Text

Updates

Hey everyone!

First of all, I want to say thank you all for sending in so many questions and messages! Unfortunately, I have a very busy life and lots and lots of pending questions, and as I am only one person with little free time, I unfortunately cannot tackle every single message in my inbox, as much as I would like to. There have been a lot piling up, and so for the sake of organization, I am going to clear my inbox and start fresh. Feel free to keep sending in questions, and if you have sent a question before and you didn’t receive an answer before, you may also feel free to send it again, and I will answer it if and when I see it.

Secondly, I would also like to say that I have created a Ko-fi. I started this blog with the intent of giving advice and resources to writers of all kinds, without a financial barrier. I firmly believe that helping others should be free, but I also have learned that in order to give the answers and posts I make all the attention and care I like to give them, it takes a lot of time and a lot of energy that I frankly cannot always afford. Again, I don’t intend to charge for my answers, but if you find my blog helpful and you are in a good financial situation, I appreciate any donations to help keep this blog running, so that I can continue putting in my best effort and my time into making these answer as thorough as I can.

The Ko-fi has a link on my blog and will occasionally be linked on posts, as well as here. Thanks all for your understanding.

Finally, I am devising plans for more original content, a tags list, and potentially other fun updates and surprises throughout the year.

Thank you all so much and I hope you had a fantastic summer, everyone!

- Penemue

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any tips about writing a character who has survivor’s guilt?? (To give a little context, the character in question unwillingly killed a close compatriot of hers)

Wow, very sad!

I recently wrote a character with survivor’s guilt for a very different situation, but it was a very new and interesting experience for me. Actually, it took me a while to realize that he even had it, funnily enough. When I was writing scenes in which he was involved, or writing chapters from his perspective, everything came out a lot angrier and more intense than I expected. Halfway through the story, I finally realized that he was lashing out due to his grief and pain.

That doesn’t mean that is what survivor’s guilt always looks like, however. In fact, I think that guilt and grief can be tied very well together, and look very similar. But the reaction shown is going to differ depending on the character. For my character, a strong-willed person with a bit of a temper already and a lot of bitterness, anger was a natural reaction to what he was feeling. To him, he was angry that this terrible thing happened, and that he lost so much because of it, and that now he had to keep on living with all that loss when it might have been easier to just die along with his friends.

If you are familiar with the stages of grief:

A lot of those emotions and symptoms are very applicable to survivor’s guilt. Emotional outbursts, panic, denial, shock, anger, as well as parts of the recovery can all be a part of what they are dealing with.

Think specifically about your character, and what makes the most sense for them. They may not go through every point on the graph. Maybe, if they are a quieter type of person, they just feel numbness, or denial, or despair. Maybe, if they are more tempestuous like my character was, they lash out. Perhaps they feel panic, or get paranoid and put up extreme precautions to ensure that nothing like that ever happens again, to the point where things get a little out of control. Maybe they blame themselves, feeling a lot of self-hatred or going over the scene over and over in their minds and trying to figure out what they could have done differently.

Even though your character’s killing of this person was unwilling, they may still blame themselves, or think “I should have been stronger/better/smarter” etc, or think “If I have done this differently, then we never would have been in this situation”, even if realistically there was no way of knowing what was going to happen.

Another common reaction is the “It should have been me” reaction. The survivor may feel that the person or people who died were better people than themselves, or that they had more to live for, or even that their actions were what got them into trouble in the first place and that they should have paid the price.

Remember that their guilt will tell them to think terrible things, even if they aren’t true and aren’t realistic. The mind will go to great lengths to blame itself when it is entrenched in such terrible levels of despair- even if there was logically nothing they could have done, guilt will always tell them that they should have done better.

Another thing to remember is that they will likely be experiencing grief at the same time. After all, they just lost someone close to them. That is an entire presence that will be forever missing from their lives, and to make it worse, they feel like it’s their fault. It’s okay if sometimes they just miss this person, and that’s enough to deal with.

Finally, don’t neglect the recovery side of the graph. With support, your character can learn to cope with what happened. Any one of the things listed above can be catalysts for a new phase for your character, emotionally. For my character, it was reassurance and support from his friends, particularly the introduction of a new character, who had a very positive influence. Your character may still carry the loss and the guilt with them, but it was will someday be a lighter burden.

Six Tips for Handling Survivor Guilt

Understanding Survivor Guilt

PTSD

Stages of Grief

- Penemue

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

I know it's supposed to be subjective, but... how do I know if my poetry is any good?

Honestly, how do we know if anything we create is really any good?

The best thing we can do is to forget about trying to be “good” and just write whatever words you want to write, just let your feelings flow. There is always time to edit and review later, but the important part is speaking your truth and passion.

Poetry, I have to admit, has always been a struggle for me, too. It didn’t come as easily to me as many other forms of writing do. Don’t get me wrong, I love to read it. Memorizing and reciting poems is one of my favorite ways of relaxing when I’m too stressed. But I have never had the knack for writing it. Many workshops and classes later, I still can’t say it is my strongest point, but I did learn a lot, and the lesson above, as silly as it might sound, was the most important lesson I learned from it. I always worried too much about the particulars, and whether it was good in a technical way, and that made it much more disjointed and forced and awkward.

One particular memory that stands out to me from one of my classes was when, halfway through the course, I felt frustrated with all the critiquing and was really starting to give up, thinking I was never going to understand it. On my next poem, I decide to write something completely cryptic, a message just for myself, no holding back or worrying what the class would say. In fact, I wrote a poem about my own deepest secret, except I used code words and private jokes and things only I would know to make sure it was cryptic as possible, intentionally trying to make it as cryptic as possible, so that it didn’t matter if no one else understood it this time, as long as I did. And I was really proud of it, because when I read it, it made sense to me, and I went into that workshop, I fully expected for it to be criticized harshly, and to fail the assignment.

The actual reaction was completely different, however. People actually really liked it. Even though it was full of personal references and coded language, it still was successful, because even though it used code words, the message and emotions still were present, and that is what came across when people read it, because for once, I wasn’t worried about what other people had to say- that poem was wholly mine. But the most shocking thing to me is when a classmate told me even though they didn’t know what the poem was about, they cried while reading it. That completely blew my mind. To me that shows, no matter what you put out into the word, if your heart is in it, someone else will connect with it, maybe even more deeply than you did.

After that, I became a lot less restrained in my future works, and became a lot more successful in the class than I thought I would be, and now, while I still don’t necessarily like writing poetry, I appreciate it a lot more.

Now of course, it is still good to study poetry, to understand rhyme and rhythm and so on, but think of all those complicated terms not as “rules” that determine whether or not a poem is objectively good, but as tools that are meant to help you express your message more creatively, not to control it.

On that note, I’m gonna leave you with a few links to help out with the technical stuff, but my main advice to you is to just write it all down, unrestrained. Write lots of poems. Write them on a whim, or write them thoughtfully over time, just write fearlessly. And don’t be afraid to read other poems too. Not just the “great” classic writers, but everybody’s poetry. Note all the ways people have of expressing themselves, and how very different the world of poetry is- no two are alike, and yet all are special to someone.

Common Poetry Terms

36 Poetry Writing Tips

100 Inspiring Sites for Poets

Famous Poets and Poems

- Penemue

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

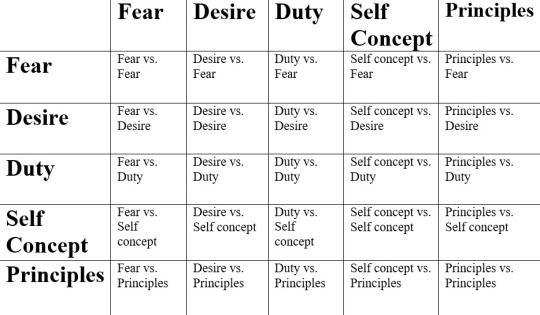

Can I ask about the idea of the types of inner conflict ideas (desire, duty, self-concept, principles, fear, etc.) and explain them I guess? I’m a bit confused on them but I think they’ll be excellent to use in developing inner conflict.

Yes! So, the traits typically used to create inner conflict in a character, such as the ones you listed, are things that you should generally know about your character to make them as well-rounded and realistic as possible. “Inner conflict” happens when two of those traits clash. We can look at all of those in greater detail and look at examples of how you can pit them against each other.

Desire: Your character’s positive motivation, the thing that they want the most, the goal they are trying to achieve.

Duty: The responsibilities that they have, whether is is to their family, friends, their job, their religion, or whatever else they might be involved in.

Self Concept: The image one has of oneself. Keep in mind this is how they see themselves, not necessarily the truth of how they actually are or how others see them.

Fear: The negative motivator, the things your character most desperately wants to avoid.

Principles: A fundamental belief that your character or system of beliefs that your character holds as truth.

Once you have each of these tings established for your character, you can create inner conflict by sort of pitting them against each other. Sometimes, when you are developing these aspects, you find that some of them might naturally be at odds for each other.

Some examples- your character wants something desperately (desire) but in order to get it, they have to face down something that terrifies them (fear). Now it becomes a matter of which trait is stronger than the other- the desire or the fear.

Another example- duty vs. principles. The character has a responsibility to their job (duty), but then they are asked to do something that goes against this own personal values (principles.) They must then decide which is more important to them: completing their duty, or standing their ground on their principles.

One final example- self concept vs. desire. The character believes themselves to be of a certain type of person (self concept), but they take interest in something that is outside the sphere of what they thing is normal for that group (desire).

These are not the only combinations, or the only traits that work for inner conflict. In fact, using cornerstones and pillars can help develop your character and figure out what might be a good inner conflict for your character.

Also, you can create conflict by putting two of the same things against each other- for example, your character could have two conflicting desires, and then have to decide which one they want more.

Hope that clarifies things!

- Penemue

226 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey there! Itsa me again! I was wondering if you could help me with a problem in my story. I write about faeries and most of them speak extremely formally. But I don't know how to write extremely formal speech??

Hey hey, welcome back!

Formal speech can differ depending on time period and setting, but here are a few general tips that I generally find is enough to fake it til you make it.

1. Don’t use contractions. Ditch your didn’ts, don’ts, it’s, and so on and replace them with I did not, do not, it is.

2. Spice up the vocab a little. That doesn’t mean you need to use a thesaurus for every other word. Too many long or obscure words can be very annoying for the reader. But do use a more elevated lexicon for your Fair Folk than the one you use for your human characters.

3. Don’t use slang terms, nicknames, or shortened versions of things. Just be straightforward and specific. Also, don’t use cut of sentences like “tell you later” or “see you soon.” Instead, write out the full “I will tell you later” or “I will see you soon.”

4. Indicate possible status. Think about how you talk differently to your friends than how you talk to your teacher. Use the appropriate titles and indicate authority depending on how they are talking to.

5. Up the polite language. Don’t say “can you do this for me?” But do say “Might you do this for me please” or “May I ask this of you?”

Basically, imagine you are doing a job interview or writing a school essay. Another very important thing to remember about the fae is that they never lie. They can be manipulative and deceptive and are very clever and specific with their wording, but they never lie. Be very careful with your wording when you write dialogue for them.

- Penemue

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello☺️ I’m writing a story about a girl whose parents haven’t ever cared about her and basically left her, but at some point her father (rich as hell) seeks her out to ask her to come with him “home”. She is not stupid or naïve or desperate... she won’t just say “yeah ok why not let’s go”. She hasn’t seen him in years and her mother left her as well, she can’t really trust people???? But the plot is based on her taking the offer!! Help me please🙏🏻

Hello!

It seems to me what your characters lack is proper motivation. Remember that your characters must always want something, no matter what it is. I would ask yourself what this girl wants more than anything or what she is hoping to achieve, and how that may tie in to her father’s presence in her life. And then, do the same thing for the father. What is his reasoning for seeking her out so suddenly after having not wanted anything to do with her before?

Possible motivations for the daughter could be curiosity about her father, or possibly she has been struggling on her own and needs a new home more desperately than she lets on, or maybe her life is stuck in a rut and she needs a change anyway, or maybe he has something she wants, be it an object, or possibly answers to something she wants to know. Even after she takes him up on the offer, she can still show her hesitancy and lack of trust through her interactions with him, refusing gifts, etc, generally never letting her guard down.

As for the father- he could also possibly want something that she has. Or, there could have been factors that the daughter didn’t know about that kept them apart all this time. Or maybe he wants something else, but taking his daughter in is a condition of achieving that other goal. His attitude and feelings towards her can show a lot about the nature of the situation.

To me that seems to be the clearest solution. Figure out what your characters want. What are they hoping to achieve? How can they use each other to achieve that?

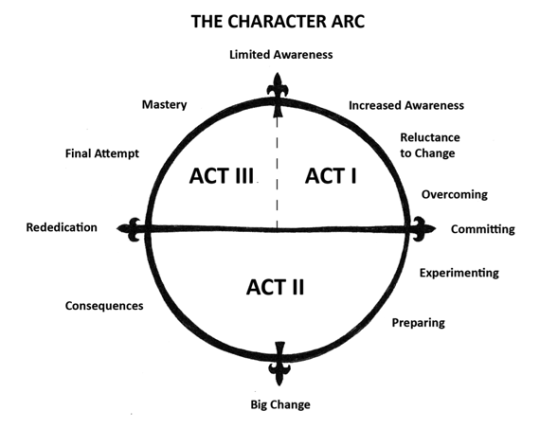

To help you a little further, here and here are a couple of questions referring to the ;Vonnegut’ rule of motivation, as well as a post about character arcs.

-Penemue

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I'm writing my first fan fiction and was wondering if I should wait until the whole story is actually finished to start posting it? Or should I just post right after a chapter is finished? Thank you for your time!

Hi!

Interesting question. I have never actually written a fan fiction before, so I wouldn’t know which I would prefer, either. I would weigh the pros and cons of both options and see which way suits you the best.

Pros of waiting until the story is finished:

Gives you much more opportunity to edit

You can change the plot around if you find something you wrote before doesn’t work for you anymore

You can see the project as a whole, which helps keep it consistent/cohesive

You can take it in any direction you want without feeling like you have to change things to fit what your readers want

Cons:

You don’t get any feedback

You could lost interest or motivation and never complete it

You may find you could have used some fresh inspiration or compliments from a reader

It’s hard to feel a sense of accomplishment until it is done

It’s easier to slack on deadlines

Pros of posting it update by update:

You can get feedback as you go and adapt the upcoming chapters as necessary

Having readers who are waiting for an update can help motivate you to complete the project

Readers may also have good ideas to help inspire you

It can help you feel organized and give you a sense of accomplishment

You can establish clear goals and deadlines more easily

Cons:

Less of a chance to edit

You can’t really go back and change things later if you change your mind

You may feel pressured if you know people are waiting on you to update it, which may influence your writing

You may worry too much about the opinions of others, and change your direction away from what you actually wanted to do

You may feel pressured by goals or deadlines

I’m sure there is more, but those are just some general thoughts I would consider carefully. The good news is, though, that you can always change your mind. You could post a few chapters and then decide that you want to wait and write the rest of the story, or you could start writing the whole thing and then decide to post it in pieces at a time.

Fanfic writers, which do you prefer? Any advice?

-Penemue

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I have the greatest of questions, I have this partially deaf character whose kind of a genius. I want him to talk through notebooks but I noticed this little thing is making my dialogs quite hard for me to write and quite hard for everyone to follow. Any ideas? The notebook thing can be changed, I just need some help with how to handle the dissability in a functional way while writing. Thank you for your attention, you are great! Also, sorry for the bad english lol

Hello!

Interestingly enough, I have written a similar character. I did a lot of research before writing the character and the main piece of advice I would give to you is simply to not spend too much time describing the character’s writing, and to write it more or less like the dialogue of any other character.

The first time this character is introduced is the point where you would mention that he writes down what he wants to say. After that, simply write the dialogue basically the same, with quotation marks and all, except instead of saying “he said” you might just say “he wrote.”

You can also think of the ways one can convey emotion through writing similar to how it can be conveyed through tone of voice. When people are excited, they often talk faster. The same could be said for writing. If he has something important that he wants to say very quickly, he may also write faster. You can also use facial and body language as descriptors.

The same could be said if your character is signing. Many times when non-disabled people are writing a story featuring disabled characters, they tend to overthink it, and go into more detail than they really need to. Doing that can be alienating for your character and make dialogue harder than it needs to be.

I would also recommend researching how to write deaf/HoH characters from people who are deaf or hard of hearing, so that your portrayal can be accurate and well represented.

Just by searching in the tags, I did find some guides written by deaf/HoH people to give you advice.

deafmic tips for writing a deaf/hoh character

How to Write Deaf/Hoh Characters

Resources for Writing Deaf/Hoh Characters

FAQ on Writing Signed Language

Those are just a few I found doing a quick tumblr search!

- Penemue

52 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I've been writing for awhile now, and I've noticed my sentence structure (when not in dialogue) is very same-y because of the structure I use to describe the character(s) and/or scene(s) in question. Any helpful tips or tricks to help me with the dynamics of my writing?

Hi!

I’m not entirely certain what you mean, or really what your specific problem is, without seeing it, but I can give you some general tips on sentence structure and flow.

Here is an ask I answered previously on story flow that goes over how to structure sentences, paragraphs, and conceptual flow. One thing I would particularly point out for you is the section on sentence flow. I would also not recommend using any particular ‘sentence structure’ continually, as it just leads to the problem you seem to be having, of all the sentences starting to seem rather the same.

I can also give you some general notes and tips on sentence structure!

1. Vary how you begin each sentence. If you use a similar opening repeatedly, it can be very distracting to the reader. Some examples of habits writers sometimes develops with the sentence starter including overusing commas, or overusing pronouns. For example:

Overused pronouns: “She stood on the shore. She watched the ship sail away without her. She felt empty at the sight of it. She wished she could be watching the shoreline disappear from aboard the deck, not the other way around.”

Varied beginning: “As she stood on the shore, the ship sailed away without her. The sight of it made her feel empty. In her heart she knew she would have given anything to be watching the shoreline disappear from the deck, not the other way around.”

Breaking the pronoun habit forces you to change to viewpoint a little and sometimes helps bring in more details to make the sentence work. An overuse of commas would be similar. If you frequently start sentences with a word or phrase followed be a comma and then the rest of the sentence, (i.e. “suddenly,” or “All of a sudden,”) you need to try varying your beginnings, or having sentences of different lengths.

2. Vary sentence lengths. There is a very elegant example of the importance of varying sentence lengths on the post linked above. As a general rule, shorter sentences are more direct and driven, which means they have greater impact when used for action or to state a clear point. Shorter sentences also make the scene go faster, which can help make something like an action/fighting scene feel more intense and quick-paced. Longer sentences are better for description, or for slowing down the pace of the scene.

However, keep in mind that it’s best to have a good variance of both. If your sentences are consistently too long, it becomes very boring and hard to read, if they are always short, it can feel choppy. You should use short sentences to emphasize or make a point, and long sentences to tell a story.

3. Don’t make it a checklist. You don’t need to have an action, a piece of description, and a piece of dialogue in every sentence. By forcing too much information into each sentence, you are probably adding a lot of unnecessary information that makes the reading monotonous. Mention only what is most important at that moment.

4. Read. Reading widely can help you distinguish the individual styles and unique devices writers employ to vary their structures. I would even recommend making it an exercise to pay particular attention to sentence structure in a book you enjoy and make note of the devices and habits the author used.

What types of sentences did they use in an action sequence? What type for a slower scene? What bits of description stood out to you? Were there any uncommon or unusual elements that added to the flow of the story?

5. Create an effect: By this, I refer to those one-liners that stick with us. I have seen authors place an unusual sentence in a such a unique way, it creates drama and impact. For example, using a one word sentence places enormous emphasis on one very important thing, that can be used to bring clarity and focus. Similarly, using a long list without commas can create a rambling effect that can make confusion or disorientation feel more real.

6. Vary your vocabulary! Learning new words opens up surprising doors and actually goes a long way. Using different vocab can change the feeling of a scene and help restructure your sentences so that they feel less repetitive.

Those are just a few quick ideas. I highly recommend studying different types of scenes you have read before and noting how the author created the effect that they did to make the scene successful.

Penemue

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Strong Female Characters”

Hi everyone! In honor of International Woman’s Day, I wanted to make an official post on female characters. I answered this pretty thoroughly on an ask before, but I decided to put it on its own post as well.

The problem that usually occurs with ‘strong female characters’ is that the word ‘strong’ is taken to mean something it doesn’t. Meaning, a lot of people assume that in order to be ‘strong’, a female character has to be physically or even mentally strong, when that’s not necessarily what that means. Bad@$$ characters can be strong characters, and strong characters can be bad@$$, but the two things are not synonymous.

This might get a little lengthy.

What is a “strong female” character?

A character is “strong” when they are complex. This means that they have great and admirable traits as well as things that they struggle with, flaws and mistakes and temptations. They are like a real person, which is what you want with any character you want, but most especially with your protagonist and other significant characters.

One of the reasons writers often fumble with the concept of ‘strong female characters’ is because of the distinct lack of them in the past of popular literature. Due to the way that society has viewed women, women were often used primarily as romantic interests, or mothers, or other traditional ‘womanly roles.’ Even stories that are popular today can be guilty of this- for example Arwen from Lord of the Rings is a popular character, but we don’t really know much about her other than that she is capable and beautiful and Aragorn’s love interest. She is almost never used in the story, and when she was, it was in relation to Aragorn.

Because of this historical lack of ‘strong female characters’, writers today have become rather obsessed with tipping the scales, to the point where the tables turned far too much the other way, resulting in the “YA strong female character” we all know today. In an effort to combat the ‘soft and gentle’ tropes of the past, writers now make woman who are essentially flawless. They are beautiful, and everyone loves them, and they might fight and defend themselves, badasses who kick butt and look good doing it… but not much more.

Even their flaws tend to be tailored to being admirable. For example, being “too selfless”, “too modest”, or “clumsy”- usually they mean “clumsy in a cute way.”

Again, it’s okay for your character to be athletic. They can be desirable. They can also be a vampire and the chosen one. But if they are not well-written from every angle, flawed in some deep way, they are simply not strong.

Traits of a YA Strong Female Character:

1. Doesn’t have arc/doesn’t grow: Many “YA strong” girls start the story already perfect. They are beautiful, smart, funny, and badass and they lead everyone through their arcs throughout the story- yet they themselves never grow… because there’s no where for them to go.

2. Everyone Loves Her: Everyone loves or respects or fears this girl. The Brooding Male Character, the Comic Relief guy, everyone. Even if they don’t at first, they come to like her later once they Realize How Awesome She Is. Even the antagonists come to fear her in her power. She’s just Too Cool.

3. Love Interest: It’s okay for your strong girl to have a love interest. That’s totally cool! But make sure that’s not all the story is. If it’s a dystopian universe, make sure her priorities are in order, for example. Readers get frustrated when the government is brutally killing people but all your protagonist can think of is her LI. Life exists outside of love.

4. Woman-ness: In a previous post I mentioned in one of my previous posts that strong characters must have a quirk. Another red flag in the Strong Female Character problem is when the quirk is simply the fact that she is a woman. Saying she’s quirky because she’s a woman but she fights/leads/takes on a role that is traditionally masculine is not really a quirk. It may be unusual in her world, but that’s a quirk of the world, not the character.

5. Great Flaws: As mentioned above, YA Strong Females typically have flaws that can really be spun back around into strengths. Often writers are afraid that people won’t like their girls if they are flawed. Don’t be afraid. Make her cranky. Make her bad at fighting. Make her ugly. No one in life is utterly flawless, not even your favorite people in the world. It’s what makes us all complex and interesting. So make sure to test your flaws- can this be seen as desirable or admirable in any way? Is the trait described as “too {good trait}” or “{good trait} to a fault?” Then maybe you need to try a few more.

In Summary: Write her realistically. Gives her flaws. If you can’t imagine a person like this in real life, if you can’t imagine yourself like this, then she isn’t strong.

As for writing complex characters in general…

Cornerstones and Foundations are a good place to start. And there will be more out in the future.

This is a common problem for writers to struggle with. Almost everybody ends up with a flat, “perfect” character sometimes. Just remember to write them as a realistically as possible. Don’t get too caught up in the kick-ass tropes.

~ Penemue

903 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character Arcs Continued

Make sure you remember part one (x)

Please Note: This is absolutely not the only version of the character arc that you will ever see. There are certainly different versions where the points vary, but I chose to explain this one as it has points in common with many others and it is easy to follow.

Every important character should have an arc that carries alongside the plot. This adds a layer of complexity and shows growth in your character. Though roles and patterns are made to be broken, one of the most accepted structures for a character arc looks something like this. Let’s break it down.

Keep reading

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Character Arcs

From Wikipedia:

“A character arc is the transformation or inner journey[1] of a character over the course of a story. If a story has a character arc, the character begins as one sort of person and gradually transforms into a different sort of person in response to changing developments in the story. Since the change is often substantive and in the opposite direction, the geometric term arc is often used to describe the sweeping change.”

Character arcs can go a number of ways, the key terms being the positive, negative, and flat arcs.

You’re going to want to remember your pillars and cornerstones for this. Your character’s traits drive the direction of the plot.

Positive Arcs: In the positive arc, your character starts out one way, and then ends up a better person by the end. That is positive character development. Through all the trials and tribulations, your character has adapted to their struggles and come out the other end stronger than before, and has grown as a person. As I like to say, what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger in this arc.

Negative Arcs: This would be the opposite. Your character starts out with some flaw, and by the end, it still remains, or even gets worse. The trials and tribulations have only hardened them, made them more bitter, or sent them deeper into the anger or hatred that fuels them.

At some point, your character has a choice to make. It can be the choice between forgiveness, or holding on to anger. The choice between ruthlessness and mercy, and so on. There can be many little actions leading up to that- mistakes and decisions of varying degrees- but eventually, there will be a pivotal moment where the character either proves their heroes, or proves themselves to be irredeemable.

I’m a firm believer that everyone chooses their own path.

So what’s a flat character arc?

Kinda contradictory, first of all. It something is flat, it’s not exactly an arc, is it? Anyway. It is what you might guess… the character doesn’t really grow one way or another. Usually, this means the character starts off basically ready for the quest before them. They’re not perfect people, of course. No one is. But they are more than capable for what’s at hand, and thus, don’t noticeably grow throughout the story. Most minor characters have a flat arc, mostly because they aren’t the focus, and arcs take time and development. Oftentimes, flat arc characters will actually be catalysts for changes in the story, instead of being changed by their experiences, unlike major characters, who do both.

That is a quick glance at your basic character arcs. Arcs are actually a very complex piece of the story, and we’ll take a closer look at them later. For now, I just want to give you a quick idea in preparation for my upcoming Death series.

Stay tuned,and keep writing.

Edit: Good job staying tuned, here’s part two.

Thanks guys!

-Penemue

481 notes

·

View notes

Text

Should I Kill My Character?

Character deaths is not a matter to take lightly. The loss of a character impacts the entire story from then on. Sometimes It can be hard to tell if a character death is necessary, or if you’re getting carried away by the potential tragedy of it all. Ultimately, character death is something that you feel in your writer instincts. But sometimes it’s a little hard to identify that feeling, so here are a few guidelines for you to figure it out through your story.

-Does this death advance the plot?-Does this death motivate or increase develop in other characters?

-Is this the last step in fulfilling the character’s arc? Perhaps it is simply time. Maybe they have lived the life they wanted, or achieved what they could, and the only thing they have left to give is their life.

-Has this character become extraneous? Side characters often have a minimal role in the plot, and once they complete it, they just become another person to keep track of.

-Does this death emphasize the theme? The manner of death matters with this one. For example, in a dystopian world where there is much senseless cruelty, a brutal murder can emphasize the unjust world your characters live in, where life is taken as a power tool. In a story where the theme is love or sacrifice, a character giving themselves up also emphasizes the theme- love gives us the strength to do things we’d normally fear.

- Does it add realism? Death is inevitable, and sometimes it shocks us at the most cruel or unexpected times. Sometimes it just happens and there is nothing we can do to stop it. However, this reason cannot be the only justification for the death of a character.

-Is this death satisfying? Perhaps your character has done something terrible, and their death is the only suitable recompense. Or, perhaps your more innocent character as suffered a lot, and death will be naught but a well deserved rest.

Now for some warnings.

Shock value/ “Sad value”: Sometimes the idea of a death is so gruesome or so tragic, you can’t help but feel a surge of shock or despair just thinking about it. Ultimately, yes, you do want readers to feel something when they read a scene. Deaths that have no real meaning to them or occur just because that character is beloved are frankly very annoying to the reader. To the audience, it can look like the writer is taking a beloved character for granted and using their death as a way to cause uproar, and it can seem very lazy. Deaths that are used for realism and theme mentioned above are the most susceptible to this trope. Be careful, and make sure that neither of those is the only reason.

Extraneous Characters: Make sure you are not using death as an easy tool to remove everyone you don’t want anymore, or else it will lose its meaning. It’s almost like the boy who cried wolf- if it happens too many times, no one panics any more.

When all else fails, try writing it. Does it fit in without much force? Are there natural repercussions that flow forward from it? How do the other characters react? Are there times in the future where that character could really add value? Maybe a lot of times? That might be a sign that they still have a lot left to do.

Keep in tune with your story, and try to understand what your characters are telling you. Remember that if a character is complex enough, they will often drive their own events.

~ Penemue

539 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! Do you have any advice on writing strong female characters? I just don't want to fall into the "YA strong female character" that has honestly become a cliche. Or better: how to write strong characters in general, please

Hello!

The problem that usually occurs with ‘strong female characters’ is that the word ‘strong’ is taken to mean something it doesn’t. Meaning, a lot of people assume that in order to be ‘strong’, a female character has to be physically or even mentally strong, when that’s not necessarily what that means. Bad@$$ characters can be strong characters, and strong characters can be bad@$$, but the two things are not synonymous.

This might get a little lengthy.

Keep reading

169 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Love the world? Write about it. Hate the world? Write a new one.

John Maurer (via thewritersguardianangel)

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fundamentals of Character Development, Part 2: Pillars

Hello everyone, it’s Penemue. Sorry that it took so long to put up the next part like I promised. I had some things I had to escape. Anyway, in part one, we talked about the cornerstone foundations! Now, it’s time for part two- the pillars.

Well, writers, let’s jump right back in!

Keep reading

440 notes

·

View notes

Quote

You may be able to take a break from writing, but you can’t take a break from being a writer.

Stephen Leigh (via thewritersguardianangel)

270 notes

·

View notes