Text

As a visually disabled person myself, one thing I wish TNG had done with Geordi is show his disability actually affecting how he functions in his daily life. For example, I can’t remember a single time in TNG where Geordi is shown as needing accommodations in his work environment. You might say that’s because his visor means that he can basically “see” normally and so he wouldn’t need accommodations, but I find this explanation frustrating.

For one thing, real life visually disabled people absolutely require accommodations to do most jobs, so if Geordi’s meant to be any kind of accurate reflection of the experiences of blind people, he should require some accommodations. For me at least, it isn’t some kind of wish fulfillment fantasy to see a visually disabled character who can do anything a sighted person can with no accommodations whatsoever. Instead, it feels like a denial of everything that being disabled has meant to me over my life. Disabled people are disabled. We have more difficulty doing certain tasks than an able-bodied person would – that’s what makes us disabled. We require changes to our environment in order to function well.

Also, literally just based on the in-universe information given about Geordi’s visor, it doesn’t make any sense to me that he wouldn’t require accommodations. Geordi’s visor is not really described as simulating vision, it is described as providing completely different sensory information about the physical properties of the world around him. I like to imagine the visor’s input as a kind of enhanced spatial awareness with a precise knowledge of where certain objects are, what their shape is, and what they’re made of. As TNG mentions several times, Geordi’s visor provides much more information than human eyes do, but, importantly, in the few episodes where the details of how Geordi’s visor works are discussed at all, it’s never described as providing purely visual information such as the color or reflectiveness of an object. I think that if Geordi faces a mirror, his visor will tell him there’s a piece of glass in front of him and he’ll know about how large it is and what material it’s made of, but he won’t be able to see his reflection in it, because the visor doesn’t provide that kind of visual information. This distinction is important to me, because it means that Geordi is still functionally blind with the visor, and it should mean that he interacts with the world differently from a sighted person.

For example, I would have loved if Geordi had been shown to be unable to recognize particular people until they spoke. All his visor tells him is that there’s a person in front of him and about what size and shape they are, but this isn’t generally enough information to determine a person’s identity. He canonically perceives Data as looking very different from an organic person which makes sense because Data is made of fully different material. And maybe Geordi can generally tell different species apart based on different body temperatures or something like that. But I really wish that Geordi had been shown at least a few times to need the sound of a person’s voice or some other cue to tell him who they were.

I also think it doesn’t make sense that Geordi can apparently read text on computer screens. How can he read if the visor doesn’t really provide visual information? A computer screen should just register as a flat piece of material. Geordi should have required some kind of accommodation to be able to use the computer screens. For example, maybe Geordi could use the computer entirely through voice commands, something that obviously already exists in the star trek world. Or he could use some kind of tactile display. The Voyager episode The Year of Hell shows that computer terminals on starships are able to utilize a tactile display that I’m guessing is somewhat similar to braille. I loved this mention in Voyager of tactile displays, because it indicates that Starfleet ships are probably automatically equipped with such accessibility devices. Geordi needing an accommodation as small as this would have gone really far in terms of making him feel like a genuine representation of a disabled character, at least to me.

402 notes

·

View notes

Text

Related to the space cats fic

✨ Another bit from my Patreon comic 'On Gardening & Fixing The Cat', which is all about weird interactions with nature and the environment 🌿 no apologies for using the word lover, I'm very European these days

⭐ If you'd like to read the whole thing, sign up to my Patreon on the $2 tier! Patreon is my paid subscriber platform. It has hundreds of comics going back to 2017 (most of them Background Slytherin🐍) and I currently publish one long (funny) comic per month on my $2 tier. Patreon is also where all my best work goes currently, so if you want to see more of my comics, please do sign up! http://patreon.com/emilyscartoons

🌟And last thing - the final slide of this post is available as a print in my shop if you'd like it! https://emilyscartoons.myshopify.com/

💖 Luv ya

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

More SuitU dressup game ficlets.

Fae is the young goth character’s pronoun there, not faer name. Faer name is Jaz.

#suitu snippet stories#very short fiction#short ficlet#enby story#dressup game stories#dressup game#queer best friend story

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

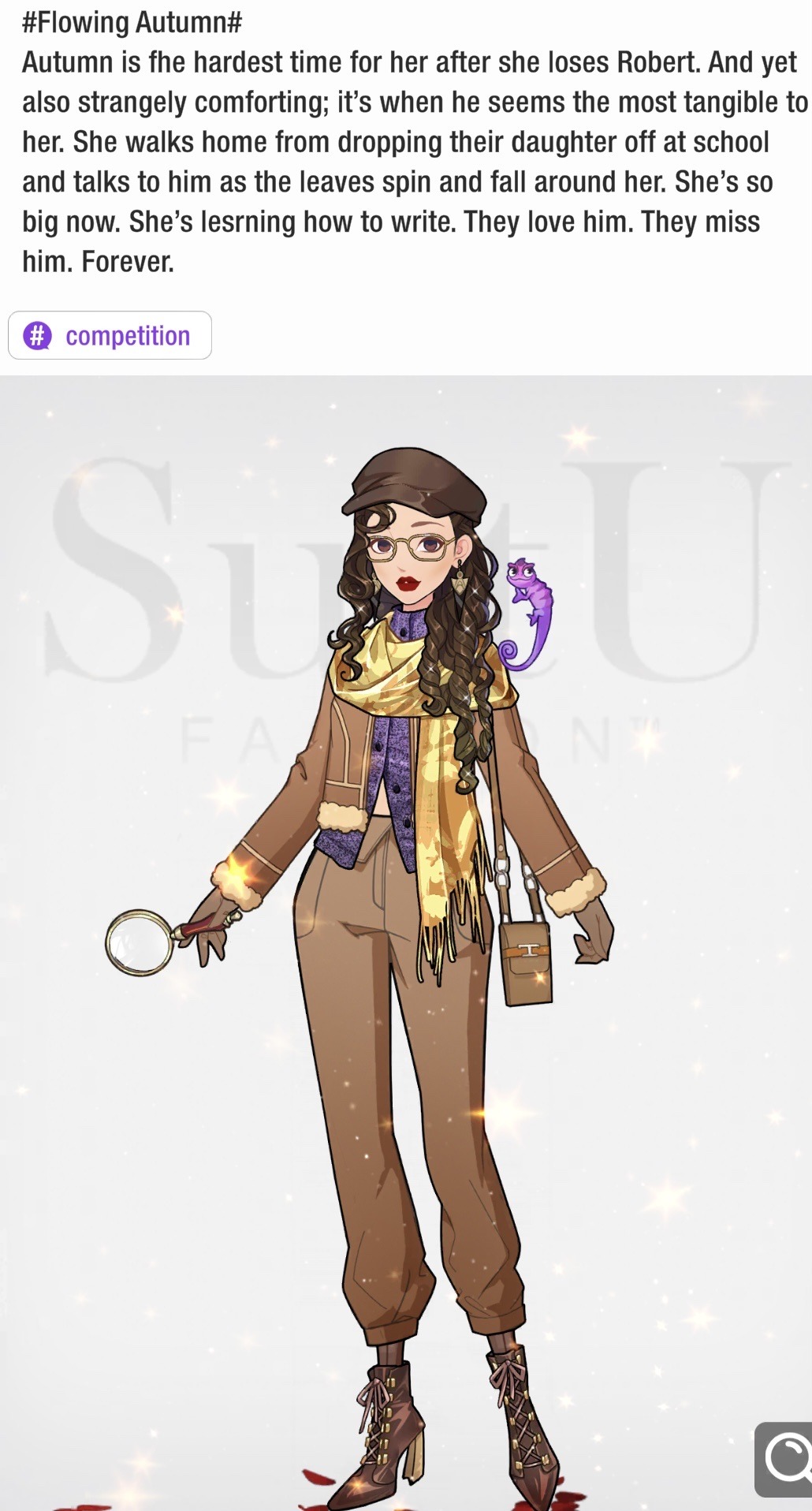

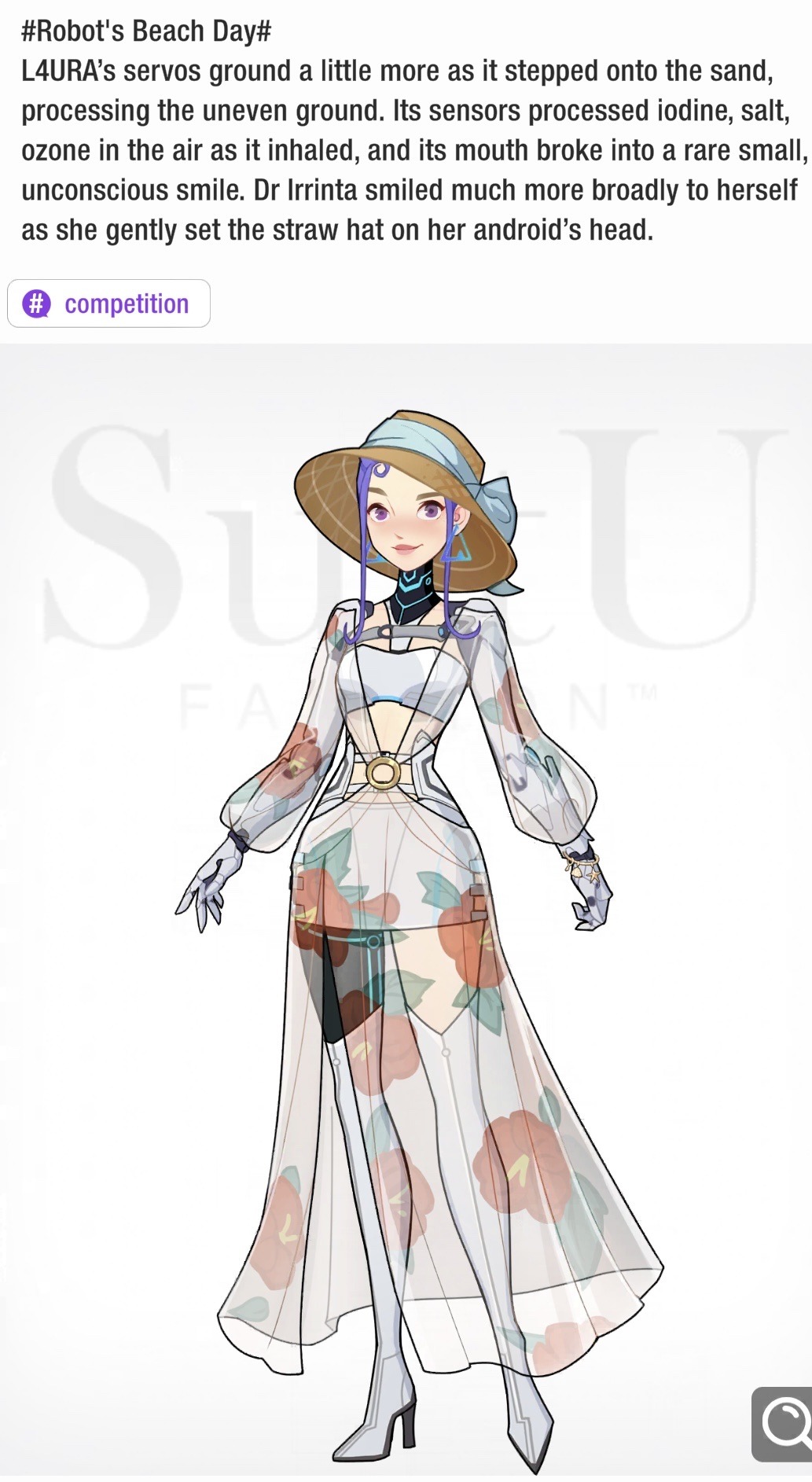

More SuitU dressup game ficlets

I have a feeling Lisa and Maria are going to show up in my other fiction somewhere now because Lisa leapt fully-formed into my mind as soon as I realised that joy in her face was gender euphoria and knowing her sister will kick any relatives who are shitty to her out of her wedding without a second thought ❤️

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

So because I’m weirdly addicted to dressup games, esp when I’m really not feeling well, I’ve been playing SuitU again.

Since it only allows you to post 500 words with your outfits in your game feed, I’ve been writing super short stories when posting each competition outfit.

Click on the pics to read each tiny story, if you like.

They’re basically snippets that come to mind on looking at the finished picture. So ofc, because it’s me, a lot of them are queer AF

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

So @underwaterstrawberries asked if they know she’s sapient.

The thing is; we know, and are discovering constantly, that all the metrics we used to use to delineate human exceptionally…are not actually that exceptional.

It’s not only humans, or even great apes, that use tools. Corvids use tools.

Octopuses and dolphins have self-awareness.

So these giant aliens that cared enough about a little wounded creature they found to pick it up, save its life and care for it - definitely seem to recognise that humans are bright tool-using creatures with a complex social structure. The way we recognise that, for example, in Corvids, or raccoons.

Whether that translates to “sapient” in the minds of these huge beings who can travel between stars? That may well be a more complex question.

Let’s give our human a name. Let’s call her Layla.

She wakes up lying on a big cushion about 2 metres square, with a pile of heavy soft covers on it.

There’s a crackling scent of ozone in the air, but everything otherwise smells clean, in an antiseptic way.

Her climbing rucksack is lying near her, which is nice because it has clothes in it, and while she’s clean, dry and warm, she’s not wearing any. Her last memory of the ones she was wearing as that they were very badly torn and soaked through with blood, to be fair.

Her legs aren’t broken. The red streaks she was worried she could see in her exposed flesh through all the rips in her trousers certainly aren’t there any more. All the cuts and bruises and fractures from her involuntary trip down the mountainside are no longer there.

She seems to be in some sort of container three or four metres across, with a texture oddly like cardboard. Next to the cushion are some big bowls of food - some big fruits she doesn’t recognise, a bit like melons, and some big crispy square things that smell a bit like crackers - and one of water, which she needs to scoop up in her cupped hands to drink.

Climbing onto the cushion to see over the big cardboard walls, she sees a vast pale room as big as a cathedral, filled with humming shapes whose purpose she can’t even guess at. Giant shapes walk through it intermittently.

One of them comes over often to see her, leaning a huge face over the box. The first couple of times she hides when it comes over, but she swiftly stops when she realises the worst it does is take away the food containers and the closeable bucket in the corner, bringing back fresh ones.

She gets bolder. She yells up at it in English and Spanish and Arabic, the only languages she knows any of, demanding to be let to go home.

She’s not sure it even hears her; when it moves its mouth, she mostly hears a deep rumble that sends vibrations through the cardboard and her whole body.

When she collapses and cries on the cushion in anger and exhaustion, it extends a great limb down to her cautiously and - very carefully - strokes her hair and down her back with a long digit, withdrawing when she shakes it off, but trying again after a couple of minutes.

She falls asleep eventually, and is woken by a sensation of movement. She is still on the cushion, but it is being carried by what she *thinks* is the same huge creature. When she moves around to find something to cling to, it cups the big digit around the cushion carefully, and she grabs at warm skin with a faint covering of hair she can only just see so as not to fall as it walks through *vast* spaces lit with pale, diffuse lighting that makes it difficult to see any details.

It moves into a different space; still huge, but with dimmer lighting, more colours she can recognise. It puts her down on a soft surface a bit like very thick soft roughly-woven fabric, carefully not moving away until she lets go of it. They put up a barrier of some kind around her; big open-weave panels of some kind.

She doesn’t notice them properly because that’s when she sees the three human faces staring at her from different parts of the great vast room.

So the story I really want to read is: space humans are *cats*.

You’ve got big, long-lived aliens that come to Earth pretty regularly by their timetables; say once every 50 years or so? Say they’re about 4 metres tall and their regular lifespans are about 600-700 years. They come in quietly and at least visually screen their ships because they don’t like disturbing the environment and the wildlife. They mostly come here to mine some mineral that’s rare on most other planets that’s useful to them, and maybe they do a little light environmental surveying on the side or maybe they don’t.

Your human protagonist is someone doing some climbing somewhere pretty remote who has got herself in a bit of a pickle; say she’s fallen badly while climbing a mountain alone and is trapped with a broken leg, when one of the aliens finds her - badly injured, badly dehydrated and with no way of getting help - while setting up their mining equipment.

And they do what a kind-hearted human would do if they found an injured feral cat or an wild animal of similar size; it picks her up, carries her aboard their shuttle, and, after what looks like some mild arguments with the others, takes her aboard to some sort of medical bay.

When she wakes up, she’s incredibly well-mended - possibly with some chronic illnesses fixed too - but is light years away from home. She has been adopted by this ship full of kind giants as a pet

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

So the story I really want to read is: space humans are *cats*.

You’ve got big, long-lived aliens that come to Earth pretty regularly by their timetables; say once every 50 years or so? Say they’re about 4 metres tall and their regular lifespans are about 600-700 years. They come in quietly and at least visually screen their ships because they don’t like disturbing the environment and the wildlife. They mostly come here to mine some mineral that’s rare on most other planets that’s useful to them, and maybe they do a little light environmental surveying on the side or maybe they don’t.

Your human protagonist is someone doing some climbing somewhere pretty remote who has got herself in a bit of a pickle; say she’s fallen badly while climbing a mountain alone and is trapped with a broken leg, when one of the aliens finds her - badly injured, badly dehydrated and with no way of getting help - while setting up their mining equipment.

And they do what a kind-hearted human would do if they found an injured feral cat or an wild animal of similar size; it picks her up, carries her aboard their shuttle, and, after what looks like some mild arguments with the others, takes her aboard to some sort of medical bay.

When she wakes up, she’s incredibly well-mended - possibly with some chronic illnesses fixed too - but is light years away from home. She has been adopted by this ship full of kind giants as a pet

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Three of Swords

A hard beginning under harsh circumstances. A light-skinned baby born to a tall ebon-skinned woman in her thirties with a beautiful, closed face. She speaks five languages and can embroider in stitches the size of a full stop.

She belongs to the McNamara family with the same worth at auction as one of their five sons’ saddlehorses, even this late in the war, and the little bundle she hands to Old Jenny wrapped in a faded blue blanket has no man to call father.

The little bundle that is still only Promise joins seven other babies in baskets by Jenny’s hearth, and a gaggle of about twenty other little boys and girls too young to go out to the fields as yet tumbling on her scrubbed boards or in the red Earth of her yard. Some of them are picked up by men and women half-crippled by exhaustion every night as the sun goes down, but she joins five or six others who are only rarely - if ever - visited by women from the Big House.

*****

Before she is two years old, the Big House is a smoking ruin and a third of the children who shared Old Jenny’s floor with her are dead of the cholera that sweeps through the land with the Union army.

The Ace of Wands

Children still come during the days, though not so many. There are still fields, though not so many are under cultivation now, and more patchwork - some patches of potatoes and oats and yams amongst the white fluff of cotton.

Old Jenny has a garden the two of them till together, with some help from their older visitors. Half of it is potatoes, carrots, turnips, okra, plantain - everyday foods that appear on the table. The rest, however, are herbs - flowered and none, sweet-smelling or musky - foxglove, yarrow, rue, lavender, rooibos, marjoram, ginger, all watched over by a yew that looks as old as the very earth.

Promise is not as tall as the broom Old Jenny uses to sweep her floors before she begins to realise that Promise has a knack with the herbs - how to nurture them, where they will grow best, when they are best to pick. She is a fingerwidth above it when she realises that she has the same knack with the people who come to Old Jenny’s door - sometimes in the day, sometimes in the dead of night - to ask for her help in healing. Sometimes with the herbs. Sometimes other ways.

The Mother of Mercy is painted over Old Jenny’s bed, her eyes and her robe as blue as the heavens, and the rod and snake in her hands as brown and green as the earth.

The Six of Swords

Promise is sitting by that same hearth trying to get a flame to catch on damp, smoking sticks as she listens to Old Jenny and Esther, her mother, arguing in the kitchen.

Esther’s visits usually mean treats and tension between her and Old Jenny. They don't usually mean open fighting. Promise knows questions rarely get answers, so simply tries not to think about it, even when she finds herself sleeping with Old Jenny that night, instead of with Esther as she usually does on her visits.

Only when next day sees her leaving with Esther, in a near-new green dress too long for her and the first real shoes - not work boots or cloth moccasins - she has ever owned, does she understand.

Esther works for a tailor. Her work is finer than that of Miss Juliet, the other girl, but she never takes the wealthier customers off to the side rooms for measurements and fittings, even though she usually ends up doing most of the work on them, and her pay is just over half, because Juliet has blonde hair and skin like half-churned milk.

Promise fetches and carries, sweeps the floor, dusts the counters, moves the bolts of cloth, takes deliveries, wraps parcels, threads needles, sews on buttons, brews coffee and delivers finished dresses, all for 10 cents a week. Esther drives her on to improve her stitching and learn her letters, sitting up late into the night in their room by the light of the oil lamp. Esther is hard and unyielding as she drives her forward. “Do you want to end up working in the fields?” she demands, when Promise’s head droops on the table in front of her, bitter tears trailing down her cheeks. “You have the chance to *be* someone now. I won't let you waste it!”

The High Priestess

The knack still shows no signs of going as Promise starts pinning her braids up and wearing her skirts down to her ankles. Sometimes it's simply knowing the mix of tea that Esther will need for her hot flashes or her aching finger joints. Sometimes it's knowing that Mrs Fanshawe will not be needing the nursing corset they are embroidering with apple blossom for her because the baby will come out with a heart that flutters in his chest like a white dove, and will be in the ground three days after she is brought to bed.

Sometimes it's the knowledge that hits all of a sudden when Promise is in the street one morning on the way back from a delivery that Old Jenny, now grown frail as a cobweb, has not been able to rise from her bed that morning, and suddenly dropping her umbrella in the street and heading up the road towards the country as though summoned.

She manages to catch a ride on an empty cart going home from the city, and makes it there while the sun is still in the sky. She knows as soon as she steps over the garden gate that there is no point in hurrying any longer. Instead, she stops and bends down, burying her fingers in the earth, and finds herself weeping, shaking with sobs that wrack her body, for a long, long time before she goes in to light the candles around Old Jenny to keep her safe while she goes for the priest.

0 notes

Text

CW oblique reference to pregnancy loss

Your plaintive cry

Ringing through the quiet when I am in bed

Calling out

With no expectation of disappointment

Your little soft dark head against my arm

As I turn the shining silver tap to

Produce the tiny perfect liquid stream

For your little deft black paw to shoot out

In reflexive delight of batting play

As your contentment brrrrrrrrrrs through my bones

Your swift leap when your thirst is sated

Waiting for me

Outside the bathroom door

To curl and rub

Your soft vibrating body against my ankles

Stretching out into a confident guiding shadow

That leads my pained and faltering steps

Back to the bedroom

Where you leap

Soft surefooted shadow

To pad pacing me on the windowsill

As I set aside my crutch

And drop bonelessly

Into my bed

Where another tight coil of soft-shadowed fur

Opens dark eyes and curls closer

To lay the weight of her head on my shoulder

Watching for you

To leap across

And pad love in soft heavy steps

And tiny spikes of sharp pain

Over my body

I am so gently weighted down and pinned

Love seeping and vibrating

Deep into my bones

There are times I let myself indulge

Oh so fleetingly

In thoughts that you

Could hold the little

Animal sparks that oh so briefly

Settled in my womb

Which could not cradle and shield

As I so heart-deep desired;

Allow myself to wonder

Might souls travel in groups

Endlessly seeking and

Returning to each other

Across the vast gulfs of moments and centuries?

And then I put those thoughts away

I will not cheapen

The vast and infinitely courageous love

That shines out of

Little bodies

By casting it other

Than what it is;

Your love is chosen

Infinite,

A tender thread across long centuries

Crossing boundaries of blood and flesh

Our species’ ancient pacts

Made endlessly anew and

Each time a tiny miracle

Undeserved blessings freely given

From great hearts.

#poetry#spilled poetry#chronic illness#disabled poet#doggo#pupper#kitteh#cats cats cats#cw pregnancy loss

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silent Night

If I had known what was going to come afterwards - would I have done anything differently?

Yes. I think a lot of us might have.

It started with the music. There was a hush in the frozen air as the guns fell silent. Then the sound of carols being sung floated slowly across to us in the dawn mist.

A different language, of course, but a familiar tune. And even the language wasn’t so alien. I learned those words in Sunday School as a lad. I sang them with our church choir every Sunday of Advent for all the years of my boyhood before my voice broke. Before it was the language of the enemy, German was the language of Father Vessau, our old priest. I’m glad he didn’t live to see any of what came later.

It was the familiar story of the Virgin and Child, of course, but it was so perfectly still, so quiet other than the haunting voices floating across the trenches, that it seemed written for this very moment.

Perhaps that was the reason I stood up, clambered out of the trench onto the frozen mud and blood and stepped out amongst the coils of barbed wire. I waved my empty hands and yelled “Hello! Merry Christmas!” into the still air like a child going out on Christmas morning. The earth was scarred and torn up, dotted with deep pits and holes where the water had frozen into hazy cracked glass. Earth stood hard as iron; water like a stone. Even walking deliberately slowly and noisily, letting my footsteps crack and echo, I was nearly halfway across the space between our trenches in a few moments. Such a ridiculously short distance to have been an uncrossable chasm for so long.

And on the other side, someone else was doing the same. The pale sun glinted on cropped blondish curls as a young man about my own age climbed above the parapet and waved back. “Hallo! Fröhliche Weihnachten!” His pale face split in a grin as he started walking towards me, picking his way just as carefully between the coils of wire and the deep divots in the frozen earth.

We met somewhere in the middle and shook hands. He looked pale and his blue eyes were weary, but bright with strange wonder at the stillness of the day. His hands were warm, and I remember noticing he had beautiful teeth in his beautiful smile as we handed each other cigarettes and lit them, the smoke curling up in the still air.

Then my mates were coming up behind me. Bill, and Alec, and Bob, and Davey. Other men came up behind the man I was sharing a cigarette with too, appearing like spectres before coalescing into tired young men with hesitant, hopeful smiles, all touched with the same odd wonder I could feel on my own face. There were handshakes and cigarettes being passed back and forth as the sun rose and the mist cleared. Someone brought out a bottle their mother had sent them for Christmas and passed it round. The warm scent of whisky carried in the stillness on smoking breath, overlaying the old faint notes of blood and cordite still drifting on the air.

We lit a fire and stood around it, giving each other tips on how to keep it going in two different languages. People scrounged up some halfway potable water, boiled a kettle, started a brew-up. Everyone handed round sweets, more cigarettes, pieces of bread loaded luxuriously thick with jam. Someone brought out a squeezebox and someone else a trumpet and they began to play carols. Halting missed notes sounded magical in the still air. People passed around photographs of girls and children, parents and dogs. Later on, someone brought out a makeshift ball of rags and newspaper and some of the lads began to kick it about together on the frozen earth.

The thought came to me as I stood there, my hands warmed by an old tin mug with the German words on it almost unreadable under scratches and dents, that maybe we had all died at some point in the last terrible night under the incessant thumping and screaming of the guns, and this was heaven. That the burden of life and nationality had passed from us all quietly in the darkness and now we were all just men again, being simply human in the silence.

The young man whose hand I had shaken stood nearby, still smiling shyly. My schoolboy German was only sufficient for a few halting phrases, and he spoke even less English than that. His smile, however, was warm under a rather fluffy blond moustache - I sympathised; despite manful attempts to encourage it by shaving twice a day, my own upper lip was barely more than shadowed still - and his eyes, though red-rimmed with cold and fatigue, were as softly blue as the summer sky and immensely, brightly alive in his pale, chilled face. They seemed to get his point across almost by sheer force of life in them, even when words, hand gestures and pantomime failed.

His name was Mikel. He showed me a picture from the inner breast pocket of his coarse grey greatcoat - his mother, a sweet-faced, slightly stout woman with greying hair climbing softly out of two coiled braids, and their dog, a proud-eared little bull terrier, in front of a little white-walled cottage with a plum tree by the door and a mass of flowering wisteria climbing the walls. His father had died when he was small, he told me, and his mother was all alone now except for him and Schon. I felt in my own breast pocket for my cigarette tin. While I was lighting our cigarettes, I showed him the photograph my own parents had taken of us all just after I enlisted. My father, balding, thin and dignified; my mother, dark-haired, thin and anxious with her hand on my arm, carefully, carefully not clinging. My three little sisters stiff in their Sunday best dresses, except for little Elsie grinning, eternally unladylike, her beloved smile undimmed by the faded print. Mikel’s face split in a grin just as warm and unselfconscious as his eyes lighted on it.

At one point, I walked off to take a piss behind a hump of tortured earth. As I was doing up my buttons, I looked up and saw Mikel doing the same. His blue eyes met mine, and then his warm lips did; there were dozens of men not twenty feet away and we could have been the only two people on Earth in that moment. I folded him in my arms as I kissed him back; he was thin, the bones of his ribs poking into me through his coat. His hand was cold in mine then, and I squeezed it tight briefly before we separated to come back to the others our own ways.

There was a moment as darkness began to fall when I thought We don’t have to go back. I could see the thought in the faces of every man around me, British and German alike. We looked at each other silently. The twilight muted our khaki and their grey uniforms to indistinguishable dark shapes in the dusk, with pale blobs of faces floating above them. All I could see, looking around me, were people. I looked across and met Mikel’s eyes shining bright out of his face in the gathering darkness.

Merry Christmas, Pip, he mouthed to me silently, smiling sadly.

Fröhliche Weihnachten, Mikel, I mouthed back to him, still tasting his mouth on mine. It was like another kiss exchanged across a few feet and a vast distance, in front of a hundred other men.

And then, achingly slowly, we all turned and trudged back, back to our trenches and our lives and our enemies.

Bill and Alec were dead by next Christmas, and Davey was back at home with two fewer legs than he had left with. We never had another Christmas truce. Miracles only happen once, and are not repeated when you lack the courage to accept what they offer you.

I thought of Mikel often in those other Christmasses, the ones with no truce and no silence in them. And plenty of other times besides as I stood staring out across that little space of broken earth that had once again become as wide and perilous as the great grey sea. I would light a cigarette, cupping my hand around it to shield it from a sniper’s sight, and taste his lips on mine again with my first inhale. I was offered sniper training myself several times when different sergeants picked up on my quickness of hand and eye. It would have meant a little more money to send home to my mother, struggling to feed and clothe the girls after the influenza took my father, but I always managed to find a way out of it. Snipers had to see the faces of the men they shot as they killed them. It would have killed me quite as sure as any bullet.

Did I kill Mikel, I often found myself wondering on those long days and nights filled with the ceaseless pounding of artillery, with any one of my hundred terrified blind shots into the darkness? Was he out there still, less than the length of a football field away, just as cold and terrified and alone as I was? Did he ever make it back to his sweet-faced mother and his jaunty little dog waiting for him by their little cottage under the apple tree? Or did one of those anonymous grey-clad corpses hanging on the wire after any one of a thousand forays have soft blue eyes like the summer sky above Pitlochry before they glazed over forever?

I could have tried to find out, after it was all finally over. I had an empty sleeve and several long-service medals by then, and no man would ever have called me a coward, but I never found the courage in myself to look up his name on any of the German casualty lists that came through, or to try to write to him through any of the international Veterans organisations I joined later in my life. I only ever mentioned his name to my wife Emma once, when I woke shuddering and sweating after a Bonfire Night when our grandchildren were small. The air was full of cordite and screams, and after I finally succeeded in finding sleep I ended up dreaming of him standing bloodsoaked and silent and sad in the mist a few yards from the edge of my trench.

I think of him still. Emma died a few years ago, and I don’t sleep well these days without her warmth beside me, even with my faithful little bull terrier Sasha curled up at the end of the bed by my feet. I often wake long before the dawn and am quite unable to find sleep again. I end up staring and smoking, watching the horizon outside my window turn slowly to grey and gold. Like me, Sasha is getting on these days, and her dicky bladder wakes her with the sun. On winter mornings, her arthritic old bones wake her even earlier, and I get to watch it rise with her trotting along beside me.

As I walk, I light a cigarette, cupping in my hand as though to shield its light from being seen, even though there’s rarely anyone but me out there. I touch the match to the end and inhale, and once again I taste his kiss as though it were Christmas morning once again, and a different world waiting for us there if we had only had the courage to reach out and grasp it.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is no need

to rake

the brown corpses of leaves

from your winter grass

or cut away

the pale bleached skeletons

of summer flowers

from your garden

once the pulse of life has fled them.

Beneath those slow-vanishing heaps

and within those bleaching, drying stalks

pollinators dream away

the chill and harsh winds of winter

or pupate

snugly tucked away into new becoming.

And the stuff that *was* life

leaches from those fading piles and natomies

into the sleeping chill

of the winter earth

as they cover it;

and amidst the continuous chemical threads

of the mycelium networks endless communication

germinates a new note in that great slow symphony

ready to burst forth

into the glad new notes

of spring’s green.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

I still think about my last pregnancy a lot.

They’d be at primary school now

if they had survived to become a person.

It’s funny how I picture the heartbreak

nearly as much as the other stuff.

I pictured shaking with exhaustion

when they were a tiny baby

and having cracked nipples from breastfeeding

and worrying about painkillers in the breast milk.

Later, I pictured trying to carry them up the stairs on my chairlift,

juggling them squirming in one arm as I kept the lever down to move,

that horrible, ever-present terror of dropping them,

that bit of my brain that hates me

supplying the sound of

soft toddler bones cracking on carpeted stairs,

Juggling my crutches with their pushchair on good days;

trying to manage carrying them in my lap

while propelling my wheelchair on bad ones.

Would they have been resentful that I couldn’t

run around with them as much

as I wanted to?

Of days I had to lie in bed shuddering for hours

after I crawled to the toilet

or had to wait for their dad to get home for proper food

because my hands were shaking too much

to be safe with anything not microwaveable?

Would I have simply been Mummy

Or tried out a variety of ungendered terms

until we found one that worked for us?

Would their nonbinary parent

suddenly have become a terrible

embarrassment to them

at some point?

Or would it have been so obvious and

central to their little world that

screaming terfs would have seemed

beyond nonsensical to them?

Now I picture

phone calls from their school

on days when my other half is out on audit

and I can’t get out of bed without vomiting in pain.

Trying to call them a taxi

lying down with my eyes shut and

nothing coming out

but a jumble of unprocessed word salad.

Fighting for accommodations

we technically won last term

and yet nothing seems to have changed.

It would have been horrendously hard,

and I still very much wish it had happened

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nine Fingers

It still amazes him that he goes entire days without thinking of the war.

The farm is busy, though. Every day and every season, and part of the point of a co-op is that the burden and the joy of planning falls on everyone as well as the legwork.

And so, slowly, all the moments where memories used to rise up into like mist from damp earth have begun to fill with thoughts like We really need to cut back the cranberries this year; they’re getting leggy and I don’t want to start having think about stilts to pick the top ones; We’ve got so much sileage this spring, I wonder if the Selvars over the valley would swap a couple of their black-eared kids for some of it? or even just Oooh, a couple more days and those little pea pods will be just perfect to eat from the vine.

And he has a few regular partners now, not all of them from the old platoon; Annalise over from Selvars and David, two years in the co-op now, to go along with Reev and Alma and Zou. He doesn’t even think Annalise served; she is five or six years younger than him. A lifetime, in its way.

But what it means is that his nights and mornings are more and more frequently filled with chatter about the chickens or the nut trees, the teams on the local ball league or the serial they are all listening to on the radio along with warmth and kisses and pleasure. And even on the mornings where he wakes up alone the farmhouse is full of gentle noise, people to feed, and a gaggle of hungry fowl trumpeting their displeasure from their safe coop.

It does not mean he never wakes screaming in the night with his ears full of screams and bangs and choking breaths and his nose full of the stench of blood and ordure. Or that he is never woken by the screams of any of the others. Reev still has choking night terrors that leave them frozen and hard to wake, and Zou still attacks him in his sleep, occasionally; leaving bruises and welts and scratches that horrify him when he wakes. But they are all growing rarer over time. Weeks of peace and forgetfulness.

It is his turn to look after Emzy today. He used to dread that, when she was very small and a great deal of it involved walking her between Alma and Ru for feeds; terrified that any moment he looked away from her she would do herself a terminal injury. Now, when she is a chubby and robust 20-month-old, the danger of that is materially far greater; he occasionally wonders how humanity survived this long when a critical developmental stage seems to involve finding every possible new and exciting way to potentially kill oneself while giggling loudly all the while. But now he has somehow worked himself to loving his days with her, even if he is frequently more tired afterwards than after the hardest days of fieldwork.

One of her favourite games is luckily less potentially lethal. Pat-a-cake, David called it when he taught it to her, and by extension to all of them. She is beginning to babble the little rhyme that goes along with it; a wordless chuckle of sound that is like the unleavened dough of words.

It seems to have awoken her to the fact that she *has* hands. She likes to sit with her little fat legs stretched out in front of her, his long scarred ones spread out to make room for her and tiny chubby starfish hands spread out palm to palm with his. After rounds and rounds of Pat-a-cake finally loses its appeal, he has started counting fingers with her. One, waggling his thumb against hers. Two. Three.

Eventually, of course, they get to Nine and he has no finger there to waggle against hers, point at her with, or end up as a chew-toy for her budding gums. Just the stump, not even reaching the first joint. It had been longer, once, before the surgeon neatened it up for him, but he was grateful for their work - he had much better use of that hand now. Every time they get to Nine, and she still looks at her tiny soft finger rising alone above his stump with wonder. Until he distracts her by gently bumping his forehead against hers or blowing in her ear to make her giggle, and they go on to Ten.

One day she will likely have the words to ask about that. Why she has ten fingers and he has only nine. Why Ilma has a prosthetic leg that they still keep having to try to adjust to ease her stump, and Reev’s eye sometimes gets interference from their little harvest drone signals. Why all her parents carry scars, and how they met, and how she came to be.

He hopes by then that he - that they - might have better answers for her.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

There were four brothers in the Great War. Now there are four white headstones in Brynhill Cemetery.

Gareth was the eldest brother. 17 when he joined up, before the draft; heroism on his mind. The drums of war beating his steps as he marched away from the mines and the coal dust in his smart new uniform. And yet it was a mine that took his life; not ten days after he arrived. A careless step in Flanders’ fields; a swift and sudden ending in terrible light and sound.

Rhys was the second; the quiet boy, not his mother’s favourite, as Gareth had been with his bright blond curls. The eldest brother now. He had gone down into the darkness in the coal mines to do a man’s job at 14; but not alone. Always following Gareth. Now he was alone.

He stayed at home to look after his mother, coughing her life away on ruined lungs in a damp bedroom; to look after his little brothers; bright boys, growing like weeds.

Until in 1916 the draft came and took him; not ten days after his mother’s funeral. Took him to those fields sodden with his brother’s blood and those of a million other men.

He kept his head down. Survived. He had promised Gareth he would look after them, you see.

And, one by one, his brothers joined him. Thomas came to his regiment; he was glad of that, at least. He could look out for him there.

Dafydd was a bright boy, now, the brightest of all of them. Got a job as a driver, ferrying the higher-ups about. They were so glad for him. Better food; sleeping warm, but most of all, no trenches. A safe bed for their little brother.

Rhys and Thomas, though, they were on the Western Front. In shellfire and bayonet and gas. Time and again the cry went up and they and all their mates pulled those heavy canvas hoods over their heads like divers and stood like their own ghosts, watching the waves of yellow and green passing over the trenches like the ghosts of the waves.

Until one day when the waves passed over and Thomas began to choke and cough.

Rhys was good with machines and devices; had worked them below the ground since he was a boy. He thought something must have come loose; fumbled with the filter, gentle words to keep his brother from panic as he tried to fix it. And then, in the end, he pulled the hood from his own head and forced it over his brother’s.

There was talk of court-martial and of commendations and medals in the hospital; he gave not one fig for either. He only cared that he had not been fast enough; Thomas grasped at his hand as he drowned on dry land in the next hospital bed. His eyes already burned white.

It was still with his sight - though with a wracking cough that never left him - that he was sent back to his unit; a medal too, little as he cared. The letters from Dafydd kept him afloat over the next year; he was less and less at the front and back in hospital more and more, as the damp dragged at his ruined lungs. Dafydd, that sweet boy, sent him something every day in hospital - sketches and postcards and tins of chocolate from the Brass’ mess.

That was probably how the telegram found its way to him so fast. A day of silence and fear, and then that buff envelope in the nurse’s hand.

And the end of everything.

The guns went off for the Armistice not a week later and he turned his face to the wall.

He hung on a little longer - even an empty life is a hard habit to break, and the nurse was a little thing with big sweet eyes who had seen too much. He just…couldn’t bring himself to die on her. She went home on leave, finally, and he smiled goodbye to her and shut his eyes, and just…stopped.

The peace at the end of all things. And four white stones in Brynhill Cemetery, where Winter waits.

#four headstones#where winter waits#ww1#the grear war#a queer crip writes#remembrance#remembrance day

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It’s not you that’s unreliable; it’s your health”

the meme says; it means it kindly, of course

to spare the complete and responsible human

struck down by blameless calamity

the burden of judgement,

but the absurdity of it strikes me continuously

As if “my health” were not me;

as if it were an entirely separate

creature that writhes

stuck to a couch by sweat

bands of iron pain narrowing its world to an oubliette;

as if it were its limbs filled with lead and turned

water-weak on broken-elastic joints.

Not me at all.

The truth of course is sadly

that I never really achieved “reliability”;

though not through want of trying; when

my health and I were indivisibly one thing

I mostly achieved a decent semblance of it

by dint of doing three or four

times more work than genuinely reliable people

for a slightly wonkier result; working

myself to panicky exhaustion

(or what I called exhaustion then)

for the privilege of achieving Talented But Lazy.

I never truly appreciated how

much I achieved by Just Doing More

until that was no longer an option; how

very Unreliable I became when

I could no longer throw everything

at a Simple Task Anyone Could Just Do

until I broke it through the raw weight of effort

Now, of course, I am indisputably Unreliable.

One manages chronic fatigue by pacing;

I laugh gut-wrenchingly at this often

There could hardly be a thing

more alien to my nature, or indeed

my learned survival techniques; but it is

the only way out of the oubliette, so

I push it like a stone door slab,

shifting, winning scraps of life by

bleeding-fingered inches.

Once again, the hardest work

possible to achieve

Laziness and Unreliability.

#poetry#poetrytober#spilled poetry#disabled poet#neurodivergent poet#chronic pain#chronic fatigue#chronic illness

30 notes

·

View notes