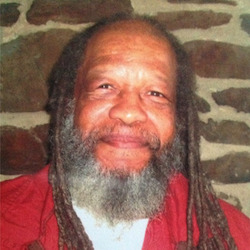

#vincent leaphart

Text

MOVE

What was this organization’s primary belief?

MOVE members shared the belief that “the world as we experience it is not as God intended. It is being held captive by an evil force called the System.” Co-founders John Africa and Donald Glassey authored the Guidelines, which provided members with ways to escape the System’s hold on society. Though MOVE began as a non-violent movement dedicated to living a more natural lifestyle, when they began to face aggression from the police force, MOVE felt they had no choice but to arm themselves.

What is this organization best known for?

MOVE is best known for its tensions with the Philadelphia police department, culminating in the 1985 bombing by Philadelphia police on their home. The 1985 bombing resulted in the deaths of eleven MOVE members, including five children and founder John Africa.

What are the major misconceptions about this organization?

One of the largest misconceptions perpetuated by the media of the time was that MOVE was a reactionary group rather than a religious community of like-minded revolutionaries.

When police blockaded their home in 1978 due to reports of MOVE assembling an “arsenal,” MOVE reacted in self-defense after nearly ten months of police intercepting their food and water supply. This resulted in the death of James Ramp, a veteran police officer. In retaliation, police excessively bludgeoned MOVE member Delbert Africa, an event captured in film by the Philadelphia Inquirer. Delbert Africa and eight other MOVE members were charged with murder for Ramp’s death. After 1978, MOVE’s protests shifted to focus on what they viewed as the unfair imprisonment of their family members. These non-violent protests eventually led to the 1985 bombing, when Philadelphia police once again raided the MOVE headquarters.

Who were the leaders of this organization?

Founded by John Africa, formerly known as Vincent Leaphart, and Donald Glassey, who was responsible for writing the MOVE bible, also known as the Guidelines.

What should we know about MOVE?

Due to Africa only having a third-grade education, he viewed learning to read and write as “synthetic education.” As a result, the children in MOVE were homeschooled to ensure they did not learn to read and write. Additionally, all MOVE members changed their last name to “Africa” to cement their place in the MOVE family. MOVE members viewed the organization as a family of people who had faced hardships at the hands of the System. MOVE allowed its members to unite and create the world God intended for them.

When discussing why MOVE is often framed as a cult, the fact that most members were African American cannot be overlooked. Even at the time, citizens of Philadelphia assumed that the police action against MOVE was due to racism. Though often compared to the Waco massacre, the MOVE bombing is lesser-known, and very little recorded information exists about the MOVE bombing, let alone MOVE as a religious organization.

0 notes

Photo

#Repost @x_theartist ・・・ “THE MOVE 9” - MAY 13th the day this same Government bombed on their own land. - ART BY @x_theartist - - - - - - - - - - MOVE is a black liberation group founded in 1972 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania by John Africa (born Vincent Leaphart) and Donald Glassey, a social worker from the University of Pennsylvania. The name is not an acronym. The group lived in a communal setting in West Philadelphia, abiding by philosophies of anarcho-primitivism.[1] The group combined revolutionary ideology, similar to that of the Black Panthers, with work for animal rights. The group is particularly known for two major conflicts with the Philadelphia Police Department. In 1978, a standoff resulted in the death of one police officer, injuries to several other people, and life sentences for nine members who were convicted of killing the officer. In 1985, another confrontation ended when a police helicopter dropped a bomb on the MOVE compound, a row house in the middle of the 6200 block of Osage Avenue.[2] The resulting fire killed eleven MOVE members, including five children, and destroyed 65 houses in the neighborhood.[3]The survivors later filed a civil suit against the city and the police department, and were awarded $1.5 million in a 1996 settlement.[4] - #XTHEARTIST#artwork#art#artist#arts#themove#move9#move#philly#Philadelphia#pa#police#BMABIAD (at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) https://www.instagram.com/p/CAJlbjXpk8I/?igshid=eavsui7x0qc2

1 note

·

View note

Text

The next to last MOVE

[The release of Delbert Africa after 42 years in prison has lit me up like fireworks. Most of what's below was written several years ago, so this is a minor update. But goddamn am I glad he's out. It doesn't put the end to anything – one other MOVE member is still languishing – but it lends the closing bracket on a time and place that's long, long been central to my life. I never talked to Delbert, but I was never less than monumentally impressed by him, even though I thought MOVE was basically off its nut. See what you think.]

In the summer of 1978, my wife Linda and I had fun towing her little red wagon full of rocks through the police line during the first confrontation between the city of Philadelphia and MOVE.

Never heard of MOVE, or only recently with an odd revival of interest? I'm not surprised. Only in Philadelphia could the record of summer-long martial law effectively... vanish for decades.

Back then, MOVE was often called a "back to nature" and/or "anti-technology" outfit: A back-to-nature-anti-technology outfit that used bullhorns, lived in the middle of a city of 1.5 million inhabitants and organized protests of Jane Fonda and Buckminster Fuller. Demonstrating against the then-82-year-old champion of the geodesic dome – who would do such a thing, why?

Only MOVE, only in our itty-bitty liberal enclave of Powelton Village, and I think no one will ever know exactly why. They followed the teachings of Vincent Leaphart, whose rambling treatise made little sense to anyone beyond his small band of raucous believers. "MOVE" wasn't an acronym, just a word, but always capitalized. Leaphart changed his name to John Africa and insisted his followers all take the last name of Africa.

Powelton, a ten-square-block Victorian snippet of West Philadelphia north of Drexel University and the University of Pennsylvania, began as the city nabobs' summer-retreat in the late 19th century, just across the Schuylkill River from Center City. By the late 1960s it had attracted a loose rattle of quiet leftists and inoffensive layabouts who were tolerant of most anybody but Drexel, which was determined to devour as much of the community as it could ladle down (and has now debased the area with overpriced apartments for its students.)

During the late '70s, Powelton's squishy acceptance allowed MOVE to occupy a pair of brick twins at 33rd and Pearl Sts., no more than a block from our commune, where they nailed together huge, ramshackle ramparts, kept a pack of half-feral dogs, ate raw meat and tossed their garbage in the yard. An all-black group (except for one scrawny white woman), they were dreadlocked and more physically fit than any health poster.

For income, they washed cars on 33rd St. (and did a damned fine job of it). On no particular provocation, they would mount the ramparts, pick up a bullhorn and harangue the world. It made a hell of a racket. They could also explode into sudden violence, especially against the police, though I regularly walked past their house and was never harassed.

The city, citing housing and sanitation regulations, declared them pests and obtained a court order telling them they had to go. The order set off one of the strangest confrontations in modern American history.

On a quiet summer evening, the MOVErs mounted the ramparts carrying rifles and dressed in camo fatigues. You'd think the police would act. Well, they did: They blocked traffic on 33rd St. That was it. They never approached the MOVE house. During the protest, Delbert Africa, their chief spokesman (one of the most beautiful human beings who ever existed) issued this statement, part haiku, part tautology, that has always defined MOVE for me:

"Any motherfucker

tries to take away my motherfuckin' rights,

that man is a motherfucker."

I doubt their guns were loaded (they have since claimed they were not). For one thing, they were pointed straight up, for show. For another, the fatigues still had folds in them – the protestors had bought them that afternoon, probably at I. Goldberg's, a decades-old army-navy surplus store.

The city's mayor was Frank Rizzo, former police commissioner from South Philly, idolized by the Italian community, hated by the gays and blacks he had hounded throughout a career of sneering, swaggering machismo (my favorite quote: "I'll make Attila the Hun look like a faggot").

Rizzo's response to MOVE was incomprehensible and ultimately ruinous for the city. Rather than clear the house of this rabble on outstanding charges of health and safety violations, he directed the police department to place a cordon around our neighborhood and wait for MOVE to capitulate. (If China had suggested starving out a bunch of dissidents, the U.S. would have been mightily upset.) Worse, he announced his plans a couple weeks in advance, giving MOVE's supporters ample time to haul in truckloads of supplies, including a skid of dog food.

For the next roughly six weeks, Powelton was occupied by up to 2,000 police and support personnel. I still find it hard to grasp that a judge blithely approved a state of martial law to enforce health regulations. And that his ruling was never seriously challenged or overturned.

To those familiar with MOVE, the result was foreordained—they simply hunkered down and refused to... move. Us Poweltonians, meanwhile, had to show identification to enter our own streets. The local activists, in their vocal but placid way, formed so many committees to discuss the situation – roughly equal pro- and anti-MOVE – that a higher committee coalesced to coordinate them all.

About then, Linda was moving back to the commune where I'd met her and where I still lived. We had no "transportation" beyond a battered wire shopping cart and her little red wagon. Back and forth we clumped from her apartment, the wagon loaded with books, kitchen equipment and the big garden rocks she'd brought from her home in Kansas. After awhile, even the cops found it ridiculous to keep asking for our IDs. They'd grin lightly, look bemused, then stand aside.

The immense police presence was absurdly ineffective. They exempted the street behind us from the cordon, and since our block had no internal fences, I would walk Pearl, our exuberant St. Bernard, down our front steps and half way around the block, then in the back way, without a single police challenge. The neighborhood also experienced a marked increase in breaking and entering – I guess it heightened the crooks' street cred to thumb their noses at the Man.

Across the city, the police force was in a shambles from diverting 20% of its resources to a pointless, static operation. (Once the blockade was lifted, they found that MOVE had moled a tunnel through to Powelton Ave., sneaking in supplies during the entire occupation.)

As I hazily recall it, the city and MOVE reached an agreement that if the police lifted their blockade, MOVE would hand over their guns. The police lifted the blockade, and –surprise! – MOVE handed them a bellylaugh.

Then one morning Linda and I were awakened by a short, intense rattle of gunfire. It hit like a mallet: "My god, they're killing them all." As it turned out, one police officer, James Ramp, was killed but no MOVE members. Despite conflicting forensic evidence on where the shot had come from, nine MOVErs were convicted of third-degree murder and for decades were regularly denied parole.

When I returned from work that afternoon, the street in front of our house was scored with caterpillar treads. I followed them around the corner to 33rd St. The MOVE houses were gone – three-story brick Victorian twins evaporated, the ground a smooth expanse of Philadelphia's yellow-brown clay. As Linda's young son Ben said, "At least they didn't salt the earth."

The occupation and confrontation were big news in city media back then, but they never caught national attention. Why? Can you name another example of weeks-long, uncontested martial law in a major American city?

That wrapped up MOVE for Powelton, but not for the city. Seven years later, on May 12-13, 1985, under Mayor W. Wilson Goode, the local government again lost its ability to think like adults in response to MOVE. The remaining group had moved to Osage Ave. on the city's western edge and again erected ramparts, but the local population was less willing than the loosey-goosey Poweltonians to accept such disruption.

This time, the city cut corners and turned to direct confrontation. The result was an armed standoff that ended when a collective of official imbeciles OKd dropping a parcel of C4 explosive onto MOVE's roof bunker. As the resulting fire spread, rather than endanger the firemen standing ready (or so read the official rationale), it was left to go its merry way.

The entire square block of over 60 rowhouses burned flat. When the smoke had cleared and the flames died out, 11 members of MOVE were found incinerated, including John Africa and five children. There were only two known survivors, Ramona Africa and nine-year-old Birdie Africa, who was permanently disfigured.

A footnote: Ramona, along with Birdie's relatives, were paid millions in damages. Ramona bought a house in the city's Kingsessing neighborhood, where she and MOVE remnants live a relatively quiet life. After hemming and hawing, the city agreed to rebuild the houses destroyed through its asinine incompetence. As a monument to shoddy, graft-infested contracting, the replacement homes proved uninhabitable, the contractors faced criminal charges, and the bedraggled homeowners were once again evicted while their "new" homes were razed and replaced.

by Derek Davis

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The photograph is one of the standout images of the 1970s black liberation struggle. An African American man, his hair in dreadlocks, chest bare, stands with arms outstretched as though emulating Jesus on the cross. A white police officer is jabbing a shotgun at him with the muzzle inches from his throat. Another officer clasps a police helmet in his right hand as if preparing to whack him over the head with it.

Forty years almost to the day after that photo was taken, the same black man described how he came to be standing there on a sidewalk, half-naked and surrounded by angry police. His account was almost too graphic to grasp, sounding more like something out of a movie than the recollection of what really happened in the heart of one of America’s major cities.

It was 8 August 1978 and he had just emerged from the basement of the house in Philadelphia that his black revolutionary group, Move, used as a communal home. In an attempt to evict them from the property, hundreds of officers had just stormed the building, pummeling it with water cannons and gunfire, and in the maelstrom a police officer had been killed and several other first responders injured.

“As I emerged from the basement I had the presence of mind to let them see I was unarmed, so I took my shirt off,” the black man said. “That’s when I put my arms out wide.”

The black man is Delbert Orr Africa, Del for short. When I went to meet him he was wearing a burgundy one-piece with a white T-shirt and blue shoes. Everyone else around him was wearing the same uniform of Dallas maximum-security prison in Pennsylvania that he has worn every day since appearing in that photograph 40 years ago.

I had come to interview him as part of a two-year project in which I made contact with eight black liberationists who have all experienced long prison sentences. They each agreed to embark on an ongoing conversation with me about their political beliefs today and their battle to secure their own freedom.

Del Africa, 72, and I talked for three hours in the prison visitors’ room. He spoke rapidly and intensely, as though he needed to get it all out, relating how he had joined the Black Panther party in Chicago and then switched to the Move organisation after relocating to Philadelphia.

He also told me what happened the second after that photo was taken, as though he were narrating the next few frames of a news reel. As it turns out, that police officer really had been about to whack him.

“A cop hit me with his helmet,” he said. “Smashed my eye. Another cop swung his shotgun and broke my jaw. I went down, and after that I don’t remember anything ’til I came to and a dude was dragging me by my hair and cops started kicking me in the head.”

Del Africa is one of the Move 9, the group of five men and four women, all African American, who were arrested 40 years ago this August during the 1978 police siege of their headquarters in Powelton Village, Philadelphia. They were charged as a nine-person unit with the murder of the police officer who died in the melee, James Ramp. Each was sentenced to 30 years to life, though to this day they protest their innocence.

The ranks of the Move 9 have slowly been depleted over the years. Two have died in prison. In June, the first of the nine to win parole, Debbie Africa, was released from a Pennsylvania women’s prison.

As the 40th anniversary approaches, six of the Move 9 are still behind bars, Del Africa included. They are among a total of 19 black radicals who remain locked up in penitentiaries across America having been convicted of violent acts committed in the name of black power between the late 1960s and early 1980s.

Along with former Black Panthers and Black Liberation Army members, they amount to the unfinished business of the black liberation struggle. Many of them remain strikingly passionate about the cause, even as they strive for release in some cases half a century into their sentences.

In the case of Move members, their politics are a strange fusion of black power and flower power. The group that formed in the early 1970s melded the revolutionary ideology of the Black Panthers with the nature- and animal-loving communalism of 1960s hippies. You might characterise them as black liberationists-cum-eco warriors.

That sense of passion for the cause leaps out from the first email that Del Africa sent to me from Dallas in September 2016, after I’d contacted him asking to talk.

“ON THE MOVE! LONG LIVE FREEDOM’S STRUGGLE!” he proclaimed in capital letters at the top of the message. “Warm Revolutionary greetings, Ed!”

He then launched into a long deliberation about the “plight of political prisoners here in ameriKKKa!”. Move members are still imprisoned, he wrote, “just because we steadfastly refused to abandon our Belief in the Revolutionary Teachings of Move’s Founder” and because of “our refusal to bow down to this murderous, racist, sexist rotten-ass system”. He ended with the quip: “But, hey, I don’t wanna burn you out the first time I reply to your email.”

There was a similar robustness to the first response I received in December 2016 after reaching out to Janine Phillips Africa, one of the four women among the Move 9. Unlike Del Africa’s email, she wrote to me by hand, sending the letter by mail as she has continued to do over the ensuing 18 months.

“Me and my sisters are doing good, staying strong,” was the first sentence she wrote to me. That was remarkable in itself coming from a woman who is not only approaching the 40th anniversary of her incarceration but has had two of her children killed in confrontations with police.

“Everybody knows how strong Move men are. We’re showing the world how strong Move women are. That’s how it’s been since our arrest in 1978,” she said.

In the course of that first letter, Janine Africa, who was 22 when she was arrested and is now 62, took me deep into the “torture chamber”, the cruel solitary confinement wing where she spent the first three years of her sentence.

“There were no windows, just a section of the wall with frosted panes. You couldn’t tell when it was night or day, they kept the lights on 24/7. They were ordered to break us but it didn’t work – no matter what they did, they were not going to break us.”

Over the months, I came to learn about the double tragedy in Janine Africa’s life. In 1976, Philadelphia police officers turned up at the Move house in Powelton Village having been called out to a disturbance. Scuffling ensued between some Move residents and police. Janine was shoved and her baby, whom she had named Life, was knocked out of her arms to the ground. His skull appears to have been crushed, and he died later that day in her arms. He was three weeks old.

Then on 13 May 1985, seven years after Janine Africa was imprisoned, she received further terrible news. Philadelphia police had dropped a bomb from a helicopter onto a Move house on Osage Avenue in the west of Philadelphia in an attempt to force the black radicals to evacuate the premises after long-running battles with the authorities. The bomb ignited a fire in the Move house that turned into an inferno.

Janine’s 12-year-old son, Little Phil, was being cared for in that house by other Move adults while she was in custody. The then mayor of Philadelphia, Wilson Goode, notoriously gave the go-ahead for the bombing, and the fire that ensued was allowed to rage, the blaze spreading across the black neighborhood and razing 61 homes to the ground.

Little Phil and four other children burned to death. So too did six adults including Move’s founder, John Africa, AKA Vincent Leaphart.

I asked Janine Africa how she coped with losing two young sons during clashes with law enforcement. She was reticent. “I don’t like talking about the night Life was killed,” she wrote in April. “There are times when I think about Life and my son Phil, but I don’t keep those thoughts in my mind long because they hurt.”

In that same letter she said she had turned grief into what she contests is a force for good: deeper commitment to the struggle. “The murder of my children, my family, will always affect me, but not in a bad way. When I think about what this system has done to me and my family, it makes me even more committed to my belief,” she said.

Del Africa also heard bad news on 13 May 1985. His 13-year-old daughter Delisha was also living in the Move house. She too died in the fire. When I asked him how he dealt with being told his daughter had been killed in an inferno that had been ignited by the actions of the city authorities, he wasn’t as sanguine as Janine.

“I just cried,” he said during my prison visit. “I wanted to strike out. I wanted to wreak as much havoc as I could until they put me down. That anger, it brought such a feeling of helplessness. Like, dang! What to do now? Dark times …”

Mayor Goode made a formal apology for the disaster the following year. But a grand jury cleared all officials of criminal liability for the 1985 bombing that killed 11 people, including five children.

The only adult Move member to escape the inferno alive, Ramona Africa, was imprisoned for seven years.

All Move members take the last name “Africa” to denote their commitment to race equality and their strong bond to what they regard as their Move “family”. “A family of revolutionaries” is how Del Africa once described it to me. Unlike the Black Panther party which formally dissolved in 1982, Move is still a living entity.

“We exposed the crimes of government officials on every level,” Janine Africa wrote to me. “We demonstrated against puppy mills, zoos, circuses, any form of enslavement of animals. We demonstrated against Three Mile Island [nuclear power plant] and industrial pollution. We demonstrated against police brutality. And we did so uncompromisingly. Slavery never ended, it was just disguised.”

Deeply committed as they were to each other, the Move “family” undoubtedly had the ability to incense those around them. They liked to project their revolutionary message at high volume from a bullhorn at all hours of night and day. Passersby were accosted with a torrent of expletives.

Then there were the dogs. When the 1978 siege happened, there were 12 adults and 11 children in the Move house in Powelton Village – and 48 dogs. Most of the animals were strays taken in by the group as part of its philosophy of caring for the vulnerable. Black liberation, animal liberation – the two are as one with Move. John Africa was known as the “dog man”, as he was rarely seen without one.

The unconventional nature of the Move community which drove some neighbors to despair in turn led to demands for their eviction, and ultimately to the fatal siege. Over time relations grew more belligerent. Months before the siege Move members made visible their threat to resist attempts to remove them from the neighborhood – they stood on a platform they had built at the front of the house dressed in fatigues and brandishing rifles.

On its side, the city was led at that time by the Frank Rizzo, Goode’s predecessor as Philadelphia mayor, a former police commissioner who liked to talk tough and was fond of dog-whistle politics. He once said of the Move radicals: “You are dealing with criminals, barbarians, you are safer in the jungle!” Another Rizzo classic was: “Break their heads is right. They try to break yours, you break theirs first.”

When Move refused to vacate the premises having been issued with an eviction order, Rizzo said he would impose a blockade on the house so tight “even a fly wouldn’t get in”. He was not kidding. For 56 days before the siege, a ring of steel was erected around the house, no food was permitted into the compound and the water supply was cut off. Rizzo bragged he would “show them more firepower than they’ve ever seen”.

At about 6am on 8 August 1978 the action started. Move members were battered by water cannon as they took refuge in the basement of the building. Tear gas was propelled into the house. At 8.15am shots rang out and a thunderstorm of gunfire erupted that is captured on police footage of the incident. Police and fire officers are seen scattering in all directions as bullets whistle overhead seemingly in all directions. It looked like a war zone.

Soon after Move adults and naked children began emerging from the smoke-ridden basement. Janine Africa can be heard in the police footage screaming. Next, Del Africa appears, his hands outstretched in that Jesus pose. The camera pans in on him as he lies on the street after he was hit with the police helmet. Two police officers begin kicking him on his head which bounces between them like a ball. Three officers later faced disciplinary measures but a judge dismissed the charges.

Prosecutors accused the Move 9 of collaboratively killing Ramp, even though he died from one bullet. They said the shooting had been started when gunfire erupted from the basement where the Move members were gathered, a theory supported by some eyewitnesses.

Move’s attorney gathered other witness evidence suggesting the fatal shot had come from the opposite direction – in other words, it was accidental “friendly fire”. At trial no forensic evidence was presented that connected the Move 9 to the weapon that caused the fatality. For the women in particular the prosecution did not even argue the four had handled firearms or had been involved in the actual shooting of Ramp.

Del Africa insisted when I interviewed him that though Move had guns in the house, none of them were operative. “There was no shooting from our side,” he told me. “No one in the house had any gunshot residue, none of us had fingerprints on any of the weapons they claim came out of the house.”

The Philadelphia Fraternal Order of Police has a plaque for Ramp on its memorial site. I reached out to the order many times in the course of a month to hear their reflection on his death and Move’s role in it, but they did not respond.

You can get a sense of the depth of feeling by reading the comments under Ramp’s page on the Philadelphia Officer Down Memorial website. Several commentators, some of whom vividly recalled the 1978 siege, sent blessings to the deceased police officer and his family.

Others expressed anger at the lack of justice for Ramp, though they didn’t specify what they meant. One woman, whose late husband was on duty at both the siege and the 1985 bombing, was more direct. She said of Ramp: “I was so sad to hear of your passing. I felt, and still do feel so badly for your family. Move were scum and cowards, hiding as they shot. You were SO brave. Never forgotten. RIP.”

As they approach the 40th anniversary of the siege and of their subsequent captivity, Del and Janine Africa described to me how they’ve coped for so long doing time for a crime they insist they did not commit. They each have their own survival methods.

Janine Africa told me she avoids thinking about time itself. Birthdays, holidays, the new year mean nothing to her. “The years are not my focus, I keep my mind on my health and the things I need to do day by day.”

Del Africa thinks of the eons behind bars not as “prison time” but as “revolutionary prison activity”. “I keep saying to myself: ‘I will not fall apart. I will not give in.’”

They’ve both experienced long stretches in solitary confinement, a brand of punishment that the UN has decried as a form of torture. In 1983, Del Africa was put into the “hole” – an isolation cell – because he refused to have his dreadlocks cut.

He stayed in the hole for six years. He relieved the stress and boredom by organizing black history quizzes for other inmates held in the isolation wing. Russell Shoaltz, a former Black Panther, helped him devise the questions, and shout them out down the line of solitary cells. Questions such as: when was the Brown v Board of Education ruling in the US supreme court? What year was the Black Panther party founded? Who was Dred Scott? For what is John Brown remembered?

Eventually Del Africa won the right to keep his dreads. When I visited him in Dallas there they hung, salt-and-peppered now, proudly down to his hips.

Throughout, the Move prisoners have drawn strength from companionship with other members of the nine. Janine shared a cell with two other surviving Move women – Debbie Africa and Janet Holloway Africa – in Cambridge Springs women’s prison in Pennsylvania. They called each other “sisters” and did everything together. “We read, we play cards, we watch TV. We laugh a lot together, we’re sisters through and through,” she wrote in a letter in February.

There was one other member of their gang: fittingly given the history of the organization, a dog called Chevy. The prison authorities let them keep the dog kenneled in their cell as part of a program in which they train the animal for later use as a service dogs for disabled people.

Life went on like this for years, and had acquired its own normality, almost a certain tranquility. Until last month when Debbie Africa was granted parole and set free. Her departure came as a jolt.

“It’s strange not having Deb here,” Janine said. “I keep expecting her to walk in from work. They snuck her out at 5.[:]00 in the morning. We only got to hug her briefly and watch her leave. Chevy misses her, he keeps sniffing her bed.”

In June, Janine and Janet Africa also went before the same parole board as Debbie and made essentially the same case that they had earned their freedom. The board asked Janine whether she would be a risk to the public were she to be let out, and she referred them to her pristine prison record: the last time she had any disciplinary rap was 26 years ago. “The way I’m in here is the way I’ll be outside, there is no risk factor,” she told them.

While Debbie was set free, both Janine and Janet had their parole denied. The board said they showed “lack of remorse” for the death of Ramp in the 1978 siege.

Janine Africa wrote to me a few days after she learnt of the denial, speculating that games were being played with her mind. The contrast of Debbie’s release with her denial was “either to make us resent Deb or make me feel hopeless and break us down. Whatever their tactic, it isn’t working!”

Debbie’s release also made a profound impact on Del Africa. “I feel overjoyed that Debbie is out,” he wrote to me. “Her release is a breakthrough! I see it finally opening the door a crack.”

Del Africa also hasn’t had a misconduct report in prison for more than 20 years. Yet he too was turned down for parole last year and must wait another four years before his next chance to convince the parole board that he can safely be returned to society.

Like many of the 19 black liberationists still behind bars, Del Africa is caught in a trap attached to the crime for which he was convicted. He knows he will only be paroled if he expresses heartfelt remorse. But says he cannot do that.

“How can I have any remorse for something I never did?” he said. “I had nothing to do with killing a cop in 1978. Have they shown any remorse for what happened to my daughter in 1985?”

Would he show remorse to the parole board if he felt it would secure his release?

“No, never going to do that,” he said. “That would be akin to making them right. They are the ones who were wrong.” [x]

Photograph:

The arrest of Delbert Africa of Move on 8 August 1978

Debbie Africa was released in June after 40 years in prison

Members of Move gather in front of their house. They were arrested 40 years ago during a police siege.

Janine Africa preaching to the crowd in front of the barricaded Move house in the Powelton Village section of Philadelphia

Move members hold sawed-off shotguns and automatic weapons as they stand in front of their barricaded headquarters

Debbie Africa and her son, Mike Africa, whom she gave birth to in her prison cell a month into her incarceration. She was released last June.

#move#move 9#philly#philadelphia#amerikkka#police brutality#black power#delbert africa#del africa#delbert orr africa#debbie africa#powelton village#james ramp#black liberation#black panthers#black liberation army#janine phillips africa#janine africa#wilson goode#john africa#vincent leaphart#lil phil#ramona africa#frank rizzo#philadelphia fraternal order of police#racism#white supremacy

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On Aug. 8, 1978, MOVE member Delbert Africa climbed out of his basement and raised his arms to the sky in surrender. The image soon became one of the most iconic photographs in Philadelphia history, as seconds later, police officers were caught on film beating Africa with a helmet & rifle, then dragging him by his dreadlocks. The incident was part of the first armed battle between the Philadelphia Police Department & MOVE, a radical liberation group living at the time in a Powelton Village commune. On Saturday morning, Africa, 73, was captured outstretching his arms once again, this time as a symbol of freedom. He was paroled from prison after more than four decades of incarceration. Africa was one of nine MOVE members sent to prison on third-degree murder charges for the death of Philadelphia Police Officer James Ramp, shot during the 1978 standoff between MOVE and Mayor Frank Rizzo’s Police Department. The episode culminated a 15-month-long clash between city authorities and MOVE members, primarily involving health‐code & weapons violations. MOVE was created in 1972 by West Philadelphia native Vincent Lopez Leaphart, who later called himself “John Africa” and preached an ideology centered on black revolutionary ideas & back-to-nature philosophies. The dozens of members considered MOVE their religion, adopting antitechnology and antigovernment beliefs, while taking on issues ranging from police brutality to animal rights. Members would often stage protests and eventually began to use loudspeakers to broadcast tirades throughout their neighborhood. In 1977, a federal grand jury indicted 11 MOVE members on bomb-plot charges, after an arsenal of weapons, including 49 pipe bombs and parts, was seized from the group. A year later, the city created an eviction order that sent police to raid MOVE’s Powelton Village home. Firefighters flushed the house with fire hoses, and police violently removed people. In the end, one shot killed Ramp. Eighteen police officers and firefighters were hurt. MOVE has always claimed that the bullet that killed Ramp was accidentally fired by police. “I’m so happy to have my brother home," (SWIPE LEFT) https://www.instagram.com/p/B7gD-UhAvzQ/?igshid=1rtos9vj1f5gg

0 notes

Text

AMERIKA: 'May 13, 1985', The Day When Police Dropped a Bomb on a Quiet Philly Neighborhood - By Alex Q. Arbuckle (Flashback)

AMERIKA: ‘May 13, 1985’, The Day When Police Dropped a Bomb on a Quiet Philly Neighborhood – By Alex Q. Arbuckle (Flashback)

Source – mashable.com

–“…The black liberation group MOVE was founded in 1972 by John Africa (born Vincent Leaphart). Living communally in a house in West Philadelphia, members of MOVE all changed their surnames to Africa, shunned modern technology and materialism, and preached support of animal rights, revolution and a return to nature….”Drop a bomb on a residential area? I never in my life heard…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Blog #8 - MOVE

What is MOVE? According to Beverly C. Tomek: “MOVE, a controversial Philadelphia-based organization often associated with the Black Power movement, combined philosophies of black nationalism and anarcho-primitivism to advocate a return to a hunter-gatherer society and avoidance of modern medicine and technology. The group’s very loud and public quest for racial justice, as well as its strong views on animal rights, led to a number of confrontations between MOVE members and their West Philadelphia neighbors as well as with Philadelphia police. The most famous of these confrontations, in 1985, earned Philadelphia a reputation as “the city that bombed itself”.

MOVE was founded in the early 1970s by West Philadelphian Vincent Leaphart after he returned from service in the Korean War (West Philadelphia Collaborative History - WPCH). Leaphart, who would come to be know as John Africa, had no more than a third grade education, and so reached out to a University of Pennsylvania social worker named Donald Glassey to aid in drafting a MOVE foundational document (Tomek). “Initially known as The Book of Guidelines, The Book, or The Guidelines and eventually called The Teaching of John Africa. Since the founding of the group in 1972, MOVE members have lived communally primarily in West Philadelphia, with additional properties in Rochester, New York” (Tomek). Puckett and DeSilvis note: “The word itself was not an acronym—quite simply, MOVE was MOVE. The group identified as a religious and political organization. All MOVE members adopted the surname Africa, took on the age of 1 (to symbolize a rebirth), and wore their hair in dreadlocks.” On August 8th, 1978, Members of MOVE had the first major conflict with police in Powelton Village when they refused to vacate their initial compound; this left one police officer dead and nine members of MOVE with life sentences (Tomek).

After this, MOVE settled in a largely middle-class and African-American neighborhood and came into conflict with the neighbors concerning harassment and health risks as they used a bullhorn to broadcast messages day and night, turned their home into a fortress, and kept a staggering amount of animals including cats, dogs and rats (Tomek). “On May 13, 1985, after three years of nuisance complaints from MOVE’s Osage Avenue neighbors, a confrontation between MOVE and the Philadelphia Police ended in arguably the most traumatizing event in Philadelphia’s history” (Puckett). “MOVE styled itself as a “self-defense” organization even as it mounted an aggressive campaign on the 6200 block of Osage to demand the release of the incarcerated MOVE 9. The last straw for MOVE’s neighbors was the erection of a fortified “heavy timber” bunker on the roof of 6221 Osage, with “holes that were gun ports.” On April 30, 1985, the neighbors, at wit’s end, appealed to Governor Richard Thornburgh in a high-profile news conference” (Puckett). This resulted in arrest warrants being issued by Mayor Wilson Goode, to be executed on Monday, May 13th, 1985.

When MOVE members again showed resistance to police demands, The use of extreme measures, including military grade weapons, fire hoses, teargas, and eventually explosives ensued, culminating in a shootout. “After shooting thousands of rounds into the MOVE compound, police decided to use explosives to knock the bunker off the roof, using a Pennsylvania State Police helicopter to drop high-powered C4 explosives onto the house. The explosives caused a fire, accelerated by the presence of gasoline in the home” (Tomek). The fire spread through the neighborhood, destroying more than 60 homes. Upwards of 250 Philadelphians were left homeless. “Danger from crossfire also kept MOVE members pinned inside the home. Some eyewitness reports indicated that when MOVE members finally tried to exit the burning house, police fired on them, but controversy remained over this claim” (Tomek). Conflicting reports aside, five children and six adults were killed in the bombing, and the highly-televised to destruction Led to widespread criticism from across the country of the decision is made by officials and mayor involved in the incident.

Sources:

https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/move/

https://collaborativehistory.gse.upenn.edu/stories/move-powelton-village

https://collaborativehistory.gse.upenn.edu/stories/move-osage-avenue

0 notes

Photo

Readers see how bands of self-proclaimed “angles of death,” fueled by lust, power, and the thrill of death, committed acts of violence. This book by James J. Boyle introduces eleven different killer cults:

Chapter One: Summer of Love - Charles Manson

Chapter Two: Dad Knows Best - Jim Jones

Chapter Three: Gordon Kahl - Gordon Kahl

Chapter Four: Palace of Gold - Keith Ham (Kirtanananda Bhaktipada)

Chapter Five: Come and Get Us! - Vincent Leaphart (John Africa)

Chapter Six: Blood Atonement - Jeffrey Don Lundgren

Chapter Seven: El Padrino - Mark Kilroy

Chapter Eight: Yahweh - Hulon Mitchell, Jr. (Yahweh Ben Yahweh)

Chapter Nine: King of the Israelites - Roch Theriault

Chapter Ten: Ranch Apocalypse - Vernon Wayne Howell

Chapter Eleven: Circle of Fire - Luc Jouret

This book did not give much information about how these crimes were solved. This book lacks information on the crimes introduced!!!

0 notes