#delbert africa

Text

I found this on NewsBreak: Decades on, Delbert Africa’s surrender still provides powerful image of US racism and Black victimhood

I found this on NewsBreak: Decades on, Delbert Africa’s surrender still provides powerful image of US racism and Black victimhood

0 notes

Text

Geo-Cultural Groups

Europe:

-Caucasian: mountains

-Sarmatic Plains: Swamps, woodlands, plains, and small Vikings élite

-Balkanatolia: heartland of Hellenic civilization

-Italic: (North) City States & Germandom, (Mid) Papal states, (South) Byzantine and Norman Polities with Islamic influence

-Iberian:

-Nordic:

-Variscidia: Aside from the Papal states, Variscidia was the heartland of catholic powers during the early middle ages. It’s cultural background was a syncretism between Latin and Germanic traditions. Variscidia was the region of Europe that served as a bulwark against northern pagan Europeans, Eastern-Oriental Christendom, and Islamic expansion.

-British Isles:

-Visigrad: Transitionary phase into western Europe, Catholicism, Slavs and Steppe peoples (mongols, avars, gepids and magyars)

Asia:

East Asia:

-Tibetan Plateau:

- Northern River Basins:

-Southern River basin

- Goguryeo Mountain Enclosure:

-Mongolian Steppe

-East Asian Desert Complex

-Japanese Archipelago:

North Asia:

-Siberian Plateau (Eastern Mountain Complex, Central Mountain Complex)

-Siberian Plain

-Kolyma

-Yakutsk Basin

-Central Asian Desert Complex (West Asian Mountain Complex Included)

Southeast Asia:

-Indochinese Peninsula

-Malay Archipelago

Indosphere:

-Deccan Polities:

-Indo-Gangetic Polities:

Oceania:

-Polynesia

-Micronesia

-Melanesia

Middle East:

-Levant:

-Arabian Peninsula:

-Mesopotamia:

-Iranian Plateau:

Africa:

-Sahelian Kingdoms: Muslim & Sahelian, mounted warfare

-Guinean Kingdoms: Forested & Folk Religions

-Nile Kingdoms: Egypt, Nubia, axum

-Maghreb:

-Kongo Kingdoms:

-Lake Kingdoms:

-Kalahari Plateau:

-Swahili City States:

North America:

Appalachian Woodlands: Iroquoise & Algonquian, wooded, Haudenosaunee, long houses

Great Lakes:

Mississippian Ideological Interaction Sphere: Chimakuan, woodlands, mound builders, south east,

Great Plains:

Great Basin: aztec tanoan, "Desert Archaic" or more simply "The Desert Culture" refers to the culture of the Great Basin tribes. This culture is characterized by the need for mobility to take advantage of seasonally available food supplies. The use of pottery was rare due to its weight, but intricate baskets were woven for containing water, cooking food, winnowing grass seeds and storage—including the storage of pine nuts, a Paiute-Shoshone staple. Heavy items such as metates would be cached rather than carried from foraging area to foraging area. Agriculture was not practiced within the Great Basin itself, although it was practiced in adjacent areas (modern agriculture in the Great Basin requires either large mountain reservoirs or deep artesian wells). Likewise, the Great Basin tribes had no permanent settlements, although winter villages might be revisited winter after winter by the same group of families. In the summer, the largest group was usually the nuclear family due to the low density of food supplies.

Oasisamerica: Pueblo, cities, agrarian

Plateau:

Californian: The Pauma Complex is a prehistoric archaeological pattern among indigenous peoples of California, initially defined by Delbert L. True in northern San Diego County, California.The complex is dated generally to the middle Holocene period. This makes it locally the successor to the San Dieguito complex, predecessor to the late prehistoric San Luis Rey Complex, and contemporary with the La Jolla complex on the San Diego County coast.

Northwest Coast:

Arctic:

Subarctic:

Mesoamerica:

South America:

Andes:

Amazon:

Plains:

Australia:

Blaze

0 notes

0 notes

Video

DSC_9357 by Joe Piette

Via Flickr:

EMERGENCY PRESS CONFERENCE for DELBERT ORR AFRICA Philadelphia, August 7: The MOVE ORGANIZATION held a press conference to inform people that a week ago MOVE Political Prisoner Delbert Orr Africa was taken out of SCI Dallas and transported to an outside hospital where he has been held incommunicado for a period of 7 days. Delbert has not been allowed to call his MOVE Family or Blood Daughter. Prison and Hospital officials will not release any information to any of us on Delbert or his condition . We are highly suspicious of what's going on here. In 2015 our MOVE 9 Brother Phil Africa was taken to an outside hospital from SCI Dallas with a minor stomach virus. He was held incommunicado for a period of 5 days and upon returning to SCI Dallas he was placed in hospice care only to die a day later. In March of 1998 after recovering from a stomach virus at SCI Cambridge Springs, MOVE 9 Sister Merle Africa was told by prison officials she was dying only to die a couple of hours later. The same pattern is repeating itself here. Delbert is scheduled to go before the PA Parole Board this September and this government does not want to give ground and parole another innocent MOVE Member, that's why they are working in conjunction with Prison and Hospital officials to murder Delbert . He was arrested Aug. 8, 1978, during the Philadelphia police assault on the MOVE house in Powelton Village. Police officer James Ramp died during the 1978 police assault, likely struck by one of the tens of thousands of rounds fired by his fellow officers that day. Nine MOVE members were all found guilty of firing the same bullet and were convicted of murder, assault and conspiracy by the late Judge Edwin S. Malmed. The MOVE 9 were subsequently sentenced to 30 to 100 years in prison.” (onamove.com) Despite serving over 40 of their 30-to-100-year sentences, Delbert Africa remains unjustly imprisoned. ONA MOVE THE MOVE ORGANIZATION August 6 Audio statement by Mumia Abu-Jamal on Delbert Africa: www.prisonradio.org/sites/default/files/audio/uploads/8%2...

0 notes

Text

MOVE

What was this organization’s primary belief?

MOVE members shared the belief that “the world as we experience it is not as God intended. It is being held captive by an evil force called the System.” Co-founders John Africa and Donald Glassey authored the Guidelines, which provided members with ways to escape the System’s hold on society. Though MOVE began as a non-violent movement dedicated to living a more natural lifestyle, when they began to face aggression from the police force, MOVE felt they had no choice but to arm themselves.

What is this organization best known for?

MOVE is best known for its tensions with the Philadelphia police department, culminating in the 1985 bombing by Philadelphia police on their home. The 1985 bombing resulted in the deaths of eleven MOVE members, including five children and founder John Africa.

What are the major misconceptions about this organization?

One of the largest misconceptions perpetuated by the media of the time was that MOVE was a reactionary group rather than a religious community of like-minded revolutionaries.

When police blockaded their home in 1978 due to reports of MOVE assembling an “arsenal,” MOVE reacted in self-defense after nearly ten months of police intercepting their food and water supply. This resulted in the death of James Ramp, a veteran police officer. In retaliation, police excessively bludgeoned MOVE member Delbert Africa, an event captured in film by the Philadelphia Inquirer. Delbert Africa and eight other MOVE members were charged with murder for Ramp’s death. After 1978, MOVE’s protests shifted to focus on what they viewed as the unfair imprisonment of their family members. These non-violent protests eventually led to the 1985 bombing, when Philadelphia police once again raided the MOVE headquarters.

Who were the leaders of this organization?

Founded by John Africa, formerly known as Vincent Leaphart, and Donald Glassey, who was responsible for writing the MOVE bible, also known as the Guidelines.

What should we know about MOVE?

Due to Africa only having a third-grade education, he viewed learning to read and write as “synthetic education.” As a result, the children in MOVE were homeschooled to ensure they did not learn to read and write. Additionally, all MOVE members changed their last name to “Africa” to cement their place in the MOVE family. MOVE members viewed the organization as a family of people who had faced hardships at the hands of the System. MOVE allowed its members to unite and create the world God intended for them.

When discussing why MOVE is often framed as a cult, the fact that most members were African American cannot be overlooked. Even at the time, citizens of Philadelphia assumed that the police action against MOVE was due to racism. Though often compared to the Waco massacre, the MOVE bombing is lesser-known, and very little recorded information exists about the MOVE bombing, let alone MOVE as a religious organization.

0 notes

Photo

Delbert Africa, ¡Presente!

From Orie Lumumba:

ON THE MOVE!

MOVE’S MINISTER OF DEFENSE DELBERT AFRICA MOVED ON MONDAY NIGHT, JUNE 15th AT HOME SURROUNDED BY HIS MOVE FAMILY. WE’LL GIVE MORE INFORMATION LATER. ON THE MOVE!

THE MOVE FAMILY

This was in 2018 The last time I got to see my Big Bro . I didn't get to see when he came home in Jan due to covid and other matters but it's ok this day was priceless cause we spent it together talking about life the upcoming birth of my son so much was passed on that day and the 24 years of visits phone calls letters . My Brother is truly with me forever .I love you always Del Rest in peace

19 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Mumia Abu-Jamal, Remembering Delbert Africa (4:27), Prison Radio, June 19, 2020

Delbert Africa (April 2, 1944 – June 15, 2020)

Rest in power

On a Move

♥

#audio#control unit prison#prison industrial complex#delbert africa#rip#mumia abu jamal#free mumia#move#move organization#on a move#prison radio#2020s

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The photograph is one of the standout images of the 1970s black liberation struggle. An African American man, his hair in dreadlocks, chest bare, stands with arms outstretched as though emulating Jesus on the cross. A white police officer is jabbing a shotgun at him with the muzzle inches from his throat. Another officer clasps a police helmet in his right hand as if preparing to whack him over the head with it.

Forty years almost to the day after that photo was taken, the same black man described how he came to be standing there on a sidewalk, half-naked and surrounded by angry police. His account was almost too graphic to grasp, sounding more like something out of a movie than the recollection of what really happened in the heart of one of America’s major cities.

It was 8 August 1978 and he had just emerged from the basement of the house in Philadelphia that his black revolutionary group, Move, used as a communal home. In an attempt to evict them from the property, hundreds of officers had just stormed the building, pummeling it with water cannons and gunfire, and in the maelstrom a police officer had been killed and several other first responders injured.

“As I emerged from the basement I had the presence of mind to let them see I was unarmed, so I took my shirt off,” the black man said. “That’s when I put my arms out wide.”

The black man is Delbert Orr Africa, Del for short. When I went to meet him he was wearing a burgundy one-piece with a white T-shirt and blue shoes. Everyone else around him was wearing the same uniform of Dallas maximum-security prison in Pennsylvania that he has worn every day since appearing in that photograph 40 years ago.

I had come to interview him as part of a two-year project in which I made contact with eight black liberationists who have all experienced long prison sentences. They each agreed to embark on an ongoing conversation with me about their political beliefs today and their battle to secure their own freedom.

Del Africa, 72, and I talked for three hours in the prison visitors’ room. He spoke rapidly and intensely, as though he needed to get it all out, relating how he had joined the Black Panther party in Chicago and then switched to the Move organisation after relocating to Philadelphia.

He also told me what happened the second after that photo was taken, as though he were narrating the next few frames of a news reel. As it turns out, that police officer really had been about to whack him.

“A cop hit me with his helmet,” he said. “Smashed my eye. Another cop swung his shotgun and broke my jaw. I went down, and after that I don’t remember anything ’til I came to and a dude was dragging me by my hair and cops started kicking me in the head.”

Del Africa is one of the Move 9, the group of five men and four women, all African American, who were arrested 40 years ago this August during the 1978 police siege of their headquarters in Powelton Village, Philadelphia. They were charged as a nine-person unit with the murder of the police officer who died in the melee, James Ramp. Each was sentenced to 30 years to life, though to this day they protest their innocence.

The ranks of the Move 9 have slowly been depleted over the years. Two have died in prison. In June, the first of the nine to win parole, Debbie Africa, was released from a Pennsylvania women’s prison.

As the 40th anniversary approaches, six of the Move 9 are still behind bars, Del Africa included. They are among a total of 19 black radicals who remain locked up in penitentiaries across America having been convicted of violent acts committed in the name of black power between the late 1960s and early 1980s.

Along with former Black Panthers and Black Liberation Army members, they amount to the unfinished business of the black liberation struggle. Many of them remain strikingly passionate about the cause, even as they strive for release in some cases half a century into their sentences.

In the case of Move members, their politics are a strange fusion of black power and flower power. The group that formed in the early 1970s melded the revolutionary ideology of the Black Panthers with the nature- and animal-loving communalism of 1960s hippies. You might characterise them as black liberationists-cum-eco warriors.

That sense of passion for the cause leaps out from the first email that Del Africa sent to me from Dallas in September 2016, after I’d contacted him asking to talk.

“ON THE MOVE! LONG LIVE FREEDOM’S STRUGGLE!” he proclaimed in capital letters at the top of the message. “Warm Revolutionary greetings, Ed!”

He then launched into a long deliberation about the “plight of political prisoners here in ameriKKKa!”. Move members are still imprisoned, he wrote, “just because we steadfastly refused to abandon our Belief in the Revolutionary Teachings of Move’s Founder” and because of “our refusal to bow down to this murderous, racist, sexist rotten-ass system”. He ended with the quip: “But, hey, I don’t wanna burn you out the first time I reply to your email.”

There was a similar robustness to the first response I received in December 2016 after reaching out to Janine Phillips Africa, one of the four women among the Move 9. Unlike Del Africa’s email, she wrote to me by hand, sending the letter by mail as she has continued to do over the ensuing 18 months.

“Me and my sisters are doing good, staying strong,” was the first sentence she wrote to me. That was remarkable in itself coming from a woman who is not only approaching the 40th anniversary of her incarceration but has had two of her children killed in confrontations with police.

“Everybody knows how strong Move men are. We’re showing the world how strong Move women are. That’s how it’s been since our arrest in 1978,” she said.

In the course of that first letter, Janine Africa, who was 22 when she was arrested and is now 62, took me deep into the “torture chamber”, the cruel solitary confinement wing where she spent the first three years of her sentence.

“There were no windows, just a section of the wall with frosted panes. You couldn’t tell when it was night or day, they kept the lights on 24/7. They were ordered to break us but it didn’t work – no matter what they did, they were not going to break us.”

Over the months, I came to learn about the double tragedy in Janine Africa’s life. In 1976, Philadelphia police officers turned up at the Move house in Powelton Village having been called out to a disturbance. Scuffling ensued between some Move residents and police. Janine was shoved and her baby, whom she had named Life, was knocked out of her arms to the ground. His skull appears to have been crushed, and he died later that day in her arms. He was three weeks old.

Then on 13 May 1985, seven years after Janine Africa was imprisoned, she received further terrible news. Philadelphia police had dropped a bomb from a helicopter onto a Move house on Osage Avenue in the west of Philadelphia in an attempt to force the black radicals to evacuate the premises after long-running battles with the authorities. The bomb ignited a fire in the Move house that turned into an inferno.

Janine’s 12-year-old son, Little Phil, was being cared for in that house by other Move adults while she was in custody. The then mayor of Philadelphia, Wilson Goode, notoriously gave the go-ahead for the bombing, and the fire that ensued was allowed to rage, the blaze spreading across the black neighborhood and razing 61 homes to the ground.

Little Phil and four other children burned to death. So too did six adults including Move’s founder, John Africa, AKA Vincent Leaphart.

I asked Janine Africa how she coped with losing two young sons during clashes with law enforcement. She was reticent. “I don’t like talking about the night Life was killed,” she wrote in April. “There are times when I think about Life and my son Phil, but I don’t keep those thoughts in my mind long because they hurt.”

In that same letter she said she had turned grief into what she contests is a force for good: deeper commitment to the struggle. “The murder of my children, my family, will always affect me, but not in a bad way. When I think about what this system has done to me and my family, it makes me even more committed to my belief,” she said.

Del Africa also heard bad news on 13 May 1985. His 13-year-old daughter Delisha was also living in the Move house. She too died in the fire. When I asked him how he dealt with being told his daughter had been killed in an inferno that had been ignited by the actions of the city authorities, he wasn’t as sanguine as Janine.

“I just cried,” he said during my prison visit. “I wanted to strike out. I wanted to wreak as much havoc as I could until they put me down. That anger, it brought such a feeling of helplessness. Like, dang! What to do now? Dark times …”

Mayor Goode made a formal apology for the disaster the following year. But a grand jury cleared all officials of criminal liability for the 1985 bombing that killed 11 people, including five children.

The only adult Move member to escape the inferno alive, Ramona Africa, was imprisoned for seven years.

All Move members take the last name “Africa” to denote their commitment to race equality and their strong bond to what they regard as their Move “family”. “A family of revolutionaries” is how Del Africa once described it to me. Unlike the Black Panther party which formally dissolved in 1982, Move is still a living entity.

“We exposed the crimes of government officials on every level,” Janine Africa wrote to me. “We demonstrated against puppy mills, zoos, circuses, any form of enslavement of animals. We demonstrated against Three Mile Island [nuclear power plant] and industrial pollution. We demonstrated against police brutality. And we did so uncompromisingly. Slavery never ended, it was just disguised.”

Deeply committed as they were to each other, the Move “family” undoubtedly had the ability to incense those around them. They liked to project their revolutionary message at high volume from a bullhorn at all hours of night and day. Passersby were accosted with a torrent of expletives.

Then there were the dogs. When the 1978 siege happened, there were 12 adults and 11 children in the Move house in Powelton Village – and 48 dogs. Most of the animals were strays taken in by the group as part of its philosophy of caring for the vulnerable. Black liberation, animal liberation – the two are as one with Move. John Africa was known as the “dog man”, as he was rarely seen without one.

The unconventional nature of the Move community which drove some neighbors to despair in turn led to demands for their eviction, and ultimately to the fatal siege. Over time relations grew more belligerent. Months before the siege Move members made visible their threat to resist attempts to remove them from the neighborhood – they stood on a platform they had built at the front of the house dressed in fatigues and brandishing rifles.

On its side, the city was led at that time by the Frank Rizzo, Goode’s predecessor as Philadelphia mayor, a former police commissioner who liked to talk tough and was fond of dog-whistle politics. He once said of the Move radicals: “You are dealing with criminals, barbarians, you are safer in the jungle!” Another Rizzo classic was: “Break their heads is right. They try to break yours, you break theirs first.”

When Move refused to vacate the premises having been issued with an eviction order, Rizzo said he would impose a blockade on the house so tight “even a fly wouldn’t get in”. He was not kidding. For 56 days before the siege, a ring of steel was erected around the house, no food was permitted into the compound and the water supply was cut off. Rizzo bragged he would “show them more firepower than they’ve ever seen”.

At about 6am on 8 August 1978 the action started. Move members were battered by water cannon as they took refuge in the basement of the building. Tear gas was propelled into the house. At 8.15am shots rang out and a thunderstorm of gunfire erupted that is captured on police footage of the incident. Police and fire officers are seen scattering in all directions as bullets whistle overhead seemingly in all directions. It looked like a war zone.

Soon after Move adults and naked children began emerging from the smoke-ridden basement. Janine Africa can be heard in the police footage screaming. Next, Del Africa appears, his hands outstretched in that Jesus pose. The camera pans in on him as he lies on the street after he was hit with the police helmet. Two police officers begin kicking him on his head which bounces between them like a ball. Three officers later faced disciplinary measures but a judge dismissed the charges.

Prosecutors accused the Move 9 of collaboratively killing Ramp, even though he died from one bullet. They said the shooting had been started when gunfire erupted from the basement where the Move members were gathered, a theory supported by some eyewitnesses.

Move’s attorney gathered other witness evidence suggesting the fatal shot had come from the opposite direction – in other words, it was accidental “friendly fire”. At trial no forensic evidence was presented that connected the Move 9 to the weapon that caused the fatality. For the women in particular the prosecution did not even argue the four had handled firearms or had been involved in the actual shooting of Ramp.

Del Africa insisted when I interviewed him that though Move had guns in the house, none of them were operative. “There was no shooting from our side,” he told me. “No one in the house had any gunshot residue, none of us had fingerprints on any of the weapons they claim came out of the house.”

The Philadelphia Fraternal Order of Police has a plaque for Ramp on its memorial site. I reached out to the order many times in the course of a month to hear their reflection on his death and Move’s role in it, but they did not respond.

You can get a sense of the depth of feeling by reading the comments under Ramp’s page on the Philadelphia Officer Down Memorial website. Several commentators, some of whom vividly recalled the 1978 siege, sent blessings to the deceased police officer and his family.

Others expressed anger at the lack of justice for Ramp, though they didn’t specify what they meant. One woman, whose late husband was on duty at both the siege and the 1985 bombing, was more direct. She said of Ramp: “I was so sad to hear of your passing. I felt, and still do feel so badly for your family. Move were scum and cowards, hiding as they shot. You were SO brave. Never forgotten. RIP.”

As they approach the 40th anniversary of the siege and of their subsequent captivity, Del and Janine Africa described to me how they’ve coped for so long doing time for a crime they insist they did not commit. They each have their own survival methods.

Janine Africa told me she avoids thinking about time itself. Birthdays, holidays, the new year mean nothing to her. “The years are not my focus, I keep my mind on my health and the things I need to do day by day.”

Del Africa thinks of the eons behind bars not as “prison time” but as “revolutionary prison activity”. “I keep saying to myself: ‘I will not fall apart. I will not give in.’”

They’ve both experienced long stretches in solitary confinement, a brand of punishment that the UN has decried as a form of torture. In 1983, Del Africa was put into the “hole” – an isolation cell – because he refused to have his dreadlocks cut.

He stayed in the hole for six years. He relieved the stress and boredom by organizing black history quizzes for other inmates held in the isolation wing. Russell Shoaltz, a former Black Panther, helped him devise the questions, and shout them out down the line of solitary cells. Questions such as: when was the Brown v Board of Education ruling in the US supreme court? What year was the Black Panther party founded? Who was Dred Scott? For what is John Brown remembered?

Eventually Del Africa won the right to keep his dreads. When I visited him in Dallas there they hung, salt-and-peppered now, proudly down to his hips.

Throughout, the Move prisoners have drawn strength from companionship with other members of the nine. Janine shared a cell with two other surviving Move women – Debbie Africa and Janet Holloway Africa – in Cambridge Springs women’s prison in Pennsylvania. They called each other “sisters” and did everything together. “We read, we play cards, we watch TV. We laugh a lot together, we’re sisters through and through,” she wrote in a letter in February.

There was one other member of their gang: fittingly given the history of the organization, a dog called Chevy. The prison authorities let them keep the dog kenneled in their cell as part of a program in which they train the animal for later use as a service dogs for disabled people.

Life went on like this for years, and had acquired its own normality, almost a certain tranquility. Until last month when Debbie Africa was granted parole and set free. Her departure came as a jolt.

“It’s strange not having Deb here,” Janine said. “I keep expecting her to walk in from work. They snuck her out at 5.[:]00 in the morning. We only got to hug her briefly and watch her leave. Chevy misses her, he keeps sniffing her bed.”

In June, Janine and Janet Africa also went before the same parole board as Debbie and made essentially the same case that they had earned their freedom. The board asked Janine whether she would be a risk to the public were she to be let out, and she referred them to her pristine prison record: the last time she had any disciplinary rap was 26 years ago. “The way I’m in here is the way I’ll be outside, there is no risk factor,” she told them.

While Debbie was set free, both Janine and Janet had their parole denied. The board said they showed “lack of remorse” for the death of Ramp in the 1978 siege.

Janine Africa wrote to me a few days after she learnt of the denial, speculating that games were being played with her mind. The contrast of Debbie’s release with her denial was “either to make us resent Deb or make me feel hopeless and break us down. Whatever their tactic, it isn’t working!”

Debbie’s release also made a profound impact on Del Africa. “I feel overjoyed that Debbie is out,” he wrote to me. “Her release is a breakthrough! I see it finally opening the door a crack.”

Del Africa also hasn’t had a misconduct report in prison for more than 20 years. Yet he too was turned down for parole last year and must wait another four years before his next chance to convince the parole board that he can safely be returned to society.

Like many of the 19 black liberationists still behind bars, Del Africa is caught in a trap attached to the crime for which he was convicted. He knows he will only be paroled if he expresses heartfelt remorse. But says he cannot do that.

“How can I have any remorse for something I never did?” he said. “I had nothing to do with killing a cop in 1978. Have they shown any remorse for what happened to my daughter in 1985?”

Would he show remorse to the parole board if he felt it would secure his release?

“No, never going to do that,” he said. “That would be akin to making them right. They are the ones who were wrong.” [x]

Photograph:

The arrest of Delbert Africa of Move on 8 August 1978

Debbie Africa was released in June after 40 years in prison

Members of Move gather in front of their house. They were arrested 40 years ago during a police siege.

Janine Africa preaching to the crowd in front of the barricaded Move house in the Powelton Village section of Philadelphia

Move members hold sawed-off shotguns and automatic weapons as they stand in front of their barricaded headquarters

Debbie Africa and her son, Mike Africa, whom she gave birth to in her prison cell a month into her incarceration. She was released last June.

#move#move 9#philly#philadelphia#amerikkka#police brutality#black power#delbert africa#del africa#delbert orr africa#debbie africa#powelton village#james ramp#black liberation#black panthers#black liberation army#janine phillips africa#janine africa#wilson goode#john africa#vincent leaphart#lil phil#ramona africa#frank rizzo#philadelphia fraternal order of police#racism#white supremacy

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

HOLLYWOOD PRIEST: How Father Bud Brought God to Television—And Vice Versa

HOLLYWOOD PRIEST: How Father Bud Brought God to Television—And Vice Versa

View On WordPress

#Albert Brooks#Ann B. Davis#Anne Francis#Arthur Hiller#Barbara Hale#Bill Bixby#Bob Newhart#Brian Keith#bud kieser#cardinal romero#Carol Burnett#Carroll O&039;Connor#Catherine Hicks#catholicism#celeste holm#central africa#christine avila#Cicely Tyson#delbert mann#Dick York#Ed Asner#ed begley jr.#ed begley sr.#efrem zimbalist jr.#Elisha Cook Jr.#Elizabeth Ashley#eric andrews#Harvey Korman#hollywood priest#humanitas prizes

0 notes

Text

Philadelphia MOVE 9 member Delbert Africa released from prison on parole, 42 years after cop's death

Philadelphia MOVE 9 member Delbert Africa released from prison on parole, 42 years after cop’s death

[ad_1]

One of the Philadelphia MOVE 9 has been released on parole after almost 42 years in prison for a crime he maintains he did not do.

Delbert Orr Africa emerged from State Correction Institution – Dallas in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, with his arms splayed resembling the shape of a cross, four decades after he first held the Christ-like during a deadly police siege of 1978.

The freed man,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The People for Mumia, a virtual event April 23, kicked off the weekend. Activists, musicians, writers and youth shared why Mumia is important to their movement for social and racial justice. Speakers and performers included Mike Africa Jr., Susan Abulhawa, Angela Davis, Marc Lamont Hill, Robin D.G. Kelley, Colin Kaepernick, Tom Morello, Albert Woodfox, Erica Caines, Santiago Alvarez, Monica Moorehead and more.

On April 24, over 1,000 people gathered in Philadelphia for a rally and march. “Taking It to the Streets for Mumia” began at City Hall across from where the statue of racist Frank Rizzo was removed in 2020 due to public outcry against his brutal legacy.

Dr. Johanna Fernandez spoke against the corrupt legal system and explained how the Philadelphia police worked “hand in glove” with the prosecution and racist judge in Mumia’s 1982 trial. Evidence has surfaced indicating the prosecution bribed a key witness.

Pam Africa gave news of Mumia’s health, after having spoken briefly with Mumia earlier in the day. He is still hospitalized, but said he is beginning his recovery by taking some short walks. He confirmed he is shackled while in his bed. Mumia’s medical advisor Dr. Ricardo Alvarez traveled from California to speak at the event.

Mumia’s brother, Keith Cook, traveling from North Carolina, told the gathering that they must continue to fight until his brother is free. YahNé Ndgo, Immortal Technique and Ellect performed, and the crowd sang along to Stevie Wonder’s “Happy Birthday.” Speakers included Chairman Fred Hampton Jr. and Immortal Technique.

Susan Abulhawa connected the struggle for Black liberation with the free Palestine movement. Her thoughts about Mumia’s character and spirit inspired: “Mumia teaches us what it is to be free in our minds. He was a Black man who was too free, and that is why they locked up his body.”

Dr. Suzanne Ross spoke about the U.N. Human Rights Commission’s support for Mumia. Events calling for Mumia’s release were held in France, Germany, Mexico, French Guiana, Britain and the Netherlands, and in several U.S. cities April 24.

A powerful moment came when Janine Africa, Janet Africa, Sekou Odinga, Jihad Abdul-Mumit and Kazi Toure, five liberated political prisoners, stood together on the stage. The group has spent a combined over 150 years behind bars.

The rally moved into the streets for a spirited march from City Hall to the Art Museum, carrying banners and signs and shutting down traffic along the Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

The march stopped at the site of last year’s houseless encampment, calling attention to the city’s inability to provide basic services to the most vulnerable. Fired by Amazon for speaking up for workers rights, Chris Smalls, with the Congress of Essential Workers, called for support of Amazon workers organizing. The rally continued on the Art Museum steps.

Larry Holmes spoke about how Frank Rizzo, “the most racist police chief,” waged war on the Black Panthers, MOVE and the entire Black community in Philadelphia. Janine Africa warned that we must not let the police kill Mumia like they killed the incarcerated MOVE family members Phil Africa and Merle Africa. Delbert Africa was freed, but succumbed only six months after his release to illness caused by inadequate health care during his incarceration.

Performers included Dominque London and the Universal African Dance and Drum Ensemble. Basiymah Muhammad Bey from the United Negro Improvement Association also spoke.

Travelling from Boston mYia X raised the memory of Winnie Mandela and Shaka Sankofa and borrowed from the words of Ella Baker, saying “We who believe in freedom, cannot rest until we bring Mumia home.”

Jamal Hart, Mumia’s grandson, called on the younger members in the crowd to take up the fight to free Mumia. Calling for his grandfather to spend his next birthday surrounded by his family and friends, he chanted: “No more birthdays in prison.”

The coalition sponsored events in West Philadelphia April 25 honoring Walter Wallace Jr., murdered by Philadelphia police six months ago in 2020, and Russell Maroon Shoatz, imprisoned since 1972 and suffering from stage 4 cancer. Members of Shoatz’s and Wallace’s families participated in the event that kicked off a community cleanup at the Maroon Garden, followed by a march to Malcolm X Park for a speakout.

Food Not Bombs Solidarity provided snacks and water for the events on both days.

Visit LetMumiaOut.com or Mobilization4Mumia.com for more information on Mumia’s health, endorsers or upcoming events.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Delbert Africa was released from prison today! Continue supporting him as he transitions to life outside of the carceral system.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

种族与美国的社会运动版图(修订发言稿)

这是7月4日在湾区文化沙龙做的分享的修订文字版本,在保留原意的前提下调整了口语化的表达,因为没有影像,所以还新加了一些讲座中没有的图片。澎湃版本为:https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_8175114 因本人疏忽澎湃版本为最后第二稿而非本博客版本,但除漏了两个参考文献外,两者内部差别不大不影响阅读。

今天分享的题目是种族与美国的社会运动版图,主要包括三部分内容。第一部分主要涉及为什么特定的社会抗争和国家暴力的历史被淡化甚至抹除,以及民权运动衰落后黑人权力运动对民权运动意识形态的挑战和超越。其次会梳理美国左翼运动中的种族问题,移民所激化的种族与阶级矛盾如何在过去一百多年不断撕裂美国的激进主义传统。最后我会分享针对这一波BLM的公众舆论和运动的三个主要特征,然后从这些特征里我们也可以瞥见历史上黑人运动的遗产。

社会运动与黑人解放的公众记忆

今天人们谈论社会运动的时候,他们不仅仅在谈论运动本身,而更是在塑造一种历史视角,一种事后理解和记忆运动的方式。所有的社会运动都同时是被传媒体系和学术研究过滤的,过滤过的事实会被印刻成历史成为一种公众记忆和政治论证的文本被不断唤起。

比如1960年代中期出现的黑人权力运动,直到现在都没有很多影像记录和学术研究。唯一较为完整的纪录片是瑞典电视台记者拍的The Black Power MixTape, 记录了1967到1975年间和黑人权力运动相关的一些零碎的影像,十年前整理成片在美国上映,但因为有很多素材遗漏,一些年份甚至完全没有素材,所以整个视角不是很全面。但60,70年代没有一家美国媒体愿意去深入采访黑人权力运动,所以连纪录片都是外国人完成的。而且当时瑞典的拍摄团队还受到了多方阻拦,被美国政府和媒体机构批评传播负能量,看不到美国社会进步的一面。

美国社会对社会运动的记忆僵化而存在极强的种族偏见。首先社会运动历史有很强的白人中心主义。大量研究都聚焦在白人主导的运动,比如新左派运动。同理,有中文翻译版的书籍也基本都局限在新左派运动。还有大量研究是关注民权运动期间的一些运动,比如静坐抗议Sit-in如何影响南方白人的态度。这个不言自明的假设在于黑人运动的成功要由白人来定夺。此外,白人男性也主导着历史叙事。新左派的回忆和论述被白人核心参与者所垄断。社会运动研究作为一个跨社会学、政治学的子学科,内部的种族和性别分化也极为严重。且不说理论研究三大家蒂利、塔罗和麦克亚当都是白人男性,几乎没有有色人种女性活跃在这个领域,她们一旦从事类似的研究,也会被学界的本质主义思维看作仅仅是研究种族、女性,而不是研究广义社会运动的学者。一般的社运研究者,也绝少有自己亲身参与运动组织工作的,研究和社运实践间常有巨大的脱节。

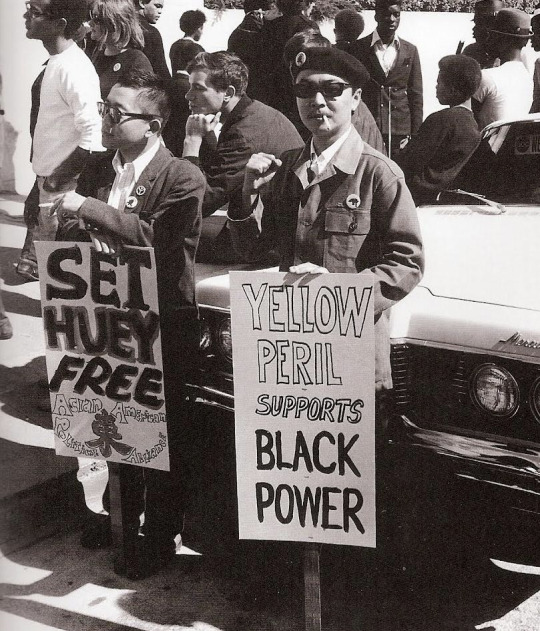

前面这两个因素当然也受制于一个重要的结构性问题,即��会运动历史档案上的偏见。白人运动和比较温和的黑人运动参与者的记录更完备。Doug McAdam有本代表作叫《自由之夏》,这本书讲述参与1964年自由之夏项目对志愿者人生的长期影响,他们参与以后怎么开始思考改变社会,在今后的人生中更多参与政治。但麦克亚当之所以可以写这本对社运研究几乎是奠基性的书,正是因为自由之夏九成志愿者都是白人,然后档案资料非常齐全完整。黑人组织,特别是激进黑人运动的资料一个非常零散,二来很多掌握在FBI和CIA手里,即使资料解密也要等好多年。新曝光的故事也会颠覆人们的认知,比如当年黑豹党唯一做到高层的日裔美国人Richard Aoki,也是Yellow peril supports black power那张著名图片中的东亚男性,2012年才被曝光其实是长期的FBI线人,他成功打入多个组织内部,为美国政府提供了无数重要情报。

图右为Richard Aoki,他生前拒不承认和FBI有关

具体到50年代开始的黑人解放运动上,它历史呈现的问题就更为集中。我这里总结了五点。首先是以领袖为中心的记忆和分析,特别是在阐述黑人运动分歧的时候会调出MLK和马尔科姆X,似乎其他人的运动都是这两个人的注脚。即使谈论别的组织的时候,也存在这个问题,比如一说到黑豹党就联想到Huey Newton,而不太关注其他成员,特别是女性成员的贡献。

第二个问题是国家镇压被大量淡化。最典型的例子是50-70年代FBI在胡佛任下违法的COunter INTELligence PROgram,简称COINTELPRO。这个项目跟踪民权运动、新左派、黑人权力运动和激进左翼里大大小小的组织。FBI也直接策划了黑豹党非常有潜力的新星Fred Hampton和他保镖Mark Clark的刺杀。当时Hampton只有21岁,组织了一个非常有潜力的跨族裔联盟Rainbow Coalition,邀请了各个族裔的激进组织加入。这场官方拒不承认的谋杀也是黑豹党解体的主要原因之一。除了暴力镇压外,官方还通过伪造通讯等方式来对黑人运动各个击破,比如他们会伪装成其他组织的成员写信辱骂黑豹党,挑起组织之间的不信任,或者大肆宣扬某人是FBI或者CIA线人,这种策略也被叫做Bad-jacketing。FBI的COINTELPRO项目之所以为人所知,是因为1971年有八个行动者潜入了宾州FBI的地区办公室偷走了一千多个文档,这些行动者后来把文档全部公布给了主要媒体和国会,否则相关信息要晚几十年才会解禁。如今虽然FBI的监控和镇压受到一定程度的制约,它们旗下依然有专门的针对黑人激进派的监控项目,比如2017年泄漏的文价显示FBI把BLM看作“Black Identity Extremism” Movement的一部分,但这个运动完全是他们杜撰出来的。

在主流的论述中,黑人激进主义一直被认为是暴力的,分离主义的,引发社会撕裂的。即使是民权运动的支持者也往往持有这样的立场。比如Todd Gitlin等白人新左派一直以来都声称黑人激进派毁掉了民权运动族裔团结的改革成果。他们还认为黑人激进派背叛了民权运动,从而导致70年后代保守主义和文化战争的兴起。但其实真的去看60,70年代历史,会发现60年代的运动在当时未必弥合了社会分歧,那些黑人白人并肩作战的图景本就有很多浪漫化的成分,而反而被认为是分离主义的黑人激进派在70年代后做了很多族裔团结的工作。

黑人运动历史里女性,特别是底层女性的参与一直是被淡化的。比如知道Claudette Colvin 的人远远少于 Rosa Parks的,尽管前者才是第一个拒绝给白人让座的人。因为相比Colvin,Parks更符合抗争者的刻板形象,她是一个已婚的制衣女工,又在当地的NAACP任职,所以当时NAACP有意把她塑造成领袖。但Colvin是一个让座后不久就怀孕了的15岁单身黑人女性,她的身体是被社会污名化的,当时哪怕在黑人社区也没有一个行动家愿意宣传她的事迹。另外,Angela Davis在很多不同场合也提到过无数普通黑人女性的抗争造就了MLK,比如当时蒙哥马利公车抵制一开始是黑人女性组织发起的,而且搭乘公车的也大量是需要通勤的服务业黑人女工,但后来的历史叙述更多强调的是MLK等人事后介入的组织工作,MLK也因此成为了民权运动的核心人物。社会学家Belinda Robnett的研究还揭示,民权运动时期绝大部分黑人组织和黑人教堂普遍排斥女性的核心领导位置,黑人女性最多只能提拔到中层。所以组织内的排斥反向刺激她们去做更多协调、联络、教育的工作,成为了链接不同社区的节点。当时SNCC就是学生非暴力协调委员会的创办者Ella Baker就是个很好的例子,她做了很多运动的幕后工作,包括挖掘和培养下一代行动者。由于非常反感克里斯玛式的领导人气质,她更亲草根行动的风格也让她在民权运动的记忆中处在更边缘的位置。

最后一个问题是美国在任何话题上都非常擅长的美国中心主义。除了越战外,历史叙述很少把美国置于全球运动和冷战的框架下看。进入21世纪后这方面的论述多了很多,但总的来说还是十分不够,而且既有的论述很多都比较第三世界浪漫主义,没有太多分析60,70年代国际主义面向下更复杂的政治运动之间的博弈。

美国对六十年代的论述经常被置于一种简化的“Good Sixties/Bad Sixties”的二分,大概就是说六十年代的前半段是好的,运动都很非暴力,在体制框架内进行,也获得了一些民权上的进步。到了六十年代后期黑人权力运动兴起,一切都划向了暴动和骚乱。关于60年代这种二分法记忆如何被固化的著作也很多。第一本叫做Framing the Sixties, 是从政党政治的角度看两党政治人物怎么唤起60年代的记忆来为自己政党的议程服务。第二本书The Bad Sixties对80、90年代的影像作品做了分析,发现主流文化界通过突出好的60年代和各种白人亚文化产品,来有效消解黑人运动的政治性。大家可能会一边欣赏黑豹党的着装,认为他们开创了一种时尚潮流,一边反对他们背后黑人自决的意识形态。第三本书A More Beautiful and Terrible History则反思了美国社会如何通过纪念民权运动来推卸奴隶制和种族隔离的历史负担。民权运动被描述成一种美国社会的自我净化和救赎,为之后的色盲政治 (Colorbindness)铺路。

黑人权力运动的崛起和遗产

尽管民权运动时期就有了黑人权力的思潮,但是整个运动崛起还是在1960年代末期特别是1968年以后。对主流民权运动和SNCC在选举政治上努力的失望,从马尔科姆·X到MLK和肯尼迪的被刺杀所引发的普遍绝望情绪是很直接的诱因。越战也为黑人激进思潮的传播创立了机遇,因为第一次黑人,尤其是参战黑人直观感受到自己作为被压迫者,和被屠杀的越南人命运是相连同构的。前SDS成员Max Elbaum在Revolution in the Air里引用过一个60年代末的调查,显示30.6%参军的黑人希望回到美国以后加入一个类似黑豹党的激进黑人组织。

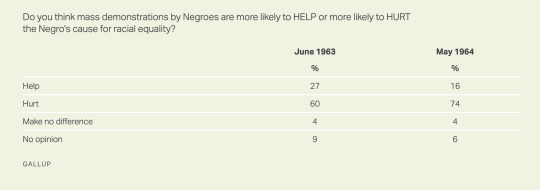

人们事后回望60年代的时候往往忽略的一个背景是,当时即使是早期MLK这样的温和立场,美国社会上支持他的人也是极少数。1966年其实只有28%的美国人对金有好感,说明民权运动在当年是绝对不具备舆论基础的。1961年五月底盖洛普针对刚开始的跨州Freedom Riders运动的调查,六成被访者都持反对态度。更能说明问题的是1963年March on Washington前后的舆论对比,黑人非暴力游行后,社会反而对黑人运动更抵触了,认为非暴力抗争伤害种族平等的比例从60%飙升到了74%。1966年的数据呈现同样的趋势,85%的白人都觉得民权运动伤害了黑人追求平等。所以很多白人新左派宣称的美国社会舆论因为黑人权力才走向保守的论断是站不住脚的。种族资本主义的捍卫者不会因为一个社会运动和理非而对它寄予更多的同情。所以是一直以来都十分坚固的白人至上思潮推动了黑人权力的崛起,而不是反过来的。

1963年March on Washington之前和半年后的舆论对比

一般认为最早的黑人权力组织是Revolutionary Action Movement(RAM),虽然当时并没有Black Power这个概念,但这个组织在黑人高校发展开始就一直强调全世界黑人的解放,它也比黑豹党更早接触到毛主义和列宁主义。因为RAM活跃的时期还在民权运动鼎盛时期,所以他们为了避免国家镇压一直是半地下工作,也导致这个组织虽然实际规模很大,旗下很多分部,但资料留存下来的非常少,很多都来源于CIA和FBI的档案。比如后来根据Freedom of Information Act公布的60年代CIA资料就显示他们被官方认为是当时最危险的组织。RAM也激励了马尔科姆x和黑豹党的创办,前者在伊斯兰国度之前是RAM的成员。

提出黑人权力这个概念的是Stokely Carmichael,他是在1966年March Against Fear中一场密西西比的集会上喊出这个口号的。早年他也是支持民权运动的温和派,参与过Freedom Riders运动,受到前述提到的Ella Baker影响,也领导过SNCC,但60年代中期他基本已经对民权运动的路线不再抱有幻想。Stokely喊出黑人权力的口号后,大部分民权运动领袖十分恐慌。当时的NAACP主席Roy Wilkins直接说这是”the father of hate and the mother of violence”,MLK也认为这个口号“unfortunate”,让Stokely收回,后者严词拒绝了。这种路线分歧除了时代变迁因素外,很大程度上也是代际问题。Stokely是1941年出生的,MLK是1929年,差了十几岁,所以Stokely回应的时候说我很尊重金博士,但是我们年轻人��没有他的耐心。在金被刺杀前Stokely和他还是有一些策略上的合作,但Stokely在立场表达上从未妥协过。

CIA解密档案中提到的1967年的Stokely发言,来源于:https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP83B00823R000800050002-3.pdf

MLK与马尔科姆·X的不同,民权运动和黑人权力运动的分歧经常被简化成是否接受暴力。但更本质的不同在于看待黑人解放的途径,究竟是要求白人国家给自己赋权和法律地位,还是自己夺取和定义自由。Malcolm X最著名的话之一就是“Nobody can give you freedom”。同时,黑人权力运动应该被看作一种网状的弥散式的结构,内部有很多不同的派别。有些组织支持黑人分离主义和独立建国,还有一些组织会信仰革命社会主义,一些组织,像伊斯兰国度有宗教色彩也不排斥资本主义,比如他们会支持黑人企业家创业。但黑人权力运动在整体的脉络上还是偏左翼,还是有一些共同的特点可以将之和民权运动区别开来。

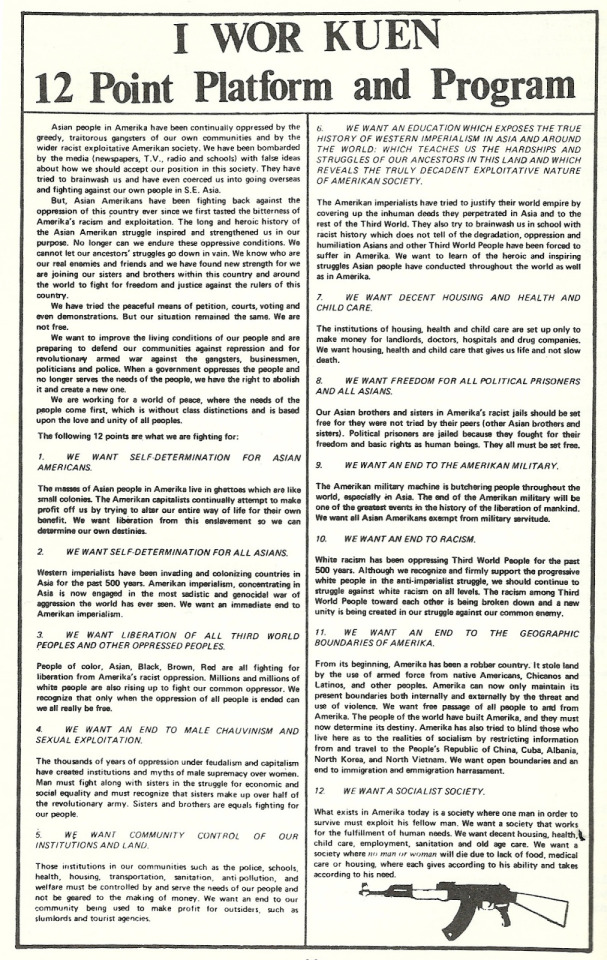

首先,黑人权力大大拓宽了民权运动的范畴。因为民权是相对自由较为狭窄的概念,后者还包括在经济、教育、医保、住房等一系列面向上的平等。非常典型的例子就是黑豹党1966年起草的纲领性文件ten-point program,涉及免费医疗、教育、廉价住房和黑人免服兵役等问题,他们资金充裕的时候也一直在实践各种社区医疗教育治安项目。这种激进社区实践不只是内部试点,也激励了其他族裔的激进组织,比如另外一个纽约的亚裔激进组织I Wor Kuen (IWK,义和拳) 就有12-point program,而且它们的纲领相对黑豹党的有更强的性别意识,可能是美国所有激进组织里面最明确提出反对男性沙文主义的。

IWK的12点项目全文,来源于:https://asianamericanactivism.tumblr.com/post/68946140266/i-wor-kuen-12-point-platform-and-program-i-wor

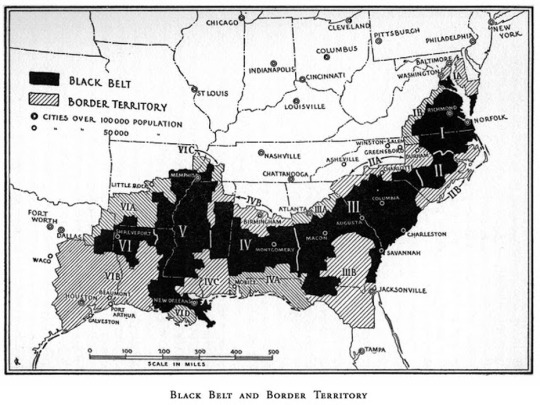

民权和黑人权力第二个根本性分歧和很多对于移民的争议是类似的,即美国的移民需不需要逐步融入白人社会,还是可以保持自己的生活方式和政治。而黑人权力在保留自己族裔文化政治的情况下,进一步讨论了自决和独立的问题。一个典型的支持黑人自决的激进组织是1968年在底特律成立的新非洲共和国(RNA),RNA希望五个黑人人口占比高的南方州路易斯安那,密西西比,阿拉巴马,佐治亚和南卡独立建国,向美国索取每名黑人一万美金的奴隶制赔偿,等价于美国重建时期对黑人未兑现的许诺,同时请黑人投票自行决定是否加入新的国家。RNA计划定都亚特兰大,还选了当时在中国流亡的黑人运动家Robert F. Williams当临时总统,国旗则模仿美国的设计但是采用泛非主义的红、黑、绿三色。这些纲领现在听上去很不可思议,但当时这样的思潮绝对不是毫无社会根基的。RNA成立初期全国媒体关注度很高,这个组织在政治打压下也一直存活到了90年代。针对RNA的研究非常少,唯一一本著作是政治学者Christian Davenport的How Social Movements Die,分析RNA在国家镇压和内部派系分裂前逐渐衰落的过程。

RNA计划的国土范围,来源于:https://christiandavenportphd.weebly.com/republic-of-new-africa.html

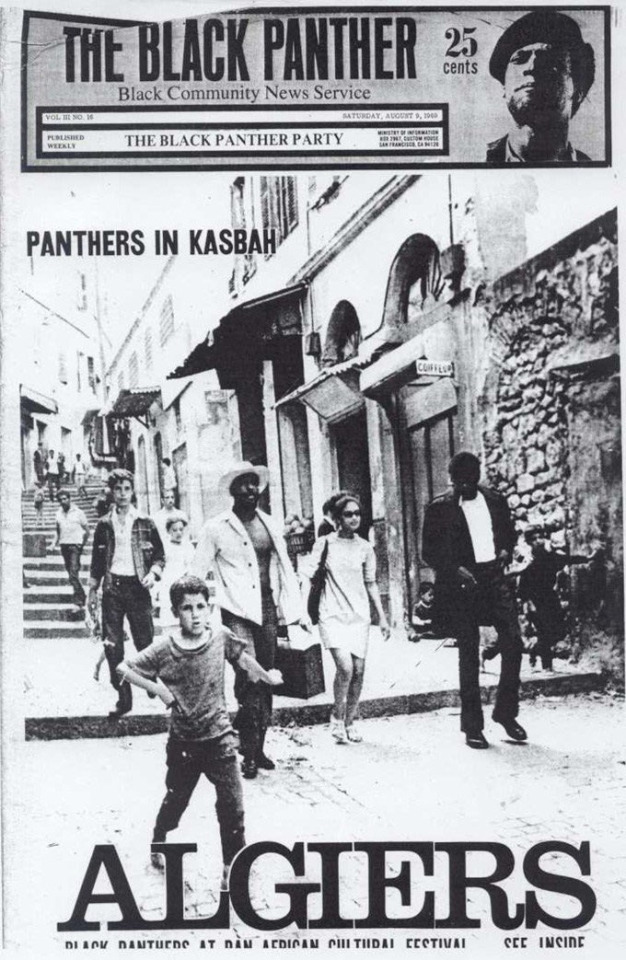

第三类分歧在于国际主义的程度。MLK自己当然也会说全世界人民的解放是重要的,但只有黑人权力运动真正建立了事实上的组织联系。比较典型的例子是黑豹党在阿尔及利亚的故事,这段历史目前最完整的叙述来源于Algiers, Third World Capital这本书。黑豹党的信息部部长Eldridge Cleaver 60年代末逃避审判流亡到阿尔及利亚,一开始受到新政府的欢迎成立了支部,对方还提供了办公场所。虽然BPP在海外只有这么一个分部,他们通过阿尔及利亚做了很多国际联络的工作,他还长期受到北越政府的资助。但随着时间发展黑豹党的分部和阿尔及利亚政府就产生了很多理念和资金上的冲突,后者一直希望把前者纳入自己自上而下管理的体系,还两次收缴了海外给黑豹党的大量资助。所以从这个案例也可以看到,一方面黑人权力运动的国际视角比民权运动要宽广许多,但是另外一方面很多国际连结内嵌在当时全世界的民族解放结构和美国国内对黑人运动的镇压里,这个外部条件的涨落还是很关键的。

黑豹党党报对阿尔及利亚分部的报道,来源于:https://twitter.com/SanaSaeed/status/1279926765150928896

为黑人权力运动提供国际背景的泛非主义存在三个重要的时间点。从宽泛的意义上说,18世纪末的海地革命就有了泛非洲主义的色彩。当时海地起义军甚至和大革命中的法国普通市民有了跨大西洋的团结。这在CLR James早年的著作《黑色雅各宾》里面有很细致的描述。现代泛非运动大概出现于19世纪末20世纪初,那时候全世界激进思潮的传播都很快,从无政府主义到共产主义。同一时期黑人激进派建立了很多跨国组织,都致力于全世界非洲裔的解放。当时虽然交通没有现在便利,但现代签证制度还没有建立,像美国是1924年随着颁布限制亚洲移民的Johnson–Reed Act才有了签证,所以运动家跨国迁徙和流亡某种程度上更为容易。本尼迪克特·安德森在《全球化时代》���提到那时候具备的所谓早期全球化特征,电报、万国邮政联盟、蒸汽船和铁路建设都有利于跨国人口流动。到上世纪60年代的时候伴随亚非拉民族独立运动,已有的泛非思潮正好和黑人权力运动对接起来,所以黑人权力运动里面不少人物后来也都参与了泛非运动,包括Stokely自己,他甚至为纪念泛非运动改名为Kwame Ture。

牙买加人Marcus Garvey是早年泛非运动非常重要的人物,他1914年创办了最早的泛非运动组织Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL),当他移民到美国以后又在纽约哈勒姆建立了分部。加州奥克兰有个非常著名的黑人激进主义书店叫Marcus Book就是以Marcus Garvey命名,这次BLM抗议他们书店也收到了很多捐款。另一个重要组织是1968年由加纳流亡运动家恩克鲁玛成立的All-African People's Revolutionary Party,后来1972年也有了美国分部,Stokely1969年逃亡非洲以后就长期负责这个组织。所以社运的国际联系并不一定是从欧美开始辐射向全球的,很多都是在其他地区先发起然后通过国际移民传到了美国,这种边缘到中心的模式关注的人较少。

很多泛非运动的人其实都出生在加勒比地区,Stokely也是出生于特立尼达和多巴哥。加勒比行动者和美国社会运动的互动远远早于民权运动年代。比如20世纪初,就有很多加勒比的激进无政府主义者在纽约建立和参与了激进劳工和族裔解放组织,他们在哈勒姆文艺复兴中也扮演过很重要的角色。除了之前提到的早期全球化的趋势,历史学者Winston James这本Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia里面分析到另一个很重要的原因,就是加勒比、西印度群岛的黑人移民,相对美国本土的黑人平均教育程度更高,阶级意识更强,同时他们在移民到美国前对种族隔离的感受不深。这些人到美国以后接触到白人才开始有了黑人的意识,但同时他们相对本土的黑人激进主义者更愿意和白人激进劳工运动家合作。也就是说加勒比的黑人激进派从Marcus Garvey到CLR James成为了美国白人激进派和黑人激进派间的桥梁,可以把种族和阶级的议题一起融合到解放性政治里头。这点非常关键,我在后面谈到左翼运动的种族问题时候还会进一步解释。

虽然上述提到的很多黑人权力组织已经不复存在,但他们以往的成员和后代现在往往还活跃在社运一线,或是就现在的运动提出自己的看法。也有很多人创办了非政府组织。所以如今各个城市的运动经常还能带上当年运动的特色。我这次讲座封面图片作者Emory Douglas前几年拜访墨西哥萨民解驻地,和行动者对谈艺术和政治行动的关系,他们的对话成果还出版了书籍Zapantera Negra。

黑人权力运动内部的意识形态多元而庞杂。黑豹党、伊斯兰国度、新非洲共和国等组织获得了大部分媒体关注,但其实还有很多小的组织。因为我住在费城,所以分享下本地一个很著名的黑人激进组织MOVE。MOVE1972年成立,除了黑人自决解放的纲领外,还有很强的绿色无政府主义色彩,比较反对工业化,有些历史学者认为他们受牙买加拉斯塔法里运动的影响。这个组织本来是很低调的,就在费城西边买了一排楼,组织成员过自治公社式的生活。但是78年的时候和费城警方对峙的时候,一名警察后颈被子弹击中身亡。为此费城警方坚称是MOVE方面开的枪,MOVE说他们的枪都是坏的不可能走火,是其他警察扫射到死者。官方没有给MOVE太多辩护机会,重判了九个人谋杀,大部分人刑期判了40多年,媒体把他们叫做MOVE9。目前这些人要么在监狱去世了,要么2018年以后才被释放,最新的情况是一位被判42年的成员Delbert Africa今年一月才被释放,六月就癌症去世了。

1985年的时候MOVE和警方再次发生冲突,由于警察没法让成员离开住所,他们就索性出动了直升机向MOVE的住所扔了炸弹,炸弹当时引发了现场大火,造成6名主要MOVE成员和5个未成年人死亡,60多栋房屋受损。2013年的纪录片Let The Fire Burn是关于MOVE和警方的冲突,片名就暗示说当时警方意识到房屋着火后,故意让消防车不要实施救援,等着火把MOVE成员吞噬。最后这场屠杀没有一个警官被审判。这场悲剧一方面导致MOVE基本被摧毁,另一方面也反向刺激了黑人权力思潮在费城的延续。这次费城BLM游行中,也可以看到关于MOVE的标语。

1985年MOVE爆炸现场的浓烟,来源于:https://thephiladelphiacitizen.org/the-lingering-trauma-of-move/

60,70年代任何社会运动都沾染了性别主义的色彩。黑人女权艺术家Michele Wallace写过一本当年争议极大的书Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman,因为这是第一本揭露黑人权力运动内部性别压迫的书。她认为黑人权力运动的厌女情节体现在运动强化了noble warriors 或者是 elderly statesman形象,要么是高贵的战士要么是年长的发言人,都是非常强调男性气概的。而且很多运动组织本身一直在强调要恢复黑人男性在社会的主导地位。这其实是对1965年一份著名的调查Moynihan’s The Negro Family的反击,当时这份报告认为黑人群体内部占四分之一的单亲母亲家庭导致了黑人过多依赖福利制度,经济文化上陷入落后的恶性循环。这份报告撰写人Moynihan本人其实写到了奴隶制以降的系统性歧视才是导致黑人家庭瓦解的原因,但后来这份报告完全被曲解逆练成为了保守派宣扬黑人“贫穷的文化”的证据。黑人权力运动针对这种污名化,等于是用一种同样扭曲的,牺牲黑人女性自主性的方式做出了回应。

黑豹党内部的性别歧视就很能反映问题。Elaine Brown写过一本回忆录叫A Taste of Power,她是1974-1977年黑豹党陷入危机时候的负责人,因为领导人Huey P. Newton为了逃避审判流亡了古巴所以指定她接任。当时黑豹党的影响力已经消退,创办者之一Bob Seale已经因为内部分歧退党,组织成员各奔东西,剩下不到100人。Elaine在非常不利的局面下其实做了很多组织工作,包括拓展已有项目,增强和其他组织和政客的合作,极大延长了黑豹党的寿命。但后来大家在回顾黑豹党历史的时候,也倾向于完全忽略女性成员的贡献。Brown在回忆录里直接指出黑人女性在黑人权力运动中被认为无关紧要的。即使女性作为领导人,也被认为伤害了black manhood甚至黑人这个种族本身。

除了Elaine的回忆录外,The Revolution Has Come是黑豹党历史书里比较有性别意识的一本。尽管鼎盛期黑豹党成员六成是女性,总部和绝大部分分部的性别分化和歧视是非常严重的,比如后勤联络、教师和办报纸几乎都由女性操办,主要领导层历史上只有三个人是女性,而且都是因为和男性成员有亲密关系才被提拔。早期女性和男性的职位晋升渠道是完全分开的。组织内部集权也很严重,不同意Newton的人会被开除。这本书里说到一个非常有意思的现象是在组织发展后期,由于女性成员的贡献长期被忽视,她们不被上门来搜捕的警察认为是关键人物,于是长此以往组织里的男性都被抓走,女性终于得以填补空白进入管理层。这个和之前提到的黑人教堂排斥女性,催生她们成为社区层面的召集人的例子异曲同工,都是社会结构性歧视如何塑造女性运动家独特的政治抗争模式。

当然并非黑人权力运动就格外排斥女性,事实上民权运动和新左派运动里性别歧视是更常见和直白的。自由之夏项目招募学生的时候,筛选女性参与者一条很重要的标准是外貌。后来McAdam做研究时候意外翻出当年的档案,发现负责人在审查申请者资料时候一直在评论女申请者的长相,很多人因为外貌被拒绝参与。这些都构成了后来女权运动和黑人女权主义崛起的大背景。

美国左翼运动中的种族问题

美国左翼运动种的种族问题是最近很多人聊到的话题,似乎BLM这类黑人运动更多关注种族,更少关注阶级的问题。前几天刚被清场的西雅图CHAZ占领区也出现了这个矛盾,白人抗议者想把更宏大的反新自由主义运动的议程嫁接进来,但一些黑人会觉得这些议题会妨碍BLM和黑人解放这个更紧迫的焦点,尽管TA们一般都承认新自由主义是个更本质的底色。这个争论其实一直存在,比如2018年末新共和发了一篇文章“Do American Socialists Have a Race Problem”,以美国目前最大的左翼激进组织美国社会民主主义DSA为例子,讲述了美国社会主义者内部对有色人种的排斥。这篇文章当时引发非常大的争议,因为左翼内部的白人很少承认自己有种族主义的问题。确实,种族和阶级在美国政治里面一直是非常缠绕,很多情况下甚至互斥的议题,这也是导致和很多发达民主国家相比,美国总体政治光谱相对保守的一个原因。

杜博依斯曾有一个著名的论断,“黑人问题是对美国社会主义者最大的考验。”他在自己的很多著作里都细致地刻画了劳工政治的种族主义倾向,白人劳工往往认为自己的劳权受损都是因为黑人的存在。Viewpoint杂志的Asad Haider在2018年出版的Mistaken Identity里,也总结到白人之间的族裔团结一直以来高于美国有色人种之间的阶级团结。

对黑人的种族主义一直以来都是其他移民融入美国的粘合剂,黑人是所有新移民共同的敌人,通过歧视黑人来融入主流白人社会的逻辑一百年来都没有变过。弗里德里克·道格拉斯曾经分析过爱尔兰移民对黑人的仇视,他说爱尔兰人在自己祖国愿意和全世界无产者站在一起,但一到美国就被教育要仇视黑人,才可以成为白人。在《美国黑人的重建》一书中,杜博依斯一开始就提到了美国从19世纪初欧洲移民涌入,到内战再到20世纪初一直并行的两类劳工运动:一是黑人劳工获取法律承认,后来也成为民权运动的由头,二就是白人移民劳工争取土地和更高的工资,后来就演化成了很多早年种族隔离的工会比如AFL。这两个运动偶尔会有一些联合,但是总得来说是互相冲突的。因为在不同时期,白人移民劳工,包括还有很多底层的白人都认为黑人压低了工资,抢了他们的工作。

现在关于欧洲移民怎么变成白人的著作已经非常多,最早有影响力的著作是1991年出版的The Wages of Whiteness,之后依据这个思路就有很多类似的文献。这些后来的文献,比如Working Toward Whiteness会更细致地描摹美国的欧洲移民除了心理上觉得自己总是比黑人高一等外,是如何一步步将自己美国白人化的,包括如何通过加入排斥黑人、墨西哥人和亚洲人的工会试图让自己和本地白人劳工平起平坐,通过购买房产来和买不起房的黑人的区隔开来。另一方面,美国的各种移民法律,比如1924年的移民法案限制了很多国家的移民进入,导致北部需要更多的黑人劳工来代替之前移民的工作。这也使得美国社会,特别很多商家开始比较黑人和移民劳工的优劣,从而觉得“有些移民比别的移民和黑人更平等“。

游天龙老师在之前的讲座提过由于在正规就业市场被歧视,亚裔经常被雇佣来当白人罢工的工会打手。其实当时黑人被雇佣是更普遍的现象,因为黑人男性除了和亚裔一样工资很低外,也一直被认为更强壮暴力,同时身体更能忍受痛苦。20世纪早年这些走投无路的工会打手都是由专业公司跨州雇佣,通过铁路统一运输的,所以雇佣的成本也进一步降低。另外,由于受到绝大部分工会的排斥,黑人劳工对白人工会存在怨恨,这也使得他们参与反罢工的时候带上了一些报复的心理。一个典型的例子是1919年席卷全美的钢铁行业大罢工中,绝大部分罢工打手都是黑人,而组织者一方AFL正巧拒绝黑人会员。所以最后这场罢工变成了资方雇佣的黑人和白人劳工的对战,非常有效瓦解了劳工的团结。这场罢工之后整个钢铁行业劳工运动一蹶不振,15年后才有新的罢工。

关于美国工会和种族主义的历史,还可以参考Mike Davis的经典作品Prisoners of the American Dream。他的核心观点之一就是历史上工会的种族主义让美国劳工运动一直都比其他欧陆国家保守和官僚主义,这是所有左翼思想家都没有预料到的。美国工会的官僚化具体包括疏于培训草根运动家,排斥其他左翼组织,不愿意纳入女性主导的文书职位和有色人种占多数的南方农业工种,不与民权运动合作等。

一个例外是1905年在芝加哥成立的IWW,世界产业工人联合会。IWW一直是跨种族、性别和国界做动员的,这也是受19世纪末20世纪初劳工无政府主义思潮的影响,认为全世界劳工不分职业应当隶属于同一个工会,所以它们的信条叫”One Big Union”。但这绝对不是劳工运动的主流,IWW哪怕在鼎盛时期也只有15万劳工会员,而同时期AFL旗下一个大行业分会,比如钢铁行业的人数都可以有30到40万。IWW的组织现在还有,在一些中大型城市集会和罢工中还可以看到他们组织的身影。但60年代开始,IWW开始直接介入民权运动,后来就更像一个社会运动组织而不是典型的工会。而且IWW是允许劳工隶属于别的工会的,所以其对旗下劳工的管理也更松散。华盛顿大学历史系做过一个IWW的数据库,里面有很多珍贵的史料和可视化,推荐给大家。

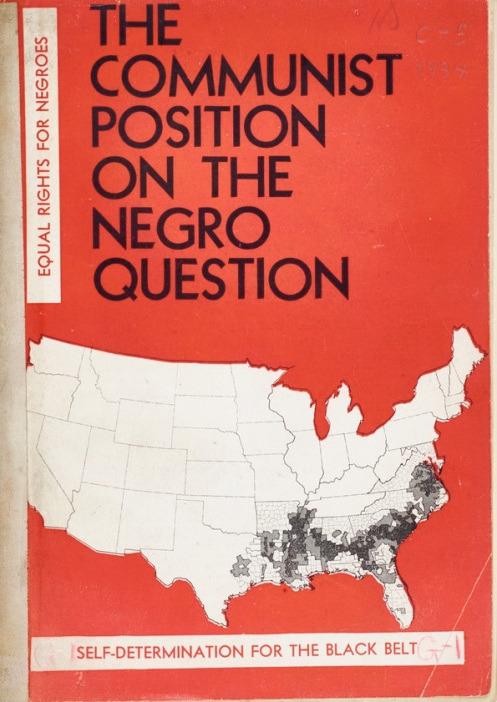

早期的美国共产党在族裔团结上构成了另一个特例。20世纪早期美国共产党曾经积极动员过黑人激进派。最明显的一个例子是1920年前后有个黑人秘密会社叫做African Blood Brotherhood,是当时一个记者和出版人Cyril Briggs创办的(这个人也是加勒比的移民),Claude McKay, 和Harry Haywood也是成员。这个组织内部有社会主义倾向的人后来和美共有很多合作,最终甚至直接成为了CP的一个分部。Harry Haywood是其中最著名的一位,他去苏联学习过,见过包括胡志明在内的很多人。根据美共三十年代初的组织宣传材料,可以看到TA们有鲜明的种族立场,支持南方黑人的自决,和RNA立场接近。但很遗憾的是,从30年代后期开始美共就已经逐步弱化对种族主义的讨论,当时也以散布黑人分离和民族主义为理由驱赶了很多黑人激进派。直到1959年CPUSA正式放弃了美国黑人民族自决的口号。他们觉得随着资本主义的发展和深化,黑人白人自动会团结起来。那个时候民权运动正是如火如荼的时候,美共不但没有有利介入黑人解放运动,白人负责人反而开除了Harry Haywood等一系列黑人成员。基本上从这个节点开始,美国的左翼激进主义运动,至少从组织成员来看形成了种族分化的格局,直到今天都是如此。

1930年代美共的黑人自决宣传材料,来源于:https://wolfsonianfiulibrary.wordpress.com/2018/01/15/civil-rights-and-the-cpusa/

美国主流的民权运动历史经常把70年代说的非常不堪,好像除了尼克松为首的保守派开始反击外社会抗争全面停滞,但这个完全不符合事实,其实70年代中期美国的劳工运动才达到顶峰,而这个高峰的到来和黑人解放运动密不可分。60年代以后,随着黑人权力运动的兴起,黑人激进派就开始自立门户。1968年底特律道奇工厂发育出来的劳工组织the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM)领导旗下工人罢工,是民权运动以后第一次彻底关停了工厂的罢工。由DRUM发展起来的the League of Revolutionary Black Workers是70年代最重要的黑人激进组织,卷入了几乎所有重要的罢工,也动员了很多白人劳工。但从组织层面,出于对白人的绝望,这些组织都只允许有色人种加入。The League也是最早提出并为reparations募集到款项的组织,动员白人宗教组织拿到了至少20万美金的捐款,所以不该预设所有白人都本能排斥黑人权力运动的理念。到80年代纽约还成立了The National Black United Front,到现在这个组织还比较活跃。90年代末Black Radical Congress在芝加哥成立,曾经聚集起了很多黑人运动家、泛非主义者和学者,包括Angela Davis,这些人也试图和其他族裔的激进派进行更密切的合作。所以其实60年代末民权运动消退以后,黑人运动还是得到了长足的发展。关键问题是当黑人发展自己的运动组织后,因为社运历史的记录者往往是白人,所以这些努力就不太容易被人看见。Michael Dawson在Blacks in and out of the Left里就很详细解释了黑人如何和白人左翼思潮渐行渐远,白人新左派也一直都不愿意承认黑人权力运动对族裔解放的作用,然后久而久之黑人激进派就被边缘化了。

那总结下,一系列原因共同导致了美国的种族和阶级撕裂了激进主义运动。首先欧陆马克思主义思潮的历史遗产导致很多左翼认为阶级斗争优先,种族只是阶级的反映。很多左翼组织内部也无人读杜博依斯、法农等黑人思想家的作品。从美共的历史也可以看到核心组织在分化中逐步远离黑人运动。再者,黑人激进派受到普遍的国家暴力,被迫转入地下。战后兴起的郊区化和居住隔离也很可能对左翼政治不利,因为左翼是非常依赖面对面社区动员的,但居住隔离导致左翼动员不到底层黑人,也难以建立跨族裔联盟。这些因素带来白人黑人互不信任的长期影响,不同族裔建立单独的激进左翼组织,这也导致黑人激进派愈发被孤立,在主流政治里处于边缘的地位。

所以如今至少从选票的层面,自由主义的思潮基本上主导了美国的黑人政治,奥巴马之年也一度巩固了很多人的幻觉,目前为止黑人对民主党的依附性还是很强。同时因为长期的打压,黑人激进派一直处于相对边缘和半地下的状态,一般没法像白人组织一样会公开招募成员,很多社区也没有登记为社会组织。但是另一方面,近些年BLM运动让黑人运动有重新激进化的可能性,参与运动的黑人运动家一般都不会在两党政治的框架下思考种族解放,核心运动家绝大部分都在其他左翼、劳工和LGBTQ组织任职。比如提出BLM口号的三位黑人女性Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi和Patrice Cullors都同时活跃在各类劳工和移民运动中,她们也在不同场合强调BLM是跨越国界的。

目前,美国当代左翼组织的事实性种族隔离还是非常严重。很多大众也已经有了左派都是白人的刻板印象,而不愿意多和他们来往。这里列举四个比较主要,立场又不太一样的白人左翼组织。说白人组织不是说这些组织就没有有色人种成员,而是非白人的比例非常低,组织内部有色人种成员也往往经历明显的歧视。The Democratic Socialists of America (DSA)是目前全美最大的左翼组织,有七万多付费会员。它曾经是相对保守的组织,是借着80年代很多更激进组织解体时候趁乱成立的。它的种族主义问题也很久了,80年代的时候DSA没有支持民主党激进派黑人候选人Jesse Jackson的总统竞选,史学家一般认为是组织内部种族主义导致。这两年随着组织内部有更多新的成员,有一些分部有了更多内部种族主义的反思。Socialist Alternative (SA)是一个托洛茨基主义的组织,它在美国的知名度基本是靠当选西雅图市议员的Kshama Sawant提升的,目前Sawant还在市议会任职,也积极支持参与了当地的占领运动。Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL)基本是个白人斯大林主义组织,经常持比较教条的立场,但他们对拉美政治的关注可能是所有组织里最强的。Redneck Revolt (RR)是个很有意思的左翼拥枪组织。所以这也有助于打破白人拥枪的都是红州保守主义者的刻板印象。

当前以黑人为主的左翼组织内部意识形态也很多元。Black Socialists in America (BSA)是2018年才成立的黑人社会主义组织,很大程度是为了回应DSA的种族问题,当然相比DSA,BSA的公开活动要少很多,成员都是匿名出镜。Revolutionary Abolitionist Movement (RAM)是无政府主义的社区,它们也有仿照黑豹党的十点纲领,包括废除警察军队和监狱。所以现在Defund the Police运动中确实是有希望彻底废除警察的一派的,也没必要否认和切割。Cooperation Jackson是一个2014年密西西比杰克逊成立的合作社网络。Huey P Newton Gun Club顾名思义是以黑豹党前领导人的名字命名的拥枪组织。总的来说在美国的左翼政治版图里,黑人左翼会更偏无政府主义一些。因为一来在践行民主集中制的混合族裔组织里,黑人肯定是被压迫的;二来无政府主义组织更去中心化,可以更有效地规避国家的监视和镇压。

黑人解放运动与BLM2020

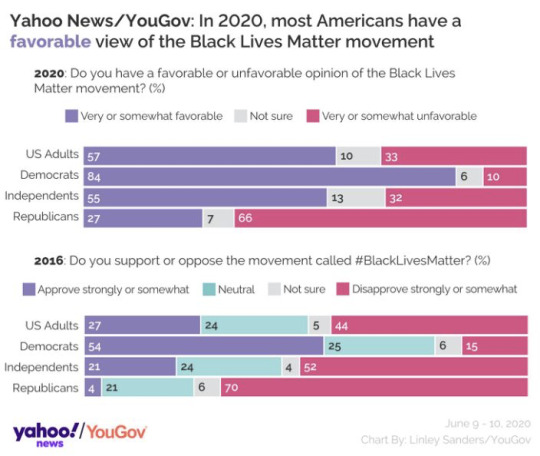

最后谈一下对目前BLM的一些观察,以及和之前提到的黑人运动历史之间的关系。进行了一个多月的BLM虽然由反警察暴力开始,但发展到现在已经有了更多的议题。虽然在中文网络上可能还是有很多反对的声音,但在美国本土,BLM从成立以来第一次有了大部分人口的支持。

从民意调查上来看,BLM口号在2012年奥巴马任下刚提出来的时候是完全没有群众基础的,这和历史上所有黑人运动,甚至社会运动的命运都是一样的。公众对社会运动的高支持度,往往是参与者不断动员、说服、制造领导权的结果。对比2016年和今年的数据,可以看到2016年的时候,YouGov调研的美国被访者只有27%明确支持运动,这个比例到今年翻了一倍不止。当然这里有个问题是今年没有中立这个选项了,所以很多人态度可能向支持方向位移,但明确反对运动的人也减少了不少。然后很有意思的是中间派独立选民的意见变化幅度是最大的,也就是说其实运动动员起来了大部分中间选民,但基本没有让共和党选民改变看法。

党派与BLM支持,来源于:https://news.yahoo.com/new-yahoo-news-you-gov-poll-support-for-black-lives-matter-doubles-as-most-americans-reject-trumps-protest-response-144241692.html

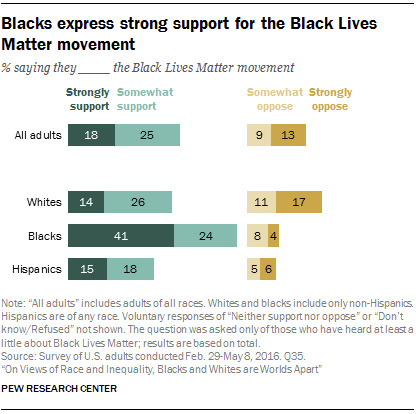

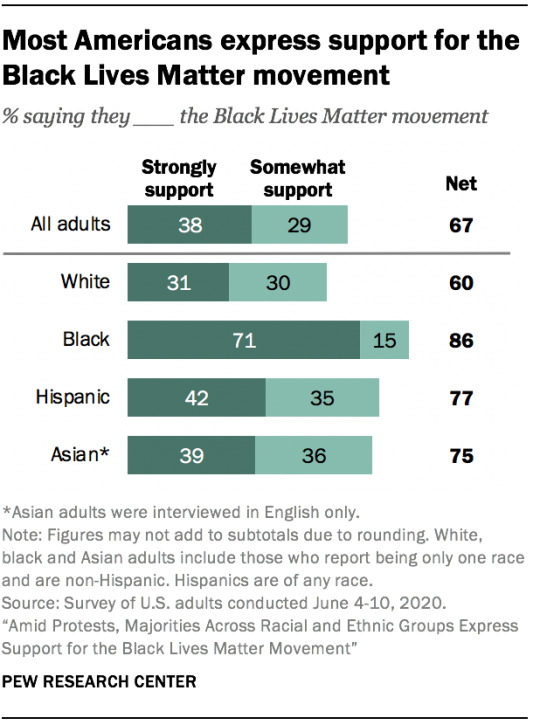

从皮尤归纳的分族裔的支持度来看,除了各族裔总体更支持BLM外,拉丁裔的观念变化是最剧烈的,直接从2016年的比白人更不支持到目前77%的高支持度。我希望会有更多的研究出来论证具体的机制,但个人总体感觉是这次全国范围的BLM通过把黑人的处境置于其他少数族裔和移民面前,从而极大促进了少数族裔之间的自我教育和团结。这里没有亚裔的对比数据,但之前有个单独的调查发现抗议下亚裔对警察的观感下降是最明显的。最近针对亚裔为何不支持黑人运动有很多辩论,我想说其实对拉丁裔来说,除了无证移民,很多人同样很难共情黑人的处境。这次抗议期间拉丁裔内部,特别是白人拉丁裔同样有反省自身的anti-Blackness,甚至也有如何和父母和老一辈有效对话这种讨论。所以其实亚裔也可以通过和拉丁裔的连结,来互相指认和创造性地面对社群内部种族主义的问题。

2016年BLM分族裔支持度,来源于:https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/07/08/how-americans-view-the-black-lives-matter-movement/

2020年BLM分族裔支持度,来源于:https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/06/12/amid-protests-majorities-across-racial-and-ethnic-groups-express-support-for-the-black-lives-matter-movement/

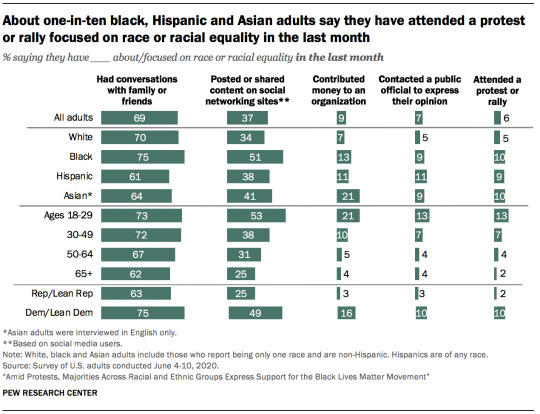

最后这张图表是皮尤同一个调查里不同人口变量与政治参与行为的交互,可以看到拉丁裔、亚裔的参与比例和黑人十分接近。甚至在给组织捐款上,亚裔的比例要远远超过其他族裔。按照右图给出的过去一个月的抗议参与比例,也是只有白人在拖后腿,且亚裔的参与度是所有族裔中最高的。我们觉得亚裔参与度低还是因为亚裔总人数真的太少了,很难在抗议中彼此看见。当然这类调查经常只访问会说英语的亚裔,所以实际比例会低一些,但至少说明年轻一代的政治参与热情是非常高的。

Pew不同人口变量与BLM政治参与行为的交互,来源于:https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/06/12/amid-protests-majorities-across-racial-and-ethnic-groups-express-support-for-the-black-lives-matter-movement/psdt_06-12-20_protests-00-10/

BLM运动���种族的高支持度伴随的是其去中心化的特征。在我看来去中心化具体是和三个子特征结合起来的,商业化、城市社区化和大规模监控。但凡社会运动发展到一定程度,多多少少会有一些商业化的色彩,或者说更多企业看到民意愿意去支持BLM的诉求。早期可能是耐克这样的运动企业会支持,因为顾客里就有很多黑人,但现在亚马逊、Spotify、Netflix这类互联网公司也加入了挺BLM的阵线。讽刺的是,亚马逊恰恰是造成黑人持续贫困和被压迫的根本原因。它造成的士绅化,对旗下服务业劳工的压榨、Covid19下对仓储和WholeFoods罢工的镇压都很能说明它支持BLM的虚伪性。亚马逊2018年的时候还被爆出将旗下一个面部识别软件Rekognition卖给警方。在这样的背景下,BLM运动内部肯定会有策略性支持商业公司的,也有反对被资本主义收编的激进派。这种运动内部的立场如何在一个去中心的结构下做协调配合,而不是拉锯内耗,对未来的运动是一个挑战。

这次各地上街的人数很多,口号也很齐整统一,但每个地方的运动势能和诉求差异其实很大。因为像Defund the Police这种诉求落实肯定是要运动参与者和当地的市长、市议会、警察部门斗争和斡旋。警局的预算一般都是市议会批准的,比如不久前白思豪批准市议会砍掉了NYPD下一个财年7%的预算。还有拆种族主义雕像和壁画的话各地的情况也非常不同,还有一些历史雕像可能在其他少数族裔社区和大学,还需要抗议者和社区负责人、各类社会机构进行协调。

另一个去中心的因素,则在于不同城市社会运动的历史遗产不同,我这里举西雅图和我居住的费城的例子。这次西雅图抗议最特殊的地方就是CHAZ/CHOP占领区。这个区域几天前已经被清空了,但还是留下不少宝贵的运动经验和教训。之所以西雅图可以成功实现占领而非简单的游行,和本地有几十年历史的占领文化和无政府主义社区的兴盛是很有关系的。最晚从70年代开始原住民和拉丁裔社群就组织过不少占领荒地和学校的行动。CHOP占领区有各个不同社运组织的力量,除了BLM的人外也有大量当年参与Occupy的社群,还有一些这次疫情下涌现出的互助组织。因为Occupy的白人占大多数,所以运动内部一直都有种族和运动路线的矛盾,比如自治和占领的议程是否会干扰更紧迫的警察改革,这些争议直到占领结束也没有缓解。但总的来说,西雅图之前各个族裔联合抗争的历史对这次的运动有非常大的帮助。

相比之下费城的政治生态就非常不同。这里有非常强的黑人权力运动的历史,美国第一个黑人权力运动组织RAM当年总部就是在费城,其他黑人权力组织在费城也都有分部,当然还有MOVE。今次BLM运动里,西费城的行动者纪念MOVE爆炸三十五周年还特别制作了短片,可以看到现在费城的社运还是受到当年历史很强的影响,诉求要比其他地方激进很多,比如这里的运动家是反对"Hands up, don't shoot”这种自我矮化的口号。虽然很多这类抗议吸引不了全国媒体的关注,但是对本地政治是有很大影响的。

最后一个挑战就是如何应对大规模监控。美国的黑人运动受到的国家监控是最严密的。这次各地的BLM示威,各城市和州警察、国民警卫队、FBI和军方都派出了无人侦察机和巡逻机,监控达到了军事级别。仅仅国土安全部和海关执法局就直播和录制了至少270小时的抗议人群画面,这还不包括其他地方部门的档案。面对这种监控,我认为美国运动者做得还是很不够,很多消息发布和沟通都靠公开的脸书、推特和Instagram,反而是Boogaloo等右翼运动更多用加密软件。目前电报上最大的BLM频道只有不到一万关注者,完全不成体系,这可能对未来的运动协调造成伤害。

谢谢大家。

参考读物:

Bothmer, Bernard von. 2010. Framing the Sixties: The Use and Abuse of a Decade from Ronald Reagan to George W. Bush. First edition edition. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Brown, Elaine. 1993. A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story. 1st Anchor Books ed edition. New York, NY: Anchor.

Davenport, Christian. 2014. How Social Movements Die: Repression and Demobilization of the Republic of New Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Davis, Angela Y. 2016. Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement. 4TH PRINTING edition. edited by F. Barat. Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books.

Davis, Mike. 1999. Prisoners of the American Dream: Politics and Economy in the History of the US Working Class. Verso.

Dawson, Michael C. 2013. Blacks In and Out of the Left. Harvard University Press.

Du Bois, W. E. Burghardt. 1998. Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880. 12.2.1997 edition. New York, NY: Free Press.

Elbaum, Max. 2018. Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals Turn to Lenin, Mao and Che. New edition. London: Verso.

Haider, Asad. 2018. Mistaken Identity: Race and Class in the Age of Trump. London ; Brooklyn, NY: Verso.

Hoerl, Kristen. 2018. The Bad Sixties: Hollywood Memories of the Counterculture, Antiwar, and Black Power Movements. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

James, C. L. R. 1989. The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. 2 edition. New York: Vintage.

James, Winston. 1998. Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia: Caribbean Radicalism in Early Twentieth Century America. London ; New York: Verso.

Léger, Marc James, and David Tomas, eds. 2017. Zapantera Negra: An Artistic Encounter Between Black Panthers and Zapatistas. Brooklyn, New York: Common Notions.

Leonard, Aaron J., and Conor A. Gallagher. 2018. A Threat of the First Magnitude: FBI Counterintelligence & Infiltration From the Communist Party to the Revolutionary Union - 1962-1974. London: Repeater.

McAdam, Doug. 1990. Freedom Summer. 1 edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mokhtefi, Elaine. 2018. Algiers, Third World Capital: Freedom Fighters, Revolutionaries, Black Panthers. Verso.

Robnett, Belinda. 1997. How Long? How Long?: African American Women in the Struggle for Civil Rights. 1 edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Roediger, David R. 2005. Working Toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White: The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs. New York: Basic Books.

Spencer, Robyn C. 2016. The Revolution Has Come: Black Power, Gender, and the Black Panther Party in Oakland. Durham: Duke University Press Books.

Stevens, Margaret. 2017. Red International and Black Caribbean: Communists in New York City, Mexico and the West Indies, 1919-1939. London: Pluto Press.

Theoharis, Jeanne. 2018. A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History. Boston: Beacon Press.

Ture, Kwame, and Charles V. Hamilton. 1992. Black Power : The Politics of Liberation. New York: Vintage.

Wallace, Michele. 2015. Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman. Reprint edition. London: Verso.

Whatley, Warren C. 1993. “African-American Strikebreaking from the Civil War to the New Deal.” Social Science History 17(4):525–58.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dave Molter Gives us some Blues to Groove with on (Really Nothin' New) Under the Sun

Artist: Dave Molter

New Release: (Really Nothin' New) Under the Sun

Genre: Rock; blues rock

Sounds like: I'm all over the place: Beatles, Joe Walsh, Delbert McClinton, Peter Gabriel

Located in: Pittsburgh, PA

One of my friends called this tune "swampy," and I have to agree. It's a medium blues groove that is familiar but with a bit of a surprise on the turnaround. Great slide guitar from Dave Flodine adds to the mood. The title gives you the subject matter: "(Really Nothin' New) Under the Sun." And haven't we all felt like that?

You wake up with energy and — before the day’s over you are confronted with the same old problems.

“Under the Sun” sounds different from the songs on my debut EP, "Foolish Heart." It's stripped-down -- just guitar, piano, bass, drums, no harmony on the lead vocals. By contrast, most of the songs on my EP have multiple overdubs and sound more "produced."

The difference in "Under the Sun" and many of the songs that will appear on my next EPs is that I changed studios and producers. Al Snyder is at the helm this time, and his approach -- with which I agree -- is that lyrics are paramount. The feel of the song is important, too, and likes to leave space in the production and instrumentation so that the listeners don't have to struggle to hear what's being sung. I think listeners will find that the approach works.

That doesn't mean we won't have songs with heavier production on the next EPs, but there will be a lot with minimal instrumentation.

It's no secret that The Beatles are my main influence, but I've been playing for more than 50 years.

Most of that time was spent in cover bands, and when you play Top 40, you become aware that there are a lot of valid styles out there. This tune is influenced by blues, but I still have songs in the pipeline that reflect the British music hall era, Sixties pop-rock, and a few more. As for the message in "Under the Sun," it's simple: Life’s work in progress. Don’t give up. Same problems? Keep on pushin’! I know that in my life, I've been tempted to give up. But I didn't; I just reinvented myself. Many times, actually!

Being that I have just switched producers and studios, we plan to have a new EP with 5 or 6 songs out before Christmas 2020.

Most will be new songs, but some will be ones we had in the can from my previous sessions with Buddy Hall.

In 2021, We’ll put out more EPs. I think EPs are the way to go, along with singles. No one seems in the mood to listen to a full CD anymore.

As for shows, with COVID-19 it's hard to tell what 2021 will bring.

We've talked about putting together a band with friends who also write and doing shows with tunes from each of us. I doubt a tour is possible these days. What we hope to do is have ticketed shows in small venues -- clubs or theaters -- that will allow us to observe social distancing rules (if they are still in effect). No matter what we do, the business will be different than what we envisioned a year ago.

About the Artist…

Dave Molter began his music career in 1965, one year after seeing The Beatles on "The Ed Sullivan Show." In the early days, Dave's bands had 45 RPM records out, but most of his career was spent in clubs or opening for big-name acts such as The Allman Brothers, Deep Purple, The Rascals, The Impressions, and many more. After a hiatus from performing, Dave released his debut EP, "Foolish Heart," in 2020.

Since its release, four of the five tunes on it have hit #1 on indie radio worldwide, and his sixth single, "Oh Woman, Don't You Cry," also hit #1. "He was a finalist in four categories for the 2020 Josie Awards and the 2020 International Singer-Songwriter Awards, and "Foolish Heart" or songs from it appeared on several "Best of 2019" year-end lists. His songs continue to be in rotation on indie radios around the world, including Africa, Australia, Japan, Mexico, Germany, Sweden, the U.K, the U.S., And many more.

LINKS:

Reverbnation: https://www.reverbnation.com/davemolter/song/32142049-really-nothinnew-under-the-sun

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/album/19aI1baPBG3U75ImRV130h?si=57VVL-zsSmqSB6QozxZ8Mg

Twitter: @molter_dave

Facebook: www.facebook.com/Davemoltermusic

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/dave_molter_music

1 note

·

View note

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

By Stephen Millies

Two hundred people marched in Philadelphia on Aug. 8 to protest police terror and honor the memory of Delbert Africa. It was the 42nd anniversary of the police assault on the MOVE house in the city’s Powelton Village neighborhood.

#Delbert Africa#MOVE#political prisoners#police brutality#Philadelphia#protest#memorial#MOVE9#Black liberation#Struggle La Lucha

4 notes

·

View notes