#social contract

Text

🎨 Valerie Jaudon

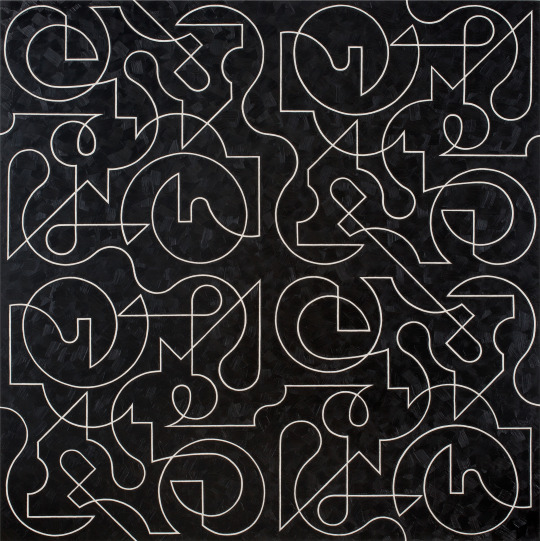

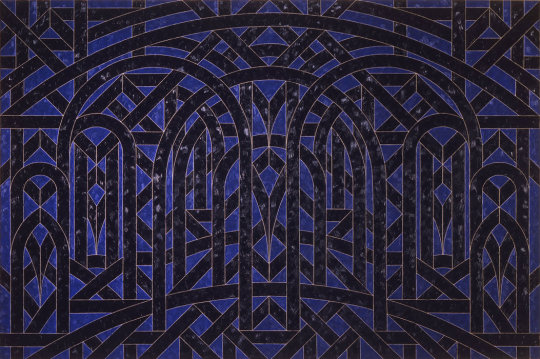

Valerie Jaudon (b. 1945) - Palmyra - 1982 - 84 x 114 in. (213.36 x 289.56 cm) - oil on canvas

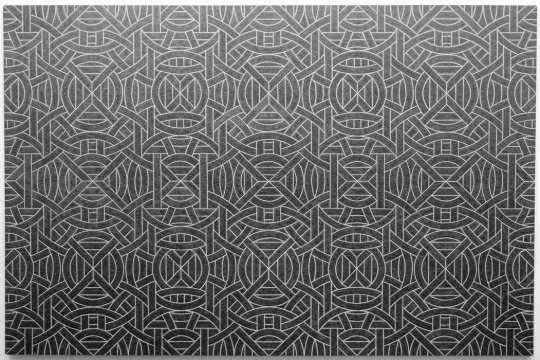

Valerie Jaudon - Big Springs - 1980

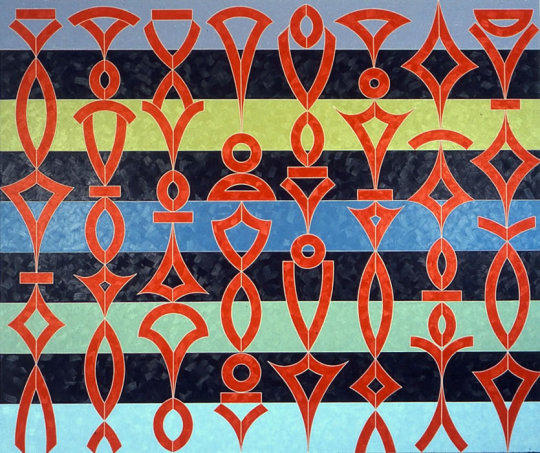

Valerie Jaudon - Sebastapol - 1982

Valerie Jaudon - Quadrille - 2017

Valerie Jaudon - Passage - 2018

Valerie Jaudon - Egremont - 1985

Valerie Jaudon - Manetta - 1984

Arcola, 1982, 81 x 120", oil on canvas

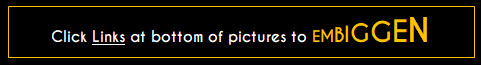

Saraband, 2014, 48 x 48”, oil on linen

Avalon, 1976, 72 x 108", oil & aluminum pigment on canvas

Ballets Russes - 1993, 90 x 108", oil on canvas

Social Contract, 1992, 90 x 90", oil on canvas

Meridian, 1980, 87 x 121", oil & metallic pigment on canvas

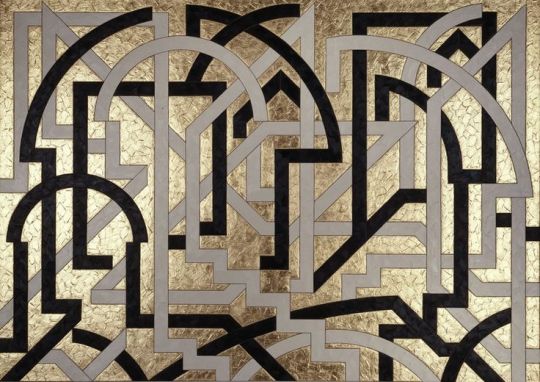

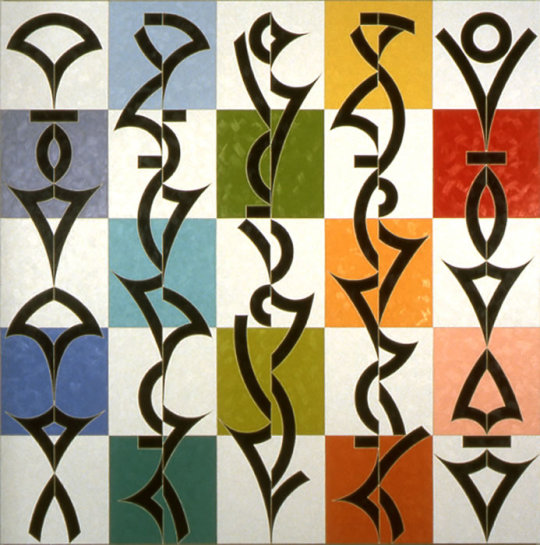

Valerie Jaudon is an original member of the Pattern and Decoration movement. Her art has been written about consistently in books, journals, magazines, newspapers, and catalogs. She is the co-author, with Joyce Kozloff, of the widely anthologized Art Hysterical Notions of Progress and Culture (1978), in which she and Kozloff explained how they thought sexist and racist assumptions underlaid Western art history discourse. They reasserted the value of ornamentation and aesthetic beauty - qualities assigned to the feminine sphere.

Valerie Jaudon

#Valerie Jaudon#art#design#manetta#egremont#Jaudon#quadrille#passage#sebastapol#palmyra#big springs#pattern & decoration#Art Hysterical Notions of Progress and Culture#ballets russes#social contract#sarabande#arcola#meridian

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Hobbes and Locke both—for all their differences—begin by conceiving natural humans not as parts of wholes but as wholes apart. We are by nature "free and independent," naturally ungoverned and even nonrelational. As Bertrand de Jouvenel quipped about social contractarianism, it was a philosophy conceived by "childless men who must have forgotten their own childhood." Liberty is a condition of complete absence of government and law, in which "all is right"—that is, everything that can be willed by an individual can be done. Even if this condition is shown to be untenable, the definition of natural liberty posited in the "state of nature" becomes a regulative ideal—liberty is ideally the agent’s ability to do whatever he likes.’

— Patrick J. Deneen: Why Liberalism Failed

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

CIVANTICISM

Softhearted Compassion | Hardnosed Coherence

https://www.civanticism.com/

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two notions of liberty revisited—or how to disentangle Liberty and Slavery

The modern liberal concept of liberty has roots in Roman law and the Roman understanding of the master and the slave. We need to unpick that heritage to imagine a better basis for our political aspirations.

David Graeber

May 19, 2013

Our idea of human freedom, with its origins in Roman law, is permeated through and through with the institution of slavery. But its links to slavery twisted the meaning of “freedom” from an empowering notion of what it is to live with dignity in a society of equals to one of mastery and control. Understanding the history of the concept should help us to regain the first and fight the second of those notions.

The meaning of the Roman word libertas changed dramatically over time. To be “free” meant, first and foremost, not to be a slave. Since slavery means above all else the annihilation of social ties and the ability to form them, freedom meant the capacity to make and maintain moral commitments to others. The English word “free,” for instance, is derived from a German root meaning “friend,” since to be free meant to be able to make friends, to keep promises, to live within a community of equals. Freed slaves in Rome became citizens—and this makes complete sense because to be free, by definition, meant to be anchored in a civic community, with all the rights and responsibilities that this entailed.

By the second century AD, however, this had begun to change. The jurists gradually redefined libertas until it became almost indistinguishable from the power of the master. It was the right to do absolutely anything, with the exception, again, of all those things one could not do. In the Digest, the basic text of Roman law, the definitions of freedom and slavery appear back to back:

Freedom is the natural faculty to do whatever one wishes that is not prevented by force or law. Slavery is an institution according to the law of nations whereby one person becomes private property (dominium) of another, contrary to nature.

Medieval commentators immediately noticed the problem here. But wouldn’t this mean that everyone is free? After all, even slaves are free to do absolutely anything they’re actually permitted to do. To say a slave is free (except insofar as he isn’t) is a bit like saying the earth is square (except insofar as it is round), or that the sun is blue (except insofar as it is yellow), or, again, that we have an absolute right to do anything we wish with our chainsaw (except those things that we can’t).

In fact, the definition introduces all sorts of complications. If freedom is natural, then surely slavery is unnatural, but if freedom and slavery are just matters of degree, then, logically, would not all restrictions on freedom be to some degree unnatural? Would not that imply that society, social rules, in fact even property rights, are unnatural as well? This is precisely what many Roman jurists did conclude—that is, when they did venture to comment on such abstract matters, which was only rarely. Originally, human beings lived in a state of nature where all things were held in common; it was war that first divided up the world, and the resultant “law of nations,” the common usages of mankind that regulate such matters as conquest, slavery, treaties, and borders, that was first responsible for inequalities of property as well.

This in turn meant that there was no intrinsic difference between private property and political power—at least, insofar as that power was based in violence. Dominium, a word derived from dominus, meaning “master,” or “slave-owner,” is the term in Roman law that means absolute private property. It is the sort of property-right that today has been theorised as the model case of a “negative freedom”—that which you can do with no interference from anyone else.

As time went on, Roman emperors also began claiming something like dominium, insisting that within their dominions, they had absolute freedom—in fact, that they were not bound by laws. At the same time, Roman society shifted from a republic of slave-holders to arrangements that increasingly resembled later feudal Europe, with magnates on their great estates surrounded by dependent peasants, debt servants, and an endless variety of slaves—with whom they could largely do as they pleased. The barbarian invasions that overthrew the empire merely formalized the situation, largely eliminating chattel slavery, but at the same time introducing the notion that the noble classes were descendants of the Germanic conquerors, and that the common people were inherently subservient.

Still, even in this new Medieval world, the old Roman concept of freedom remained. Freedom was simply power. When Medieval political theorists spoke of “liberty,” they were normally referring to a lord’s right to do whatever he wanted within his own domains—his dominium. This was, again, usually assumed to be not something originally established by agreement, but a mere fact of conquest: one famous English legend holds that when, around 1290, King Edward I asked his lords to produce documents to demonstrate by what right they held their franchises (or “liberties”), the Earl Warenne presented the king only with his rusty is sword. Like Roman dominium, it was less a right than a power, and a power exercised first and foremost over people—which is why in the Middle Ages it was common to speak of the “liberty of the gallows,” meaning a lord’s right to maintain his own private place of execution.

By the time Roman law began to be recovered and modernized in the twelfth century, the term dominium posed a particular problem, since, in ordinary church Latin of the time, it had come to be used equally for “lordship” and “private property.” Medieval jurists spent a great deal of time and argument establishing whether there was indeed a difference between the two. It was a particularly thorny problem because, if property rights really were, as the Digest insisted, a form of absolute power, it was very difficult to see how anyone could have it but a king—or even, for certain jurists, God.

This genealogy of liberty allows us to understand precisely how Liberals like Adam Smith were able to imagine the world the way they did. This is a tradition that assumes that liberty is essentially the right to do what one likes with one’s own property. In fact, not only does it make property a right, it treats rights themselves as a form of property. In a way, this is the greatest paradox of all. We are so used to the idea of “having” rights—that rights are something one can possess—that we rarely think about what this might actually mean. In fact (as Medieval jurists were well aware), one man’s right is simply another’s obligation. My right to free speech is others’ obligation not to punish me for speaking; my right to a trial by a jury of my peers is the responsibility of the government to maintain a system of jury duty. The problem is just the same as it was with property rights: when we are talking about obligations owed by everyone in the entire world, it’s difficult to think about it that way. It’s much easier to speak of “having” rights and freedoms. Still, if freedom is basically our right to own things, or to treat things as if we own them, then what would it mean to “own” a freedom—wouldn’t it have to mean that our right to own property is itself a form of property? That does seem unnecessarily convoluted. What possible reason would one have to want to define it this way?

Historically, there is a simple—if somewhat disturbing—answer to this. Those who have argued that we are the natural owners of our rights and liberties have been mainly interested in asserting that we should be free to give them away, or even to sell them.

Modern ideas of rights and liberties are derived from what came to be known as “natural rights theory”—from the time when Jean Gerson, Rector of the University of Paris, began to lay them out around 1400, building on Roman law concepts. As Richard Tuck, the premier historian of such ideas, has long noted, it is one of the great ironies of history that this was always a body of theory embraced not by the progressives of that time, but by conservatives. “‘For a Gersonian, liberty was property and could be exchanged in the same Way and in the same terms as any other property’—sold, swapped, loaned, or otherwise voluntarily surrendered.” It followed that there could be nothing intrinsically wrong with, say, debt peonage, or even slavery. And this is exactly what natural-rights theorists came to assert. In fact, over the next centuries, these ideas came to be developed above all in Antwerp and Lisbon, cities at the very center of the emerging slave trade. After all, they argued, we don’t really know what’s going on in the lands behind places like Calabar, from which so many men and women were being enslaved and shipped to the Americas, but there is no intrinsic reason to assume that the vast majority of the human cargo conveyed to European ships had not sold themselves, or been disposed of by their legal guardians, or lost their liberty in some other perfectly legitimate fashion. No doubt some had not, but abuses will exist in any system. The important thing was that there was nothing inherently unnatural or illegitimate about the idea that freedom could be sold.

Before long, similar arguments came to be employed to justify the absolute power of the state. Thomas Hobbes was the first to really develop this argument in the seventeenth century, but it soon became commonplace. Government was essentially a contract, a kind of business arrangement, whereby citizens had voluntarily given up some of their natural liberties to the sovereign. Finally, similar ideas have become the basis of that most basic, dominant institution of our present economic life: wage labor, which is, effectively, the renting of our freedom in the same way that slavery can be conceived as its sale.

It’s not only our freedoms that we own; the same logic has come to be applied even to our own bodies, which are treated, in such formulations, as really no different than houses, cars, or furniture. We own ourselves, therefore outsiders have no right to trespass on us.

This might seem an innocuous, even a positive notion, but it looks rather different when we take into consideration the Roman tradition of property on which it is based. To say that we own ourselves is, oddly enough, to cast ourselves as both master and slave simultaneously. “We” are both owners (exerting absolute power over our property), and yet somehow, at the same time, the things being owned (being the object of absolute power).

The ancient Roman household, far from having been forgotten in the mists of history, is preserved in our most basic conception of ourselves—and, once again, just as in property law, the result is so strangely incoherent that it spins off into endless paradoxes the moment one tries to figure out what it would actually mean in practice. Just as lawyers have spent a thousand years trying to make sense of Roman property concepts, so have philosophers spent centuries trying to understand how it could be possible for us to have a relation of domination over ourselves. The most popular solution—to say that each of us has something called a “mind” and that this is completely separate from something else, which we can call “the body,” and that the first thing holds natural dominion over the second—flies in the face of just about everything we now know about cognitive science. It’s obviously untrue, but we continue to hold onto it anyway, for the simple reason that none of our everyday assumptions about property, law, and freedom would make any sense without it.

To understand the history and, ultimately, incoherence of the notions of liberty grounded in Roman notions of dominion is to potentially free ourselves to re-imagine liberty. For example, to recognise the forgotten “obligations owed everyone in the entire world” inherent in our freedoms; but also to resurrect the older notion of liberty as the state achieved by citizens acting together in determination of a common good.

#repost of someone else’s content#graeber#history#ancient Rome#medieval Europe#slavery#mind-body dualism#racism#antiblackness#liberals#liberalism#classical liberalism#capitalism#private property#social contract#natural rights#consent of the governed#anarchism

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

"We're free"

"Tuesday. September 14, 2010. 8:44pm

My sister Zoe hit me up for money. She wants to move to Humbolt County and live in a tent. Atwater frustrates her.

I said “No.” (To giving her money)

Zoe replied “have a nice life.” (Meaning, she was cutting me out of her life)

( On 11/16/2010 I wrote in a margin note to the 9/14/2010 entry, “yesterday she did it again . (asked for money) This time, folded in with threats of suicide and eminent death”.)

She’s out (of Mom’s house) by 10/1/2010 per Dan, our younger brother. (Zoe had been living with our mother in our family home in Atwater for several months or more)

On the drive back from San Fransisco today, I was imagining visiting Mom .

I’ll kiss her goodbye for the last time and leave without a word.

No social capitol left there. None.

No one I want to see or to talk to. None.

Because I know they have been poisoned her against Zoe and I.

I reminded Zoe of what she said to me July 30, 2010 or so: “We’re free.” (of the family))

(The day after the 7/29/2010 insurrection meeting in which brother Dan replaced me as executer of Mom’s trust) Then be free, Zoe.

Don’t see Mom ever. Let her go.

She’s in their world now.

Respect that.

End of entry

Notes

Social Capitol is “the networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society, enabling that society to function effectively."

When my brother orchestrated my removal as the executor of my parent's trust, he broke the social contracts of brotherhood and of family.

Zoe was my sister who died in 2023. I was with her when she died.

I didn't hear from my mother for the last year of her life. Prior to 2010, we had been very close.

Dan is my younger brother who I cut ties with in 2012 after my mother died. The day after her funeral, which I did not attend, I received her amended trust in which she had disinherited my sister and I and left everything to brother Dan, his wife, her son and his wife.

A song I listened to often in 2011 was "Jar of Hearts" by Christina Perri. It caught the spirit and tone of the ugly break up of our family and helped me transition into my new life outside family.

#Family break up#set up to disinheretence#cutting family ties#Social Capitol#Social contract#Jar of hearts by Christina Perri

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Look at it this way. You’re still a child, and you can’t earn your living or look after yourself properly. When you were younger, you could do it even less. All children are the same. So the law says that someone has to look after you until you can do it for yourself—your guardians in your case. And there’s another law which says that when you drop a stone it falls to the ground. Are you grateful to that stone for falling, or does the stone ask the earth to be grateful?”

“I—oh—” David felt there was something missing from this. “But people aren’t stones.”

“Of course not. And if people do anything over and above the law, then you can be grateful if you want. But no one should ask it of you.”

Diana Wynne Jones, "Eight Days of Luke"

#diana wynne jones#eight days of luke#mr wedding#david allard#odin#gratefulness#dysfunctional families#family dysfunction#social contract#children#raising children

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

In this week's episode, at the 6 month mark of the US/Israeli terror campaign against Palestine and the surround countries, we discuss the lack of public support vs the US government's ongoing supplying of weapons and funds, the attack on World Central Kitchen aid workers and Iranian embassy, and more.

#social contract#rbn#revolutionary blackout network#indie news#indie journalism#independent journalism#independent news#history#politics#us politics#international politics#freedom for gaza#free palestine#justice for palestine#palestinian genocide#israeli occupation#war crimes#government corruption#universal healthcare#tax the rich#poverty#commercialization#wage theft#palestine#justice for gaza

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm a bit upset again today about the whole work situation.

It just feels insane that I could put two and a half years of my life into working somewhere, doing everything I could to be helpful, to help cover for colleagues, to do work above my pay grade etc. and to go above and beyond to build connections with people and do everything you're meant to do to secure your career...

Only to be unceremoniously let go due to budget cuts, after months upon months of them saying they would be able to give me a full permanent contract 'soon' if I just kept working there a bit longer on my existing contract.

It feels really shitty and what's worse, I feel like any other workplace will probably treat me the same way. It doesn't fill me with excitement to start from the bottom again somewhere new. And I mean 'again', this will be the third time this happens.

It just feels like we live in a society nowadays where there really is not even the pretence of a social contract or pretending that those with less power, the employees, the labourers, the workers, will EVER have any prospect of long-term security of any sort the way our parents' generation did if they just reached a certain standard of achievement and good behaviour and weren't very unfortunate.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

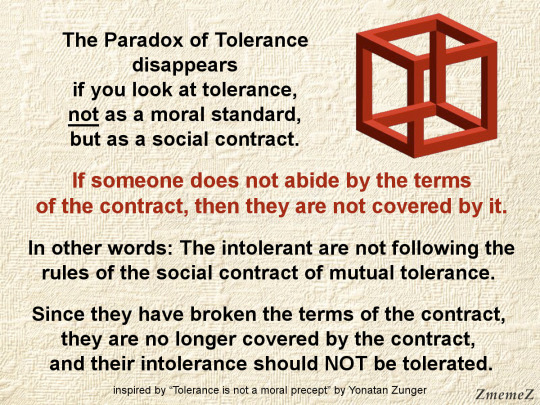

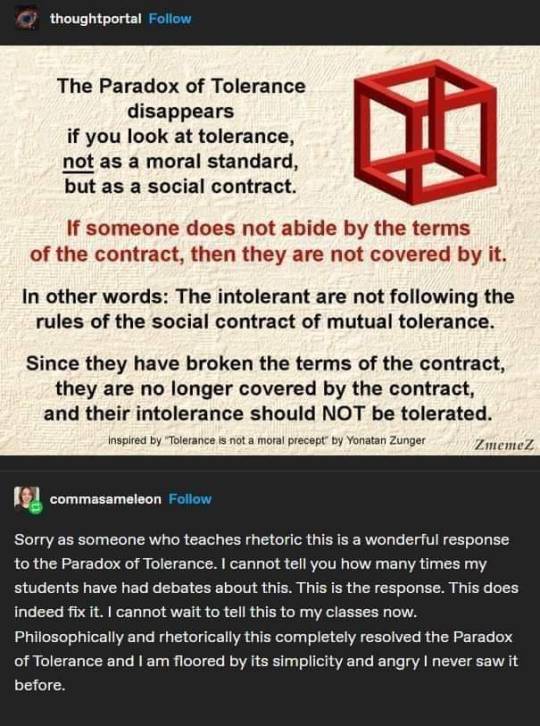

The Paradox of Tolerance rethought

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Liberals came up with the whole concept of a "social contract" to explain that people obey laws in return for the state offering protection. Then they see the police murder a child and say "well I'm not sure that justifies breaking the law!!!"

What part of their own useless philosophy don't they understand?

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rousseau, if there are things occurring that haven't been written in my social contract, can I renegotiate?? With society??

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Found on Masto, permission granted by creator [email protected], inspired by Zunger’s concept that tolerance is a peace treaty that cannot apply to those who refuse to abide by the treaty.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Leviathan Unveiled: Navigating the Depths of Hobbesian Political Philosophy"

Thomas Hobbes' "Leviathan" stands as a seminal work in political philosophy, providing a profound exploration of the social contract and the nature of government. Published in 1651, during a tumultuous period in English history, Hobbes crafted a philosophical masterpiece that sought to address the chaos and disorder prevalent in society.

The central theme of "Leviathan" revolves around Hobbes' depiction of the hypothetical state of nature, a condition he famously describes as a "war of every man against every man." Hobbes contends that without a structured authority, human life would be characterized by constant conflict and anarchy. To escape this state of nature, individuals enter into a social contract, surrendering some liberties to a sovereign authority in exchange for protection and order.

The metaphorical "Leviathan" represents this sovereign power, a colossal entity with the authority to maintain peace and prevent chaos. Hobbes argues for the absolute power of the Leviathan, suggesting that a powerful centralized government is necessary to ensure the stability of society. This perspective, while controversial, laid the groundwork for later political philosophies and discussions on the role of government.

Hobbes' work also delves into the relationship between church and state. He advocates for a unified authority to avoid conflicts arising from religious differences. In his view, the sovereign power should control both the ecclesiastical and civil spheres to maintain social cohesion.

One of the strengths of "Leviathan" is Hobbes' systematic approach to political theory. He applies a scientific methodology, drawing parallels between the natural world and political structures. This analytical framework was innovative for its time, influencing subsequent philosophers and political thinkers.

However, "Leviathan" has sparked significant debate and criticism. Hobbes' advocacy for absolute monarchy and his rather bleak view of human nature have been challenged by later philosophers who championed individual liberties and more optimistic perspectives on human behavior.

In conclusion, Thomas Hobbes' "Leviathan" remains a cornerstone of political philosophy, offering a foundational exploration of the social contract, sovereign authority, and the structure of government. While controversial and subject to critique, its impact on the development of political thought cannot be overstated, making it an essential read for those interested in understanding the roots of modern political theory.

Thomas Hobbes' "Leviathan" is available in Amazon in paperback 19.99$ and hardcover 25.99$ editions.

Number of pages: 484

Language: English

Rating: 8/10

Link of the book!

Review By: King's Cat

#Thomas Hobbes#Political philosophy#Commonwealth#Leviathan#Ecclesiastical#Civil#State power#Social contract#Political theory#Sovereignty#Absolutism#Political authority#Human nature#Political science#Government#Power dynamics#Social order#Political structure#Statecraft#Absolute authority#Commonwealth theory#Civil society#Political obligation#Commonwealth formation#Political theology#Civic governance#Social contract theory#Authority and obedience#Leviathan symbolism#Hobbesian philosophy

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tag country and answer (1-5, top to bottom) if you don’t mind.

#free palestine#social contract#democracy#lgbtq community#covid19#ukraine#congo#yemen#china#usa#uk politics#russia#argentina#saudi arabia#a11y

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reflection: On the Social Contract

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in On the Social Contract, writes on the nature of freedom, oppression, humanity, and government, outlining the “social compact” as a means to measure and attain what he values most in polity—independence. Rousseau critiques his contemporaries, particularly Hugo Grotius, for sophist justifications of slavery, criticizing their understanding of power and politics, and contending that the ultimate sovereign authority for any state lies in the collectivized will of its people.

Rousseau begins his work with a brief, poetic description of the human condition regarding independence—“Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains”—an eloquent phrase outlining the nature of social existence: only in one’s infancy is the individual unshackled from their social obligations (141). At face value, law and order would seem to be the enemy of autonomous agency in light of this observation. This extends beyond the level of the individual. Society is as shackled in its growing into maturity as the persons who constitute it, according to the philosopher. This imprisonment is avertable, though, and the author resolves to construct a mechanism by which a state may orient itself according to the united will of its people, referred to as the “social compact.” To more fully understand this, an examination of Rousseau’s ethic of force is requisite.

Interstitial to On the Social Contract is a striking critique of unexamined Machiavellian notions of force and power. Rousseau targets the work of Hugo Grotius, in particular, as an example of the philosophical inadequacies of such a base understanding of social order. The first four chapters of Book I (Subject of the First Book, Of the First Societies, On the Right of the Strongest, and On Slavery) are dedicated to dismantling such naturalist positions that justify the “right to rule” on the basis of force alone. He writes, “Grotius denies that all human power is established for the benefit of the governed, citing slavery as an example. His usual method of reasoning is always to present fact as a proof of right. A more logical method could be used, but not one more favorable to tyrants” (142). This reveals a few of Rousseau’s primary complaints: that his contemporaries 1) confuse status quo for status potissimus, making out the current state of affairs to be equivalent to a perfect (or at least reasonable state), and 2) do so in favor of their own self-interest, as a political action that substitutes a conscientious desire for good with a cowardly craving for security, acting much like the tyrants who they tacitly support. Rousseau asserts his aversion to this framework, noting that inequality does not stem from innate qualities of persons, but rather that “force has produced the first slaves.” [1]

Grotius’s position seems to follow a misguided line of reasoning about just acts in war, which Grotius uses to construct an understanding of compliance and obligation that makes the two synonymous. He concludes that, in war, one man has a right to kill another, and exercises that right through force. Grotius then notes that a more “legitimate” act, in such conditions, is the enslavement of the overpowered adversary, because it allows for more “profit” to both parties. [2] Further, he derives from this so-called legitimate act in war a privatized right of those in power to dictate the actions of those who fall prey to them, and considers the impulse to obey such commands to be the slave’s moral duty. Rousseau finds this argument to be ill-devised, in large part because war is divorced from the individual’s moral capacity—it stems from the state; a state cannot enslave a people since it is, by nature, composed of those people. Rather, should a people be oppressed under a state’s authority, that state is ruled by private opinion, by the minority, and is no longer a legitimate extension of such oppressed peoples’ moral power. Rousseau asserts that this state is not sovereign, or even a nation in any real sense: regarding this, he argues, “I see nothing but a master and slaves; I do not see a people and its leader. It is, if you will, an aggregation, but not an association. There is neither a public good nor a body politic there” (147). Persons under this condition have been robbed of their right to autonomy and cannot, as such, possess a duty to their masters. Still, Grotius’s standpoint contends that slaves have donated their right to life and must adhere to the mandates of their oppressors independently (i.e. as moral agents), as a pseudo-indemnification to repay their captors for their continued vital state.

Grotius’s rationale is ironic, since it posits a “donation” of rights that nevertheless indebts the donor to their charitable recipient. Moreover, in a state of war, the principle right at stake for the citizen is their life, and autonomy by extension, yet Grotius does not consider the ethical liability relinquished alongside its source. Again, he confuses the prima facie state of things (that a slave apparently has a duty to obey a master) with the correct state of things (that a slave is obligated, through force).

This, of course, is a shallow argument, and fails to consider the relative moral weight of obedience compared to duty. The former, Rousseau contends, is morally empty; in On Slavery, he writes, “Removing all liberty from [a person]’s will is tantamount to removing all morality from his actions” (145). One cannot consider themselves to be a complete moral agent if they’ve surrendered their agency. Since liberty is necessary for any person to consider their thoughts, actions, and duties to be rational, sound, and binding, such a person, in Rousseau’s eyes, has surrendered not only their agency, but their own moral burden as well.

Rousseau’s introductory statement is further developed in this—one shackled under the yoke of society is free from some moral burden beneath it, as their ethical instrumentality is limited. To exemplify this, one may consider that a person who does not belong to a collective justice system may have a proper burden to seek retribution should another commit a crime against them. However in a body politic, this otherwise just act is criminalized as vigilantism and substituted with a systemic means of seeking restitution limited by a right to due process, afforded by some sovereign body. We will discuss this example at greater length later, as it gives additional insight into the nature of Rousseau’s argument. For now, it serves to illustrate that the subject in question emancipates themselves from their burden of retribution by their collaboration with their body politic.

Grotius has a response to this—he notes that a people can choose subjugation in giving themselves over to a particular sovereign. From this, Rousseau dissolves his opponent’s claims as, he points out, in order for a people to choose to collectively become subjects, they must be a collective in the first place. This is implicit in Grotius’s claim, and Rousseau finds common ground here to establish a “true foundation of society” (147). From this, Rousseau begins a positive construction of his social compact wherein the state of nature’s limitations on humanity’s maintained existence are overcome through an “alter[ed] mode of existence” (147). Of course, this mode of existence ought to preserve the goods inherent to the state of nature, in particular, freedom. To accomplish this, Rousseau composes the following basis for a proper, reasonable society: treating each person’s will as a variable which is optimized summarily with their peers, a society exists when this sum maximizes, positing a basis for sovereignty contingent on a sort-of “Pareto Optimality” of freedom. The philosopher refers to this maximal state as the “general will." Put in simpler terms, “true” society arises when each person acts in their greatest free capacity, insofar as that capacity does not, on the whole, inhibit the will of another, and limits on peoples’ will are agreeable if each person’s most possible free state is actualized by those limitations. [3]

Returning to the previous example, the person who forgoes their right to retribution in exchange for a right to due process has not given up much freedom on the whole but ensures that, by their sacrifice (and the sacrifice of each member of their state), the whole of society affords greater freedom by means of a fair justice system, where revenge and retribution are not as readily confused. Further, by unshackling that person from the duty to enact retribution, moral culpability for the action is the whole of that society's, motivating it and empowering it to construct systems that should be more capable of fulfilling those moral obligations bestowed upon it by the surrendered agency of its constituents.

Rousseau does not consider the general will to be a guiding moral principle. It is, at most, a means to test the validity of governance. This is clear in Book II, Chapter VIII, entitled On the People, where Rousseau considers that a people may freely choose vice, even collectively, and still act according to the general will, citing King Minos in Crete as a good lawmaker who “disciplined nothing but a vice-ridden people.” Of course, Rousseau considers this to be the exception, rather than the rule. Rousseau regresses in his argument when evaluating this case, proclaiming that a nation where the general will covets evil and has already undergone violent reform, needs a “master,” since “liberty can be acquired, but it can never be recovered” (166).

This notion is applied by Rousseau axiomatically, and (unsurprisingly) stirs up controversy. For one, astute readers will point to many nations which have undergone successive revolutions, such as France, China, Germany, etc.. This is an understandable misconstruction. The nations, at each of those revolutionary junctures, take on the same name as their predecessor, giving the illusion of continuity. Should the peoples’ general will allow it, they may even take on some of the same laws and customs. Yet each nation is born anew through these changes, and one cannot reasonably assert that the nations in question are constituted in the same way—the body of law discharged at these moments of change is altered too significantly to consider the nation to be the same, and indeed the context of the nation changes just as much with the passage of time. Were nations men and time a flowing river, Heraclitus’s famous words would come to mind, that, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it is not the same river and he is not the same man.” At every point, the changing of a nation’s general will necessitates a new understanding of what that nation is.

The former notion of Rousseau’s is the more suspect of the two, though—that a state which revolts unsuccessfully against a corruption of morality or authority requires a master, rather than a liberator. His analysis of Peter the Great will assist us here. He notes that, in response to the Russian citizenry’s “barbarousness,” the monarch attempted to civilize his people prematurely (166). The philosopher’s assertion here is not that Peter was wrong in attempting to follow the general will of his people, but that in his imitations of Europe, he failed to allow his peoples to form a collective will of their own. As such, Rousseau seems to believe it would have been better for the Russians to have remained "un-westernized" until they’d established their cultural identity by forming a social order without the prompting of the monarch. This allows for a more true expression of the general will, in Rousseau’s eyes. In lieu of political turmoil, Rousseau seems to share this sentiment—that it is better for an infantile nation to constitute itself, and that a “master” acts as some necessary evil, a holdover until such a nation reaches the vigor of its youth.

Rousseau's critique of Grotius and his contemporaries can be seen as a call to reject the naturalistic justifications for oppression and to instead embrace a more collectivist understanding of the social contract. By emphasizing the importance of the social compact and the need for a legitimate and moral authority to oversee it, Rousseau seeks to provide a framework for creating a society that is both free and just. While his ideas may not have been fully realized in his own time, they remain relevant today as philosophers continue to grapple with questions of freedom, power, and oppression in contemporary societies.

Notes:

[1] Notably, Rousseau is not altogether modern in his stance here. In the same breath he asserts that “[Slaves’] cowardice has perpetuated [slavery].” Obviously, this is not aligned with the true nature of slavery, but it is consistent with much of Rousseau’s argumentation. For instance, in his discussion of a prince’s apparent wrongly-extended right to avoid usurpation on the pretense of peace, Rousseau notes that the apparent compliance of that sovereign’s people who he deceives and silences appears indicative of the favor of the general will, contrary to the matter-of-fact. Rousseau places the responsibility to circumvent this pattern in the hands of the people, though, in gathering and collaborating in their collectivized aspirations. This is much like his assertion about slavery—he regards the prince and the slaver as immoral actors, but does not see such judgements as actionable outright—the recipients of these injustices must, in Rousseau’s eyes, respond with clarity and purpose.

[2] This profit extends, in Grotius’s point of view, beyond material gain. His position contends that there is further value in subjugation insofar as it brings about a state of security; a slave’s master offers protection. This rationale is common to tyrants and warring states, and Rousseau argues that a polity that truly craves peace over autonomy is mad, and thereby not reasonable enough to be considered a people in the first place, since “Madness does not bring about right.” (144) One can find placid environments in all manner of undesirable places, such as dungeons and caves, but Rousseau seems to find that Grotius and his contemporaries would hardly vouch for those conditions on account of this one merit—so enforced order clearly cannot be the keystone metric for societal flourishing, given this exception. However, Rousseau is not consistent in this analysis, as he notes that a silent peoples’ consent to private will can be equated with the general will (154) despite these peoples not expressing a general will or even acting according to his own definition of a political “body.” (150). Further, his position here runs counter to the argument discussed in [1] regarding the devious prince.

[3] Note, this is distinct from each person’s desired willful state—Rousseau does not believe that each person, left to their own devices, will act according to the general will, as humans are wont to neglect the freest possible state of a collective in favor of the freest possible state of the self. It is best not to conceive of the general will as the abstracted private will of any one citizen or group of citizens, but rather as a social order constructed to optimize the autonomous capacity of its people, by treating them, at times, as subjects. However, this does not mean a state of anarchy is impossible according to the social contract, as is evidenced in the final paragraph of the third book where he writes “For if all the citizens were to assemble in order to break this compact by common agreement, no one could doubt it was legitimately broken” (203).

Bibliography:

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “On the Social Contract,” in Basic Political Writings, Edited and translated by Donald A. Cress, 141-204. Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, 1987.

#philosophy#art#ethics#aesthetics#aesthetic#ethical#critique#beauty#sublime#religion#continental#revolution#politics#social contract#rousseau#slavery#grotius#an analysis of some philosophical shade#Not my proudest piece tbh#readability is LOW#Apologies#Discussion is welcome and encouraged#Love a good philosophical convo so let's get this thing crackin#Eh

8 notes

·

View notes