#so i took the structure of book lungs and adapted that to human lungs

Text

What a nice and normal drawing to post after vanishing for 2 and a half months. I'm sure there was no weird and unhinged process for figuring this pose out that entailed inventing organs that all occurred in the space of around 10 hours or anything.

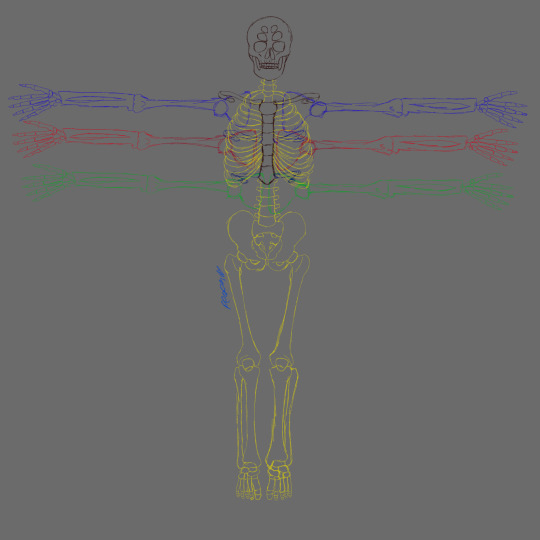

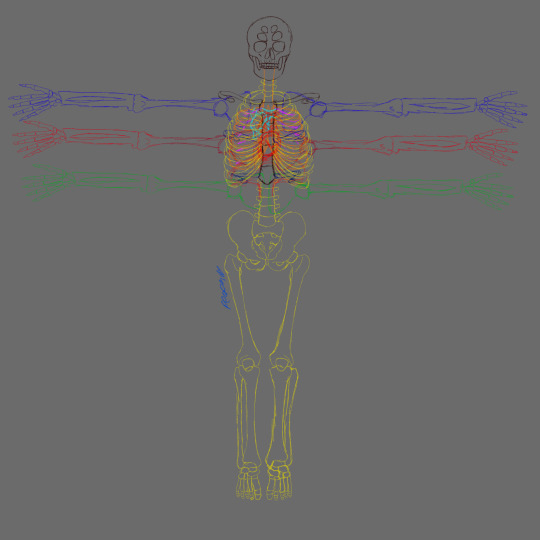

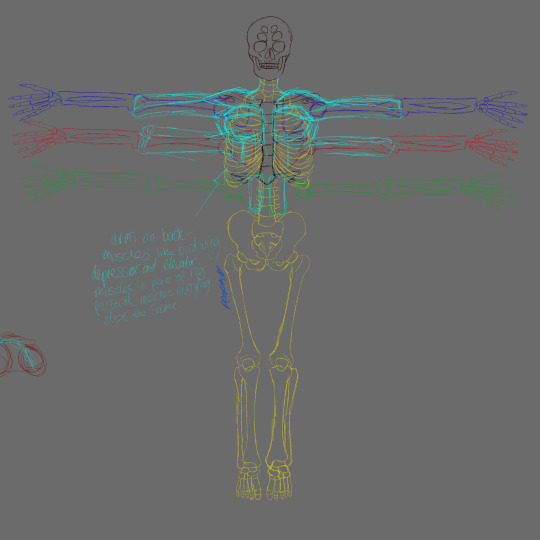

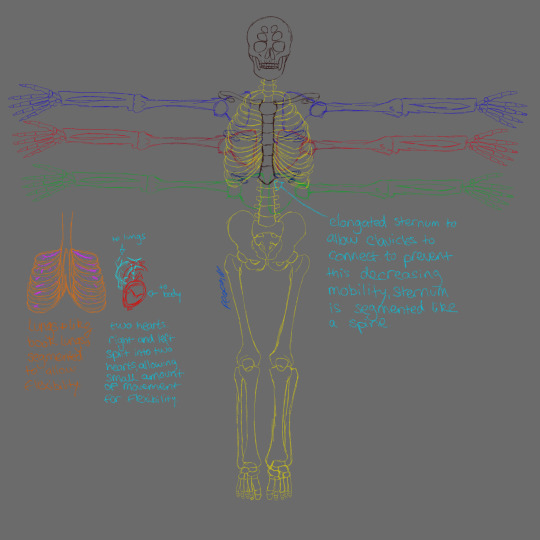

#my art#original character#oc#oc artwork#oc art#I had to extend her sternum for her third set of arms#because i needed her collarbone to attach to it#but shes a contortionist and that limits movement#so my totally normal solution was making it segmented so it can move like a spine#but that means her organs are at risk of being damaged#lucky for me spiders have book lungs#which are thin air pockets which blood runs through and thats how gas exchange occurs#but spiders breathe through their skin so i couldnt just use book lungs#so i took the structure of book lungs and adapted that to human lungs#so her lungs are layered but still have the exact same function as human lungs#but her heart was also a problem because that could be damaged too#so my solution was a weird combination of octopus heart where they have a heart that pumps blood around the body and one per gill#and snake hearts where they move them to keep it safe when feeding#so she has two hearts#one that pumps blood through her lungs and one that pumps blood through her body#and because her rib cage is longer they have a small amount of room to move so they stay unharmed#i really want to look into how this will effect medical equipment like pacemakers next#as well as how limb differences will present in the multiple arms#it also means that any lung issues are less likely to be deadly as quickly because if one layer is damaged or sick it can be removed easier#anyways so I started meds yesterday and this is a direct consequence of that ♡

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Enola Holmes: A Not So Elementary Adaptation

It's cliché and a bit unfair to say that the book was better than the film, but I'm afraid that's precisely where I need to start. Nancy Springer's Enola Holmes: The Case of the Missing Marquess is leagues better than Netflix's adaptation of it. They did her work dirty and to say that I'm shocked at the accolades other reviewers are heaping on the film is an understatement. Before I dive into any critiques though, it's worth acknowledging that not every minute of the two hour film was painful to get through. So what worked in Enola Holmes?

The film is carried by the talent of its cast, Millie Bobby Brown being the obvious heavy-hitter. She helps breathe life into a pretty terrible script and it's only a shame her talent is wasted on such a subpar character.

The idea to have Enola continually break the fourth wall, though edging into the realm of Dora the Explorer at times—"Do you have any ideas?"— was nevertheless a fun way to keep the audience looped into her thought process. Young viewers in particular might enjoy it as a way to make them feel like a part of the action and older viewers will note the Fleabag influence.

The cinematography is, perhaps, where most of my praise lies. The rapid cuts between past and present, rewinding as Enola thinks back to some pertinent detail, visualizing the cyphers with close ups on the letter tiles—all of it gave the film an upbeat, entertaining flair that almost made up for how bloated and meandering the plot was.

We got an equally upbeat soundtrack that helped to sell the action.

The overall experience was... fine. In the way a cobbled together, candy-coated, meant to be seen on a Friday night but we watched it Wednesday and then promptly forgot about it film is fine. I doubt Enola Holmes will be winning any awards, but it was a decently entertaining romp and really, does a Netflix film need to be anything more? If Enola was her own thing made entirely by Netflix's hands I wouldn't be writing this review. As it stands though, Enola is both an adaptation and the latest addition to one of the world’s most popular franchises. That's where the film fails: not as a fun diversion to take your mind off Covid-19, but as an adaptation of Springer's work and as a Sherlock Holmes story.

In short,��Enola Holmes, though pretty to look at and entertaining in a predictable manner, still fails in five crucial areas:

1. Mycroft is Now a Mustache-Twirling Villain and Sherlock is No Longer Sherlock Holmes

This aspect is the least egregious because admittedly the film didn't pull this version of Mycroft out of thin air. As the head of the household he is indeed Enola's primary antagonist (outside of some kidnappers) and though he insists that he's doing all this for Enola's own good, he does get downright cruel at times:

He rolled his eyes. “Just like her mother,” he declared to the ceiling, and then he fixed upon me a stare so martyred, so condescending, that I froze rigid. In tones of sweetest reason he told me, “Enola, legally I hold complete charge over both your mother and you. I can, if I wish, lock you in your room until you become sensible, or take whatever other measures are necessary in order to achieve that desired result... You will do as I say" (Springer 69).

Mycroft's part is clear. He's the white, rich, powerful, able-bodied man who benefits from society's structure and thus would never think to change it. He does legally have charge over both Enola and Eudoria. He can do whatever he pleases to make them "sensible"... and that right there is the horror of it. Mycroft is a law-abiding man whose antagonism stems from doing precisely what he's allowed to do in a broken world. There are certainly elements of this in the Netflix adaptation, but that antagonism becomes so exaggerated that it's nearly laughable. Enola's governess (appointed by Mycroft) slaps her across the face the moment she speaks up. Mycroft screams at her in a carriage until she's cowering against the window. He takes her and throws her into a boarding school where everything is bleak and all the women dutifully follow instructions like hypnotized dolls. Enola Holmes ensures that we've lost all of Springer's nuance, notably the criticism of otherwise decent people who fall into the trap of doing the "right" (read: expected) thing. Despite her desire for freedom, in the novel Enola quickly realizes that she is not immune to society's standards:

"I thought he was younger.” Much younger, in his curled tresses and storybook suit. Twelve! Why, the boy should be wearing a sturdy woollen jacket and knickers, an Eton collar with a tie, and a decent manly haircut—

Thoughts, I realised, all too similar to those of my brother Sherlock upon meeting me (113-14).

She is precisely like her brothers, judging a boy for not looking and acting enough like a man just as they judged her for not looking and acting enough like a lady. The difference is that Enola has chaffed enough against those expectations to realize when she's falling prey to them, but the sympathetic link to her brothers remains. In the film, however, the conflict is no longer driven by fallible people doing what they think is best. Rather, it's made clear (in no uncertain terms) that these are just objectively bad people. Only villains hit someone like that. Only villains will scream at the top of their lungs until a young girl cries. Only villains roll their eyes at women's rights (a subplot that never existed in the novel). Springer writes Mycroft as a person, Netflix writes him as a cartoon, and the result is the loss of a nuanced message about what it means to enact change in a complicated world.

Which leaves us with Sherlock. Note that in the above passage he is the one who casts harsh judgement on Enola's outfit. Originally Mycroft took an interest in making Enola "sensible" and Sherlock— in true Holmes fashion—straddles a fine line between comfort and insult:

"Mycroft,” Sherlock intervened, “the girl's head, you'll observe, is rather small in proportion to her remarkably tall body. Let her alone. There is no use confusing and upsetting her when you'll find out for yourself soon enough'" (38).

***

"Could mean that she left impulsively and in haste, or it could reflect the innate untidiness of a woman's mind,” interrupted Sherlock. “Of what use is reason when it comes to the dealings of a woman, and very likely one in her dotage?" (43).

A large part of Enola's drive stems from proving to Sherlock, the world, and even herself that a small head does not mean lack of intelligence. His insults, couched in a misguided attempt to sooth, is what makes Sherlock a complex character and his broader sexism is what makes him a flawed character, not Superman in a tweed suit. Yet in the film Mycroft becomes the villain and Sherlock is his good brother foil. Rather than needing to acknowledge that Enola has a knack for deduction by reading the excellent questions she's asked about the case—because why give your characters any development?—he already adores and has complete faith in her, laughing that he too likes to draw caricatures to think. By the tree Sherlock remanences fondly about Enola's childhood where she demonstrated appropriately quirky preferences for a genius, things like not wearing trousers and keeping a pinecone for a pet. They have a clear connection that Mycroft could never understand, one based both in deduction and, it seems, being a halfway decent human being. We are told that Enola has Sherlock's wits, but poor Mycroft lucked out, despite the fact that up until this point the film has done nothing to demonstrate this supposed intelligence. (To say nothing of how canonically Mycroft's intellect rivals his brother's.) Enola falls to her knees and begs for Sherlock's help, saying that "For [Mycroft] I'm a nuisance, to you—" implying that they have a deep bond despite not having seen one another since Enola was a toddler. Indeed, at one point Enola challenges Lestrade to a Sherlock quiz filled with information presumably not found in the newspaper clippings she's saved of him, which begs the question of how she knows her brother so well when she hasn't seen him in a decade and he, in turn, walked right by her with no recognition. Truthfully, Lestrade should know Sherlock better. Through all this the sibling bond is used as a heavy-handed insistence that Enola is Sherlock's protégé, him leaving her with the advice that "Those kinds of mysteries are always the best to unpick” and straight up asking at one point if she’s solved the case. The plot has Enola gearing up to outwit her genius brother, which did not happen in the novel and is precisely why I loved it. Enola isn't out to be a master of deduction in her teens, she's a finder of lost people who uses a similar, but ultimately unique set of skills. She does things Sherlock can't because she is isn't Sherlock. They're not in competition, they're peers, yet the film fails to understand that, using Sherlock's good brother bonding to emphasize Enola's place as his protégé turned superior. He exists, peppered throughout the film, so that she can surpass him in the end.

You know what happens in the novel? Sherlock walks away from her, dismissive, and that's that.

That's also Sherlock Holmes. I won't bore you with complaints about Cavill being too handsome and Claflin being too thin for their respective parts, but I will draw the line at complete character assassination. Part of Sherlock's charm is that he's far more compassionate than he first appears, but that doesn't mean he would, at the drop of a telegram, become a doting older brother to a sister of all things. Despite the absurdity of the Doyle Estate's lawsuit against Netflix for making Sherlock an emotional man who respects women... they're right that this isn't their character. Oh, Sherlock is emotive, but it's in the form of excited exclamations over clues, or the occasional warm word towards Watson—someone he has known and lived with for many years. Sherlock respects women, though it's through those societal expectations. He'll offer them a seat, an ear, a handkerchief if they need one, and always the promise of help, but he then dismisses them with, "The fairer sex is your department, Watson." Springer successfully wrote Sherlock Holmes with a little sister, a man who will bark out a laugh at her caricature but still leave her to Mycroft's whims because he has his own life to tend to. This is a man who insists that the mind of a woman is inscrutable and thus must grapple with his shock at Enola's ability to cover the "salient points" of the case (58). Cavill's Sherlock is no Sherlock at all and though there's nothing wrong with updating a character for a modern audience (see: Elementary), I do question why Netflix strayed so far from Springer's work. The novel is, after all, their blueprint. She already managed the difficult task of writing an in-character Sherlock Holmes who remains approachable to both a modern audience and Enola herself, yet for some reason Netflix tossed that work aside.

2. Enola is "Special,” Not At All Like Other Girls

Allow me to paint you a picture. Enola Holmes is an empathetic, fourteen-year-old girl who, while bright, does not possess an intelligence worthy of note. No one is gasping as she deduces seemingly impossible things from the age of four, or admiring her knowledge of some obscure, appropriately impressive topic. Rather, Enola is a fairly normal girl with an abnormal upbringing, characterized by her patience and willingness to work. Deciphering the many hiding places where her mother stashed cash takes her weeks, requiring that Enola work through the night in secrecy while maintaining appearances during the day. She manages to hatch a plan of escape that demonstrates the thought she's put into it without testing the reader's suspension of disbelief. More than that, she uses the feminine tools at her disposal to give herself an edge: hiding her face behind a widow's veil and storing luggage in the bustle of her dress. Upon achieving freedom, her understanding of another lonely boy leads her to try and help him, resulting in a dangerous kidnapping wherein Enola acts as most fourteen-year-olds would, scared out of her mind with a few moments of bravery born of pure survival instinct. She and Tewksbury escape together, as friends, before Enola sets out on becoming the first scientific perditorian, a finder of lost people.

Sadly, this new Enola shares little resemblance with her novel counterpart. What Netflix seemingly fails to understand is that giving a character flaws makes them relatable and that someone who looks more like us is someone we can connect with. This Enola, simply put, is extraordinary. She's read all the books in the library, knows science, tennis, painting, archery, and a deadly form of Jujitsu (more on that below). In the novel Enola bemoans that she was never particularly good at cyphers and now must improve if she has any hope of reading what her mother left her. In the film she simply knows the answers, near instantaneously. Enola masters her travels, her disguises, and her deductions, all with barely a hitch. Though Enola doesn't have impressive detective skills yet, her memory is apparently photographic, allowing her to look back on a single glance into a room, years ago, and untangle precisely what her mother was planning. It's a BBC Sherlock-esque form of 'deduction' wherein there's no real thought involved, just an innate ability to recall a newspaper across the room with perfect clarity. The one thing Enola can't do well is ride a bike which, considering that in the novel she quite enjoys the activity, feels like a tacked on "flaw" that the film never has to have her grapple with.

More than simply expanding upon her skillset—because let’s be real, it’s not like Sherlock himself doesn’t have an impressive list of accomplishments. Even if Enola’s feelings of inadequacy are part of the point Springer was working to make—the film changes the core of her personality. I cannot stress enough that Enola is a sheltered fourteen-year-old who is devastated by the disappearance of her mother and terrified by the new world she's entered. That fear, uncertainty, and the numerous mistakes that come out of it is what allowed me to connect with Enola and go, "Yeah. I can see myself in her." Meanwhile, this new Enola is overwhelmingly confident, to the point where I felt like I was watching a child's fantasy of a strong woman rather than one who actually demonstrates strength by overcoming challenges. For example, contrast her meeting with Sherlock and Mycroft on the train platform with what we got in the film:

"And to my annoyance, I found myself trembling as I hopped off my bicycle. A strip of lace from my pantalets, confounded flimsy things, caught on the chain, tore loose, and dangled over my left boot.

Trying to tuck it up, I dropped my shawl.

This would not do. Taking a deep breath, leaving my shawl on my bicycle and my bicycle leaning against the station wall, I straightened and approached the two Londoners, not quite succeeding in holding my head high" (31-32).

***

"Well, if they did not desire the pleasure of my conversation, it was a good thing, as I stood mute and stupid... 'I don't know where she's gone,' I said, and to my own surprise—for I had not wept until that moment—I burst into tears" (34).

I'd ask where this frightened, fumbling Enola has gone, but it's clear that she never existed in the script to begin with. The film is chock-full of her being, to be frank, a badass. She gleefully beats up the bad guys in perfect form, no, "I froze, cowering, like a rabbit in a thicket" (164). This Enola always gets the last word in and never falters in her confident demeanor, no, "I wish I could say I swept with cold dignity out of the room, but the truth is, I tripped over my skirt and stumbled up the stairs" (70). Enola is the one, special girl in an entire school who can see how rigid and horrible these social expectations are, straining against them while all her lesser peers roll their eyes. That's how she's characterized: as "special," right from the get-go, and that eliminates any growth she might have experienced over the course of the film. More than that, it feels like a slap in the face to Springer's otherwise likeable, well-rounded character.

3. A Focus on Hollywood Action and Those Strong Female Characters

It never fails to amaze me how often Sherlock Holmes adaptations fail to remember that he is, at his core, an intellectual. Sure, there's the occasional story where Sherlock puts his boxing or singlestick skills to good use, and he did survive his encounter with Moriarty thanks to his own martial arts, but these moments are rarities across the canon. Pick up any Sherlock Holmes story, open to a random page, and you will find him sitting fireside to mule over a case, donning a disguise to observe the suspects, or combing through his many papers to find that one, necessary scrap of information. Sherlock Holmes is about deduction, a series of observations and conclusions based on logic. He's not an action hero. Nor is Enola, yet Netflix seems to be under the impression that no audience can survive a two hour film without something exploding.

I'd like to present a concise list of things that happened in the film that were, in my opinion, unnecessary:

Enola and Tewksbury throw themselves out of a moving train to miraculously land unharmed on the grass below.

Enola uses the science knowledge her mother gave her to ignite a whole room of gunpowder and explosives, resulting in a spectacle that somehow doesn't kill her pursuer.

Enola engages in a long shootout with her attacker, Tewksbury takes a shot straight to the chest, but survives because of a breastplate he only had a few seconds to put on and hide beneath his shirt. Then Enola succeeds in killing Burn Gorman's slimy character.

Enola beats up her attackers many, many times.

This right here is the worst change to her character. Enola is, plainly put, a "strong woman." Literally. She was trained from a young age to kick ass and now that's precisely what she'll do. Gone is the unprepared but brave girl who heads out onto the dangerous London streets in the hope of helping her mother and a young boy. What does this Enola have to fear? There's only one martial arts move she hasn't mastered yet and, don't worry, she gets it by the end of the film. Enola suffers from the Hollywood belief that strong women are defined solely as physically capable women and though there's nothing wrong with that on the surface, the archetype has become so prevalent that any deviation is seen as too weak—too princess-y—to be considered feminist. If you're not kicking ass and taking names then you can only be passive, right? Stuck in a tower somewhere and awaiting your prince. But what about me? I have no ability to flip someone over my shoulder and throw them into a wall. What about pacifists? What about the disabled? By continually claiming that this is what a "strong" woman looks like you eliminate a huge number of women from this pool. The women we are meant to uphold in this film—Enola, her Mother, and her Mother's friend from the teahouse—are all fighters of the physical variety, whereas the bad women like Mrs. Harris and her pupils are too cultured for self-defense. They're too feminine to be feminist. But feminism isn't about your ability to throw a punch. Enola's success now derives from being the most talented and the most violent in the room, rather than the most determined, smart, and empathetic. She threatens people and lunges at them, reminding others that she's perfectly capable of tying up a guy is she so chooses because "I know Jujitsu." Enola possesses a power that is just as fantastical as kissing a frog into a prince. In sixteen short years she has achieved what no real life woman ever will: the ability to go wherever she pleases and do whatever she wants without the threat of violence. Because Enola is the violence. While her attacker is attempting to drown her with somewhat horrific realism, Enola takes the time to wink at the audience before rearing back and bloodying his nose. After all, why would you think she was in any danger? Masters of Jujitsu with an uncanny ability to dodge bullets don't have anything to fear... unlike every woman watching this film.

It's certainly some kind of wish fulfillment, a fantasy to indulge in, but I personally preferred the original Enola who never had any Hollywood skills at her disposal yet still managed to come out on top. That's a character I can see myself in and want to see myself in given that the concept of non-violent strength is continually pushed to the wayside. Not to mention... that's a Sherlock Holmes story. Coming out on top through intellect and bravery alone is the entire point of the genre, so why Netflix felt the need to turn Enola into an action hero is beyond me.

4. Aging Up the Protagonists (and Giving Them an Eye-Rolling Romance)

The choice to age up our heroes is, arguably, the worst decision here. In the original novel Enola has just turned fourteen and Tewksbury is a child, twelve-years-old, though he looks even younger. It's a story for a younger audience staring appropriately young heroes, with the protagonists' status as children crucial to one of the overarching themes of the story: what does it really mean to strike out on your own and when are you ready for it? Adding two years to Enola's age is something I'm perfectly fine with. After all, the difference between fourteen and sixteen isn't that great and Brown herself is sixteen until February of 2021, so why not aim for realism and make her character the same? That's all reasonable and this is, indeed, an adaptation. No need to adhere to every detail of the text. What puzzles me though is why in the world they would take a terrified, sassy, compassionate twelve-year-old and turn him into a bumbling seventeen-year-old instead?

Ah yes. The romance.

In the same way that I fail to understand the assumption that a film needs over-the-top action to be entertaining, I likewise fail to understand the assumption that it needs a romance—and a heterosexual one to boot. There's something incredibly discomforting in watching a film that so loudly proclaim itself as feminist, yet it takes the strong friendship between two children and turns it into an incredibly awkward, hetero True Love story. Remember when Enola loudly proclaims that she doesn't want a husband? The film didn't, because an hour later she's stroking her hand over Tewksbury's while twirling her hair. Which isn't to say that women can't fall in love, or change their minds, just that it's disheartening to see a supposedly feminist film so completely fall into one of the biggest expectations for women, even today. Forget Enola running up to men and paying them for their clothes as an expression of freedom, is anyone going to acknowledge that narratively she’s still stuck living the life the men around her want? Find yourself a husband, Enola. The heavy implication is she did, just with Jujitsu rather than embroidery. Different method, same message, and that’s incredibly frustrating when this didn’t exist in the original story. “It's about freedom!” the film insists. So why didn't you give Enola the freedom to have a platonic adventure?

It's not even a good romance. Rather painful, really. When Tewksbury, after meeting her just once before, passionately says "I don't want to leave you, Enola" because her company is apparently more important than him staying alive, I literally laughed out loud. It's ridiculous and it's ridiculously precisely because it was shoe-horned into a story that didn't need it. More than simply saddling Enola with a bland love interest though, this leads to a number of unfortunate changes in the story's plot, both unnecessary additions and disappointing exclusions. Enola no longer meets Tewksbury after they've both been kidnapped (him for ransom and her for snooping into his case), but rather watches him cut himself out of a carpetbag on the train. I hope I don't have to explain which of these scenarios is more likely and, thus, more satisfying. Meeting Tewksbury on the train means that Enola gets to have a nighttime chat with him about precisely why he ran away. Thus, when she goes to his estate she no longer needs to deduce his hiding spot based on her own desires to have a place of her own, she just needs to recall that a very big branch nearly fell on him and behold, there that branch is. (The fact that the branch is a would-be murder weapon makes its convenient placement all the more eye-rolling.) Rather than involving herself in the case out of empathy for the family, Enola loudly proclaims that she wants nothing to do with Tewksbury and only reluctantly gets involved when it's clear his life is on the line. And that right there is another issue. In the novel there is no murderous plot in an attempt to keep reform bills from passing. Tewksbury is a child who, like Enola, ran away and quickly discovers that life with an overbearing mother isn't so bad when you've experienced London's dangerous streets. That's the emotional blow: Enola has no mother to go home to anymore and must press out onto those streets whether she's ready for it or not.

Perhaps the only redeeming change is giving Tewksbury an interest in flowers instead of ships. Regardless of how overly simplistic the feminist message is, it is a nice touch to give the guy a traditionally feminine hobby while Enola sharpens her knife. The fact that Enola learned that from her mother and Tewksbury learned botany from his father feels like a nudge at a far better film than Enola Holmes managed to be. For every shining moment of insight—the constraints of gendered hobbies, a black working class woman informing Sherlock that he can never understand what it means to lack power—the film gives us twenty minutes worth of frustrating stupidity. Such as how Enola doesn't seem to conceive of escaping from boarding school until Tewksbury appears to rescue her. She then proceeds to get carried around in a basket for a few minutes before going out the window... which she could have done on her own at any point, locked doors or no. But it seems that narrative consistency isn't worth more than Enola (somehow) leaving a caricature of Mrs. Harris and Mycroft behind. The film is clearly trying to promote a "Rah, rah, go, women, go!" message, but fails to understand that having Enola find a way out of the school herself would be more emotionally fulfilling than having her send a generic 'You're mean' message after the two men in her life—Sherlock and Tewksbury—remind her that she can, in fact, take action.

Which brings me to my biggest criticism and what I would argue is the film's greatest flaw. Reviewers and fans alike are hailing Enola Holmes as a feminist masterpiece and yes, to a certain extent it is. Feminist, that is, not a masterpiece. (5) But it's a hollow feminism. A fantasy feminism. A simple, exaggerated feminism that came out of a Feminism 101 PowerPoint. To quote Sherlock, let's review the salient points:

A woman cannot be the star of her own film without having a male love interest, even if this goes against everything the original novel stood for.

A feminist woman cannot also be selfish. Instead she must have a selfless drive to change the world with bombs.

The best kind of women are those who reject femininity as much as they can. They will wear boy's clothes whenever possible and snub their nose at something as useless as embroidery. Any woman who enjoys such skills or desires to become lady-like just hasn't realized the sort of prison she's in yet.

The best women also embody other masculine traits, like being able to take down men twice their size. Passive women will titter behind their hands. Active women will kick you in the balls. If you really want to be a strong woman, learn how to throw a decent punch.

Women are, above all, superior to men.

Yes, yes, I joke about it just as much as the next woman, but seeing it played fairly straight was a bit of an uncomfortable experience, even more-so during a gender revolution where stories like this leave trans, nonbinary, and genderqueer viewers out of the ideological loop. Enola goes on and on about what a "useless boy" Tewksbury is (though of course she must still be attracted to him) and her mother's teachings are filled with lessons about not listening to men. As established, Mycroft—and Lestrade—are the simplistically evil men Enola must circumvent, whereas Sherlock exists for her to gain victory over: "How did your sister get there first?" Enola supposedly has a strength that Tewksbury lacks— he's just "foolish"—and she shouts out such cringe-worthy lines as, "You're a man when I tell you you're a man!"

I get the message, I really do. As a teenager I probably would have loved it, but now I have to ask: aren't we past the image of men-hating feminists? Granted, the film never goes quite that far, but it gets close. We’ve got one woman who is ready to start blowing things up to achieve equality and another who revels in looking down on the men in her life. That’s been the framing for years, that feminists are cruel, dangerous people and Tewksbury making heart-eyes at Enola doesn’t instantly fix the echoes of that. There's a certain amount of justification for both characterizations—we have reached points in history where peaceful protests are no longer enough and Tewksbury is indeed a fool at times—but that nuance is entirely lost among the film's overall message of "Women rule, men drool." It feels like there’s a smart film hidden somewhere between the grandmother murdering to keep the status quo and Enola’s mother bombing for change, that balance existing in Enola herself who does the most for women by protecting Tewkesbury... but Enola Holmes is too busy juggling all the different films it wants to be to really hit on that message. It certainly doesn’t have time to say anything worthwhile about the fight it’s using as a backdrop. Enola gasps that "Mycroft is right. You are dangerous" when she finds her mother's bombs, but does she ever grapple with whether she supports violence on a large scale in the name of creating a better world? Does she work through this sudden revelation that she agrees with Mycroft about something crucial? Of course not. Enola just hugs her mom, asks Sherlock not to go after her, and the film leaves it at that.

The takeaway is less one of empowerment and more, ironically, of restriction. You can fight, but only via bombs and punches. It's okay to be a woman, provided you don't like too many feminine things. You can save the day, so long as there's a man at your side poised to marry you in the future. I felt like I was watching a pre-2000s script where "equality" means embracing the idea that you're "not like other girls" so that men will finally take you seriously. Because then you don't really feel like a woman to them anymore, do you? You're a martial arts loving, trouser-wearing, loud and brilliant individual who just happens to have long hair. You’re unique and, therefore, worthy of attention, unlike all those other girls.

That's some women's experiences, but far from all, and crucially I don't think this is the woman that Springer wrote in her novel.

The Case of the Missing Marquess is a feminist book. It gives us a flawed, brave, intelligent woman who sets out to help people and achieves just that, mostly through her own strength, but also with some help from the young boy she befriends. Her brothers are privileged, misguided men who she nevertheless cares for deeply and her mother finally puts herself first, leaving Enola to go and live with the Romani people. Everyone in Springer's book feels human, the women especially. Enola gets to tremble her way through scary decisions while still remaining brave. Her mother gets to be selfish while still remaining loving. They're far more than just women blessed with extraordinary talents who will take what they want by force. Springer's women? They don't have that Hollywood glamour. They're pretty ordinary, actually, despite the surface quirks. They’re like us and thus they must make use of what tools they have in order to change their own situations as well as the world. The fact that they still succeed feels very feminist to me, far more-so than granting your character the ability to flip a man into the ground and calling it a day.

Know that I watched Enola Holmes with a friend over Netflix Party and the repeated comment from us both was, "I'd rather be watching The Great Mouse Detective." Enola Holmes is by no means a horrible film. It has beauty, comedy, and a whole lot of heart, but it could have been leagues better given its source material and the talent of its cast. It’s a film that tries to do too much without having a firm grasp of its own message and, as a result, becomes a film mostly about missed potential. Which leads me right back to where I began: The book is better. Go read the book.

Images

Enola Holmes

Mycroft Holmes

Sherlock Holmes

Enola and her Mother Doing Archery

Enola and her Mother Fighting

Tewkesbury and Enola

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ELDRIT is a 363 year old DEMISEXUAL, FEMALE, SHE/HER, here in Firebrand City. People say they look a lot like GAL GADOT. They are TENDER but can be TROUBLED. They are a DRAGON TRAITOR in Firebrand and they work as a DEMON COUNCIL ASSISTANT

I.

Sand dragons are small with serpent-like bodies; incredibly elusive they live their lives in the unforgiving desert in packs of 3 or 4. Excellent diggers they can go deep into the hard ground and find water, making oases of life sprout in even the harshest conditions. Eldrit grew up in a clan made up of her older brother and his mate, her older sister and herself since parents usually took off to start more families once hatchlings were self sufficient.

II.

It was a happy life but it wasn’t easy. Even for dragons, resources were difficult to come by, seasons were merciless and time moved slowly. They were defenders of the flora and fauna of their land and mostly they didn’t want their kind to go extinct. Eldrit and her thunder hid in razor sharp mountain ranges, caves and wherever they could, sometimes for years, months, or days. Their existence was nomadic and home was not a place but a feeling. Eldrit adored her siblings and constantly showed it, she was an affectionate and amicable reptile: she learned very fast, was easily pleased: they said that whoever ended as her mate was going to be lucky. Eldrit had no problem to wait for the one.

III.

The desert lands had always been territories full of magic and sand dragons were highly coveted specimens for those privileged enough to know about them. An energized enough sand dragon had the power to turn anything into diamond with their breath. Eldrit grew up distrustful of everyone and anything that wasn’t a member of her family, a paranoia that had been engraved in her genes for centuries and centuries.

IV.

It was Eldrit’s obsession with honey that set off the beginning of an endless nightmare. Her sister had been long gone to form a family of her own and the rest of the clan had been on the move to locate more sand dragons to maybe find a mate for the youngest. Eldrit wandered off to sample a honeybee hive. Careless, carefree, captured.

V.

She didn’t see them or smell them until it was too late. Their scent wasn’t that of regular humans. Some of them had fire like her. Some of them had water and air. Some of them turned into animals. They said words and made things happen. They put heavy chains and shackles around her legs, pinned down her wings, she couldn’t open her jaws to call for help, to defend herself as they took her far away from any kind of home she had ever known.

VI.

Eldrit was thrown into an ornate golden cage in a fancy marble palace where dozens of faces got to gawk at her every day. She got enough sustenance to exist but not enough to be able to break free from the chains. She had seen mountain lions and camels in local towns suffer similar fates as hers but never a dragon. Never a seemingly untouchable, magical being like her. She did not understand. Why couldn’t she free herself? Apparently the beings around her had magic too.

VII.

The sand dragon spent years and years captive as a glorified zoo animal for greedy Supers to parade and brag about. Every so often she was forced to showcase her powers and turn things into diamond. But inside, Eldrit was losing the battle, weakening, not made for life in captivity.

VIII.

That was when they noticed and started tampering with her heart. Showing her kindness in the form of presents; sweets, fruits, little trinkets, honey. A bigger enclosure. More sunlight. Lighter chains. Sand. A family of mice to break the isolation. Little by little, Eldrit was being tamed, her instincts fading to adapt to a new way to stay alive. However shameful it was, she wasn’t even aware.

IX.

Her first collar was so pretty, covered in diamonds that complimented the peach and gold hues of her scales. She barely felt when they locked it in, dazed by the wine that had been poured in her water. She still had a chain that tethered her to the marble floors of the palace at all times, but it was just the one. Just the one.

X.

She was the palace’s good girl, in their remote oasis with impenetrable walls. Eldrit had no place in politics, she was just a fancy pet, but she heard they stood somewhere between humans and some up and coming Council. And when the time came, it would be expected of her to protect those that had been so kind to her. And she did. Time and time again the sand dragon would be unleashed on the palace’s enemies. Like a good girl, Eldrit did as she was told.

XI.

And because of that, she got her biggest reward: an egg. The actual mating was nothing short of terrifying for Eldrit with a feral dragon that was brought to her enclosure one day and she never saw again once the deed was done. But her egg was beautiful; sparkling like the diamonds she could make with her breath. She was sure it was going to be a boy like her beloved older brother and she started referring to him as her ‘little prince’.

XII.

But her little prince wouldn’t hatch and Eldrit could feel the impatience growing around her. They wanted him to hatch just as much as she did. Like a protective mother, she would get aggressive whenever anyone would get close to her egg. And aggression and Eldrit were two things unknown to each other. So they took him away. For his protection, they said. He was too valuable. And Eldrit had to agree, even if she didn’t. She was his mother. But they started planting a new fear in her heart, that everybody wanted her egg. And the paranoia started chipping away at the sand dragon’s sanity.

XIII.

The once affable creature became highly weaponizable. Eldrit was blinded by terror, by their fear-mongering. They had to add more chains, because every noise meant somebody coming to steal her little prince, not even the people within the palace were safe. In reality, rebels knew their shameless way of life was coming to an end. They had threatened the Council for too long and they had to pay.

XIV.

The day the palace fell was the darkest of them all. Eldrit was released in all her furious glory telling her it was time to defend her egg, that they had finally breached the walls with the sole purpose of taking her little prince. But she was just one small sand dragon, brainwashed by decades of lying, of deceit, of deception. She was not prepared for an actual war, for an actual army, to be called a “rebel dragon” and be sent crashing through a marble tower, the entire structure collapsing under her.

XV.

Hearts are made out of muscle, so when they break they don’t make a sound. However, eggs do. Whichever one Eldrit heard was the loudest noise in the entire universe, it was deafening, it was maddening, it was infuriating, it was insufferable. The diamond looking pieces of eggshell were laying under a large marble column and Eldrit’s little prince was no more. And if he was no more, then nobody else had the right to be.

XVI.

With fury and rage born out of the purest grief, Eldrit broke off her enchanted chains and obliterated everything and everyone around her. It didn’t matter the affiliation, the species, the cause, she just annihilated with the power of a dragon much bigger and powerful than she was. Fire, ashes and smoke rained for hours as she bellowed and fought and destroyed, until she had nothing left.

XVII.

Waking up in a human body for the first time ever is a curse on its own. Waking up and remembering the destruction you caused, somehow worse. Waking up and looking at a piece of diamond eggshell tightly clenched in your human palm… Eldrit thought she was going to go insane again. Except now she couldn’t turn back into a dragon because she was wearing some different kind of collar, without diamonds. There were no chains. She was freezing. Her new body ached. She was on her way to some place called Firebrand. Still a slave. Now a traitor. Still alone. Without her little prince. To serve a new kind of sentence at a new kind of purgatory. Rightfully so, after everything she’s done.

XVIII.

Nothing about the city makes sense to the dragon now stuck in a human body. The air hurts her lungs, clothes hurt her skin, their food hurts her insides, it’s so cold all the time. She’s been in Firebrand for a month. She has a job that she’s somehow good at, her saving grace is her ability to learn things incredibly fast. She took to reading like hatchlings take to flying and there’s nothing inside a book that Eldrit doesn’t want to know; it’s an escape from the acidic grief that’s always consuming her and the reminder that she doesn’t want to be in a world without her little prince. What’s the point of trying to find a purpose when you don’t even want to have one anymore?

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Welcome To Grail Academy - Chapter Seventeen: Night Sounds Loud

“Hold you tongue, Clover!” A lanky man yelled and rose out of his chair. His burgundy pinstripe suit bore the insignia of the city of Calicem on his lapel in the form of an enamel pin, and below it hung four ribboned metals. Madehold glared at him from where she sat, her fingers drumming on the table that separated them. Ms.Divine stood behind her with a hand on her shoulder. They were in an office, an unfamiliar one that had a dome-shaped ceiling and windowless walls. It was lit like a hospital, harsh lights illuminating the alarmingly sanitary white floors. It was the office of Calicem’s governor, a portly old man with a pair of gold-rimmed glasses that reclined in his matching gold-plated chair. The tall man who yelled peered at the mayor, waiting for him to stand to his defense. The rest of those sitting at the table were the department heads of the school, Kismet, Pearl, Choi, and other old men in suits and ties who worked in the government.

“We lose more students each year that we don’t address the problem! They’re getting suspicious.”

“They’re children, Clover.” The golden-eyed man chortled, “So a few of them get upset. That’s what teenagers do!”

“They’re not just kids, you old dunce!” Madehold argued, continuing her speech before the man in the suit could yell at her again. “You are aware that the school is training highly skilled hunters, aren’t you?”

The tall man growled and gestured to a line of police officers in armored uniforms waiting by the door. “And we have our own highly skilled workforce. Our men are toiling night and day to uncover their whereabouts. You should mind your manners in front of the governor!”

Kismet murmured from the corner of his mouth to Miss Pearl, “What a twat.”

“Buh-I HEARD THAT!” He cawed out.

“You were supposed to,” Kismet hissed.

Madehold rubbed her knees impatiently with the palms of her hands, directing the conversation to the governor. “Voshkie, I can’t in good conscience sit and wait for you to cover this up while people gather pitchforks and torches against me. We have to go public.”

“In time.” The corpulent politician straightened his cufflinks, motioning for his slender counterpart to sit down. His paunchy hands combed through a thick mane of grey hair. Voshkie appeared much more relaxed than everyone else in the meeting, judging by the lazy posture in which he rested. “While I appreciate your passion for this project, I have to take the state of my voters into consideration. The city is fragile enough as it is, the last thing we want is to cause panic.”

“Sir. With all due respect, diplomacy hasn’t exactly been one of Calicem’s strong suits.”

“There is a vast difference between statesmanship and riots in the streets.” Voshkie shifted in his chair as he talked, and the other men in suits nodded along to every word he said. “The border is still protected, the Hedge Witches haven’t made a single public attack, and our people are safe. Let me do my job, and I’ll let you do yours.”

Being outdoors gave Yorick a much-needed breath of fresh air. The factory, though it was as large as the school, felt stuffy. There was a vast space of rolling fields behind the structure, overgrown with tall stalks of grass. He ran his hands over the blades of foliage during the time that he crossed the meadow. Sable stood a few yards in front of him. “Semblances are a core facet of our beings. They make us who we are.”

She brushed a stray hair out of her face, stepping back. “Your semblance is connected to your aura, like a defense mechanism. It’s an adaptation.”

“It feels more like a self-destruct button to me.”

“That’s not your fault, Yorick. It’s only nature!” Her bare feet crunched under the dirt and sticks scattered on the ground, keeping her head high. She called out to him, “Humans are still animals. We simply happen to be a bit smarter than dogs and birds.”

Yorick wrung his hands apprehensively. He didn’t understand the lesson she was trying to teach, but at least he was away from the factory. “Close your eyes. Focus. Your powers react to your stress and feelings, so dig deep. Think about a time when you felt raw emotion. Use those memories, center in on them. Clear your mind of everything else. You are living in those moments.” He did his best. Squeezing his eyes shut, Yorick balled his fists and thought back on his life. On everything.

His grandmother. His school. Esmerelda. Bernard. Nico. Rettah.

He couldn’t feel anything. “I-I can’t do it. It’s too much!” He opened his eyes and looked across at his mentor, who was slowly inching farther away. “Breathe, Yorick! Block it out!”, Sable shouted. He took a sharp gust of air into his lungs and held it. He was trying so hard, but deep down he knew that he didn’t want to face what would be left if he pushed everything away. He heard Sable’s voice ring out again, “You have to confront it, Yorick.” He let the air leave through his nostrils, shutting his eyes again.

His mom. His dad. Buck.

Sable watched him intensely. His hands were clenched and shaking, a tear rolled down his pale cheek, steam began to rise off his shoulders. “Good.” She remembered the newspaper clippings about Azora Navyn. A bull of a hunter who barreled through Remnant like a wildfire. She was headstrong, almost all the articles that were written about her were reporting the millions in property damage she costed cities when she was on missions. But she got the job done. Her notoriously explosive abilities placed her at the top of job lists, and landed her plenty of celebrity interviews on late-night talk shows. She even had her own superhero comic book series, The Blue Inferno. If Sable could get Yorick to control that power, she would be unstoppable.

“Now, find a point to anchor that stress to. Hold it in one place. Don’t release it.” Yorick pictured the energy flowing from his chest to every corner of his body, and he could feel the back of his throat get hotter. All was still, he managed to contain it. Sable smiled with mirth, clapping. “That’s great! Let it spread throughout you, but don’t let go of it.”

Yorick came to a realization. His semblance was still a major part of him, but it wasn’t who he was. He never hurt anybody. His power did. He was not his mistakes. Unexpectedly, his stomach gurgled. Lunch before training might have been a bad idea, He thought. He clamped his lips shut, but it couldn’t stop the raucous belch that burst from within. Following the burp, a stream of blue fire leapt out of his mouth like a flamethrower, scorching the portion of the meadow that he was facing. Sable dove out of the line of fire just in time, dropping down with her hands on top of her head. When she rose from the protection of the dry grass and gazed at the long patch of black earth next to her, she purred, “It’s a good start, at least.”

“You want me to WHAT!?” Nico hollered, pausing in his sparring match with Bernard mid-punch. They were training hand-to-hand in the tournament hall that was once again empty after Prom. His opponent swept his leg and knocked Nico’s feet out from under him, and he fell on his bottom with an “oof” sound.

“It’s the perfect opportunity. The exams are done off-campus, all you need to do is distract the professors while we sneak away to investigate Madehold’s office.” Esmerelda leaned over the railing on the bleachers, guarding her friend’s belongings while they fought. Nico grunted and patted the dust off his pants, and Bernard put his guard back up, elbows close to his chest. “Listen, you know I’m always down for delinquency and teenage mayhem.” Nico swung a high kick, but Bernard caught his foot in the air and stopped it from connecting, “Anarchy is like, my whole thing!” He arched his free hand in a right hook and slugged Bernard in the shoulder, though Bernard didn’t show any sign that he was hurt by it, “But I can’t afford to flunk this test. It’s my last chance at a passing grade!” Bernard turned his wrist and flipped Nico over, sending him falling to the floor a second time.

Esmerelda bit her lip, displeased. “He’s your teammate too, darling.” Both boys twitched at that, and Bernard helped Nico up before he reproached, “So was Yale.”

“Yo. Dude.” Nico took his partner by the forearm and gave him a concerned look, using the worry in his eyes as a warning. The flood lights flickered, making the circular shape from the skylight above quiver. “This is different.” Esmerelda’s palms squeaked against the cold metal railing, jumping over the bar into the arena. She carried herself like an animal on the prowl, and Bernard puffed his chest out when she walked up to him. “This time we know the who, why, and how.”

“So you’ve given up on Yale, then?” He folded his arms as she got closer, pointing her chin up to him as if it were a dagger. Nico attempted to interject, “Don’t talk about her like that”, but it was no use. Esmerelda and Bernard were locked on one another.

“That’s not what I meant.”

“Then what did you mean?”

“I just,” Esmerelda threw her hands up in exasperation, “Whatever! You don’t want to help, fine. I’ll do it myself.” She turned tail and left in a huff, flipping the collar on her coat up to shield her face from the wind outside as she crossed the quad back to their dorm.

“Bernie?” Nico spotted the other boy leaving in the opposite direction, gathering his things and throwing his bag over his shoulder. He was torn, glancing from Bernard to Esmerelda on their ways out. “Uhhhhh, crap crap crap, uh….” Frantic, he finally made a choice and snatched his jacket.

“Esme, wait up!” He ran after her, pausing to pant once he caught up to her outside. She seemed less than happy about the situation. “What, are you going to scold me as well?” She spoke through gritted teeth, walking so briskly that Nico had to jog to keep up with her.

“No, enough with the tantrum! What is going on with you lately?”

“My partner was abducted by terrorists, and nobody is doing anything about it. That’s what is going on.”

“You think we don’t miss Yorick too?” Nico craned his neck to make eye contact with Esmerelda, but she refused to look at him. He stepped in front of her and started to walk backwards, making himself an unavoidable line of sight. “You think Bernard isn’t worried sick about him? You think I bruised my ribs for FUN?” He did kind of enjoy the fight at the hotel, but that wasn’t the point. “We all want him back. And we’ll find him! But we can’t get anywhere if you’re throwing people to the beowolves left and right.”

“I’m not-”

“You’re our leader! We need an actual plan.”

“I do have a plan!”

“That was not a plan, babe.” He placed a hand on her shoulder. “That was a recipe for disaster.” Esmerelda took a minute to consider all the possible ways her idea could go awry.

“Okay….maybe you’re right.”

“I know I am~”

“But I won’t apologize to Bernard. In fact, he should be the one saying sorry.”

“Oh, come on!” Nico punched the air in frustration, complaining “Why do I have to babysit you guys!? I’m supposed to be the irresponsible one!”

She laughed quietly, finding some joy in Nico’s protests.

“I’m the Devilishly handsome bad boy! The out-of-control party animal!”

“That’s debatable, darling.”

“I don’t wear a helmet when I ride my bike! I sit in chairs backwards! I eat ice cream even though I’m Lactose intolerant! I leave my shoes untied! I stole chapstick once! I brush my teeth and drink orange juice after I’m done! I’m crazy!”

Esmerelda couldn’t help but smile, knowing that her friend had done his job in cheering her up. “Alright, alright. I’ll talk to him.” As they strolled to their dorm, crossing the shortcut on the grassy quad, she sighed and saw the small puff of fog that was her breath swirl in the cold night air. “....We shouldn’t have brought up Yale like that. I’m sorry.” He smiled at her to show he appreciated the apology. The act of silently forgiving her warmed Esmerelda’s heart.

With Nico and Esmerelda cooling off in their room, Bernard rummaged through his backpack for his scroll. 3 missed calls from his mother. That couldn’t be good. He tapped her icon and waited for the ringing to cease. “Mamá ¿Estás bien?”

Long after all the students went to bed, albeit somewhat earlier than usual because of the new curfew, the headmaster slunk through the empty hallways of the school. She was tired, she had been working late into the night. Madehold snuck over the quad and stood at the base of the menacing clocktower. It loomed over her and the academy like the shadow of a great beast, its grey stones and bricks serving as a grim reminder of their mortality. She pulled a off a key tied with a ribbon around her neck and inserted it into the old wooden door. The sounds that the structure made as she moved through it, the aches and moans of the door’s hinges and the rickety stairs, echoed inside the tower. A low, green glow shone through the cracks and holes between its stone walls, and although nobody noticed it, the hands on the face of the clock slowly stopped ticking.

#rwby#rwby oc#grail academy#welcome to grail academy#ebny#team ebny#fanfiction#fanfic#rwby fanficton#rwby fanfic#oc fanfiction#oc fanfic#rwby oc fanfiction#rwby oc fanfic#punk#esmerelda#bernard#nico#yorick

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

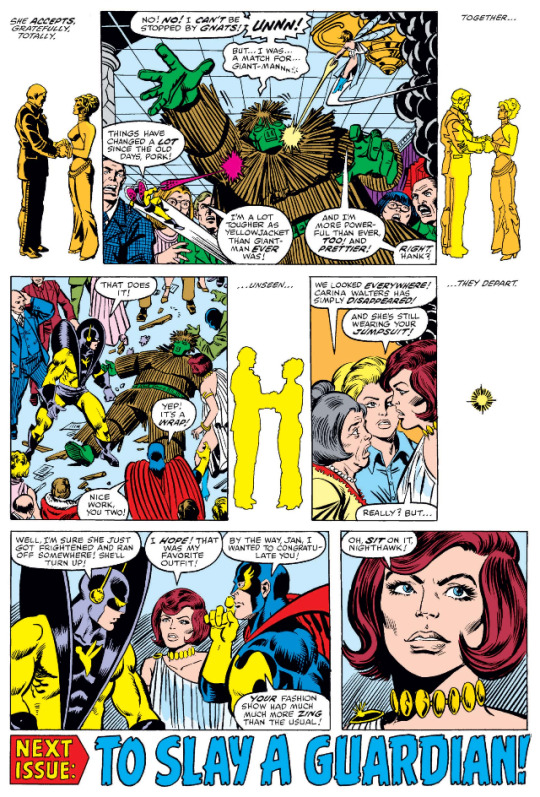

Film Production Log #3

A frame from “The Death Of A Home″.

What year is this?

It’s been a long time coming that I finally got around to writing another one of these things. It’s three months into 2019 already and I hardly even noticed, made a rude awakening when I looked to the calendar to see that it went from 28 back to 1. With all that, it hit me that I hardly wrote about the progression of any of my current film projects in that period of time. I thought I had a rough idea of how the passage of time worked, as it turns out I know as little about a concept as abstract as time as I do about every other thing in life that defies explanation. There’s a reason why I simultaneously dread everything and nothing after all. I’ve written through many variants of this first paragraph beforehand, each draft starting off with the same “long time coming” comment, which gained further relevancy with each rewrite. Let’s go and cut this ongoing habit before it goes beyond simple procrastination into flat out absurdity.

A frame from “The Death Of A Home″.

Like mentioned with the second production log, we spent most of the December of 2018 haphazardly preparing a forced move that we had to undergo with the sudden gentrification of our apartment at the time. This wasn’t the first time I faced the systematic Kafkaesque horror of gentrification. I was pissed, to say the least, and I did the only thing I could do, I documented it. With The Death Of A Home as it is currently, all the footage from the move itself has been compiled and made into a rough cut, adding up to my first proper feature length film at an hour and 12 minutes. The film is comprised of long shots, with scenes ranging from a crew of biohazard workers cleaning the basement of a black mold infestation that was never reported to the tenants to a sequence where long kept hand-painted furniture is forcibly discarded (tossed down a staircase into the back lot to lead to a rain of multicolored paint shards). The whole film will also be accompanied by a harsh noise soundtrack, I mostly have Merzbow stuff playing throughout as a placeholder. I’ll be shooting on the side some abstract visual sequences for the documentary, communicating certain details of our story that weren’t captured on film. I have a lot of ideas brewing for the mixed media techniques I could use for creating these images in a live action format, specifically ones that return to the sort of trash bag special effects that I used in my prior film concerning the subject of gentrification, Weightless Bird In A Falling Cage.

Setting foot in the new apartment, the first thing we came to notice was the absolutely vacant house next to us. The building was completely abandoned with electricity still hooked up, looked like no one set foot there in years. Having it face the bedroom every day, with our constant visual subjection and time to contemplate we came to the conclusion that something was gonna happen to the building at some point. It was clearly the middle child to an estate that left it to rot. Just in time for when we wrapped up unboxing everything, the building caught fire. At first I didn’t pay much mind to the sound of sirens driving through (it’s an Atlanta custom). It eventually hit me that something wasn’t quite right when I looked to one of the windows to see bright red, Suspiria technicolor light shining through.

A frame from “Burning Fragments: Mode 3 - Winter 2019″.

Did I go out to have a look? Of course, so did the rest of the neighborhood. Made an interesting meet your neighbor type of gathering, to say the least. I also brought my camera with me, and I came back with a metaphorical stack of raw footage along with a slow-cooked pair of lungs, the film is more important though. From that raw footage, I got the visual edit for the short Burning Fragments, a part of my seasonal “Mode” series that was first kicked off by Hard Drive and continued by my currently unreleased Factory Dreams. Burning Fragments is a montage of morbidly humbling sequences, from a roof visibly caving in through the smoking windows to medical staff cautiously carting out a stretcher, prepared for the worst case scenario. No one came out injured luckily, though I don’t mention that in the film (to keep up the haunting atmosphere). Power was cut to the building, the fire was put out and the street stunk of smoke for the next month. I thought it smelt like a smoked rib, one neighbor of ours said it smelt exactly like pot smoke.

A frame from “Factory Dreams: Mode 2 - Fall 2018″.

Right around there was where we thought the story would end, but several days later the building went back up again. This time around I went to one of the firefighters to ask what started the fire in the first place. As it turned out this second eruption was from the ongoing work of someone who had a great disdain to a singular sofa in the abandoned building. The first fire was started off by the arsonist setting this certain sofa aflame, and the guy returned to the scene of the crime to incinerate it for good. Our friendly neighborhood sofa arsonist is still on the run to this day.

Going into rapid-fire mode, some other noteworthy moments of the year so far include: OS updating, film editor street fighting, more OS updating, cool experimental film screenings (as seen in my documentary Moonlight Tunnel), one last OS update for good measure and discovering the new OS is as thought out as a tumble down a staircase.

Kafka’s Supermarket sorta ended up bunched between everything, seeing one quick, sporadic development at a time. The issue with actors still stands, gotta track down some people for the film to act in those pesky performed segments. It all goes smoothly until you’ve gotta spend the time and physical resources of other living, fleshy beings into your freaky unscripted cinematic daydreams.

Around the end of February, I collaborated with local collage artists Steven and Cassi Cline to write the dialogue for the film, collage literature style. We took several different approaches when it came to fully fleshing things out, some were done as experimental writing games while others were the more familiar cut n paste technique. The script took a wide variety of resources, including the FBI documents printed from the internet archive, the prologue of a Georges Bataille philosophical text and a book on nuclear weapons. I was largely the supplier when it came to the process, while I do visual collage stuff often I’m less of a writer (both letter by letter and cut up source by cut up source).

Readings of the literary collages will be interspersed throughout the film with an announcer who seems completely detached from the surreal nature of the scenes he describes. Burroughs’ approach for writing Naked Lunch aside, the primary source of inspiration for this detail comes from my memories of a radio clock that we had during my childhood. I would tune through channels with it searching for classical music, but most often I’d find news stations. Not knowing anything about politics at the time (being 5 to 6 years old and all), the nature of what was being discussed was completely alien to me. With how Kafka’s Supermarket is focused on the nightmarish distortion of everyday life in capitalist America, I felt it was necessary to recreate the atmosphere of those broadcasts that confused me all those many years ago.

One detail that left the production hung for a significant amount of time, as minuscule as it may seem, was the masks the actors would be wearing. The visual style of Kafka’s Supermarket was adapted from my 2017 zine What Brought Me To This Point, an experiment in nihilistic writing that focuses on the mental state of a man with prosopagnosia and a non-specified mental illness. My general understanding of prosopagnosia at the time was admittedly limited, I had just heard of a condition where someone couldn’t recognize faces and something about the idea creatively resonated. From this, all the characters were designed with the same basic facial template, prioritizing the bare essentials of the human face with an emphasis on the uncanny. Kafka’s Supermarket further branches out this aesthetic in using it as a wider embodiment of the lack of individual personality in a capitalist state, where everything is selling to a set of categorized markets that represent the general populace.

A frame from “Kafka’s Supermarket”.

The thing is, human heads aren’t structured like these figures I was drawing.

I spent an absurdly long time contemplating how exactly I could recreate the look of these characters not only with a budget but with a budget without having it look too “store-bought” in a way. The main catch was I was going by realism and not surrealism. At that point, I briefly lost sight of what exactly I was doing. We all make mistakes. I brooded on how I could convincingly recreate an abstract illustration. It took until I started reading the screenplays of Kōbō Abe that sense hit me again when I questioned how it would be done in a theater production. That was when I remember that I’m making a non-narrative experimental film, not something like a superhero fan film where a certain level of suspension of disbelief is expected. Since then I plotted out an alternative that’s simultaneously more affordable than anything I was theorizing beforehand while also being more surreal and true to the theories and atmosphere behind Kafka’s Supermarket (and even it’s predecessor, What Brought Me To This Point). Since then I’ve found myself further experimenting with the fusion of film and theater, specifically the use of minimal props and images to convey a greater concept.

I’ll be reposting cast calls for actors through the next several days, hoping for the best while I also simultaneously pester a nearby grocery store for permission to shoot a short sequence on their property. Productions like this are the ones that leave me realizing the oxymoronic nature in pursuing capitalist chains about the production of strictly anti-capitalist cinematic rhetoric.

A frame from “Empire Of Madness: A Wilderness Within Hell 2″.

While juggling well more than a handful of personal projects (all the films mentioned earlier, a second chapter of Iron Logs and a harsh noise album experiment), I also convinced myself that I can get back into animation again. I was publicly tiptoeing around the idea of a second Wilderness Within Hell film for a while, and now it seems that it will likely be a thing with Empire Of Madness. It’s not really a direct sequel as much as it is a continuation of the style that was first started with Madhouse Mitchel.

Set in the same age of industrial totalitarian inferno as Madhouse Mitchel, Empire Of Madness follows the life of Prometheus after his divine punishment for giving mankind knowledge. Having finally passed physical torture in the complete separation of his physical body, Prometheus wanders the Earth as an anomalous figure that assembles itself in a seemingly manufactured, mechanical nature. With pieces of his blood and flesh inherited by every man and woman with his given wisdom, he is inconsequently responsible for a curse put on all of humanity that destines man to collapse in paranoia and violence. Prometheus is shunned by everyone who crosses his path, seeing him as a sickly demon. Prometheus comes to realize that aside from his physical torture, the true act of divine punishment enacted on him will be the experience of having his own creation slowly destroy itself while it collectively tries to kill him.

A frame from “Empire Of Madness: A Wilderness Within Hell 2″.

I’m simultaneously writing the film’s screenplay while I draw certain visual intensive scenes. Like I mentioned I’m still a bit rough around the edges with writing, so for this phase of production, I’ll actively study Kōbō Abe’s scripts and also the screenplays to an Akira Kurosawa film and Battleship Potemkin. I’ll still in a way aim more to minimalism with how certain things play out, with this series’ influences in Japanese guro art it’s more inclined to create a certain nightmarish atmosphere above all else. While Madhouse was largely anti-systemic rage, this film leans more to bleak existentialism. Bits of the soundtrack are already recorded, the main theme can currently be heard here.

That’s about all I have to write for now. Now to wait another four months until I post anything text based on here again.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

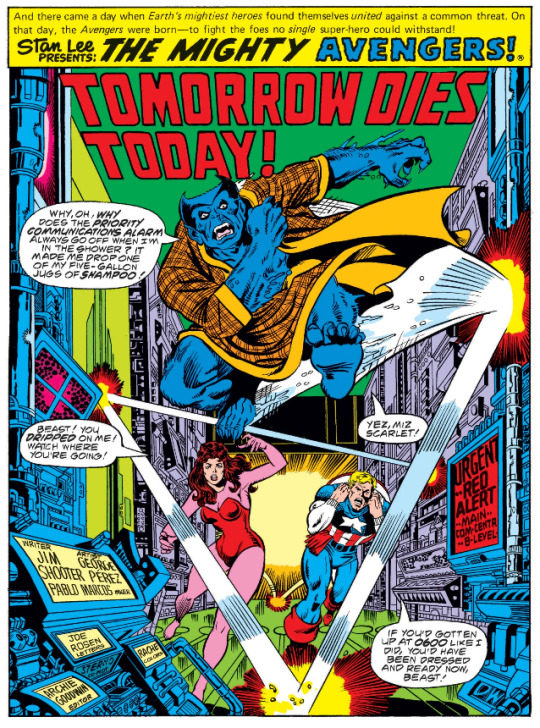

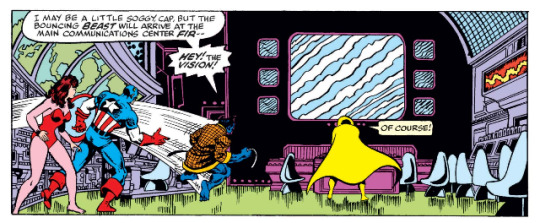

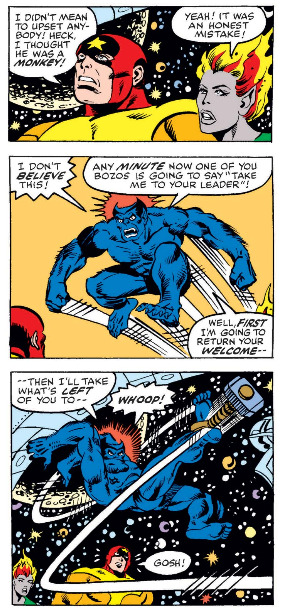

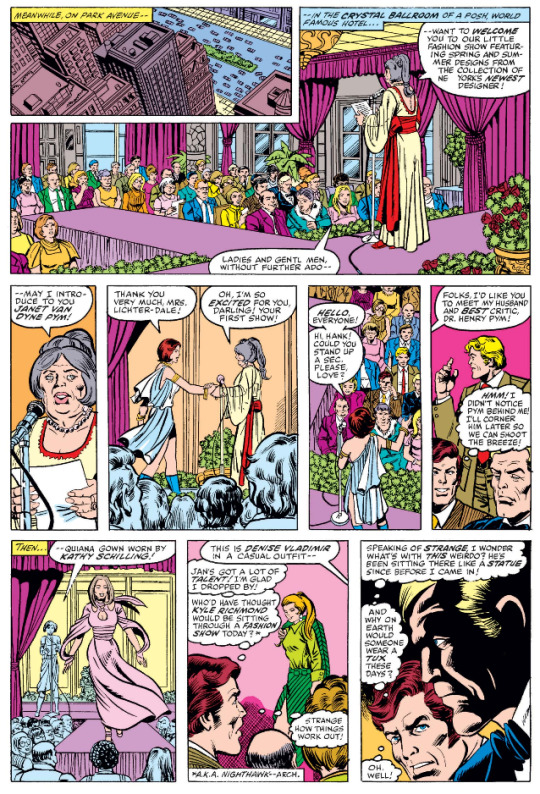

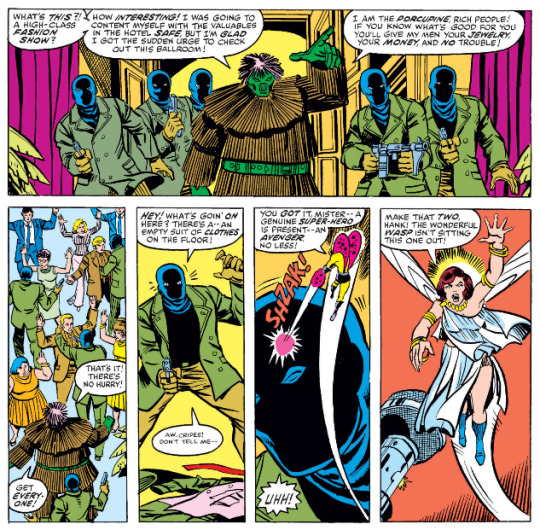

Essential Avengers: Avengers #167: Tomorrow Dies Today!

January, 1978

Oh hey the Guardians of the Galaxy! Not the ones more known these days and never at the same level of popularity but an interesting bunch just the same!

I’ve been actually thinking of going and reading some of the original team original run.

On this cover, Beast punches a guy in the face and the rest of the Avengers are like hey slow your roll this is a crossover not a hero vs hero event.

Anyway, we start off killing tomorrow today with a priority communications alarm interrupting him from his shower.

You’d think that since its a communications alarm and not necessarily an emergency, he could continue showering and let someone else take the call and if it is an emergency then someone can knock on the door and let him know.

Like, I understand that with the stuff the Avengers deal with its good to stay on your toes but Beast is completely covered in hair. When he starts a shower, its a long, inevitable process that should be seen to until the end.

Otherwise he’s going to drip everywhere and probably smell like dog.

He’s not even the only one who is not ready. Scarlet Witch is half dressed.

And Steve “I probably go on a ten mile run every morning for fun” Rogers criticizes Beast for not getting up to shower at 0600.

Beast, Cap, and Scarlet Witch arrive at the communications center to find Vision already there.

Also, why do they have so many chairs in here? This is more chairs than they have in their living room.

A lot of the Avengers equipment is a mystery to me. They seem like they have a lot of the typical superhero headquarters monitoring equipment but also they so often wait for problems to happen on the news before they notice them.

Anyway, it actually is an emergency so Beast would have had to interrupt his shower anyway.

Nick Fury is on the horn and he tells them to turn on the feed from the Avengers’ monitoring satellite because of course they have one of those and need to watch the news anyway.

Per Fury’s request, they focus the Avengers satellite on the SHIELD space station. Weirdly they can’t see any stars behind the station. Just an endless wall of white.

Beast zooms out and-

AHHHHHHHHHH UNICRON HAS COME AT LAST TO DEVOUR OUR WORLD!

Galactus is going to be miffed.

Except no. This looks like a double Unicron. Which is possibly twice as bad.

Apparently this giant structure popped out of nowhere and its orbit is going to smash the SHIELD station all over it in a couple hours.

So the Avengers assemble to finish getting dressed and also to go check out a mysterious huge space thing.

Like I said, this is the huge space thing portion of their lives.

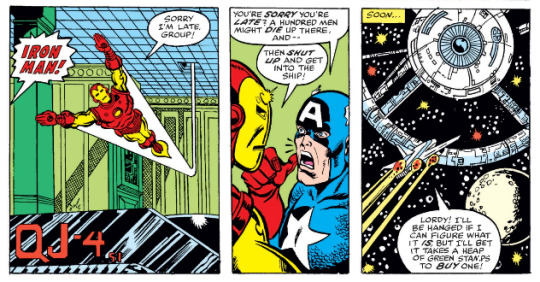

On the station, playboy industrialist Tony Stark claims he has urgent business on Earth.

Nick Fury is like no shit of course I’m not letting you get smashed with the rest of us you dink, get on a shuttle and go.

Fun fact: the SHIELD space station is where Steven Lang’s Project: Armageddon set up shop. And coming up to space to stop him is what led to Jean Grey becoming the Phoenix.

Secretly, Tony Stark has to get back to Earth so he can change into Iron Man and lead the Avengers back up here.

Double lives are hard.

Meanwhile, Thor and Wonder Man are enjoying some bonding time in a diner.

Thor confesses that some mysterious force has been transporting him back to Earth every time the Avengers need his help. Which has to be every couple of days. Its almost as if he’s being displaced through time.

Wonder Man goes wow cool uh I’ll be no help figuring that out but as long as we’re here maybe you can give me some advice.

Wonder Man: “You see... sometimes I -- I feel as though I’m not man enough to be a super man!”

-interrupting Avengers beeper says no time for feels, time for punches-

So Wonder Man and Thor fly back to Avengers’ Mansion.

But they have to wait because Iron Man still hasn’t joined them.

And when he does show up, Cap goes off on him.

Iron Man: “Sorry I’m late, group!”

Captain America: “You’re sorry you’re late? A hundred men might die up there, and --”

Iron Man: “Then shut up and get into the ship!”

Also, new Quinjet! Space Quinjet!

Only minutes later, the Avengers have arrived on the SHIELD station. Which is... really impressive.

But since it took them so long (because of Iron Man), there’s no time left for anything fancy. The big double Unicron is only half a mile away.

Now the only option is to spacesuit up (except for Thor and Vision), rocket across to an opening that the station’s brand new Stark computer pinpointed, and find a way to redirect or destroy the giant space thing in... fifteen minutes.

Geez.

I’m pretty sure fifteen minutes wouldn’t even get you from one side to the other of that thing.

But the Avengers do rocket across. And the opening that the computer found was an airlock. And interestingly, they find that the atmosphere inside the station is breathable and even chemically perfect for humans!

Now that is interesting. Does that mean that this is a human construction?

Not necessarily. The Avengers never had trouble breathing on Skrull ships or Thanos’ giant H, or even on the Kree homeworld.

I mean maybe the chemically perfect line signifies that even beyond everyone in space breathing the same thing except that one group of aliens that kidnapped that lung expert, that this construct has a human friendly atmosphere.

Iron Man weighs in. Atmosphere or not, whether the occupants are humanoid or not, this construct is far beyond the capabilities of any Earthly power.

Boring and also a waste of time says Cap.

And he steps up and takes charge, giving everyone a directive.

They should split up to cover more ground.

And while that would usually be a bad idea on a space station that appeared out of nowhere and could contain any number of alien nasties, the simple fact is that they have a vanishingly small amount of time.

Splitting up is the only way to cover any significant amount of territory.

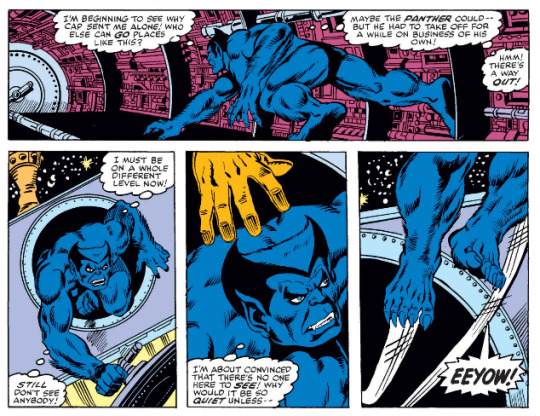

So Vision and Wanda are one team. Wonder Man and Cap another. Thor and Iron Man another. And Beast is on his own because they have an odd number of people.

Although Beast wonders why he’s the one without a partner. He used mouthwash that morning!

Meanwhile, while Iron Man dismisses Thor’s concern that Iron Man might be troubled over Cap taking charge, in reality he is troubled.

Iron Man: “On the other hand it’s no secret what Cap thinks of my leadership! I suspect his resentment is growing and getting personal! With the stakes the team is playing for, that kind of dissension can lead to sudden death!”

Maybe its time to consider whether someone without their own book should lead the team then.

Meanwhile elsewhere, Beast is climbing through the air ducts or perhaps Jefferies tubes. And actually Cap had a point splitting him off like this. Beast is the only one who has the agility to crawl through tubes like this.

Good call, Cap!

But when he pokes his head out of the Jefferies air duct, someone grabs him and yanks him out like a radish.

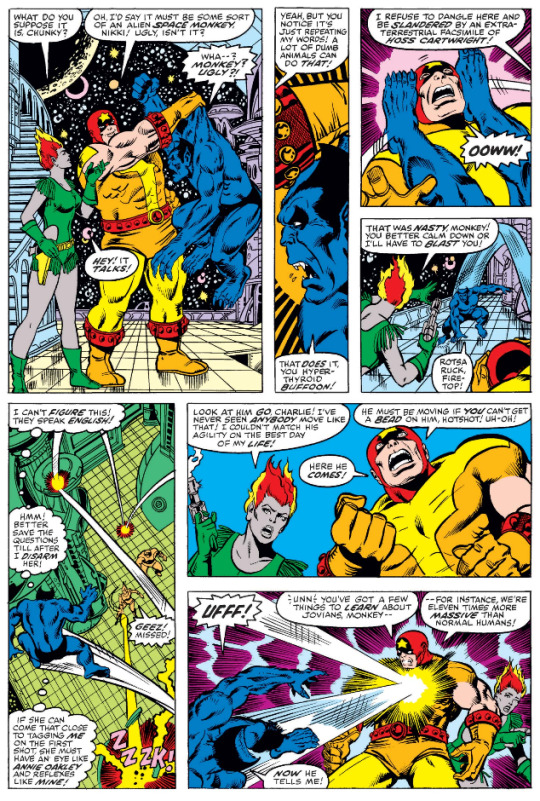

Hey, its Charlie-27! From a race engineered to live on Jupiter, he’s about 11 times stronger and denser than a normal human being.

Also, its Nikki Gold! Raised on Mercury, she has high resistance to heat and most radiation and also HER HAIR IS FIRE.

And the thing is, they don’t think Beast is an enemy. They think he’s some kind of ugly alien space monkey that can also parrot words like a raven.

Beast refuses to put up with that sitting down dangling by his scruff so he kicks Charlie-27 in the face and starts bouncing all over the room.

Nikki tries to shoot Beast because, hey, he’s a rude monkey. But he’s bouncing so fast she can’t get a bead on him despite having aim adjacent to Annie Oakley’s.

But then Beast tries to tackle Charlie-27 and just bounces off. Because dang. Remember? Eleven times more massive than a normal person? Its rather like Beast just tried to jump kick a brick wall.

Before possibly breaking a toe kicking a guy built like a brick house, Beast also muses on the weirdery of the two of them speaking English.

Which again isn’t so odd. Universal translators exist. And a lot of aliens speak English.

But all these things like the atmosphere and aliens speaking English? This time they signify something other than narrative convenience.

Nikki jumps to confront the dazed Beast but with a RRRAK! a coherent light burst separates the two.

The rest of the Guardians have shown up, specifically Starhawk who tells Charlie-27 and Nikki to stand down.

Starhawk: “This fighting must cease! I sense that he is not evil! Accept the word of one who knows!”

Lets run up the line.