest to the toko-bashira, things remained the way they always had been in the small room, since jiku-moto was always the side where the monk-author had signed his name at the end of his text).

All of this would be no more than a matter of semantics except for the fact that it impacts on the way objects were displayed in the toko when the host is following directions given to him by his school, such as where the flower arrangement should be located -- and this seems to be part of the reason why the chabana came to be placed toward the toko-bashira⁸.

The basic rule that should be observed, however (and irrespective of what the different divisions of the of the space within the toko are named), is that objects that are put in the toko for display throughout the za -- such as the chabana -- should be placed on the side of the toko closest to the bokuseki-mado (since they will not be accessed while the guests are seated in their places⁹). And objects that the host accesses during the gathering (while the guests are sitting in their seats) -- such as an incense burner, or bon-chaire¹⁰ -- should be placed on the side of the toko closest to the toko-bashira, because that side is always accessible, even when the shōkyaku is present in his usual seat. Keeping this rule in mind¹¹, the conventions calling on jiku-saki versus jiku-moto that have been articulated over the centuries should be interpreted appropriately -- because in some periods jiku-saki referred to the side closest to the toko-bashira, while in others it referred to the side closest to the bokuseki-mado.

During the Kamakura period, scrolls of the sort that are being considered here were almost always paintings – though specially made writings (that divided a text across two or more panels) became somewhat more common from the Edo period¹² (with some monks even creating multi-paneled calligraphic works specifically for this purpose).

Reviewing the several sources for this verse, we find two variants -- in addition to the more common version that was included in the Kyūshū manuscript. The Sen family’s variant that was quoted by Katagiri Sadamasa¹³ (shaded with yellow, since it differs only slightly from the others) simply replaces the word jiku [軸] (scroll) with the word e [繪] (meaning a painting). This is not really surprising¹⁴, because the scrolls that came in sets of three were (originally) almost always paintings -- whether sections cut from a single large painting¹⁵ (which were intended to be always displayed together, in order to recreate the original work¹⁶), or sets of three independent (but complementary) paintings¹⁷ that were associated with one another (either by the original artist, or collected together by one of the dōbō-shū [同朋衆]), and then mounted in the same way¹⁸ to be displayed together.

The other two sources are more extreme in their deviation -- though they actually appear to represent Jōō’s original version of this verse.

〽 san-puku no e wo kakuru¹⁹ ni ha naka wo kake, jiku-saki wo kake, tsugi ni jiku-waki

[三幅の繪を懸くるには中をかけ、 軸さきをかけ、次に軸わき].

“In the case where [a set of] three paintings will be hung up [at the same time], the middle is hung [first], the one on the far side is hung, and then the one on the [near] side.”

These versions (highlighted in blue) differ from the Kyūshū manuscript (and most of the other collections that date from the Edo period) in that (in addition to the substitution of the kanji e [繪] for jiku [軸]) they have jiku-waki [軸脇] rather than jiku-moto.[軸本]. Jiku-waki means “beside the jiku,” and refers to the side of the scroll closest to the toko-bashira (since, once the guests were in their places, this was the only side of the toko that could be accessed by the host²⁰.

_________________________

¹This poem is referring to the practice known as san-puku ittsui [三幅一對] -- the display of a set of three scrolls (that were created to be hung as a unit) in the toko at the same time.

One of the most famous triptychs to survive from the fifteenth century, mounted for Yoshimasa by the great dōbō [同朋] Nōami [能阿彌; 1397 ~ 1471], is shown above. These scrolls are now owned by the Nishi Hongan-ji [西本願寺], where they are displayed (on special occasions) in that temple’s shiro-shoin [白書院].

As this shoin reflects the style of the Kamakura period*, this photo gives us a good idea of the setting for which Nōami prepared these scrolls. San-puku tsui, therefore, is an echo of the kind of things that were done in the earliest days of chanoyu in Japan. ___________ *Shoin traditionally came in two varieties. The shiro-shoin [白書院] featured unpainted pillars and other woodwork; the kuro-shoin [黒書院], had these painted with black lacquer. The shiro-shoin was regarded as the more formal of the two venue, used for the reception of very important guests (of the highest rank); the kuro-shoin was used on more ordinary occasions.

²This refers to mansions constructed in the architectural style known as shoin-zukuri [書院造].

In contrast to the style favored by the court nobles (called shinden-zukuri [寝殿造]), where the nobleman sat on a more or less portable mi-chōdai [御帳臺] floored with a pair of tatami mats placed side-by-side to form a square (which was then enclosed by a wooden frame from which a cloth roof, curtains, and blinds were suspended, as shown below), upon which a third, square, mat was placed as the nobleman’s seat,

the military men preferred shoin-style rooms featuring a built-in jō-dan [上段] (surrounded by thick plastered walls on two or three of its sides (the built-in nature and thick walls making it much more defensible) along the far side, with blinds that could be lowered to obscure its occupant from the gaze of people seated in the larger room. Paintings and other art pieces were traditionally displayed in an alcove that usually stretched along the back wall of the jō-dan, and the large space meant that a single painting would not suffice.

³This san-puku tsui [三幅對] (triptych), painted by the Japanese monk-artist Sesshū Tōyō [雪舟等楊; c. 1420 ~ 1506], took its inspiration from similar paintings imported from the continent -- in addition to the central figure of the Bái-yī Guānyīn [白衣觀音] (white-robed* Kannon, or Avalokiteśvara†), the left and right compositions borrowed their subject matter from the Xiāo-Xiāng bā-jǐng [瀟湘八景]‡: the left painting is an adaptation of Shān-shì qíng-lán [山市晴嵐] (mists trailing over a mountain hamlet), while the right painting is based on Yú-cūn xī-zhào [漁村夕照] (a fishing village in the fading glow of the setting sun). ___________ *The white robe signifies a person without rank, and historically was used when representing a servant. Avlokiteśvara has taken on the task of assisting all sentient beings on their path toward enlightenment. This is an act of service of the highest order.

†In this case, the theme is Taki-mi byaku-i Kannon [瀧見白衣観音], which means the Bodhisattva Kannon seated in meditation, in contemplation of a waterfall.

‡The influence of this series of eight scenes on the aesthetics of Japan during the fifteenth century, and after, cannot be underestimated. The eight scenes, in their several permutations, defined the genres of landscape painting, and black-ink painting, for ever after.

⁴The same pattern was followed when opening folding screens, which traditionally had between four and eight panels (this may have actually been the original precedent for all of this, since folding screens were in use long before hanging scrolls came into fashion): first the middle section of the scroll was opened (this allowed the screen to stand upright without danger of falling over), the the right side was extended, and finally the left side was extended.

⁵And so the side of the toko opposite the toko-bashira. This is the side with the outer wall, in which the bokuseki-mado is frequently cut.

⁶The full name of this work is Higashiyama-dono no o-kazari sho [東山殿御飾書], but most libraries seem to catalog it simply as O-kazari sho [御飾書].

While it was based on Sōami’s O-kazari ki, there are a number of subtle changes. But what is most unfortunate is that many of the published collections of the classical tea documents (such as the Sadō ko-ten zen-shū [茶道古典全集]) include the O-kazari sho, rather than the O-kazari ki, based on the editorial assessment that this work, dating from the early Edo period, would somehow be more relevant to the present-day study of chanoyu than the original might be. In fact, this decision obfuscates matters significantly, because it appears that many of the changes were effected by the bakufu precisely in order to establish the precedent for the way they preferred to do things, rather than document the way they were done in the earlier period. This will be misleading to anyone who lacks access to the earlier works, and assumes (as generally seems to be the case*) that the O-kazari sho is a faithful replica of Sōami’s treatise. __________ *In the Sadō ko-ten zen-shū, for example, the O-kazari sho is printed in volume 2, immediately following the Kun-dai kan sa-u chō ki (and this certainly implies a relationship between the two). The Nampō Roku, meanwhile, occupies volume 4, and there is a generally historically-consistent chronology to the order in which the documents were printed in this collection. Yet many of the important details in the O-kazari sho date to the Edo period, not to the Kamakura.

⁷The words jiku-saki and jiku-moto are not infrequently confused, even by Japanese chajin. The easiest way to remember them is to think that jiku-saki is like a branch of a tree, while jiku-moto is its root. The root is the person who created the painting or writing, so jiku-moto refers to the side where that person’s name and seals are found.

Originally, the orientation of the tokonoma was supposed to reflect the format of the meibutsu scroll that the host owned* -- indeed, during the first half of the sixteenth century it was considered inappropriate to add a toko onto the host’s tea room if he did not own a meibutsu scroll (the toko, in other words, was there to do honor to the scroll -- meibutsu scrolls being those that had previously been part of the Higashiyama collection, and this was the reason why they were being treated as if they were noble, by being displayed above a jō-dan [上段]). The side of the scroll that bore the name and seals of the artist was supposed to be located closest to the toko-bashira, because at night an oil-lamp was suspended from the hook nailed into the toko-bashira†, with its light oriented so as to illuminate the signature and seals.

Meibutsu scrolls that had the name and seals on the left side of the hon-shi [本紙], or in the middle near its lower edge, were supposed to be hung in a tokonoma that had the toko-bashira on the left (since scrolls of this sort are most common, this kind of tokonoma was called the hon-toko [本床], and because this kind of toko was located on the right side of the guests, it was also known as a kami-za toko [上座床]).

When a meibutsu scroll had the artist’s signature (or just a name-seal) on the right side of the hon-shi‡, it was supposed, when hung up by itself, to be displayed in a toko where the toko-bashira was on the right side (so the oil-lamp would, again, be on the side closest to the name). Since the toko-bashira should be located in the middle of one side of the room**, this meant that such a toko would have been erected on the guests’ left side; and this kind of tokonoma was therefore referred to as a ge-za toko [下座床]. ___________ *During the early sixteenth century, it was rare for a host to own even one meibutsu scroll. So when he managed to acquire one, he indicated this to his guests by attaching a tokonoma to his tea room, with the orientation of the toko reflecting the way the scroll itself was formatted, as explained above.

Hosts who did not own a meibutsu scroll were supposed to hang their (ordinary) scrolls directly on one wall of their tea room, usually with a Korean-style dining table (shaped like a shallow wooden box, with the legs folding up into the box for storage, as seen below) placed on the mat in front of the scroll.

When used for this purpose the table formed a low platform (2-sun or so high), the purpose of which was to keep the guests from getting too close to the scroll, so they would not inadvertently hit it, causing it to sway. The table used in this way was referred to as an oshi-ita [押し板].

†While originally this hook was nailed into the toko-bashira each time a lamp was needed, and then removed after the gathering was concluded, by the Edo period the practice of leaving it as it was began to gain favor. But as this became more common, the actual purpose for the hook was being forgotten, and people began using it to hang up their kake-hanaire (rather than nailing an additional hook to the minor pillar on the opposite side of the toko, as had been done in Jōō’s and Rikyū’s day). The result was that while the original idea had been for the flowers to arch toward the temae-za (as if leaning into the room from the garden outside), they now were oriented away from it -- a sort of representative hallmark of the Edo period’s approach to chanoyu.

‡Most frequently, these were paintings that had originally been the right-most of a set of several paintings -- during the sixteenth century, when the Ashikaga shōgunate was in decline, they began to sell off their treasures (mostly to the machi-shū of Sakai, Kyōto and Ōsaka, since that is where the day’s wealth had accumulated) in order to maintain the external trappings of government, and it was at this time that some of the sets of multiple scrolls were broken up -- either because the agents felt they could get more money for them individually, or because one or more scrolls of the original set had been lost or damaged.

Much less common were works that had originally been executed in that way (and these were, more often than not, paintings that had been created as part of a series that were intended to be displayed together, often as panels of a folding screen).

**At least in theory, the toko-bashira was supposed to be one of the pillars that supported the ridgepole of the roof. Thus it would have been located at, or near, the center line of the structure.

⁸The other reason is that placing it toward the toko-bashira also agreed with the idea that a kake-hanaire should be suspended on the hook that was nailed into the toko-bashira.

⁹Modern people sometimes argue that placing the chabana on that side -- especially when it is resting on the floor, means that, once the shōkyaku has taken his seat, his body will block the arrangement from the view of the other guests. While this is true, especially in the small room, it should be remembered that the chakai was called for the shōkyaku, and so everything was arranged for his delectation. If something like the flower arrangement would be difficult for the other guests to see once he had taken his seat, this was not an important consideration in Rikyū’s period*.

Furthermore, the chabana would only be so far off center if it were being displayed together with a long kakemono (since the original rule† was that the arrangement should not obscure any part of the scroll). When it is placed in the toko by itself, during the goza, it will be only slightly off center (albeit displaced toward the katte-side of the toko), and should be visible to the other guests even when the shōkyaku is sitting in front of the right side of the mouth of the toko‡. ___________ *And of course the shōkyaku would not sit there like a lump on a log, forcing the others to contort their necks in order to see what the host had arranged. Even someone like Hideyoshi would have discretely moved aside so that the others could inspect the toko. This is common sense.

†This rule, too, seems to have been ignored by the people who produced the O-kazari-sho -- since some of the sketches actually show flower arrangements obscuring parts of one scroll, when it is arranged in front of a diptych.

†This is another reason why the chabana should arch toward the temae-za.

¹⁰In the case of chanoyu, an incense burner is lifted into the toko after the guests have finished appreciating incense (mon-kō [聞香]) following the sumi-temae at the beginning of the shoza. A bon-chaire or utensils of that sort would be displayed in the toko during the shoza, and then moved to the utensil mat during the naka-dachi. But after the service of tea had been concluded, a meibutsu-chaire* could be lifted back into the toko, where it would remain until the guests left the room. Because these things are moved into the toko while the guests are still in their ordinary seats, such objects must take their seats on the side of the toko closest to the toko-bashira†. __________ *Which most bon-chaire today are not.

†Which contradicts the rule, if the rule says that it should be displayed “jiku-saki.”

¹¹Today most modern schools would tend to agree with the definition given in the Genshoku sadō daijiten [原色茶道大辞典]*:

kakemono no jō-seki no kata wo jiku-moto, chū-ō wo jiku-mae, katte no kata wo jiku-saki to iu

[掛物の上席の方を軸本、中央を軸前、勝手の方を軸先という].

“The side of the kakemono [closest to] the seat of honor is [called] jiku-moto; [the space] in front of it is [called] jiku-mae; and the side [toward] the katte is said to be jiku-saki.” __________ *Iguchi Kaisen [井口海仙; 1900 ~ 1982], et al.; Tankōsha, 1975 (ISBN4-473-00089-3 C0570 P15450E).

¹²Usually these were calligraphic renderings of classical Chinese texts (both poems and prose) written on a series of panels with the intention that they be mounted together on a folding screen (as seen below) -- a genre that was popular in Korea, and which appears to have been introduced into Japan during the early Edo period (along with many other aspects of Korean traditional culture and political philosophy).

Earlier Japanese folding screens usually featured a series of paintings of the four seasons (or representative seasonal flowers such as the orchid, bamboo, chrysanthemum, and plum-blossoms), sometimes with poetic colophons on each of the panels.

Such paintings were more easily separated from the set and mounted as individual scrolls.

¹³According to Sekishū, this version was supposed to have been copied from a Rikyū manuscript that was in the possession of one of the Sen families, but which apparently was lost (since the version of the poem found in the several Sen family archives seems to agree with the Kyūshū manuscript).

¹⁴In fact, since these poems were generally written down from memory each time a new copy was needed for presentation to another disciple, the inadvertent substitution of jiku [軸] for e [繪] is the kind of thing we might almost expect (given the repetition of jiku several times later in the shimo-no-ku).

¹⁵Almost always for conservation purposes, because it is much easier to protect narrower scrolls from damage than it is if a single scroll is extremely wide.

¹⁶Which only made sense, since at least some of the parts would probably have been meaningless without the rest of the composition to provide them context.

¹⁷Often these were painted, as a set, by the same artist, again with the intention that they would always be displayed together as a triptych. The earliest of these were religious works, with the central image being a portrait of the Buddha, while the ones on the left and right were paintings of his attendants, as mentioned above.

¹⁸While three scrolls with three different mountings can never be used in this way, sometimes the left and right scrolls feature identical mountings, while the central scroll is different -- albeit complementary, and of the same length as the other two. Regardless, such triptychs were generally kept in a single box with three compartments -- with their maki-o [巻緒] (wrapping cords -- the cord used to keep the scroll rolled while in storage) tied in different ways to indicate which position they were to occupy when hung up in the tokonoma (even if they had been placed in the wrong compartment).

See the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 7 (34c): the Display of the Gedai [外題] in the Toko (Part 3) for further details on the ways the cords were tied.

The URL for that post is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/696673666295021568/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-7-34c-the-display-of-the

¹⁹Kakuru [懸くる] is an archaic form of kakeru [懸ける].

²⁰In Jōō’s earliest version of his chakai, he imitated the Shino family by including the appreciation of incense during the shoza; and after the guests were done, the incense burner, placed on a tray (or, later, on a round board the same size as the tray), was lifted into the toko (so it would continue to perfume the air until the piece of kyara was exhausted).