Text

Loser Ranger is my new obsession

I did not expect to be particularly into Loser Ranger when the first episode aired. Sure, the prospect of an edgy super sentai show by the same author as The Quintessential Quintuplets is very funny to me and every time someone says “this is the X story of X media”, in this case the “The Boys of Anime” I instinctively remember all the dozens of times someone in the internet called anything “the Game of Thrones of whatever” or “the Dark Souls of insert video game genre here” and I roll my eyes. So I watched the first episode and then the second one and I kept going. My take on it at the time was that it was just an okay show. I liked the idea of an anime that harkens back to my childhood days watching Power Rangers on brazilian television, though I was never particularly a fan of super sentai and I entirely left it behind during adolescence, I was still a kid that watched kid’s shows. I liked the corny action and the stupid arguing when it came to deciding who gets to be which ranger when playing with other kids.

Subverting a structure where conventionally the good guys are fighting the monsters to make the monster be the good guys could just as well be nothing more than a gimmick. I mean, it is something, but it is not groundbreaking by any means. The anime also doesn’t look particularly good, though the OP is pretty fun. Was I surprised to see that the studio who created Arknights, the only actually good gacha game, was animating it? Sure. Does that mean jack-shit about the quality? No. Why am I even talking about this? Hey shut up it's my script.

All of this to say that things changed once I reached episode five, in the process thinking that the blonde girl called Hisui looks kinda cool and I wanted to see how the ongoing fight concluded so I read the manga, only to be immediately hit by that pathological girlfure looking cooler by the chapter, then proceeded to find out that after an okay introduction it has a good first arc then there is a HUGE quality spike with the School Life Arc and it doesn’t drop the ball after that (except for one little thing but we don’t talk about that), PLUS, now Hisui lives rent-free in my head.

Let’s start from the beginning.

Thirteen years ago a giant fortress appeared over Milky Way City in Japan. The residents of that fortress started invading the surface and humanity fought back, forming the Rangers and retaliating. Every Sunday they come to the ground and are fought by the Keepers — the five main Rangers — in a stadium, with an audience in a televised event. If it sounds dumb and artificial that’s because it is. The Invaders are shapeshifters who were forced by the Rangers to take on this acting role after their overlords, the Executives, were all defeated in the very first year of the war, thus making them slaves to a bunch of sociopathic celebrities.

Enter Footsoldier D, an invader who is fed up with their situation and decides he is going to take matters into his own hands and get revenge on all the Keepers. Things start spiraling out of control almost immediately though D doesn’t know it yet, as he meets two rangers called Suzukiri and Hibiki. One who offers to help him take down the big five by stealing their weapons and another who wants to change the Ranger association from the inside out as he believes humans and Invaders can coexist. One of the reasons why this manga eventually becomes so entertaining has its beginning here, as this is one of those stories where there are plots within plots, lies within lies and everyone has something in particular they want to protect or achieve even if that means coming into conflict with both sides of the war. After some shenanigans Footsoldier D takes Hibiki’s place to infiltrate the Ranger Association with both of them vying to do their best to achieve their goals first, having just exchanged places.

This is where it starts going from decent to good as the mysteries begin piling on pretty thick. What are the so-called Divine Artifacts — the Keeper’s weapons — and why do they not look like something that was constructed but organic? Why does Suzukuri want to collect them? Why is there another invader living inside Hibiki’s closet? Why do the Rangers have such a lackadaisical approach to their leader being a murderer? How is D ever going to have any shot at killing these monsters when we see so clearly how much more powerful they are and his training is so basic? You might be thinking that I’m dumb and that the answer is powerscaling, but this is actually the action manga with the least amount of powerscaling I have seen yet. Character’s stay at roughly the same power level they are introduced in for several arcs and only manage to get things done by being smart about it and working together. Every conflict going forward is going to be multiple chapters long and feature a dozen different characters that all bounce off of each other. Essentially everyone in this story would be dead by the end of the second arc if they didn’t fight in groups 90% of the time.

What I have been calling the good first arc is basically the chunin exam of this manga. When you join the Rangers you do so as a filthy colorless and have to train until you are eligible for a test. Judging the results of said test you will be assigned a squadron based on each Keeper’s color or remain a lowly colorless fuck.

The circumstances under which this plays out are actually very engaging. D is posing as Hibiki taking the test, which means there is a lot about the Rangers he doesn’t know and he has to be careful about not getting hurt as it would immediately expose him as an Invader. He has to take care of XX despite that not actually being his responsibility, except that he also has a big sister now which is the Pink Keeper herself. Under these circumstances he has to compete against people who have totally genuine reasons for wanting to become Rangers, such as Shion who wants to get revenge on the Invaders for killing his brother who was himself a Ranger, but since both of them want to join the Red Squadron and they are in the same test only one of them can pass despite both having perfectly understandable reasons for wanting it. All of this further escalates as characters who are all easily distinguishable betray each other for their own gain, giving a hint as to why this organization is so fucked to begin with when they advocate for so much competition between their new members, who then get involved in a real battle with one of the Executives who was supposed to be dead and before you know it one of the big bad raidbosses is dead by the end of the first arc — which ends in CHAPTER FIFTY ONE — and even manages to be kind of a badass while doing it?

Every issue the characters have to face feel like a massive undertaking that, if you get into the story like how I did, will really surprise you because you were likely expecting something different when the first few chapters establish a conflict that is entirely artificial and unchanging with a main character that is literally immortal as long as he doesn’t go against a Keeper face to face specifically while they are wielding a Divine Tool. The actual mechanics of the fight might seem underwhelming, with most of the cast only having access to a basic-ass weapon for a good while, but the dynamics of each step along the way not only keeps it entertaining in a moment-to-moment basis, but also quickly builds so much of it there is enough foreshadowing, unresolved beefs and characters to cycle through for a story of near epic proportions. There is some sort of twist happening every other chapter, there are always characters making unexpected decisions, convincing one another to form truces or just committing mistakes, sometimes doing nothing more than being at the wrong place at the wrong time.

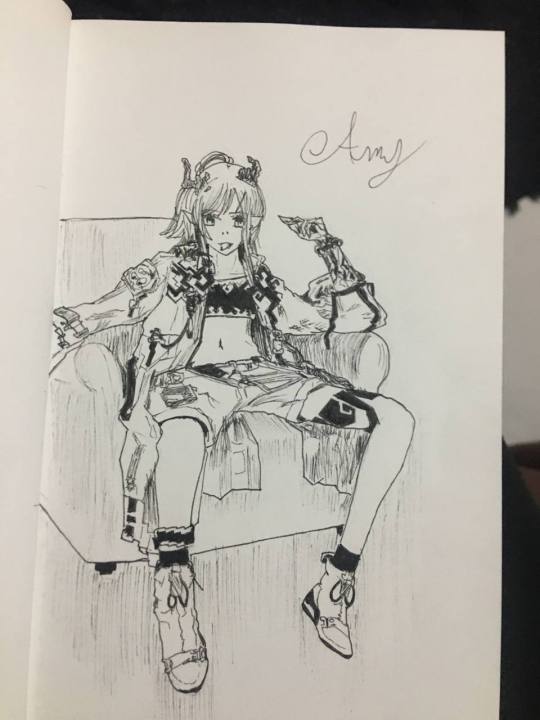

As the story goes forward it does a honestly very above average job of building on what came before. Though D is too dense to notice half of it and too prideful to admit the other half, he already gets everything he needs to start questioning his own goals and worldviews from this first arc, this is then brought to the forefront as the story pulls another twist, placing D not in the Red Battalion but in the Green one, bringing Kanon Hisui, the coolest motherfucker alive to the forefront. She is also my daughter. Look it up. It’s real.

I am infatuated by this character, everything she does for the story, her design and her personality. Through her, D is presented the harsh reality of a Battalion that is dedicated to dealing with the powerful Executives, which means that they are often being killed and replaced and the heroism necessary to walk through that to the other side, as well as the emotional damage and ruthlessness such an environment will instill. First we as the audience — but later D through his interactions with Hisui — get to understand that there is nothing inherently good or bad about any of these groups. That they are both made up of tyrants and their victims, people who were met with untimely tragedy, lost loved ones and parts of them along the way.

This arc takes place inside a school as an analogy to the lost youth and opportunities of everyone involved. Of the lives they were denied and will never get to live. Hisui is always wearing a middle-schooler uniform despite having no need for one as a way to maintain in the audience’s mind the fact that she doesn’t fit, that she is unwilling to let go of the concept of living the life she deserved despite that not being the material reality in front of her. D was quite literally bred for war and like the people who hate Invaders for the damage they caused them and their people, also hates the Rangers because of what the Keepers did to his peers which although fair, doesn’t take into account that he doesn’t know them. The Keepers aren’t the Rangers and the Rangers aren't humanity. They are both fighting in a makeshift war they were thrusted upon without their consent, are thematically brought closer by sharing in what was taken from them under the guise of a school life which is literally an in-universe dream; to then having to come to terms with the realization that they are one and the same; victims of a game played by rulers who are equally as vile, both of which should be dealt with. Geez, I wonder if the giant fucking chain casting its shadow over the city is meant to symbolize something.

Of course, they still hold slightly different allegiances, as D doesn’t let go of his plans to kill the Keepers but instead achieves a fuller understanding of his situation, and a lot of this is only going to get its payoff by the end of the next big arc, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

Building upon the reaction of “Hey this guy wasn’t so bad after all” of the Blue Keeper’s conclusion, the manga now first gets you used to a character before revealing their identity as a Keeper, instilling in you the question of whether or not we should even be rooting for D to kill this guy. Sure, he still played a part in the oppressing of the Footsoldiers, but we don’t even know exactly what led to that to begin with. Also, we did actually kill Blue Keeper, but they just went ahead and substituted him. Gotta kill the fucker again.

Remember what I said about the constant escalating of circumstances? This is what I’m talking about. This structure makes it so that the next question the characters have to deal with both feel like the natural next thing to happen while also being just unpredictable enough to have all the twists it wants, and the answer to that question is laid upon so many conflicts with potential ramification that it manages to be, I kid you not, morally gray. Yes, the edgy manga from the author of the quintuplets harem is genuinely morally gray to an impressive extent—for what it is, not in the grand scheme of literature. Fucking bananas am I right? This is going to sound absurd, but I don’t think I have seen a more organically built-up shounen since Hunter x Hunter.

Something else that the School Life arc has over the previous one is that this time the actual mechanics of the conflict are a lot more interesting, likely as a result of having the benefit of working with previously established powers and characters. The premise of a job that constantly kills its workers and the existence of an alternate reality inside a building that breaks physical laws also feels very Chainsaw Man, which I appreciate as that is one of my favorites.

Just like the Footsoldiers back in the fortress, these characters now have a set of rules they have to obey, this time in order to keep the school world from constantly resetting. A premise that is particularly interesting once you consider that these are all people who didn’t get to lead a normal life and that their reaction isn’t to simply accept them but to find ways to work around those rules, their obedience being just a facade. In a literalization of the metaphor, fully giving in to the dream world signifies a character’s loss, which appeals to them precisely because it promises to right the wrongdoings of their past.

The story recognizes this with the students that criticize them after being released from the illusion because that was their way to cope with their own injustices. It is sensible enough to not treat these people as simply stupid, after all we spent a whole arc seeing the reasons that a dream like that could be appealing through Hisui’s perspective, but the arc concludes with the recognition that while the path they are choosing is the harder one, it is also the only one that gives them a chance of standing up for themselves, as the illusion was always a seductive lie. The antagonist is also an Executive with the body of a Ranger to approximate the two and remind you that they can be one and the same. As Hisui put’s it, “I’m sorry that your perfect world couldn’t exist”; as I’ve said before, there are tyrants on both sides; and as Steven Erikson once said, “The tyrant thrives when the first fucking fool salutes.”

Narrative arcs that deal with the lost youth and what-could-have-been scenarios tend to get me because I relate to that shit hard. I didn’t get a chance to live my adolescence the way I wanted because I hadn’t even come into my own identity as a woman, and that disconnect kept me from acting the way I wanted while also making me feel that the things I actually did were fake because I was simply going along with the preconceived notion that we are we and that they are they. Just like the students in this arc, I have had to accept that while there is solace to be found in basking in the idealized youth I could have had, I can’t refuse the material reality that that simply isn’t going to happen and any amount of time I spend longing for it is stopping me from actually getting shit done in the life I do have. The blending of themes and technicality of this arc is simply marvelous.

I am particularly fond of Hisui’s message that there are no requirements for heroism, you simply have to take that first step. Not because I believe in the idea of a hero we were taught about when we were kids, but because no matter what happens, nothing will ever change if you don’t take that first step to begin with.

I have briefly talked about how a lot of anime and manga focus their themes in an attitude the story is advocating for in my Sonny Boy analysis and it is actually kind of funny how many similar things I got from these two wildly different stories. If you don’t remember or haven’t watched it, the first episode of that show also takes place in a school that defies physics, has laws that can be enforced by the people living in it, ends with a character taking that first step and the rest of the story is, in a gross oversimplification of it, about everyone else trying to catch up to her.

Also, the fuck do you mean this arc is only 18 chapters long? Each of them is so dense I was under the impression it lasted for about 30.

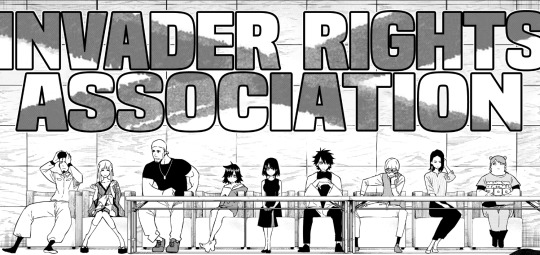

Everything I just talked about proceeds to permeate the next big arc, that of the Invaders Rights Association, or IRA for short. A long arc that simultaneously feels like a bunch of shounen bullshit and a natural development going forward. We spent the whole series with a wronged Footsoldier, having met Hibiki all the way in the beginning who thinks they can coexist, so it stands to reason that that could eventually take a front seat in one of the story’s arcs. This arc is going to complete the change in worldview D has been going through all along, because as it expectedly turns out, the IRA is a villainous association born out of a genuine desire that was then bastardized.

D’s World Domination plot isn’t exactly a world domination, he’s thinking about it more in the lines of freedom. World domination is simply the ideal that was instilled into him from the moment he was born. Prideful though he may be, this man spent the first section of the story having to learn that he can’t get shit done alone, then using other people to achieve those things, and now he is going to learn that there are people willing to help him even if they find out who he really is. We know for a fact he didn’t fight just for his own sake back in the school.

There has always been a meta element to Loser Ranger as it deals with the existence of heroes from super sentai, has a super sentai show in-universe and the Keepers are just celebrities. In the IRA arc that then becomes part of the core conflict, building to some revelations that evidently will be properly explored in the next big arc as it has been doing so far. It isn’t as if the meta aspects are mindblowingly awesome, but they serve as an interesting way to frame this section of the story that keeps it fresh. I am particularly fond of the “This has been foreshadowed” gag.

I find that all of the big arcs so far are memorable because of this combination of framing and setting: starting with a classic exam arc in an underground base where the protagonist has to survive to reach the surface of the human world, to a more intimate character exploration in a school environment and now arriving at a meta narrative in a big castle, filled with cameras, TV broadcasts, YouTube livestreams and a VHS tape or two. Every arc has a distinct look and feel to it while still being brought together by the same narrative conflicts.

Shaking up the narrative structure by taking advantage of the fact D had to work from the shadows and rely on subterfuge all this time, the IRA arc introduces a group that actually has enough power to expose the Keepers as the liars they are and go face to face against them following that. It seems to me that this author is very smart about when to bring things into focus. Usukubo, for instance, was introduced all the way in the beginning, but did pretty much nothing in the second arc while Hisui became a main character. That is then balanced by having their positions switched in the IRA arc as Usukubo’s character is fully unveiled and Hisui spends half the arc bidding her time. Having someone we know serve as a stand-in for the audience inside the IRA eases the friction of suddenly introducing so many new characters. There are plenty of secondary and tertiary characters from past arcs who are weaved into the story again, these not requiring that much page time to have a role to play as we already know them and a flashback here and there is all that is necessary to give us more context into their backgrounds. Pink Ranger’s in particular is the stand-out as it gives us a reason to care, has that one panel in particular of her body falling back in a splash of blood that hits when you turn the page and sets Hibiki in an unexpected path.

Since you have read it this far I am assuming you care about what I have to say, so allow me to go on a brief tangent to give you some writing advice: if you come up with a structure, don’t overuse it, and if you have to, then come up with ways to keep it fresh. There are a lot of flashback sequences in Loser Ranger, but they come in different kinds. Some are interrupted by D saying he doesn’t care, some are kept very short, some are broken up in more than one part and the bigger ones are reserved for moments where they provide much needed specific information and only when they directly relate to what is going on. The immediate outcome isn’t always the same either, these flashbacks don’t always happen right in the last moment of a fight nor are they all preceded by the central character of those scenes dying. In essence, there are reasons why structures used in a bunch of different stories work, but don’t just throw a sad backstory in at the precise moment a character is going to be defeated every single time. It will get boring fast.

Thematically, I don’t have that much to say about the IRA arc, and frankly I don’t think the arc was shooting for that. The most emotionally interesting the series has been to me so far was with the School Life arc and I would argue that is very much by design. That does not mean that the IRA arc is lacking, as it is the most action-filled and violent arc so far and rescues a lot of scenes from previous chapters, making it feel as if we have really come a long way.

Just like it has been the case for the past arcs, a lot is established around this arc that we are yet to see the ramifications of. There is for sure more to be said about the Suzukiri Clan, the Neo-Rangers weren’t created just for the sake of it, the horrifying inventions of the Yellow Battalion haven’t been fully explained yet and the new position the Red Keeper is in is the “storm” the narration said D had unleashed — which unfortunately is something I don’t like, the first big narrative gripe I have with the story so far is this, as I don’t buy it at all that the Ranger Association wouldn’t have checked for his body, but hey, a single big issue in 139 chapters is a great relation.

So as to not end on a low note, let me conclude. Negi Haruba wrote a harem manga about quintuplets, made a ton of money (conjecture), then decided it was about time to cook up a killer action series. I am not nearly as much of a manga reader as I am an anime watcher, so I can’t say much on how it relates to the overall state of shounen manga, but I would bet that Loser Ranger is going to feel like a breath of fresh air to most people, whether or not you like it as much as I did notwithstanding. The very beginning is kinda mid, I know, but if anything of what I said sounds interesting to you, then hang in there, give it a couple more chapters. The artwork is sleek, it’s super bingeable, it’s slowly getting more violent with each arc (I hope it gets way more), the plot can be a case study with how organic it is and I need to get a Hisui tattoo.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sonny Boy and The Lost Youth - an anime analysis by Amy Warrel

This analysis is enormous. You have been warned.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The world is confusing. No one knows how to properly navigate it. You’ll get a grasp on it eventually and there might be people to help you out, but one day you might also drift apart. That’s a very sad notion, but it also one that reminds us of one thing: what we lived has value, those memories of old are meaningful and our connections to other people will continue to shape us long after those relations are over. Sonny Boy is not subtle in its commentary about getting lost in the world and society. The characters are all transported to a world in which their school is the whole extent of said world. Everything beyond it is pitch black; you can reach for it, but you don’t know what you’ll be getting yourself into. Inside, teenagers try to make it into a functional society, but are obviously all lacking in resources and life experience to do so. Some people are more talented or stronger than others, and that is enough for social bubbles to emerge. I’m sure most of us can relate to the notion that we are getting left behind, that other people are finding their careers, finding what they are good at, have a decent idea of what their life will be like once they step out of school or even already have a future guaranteed, but we — or I — always feel like the outcast.

As someone who spent their whole teen days knowing the only path I could pursue in life was the path of art — which ultimately led me to turn to literature —, I can highly relate to coming of age stories and the anxiety of stepping into adulthood. I can barely manage adulthood even after having been an adult for supposedly four years and “getting ready” — you eventually learn that school is not as good of a leeway into working life as you were led to expect — for it for many more years, so I can see a lot of myself in these character’s emotions, struggles and decisions.

Nagara is the closest thing to a stand-in for the audience in this show, but has enough of a personality that he does not come out as simply self-insert material. Being an introvert does not mean you don’t have a personality, it just means yours doesn’t come out as much, especially in such a confusing age and place where opening yourself up to others is hard when you don’t know how they will react and harder still when you might not even understand why you feel the way you feel. Nagara’s character is used to talk about others' expectations in a very direct way in a couple of episodes, as well as the importance of social connections, while the “speaking up for yourself'' part is also shared mainly with Mizuho.

I am surprised to see Mizuho not being revealed as a transgender character later in the series, since she is reading Stop!! Hibari-kun! In her first appearance, a 1981 manga about a transgender girl going through school who also turns out to be the daughter of a yakuza, but as it turns out, I simply hadn’t realized that Hisashi Eguchi, the character designer for Sonny Boy, is the author and artist of Hibari-kun. Mizuho is by far the easiest character for me to relate to because of this, because of her relation to cats — I have more than twenty of them, it has gotten out of control, someone please help —, because I would have loved to look similar to her through my teenage days — having come out as a transgender girl myself after over a decade of suffering with gender dysphoria — and because she is just very entertaining to watch on screen. I also love her voice; Yuuki Aoi sounds like she is very close to the microphone when speaking just like how all the other characters are doing, which couples with the anime’s more simplistic art style dedicated to giving each character more distinct facial features instead of just telling everyone apart from their hair color, these being techniques that invite a lot more intimacy from the audience and drags them closer to the characters and, by extension, the themes. Having said that, something about Yuuki Aoi’s voice just entices me. I believe she communicates Mizuho’s melancholic and occasionally smug personality with impressive effectiveness.

Of course, the character’s don’t stand in school for long. The first episode’s arc is a very self-contained one about rules, authority and the dangers of it, in which losing said authority leads a kid to hit another one with a baseball bat in the head. Power is a dangerous thing, it messes with our morals, it makes us scared of risking it and can be used both for good and for evil, even by the same person. Give someone too much power and it’s a matter of time and circumstance until you get yourself a war.

I believe the first episode was presented this way with airing conditions in mind. Sonny Boy overall lands itself incredibly well on the style of episodic storytelling with a narrative and thematic throughline to glue it all together, honestly one of the best I have seen yet in that department. Making a first episode that presents the audience with a simple premise in a restricted environment is a great way to ease the viewer into the story.

That structure gets quickly expanded upon as Nozomi takes a leap of faith towards the unknown world, and all the students now find themselves on a new island and with the information that there are many “This Worlds”. All weird places that no one understands exactly, all connected in some fashion that they are still to uncover, and all of it can be conquered by the kids’ specific powers — talents, as they are thematically shown to be — and give them different rewards that they then have to learn how to use. It is not hard to see what that means: its plot significance is one of adding flavor and mystery to the world to better mark the student’s progress as they peel off the mechanics of these worlds little by little, but its thematic significance is one of putting your talents and skills to use and being rewarded for your work.

However, that is just the first episode and there are eleven more to go. Yes, I’ll be going through this commenting “briefly” about what stood out to me in every episode, which I never do, but this anime is an exception and it deserves it. Full on spoilers from now on, you have been warned.

Each episode deals with a couple of different themes but there are always one or two clearly main ones. The series is more interested in discussing these themes in its surreal world than properly grounding every facet of the worldbuilding, which is totally unnecessary once you are shining so many lights on the relevance of the themes above everything else. Yes, the anime has a lot of small little mechanics the characters need to understand about each world, but these mechanisms are generally intrinsically tied to the theme of each world, so don’t expect the type of worldbuilding we are used to seeing. It is not important that we know everything about the island, how far apart things are and where everything is being built, it is more important that we understand how the characters react to their environment and how they communicate — or attempt to — through said world.

Episode two, for instance, leads to the canonical creation of cryptocurrency by everyone’s dearest Rajdhani, but really the important aspect of it is commenting on how a society gets formed à la Lord of the Flies. There are other elements to this episode, such as Mizuho having to speak for herself as I commented earlier, the fact that value is attached to things by our own decisions and how this value can be altered through the means in which these things are obtained, but episode two is still primarily about introducing Mizuho’s character and her struggles with being a kid who wants to be more than just a kid.

I particularly love the fact that at no point does the plot judge Mizuho for having a crush on her teacher. That sort of stuff happens. She can’t be blamed for developing feelings for a figure she sees as a guiding light in a twisted world. We are very clearly led to understand that she decided to wear a ring not because she was in an actual relationship with him, but because she saw that as a stating of her own maturity. Other characters later bring attention more than once to Mizuho’s emotional dependency, it used to be put at least partially on her teacher, but because of the blackmailing she suffered and the circumstances of being stranded, that then turned exclusively to her cats. And I ask again: can she be blamed for it? No, she can’t, and I appreciate the writing for being self-aware enough to understand that and respect her character instead of turning this into what could have been a generic villainization of teen sexuality. Please note that I am only talking about her emotional dependency and her having a crush on her teacher, I am not saying that actually being involved in a romantical and or sexual relationship with a teacher is ethical, especially considering that Mizuho is sixteen years old.

One of the great things that fantastical elements in a story allows is the literalization of metaphors. Episode three does this by using a rule that makes recluse people totally isolated within a pocket dimension of endless black curtains, all connected to each other through gaps in these curtains, meaning there is a way for them to communicate with each other. In this dimension they are all doing what they want to be doing: one guy is livestreaming Pacman, there is one buff dude that only wants to work out and a girl that is sewing multiple stuffed toys… you get the idea.

Society isolates people and that should be a given in any system created by humans. There is simply too much idiosyncrasies in our relations and personalities and it would be goddam boring if everyone was the same. Of course it can get to a point where it is detrimental to the isolated person, but that begins as a way to cope with our inability to communicate with people we feel we should be able to communicate with — because everyone else does, apparently — and our interests and passions not being well-seen or simply really hard to turn into a living. Who wouldn’t like to live in a world in which subsistence is a given and we can do whatever we want and repeat our hobbies for as long as we can stand them because we enjoy it?

Some aspects of Sonny Boy’s multiple worlds can maybe be related to the concept of a noosphere: a state of evolution defined by our consciousness, mental activities and interactions with other people, it is both above and ahead of the geosphere and the biosphere and envisions a world in which Earth is essentially a super-organism and there is a layer of consciousness and information enveloping it all. I am not claiming to be an expert on the matter and maybe the creators weren’t even trying to pursue this idea in particular — seen in the fact that they like mentioning Robinson Crusoe, so you could expect then to mention the noosphere —, but the many This Worlds in the story are described as playing with consciousness and the mind. Also, in a noosphere humans would be united enough to be able to deal with global problems and Earth can self-regulate itself, which these Worlds do by their own set of rules. I’m sorry if anyone has studied this and if I said something wrong about it.

Going back to episode three, it keeps pulling the thread of commenting about isolation with things such as no one noticing these people’s disappearance except those in direct interaction with then and these people might not even go looking for the missing ones, which is certainly how most people I know describe the feeling of being depressed and the notion that no one understands them. It also has some very direct commentary about our capitalist society through reflecting on the fact that the blue flames of the island take everything away from you that you haven’t paid for and with Mizuho complaining about people wanting to be friends with her power — what she can do —, instead of with herself — who she is. It is not a particularly complex exploration of the individual's relation with capitalism and their worth in it, but at least it is something.

This episode also turns Nagara and Mizuho into a duo, which is something we are going to see a lot more of through the remaining episodes. You get the drill: they fail to communicate, fight, then manage to properly communicate — which goes hand in hand with the episode’s theme of isolation caused by an inability to communicate — and solve the issue together, yadda yadda, we have seen that before. It is executed competently and makes sense within the story, but Sonny Boy is not a non-stop flow of impressive big ideas and unexpected twists and turns leading to their incredible solution, it is that just most of the time.

Episode four then comments more directly about how talent can distance people. That is a recurring theme through the whole show, but in this episode we see a story about an ape who wanted to play baseball, but could not because of the physical liability of only having one arm, but that did not stop him from loving the sport and ending up as an arbiter, however he was seen as the common person, relegated to a background position while other, more talented and successful people shine in the spotlights, leading him to be killed by an enraged crowd for standing up to his sense of justice. Before that all the apes were indistinguishable, having to stand out on the basis of their prowess, while some people are like the blue ape, clearly different and talented enough to steal everyone’s attention and moments to shine, which leads him to forget his origin as the target of prejudice and causing harm to another victim when the goal of being perfect becomes more important than enjoying the moment and the success he already has. Ace then goes on to say that the arbiter’s death was fair because there are common people who drown other’s talents — referring to his talent and Nagara causing him to lose an important game back when they played baseball —, but of course he is totally wrong in this. Loving something and having a competitive mindset about it can blind people sometimes and Ace does not realize this, while Nozomi, being by far the most conscious of her surroundings and constantly having insights about the other kids' psychology everytime the “camera” zooms in on her eyes, is the first one to call attention to the fact that the impressive ape in the whole story is the arbiter, for standing up for himself against everyone knowing that he would be seen as the enemy.

I know most of what I just said is spelled out in the episode, but since I am committed to reviewing the whole show I have to mention these details, because Sonny Boy constantly builds upon the themes of the last episode in the next one instead of just going for unrelated yet interesting themes or repeating the same ones like I feel other shows I don’t resonate with very strongly often do.

Nagara is also shown to not have enough control of his own power to determine where he wants to go. We find out that he can only travel to other This Worlds and not back to their original one. I believe Nagara to be the carrier of this power because he is just enough of a blank-slate to fit virtually anywhere while also not feeling like he belongs in any of them, having no clear goal in life and thus not wanting to go to any place in particular, drifting through whatever comes his way. Sure, he can bring other people with him, but it’s not as if he is going to any one place.

We end this episode with the introduction of Aki-sensei, someone the kids recognize as being one of their teachers back in the real world. Aki-sensei immediately tells them that the fun and games have ended and that there is no way to go back to their original world. While a lot of what she says is put to the test later on, Aki turns out to be a figure of authority manipulating these kids and creating even more distinction between the groups, managing to bring every single person that would be willing to trust a figure who is supposed to know what she is doing while the other groups are made of the students that want to find that out for themselves. Her primary target for manipulation is Asakaze and everything that was needed for him to trust her was hearing that he was special, that he deserves special attention and that he has a special future. Again, this is dealing with the psychology of people receiving power and status, in this case especially by someone who he sees as having a better grasp on reality and thus making her words all the more meaningful.

As soon as the sides are clearly divided conflicts start emerging faster and it doesn’t take long until we see three separate groups being formed. That is expected to happen whenever there is a society, especially when it starts to grow and people gravitate towards others similar to them and in whom they believe in. Aki-sensei is not right in her manipulations by any stretch, but her presence merely accelerates an ongoing process. The meaning of Aki-sensei in the story changes a bit once when we find out she is actually not Aki-sensei but another student playing as her, changing what was a figure of authority manipulating kids in vulnerable positions to being one of those kids, just as lost or even more lost than the others, pretending to be a figure of authority who understand the world better than they do and presenting it as necessity of maintaining the status quo while framing the other kids as potentially dangerous precisely because they are trying to lay change upon the world. Knowing all of this, it is no surprise what their actions later escalate into.

One of the most interesting ideas the anime introduces is in episode six, where they find a world that is a giant cinema filled to the brim with records from Nagara’s perspective. It fits his character considering Nagara is used to spending his days as simply an observer that takes no action and the way the mechanics are played with are interesting. What if we edit the records? What if we play it backwards? It doesn’t really matter how much this amounts to, the questions are interesting enough by themselves. Not all changes made to the films actually happen, even if Nagara is present, this probably means that not everything done to the films will actually change his perception of reality. If it is something that he can’t imagine happening or doesn’t have enough suspension of disbelief to accept, then it likely doesn’t affect the real world.

Yamabiko is a particularly interesting addition to the cast: a once student turned dog who has lived for five thousand years and finally gives us some answers, claiming that the reason the drifting happens is because their principal is God, explaining that only the school and students can get adrift and that it only happens with people from the same school they went to, no matter the time in which that happened. Though there is not much that can be said about Yamabiko and the themes revolving around his character before the episode dedicated to expanding on his background, he is still a fun and mysterious character that shares good synergy with Mizuho. He does, however, say that the kids from the current drifting still have time to go back. Our experiences through a structure like school and our teenage days shape us and once we step outside of it, we aren’t the same as when we first stepped in. Since the perception of reality is an important concept in this episode, then this means that if we changed, then the world itself changed, because our reality is simply how we see it. Nozomi, for instance, keeps talking about her compass and the light she believes will guide them home, but we don’t have to actually see that light to believe her. Yamabiko on the other hand simply can’t go back, because he has lost too much and been around for too long, to the point where he doesn’t even fit the actual real world he was used to.

My favorite part of episode six is when Nozomi is talking about how she doesn’t want to walk down the safe paths people have told her about just to think “Ah, good going.” That’s not what life is for her. Nozomi is a very brave and insightful person and she wants to do what she wants to do, she is a free spirit that can appreciate the present more than all the other kids. She can get anxious and scared, but that is precisely why she does it. Nozomi wants to feel, wants to live and wants to take risks. Honestly I would like to be a little bit more like her, but I’m simply not brave enough.

Hoshi’s White Knight Syndrome is also brought to the forefront in this episode. He knew the school was going to go adrift and that is why he went to school that day, because he wanted to help these people, but this is not presented as simply altruism. Hoshi had always been drawn as creepy and scheming if not necessarily evil, but as we also find out, this desire of him to help others does not exist because he actually wants to help them, but because he has a god complex and wants to be a savior. Meaning, he’s going about it the wrong way.

Episode seven is my least favorite of the bunch simply because it was the first to come out as too heavy-handed to me. You see, a lot in fiction boils down to promises and payoffs. The ending of episode six and the entirety of episode seven gave me the impression that the series was going into another direction, having the newly discovered plot about castaways that have been adrift for longer wanting to punish Nagara for ruining their lives take a more prominent place in the story. Don’t take me wrong, I’d much rather this current story that the anime has, but it did gave me the feeling that that was the promise being made for the long run, that this was the direction it was taking and by the ending of episode seven I was expecting it to turn into something similar to “us against the government”, so finding out that was not the case was both a relief and a confusing moment. Even after watching the episode again to try and judge it in a different light already knowing how the story ends, my view on this hasn’t changed.

This doesn’t mean I don’t appreciate anything that episode seven does, of course. Sonny Boy frequently calls attention to Nagara’s personality and the need to speak up for himself, but it is never offensive about it. Koumaru reaches the conclusion that Nagara can’t be blamed for drifting them and Yamabiko notes that God gave him that power with the intention of it being used for the drifting, which also means he can’t be blamed for being who he is since that power is so rooted in his personality. He can get more out of life by forming connections with people, but we don’t need to scorn him for that until he learns his lesson.

The world turned upside down is still a neat idea even if I don’t think it is used to as satisfying a conclusion as most of the other episodes do. It explores the idea of a stagnant society that makes its workers believe that they are changing it, no matter whether they believe it or even know what exactly they are supposedly doing, giving them a blind hope to help cope with their trapped situation. Since Sonny Boy constantly pulls threads from previous episodes it is pretty easy to relate this to Nozomi’s phrase of not wanting to walk down the safe path in life.

All it takes for Nagara to flip the world upside down is to take a step away from the safe spot. I get the message, but I feel like it is slightly too simplistic. Sometimes this anime does not deliver in the themes department as well as I would have liked, but thankfully the strength of the main characters is enough for me to see that as just a minor nuisance.

Episode eight, on the other hand, is among the amazing ones and it does a lot more for the characters and tone than any episode honestly even needs to in order to be satisfying. We jump from present to past as Yamabiko tells his sad story. In the present they are traveling along with Nagara, Mizuho and her cats, but the framing always keeps us close to the characters instead of zooming out to show the scenery, which is great to shorten the distance between audience and characters, hyperfocusing this episode in the people we are seeing and leaving the exploration of the world to the side for at least one episode. The muddier color design and music also helps a lot in keeping this episode tone-perfect all the way through.

The reason why I find this episode to be genius is because of how Yamabiko’s story recontextualizes the characters of Nagara and Mizuho. Yamabiko was a shut-in who simply crawled his way through life just like Nagara, but to a much more intense degree that leads him to completely isolate himself, instead of trying but not managing to speak up like how we see Nagara often doing, leading to a point where Yamabiko reacts violently to try and scare people away. He also brings attention to Mizuho’s emotional dependency by increasing that to the point where he turns into a dog to follow the lead of someone he trusts more than even himself, and it is these two things combined that eventually leads to the ruin of the people around him and himself.

Episode eight is primarily about ignoring your problems until it is too late. Yamabiko’s power gives him the ability of manifesting his mental state, this being the reason why he turned into a dog, but also being the reason why the epidemy hits Kodama and her friends. I don’t think it would be right to call these kids the new family Yamabiko has found, because his interactions happen almost exclusively with Kodama, being the pure guiding light — probably even motherly figure, since her power is called “M”, I know that might mean "Manipulate" or something, but we also know that Nagara has an issue with his mother who is herself a shut-in that doesn’t leave the house — so that he needs to go through life without thinking, leaving all his worries and objectives for someone else to decide. Thus, he is walking the “safe path” mentioned before.

The anime is clearly self-conscious about all of this, since not only do the personalities of these three characters relate in such a direct way, but also because we see Nagara saying he relates to it, while Mizuho starts the episode more playful and smuggy like we know her to be, but then gets quieter with every interlude to Yamabiko’s story. I have praised the anime for respecting its characters until now, but it is an even greater thing that it is willing to bring attention to how dangerous their paths can be. I agree with the message of following your own path and being yourself, but I am also not naive enough to pretend that all is well when it isn’t and, even taking in the fact that we all want to live our successful lives doing what we love, the world is not fair or simple enough to simply allow that to happen without any sort of friction. There are aspects of us that have to be fought against just like there are aspects of the world around us that we should fight against.

Since I mentioned music and tone, I want to take a short while to talk about the production of Sonny Boy. The reason why this anime feels like so much of a breath of fresh air is because it is almost 100% pure 2D animation, with as little post-processing and CGI as is possible. I’m not saying there isn’t great animation out there, but it honestly boggles my mind when I see so many people sharing sakuga moments from anime like Fate or Demon Slayer where half the screen is drowning beneath post-processing, artificial light from above to make every frame feel epic and world-defining and tons of CGI even if it is great CGI. I don’t want to sound like an elitist, I can enjoy those things for what they are, I’m not saying that CGI and post-processing have no place in the industry nor am I saying that the shows mentioned here are poorly produced, but every now and then I want to watch something different instead of having the feeling that every anime that ever comes out is trying to do the same thing to various different levels of success. I am eternally grateful to the team behind Sonny Boy for deciding to go with this style of production because it fits the tone of the series so much better then if it was trying to be flashy in its presentation.

Something else that I really like about the production is how the music is kept quiet. There are exceptions — especially in the last few episodes — for example in the more montage-like scenes, but generally the tracks are kept distant, while the character’s voices are kept closer, rarely having distractful lyrics, leaving the presentation and dialogue to pull most of the weight. What this also does is it keeps it from ever getting repetitive. Sometimes anime — especially more action-centered anime — will play the same tracks over and over again to the point where they run the risk of not being iconic and memorable, but also redundant and annoying. I’m not going to pretend I’m an expert in the matter, but Shouji Hata, the sound director for Sonny Boy, worked on a ton of really popular stuff, some that I even distinctly remember liking the soundtrack — such as Vinland Saga and Log Horizon —, so, if I can interpret the production this way, I also believe that a professional who has probably been working in the industry for longer than I have lived can do all of this intentionally.

Now proceeding to episode nine, this is one I’m not so hot on either. The highlights are everything related to the cats, of course. I did not expect them to start turning into actual characters — even if very simple ones — and it adds an extra layer of charm and comedy to their interactions.

I definitely enjoyed it more the second time through, knowing where the series ends and paying more attention to Asakaze’s and Nozomi’s interactions, but the overall plot and complexity of the themes just doesn’t hold up in my mind.

Aki-not-sensei wants the power of the twins, but only one of them. Since they are both the same person, this means that she only needs a part of the person being manipulated, everything else can just be thrown away and does not add up to your value — this is interesting to think about if you remember that Aki keeps pretending like she is saving the world and reducing the values of individuals she doesn’t need and overestimating others to do her deeds.

The twins are fighting over the fact that one of them has a single strand of hair more than the other. Clearly the point of this is that people overestimate the worth of some things only to pretend like they are better than others — and if these are the same people, then it can be seen as him not being able to deal with the fact he is not perfect by externalizing it into an enemy. Their power to reverse everything makes them forget the whole fight and they end up fighting eternally because you can’t simply go back, your experiences change you and nothing is accomplished by trying to go back to square one as if nothing had happened, he has to accept his own flaws and not try to reset everything to zero, but do things differently with the knowledge and experiences he gained on the way. Aki of course gets to him before he can realize any of this and the result is that by killing a part of himself, he kills the whole.

Maybe I would enjoy this episode more if it had been done with a character we already knew. Sonny Boy focuses its characterization in the four main faces of the show while leaving other characters very superficial and using them almost exclusively to explore themes. While I don’t think you can criticize the fact that the secondary characters aren’t that fleshed out since this anime is trying to do twenty times more things than most anime are, I still felt like bringing a wholly new character for this episode ultimately hurt the effectiveness of the message more than it did any other episode.

There are two characters in this show who try to mimic God: Asakaze and Hoshi. In episode 10, we see Asakaze being tricked yet again by Aki, who takes him to see the principal — God — who asks him to kill War, the character we met in Yamabiko’s flashback. Kossetsu — who we find out has the ability to read other people’s thoughts — convinces Nozomi to come along. Kossetsu loves Asakaze, but he loves Nozomi, so she wants Nozomi to help change him to a state where he might end up at her feet. Obviously, only tragedy could come from this.

Asakaze was so obsessed with the concept of a great mission reserved to him that he allowed himself to be manipulated by Aki and ended up losing sight of everything that doesn’t relate to pursuing Nozomi. He confessed to her, but got rejected because she couldn’t respect him. Asakaze then says that he was probably obsessed over her because he felt like he could never be as strong as her. At this point he realizes he should let her go, and, after conquering the world “War”, he actually manages to create death when Nozomi falls off the cliff and into the nothingness at the bottom of war, not managing to save her because as it turns out, his power is spontaneously activated. He did not want Nozomi anymore, therefore he couldn't use his powers on her. Asakaze’s power was born out of his need to keep everything and everyone at his reach. God definitely knew this and tricked him along with Aki.

The War we saw in Yamabiko’s past was still walking around, but the one we meet here is completely empty, falling to the bottom of a deep gorge yet never actually reaching it even though there is one; stagnant. Only Asakaze can bring him to the ground and his reward for that is a weapon.

War is a manifestation, a world himself, and conquering him grants you with the power to kill. There is a chance he was even tricked by God as well, since he was killing people before Asakaze, but God of course never bothered with telling him that death is a phenomenon that can happen there under specific circumstances. Since we find out that the drift was caused by the combination of Nagara, the cats and Mizuho all using their power unwillingly; Nagara creating worlds, the cats copying the kids and Mizuho putting them all in stasis because she doesn’t want to see anyone die, then conquering the world “War” gave them a power that could go against Mizuho’s power.

I like the way the world “War” is presented, as a hard to climb mountainous area that is then abruptly interrupted at the top by “a gorge that goes down forever, but the bottom is crimson.” The fall is the only thing you can expect after warring and whatever lies at the bottom of it is not going to be good. It stretches forever and is a wound delivered in the world itself. It might take time, but it will take its toll.

There might be more to be said about the imagery of War in this episode, but honestly this is all I’ve got.

Episodes eleven and twelve are a two parter to end this amazing ride. As you can expect to happen after Nozomi’s tragic end, the next episode is dedicated to mourning her loss and dealing with themes of grief and death. It is both heartbreaking and heartwarming. I had a slightly hard time breathing through the entire montage opening of Mizuho and Nagara honoring their friend and seeing how far their friendship has come. It hurt seeing both of them cry, it hurt seeing two people seeing their friends crying at their side at different moments of the episode without knowing what to do about it. And, above all, it hurt seeing Mizuho say goodbye to her cats.

Years of trauma and emotional suppression rendered me completely incapable of crying out of emotion, so every story that gets me even close to it surprises me. Last time I “cried” was recently and there was but a single tear, I can’t even remember how many years it was since the last time that I actually cried my heart out, with sobbing and sniffing and stuff. Fiction is what helps me deal with this, and I’m goddamn grateful to Sonny Boy for being on the list of stories that got me close to crying.

As my favorite author — Steven Erikson — once said, “Grief is not something you overcome, but something you get used to carrying the weight of.” I might be paraphrasing that, but you get the idea. We might not see Mizuho and Nagara for long enough after Nozomi’s death to see the full repercussions of this, but we know they are going to carry the weight of everything they lived in these two years adrift for the rest of their lives.

After ten episodes commenting about how things are hard to change, we finally begin seeing some clearer changes in these last few episodes. It began with Nozomi’s death, but we also see how Yamabiko has now completely turned into a dog and doesn’t speak anymore. We see how Rajdhani’s gaze has changed and he reflects on the fact he is growing more apathetic with time. He tells us the story of a man who could not accept reality and would create images of his home and his girlfriend that were not accurate at all, trapping himself in the made-up ideal world of his mind, which relates to the relationship between Asakaze and Nozomi.

Rajdhani also tells us the story of a student obsessed with the idea of creating “death”. Perhaps this can also be interpreted as a character trying to mimic God, since he is trying to create something that was previously impossible . First time through I was sure this was Hoshi, but it is very clearly War, my bad on that. We get the information that he conducted experiments in death and suicide and can assume that he got his badges from that. He created death by rendering his identity completely void, having no desires, no reactions, no emotions and no opinions. He created death by going against everything that defines a person, becoming a mere shape.

As Rajdhani puts it, “Life is an endless exercise in vain effort. But it’s precisely because it’s meaningless that I think the brilliance of this moment in life is so precious. Because that one moment belongs to that person alone.” Ultimately, the message of Sonny Boy is wholly positive. It is realistic enough to recognize the worst parts of life and it does not pretend everything will go right simply because we want it to, but it also finds it important to remind us that, once again, everything we have lived up until that moment is what has shaped us and thus has value. We don’t have to change the world, we just have to find a place to belong in it. Nozomi’s will still lives on, her compass still points to the light, unwavering in its determination, and her mark in the world and in her friends will long outlive herself.

And in episode twelve, we get the confirmation that Nozomi had always been right. The light had been there all along, she was the only one who could see it because she was the only one who's outlook on life matched what the story is trying to convey. It takes an astronomical effort to even get there because that is how much time they lost and enduring how much the world is going to strike you down is no easy thing. They only manage to do so with the combined efforts of Nagara, Mizuho, her cats, Rajdhani and Asakaze — handing them another compass, presumably the original one. But, even after getting to the light, there is this one beautiful scene where they are only able to capture the light by the efforts of Mizuho’s and Nagara’s hands. I always found it interesting that “light” was used for the analogy of the path in life. I mean, try to grasp a light like how Nozomi was doing. She could only reach it, but could never quite hold it, at least not alone. It is light, after all, and it will slip right between your fingers.

The last episode gave me a twist in the stomach when it felt like Nagara and Mizuho weren’t going to talk, but thankfully it was just them having a hard time talking about it. We get to see glimpses of what their life is going to be from now on: Nagara getting a shitty job — yo that’s relatable, kind of —, Mizuho’s grandmother having passed away, Nozomi and Asakaze ending up in a relationship in a world in which they can respect each other. Well, now that I think about it, I don’t think anything that they do in this last episode proves that they are dating, but they are clearly in better terms than their copies that went adrift. If the copies are still adrift and those are the parts of them as people that conflicted with each other, then this original version is the one where things went better for them.

In the past, Nagara ignored the dying bird. Now he cares about the birds that have lost their mother — you could say they are stranded just like the kids were —, but Nozomi had already thought about that and took the only surviving one with her, deciding to taking care of it until it is able to fly by itself, instead of trapping the bird and not allowing it go where it needs to go in life. This interaction shows us that Nozomi is still one step ahead, still striding forward in life and doing what she believes is right. She might not be exactly the same Nozomi we know, but her essence is still the same. Yet again, I wish I could be a little bit more like her.

I am also pleased to see Nagara and Mizuho not turning into a couple. This would have come off as weird and even thematically inconsistent I would say. Since Nagara and Nozomi never ended as a couple, then him ending up with Mizuho would send the message that she was the second option, or maybe that he was looking for the wrong person in Nozomi. The point is, either of these options would have diminished the characters. If they ended up as a couple, then a short arc where they learn to respect each other and brings attention to the morality of Nagara being suddenly romantically attracted to her after finding out Nozomi is with Asakaze would have been completely necessary not to break their dynamic. Either way, I’m much more satisfied with their current friendship than I would have been if any of these characters ended up feeling like a trophy.

I don’t think there’s much more to be said, at least not now. Sonny Boy is about and trying to say a lot of stuff, much more than most anime I watch are, and it accomplishes that in a shorter runtime than most do as well. I barely mind the fact that secondary characters are abandoned or that not every episode is tone-perfect. I didn’t expect it to be and neither does it have to. While I can obviously appreciate several different kinds of stories, my tastes are always changing and I am slowly becoming aware of some elements shared between most if not all of the stories that are connecting with me on a personal level in the past few years. While I would not dare to reduce this anime to a single theme after having said all of this, I just wanted to share one more idea: this story is about the loss of innocence, but it does not end there with a negative outlook on life, it takes the extra step of being about hope for the future and acceptance of our past; acceptance, not surrender.

I’m pretty sure I have told someone that I wish I had watched this anime when I was eighteen or something, thinking that it would have been fundamental in forming my outlook on life — pretty sure it would have lead me to take on the nickname of Sonny Girl as well once I accepted my dysphoria, wait… I actually like how that sounds… — but I take that back. Stupid-ass eighteen years-old me would not have been able to appreciate it the way my current jaded one can. And that is fine, at least that is what Nozomi would try to teach me.

I ended up having a lot more to say than expected while also feeling like there was a lot more to be explored.

Of course, I can't score this anything else besides a 10/10.

Oh, and sorry for the heavy usage of em-dashes — I love these things.

#anime#art#writing#anime review#analysis#media analysis#media literacy#media criticism#madhouse#sonny boy#amy warrel

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trod and Pull, by Amy Warrel

On a foamy shore at night I walked Intent on taking my life The same tide that seduced pushed Even as it settled to beckon me rush

Lightning tore the sky asunder In each shard a star calling Worlds blinking their bidding For my grasp albeit outlying

Fleeting my embrace they hustle With lovers grace To meet callous end desperate to belong I yield chase

My would-be lovers glance back with eyes of pits To break my tumbling in slopes of their molding Until I reach the reefs that are their teeth And sink into the abyss of their everbeing

Bubbles heave upward to reach the flickering I hail life out of my lungs for their treachery My would-be lovers gaze and now I grasp That nature is not beyond mocking

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apotheosis, by Amy Warrel

I sat there at the end of the world A bonfire between me and God Its last gift to its remaining kin One of light and heat Continents shrieked around us Rising with dying voices Sinking without sound Tearing itself apart Spitting dead from the cracks Water made a living beast Insatiable in its hunger But God did not avert its eyes From tending to the fire Its visage obscured by Gaia’s gloom And the flickering flames "Voice your doubts" God said Yet did not let me answer Lost in its own mumbling "Fire as a gift turned it into a curse Doomed to ruin by the maker’s Flawed design" I opened my mouth and God’s hand snapped up Lo! It was a woman’s hand That bled unceasing To quench the fire

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gods of Clay, by Amy Warrel

Gods of clay darted across the yard They ran and stomped each other to flee the rain And carried the bodies of the first to fall Over their heads to block the assault

Yet when the sky was clear and the land dry None ever showed themselves The gods of clay hid when there was no danger And the reason for that was clear as dew

What value proving their worth When there was no one to admire? What value answering every prayer When only the direst was enough?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Road Stretches On, by Amy Warrel

The road stretched ahead of them Its misshapen spine inviting Surrender even from the god Who led the travelers

Shouting their guidance It stumbled forward A figure in the distance Demanding followers

The train writhed in its wake Retracing the god's steps Even its tumbles Knowing it safe

Reaching farther than their seers saw they Approached the pioneer intent on asking For the fate of those lost along the way When the god turned with blind eyes

0 notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

27 notes

·

View notes