VIDEO GAME OPINIONS HAND-CRAFTED FROM SLABS OF FINE MAHOGANY

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds Needs A God

No multiplayer game gets to live in a void for long. No matter how hard you may try to bleed yourself of troublesome concepts like context, or backstory, the reality is that people like to speculate. People like to tell stories. Doesn’t matter how goofy or outlandish; the creeping tendrils of narrative eventually wrap around the foundations of even the purest, most context-free experiences. Why are we bombing these crates? Why are we stealing that flag? Why are we fighting? Why are we here?

Somebody will come up with an answer. It’s the human thing to do.

But for PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds, it feels like that answer has yet to come. One hundred players parachute onto a deserted island, where the average density of firearms per square meter exceeds even the most deranged fanatical NRA wet dream, and a slowly constricting hemisphere of crackling blue energy forces them to mercilessly gun each other down until only one is left standing. It’s an absurd, nightmarish premise; a theoretical scenario seemingly engineered to turn people into rabid beasts, fighting tooth and nail merely for the privilege of living a few minutes longer. Who would orchestrate such a competition, and for what purpose? Is it an experiment? A ritual? A blood sport? Is some Silicon Valley bazillionaire sitting in a darkened room somewhere, surrounded by monitors, cranking his sad rubbery hog to every rifle crack and arterial splatter? Nobody seems to know, or care.

Ordinarily, I wouldn’t either; PUBG is fun enough without framing. And yet, tonight’s winds bring an uneasy chill, carrying whispers of restlessness, indignance and fury. You feel it, don’t you? There’s a philosophical schism in how we approach Pubguh—the very concept of ‘battle royale’, even—and the hairline fractures are beginning to show. Players whine and gnash their teeth at the red zone, esports organisers desperately attempt to harness the format for views, and the proverbial chicken dinner seems to attain a more and more mythical, trophy-like status by the day; a reference to back-alley gambling now ironically viewed as a badge of ultimate prowess. This isn’t a healthy relationship. This isn’t a healthy attitude.

What Plunkbat needs, friends, is a god.

Well, okay, not necessarily a god god. Divine power is optional. I’m not asking Brendan Greene to start wearing a white toga and chiselling his patch notes into stone tablets, as much as it would set an entertaining precedent. The job requirements are flexible: I’m simply asking for someone vengeful and capricious, with unfathomable intentions, inscrutable thoughts, and—at least within the bounds of the playable space—immense, unassailable power. Like any god, you need not supply scientific proof of their presence; you merely have to attribute sufficient existing phenomena to them, and change people’s collective perception of the world. Ooh, got’em.

See, battle royale games represent an important shift to me. I’m a competitive person by nature. It’s etched into my mind, irreversibly chiseled by years of test scores and parental praise and all the other ego-stroking bullshit that you were subjected to if you were a certain kind of ‘gifted’ child. “You’re the best. You should be the best. You should be winning. Why aren’t you winning, what the heck is wrong with you?” So it bleeds over, into hobbies, work, and of course, online shooters, in which I regularly demonstrate that I have an innate… whatever the opposite of aptitude is. I react slowly, I zone out, I bean myself on the head with my own grenades, and if you exert the slightest bit of pressure, I’ll empty half the magazine into a wall and drop my weapon through a gap in the floorboards. I’m not good, and yet some unreachable, fundamental part of my conscious will never be satisfied with that knowledge.

You would think, then, that Pubby-G would only serve to exacerbate this mindset. And yet, in a world of delicately tuned esports that are built from the ground up to be pure, unfiltered tests of skill, it feels like the only game to grant a genuine absolution of responsibility; a kind of freeing fatalism. There’s a sense in a lot of classic multiplayer experiences—like, say, Counter-Strike—that every outcome is more or less deterministic; a product of a series of controlled variables and actions. With every failure comes the overwhelming impression that it could have been averted, given enough competence, foresight, and concentrated guarana. By contrast, a porridgey cocktail of chaos flows through the veins of battle royales, surrounding you with factors that are not only impossible to influence, but—in many cases—impossible to know at all. You are swept up by the gusts of a hundred butterflies’ wings, tossed to and fro by the whims of the random number generator, bombarded with unavoidable risks and squeezed into unmanageable situations. It’s easier to go with the flow, accept that at any given moment you may have your head unceremoniously taken off—by somebody lying flat on a distant hill, or hiding behind one of the game’s ten thousand trees, or concealed in a shrub on the far side of the Moon—and concentrate on all the minute actions you can make to ever-so-slightly nudge the odds in your favour.

But it’s not always clear that this is the reality of Puhburger. With its vast scale and often languid pacing, encounters can feel like isolated incidents, detached from the cascading series of events that led up to them, despite being anything but. Anyone can parse the map for circles of safety and non-safety, and understand that their arbitrary placement gives certain players an advantage; it’s less apparent that the figure in that upstairs window might have had their sights trained on the area, or seen you first, shot first, picked up a better weapon, obtained a better vantage point, or some other action, because of a dizzying permutation of astral alignments that neither of you could even begin to grasp. So we get futile attempts to establish a level playing field, find meaning in accomplishment, divine fair elements from unfair, and generally make things needlessly stressful for everybody involved. Except the infuriatingly smug yours truly, of course.

How do you make that clear, though? How do you concisely impress upon people that their fate is almost entirely out of their hands, in such a way that they adopt an attitude of acceptance? Blaming the roll of the dice doesn’t come to mind as swiftly when you never see them rattling around, nor the way their innumerable ripples propagate across the map. Furthermore, as current events have taught us all too well, it’s a lot easier to ascribe fault to individuals than to an invisible, fundamentally hostile system. So what do you do?

You give the system a name. And, if you can, a face.

Allow me to momentarily slam us into reverse. When Valve released Left 4 Dead way back in 2008 (oh god, it’s going to be ten years old this year?) they made quite a song and dance about the game’s AI Director; an invisible, unknowable entity that would dynamically dole out items and zombies in a manner consistent with the tenets of dramatic tension, ensuring players were subjected to a “fast-paced, but not overwhelming, Hollywood horror movie”. While the opacity of the AI Director’s machinations always made me a tad sceptical of its mechanical effectiveness, giving people a name to pin the blame for all their earthly woes on was a masterstroke. Notorious video game jokesman Yahtzee Croshaw—the one with the hat and that trendy 00s cynicism, remember?—reported that he once witnessed someone praying to the AI Director, and I bet you all the pipe bombs in the world that players’ personification of it didn’t stop there. Short of making a catastrophic error, I never saw anyone get chewed out for not pulling their weight, and when tones got heated—as they inevitably do, when you’re throwing yourself against the frigid slopes of the higher difficulties—they were directed in the vague direction of the director: for its expectations, for its lack of pity, for being unfair. Awareness of our lurking orchestrator changed our perception of the experience, even though we couldn’t entirely prove it wasn’t just somebody sitting in a black box, disinterestedly flipping a coin over and over.

So, why not do the same for a game that does? Put a face on the system that holds a fundamental grip on who lives and who dies. You don’t need to change a thing under the hood; you need only introduce the vague implication that the evolving state of the battlefield is a consequence of a thinking, feeling, mysterious overseer. A bloodthirsty oligarch watching from their lavish observation zeppelin, a dystopian TV network broadcasting a deadly future sport, an amoral team of government agents sealed away in a bunker control room, an inexplicably sapient Shiba playing with a selection of levers, or indeed, a literal deity. People will take the faintest contextual cues and run amok with them, ascribing everything they can to the will of the one who set this conflict in motion: item drops, circle position, all the way down to the subtle spread of their bullets as they sail through the air. Yeah, maybe it’ll start off as a running joke; an ironic indulgence, the “thanks Obama” of Puddlebounds. But that’s the thing about ironic behaviour: get enough people doing it at once, and you’ll cultivate sincere participants without even realising it. We will learn to absolve ourselves of responsibility, and engage in the unhinged pandemonium of battle royale with the mentality that befits it.

There’s just one problem: you need to be able to keep a secret.

I’m still working on that part.

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quake, Player-Designer Dialogue, and the Spectre of the Dungeon Master

Oof. It’s hard to think of a faux pas in video games that radiates more second-hand embarrassment than an author’s self-insert. Whether it’s David Cage patronisingly telling you that learning to operate a doorknob is ‘cool’, Solid Snake opening up the back of a covered truck and hissing “Mr Kojima!?”, or… well, basically anything Lord British has ever done, there’s just something a little distasteful about dropping yourself into a virtual world that’s ostensibly made for the entertainment of somebody else. What kind of monument to your ego do you think this is? How many other people were you reliant on to make your virtual representation walk and talk, just so it could be the face of their work? Take your auteur theory and go sit in the bloody corner.

It’s a sorry state of affairs. Which is a shame, frankly, because video games—as a medium that is, almost by definition, interactive in some way or another—are quite possibly the most effective format for facilitating a dialogue between their own creator and a consumer, short of putting the kettle on and getting them both to sit down for chit-chat. There’s a world of potential in the simple, genre-agnostic quality of being able to take in a player’s input, interpret meaning from it, and encode some conditional response, but in the interests of preserving the fourth wall, those responses have to be rerouted through diegetic detours; embedded in lore, or environments, or events. For most video games, the opportunity to engage directly with a designer, speaking as themselves, is enough to jolt the player out of the experience, out of their chair, and across the room.

But there are ways to establish that kind of direct, one-to-one engagement, and surprisingly, they’re not all confined to the fringe realm of masturbatory meta-plots either. There are ways for a designer to slip through the membrane and reach out to the player without making their presence blatant; without assuming something so crude as an avatar. We can have dialogues, not by sitting down with a polygonal man in a crinkled button-down shirt and picking lines from a menu, but by stringing together actions and reactions in a controlled context, where their meaning takes on an unavoidably personal nature.

And what better example could there be than Quake?

Yes, Quake. It’s hard to believe, but as much as id Software became known for their fixation on bleeding-edge engine tech and no-frills, fast-paced, first-person shooters, their ambitions during development often strayed into strange and exotic territories. Doom’s initial design document (the famous ‘Doom Bible’) called for a far heavier narrative focus with a proper cast of characters—some of which would live on, after a fashion, in Rise of the Triad—and Quake proved to be even more amorphous. Long before id Software had risen to its notorious station, ‘Quake’ was the name of a fictional character envisioned by John Carmack: a walking power-fantasy; a Thor-like figure with a gargantuan hammer, a ring of regeneration and the power to sling thunderbolts. Later, plans for a game began to coalesce around Quake; plans that envisioned RPG elements, medieval environments, meaty hammer-focused violence, and of course, the fully 3D engine, complete with rudimentary physics. For a mid-nineties id, with a staff roster you could still cram into a panel van, this turned out to be a far bigger bite than anyone was willing to chew, and the game was stripped all the way down to its eventual status as little more than an evolution of the Doom formula. But what lingering fragments of ideas were left in, when that vision was hacked down to size? The name, the lightning gun, the magical artefacts, the leering Death Knights, the endless succession of pseudo-medieval labyrinths? Or something more intangible, more abstract?

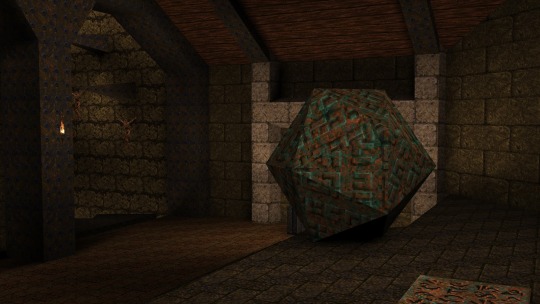

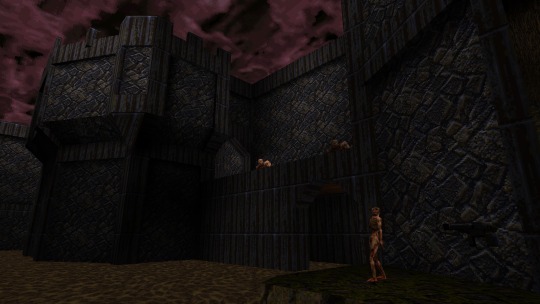

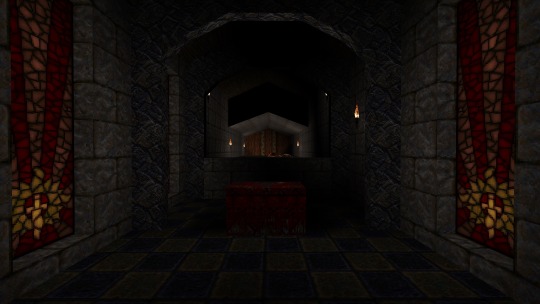

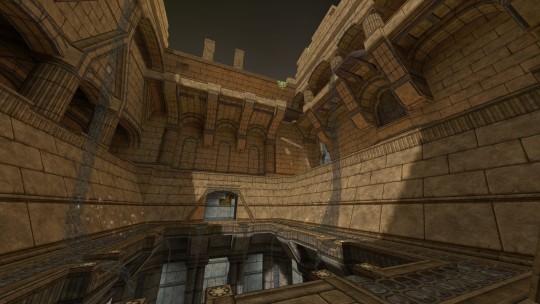

Something’s there. From the moment you first step out of the slipgate, Quake is a lonely game. Loneliness characterised not by quiet and isolation, but by a sense that the entire concept of communication is simply alien to this world; that the only language it knows is ceaseless violence. There are no allies, no bystanders, and it’s impossible to imagine the enemies exchanging so much as a sullen, grumbled greeting with one another, let alone with you. And yet, Quake speaks. Like many of its peers from the time, it makes liberal use of on-screen messages during gameplay. Centre-aligned and heralded by little more than a subtle ‘buh-boop’, they appear at first to be little more than design duct tape, hastily applied to the parts of the game where progressing requires more than just splattering the stonework with monster meat. “This door is opened elsewhere...” the game may announce, its ellipsis tantalising you with the thought of ancient mechanisms, elaborate and unseen, waiting to be set in motion. In a pinch it may tell you “An unholy altar! Shoot it repeatedly!”, or cryptically hint that “A secret cave has opened...”. But who, or what, is the source of these private, direct communications? What Stygian pit are they issuing forth from? These are not the dry status reports of a machine; these are messages with subtle tone, and sometimes apparent motives, nudging you here and there, helping and hindering and sometimes outright misleading. Yet the context of Quake also precludes the existence of a character to attribute them to. So, what’s the source?

You could be forgiven for thinking I’m intentionally reading too far into an innocuous non-feature here. A few lines of ambiguously attributed text is hardly likely to be some nuanced design flourish. But there’s something odd going on with Quake’s levels besides the occasional Gothic telegram. They… don’t really justify themselves, you know? They’re not ‘places’ so much as abstract mazes, loosely chained together via the mechanism of teleporters. Many have names that give some hint to what they are as a whole—“The Slipgate Complex” is a complex with a Slipgate in it, “The Tower of Despair” is a tower full of, uh, despair—but there’s little-to-no earthly logic shaping their internal structures and events. They’re purgatorial, otherworldly mazes, floating in a context-free ether, piercing the boiling purple sky with twisted spires. The Ebon Fortress may have ramparts, but it has no noblemen to coddle, no peasants to house, no cesspit to muck out; nothing that suggests its layout was built for any conceivable purpose besides challenging and confounding a lone axe-wielding boomstick-toting maniac. What is this place for? It’s not ‘for’ anything; it’s a level. You can’t imagine anyone living or working there, even if they were eight feet tall and had rusty chainsaws for hands.

This lack of context in Quake’s environments—a lack of implied history to its crumbling brickwork, a lack of implied purpose to its grimy locales—is easy to read as merely shallow. Actually, let’s not pretend otherwise: it is shallow. That’s exactly what it is. But neglecting to hint at the existence of some bigger picture has fortuitous side-effects. Much like Doom, Quake’s environments are dynamic, as id was understandably eager to show off: laced with traps and ambushes, grinding stone, bubbling lava and hidden switches; acting and reacting in sway with the player. Quake’s levels can reward, punish, intimidate, trick and relieve; in short, they provoke emotional responses. In a contextual void like this, though, where does that emotional response get directed? Who, or what, do you curse when the doors are barred and the ceiling begins to lower? To whom do you owe gratitude when a wall slides open, revealing a row of much-needed medkits? The antagonist? Puh-lease. Quake is a non-character in Quake; a footnote, a vestigial stub, an entity you could forget existed entirely if you lost the manual behind the couch.

Forgive me. To make sense of this tangled fistful of threads, there’s something else you need to know about id Software. See, of the numerous passions that bound them together from their earliest days, one of the biggest was Dungeons & Dragons. When they were toiling away in Softdisk’s miserable offices, D&D helped id’s founders connect; when they were cranking out Commander Keen sequels in a lakeside house, the contiguous adventures of their party were a frequent nocturnal pursuit, powered by John Carmack’s extensive and somewhat obsessive world-building. Carmack was the Dungeon Master, naturally, and it’s his role—particularly how it relates to the players—that intrigues me most of all.

A Dungeon Master. That’s one of those things that tabletop games have always had over us miserable digital loners, isn’t it? Putting the responsibility of running an experience on a real-life person—in particular, the same person who may have designed the experience in the first place—enables exactly the kind of intimate creator-consumer relationship that I previously lamented the lack of. The Dungeon Master’s role is not just that of a machine, a mouthpiece for the rulebook; they’re a real, living person, tasked with leading their group throughout a session. Their role exists in a contextual in-between space, external to the world and yet inextricably tied up with everything in it. Sometimes that manifests as making adjustments for the sake of keeping things interesting, deploying favouritism, punishing players who step out of line or whipping them into shape. A conversation is occurring, driven by actions and reactions, where people on both sides of the cardboard barrier learn about each others’ tastes and attitudes—even if nobody ever breaks character.

Now look, I’m not going to pretend I know the ins and outs of Quake’s development process. I don’t have the necessary clout to corner John Romero at a party and pester him with a bunch of loaded questions. For all I know, id’s tabletop fantasies had no more influence on their game’s final form than the brand of pizza they ordered every other night. But I believe Quake, too, has the spectre of a Dungeon Master; a figure external to the world, manipulating events through it, engaged in an indirect dialogue with the player who challenges them. This conduit from designer to player, resonating with force and feedback alike, exists in every game to some degree or another, but Quake—with its near-complete contextual vacuum, forceful level design and habit of addressing you directly—allows a subtle personality, a faint identity, to infuse the creator’s end. The player acts, and the world responds in kind, but the world doesn’t have a reason to do anything, besides following the hopefully not-too-sadistic whim of its architect. Whether it’s shooting a suspicious texture to reveal a hidden cache, being lured into a trap with the promise of much-needed health, or being slyly informed that “The window is key to a secret”, Quake provides numerous opportunities for the gaming equivalent of a passing nod and a moment of eye contact. I see you, motherfucker. I see what you did there.

And no, it’s not ideal for facilitating dialogue. It’s no match for the polygonal man in a button-down shirt. What Quake offers is less immersion-shattering: the chance for a designer to subtly infuse a world with their personality, their biases, even their words, without obliterating the fourth wall or losing attribution. Like the Dungeon Master steering the course of events, Quake’s particular set of circumstances lets the designer occupy the contextual in-between space where they can openly exert their will while maintaining the shared fantasy. What are their moods, their goals, their attitudes to the player? Are they spiteful? Generous? Capricious? How do they react—be it with speech, or with actions—to mistakes, to success, to exploration, to attempts to cheat and circumvent? The power is in their hands, and their only binding obligation is to entertain.

It’s not quite someone’s self-insert. But it might tell you more about them.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

dm_lister is out (ha ha whoops forgot to mention)

Hey, did you know I also make things? It’s true! I made this thing, right here:

Map description:

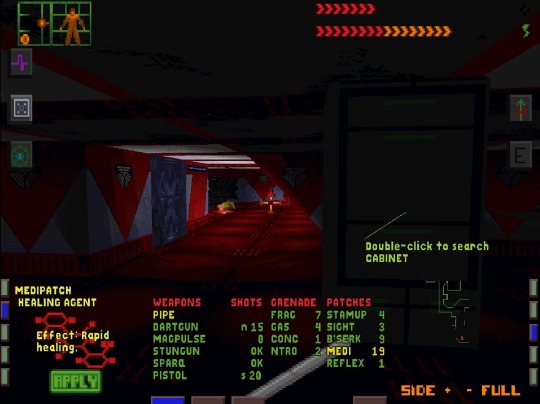

"No. No, it's not Cloister. It's me, it's Lister! It's Lister the Stupid!" -- Dave Lister, Red Dwarf Series I Episode IV, "Waiting for God" A remake/rebuild/re-whatever of Cloister, a deathmatch map created by the Half-Life writer, Marc Laidlaw. Cloister was never officially released but was retrieved (partially) from the leaked WC map pack, albeit not in an entirely playable state. As a self-acknowledged maker of monumentally poor decisions, I set about reconstructing the map and bringing it up to a higher standard of aesthetic quality, while preserving its play space to as reasonable an extent as possible. Marc seems understandably bemused as to why I'd pour my time into this, but as far as I can tell, the project has his approval--or at least, his world-weary tolerance. Play is likely to be ideal with between 2 and 8 players, as the map is somewhat cramped and there aren't many safe places to spawn. All weapons make an appearance except the egon (because I'm a bitter soul). I've made an effort to minimize changes to the layout, but item spawns were largely just chosen by me based on whatever I felt would be best. (The r_speeds are, of course, abysmal. I sort of went into this project knowing that I wouldn't be able to restrain myself. It's 2017 anyway, come on now)

Download link

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brigador and the Art of Sky-High Storytelling

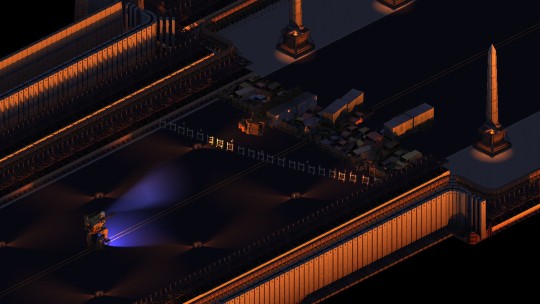

“GREAT LEADER IS DEAD. SOLO NOBRE MUST FALL.”

The first spoken words of Brigador, synthesised through a muffled speaker and emblazoned on-screen in bold, unadorned, searing red letters, are all the exposition it strictly needs: it is a time of great upheaval on the frontier colony of Solo Nobre, and you, with your ten-ton armoured mercenary mech, are here to do some heaving. Narrative and lore are strictly confined to downtime; to dense slabs of text filed neatly away in the codex, to be optionally purchased and read at one’s leisure. There’s no place in the combat for direct storytelling, between the rumbling of diesel engines and the whip-crack of electromagnetic slugs, and even if there was, it’d be little more than poorly embellished justifications for “go here, destroy those buildings, go there, destroy those units, leave.”

But to dismiss Brigador as pure context-free action is to fail to recognise how it speaks. When we think of environmental storytelling, we think small. We think of unconvincing graffiti on crumbling walls, half-finished meals, abandoned chess boards, desks piled high with papers, carefully-placed bookmarks, downed tools and barricaded doors. We think of skeletons in compromising poses, and trails of blood that laugh in the face of a bucket of bleach. Personal stories are made when people leave personal imprints, as taken to extremes by, say, Fullbright’s shtick of giving you a whole night to rummage through your family’s household belongings unfettered. For this very reason, the most popular examples of experiences with environmental storytelling are largely those that enable you to get up close and pick it apart, preferably without being too rushed. There’s a special kind of intimacy in it, almost voyeuristic, as you sift through the documents of a person who would certainly have objected to your intrusion if they weren’t lying slumped against a nearby desk with an alien birthing cavity where their guts used to be.

Brigador is the antithesis of that. Its sky-high isometric viewpoint, panning silently over the streets, gives you little such insight into the fine details. You can’t tell the story of a person from up here—at least, not easily—but you can tell the stories of people. And war is all about people, collectively; people fighting, people fleeing, people dying. Stories of lone figures, unless they hold huge power or significance, are swept away in the tide of shared tales, told through numbers rather than poignant letters to mother. You can pluck lone individuals out, humanise them and piece together their fate, but chances are that they were just one of a hundred, or a thousand, or a million people in the same boat, going through the same motions. Those collective motions, and their collective effects, are the ones that Brigador’s environments make us privy to.

One major target objective recurs through your missions: the orbital guns. Solo Nobre’s surface bristles with these skyward-pointed cannons, designed to obliterate any spacefaring aid that so much as entertains the thought of helping liberate the colony. Naturally, they’ve got to go, but it’s the way they impose on their surroundings, irrespective of context, that fascinates me. Taller than a city block, frequently ringed by sheer defensive walls and expanses of flat asphalt, their incongruousness isn’t just stark; it’s deliberately exaggerated. They invade the space around them, like alien landing craft, making no effort to compromise or integrate no matter where they are. To us, the player, they drive home the extent to which recent rampant militarization has dominated the lives of Solo Nobre’s people. What’s it like to have one of those things in your back yard? On your block? In your cemetery? Looming threateningly, a permanent reminder that the entire colony was, and is, ruled through military force. It’s all too easy to imagine them just springing up one night in a flurry of jackbooted activity, confusing and unnerving locals who understand nothing of the political situation, only that they’re now the unwilling neighbours of the biggest, juiciest, most explosive target in the district.

Most of Solo Nobre looks as if it sprung up overnight, to be honest. Many of the maps have a decidedly frontier air to them, sharply contrasting undeveloped wastelands with industrial and agricultural estates—or outright shanty towns, on occasion—and even developed zones are often distinctly utilitarian, as if the first construction efforts focused solely on establishing the functional basics and nobody’s had a chance to do a second pass. Why is that important? Because it means that whatever worldly influences went into the colony’s initial construction—the decisions, the constraints, the goals—are still relevant. Spaces change meaning over time; they get repurposed, recontextualised, rebuilt, and in the process the original intent of their structure gets muddled. Solo Nobre hasn’t had a chance to get especially muddled yet: everything on the landscape feels as if it has a current, relevant reason to be there. The story of the colony is coded into its infrastructure, fresh as the first coat of gunmetal-grey paint. Roads, buildings, fences, zones.

And wouldn’t you know it? That’s the part that you, with the omnipotent eyes of a SimCity mayor, are perfectly situated to deconstruct—in the analytical sense, I mean. You see the way the streets are laid out and the way blocks are divvied up; the way patterns and biases have formed in the overarching organisation—or lack thereof—of the urban sprawl. What becomes noticeable almost immediately is… lines. Often games with isometric grid presentation will seek to break up the grid; to introduce chaos and noise to obscure the perfect, infinite parallel lines that give their environments such an artificial, manufactured air. Brigador relishes in it. Brigador loves the grid. It goes out of its way to propagate unbroken, arrow-straight walls and roads for miles. They speak of an ultramodern, efficient, painfully austere development process; the kind that rolls out state utilities like a titanic machine, paving anything that stands in its way with no regard for landscape or lives. To be more exact, they make it clear that they’re not the product of democratic civil planning, but of orders from on high, carving up and commodifying the colony like the centrepiece of some debaucherous banquet. In a more striking fashion than any graffiti decal or audio log, these pieces of Brigador’s public infrastructure illustrate the disconnected, totalitarian whims of its administration. A casual flick of a cufflinked wrist and suddenly a neighbourhood is living in the shadow of five storeys’ worth of reinforced concrete. Are you in the way? Time to relocate, Mr Dent.

But apathetic architecture isn’t the same as thoughtless architecture. One of the clearest intents behind much of Solo Nobre’s urban planning is its concerted effort to distance the haves and the have-nots, coddling the former and shutting out the latter. Cramped slums frequently sit side-by-side with idyllic American Dream suburbs, divided by district walls—once again, we return to walls—that have been coated on one side with improbably tall hedges, so their viewers may entertain the fragment of an illusion that all is well in their slice of freshly-mowed Eden. Such proximity between the wealthy and the poor suggests that space is scarce on Solo Nobre, but not so scarce that the former can’t afford to have sweeping lawns and tacky, towering neoclassical McMansions. You could be forgiven for starting to wonder if something’s wrong with the scale, when your titanic walking weapons platform that could put a foot through a tower block suddenly has to crane its neck to shoot over a family home, but no—it’s just another way of illustrating the yawning gulf in privilege to your eye in the sky. One mission takes you out onto the green expanses of a country club, which—along with a sizeable occupying force, obviously—also features imposing gun turrets built into the landscape, poking out the top of more hedge-covered fortifications. Why would a golf course need such entrenched defensive measures, in what we’ve been led to believe was a relatively peaceful time? They can only have been a means of deterrence; of scaring away the riff-raff and making the privileged feel secure, without the excessive use of unsightly district checkpoints and barricades.

Yet even with this sweeping disparity, there’s a common thread in Solo Nobre of humanisation of oppressive spaces. Between hulking pipelines, paved concrete expanses and endless bleak industrial estates, there’s mounting evidence that Great Leader’s priorities were not the well-being of his workers, but here and there are tiny, isolated reminders that people still manage to engage in recreation. A single basketball hoop at the end of a loading dock, lined by rows of identical storage units; a children’s climbing frame in the middle of a muddy plot, ringed by skeletal steel pylons; a lone fifties-style diner, complete with a scattering of those cheap white plastic chairs, bleached by the halogen glow of a communications mast. They’re fragments of lives, not destined to be pieced together into a cohesive narrative, but to simply remind us that even in the city’s coldest, most utilitarian corners, people are not drones. Until now, we’ve focused on tales of communities and collectives, but to view people only in the plural like this is to risk treating them as so many trivial organisms under a microscope, always moving in tides, their individual impulses lost in the swarm. It’s details like these that keep us grounded, so to speak, even while gazing down at the sprawl.

That’s all just history, though, innit? That’s stuff that happened over months, years, decades even. But some of the imprints on Brigador’s landscape are more temporal, left by events far more relevant to your current mission. Solo Nobre’s liberation takes place over a single night—or so it’s implied—and while you may be the first to fire a shot, you’re certainly not the first to make a move.

Traffic. It’s the traffic. You could initially be forgiven for thinking that the streets of Solo Nobre, despite their spaciousness and high standard of upkeep, don’t seem to be getting a lot of use; they’re utterly devoid of active civilian vehicles, trodden only by the assorted war machines of your opponents. Brigador doesn’t feature non-combatant units—other than the tiny raincoat-clad civilians who mill around helplessly until being crushed carelessly underfoot—but nevertheless, you’ll soon find remains of traffic jams around the maps: gridlocked, bumped-to-bumper, clearly long-since abandoned when it became apparent none of it was ever going to budge an inch further. Why would it be so tightly packed, and trail so far back, in a city where the highways are so wide that you could triple-park an interstellar freighter across one without making everyone late for work?

Once again, placement is the key. Brigador’s abandoned traffic isn’t randomly distributed, but concentrated around particular points. Lanes upon lanes of gently cooling automobiles are regularly found clustered in front of district checkpoints, around spaceports, even outside train depots, seemingly stopped in their tracks. A picture forms; a picture of a reeling state power rushing to regain its faculties, crack down on sudden unrest, minimize chaos. Of people hearing the news, sensing the forthcoming conflict, choking the roads with their attempts to flee. Of the two forces colliding in the lengthening shadows of a checkpoint, a cacophony of horns and furious shouts assaulting a grim military police barricade. Evacuation efforts scuppered. Deadlock. Until the Corvids turn up in their scrapyard siege engines and flatten a few city blocks, obviously.

But the exodus of Solo Nobre isn’t a complete failure. As your trail of destruction spirals out towards the edges of the colony, from the urban sprawl to its inevitable, oft-forgotten by-products, signs of relief begin to manifest. Nestled up against neglected pipelines and crumbling walls are clusters of blue tents—the kind of blue they only ever use on tarpaulins and concert port-a-potties—propped up with flimsy poles, dulled by the mud of the wastes. They’re ramshackle, disorganised, and frequently located in spots of dubious tactical importance, all of which suggest that while the materials might come from a Loyalist source, they’ve certainly not been set up under any kind of military coordination. Indeed, their most unifying quality seems to be that they’ve been pitched out of the way of populated zones—presumably by people who have had quite enough near misses with cluster mortar strikes for one night. These are camps set up by refugees, no way around it; people fleeing the power struggle, one way or another, trying to hole up somewhere so backwater that nobody would waste time fighting over it. Alas, as the presence of you and your enemies implies, they’re disastrously wrong. But that can’t be helped now, can it?

I suppose the only thing left to wonder is what, if anything, Brigador hopes to make us feel with all this effort. It leaves features on the landscape to tell us that these things happened, but despite our inarguable involvement, never ties those events back to us; never blames us for displacing innocent people, destroying their homes and gibbing them in the streets with careless cannon fire. In a game that encourages you to look at your environment in terms of little more than the cover it offers, it’s easy to tune out such ghastly side effects, particularly when the only feedback you get from razing civilian buildings to the ground is a miniscule bonus—yes, a bonus, perplexingly—to your end-of-level payout. No guilt, no joy, just a matter-of-fact occurrence. But as a mercenary, fighting first and foremost for a sodding huge cheque, perhaps it’s only appropriate that the only stimulus you get from needless destruction is an insignificant increment on your score counter. What better metaphor could there be for the faint flicker of acknowledgement, cold and distant as the shores of Titan, in a mind focused entirely on the task at hand?

It’s not easy, communicating using only the features that are visible to passing airliners, but Brigador plays to its strengths. It focuses on sweeping trends and dramatic shifts—which are, of course, common during times of unrest—using them to speak of the effects of dictatorial regime and violent power struggles, but scatters around visible one-off details too, as humanising fragments for those who stop and take notice. Nobody could ever describe it as an epic narrative tour-de-force, but I find it to be a fabulous example of working within limitations; of understanding how sociopolitical transformations can embed their effects in the landscape, and how we can read them back again—so long as they aren’t demolished by a Killdozer first, anyway.

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Creeping Death Of Multiplayer’s Persistent Social Spaces

I didn’t hang out much as a teenager—or at least, I didn’t think I did. In fact, if you’d asked me to, I would’ve most likely looked at you like I was some distant intergalactic visitor from an alien society; the kind that doesn’t understand the concept of things like sleeping, or capitalism, or brunch. “’Hang… out’?” I would have asked, making sure to enunciate the quotation marks with as much feigned confusion as my tiresome pubescent whine could muster. “Like, just sit around somewhere? Why? What would we do?”

The subtext was intentionally clear: if it didn’t involve video games, I wasn’t interested. And yet, as obstinately, destructively anti-social as I was during this crucial developmental stage, the reality was that I had favourite hangout spots just like any awkward youth; a special variety of hangout spots that—thanks to the changing landscape of online multiplayer models—I now worry may be disappearing forever.

Shared virtual spaces aren’t anything new. Ever since the first mainframe programmers found themselves with too much time on their hands and not enough online pornography, people have been using computers to enter shared worlds, chat with one another, and (usually) kill things along the way. Client/server models—wherein a multitude of players connect to some central host machine responsible for running the game and maintaining its world—have endured since those primitive times, through the rise and fall of deathmatch, all the way up to the present day. The spaces have gotten larger, the rules have diversified, and the technology has become exponentially more complex, but the basic model remains popular, both on an abstract and practical level. In computer communications they call it ‘star topology’, because of the radial organisation of connections: a set of clients all linked to a common focal point, through which they act and communicate. Simple and reliable—well, as long as somebody doesn’t unplug the hub again, mum.

But what does ‘a server’ even mean these days, anyway? Contemporary online gaming has done so much to cushion its audiences from the fiddly details of its implementation that their role has become amorphous at best. For many games, ‘the servers’ are just the developer’s anonymous workhorses, of which everyone is vaguely aware but nobody ever sees; nameless machines working behind the scenes, providing temporary receptacles for a matchmaking algorithm to funnel players into. For all intents and purposes they’re totally interchangeable, distinguished only by their physical location. People file in, people play a game, and people file out. No muss, no fuss.

That wasn’t how Counter-Strike: Source did things, though.

No, it was quite a different story. Like many multiplayer shooters, the overwhelming majority of servers were operated by the community—often with their own customised map lists, rules and mods—and the only way to play was to explicitly pick one from a list. Crucially, this gave them distinct identities and distinct audiences, as they were always all-too eager to announce. “24/7 DUST2 NO SNIPERS” proclaimed one server name, promising endless no-nonsense shootybangs for the most vanilla of vanilla white boys. Names like “GunGame DeathMatch #1 | SKINS | STATS | RANKS” and “Lo-Grav ScoutzKnivez 100tick” jostled in the browser’s mix, alongside more mystifying and exotic options that would no doubt download hundreds of scrappy custom assets at the drop of a hat. Clan tags and URLs were proudly displayed, like club logos and sponsorship placards, signalling that their servers were not just a service delivered from on high; they were a product of people coming together, passing the money tin around, and carving out a space for themselves.

A space. That was what was most important. Not the physical space of a shelf on a server rack somewhere, or the transient virtual environments we’d perpetually pepper with bullet holes, but the abstract, persistent space of the server session itself, shared by every connected player. A space in which everyone is implicitly present and able to speak with one another, communicating through the chat box and an untold number of scratchy, low-quality, early-2000s headset microphones. With a matchmaking service, that nameless space only persists for the duration of the match before being recycled and lost forever, but when it has a name and an address, it becomes fixed; a point that people can find and return to again.

What happens when a space has all these qualities? When it’s available to many, appeals to a relative few, and has room for a few dozen at most? When it enables play and conversation, and allows them to coexist with minimal detriment to either? When it can be counted on—barring unexpected downtime at the hands of a cheap, disinterested server host—to always be exactly where you left it? A space like that can only take on the role of a focal point; a place of casual congregation. People drop in and drop out, some only staying for minutes at a time, but there are regulars in the mix; familiar names, recognisable avatars. People with nothing in particular to do and nowhere special to go, drifting in from school and work and heaven knows where else, ready to get back on a treadmill they’ve been turning for the better part of a decade. These spaces, these servers, were my hangout spots. They were the secluded cafeteria table, the climbing frame at the local park, the chalked-up goalposts on the wall behind the deli. Places that would give you something to talk about. Places that gave you an excuse to be there, for as long or as briefly as necessary.

It doesn’t feel quite right, waxing nostalgic about a period of my life when I so carelessly frittered my time away, learning nothing, scarcely developing as a person, ensconced in an atmosphere so masculine and juvenile that it’s a wonder it didn’t permanently turn me into the worst kind of gamer. And yet, it’s rare to experience such a natural sense of tight-knit community in the world of video games: no lobbies, no premediated arrangements, no guilds, no forum boards or profile pages, just people informally sharing a space, coming back again and again to a hub until they gradually get to know one another. Death in Counter-Strike is often swift, and—until the next round, at least—quite permanent, so it’s not uncommon to find yourself without much to do for the next few minutes besides spectating the remaining players and chatting with your fellow deceased. Here’s the guy who inexplicably snipes better when he’s drunk, and there’s the head admin who pops up once in a while to abuse his divine powers and fuck with people. Here comes the exhausting pre-pubescent kid who gets ritualistically teased, and over there is the guy who probably hacks but is too charismatic and fun-loving to ever ban. Did I form lasting friendships with any of them? Good lord, no. But they made for far more engaging playmates than complete strangers plucked arbitrarily from the matrix, and they couldn’t have become that without the common ground that the server provided.

For me, those days of inhabiting such a shared social space are gone; thrown into the dustbin of my teenage time-sinks alongside Runescape and habitual masturbation. Like many other people with fruitful, busy lives, I’ve grown to appreciate the convenience of being able to jump in a queue and just get a straightforward, uniform, as-intended multiplayer experience with people who are more-or-less appropriate competitors, no matter how thickly the dust has settled between sessions. But what is multiplayer when everyone’s either a total stranger or an established friend? What is multiplayer without any sense of place, or belonging? The prevalence of matchmaking systems, and the gradual shying away from community-run servers, has made online play more accessible—and rightfully so!—but the, temporal, fleeting, impersonal encounters they create are no social substitute for the virtual equivalent of the skate park outside Leederville station. We’ve wedged other systems into place to try and connect people across the treacherous, shifting waters—friend lists, teams, guilds, that sort of thing—but like many one-off secondary social networking solutions, they usually serve only to formalise connections already made through other means. “How do we play? Oh, right, I have to add you on this thing first. What’s your tag? Yeah, yeah, sent.”

None of this is necessarily an attempt to champion one thing over another: I don’t believe that the model of using servers as small-scale social hubs should supplant other multiplayer models, nor do I think that my endless hours spent being gunned down by the same few-dozen maladjusted young Australian men was a proper substitute for developing… y’know, actual social skills. Nevertheless, as with most tectonic shifts in gaming, it’s hard to shake the feeling that we’re not collectively fully aware of the significance of the baby currently riding out the door on a tide of bathwater. Multiplayer should be about people as much as it is about play, and as long as both are involved, there ought to be room for the chalked-up goalposts on the wall behind the deli.

428 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Lost Legacy of Doom’s Hitscan Enemies

I’m dancing. My feet follow no pattern and make no sound as I glide effortlessly over the terrain, but the rhythm of the Super Shotgun guides my every move. I weave to and fro among the soaring fireballs and scything claws, spotting opportunities, darting near and far, catching hellspawn in efficient point-blank bursts of scattershot. Boom, click, ker-chunk. Boom, click, ker-chunk. Boom, click, ker-chunk. Somewhere in the back of my head, I’m dimly aware of the familiar noise of a pneumatic door sliding open, barely audible above a tinny MIDI rendition of ‘Fear Of The Dark’. It’s catchier than you’d think.

Somebody roars. I’ve heard the sound enough times to recognise it as a ‘somebody’. Startled, I pivot to catch sight of the new assailants: two heavyset bald men, cradling imposingly large guns, furious piggy eyes as red as their bulky chestplates. Chaingunners. Before I can close the distance, they open fire, tearing an abundance of new holes in my circle-strafing, road-running backside. I put them out of action, but the damage is done. Was that a fair exchange? It’s not as if I could’ve outpaced their shots. Are they a fun enemy design in this, the most famous of all famously fast-paced first-person shooter? My kneejerk response is ‘no’, but Doom—because of course, it’s Doom—is a lot smarter than it seems.

Few games can claim to have lived as long and as healthily as Doom. Of course, it’s had the unwavering support of a community on its side, constantly tweaking and touching-up and doing everything in their power to stop the wrinkles under its eyes from showing, but its simple formula and flexible combat were always going to hold up well against the test of time. Doom has influenced the design of the modern first-person shooter in more ways than I could possibly articulate, with a little bit of DNA in everything from ARMA to Ziggurat, and yet… I feel there are one or two lessons from it that never quite caught on.

See, the concept of the ‘old-school’ first-person shooter, while not especially formally defined, is very much a thing. We’ve seen bits of it in the likes of Painkiller, Strafe, Tower of Guns, Dusk, Desync, Devil Daggers, and yes, even Doom 2016: games that buck dominant design patterns to focus on swift, streamlined, evasive movement, and a host of enemies that force you to make the most of that movement. Out of style, but by no means out of their depth, these games take after Doom more than most, but no matter how much they borrow from it, there’s one particular feature that many seem to skirt around. Something regarded almost with a kind of hushed, ‘we don’t talk about that’ shame, like the uncle at the family get-together who isn’t allowed to leave the country for reasons that nobody’s quite sure of. Hitscan enemies, a regular staple of Doom’s encounters, have near-vanished from the contemporary games that bear closest resemblance to it. What happened?

Well, at a glance, they do seem to clash with the desired experience. Doomguy can outrun a lot of things—many of which need at least fifty supervised hours logged before you can operate them independently—but he cannot outrun bullets, nor buckshot. You can’t dodge a hitscan enemy’s attacks by just going fast; the nature of Doom means that they take no time to pivot and have impeccable aim, other than the inherent spread patterns of their weapons. Your only recourse, it would seem, is to get out of range—a bit of a tall order, in most scenarios—or to take cover, which sounds like it would go directly against the fast, exciting experience of running around with the wind in your hair and a rocket launcher under your arm. ‘Cover’ is a dirty word; one that brings to mind hunkering behind a chest-high wall, plinking away at a succession of targets and crawling out only when a grenade gets tossed into your lap. To be in cover implies one is at rest, without any of the spatial analysis, fast-paced action or thrilling escapes that characterise the rest of the combat. You can see this stigma manifest frequently in retro first-person shooters, which often come hand-in-hand with the attitude that cover is for babies, and charging blindly into battle with your enormous, impenetrable testicles hanging out on display is the only acceptable combat strategy for ‘real men’. You could probably write a hefty tome about how unhealthy pulp action-hero masculinity has seeped through various layers of media and eventually pooled, like a discarded half-finished McDonalds’ thickshake, in nooks and crannies of gaming obscurity, but that’s a discussion for another time.

The thing is, Doom itself doesn’t actually work that way. In fact, it does a number of things to ensure that hitscan enemies don’t stifle the player’s movement, but instead add an extra set of considerations and trade-offs, forcing them to look at the play space—and when and where they position themselves in it—in a more nuanced manner. Like most of the ingredients that go into a first-person shooter, the way Doom’s hitscan enemies work is subject to its encounter design—a surprisingly diverse field, as custom WADs frequently demonstrate—but there are a few qualities to them you can count on in every sensible encounter.

Let’s break this down, piece by piece. Of the five enemy types in the first two Doom games with hitscan attacks, the three most common ones by a large margin are the ‘former humans’: undead soldiers who utilise conventional firearms—provided your definition of ‘conventional’ extends to a portable belt-fed chain gun, I suppose—and have all the durability of a cardboard cutout of Master Chief that somebody left out in the rain overnight. Upon noticing the player, they give a suitably enraged bellow and enter their attack routine: move, pause, shoot (if possible), repeat.

This pattern gives us time. Like a fireball whistling through the air, it gives us a chance to handle our predicament by reacting and moving quickly. It only takes an undead sergeant a few tenths of a second to level his shotgun barrel at you—give or take a bit of bumbling around, as they are wont to do—but in the world of Doom, it’s enough to at least start on a decisive manoeuvre. Doomguy runs quickly enough that you can very likely put something between yourself and your foe before they fire—it doesn’t even have to be a wall; other monsters serve perfectly well—and since the poor daft AI has no concept of suppressing fire, you need only be behind it for the split-second it takes them to return to their ‘move’ state. Consequentially, cover is less about clinging to the warm, comforting bosom of a solid wall and more about rapidly, momentarily repositioning yourself when the situation demands it; diving around corners, circling pillars, making use of the nearest solid thing in a pinch and immediately darting back out again. Taking cover is every bit as much about clever, well-timed movement as circle-strafing a pack of imps, and to be honest, probably demands far more split-second decision-making.

Another quality that’s critical to the success of the former humans is their relative squishiness: you can usually count on a single shotgun blast to put one out of action, and even glancing shots are likely to interrupt their routines long enough to buy some extra breathing room. A crowd can be swiftly dealt with by just raking a chain gun across their ranks—conveniently, the exact weapon dropped by the strongest former human, the Chaingunner—and pointing anything bigger at them is usually outright wasteful. This is key because it means that they’re only a very short-term threat—or, in larger battles where they’re mixed up with other enemies, only a threat for as long as you ignore them. Ducking behind a pillar once to evade a sergeant’s buckshot is a rush, but having to go through the same motion two or three times is stagnation. By letting you remove the former humans from the fight almost as quickly as they appear, Doom lets you quickly lift the restrictions they impose and expand the space where you can freely move, ensuring you’re never tied to one piece of cover or trapped in some godforsaken alcove.

But not every hitscan enemy in Doom goes down so easily, does it, hmm? I’m going to gently refuse to acknowledge the Spider Mastermind—a rare, highly-situational boss that squats unpleasantly at the end of the first game like a cane toad under the wheels of your dad’s Hilux—and instead concentrate on the notorious Arch-vile, whose pale, emaciated, lanky form is enough to set off half a dozen panic alarms in any Martian marine’s head. It’s everything the former humans aren’t: fast, durable, and capable of suddenly blasting half your health clean off from the far side of a munitions bay—to say nothing of its ability to revive fallen monsters, unravelling your work more and more the longer you leave it standing. Crucially, however, while the Arch-vile makes for a more persistent and punishing threat than the former humans, it also gives us much more time to work with. It takes about three full seconds of dramatic posing for an Arch-vile to wind up its hitscan attack—a pillar of infernal fire that explodes around its target—and once again, you are only required to actually duck behind something for the split-second when the attack connects to avoid taking damage.

Consequentially, while our vitamin D-deficient friend does rather firmly, briefly force players into hiding, it also affords us the opportunity to stretch our legs and take nontrivial actions in between its attacks, giving it a distinctly different effect to Doom’s other hitscan enemies. Between every Arch-vile’s attack, there’s time enough to dart around the immediate area, change cover, take care of some lesser enemies, or—most likely—run up to it and empty both barrels into its repulsive mug. At an abstract level, the Arch-vile clamps down on the player by forcing them to be out of certain zones at certain times, but doesn’t make those zones inherently damaging to cross, like a crowd of former humans does.

Putting everything back together, Doom’s hitscan enemies are designed not to eliminate movement, but to carefully squeeze it; to force the player to take action, moving along vectors towards positions of safety. Restrictions on where in the combat space you can safely be are what make Doom’s fights engaging, and the restrictions that hitscan enemies provide are every bit as important to your positioning as a Revenant’s homing rocket or an Imp’s tossed fireball—they just take a different approach. Yet they’re also designed to ensure you’re never required to linger at your destination a moment longer than necessary, either by being easy to remove from the battlefield, or by only periodically applying their particular brand of pressure. Like every enemy in the game’s toolbox, they can be abused and used outside of their ideal roles—take a peek at The Plutonia Experiment, half of Final Doom, for some truly breathtakingly rude Chaingunner placement—but their basic principles are every bit as valuable as their peers.

Doom will force you to move, but it will never force you to stay. And that’s the philosophy that every first-person shooter should be built on, really.

844 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Beauty Of The Breach

SWAT 4 is not a tactical shooter.

Oh, I know it very much looks like one. There’s a gun poking out from the bottom right quadrant of the screen, and on occasion you may be called upon to shoot it at somebody. At your command is a squad of interchangeable burly American men, who will do their best to follow your orders—or at the very least, try not to get in the way too much—and most missions are rife with the deafening clatter of confined submachine gun fire, punctuated by overlapping barked orders and screams. It has the punishing damage model of a tactical shooter, the realistic spaces of a tactical shooter, and the po-faced no-nonsense attitude of a tactical shooter, along with numerous other qualities shared with Rainbow Six and Counter-Strike and goodness knows what else.

But SWAT 4 isn’t really about any of those things. They’re ancillary elements at the most, which is fortunate, because giving orders is a clumsy menu-driven nightmare and the weapons are about as useful in your hands as a succession of aggravated iguanas. A rifle in full-auto firing mode might as well just eject its magazine onto the floor, given the odds of it hitting anything you point it at, and by the time you’ve marshalled your squadmates into position, whatever advantage you hoped to achieve has probably long since passed. You have snipers positioned around some levels, peeping into windows, but they don’t do anything on their own except announce when they spot something; you have to bring their view up on a picture-in-picture display, telekinetically wrest the gun out of their hands, and take the shots yourself. If SWAT 4 was a tactical shooter, it would be an utterly intolerable one.

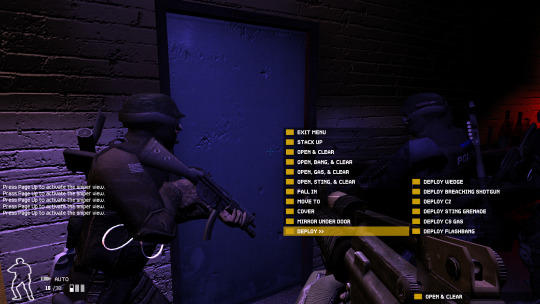

Fortunately, SWAT 4 is actually about doors.

Doors. They’re a simple fixture, at least in contemporary settings. Hinges, frame, lock, handle. Just a thing that buildings have, so ubiquitous they might as well be invisible. Most games model them that way: press A to open, press A to close. Maybe there’ll be a lockpicking minigame, if someone really doesn’t want you getting in there, or maybe you’ll have to go hunt down the key. Doors are temporary obstructions at most—one step removed from literal ‘gating’—and often amount to little more than set dressing. This is reasonable. This is acceptable.

What you need to understand about SWAT 4, though, is how its missions unfurl. Being a good cop—and, crucially, an alive cop, who brings in people alive, to the fullest extent possible—means staying in control of the situation. If you have civilians running around like headless chooks, suspects hiding god-knows-where and your squad scattered all over the shop, things are inevitably going to go wahoonie-shaped. You need to be disciplined and methodical; acutely aware of which spaces are unsafe, securing the area one step at a time, moving from room to room and sweeping them thoroughly. To this end, you must master the breach.

You know, the breach; the moment when half a dozen armoured cops suddenly storm into a room brandishing guns, screaming at everyone to get on the ground. A disorienting whirl of action where everything goes from order to chaos and back again in the span of a few crucial seconds. Carried out correctly, it means taking everyone by surprise and having the weapons safely out of their hands before they know what’s going on; carried out incorrectly, it means a lot more yelling, and gunshots, and possibly cleaning up. How you choose to execute the breach is the primary factor that decides its outcome, and the conduit through which it is carried out is, invariably, one or more closed doors.

So what’s it going to be? You can, of course, just open the door, run inside blindly and hope for the best, if you’re the kind of person who crosses the street without looking. On the other hand, if you’re feeling cautious—and it should go without saying, I hope, that it pays to be cautious—you can take a moment to stick a fibre-optic camera under the door frame and take a peek first, to scope out the situation as much as your viewpoint allows. From there, you can make informed decisions about how your team’s going to burst in. Will it be a quick ‘open, flashbang, clear’? Or perhaps, depending on who’s watching the far side of the door, the precious second or two taken for a grenade to skitter across the floor is too much to ask for. It might be wiser still to try another door, and wedge this one shut so nobody sneaks up on you.

As in life, though, some doors are locked. This doesn’t present much of an obstacle to you, an officer of the law, but once again there are decisions to be made. Lockpicks are discreet and work without fail, but are a bit slow in a pinch. A flashier option is to blow the door wide open with a parcel of plastic explosive, which has the added bonus of momentarily disorienting anyone near the entrance, but can hurt or kill anyone too close to the blast. For a safer and far faster approach, you can simply shoot the lock off with a breaching round—a special shotgun round designed to not ricochet or hit things behind the door, as shells are wont to do—but it won’t give you the same breathing room, and leaves you standing in the open doorway holding a shotgun like an absolute lemon.

But I didn’t drag you this far to gush sickeningly over police violence, strangely enough. SWAT 4’s doors are important because they’re a prime example of how modelling complex interactivity—even in something otherwise perceived as relatively simple—can alter the focus of a game for the better. We’re used to our environments being simple models, because time and resources are finite things, but the right verbs in the right place can transform an otherwise familiar formula into something strange and different. Could SWAT 4 have done something similar with windows? Walls? Why not go deeper down the rabbit hole, and let the player open doors to specific angles, or target the hinges instead of the lock? Potential for complexity in the mundane is everywhere, and can be fleshed out to create new experiences without disrupting the delicate mechanical frameworks we rely on for stability.

And that’s what they are: frameworks. Rigid structures that define a rough outline sufficiently enough to stop the whole thing collapsing in on itself, allowing creative freedom elsewhere. A first-person shooter doesn’t have to be about first-person shooting, as inane as that may sound; it can be no more than the formula that allows a game to explore something only tangentially connected. With every intricacy afforded to it, something as trivial as a lump of wood with a handle on it can grow ever more central to the experience, until it becomes the prominent feature on which everything else (ahem) hinges. Doors. Door puns. Love ‘em. Goodnight.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Officer Benny and Characterisation in Stealth

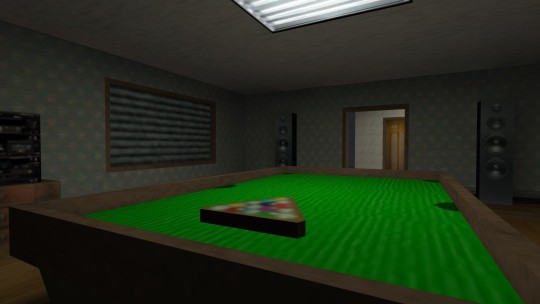

There's a very special NPC in Thief II: The Metal Age. In the dimly-lit games room of the Truart Estate, surrounded by the discarded playing cards and abandoned dartboards of the recent party held by the Sheriff and his debaucherous toff friends, a lone drunken City Watch officer disconnectedly rambles to the barmaid on duty. His name is Officer Benny, and I love him.

"I can't believe that s-some (hic) taffer went and spilled mead all over that rug!" he yells as you approach unseen, his model swaying unsteadily in a dramatic display of intoxication. The barmaid, clearly worn out by a harrowing work shift, sighs wearily.

"Benny... you spilled the mead on the rug," she explains patiently. "Anyway, someone is on the way to clean it up already."

"But you don't understaaand!" Benny wails, now clearly, inexplicably on the verge of tears. "These (hic) taffers have no respect for such... b-beautiful things!"

Around this point, it’s likely that you’ll start to tune out and skulk around in the gloom, looking for the telltale glint of loot to funnel into your pockets. Stacks of coins and rings litter the gaming tables, tempting you to sneak a hand under the hanging lamps. One of Karras’s Children—a hunchbacked steam-powered automaton with a head like a brass football —clanks around the room, mindlessly praising its creator to the heavens. It’s not much of a threat, but it’s certainly an annoying little contraption. One water arrow to the boiler grate usually does the trick.

"Benny, I think you've had too much to drink. Aren't you supposed to be on duty?"

“Hah. So what if I am, huh?” he says, sounding more than a little defensive. “Anyways, I work mm-better when I’m drunk. It makes me fearless! If I see a bad guy, I’ll just point my sword at him, and saaaaaay… HEY, BAD GUY!”

You freeze, momentarily worried you’ve been spotted trying to snaffle the discarded goblet from beside the fireplace. Benny continues with his charade, utterly oblivious.

“You’re not s’posed to be here! G-go home or I’ll stick you with my sword ‘til you go ‘Ouch, I’m dead!’ Ah-hah-hah-hurgh!” He makes an indescribable sniffing, gurgling, chuckling noise, and momentarily falls silent. “See? Ain’t no one gonna be messin’ with ol’ Benny.”

“Whatever, Benny. I think you should sleep it off. No more mead for you.”

In the grand scheme of things, it’s a fairly trivial exchange: it doesn’t tie into some larger arc, it doesn’t impart any useful information about objectives or security system vulnerabilities, and neither Officer Benny nor the barmaid will ever be seen again. Benny’s emotional ping-ponging is unconvincing at best, and while his delivery certainly isn’t lacking in vigour, the only character in the room with exceptional voice acting is Garrett, the Master Thief; the one surreptitiously pocketing everyone’s gambling winnings during this exchange. And yet, Benny’s rambling accomplishes something very special. It’s the perfect, emblematic example of a quality present throughout the Thief games; one that shapes how we approach them, and in turn, the experiences they provide.

Thief II gives you a sword. Not a discreet little knife, fit for a slippery cutthroat, but a proper blade; the kind for lopping off soldiers’ limbs on a muddy, arrow-strewn embankment. It’s a silent acknowledgement that you may have to kill men, not in a surprise scuffle where you jump them from behind the bins, but in a full-on fight with multiple assailants. It’s the kind of thing you defend yourself with when things are rapidly going downhill and there’s nowhere to run; a tool for when the halls are filled with the sounds of alarm bells and clattering jackboots. In the right hands it can be quite effective, and it’s entirely possible to hack n’ slash your way through a legion of aggravated soldiers, provided they’re courteous enough to approach you in a narrow corridor or something.

Something doesn’t add up here, does it? Stealth needs reasons for you to stealth, so to speak. There have to be incentives to keep you in hiding, and those incentives usually start with some sort of punishment for being caught. You’re supposed to be outmatched and outgunned, or at the very least, have some higher-level motive for not wanting to be seen. If Garrett can accomplish his goals by going where he pleases and stabbing everyone who looks at him the wrong way, what’s stopping him, really?

Well, it’s kind of a dick thing to do, of course, but gamers have never been above murdering NPCs for slightly inconveniencing them. It’s also a flat-out fail state on many missions if you attempt them on a higher difficulty setting, but by the time you get around to them you’ve almost certainly put the idea out of your head long ago in any case. Dishonored, Thief’s darling modern protégé, would invisibly bump up the Chaos meter—a hidden metric that determines whether Corvo’s been naughty or nice—but Thief itself has no such system, and other than occasionally dropping remarks along the lines of “remember, murdering people is for poser scrublords”, does little to impress upon you the moral wrongness of your actions. A corpse is functionally identical to an unconscious body—indeed, were it not for a single line of HUD text, they’d be impossible to differentiate at all—and sure, people might be a bit more screamy if you clobber them over the head with a blade rather than a blackjack, but what does that matter if you’ve already established you’re not interested in being quiet?

No, Thief II chooses instead to work with characterisation. Who, of the people you encounter throughout its missions, are your enemies? Not the tired watchmen trudging through the halls on a cold evening; not the harmless peasants, trying to prosper in an industrial revolution even as it crushes them between its wheels; not even the Mechanist underlings, suckered into a fad cult and set to work fulfilling Karras’s insane agenda. Your foes are far away, clinking glasses in rooms full of light and music, and most of them will never meet you face-to-face. What direct quarrel do you have with the guards who patrol the game’s moody locales, besides the fact that they’re between you and your goal?

Right. They’re not your enemies, so Thief doesn’t characterise them as enemies. Engendering sympathy to discourage murdering NPCs is hardly a novel concept, but Thief’s approach stands out, primarily because it’s less about pre-emptive guilting and more about subtle humanisation. While you creep around behind their backs, guards will hum, whistle, recite passages, moan about the cold, mumble to themselves, even wonder aloud when they’re getting dinner. You’ll find guards cracking jokes, trash-talking each other’s employers, discussing financial management, complaining about the weather, worrying about being replaced by the new-fangled mechanical eyes, and a thousand other ordinary things totally unrelated to the here-and-now of their work shift. They’re not goose-stepping around shouting “boy, I sure hope nobody stabs me in the back while I’m pacing back and forth, how would my wife and three children ever survive on the streets without a loving father like me?”; they’re just… well, bored, usually. Wouldn’t it be terrible to have to cut down a person like that, just because they made the mistake of investigating some footsteps a little too closely? Thief makes you want to stay unseen, not for your own sake, but for the sake of those who might see you.

And Officer Benny? He’s the epitome of this humanisation. Not only is he drunk, chatty, skiving off work and chewing the scenery with an unprecedented level of unhinged abandon, but through his babbling, he offers an insight into his attitude. There’s no black, tarry pit of hatred boiling away somewhere in him, fuelled by some personal vendetta, waiting to bubble over in fury at the sight of a wayward miscreant; he’s just doing what he’s supposed to. Benny sees himself as the cop in the proverbial cops and robbers: a figure of authority in a simplistic world, out to stop the scoundrels and ruffians in a game where everyone mutually agrees on the rules. His inebriated cry of “HEY, BAD GUY! You’re not s’posed to be here!” is born of this position, announcing what he sees as incontestable truths, spoken more out of convention than anything else. And what’s his ultimatum? Go home, or get stabbed. Go home. Even faced with someone absolutely, undeniably in the wrong, in his morally black-and-white world, his first thought is of telling them to scarper; to leave peacefully, without accountability or interrogation. He’s not smart, or nuanced, or even—if you catch his attention—particularly true to his word, but Officer Benny’s attitude is charming in its simplistic naivety, devoid of real malice or antagonistic ideals. For that, I could no more swing my sword at him than kick a puppy, and that’s why he holds Thief II’s formula together—along with countless other watchmen, guards and Mechanists.

Thanks, Benny. I hope your hangover wasn’t too rough.

230 notes

·

View notes

Text

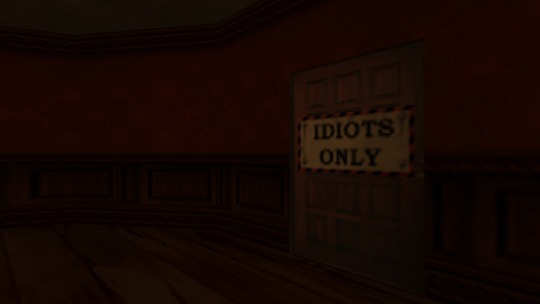

The Intimate Tourism of House Maps

Creativity is hard. Really hard. I regularly run into people who claim to simply not have an imagination, and while I’m not one to insist that every human being is a boundless font of wondrous fantasies waiting to be uncorked, it seems far more likely that they’ve just underestimated the difficulty involved. Creativity without bounds is even harder: confront most people with a blank canvas and they’ll probably struggle to do more than doodle idly, or fall back on some reliable standby, like a still life of a fruit bowl or a drawing of that cool S that every primary school kid knew how to make.

It’s the same story with level design, naturally. When granted the infinite power of the Hammer editor—alright, not so much ‘infinite’ as ‘modest, obtuse, flexible, a little bit buggy’—a lot of people tend to forego alien landscapes and secret laboratories, instead opting to recreate… their house. Or their school. Or their office. Familiar, mundane spaces; the sorts of places that the designers must’ve seen every day. Such maps litter the Counter-Strike community’s ageing archives, passing slowly into total obscurity alongside de_dust2 clones and deathmatch yards with misaligned textures.

As far as most people are concerned, the appropriate response is “good riddance to bad, unplayable rubbish”. They were crap. Counter-Strike, contrary to its gritty, tactical façade full of burly men with military hardware strapped to every inch of their body armour, doesn’t actually perform well with faithfully recreated realistic spaces. They’re too cramped, or too wide-open; too cluttered, or too empty; too full of areas that are impossible to hold down, or impossible to assault. You ever do that thing with your housemates where you’re both heading towards one another in a corridor and neither of you can pass because you keep picking the same side to pass each other on? Right. Now imagine that you have the size and flexibility of a fridge freezer. Also you’re stuck in a door that won’t stop trying to open, and you’re being shot in the shins, and your housemate is actually a man in a balaclava who fucked your mum.

What I’m saying is that these maps had very little value as spaces for play, which is—rather understandably—the only metric we ever really gauge them by. We see level design as a means of creating a product; an arena for twitchy young men to gun each other down in on a lazy Sunday afternoon. A map is the platform on which experiences play out, not the experience itself. Nevertheless, like any blank canvas, the level editor’s grid is a creative medium through which aspects of the designer can seep, and while most maps are pretty outrageously poor at getting such aspects across, it’s a different story when the map itself is a recreation of somewhere the designer has personally left their mark on.

Have you ever wanted to see inside a stranger’s home? I don’t mean in a creepy, antisocial, ‘stake out for twelve days working out when it’s safe to break in and sniff the toilet seat’ kind of way. I’m talking about seeing a single incandescent square on the side of a darkened apartment block on your evening train ride home, and wondering what kind of life that person lives. I’m talking about waiting in the living room of a stranger while they fetch the television you bought off them on Craigslist, taking in every possible detail out of mild curiosity; I’m talking about wanting to be a fly on the wall, not of somebody you know, but of a person you have no connection to and will never meet, just to see all the little ways that their lifestyle differs from yours. It’s a special kind of intimacy, driven not by perverted fantasy but by the knowledge that everybody’s life is a different story, and the honest craving for just a tiny slice of that story.