A place where I write, draw(?), and encourage myself to never stop trying to create or imagine things. If you wish to support me, doing whatever it is I'm deciding to do, I have a ko-fi where you can! https://ko-fi.com/theweirdowithkohi for more.

Last active 4 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Unbreakable Werewolf: A Wolverine AU.

Chapter One: Names and Places

I’ve been here before. That’s what I keep trying to remind myself, but the chain of time has rusted over, lost to the water below my feet. But I remember it, even if for now it’s just the memory of motion. The waves rocking against the boat, telling us to turn back- only death and death alone awaited those boys. And if all was good in the world, this approaching shore would have seen me among those shattered faiths and buried dreams. Chuck pointed me in the right direction, now it was up to me, to see to this journey. I’m the best at what I do- a truth grafted to my very bones in metal and names. The translator for our guide, both these nice, older ladies, local even; brings me back to now, away from then for the time being. Older, relatively at least. The centuries might be muddied, shaken up, and distilled into a fever dream most nights- but the weight of that passing time never leaves. Most everyone else wears it on their face, but no such honesty was gifted to my flesh- just the strength to carry more than anyone else.

The guide says something that catches my ears- her translator elaborates further, continuing to call this place by a name unfamiliar to me. She says “Iō-tō”, and I taste a hollow sound washing over my tongue, and escaping my lips where another name should be. Another reminder that time always marches on, even if I stubbornly go unchanged against its viscous tides. They shake and rock us around until the island is finally in full view. The translator- she stares at me with concern. She knows that name I failed to keep to myself, and the atmosphere of this journey begins to shift. It is not a name said lightly, and here I am letting it slip. And I keep slipping, as I’m beckoned by this falling feeling. I rode this same journey, to this same island many moons ago. The voice of the older woman is drowned out by a familiar laugh in the corner of my mind. A terrible laughter. The enthusiastic call for Lady Death to try and take claim of an owed life. I feel myself physically turn to this phantom of the mind- but I’m met with his face, in that time so long ago- when still we knew each other as brothers.

“You ever think that shits getting old, Vic?” I asked, my brow furrowed into the near indefinite scowl that shaped my face then. The helmet adorned over my head was just big enough then to make Victor’s hearty laugh reverb on the back of my neck. His words were colder than the sea spilling into our boots and the boots of over a dozen other boys sharing with us this iron coffin, but his face had a knowing smirk.

“God will it that something from us does grow old, little brother.” He took in a deep, self-assured breath, his eyes closed as he went to lean on the right hand side of the craft. It was a shared, cramp space, and it was just our luck that we were furthest up front. Might at least have given these boys a chance if we were beaching anywhere else. After three days of bombardment, the estimates were that the Imperial Japanese fighting forces here were already close to breaking. We were all told it was supposed to just be around five days of cleaning up a suicidal enemy whose will to fight was taken out before we ever touched down on the shore. But the men up top nor the boys slicked in with us couldn’t smell mother nature’s whims as I could, they couldn’t feel the presence of several storms surrounding this place. Victor knew it too. When next he opened our shared dull, gray eyes, his expression shifted back to neutral- it was said in no shared words what we both knew. The enemy barely noticed our knocking on their chamber door. Yet we were about to let ourselves in, uninvited and unwanted intruders that we were.

He sniffed some more, enough to freak out a bright eyed kid sandwiched between us who was shifting around in his position now. “Don’t expect the ‘usual surprise’ when we touch down.” Victor wasn’t wrong either, which had me on edge. This late into the fighting and now they were changing up their tactics. We weren’t to know what the enemy had in store for us then, but it wouldn’t be much longer before history’s quill would record it in blood. His demeanor while cooled, was still a touch self-assured.

We carried the same “gift”, as Chuck would later call it, but he’d taken to believing it made him invincible. Taking a chest full of Gatling’s latest and greatest of the 19th century only to stand back up just in time to surprise some Johnny Reb on the other end has a funny way of inflating your ego, turns out. But we’re still just flesh and bone; no matter how much of it comes back- we still lost it in those older days. All it took was one really bad mistake to really test how much we can come back from. Quentin Canal had bored that lesson through splintered bones enough to last both wars, but this second one would prove to have a lot more in store for I and the rest of the world. We weren’t to know back then. Not a good enough excuse.

That mutual anticipation from that kid stuck between us must’ve caught up with him- either that or the same old motioning of back and forth rocking that every transport during this conflict had seen before, because he’d begun retching over the side of the boat. Instinctively, I lunged for the back of his uniform’s collar and pulled him back into the boat. That led to some of his breakfast to mix around with the accumulated salt water and frightening the daylights out of the poor kid. When he got control of himself again, I remember him stammering out what the hell that was for. “Just cause they’re not on the shore doesn’t mean they can’t take your head off from wherever they are, kid,” I had to shout over the sound of metal and water clashing ad nauseam. Confused, he glanced back towards Victor, who met his expression with a wink. The kid, shaking a little probably due to a mixture of the cold and unease, turned back to me. “So w-why aren’t you grabbing your brother by his s-shirt then,” The kid asked, gesturing over at Victor, visibly confused.

“Because we skipped out on coffee and he could use the wake up call,” the words blunt, more directed at Victor who was hanging his arm out the side, mimicking the movement of the other transport carriers with his hand against the wind as he did. The hope that an Arisaka would knock him out of the boat and into the salty, cold water was too good to be a reality- we weren’t going to see even a muzzle flash for another half hour or so that day. Might’ve done him some good, too. Instead, he just laughed as he always did in the eye of the storm. Leaving me to temper the sails in the face of uncertainty. The kid’s voice brought me out of my train of thought. He was asking me something. The same thing they always ask. I shouldn’t have looked back at him. “What?” Shouldn’t have looked into his eyes and asked him to speak up. “W-What’s your n-name, sir?” Shouldn’t have let him think I was human like him.

“... Logan, kid. Now pipe down, eyes forward!” He stood resolute, putting on a face as if he knew what was waiting for us ahead, looking at me like I was going to get him off of this beach. Even Victor had enough decency to not let people in. I knew it then as well as one could, I knew it when Steve asked the same thing a few weeks afterward, and when Chuck offered me his hand thirty years from then, and then again another five years later when I was ready to try to be wrong. The kid's face was starting to vanish from the picture, a static haze was encroaching like shadows under the horizon- I had to remember, remember his face, remember his name. “It’s J-Jamesky, sir!” Private First Class Jamesky L. Hunnigan, Killed in Action on Green Beach, within an hour of the first day of what would become the thirty-six days and nights of fighting for control of the island formerly known as Iwo Jima. One of an estimated twenty-six thousand, eight-hundred and eighty souls. Should have been me in that number too. Funny how that turned out, kid. Being the best at what I do doesn’t leave room for much else. Good that Dog Tags are light, then. [END OF CHAPTER 1] -------------------------------------------------------------- (If you liked consider supporting me on ko-fi! It means a lot and reminds me that there's no effort wasted in pursuing this! I have no idea what I'm doing all these years later, but I know I want to keep doing it!)

#writing#wolverine#logan howlett#victor creed#fanfiction#marvel au#marvel fanfic#x men#x-men#collaborative#going back to my roots a bit with this one#chapter 1#I have a backlog of chapters for this story that I've just neglected to share for almost a year now#this is part of a collaborative venture between me and a few friends#though I'm the first to upload/publish#keep an eye out for AU fics with “Unbreakable” in the title#tho obviously ask first if that's the case#also yes in this story Logan goes by “Werewolf”#And yes this story alternates between time periods#namely jumping from 1945-1960s Japan#and Japan circa 1999#anyway once more thank you

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

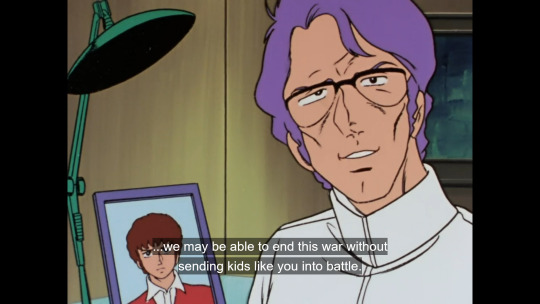

One of the best scenes in any movie, period.

33K notes

·

View notes

Text

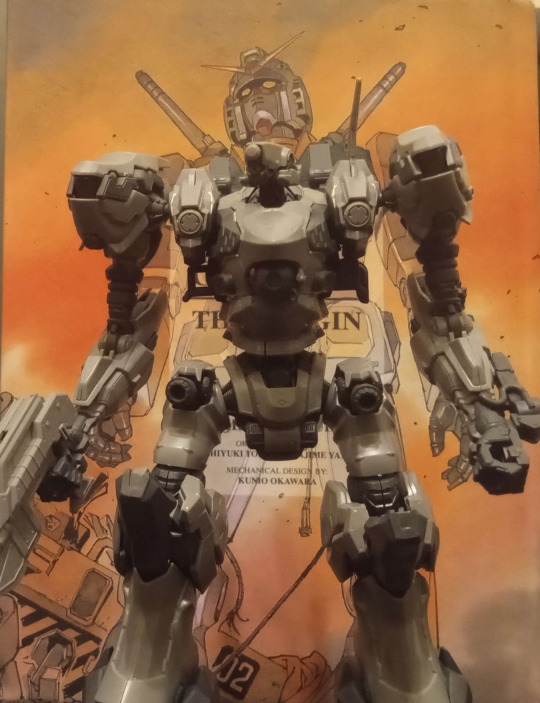

The Soul of Mecha: A Continued Examination of Cultural Context.

Not too long ago, I decided to begin researching and writing about the cultural impact of the genre we've come to know as "Mecha", from its earlier incarnations as a firm power fantasy series not too dissimilar to super hero media of the time- to the inception of the modern face of Mecha with Mobile Suit Gundam (1979) bringing in the "Real Robot" sub-genre into reality, and following the cultural context of the decades that eventually led to Armored Core (1997) for the PS1. The primary focus of said prior essay was mainly a gross oversimplification to talk about the importance of Armored Core as a piece of Mecha media made specifically in mind for the brand new medium it was interacting with to do things through mechanics, narrative, and "feel" that were not possible in its contemporaries both in and out of the medium of video games, and that the legacy of which is still alive and well into present day with releases like Armored Core VI: The Fires of Rubicon.

With that being said, however, it still is as I said- a gross simplification in order to get to the point of that particular essay. So then, what would a broader overview of the genre look like? Well, considering that the previous work was so long it had to be divided into a series of reblogs, trying to tackle that here would come out messy and a bit disorganized. In all honesty, it would be best to leave a subject like that well enough alone. ... So, anyway-

"Real Robot" As A Medium For Reflecting On The Scars and Fears Brought by Weapons of Mass Destruction.

(Consider this a companion piece to the first essay.) It doesn't take much of a thinking person to recognize the titular Gundam and what most of its imitators are as a Weapon of Mass Destruction- both in the text and subtext it draws direct parallels and discussions that were and are echoed sentiments of creations like the Atomic Bomb. On the whole, "Real Robot" as mentioned in the previous essay, was born out of Gundam's lead figure head Yoshiyuki Tomino (富野 由悠季) who deliberately did not want to make another Super Robot show, but something decidedly different in approach, tone, and priorities. To do this, proved to be a rather herculean effort at the time, for nobody in the industry was really willing to try and break the mold on what "Piloted Robots" could be. It was an endeavor that nearly failed, were it not for a deal with Bandai that lead to the creation of "GunPla" (shorthand for Gundam Plastic Models) as we know it. The results of which, need no further re-iteration and aren't the focus of this particular piece. Thanks to this deal, however, Tomino and Studio Sunrise went on to keep Gundam alive as a series and create similar shows in its image as a part of an effort to bring in "Real Robot" as the new face of the genre. Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam (1985) for example, would go on to be a far darker sequel to the original series that proved to be much closer to the original intent of the first series and further expanding what Gundam was supposed to be about- that being the inherent and severe consequences of when war is waged by tools of destruction who's creation was meant to deter any further loss of life- instead contributing an imaginable scale of death the likes of which would only call for further escalation to retaliate.

There's no need to go too much into the parallels with the very real equivalents that inspired Real Robot. From tanks to nuclear weapons, it reads clear as day- especially from the context of a country that was the first to bare witness to the effects of the Atom Bombs. Conversations, discussions, debate have always followed the culture of Japan since then- because how could it not? Officially, however, Japan as a nation and people were not allowed to openly talk about this major world ending event that would change everything about the new age of warfare and deterrence for over a decade. So the ways they began to express these newfound fears, anxieties, and generational trauma, was the same as anywhere else- through art. Before Mecha, there was Kaiju (怪獣), none more famous and influential than Godzilla (ゴジラ 1954) which is the archetypal metaphor for the bombs, atomic weapons, and what it does to a people and society. Point being, using the arts and mediums of story telling, Japan has a long a steeped history in the modern era of writing analogies and metaphors for what was one of the darkest moment in their people's history. What Gundam did wasn't new per say, is the gist of what I'm trying to explain. From more fantastical, to more horror oriented works. From live action, to books- this was all rather well known and a massive part of the cultural zeitgeist. What I think it did that the others hadn't up to this point, at least in brief summary, is that it took those fears and scars- then used it as a jumping off point for both reflection, and observation of a realized future setting that ran with this train of thought. "After the this, then what? What new horrors would we make? What other W.M.Ds would we invest and invent? How would those new generations react to or handle this new technology? What new kinds of wars would be waged with this power? Could the mere existence of such creations keep peace, or lead to further escalation?" All questions that were applicable back then, that are still relevant now, and as relevant as it was in the Gundam's own setting.

It's this origin and point that nearly every work in the Real Robot genre can trace itself back to, even as the times change- bringing with them new anxieties, new fears, and new threats to the world as we know it become realized, Mecha is able to adapt to and take in these incredibly real and unfortunately tangible feelings, because Mobile Suit Gundam was able to graft this core emotion and observation of the wars that inspired it into its very DNA. Even as the idea itself of "Real Robot", that roughly being upright, mostly humanoid mechs starts to feel improbable to some in current era (2025 as of the time of writing this, where in many fields the idea of a bipedal "Mech" ever being used on the battlefield as seen in Real Robot Mecha works, becomes more outlandish)- so to does the genre adapt and include those thoughts. The light novel and anime series 86 (-Eighty Six-, 2017) written under the pen name Asato Asato (安里アサト) for example, is a Real Robot Mecha series- that completely ditches the idea of the machines needing to be humanoid or bipedal, re-imagining them as something closer to insects. This change however, is not made in a vacuum as a concession of modern sensibilities, but is the first in a series of several additions and changes that reckons with what a world using Mechs like these to wage war would look like- incorporating themes of prejudice, racial inequity, societal hypocrisy, dehumanization, and the kind of very real and terrible things mankind can do to itself when faced with an existential threat found in one another. In this we see, the Real Robot genre can and successfully adapts itself to the times and cultural discussions, fears, and climate surrounding its creation- serving as an evolution of the ideas and themes Real Robot grew involved with around the 1990s to early 2000s, but something that feels distinctly "modern" in how it tackles and approaches the subjects it keeps and adds. Just as that Lost Generation Era influenced and evolved itself to its own changes and perceptions, so to does the genre once again.

To bring this point home, the Soul of the Mecha Genre is that of Humanity itself. The heart of the best of these stories and even those that never leave much of an impact on its own, is that of people. How awful, wonderful, terribly brilliant, and brilliantly terrible we can be. How with every way we find new ways to destroy each other, scar one another- that it is still the heart of adapting and persevering that defines any and everything we do. War didn't end with the splitting of the atom, young people didn't stop being sent to die when the Gundam was mass produced- but the world didn't come to an end either, we didn't wipe ourselves out. Real Robot continues to exist because it is a product informed by the scars and realities of conflict, and it's about how no matter how battered and beaten down- we will survive. How the more things change- the more they stay the same; but also how we're changing every second of every day. Sometimes, any particular series can become bleaker than this, or focus so much on the positive traits it can drown out the darkness in a blinding light- but even these are just as emblematic with the genre as with ourselves. In many ways, Mecha itself I consider to be its own medium, more than just a genre. You can bring any story to mecha and ask yourself "What can I express through this?" and no answer is invalid. It's as malleable as the people who created it, and continue to create with it. From metaphors and allegories, to expressions of self and purpose, to yes- even big robots punching other robots; Mecha is a beautiful reflection of ourselves, with as much good and bad as you want to bring with you into and out of it. As true for now as it was when Mobile Suit Gundam arrived on the scene, and even as when Mazinger and Getter Robo debuted on television sets- Mecha has proven that it is itself, an art form that can be as high or low brow as any other work of art, and will always have a place in how we tell stories. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ (Hey, this was a bit of a shorter essay than the last, but took thrice as long to write funnily enough ;-; I wanted to expand on the rather ridiculous length of the original but narrow it down to that overview, but in doing so I ended up re-writing and formatting it to work as a standalone work that asks the question of "What's the appeal with Mecha? What's at its core? Its Soul?" and kind of ran with it from there. Alas I won't take up anymore of your time, thank you to any and everyone who sat down and read through this- it means a lot. I'm still incredibly new to all of this, but I want to in earnest try to really do this. If you're able to or want to, you can support me through my ko-fi which I'll link right here :D Stay safe everyone, and be good to each other.)

#writing#armored core#armored core 6#gundam#mobile suit gundam#personal essay#mecha#日本#japan#ko fi#ko fi writer#86 eighty six#godzilla#kaiju#1980s#1990s#2000s#メカ#レアルロボット#スパーロボット#怪獣#for those wondering#yes I am actually trying to make this into a real career#writing in general that is#this essayist idea has been on my mind for a while and it might branch into video essays in the future#but for now#I'm winging it#I'm sorry if this was kind of just nonsense to some#worried I was meandering a lot#but I've spent to my time editing and stressing over this instead of posting it

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

The world Armored Core throws you in one is an apathetic one, one stuck in this endless cycle of corporate rule and where the value of life is measured in munitions and repair costs weighed against overall payout. It's dehumanizing, dreadful, and always hostile to the people forced to live in it. But most of all, it's controlled. The state of the world, the corporations hiring you and other Ravens, the people living underneath it all- it is all part of the plan. Hidden to all but the select few, the state of this world is held into a stagnant deadlock by the designs of an even greater power. An AI, fittingly dubbed "The Controller", is the one that keeps the world the way it is. It has come to the conclusion that humanity is on a warpath to destroy itself and all life on Earth at the rate its going, and in order to ensure our survival- it has kept us under control. The Corporations are allowed to war and fight with one another because they are not the real rulers of this fragmented world.

Then you show up. Your perseverance has you overcome impossible odds, time and again. Your victories have begun to have an effect on the entire status quo the Controller has desperately put in place to keep everything the way it is. Your reputation has inspired the ire and envy of other pilots, and brought death to many who were directly beneficial to ensuring this entire charade kept going. Your will to survive and overcome every single obstacle, trial, and tribulation- has made you a threat.

You, Raven, just another Freelancer Mercenary, gun for hire- must be eliminated. And try to The Controller does. The game even stops doing what it normally does when you die after this point, because now it shows you a brand new and unique cutscene of the confirmation of your death, and goes to a game over- asking you to reload a save. And this is when the game throws absolutely everything at you, the Controller needs you out of the picture, so that everything can go back to the way it was and it can try to undo all that you've changed. But that's the funny thing about the Human Spirit, isn't it?- it cannot be held stagnant. It's constantly evolving, adapting, changing, and ever pushing us forward to be more than who we are even a few moments ago. It can't stop you, not even as it throws copies of the top AC Pilot "Nine-Ball" after you, which too are AI powered ACs that the Controller specifically has to ensure no one pilot, corporation, or unknown element ever gets too big or changes too much. But we push on, all the same- down to the Controller's very armored core, and destroy it. Humanity, The Ravens, Corporations- we're all left free to grow and do as we please. Is that the right thing? After everything we experienced, learned, fought, bled, died, and killed over- is this what's best for us? That's for us to mull over, as the original game goes to credits. それはアーマード・コア。

And all of it, is a direct evolution of the Mecha genre through the lens of a brand new medium, influenced by the cultural shifts and impacts of the people that made it. And since its debut, the series has quietly hunkered down over its niche, careful to never include anything that takes away from the mission intent established by this first game, but not being so stuck in this idea to be afraid to experiment. Just as the genre of Mecha is a constantly evolving thing, so too does Armored Core evolve and adapt for its ever evolving medium. The legacy of this first game, and in turn the legacy of the series is that of a perfect transference and evolution of the Mecha genre into an interactive medium, and how every single decision from its narrative, to the settings each generation of game will put you in, to the mechanical complications that feed into the every player and developer decision; all of it is to answer and uplift Mecha into a mold that once only non-interactive media had. But in doing so, it also was a creative piece of art that had to reckon with what its genre was, what inspired its inspirations, and the people that made it into what it was- all to be able to bring it to life in a way that wouldn't have been possible without each step the genre took in order to get here. And to me, it is here that the Mecha genre in this particular medium has continued to evolve in parallel to its roots on film and television.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Thank you to whoever takes the time to stop and read this, and I hope you come away with this positively. (having to make this all a series of reblogs is low-key insane) This is the first time I've ever attempted something like this with my Cultural Studies background (that's also on hold right now due to life events). I won't spend too much time harping, this is beyond long enough as it is- but if you liked what I wrote, maybe consider supporting me on Ko-Fi! https://ko-fi.com/theweirdowithkohi This ain't perfect, I can already tell, but I told myself that if I didn't at least try now, then when would I? Times are getting wild and strange in my home country, and if I want to pursue a future away from it doing what I want to do, it's now or never.

Armored Core, Video Games, Mecha: A Cultural Study of A Genre.

In 1997, From Software (フロム・ソフトウェア) released "Armored Core" (アーマード・コア) for the Sony PlayStation. While definitely not the first "Mecha Game" as we'll be referring to ad nauseam in this bizarre, overly long, essay thing of sorts- it more than the rest is arguable the most important. Through its mechanics, story, gameplay, and even setting- everything about Armored Core reinforces that it is the first Mecha IP made for the brand new at the time "video game medium" that fully embodied everything that defines the cultural and historical influences of the modern Mecha Genre, while redefining that genre for the newer medium. To this day, with the most recent release of "Armored Core VI: The Fires of Rubicon" in August of 2023, the series continues to uphold and redefine this legacy. Yet, what does any of that even mean? To make a long story shortened, somewhat long once again; as we know it outside of Japan "Mecha", is a niche of a niche in some cases. Not necessarily that it's unpopular, or doesn't make an insane amount of money (which it is and does in both cases quite often), but in that it is a genre almost entirely defined by its roots in Japan, primarily through various Manga Comics and especially Animated Series. Go Nagai's (永井 豪) "Mazinger Z" (1972) is credited most often as the birth of the genre's identity, most notably as the first real breakout attempt at conceptualizing the idea of a large robot that was controlled through the use of a cockpit within the robot itself. In Go Nagai's words within the book "A Brief History of Japanese Robophilia"; "I wanted to create something different, and I thought it would be interesting to have a robot that you could drive, like a car."

From this idea and the incredible popularity of Mazinger Z, "Robot Anime" (ロボットアニメ) was born, and Go Nagai went on to create more influential works that helped further expand the genre as well as develop this particular flavor as "Super Robot". Now, Super Robot being the first and oldest sub-category to the genre makes what came after works like the aforementioned Mazinger Z and later "Getter Robo" (also from Go Nagai, 1974) fascinating from an outsider to the culture and times of the late 20th Century Japan. Without going too much into a side tangent, shows like Mazinger Z and Getter Robo were the foundation of which everything that would come to pass was built on. Discussing Mazinger Z and Getter Robo with friends and people who love it, however, the one thing that was constantly said was that "They still were and are, monster of the week animated shows", the Super Robots being genuinely not too dissimilar to how super heroes or super powered characters in other cartoons or comics were depicted other than they were both vehicle and the powers themselves. They are still shows about cool/surprising fights with evil monsters or wicked folk- and that's what they really want to be. Not to say there's little under the surface (I would never dare to even humor a claim like that in regards to near any media), but for example- Getter Robo, which introduced the concept of "gattai" (合体), better known as "combination", where these super robots or aspects of them could "combine together" to create a bigger, stronger, or better robot- combined with the introduction of the show's "Getter Rays", the primary antagonists being what are genuinely, dinosaur aliens, Getter Robo has a very clear and distinct theme of "Evolution" that permeates through its entire core- but its also secondary to the actual point of the series from what I've been informed. To quote directly from a friend who's a massive fan and shill for the series: "This is the invention of the wheel, no one has thought to put trims on it," which is not a criticism at all- but I think it's important to especially point that out here and now that this is what the Super Robot era of early Mecha was, really cool and fun ideas for media that wanted to be surprising, fun, and fresh for the early 1970s.

The other thing that was most interesting about the era of Super Robot, was that despite robots- the powers and abilities explored in these series were supernatural or magical in nature; Getter Rays for example is quite literally, human will made manifest- allowing their machines to fire beams of energy, transform their parts, amongst several other things. Some would say it's "on the nose", but frankly it's inspired and has persisted as an idea all the way to present in even modern Mecha that isn't Super Robot. But then, what did come after the Super Robot era of early Mecha? When a genre has only escalated and expanded, going further into the fantastical and erratic energy of its fore-bearers and contemporaries; bigger, brighter, louder- where do we look once we've waged battle with every single light in the sky? When there's no battles left to be fought with aliens, kaiju, or other such monsters that threaten to snuff out our spark, try to tango with the human spirit and its indomitable will- eventually our sights go from the stars above, back to where all battles and conflict are directed at. Each other.

#mecha#armored core#mobile suit gundam#gundam#armored core 6#personal essay#writing#アーマードコア#日本#japan#video games#anime#Did not expect to have to break this post down into reblogs#agghhh#agony#pain#suffering even#Informative experience tho I won't lie#woof okay like I said#This is a big experiment for me#And I'm bound to have gotten things wrong or even misspeak#thank you everyone who took the time to read this all#I will try not to die#This is my first time doing an essay of sorts like this#cultural studies are fun actually#here's hoping this'll help me with getting more funds for uni out of the states#all right thanks y'all

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now, other Mecha games were being made at this time- in fact a great many were being made for the PlayStation as it would turn out. It was here, on this new platform, Mecha games before and even during the PlayStation were incredibly "arcadey" affairs. Side-scrollers that were run and gun shooters with little to no plot, adaptations of other Mecha properties on the big or small screens that regurgitated what one could hardly argue as even calling a "plot synopsis" of the source material it was based on; or were Role-Playing Games (RPGs). Unlike the others mentioned- these were incredibly invested in their narratives, basically playing like extended or playable animes or even novels for some. Many of these aforementioned RPGs of this era blossomed during the PS1's run.

These games were incredible, often thought provoking, and incredible works of narratives in their respective genres- but in quite a few, yet there was a noticeable disconnect at times. In particular, given the nature of the RPG gameplay and narrative loop, there were quite a few games that would divide themselves into the "Combat Scenarios", and the "Narrative Scenarios"- which in many cases had a rather noticeable flaw. Oftentimes, these narrative sections would exclude the Mechs. They may still be mentioned, or even be physically present for select scenes, but in this genre of game- the reality often was that the Mech was the primary method of gameplay, but it was the pilots of these mechs, and the people both outside and within them, that were the focus of the story. Which there isn't a problem with, many games that fall underneath this category are genuinely genre defining, and it was accurate to how Mecha as a genre was in the realm of other mediums. But, there was still that nagging thought at the back of some folks minds.

"This game is really fun, but I really am here to play the Mecha parts." There hadn't really been a Mecha piece of media that was able to cross the barrier between the pilot's story and the Mecha's presence. In some cases, games only heightened that separation, creating long periods of time between the narrative that was happening, and when it was time to suit back up in the cockpit and get to work. The point being that, there were many games that had Mechs in them before now, and new stories told within the Mecha genre in video games were popping up- then came Armored Core.

Armored Core was not a game that featured Mecha, it is Mecha. To its very core. There are no human models in this game, something that would be a very prevalent feature in almost every future game going forward, you only ever see through the eyes of the titular "Armored Core" (AC) when you're engaged in combat, or through the in-universe inspired menu User Interface for the specific purpose of modifying your AC and accepting Jobs to go out. You are not a soldier for a nation, you're not fighting a war for freedom, you're not even really a character proper- you are an unnamed, faceless, voiceless mercenary. You are a Raven. A Freelancer who takes jobs for any and all corporations (Chrome and Murakumo Millennium in this game respectively) that have money to offer. Your reasons for falling into this line of work, are entirely your own as the player. You may not have the ability to talk, but you're free to act as you see fit- and overwhelming firepower speaks louder than words ever could. Earth has suffered catastrophe after catastrophe that has forced the remnants of humanity to hide underground, while on the surface, corporations employ mercenaries to fight their battles for them vying for total control over what remains in an endless, stagnant tug of war waged between each other. Every tragedy is an opportunity for business, and with pilots that only show loyalty to wherever the money flows- opportunity is everywhere to those that can silence their conscience. Your missions include, but are certainly not limited to: Attacking protestors in cold blood, sabotaging rival companies infrastructure and projects, policing areas of interest to the corporations, targeting other Ravens who've worn out their uses to the powers that be, disrupting attempts to break the status quo with extreme prejudice, etc. It doesn't matter where the money comes from or what they ask you to do, all that matters is that they're willing to pay you. And why do you want any of this monetary gain? To better craft your AC. It is key to your survival, and vital to ensuring your continued success when on mission.

It's a dog eat dog world, but Ravens are birds of prey, not content to limp and whimper into that silent goodnight. Money earned helps keep us soaring above the beggars, buying with it new weapons, targeting systems, differing leg parts, arm units, engines, and crafting your personal AC to better play the game. Why would you need or want to keep investing into your AC? Because the game's difficulty is genuinely hard. Death in a mission results in a canonical loss that costs an insane amount of money. Completing a mission sloppily could even result in your mission costs taking up all of the money the mission was supposed to pay for- putting you into debt that can always get worse if not recovered from quickly enough. So then how come it's difficult? Because not just anyone can be an AC pilot, let alone a Raven. Your first taste of combat, upon hitting start and booting up the game- is a Raven's entrance test that the game does not prepare or warn you for. It simply throws you in, and says "If you survive, you're officially a Raven." and tosses you to the other hungry, desperate wolves. If you can't gain your bearings and succeed there, then you literally can't start the game, promptly being sent back to the main menu.

Everything put into Armored Core is done with intent. Customizing your AC is not just searching for the newest parts, but is a choice meant to be taken with intent, taking into account your weight load, your arm strength, your leg type and weight class, the weapons you use, the particulars of your target lock on, deciding between energy weapons and physical, accounting for chassis size, how much power your engine can output and recover from. Even the controls are meant to make you feel like you are maneuvering and piloting a tall, massive humanoid machine that is meant to wage war and cause untold amounts of destruction.

Armored Core, Video Games, Mecha: A Cultural Study of A Genre.

In 1997, From Software (フロム・ソフトウェア) released "Armored Core" (アーマード・コア) for the Sony PlayStation. While definitely not the first "Mecha Game" as we'll be referring to ad nauseam in this bizarre, overly long, essay thing of sorts- it more than the rest is arguable the most important. Through its mechanics, story, gameplay, and even setting- everything about Armored Core reinforces that it is the first Mecha IP made for the brand new at the time "video game medium" that fully embodied everything that defines the cultural and historical influences of the modern Mecha Genre, while redefining that genre for the newer medium. To this day, with the most recent release of "Armored Core VI: The Fires of Rubicon" in August of 2023, the series continues to uphold and redefine this legacy. Yet, what does any of that even mean? To make a long story shortened, somewhat long once again; as we know it outside of Japan "Mecha", is a niche of a niche in some cases. Not necessarily that it's unpopular, or doesn't make an insane amount of money (which it is and does in both cases quite often), but in that it is a genre almost entirely defined by its roots in Japan, primarily through various Manga Comics and especially Animated Series. Go Nagai's (永井 豪) "Mazinger Z" (1972) is credited most often as the birth of the genre's identity, most notably as the first real breakout attempt at conceptualizing the idea of a large robot that was controlled through the use of a cockpit within the robot itself. In Go Nagai's words within the book "A Brief History of Japanese Robophilia"; "I wanted to create something different, and I thought it would be interesting to have a robot that you could drive, like a car."

From this idea and the incredible popularity of Mazinger Z, "Robot Anime" (ロボットアニメ) was born, and Go Nagai went on to create more influential works that helped further expand the genre as well as develop this particular flavor as "Super Robot". Now, Super Robot being the first and oldest sub-category to the genre makes what came after works like the aforementioned Mazinger Z and later "Getter Robo" (also from Go Nagai, 1974) fascinating from an outsider to the culture and times of the late 20th Century Japan. Without going too much into a side tangent, shows like Mazinger Z and Getter Robo were the foundation of which everything that would come to pass was built on. Discussing Mazinger Z and Getter Robo with friends and people who love it, however, the one thing that was constantly said was that "They still were and are, monster of the week animated shows", the Super Robots being genuinely not too dissimilar to how super heroes or super powered characters in other cartoons or comics were depicted other than they were both vehicle and the powers themselves. They are still shows about cool/surprising fights with evil monsters or wicked folk- and that's what they really want to be. Not to say there's little under the surface (I would never dare to even humor a claim like that in regards to near any media), but for example- Getter Robo, which introduced the concept of "gattai" (合体), better known as "combination", where these super robots or aspects of them could "combine together" to create a bigger, stronger, or better robot- combined with the introduction of the show's "Getter Rays", the primary antagonists being what are genuinely, dinosaur aliens, Getter Robo has a very clear and distinct theme of "Evolution" that permeates through its entire core- but its also secondary to the actual point of the series from what I've been informed. To quote directly from a friend who's a massive fan and shill for the series: "This is the invention of the wheel, no one has thought to put trims on it," which is not a criticism at all- but I think it's important to especially point that out here and now that this is what the Super Robot era of early Mecha was, really cool and fun ideas for media that wanted to be surprising, fun, and fresh for the early 1970s.

The other thing that was most interesting about the era of Super Robot, was that despite robots- the powers and abilities explored in these series were supernatural or magical in nature; Getter Rays for example is quite literally, human will made manifest- allowing their machines to fire beams of energy, transform their parts, amongst several other things. Some would say it's "on the nose", but frankly it's inspired and has persisted as an idea all the way to present in even modern Mecha that isn't Super Robot. But then, what did come after the Super Robot era of early Mecha? When a genre has only escalated and expanded, going further into the fantastical and erratic energy of its fore-bearers and contemporaries; bigger, brighter, louder- where do we look once we've waged battle with every single light in the sky? When there's no battles left to be fought with aliens, kaiju, or other such monsters that threaten to snuff out our spark, try to tango with the human spirit and its indomitable will- eventually our sights go from the stars above, back to where all battles and conflict are directed at. Each other.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

In spite of this, the genie was let out of the bottle folks, and as the saying goes- you only get three wishes, and you can't put the genie back into it. Gundam was as it was then as it is now, as malleable as the genre's name has become here. The influence of the earlier series had completely shifted what people thought about Mecha. Real Robot had established itself not just as a bold, new change to the status quo, it had become the status quo. Later series such as Armored Troop Votoms (1983), Megazone 23 (1985), Mobile Police Patlabor: The Early Days (1988) would; regardless of tone- would be incredibly influenced or fall into the styles set by the Real Robot era. In television. It goes without saying that everything listed here is specifically animated series, many of which were made/born out of the "Bubble Economy" period that gripped Japan in the 1980s. I've neglected to talk about the real world behind the scenes much up until now, because in order to get into the heart of this study, I find it's imperative to understand the origins and trajectory of the Mecha genre, and two massive new shifts that are about to strike it.

At the end of the 1980s, that Bubble Economy that had so much money flowing in and out of Japan, helping in the production of many shows, manga, jobs, trade- it popped. The results of which are genuinely so great and vast that words almost fail to do it justice. I don't mean to make this subject light, but for the cliff notes version told succinctly: Jobs were drying up left and right, the value of the yen was plummeting, all those lucrative opportunities ceased to be- leaving most everyone who were involved now without money, job, and especially purpose. So great was the economic fall out, that the generation emerging or thrust into this aftermath was henceforth dubbed "The Lost Generation of Japan." This brought many of the people stuck in this very long decade plus era in history into self-isolating tendencies, seclusion from the outside world, and this overwhelming feeling that there was nowhere to go and nothing left but to try and make money however you can. Apathy would settle over, and all this bitterness, this detachment from one's self- it would inform the 1990s era of creative works across the spectrum. Many pieces of media from this time were introspective, self reflective of what weighed on the thoughts of the Japanese people during that time.

Chief among these thoughts that would only increase with every passing year in this decade, was the second thing. The fear of rapidly evolving technology. This was during the dawn of the modern Internet as we know it and its rapid spread/encroachment everywhere, Y2K in the back of many culture's minds, and the genuine fear that the more technology advanced, the more we were losing bits and pieces of ourselves to make way for this technological rush. And many, many Japanese media were cued into that fear- especially Mecha. Ruminations on the soul, of what people were willing to forsake or give up to pursue newer and "better" developments, of what could drive people to such an extreme, all these thoughts and so much more are flowing in and out of this genre, and at this point- technology had revealed the power of the newest medium. Video Games had gone from the Atari, to the Arcade and home systems of Nintendo and SEGA, to the pioneering of 3D graphics and the introduction of Sony's PlayStation. Born from its own interesting and troubled history as a failed collaborative project between Sony and Nintendo at the time, the PlayStation was a CD based game console sold cheaper than its direct competition with the power for true 3D graphical power. This bold new console, which was positioning itself as a more mature and in touch with the current era of tech version of Nintendo and SEGA's efforts had spoken to many of the creative heads in the Japanese industry. It would be here, where developer "From Software", finally enters our story.

Armored Core, Video Games, Mecha: A Cultural Study of A Genre.

In 1997, From Software (フロム・ソフトウェア) released "Armored Core" (アーマード・コア) for the Sony PlayStation. While definitely not the first "Mecha Game" as we'll be referring to ad nauseam in this bizarre, overly long, essay thing of sorts- it more than the rest is arguable the most important. Through its mechanics, story, gameplay, and even setting- everything about Armored Core reinforces that it is the first Mecha IP made for the brand new at the time "video game medium" that fully embodied everything that defines the cultural and historical influences of the modern Mecha Genre, while redefining that genre for the newer medium. To this day, with the most recent release of "Armored Core VI: The Fires of Rubicon" in August of 2023, the series continues to uphold and redefine this legacy. Yet, what does any of that even mean? To make a long story shortened, somewhat long once again; as we know it outside of Japan "Mecha", is a niche of a niche in some cases. Not necessarily that it's unpopular, or doesn't make an insane amount of money (which it is and does in both cases quite often), but in that it is a genre almost entirely defined by its roots in Japan, primarily through various Manga Comics and especially Animated Series. Go Nagai's (永井 豪) "Mazinger Z" (1972) is credited most often as the birth of the genre's identity, most notably as the first real breakout attempt at conceptualizing the idea of a large robot that was controlled through the use of a cockpit within the robot itself. In Go Nagai's words within the book "A Brief History of Japanese Robophilia"; "I wanted to create something different, and I thought it would be interesting to have a robot that you could drive, like a car."

From this idea and the incredible popularity of Mazinger Z, "Robot Anime" (ロボットアニメ) was born, and Go Nagai went on to create more influential works that helped further expand the genre as well as develop this particular flavor as "Super Robot". Now, Super Robot being the first and oldest sub-category to the genre makes what came after works like the aforementioned Mazinger Z and later "Getter Robo" (also from Go Nagai, 1974) fascinating from an outsider to the culture and times of the late 20th Century Japan. Without going too much into a side tangent, shows like Mazinger Z and Getter Robo were the foundation of which everything that would come to pass was built on. Discussing Mazinger Z and Getter Robo with friends and people who love it, however, the one thing that was constantly said was that "They still were and are, monster of the week animated shows", the Super Robots being genuinely not too dissimilar to how super heroes or super powered characters in other cartoons or comics were depicted other than they were both vehicle and the powers themselves. They are still shows about cool/surprising fights with evil monsters or wicked folk- and that's what they really want to be. Not to say there's little under the surface (I would never dare to even humor a claim like that in regards to near any media), but for example- Getter Robo, which introduced the concept of "gattai" (合体), better known as "combination", where these super robots or aspects of them could "combine together" to create a bigger, stronger, or better robot- combined with the introduction of the show's "Getter Rays", the primary antagonists being what are genuinely, dinosaur aliens, Getter Robo has a very clear and distinct theme of "Evolution" that permeates through its entire core- but its also secondary to the actual point of the series from what I've been informed. To quote directly from a friend who's a massive fan and shill for the series: "This is the invention of the wheel, no one has thought to put trims on it," which is not a criticism at all- but I think it's important to especially point that out here and now that this is what the Super Robot era of early Mecha was, really cool and fun ideas for media that wanted to be surprising, fun, and fresh for the early 1970s.

The other thing that was most interesting about the era of Super Robot, was that despite robots- the powers and abilities explored in these series were supernatural or magical in nature; Getter Rays for example is quite literally, human will made manifest- allowing their machines to fire beams of energy, transform their parts, amongst several other things. Some would say it's "on the nose", but frankly it's inspired and has persisted as an idea all the way to present in even modern Mecha that isn't Super Robot. But then, what did come after the Super Robot era of early Mecha? When a genre has only escalated and expanded, going further into the fantastical and erratic energy of its fore-bearers and contemporaries; bigger, brighter, louder- where do we look once we've waged battle with every single light in the sky? When there's no battles left to be fought with aliens, kaiju, or other such monsters that threaten to snuff out our spark, try to tango with the human spirit and its indomitable will- eventually our sights go from the stars above, back to where all battles and conflict are directed at. Each other.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The end of the 70s marked a radical, yet thematically resonant, shift in the Mecha genre. "Super Robot" would continue to exist, but it was no longer the face or de-facto example of what is now the modern face of Mecha. There were dark themes in previous works, there were even meditations on violence, war, and conflict as a part of human nature. But these older works, were far more positive about Humanity. People could die, people could be hurt, self sacrifice was always present- but Super Robot depicted a very hopeful and uplifting tone, that in spite of whatever else may come to be- we will always find a way to be more than who were even a few minutes ago, and those themes would stick to Super Robot like glue. It would be those same themes, however, that would be challenged, and pushed to new and different opposing themes. Where once there would be subtext, violence and war were now the overt text. Enter the era of "Real Robot" Mecha. This era was and is defined by all the trappings that are now expected when you even hear the term "Mecha", an emphasis on the Mechs/Robots, how they function, what their roles and purposes are, how they're operated, why they were built, etc. The pilots and machines are no longer powered by magical properties, but a more grounded science fictional blend that trades out more and more of the fantastical (though not entirely), for the practical and probable. And in many of these works, there's one big important distinction between these Mecha compared to the Super Robot ones of old- these are tools of destruction. Piloted weapons of war, comparable to fighter jets and tanks, rather than super heroes. Machines built to kill and intimidate the enemy, who's very presence meant that blood was to be shed. Leading this new era, was the brand new face of the Real Robot era. Mobile Suit Gundam (1978).

It cannot be overstated how much Mobile Suit Gundam shifted the entire genre on its head. But what's interesting to me at least, is that while so much has been tweaked, shifted into different directions, or added onto- the core roots of the genre from the Super Robot era are still in the Real Robot era and persist even to this day. Themes of perseverance, evolution, self-sacrifice, humanity's will power; it's all here and in spades- but the difference is in the angle. Will power is now not a literal super power that can be channeled through the Robot into giant lasers or brand new abilities, but is instead a reflection of the drive behind the pilot's eyes- it's now framed as "how far can that will of yours take you, pilot?" It's fuel to the fire of the human soul- rather than a transformative super power. This is prevalent through everything Real Robot era Mecha kept from its predecessor. It kicked off from what came before, but it also added a kind of grit and level of reality that grounded Mobile Suit Gundam in a way Getter and Mazinger never really aimed for, but you can feel how despite the toning down of scale, Gundam is a proper evolution of those ideas despite how different it appears to be at times. As Gundam continued on, several more series would follow in its example, intentionally or otherwise. Real Robot came to be defined by these more grounded series as opposed to the Super Robot Era. The focus fell onto its pilots, and the trauma that these conflicts required something as terribly frightening as humanoid machines piloted by people with the intent to kill other people. Be it to protect others, for a nation or cause that meant something to them, to be more than who they were, to indulge in baser instincts of violence, or because they find themselves without other options. Being a pilot for this new wave of Mecha media didn't mean being a hero necessarily, in many cases these were just people whose talents conflicted with their wants in many cases.

What this new wave brought in was a critical look at the people in this genre without making them so incredibly fantastical they were bastions and icons for humanity against all evils. Instead, it grounded them, even the more fantastical elements like "New Types", humans who are developing new abilities to adapt to the changes happening in their setting rapidly, are treated like people struggling to come to grips with this realization and what this means for them. The original Gundam also makes sure to end on the same hopeful note that the Super Robot Era of old often embodied, with our main character and pilot able to recognize his newfound family in the crew he'd come to know. In an interview with the magazine "Animerica", the creator of the original Gundam, Yoshiyuki Tomino (富野 喜幸) discussed what went through his and the team's mind as they were creating the series that started it all.

Quote, "The bottom line is, I wanted to have a more realistic robot series– unlike a super robot– where everything is more reality-based, based on a humanoid robot. Right from the beginning, the roots of the mobile suit came from the worker robots that were building the space colonies back then, and they would become more technologically advanced, to the point of becoming a weapon, and that was the whole lineage of the robots I had in mind since the beginning.

So the whole idea, my idea, of trying to have a robot series in space without it becoming a stupid story was based on wanting to make a story and surrounding it with reality–more realistic possibilities was the underlying concept. But please don’t misunderstand me as saying that I ever consider this to be real or possible. It’s just sort of a lie that’s trying to be depicted as reality." End quote. Yet, despite all this, and despite what we have with the eyes of the present day- it may strike some of you as odd that the original Mobile Suit Gundam, the first to kick off this new wave of Real Robot, was seen as a bit of a failure from the powers that be at the time. It was saved by the merchandise. The designs of the Mobile Suits, the Gundam in particular, everything that could be sold- was, and that was always going to be the case. In that same interview, Tomino shared the following which I'm going to put in verbatim as well, as this would go on to explain what would come after Gundam's debut. Quote "Robot shows back then, 23 years ago, were pretty much all Super Robot type shows and needed sponsorship from toy manufacturers. So I got the plan to go through by lying to the toy manufacturers. The whole concept was that a robot that’s 20 meters tall can’t not be a Super Robot. So in those days, taking it the other way, they could not have a TV show with a robot less than 20 meters tall." End quote. Despite having planned for it, and banked on lying to the suits in order to green-light the original series; I don't think anyone could have foreseen just how massive Gundam would become as a franchise. It wasn't immediate, but as Gundam went on, it ended up bouncing back and forth between this intended, realistic tone, showing the reality of what a setting that requires a machine like the Mobile Suit as a weapon would look like- to falling into line with the want from higher ups to "sell more toys". The suits, and many of the targeted demographic just "didn't care about the pilots" or didn't value the stories of the pilots over the cool Mobile Suits and the high action battles that helped define the genre. Interestingly enough, this thought and view would actually persist long, long after the original Gundam series began. From publisher disputes, Corporate interference, and even audience demand in quite a few instances- the consensus for the vocal minority was that they wanted "More Mecha, less human." Exact numbers or percentages are difficult to come across, so do take this generalization with a bit of salt- but keep this notion in the back of your mind. Due to this and just the colossal expansion that rapidly swept up the new face of Mecha, we would get series that walked back or lightened the tone dramatically, series that tried walking the fine line, series that would grossly misunderstand the point and go too far into one direction or the other, and even later Gundam media that fell back into almost being Super Robot rather than Real Robot.

Armored Core, Video Games, Mecha: A Cultural Study of A Genre.

In 1997, From Software (フロム・ソフトウェア) released "Armored Core" (アーマード・コア) for the Sony PlayStation. While definitely not the first "Mecha Game" as we'll be referring to ad nauseam in this bizarre, overly long, essay thing of sorts- it more than the rest is arguable the most important. Through its mechanics, story, gameplay, and even setting- everything about Armored Core reinforces that it is the first Mecha IP made for the brand new at the time "video game medium" that fully embodied everything that defines the cultural and historical influences of the modern Mecha Genre, while redefining that genre for the newer medium. To this day, with the most recent release of "Armored Core VI: The Fires of Rubicon" in August of 2023, the series continues to uphold and redefine this legacy. Yet, what does any of that even mean? To make a long story shortened, somewhat long once again; as we know it outside of Japan "Mecha", is a niche of a niche in some cases. Not necessarily that it's unpopular, or doesn't make an insane amount of money (which it is and does in both cases quite often), but in that it is a genre almost entirely defined by its roots in Japan, primarily through various Manga Comics and especially Animated Series. Go Nagai's (永井 豪) "Mazinger Z" (1972) is credited most often as the birth of the genre's identity, most notably as the first real breakout attempt at conceptualizing the idea of a large robot that was controlled through the use of a cockpit within the robot itself. In Go Nagai's words within the book "A Brief History of Japanese Robophilia"; "I wanted to create something different, and I thought it would be interesting to have a robot that you could drive, like a car."

From this idea and the incredible popularity of Mazinger Z, "Robot Anime" (ロボットアニメ) was born, and Go Nagai went on to create more influential works that helped further expand the genre as well as develop this particular flavor as "Super Robot". Now, Super Robot being the first and oldest sub-category to the genre makes what came after works like the aforementioned Mazinger Z and later "Getter Robo" (also from Go Nagai, 1974) fascinating from an outsider to the culture and times of the late 20th Century Japan. Without going too much into a side tangent, shows like Mazinger Z and Getter Robo were the foundation of which everything that would come to pass was built on. Discussing Mazinger Z and Getter Robo with friends and people who love it, however, the one thing that was constantly said was that "They still were and are, monster of the week animated shows", the Super Robots being genuinely not too dissimilar to how super heroes or super powered characters in other cartoons or comics were depicted other than they were both vehicle and the powers themselves. They are still shows about cool/surprising fights with evil monsters or wicked folk- and that's what they really want to be. Not to say there's little under the surface (I would never dare to even humor a claim like that in regards to near any media), but for example- Getter Robo, which introduced the concept of "gattai" (合体), better known as "combination", where these super robots or aspects of them could "combine together" to create a bigger, stronger, or better robot- combined with the introduction of the show's "Getter Rays", the primary antagonists being what are genuinely, dinosaur aliens, Getter Robo has a very clear and distinct theme of "Evolution" that permeates through its entire core- but its also secondary to the actual point of the series from what I've been informed. To quote directly from a friend who's a massive fan and shill for the series: "This is the invention of the wheel, no one has thought to put trims on it," which is not a criticism at all- but I think it's important to especially point that out here and now that this is what the Super Robot era of early Mecha was, really cool and fun ideas for media that wanted to be surprising, fun, and fresh for the early 1970s.

The other thing that was most interesting about the era of Super Robot, was that despite robots- the powers and abilities explored in these series were supernatural or magical in nature; Getter Rays for example is quite literally, human will made manifest- allowing their machines to fire beams of energy, transform their parts, amongst several other things. Some would say it's "on the nose", but frankly it's inspired and has persisted as an idea all the way to present in even modern Mecha that isn't Super Robot. But then, what did come after the Super Robot era of early Mecha? When a genre has only escalated and expanded, going further into the fantastical and erratic energy of its fore-bearers and contemporaries; bigger, brighter, louder- where do we look once we've waged battle with every single light in the sky? When there's no battles left to be fought with aliens, kaiju, or other such monsters that threaten to snuff out our spark, try to tango with the human spirit and its indomitable will- eventually our sights go from the stars above, back to where all battles and conflict are directed at. Each other.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Armored Core, Video Games, Mecha: A Cultural Study of A Genre.

In 1997, From Software (フロム・ソフトウェア) released "Armored Core" (アーマード・コア) for the Sony PlayStation. While definitely not the first "Mecha Game" as we'll be referring to ad nauseam in this bizarre, overly long, essay thing of sorts- it more than the rest is arguable the most important. Through its mechanics, story, gameplay, and even setting- everything about Armored Core reinforces that it is the first Mecha IP made for the brand new at the time "video game medium" that fully embodied everything that defines the cultural and historical influences of the modern Mecha Genre, while redefining that genre for the newer medium. To this day, with the most recent release of "Armored Core VI: The Fires of Rubicon" in August of 2023, the series continues to uphold and redefine this legacy. Yet, what does any of that even mean?

To make a long story shortened, somewhat long once again; as we know it outside of Japan "Mecha", is a niche of a niche in some cases. Not necessarily that it's unpopular, or doesn't make an insane amount of money (which it is and does in both cases quite often), but in that it is a genre almost entirely defined by its roots in Japan, primarily through various Manga Comics and especially Animated Series. Go Nagai's (永井 豪) "Mazinger Z" (1972) is credited most often as the birth of the genre's identity, most notably as the first real breakout attempt at conceptualizing the idea of a large robot that was controlled through the use of a cockpit within the robot itself. In Go Nagai's words within the book "A Brief History of Japanese Robophilia"; "I wanted to create something different, and I thought it would be interesting to have a robot that you could drive, like a car."

From this idea and the incredible popularity of Mazinger Z, "Robot Anime" (ロボットアニメ) was born, and Go Nagai went on to create more influential works that helped further expand the genre as well as develop this particular flavor as "Super Robot". Now, Super Robot being the first and oldest sub-category to the genre makes what came after works like the aforementioned Mazinger Z and later "Getter Robo" (also from Go Nagai, 1974) fascinating from an outsider to the culture and times of the late 20th Century Japan. Without going too much into a side tangent, shows like Mazinger Z and Getter Robo were the foundation of which everything that would come to pass was built on. Discussing Mazinger Z and Getter Robo with friends and people who love it, however, the one thing that was constantly said was that "They still were and are, monster of the week animated shows", the Super Robots being genuinely not too dissimilar to how super heroes or super powered characters in other cartoons or comics were depicted other than they were both vehicle and the powers themselves. They are still shows about cool/surprising fights with evil monsters or wicked folk- and that's what they really want to be.

Not to say there's little under the surface (I would never dare to even humor a claim like that in regards to near any media), but for example- Getter Robo, which introduced the concept of "gattai" (合体), better known as "combination", where these super robots or aspects of them could "combine together" to create a bigger, stronger, or better robot- combined with the introduction of the show's "Getter Rays", the primary antagonists being what are genuinely, dinosaur aliens, Getter Robo has a very clear and distinct theme of "Evolution" that permeates through its entire core- but its also secondary to the actual point of the series from what I've been informed. To quote directly from a friend who's a massive fan and shill for the series: "This is the invention of the wheel, no one has thought to put trims on it," which is not a criticism at all- but I think it's important to especially point that out here and now that this is what the Super Robot era of early Mecha was, really cool and fun ideas for media that wanted to be surprising, fun, and fresh for the early 1970s.

The other thing that was most interesting about the era of Super Robot, was that despite robots- the powers and abilities explored in these series were supernatural or magical in nature; Getter Rays for example is quite literally, human will made manifest- allowing their machines to fire beams of energy, transform their parts, amongst several other things. Some would say it's "on the nose", but frankly it's inspired and has persisted as an idea all the way to present in even modern Mecha that isn't Super Robot.

But then, what did come after the Super Robot era of early Mecha? When a genre has only escalated and expanded, going further into the fantastical and erratic energy of its fore-bearers and contemporaries; bigger, brighter, louder- where do we look once we've waged battle with every single light in the sky? When there's no battles left to be fought with aliens, kaiju, or other such monsters that threaten to snuff out our spark, try to tango with the human spirit and its indomitable will- eventually our sights go from the stars above, back to where all battles and conflict are directed at.

Each other.

(this post is continued in a series of reblogs, be sure to check them out!)

#mecha#mech#mechs#japan#culture study#essay#writing#armored core#ac#日本#ロボット#レアルロボット#メカ#armored core 6#personal essay#mobile suit gundam#gundam#スパーロボット#Whoof I'm really nervous about this I'll be honest#The Super Robot segment is definitely going to be the weakest part#As admittedly it's the one I'm least informed on#I'm eternally grateful for my friends that are into the roots of the genre#I'm also very open to constructive criticism#this post might be stuck in eternal edit checks but HEY I POSTED IT#which is more than I thought I would#woof wow okay right#thank you everyone#Will see how this pans out#I think the first update will just be linking my sources should tumblr allow me to add anymore to this wall of text and funny gifs#now I'm just yapping

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

245K notes

·

View notes

Text

ninja wisdom from super dragon ninja ryu hayabusa

25K notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is Blue Eye Samurai 1 year anniversary ✧\(>o<)ノ✧ I just love this series, it made me go back to draw and write and in general it made my creative block go away. That's all ✨✨✨

I love you Mizu

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

She has a very supportive and understanding boyfriend who believes in her and does not kinkshame.

2K notes

·

View notes