#second nagorno-karabakh war

Text

System of a Down - B.Y.O.B.

2005

Mezmerize is the fourth studio album by the Armenian-American heavy metal band System of a Down. The album sold over 450,000 copies in its first week, and immediately topped the Billboard 200.

The band went on hiatus in 2006 and reunited in 2010. Other than two new songs in 2020 in response to the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War ("Protect the Land" and "Genocidal Humanoidz"), System of a Down has not released a full-length record since the Mezmerize and Hypnotize albums in 2005.

"B.Y.O.B." ("Bring Your Own Bombs") was released as the lead single from Mezmerize. It was written in protest against the Iraq War, and questions the integrity of military recruiting in America. The song reached number 27 on the US Billboard Hot 100, the band's highest peak to date on the chart.

"B.Y.O.B." won a Grammy Award in 2006 for Best Hard Rock Performance.

"B.Y.O.B." received a total of 66,3% yes votes!

youtube

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Only 3 months after completing the long-planned ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh) by forcing out Armenians, the indigenous population with a history of over 3000 years and, thus, having successfully carried out yet another step of turk-azeri multi-stage strategy of the (second!) genocide of Armenians...And yet, rather than be held accountable for the above-mentioned, azerbaijan recently won the bid to host the United Nation's climate summit next year.

REWARDED 3 months after carrying out an ethnic cleansing! It's funny how the world is so selective about which war crimes must be reprimanded and which ones— rewarded.

#un.. you've done it again my friend#at this point the only thing one can do is just laugh at this tomfoolery#armenia#artsakh#armenian genocide#history

642 notes

·

View notes

Text

Officials from the UK Foreign Office and the business department held an online meeting with British business leaders in November to encourage companies to take advantage of the “great opportunity” to support Azerbaijan president Ilham Aliyev’s rebuilding agenda.[...]

In the days after Baku’s military operations the UK government publicly condemned the Aliyev regime’s “unacceptable use of force” in Nagorno-Karabakh and warned that it had “put at risk efforts to find a lasting peaceful settlement” in the region.

But a recording of the online meeting, shared with the Guardian by campaigners at Global Witness, includes one senior UK government official encouraging business leaders to take advantage of the financial opportunities in the “huge western chunk of the country that needs to be rebuilt from the ground up”.

“The Azerbaijan government is supporting what it calls ‘the great return’, which is essentially providing the opportunity for the 700,000 [internally displaced people], these refugees, to basically return to Karabakh. So you have this great opportunity here actually,” the official said.

It is not clear whether the official was referring to Nagorno-Karabakh specifically, part of the far larger Karabakh region. Aliyev set out plans in 2020 to rebuild the “liberated districts” of the Karabakh region in western Azerbaijan, which includes Nagorno-Karabakh. The president said it was important that all displaced Azerbaijan citizens return to Nagorno-Karabakh and adjacent districts where they used to live.

A second government official told business leaders: “[There’s] a great opportunity here actually. [It was] just an empty land that was ready to be built over from scratch.”

Jonathan Noronha-Gant, a senior campaigner at Global Witness, said: “Behind closed doors, the UK government is calling Azerbaijan’s ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh a ‘great opportunity’. What century are these officials living in? It’s not a great opportunity for the UK, nor for the people who were displaced.”

In the recording the first official said UK companies were “well-placed” to collaborate with the Azerbaijan government to provide infrastructure advice to “a government which has financial means given that it has very large energy resources”. Azerbaijan owns one of the world’s largest gasfields, Shah Deniz in the Caspian Sea, and is a growing exporter of gas to Europe.[...]

A UK government spokesperson said: “These comments from UK officials have been misrepresented. Discussions of reconstruction referred to the UK government’s public work to assist with possible future development in the new towns being built for those displaced by decades of conflict.

“The UK is not involved in commercial activity or reconstruction efforts in the area of Nagorno-Karabakh region recovered by Azerbaijan through its September 2023 military operation.[...]

The Guardian revealed last year that Azerbaijan’s share of two large oil and gas projects operated by British oil company BP had earned its government almost $35bn (£28.6bn), or more than four times its military spending since 2020 when war broke out in the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh.[...]

BP also plans to build a 240MW solar farm in Azerbaijan’s “liberated lands”, according to Azerbaijan’s deputy energy minister. The Azerbaijani prime minister, Ali Asadov, met with the BP head of production, Gordon Birrell, recently to discuss the Sunrise solar project, which is planned for an area near the ghost city of Jabrayil, which was left in ruin after the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war.

22 Feb 24

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

Q: Have you ever wrote a poem, drew a painting, or recorded a song that almost (or has) brought you to tears any time you listen to it, read it, or see it?

“One in eight civilians killed or injured by landmines and unexploded ordnances is a child,” Save the Children (2023)

I’m not Armenian but I lived in the country as a Peace Corps volunteer and have been following the fighting in the Nagorno-Karabakh area, between Armenia and Azerbaijan, for years.

During those decades of war the Artsakh countryside - the hills and fields and mountains - have been littered with tens of thousands of landmines. According to NATO ACT’s current estimates, there are approximately 110 million live-ordnances still buried across nearly 70 countries worldwide. For reasons too complex to go into here the job of bomb disposal on the Armenian side fell to a group of volunteers, primarily teenage high school girls, who’d go out into the hills in their protective gear on the weekends and attempt to defuse any device that they could find.

The interviewer I heard this story from made it very clear this team was not trained by the military, they were primarily high schoolers who were, “learning as they went along,” doing this job because no one else would and there were fatalities among the volunteers.

I wrote this poem in 2007, 17-years before the Republic of Artsakh fell. My high school years were tumultuous but nothing like that. The horror that we make children shoulder. Now Artsakh is gone and the Armenian population has fled and I will never learn those volunteers’ names or their fates.

I titled the poem, "Trav'lin' Light," after a Billie Holiday song I use to croon. “No one to see/ I'm free as the breeze/ No one but me/ And my memories/ Some lucky night/ He may come back again/ So until then/ I'm travellin' light.” Bittersweet. as all love is, but dark. Dark and horrific. I’ve read this poem only once in public, at a Protest for Peace rally we were putting on in response to Iraq and the Surge. I got to the line, “stumbled on four,” and lost it. It’s a one-time only poem. I will never read it again.

Travel. Sudden lightning flash in daylight.

A word others use. "So from today I'm

trav'lin' light." As in atoms. The white

flash of a device going off. My grime

and bits settling down on your surprised

face. You. Someone had to plant these ghastly

boxes under this hill's skin. You surmised

there are hundreds. Children have already

stumbled on four. We. Travel with me here.

I want you here when I mess up. Just once.

Wave your hands. Call out my name. You can hear

the light. Count the seconds. The short distance

it takes to get to you. A blur. Crayon

red. I rise up and all at once — I'm gone.

#Artsakh#sonnet#quote unquote#poetry#poem#conversations with imaginary sisters#spilled ink#armenia#stop the genocide#trav'lin' light

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Authoritarian states’ traditional approach to conflict outside their borders is to choose sides—supplying political-diplomatic support and military muscle to their allies—or to freeze the conflict while keeping a hand in to stir the pot and shape possible outcomes. Russia has done both: the first by backing Syria’s Bashar al Assad against various rebel movements, and the second by trying to dominate the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Authoritarians are not known for expending resources on peacemaking ventures with uncertain outcomes. Nor do they focus on good governance norms after a settlement. They are often content to consolidate the power and standing of local authoritarians.

Yet that pattern seems to be shifting. Today, we are witnessing a number of authoritarian or semi-authoritarian states engage in mediation, and conflict management. China has mediated between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Qatar has led talks between Israel and Hamas, and Turkey has done the same between Russia and Ukraine leading to the Black Sea Grain deal that lapsed last year.

In an attempt at heavy-handed conflict management, Russia tried to freeze the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and sent in peacekeepers in 2020 but stood aside when the Azerbaijani forces took decisive action to seize the disputed territory three years later. Such activities are pursued by a wide range of nominal and quasi-democracies, military governments, presidential one-party states, and monarchies.

The impact of this surge in authoritarian peacemaking gets less attention than it deserves. Authoritarian states are buffeting the peacemaking diplomacy of Western states, blocking or undercutting Western initiatives and challenging Western leadership of the global peacemaking agenda. The most obvious impact has been the global polarization that creates gridlock in the U.N. Security Council, undercuts support for U.N. peace operations and saps coherence around critical norms such as human rights and individual freedoms.

This pattern constrains what the U.N. can do in conflict management, mediation and peacebuilding. It also directly challenges the ability of NGOs to work for dialogue and reconciliation in fragile and war-torn places such as Georgia where pro-Russian parties are imposing Russian-style controls on the activity of NGOs that receive external support. Such action undermines the unofficial playbook for peacemaking and good governance.

By pushing back against Western conceptions about managing conflict, authoritarian peacemaking is part-and-parcel of a more general global backlash against intrusive and interventionist western policies that may undercut the perceived authority and legitimacy of incumbent regimes.

This backlash privileges state sovereignty against notions about “global” norms relating to rights and governance. Sadly, the U.S. government has made the undermining of international norms easier by adopting double standards on civilian protection and human rights law in Ukraine and Gaza. Such conduct actually helps China attack American soft power in Africa and undercuts U.S. diplomatic efforts at the U.N.

But the authoritarian surge is not necessarily either effective or coherent. Consider, for example, the difficulty experienced by Egypt’s military regime and Qatar’s monarchy in bringing Hamas and Israel to a deal, even with strong backing from the U.S. and other Western and Arab states. Regional authoritarians have not been notably successful in bringing about peace and stability in Libya and have aggravated rather than alleviated its internal clan and tribal factionalism.

They have failed to cohere effectively for peace in Yemen. Regional authoritarians made Syria’s tragic civil war divisions worse before ceding the field to the Russians. In all these cases, the authoritarians ran into the hard realities of intractable conflicts where the local parties have plenty of weapons and have not yet exhausted their unilateral options. In some cases, they made the problem worse.

At first glance, it might appear that authoritarian states bring certain advantages to the table. One attribute is internal unity of command and policy coherence at the level of the individual state. Unlike liberal states, they can potentially bring not only a whole of government approach but also a whole of society focus in their strategy for dealing with conflicts. Messy internal policy debates do not bother them. Authoritarians generally place top priority on achieving stability and creating a favorable context for advancing regime interests, and their policies are best understood as transactional.

In practice the record of their approaches is quite mixed. In one model, for the transactions to succeed, it is necessary for the existing regime or the “winner” in a civil war to be capable of being a reliable partner to the external authoritarian conflict manager. In a second model, the authoritarian goal is to back a factional side—either to exploit natural resources or block an adversary or rival state, or perhaps both.

The idea of a negotiated settlement may not be a priority or be viewed as less desirable than some degree of continued instability. This scenario can slide into a third model in which rival authoritarians seek to impose a favorable outcome on the country and compete with rival external powers through the provision of military and political support. While authoritarian states may have internal coherence, they are often in conflict with other states.

It is not clear that any of these models is good for peace or for the lives of ordinary civilians. In the case of Syria, Russia prevailed by applying the first model, carpet-bombing cities to help the local authoritarian prevail, imposing a very cold peace. But it is not clear that authoritarian states will be successful in imposing outright victories in many other situations.

The case of Libya provides a vivid illustration of what can happen with the second model when outsiders pile in to pursue their varied agendas: In this case Egypt, Russia, the UAE, and the Saudis (to say nothing of the French) decided to support Gen. Khalifa Haftar’s designs against the U.N.-recognized unity government in Tripoli, backed by Turkey, Qatar, Italy, and the United States.

Commercial, strategic, and ideological agendas coursed across the strife-torn land, leading a succession of U.N. special envoys to resign in frustration, blaming the Libyan factions (rather than their backers) for a lack of political will to work for reconciliation and create conditions for holding elections. Libya’s disorder does not remain in Libya, as the neighboring Sudanese can attest.

In the case of the Ethiopia-Tigray civil war in 2020 to 2022, the Ethiopians enjoyed military support from the authoritarian regime of Eritrea as well as Turkey, Iran, and the UAE. But it was the African Union-based mediation of former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo supported by former Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta and senior envoys of the U.S. and South African governments negotiated an end to the fighting. This followed the Ethiopian government’s ability to impose itself militarily on Tigray at a key moment in 2022 thanks to Turkish drones—though the country is still facing insurgents in other regions.

But it is clear that Sudan is not endowed with such resources for conflict management, despite the high hopes generated by the internationally celebrated Juba Accord of October 2020 between its transitional government and a range of rebel movements. Two and a half years later, the current civil war erupted, causing the gravest humanitarian crisis in the world, affecting some 6.6 million internally displaced persons and 2 million refugees fleeing into neighboring countries.

Rival military factions are tearing the country apart while attracting external authoritarians like flies to flypaper. The Saudis and the United States continue to host peace efforts, but Sudan’s military leaders enjoy widespread backing from authoritarian states: The regime’s forces are aided by Egypt, the Saudis, and Iran while the rival Rapid Support Forces are allied with Libya’s Haftar, the Chad regime of Mahamat Deby, plus the Russians, the UAE, and an assortment of allies in neighboring states. This is the second model with a vengeance, and it looks increasingly like it is sliding into the third model of authoritarian rivals pushing their proxies to the finish.

Spectacles like these do not seem to augur well for the peacemaking business. They undercut the potential for international organizations to play their traditional role. The Security Council regularly takes up the Sudan file but is prevented by gridlock from naming names and using serious pressure to stop the fighting. The UAE strenuously denies its role in fueling the fighting in an unholy alliance including Haftar and Deby, and the western permanent members of the Security Council are well aware they cannot ignore likely vetoes from China and Russia.

At the regional level, African Union members are divided, and the Gulf Cooperation Council is hampered by the intense feuding between the Saudis and the UAE. Sudan is a laboratory case of how warring factions export their divisions to external sponsors who return the favor by exporting their own divisions back into the conflict.

At first glance, all of this may look bad for the United States and, more generally, the West because it points to the erosion of the West’s hard and soft power. High-minded efforts at conflict management and good governance contend face-to-face with the most cynical practitioners of transactional statecraft. However, U.S. diplomats need a closer look at peacemaking cases to understand how U.S. statecraft can sometimes be effective in corralling recalcitrant antagonists, operating behind the scenes or employing more of an invisible hand.

When necessary, the United States is capable of standing back and advancing its interests by empowering others, sharing credit, and borrowing leverage and even credibility from other players, including the transactional authoritarians, however unprincipled they are.

During the Balkan wars of the 1990s, it fell to the U.S. government to knock mostly authoritarian heads and impose a stop to the fighting. Representatives of the U.K., France, Germany, Italy, Russia, and the European Union attended the Dayton peace conference. In the case of Colombia’s long civil conflicts, Washington first deployed diplomatic leadership via Plan Colombia and helped shape the balance of power between the government and the Marxist rebels of the FARC.

In the next phase, the U.S. government operated more indirectly via a special envoy who participated discreetly in a process led by Cuba and Norway with facilitator countries Venezuela and Chile, all loosely coordinating with major European and neighboring states, the U.N., and the E.U., leading to the 2016 Colombian peace accords. Washington played its hand decisively but less visibly in the Northern Ireland process leading to the 1998 Good Friday agreement.

This less direct public face of peacemaking has a history. In 1905, Theodore Roosevelt indirectly maneuvered Tsarist Russia and imperial Japan to terminate a hugely costly war, leaving the visible negotiation to the direct parties. He never personally visited the conference table in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, but actively communicated with relevant governments and, in effect, borrowed leverage from authoritarian and democratic states alike, while blocking alternative approaches. The process required Roosevelt to navigate the politics of two authoritarian regimes which could not admit their need for his help.

Fast forward to the 1980s and 1990s when U.S. negotiators borrowed leverage from allies and erstwhile adversaries in bringing authoritarian regimes to make peace in Southern Africa (working with the British, Portuguese, and other Western allies as well as the Soviets, Cubans, Zambians, Congolese, Cape Verdeans, Mozambicans and the U.N. Secretariat), and to avert civil war in Ethiopia (working with Sweden, Britain, the Soviets, Israel, Sudan, and the Marxist-oriented rebel Eritrean and Tigrayan movements).

This is not a brand-new way of operating but one that could become more common in an age of multiple overlapping alignments where other states are partners on some issues and troublesome obstacles on others. It could also be less of a drain on the political capital available to presidents and secretaries of state. To work, it requires top level officials to delegate and a willingness to work closely with friends, partners, and other parties they wouldn’t want to bring home for dinner.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

“This is not an all-out war but a decentralized one with seemingly unconnected fronts that span across continents. It is fought in a hybrid style, meaning both with tanks and planes and with disinformation campaigns, political interference, and cyberwarfare. The strategy blurs the lines between war and peace and combatants and civilians. It puts a lot of extra fog in the "fog of war."

China, Russia, and Iran disagree on many things, but they all have the same goal: ridding their regions of U.S. influence and creating a multipolar global governance system and Tehran, Beijing, and Moscow know that U.S. political and military might is the only force preventing them from imposing their will on their neighbors.

(…)

When it comes to this war, the United States is asleep at the wheel. U.S. strategy has been about preparation for a large conventional war, containment, and weak deterrence. Washington has been pitifully absent in the irregular warfare field. There are almost no punishments or accountability—besides ineffective sanctions—for the nations that attack us.

(…)

Should the Biden administration continue its ineffective course, these countries will only be emboldened. Should support for Israel or Ukraine fail, China will be more likely to invade Taiwan. Deterrence is a great strategy but only works when the other side believes you will carry out your threats. You must establish that understanding by holding your enemies accountable for moves they take against you.

(…)

The Biden administration's support for Ukraine has been a rare show of force that has sent a strong message to the world. But it isn't enough. The U.S. foreign policy establishment must recognize the hybrid war being waged against it and show up on the irregular field of battle. Like it or not, the United States is the guarantor of stability in the world. By retreating from its responsibilities, the only thing Washington is guaranteeing is dark times ahead.”

“The list encompasses not just the wars in Gaza and Ukraine, but hostilities between Armenia and Azerbaijan in Nagorno-Karabakh, Serbian military measures against Kosovo, fighting in Eastern Congo, complete turmoil in Sudan since April, and a fragile cease-fire in Tigray that Ethiopia seems poised to break at any time. Syria and Yemen have not exactly been quiet during this period, and gangs and cartels continuously menace governments, including those in Haiti and Mexico. All of this comes on top of the prospect of a major war breaking out in East Asia, such as by China invading the island of Taiwan.

The Uppsala Conflict Data Program, which has been tracking wars globally since 1945, identified 2022 and 2023 as the most conflictual years in the world since the end of the Cold War. Back in January 2023, before many of the above conflicts erupted, United Nations Deputy Secretary-General Amina J. Mohammed sounded the alarm, noting that peace “is now under grave threat” across the globe. The seeming cascade of conflict gives rise to one obvious question: Why?

(…)

The first explanation holds that the cascade is in the eye of the beholder. People are too easily “fooled by randomness,” the essayist and statistician Nassim Nicholas Taleb admonished in his 2001 book of the same title, seeking intentional explanations for what may be coincidence. The flurry of armed confrontations could be just such a phenomenon, concealing no deeper meaning: Some of the frozen conflicts, for instance, were due for flare-ups or had gone quiet only recently. Today’s volume of wars, in other words, should be viewed as little more than a series of unfortunate events that could recur or worsen at any time.

(…)

Although coincidences certainly do occur, the current onslaught happens to be taking place at a time of big changes in the international system. The era of Pax Americana appears to be over, and the United States is no longer poised to police the world. Not that Pax Americana was necessarily so peaceful. The 1990s were especially disputatious; civil wars arose on multiple continents, as did major wars in Europe and Africa. But the United States attempted to solve and contain many potential conflicts: Washington led a coalition to oust Saddam Hussein’s Iraq from Kuwait, facilitated the Oslo Process to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, fostered improved relations between North and South Korea, and encouraged the growth of peacekeeping operations around the globe. Even following the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States, the invasion of Afghanistan was supported by many in the international community as necessary to remove a pariah regime and enable a long-troubled nation to rebuild. War was not over, but humanity seemed closer than ever to finding a formula for lasting peace.

Over the subsequent decades, the United States seemed to fritter away both the goodwill needed to support such efforts and the means to carry them out. By the early 2010s, the United States was bogged down in two losing wars and recovering from a financial crisis. The world, too, had changed, with power ebbing from Washington’s singular pole to multiple emerging powers. As then–Secretary of State John Kerry remarked in a 2013 interview in The Atlantic, “We live in a world more like the 18th and 19th centuries.” And a multipolar world, where several great powers jostle for advantage on the global stage, harbors the potential for more conflicts, large and small.

Specifically, China has emerged as a great power seeking to influence the international system, whether by leveraging the economic allure of its Belt and Road Initiative or by militarily revising the status quo within its region. Russia does not have China’s economic muscle, but it, too, seeks to dominate its region, establish itself as an influential global player, and revise the international order. Whether Russia or China is yet on an economic or military par with the United States hardly matters. Both are strong enough to challenge the U.S.-led international order by leveraging the revisionist sentiment they share with countries throughout the global South.

(…)

Suppose, though, that the proliferation of wars doesn’t have a systemic cause, but an entirely particular one. That the world owes its present state of unrest directly to Russia—and, even more specifically, to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February of 2022 and its decision to continue fighting since.

The war in Ukraine, the largest war in Europe since World War II and one poised to continue well past 2024, is absorbing the attention of international actors who otherwise would have been well positioned to prevent any of the abovementioned crises from escalating. This case is not the same as the great-power distraction, in which the world’s most powerful states simply fail to focus on emerging crises. Rather, the great powers lack the diplomatic and military capacity to respond to conflicts beyond Ukraine—and other actors know it.

(…)

These three explanations—coincidence, multipolarity, Russia’s war in Ukraine—are not mutually exclusive. If anything, they are interrelated, as wars are complex events; the decline of U.S. hegemony contributes to growing multipolarity; and great-power competition has surely fed Russia’s aggression and the West’s response. The consequence is that others are caught in the great-power cross fire or will seek to start fires of their own. Even if none of these wars rise to the level of a third world war, they will be devastating all the same. We do not need to be in a world war to be in a world at war.

Wars were already a persistent feature of the international system. But they were not widespread. War was always happening somewhere, in other words, but war was not happening everywhere. The above dynamics could change that tendency. The prevalence of war, not just its persistence, could now be our future.”

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thousands rally in Armenia demanding PM’s resignation

Large-scale protests demanding the resignation of Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan continue for a second day following a weekend demonstration.

After a rally of thousands on Sunday and an overnight vigil in pouring rain, hundreds of protesters gathered in front of the Armenian parliament building in Yerevan on Monday.

The demonstrations organised in opposition to the decision to hand over four abandoned border villages to Baku to settle long-standing territorial disputes between the Caucasian neighbours. The territory, which Armenia has controlled since the 1990s, reclaimed last week.

The protests against Pashinyan, who has also led Armenia to cool relations with Russia, are led by Bagrat Galstanyan, an archbishop who at the weekend called for a “new dialogue” with Moscow.

Armenia and Azerbaijan have fought two wars over the Nagorno-Karabakh region, which Azerbaijan reclaimed last year from Armenians who controlled the enclave for three decades. Opponents call the return of the territory a betrayal. Many believe it was Pashinyan’s short-sighted policies that led to the liquidation of Nagorno-Karabakh, forcing hundreds of thousands of Armenians to leave the territory. Pashinyan said it was a necessary step to avoid a new war.

Yerevan accused Baku of ethnic cleansing, which Pashinyan himself acknowledged. “The withdrawal of Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh as a result of Azerbaijan’s policy of ethnic cleansing continues. Analysis shows that in the coming days there will be no more Armenians left in Nagorno-Karabakh. This is a real act of ethnic cleansing and depatriation, which we have been warning the international community about for a long time,” the Armenian Prime Minister said during a government session on September 28.

On Sunday, Galstanyan, who has said he hopes to change the prime minister, announced the start of four days of rallies for his resignation. Galstanyan, who has called on parliament to hold an impeachment vote on Tuesday, said:

“For four days, we will stay in the streets and squares, and with our determination and will, we will achieve victory.”

Thousands of people gathered outside government headquarters on Sunday and then marched to parliament. If the impeachment vote is successful, an interim government will need to form and early parliamentary elections will need to take place.

The protesters promise to keep coming to mass rallies in an attempt to preserve Armenia’s sovereignty and the safety of its citizens.

Read more HERE

#world news#world politics#news#caucasus#armenia#artsakh#nikol pashinyan#azerbaijan#azerbaycan#ilham aliyev#nagornokarabakh

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

🇦🇲🇦🇿 REPUBLIC OF ARTSAKH WILL CEASE TO EXIST SAYS NAGORNO-KARABAKH PRESIDENT SAMVEL SHAHRAMANYAN

The ethnic Armenian enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh located within Azerbaijani territory, also known as the unrecognized Republic of Artsakh, will cease to exist according to its President Samvel Shahramanyan.

"Based on the priority of ensuring the physical security and vital interests of the people of Karabakh, taking into account the agreement reached through the mediation of the command of the Russian peacekeeping contingent with representatives of Azerbaijan that free, voluntary and unimpeded passage of residents of Nagorno-Karabakh, including military personnel who have laid down their arms, with their property is ensured on their vehicles along the Lachin corridor ... a decision was made: to dissolve all state institutions and organizations under their departmental subordination until January 1, 2024, and the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh) ceases to exist," the decree read.

"The population of Nagorno-Karabakh, including those outside the Republic, after the entry into force of this Decree, should familiarize themselves with the conditions of reintegration presented by the Republic of Azerbaijan in order to make an independent and individual decision on the possibility of staying (returning) in Nagorno-Karabakh," the decree said.

The Nagorno-Karabakh region is an ethnic Armenian majority enclave located within Azerbaijani territory.

The modern conflict began with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which had managed the relationship between Armenians and Azeris. As the Soviet Union weakened, the conflict grew in severity.

When the Soviet Union finally collapsed in 1991, Azerbaijan and Armenia each quickly declared their independence and resumed their old dispute over the Nagorno-Karabakh territory.

The guerilla war-style conflict dragged on and by 1994, the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh had won their nominal independence, even as most of the world denied its existence.

But in 2020, after a long period of rearming, modernizing and retraining its armed forces, Azerbaijan launched a massive offensive into Nagorno-Karabakh territory.

The newly modernized Azeri Forces pushed deep into the region. In 44 days, Azerbaijan managed to take several key villages, including the region's second largest city Shusha, and other key positions.

On November 9th, 2020, after the fall of Shusha, a ceasefire agreement was reached and implemented that would see some 2'000 Russian Peacekeeping Forces remain in Nagorno-Karabakh for a period of no less than 5 years to ensure the terms of the peace agreement.

But the peace was shattered on September 19th, 2023 when Azerbaijan launched another massive offensive deep into the Republic of Artsakh territory.

This time however, the Armenian government under Nikol Pashinyan refused to assist Republic of Artsakh forces, and within 24 hours Azeri Forces had mostly overwhelmed the ethnic Armenian enclave's defense forces. A ceasefire was quickly agreed to by Nagorno-Karabakh authorities with Russian Peacekeeping Forces moderating, but the goal of Azerbaijan, to reassert its sovereignty over Nagorno-Karabakh, had been achieved and a flood of ethnic Armenian refugees began pouring through the border into Armenia.

By Thursday, some 65'000 refugees had crossed into Armenian territory and the President of the Republic of Artsakh, Samvel Shahramanyan had announced the dissolution of the Republic of Artsakh.

As many as 120,000 refugees are expected to cross from the Karabakh territory into Armenia in the coming days and weeks.

#source

#source2

#nagorno karabakh#nagornokarabakh#republic of artsakh#artsakh#artsakh republic#south caucuses#news#politics#war news#geopolitics#geopolitics news#geopolitical news#geopolitical events#world news#global news#international affairs#international news#international politics#socialism#communism#marxism leninism#socialist politics#socialist news#socialist#communist#marxism#marxist leninist#workersolidarity#worker solidarity#WorkerSolidarityNews

12 notes

·

View notes

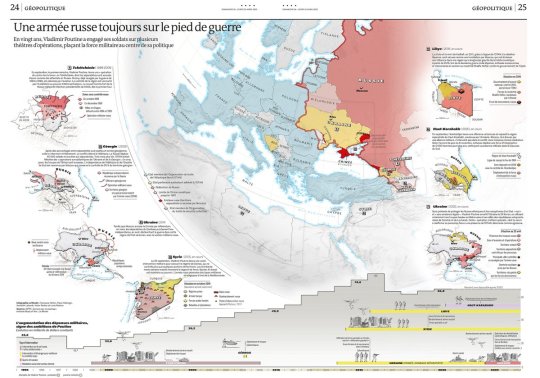

Photo

Russian military operations abroad in the past decades.

by @XemartinLaborde

In twenty years, Vladimir Putin has committed his soldiers to several theaters of operations, placing military force at the center of his policy

Chechnya, 1999-2009: In September, the Prime Minister, Vladimir Putin, launches a “counter-terrorism operation” in Chechnya, whose separatists are accused of having committed attacks in Russia. Grozny, already devastated by the war from 1994 to 1996, was pounded by the air force. Control of the region is locked by the installation in power of Akhmad Kadyrov. Russia's new strongman won the 2000 presidential election in the first round.

Georgia, 2008: After clashes between South Ossetian separatists and the Georgian army, the latter started a military intervention. The conflict spreads to Abkhazia. Russia is deploying 40,000 troops in support of the separatists. Three months earlier NATO had welcomed “the Euro-Atlantic aspirations of Ukraine and Georgia; In five days, the troops of Tbilisi are crushed. The independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia is recognized by Moscow, which retains control of 20% of Georgian territory.

Ukraine, 2014: Annexation of Crimea, and war in Donbas with the military support of Russia

Libya, 2016, in progress: The fall and death of Gaddafi in 2011, thanks to NATO's support for the Libyan rebellion, are experienced as a humiliation by Moscow, which sees its influence diminishing in a region that has long gravity in the Soviet orbit. From 2016, during the second Libyan civil war, Russia sent arms and mercenaries in support of Marshal Khalife Haftar, against the government of Tripoli.

Syria, 2015, in progress: On September 30, Vladimir Putin launched a vast military intervention to rescue the regime in Damascus, which now controls only a small portions of the territory. The massive aerial bombings reversed the balance of power. Bashar Al-Assad is kept in power. The Russian army maintains strategic military bases east of the Mediterranean.

Nagorno-Karabakh, 2020, in progress: At the end of September, Azerbaijan launched a victorious offensive and recaptured the separatist region of Nagorno-Karabakh, supported by Armenia. Moscow, linked to Yerevan by a military alliance, does not intervene in the conflict, but imposes itself as a mediator. According to the November 9 peace agreement, Russia deploys a peacekeeping force of 2,000 men for five years, reinforcing its military presence in the South Caucasus.

Ukraine, 2022, ongoing: Under the guise of protecting ethnic Russians and Russian-speakers from a "nazi" state and “without legal existence", Vladimir Putin invades Ukraine on February 24, using in particular his troops based in Belarus and his allies from the self-proclaimed republics in the cities of Donetsk and Luhansk. This "special military operation" must serve to reaffirm its power in the face of a NATO presence, denounced as aggressive.

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

What are the mobs in Washington defiling iconic federal statues with impunity and pelting police men really protesting?

What are the students at Stanford University vandalizing the president’s office really demonstrating against?

What are the throngs in London brazenly swarming parks and rampaging in the streets really angry about?

Occupations?

They could care less that the Islamist Turkish government still stations 40,000 troops in occupied Cyprus. No one is protesting against the Chinese takeover of a once-independent Tibet or the threatened absorption of an autonomous Taiwan.

Refugees?

None of these mobs are agitating on behalf of the nearly 1 million Jews ethnically cleansed since 1947 from the major capitals of the Middle East. Some 200,000 Cypriots displaced by Turks earn not a murmur. Nor does the ethnic cleansing of 99% of Nagorno-Karabakh’s ancient Armenian population just last year.

Civilian casualties?

The global protestors are not furious over the 1 million Uighurs brutalized by the communist Chinese government. Neither are they concerned about the Turkish government’s indiscriminate war against the Kurds or its serial threats to attack Armenians and Greeks.

The new woke jihadi movement is instead focused only on Israel and “Palestine.” It is oblivious to the modern gruesome Muslim-on-Muslim exterminations of Bashar el-Assad and Saddam Hussein, the Black September massacres of Palestinians by Jordanian forces, and the 1982 erasure of thousands in Hama, Syria.

So woke jihadism is not an ecumenical concern for the oppressed, the occupied, the collateral damage of war, or the fate of refugees. Instead, it is a romanticized and repackaged anti-Western, anti-Israel, and anti-Semitic jihadism that supports the murder of civilians, mass rape, torture, and hostage-taking.

But what makes it now so insidious is its new tripartite constituency?

First, the old romantic pro-Palestine cause was rebooted in the West by millions of Arab and Muslim immigrants who have flocked to Europe and the U.S. in the last half-century.

Billions of dollars in oil sheikdom “grant” monies swarmed Western universities to found “Middle Eastern Studies” departments. These are not so much centers for historical or linguistic scholarship as political megaphones focused on “Zionism” and “the Jews.”

Moreover, there may be well over a half-million affluent Middle Eastern students in Western universities. Given that they pay full tuition, imbibe ideology from endowed Middle Eastern studies faculty, and are growing in number, they logically feel that they can do anything with impunity on Western streets and campuses.

Second, the Diversity/Equity/Inclusion movement empowers the new woke jihadis. Claiming to be non-white victims of white Jewish colonialism, they pose as natural kindred victims to blacks, Latinos, and any Westerner now claiming oppressed status.

Black radicalism, from Al Sharpton to Louis Farrakhan to Black Lives Matter, has had a long, documented history of anti-Semitism. It is no wonder that its elite eagerly embraced the anti-Israeli Palestine movement as fellow travelers.

The third leg of woke jihadism is mostly affluent white leftist students at Western universities.

Sensing that their faculties are anti-Israel, their administrations are anti-Israel (although more covertly) and the most politically active among the student body are anti-Israel, European and American students find authenticity in virtue-signaling their solidarity with Hamas, Hezbollah, and radical Islamists in general.

Given the recent abandonment of standardized tests for admission to universities, the watering-down of curricula, and rampant grade inflation, thousands of students at elite campuses feel that they have successfully redefined their universities to suit their own politics, constituencies and demographics.

Insecure about their preparation for college and mostly ignorant of the politics of the Middle East, usefully idiotic students find resonance by screaming anti-Semitic chants and wearing keffiyehs.

Nurtured in grade school on the Marxist binary of bad, oppressive whites versus good, oppressed nonwhites, they can cheaply shed their boutique guilt by joining the mobs.

The result is a bizarre new anti-Semitism and overt support for the gruesome terrorists of Hamas by those who usually preach to the middle class about their own exalted morality.

Still, woke jihadism would never have found resonance had Western leaders—vote-conscious heads of state, timid university presidents, and radicalized big-city mayors and police chiefs—not ignored blatant violations of laws against illegal immigration, vandalism, assault, illegal occupation, and rioting.

Finally, woke jihadism is fueling a radical Western turn to the right, partly due to open borders and the huge influx into the West from non-Western illiberal regimes.

Partly the reaction is due to the ingratitude shown their hosts by indulged Middle-Eastern guest students and green card holders.

Partly, the public is sick of the sense of entitlement shown by pampered, sanctimonious protestors.

And partly the revulsion arises against left-wing governments and universities that will not enforce basic criminal and immigration statutes in fear of offending this strange new blend of wokism and jihadism.

Yet the more violent campuses and streets become, the more clueless the mobs seem about the cascading public antipathy to what they do and what they represent.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Please, keep your eyes on Armenia and Artsakh, the invasion is not over and the fascist dictator of Azerbaijan - Aliev, has been more and more aggressive in his words lately. From openly admitting to starting the second Nagorno-Karabakh war (the fact they were bent over on not doing and blaming Armenia for "provocations") to openly threatening Armenia's sovereignty and lives of armenians in Artsakh. People's indifference is what making this blood thirsty country so confident in itself. CONTACT YOUR GOVERNMENT, SIGN A PETITION, DONATE! There's a real threat of another genocide but I don't see protests in european capitals and armenian flags hanging from every governmental building - why is so?

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Please note: I write this not to blame Armenia for the fall of Artsakh and the displacement of Armenians there, but to point out the tragic ironies of being a small state dependent on larger ones.

The hatred between Armenians and Azeris dates to the last days of the Soviet Union, when both Armenia and Azerbaijan for SSRs. The Armenian majority in Nagorno-Karabakh began discussing secession from Azerbaijan (to which the Soviets had awarded that territory in the 1920s) and enosis with Armenia. The response was pogroms against Armenians in Azerbaijan that killed hundreds. Police did not interfere, and in many cases aided the mob. Ethnic violence spread to Armenia and, upon independence, war soon broke out. Shortly nearly all Azeris were ethnically cleansed from Armenian-controlled territory and Armenians from Azerbaijani. Armenians successfully took Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding districts, naming it Artsakh. Meanwhile, Azerbaijan went to work destroying all traces of Armenian heritage in its country.

At that time, both countries used Soviet weapons and were supplied by Russia. It would not take long, however, for Turkey to take the linguistically-related Azeris under its wing. This forced Christian Armenia firmly into the Russian camp. As Turkey is a NATO member, Azerbaijan now had access to Western equipment, access to which Armenia was largely denied.

The problem is that Azerbaijan has remained a dynastic dictatorship while Armenia has not only attempted to democratize but also stamp out corruption. Russia did not appreciate this. It does not brook political independence within its sphere of influence. Further, as we saw in Ukraine, corruption keeps a state weak and dependent on its hegemon, while clean and functional government is a threat to the Putin regime by offering a local alternative to the Kremlin kleptocracy.

This meant that, when Armenians needed help most, Russia was both too distracted by its aggression in Ukraine to supply aid or "peacekeepers", but it actively didn't want to. Russia is more politically aligned with the Azerbaijani style, and was motivated to punish Armenia for its insolence. The best way to do this was to stand back and let Azerbaijan destroy Artsakh, leaving Armenia with no friends in a tough neighborhood.

If there is a lesson to this, trust not Russia, don't expect to gain international sympathy by appealing to Iran to open up a second front, as some Armenian commentators have done, and expect Turkey to fall ever deeper into the throes of Turanist fantasy.

But mostly I just feel for all the people ethnically sorted at a time when people should be learning to live in peace together.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have two sets of questions, one regarding the Russo-Ukrainian War and the other regarding Turkey.

The first is about sending main battle tanks to the Ukrainians. I'm sure you know the British are sending 14 Challenger II tanks and the Poles are poised to send several Leopard II's. One question I have is how impactful do you think these tanks will be? And as an extra question, do you agree with the Pentagon's assessment that sending M1 Abrams tanks is is not what the Ukrainian's need, and that they would be better off receiving other forms of materiel?

My second question is in regards to Erdoğan's stance on NATO and Russia as a whole. I'm sure you saw that Erdoğan said that Turkey will not grant Sweden NATO membership after right wingers in Sweden burned several copies of the Quran. Clearly Erdoğan is just using this as an excuse to deny Sweden NATO status. But why? Why deny Sweden NATO membership, what does he gain from doing that? And by other question regarding Erdoğan and Turkey is their relationship with Russia. The Turks plan to buy S-400 missiles from Russia are are interested in buying Su-57's, but at the same time the Turks have been fighting the Russians in Syria, supported Ukraine since Crimea was annexed, and supported opposing sides in the Libyan Civil War and in the Nagorno-Karabakh War. So why are they willing to do business with each other?

Sorry for the bombardment of questions.

If the Ukrainians can develop an armor unit with Leopard II's and IFV support such as Bradleys, it can become a frighteningly effective force against the Russians. As we've seen in the Russo-Ukrainian war, Russian artillery targeting moves at a slug's pace, so a mobile armor unit can hit hard and be on the move before taking battery fire. It would be quite useful in establishing a thrust toward Melitopol and severing the land bridge to Crimea and potentially severing the Russian forces in two.

The Abrams would have problems in being deployed - the Leopard is definitely more effective given the terrain. I wouldn't underestimate the Ukrainians in understanding and adapting the Abrams, but I do understand that most repair and refit facilities can't service an Abrams engine, whereas the Leopards can just be shunted over the border to Poland. But at the same time, we've got Abrams that we aren't using, even for training, so I'm okay with sending a few Abrams if it puts egg on Olaf Scholz's face and gets him to release the Leopards.

Erdogan is facing severe problems at home. His very stupid Fisherist economic policies have caused inflation in Turkey to skyrocket, and so he's trying to salvage the upcoming elections by picking fights and pandering to the nationalist base. Erdogan wants to pick fights with Kurds, with Greece, and with Sweden to tell the people back home that he's fighting for Turkey's place as a pre-eminent power, coupling that with selling the grain deal to say that he's no mindless bravo. Make no mistake, Erdogan's stance on Sweden joining NATO has absolutely nothing to do with Turkish strategy and everything to do with Erdogan preserving his political career. After all, given the release of the Su-57 data on Warthunder, it's obvious that the plane is comparable in stealth to 30-year old aircraft, any modern radar system is going to light up like a Christmas tree. It has 0.1-1m² RCS, no sensible strategist would want to purchase the Su-57 with that large of a radar cross-section. It isn't stealthy, so either buy an aircraft that is or buy a cheaper or more effective multirole platform without stealth. It does fit into Erdogan's strategy of painting itself as an interlocutor between Russia and the West, again to sell Turkey as a pre-eminent power capable of producing great geopolitical feat.

It won't work out in Erdogan's favor, but he's backed himself into a corner and would rather ruin Turkey than lose.

Thanks for the question, Bruin.

SomethingLikeALawyer, hand of the King

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Azerbaijan’s armed forces conducted large scale air defense drills, the Azeri Ministry of Defense announced on Wednesday, including live-firing of the Israeli made Barak-8 ER air defense system.

According to the statement, the Barak-8 detected and destroyed a ballistic missile “launched by an imaginary enemy.” Israel has had a strategic alliance with Azerbaijan for the past two decades, selling the large Shi’ite-majority country weapons worth billions of dollars – and in return, Azerbaijan, per sources, supplies Israel with oil and access to Iran.[...]

Israel and Azerbaijan took their relationship up a level in 2011 with a huge $1.6 billion deal that included a battery of Barak missiles for intercepting aircraft and missiles, as well as Searcher and Heron drones from Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI). It was reported that near the end of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in 2020, a Barak battery shot down an Iskander ballistic missile launched by Armenia.

An investigation by Haaretz in March revealed that over the past seven years, 92 cargo flights flown by Azerbaijani Silk Way Airlines have landed at the Ovda airbase, the only airfield in Israel through which explosives may be flown into and out of the country. The investigation found the number of flights spiked during periods of fighting against Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Since March, there have been 11 more Azeri flights, including 5 in the past two weeks, totaling 103 flights in 7 years.

13 Sep 23

18 Sep 23

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Q: Have you ever wrote a poem or a song that provoked an emotion from you as you were reciting/ performing it? Did it make you cry as you listened to what you were saying?

Travel. Sudden lightning flash in daylight.

A word others use. "So from today I'm

trav'lin' light." As in atoms. The white

flash of a device going off. My grime

and bits settling down on your surprised

face. You. Someone had to plant these ghastly

boxes under this hill's skin. You surmised

there are hundreds. Children have already

stumbled on four. We. Travel with me here.

I want you here when I mess up. Just once.

Wave your hands. Call out my name. You can hear

the light. Count the seconds. The short distance

it takes to get to you. A blur. Crayon

red. I rise up and all at once I'm gone.

The line, “So from today I’m/ travelin’ light,” comes from a Billie Holiday classic.

The background for this poem happened around 12 or 13 years ago when I had exchanged a couple of emails with a volunteer landmine deminer in the Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) region of Armenia who talked about losing a friend whose device that she had been trying to defuse went off. “She was there and then she wasn’t.” That image stayed with me for a very long time. I’ve done a lot of things in life but nothing compares to those people who are forced to deal with all the unexploded ordnance left behind, often decades later, due to somebody else’s war.

The United Nations estimates that there are currently as many as 100 million unexploded landmines buried around the world. Mines are designed to be difficult to locate and their clearance is costly in terms of both money and lives. It is estimated that, in 2021, more than 5,500 people were killed or maimed by landmines, most of them were civilians, half of whom were children.

To answer your question, I wasn’t expecting this poem to get to me as it did. I hadn’t gotten choked up when I wrote it. By the time, though, I got to, “Call out my name,” I had developed that sobbing-stutter one gets when trying to talk and not lose it at the same time. It was a very odd sensation.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top Armenian official blames Moscow for loss of Nagorno-Karabakh and 2020 war with Azerbaijan

Armenian Security Council Secretary Armen Grigoryan accused Russia on Wednesday of facilitating Azerbaijan’s takeover of the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh in September 2023. “This happened when we depended completely on Russia,” he said at a press briefing. “Russia came, took Nagorno-Karabakh from us, handed it over to Azerbaijan, and then left — that’s the reality. I’m asserting that Russia took Nagorno-Karabakh.” Grigoryan went on to say that the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War would not have broken out “without Russia’s permission.” Earlier this month, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan announced that his country would leave the Moscow-led CSTO military alliance.

3 notes

·

View notes