#which was brehon law!

Text

Why has my planning for a fun lesbian detective story turned into researching brehon law. WHAT IS HAPPENING!!!!

#oh. but why would a small detective agency be solving a murder instead of the police. i dont want to write about a cop#oh! the police were an english invention! what if i just did ireland where the english never invaded!#obviously i know WHY#so.#its going to be set in modern day ireland#and i was going#and then i was like#but this now means i have to figure out the possible structure of an ireland that was never colonised by the english#that is also similar enough to real modern ireland#but the base of our law is the british law system and if we were never conquered it makes no sense#so instead i have to go back to the most recent non-colonised law system we had#which was brehon law!#currently the plan is england and ireland were close trade partners or something#which is why its in english mostly and not entirely irish 😅😅#sadly my irish isnt good enough to write a whole screenplay as gaielge. maybe one day though!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

every so often i do get people asking for books recommendations for getting into irish mythology (just answered an ask privately about it.. at length) and this one deserves to be in a public post but seriously read The Táin (translated by Thomas Kinsella). This is THE best book and best translation. it's a fascinating look into life under Brehon Law, especially where female characters are concerned - i'm not saying it's not sexist but it's not the sexism you expect from a prechristian story put to writing by monks in the middle ages. this is why you need the Kinsella translation, earlier Victorian translations heavily censored 'unseemly' topics, like expressions of womens' sexual desire (which is almost constant in this book i'm ngl the girls are getting it. cúchulainn's wife emer refuses to marry him until he kills 900 men for her and of course our hero kills 900 men for her what is he, a bad husband??)

but also it's just a good story and extremely funny. it's something a lot of recommendations never really express - it is a story with a sense of humour and you will laugh. it's designed to entertain people around a fire during black winter nights.

it's a written version of the Ulster Cycle, a series of intertwined stories about our best boy Cúchulainn becoming the sole defender of Ulster after all the other men are cursed to experience debilitating period cramps by Macha. He has to defend Ulster because the queen of Connacht is coming to steal a bull belonging to them, and she's doing that because she got in a fight with her consort* over who's the richest and found that their wealth was exactly equal aside from him having a nicer bull. so she goes to war to get her own awesome bull.

best book ever. read it

#*in the podcast candlelit tales' retelling of the Táin (also recommended) they give him a thick blackrock accent and it's just so#like. there's layers there. oh god there's layers

136 notes

·

View notes

Note

So I’ve been getting more into broader brehon law, not just marriage law, and is it true they had laws about how many different colors you could wear? I can’t find any sources about it but maybe I’m just not looking hard enough

That comes from one kind of famous (ish?) passage from the Annals, that reads as follows (from the O'Donovan translation):

Do I think it was something people followed? ...probably not, honestly. We don't see much reference to it elsewhere. Not to say there were NO restrictions, but it's to say that I think it's often taken 100% uncritically and you'd think we'd see more reference to it elsewhere, in the actual lawbooks, if that was the case. (Though, naturally, some of it's practical, in the sense that...would a slave be able to have more than one color? Being a slave? Very likely not.) It's the issue with all sumptuary laws, which is "to what extent were these things widely being used?"

To quote from Sparky Booker's "Moustaches, Mantles, and Saffron Shirts: What Motivated Sumptuary Law in Medieval English Ireland?": "In terms of implementation, the success of enforcement of sumptuary laws varied.11 Indeed, historians disagree about whether these laws were intended to be enforced fully, or whether they were 'primarily symbolic,' a method of 'affirm[ing] values' and even actively shaping the social world by

enshrining socio-economic divisions in law."

We know that medieval Ireland had a number of colors associated with the aristocracy: purple (like with the rest of Europe) seems to be common, white, red, like in this description from the Táin (Recension 1, O'Rahilly's translation):

"He held a light sharp spear which shimmered. He was wrapped in a purple, fringed mantle, with a silver brooch in the mantle over his breast. He wore a white hooded tunic with red insertion and carried outside his garments a golden-hilted sword."

Likewise, the famous description of Etáin in Togail Bruidne Da Derga (Stokes' translation):

"A mantle she had, curly and purple, a beautiful cloak, and in the mantle silvery fringes arranged, and a brooch of fairest gold. A kirtle she wore, long, hooded, hard-smooth, of green silk, with red embroidery of gold. Marvellous clasps of gold and silver in the kirtle on her breasts and her shoulders and spaulds on every side. The sun kept shining upon her, so that the glistening of the gold against the sun from the green silk was manifest to men."

For more on this, see Niamh Whitfield, "Aristocratic Display in Early Medieval Ireland in Fiction and in Fact: The Dazzling White Tunic and Purple Cloak", which she's generously put on Academia.

After the English colonization of Ireland, you have new sumptuary laws being put into place -- Booker discusses the earliest case we have, from 1297, when a hairstyle known as the "cúlán" was banned for Englishmen, with the enactment complaining that the Englishmen were taking it up to such an extent that they were getting killed after being mistaken for Irishmen. (I feel like there is a solution to this that does not involve banning the hairstyle, let me think...)

You had similar fines being imposed on saffron sleeves or kerchiefs for women, or wearing a mantle in general for men, as of 1466 in Dublin -- these aren't as a matter of maintaining social class so much as preserving a distinction between the English and the Irish (what's interesting, of course, is that the English had to have been adopting these fashions to some extent for the law to be needed.) And we see them routinely going back to this aversion towards saffron colors, since it was associated extensively with Ireland and Irishness, and a particularly high value one at that.

So: Eochaidh Eadghaghach -- that section in the annals provides the quote that says that this is a thing that happened -- I leave it to you to decide whether it was ever practiced or even in place in the first place. I think it might have, if only as a societal ideal, but I'm incredibly doubtful. We know that colors often ARE used as a way of marking social standing in the literature, but I don't think it was as regimented as that quote suggests. Sumptuary laws ARE better recorded in a post-Norman invasion context, usually (though not ALWAYS) as a means of marking out the Irish from the English populations (even though we know, both from this and other evidence, that these lines weren't always as firm as the authorities might have liked.)

I know that Kelly also goes into a lot of details re: colors and dyes in his "Early Irish Farming" -- if you're looking to get into the world of day to day life in Ireland, there isn't a better source.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Thing Of Vikings Chapter 67: Kill With A Borrowed Knife

Chapter 67: Kill With A Borrowed Knife

Prior to the Imperial Assembly Of Law, the North Sea Empire's legal system was a patchwork of numerous local codes, ordinances, and jurisdictions, in multiple languages, and with numerous cultural and religious outlooks. The purpose of the Assembly was to create a pan-imperial legal code that was acceptable to all peoples of the Empire, and, as with all compromises, it generally succeeded at making everyone equally unhappy, even as they recognized the validity of the compromises. Religious law was left in the hands of the specific faiths, making the code officially secular, which pleased no one and yet satisfied everyone. Other elements were picked from the component legal codes, including Eirish Brehon, Jewish Talmudic, Eastern Norse, Berkian Norse, Islamic Fiqh, Anglo-Saxon Common, and others, into a reasonably cohesive whole…

… the complex methods of Hooligan title inheritance, after some refinement, became the method by which titular inheritance was managed in the early and middle eras of the Empire, as the Hooligans already had influences from the Brehon, Alban, and Norse legal codes. Pre-Assembly Hooligan title inheritance was a complex mix of elements from all of these sources, an intricate system that can be described as Absolute Primogeniture mixed with Gaelic Tanistry and Norse Elective Monarchy.

Before the later refinements were introduced, the system worked as follows: Upon the death or incapacitation of the previous title-holder, the designated heir simply assumed the title (absent legal objections from their new subjects or suspicious circumstances), allowing for a smooth transition of power in most circumstances. The main conflict came with selecting the next designated heir. Heirdom was an elected position in Hooligan law, in line with Gaelic Tanistry, based on suitability and worthiness. Heirs, at the time of selection, had to be adults without physical or mental blemish, descended either from the current or a prior title-holder, and currently a member of the clan that they would be inheriting (Hiccup Horrendous Haddock III's selection at the age of seven years was an anomaly, initiated by his father Stoick to reinforce his statement that he would not remarry as a result of his wife's legal death).

Beyond those qualifications, the prospective clan-heir needed to be voted into the position by a majority of the individuals over whom they would rule (typically the members of the clan), with the precise degree of the majority needed depending on the heir's relationship with the current title-holder; a child of the title-holder's spouse needed a simple majority, while the child of a concubine needed six-tenths, and more distant relations needed greater pluralities. Furthermore, the elections were handled in rounds; first the spouse's children would be voted on, one at a time in order of birth, and only if none of them were selected as the clan-heir in two rounds of voting would the elections move to include the concubine's children, and even then, only with the explicit acceptance of the title-holder. From there, if the voting still did not find a suitable candidate, the pool would be expanded to more distant relations, with each voted on in turn until an acceptable candidate was found.

While this system functioned well enough for the Hooligan tribe when it was a thousand people or less, it quickly ran into scaling problems as the clans grew, causing fractures to grow, necessitating the various refinements …

—Origins Of The Grand Thing, Edinburgh Press, 1631

AO3 Chapter Link

~~~

My Original Fiction | Original Fiction Patreon

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brehon Law | The Senchus Mór

The Senchus Mór, is the foundation text of the most sophisticated law tradition in Europe of a thousand years ago. The body of law as a whole is often called “Brehon Law” but is properly called Fenechus, which means “that which relates to the Feine” the free classes that formed the main body of Irish society.

And the authors of the Senchus were

Laeghaire, Core, Dairi, the hardy,

Patrick, Benen,…

View On WordPress

#Brehon Law#Chieftains of Ireland#Christianity#Feine#Fenechus#Nine Pillars#St Patrick#The Celtic Universe#The Senchus Mór#Twelve Constellations

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

top five characters/moments/things from irish mythology you wish had more pop culture traction?

Thank you!

One thing I’m going to say, off the bat, is that I know that my idea of what has pop culture traction is going to be very different than what the general public sees -- When you spend a solid chunk of your life looking....and looking...and looking at pop culture retellings, that’s pretty much all you see, but I’m aware that what might be relatively common in depictions of this stuff might still be relatively obscure to the general public. (Especially if it’s not, say, banshees, selkies, or, God help us all, leprechauns. Even though those are all folklore, I know I’m never going to win that fight.)

1. The Tuatha Dé being dicks in general. Like, with all respect to the Professor, he did possibly the worst possible thing to Irish material (and that’s including when he dissed “Celtic materials” as being like shattered stained glass) that he could have done by sheer accident when he created Lord of the Rings. Because, since that series was published, every single low quality fantasy writer has been trying to shove the Tuatha Dé into Tolkien’s elves (and a specifically bowdlerized version of them.) And the TD are...they’re fascinating to me. I love them very dearly, I’ve been going back to them for years because they’re this group of superhumans who are also petty and spiteful and sometimes rigid in upholding distinctions. They haven’t always forgiven the Milesians for taking Ireland from them, they will do everything they possibly can to screw people over, they are sometimes only loosely tolerant of the mortals (and, on Samhain, for example, they sometimes lose even that loose tolerance.)

Like, I want the Tuatha Dé to be complicated and hypocritical and petty and spiteful while also being capable of being the best of humanity as well while ALSO being distinctly Off. I want Lovecraftian Tuatha Dé who are always just beneath the surface, I want comic relief Tuatha Dé who are still in denial over having lost Ireland and refuse to adapt to the modern world at any cost to truly ridiculous standards, I want the Tuatha Dé to be a big, high stakes family drama/reality show/soap opera with the entirety of Ireland having to deal with the fallout, I want tragic Tuatha Dé who are these kind of living artifacts in a world that’s more or less outgrown them. (I am obviously aware that they have modern worshippers -- I am saying that the TDD are drama queens and will still be mopey after having lost the entire island. Unless you have Brehon law actively being around still, they are still going to be mopey.)

2. Related to that, bruighean tales. This is not a term you hear very often outside of Celticist circles, and part of the reason for that is that these tales often haven’t been translated yet into English (though some of them have been translated from modern Irish), even though they had a wide currency in the folk tradition. What these are is, essentially...a story in which the Fianna are tricked by the Tuatha Dé to go into a magical fort, where the Tuatha Dé proceed to attack them throughout the night with a series of spells, illusions, and the odd monster or two. (The most famous of these is probably Laoi na Con Duibhe -- The Lay of the Black Dog.) Like, I feel like there’s a lot that a modern audience could appreciate about this, from the perspective of horror and the gothic. I think you could do a lot with the claustrophobia and the tension of it, with this group of legendary heroes possibly, for the very first time, being in over their head.

3. The Fir Bolg! It is so ridiculously easy for these guys to get adapted out of depictions of the battle between the Fomoire and the Tuatha Dé, but they’re so important! (Also, more Fir Bolg who are accurate to how they’re presented in Lebor Gabála Érenn -- so many pop culture references, when we do get them, have so much....uncomfortable baggage. Like, I don’t want to say too much because there are some papers coming out on this, and it’s like...I don’t know how much I can say, but it’s just...please can we toss away the idea of them somehow being these primal “primitive” people who are associated with the earth? Can’t we let them be competent and clever and strong settlers of Ireland who established the kingship?) Especially my boy Sreng who is quietly one of the single most fascinating and complex characters in the entirety of the medieval and early modern Irish literary tradition.

4. I firmly believe that we have never gotten enough Bres as a character, which is a little shocking when you consider how important he is to the Tuatha Dé -- so many central figures are related to him (the Morrígan is his aunt), he has a fairly interesting arc in Cath Maige Tuired (which is just a text that...I can never have enough adaptations of), and he gets a relatively large number of appearances across medieval and early modern Ireland. And, like with the TD, I’d really like to see him be done....well. Like, don’t settle for “he’s evil because he’s evil”; I want to see him get a large amount of interiority, I want to see him be complex, I want the audience to sympathize with him even as they realize that if he succeeds...it all goes down. Authors almost seem...intimidated by him, and I think part of it’s that heroes like Lugh are easy, especially when you remove the inconvenient little bits about them that might make them unpalatable. Villains like Bres, though...it’s like they’re having to hold up a mirror. We want to be like Lugh, we want to be that kind of superhuman, hypercompetent master of all crafts who is beloved and is able to conquer all the enemy. In reality, though, I feel like Bres is more...realistic. More human. And that’s why people struggle with him in adaptations, whether they excise him entirely or make him a caricature of himself. People don’t want the reminder of their own flaws.

(Also I believe that he should kiss men.)

(On the mouth.)

(With both parties consenting to it.)

5. Relating to #2, I feel like there’s a thick pseudo-Gothic (pre-Gothic?) vein in a lot of the Irish material that could be a lot of fun to work with. @effervescentdragon once compared Crimson Peak to Togail Briudne Dá Derga, I personally love the incident with the dead men and the Morrígan from the Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn, I was recently rereading the plot summary of the short story “Don’t Wake the Dead” and was reminded of the story of Sín in Aided Muirchertaig meic Erca, the Dead Man in Echtra Nerai, this one description of a bruighean tale...I think it was Eochaid Bhig Dearg, where every single one of the Tuatha Dé is described as having a smile on their faces as they surround the fort....waiting....while the Fianna can only look on in horror and dread whatever nightmares they summon next...Medieval Irish material is often likened to fantasy and, for what it’s worth, I do understand it, especially since all the great fantasy writers were very well in-tune with world mythology and Irish is an Indo European literary tradition (albeit one that, as of the time of it being written down, had intertwined itself tightly with Christianity.) Still, I would really like to see more of that Gothic element being teased out, because a lot of my roots are in the gothic tradition and I would love to combine my two favorite things.

In general, I suppose my tl;dr is that I would like, in general, for more nuance, more complexity, I’d like more writers to have fun with the material and to think outside the box that this stuff gets put into, I’d like to see less bowdlerization, less need to apply a Nationalistic brush to these things that hasn’t really been necessary since the 1930s. (Also, give me more Cath Maige Tuired adaptations.)

It’s funny a lot of the time, when I see, say, arguments about Arthuriana or Greek Mythological adaptations where people will be saying “I HATE when adaptations--” and I’m just kind of in this perpetual state of “What do you mean ‘adaptations?’ Y’all get your favorite works adapted more than one time?” Don’t get me wrong, I can sympathize with seeing your favorite material butchered, but I’ve had to read a LOT of really bad self published novels, Wattpad fiction, and MySpace RPGs from back in the day in order to get *anything* for my favorite characters. And if I was ever really, deeply personally offended by seeing my favorite characters done badly....I think I’d have gone insane at this point. I think people often expect me to be very strict but the truth is that I’ve never had the luxury of being very strict. Our most accurate representation of the material thus far’s been an animated film where the day is partially saved by a spirit cat attacking a Viking warlord. Our second most accurate representation’s been Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla, where there’s an evil cult of human-sacrificing druids in 9th century Ireland that ends up spurring an Irish Inquisition and the 50 foot tall Lia Fáil, which is an alien artifact, exploding into smithereens. And I think that it’s fascinating to see what the public is really interested in and what authors and creatives are putting into their stuff VS the material as we understand it. So, a part of me’s a little sad all the time, but a part of me’s also always interested in seeing how these trends play out.

But, anyway, I hope this answers the question! Thank you again for the ask!

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

which one of you shared that thing about St. Gobnait last year and her possible connection with the Brehon Law tract about beekeeping? I ran my mouth and now someone is asking for sources and I can't find it ugh

0 notes

Text

Irish Private Tour Guides

The history of music in Ireland can be traced back to ten thousand years ago. Musical instruments like trumpets, horns, rattles and pipes have been found in sies as far back as the Bronze Age.

We will explore some of the history of this history and the development of Irish private tour guides and Irish music in a series of posts over this summer. Sign up to our email newsletter and/or follow us on our social media channels to stay in touch with these posts.

Some of these, such as the Loughnashade Horn, can be seen in the National Museum of Ireland. Contemporary musicians such as Simon O’Dwyer have popularised tones from this era are performed today. You can learn more from his website here – and follow him on Instagram here

According to the excellent book ‘Irish Traditional Music’ by Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin the music of Celtic and Early Christian Ireland is elusive and undocumented but it must have existed. Much of what is associated with as ‘Celtic music’ today is born from the romantic notions of ‘Celtic Revival’ of the late 1800’s.

The early centuries of the first millenia were illiterate in Ireland so there is no written record of any of the culture. The earliest record of music is referred to in the ancient Brehon laws of Ireland so it was known by these times. The 8th century Críth Gablach refers to the legal standing of the cruitire or harper and places him above all other musicians in the social pyramid.

Harping has long associations with Ireland and eventually was superseded by pipers as the former was replaced by the later for a variety of reasons. Harpers had a similar standing top the bó-aire or strong farmer in the Gaelic caste system as it existed.

Musicians feature strongly in the early prose sagas, especially the four great collections or cycles – The Mythological, the Ulster, the Fianna and the Kings Cycles. These stories were transmitted orally for centuries and are part and parcel of the creation myths of Irish heritage.

Music focused on the geantraí (music of happiness), goltraí (music of sadness) and suantraí (music of sleep and meditation). There are references to musicians and their instruments in the mythological Battle of Magh Tuireadh fought between the magical Tuatha Dé Danann and the fierce Formorians of the north Atlantic.

The early Christian monks must have had chants and have sung psalms but little evidence exists of these. Musical instruments are evident in much of the art of the Celtic Crosses of the time so we know there was music.

In the medieval period following the Normans arriving in Ireland the bardic tradition was still very strong. The bards worked closely with the poets or file whose eulogies to the lords were recited by reacaire or a reciter. These would have been accompanied by a cruitire (harper) in their performance.

There is no reference at all to dancing in the accounts that survive but we must assume some kind of dancing did occur. The two Irish, or Gaelic words, for dancing rince and damhsa are derived from the English rink and the French danse respectively and they were not introduced until the late sixteenth century.

Earlier reports of dancing appear in the early 15th century in Baltimore, Co. Cork so we know there was some movement on the dancefloor so to speak. The most famous of all irish instruments is ‘Brian Boru’s harp’ which is on display in the Trinity College Dublin library and is dated from 15th century. Join us on our Trinity College Dublin and national Museum tour to explore some of the artefacts mentioned in this piece.

0 notes

Text

St. Patrick’s Day Special: The Defender of Ulster

~ ~

Our fourth Celtic Month piece celebrates St. Patrick’s Day, the national (and international) day of Ireland, on March 17th. Eat some boiled food; play the bodhrán; fight the English; but better yet, study the Irish language. I _promise_ the orthography is less intimidating than it looks.

Before you read what the piece means to me, share what it means to _you_. I’m just the artist; you’re the beholder.

Leave a comment.

~ ~

Irish legend is replete with good stories and epic tales; but I ultimately decided to portray a key moment from the Táin Bó Cúailnge, featuring Cú Chulainn, one of Ireland’s most famous heroes.

In ancient Ireland, Queen Medb (or Maeve) and King Ailill of Connacht realized that they were equal in property except for one thing, namely Ailill’s bull, Finnbhennach, to whom there was only one equal in all of Ireland: Donn Cúailnge, a bull owned by an Ulsterman.

This may sound like a trivial issue; but within the context of ancient Irish society, unequal property in marriage was a very big deal; because Brehon Law, the code which governed Irish society before foreign law was imposed, acknowledged many types of marriages, some of them distinguished by the ratio of the property that the respective parties brought to the marriage. A marriage between a wealthier husband and a poorer wife was a substantially different legal relation than a marriage between an equally wealthy husband and wife.

After negotiations failed (due to a drunken envoy), Queen Medb resolved to attack Ulster and steal the bull; and so the Táin Bó Cúailnge (“Cattle Raid of Cooley”) began. Raising an enormous army and recruiting Fergus mac Róich, an exiled Ulsterman, as a general, Queen Medb and King Ailill advanced upon Ulster.

As a result of an earlier incident, the men of Ulster bore a curse that at their moment of need, they would all suffer labor-pains; and only one warrior was able to stand in Ulster’s defense: Cú Chulainn, a heroic youth, not yet having reached manhood.

Originally named Sétanta, he became known as Cú Chulainn, “Hound of Culann”, after he killed the enormous guard-dog of a man named Culann in self-defense, and agreed to guard Culann’s house until one of the dog’s puppies could be raised to an equally enormous size.

Along with his brother-in-arms Ferdiad, he was trained in the art of battle by the renowned Scottish warrior Scáthach. A precocious student, he defeated her sister Aífe in single combat at that young age, ending a long-ongoing feud that his teacher had been unable to resolve herself.

Thus, as the only beardless youth capable of holding his own in combat, Cú Chulainn stood alone against the armies of Connacht; holding them off at river passes, and invoking single combat to take on their forces one by one; buying time for the men of Ulster to recover from their curse.

In the course of this defense, he had to fight his old friend Ferdiad to the death; and killed him using the Gáe Bulg spear, the one thing Scáthach taught him that she didn’t also teach Ferdiad.

Cú Chulainn could only be defeated after he had broken his “geas” (pronounced “gyas”); a taboo, prophecy, or imperative, upon which one’s power is contingent, which both predicts and brings doom. Cú Chulainn had a geas that his downfall would come if he ever ate dog-meat.

This would come to pass after the Mórrígan, fickle crow-goddess of war and death, in the form of an old crone, offered him dog-meat, which he was obliged by courtesy to accept; ensuring his ruin in repayment of a grudge.

Thus at the hands of the Connacht warriors would come the end of Cú Chulainn’s short, tragic, glorious life.

The golden-haired figure is Queen Medb; the red-haired bearded figure beside her is either King Ailill, or Fergus. Fergus was given the task of leading Medb’s contingent on the battlefield, according to the epic; so we could either be looking at Queen Medb and Fergus at the head of her contingent, or both contingents with the king and queen at their respective heads.

Across, we see the beardless youth, Cú Chulainn, prepared to stand alone against them.

The valley between the foreground-hill and the background-hill plausibly contains a river and a ford, where Cú Chulainn will make one of his one-man stands to single-handedly hold the forces of Connacht at bay.

The crow and the stormclouds at upper left, of course, represent the Mórrígan and the bloodshed to come.

I portrayed each of the warriors as bearing a spear and a shield; because the Irish word for “warrior”, “gaiscíoch”, comes from the words “ga” and “sciath”, “spear” and “shield”. I based the shields on the Kiltubbrid Shield, an ancient alder-wood shield found in a bog in County Leitrim.

#st_patricks_day#ireland#irish#cuchulainn#cu_chulainn#medb#maeve#morrigan#celts#celtic#spring#springholidays#digitalart#vector#mosaic#collage#inkscape

0 notes

Text

Radio EarthRites: The Yearly!

Dear Friends, we recently had a hosting price increase from our station provider, as well as rises in web cost, hosting, music purchases etc. (which all cost)

We have a wonderful group of supporters at this point but would like to see some growth in our support network to cover all the costs that we incur.

We have 2 forms of donations (see the button here at the top of the page: https://gwyllm.com/radio-earthrites/ ) you can subscribe for a monthly plan, or you can make a one-time donation, hopefully once a year!

Radio EarthRites has been on the air pretty much continuously for 18 years, 365days/24 hours a day. We have been increasing our aural diversity, with new shows (Lee’s Real Music Radio Pod) (Earth Riot with Reverend Billy) with shows featuring (Poets Mary Oliver,, Seamus Heaney Allen Ginsberg etc.) and Spoken word, (David Graeber & David Wengrow, Dale Pendell, John Trudell, Noam Chomsky etc. ) We have featured shows about Ancient Celtic Anarchy, Brehon Law, and much more. We will continue to expand the palette of Radio EarthRites, and with increased donations we will be able to start having live shows and more. We are in the process of bringing on guests to host shows weekly & monthly…

This a fundraiser, yes, but it is also a call out to those who want to have a Radio Show on EarthRites.

Please Help Support Radio EarthRites!

Thanks To All Our Supporters, You Know Who You Are!

Gwyllm

0 notes

Text

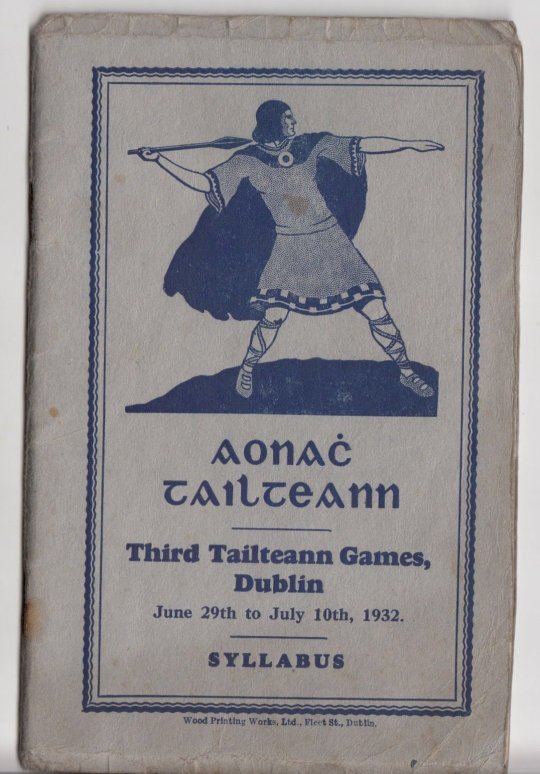

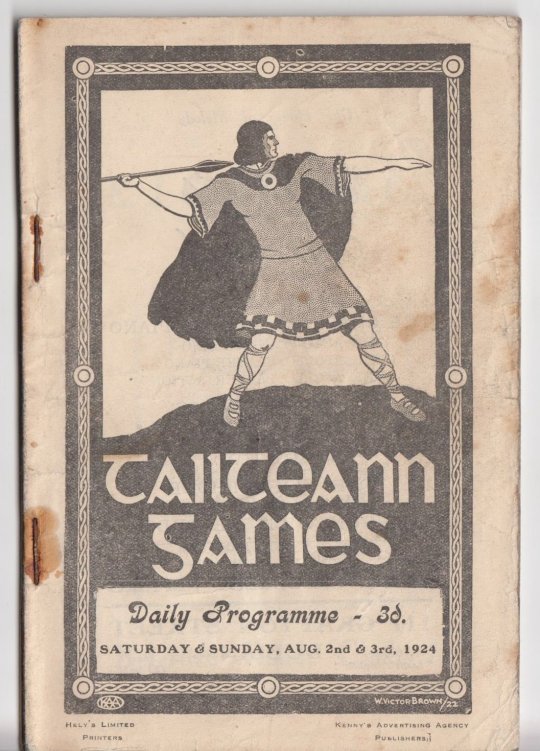

Tailteann Games 1924 & 32 programme covers

"The Tailteann Games, Tailtin Fair, Áenach Tailteann, Aonach Tailteann, Assembly of Talti, Fair of Taltiu or Festival of Taltii were funeral games associated with the semi-legendary history of Pre-Christian Ireland.

There is a complex of ancient earthworks dating to the Iron Age in the area of Teltown where the festival was historically known to be celebrated off and on from medieval times into the modern era.

The games were founded, according to the Book of Invasions, by Lugh Lámhfhada, the Ollamh Érenn (master craftsman or doctor of the sciences), as a mourning ceremony for the death of his foster-mother Tailtiu. Lugh buried Tailtiu underneath a mound in an area that took her name and was later called Tailteann in County Meath.

The event was held during the last fortnight of July and culminated with the celebration of Lughnasadh, or Lammas Eve (1 August). Modern folklore claims that the Tailteann Games started around 1600 BC, with some sources claiming as far back as 829 BC. Promotional literature for the Gaelic Athletic Association revival of the games in 1924 claimed a later date of their foundation in 632 BC. The games were known to have been held between the 6th and 9th centuries AD. The games were held until 1169-1171 AD when they died out after the Norman invasion.

The ancient Aonach had three functions: honoring the dead, proclaiming laws, and funeral games and festivities to entertain. The first function took between one and three days depending on the importance of the deceased. Guests would sing mourning chants called the Guba, after which druids would improvise Cepógs, songs in memory of the dead. The dead would then be burnt on a funeral pyre. The second function would then be carried out during a universal truce by the Ollamh Érenn, giving out laws to the people via bards and druids and culminating in the igniting of another massive fire. The custom of rejoicing after a funeral was then enshrined in the Cuiteach Fuait, games of mental and physical ability.

Games included the long jump, high jump, running, hurling, spear throwing, boxing, contests in swordfighting, archery, wrestling, swimming, and chariot and horse racing. They also included competitions in strategy, singing, dancing and story-telling, along with crafts competitions for goldsmiths, jewellers, weavers and armourers. Along with ensuring a meritocracy, the games would also feature a mass arranged marriage, where couples met for the first time and were given up to a year and a day to divorce on the hills of separation.

In later medieval times, the games were revived and called the Tailten Fair, consisting of contests of strength and skill, horse races, religious celebrations, and a traditional time for couples to contract "Handfasting" trial marriages. "Taillten marriages" were legal up until the 13th century. This trial marriage practice is documented in the fourth and fifth volumes of the Brehon law texts, which are compilations of the opinions and judgements of the Brehon class of Druids (in this case, Irish). The texts as a whole deal with copious detail for the Insular Celts.

From the late nineteenth century, the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) and others in the Gaelic revival contemplated reviving the Tailteann Games. The GAA's 1888 championships of football and of hurling were unfinished owing to the American Invasion Tour, an unsuccessful attempt to raise funds for a revival.

The Second Dáil approved a scheme in 1922, and after a delay caused by the Irish Civil War the first was held in 1924. Open to foreigners of Irish heritage, the first games of 1924 and 1928 attracted some competitors fresh from the Olympics in Paris and Amsterdam. The Games' main backer, minister J. J. Walsh, lost office when Fianna Fáil took power after the 1932 election, and public funding was cut. The 1932 games were on a smaller scale against a background of the Great Depression and the Anglo-Irish Trade War, and no further games were held.

Jack Fitzsimons suggested reviving the Tailteann Games in a 1985 Seanad Éireann debate on tourism in Ireland.

The Rás Tailteann ("Tailteann race") cycling race was founded in 1953 by the National Cycling Association (NCA), in opposition to the Tour of Ireland organised by the rival Cumann Rothaíochta na hÉireann (CRÉ). Cycling Ireland, the merged successor to both the NCA and CRÉ, still organises the Rás Tailteann annually, but it is usually known as "the [sponsor] Rás", or simply "the Rás".

The Irish Secondary Schools Athletic Association organised annual national championships from 1963 under the name "Junior Tailteann Games". Athletics Ireland continues to use the name "Tailteann Games" for its annual schools inter-provincial championships. also independently the tailteann games are an inter-gaeltacht event that includes other activities."

-taken from wikipedia

#ireland#irish history#sports#sports history#pagan#paganism#lughnasadh#celtic#celts#ancient celts#tailtiu#tailteann#1920s#1930s#book art

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝘾𝙚𝙡𝙩𝙞𝙘 𝘾𝙝𝙚𝙖𝙩𝙨𝙝𝙚𝙖𝙩

So let me preface this my pointing out that as far as I’ve been able to gather Celtic culture while holding distinctive characteristics was extremely fluid in terms of cultural practice and politics. I have also taken the liberty of filling in certain gaps in our understanding that strictly speaking we have no way of confirming or understanding the cultural context for. I have listed my primary sources at the bottom of this post and will be reblogging whenever I add new resources or adjustment my headcanons based on new research or sources I find. Our knowledge of the Celts is continually evolving as is my own.

In regards to terms I’m relying largely on Irish and Welsh as they’re the most relavant to the blog and will try to clarify which specific culture I am referring to within the context of my posts.

Politics- Celtic politics were extremely fluid. In broad strokes Kings were elected by council though these elections were rarely peaceful with rival factions fighting until one proves victorious. Because of this the Celtic warrior class was extremely powerful with many kings being able to hold power based solely on bribing and offering monetary and other rewards to the warriors in their service. This is explicitly stated to be how Conchobar of Ulster remains in power in the Ulster Cycle. However it should be noted this practice did not guarantee loyalty. It seems to be be that the King was expected to provide for his warriors as well as his people because of social obligation while the Warrior class in particularly was free to leave and give their services to others if they received another offer or came to disprove of their current Ruler’s actions. This fluidity of loyalty seems to have been accepted and to a degree expected.

Geas/ Geasa and Tynged/ Tynghedau- Perhaps tying into Celtic belief in social obligation a geas/tynged (geasa/ tynghedau are the Irish and Welsh plural forms). In broad strokes it seems to a kind of obligation that one can place on others or themselves as is the case with Cú Chulainn. Irish High Kings could have dozens or more there seems to be a correlation between one’s power/status and one’s number of geasa. I have taken it further by headcanoning that honoring and fulfilling one’s geasa adds to and builds up ones own power as it is frequently shown in Irish lore that violating one’s geasa will result in death or other misfortune.

The Celtic Pantheon- I have posted about my take on Celtic mythology before >HERE< and >HERE< but suffice to say it is as fluid as Celtic culture and politics. But I want to be very adamant that I am not going to favor one group over the other. There has been a long and frankly very ugly history of dismissing Welsh, Irish and Scottish folk beliefs that I want to avoid perpetuating on this blog. NOTE: In terms of interaction I get the impression one was allowed to talk back to one’s gods and even correct their behavior much as warriors were allowed to do with their Kings.

Religious Practices- This is extremely tricky as most of what we’re given is vague and described by non- Celtic sources so most of what I’m about to describe is strictly headcanon based. All pools and bodies of water are believed to be doors to the Otherworld. It is therefor customary for Celts to provide an offering of some kind to bribe or get a deities attention. (Lancelot himself will use this as a means of communicating with his mother.) Birds are also seen as messengers between the human and Otherworld with sacrifices sometimes made to lure birds to a sites and then carry the prayers offered by the druids and supplicants back to the Gods.

Heads- While an abundance of writing and other evidence exists that the Celts had some kind of Cult surrounding the head/brain we’re not particularly sure why. I’ve interpreted it that the Celts believed one’s soul/power resided in the head and that by taking and preserving the head or brain one was adding to one’s own as well as keeping your enemy from entering the Otherworld and reincarnating.

Children- I am admittedly sorry for putting this under the rather graphic bullet point above. But the Celts were not like their neighbors Romans or Greeks and did not view their children as disposable. One was required to look after one’s children, the elderly and disabled. I can think of no better example of this than Amergin mac Eccit from the Ulster cycle who was unable to physically care for himself until his teens with his father Eccit going to extraordinary lengths to protect his son who is later described as a wise poet and warrior despite his disabilities. This is also why Lancelot insists on making Galahad his heir even if he struggles to form a bond with him as it is culturally unacceptable to him to not provide for him on some level. Children were also only considered illegitimate if no one claimed to be their father.

Relationships/ Sexuality/ Gender Roles- This is likely the most difficult to headcanon and has required the biggest leaps on my part. But it seems to be that the Celts were comfortable and open with queer relationships an taking lovers outside of marriage with the upper classes in particular engaging in seemingly polyamorous unions. All sexes could become Druids or Warriors or even rule in their own right. Boudicca and Medb in the Ulster cycle are excellent examples of this.

Sources

Cunliffe, Barry. The Ancient Celts. Oxford University Press, 1997.

Koch, John T., and John Carey, editors. The Celtic Heroic Age: Literary Sources for Ancient Celtic Europe & Early Ireland & Wales. Celtic Studies Publications, 2003.

Ginnell, Laurence. Brehon Laws: A Legal Handbook (3rd Ed.).

ANWYL, EDWARD. CELTIC RELIGION. BLURB, 1906.

Eickhoff, Randy Lee. The Red Branch Tales. Forge, 2004.

MacCullough, J. A. The Religion of the Ancient Celts. T & T Clark, 1911.

Paxton, Jennifer. “The Celtic World.” The Great Courses. The Celtic World, 2018.

Andrews, Elizabeth. Ulster Folklore. Norwood Editions, 1975.

Arnold, Matthew. On the Study of Celtic Literature, and, On Translating Homer. Macmillan, 1902.

Leahy, Arthur Herbert. Heroic Romances of Ireland. D. Nutt, 1905.

O'Rahilly, Cecile. Táin bó Cúalnge: From the Book of Leinster. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 2004.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Rebuttal of “Lesson 6: The Structure of Early Gaelic Society”

This is part 6 of my 20-part manifesto on why druids should do some research for once. You can find the master-post here.

This is a long post, so the actual rebuttal is under the cut! Each number in parenthesis (#) corresponds to a footnote formatted in the Chicago manual of style located in the block quote at the end of the post, any reference to the Brehon laws is linked within the text and will not have a footnote!

Hey hey hey welcome back! It’s been a few months, and I’m refreshed and am once again ready to tear into druidic bullshit. Today we’re continuing our look at Robin Herne’s “lessons,” this particular lesson can be found here.

From the very beginning of this “lesson” I’m sensing a problem with Herne’s writing that I’ve seen and spoken on before, which is the concept of a pan-Celtic religion. Herne’s lesson may focus on Ireland, but that’s only because he feels as though it’s “harder” to talk about Wales.... a nation with a very different history and a different religion than Ireland..... but they’re both Celtic so whatever right? For any newbies here, there was no Pan-Celtic religion. I mention this in Part 1 of this series.

From there it only gets worse really. For starters, the Romans never conquered Ireland, the nation whose history is supposed to be the focus of this lesson. Beyond that- the Romans used existing British oppida as the urban centers of the tribal system that was established under their rule, to claim that pre-Roman Britain was made up only of villages when archaeologists can’t accurately determine the populations of the oppida is ridiculous. What the Romans did was establish the first cities that were not located in the South East of England. Herne also has this weird focus on Ireland and Britain being “rural” as though most cultures weren’t largely rural- and honestly the focus on distancing these cultures from anything urban is a HUGE red flag if you know the history of paganism and Celtic Twilight, bad show all around. And of course Herne doesn’t cite any sources so for all I know he’s pulling this out of his ass. All in all it seems like Herne is falling to the classic pitfall of circle jerking to Rome, maybe if he could get off Rome’s dick for a few minutes we might actually learn something.

I question whether Herne has ever actually read the Brehon laws, or if he understands that there were similarities between the laws of many medieval societies, even those that didn’t share a “Celtic” label. I genuinely have no idea what “change” he’s referring to that would be a gradual process considering the continental Celts and the Gaels were different cultures, and the laws in question existed at different times, and also the laws he references for the continental Celts were only “mentioned” by classical authors, who if you haven’t read my other rebuttals are notoriously unreliable narrators.

I question the choice to say “Think of the cenn as rather like the head of a Mafia clan! “ and particularly to end it with an exclamation point. The cenn, is the head of the family, and thus the family’s legal representative in court. This was not a cultural practice unique to Ireland, similar practices are shown to exist throughout Europe during this time. And in no way is a patriarch (or occasionally a matriarch) who protects the family’s interests and revokes legal agreements made without their consent the same thing as a mafia boss. This isn’t a crime syndicate, it’s a judicial system that protects the different families within the tribe and in theory was meant to ensure that contractual decisions were made with the consent of the family.

Beyond this to describe the social structure of early Ireland as a “caste system” is... stretching it- movement from one class to another was not uncommon, and more things factored into one’s status in Irish society than simply the situation of one’s birth. Beyond that, this system is more easily broken down into six groups than into two, and Herne would know that if he’d actually read the Brehon laws. Rather than just splitting society into “the blessed ones” and “ordinary people” the Brehon laws organize it into kings of various grades, professional classes, flaiths (a sort of official nobility), freemen possessing property, freemen who possess no or very little property, and the non-free classes. And joint ownership of property could qualify a selected joint-owner to become a noble, this is very much not the rigid system Herne would want you to believe it is.

Herne’s discussion of the Lia Fail while simplified does hold up. In the lore we see the process described by Herne for choosing the high king of Ireland, it’s described clearly in The Destruction of Dá Derga’s Hostel. And I will admit, I’m with Herne up to a point in his discussion of the concept of lanamnas, there’s clearly a fair amount of research he needs to do into medieval history to truly understand the relationships he’s describing, but he’s not necessary wrong, so I’ll let it slide, these are meant to be introductory lessons after all.

However. Herne makes some... interesting claims in regards to divinity. Herne makes the correct statement that “Each partner in lanamain must recognise that they have a duty to give certain things to the other person, but also a duty to allow that person to give back to them ~ there is no honour in emasculating someone, nor in allowing yourself to be rendered servile.” This is correct, we see this very same principle in the two sided nature of the virtue of hospitality, we’re called to be both good hosts and good guests. But then Herne goes onto say “This applies as much to the Gods as to other humans. Hosting a ritual for a god may be seen as fulfilling the coinmed, but there should also be expectation back of the deity. If your life is barren, then maybe you need a better head to guide you (either that, or you‘re not fulfilling your duties to them).” Ignoring the fact that Herne has all but called the gods parasites if they don't attend rituals we host for them voluntarily (something we should be doing anyway, and without the expectation that they’ll show up)- this argument rests on the assumption that we can understand the divine and how they interact with us enough to judge whether or not we need a "better head" to guide us, which I think anyone who’s actually had an encounter with the divine or felt their presence can tell you is bullshit. They’re divine for a reason, they’ve existed for thousands of years, we’re just a blip on their radar, it is not up to us to judge whether or not we need a “better head to guide us” or if we’re giving enough, the gods decide that.

For everyone who had “baseless claims about the roles of historical druids” on their BINGO cards you may now cross that off. Herne falls into the typical pattern of repeating the “druids were the precursor the Catholic church” story fabricated by 16th century Germans for political clout. Don’t be like Herne, read a goddamn book, I have recommendations, feel free to dm me or shoot me an ask if you’d like them.

And last but not least, I would like to remind everyone that the “every family/tribe has their own tartan that differentiates them” is a largely 19th century creation with scant pre-Victorian basis.

That’s all for today! If you want more reading on any of the topics mentioned in this post feel free to shoot me an ask or a message and I’ll provide you with a reading list!

#my writing#research musings#anti-druidic rhetoric#anti druidic rhetoric#aka facts#20-part manifesto

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brehon Law | Clans and Social Classes

Irish society, up through the Iron Age, was based on the family unit. The family traditionally consisted of living parents and their children. The next larger unit came to be known as the Sept, which consisted of a closely related group of families such as the families of children of one set of parents and normally bore the same surname. The Clan (from clann meaning children) was the next larger…

View On WordPress

#Ancient Laws of Ireland: Uraicect Becc and Certain Other Selected Brehon Law Tracts#Clans and Social Classes#Family unit#History#History of Ireland#Ireland#Irish Brehon Law#Irish Law#Iron Age#William Maunsell Hennessy

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

hallo! i was looking through your pinned list of recommended sources, but i couldn’t find anything that related to what i needed- would you, by any chance, know of any good sources to read about old irish ranks, societal systems, etc? (like fíle’s and whatnot)

i can’t find any at all, but i’m probably looking in the wrong places :’)

SO sorry I just got to this! For some reason, Tumblr didn't let me know I got this. So, the reason why this isn't in my source list is that the source list is compiled from what I know as a mythographer on this material, and it is specifically designed to focus on mythological material, while what you're looking at is, specifically, legal material. Which doesn't mean I won't help! (God knows I never need the excuse to run my mouth off), BUT it means that I'm also slightly out of my depth, even though I did ask a friend who does legal stuff to weigh in. For a starter I'd go with Fergus Kelly, A Guide To Early Irish Law -- you won't necessarily be reading it for what he is saying, but for his references at the back. Likewise, pick up his Early Irish Farming. You won't THINK there's anything in there useful to what you're doing, but...I can almost guarantee there is. It has. Everything.

-- Liam Breatnach, Uraicecht na Ríar (on the poetic grades)

-- Patrick Sims Williams and Erich Poppe, "medieval Irish literary theory and criticism)

-- Myles Dillon, Lebor na Cert (the Book of Rights, deals mainly with kings.)

--Kevin Murray (editor) Lebor na Cert: Reassessments

-- Bart Jaski, Early Irish Kingship and Succession (kingship)

-- Riita Latvio, "Status and Exchange in Early Irish Laws"

-- Robin Chapman Stacey, "Ancient Irish law revisited: rereading the laws of status and franchise"

-- Nerys Patterson, Cattle Lords and Clansmen (thank you to @wickedlittlecritta for reminding me!) Honestly...if you ever decide to dive into the broader world of law...anything by Patterson, I really like her work on gender.

ANYTHING on Críth Gablach, which is a status tract. I won't throw the Binchy edition at you, unless you know Old Irish, I'll toss the Eoin MacNeill version here.

-- T. M. Charles-Edwards, “Críth Gablach and the law of status”

-- Ibid, “A contract between king and people in early medieval Ireland? Críth gablach on kingship”

--Ibid, "Honour and Status in some Irish and Welsh prose tales"

-- Marilyn Gerriets, “Economy and society. Clientship according to the Irish laws”

-- Neil McLeod, “Interpreting early Irish law: status and currency (part 1 + 2)

Unfortunately, some status tracts, like the Uraicecht Becc, have never been fully translated, but they have been written about:

-- P. L. Henry, “A note on the Brehon law tracts of procedure and status, Cóic conara fugill and Uraicecht becc”

-- Douglas MacLean, "The Status of the Sculptor in Old Irish Law and the Evidence of the Crosses"

This looks almost like too much and not enough at the same time. I want it on the record that...in medieval Ireland, status was EVERYTHING. Down to what food you ate as a fosterling. Everyone had a status, everything had a status, and that status was simultaneously fixed but also allowed for some degree of social stability (you could, if you earned enough money, move up from being a commoner, but you would never achieve the status as a fully born noble, your CHILDREN would inherit that rank instead.) We say that about every society, to the point it's a cliche, but in this one in particular, everything was decided on the status you had, who your family were, who you married, etc., so it isn't an easy question. It'd be a bit like asking me "Well, how did people live in medieval Ireland?" People have based their entire careers on this sort of thing. But I hope that at the very least....it's a start.

If you have any trouble getting ahold of things, don't hesitate to let me know! Happy hunting!

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Night Before The Pursuit

This sonnet arises from my research in historical Irish hospitality, and the way in which it was codified in law, contrasted against the story of Diarmuid & Gráinne, the Tóraíocht, "the pursuit". It was written in about 15 minutes for a competition, so it's far from my best, but I kind of like the clunkiness of it.

The duties of the host are manifold;

To meet, to provide, to comfort, to hold.

The duties of the guest, it’s clear, less so;

To eat, to drink, and finally, to go.

The ancient laws of Ireland bind them both

Where written word sets forth the bread and broth

And though the Brehon keep those laws no more

Each Irish home still has them at its core.

But how do we address these duties when

Our feelings cloud the written word, and then

The host and guest become no longer such

And other urgent roles take form, so much

We go from Brehon Law to Celtic Tale;

We run, pursued, on horse, on foot and sail.

3 notes

·

View notes