#vue tutorial hello world

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

VueFire: CRUD Application with Vue.js and Firebase VueFire: CRUD Application with Vue.js and Firebase Want to learn how to integrate Firebase and Vuefire into your Vue.js applications? This video does just that ... source

#application#crud#firebase#vue crud#vue crud firebase#vue fire#vue firebase crud#vue firebase example#vue firebase tutorial#vue tutorial hello world#vue.js firebase#vue.js vuefire#vuefire#vuefire tutorial#vuefire vuejs#VueFire: CRUD Application with Vue.js and Firebase#vuejs#vuejs firebase#vuejs firebase tutorial

0 notes

Text

Blazor WebAssembly on Azure Static Web Apps

Many apps today are just static files on the front end - HTML and JavaScript - with something powerful on the server side. They aren't "static apps" as they have very dynamic front end experiences, but they are static in that their HTML isn't dynamically generated.

As such, you don't need to spend the money on an Azure Web App when an Azure Static Web App will do! These apps get free SSL certs, custom domains, web hosting for static content, and fit into a natural git-based workflow for publishing. You can build modern web applications with JavaScript frameworks and libraries like Angular, React, Svelte, Vue, or using Blazor to create WebAssembly applications, with an Azure Functions back-end or publish static sites with frameworks like Gatsby, Hugo, VuePress.

But there's big news out of Ignite this week, with Azure Static Web Apps now supporting Blazor applications. You can develop and deploy a frontend and a serverless API written entirely in .NET.

To get started "hello world style" there is a GitHub repository template that's a starting point. It's a basic web app with a client that uses Blazor and .NET that is run on the client-side in your browser using WebAssembly.

Called it! It's almost a decade later and yes, JavaScript (and WebAssembly) is the assembly language for the web!

So the client runs in the browser written in C#, the server runs as a serverless Azure Function (meaning no identifiable VM, and it just scales as needed) also written in C#, and this client and server share a data model between Blazor and Functions also written in...wait for it...C#.

An app like this can basically scale forever, cheaply. It can put the browser to work (which was basically hanging out waiting for anglebrackets anyway) and when it needs data, it can call back to Functions, or even Azure CosmosDB.

Be sure to check out this complete Tutorial: Building a static web app with Blazor in Azure Static Web Apps! All you need is a GitHub account and any free Azure Account.

If you want more guided learning, check out the 12 unit module on Microsoft Learn. It shouldn't take more than an hour and you'll learn how to Publish a Blazor WebAssembly app and .NET API with Azure Static Web Apps.

Resources

Guided Tutorial - Publish a Blazor WebAssembly app and .NET API with Azure Static Web Apps

Quickstart: Building your first static web app

Blog: ASP.NET Blog post announcement - Blazor and Static Web Apps

How To: Chris Noring's How to deploy Blazor apps

What are Azure Static Web Apps?

Also be sure to check out the Day 2 Microsoft Ignite Keynote by yours truly! The app I made and demo in the keynote? Made with Blazor and Azure Static Web Apps, natch! The keynote is happening in three time zones so you can see it at a time that works for you...or on-demand!

Sponsor: Upgrade from file systems and SQLite to Actian Zen Edge Data Management. Higher Performance, Scalable, Secure, Embeddable in most any programming language, OS, on 64-bit ARM/Intel Platform.

© 2020 Scott Hanselman. All rights reserved.

Blazor WebAssembly on Azure Static Web Apps published first on https://deskbysnafu.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Blazor WebAssembly on Azure Static Web Apps

Many apps today are just static files on the front end - HTML and JavaScript - with something powerful on the server side. They aren't "static apps" as they have very dynamic front end experiences, but they are static in that their HTML isn't dynamically generated.

As such, you don't need to spend the money on an Azure Web App when an Azure Static Web App will do! These apps get free SSL certs, custom domains, web hosting for static content, and fit into a natural git-based workflow for publishing. You can build modern web applications with JavaScript frameworks and libraries like Angular, React, Svelte, Vue, or using Blazor to create WebAssembly applications, with an Azure Functions back-end or publish static sites with frameworks like Gatsby, Hugo, VuePress.

But there's big news out of Ignite this week, with Azure Static Web Apps now supporting Blazor applications. You can develop and deploy a frontend and a serverless API written entirely in .NET.

To get started "hello world style" there is a GitHub repository template that's a starting point. It's a basic web app with a client that uses Blazor and .NET that is run on the client-side in your browser using WebAssembly.

Called it! It's almost a decade later and yes, JavaScript (and WebAssembly) is the assembly language for the web!

So the client runs in the browser written in C#, the server runs as a serverless Azure Function (meaning no identifiable VM, and it just scales as needed) also written in C#, and this client and server share a data model between Blazor and Functions also written in...wait for it...C#.

An app like this can basically scale forever, cheaply. It can put the browser to work (which was basically hanging out waiting for anglebrackets anyway) and when it needs data, it can call back to Functions, or even Azure CosmosDB.

Be sure to check out this complete Tutorial: Building a static web app with Blazor in Azure Static Web Apps! All you need is a GitHub account and any free Azure Account.

If you want more guided learning, check out the 12 unit module on Microsoft Learn. It shouldn't take more than an hour and you'll learn how to Publish a Blazor WebAssembly app and .NET API with Azure Static Web Apps.

Resources

Guided Tutorial - Publish a Blazor WebAssembly app and .NET API with Azure Static Web Apps

Quickstart: Building your first static web app

Blog: ASP.NET Blog post announcement - Blazor and Static Web Apps

How To: Chris Noring's How to deploy Blazor apps

What are Azure Static Web Apps?

Also be sure to check out the Day 2 Microsoft Ignite Keynote by yours truly! The app I made and demo in the keynote? Made with Blazor and Azure Static Web Apps, natch! The keynote is happening in three time zones so you can see it at a time that works for you...or on-demand!

Sponsor: Upgrade from file systems and SQLite to Actian Zen Edge Data Management. Higher Performance, Scalable, Secure, Embeddable in most any programming language, OS, on 64-bit ARM/Intel Platform.

© 2020 Scott Hanselman. All rights reserved.

Blazor WebAssembly on Azure Static Web Apps published first on http://7elementswd.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

VueJS & Firebase Cloud Firestore Stripped-Back - Tutorial Part 1

In this tutorial series we will explain how to start developing with the Vuejs framework & Firebase Cloud Firestore to build full-stack web applications. We’ll start from scratch by stripping everything back to the basics - no CLIs, build tools or bundlers, just a HTML page, an editor and a browser so you can get to grips with building apps with Vue & Firebase more quickly and be productive faster.

VueJS

Vuejs is now one of the big 3 Javascript frameworks in the web client ecosystem. However it’s not developed or backed by a huge corporation, it was developed by one individual, Evan You. The proliferation of JS frameworks in recent years has led to the term “Javascript Fatigue” where developers have become weary of all of the new and self-proclaimed “latest and greatest” open source frameworks. It is in this environment that Vue has emerged through all of the noise to become a major player alongside Angular and React (both backed by huge technology companies, Google and Facebook respectively). That Vue has achieved such a status in this environment backed by one individual highlights just how Vue has hit a chord with developers and is filling a gap that isn’t being met by Angular, React or other competitors like Ember and Aurelia.

Evan You is an ex-Googler who was familiar with AngularJS (often referred to as Angular 1) and used it for internal projects at Google that he was working on. He set out to achieve a framework that delivered the benefits of AngularJS but was more lightweight, faster and better suited to smaller apps that didn’t require the heavy-lifting of the huge apps that AngularJS was originally built to develop such as their Adwords platform and their internal CRM system. What he produced was a beautifully simple solution and it quickly attracted adoption as the front-end framework of choice for many PHP developers, particularly from the Laravel community.

Despite promising early adoption in some quarters, Vue may well have stayed a “me-too” framework in the ecosystem had it not been for Google’s decision to redevelop their AngularJS framework from scratch. Angular (often referred to as Angular 2) was such a departure from the original AngularJS framework that it introduced a fundamental shift in approach and required developers to learn many new concepts just to build basic apps. Developers were kept in limbo between AngularJS and Angular for almost 2 years, with many alphas and then betas and many breaking changes and missing pieces to deal with during the transition and then no easy migration path for their existing code and apps.

There’s no doubt that, as a new framework in it’s own right, Angular is a fantastic, powerful, all-in-one next generation framework but it isn’t “Angular” as millions of developers know it. Perhaps the biggest mistake Google made was in not launching their next-gen framework under new branding. In any event and unfortunately for Google, Angular 2 was too big a change for many developers and while uptake was initially high, it hasn’t achieved the type of ongoing adoption or love as AngularJS or React and it’s clear that Vue, with many obvious similarities to the original Angular, has arrived just in time to sweep up and become a magnet for disgruntled Angular devs.

In addition, the droves of developers jumping in to the Javascript ecosystem over the past years, in their evaluation of an appropriate framework, are choosing Vue in vast numbers due to how easy it is to learn and how quickly they can start building apps. I would say that the best word to describe Vue to developers choosing a framework is “approachable” - it seductively invites you in and once there you find it’s so intuitive and simple to get productive, covering all of the bases you need, that once you’re in you tend to stick with it. For me personally I actually enjoy spending my days developing around Vue, I cannot say the same for Angular unfortunately.

In 2018, Vue is set to gain even greater momentum and overtake Angular into second place in the Javascript framework popularity chart. The main reason for this may be that the massively popular Ionic mobile and PWA framework is about to release a version that decouples it from Angular and enables developers to build apps with Ionic using any framework (or none at all). It’s interesting that this is likely to be a tipping point for Vue to achieve critical mass and yet is due to the Ionic team’s concern that Angular isn’t seeing the level of adoption anticipated and continuing to hitch their wagon to Angular is likely to hamper their own growth.

To address this, in Ionic 4, they’ve developed a framework-agnostic, web component-based edition of their mobile framework. When you look online it’s fairly clear that the majority of the delight at Ionic’s shift away from Angular is coming from those who want to use Ionic with Vue. Personally I only stuck with Angular because of Ionic despite my preference for Vue and since their announcement of Ionic 4, I have thrown myself fully into Vue. The sweet spot that Vue hits between Angular and React is in delivering a more lightweight and simple approach than Angular, focussing first and foremost on being a view renderer like React but providing optional elements that are officially supported and developed by the Vue core team, such as routing that can be easily dropped in to your app. This is what is meant when Vue is called a “progressive framework”, you can start by using as little or as much of the framework as you need, progressively using more of it’s subsidiary elements as required. Another advantage to using Vue is that it’s lightweight enough to use it in one part of your app and progressively expand it to other parts when you’re ready, for example if you have existing app in vanilla Javascript, jQuery or another framework that you want to change over to Vue piece by piece.

As mentioned, Vue’s biggest advantage is it’s simplicity and approachability. While other frameworks require knowledge of build systems, CLIs, Node, NPM etc just to start building an “Hello World” app, with Vue you can strip everything right back, open up an HTML file in an editor and get started simply without needing to spend time learning anything else. While you’ll likely want to move over to the full modern JS development environment as you get more involved, it isn’t required to get started.

Firebase Cloud Firestore

So Vue is a fantastic front-end framework but to build even the most trivial worthwhile app, we need a back-end and a data store. Like with using Vue, we want to use something that delivers simplicity and approachability yet gives us the power to build advanced apps as you become more experienced. For this project Firebase Cloud Firestore is a no-brainer to use as the database back-end. Like Vue, we can just get started using Firebase with just a basic HTML page - no need for CLIs and build tools to just start building something.

I first used Firebase back in 2014, when they were a small, private company shortly before they were acquired by Google. At the time Firebase was not a platform but a hosted realtime database and I fell in love with it immediately - for prototyping it was perfect and it’s realtime capabilities were just awe-inspiring at the time.

However Firebase did have some serious limitations that made it unsuitable for me to use as the back-end database in a production app. It didn’t allow server-side code, so all of your logic was exposed on the client and it’s database querying facilities were extremely limited. Also, as a No-SQL document database, organising relational-style data into something that was manageable without joins and queries required denormalisation and duplication of data, something which is anathema to those coming from a SQL-based relational database background. I felt it was a real shame as, despite these limitations, it was very impressive and working with it’s Javascript API was a joy.

After Google’s acquisition, Firebase was expanded into a full serverless platform allowing for storage, cloud messaging, hosting, authentication, analytics and much much more. What had been “Firebase” became the Realtime Database element of the platform. Fortunately Google started to address the limitations that I and many other developers had found with the original Firebase. First server-side code, in the form of Cloud Functions, was added which enables you to put more of your sensitive business logic code onto the server.

More recently Google introduced an alternative database to the original realtime database which they call Cloud Firestore. Cloud Firestore addresses many, but not all, of the issues with the realtime database in terms of querying and organisation of data. It still provides the full realtime capabilities that we know and love and is still a No-SQL database based on documents. However you can now organise them into Collections (similar to relational DB Tables) which enables you to perform much more advanced queries. You can have specifically defined fields each of which can have a specific type. One of these types is the Reference type which lets you store links between documents on different collections to enable a form of join. In addition Cloud Firebase enables offline usage so the user can continue to use your app even if access to the server isn’t available. There are still limitations, remembering it’s not a relational database, and full joins are not possible and neither are aggregate queries such as SUM, COUNT etc. However with 90% of the issues I had with the original Firebase realtime database now dealt with through Cloud Functions and Cloud Firestore, Firebase is now an excellent choice as the back-end, serverless platform and data store for building full-scale production apps.

OK so enough talk about the what and why, let’s get going with the how and write some code. We’re going to start, as we’ve talked about, with a single HTML page. Choose your OS, code editor and browser of choice (I’m using VSCode on OSX and highly recommend using Chrome as your browser).

Open up your editor and select to create a new file in a new folder. Just call the new file index.html. Once you’ve done this, start with a skeleton html page as shown below :

<html>

<head> <title>VueJS & Firebase From Scratch</title> </head>

<body>

</body>

<script>

</script>

<html>

The first thing we’ll need to do is to import the VueJS library. We can do this with a CDN link (see below) which is placed below the closing body tag and before the opening script tag :

<script src="https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/npm/vue"></script>

This recommended CDN link is correct at the time of writing however may change in future. To ensure it’s correct, once you’ve inserted this link into your page, save it and open it up in Google’s Chrome browser (select File from Chrome’s menu and select Open File … to navigate and select your newly created index.html file). The page will show as blank in any case however right-click on the page and select Inspect from the pop-up menu and click the Console tab. If this displays nothing eg there are no error messages then you’re good however if you do get an error complaining about the vue library then browse to https://vuejs.org/v2/guide/ and look for the link displayed under Getting Started.

We’re ready to build our app! The first thing we need to do is to create the Vue Instance Object that will be used as the core of your app.

<script> var app = new Vue({ el : '#app' }) </script>

This creates a new Vue instance that we can reference throughout our html template and which contains all of the data and methods that we’ll create to develop the app. Some call it the View Model however we’ll stick to calling it the Instance Object. We simply create a new object called app from Vue and pass in an object with all of the information about our app. To begin with, we only declare a single property in this object which is el, short for element, and we assign #app. This tells Vue that any reference to an element that has the id of app is to be controlled by our Vue Instance Object.

In our html template we can now simply create a container html tag and assign it the id of app. All of the content within that tag is then controlled automatically by our Vue instance object. (Please note that any content in bold from here on in denotes new or changed content.)

<body>

<div id=‘app’>

</div>

</body>

Please note : Unlike AngularJS, with Vue you cannot assign the reference to the Instance Object on the body tag, you have to create your own container tag to assign it to, as in this case we’re assigning it to a div container.

Great but we’re not actually doing anything yet. Now we want to give our app some life. To do this we’ll give the app a name and display it as a title and we’ll do this as data held on the Instance object rather than write it directly on the template. To do this we’ll need to add another property called data to our instance object. The data property is an object which contains any variables you want to reference in your template or elsewhere in your app. In this case we’ll create a variable called appTitle and assign it a name. The app we’re going to build is an employee tracker that is going to be so indispensable to it’s users that it will be like magic!

<script> var app = new Vue({ el : '#app’, data : { appTitle : ‘EmployeeMagic’ } }) </script>

We can now use the data binding features of Vue to display our new app title in our page template.

<body>

<div id=“app”>

<h1>{{ appTitle }}</h1>

</div>

</body>

Save and refresh your page in Chrome and you’ll see EmployeeMagic as your app header. The double curly braces are pretty standard in most frameworks these days to denote data-binding (also called interpolation). The content inside the double-curlies is interpreted by Vue and the required content is displayed at that point in the template. In this case Vue recognises that we have a variable called appTitle in data in our Instance Object and replaces it in our template with the value contained in the variable. There are many benefits of data-binding, the main one being that any change in the variable in our instance object is automatically reflected in our template without any additional effort on our part.

So far so good but it’s a little plain-Jane so let’s add the Bootstrap library link for a bit more aesthetic to it without any extra effort. The link used below for then Bootstrap CDN was current at the time of writing however check the Bootstrap website if you have trouble with the link :

<header> <title>EmployeeMagic</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://maxcdn.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/4.0.0-beta.3/css/bootstrap.min.css"/>

</header>

Let’s say however we want to add a margin around the app so it’s not displaying right up against the edge all the time. To do this we’ll need to add some CSS styling however we can take advantage of a cool Vue feature which lets us set our styles programatically.

Let’s add another variable to our data object which is specifically for styles, let’s call it mainStyle. This will be an object so that we can assign as many different CSS style settings as we like. For now we just want to assign a margin of 20 pixels :

<script> var app = new Vue({ el : ‘#app’, data : { appTitle : ‘EmployeeMagic’, mainStyle : { ‘margin’ : ‘20px’ } } }) </script>

Now we need to tell Vue where to use that styling property in our template. We’ll create a new container div tag to wrap around the rest of our app. In that tag we need to tell Vue to assign the styling we’ve defined in mainStyle. To do this we can use a Vue directive called v-bind:style and assign it the name of style object we want to use.

<body>

<div id=“app”>

<div v-bind:style=“mainStyle”>

<h1>{{ appTitle }}</h1>

</div>

</div>

</body>

Save and refresh in Chrome and you’ll see the margin has been applied. I personally love this feature of Vue and there are lots more you can do to apply styling which we’ll cover later in the tutorial.

It’s interesting to note that when using directives such as v-bind:style, Vue offers a more shorthand way by dropping the v-bind. If Vue just sees :style it knows what to do, so we could have used ...

<div :style=“mainStyle”>

... instead. Throughout these tutorials I’ll continue to use the more verbose version to show the full directives consistently however where a new directive is shown, I’ll also highlight the shorthand version. Generally if you see v-bind followed by a colon and the command, you can drop the v-bind although there are exceptions that we’ll cover in a future part of the tutorial.

We’ve so far covered what VueJS and Firebase Cloud Firestore are, why we’re using them as the framework and platform for this app, and the basics of setting up a simple HTML page to build our employee tracker app, setting up our Vue object, basic data-binding and styling using a Vue directive.

In the next 4 parts of this tutorial we’ll focus on each element of CRUD (Create, Read or Retrieve, Update and Delete) so in part 2 we’ll deal with Creating records to store in our Firebase Cloud Firestore.

Hope you can join me in Part 2 :)

You can download the completed code for this part of the tutorial on Github using the repo below and select the part1 folder. https://github.com/MancDev/VueFire

1 note

·

View note

Photo

How to Build a Tic Tac Toe Game with Svelte

Svelte is a next generation way of building user interfaces.

While frameworks like React, Vue and Angular do the bulk of their work in the browser, Svelte takes it to the next level. It does its work when you build the app and it compiles your Svelte app to efficient vanilla JavaScript. So you get the best of both worlds. You write your code in Svelte which makes it easy to read, re-use and all the other benefits you get when you use a framework, and it makes for a blazing-fast web app as it complies down to vanilla JavaScript so that you don’t have the overhead of the JavaScript framework you’re using.

Svelte allows you to write less code. It also doesn’t use the concept of the Virtual DOM popularized by React. It instead surgically updates the DOM when the state of the app changes so the app starts fast and stays fast.

Prerequisites

For this tutorial, you need a basic knowledge of HTML, CSS and JavaScript.

You must also have installed the latest version of Node.js.

We’ll also be using npx, which comes installed by default with Node.js.

Throughout this tutorial we’ll be using yarn. If you don’t have yarn already installed, install it from here.

To make sure we’re on the same page, these are the versions used in this tutorial:

Node 12.10.0

npx 6.11.3

yarn 1.17.3

Getting Started with Svelte

In this tutorial, we’ll be building a Tic Tac Toe game in Svelte. By the end, you’ll be able to get up and running quickly with Svelte and get started in building your own apps in Svelte.

To get started, we must scaffold our app using degit. degit is more or less the same as git clone, but much quicker. You can learn more about it here.

Go ahead and make a new project by typing the following in the terminal:

$ npx degit sveltejs/template tic-tac-toe-svelte

npx lets you use the degit command without installing it globally.

Before npx, we would have to do the two following steps to achieve the same result:

$ npm install --global degit $ degit sveltejs/template tic-tac-toe-svelte

Thanks to npx, we don’t bloat our global namespace, and we always use the latest version of degit.

degit clones the repo https://github.com/sveltejs/template into a tic-tac-toe-svelte folder.

Go ahead into the tic-tac-toe-svelte directory and install the dependencies by typing the following in the terminal:

$ cd tic-tac-toe-svelte $ yarn

Now run the application by typing the following in the terminal:

$ yarn dev

Now open up the browser and go to http://localhost:5000 and you should see the following:

If you go into the src/ folder, you’ll see two files, App.svelte and main.js. main.js is the entry point of a Svelte app.

Open up the main.js and you should see the following:

import App from './App.svelte'; const app = new App({ target: document.body, props: { name: 'world' } }); export default app;

The above file imports App.svelte and instantiates it using a target element. It puts the component on the DOM’s document.body. It also passes name props to the App component. This prop will be accessed in App.svelte.

Components in Svelte are written using .svelte files which contain HTML, CSS and JavaScript. This will look familiar if youse worked with Vue.

Now open up App.svelte and you should see the following:

<script> export let name; </script> <style> h1 { color: purple; } </style> <h1>Hello {name}!</h1>

Firstly, we have the script tag inside, in which we have a named export called name. This should be similar to the prop mentioned in main.js.

Then we have a style tag that lets us style all the elements in that particular file, which is scoped to that file only so there’s no issue of cascading.

Then, at the bottom, we have an h1 tag, inside which we have Hello {name}!. The name in curly brackets will be replaced by the actual value. This is called value interpolation. That’s why Hello world! is printed on the screen.

Basic Structure of a Svelte Component

All .svelte files will basically have the following structure:

<script> /* Javascript logic */ </script> <style> /* CSS styles */ </style> <!-- HTML markup -->

The HTML markup will have some additional Svelte-specific syntax, but the rest is just plain HTML, CSS and JavaScript.

Making Tic Tac Toe in Svelte

Let’s get started with building our Tic Tac Toe game.

Replace main.js with the following:

import App from './App.svelte' const app = new App({ target: document.body, }) export default app

We’ve basically removed the props property from App component instantiation.

Now replace App.svelte with the following:

<script> const title = "Tic Tac Toe"; </script> <svelte:head> <title>{title}</title> </svelte:head> <h1>{title}</h1>

Here, we initialize a constant variable title with a string Tic Tac Toe.

Then, in the markup below, we use a special Svelte syntax, svelte:head, to set the title property in the head tag.

This is basically similar to doing this:

<head> <title>Tic Tac Toe</title> </head>

But the advantage of using the svelte:head syntax is that the title can be changed at runtime.

We then use the same title property in our h1 tag. It should now look like this:

Now create two other files in the src/ directory named Board.svelte and Square.svelte.

Open Square.svelte and paste in the following:

<script> export let value; </script> <style> .square { flex: 1 0 25%; width: 50px; height: 70px; background-color: whitesmoke; border: 2px solid black; margin: 5px; padding: 5px; font-size: 20px; text-align: center; } .square:hover { border: 2px solid red; } </style> <button class="square">{value}</button>

Basically, we’re creating a button and styling it.

Now open up Board.svelte and paste the following:

<script> import Square from "./Square.svelte"; let squares = [null, null, null, null, null, null, null, null, null]; </script> <style> .board { display: flex; flex-wrap: wrap; width: 300px; } </style> <div class="board"> {#each squares as square, i} <Square value={i} /> {/each} </div>

Here we’ve imported the Square component. We’ve also initialized the squares array, which will contain our X and 0’s data which is currently null.

The post How to Build a Tic Tac Toe Game with Svelte appeared first on SitePoint.

by Akshay Kadam via SitePoint https://ift.tt/2pOPORx

0 notes

Link

VS Code: Produtividade Infinita Front-End Web + [EBOOK FREE] ##UdemyFrancais ##udemykupon #Code #EBook #Free #Frontend #Infinita #Produtividade #Web VS Code: Produtividade Infinita Front-End Web + [EBOOK FREE] Alcance a produtividade infinita com o Visual Studio Code em mais de 100 aulas, contemplando CENTENAS de dicas, através de mais de 6 horas de aula! Nosso curso é baseado no livro "VS Code - Produtividade Infinita" disponível para compra na Amazon, também de nossa autoria, para garantir um conteúdo completo e profissional! PS: Uma versão digital do livro estará disponível para download de forma gratuita nos materiais disponibilizados nesse curso! Aprenda a se tornar ainda mais produtivo com: HTML CSS TYPESCRIPT JAVASCRIPT ANGULAR REACT VUE Em todos os setores do mercado, o principal favor na hora de avaliação é justamente a produtividade. Na programação não é diferente, tanto que um dos métodos de se avaliar a qualidade de um programador é chamado de KLOC/H, ou em português, Milhares de Linha de Código por Hora.Infelizmente, esse método não é dos melhores, pois mil linhas de Hello World tem um peso em menor do que mil linhas de machine learning, por exemplo. Sendo assim, o que muitas empresas fazem é passar tarefas em uma Sprint (intervalo de tempo para se concluir tais tarefas) e analisa se o desenvolvedor conseguiu ou não suprir a necessidade imposta pelos gerentes do projeto. Ou seja, querendo ou não, a avaliação é perante a sua produtividade! Neste curso vamos abordar justamente sobre isso: A Produtividade! Você receberá mais de 100 dicas de como melhorar sua produtividade utilizando o VS Code para as mais diversas situações do cotidiano, seguido de mais centenas de dicas próprias para linguagens específicas, abordando mais de 25 linguagens usadas no VS Code! Todas as dicas estão atualizadas referentes ao ano de 2019, reunindo a opnião, configuração e dicas de dezenas de especialistas no mercado! 👉 Activate Udemy Coupon 👈 Free Tutorials Udemy Review Real Discount Udemy Free Courses Udemy Coupon Udemy Francais Coupon Udemy gratuit Coursera and Edx ELearningFree Course Free Online Training Udemy Udemy Free Coupons Udemy Free Discount Coupons Udemy Online Course Udemy Online Training 100% FREE Udemy Discount Coupons https://www.couponudemy.com/blog/vs-code-produtividade-infinita-front-end-web-ebook-free/

0 notes

Text

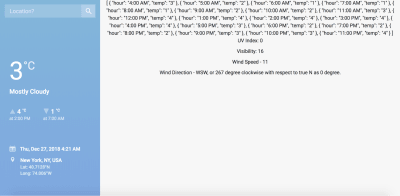

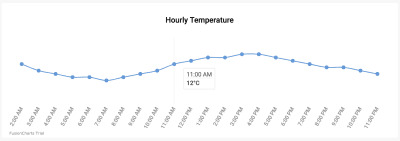

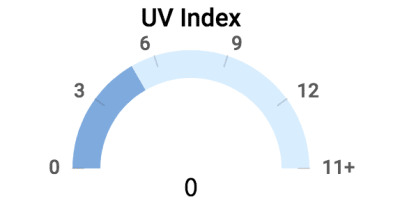

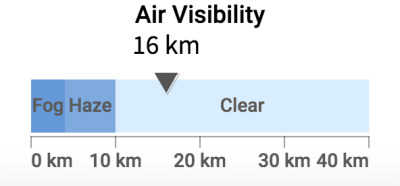

Using Vue.js To Create An Interactive Weather Dashboard With APIs

Using Vue.js To Create An Interactive Weather Dashboard With APIs

Souvik Sarkar

2019-02-01T13:00:18+01:002019-02-01T11:48:39+00:00

(This is a sponsored article.) In this tutorial, you will build a simple weather dashboard from scratch. It will be a client-end application that is neither a “Hello World” example, nor too intimidating in its size and complexity.

The entire project will be developed using tools from the Node.js + npm ecosystem. In particular, we will be heavily relying on the Dark Sky API for the data, Vue.js for all the heavy lifting, and FusionCharts for data visualization.

Prerequisites

We expect that you are familiar with the following:

HTML5 and CSS3 (we will also be using the basic features provided by Bootstrap;

JavaScript (especially ES6 way of using the language);

Node.js and npm (the basics of the environment and package management is just fine).

Apart from the ones mentioned above, it would be great if you have familiarity with Vue.js, or any other similar JavaScript framework. We don’t expect you to know about FusionCharts — it’s so easy to use that you will learn it on the fly!

Expected Learnings

Your key learnings from this project will be:

How to plan about implementing a good dashboard

How to develop applications with Vue.js

How to create data-driven applications

How to visualize data using FusionCharts

In particular, each of the sections take you a step closer to the learning goals:

An Introduction To The Weather Dashboard

This chapter gives you an overview of different aspects of the undertaking.

Create The Project

In this section, you learn about creating a project from scratch using the Vue command-line tool.

Customize The Default Project Structure

The default project scaffolding that you get in the previous section is not enough; here you learn the additional stuff needed for the project from a structural point of view.

Data Acquisition And Processing

This section is the meat of the project; all the critical code for acquiring and processing data from the API is showcased here. Expect to spend maximum time on this section.

Data Visualization With FusionCharts

Once we have all the data and other moving parts of the project stabilized, this section is dedicated towards visualizing the data using FusionCharts and a bit of CSS.

1. The Dashboard Workflow

Before we dive into the implementation, it is important to be clear about our plan. We break our plan into four distinct aspects:

Requirements

What are our requirements for this project? In other words, what are the things that we want to showcase through our Weather Dashboard? Keeping in mind that our intended audience are probably mere mortals with simple tastes, we would like to show them the following:

Details of the location for which they want to see the weather, along with some primary information about the weather. Since there are no stringent requirements, we will figure out the boring details later. However, at this stage, it is important to note that we will have to provide the audience a search box, so that they can provide input for the location of their interest.

Graphical information about the weather of their location of interest, such as:

Temperature variation for the day of query

Highlights of today’s weather:

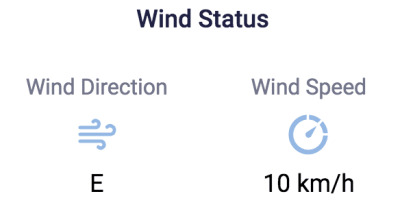

Wind Speed and Direction

Visibility

UV Index

Note: The data obtained from the API provides information regarding many other aspects of the weather. We choose not to use all of them for the sake of keeping the code to a minimum.

Structure

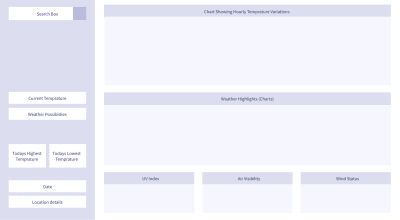

Based on the requirements, we can structure our dashboard as shown below:

(Large preview)

Data

Our dashboard is as good as the data we get, because there will be no pretty visualizations without proper data. There are plenty of public APIs that provide weather data — some of them are free, and some are not. For our project, we will collect data from the Dark Sky API. However, we will not be able to poll the API endpoint from the client end directly. Don’t worry, we have a workaround that will be revealed just at the right time! Once we get the data for the searched location, we will do some data processing and formatting — you know, the type of technicalities that helps us pay the bills.

Visualization

Once we get clean and formatted data, we plug it in to FusionCharts. There are very few JavaScript libraries in the world as capable as FusionCharts. Out of the vast number of offerings from FusionCharts, we will use only a few — all written in JavaScript, but works seamlessly when integrated with the Vue wrapper for FusionCharts.

Armed with the bigger picture, let’s get our hands dirty — it’s time to make things concrete! In the next section, you will create the basic Vue project, on top of which we will build further.

2. Creating The Project

To create the project, execute the following steps:

Install Node.js + npm

(If you have Node.js installed on your computer, skip this step.)

Node.js comes with npm bundled with it, so you don’t need to install npm separately. Depending on the operating system, download and install Node.js according to the instructions given here.

Once installed, it’s probably a good idea to verify if the software is working correctly, and what are their versions. To test that, open the command-line/terminal and execute the following commands:

node --version npm --version

Install packages with npm

Once you have npm up and running, execute the following command to install the basic packages necessary for our project.

npm install -g vue@2 vue-cli@2

Initialize project scaffolding with vue-cli

Assuming that the previous step has gone all well, the next step is to use the vue-cli — a command-line tool from Vue.js, to initialize the project. To do that, execute the following:

Initialize the scaffolding with webpack-simple template.

vue init webpack-simple vue_weather_dashboard

You will be asked a bunch of questions — accepting the defaults for all but the last question will be good enough for this project; answer N for the last one.

(Large preview)

Keep in mind that although webpack-simple is excellent for quick prototyping and light application like ours, it is not particularly suited for serious applications or production deployment. If you want to use any other template (although we would advise against it if you are a newbie), or would like to name your project something else, the syntax is:

vue init [template-name] [project-name]

Navigate to the directory created by vue-cli for the project.

cd vue_weather_dashboard

Install all the packages mentioned in the package.json, which has been created by the vue-cli tool for the webpack-simple template.

npm install

Start the development server and see your default Vue project working in the browser!

npm run dev

If you are new to Vue.js, take a moment to savor your latest achievement — you have created a small Vue application and its running at localhost:8080!

(Large preview)

Brief Explanation Of The Default Project Structure

It’s time to take a look at the structure inside the directory vue_weather_dashboard, so that you have an understanding of the basics before we start modifying it.

The structure looks something like this:

vue_weather_dashboard |--- README.md |--- node_modules/ | |--- ... | |--- ... | |--- [many npm packages we installed] | |--- ... | |--- ... |--- package.json |--- package-lock.json |--- webpack.config.js |--- index.html |--- src | |--- App.vue | |--- assets | | |--- logo.png | |--- main.js

Although it might be tempting to skip getting familiar with the default files and directories, if you are new to Vue, we strongly recommend at least taking a look at the contents of the files. It can be a good educational session and trigger questions that you should pursue on your own, especially the following files:

package.json, and just a glance at its cousin package-lock.json

webpack.config.js

index.html

src/main.js

src/App.vue

A brief explanation of each of the files and directories shown in the tree diagram are given below:

README.md

No prize for guessing — it is primarily for humans to read and understand the steps necessary for creating the project scaffolding.

node_modules/

This is the directory where npm downloads the packages necessary for kickstarting the project. The information about the packages necessary are available in the package.json file.

package.json

This file is created by the vue-cli tool based on the requirements of the webpack-simple template, and contains information about the npm packages (including with their versions and other details) that must be installed. Take a hard look at the content of this file — this is where you should visit and perhaps edit to add/delete packages necessary for the project, and then run npm install. Read more about package.json here.

package-lock.json

This file is created by npm itself, and is primarily meant for keeping a log of things that npm downloaded and installed.

webpack.config.js

This a JavaScript file that contains the configuration of webpack — a tool that bundles different aspects of our project together (code, static assets, configuration, environments, mode of use, etc.), and minifies before serving it to the user. The benefit is that all things are tied together automatically, and the user experience enhances greatly because of the improvement in the application’s performance (pages are served quickly and loads faster on the browser). As you might encounter later, this is the file that needs to be inspected when something in the build system does not works the way it is intended to be. Also, when you want to deploy the application, this is one of the key files that needs to be edited (read more here).

index.html

This HTML file serves as the matrix (or you can say, template) where data and code is to be embedded dynamically (that’s what Vue primarily does), and then served to the user.

src/main.js

This JavaScript file contains code that primarily manages top/project level dependencies, and defines the topmost level Vue component. In short, it orchestrates the JavaScript for the entire project, and serves as the entry point of the application. Edit this file when you need to declare project-wide dependencies on certain node modules, or you want something to be changed about the topmost Vue component in the project.

src/App.vue

In the previous point, when we were talking about the “topmost Vue component”, we were essentially talking about this file. Each .vue file in the project is a component, and components are hierarchically related. At the start, we have only one .vue file, i.e. App.vue, as our only component. But shortly we will add more components to our project (primarily following the structure of the dashboard), and link them in accordance to our desired hierarchy, with App.vue being the ancestor of all. These .vue files will contain code in a format that Vue wants us to write. Don’t worry, they are JavaScript code written maintaining a structure that can keep us sane and organized. You have been warned — by the end of this project, if you are new to Vue, you may get addicted to the template — script — style way of organizing code!

Now that we have created the foundation, it’s time to:

Modify the templates and tweak the configuration files a bit, so that the project behaves just the way we want.

Create new .vue files, and implement the dashboard structure with Vue code.

We will learn them in the next section, which is going to be a bit long and demands some attention. If you need caffeine or water, or want to discharge — now is the time!

3. Customizing The Default Project Structure

It’s time to tinker with the foundation that the scaffolded project has given us. Before you start, ensure that the development server provided by webpack is running. The advantage of running this server continuously is that any changes you make in the source code — one you save it and refresh the web page — it gets immediately reflected on the browser.

If you want to start the development server, just execute the following command from the terminal (assuming your current directory is the project directory):

npm run dev

In the following sections, we will modify some of the existing files, and add some new files. It will be followed by brief explanations of the content of those files, so that you have an idea of what those changes are meant to do.

Modify Existing Files

index.html

Our application is literally a single page application, because there is just one webpage that gets displayed on the browser. We will talk about this later, but first let’s just make our first change — altering the text within the <title> tag.

With this small revision, the HTML file looks like the following:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <head> <meta charset="utf-8"> <!-- Modify the text of the title tag below --> <title>Vue Weather Dashboard</title> </head> <body> <div id="app"></div> <script src="/dist/build.js"></script> </body> </html>

Take a moment to refresh the webpage at localhost:8080, and see the change reflected on the title bar of the tab on the browser — it should say “Vue Weather Dashboard”. However, this was just to demonstrate you the process of making changes and verifying if it’s working. We have more things to do!

This simple HTML page lacks many things that we want in our project, especially the following:

Some meta information

CDN links to Bootstrap (CSS framework)

link to custom stylesheet (yet to be added in the project)

Pointers to the Google Maps Geolocation API from <script> tag

After adding those things, the final index.html has the following content:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <head> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html;charset=utf-8" /> <meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="IE=edge"> <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1, shrink-to-fit=no"> <link rel="stylesheet" href="//maxcdn.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/4.0.0/css/bootstrap.min.css"> <link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="src/css/style.css"> <title>Weather Dashboard</title> <script src="https://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/js?key=AIzaSyC-lCjpg1xbw-nsCc11Si8Ldg2LKYizqI4&libraries=places"></script> </head> <body> <div id="app"></div> <script src="/dist/build.js"></script> </body> </html>

Save the file, and refresh the webpage. You might have noticed a slight bump while the page was getting loaded — it is primarily due to the fact that the page style is now being controlled by Bootstrap, and the style elements like fonts, spacing, etc. are different from the default we had earlier (if you are not sure, roll back to the default and see the difference).

(Large preview)

Note: One important thing before we move on — the URL for the Google Maps API contains a key which is a property of FusionCharts. For now, you can use this key to build the project, as we don’t want you to get bogged down by these type of minute details (which can be distractions while you are new). However, we strongly urge you to generate and use your own Google Maps API key once you have made some progress and feel comfortable to pay attention to these tiny details.

package.json

At the time of writing this, we used certain versions of the npm packages for our project, and we know for sure that those things work together. However, by the time you are executing the project, it is very much possible that the latest stable versions of the packages that npm downloads for you are not the same as we used, and this might break the code (or do things that are beyond our control). Thus, it is very important to have the exact same package.json file that was used to build this project, so that our code/explanations and the results you get are consistent.

The content of the package.json file should be:

{ "name": "vue_weather_dashboard", "description": "A Vue.js project", "version": "1.0.0", "author": "FusionCharts", "license": "MIT", "private": true, "scripts": { "dev": "cross-env NODE_ENV=development webpack-dev-server --open --hot", "build": "cross-env NODE_ENV=production webpack --progress --hide-modules" }, "dependencies": { "axios": "^0.18.0", "babel": "^6.23.0", "babel-cli": "^6.26.0", "babel-polyfill": "^6.26.0", "fusioncharts": "^3.13.3", "moment": "^2.22.2", "moment-timezone": "^0.5.21", "vue": "^2.5.11", "vue-fusioncharts": "^2.0.4" }, "browserslist": [ "> 1%", "last 2 versions", "not ie

We encourage you to go through the new package.json, and figure out what are functions of different objects in the json. You may prefer changing the value of the “author” key to your name. Also, the packages mentioned in the dependencies will reveal themselves at the right time in the code. For the time being, it’s sufficient to know that:

babel-related packages are for properly handling the ES6 style code by the browser;

axios deals with Promise-based HTTP requests;

moment and moment-timezone are for date/time manipulation;

fusioncharts and vue-fusioncharts are responsible for rendering charts:

vue, for obvious reasons.

webpack.config.js

As with package.json, we suggest you to maintain a webpack.config.js file that is consistent with the one we used for building the project. However, before making any changes, we recommend you to carefully compare the default code in the webpack.config.js, and the code we have provided below. You will notice quite a few differences — google them and have a basic idea of what they mean. Since explaining webpack configurations in depth is out of the scope of this article, you are on your own in this regard.

The customized webpack.config.js file is as follows:

var path = require('path') var webpack = require('webpack') module.exports = { entry: ['babel-polyfill', './src/main.js'], output: { path: path.resolve(__dirname, './dist'), publicPath: '/dist/', filename: 'build.js' }, module: { rules: [ { test: /\.css$/, use: [ 'vue-style-loader', 'css-loader' ], }, { test: /\.vue$/, loader: 'vue-loader', options: { loaders: { } // other vue-loader options go here } }, { test: /\.js$/, loader: 'babel-loader', exclude: /node_modules/ }, { test: /\.(png|jpg|gif|svg)$/, loader: 'file-loader', options: { name: '[name].[ext]?[hash]' } } ] }, resolve: { alias: { 'vue$': 'vue/dist/vue.esm.js' }, extensions: ['*', '.js', '.vue', '.json'] }, devServer: { historyApiFallback: true, noInfo: true, overlay: true, host: '0.0.0.0', port: 8080 }, performance: { hints: false }, devtool: '#eval-source-map' } if (process.env.NODE_ENV === 'production') { module.exports.devtool = '#source-map' // http://vue-loader.vuejs.org/en/workflow/production.html module.exports.plugins = (module.exports.plugins || []).concat([ new webpack.DefinePlugin({ 'process.env': { NODE_ENV: '"production"' } }), new webpack.optimize.UglifyJsPlugin({ sourceMap: true, compress: { warnings: false } }), new webpack.LoaderOptionsPlugin({ minimize: true }) ]) }

With changes made to the project’s webpack.config.js, it’s imperative that you stop the development server which is running (Ctrl + C), and restart it with the following command executed from the project’s directory after installing all the packages mentioned in the package.json file:

npm install npm run dev

With this, the ordeal of tweaking the configurations and ensuring that the right packages are in place ends. However, this also marks the journey of modifying and writing code, which is a bit long but also very rewarding!

src/main.js

This file is the key to top-level orchestration of the project — it is here that we define:

What the top level dependencies are (where to get the most important npm packages necessary);

How to resolve the dependencies, along with instructions to Vue on using plugins/wrappers, if any;

A Vue instance that manages the topmost component in the project: src/App.vue (the nodal .vue file).

In line with our goals for the src/main.js file, the code should be:

// Import the dependencies and necessary modules import Vue from 'vue'; import App from './App.vue'; import FusionCharts from 'fusioncharts'; import Charts from 'fusioncharts/fusioncharts.charts'; import Widgets from 'fusioncharts/fusioncharts.widgets'; import PowerCharts from 'fusioncharts/fusioncharts.powercharts'; import FusionTheme from 'fusioncharts/themes/fusioncharts.theme.fusion'; import VueFusionCharts from 'vue-fusioncharts'; // Resolve the dependencies Charts(FusionCharts); PowerCharts(FusionCharts); Widgets(FusionCharts); FusionTheme(FusionCharts); // Globally register the components for project-wide use Vue.use(VueFusionCharts, FusionCharts); // Instantiate the Vue instance that controls the application new Vue({ el: '#app', render: h => h(App) })

src/App.vue

This is one of the most important files in the entire project, and represents the topmost component in the hierarchy — the entire application itself, as a whole. For our project, this component will do all the heavy lifting, which we will explore later. For now, we want to get rid of the default boilerplate, and put something of our own.

If you are new to Vue’s way of organizing code, it would be better to get an idea of the general structure within the .vue files. The .vue files comprises of three sections:

Template

This is where the HTML template for the page is defined. Apart from the static HTML, this section also contains Vue’s way of embedding dynamic content, using the double curly braces .

Script

JavaScript rules this section, and is responsible for generating dynamic content that goes and sits within the HTML template at appropriate places. This section is primarily an object that is exported, and consists of:

Data

This is a function itself, and usually it returns some desired data encapsulated within a nice data structure.

Methods

An object that consists of one or more functions/methods, each of which usually manipulates data in some way or the other, and also controls the dynamic content of the HTML template.

Computed

Much like the method object discussed above with one important distinction — while all the functions within the method object are executed whenever any one of them is called, the functions within the computed object behaves much more sensibly, and executes if and only if it has been called.

Style

This section is for CSS styling that applies to the HTML of the page (written within template) — put the good old CSS here to make your pages beautiful!

Keeping the above paradigm in mind, let’s minimally customize the code in App.vue:

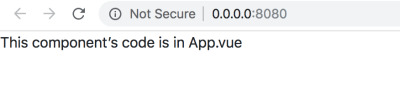

<template> <div id="app"> <p>This component’s code is in </p> </div> </template> <script> export default { data() { return { filename: 'App.vue' } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

Remember that the above code snippet is simply for testing out that App.vue is working with our own code in it. It will later go on through a lot of changes, but first save the file and refresh the page on the browser.

(Large preview)

At this point, it’s probably a good idea to get some help in tooling. Check out the Vue devtools for Chrome, and if you don’t have much problems in using Google Chrome as your default browser for development, install the tool and play around with it a bit. It will come in extremely handy for further development and debugging, when things becomes more complicated.

Additional Directories And Files

The next step would be to add additional files, so that the structure of our project becomes complete. We would add the following directories and files:

src/css/ — style.css

src/assets/ — calendar.svg — vlocation.svg — search.svg — winddirection.svg — windspeed.svg

src/components/ — Content.vue — Highlights.vue — TempVarChart.vue — UVIndex.vue — Visibility.vue — WindStatus.vue

Note: Save the hyperlinked .svg files in your project.

Create the directories and files mentioned above. The final project structure should like look (remember to delete folders and files from the default structure that are now unnecessary):

vue_weather_dashboard/ |--- README.md |--- node_modules/ | |--- ... | |--- ... | |--- [many npm packages we installed] | |--- ... | |--- ... |--- package.json |--- package-lock.json |--- webpack.config.js |--- index.html |--- src/ | |--- App.vue | |--- css/ | | |--- style.css | |--- assets/ | | |--- calendar.svg | | |--- location.svg | | |--- location.svg | | |--- winddirection.svg | | |--- windspeed.svg | |--- main.js | |--- components/ | | |--- Content.vue | | |--- Highlights.vue | | |--- TempVarChart.vue | | |--- UVIndex.vue | | |--- Visibility.vue | | |--- WindStatus.vue

There might be some other files, like .babelrc, .gitignore, .editorconfig, etc. in the project’s root folder. You may ignore them safely for now.

In the following section, we will add minimal content to the newly added files, and test whether they are properly working.

src/css/style.css

Although it will not be of much use immediately, copy the following code to the file:

@import url("https://fonts.googleapis.com/css?family=Roboto:300,400,500"); :root { font-size: 62.5%; } body { font-family: Roboto; font-weight: 400; width: 100%; margin: 0; font-size: 1.6rem; } #sidebar { position: relative; display: flex; flex-direction: column; background-image: linear-gradient(-180deg, #80b6db 0%, #7da7e2 100%); } #search { text-align: center; height: 20vh; position: relative; } #location-input { height: 42px; width: 100%; opacity: 1; border: 0; border-radius: 2px; background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.2); margin-top: 16px; padding-left: 16px; color: #ffffff; font-size: 1.8rem; line-height: 21px; } #location-input:focus { outline: none; } ::placeholder { color: #FFFFFF; opacity: 0.6; } #current-weather { color: #ffffff; font-size: 8rem; line-height: 106px; position: relative; } #current-weather>span { color: #ffffff; font-size: 3.6rem; line-height: 42px; vertical-align: super; opacity: 0.8; top: 15px; position: absolute; } #weather-desc { font-size: 2.0rem; color: #ffffff; font-weight: 500; line-height: 24px; } #possibility { color: #ffffff; font-size: 16px; font-weight: 500; line-height: 19px; } #max-detail, #min-detail { color: #ffffff; font-size: 2.0rem; font-weight: 500; line-height: 24px; } #max-detail>i, #min-detail>i { font-style: normal; height: 13.27px; width: 16.5px; opacity: 0.4; } #max-detail>span, #min-detail>span { color: #ffffff; font-family: Roboto; font-size: 1.2rem; line-height: 10px; vertical-align: super; } #max-summary, #min-summary { opacity: 0.9; color: #ffffff; font-size: 1.4rem; line-height: 16px; margin-top: 2px; opacity: 0.7; } #search-btn { position: absolute; right: 0; top: 16px; padding: 2px; z-index: 999; height: 42px; width: 45px; background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.2); border: none; } #dashboard-content { text-align: center; height: 100vh; } #date-desc, #location-desc { color: #ffffff; font-size: 1.6rem; font-weight: 500; line-height: 19px; margin-bottom: 15px; } #date-desc>img { top: -3px; position: relative; margin-right: 10px; } #location-desc>img { top: -3px; position: relative; margin-left: 5px; margin-right: 15px; } #location-detail { opacity: 0.7; color: #ffffff; font-size: 1.4rem; line-height: 20px; margin-left: 35px; } .centered { position: fixed; top: 45%; left: 50%; transform: translate(-50%, -50%); } .max-desc { width: 80px; float: left; margin-right: 28px; } .temp-max-min { margin-top: 40px } #dashboard-content { background-color: #F7F7F7; } .custom-card { background-color: #FFFFFF !important; border: 0 !important; margin-top: 16px !important; margin-bottom: 20px !important; } .custom-content-card { background-color: #FFFFFF !important; border: 0 !important; margin-top: 16px !important; margin-bottom: 0px !important; } .header-card { height: 50vh; } .content-card { height: 43vh; } .card-divider { margin-top: 0; } .content-header { color: #8786A4; font-size: 1.4rem; line-height: 16px; font-weight: 500; padding: 15px 10px 5px 15px; } .highlights-item { min-height: 37vh; max-height: 38vh; background-color: #FFFFFF; } .card-heading { color: rgb(33, 34, 68); font-size: 1.8rem; font-weight: 500; line-height: 21px; text-align: center; } .card-sub-heading { color: #73748C; font-size: 1.6rem; line-height: 19px; } .card-value { color: #000000; font-size: 1.8rem; line-height: 21px; } span text { font-weight: 500 !important; } hr { padding-top: 1.5px; padding-bottom: 1px; margin-bottom: 0; margin-top: 0; line-height: 0.5px; } @media only screen and (min-width: 768px) { #sidebar { height: 100vh; } #info { position: fixed; bottom: 50px; width: 100%; padding-left: 15px; } .wrapper-right { margin-top: 80px; } } @media only screen and (min-width:1440px) { #sidebar { width: 350px; max-width: 350px; flex: auto; } #dashboard-content { width: calc(100% — 350px); max-width: calc(100% — 350px); flex: auto; } }

src/assets/

In this directory, download and save the .svg files mentioned below:

calendar.svg

location.svg

search.svg

winddirection.svg

windspeed.svg

src/components/Content.vue

This is what we call a dumb component — a placeholder, that is there just to maintain the hierarchy, and essentially passes on data to its child components.

Remember that there is no technical bar for writing all our code in the App.vue file, but we take the approach of splitting up the code by nesting the components for two reasons:

To write clean code, which aids readability and maintainability;

To replicate the same structure that we will see on screen, i.e., the hierarchy.

Before we nest the component defined in Content.vue within the root component App.vue, let’s write some toy (but educational) code for Content.vue:

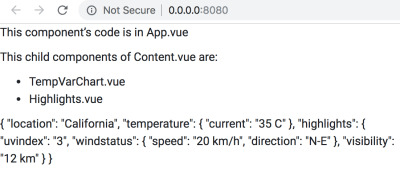

<template> <div> <p>This child components of Content.vue are:</p> <ul> <li v-for="child in childComponents"></li> </ul> </div> </template> <script> export default { data () { return { childComponents: ['TempVarChart.vue', 'Highlights.vue'] } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

In the code, carefully observe and understand the following:

Within the <script> tag (where we obviously write some JavaScript code), we define an object that is exported (made available to other files) by default. This object contains a function data(), that returns an array object called childComponents, with its elements being names of the component files that should be nested further.

Within the <template> tag (where we write some HTML template), the thing of interest is the <ul>.

Within the unordered list, each list item should be names of the intended child components, as defined in the array object childComponents. Moreover, the list should automatically extend till the last element of the array. Seems like we should write a for-loop, isn’t it? We do that by using the v-for directive provided by Vue.js. The v-for directive:

Acts as an attribute of the <li> tag, iterates through the array, renders the names of the child components where the iterator is mentioned within the brackets (where we write the text for the list items).

The code and the explanation above forms the basis of your subsequent understanding of how the script and the template are interrelated, and how we can use the directives provided by Vue.js.

We have learnt quite a lot, but even after all these, we have one thing left to learn about seamlessly connecting components in hierarchy — passing data down from the parent component to its children. For now, we need to learn how to pass some data from src/App.vue to src/components/Content.vue, so that we can use the same techniques for the rest of the component nesting in this project.

Data trickling down from the parent to the child components might sound simple, but the devil is in the details! As briefly explained below, there are multiple steps involved in making it work:

Defining and the data

For now, we want some static data to play with — an object containing hard-coded values about different aspects of weather will just be fine! We create an object called weather_data and return it from the data() function of App.vue. The weather_data object is given in the snippet below:

weather_data: { location: "California", temperature: { current: "35 C", }, highlights: { uvindex: "3", windstatus: { speed: "20 km/h", direction: "N-E", }, visibility: "12 km", }, },

Passing the data from the parent

To pass the data, we need a destination where we want to send the data! In this case, the destination is the Content.vue component, and the way to implement it is to:

Assign the weather_data object to a custom attribute of the <Content> tag

Bind the attribute with the data using the v-bind: directive provided by Vue.js, which makes the attribute value dynamic (responsive to changes made in the original data).

<Content v-bind:weather_data=“weather_data”></Content>

Defining and passing the data is handled at the source side of the handshake, which in our case is the App.vue file.

The code for the App.vue file, at its current status, is given below:

<template> <div id="app"> <p>This component’s code is in </p> <Content v-bind:weather_data="weather_data"></Content> </div> </template> <script> import Content from './components/Content.vue' export default { name: 'app', components: { 'Content': Content }, data () { return { filename: 'App.vue', weather_data: { location: "California", temperature: { current: "35 C", }, highlights: { uvindex: "3", windstatus: { speed: "20 km/h", direction: "N-E", }, visibility: "12 km", }, }, } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

(Large preview)

With the data defined and passed from the source (parent component), it is now the child’s responsibility to receive the data and render it appropriately, as explained in the next two steps.

Receiving the data by the child

The child component, in this case Content.vue, must receive the weather_data object send to it by the parent component App.vue. Vue.js provides a mechanism to do so — all you need is an array object called props, defined in the default object exported by Content.vue. Each element of the array props is a name of the data objects it wants to receive from its parent. For now, the only data object that it is supposed to receive is weather_data from App.vue. Thus, the props array looks like:

<template> // HTML template code here </template> <script> export default { props: ["weather_data"], data () { return { // data here } }, } </script> <style> // component specific CSS here </style>

Rendering the data in the page

Now that we have ensured receiving the data, the last task we need to complete is to render the data. For this example, we will directly dump the received data on the web page, just to illustrate the technique. However, in real applications (like the one we are about to build), data normally goes through lots of processing, and only the relevant parts of it are displayed in ways that suits the purpose. For example, in this project we will eventually get raw data from the weather API, clean and format it, feed the data to the data structures necessary for the charts, and then visualize it. Anyway, to display the raw data dump, we will just use the brackets that Vue understands, as shown in the snippet below:

<template> <div id="pagecontent"> // other template code here </div> </template>

It’s now time to assimilate all the bits and pieces. The code for Content.vue — at its current status — is given below:

<template> <div id="pagecontent"> <p>This child components of Content.vue are:</p> <ul> <li v-for="child in childComponents"></li> </ul> </div> </template> <script> export default { props: ["weather_data"], data () { return { childComponents: ['TempVarChart.vue', 'Highlights.vue'] } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> #pagecontent { border: 1px solid black; padding: 2px; } </style>

(Large preview)

After making the changes discussed above, refresh the webpage on the browser and see how it looks. Take a moment to appreciate the complexity that Vue handles — if you modify the weather_data object in App.vue, it gets silently conveyed to Content.vue, and eventually to the browser displaying the webpage! Try by changing the value for the key location.

Although we have learned about props and data binding using static data, we will be using dynamic data collected using web APIs in the application, and will change the code accordingly.

Summary

Before we move on to the rest of the .vue files, let’s summarize what we have learnt while we wrote the code for App.vue and components/Content.vue:

The App.vue file is what we call the root component — the one that sits at the top of the component hierarchy. The rest of the .vue files represents components that are its direct child, grandchild, and so on.

The Content.vue file is a dummy component — its responsibility is to pass on the data to levels below and maintain the structural hierarchy, so that our code remains consistent with the philosophy “*what we see is what we implement*”.

The parent-child relationship of component does not happen out of thin air — you must register a component (either globally or locally, depending on the intended usage of the component), and then nest it using custom HTML tags (whose spellings are the exact same as that of the names with which the components has been registered).

Once registered and nested, data is passed on from parent to child components, and the flow is never reverse (bad things will happen if the project architecture allows backflow). The parent component is the relative source of the data, and it passes down relevant data to its children using the v-bind directive for the attributes of the custom HTML elements. The child receives the data intended for it using props, and then decides on its own what to do with the data.

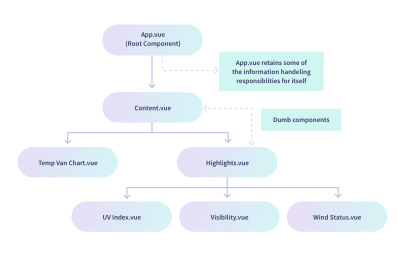

For the rest of the components, we will not indulge in detailed explanation — we will just write the code based on the learnings from the above summary. The code will be self-evident, and if you get confused about the hierarchy, refer to the diagram below:

(Large preview)

The diagram says that TempVarChart.vue and Highlights.vue are the direct child of Content.vue. Thus, it might be a good idea to prepare Content.vue for sending data to those components, which we do using the code below:

<template> <div id="pagecontent"> <p>This child components of Content.vue are:</p> <ul> <li v-for="child in childComponents"></li> </ul> <temp-var-chart :tempVar="tempVar"></temp-var-chart> <today-highlights :highlights="highlights"></today-highlights> </div> </template> <script> import TempVarChart from './TempVarChart.vue' import Highlights from './Highlights.vue' export default { props: ["weather_data"], components: { 'temp-var-chart': TempVarChart, 'today-highlights': Highlights }, data () { return { childComponents: ['TempVarChart.vue', 'Highlights.vue'], tempVar: this.weather_data.temperature, highlights: this.weather_data.highlights, } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

Once you save this code, you will get errors — don’t worry, it is expected. It will be fixed once you have the rest of the component files ready. If it bothers you not to be able to see the output, comment out the lines containing the custom element tags <temp-var-chart> and <today-highlights>.

For this section, this is the final code of Content.vue. For the rest of this section, we will reference to this code, and not the previous ones that we wrote for learning.

src/components/TempVarChart.vue

With its parent component Content.vue passing on the data, TempVarChart.vue must be set up to receive and render the data, as shown in the code below:

<template> <div id="tempvarchart"> <p>Temperature Information:</p> </div> </template> <script> export default { props: ["tempVar"], data () { return { } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

src/components/Highlights.vue

This component will also receive data from App.vue — its parent component. After that, it should be linked with its child components, and relevant data should be passed on to them.

Let’s first see the code for receiving data from the parent:

<template> <div id="highlights"> <p>Weather Highlights:</p> </div> </template> <script> export default { props: ["highlights"], data () { return { } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

At this point, the web page looks like the image below:

(Large preview)

Now we need to modify the code of Highlights.vue to register and nest its child components, followed by passing the data to children. The code for it is as follows:

<template> <div id="highlights"> <p>Weather Highlights:</p> <uv-index :highlights="highlights"></uv-index> <visibility :highlights="highlights"></visibility> <wind-status :highlights="highlights"></wind-status> </div> </template> <script> import UVIndex from './UVIndex.vue'; import Visibility from './Visibility.vue'; import WindStatus from './WindStatus.vue'; export default { props: ["highlights"], components: { 'uv-index': UVIndex, 'visibility': Visibility, 'wind-status': WindStatus, }, data () { return { } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

Once you save the code and see the web page, you are expected to see errors in the Developer Console tool provided by the browser; they appear because although Highlights.vue is sending data, nobody is receiving them. We are yet to write the code for the children of Highlights.vue.

Observe that we have not done much of the data processing, i.e, we have not extracted the individual factors of weather data that goes under the Highlights section of the dashboard. We could have done that in the data() function, but we preferred to keep Highlights.vue a dumb component that just passes on the entire data dump it receives to each of the children, who then own their own extracts what is necessary for them. However, we encourage you to try out extracting data in the Highlights.vue, and send relevant data down to each child component — it’s a good practice exercise nonetheless!

src/components/UVIndex.vue

The code for this component receives the data dump of highlights from Highlights.vue, extracts the data for UV Index, and renders it on the page.

<template> <div id="uvindex"> <p>UV Index: </p> </div> </template> <script> export default { props: ["highlights"], data () { return { uvindex: this.highlights.uvindex } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

src/components/Visibility.vue

The code for this component receives the data dump of highlights from Highlights.vue, extracts the data for Visibility, and renders it on the page.

<template> <div id="visibility"> <p>Visibility: </p> </div> </template> <script> export default { props: ["highlights"], data () { return { visibility: this.highlights.visibility, } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

src/components/WindStatus.vue

The code for this component receives the data dump of highlights from Highlights.vue, extracts the data for Wind Status (speed and direction), and renders it on the page.

<template> <div id="windstatus"> <p>Wind Status:</p> <p>Speed — ; Direction — </p> </div> </template> <script> export default { props: ["highlights"], data () { return { speed: this.highlights.windstatus.speed, direction: this.highlights.windstatus.direction } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

After adding the code for all the components, take a look at the web page on the browser.

(Large preview)

Not to dishearten, but all these toiling was just to link the components in hierarchy, and test out whether data flow is happening between them or not! In the next section, we will throw away most of the code we have written so far, and add a lot more pertaining to the actual project. However, we will certainly retain the structure and nesting of the components; the learnings from this section will allow us to build a decent dashboard with Vue.js.

4. Data Acquisition And Processing

Remember the weather_data object in App.vue? It had some hard-coded data that we used to test whether all the components are working correctly, and also to help you learn some basic aspects of Vue application without getting bogged down in the details of real-world data. However, it’s now time that we shed our shell, and step out into the real world, where data from the API will dominate most of our code.

Preparing Child Components To Receive And Process Real Data