#tamil words

Video

youtube

உயிர் எழுத்துக்கள் அ அம்மா ஆ ஆடு இ இலை உயிர் எழுத்துக்கள் #அ #அஆ #tamil

1 note

·

View note

Text

❤️ உன்னுள் உறைந்தவள்❤️

உன்னுள் உறைந்தவன்

Customized Tshirt collection

For details

9750597508

#உன்னுள் உறைந்தவள்#avalumnanum#couples collection#couples tshirts#tamil quotes#tamil words#couples gifts#couple forever#couples shopping online#avalum nanum song#customisedtshirts🖤#cottontshirts#tshirtfashion#tshirts#salé#tshirtsonline#music#yolo#yoloshop#yolofashionfactory

0 notes

Text

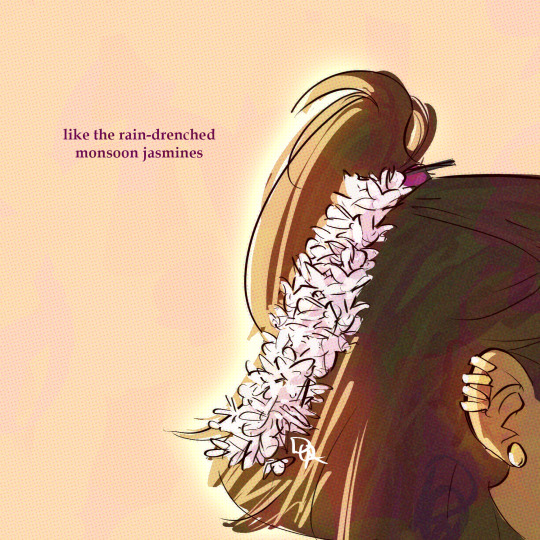

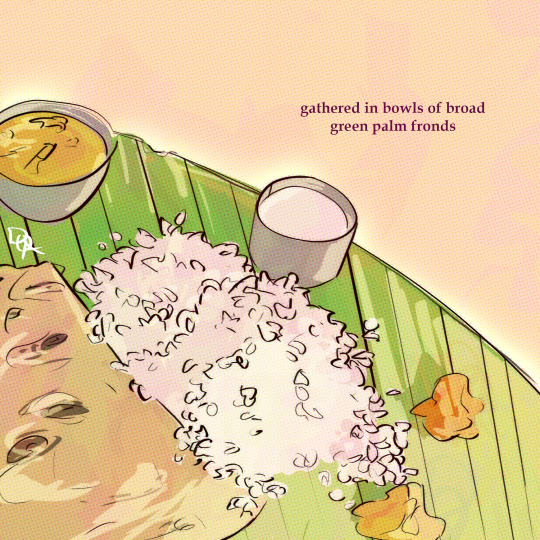

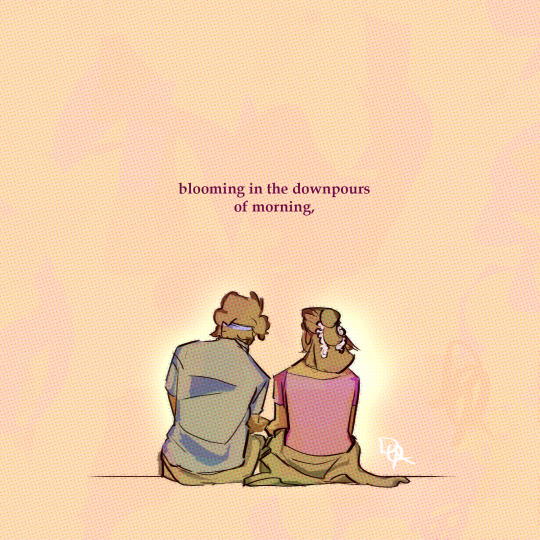

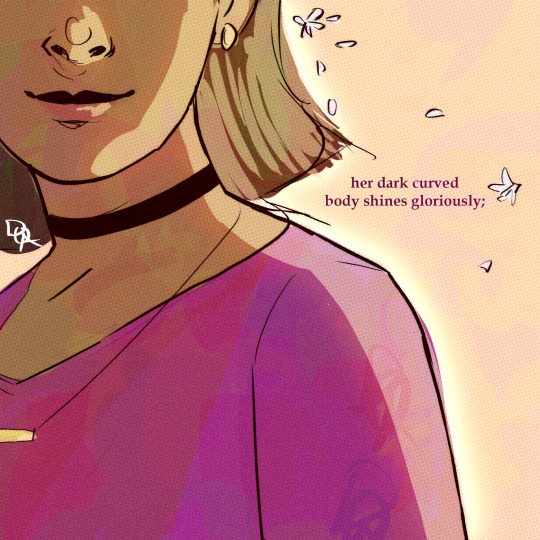

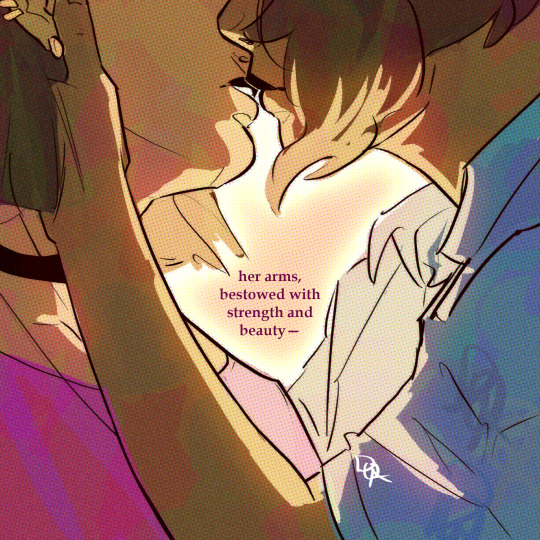

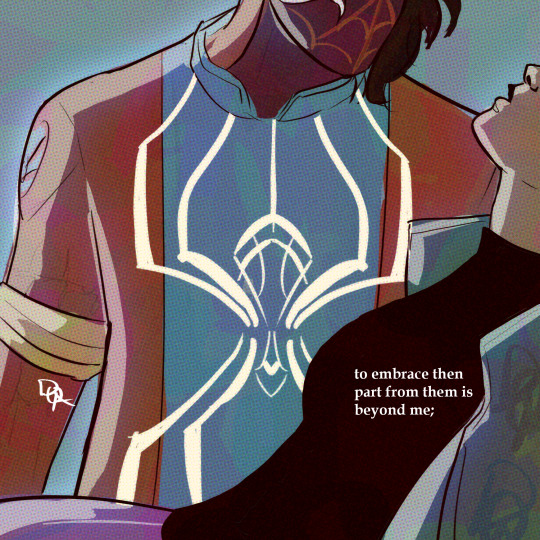

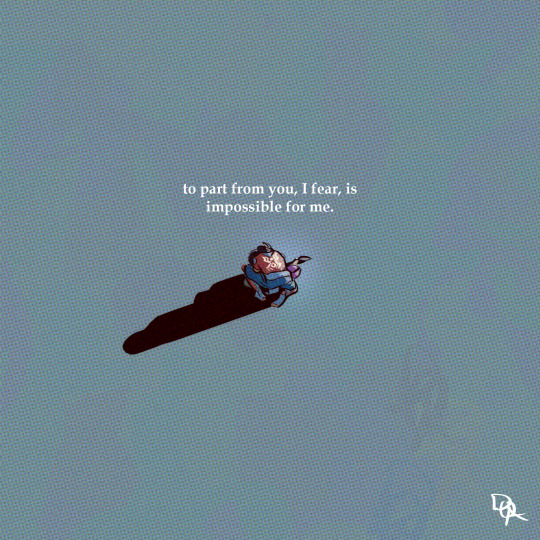

kurunthokai, 168 — “what the hero said to his heart”

#i did this in a rush. that's why some things look wonky and weird and T-T#me drawing vague shapes then scribbling over them#here is some pavayatri for you#goldenmodel#pavitr x gayatri#literally whatever you call them#i tried translating slash rewriting the original kurunthokai poem#but it's in pure tamil so most of the words don't really line up with modern tamil/english#so i put my degree in bad writing to use. hopefully this does the poem justice#anyway yeah. have these babies#i love pavitr and gayatri so much!!!!!#i saw this poem and immediately thought “you know what would be absolutely sick. asm121 redraw”#and then I DID IT#no i am not sorry. not really. dw i gave myself psychic damage while drawing this#“the night gayatri singh died” be like#gayatri singh#pavitr prabhakar#spider man india#atsv#atsv pavitr#spider man#artoftheagni#its 1am rn if you have any beef with me please wait another six hours. i hate staying up so late

298 notes

·

View notes

Text

RAHH HAN SOOYOUNG IN A VESHTI 🦚🦚🦚🔥🔥🔥

(inspired by yapping on a server also translation under the cut)

hsy: "How is it? my ✨epic swiggity swagger✨>:))"

yjh+kdj: "Wha?"

that being said "✨gethu✨" is a hard word to translate (theres rambling in the notes though so)

#ok not my best work but i hadavision (if you see any mistakes no you dont)#idk how to translate “gethu”#when i try to define “gethu” my first thought is “maas” and thats also tamil so#swag is the closest word but think coolness; badassery; the energy of a cocky kollywood protagonist who beats up bad guys and shit#and is terrible at flirting with women but somehow bags them anyways (sangsoo (also yoohan if you count punisher)) etc etc#han sooyoung however understands the essence of gethuness because she IS the essence of gethuness#more tl notes is that hsy is speaking in a p slangy way#the hand wrap is the abfd thing bc ppl never draw her with it#pose ripped off pinterest#yeag.#orv#hsy#han sooyoung#omniscient reader's viewpoint#uhuhuhh#my art#art

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

JOURNAL IT ALL!

fifteen, twenty, fourty years from now- like they are lying and deceiving us today- they will lie and deceive then too. therefore, i urge you to document all the details of these "wars" as they say it for the lack of better word, to the best of your ability. or rather, make a whole seperate journal and pen down the details. include diagrams, census, logistic reports and comparison charts. all the screaming you're doing, SAVE it; incase they try to distort history.

#SPREAD THE WORD#palestine#gaza#tamil eelam#hawaii#rohingya#uyghurs#africa#ethiopia#congo#sudan crisis#somalia#sudan#yemen#syria#lebanon#burkina faso#afghanistan#others#kurdistan

76 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think one could attain decent-ish ability to read Japanese just by studying kanji? Specifically asking because the kanji learnin' service "wanikani" is the single Japanese resource that works best with my brain, but then there are separate resources for grammar and vocab and and and.....

You will get REAAAALLLLLYYY far knowing only the kanji but you're going to have to know hiragana and katakana at some point too. Tofugu, the company that did Wanikani, has two mnemonics-based guides for the kana that are basically Wanikani Lite. They're how I learned the kana and I swear by them.

Here's hiragana: https://www.tofugu.com/japanese/learn-hiragana/

And katakana: https://www.tofugu.com/japanese/learn-katakana/

Hiragana are especially vital to learning kanji; you won't be able to use 99% of Japanese-English dictionaries without them. BUT they're pretty easy and the rules for using them are consistent. You won't have to remember any irregular exceptions for any of them.

I haven't tried it yet, but I've heard really good things about the Crystal Hunters manga series as a fun/low stress way to learning Japanese vocab and grammar. It eases the reader into new concepts and then repeats them throughout the chapter so you remember them. There are free vocab and study guides/lists for each chapter too. Might be worth checking out once you get some kanji and the kana under your belt? The first book is also free.

Official site: https://crystalhuntersmanga.com/

Good luck!!

#asks#Japanese takes like a bajillion hours forever to learn because of the 2200+ kanji lol...........#But it's sooooo consistent grammatically and with the spelling. I love it#Kinda spoiled me tbh. I look at English now and I'm like#'Why can't you be more like this. Why are you such a mess. Get your act together'#And then there's Korean's hangul writing system. It's SO BEAUTIFUL. Actual marvel of linguist engineering#The Japanese lexicon is also a lot smaller than English's too. Which is both a blessing and a curse#Less words = quicker to learn. BUUUUUTTTT less words that mesh well with English. Translation is hard!!!#Holy fuck. Ok so Wikipedia says that the English language has 755`865 words as recorded by Wiktionary#and Japanese has 500`000 according to Nihon Kokugo Daijiten#BUT THEN KOREAN. ACCORDING TO ONLINE DICTIONARY URIMALSAEM (open source dictionary) HAS 1`149`538 WORDS#The biggest lexicon is Tamil's with 1`516`952 unique headwords as recorded by online dictionary Sorkuvai#That's absolutely nuts#I got massively distracted. Enjoy my word vomit tags

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Somtimes life means you gotta just sit there and play through the entirety of Venba on your switch in one sitting and just. Feel the shrimp emotions

#Venba#Switch Venba#Venba 2023#Venba game#im biracial indian#and while not Tamil#SO much of this game made me think of both my Indian parent and their relation to their parents#and as someone who does not know what feels like should be one of my mother tongues#it leads me to feeling so often like an imposter in my identity#almost feeling as though I have nothing to show for being Indian other than some features and my parent#and as someone who is admittedly white passing#it leaves such a gap#and I remember awhile ago someone asked why I cant just learn the language for myself#and I had to describe it like#planting a dead seed; while you are still planting it and learning the languge#it does not have room to grow#it cannot flourish#you can learn the words and languge but it will never grow with you instead it will feel almost tacked on#and I also have a learning disability#which heavily impacts my ability in learning new languages#so learning a language is neigh impossible for me#so its safe to say I was crying and just sitting#thinking#after finishing Venba lol

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Microsoft Work From Home

Microsoft Work From Home Details Below:

Working from home for Microsoft offers various opportunities across different departments and roles. Microsoft is known for its flexible work policies, which include many remote positions. Here’s a look at some of the work-from-home opportunities at Microsoft:

Sales and Account Management

Marketing and Communications

Product Management

Technical Support and Customer Service

More Details

#microsoft#microsoft 365#microsoft teams#microsoft office#microsoft teams tutorial#microsoft word#what is microsoft 365#how to use microsoft teams#microsoft job#microsoft team#microsoft hiring#microsoft recruitment#how to use microsoft word#microsoft office 365#microsoft internship#nishant chahar microsoft#microsoft work from home jobs#microsoft internship india#work from home with microsoft teams#microsoft work from home jobs tamil#word microsoft

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part Time Microsoft Work From Home

Working from home for Microsoft offers various opportunities across different departments and roles. Microsoft is known for its flexible work policies, which include many remote positions. Here’s a look at some of the work-from-home opportunities at Microsoft:

Sales and Account Management

Marketing and Communications

Product Management

Technical Support and Customer Service

More Details

#microsoft#microsoft 365#microsoft teams#microsoft office#microsoft teams tutorial#microsoft word#what is microsoft 365#how to use microsoft teams#microsoft job#microsoft team#microsoft hiring#microsoft recruitment#how to use microsoft word#microsoft office 365#microsoft internship#nishant chahar microsoft#microsoft work from home jobs#microsoft internship india#work from home with microsoft teams#microsoft work from home jobs tamil#word microsoft

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Song of Songs has quite recently (1973) been assigned to the time of Solomon by a distinguished Hebraist, Professor Chaim Rabin of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. For more than forty years now evidence has been accumulating for some kind of relationship between the cities of the Harrapan civilization of the Indus Valley and lower Mesopotamia during the latter part of the third millennium B.C. and into the second (cf. C. J. Gadd, PBA, 1932). Rabin (205) called attention to the few dozen typical Indus culture seals which have been found in various places in Mesopotamia, some of which seem to be local imitations. He suggested that these objects were imported not as knickknacks, but because of their religious symbolism by people who had been impressed by Indus religion. To the examples of Indus type seals in Mesopotamia cited by Rabin (217n2), we may add a dated document from the Yale Babylonian Collection, an unusual seal impression found on an inscribed tablet dated to the tenth year of Gimgunum, king of Larsa, in Southern Babylonia, which according to the commonly accepted "middle" chronology would be 1923 B.C. (B. Buchanan, 1967).

[...]

Rabin cited a story from the Buddhist Jatakas, the Baveru Jataka, which tells of Indian merchants delivering a trained peacock to the kingdom of Baveru, the bird having been conditioned to scream at the snapping of fingers and to dance at the clapping of hands. Since maritime connection between Mesopotamia and India lapsed after the destruction of the Indus civilization, and since the name Baveru (i.e. Babel, Babylon) would hardly have been known in the later period when trade with India went via South Arabia, Rabin concluded that the Jataka story about the peacock must ultimately date before 2000, an example of the tenacity of Indian tradition (p. 206). Ivory statuettes of peacocks found in Mesopotamia suggest that the birds themselves may also have been imported before 2000 B.C. (cf. W. F. Leemans, 1960, 161, 166), and Rabin (206) wondered whether the selection of monkeys and peacocks for export may not have derived from the Indian tendency to honor guests by presenting them with objects of religious significance. Imports of apes and peacocks are mentioned in connection with Solomon's maritime trade in I Kings 10:22 [=II Chron 9:21], the roundtrip taking three years. The word for "peacocks," tukkiyyim, singular tukki, has since the eighteenth century been explained as a borrowing of the Tamil term for "peacock," tokai. Tamil is a Dravidian language which in ancient times was spoken throughout South India, and is now spoken in the East of South India. Scandinavian scholars claim to have deciphered the script of the Indus culture as representing the Tamil language (cf. Rabin, 208, 218n20). Further evidence of contact with Tamils early in the first millennium B.C. is found in the names of Indian products in Hebrew and in other Semitic languages. In particular Rabin cites the word 'ahalot for the spice wood "aloes," Greek agallochon, Sanskrit aghal, English agal-wood, eagle-wood, or aloes, the fragrant Aquilaria agallocha which flourishes in India and Indochina. The Tamil word is akil, now pronounced ahal. Its use for perfuming clothing and bedding is mentioned in Ps 45:9 [8E] and Prov 7:17 and Rabin surmised that the method was one still current in India, the powdered wood being burned on a metal plate and the clothing or bedding held over the plate to absorb the incense. Rabin supposed that it was necessary to have observed this practice in India in order to learn the use of the substance (p.209). Aloes are mentioned in 4:14 among the aromatics which grace the bride's body. The method of perfuming bedding and clothing by burning powdered aloes beneath them may clarify the puzzling references to columns of smoke, incense, and pedlar's powders in connection with the epiphany of "Solomon's" splendiferous wedding couch ascending from the steppes (3:6-10), bearing it seems (cf. 8:5) the (divine?) bride and her royal mate. Myrrh and frankincense only are mentioned, but "all the pedlar's powders" presumably included the precious aloes from India.

Opportunity to observe Indian usages would have been afforded visitors to India in the nature of the case, since the outward journey from the West had to be made during the summer monsoon and the return trip during the winter monsoon, so that the visitor would have an enforced stay in India of some three months. Repeated visits with such layovers would provide merchant seamen with the opportunity to learn a great deal about local customs, beliefs, and arts.

After a brief critique of modern views about the Song of Songs, none of which has so far found general acceptance, Rabin ventured to propound a new theory based on Israel's commercial contacts with India during Solomon's reign.

There are three features which,in Rabin's view (pp. 210f), set the Song of Songs apart from other ancient oriental love poetry. Though occasional traces of these maybe found elsewhere, Rabin alleged that they do not recur in the same measure or in this combination:

1. The woman expresses her feelings of love, and appears as the chief person in the Song. Fifty-six verses are clearly put into the woman's mouth as against thirty-six into the man's (omitting debatable cases).

2. The role of nature in the similes of the Song and the constant reference to the phenomena of growth and renewal as the background against which the emotional life of the lovers moves, Rabin regarded as reflecting an attitude toward nature which was achieved in the West only in the eighteenth century.

3. The lover, whether a person or a dream figure, speaks with appropriate masculine aggressiveness, but the dominant note of the woman's utterances is longing. She reaches out for a lover who is remote and who approaches her only in her dreams. She is aware that her longing is sinful and will bring her into contempt (8:1) and in her dream the "watchmen" put her to shame by taking away her mantle (5:7). Ancient eastern love poetry, according to Rabin, generally expresses desire, not longing, and to find parallels one has to go to seventeenth-century Arab poetry and to the troubadours, but even there it is the man who longs and the woman who is unattainable.

These three exceptional features which Rabin attributed to the Song of Songs he found also in another body of ancient poetry, in the Sangam poetry of the Tamils. In three samples, chosen from the Golden Anthology of Ancient Tamil Literature by Nalladai R. Balakrishna Mudaliar, Rabin stressed the common theme of women in love expressing longing for the object of their affection, for their betrothed or for men with whom they have fallen in love, sometimes without the men even being aware of their love. The cause of the separation is rarely stated in the poem itself, but this is rooted in the Tamil social system and code of honor in which the man must acquire wealth or glory, or fulfill some duty to his feudal lord or to his people, and thus marriage is delayed. There is conflict between the man's world and the woman's and her desire to have her man with her. This conflict is poignantly expressed in one of the poems cited (Rabin, 212) in which a young woman whose beloved has left her in search of wealth complains: I did his manhood wrong by assuming that he would not part from me. Likewise he did my womanhood wrong by thinking that I would not languish at being separated from him. As a result of the tussle between two such great fortitudes of ours, my languishing heart whirls inagony, like suffering caused by the bite of a cobra.

In the Tamil poems the lovelorn maiden speaks to her confidante and discusses her problems with her mother, as the maiden of the Song of Songs appeals to the Jerusalem maids and mentions her mother and her lover's mother; but neither in the Tamil poems nor the Song of Songs is there mention of the maiden's father. In Rabin's view the world of men is represented by "King Solomon," surrounded by his soldiers, afraid of the night (3:7-8), with many wives and concubines (6:8), and engaged in economic enterprises (8:11). Significantly, however, according to Rabin (p. 213), Solomon's values seem to be mentioned only to be refuted or ridiculed: "his military power is worth less than the crown his mother (!) put on him on his wedding day; the queens and concubines have to concede first rank to the heroine of the Song; and she disdainfully tells Solomon (viii 12) to keep his money."

Since the Sangam poetry is the only source of information for the period with which it deals, Rabin plausibly surmised that the recurring theme of young men leaving home to seek fortune and fame, leaving their women to languish, corresponded to reality, i.e. the theme of longing and yearning of the frustrated women grew out of conditions of the society which produced these poems. Accordingly, the cause for the lover's absence need not be explicitly mentioned in the Tamil poems and is only intimated in elaborate symbolic language. Similarly, Rabin finds hints of the nonavailability of the lover in the Song of Songs. The references to fleeing shadows in 2:17, 4:6-8, and 8:14 Rabin takes to mean winter time when the shadows grow long. The invitation to the bride to come from Lebanon, from the peaks of Amana, Senir, and Hermon in 4:6-8 means merely that the lover suggests that she think of him when he traverses those places. The dream like quality of these verses need not, inRabin's view, prevent us from extracting the hard information they contain. The crossing of mountains on which or beyond which are myrrh, incense, and perfumes all lead to South Arabia, the land of myrrh and incense. Thus the young man was absent on a caravan trip. Even though he did not have to traverse Amana or Hermon to reach Jerusalem from any direction, he did have to traverse mountains on the trip and in South Arabia he had to pass mountain roads between steep crags ("cleft mountains") and it was on the slopes of such mountains that the aromatic woods grew ("mountains of perfume"). Coming from South Arabia, however, one had to cross Mount Scopus, "the mountain of those who look out," from which it is possible to see a caravan approaching at a considerable distance. In 3:6 "Who is she that is coming up from the desert, like pillars of smoke, perfumed with myrrh and incense, and all the powders of the perfume merchant?" is taken to refer to the caravan, the unexpressed word for "caravan" sayyarah, being feminine (Rabin, 214 and 219n29). "The dust raised by the caravan rises like smoke from a fire,but the sight of the smoke also raises the association of the scent a caravan spreads around it as it halts in the market and unpacks its wares."

The enigmatic passage 1:7-8 Rabin also related to a camel caravan despite the pastoral terminology. Rabin's theory encounters difficulty with the repeated use of the verb r'y, "pasture," and its participle, "pastor, shepherd" in view of which commentators commonly regard the Song as a pastoral idyl. His solution is to suggest that the term may have some technical meaning connected with the management of camels.

The list of rare and expensive spices in 4:12-14 reads so much like the bill of goods of a South Arabian caravan merchant that Rabin is tempted to believe that the author put it in as a clue.

Be it what it may, it provides the atmosphere of a period when Indian goods like spikenard, curcuma, and cinnamon, as well as South Arabian goods like incense and myrrh, passed through Judaea in a steady flow of trade. This can hardly relate to the Hellenistic period, when Indian goods were carried by ship and did not pass through Palestine: it sets the Song of Songs squarely in the First Temple period (Rabin,215).

As for the argument that the Song contains linguistic forms indicating a date in the Hellenistic period, Rabin points out that the alleged Greek origins of 'appiryon in 3:9 and talpiyyot in 4:4, the former word supposedly related to phoreion, "sedan chair," and the latter to telopia, "looking into the distance,"are dubious.

The phonetic similarity between the Greek and Hebrew words is somewhat vague, and this writer considers both attributions to be unlikely, but even acceptance of these words as Greek does not necessitate a late dating for the Song of Songs, since Mycenaean Greek antedates the Exodus. Neither word occurs elsewhere in the Bible, so that we cannot say whether in Hebrew itself these words were late. In contrast to this, pardes "garden, plantation," occurs, apart from 4:13, only in Nehemiah 2:8, where the Persian king's "keeper of the pardes" delivers wood for building, and in Ecclesiastes 2:5 next to "gardens." The word is generally agreed to be Persian, though the ancient Persian original is not quite clear. If the word is really of Persian origin, it would necessitate post-exilic dating. It seems to me, however, that this word, to which also Greek paradeisos belongs, maybe of different origin.

[...]

Rabin's summation of his view of the Song of Songs is of such interest and significance as to warrant citation of his concluding paragraphs (pp.216f):

It is thus possible to suggest that the Song of Songs was written in the heyday of Judaean trade with South Arabia and beyond (and this may include the lifetime of King Solomon) by someone who had himself travelled to South Arabia and to South India and had there become acquainted with Tamil poetry. He took over one of its recurrent themes, as well as certain stylistic features. The literary form of developing a theme by dialogue could have been familiar to this man from Babylonian-Assyrian sources (where it is frequent) and Egyptian literature (where it is rare). He was thus prepared by his experience for making a decisive departure from the Tamil practice by building what in Sangam poetry were short dialogue poems into a long work, though we may possibly discern in the Song of Songs shorter units more resembling the Tamil pieces. Instead of the vague causes for separation underlying the moods expressed in Tamil poetry, he chose an experience familiar to him and presumably common enough to be recognized by his public, the long absences of young men on commercial expeditions. I think that so far our theory is justified by the interpretations we have put forward for various details in the text of the Song of Songs. In asking what were the motives and intentions of our author in writing this poem, we must needs move into the sphere of speculation. He might, ofcourse, have been moved by witnessing the suffering of a young woman pining for her lover or husband, and got the idea of writing up this experience by learning that Tamil poets were currently dealing with the same theme. But I think we are ascribing to our author too modern an out look on literature. In the light of what we know of the intellectual climate of ancient Israel, it is more probable that he had in mind a contribution to religious or wisdom literature, in other words that he planned his work as an allegory for the pining of the people of Israel, or perhaps of the human soul, for God. He saw the erotic longing of the maiden as a simile for the need of man for God. In this he expressed by a different simile a sentiment found, for instance, in Psalm 42:24: "Like a hind that craves for brooks of water, so my soul craves for thee, O God. My soul is a thirst for God, the living god: when shall I come and show myself before the face of God? My tears are to me instead of food by day and by night, when they say to me day by day: Where is your god?" This religious attitude seems to be typical of those psalms that are now generally ascribed to the First Temple period, and, as far as I am aware, has no clear parallel in the later periods to which the Song of Songs is usually ascribed.

Rabin considered the possibility of moving a step further in speculation about Indian influence.

In Indian legend love of human women for gods, particularly Krishna, is found as a theme. Tamil legend, in particular, has amongst its best known items the story of a young village girl who loved Krishna so much that in her erotic moods she adorned herself for him with the flower-chains prepared for offering to the god's statue. When this was noticed, and she was upbraided by her father, she was taken by Krishna into heaven. Expressions of intensive love for the god are a prominent feature of mediaeval Tamil Shaivite poetry. The use of such themes to express the relation of man to god may thus have been familiar to Indians also in more ancient times, and our hypothetical Judaean poet could have been aware of it. Thus the use of the genre of love poetry of this kind for the expression of religious longing may itself have been borrowed from India.

Rabin's provocative article came to the writer's attention after most of the present study had been written. It is of particular interest in the light of other Indian affinities of the Song adduced elsewhere in this commentary.

pg 27-33, Song of Songs (commentary) by Marvin Pope

#cipher talk#song of songs#Judaism#This book came up in my Anat research while trying to see what academia currently makes of the theory she's connected to Kali#So this is interesting for that#But I think Rabins theory needs more support just because. Sangam literature to my understanding doesn't date to be contemporary to#The first temple period???#I also skimmed ahead on Pope's own discussion of the Anat-Kali connection and its a bit. Outdated#There was something about primidorial goddess figures or whatever but this book was published in the 60s#Rabin also has a dedicated paper just talking about the words he believes are of Tamil origin in Hebrew and how this connects to trade in#The 1st millennium B.C.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pls don’t ask “ you put Nivin Pauly as you in the image , so do you think you look as good as Nivin Pauly? “ :))))) Everyone knows it’s a logic mistake

#india#tamilnadu#chennai#desi tumblr#desiblr#desi#desi teen#indian cinema#desi core#desi tag#desi life#words from my inner soul#being desi#desi shit posting#desi academia#dark academia#mollywood#kollywood#tamil cinema#malayalam cinema#nivinpauly#nazriya#actually adhd#adhd brain#adhd things#adhd dreams#personal#personal blog

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

ஓ வரிசை சொற்கள் | O varisai sorkal #ஓவரிசை #ஓ #shortstamil #trending

#youtube#shorts#shorts tamil#tamil#o varisai sorkal#tamil words#ஓ வரிசை சொற்கள்#ஓ#ஓவரிசை#O#Ovarisai#Ovarisaisorkal

0 notes

Text

❤️ அவளும் நானும் ❤️அவனும் நானும் ❤️

Customized Tshirt collection

Call us:9750597508

#avalumnanum#avanum nanum#couples collection#couples tshirt#tamil quotes#tamil words#couples gifts#couple forever#couples shop online#avalumnanumsong#customisedtshirts🖤#cottontshirts#tshirtfashion#tshirts#salé#tshirtsonline#music#yolo#yoloshop#yolofashionfactory

0 notes

Text

…. MY OCS ……

#MARK MY WORDS. IM GONNA MAKE A COMIC FOR THEM.#I EVEN GAVE THEM NAMES AND A PERSONALITY#GASP#i imagine their story to be set in a world where it feels like it’s just the two of them and dreamy ghosts and spirits that they have#adventures with 😭 and they fall in LOVE WAAAAHHHHSKCJDK#oviya is tamil and asta is from iceland !#the location their story is set in is an imaginary place tho so i guess you can say they are tamil and icelandic inspired :)#you can talk to me abt them .. if you like … KJSDKDJSKD

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

ratchasa maamaney // ponniyin selvan - 1

#ponniyin selvan - 1#PS-1#trisha#karthi#trisha krishnan#sobhita dhulipala#mani ratnam#tamil cinema#kollywood#karthi and trisha in this song... no words only love <3#ccreates

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Save your people and bless your inheritance. Psalms 28:9

தேவரீர் உமது ஜனத்தை இரட்சித்து, உமது சுதந்

தரத்தை ஆசீர்வதியும். ���ங்கீதம் 28:9

#august #independenceday #india #happyindependenceday #indian #jaihind #freedom #independence #independencedayindia #indianarmy #instagram #love #bharat #indianflag #happy #indianindependenceday #thofjuly #patriotic #photography #thaugust #instagood #follow #like #maharashtra #trending #mumbai #delhi #flag #thindependenceday #army

#independence day bible#jesus#word of god#india#independence day#christmas#christianity#new year#independent artist#independent music#independent roleplay#independent rp#tamil bible#verse of the day#daily bible verse#indian#india love#india westbrooks#delhi#karnataka#punjab

2 notes

·

View notes