#Neuroscience and Mindfulness

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

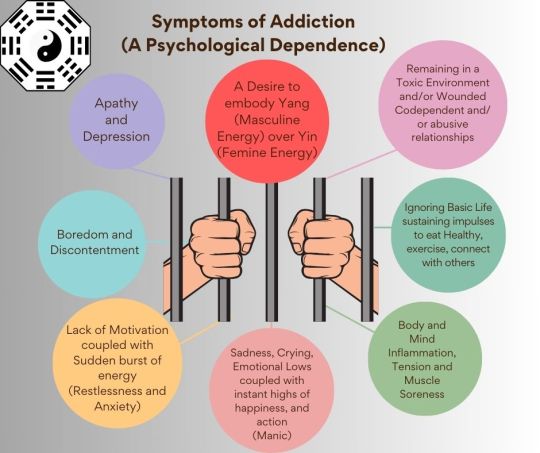

Choose you, Choose Love - The Fear of an Addict.

What is Addiction? - It is a State of Mind. It is a repetitive, compulsive use of a substance despite harmful consequences to the user. This Low and Hell-like state of mind is an addiction to drugs, money, alcohol or any pleasure, self-gratification ob...

After doing a Reiki healing session this morning with a Peer and exchanging beautiful Divine Energy, I welcomed alignment within, suddenly guided Towards my Divine Masculine, showing me what I needed to see and look at. “I love you. And by Loving Myself, I hope you see me so that you can Love yourself too” – The Divine Feminine. My intention for this post is to wake up and align with a…

View On WordPress

#Addiction#Addiction and the Brain#addiction counseling#Addiction Therapy#addiction treatment#Brain health#Can Food be the Mood Cure?#Cognitive Support#Divine#Energy Healing#Food for the Mind#Healing from Addiction#Healing the Body#Healing the mind#Healing the Spirit#How to heal your mind#Meditation#Mental health#Neuroscience and Mindfulness#Nutrition for the Mind#poetry#Psychological Awareness#reiki healing#Rozzebud#soul food fitness#Soul Searching#Spiritual Awareness#Spiritual Healing#spirituality#The Mood Cure

0 notes

Text

9 WAYS TO TRAIN YOUR SUBCONSCIOUS MIND

“Whatever we plant in our subconscious mind and nourish with repetition and emotion will one day become reality.”

1. PRACTICING AFFIRMATIONS- when you make a clear, definitive statement about yourself as if it is already true, your subconscious mind will take over and act under that belief. in order to reprogram the subconscious mind you must provide it consistent messaging that aligns with the new program you want to install.

2. VISUALIZATIONS- visualization is a powerful tool to retrain your subconscious mind because it allows you to feel and experience a situation that hasn't happened yet - as if it were real.

3. MEDITATION- meditation is a particularly powerful brain retraining method because it transcends any form of conscious thought.

4. DO SOMETHING YOU'VE NEVER DONE BEFORE- when you do this, your mind has no choice but to make new connections in the brain. in the unknown is where we can create great change and miracles.

5. WIRING IN A NEW THOUGHT/HABIT WITH REPETITION- brain neurons that fire together, wire together. the more consistently you wire in a new behavior, action, thought, etc the more it becomes apart of your new autopilot mind. when you forget that you were supposed to do that new thing, don't beat yourself up about it, your brain is designed to take shortcuts and revert to what it knows best; we call these shortcuts mental heuristics. what you could do then instead, is stack the new behaviour above the old one to remind you of the new habit/behaviour you're trying to ingrain.

6. SLEEP- it's the most essential step in consolidating new memories and facilitating neural plasticity. getting good quality and deep sleep means you release growth hormone, and getting enough sleep (7.5-9 hours) means you release testosterone, both are key molecules for learning and memory.

7. as you drift off to sleep, feel the emotion of what you want to experience. the subconscious mind speaks in the language of feeling and as as you drift off to sleep you are going into the theta state which is where the subconscious mind operates.

8. surround yourself with images of things you want to influence you.

9. mimick archetypes or role models.

++ practice positive thinking.

#subconscious#subconscious mind#psychology#neuroscience#how to train your subconscious mind#affirmations#meditation#spirituality#studyblr#studyspo#dark academia#loa#law of assumption#motivation#manifesation#manifesting#self concept#mental health#self esteem#university#philosophy#study blog#college#study#study motivation#studyinspo#student#high value mindset#high value woman#txt

254 notes

·

View notes

Text

Got super bored in a college lecture and suddenly treebark had possessed me

#og post#my art#treebark#trafficshipping#itlw#martyn inthelittlewood#rendog#fuckin. showing up to me psychology class and they’re like ‘let’s talk about neuroscience’#like YEAH it’s relevant but it’s also boring as hell and also NOT ON THE TEST. LET ME OUT#idk why treebark was on the mind. as of late its not typically#but hey i won’t look a gift horse in the mouth (aka i actually DREW something. i’d been struggling to draw lately)#also this was done entirely in a program i’d never used before. procreate. so that was a little agonizing#except the text that was done in my normal art program#bc i couldnt be bothered to figure out how to accomplish it in procreate

653 notes

·

View notes

Text

Self Concept: As Within So Without

I always advise to prioritize self concept to others, though this may be a more 'wishy washy' topic, as some believe you don't necessarily need to focus on self concept to get what you want (which if this is what you believe to be true in your reality, then sure).

However, I've seen the best results, for myself and others, come when they are grounded within themselves first. I want to explain why this is so important.

Self-concept, in short, is the idea of the self. The core beliefs, assumptions, and emotions we have when we think of who we are, personally and to the world.

When you learn to prioritize yourself, to love yourself, to believe in being the Creator (because you are, whether you like it or not, whether you think it or not), and do everything else for YOU FIRST, that is when the ability and proof to create and shape your 3D (reality) truly presents itself, and in a much more solid case.

I can attest to the power of self-concept, as it increases your ability to completely detach from outcomes for every and all desires you have and manifest more long-lasting, authentic experiences.

Think about it. If you aren't secure enough in yourself, if you don't trust yourself enough, if you don't feel worthy enough, etc., then how can feel worthiness in a relationship? How can you feel deserving for that promotion? How can you truly feel secure in the wealth? (etc.)

When you provide yourself the EMOTIONS FIRST (!!!!!) for the desire you wish to experience in your 3D, then by Law, it has to show up. That is why self love, self confidence, self assurance, self awareness, is so important. When you experience fulfillment without anything in the 3D giving it to you (aka, you don't need that relationship for happiness, you don't need that job to feel wealthy, etc.)---(put simply: nothing OUTSIDE OF YOU is the SOURCE, instead you realize YOU ARE THE SOURCE and the 3D CAN ONLY EXIST BECAUSE OF YOUR AWARENESS OF IT), that is not only detachment, but you now allow so much potential for your reality to give you EXPERIENCES that ALIGN WITH THOSE EMOTIONS, BECAUSE THAT IS WHAT YOU EMBODY.

It begins with you. It will always, always begin with you.

#abundance#confidence#law of attraction#manifesting#mindfulness#relationships#sp#wealth#money#lifestyle#health#mind conditioning#mental health#meditation#gratitude#wisdom#authenticity#authentic self#philosophy#science#neuroscience

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

I once read a wish that stuck with me:

“I hope that someday, somebody wants to hold you for twenty minutes straight, and that’s all they do. They don’t pull away. They don’t look at your face. They don’t try to kiss you. All they do is wrap you up in their arms, without an ounce of selfishness in it.”

―Adrienne Shelly

Sometimes, a person’s words can feel like a hug.

Some people are particularly good at this.

#quotes#writing#mental health#poetry#musings#literature#emotional health#words#thoughts#love#love language#physical health#physical touch#mind body connection#neuroscience#human

27 notes

·

View notes

Quote

All our sentiments - religious, romantic or any other - are born in the neurons.

Abhijit Naskar, Neurons of Jesus: Mind of A Teacher, Spouse & Thinker

#quotes#Abhijit Naskar#Neurons of Jesus: Mind of A Teacher#Spouse & Thinker#thepersonalwords#literature#life quotes#prose#lit#spilled ink#biology#brainy-quotes#consciousness#consciousness-mind-brain#consciousness-quotes#human-mind#human-nature#inspirational#love#mind#motivational#neurology#neurons#neuropsychology#neuroscience#neurotheology#romantic#science-of-mind#truth#words-of-wisdom

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

hm have i ever considered that people thinking my fic is abandoned is actually part of the metanarrative about the theme of the fic that includes "not forgetting about or valuing less something that is unpolished or 'half-finished' because it still can communicate full moments of genuine human existence and understanding between reader and writer" so actually I should stop being irked by 'is it unfinished' comments and just appreciate the way they nicely add onto this fully constructed and definitely deliberate quality of of metanarrative? no i have not but i am thinking that now and it is funny.

#I'm reliving some feelings I had when I first wrote wall fic rn and it's making it easier to reread the first parts and remember all the#vibes going on. because one of the big things about wall fic is i want to feel like we're sucked in when we write/read it#and that requires a certain state of mind from me hat sometimes im hesitant to slip into#ok but i just remembered the part where kdj is like talking about how important hsy's first unfinished novel was so important to him is at#the top of chapter four which literally is a chapter that has remained unfinished for 2+ years? hilarious actually#like this mf (me) managed to invent 'unfinished chapters' in addition to his unfinished fic and the top of said chapter has a big important#thing about how the finishedness of something doesn't have to limit the way you connect to it that is sooo fucking funny of me#sorry okay i am only now pushing past the burnout/embarrassment of i cant believe my fic is unfinished when literally i was getting my#degree in neuroscience? like ok king stay in school fr. it was all okay and orv is like literally still here and im just fucking#funny for doing all this tbh hahaha am feeling some euphoria about it#personal

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Had baby dream, will be haunted for 12-200 business hours

#lilac rambles#the human mind FASCINATES ME#it's why i nearly went into neuroscience#because what do you MEAN my brain can come up with something in a dream that i recognize as the feeling of an unborn baby moving when ive#never been pregnant before???? how off is it from the actual thing??? because like. it cant be accurate. it just cant.#but STILL it's so weird and wonderful

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

z. X "The Brain, Pt. 1" Quick steps through key concepts in neuroscience of great utility when reading our works on neurodivergence, consciousness, the critical brain, differential processing, etc

#neuro#neuroscience#brain#4e cognition#enacted cognition#embedded cognition#embodied cognition#extended mind thesis#connectionism#materialism#descartes#critical brain theory#self-organized criticality#critical brain#education#autism#zine#ladyfingerpress#creative commons#primer

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tips & Tools for Releasing Stored Trauma in Your Body

🌻Somatic Experiencing: Developed by Dr. Peter Levine, Somatic Experiencing can release trauma locked in the body. This method is the result of a combination of stress physiology, psychology, neuroscience, medical biophysics and indigenous healing practices. (Videos on youtube)

🌻Mindfulness and Movements: going for a walk, bike ride, Boxing, Martial arts, yoga (or trauma-informed yoga), or dancing. People who get into martial arts or boxing are often those who were traumatized in the past. They’re carrying a lot of anger and fighting is a great release for them. Exercise helps your body burn off adrenaline, release endorphins, calm your nervous system, and relieve stress.

Release Trapped Emotions: 🍀How to release anger from the body - somatic healing tool 🍀Somatic Exercises for ANGER: Release Anger in Under 5 Minutes 🍀Youtube Playlist: Trauma Healing, Somatic Therapy, Self Havening, Nervous system regulation

🌻 Havening Technique is a somatosensory self-comforting therapy to change the brain to de-traumatize the memory and remove its negative effects from our psyche and body. It has a calming effect on the Amygdala and the Limbic system. 🌼Exercise: Havening Technique for Rapid Stress & Anxiety Relief 🌼Exercise: Self-Havening with nature ambience to let go of painful feelings 🌼Video: Using Havening Techniques to rapidly erase a traumatic memory (Certified Practitioner guides them through a healing session)

🌻Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is a psychotherapy technique often used to treat anxiety and PTSD. It incorporates rhythmic eye movements while recalling traumatic experiences. This combo changes how the memory is stored in the brain and allow you to process the trauma fully.

🌻Sound & Vibrational Healing: Sound healing has become all the rage in the health and wellness world. It involves using the power of vibration – from tuning forks, singing bowls, or gongs – to relax the mind and body.

🌻Breathwork is an intentional method of breathing that helps your body relax by bypassing your conscious mind. Trauma can overstimulate the body’s sympathetic nervous system (aka your body’s ‘fight-or-flight’ response). Breathwork settles it down.

Informative videos & Experts on Attachment style healing: 🌼Dr Kim Sage, licensed psychologist 🌼Dr. Nicole LePera (theholisticpsychologist) 🌼Briana MacWilliam 🌼Candace van Dell 🌼Heidi Priebe

Other informative Videos on Trauma: 🌻Small traumas in a "normal" family and attachment: Gabor Maté - The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture 🌻Uncovering Triggers and Pattern for Healing: Dr Gabor Maté 🌻Understanding trapped emotions in the body and footage of how wild animals release trauma

Article: How Trauma Is Stored in the Body (+ How to Release It)

Article: 20 self-care practices for complex trauma survivors

#trauma#healing#attachment styles#trauma informed#somatic#yoga#psychology#neuroscience#mindfulness#Exercise#emdr#eft tapping#sound healing#Breathwork#soothing#nervous system#self care#my post#my information collection#research#trauma healing#attachment trauma#insecure attachment#anxious attachment#inner healing#therapy#psychologytoday#polyvagal#nervous system regulation#relationships

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is always wise to look ahead, but difficult to look further than you can see.— From Sense and Nonsense in Psychology by H. J. Eysenck

#Psychology#Science#Logic#Reason#Mind#Brain#Research#Evidence#Facts#Rationality#Skepticism#Thinking#Bias#Truth#Behavior#Analysis#Knowledge#Objectivity#Perception#Intelligence#Learning#Cognition#Empirical#Experiments#Neuroscience#Personality#Theories#Critique#Investigation#Understanding

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

HEY

WHY IS NO ONE TALKING ABOUT BEAUTIFUL MINDS WITH ZACHARY QUINTO IT HAS:

Gay enemies to lovers (hinted)

Psychology taken seriously

Zachary Quinto

Really cool visuals to demonstrate neurological conditions

Multiple disabled characters

Research based on the works of neurologist Oliver Sacks

Zachary Quinto

Sassy, patient focused stories

Zachary Quinto

It’s on Peacock! Watch it!

#beautiful minds#beautiful minds tv show#beautiful minds tv#zachary quinto#neuroscience#neurology#Oliver sacks

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

thinking about how the only things in the universe that don't consistently operate by human logic are human minds (and like, electrons i guess)

#each human mind is its own universe#science#mindfulness#neuroscience#psychology#deep thoughts#physics#logic

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just self published my first Academic paper NOT related to my Tertiary education or research.

https://www.academia.edu/resource/work/107548963

Check it out, covers some pretty interesting topics!

:Update: Feeling ambitious, I published an additional eight papers yesterday and I can't take back the consequences now.

#science#qualia automata#cybernetics#Unsignificant Sentience#psychology#writing#neuroscience#philiosophy#mind palace#mind map#unsignificant sentience

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1926, Virginia Woolf wrote about how, when one is ill:

All day, all night the body intervenes; blunts or sharpens, colours or discolours, turns to wax in the warmth of June, hardens to tallow in the murk of February. The creature within can only gaze through the pane – smudged or rosy; it cannot separate off from the body like the sheath of a knife or the pod of a pea for a single instant; it must go through the whole unending procession of changes, heat and cold, comfort and discomfort, hunger and satisfaction, health and illness, until there comes the inevitable catastrophe.

Woolf knew well about bodily interventions, suffering as she did from a range of symptoms pertaining to what today we call bipolar disorder. Yet the body intervenes constantly, whether one is ill or not. It is the mode of intervention that conditions how well, or unwell, we feel. A state of wellbeing is one in which we do not need to think about our embodied organism in any way other than the sensorial pleasures it affords, where we are immersed within our environment, engaged in an activity, involved with others. But one of physical or emotional pain affects the very foundation on which the sense of self we otherwise take for granted rests: what we feel ourselves to be can be upended. When this happens, we may realise that what we feel ourselves to be is in fact constructed. How we exist as embodied selves is a highly complex business involving the brain and body engaged in constant interaction.

Over the past few years, scientists working in neuroscience and psychology have been listening in on these brain-body interactions – in health and illness – and analysing how they constitute the always embodied self. They have been studying the sense of the body from within, which is called interoception. It is a term you will be hearing increasingly. This research is dismantling the pillars of a belief system that has long endured within those fields – as well as in the popular imagination – that the brain is an information-processing machine that can be understood apart from the rest of the body, as if our conscious, reasoning self were the output of a disembodied brain, and as if we were not fully biological creatures. This shift within the mind sciences is game-changing, and merits attention. Yet perhaps because we are in its midst, even its actors might not be fully aware of its historical and philosophical significance – and of its potential cultural and clinical implications. The time has come to take stock of the revolution under way.

Since the publication in 1994 of his first widely read book, Descartes’ Error (followed by four others), which showed how embodied emotional processes are integrated into rational ones, Antonio Damasio has been the most visible and influential neuroscientist to develop this reconception. Since then, research into the embodied sense of self has accelerated. And now a new generation of scientists is building on the insights first elaborated by Damasio. Over the past decade, there has been a six-fold increase in publications on interoception. Questions about the self – self-consciousness and bodily consciousness, our sense of body ownership, and agency – once the exclusive domain of philosophy, can now be investigated empirically. The emerging results have the power to transform our vision of what we are, as well as ground in scientific detail what we may intuitively feel about ourselves. They can provide insights into what it is that may be breaking down when the always embodied sense of self is disrupted, when that window pane is smudged. This is particularly important in understanding neurological and psychiatric disorders – psychotic events and schizophrenia, as well as autism, attention disorders, dyspraxias, somatoform disorders, body image and emotional-processing disorders such as anorexia, alexithymia (a difficulty in identifying or acting upon felt emotions) and more.

Interoception consists in the perception and integration of all signals from within our body, whether we attend to them or not. These include autonomic, hormonal, visceral and immunological functions: breathing, blood pressure, cardiac signals, temperature, digestion and elimination, thirst and hunger, sexual arousal, affective touch, itches, pleasure and pain. Interoception therefore lies at the core of our very sense of self: physiology and mental life are dynamically coupled. The central and autonomic nervous systems act on each other, higher cognition and emotional states interacting constantly. We sense, monitor and adapt ourselves to the situations we find ourselves in, often without our realising it – homeostatic processes thanks to which we physiologically adjust to the changing environment, and to which interoception corresponds.

The neurophysiologist Charles Sherrington was the first to use the term ‘interoceptive’, as long ago as 1906. He used it to refer to the sense of our own viscera (today’s visceroception). The term homeostasis was coined in 1926 – the year in which Woolf published her essay – on the back of the concept of ‘milieu intérieur’ (‘interior milieu’) that the biologist Claude Bernard had first described in the mid-19th century. As the historian Stefanos Geroulanos and the anthropologist Todd Meyers have recounted on Aeon in light of their book on the topic, it emerged following the carnage of the First World War, which had led physiologists and clinicians to reconfigure their understanding of the body as ‘an organism that organises itself’, as ‘an integral whole’. Damasio wrote in his book Self Comes to Mind (2010) that though the principles of homeostasis ‘are applied daily in general biology and medicine, their deeper significance in terms of neurobiology and psychology has not been appreciated’. But now, just a few years later, they are both appreciated and far better understood.

It is in relation to others that we acquire a sense of self, which develops in this embodied interoceptive way from infancy

The meaning of interoception expanded after the neuroscientist A D Craig, nearly a century after Sherrington, revised it to encapsulate what he termed ‘a sense of the physiological condition of the entire body’: these translate as ‘“feelings” from the body that provide a sense of [our] physical condition and underlie mood and emotional state’. Emotional feelings are distinct from emotions, and they are ‘mental experiences of body states’, as Damasio had advanced with his somatic marker hypothesis – summarised by Craig as ‘the subjective process of feeling emotions’, which recruits brain regions involved in homeostastic regulation. These feelings, ‘grounded in the body itself’, are crucial to our ability to make decisions. We don’t merely think through our decisions, including those that seem most rational, such as those concerning finances: we experience feelings about their possible outcomes that determine how we act – and if the brain areas involved in the processing of emotional feelings are damaged, our ability to make decisions is impaired. Craig identified the interoceptive pathways that provide a cortical image of homeostatic processes from all the organs, and which translate as feelings when brought to consciousness. As detailed in How Do You Feel? An Interoceptive Moment with Your Neurobiological Self (2014), he and his team individuated projections to the brainstem of neurons in the spinal cord called lamina I: these provide to the autonomic nervous system, or ANS, input about the ‘mechanical, thermal, chemical, metabolic and hormonal status of skin, muscle, joints, teeth and viscera’ from small-diameter nerves throughout the organism’s tissues. It is from these lamina I projections to brainstem that ‘sensory channels’ ascend to areas of the thalamus, and from there to a brain area called insula, the ‘interoceptive cortex’.

In contrast to interoception, the notion of proprioception is more familiar to most of us – the sense of our dynamic, musculoskeletal body in space. It is how, for example, I know where my arm is when I wake up in the dark. It is distinct from interoception, but functionally and anatomically connected to it, as is also the case for exteroception, the sensory perception of the outside world. These senses can be manipulated, as has been done to great effect in the much replicated Rubber Hand Illusion (RHI) first conducted 21 years ago, where one sees a rubber hand being stroked synchronously with one’s own hand – itself unseen – with the resulting sense that the rubber hand is one’s own, an effect dramatically demonstrated when the experimenter hits the rubber hand with a hammer and the subject almost invariably recoils as if the hand belonged to him or her. The RHI has served research into the fundamental sense of body ownership and the related sense of agency – the sense we normally take for granted that my leg, say, is mine, or that I am moving my own arm. Complex processes enable this sense to develop and be maintained, or, as can be the case in somatosensory and sensorimotor pathologies, disturbed. The RHI, and related experiments triggering a full-body illusion show that ‘multisensory integration can update the mental representation of one’s body’ and that exteroception can influence self-awareness, as reports the psychologist Manos Tsakiris, whose research within these areas has been yielding important insights.

But, as he and his team have found, this induced change in conscious body ownership results also in nonconscious changes in the physiological regulation of the self – that is, in interoception. The anterior insula is involved in both these exteroceptive and interoceptive processes, resulting in how we feel that our body is oneself and that the self remains unified and stable amid exteroceptive inputs. Moreover, it has been shown to be activated during both interoceptive and emotional experience, and also to be involved in the distinction of self and other. This in turn bears on the related capacity for empathy – with consequences for racial bias that Tsakiris has recounted here on Aeon, in a finding by his team that throws light on the neurobiology underpinning our social and political emotions. Other brain areas involved in the bodily self-consciousness arising out of the processing of multisensory signals are the fronto-parietal and temporo-parietal regions, as reported by the cognitive neuroscientists Olaf Blanke and Andrea Serino, who perform key research on how multisensory perception gives rise to the embodied, spatially located, self-conscious subject of experience that we each are (with eventual applications to prosthetic limbs).

However crucial a finding is the involvement of these areas, and of the insula in particular, in the formation and maintenance of a core selfhood, it is the interactions between brain and body that are the centre of our story. The body sends signals to the brain, and vice versa, in a constant feedback loop that involves the ANS acting in response to external inputs and interoceptive states, enabling and disabling our various states of arousal and fight or flight reactions. In this way, ANS serves homeostatic adjustments. Recently, the notion of allostasis has been gaining ground in accounting for these adjustments: where homeostasis refers to a stable condition, allostasis refers to the process that the organism engages in to achieve stability, ‘the regulation of bodily states through change’, as Tsakiris and the neuroscientist Anil Seth define it. So for instance, one homeostatic imperative is to remain within a specific temperature range: we would die if we were unable to anticipate how environmental temperature influences body temperature, and so to adjust our actions accordingly, dive into the cool sea when the sun is baking, say. Allostasis is this anticipatory adjustment – what ‘enables the organism to proactively prepare for such disturbances before they occur’, writes the philosopher Jakob Hohwy with Andrew Corcoran. The same process applies to all basic bodily functions. We need to get hungry before we faint, thirsty before we get dehydrated, and so on.

These complex interoceptive processes are happening all the time, whether we are aware of them or not. They are modulated by the ANS, ensuring constant adjustments as well as basic survival. In cases of stress, these evolved responses of the ANS can go into overdrive, affecting gut function and vascular health, triggering the various immune and inflammatory responses that result in illness. Investigations regarding this all-important brain-gut interoceptive pathway are ongoing. But the equally all-important brain-heart connection has been particularly crucial to our understanding of interoception, because of the ease in performing heartbeat detection tasks to test individual interoceptive ability otherwise challenging to measure precisely because it is the stuff of our subjective experience. The neuroscientist Catherine Tallon-Baudry has hypothesised a ‘neural subjective frame’, connected to homeostatic regulation, necessary to subjective, perceptual consciousness, which depends on ‘how the brain registers information on the heart’. Important experiments have been conducted, most notably by the neuroscientists Sarah Garfinkel and Hugo Critchley, that show how emotions are modulated in synchrony with cardiac rhythms. Emotional self-knowledge is a multilayered affair: Garfinkel and Critchley have also identified how interoceptive accuracy, sensitivity and awareness are distinct from each other, reflecting respectively the ability to detect one’s heartbeats, the evaluation of one’s own ability to do so, and one’s ‘meta’-ability to gauge one’s own awareness. We all differ in these abilities, and in our corresponding sensitivity to the ongoings of our body. These exquisite distinctions between levels of self-awareness translate into pain threshold, anxiety level and so on – into our ability to experience feelings, to have a sense of what they correspond to, to track and modulate them, or not.

These abilities even translate as character traits. So for instance, people with a higher interoceptive accuracy – that is, a greater ability to monitor their own internal states, identified by heartbeat detection tasks – are less prone to be taken in by the RHI than those on the lower end of the scale, Tsakiris and colleagues have found. This means that their self is more stable, and their capacity for empathy higher: as Tsakiris and the psychologist Clare Palmer report, ‘interoceptive processing acts to stabilise the model of our self’, so we can ‘attribute emotional and mental states to the self or to others without blurring the distinction between “self” and “other”’. This matters hugely in our day-to-day lives. In a major review article in Neuropsychoanalysis, the psychologist Aikaterini Fotopoulou – who studies in particular the centrality of affective touch in interoceptive processing and emotional development – and Tsakiris argue that the self is shaped from early infancy – when one is entirely dependent on the carer for homeostatic regulation and hence survival – by embodied interactions with carers that centrally include affective touch. This confirms insights from psychoanalysis: affect is ‘the background of all subjective, conscious experience’, they write. Our capacity to modulate affect begins with the carer attending to the infant’s embodied needs. Out of the processing of sensorimotor signals initially integrated into a basic, minimal or core self arise what they call ‘embodied mentalisations’ that progressively lead to our ability to form a boundary between self and other – a process that cannot happen in isolation. It is necessarily in relation to others that we acquire a sense of self, which develops in this embodied interoceptive way from infancy on. We sustain a constant sense of selfhood in dynamic relation to and distinction from others, and, in turn, our ability to form a boundary between self and other is a function of our ability to feel our embodied selves from within – this is the important novelty of their claim. An unformed or badly formed boundary can translate into psychiatric pathologies.

Our brains serve our bodies, rather than the obverse – a liberating idea

This picture integrates a useful model from artificial intelligence, principally developed by the influential neuroscientist Karl Friston, called Predictive Coding, which is increasingly widespread in accounting persuasively for interoceptive and homeostatic/allostatic processes, and for psychopathologies, including depression. It reconceives the brain as a ‘statistical organ’ that makes predictions about sensory information on the basis of previous instances. It ‘generates explanations for the stimuli it encounters’, Friston writes with Anil Seth, ‘in terms of hypotheses that are tested against sensory evidence’ from our visceral sensations. The actions we undertake in response to interoceptive signals – that is, the allostatic regulation that our homeostatic needs impel us to engage in – serve to reduce prediction errors with regard to our expectation of environmental inputs. In this way, our present is made of a constant projection into the future out of the past. So, as Fotopoulou and Tsakiris write, an infant will ‘progressively build generative models regarding the possible causes of their sensory states in the external world’. The brain predicts the probability of an embodied feeling state occurring as a result of an input – ‘embodied mentalisation’, in their coinage. This physiological, homeostatic reaction turns into the ‘psychological feelings’ they call ‘mentalisation’ and that form the core of the infant’s minimal self. The stability of the self in an always changing environment, Tsakiris and Seth have argued, is ensured by our engaging in allostatic prediction. This stability is never given: our constantly revised engagement with the world is a dynamic process.

In Self Comes to Mind, Damasio argues that ‘the body is a foundation of the conscious mind’: our brains serve our bodies, rather than the obverse – a seemingly provocative, but profoundly liberating idea that arises out of the oft-forgotten fact that life began without nervous systems. Our inherently homeostatic selves are on a continuum with homeostatically governed single cells and bacteria. As he writes, ‘the special kind of mental images of the body produced in body-mapping structures, constitute the protoself, which foreshadows the self to be’ – and eventually culture, art and meaning, as he has also continued exploring in his most recent book, The Strange Order of Things: Life, Feeling, and the Making of Cultures. The structures responsible for this, as Craig showed too, are in the evolutionarily ancient upper brain stem, below more recent cortical structures, ‘attached to the parts of the body that bombard the brain with their signals’, forming a ‘resonant loop’ as somatic markers. That these processes begin with homeostasis shows how deeply continuous our very consciousness is with the most primitive fabric of life. It is a potent rebuttal to René Descartes. And as Tsakiris has put it: ‘By grounding the self in the body, psychology could, at last, overcome Cartesianism and make the bodily self the starting point for a science of the self.’ We are indeed beyond the starting point now.

This shift away from Cartesianism – let us call it the interoceptive turn – has a long history within Western thought, at the crossroads of philosophy, medicine and psychology. We may begin when there developed over the 17th century mechanistic and corpuscularian models of nature – attempts at forging a new scientific method to re-describe matter, motion and living bodies. These freed natural philosophy from the Aristotelian strictures that had prevailed for close to 2,000 years and had ensured the mind-body, human-animal continuum. Descartes is infamous for loosening the connection of matter and mind. His ambition to replace the Aristotelian system with his own mechanistic model was broadly successful within philosophy – and later within medicine. Echoing St Augustine’s idea that the very existence of thought presupposed a disembodied, thinking self, Descartes performed the introspective turn that we are outgrowing – theologically locking himself into a system that required the conscious mind to pertain to an immaterial, immortal soul, a ‘thinking thing’ separate from the realm of ‘extended’ physical things. And he thereby sundered the continuum of higher, self-conscious thought with the other functions of all living beings, denying beasts any sort of mindedness. There were alternatives to this substance dualism – and he himself accepted that mind and body do interact, in emotional experience. Many physicians, attuned to the realities of ailing patients, adopted Gassendism, an adaptation of ancient atomism and Epicureanism to Christianity, which maintained the continuum of nature. Over the 18th century, vitalists battled against mechanism in philosophy and medicine, arguing for the inherence of soul in body. There were attempts from then on at a psychosomatic medicine. As materialism rose along with secularism, the notion of a separate, immaterial soul lost its function.

But it took a while for the empirical study of the embodied mind to become enmeshed with the philosophical study of knowledge and self. Realms of enquiry remained divided until the birth of scientific psychology, in the second half of the 1800s, when modern neurology and psychiatry took shape along with growing knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the brain and nervous system. Freud himself specialised in neurology when the discipline was new, before realising that the neurobiology of his day would be unable to yield the secrets of mind. He eventually posited an unconscious field of mental action, often somatised – as in the case of hysteria, today’s somatoform disorder – but accessible through talk, creating psychoanalysis. The notion of a scientific psychology was coined by his older contemporary Wilhelm Wundt, who elaborated an introspective ‘experimental psychology’ to build a theory that would account for subjectivity. However, what first kickstarted a quarter-century ago the perspectival shift that has led to where we are today is the resurgence of William James’s scientific psychology, as given in his Principles of Psychology of 1890 and in his 1884 article on emotions – mainly his notion that emotions are the product of the body’s autonomic response, only thereafter translated as behaviour and experienced as feelings, and that consciousness is a continuous ‘stream’ of embodied experiences. (It is the very stream that formed the core of Woolf’s writing technique.)

Western medicine mechanistically chops up the body and leaves patients confused about the nature of their ailments

Until then, philosophy had remained largely disengaged from empirical investigation (in contrast to early modern practices), while the belief prevailed within cognitive science that our brain might ‘just’ be a machine that computes information, performing functions that could be studied irrespective of the biological structures upon which they operate. It was a transposition of mind-body to brain-body dualism – as if biology were incidental to the higher activities of an ultimately disembodied mind. This functionalist focus on the algorithmic operations of cognition had followed upon behavioural psychology, which, partly in reaction to Wundt’s introspective psychology and in an extension of Cartesianism, posited that behaviour was the outcome of reflex-like responses to environmental stimuli rather than manifestations of emotionally rich intentions. Cognitive science outgrew the behaviourist model from the 1950s on, absorbing neuroscience and evolutionary theory into its accounts of individual and social psychology, and elaborating scientific protocols that put the mind back behind the behaviour. The analogy of the brain with a computer, however, remained powerful.

Computational neuroscience continues to grow. Friston’s Predictive Coding theory is one of its fruits. But the hold of ‘strong AI’ has loosened since the 1990s – just as Damasio’s insights into embodied emotions and the emotive self started putting the whole organism together again. By then, the body had also become a popular theme in the humanities and social sciences. And the centrality of the body to the mind began around that time to be analysed within an anti-cognitivist neurophilosophy first made popular by Francisco Varela, which combined an outgrowth of the phenomenology of Maurice Merleau-Ponty with Buddhism: for ‘enactivism’ and related approaches, cognition and the sense of self depend upon a body endowed with sensorimotor capacities embedded within the world. The philosophers Shaun Gallagher or Dan Zahavi work within this lineage, and the hybridisation of disciplines has enabled philosophers such as Frédérique de Vignemont to analyse neuroscientific data, and, conversely, for neuroscientists to work with philosophers. The minds of animals are studied on a continuum with ours. The remnants of substance dualism endure in AI and some everyday thought habits. But we can no longer escape the reality of our biology, as scientists are showing us, a fraction of whose work I have presented here. And there is much more ahead.

Yet insights from theory have always been hard to apply straightaway, if at all, to the clinical realm. There is today an increasing dissatisfaction with mainstream Western medicine, which mechanistically chops up the body and leaves patients confused about the nature of their ailments, and concurrently a growing market for alternatives that take holism seriously. (In Germany alone, psychosomatic medicine is an institutionally established clinical field.) In parallel, practices such as yoga continue to grow worldwide. The science of embodiment might provide eventual protocols for the testing of such holistic treatments and practices, to help target them to particular conditions, especially psychiatric and neurological. Biofeedback, the use of sensory stimuli, physical therapy, etc, have been shown to help reduce the anxiety caused by the combination of high interoceptive awareness and alexithymia (as Fotopoulou and colleagues have shown), and often found in autism, heighten interoceptive awareness in anorexia and attention disorders – or lower it in depression and somatoform disorders, where, as the neuroscientist Georg Northoff has argued in his book Neuro-Philosophy and the Healthy Mind (2016), one’s body becomes the predominating content in awareness, at the expense of the environment. And just as mindfulness has become a widespread tool, which the psychologist Norman Farb has studied in relation to interoception, so the practice of yoga, which powerfully modulates interoceptive awareness, could benefit from inputs from the scientists investigating embodiment – and vice versa.

The interoceptive turn is a historical step to the other side of our mind’s looking glass, into the heart of our complex organism, reconciling us to our mortal embodiment, forcing us to consider our mental makeup with humility as just one aspect of biology – a far cry from the posthumanist future that Yuval Noah Harari and others warn us about. It does not dissolve the mystery of how we are able to think and speak sophisticated thoughts, create art and meaning, or indeed investigate self and world: science does not replace experience, and though it is indispensable to serious thought about human nature, and to the advancement of clinical care, so is a humanist eye on what the best of science can tell us about ourselves. Yet this new picture has a transformative power. It can help understand, to an extent, how we relate to each other as embodied beings, how we feel at each moment of our lives, why Woolf’s ‘creature within’ feels what she does when unwell. It can help us understand each other in our animal nature so as to regain harmony with nature, and in our inherently social nature so as to regain harmony with each other – and to maintain our psychophysical integrity in the face of the ‘procession of changes’ that Woolf writes of. No window pane into the self is perfectly transparent. But we are clearing up some smudges.

#Interoception#the inner#articles#Aeon#philosophy#physiology#neuroscience#cognition and intelligence#science of mind#Body Alive#Structural Integration Atlanta

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Illusion of Objectivity: Challenging Traditional Views of Reality

Donald Hoffman's groundbreaking research and theories fundamentally challenge our understanding of reality, consciousness, and perception. By positing that consciousness is the foundational aspect of the universe, rather than a byproduct of physical processes, Hoffman's work has far-reaching implications that transcend disciplinary boundaries. This paradigm shift undermines the long-held assumption that our senses, albeit imperfectly, reflect an objective world, instead suggesting that our experience of reality is akin to a sophisticated virtual reality headset, constructed by evolution to enhance survival, not to reveal truth.

The application of evolutionary game theory to the study of perception yields a startling conclusion: the probability of sensory systems evolving to perceive objective reality is zero. This assertion necessitates a reevaluation of the relationship between perception, consciousness, and the physical world, prompting a deeper exploration of the constructed nature of reality. Hoffman's theory aligns with certain interpretations of quantum mechanics and philosophical idealism, proposing that space, time, and physical objects are not fundamental but rather "icons" or "data structures" within consciousness.

The ramifications of this theory are profound, with significant implications for neuroscience, cognitive science, physics, cosmology, and philosophy. A deeper understanding of the brain as part of a constructed reality could lead to innovative approaches in treating neurological disorders and enhancing cognitive functions. Similarly, questioning the fundamental nature of space-time could influence theories on the origins and structure of the universe, potentially leading to new insights into the cosmos. Philosophical debates around realism vs. anti-realism, the mind-body problem, and the hard problem of consciousness may also find new frameworks for resolution within Hoffman's ideas.

Moreover, acknowledging the constructed nature of reality may lead to profound existential reflections on the nature of truth, purpose, and the human condition. Societal implications are also far-reaching, with potential influences on education, emphasizing critical thinking and the understanding of constructed realities in various contexts. However, these implications also raise complex questions about free will, agency, and the role of emotions and subjective experience, highlighting the need for nuanced consideration and further exploration.

Delving into Hoffman’s theories sparks a fascinating convergence of science and spirituality, leading to a richer understanding of consciousness and reality’s intricate, enigmatic landscape. As we venture into this complex, uncertain terrain, we open ourselves up to discovering fresh insights into the very essence of our existence. By exploring the uncharted aspects of his research, we may stumble upon innovative pathways for personal growth, deeper self-awareness, and a more nuanced grasp of what it means to be human.

Prof. Donald Hoffman: Consciousness, Mysteries Beyond Spacetime, and Waking up from the Dream of Life (The Weekend University, May 2024)

youtube

Wednesday, December 11, 2024

#philosophy of consciousness#nature of reality#perception vs reality#cognitive science#neuroscience#existentialism#philosophy of mind#scientific inquiry#spirituality and science#consciousness studies#reality theory#interview#ai assisted writing#machine art#Youtube

7 notes

·

View notes