#thomas de cantimpré

Note

hello can i have some unicorns :)

Oooh, of course you can! Let me quickly look up some of my favorite sources...

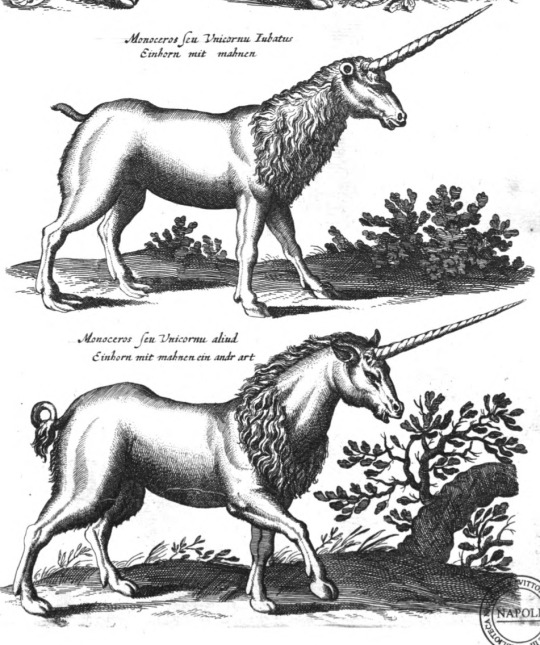

Thomas de Cantimpré has no less than 3 unicorns covered! That's 3 times the amount of unicorns! From top to bottom, you have the monoceros, the Indian onager, and the unicorn itself.

Albertus Magnus gives us this classic animal, looking somewhat heraldic.

This unicorn from the Ortus Sanitatis, though, is rather contemplative looking. And seems rather goaty too.

The rhinoceros (karkadan) from Middle Eastern manuscripts varies a lot, sometimes clearly a rhino and sometimes more fanciful. This version is from a copy of al-Qazwini.

Jonston covers around 9 different unicorns, some of which are horny in more ways than one! (Trust me. Look them up, I've posted them before). These ones look like standard maned unicorns.

Ambroise Paré had a lot to say about unicorns (and mummies, and the plague, and anything else vaguely related to public health). Here is the pirassoipi, a two-horned unicorn (a bicorn?) from Italy

And you know what? I've been sticking to vintage illustrations but here's Rudolf Freund's spectacular historically-accurate unicorn!

Stay tuned for more unicorn imagery!

#unicorns#monoceros#indian onager#bestiary#ambroise paré#thomas de cantimpré#john johnston#albertus magnus#ortus sanitatis#al-qazwini#karkadan#karkadann

368 notes

·

View notes

Text

cyclopes

illustration from a copy of thomas of cantimpré's "de natura rerum", flanders, c. 1475

source: Bruges, Bruges Public Library, Ms. 411, fol. 4r

465 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zitiron- a creature with the bottom half of a fish and the top half of a knight.

The zitiron only shows up in three sources that I can find- the Ortus Sanitatis (published in Germany 1491, author unknown), Van der Naturen Bloeme (early 14th c) by Flemish poet Jacob van Maerlant, and De natura rerum (1244 CE) by Flemish writer Thomas of Cantimpré. Van der Naturen Bloeme is actually just a Dutch translation of the Latin De natura rerum, so technically there's only two original sources. The only reason I mention both is that the original De natura rerum- which is sourced from a large number of works by philosophers and writers such as Aristotle, Pliny the Elder, St. Ambrose, Jacques de Vitry, and too many others to explore them all as original sources- doesn't have any illustrations and is in Latin, which I can't read, making it a personally useless source. But Van der Naturen Bloeme does have illustrations- the third image in this post is Jacob van Maerlant's interpretation of the zitiron I assume to be outlined in De natura rerum.

The only other original place that a zitiron can be found, according to the internet, is in the Ortus Sanitatis, a Latin natural history encyclopedia with no known author published in 1491 in Mainz, Germany. It has illustrations, the second image in this post is the author's interpretation. But again, I can't read Latin and it's hard to read the stylized text to put into google translate.

There is almost no information about the zitiron online, which is a shame because it's a really interesting figure. If you can read Latin or medieval Dutch I would LOVE to work together to place the origin of this mythological creature and learn more about it!

For the drawing, I wanted to honor Jacob van Maerlant and Thomas of Cantimpré's Flemish heritage. The helmet, chainmail, shield, and goedendag on the zitiron are representative of what the Flemish forces wore and used at the Battle of the Golden Spurs, a 1302 victory of the French that is a source of pride and celebrated every July 11th by the Flemish today.

TLDR: The zitiron is a little known creature from the Middle Ages or perhaps antiquity, with the bottom half of a fish and the top half of a knight. My drawing is inspired by the Flemish culture of two of the only writers to leave any information about the zitiron.

If you've got the time and can read Latin, could you take a look at the two Latin texts I mentioned? For the Ortus Sanitatis, I was able to flip through the whole thing and find the page that has the info on zitirons. It's on page 730 here- (x). But for De natura rerum, which you can access here (x), I have no idea where it could be. There's a translation project for it ongoing through Kalamazoo College, but I don't see anything relating to zitirons or relevant mythology on their page so far. And if you can miraculously read medieval Dutch, here's the link to the page on zitirons in Van der Naturen Bloeme (x).

#mermay#mermay 2023#long post#folklore#flemish folklore#european folklore#my art#zitiron#mermaid#thanks for reading this is a long one : )

228 notes

·

View notes

Note

scorpion in thomas of cantimpré's 'liber de natura rerum', bavaria, c. 1424. Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Pal. lat. 1066, fol. 132v

[Image ID: A bipedal creature with a grayish body and a tail. It kind of looks like a chicken in silhouette, but with tail and feet like a lizard. Its head is yellow rather than gray, and looks vaguely canine. At least if you had a dog who was bald, wrinkly, yellow, 100 years old, and in a bad mood about it.]

This is so extremely not a scorpion. If there hadn't been a couple of critters with this body plan in the original post, I would be completely floored by this one's existence. Even so, I'm still just kind of staring at it in confusion.

Like, let's be clear here, this is not what Mr. Of Cantimpre is describing in the text. He includes such items as:

A scorpion is a serpent, as Solinus says, which is said to have a charming and virgin-like face.

But it certainly has a poisonous sting in its knotted tail, with which it stings and infects any that approach it.

The scorpion is the only insect that has a tail, and arms, and a spike in the tail.

(I found a translation this time instead of fighting with the Latin -- this is from https://bestiary.ca/ . They admit that this is a machine translation with a human editor, so grain of salt, though.)

None of this is represented in the illustration. Like, Tommy Boy up there can't seem to decide whether this is a serpent or an insect (I'm going to assume the overly-flexible term worm is at fault in this case), but the animal pictured seems to be neither. Its tail is neither knotted nor spiked. You could maybe argue that those are arms. Not on board with the illustrator's interpretation of "charming and virgin-like face"... okay, I guess it's kind of ugly-cute, but that's a stretch.

Anyhow, points:

Small Scuttling Beaſtie? scale unclear, not enough legs, ✘

Pincers? ✘

Exoskeleton or Shell? ✘

Visible Stinger? ✘

Limbs? 2

Vibes... eh. It has charming aspects, but it has this bad-tempered expression on a face that I'm not sure how to react to. 3/5.

Total:

3.2 / 10

I have questions about the illustrator's tastes.

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

LJS 23 - De Natura Rerum

Do you want to pass your science class? Well, maybe Thomas of Cantimpré might help! This manuscript is one of the earliest known copies of a gathering from Books VII-XX of the De Natura Rerum, a big introduction to science. There are sections on fish, insects and invertebrates, trees, cosmology and astronomy, herbs, springs, gems, wind and clouds, the four elements, stars, and eclipses. It was written in Northern France or Flanders, ca. 1250-1275 CE.

Do you want to know more? Click here for additional information, here to see the facsimile, and here for the video orientation!

#de natura rerum#ljs 23#thomas of cantimpré#encyclopedia#medieval encyclopedia#13th century#animals#history of animals#van pelt library#university of pennsylvania#kislak center#sims#latin manuscript#ms

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

it’s world honey bee day post bonum universale de apibus by Thomas Cantimpré

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

wild unicorn

Thomas of Cantimpré, Liber de natura rerum, France ca. 1290

Valenciennes, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 320, fol. 71r

#unicorn#monoceros#bestiary#animals#medieval#art#medieval art#middle ages#13th century#book#manuscript

724 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Saint Christina Mirabilis (1150-1224) Virgin, mendicant, apostle of prayer of reparation, mystic – also known as Christina the Astonishing – Patronages – millers, people with mental disorders, mental health workers, mental health caregivers, professionals, psychiatrists, and therapists. St Christina was born to a peasant family in Belgium. She was orphaned as a child and raised by her two older sisters. When she was 21 she had what was believed to be a severe seizure and was pronounced dead. At her funeral she suddenly revived and levitated before the bewildered congregation. She said that during her coma she had been to heaven, hell and purgatory and had been given the option to either die and enter heaven, or return to earth to suffer and pray for the holy souls in purgatory. Many thought her to be possessed by demons or insane but many devout people recognised and vouched for her sincerity, obedience and sanctity. They believed, that she was a living witness to the pains that souls experience in purgatory, willingly suffering with them and for them. Christina the Astonishing is the patron of those with mental illness and disorders, mental health workers, psychiatrists, and therapists. Thomas of Cantimpré (1201–1272), then a canon regular who was a professor of theology, wrote a report eight years after her death, based on accounts of those who knew her. Cardinal Jacques de Vitry, who met with her, said that she would throw herself into burning furnaces and there suffered great tortures for extended times, uttering frightful cries, yet coming forth with no sign of burns upon her. In winter she would plunge into the frozen Meuse River for hours and even days and weeks at a time, all the while praying to God and imploring God’s mercy. She sometimes allowed herself to be carried by the currents downriver to a mill where the wheel “whirled her round in a manner frightful to behold”, yet she never suffered any dislocations or broken bones. She was chased by dogs which bit her without any bodily injury. Christina died at the Dominican Monastery of Saint Catherine in Sint-Truiden, of natural causes, aged 74. https://www.instagram.com/p/CgZAU2cugt9/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Mit der Erstellung eines solchen Buches, wie ich es beabsichtige, hoffe ich nicht nur, den Laien einen Zugang zum Wissen von der Natur, von der Welt zu ermöglichen, welches dann dem Leser das Verständnis der Bibel und anderer Werke erleichtern soll. Ich hoffe außerdem, dass die Menschen durch dieses christliche Wissen von der Welt, zur Gotteserkenntnis gelangen können. Denn die Welt, die ich beabsichtige abzubilden, ist Gottes Schöpfung.

Ich glaube, dass die Menschen, insbesondere Laien, dieses Wissen begehren. Meine guten Freunde, die mich darum baten, dieses Buch zu verfassen, scheinen mir hier nur das Bedürfnis von immer mehr Menschen zu repräsentieren.

Bei der Erstellung dieses Buches von den natürlichen Dingen, stütze ich mich unter anderem auf das lateinische Werk von Thomas von Cantimpré, "Liber de natura rerum", welches ich ins Deutsche übertrage. Hierbei greife ich auf meine hervorragende Lateinkenntnis zurück. "Liber de natura rerum" ist unter anderem beeinflusst von Aristoteles, Plinius und Solinus und erscheint mir als Quelle überaus geeignet.

Weitere nützliche Quellen, die ich für die Erstellung des Buches von den natürlichen Dingen heranziehe, werde ich hier im Folgenden aufführen.

- "Speculum naturale" von Vincenz von Beauvais

- "Etymologien" des Isidor von Sevilla

- "Naturwissenschaft" von Aristoteles

- "Naturalis historia" des Römers Plinius

- die Bibel

- verschiedene Schriften der Kirchenväter Augustinus und Ambrosius von Mailand (besonders "De civitate Dei"

- und Werke der Medizin, geschrieben von arabischen Gelehrten wie Avicenna und Rasis.

Allerdings sehe ich in einigen meiner Quellen auch Dinge, die mir nicht schlüssig, ja sogar falsch erscheinen und dies werde ich, mit Angabe meiner Gründe dafür, ebenfalls zum Ausdruck bringen und gegebenenfalls die korrekte Erklärung niederschreiben. Denn halte es für überaus sinnvoll und wichtig, das vorhandene Wissen zu reflektieren, kritisch zu betrachten und es unter den Gesichtspunkten der Logik zu beurteilen.

0 notes

Text

When to Use “Said”

There’s a myth that you should never use the verb say in your dialogue. Certainly, there are more exciting, muscular verbs out there, but too often writers resort to a thesaurus when a simple said would be more effective.

Compare the following:

“Are you sure this is where you saw it?” wondered Shazad.

“Yes, I told you. It’ll pass by any minute, trust me,” replied Mae.

“It’s not that I don’t believe you. It’s just that this branch has been poking me in the butt for like twenty minutes now,” complained Shazad.

“Wait! I hear something!” observed Mae.

“Are you sure this is where you saw it?” said Shazad.

“Yes, I told you. It’ll pass by any minute, trust me,” said Mae.

“It’s not that I don’t believe you. It’s just that this branch has been poking me in the butt for like twenty minutes now,” said Shazad.

“Wait! I hear something!” said Mae.

While neither example is ideal, the speech tags in the second example are less distracting than those in the first. Said has a way of fading into the background, while verbs like replied and observed can sound odd or stilted. You want your reader’s attention to move smoothly through the scene, not get snagged on awkward or unnecessary word choices.

Of course, that doesn’t mean you should always and only use said. Other verbs can be more effective when they tell us something important about the dialogue.

“Are you sure this is where you saw it?” whispered Shazad.

“Wait! I hear something!” hissed Mae.

Here both speech tags expand on the dialogue by telling us how it was spoken. And both are in keeping with the scene, not shoehorned in just to provide word variety.

Of course, you could always dispense with speech tags altogether.

“Are you sure this is where you saw it?”

“Yes, I told you. It’ll pass by any minute, trust me.”

“It’s not that I don’t believe you. It’s just that this branch has been poking me in the butt for like twenty minutes now.”

“Wait! I hear something!”

This can work well where you want a quick pace. But unless you’ve already introduced the characters, the reader won’t be able to picture them. And if you add a third speaker, things get really confusing.

“Is that it?”

“Shh!”

“Oh my God, you were right! It’s really real!”

“Excuse me. Do you mind giving me a little privacy?”

“Oh, uh, sorry.”

“Yeah, sorry, dude.”

You can still let your readers know who’s speaking without using speech tags. The characters’ actions, appearing on the same lines as their dialogue, cue readers as to who’s saying what. (For more on this, see Dialogue and Paragraph Breaks.)

Shazad leaned forward. “Is that it?”

“Shh!” Mae poked his shoulder warningly.

His jaw dropped. “Oh my God, you were right! It’s really real!”

The sasquatch glared at them through the tree branches. “Excuse me. Do you mind giving me a little privacy?”

Shazad cleared his throat. “Oh, uh, sorry.”

Mae winced. “Yeah, sorry, dude.”

This method keeps some of the punchiness of the dialogue-only approach while giving the reader more information. The scene is a lot more vivid when we know how the characters are moving and reacting in between speaking.

Of course, any sentence structure repeated too often will bore your reader, so you want to use some or all of these methods in combination. Remember, too, that you can put speech tags or actions in the middle of dialogue to switch things up.

“Are you sure this is where you saw it?” whispered Shazad.

“Yes, I told you,” said Mae. “It’ll pass by any minute, trust me.”

“It’s not that I don’t believe you.” He shifted awkwardly. “It’s just that this branch has been poking me in the butt for like twenty minutes now.”

Mae froze. “Wait! I hear something!”

“Is that it?”

“Shh!” she hissed.

His jaw dropped. “Oh my God, you were right! It’s really real!”

The sasquatch glared at them through the tree branches. “Excuse me,” she rumbled. “Do you mind giving me a little privacy?”

“Oh, uh, sorry,” said Shazad.

Mae winced. “Yeah, sorry, dude.”

What we can learn from the “never use said” myth is that no writing rule should be applied universally. A screwdriver may be an invaluable tool, but you wouldn’t use it to hang a picture. Writing tips are tools, and choosing the right one for each job is what the craft of writing is all about. Next time you’re enjoying a good book, notice how the author has put together their dialogue. I’m guessing somewhere in there they probably used said.

Images: 1. Cefusa, a legendary beast which leaves human footprints, Thomas of Cantimpré, Liber de natura rerum, France ca. 1290, from @discardingimages. 2. Apocalypse beast, France 1220-1270, from @discardingimages. 3. Sasquatch and her son by Sarah Goodreau, from @sarahgoodreau.

You can support this blog by becoming a patron. Those who pledge $5 or more a month get access to special bonus posts. Next month’s bonus post will be on faze vs. phase.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey tumblr we need to have a talk about something I noticed.

Specifically going by tags attached to images I’ve blogged or reblogged, there seems to be a misconception that marginalia means “any quirky medieval art”.

It’s not.

Marginalia is anything in the margins of a text.

The ones that will get posted on tumblr will more often than not be quirky drawings, but they also include notes, annotations, scribbles, and whatever else. The quirky drawings just happen to get a lot of press on here because, well. They’re quirky drawings.

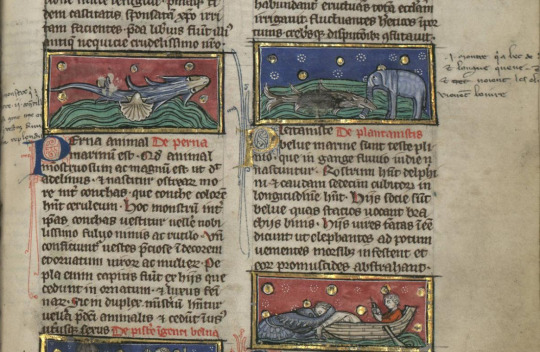

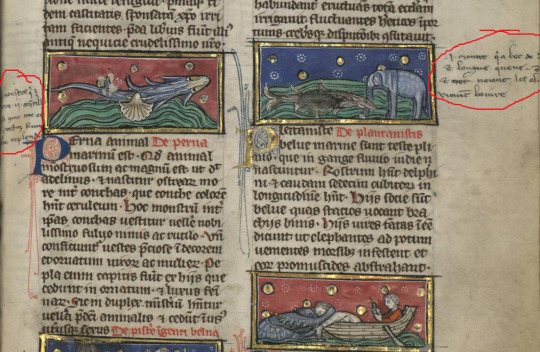

For instance, see this image here of a platanista (river dolphin) chomping down on an elephant’s trunk?

This is not marginalia! This is a full-fledged illustration. It’s within the text (Liber natura rerum, Thomas de Cantimpré, Librairie de Valenciennes Ms 0320). It illustrates the entry on Platanista.

This is what it looks like in context.

But you know what are marginalia? Let me circle them for convenience.

Know the difference. It won’t save your life but it will make you more popular at a medievalist conference.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

a "tygrides" looking at itself in the mirror

in a copy of thomas of cantimpré's "liber de natura rerum", bavaria, c. 1424

source: Vatican, Bibl. Apostolica Vaticana, Pal. lat. 1066, fol. 75v

#15th century#bestiary#thomas of cantimpré#liber de natura rerum#tygrides#tygridis#mirrors#medieval art

233 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Circhos #Cricos #Crichos Albertus Magnus takes up Thomas’ account, but drops the confusing details of the feet. The Ortus Sanitatis, on the other hand, creates some additional features out of whole cloth. The circhos or crichos has the head of a man and the body of a sea-dog (i.e. a dogfish or shark); it is healthy in good weather, but weakens and turns ill in bad weather. Olaus Magnus borrows the circhos of the Ortus Sanitatis to populate his Scandinavian sea. The physical description of a human-headed fish is wisely redacted. Whether it was meant to represent an actual Scandinavian animal, or is merely plagiarism, remains unclear. It is Olaus Magnus’ account that is best known today. Concept drift in modern retellings have led to fabrications such as a limping gait that forces the circhos to move only in fine weather and cling to rocks during storms, and even a “humanoid” appearance. References Aristotle, Cresswell, R. trans. (1862) Aristotle’s History of Animals. Henry G. Bohn, London. Barber, R. and Riches, A. (1971) A Dictionary of Fabulous Beasts. The Boydell Press, Ipswich. de Cantimpré, T. (1280) Liber de natura rerum. Bibliothèque municipale de Valenciennes. Cuba, J. (1539) Le iardin de santé. Philippe le Noir, Paris. Gauvin, B.; Jacquemard, C.; and Lucas-Avenel, M. (2013) L’auctoritas de Thomas de Cantimpré en matière ichtyologique (Vincent de Beauvais, Albert le Grand, l’Hortus sanitatis). Kentron, 29, pp. 69-108. Magnus, A. (1920) De Animalibus Libri XXVI. Aschendorffschen Verlagbuchhandlung, Münster. Magnus, O. (1555) Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus. Giovanni M. Viotto, Rome. Magnus, O. (1561) Histoire des pays septentrionaus. Christophle Plantin, Antwerp. Magnus, O. (1658) A compendious history of the Goths, Swedes, and Vandals, and other Northern nations. J. Streater, London. Rose, C. (2000) Giants, Monsters, and Dragons. W. W. Norton and Co., New York. Unknown. (1538) Ortus Sanitatis. Joannes de Cereto de Tridino. https://www.instagram.com/p/B0_j5eDnnxaioYyodMo8E2c8ve1xHB7Iejg9F00/?igshid=52rsrrg8rgho

0 notes

Text

This scorpion and a few others I'm going to queue up were sent to me by @joeyportfolioey, who says:

Since you've shown one manuscript of Jacob van Maerlant's Der Natueren Bloeme, I've been looking into other versions of that text. For context, the book is a Dutch adaptation of Thomas de Cantimpré's De Natura Rerum for a courtly audience (i.e. less theology and more falconry).

The textual description is as follows:

"Scorpio, that's a serpent (so says Solinus, who knows it well) that has a very sweet face, and it has a knotted tail which is very bent/sharp* in the back, and which is envenomed at all times."

*manuscripts differ here.

The oldest surviving manuscript is Lippische Landesbibliothek, Mscr 70, f. 102v, bottom right.

So let's do a quick comparison to the text.

Serpent: This critter clearly has legs. However, I have to concede that "serpent" was a pretty flexible term at the time, so that's not immediately disqualifying. (You'll sometimes see dragons described as "serpents", but that doesn't actually mean they're snakes.) I don't know how this works in medieval Dutch, but benefit of the doubt.

Sweet Face: I see where the artist is trying to go here. It says the scorpion has a sweet face, and what face is sweeter than a dog's? Naturally it makes sense to give it a canine head. The fact that the facial expression looks so distressed is probably down to artist skill, not intention. (Actually while "dog" is the first thing that came to mind, the longer I look at it, the more I think "squirrel", and I have no explanation for why the artist would have made that call.)

Knotted Tail: Well, okay, it's more of a helix than a knot, but you know, it gets the point across. I am also willing to believe that tail is sharp and/or bent.

I think that says what we need to say, so onward to points:

Small Scuttling Beaſtie? ½, not enough legs

Pincers? ✘

Exoskeleton or Shell? ✘

Visible Stinger? ✘

Limbs? 2

Vibes. Hm. I mean, I like it, but it just doesn't look happy to be here, which is worrying. I think this is definitely in the "it's a fine animal, but one that I kind of want to keep my distance from" category, which means a 4/5.

Total score:

4.7 / 10

Passable showing from the Dutch so far, but let's see how the other ones @joeyportfolioey sent me stack up before we make any judgments.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

LJS 23 is a late 13th c. copy of Thomas de Cantimpré's De natura rerum, a general introduction to science, including parts of his sections on fish, insects and invertebrates, trees, cosmology and astronomy, herbs, springs, gems, wind and clouds, the four elements, stars, and eclipses. One of the earliest known copies of this text. Notes in a modern German hand on front flyleaves and occasionally in margins.

Online: bit.ly/3om1XII

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

ethiopian monkey nursing its babies

in a copy of thomas of cantimpré's "liber de natura rerum", bavaria, c. 1424

source: Vatican, Bibl. Apostolica Vaticana, Pal. lat. 1066, fol. 62v

194 notes

·

View notes