#textualists

Text

Funny how SCOTUS “originalists” ignore this history

Benjamin Franklin is revered in history for his fixation on inventing practical ways to make everyday life easier. He was a prolific inventor and author, and spent his life tinkering and writing to share his knowledge with the masses.

One of the more surprising areas Franklin wanted to demystify for the average American? At-home abortions.

Molly Farrell is an associate professor of English at the Ohio State University and studies early American literature. She authored a recent Slate article that suggests Franklin’s role in facilitating at-home abortions all started with a popular British math textbook.

Titled The Instructor and written by George Fisher, which Farrell said was a pseudonym, the textbook was a catch-all manual that included plenty of useful information for the average person. It had the alphabet, basic arithmetic, recipes, and farriery (which is hoof care for horses). At the time, books were very expensive, and a general manual like this one was a practical choice for many families.

Franklin saw the value of this book, and decided to create an updated version for residents of the U.S, telling readers his goal was to make the text “more immediately useful to Americans.” This included updating city names, adding Colonial history, and other minor tweaks.

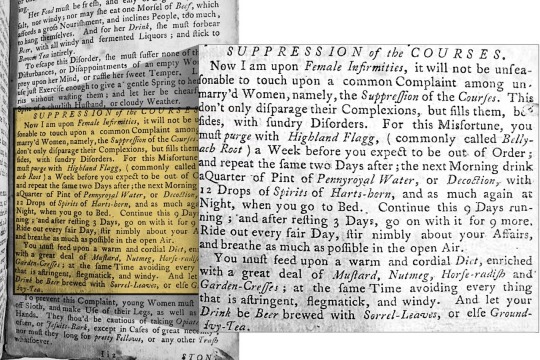

But as Farrell describes, the most significant change in the book was swapping out a section that included a medical textbook from London, with a Virginia medical handbook from 1734 called Every Man His Own Doctor: The Poor Planter’s Physician.

This medical handbook provided home remedies for a variety of ailments, allowing people to handle their more minor illnesses at home, like a fever or gout. One entry, however, was “for the suppression of the courses”, which Farrell discovered meant a missed menstrual period.

“The book starts to prescribe basically all of the best-known herbal abortifacients and contraceptives that were circulating at the time,” Farrell said. “It's just sort of a greatest hits of what 18th-century herbalists would have given a woman who wanted to end a pregnancy early.”

“It's very explicit, very detailed, also very accurate for the time in terms of what was known ... for how to end a pregnancy pretty early on.”

Including this information in a widely circulated guide for everyday life bears a significance to today’s heated debate over access to abortion and contraception in the United States. In particular, the leaked Supreme Court opinion that would overturn Roe v. Wade and states that “a right to abortion is not deeply rooted in the nation's histories and traditions.”

Farrell said the book was immensely popular, and she did not find any evidence of objections to the inclusion of the section.

“It didn't really bother anybody that a typical instructional manual could include material like this,”she said. “It just wasn't something to be remarked upon. It was just a part of everyday life.”

(continue reading) more ←

#politics#abortion#ben franklin#american history#scotus#textualists#originalists#roe v wade#mifepristone#abortifacients#reproductive rights#bodily autonomy#reproductive justice#healthcare#home abortions#for the suppression of the courses#every man his own doctor the poor planters physician#every man his own doctor

190 notes

·

View notes

Note

Happy New Year! May I request a Fugo character analysis?

You may have seen this story in the news about a student in Virginia who shot his teacher a couple weeks ago. Not an uncommon story in the U.S. tragically, but what made this one notable was the student was 6 years old. I read another story a month or so prior about a 10 year old boy who killed his mom over a video game console or something.

Why do I bring these up?

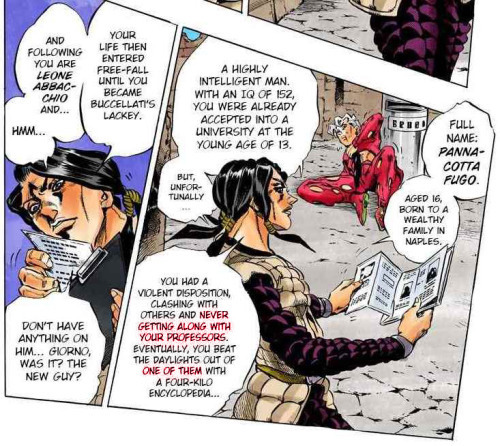

It's hard to do a Fugo analysis without also discussing some of the more popular opinions about him. I saw a post talking about Fugo a while ago that said something like, children aren't just angry, there must be trauma causing it. But that is simply not true. I see so many analyses that make excuses for Fugo being an argumentative, violent little shit in favor of this soft misunderstood boy he supposedly is on the inside and like?? No. Pannacotta Fugo is an angry kid. He has a rage inside of him that is so intrinsic it manifests itself in the physical embodiment of his soul. I noted here that I think Fugo is a stronger character without the plot device of a traumatic event that justifies his anger. It's a lot harder for us to excuse or explain away harmful behaviors in ourselves and each other if we don't have a "reason" for it. Some people just are angry. They can work on it to be more socially adapted, but that's how their brains are. That's how Fugo is. And that's important, because Fugo's life is dictated by his anger.

In the manga, Fugo beats his professor half to death unprovoked. It's an event that ruins his life - and he can't blame anybody but himself. This is all critical to his character development. When Fugo gets to the mafia, he encounters for the first time in his life authority figures who he not only respects but trusts. His anger is still a problem, but he has internal motivation to keep it in check - and frankly, external motivation too, because if Fugo can't make it work in Passione, he's probably as good as dead. So while he has entered a world that actually values violence and anger, Fugo learns that he can't just go nuts and attack everyone who looks at him funny. He learns to control his anger, now that it comes in the form of a stand that can murder everyone including himself.

Fugo matures in the gang, and imo that makes it all the more tragic when everything falls apart.

#I've been a strict textualist lately I know#but if I was gonna write an essay for English class on fugo this is the thread I would pull#pannacotta fugo#jjba#vento aureo#answered ask#anonymous#spam my askbox

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sexo lesbico con la puta de mi hermanastra - Porno en Español

Rico Strong Vs Kapri Styles

Casadas sedentas por rola batendo uma siririca

Reality Kings – Pint-Sized Cutie Yumi Sin Sure Knows How To Have Fun With A Big Dick

Sexy brunette lesbian sluts Charlotte Sartre, Kristy Black insert black sex ball in their ass

Hung Latino homo tugs his hairy dick and sprays big load

Borracha se deja follar

Fat ass blonde latina PAWG with giant boobs gets fucked

Teen girls stripping at party first time Mommy Loves Movie Day

INDIAN WOMEN SEDUCED TO FUCK BIGass MILF BHABI

#parotoid#Teria#beknottedness#boastings#revitalized#cornmeal#fernandinite#undaggled#misplays#almendro#incalendared#wabby#beatably#Vendelinus#balldom#upstick#jaloused#attends#preengineering#textualist

1 note

·

View note

Text

i love constitutional law podcasts cus its like a handful of academics talking who all despise each others views but but theyre debating and joking and talking like thats how its supposed to be

#and its also funny when its like. a guy who golfed his way up the ranks of the federalist society who uses ''textualist'' and#''originalist'' as synonyms. versus a woman who put herself through harvard law waiting tables whos coming after him with a butter knife#amanda.doc

0 notes

Text

You can't say you're a textualist and that 1.) the only rights are those explicitly stated in the constitution and that 2.) the only powers of the government are those explicitly stated in the constitution, and then go on and declare something constitutional or unconstitutional.

If we only have the rights explicitly listed and the government only has the powers explicitly listed, then the Supreme Court of the United States of America does not have the power to declare something constitutional or unconstitutional.

Judicial Review is not found anywhere within the text of the constitution.

#Supreme Court of the United States#SCOTUS#American politics#textualists are honestly so dense#the very thing that gives you the ability#to interpret the constitution#would not be a power under textualism#But they would honestly go this route#because then it'd allow everything#from Slavery#to child labor laws#to environmental protection laws#to work place safety laws#to marriage#to sex#to go 'back to the states'#and then we'll see#some states with radioactive water#and children losing hands in shirt factories#and people being dragged through the street for being gay#and other states#where workers work 4 days instead of all 7#and children get to go to school#and gay people hold hands in public#Like... WHAT THE ACTUAL FUCK

1 note

·

View note

Text

Not commenting on the broader decision/opinions (because it's over 200 pages and I haven't read them all thoroughly, and because I try not to pontificate) but I will say this, Thomas has a lot of nerve to complain or criticize that Substantive Due Process "exalts judges at the expense of the People from whom they derive their authority" when all but I think 2 quotes that he cites are his own opinions, most of which are dissents with no binding authority.

#lawblr#Opinion#Justice Clarence Thomas#he really really hates substantive due process as a concept#fucking textualist

1 note

·

View note

Text

Federalist Society malware strikes again.

The bogus textualists & originalists are suddenly making up dictatorial powers out of thin air to protect criminal Trump, their vehicle to power.

Turns out their constitutional interpretations were just fraudulent justifications for their obvious power grabs & rights violations.

360 notes

·

View notes

Text

Having faced serious criticism for his ethics, actual US Supreme Court member Samuel Alito has recently insisted that Congress has "no authority" to impose ethics or other regulations on the Supreme Court.

To which I retort, Article III, Section 2 of the United States Constituton: "the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make."

Samuel Alito is an actual sitting Justice on the US Supreme Court, a position he has held for almost 18 years. He is termed a "pragmatic textualist originalist" in his approach. Apparently he cannot read. Which explains a lot about his rulings.

355 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being Perpetually at the Mercy of the Arbitrary Negligence of the State is a Punishment

At the moment, we're seeing two somewhat orthogonal trends developing in conservative legal jurisprudence, both lawless, but in distinctive ways.

The first is an increasing indifference to textualism -- being perfectly happy to manipulate or flatly ignore statutory or constitutional language in order to achieve desired results. Yesterday's Clean Water Act ruling, where the Court held 5-4 that "adjacent" doesn't mean "adjacent" because, well, they don't want it to, is a prominent example. The "major questions" doctrine is another, including the invalidation of OSHA's COVID vaccine-or-test mandate despite the fact that it fell cleanly into the clear statutory language, is another. The Court's recent voting rights jurisprudence, featuring Shelby County's entirely-invented "equal sovereignty of the states" rule, is another. The Court's recent Second Amendment jurisprudence, which has functionally decided the first half of the Second Amendment's text may as well not exist, is a yet another.

The second, by contrast, is a sort of hyper-literal textualism that zooms in so tightly on individual words that it ends up blitzing past how people actually read texts. The opinion striking down mask mandates on planes is one example here; some of the opinions striking down the eviction moratorium fit as well. Though styled as "textualism", this sort of analysis really is a dangerous confluence of putative textualists being bad at reading texts.

Slotting into the latter category is a concurring opinion by 11th Circuit Judge Kevin Newsom in Wade v. McDade, arguing that the Eighth Amendment does not forbid any level of "negligent" treatment of prisoners by prison staff -- not negligent, not gross negligence, not even criminal recklessness. Judge Newsom's argument is deceptively simple: the Eighth Amendment forbids cruel and unusual punishments. But a punishment, he says, can by definition only be imposed intentionally. There's no such thing as a non-intentional punishment. And negligence, in all of its species, is something less than intentional. Hence:

The undeniable linguistic fact that the term “punishment” entails an intentionality element would seem to preclude any legal standard that imposes Eighth Amendment liability for unintentional conduct, no matter how negligent—whether it be only “mere[ly]” so or even “gross[ly]” so.... So on a plain reading, the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause applies only to penalties that are imposed intentionally and purposefully.

At one level, I appreciate Judge Newsom for saying the quiet part out loud here, because normally I'd spend time pointing out that Judge Newsom's position would warrant even the most grotesque acts of wanton disregard for the lives and wellbeing of prisoners. But Judge Newsom is quite happy to endorse (further) converting our prison system into a miniature gulag archipelago, so I guess I can skip that part and move to the textual question: is Judge Newsom's interpretation an "undeniable" inference from the term "punishment"?

And the answer, I think, is clearly "no".

At the outset of his opinion, Judge Newsom analogizes the negligent treatment of prisoners to that of parents and children: "Just as a parent can’t accidently punish his or her child, a prison official can’t accidentally—or even recklessly—'punish[]' an inmate." But in law, "accidental" and "intentional" are not an exhaustive binary. The whole purpose of the negligence and recklessness categories is to account for cases that lie between the pure accident and the specifically envisioned and desired consequence. And that makes sense, because while law contains different levels of "intent", legal fact patterns nearly always blend several of them together.

Take a case where a speeding driver strikes a pedestrian with his car. Did the driver act "intentionally"? On one level, he was likely intentionally speeding (his foot wasn't literally glued to the gas pedal). On another level, he likely did not intend to hit the pedestrian (he did not seek to mow him down). Negligence captures the interstitial position where the driver intentionally acted in a fashion which foreseeably placed the pedestrian in danger (even if converting the danger into reality was not the driver's motivation). In this, negligence is very different from the pure accident not because it lacks intention, but precisely because of its intentionality.

Swap back to punishment. Imagine a more pre-modern society where we outsource punishment to private actors. I catch you stealing tools from my garage. As a consequence, I strip you of your clothes, take all the possessions you have on you (to make sure you have nothing you could attack me with), and drop you off in the middle of the woods without food or water which I can't be bothered to acquire for you, safely away from my house. You tell me "my pills are in my bag; if I don't take them each evening I might die!" I say "I don't care if you live or die. Oh, and watch out for the forest-dwellers -- they aren't always friendly." You do, in fact, have a seizure overnight and die. Are the actions I took "punishing" you?

Plainly, it seems the answer is yes. And this is so even if I genuinely was apathetic to whether you lived or died. Like the driver striking the pedestrian, my conduct is a mix of the purely intentional (I took your possessions, I dropped you off in the woods) and negligent/reckless (I do not care whether you have a stroke, I do not care if the forest-dwellers attack you). Being intentionally placed in a position where one's custodians do not care whether you live or die is obviously a punishment. Indeed, the fact that it's a "punishment" is the only thing that distinguishes it from pure sadism, abuse, or kidnapping. The fact that the seizure was not specifically intended doesn't change the fact that what happened to you in no way could be described as an "accident". It was the result of intentional actions, and the reason I acted in the way that I did -- with reckless disregard for your life or safety -- was very much tied to my desire to punish you.

In most prison litigation cases, there is similar "intent". The failure to, e.g., give a prisoner necessary medication isn't a wholly-accidental whoopsie-doodle (and if it is, then there isn't even negligence). It is an intentional choice. Indeed, a large part of what prison is, and what makes it such a terrifying prospect, is that it is a place the state sends you where the people who have control of your life do not and perhaps need not care if you live or die. Everything about that is intentional. Or put another way, the pervasive, heartless lack of intention is the intention -- being placed in such a situation is entirely the product of intentional choices at every step of the process.

There's a lot to dislike about the "deliberate indifference" standard which has taken over prison abuse litigation, but one thing it gets right is that indifference is absolutely a choice, not an accident. To fail to treat a person in your custody with requisite care is a choice, and it doesn't stop being a choice just because its foreseeable consequences were not expressly desired.

So what makes Judge Newsom go astray here? He seems to think we should chop up "punishment" into each potential negative experience one might have in prison. Being locked up, and being restricted from the yard, and being deprived of medication, and being placed in solitary, and being put into a cellblock with white supremacists liable to stab you -- each of these are separate (potential) "punishments" whose status as a "punishment" must be assessed atomistically. But this approach defies common sense. When someone is sentenced to prison for a crime, we don't think of it as a loose cluster of twenty or so discrete "punishments". It's one punishment. The punishment is being a prisoner and being subjected to the prison experience. Everything that happens in prison is part of the overall context of being punished. There is no need to parcel out individual moments and ask "but is this particular action a separate punishment", any more than we need to ask whether swinging bats in the on-deck circle or jogging out into the outfield is part of "playing a baseball game." It's all part of the game, and the hyper-zoomed-in focus on each discrete moment misses the forest for the trees.

In other words, while it may be true that something must be a "punishment" to fall under the auspices of the Eighth Amendment, all prisoners by definition are being punished. They pass that threshold categorically; none of them have been placed in jail by accident. At that point, the relevant question is whether the set of challenged actions or behaviors or what have you suffices to make that punishment into a "cruel and unusual" one. And certainly, being put in an Arkham City terrordome should qualify even (especially!) if the overseers assiduously do not care if you live or die. Perpetual, ongoing, systematic negligence (to say nothing of recklessness) towards persons who are helpless and in your care is one of the cruelest acts imaginable. Where that is part of the punishment, the punishment is cruel and unusual.

Judge Newsom concludes his opinion with the following:

Maybe it makes sense to hold prison officials liable for negligently or recklessly denying inmates appropriate medical care. Maybe not. But any such liability, should we choose to recognize it, must find a home somewhere other than the Eighth Amendment. We—by which I mean the courts generally—have been ignoring that provision’s text long enough. Whether we like it or not, the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause applies, as its moniker suggests, only to “punishments.” And whether we like it or not, “punishment[]” occurs only when a government official acts intentionally and with a specific purpose to discipline or deter.

This "whether we like or not" language is reminiscent of my Sadomasochistic Judging article. Judge Newsom seems to recognize the cruelty inherent in his position. But he leverages that cruelty into an argument for textual fidelity; the avoidance of cruelty is the hint that his colleagues have been led astray from the strictures of law. As I've demonstrated above, this isn't true; the text does not demand the cruelty Judge Newsom ascribes to it. But the pleasure of the pain of causing pain is too tempting to pass up. It's not good textualism that's motivating Judge Newsom. It's the ecstasy of bad textualism leading to bad results, whose badness is paradoxically metabolized as the purest and most faithful instantiation of textual loyalty.

via The Debate Link https://ift.tt/JxhXtDy

110 notes

·

View notes

Note

...what exactly is the correct, good faith description of how common law constitutional systems work, then? i had conservative parents where extremely literal interpretation of the constitution was always assumed - never really got any perspective on living constitutionalism than that it was always just vague hogwash to justify doing whatever the speaker's exact policy preferences are. i understand that originalism/textualism as used are exactly the same, sure, but that's why i thought the only recourse was to dispense with constitutionalism and even the idea of "rights" altogether and go with a hobbes/schmitt (yes i know he's a nazi) bent. this isolates me from most other politics people on the internet a great deal, obviously! but if there's actually a case for living constitutionalism that doesn't reduce to "everything i want is always mandatory, everything my opponents want is always illegal" that can convince me that'd be great!

Originalism and textualism are not the same thing.

Originalism is the legal philosophy that the meaning of a law is based on the intent of the drafters of the law. In the U.S., this is actually not so hard a problem, because the Constitution was drafted in the 1780s, there was a big ratification debate which involved a lot of the people who participated in the drafting, and they made their own understanding of the text quite clear. Subsequent amendments were drafted even later, and like laws drafted by Congress, there are records of congressional debates and the like in which lawmakers lay out their stances very clearly.

Now, the problem with originalism as a legal philosophy is that you have to actually be good at historical research to apply it correctly. And if you are any good at historical research, and do not arbitrarily cherry-pick citations, you will unfortunately find that a lot of the dogmas of the conservative legal movement are actually not in evidence in the historical debates around the Constitution, its amendments, and significant U.S. statute laws. For this reason, among others, later conservative legal scholars have tried to make textualism a thing.

Textualism is the legal philosophy that the meaning of a law is based on the commonly understood meaning of the law at the time it was adopted. This is a weird approach! Like, I don't know much about (say) customs law, which is a complicated subject; if I tried to apply a customs law adopted in 2024 I would very probably fuck it up at some point. Even a highly trained criminal attorney or intellectual property lawyer might easily do so--the legal profession is big, and requires a lot of specialization! So why do non-expert opinions matter? And if expert opinions are what we are after, who is a better authority than the people who actually drafted a law?

Nonetheless, textualism is a highly motivated approach at avoiding the limits of originalism, and the key to applying textualism is to do your historical research even worse than if you were trying to do originalism. For example, D.C. v Heller (2008) found that the 2nd amendment protected an individual right to bear arms; but this is a terrible decision from both an originalist point of view and a textualist point of view, because we have lots of gun control legislation from much closer to the time the 2nd amendment was adopted in 1791 that would violate the 2nd amendment as interpreted in 2008; it is clear that the 2nd amendment was certainly not commonly understood at the time of its adoption to protect an individual right to bear arms, but was more about protecting the rights of states to raise and arm militias--which also happens to be consonant with a lot of the other historical evidence we have around why the 2nd amendment was adopted, and what the purpose of the Bill of Rights was, vis a vis the restraint of federal power against the states (cf. the Federalist Papers).

A big problem for any attempt at a purely deterministic, mechanistic application of law is that law is not a magical or mathematical formula with a single unambiguous meaning, because we create law through language, and that's not how human language works. Human language is not infinitely flexible, but it is equally not perfectly precise; it frequently admits ambiguity. And how we understand texts, and the values that are key to interpreting those texts, evolve over time: the U.S. Constitution clearly forbids "cruel and unusual punishment," but what is considered "cruel and unusual" in 2024 is very different from what was "cruel and unusual" in 1791. Should the literal meaning of 1791 prevail--in which case the law can only possibly regulate things which actually existed in 1791, and it's perfectly OK for the Feds to ransack your email without a warrant because it's not within your 'houses, papers, and effects'--or should the general principle which is shared between 1791 and 2024 prevail--in which case it's not insane to read the prohibition on "cruel and unusual punishment" as a prohibition on the death penalty if we come to understand the death penalty as cruel or unusual?

All texts require us to negotiate their meaning. This does not mean communication is impossible, or that a text can say anything you want it to mean. What it means is that ambiguity in communication is unavoidable. Law is an effective tool because it is a Schelling point for cooperation, which is what lets us build peaceful and ordered societies, and allows us to do politics without killing each other. Textualism and originalism not only deny the very inarguable fact of ambiguity in language, I think they work pretty hard against law being an actually useful Schelling point, and attempt to turn it into a brute exercise of power. Which is not good if you want a society to actually function!

Outside of originalism and textualism there are lots of different views on legal philosophy and they are complicated. Legal realism and legal positivism are two historically popular schools of thought. The general question of legal philosophy is called "jurisprudence," which is both thinking about what the law is and what it should be; there are literally whole textbooks on the subject. Law is complicated! There is a reason you can get advanced degrees in this stuff!

#i am not myself a lawyer#just an interested amateur#so anybody who has taken an actual jurisprudence class#feel free to weigh in

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

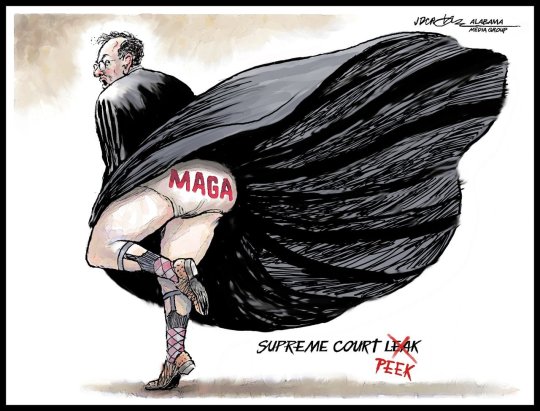

Alabama Media Group

* * * *

Alito’s gift to racist legislatures

May 24, 2024

ROBERT B. HUBBELL

From 1870 to 1965, Southern states resisted the mandate of the Civil War amendments granting and protecting the right of Black citizens to vote. After 95 years of resistance by former secessionist states, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, which required that redistricting decisions be “pre-cleared” by the Department of Justice. The preclearance requirement applied to states with a history of racially discriminatory voting practices.

Chief Justice John Roberts gutted the animating force of the Voting Rights Act in his opinion in Shelby County v. Holder (2013) by declaring that “our country has changed” and that racial gerrymandering “no longer characterizes” voting practices in the states subject to preclearance. (Of course, Roberts ignored the fact that the absence of racial gerrymandering was because of the preclearance requirement.) Roberts’ decision to end the preclearance requirement was a gift to racist state legislatures eager to return to the Jim Crow era.

Those legislatures wasted no time exploiting Roberts’ gift to the advantage of white voters. The legislatures drew congressional districts that effectively weighted white votes more heavily than Black votes. In the absence of the preclearance requirement, the only check on the power of racist legislators was litigation under the weakened provisions of the Voting Rights Act.

On Thursday, Justice Alito took another step in gutting the Voting Rights Act by inventing a “presumption of good faith” when legislatures with a history of racial discrimination draw new congressional boundaries. Like the earlier gift from John Roberts ending the preclearance requirement, Alito has also granted racist legislatures a gift—a presumption of good faith that will shield racial gerrymandering for generations to come. See Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP (05/23/2024).

In little more than a decade, the Supreme Court has turned history on its head: The Voting Rights Act required preclearance for states with a demonstrated history of racial discrimination in voting practices. Alito now grants those same legislatures a “presumption of good faith” even when the practical effect of their redistricting is to dilute the voting rights of Black citizens.

In bestowing racist legislatures with the presumption of good faith, Alito is advancing the twin causes of white Christian nationalism and insurrection symbolized by the “Appeal to Heaven” flag displayed over his beach house in 2023. Alito is, in short, in the vanguard of a hostile takeover of the US Constitution by white Christian nationalists. He is completing the work of the January 6 insurrectionists who beat law enforcement officers, defecated in the halls of the Capitol, and delayed a constitutionally mandated count of electoral ballots.

The reactionary majority on the Supreme Court is acting without restraint because they believe that Democrats do not have the courage and discipline required to impose reforms on the Court. The reactionary majority is not wrong in its assessment of the Democratic Party’s dithering and temporizing in the face of a constitutional assault that rivals the secession movement preceding the Civil War.

Either the 14th and 15th Amendments mean what they say, or they mean nothing. There is no “gray area” that shields “good faith” violations of their guarantees. The “presumption of good faith” invented by Alito has no more footing than a fairy tale. Alito and his fellow insurrectionists will not stop until Congress exercises its authority to enlarge the Court and circumscribe its jurisdiction—as expressly permitted by the Constitution. US Const. Art. III, Sec. 2, Cl. 2 (“The supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.”)

Alito claims to be an originalist and textualist. In inventing a presumption of good faith found nowhere in the Constitution, he has usurped the mantle of the Framers of the Civil Rights Amendments. He working to replace their vision of an egalitarian nation with a system of castes in which skin color and circumstances of birth determine which votes will be given the greatest weight.

But it gets worse. In a concurrence, Justice Thomas took the opportunity to criticize the 1954 holding in Brown v. Board of Education and suggest that the basis for that ruling is no longer valid. Thomas wrote, in part,

In doing so, the Court [in Brown v. Board of Education] took a boundless view of equitable remedies, describing equity as being “characterized by a practical flexibility in shaping its remedies and by a facility for adjusting and reconciling public and private needs. . . . Redistricting remedies rest on the same questionable understanding of equitable power. No court has explained where the power to draw a replacement map comes from, but all now assume it may be exercised as a matter of course.

The holding of the reactionary majority signals that they are coming for it all: Contraception, same-sex marriage, “inter-racial” marriage, and the application of the Bill of Rights to the states. The reactionary majority is emboldened by the milquetoast response of the Congress to Alito’s declaration that he is an insurrectionist and a Christian nationalist looking to establish a theocracy.

There is much more to this story, but my time is limited this evening. (We flew from LA to DC today.) I highly recommend the following, each of which addresses the central question in the Alexander case: When is racial gerrymandering permissible as an adjunct to partisan gerrymandering? Per Alito, racial gerrymandering is permissible as long as a legislature claims it was attempting to achieve partisan gerrymandering. See the following:

Dissent of Justice Kagan, in Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP.

In the majority’s version, all the deference that should go to the court’s factual findings for the plaintiffs instead goes to the losing defendant, because it is presumed to act in good faith. So the wrong side gets the benefit of the doubt: Any “possibility” that favors the State is treated as “dispositive.”

Ian Millhiser in Vox, Supreme Court Justice Sam Alito writes a love letter to gerrymandering.

On top of all of this, Alexander achieves another one of Alito’s longtime goals. Alito frequently disdains any allegation that a white lawmaker might have been motivated by racism, and he’s long sought to write a presumption of white racial innocence into the law.

Mark Joseph Stern in Slate, Clarence Thomas makes a full-throated case for racial gerrymandering.

And yet, as bad as Alito’s opinion was, it didn’t go far enough for Justice Clarence Thomas, who penned a solo concurrence demanding a radical move: The Supreme Court, he argued, should overrule every precedent that limits gerrymandering—including the landmark cases establishing “one person, one vote”—because it has no constitutional power to redraw maps in the first place.

We have remedies. We need only the courage and passion to pursue them:

Open an impeachment inquiry of Justices Alito and Thomas

Demand Alito’s recusal

Pressure John Roberts to recommend an investigation by the federal Judicial Conference

Expand the Court to dilute the death grip of the reactionary majority

Limit the Court’s jurisdiction as provided by Art. III, Sec. 2, Cl. 2

Democratic leaders have failed the American people by treating these offenses as political controversies over which Congress has no jurisdiction.

[Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter]

#corrupt SCOTUS#MAGA SCOTUS#Alito#Radical Republicans#Robert B. Hubbell#Robert B. Hubbell newsletter#Judicial activism

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because i hate myself (actually cause I saw a bumper sticker today that made me scream in pure rage) (and also cause like… because i need to be armed to the teeth with knowledge and facts because conservative right-wing family members love to parrot bullshit propaganda when not just being outright bigots🙄) I decided to take a read through the entire Wikipedia page concerning Trump’s 2024 run (and then I looked at his actual campaign website cause I hate myself more and wanted to see some of his actual rhetoric that was mentioned but not quoted) and it’s just like…

He fucking wants to appoint himself as god-king (wants to expand power of the executive (diminishing the separation of powers), turn govt civil employees status to ‘at will’ for firing, and to impose congressional term limits while also abolishing his own) and “root out” the “vermin” in this country (literal rhetoric he has used) and with this Court it probably won’t just go unchecked, but like I’m afraid it could be affirmatively endorsed using principles of originalism and ‘history and tradition’ (whose fucking version of history???? Huh???? Because it certainly wasn’t fucking mine when you overturned Roe in Dobbs) but in the fast and loose way that they like to, where sometimes they want to be textualist and sometimes they don’t.

Assuming he tries, I do think expansion of the executive might not get support from some of the conservative justices under principles of federalism which is— wrong math, right answer. But they 100% would justify his white Christian supremacist alloamatocisheteronormative patriarchal policies under originalism and ‘history and tradition’. As if letting the past guide the future isn’t a fucking BATSHIT thing to do. We learn the past to do BETTER in the future, not to fucking EMULATE it and use their standards to STAGNANT the lives of real people. EVEN THE FUCKING DRAFTERS OF THE GODDAMN CONSTITUTION KNEW THAT IN FUCKING 1787 SO WHY THE FUCK ARE WE STILL DOING THIS SHIT! But I digress from my originalism rant because this is a Presidential Campaign rant.

Like Trump literally said he wants to (and WILL BE) a dictator.

“He says, ‘You’re not going to be a dictator, are you?’. I said: ‘No, no, no, other than day one. We’re closing the border and we’re drilling, drilling, drilling. After that, I’m not a dictator.’”

“Baker today in the New York Times said that I want to be a dictator. I didn’t say that. I said I want to be a dictator for one day.”

*insert regina george* so you agree? You want to be a dictator? Pretty sure being one for “one day” is called establishing the dictatorship and suuure Jan im sure that it’ll stay limited in scope to the borders and drilling (as if that would fucking make it okay???) 🙄

And then the option on the ‘opposing’ side is Joe Biden, who, chief among his many faults, is aiding and supporting a genocide. The fact that he has no competition in primaries (literally only one other person is even trying) and will end up being the Democratic candidate has me so incensed and the fact that Joseph Biden is fucking painted as the ‘radical left’ by opposition is both objectively hilarious and just horrifying and dangerously (and probably intentionally) misleading so as to continue the shift of whatever “middle” exists to actually be further and further right wing.

There is not really a larger point here and I’m super not looking for discourse but if anyone is gonna try anyway— don’t bother me without a source.

Anyway I’m just fucking tired and fuck the electoral college and the fact that one of these two ancient men winning seems inevitable

#us govt#In case it’s not clear#I’m a leftist#us politics#usa#America#american politics#2024 elections#2024 presidential election#Donald trump#Joe Biden#potus#Supreme Court#FUCK ORIGINALISM#ALL MY HOMIES HATE ORIGINALISM#originalism#seriously i am not looking to debate you#you will not change my mind unless you have facts grounded in reality with a reasonable basis#trump#Biden#Fuck the electoral college#all my homies hate the electoral college#abolish the electoral college#let THE PEOPLE fucking decide#politics#leftist#political rant#rant about politics#rant#rant post

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The public already views the Supreme Court through a partisan lens, with Democrats expressing little confidence in the court and Republicans saying the opposite, and the question of whether Trump should be kept off the ballot has the potential to further polarize those views.”

Let’s take that statement a bit further and look at them individually. The conservatives call themselves textualists, strict constitutionalists, or originalists, meaning that they would read the law and its intent strictly as per its original meaning. So if they want to be consistent, and not look like partisan hacks, then they’ll rule in favor of Colorado and removal. So, will they be partisan or consistent?

Alito & Thomas are bought and paid for partisan shills. No chance either would ever vote to remove him. That’s two for Trump.

Roberts, Kavanaugh & Coney-Barrett were part of the legal team that put Bush in office. That’s why they’re sitting where they are today. They won’t shy from being partisan again if it comes to that, and Roberts is too skittish about controversy to call Trump ineligible. I could see Kavanaugh being thoughtful about it though, so let’s say that makes 2-1/2.

Gorsuch is in a weird spot. He has previously ruled that Colorado has the right (and duty) to remove unqualified candidates from the ballot, because Colorado law requires it. Congress has voted in the 2nd impeachment trial the Trump did organize an insurrection and he’s therefore unqualified. Gorsuch is one of the Justices most concerned about his legacy in the history books, so consistency might matter to him here. Let’s put him down for 50-50 as well, so 1/2 a vote.

We’re up to five. That means Trump is forced back onto the Colorado ballot.

I know less about the liberals, but it’s still possible one of them could vote with the conservatives here.

In sum? I don’t think there’s much chance here for the Justices to follow the strict textual reading of the Constitution that they claim they apply, and they’ll come up with a strange justification to rule in Trump’s favor, either 6-3 or 5-4.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

every once in a while, i feel a little bit annoyed with myself / question whether i can actually become an attorney . . .

. . . and then i remember that one time a big corporate attorney tried to ask me whether interracial marriage is actually legitimate (”like, does the constitution actually allow that? because i’m a textualist”) in a random bar, and then i grit my teeth and get back to studying because if that asshat can become an attorney, then surely. surely--

#caroline talks#literally as i'm putting together my outline about substantive due process right now . . .#thinking about the 14th amendment due process + equal protection clauses . . .#and realizing that oh yeah these two are separate#but wanting suddenly. so much more to dropkick that one guy.#anyways <333 i can't believe i literally smoked a cigarette with him tbh#just thinking about it i swear i can still taste the cigarette in my mouth and it makes me want to throw up lmao

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also: we know that the whole “states’ rights” argument is and always has been deeply rooted in racism, right?

During the original framing and drafting of the Constitution, the individual states were given so much power to, once again, finesse the question of slavery and whether the entire newly-formed United States of America should have the same policy about it. That gave a lot of wiggle room for individual state governments and legislatures to set their own laws, and the “federalist” approach promised that a central government would be relatively hands-off as far as such things went; the states were grouped together, but still operated largely as their own political and legal entities. During the Civil War, as it was always going to, the “states’ rights!!!” argument once more took center stage. Supposedly it wasn’t about slavery, it was about “states’ rights!” Of course, the fact that this was whether states had the right to continue slavery is one that is still conveniently overlooked by your average Confederate apologist today. And the fact that those even still exist, let alone have substantial political power, is a reflection on how deep and poisoned that white grievance is.

Anyway, my point is: by arguing that states should have the right to take away things the fascists don’t like (abortion), but shouldn’t have the right to take away things they DO like (guns), the current SCOTUS is demonstrating not just their wild hypocrisy, but the fact that the “states’ rights” argument has always been about preserving the institutional right to fascism. Some so-called strict textualist like Neil Gorsuch will look at the fact that the Constitution grants primary electoral-law power to state legislatures and go, “yeah, we should throw out every single precedent that has challenged or changed that!” Even though, as the pants-shittingly terrifying case Moore v. Harper that SCOTUS took yesterday demonstrates, the entire point of that lawsuit is to grant (Republican) state legislatures the right to straight-up override the popular vote and appointment of electors.... but only if a Democrat wins. Alito’s opinion in the North Carolina gerrymandering case makes it clear that he wants SCOTUS to have the option of striking down any state law they don’t like... which again, are those that stop Republicans from outright cheating, or don’t automatically and systematically advantage them. It’s not about a Return to What the Constitution Says (which is an utterly idiotic metric anyway, as if we should just use an eighteenth-century text uncritically and act as if nothing has changed in 250 years). It’s not intended to be applied evenly or for the benefit of both parties, especially with the theocratic fascist nightmare that now constitutes SCOTUS. The argument for “states’ rights” is translated as “we will support the states that implement right-wing fascism, and punish those that don’t.”

The argument for removing the influence of a so-called “tyrannical” federalism, and to “return power to the states,” essentially rests on a belief that the government doesn’t have any inherent right to legislate away fascism. According to the “states’ rights!” argument (which is never meant to encompass the rights of blue states) the central government doesn’t have the legal right to protect women, LGBTQ people, Black people, the environment, anyone who isn’t a mega-corporation, schoolchildren in class, Americans anywhere in public, etc etc., simply and primarily because the punishment and control of these groups are a key ideological tool of fascism. This is often presented in the favored American language of “freedom” -- it’s a free country, so why can’t states do whatever they want? And yet if the Republicans win Congressional majorities in November 2022, they WILL push for a national abortion ban, the overturn of gay marriage, and everything else, on the whole country, red and blue states alike. What, you might ask, happened to “states’ rights?” Well, yet again, it doesn’t count. The only “right” that states have is that of freely adopting theocratic fascism. If they don’t, it will be forced on them.

Likewise, SCOTUS is making this “states’ rights” argument in the full knowledge and intent to enable the transition from (ailing) democracy to full-blown authoritarianism. That’s why the conservatives’ next big legal goal is to get SCOTUS to declare the Establishment Clause -- separation of church and state -- illegal on a state-by-state basis, so each state can “have the choice” of just how much theocracy they can legally force down everyone’s throats. STATES’ RIGHTS!! scream its wingnut proponents. IT’S A FREE COUNTRY! And yet, again. Funnily enough, that only translates to freedom for them. Everyone else in that state, willingly or otherwise, will be subordinated to it.

Anyway. The “states’ rights” argument is and always has been about preserving the legal right to oppression and now, as the Republicans have been going full fascist as fast as possible, their nu-fascist Christian white supremacist power in as much of the USA as possible, whether or not that state actually wants it. The language of “freedom” is particularly pernicious here, since it means exactly the opposite. “Freedom to choose” is their big thing. Except, you might say. Isn’t that what you just took away from everyone else....?

Shh. We are at war with Eastasia. We have always been at war with Eastasia.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Courting Ridicule - When constitutionalism becomes comedy

Dr. Timothy Snyder January 8, 2024

I am concerned that the Supreme Court, in ruling on Trump's eligibility for office, will make itself ridiculous.

We stand on the threshold of comedy already.

A Supreme Court justice takes big gifts from people who have an interest in Court rulings. Morally shocking, but also ludicrous.

The Court responds by ignoring a fundamental principle of justice: that one cannot judge oneself. This is tragic, but also funny.

The wife of that justice supported the overthrow of Constitutional rule during an attempted coup. It’s hard to miss the humorous side of that.

She urged the president (through baffling texts to his chief of staff) to (among many other things) "release the Kraken." This is horrible in its totality, but hilarious in the detail.

She attended and helped organize the rally that became the assault on the Capitol on January 6th, 2020. And she helps run a for-profit consulting firmthat takes money from people who have cases before the Supreme Court.

In a Court wishing to maintain a veneer of seriousness, Clarence Thomas would recuse himself from cases where Ginni Thomas is making money and from cases concerning Trump's insurrection.

Thomas did recuse himself from a single case that touched on January 6th, when doing so did not matter. That’s distressing; but it’s also amusing to consider that he thought he was fooling anyone.

What is left for Supreme Court justices at this point is an overt commitment to legal theory. Most justices, Thomas included, are "originalists," and indicate that they are bound, in their rulings, by doctrines known as intentionalism or textualism.

In intentionalism, the Constitution is held to mean what its framers intended it to mean. In textualism, the Constitutionalism is held to mean what its plain language indicates. These views are what most justices want us to take seriously. It would help if the justices who propound these views would act consistently with them.

Court rulings favor big business and make it harder for people to vote. We are assured that this a side effect of intentionalist and textualist readings of the Constitution. It is mere coincidence, we are told, that these rulings align with the interests of the political forces who organized the justices' education, ascent, and appointment. Perhaps this is true. Perhaps it is coincidence. Perhaps textualism and intentionalism mean something.

Or perhaps it is all a sham. We are about to find out.

The Supreme Court is about to consider Anderson vs. Griswold, the Colorado Supreme Court ruling that Trump may not appear on a primary ballot.

This is a case made for a textualist or an intentionalist.

For a textualist, intentionalist, or originalist of any sort, Anderson vs. Griswoldis utterly simple. The text of Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution forbids insurrectionists such as Trump from holding office. The intentions of those who discussed and formulated Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment are similarly clear.

This is where the comic potential emerges. This Court is unlikely ever to hear again a case of such simplicity, in which the text and context of the Constitution so obviously demand an unambiguous verdict: to confirm the Colorado ruling.

If the Court does otherwise, it will look silly.

But three of our textualists and the intentionalists were appointed by Trump, and silliness seems to be the general expectation. The theory of Trump's lawyers, as one of them has actually said out loud, is that Supreme Court justices appointed by Trump belong to Trump.

The tittering has begun. Like an audience that sees the banana peel on the stage, commentators goad the justices towards the pratfall. It is widely proclaimed that the Court's decision rule should not be the Constitution, but instead the psychological state of Trump supporters.

“Maybe folks’ll be upset” would indeed be a funny way to decide a case.

Such a pitchfork ruling, a judgement based not on law but on guesses about the moods of strangers, would be as far from intentionalism and textualism as the justices could get. It is just the sort of thing that intentionalists and textualists say that they never do. Their heroic pose is that they must do just what the Constitution says, regardless of the consequences.

After a pitchfork ruling, the entire originalist pretence — that justices stand bravely apart from the moment and evaluate the text or context of the Constitution as they must — would dissolve.

The consequences of courting ridicule are, of course, very serious. Our form of government depends on a balance between the executive, the legislative, and the judicial branches. When such a government is toppled, it is usually by an executive who is able to dominate the other two branches. One way that an executive does so is by mocking the other two branches, portraying them as unnecessary and led by buffoons.

And so actual buffoonery helps no one. If Trump is left on the ballot in defiance of the Constitution by people who claim to be its protectors, he will not respect it or them. But the danger of constitutional comedy is general. It leaves the rule of law more vulnerable, and makes regime change more likely.

PS You might be wondering why you have not heard more about Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. This is because it is not generally taught in law schools. But what is taught or not taught in law schools, what is in fashion or not in fashion in a given moment, should be absolutely irrelevant to the textualists and the intentionalists. The wording of the Constitution itself is as clear as day.

© 2024 Timothy Snyder

2 notes

·

View notes