Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

// Week 10: Social Media Governance //

Navigating the Intersection: Online Harassment, Social Media Governance, and Digital Citizenship

Hey, Tumblr fam! Today, let's dive into a crucial topic that impacts all of us who roam the digital realm: online harassment. 🌐💻 From rude comments to outright threats, online harassment comes in various forms and affects a staggering number of internet users worldwide. But here's the kicker: it's not just a fringe issue anymore. Nope, a recent survey found that a whopping 41% of Americans have personally experienced some form of online harassment. Yikes, right? So, buckle up as we explore the ins and outs of this pervasive problem and its implications for social media governance.

An Examination of Online Harassment and Its Consequences for the Regulation of Social Media

Harassment of any kind, whether verbal or physical, occurs frequently on the internet and affects a large percentage of the population. Consciously targeting specific people or groups with nasty, threatening, or insulting content is a common component (Wolak, Mitchell & Finkelhor, 2007). Abusive behaviour on the internet has traditionally been associated with extreme individuals—"narcissists, psychopaths, and sadists" (Buckels, Trapnell & Paulhus, 2014)—who are either unique or inhabit unusual areas of the web. But now, according to a September study by the Pew Research Centre (PRC) of adults in the US, 41% of those people have been victims of online abuse at least once (Vogels, 2021).

According to Duggan (2017), there are five main forms of harassment: sexual harassment, persistent harassment, physical threats, embarrassing others on purpose, and harsh name-calling. In a similar vein, Lenhart et al. (2016) classify harassment as a whole, including specific behaviours like physical threats and insults. By extension, "cyberbullying" is often used to describe forms of harassment that mostly target young people (Kowalski et al. 2014).

Gender bias is a common feature of cyberbullying. Gender-based harassment disproportionately affects women, non-binary individuals, and other gender minorities. Such harassment manifests in diverse ways, including abusive digital dating practices, non-consensual image sharing, and intimate partner violence (Bailey 2021; Rocha-Silva, Nogueira & Rodrigues 2021). Due to its prevalence in private contacts and the normalisation of gender-based violence, gendered harassment is frequently a reflection of larger societal imbalances and can be difficult to eradicate (World Health Organisation 2021). Furthermore, power imbalances and perseverance might be traits of cyberbullying (Kazerooni et al. 2018). Online harassment takes many forms, including but not limited to flaming, trolling, impersonation, and public shaming (Blackwell et al. 2018). As a group, these actions are aggressive, harmful, and intentionally hurtful; as a result, victims experience mental, emotional, and even bodily suffering (Langos 2014).

Effective measures for social media governance can only be developed by first gaining a thorough understanding of the perceived damages linked to various forms of online harassment. The negative effects of cyberbullying on victims' mental and physical health can be devastating, and in some cases, permanent (Harms 2015). Although the effects of harassment could differ depending on the specific form it takes, the nature of the harassment itself can also have an impact. Persistent harassment can have devastating effects; many victims, particularly women, have spoken out about the constant barrage of unwanted attention they've received while using the internet (Massanari 2017). Harassment, whether individual or perpetrated in groups, can have a multiplicative effect on victims' perceptions of harm (Marwick 2021).

Also, how people experience and perceive the harm caused by cyberbullying depends on their intersecting identities. Disabled people, Black people, and LGBTQ+ persons are disproportionately likely to experience severe and persistent harassment, according to studies (Grey 2011; Fitzgerald et al. 2019). The adverse effects endured by these communities are compounded by misogynoir, online racism, and discrimination, which manifest in the form of violence, stigma, and other detrimental consequences (Lirri 2015; Pskowski 2017).

Given these findings, combating cyberbullying calls for concerted efforts across technology, law, and society. The safety of users, especially those whose identities make them easy targets for harassment, should be the top priority of social media policymakers. Responsible social media administration's essential components include effective moderation regulations, robust reporting procedures, and proactive steps to counteract abuse. Another important step in reducing the frequency and severity of cyberbullying is encouraging positive online behaviours such as empathy, respect, and inclusivity.

Due to the multifaceted character of cyberbullying, social media regulation must extend beyond the realm of content management. Online safety can be improved if lawmakers and social media companies take the time to learn about the complex interplay between digital citizenship and the nuances of cyberbullying. Next, we'll discuss how online harassment affects social media governance and look at some possible solutions to this widespread problem.

Social Media Governance: Why It Matters

An essential part of creating a positive online environment is content moderation, which is how platforms handle infractions of community guidelines and other rules. To sort through the massive amount of user-generated content, content moderation uses a mix of human involvement and algorithmic detection, as pointed out by Gillespie (2018) and Roberts (2019). Although considerable effort has been put into enhancing policies, reporting mechanisms, and moderation approaches (Schoenebeck, Lampe & Triệu 2023), the majority of online platforms continue to struggle to effectively mitigate harassing conduct (Rainie, Anderson & Albright 2017). In addition, according to Vogels (2021), the problem seems to be worsening, since 79% of people who took part in the PRC survey think that social media businesses are only doing a fair or bad job of dealing with cyberbullying and harassment.

Among the many complex issues with content moderation, contextual subtleties must be carefully considered. According to Douek (2020), different cultural and linguistic contexts may have different definitions of harassment. Furthermore, human moderators must review massive amounts of content quickly, which raises ethical questions regarding the safety of these employees who may be exposed to disturbing content (Roberts 2019). Furthermore, concerns about censorship and responsibility arise from the authority that social media platforms have in deciding what kinds of content are acceptable to share (Kaye 2019).

On top of that, there is a wide variety and ever-changing character of online harassment. Vulnerable individuals or groups can be targeted through a variety of tactics, such as hate speech and doxxing (Grey 2020; Marwick 2021). The moderating process is made more difficult when such harassment occurs both publicly in news feeds and privately in direct messages.

Current solutions to online harassment, such as removing content and banning users, are being evaluated for their effectiveness. Despite their effectiveness in responding immediately to flagrant infractions, these methods may fail to tackle systemic problems with conduct or open doors to fairness and responsibility (Goldman 2021). As a result, victims are frequently left out and unable to seek justice or have their harm addressed (Blackwell et al. 2017). The nature of the harassment and the identity of those affected may also affect how effective remedies are (Schoenebeck et al. 2021).

Hence, it is critical to address cyberbullying with more than just taking down content and fining offenders. Goldman (2021) argues for a more complex strategy that takes into account aspects of responsibility, equity, and community engagement by drawing on legal research. Proposed solutions include public apologies and admissions of guilt, although there are questions about the sincerity and efficacy of these measures (Battistella 2014).

Not only does it help with enforcement, but it also validates victims' stories and educates the community (Matias 2019). Nevertheless, the preferred methods of addressing harassment can differ based on the specific kind of harassment experienced and the identities at play. Apologies, for instance, may not be preferred as solutions by certain marginalised groups if they believe that they are not genuine. According to Schoenebeck, Haimson, and Nakamura (2021), this further proves the importance of customised strategies.

Fundamentally, establishing efficient social media governance is critical for cultivating an online environment that promotes constructive interaction and courteous dialogue. Platforms may work towards making the internet a safer and more welcoming place for everyone by tackling the multifaceted problem of cyberbullying and giving a voice to those who have been harassed or victimised.

Social Media Governance, Online Harassment, and the Intersection of Digital Citizenship

Accounting for Harassment Types and Harm in Design and Policy

One of the biggest problems with digital citizenship is the prevalence of harassment and other forms of cyberbullying, which make it difficult to build safe and welcoming communities online. But to solve this problem, we need a sophisticated knowledge of the many kinds of harassment and the many degrees of damage they cause. According to Schoenebeck, Lampe, and Triệu (2023), different sorts of online harassment might lead to different perceptions of harm, thus it is important to categorise these talks accordingly. As an example, while verbal abuse may not seem as terrible as, say, sexually explicit images sent without consent might have serious consequences.

Furthermore, these danger judgements do not hold across all demographic categories. Despite bearing a disproportionate share of the burden of harm, marginalised groups, including women, the elderly, and people of colour, are grossly underrepresented in the halls of power that make tech policy. That is why it is crucial to listen to the people who have been most impacted by cyberbullying (e.g., Benjamin 2019; Noble 2018) before responding effectively. Social media governance practices can be enhanced by adopting victim-centred approaches rather than punitive measures, by incorporating principles of trauma-informed practice and affirmative consent (Im et al. 2021; Tseng et al. 2022).

Expanding Remedies for Reputational Harm

To effectively manage social media platforms, we need more tools to combat the complex kinds of online harassment. A more thorough consideration of reputational injury is being increasingly acknowledged, even though traditional remedies like content removal and user bans are still widely used (Schoenebeck, Lampe & Triệu 2023) In cultures that hold honour in high regard, the effects of relational and reputational forms of harassment—which are frequently disregarded by policy and legal frameworks—can be devastating. Harassment victims may face public shaming or even death for an alleged online violation, which can have a significant impact on their reputations in societies and cultures where honour is highly valued (Maher 2020).

On the other hand, solutions are not necessarily more effective in cases when harassment is more severe. Existing remedies may not be sufficient to offer meaningful redress in circumstances of extreme harm, such as doxxing or non-consensual distribution of sexual images. The trauma experienced by victims may be worsened by the difficulty they encounter in obtaining assistance and navigating the judicial system. Persistent traumatic experiences, also known as re-traumatisation or secondary trauma, can result from being the target of persistent harassment (Levenson 2017). Consequently, to better safeguard users from the most severe types of harassment, social media platforms should investigate novel ways, such as enhanced blocking capabilities and automated reporting systems.

Towards Holistic Social Media Governance

In the end, a comprehensive strategy that recognises the complex interplay between digital citizenship and online abuse is necessary for effective social media regulation. To address the wide variety of ways in which users have been harmed, platforms must move beyond generalisations about harassment. Blackwell et al. (2018) argued that social media sites can help create more secure and equitable online environments by giving a voice to underrepresented groups and giving priority to answers that centre on victims. Systems can be built to assist users in preventing harassment, for instance, by implementing automated reporting systems, elevating blocking methods, and making it easier for users to seek support when needed.

But to do this, present methods of government must be drastically rethought, shifting focus from punitive actions to proactive interventions that tackle systemic inequities. Social media sites can't do their part to prevent cyberbullying and promote good digital citizenship unless they take this comprehensive strategy.

Conclusion

Alright, fellow Tumblr aficionados, we've unpacked the complexities of online harassment and its tangled relationship with social media governance. This isn't just a matter of deleting nasty comments or hitting the block button. No, it's about fostering a culture of empathy, respect, and inclusivity in our digital spaces. By amplifying marginalised voices, prioritising victim-centred responses, and reimagining our approach to governance, we can pave the way for safer, more inclusive online communities. So, let's roll up our sleeves, demand accountability, and work towards a brighter, harassment-free digital future together. 💪✨

Additional Resources:

Towards Digital Platforms and Public Purpose: Final Report of the Democracy and Internet Governance Initiative | Shorenstein Center

Social media companies should stop normalising neo-fascism | Media@LSE

UNESCO brings together stakeholders to discuss the role of social media in promoting peace

References

Bailey, M 2021, Misogynoir Transformed, NYU Press.

Battistella, EL 2014, Sorry about that, Oxford University Press, USA.

Benjamin, R 2019, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code, John Wiley & Sons.

Blackwell, L, Chen, T, Schoenebeck, S & Lampe, C 2018, ‘When Online Harassment Is Perceived as Justified’, Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media.

Blackwell, L, Dimond, J, Schoenebeck, S & Lampe, C 2017, ‘Classification and Its Consequences for Online Harassment: Design Insights from HeartMob’, Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, p. 19.

Buckels, EE, Trapnell, PD & Paulhus, DL 2014, ‘Trolls Just Want to Have Fun’, Personality and Individual Differences, vol. 67, Elsevier BV, pp. 97–102.

Douek, E 2020, ‘The Limits of International Law in Content Moderation (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3709566)’, SSRN Electronic Journal, viewed <http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3709566>.

Duggan, M 2017, ‘Online Harassment 2017’, Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, viewed 15 March 2024, <https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/07/11/online-harassment-2017/>.

Fitzgerald, HE, Johnson, DJ, Qin, DB, Villarruel, FA & Norder, J 2019, Handbook of Children and Prejudice, Springer, Cham.

Gillespie, T 2018, Custodians of the Internet, Yale University Press.

Goldman, E 2021, ‘Content Moderation Remedies’, Michigan Technology Law Review, vol. 28, RELX Group (Netherlands), viewed 17 March 2024, <10.2139/ssrn.3810580>.

Gray, KL 2011, ‘Intersecting Oppressions and Online Communities’, Information, Communication & Society, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 411–428.

Gray, KL 2020, ‘Race and Media’, in LK Lopez (ed.), Race and Media, New York University Press, New York, USA, pp. 241–251.

Harms, L 2015, Understanding Trauma and Resilience, Bloomsbury Publishing.

Im, J, Dimond, J, Berton, M, Lee, U, Mustelier, K, Ackerman, MS & Gilbert, E 2021, ‘Yes: Affirmative Consent as a Theoretical Framework for Understanding and Imagining Social Platforms’, Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

Kaye, D 2019, Speech Police, Columbia Global Reports.

Kazerooni, F, Taylor, SH, Bazarova, NN & Whitlock, J 2018, ‘Cyberbullying Bystander Intervention: The Number of Offenders and Retweeting Predict Likelihood of Helping a Cyberbullying Victim’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 23, no. 3, Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 146–162.

Kowalski, RM, Giumetti, GW, Schroeder, AN & Lattanner, MR 2014, ‘Bullying in the Digital Age: A Critical Review and Meta-Analysis of Cyberbullying Research among Youth’, Psychological Bulletin, vol. 140, no. 4, pp. 1073–1137.

Langos, C 2014, ‘Cyberbullying: The Shades of Harm’, Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 106–123.

Lenhart, A, Ybarra, M, Zickuhr, K & Myeshia Price-Feeney 2016, ‘Online Harassment, Digital Abuse, and Cyberstalking in America’, Data & Society, Data & Society Research Institute, viewed 15 March 2024, <https://datasociety.net/library/online-harassment-digital-abuse-cyberstalking/>.

Levenson, JS 2017, ‘Trauma-Informed Social Work Practice’, Social Work, vol. 62, no. 2, Oxford University Press, pp. 105–113.

Lirri, E 2015, ‘The Challenge of Tackling Online Violence against Women in Africa’, OpenNet Africa, viewed 15 March 2024, <https://www.opennetafrica.org/the-challenge-of-tackling-online-violence-against-women-in-africa/>.

Maher, S 2020, A woman like her: The story behind the honor killing of a social media star, Melville House.

Marwick, AE 2021, ‘Morally Motivated Networked Harassment as Normative Reinforcement’, Social Media + Society, vol. 7, no. 2.

Massanari, A 2017, ‘#Gamergate and the Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and Culture Support Toxic Technocultures’, New Media & Society, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 329–346.

Matias, JN 2019, ‘Preventing Harassment and Increasing Group Participation through Social Norms in 2,190 Online Science Discussions’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, National Academy of Sciences, pp. 9785–9789.

Noble, SU 2018, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism, NYU Press.

Pskowski, M 2017, ‘Mexican Women Stand up to Cyberattacks and Vicious Digital Violence’, The World, viewed 15 March 2024, <https://theworld.org/stories/2017-08-24/mexican-women-stand-cyberattacks-and-vicious-digital-violence>.

Rainie, L, Anderson, J & Albright, J 2017, ‘The Future of Free Speech, Trolls, Anonymity and Fake News Online’, Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, viewed 15 March 2024, <https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/03/29/the-future-of-free-speech-trolls-anonymity-and-fake-news-online/>.

Roberts, ST 2019, Behind the Screen, Yale University Press.

Rocha-Silva, T, Nogueira, C & Rodrigues, L 2021, ‘Intimate Abuse through technology: a Systematic Review of Scientific Constructs and Behavioral Dimensions’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 122, Elsevier BV, p. 106861.

Schoenebeck, S, Haimson, OL & Nakamura, L 2021, ‘Drawing from Justice Theories to Support Targets of Online Harassment’, New Media & Society, vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 1278–1300.

Schoenebeck, S, Lampe, C & Triệu, P 2023, ‘Online Harassment: Assessing Harms and Remedies’, Social Media + Society, vol. 9, no. 1.

Schoenebeck, S, Scott, CF, Hurley, EG, Chang, T & Selkie, E 2021, ‘Youth Trust in Social Media Companies and Expectations of Justice’, Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, pp. 1–18.

Stewart, A, Schuschke, J & Tynes, B 2019, ‘Online Racism: Adjustment and Protective Factors Among Adolescents of Color’, Springer eBooks, Springer Nature, pp. 501–513, viewed 17 March 2024, <https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-12228-7_28>.

Tseng, E, Sabet, M, Bellini, R, Harkiran Kaur Sodhi, Ristenpart, T & Dell, N 2022, ‘Care Infrastructures for Digital Security in Intimate Partner Violence’, CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’22).

Vogels, EA 2021, ‘The State of Online Harassment’, Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, viewed 15 March 2024, <https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/>.

Wolak, J, Mitchell, KJ & Finkelhor, D 2007, ‘Does Online Harassment Constitute Bullying? an Exploration of Online Harassment by Known Peers and Online-Only Contacts’, Journal of Adolescent Health, vol. 41, no. 6, Elsevier BV, pp. S51–S58.

World Health Organization 2021, ‘Violence against Women’, Who.int, World Health Organization: WHO, viewed 16 March 2024, <https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women>.

#digital communities#mda20009#week 10#social media governance#social media apps#policies#social media strategy#online harassment#cyber bullying

0 notes

Text

// Week 9: Gaming //

Exploring the Intersection of Gaming Communities, Live Streaming, and Parasocial Relationships

As a result of both technical developments and the increasing number of people who like to play games online, the online gaming industry is thriving in today's digital world. As a people, we live in what academics call a "gameful," "ludified" civilisation, where gaming cultures are essential manifestations of our culture (Walz & Deterding 2015; Sutton-Smith 2001).

Gaming has always been social, encouraging players to meet in person and share experiences, from the first days of arcades to the emergence of local area network (LAN) parties (Newman 2012; Jansz & Jansz 2005). It seemed, though, that the social component of gaming waned as the medium shifted towards being played more alone in people's living rooms. However, a new channel opened up with the introduction of video game streaming, reigniting the communal fibre of gaming culture.

According to Ritterfeld, Cody, and Vorderer (2009), pp. 67-82, video game (VG) communities have evolved into active online gathering places where people come together for common interests and form groups voluntarily, without any official oversight. These groups go beyond the internet and combine the virtual and physical environments to form what academics call "third spaces" for socialising (Handberg 2015; Bourgonjon & Soetaert 2013). The ideas of personal connection and shared information sharing are fundamental to this dynamic and help to characterise VG communities as places where people may come together to learn and socialise (Ritterfeld, Cody & Vorderer 2009, pp. 67-82). Participants not only discover common ground but also participate in instructional activities similar to those of learning communities within these online settings.

With live streaming at its core, this convergence is all about gamers broadcasting their games for others to watch and engage with in real time. By allowing streamers and watchers to form parasocial ties, this activity has brought back the social spectating aspect that is inherent to gaming. In this Tumblr post, we explore the complex dynamics of gaming communities, live streaming, and parasocial interactions. We look at how these phenomena impact gaming culture today and how they change the way people engage online. Come with me as we explore the intriguing junction of human connection, community, and technology. 🎮✨

The Emergence of Live Streaming: Gaming Communities and Interactive Media

With the massive influx of consumers to live-streamed gaming sites like Twitch in recent years, the online entertainment landscape has experienced a dramatic change. Reasons for this meteoric rise in popularity include people's insatiable need for interactive media experiences, the abundance of user-generated material, and technological developments (Sjblom & Hamari 2017). Twitch and similar services have had meteoric rises in popularity, with the number of users tripling annually and reaching over 100 million monthly. As of 2023 (according to Advanced Television), Twitch had a staggering 74% market share, demonstrating its continued dominance in the global streaming audience, even though the number of streamers has fluctuated.

The live broadcasting aspect of video game streaming facilitates a unique relationship between content providers and consumers, which is at the core of this phenomenon. In contrast to conventional modes of media consumption, live streaming provides a dynamic exchange platform wherein the conventional viewer assumes the responsibility of generating content while engaging in extensive dialogue (Cha et al. 2007).

Platforms such as Twitch, Mixer, and Afreeca TV have made live streaming more accessible, enabling users to share events and interactions in real time with audiences all over the world. There has been a meteoric rise in the number of people watching streamers, especially those who play video games live and engage with their viewers (Ferchaud et al. 2018).

The combination of high-fidelity audiovisual information delivery with low-fidelity text-based conversation is what makes live streaming so unique; it's a dynamic and engaging experience for everyone involved (Hamilton, Garretson & Kerne 2014). Live streaming, which was once only available for game content, is now a staple of contemporary gaming culture and has grown to include many other types of broadcasting (Li et al. 2018). Live streaming services, such as Twitch, encourage participation in communities where users share interests, learn from one another, and build relationships—a phenomenon that has led some to call these spaces virtual third places. A sense of authenticity and closeness is enhanced for numerous individuals through live broadcasting, which provides access to the unaltered lives of streamers (Tang, Venolia & Inkpen 2016).

Younger age groups, specifically, incorporate live streaming into their everyday schedules as a method of connecting with acquaintances and engaging in social interactions (Lottridge et al. 2017). People watch live streams for a variety of reasons, including enjoyment, socialising, learning new things, and satisfying social needs (Hilvert-Bruce et al. 2018).

The importance of parasocial relationships in livestream enjoyment is highlighted by Wulf, Schneider, and Beckert (2018). Elements like the anticipation of game results and participation in the chat function contribute to this satisfaction. As the analysis of parasocial relationships in live streaming progresses, the complex interaction between content creators and their audience becomes more apparent, significantly influencing the framework of online entertainment.

The Role of Parasocial Relationships in Live Streaming

One reason live streaming is so popular is that viewers have an inherent desire to learn new strategies for playing games by watching the shows and listening to the host's commentary. Conversely, individuals who watch televised sports and entertainment programmes have "an inherent desire to establish interpersonal relationships" (Hoffner & Buchanan 2009).

According to Dibble, Hartmann, and Rosaen (2015), a parasocial relationship (PSR) is an intimate and one-sided bond that develops between a media personality or celebrity and their audience as a result of their frequent interactions in mediated reality. The potential for audiences and media personalities to engage in parasocial interactions (PSI) is enhanced through the interactivity provided by online environments, which is facilitated by functional properties (Labrecque 2014).

Reinforcing PSR can also be achieved through cultivating mutual awareness. When a game streamer recognises and/or mentions viewers during broadcasting, it may increase the perceived mutual awareness, in contrast to passive entertainment consumption. The ability to converse with viewers in real-time gives live-streamers like YouTubers and others a leg up when compared to more conventional celebrities (Hou 2019). Therefore, compared to other forms of digital media, watching live-streamed games is more conducive to the development of PSR (Lim et al. 2020).

The Intersection of Digital Citizenship, Live Streaming, and Parasocial Relationships

Having fluidly moved on from the topic of parasocial relationships and game live streaming, we now explore the fascinating confluence of digital citizenship, live streaming, and parasocial relationships. This fusion effectively illustrates the manner in which digital platforms reshape our emotional experiences and redefine our social landscapes. Within the domains of online gaming groups and live-streaming platforms, there exists an intriguing concoction of virtual relationships and human emotions.

A fascinating focal point in the dynamic realm of digital citizenship is the phenomena of live streaming and the complex interplay it has with parasocial relationships. The multidimensional nature of gaming communities is shown by the fact that games can be enjoyed both actively and passively, as explained by Sjblom and Hamari (2017). Live streaming systems such as Twitch also adhere to this principle, allowing viewers to establish relationships with their favourite streamers even though the interaction is inherently biased.

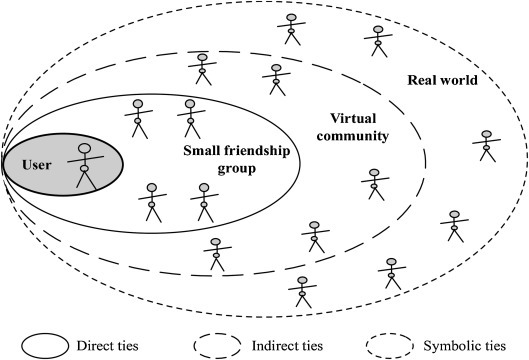

Gong et al. (2019) emphasised that people traverse complicated social dynamics within these digital environments, developing tiny friendship groups and affiliating with virtual communities. A fundamental human need for association and camaraderie drives the desire for socialisation and group-referent behaviours (Tsai & Bagozzi 2014). People feel more connected to themselves and their communities when they spend more time there, and the social and informational factors they encounter there only serve to strengthen that feeling (Dholakia, Bagozzi & Pearo 2004).

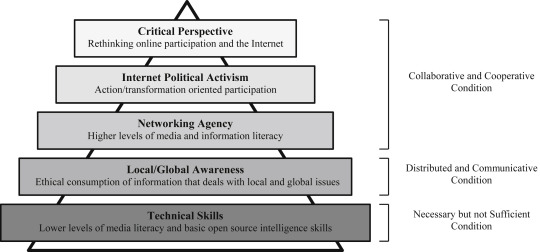

In the following figure, we can see how users, small friendship groups, and virtual communities are connected:

The rise of live-streaming platforms has intensified parasocial ties, in which viewers create close bonds with streamers and frequently feel affection and camaraderie towards them (Bagozzi & Dholakia 2002). Even if they take place in a virtual setting, these connections still satisfy a basic human desire for social connection. Nevertheless, a darker subtext can be observed in the digital realm, as highlighted by the YouTuber "Glink": an all-encompassing feeling of isolation. Paradoxically, people are becoming even more isolated as they seek refuge in the fleeting connections provided by live streaming platforms, despite the internet's once-heralded role as a means of escaping reality.

youtube

Conclusion

There are a lot of moving parts in this complex web of parasocial relationships, online citizenship, and live streaming. In light of our exploration of the internet, it is crucial to approach the consequences of our online engagements with a discerning eye, bearing in mind the precarious equilibrium that exists between interconnectedness and seclusion. At the end of the day, we can all benefit from healthier, more fulfilling online communities—not just gaming communities—by learning about and encouraging meaningful digital citizenship behaviours.

References

Advanced Television 2023, ‘Data: Twitch Losing Users’, Advanced Television Ltd , 4 September, viewed 10 March 2024, <https://advanced-television.com/2023/09/04/data-twitch-losing-users/>.

Bagozzi, RP & Dholakia, UM 2002, ‘Intentional Social Action in Virtual Communities’, Journal of Interactive Marketing, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 2–21.

Bourgonjon, J & Soetaert, R 2013, ‘Video Games and Citizenship’, CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, vol. 15, no. 3.

Cha, M, Kwak, H, Rodriguez, P, Ahn, Y-Y & Moon, S 2007, ‘I tube, You tube, Everybody tubes: Analyzing the world’s Largest User Generated Content Video System’, IMC ’07: Proceedings of the 7th ACM SIGCOMM Conference on Internet Measurement, Association for Computing Machinery, New York.

Dholakia, UM, Bagozzi, RP & Pearo, LK 2004, ‘A Social Influence Model of Consumer Participation in network- and small-group-based Virtual Communities’, International Journal of Research in Marketing, vol. 21, no. 3, Elsevier BV, pp. 241–263.

Dibble, JL, Hartmann, T & Rosaen, SF 2015, ‘Parasocial Interaction and Parasocial Relationship: Conceptual Clarification and a Critical Assessment of Measures’, Human Communication Research, vol. 42, no. 1, Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 21–44.

Ferchaud, A, Grzeslo, J, Orme, S & LaGroue, J 2018, ‘Parasocial Attributes and YouTube personalities: Exploring Content Trends across the Most Subscribed YouTube Channels’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 80, Elsevier BV, pp. 88–96.

Glink 2020, The Parasocial Problem with Livestreaming, 3 July, viewed 13 March 2024, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GvYAVti8nbk>.

Gong, X, Zhang, KZK, Cheung, CMK, Chen, C & Lee, MKO 2019, ‘Alone or together? Exploring the Role of Desire for Online Group Gaming in Players’ Social Game Addiction’, Information & Management, vol. 56, no. 6, Elsevier BV, pp. 103139–103139.

Hamilton, WA, Garretson, O & Kerne, A 2014, ‘Streaming on twitch: Fostering Participatory Communities of Play within Live Mixed Media’, CHI ’14: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, pp. 1315–1324.

Handberg, K 2015, ‘No Time like the past? on the New Role of Vintage and Retro in the Magazines SCANDINAVIAN RETRO and RETRO GAMER’, NECSUS. European Journal of Media Studies, vol. 4, no. 2, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 165–185.

Hilvert-Bruce, Z, Neill, JT, Sjöblom, M & Hamari, J 2018, ‘Social Motivations of live-streaming Viewer Engagement on Twitch’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 84, Elsevier BV, pp. 58–67.

Hoffner, C & Buchanan, M 2009, ‘Young Adults’ Wishful Identification with Television Characters: the Role of Perceived Similarity and Character Attributes’, Media Psychology, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 325–351.

Hou, M 2019, ‘Social Media Celebrity and the Institutionalization of YouTube’, Convergence, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 534–553.

Jansz, J & Jansz, J 2005, ‘Gaming at a LAN event: the Social Context of Playing Video Games’, New Media & Society, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 333–355.

Labrecque, LI 2014, ‘Fostering Consumer–Brand Relationships in Social Media Environments: The Role of Parasocial Interaction’, Journal of Interactive Marketing, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 134–148.

Li, Y, Kou, Y, Lee, JS & Kobsa, A 2018, ‘Tell Me before You Stream Me: Managing Information Disclosure in Video Game Live Streaming’, Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp. 1–18.

Lim, JS, Choe, M-J, Zhang, J & Noh, G-Y 2020, ‘The Role of Wishful identification, Emotional engagement, and Parasocial Relationships in Repeated Viewing of live-streaming games: a Social Cognitive Theory Perspective’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 108, Elsevier BV, p. 106327.

Lottridge, D, Bentley, F, Wheeler, M, Lee, J, Cheung, J, Ong, K & Rowley, C 2017, ‘Third-wave livestreaming: teens’ Long Form Selfie’, MobileHCI ’17: Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp. 1–12.

Newman, J 2012, ‘Videogames’, Routledge eBooks, 2nd Edition., Routledge, London.

Ritterfeld, U, Cody, M & Vorderer, P 2009, Serious Games: Mechanisms and Effects, Routledge, pp. 67–82.

Sjblom, M & Hamari, J 2017, ‘Why Do People Watch Others Play Video games? an Empirical Study on the Motivations of Twitch Users’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 75, Elsevier BV, pp. 985–996.

Sutton-Smith, B 2001, ‘The Ambiguity of Play’, Harvard University Press, Harvard University Press.

Tang, JC, Venolia, G & Inkpen, KM 2016, ‘Meerkat and Periscope: I Stream, You Stream, Apps Stream for Live Streams’, CHI ’16: Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp. 4770–4780.

Tsai, H-T & Bagozzi, RP 2014, ‘Contribution Behavior in Virtual Communities’, MIS Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 143–164.

Walz, SP & Deterding, S (eds) 2015, ‘The Gameful World’, The MIT Press eBooks, The MIT Press.

Wulf, T, Schneider, FM & Beckert, S 2018, ‘Watching Players: an Exploration of Media Enjoyment on Twitch’, Games and Culture, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 328–346.

#mda20009#digital communities#gaming#video games#livestream#twitch#parasocial relationships#virtual community#game lover#Youtube#week 9

0 notes

Text

// Week 8: Instagram Filters //

Pixel Perfect: Navigating the Digital Mirage of Instagram Filters and AR Effects

Hey there, fellow nomads of the internet! Get ready to embark on an adventure through the colourful world of Instagram filters and AR effects. Aesthetics, identity, and self-perception are linked in this fleeting world of pixels and perfection, where every selfie tells a narrative and every swipe uncovers a new facade.

Imagine a future where digital magic makes all your dreams come true at the touch of a finger, where regular people may accessorise their faces with magical crowns and halos, and where digital magic can hide any flaws. This is the captivating charm of Instagram filters; they invite us to discover the boundless potential for individual expression and creativity.

However, beyond the surface of apparent attractiveness is a more profound reality, one shrouded in the gloom of cultural mores and social mores. As we explore the intricate web of our online personas, we will inevitably face the disturbing truth that these filters influence how we view femininity, self-worth, and physical attractiveness.

Fasten your seatbelts, my friends, for you are about to go on a fantastical adventure through the looking glass, a place where fact and fiction blend together and where, in the midst of a digital mirage, you may find your authentic identity.

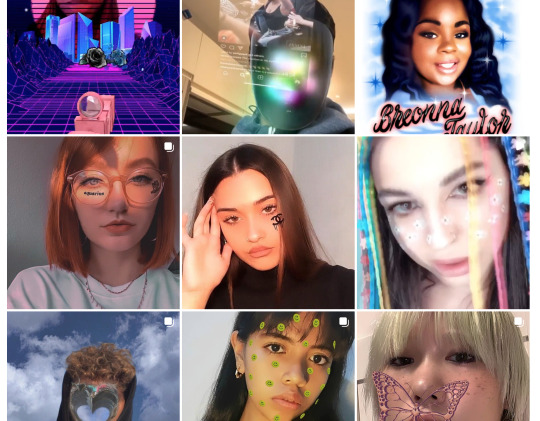

The Rise of Instagram Filters

Visual content, such as photos and videos, is the bread and butter of social media platforms like Instagram. To facilitate this, site designers have poured resources into tools like filters, airbrushing, and photo editing options (Vendemia & DeAndrea 2018). More over a third of Instagram's users fall within the 18–29 age bracket, thus this is likely to resonate with them (Anderson 2023). Augmented reality (AR) filters are the most recent and game-changing addition to this toolbox; users can superimpose various effects on their faces, such as "cool" clothing, enhanced facial characteristics, imaginary creatures, or even "silly" items like a birthday hat. Augmented reality (AR) effects have made it possible to superimpose virtual information on top of a user's real-world surroundings, allowing for real-time interaction as if the user were physically present in the real location (Hilken et al. 2017). For instance, the Instagram account @face.effects has 191,000 followers and is known for its frequent filter releases that showcase various effects, such as those that are imaginative, political, humorous, goofy, or animal-like.

The use of augmented reality face filters offers a distinct opportunity to enhance one's self-presentation, as has been shown in earlier studies (Erz, Marder & Osadchaya 2018; Javornik et al. 2021). Furthermore, compared to its contemporaries like Facebook or Twitter, Instagram appears to prioritise self-presentation and self-promotion above the development and maintenance of connections (Sheldon & Bryant 2016). Actually, Instagram's layout subtly promotes users to portray an idealised version of themselves online (Hu, Manikonda & Kambhampati 2014).

People using Instagram feel extra pressure to display themselves attractively because the network is centred upon altering and sharing images. Users may resort to a range of deceitful behaviours in an effort to cope with their heightened social concerns. Instagram users may, for instance, alter photos before, during, or after taking them, or chose older photos that they find more beautiful to utilise on their profiles (Hancock & Toma 2009). With Instagram's augmented reality filters, users may improve their material in a variety of ways, including modifying images. And with the help of easily accessible Photoshop knockoff apps, users may do digital cosmetic surgery to further alter their online persona. A significant incentive for participating in this visually deceitful conduct is the augmented probability of the image achieving success on the internet. Dumas et al. (2017) cites prior research that indicates Instagram's "like"-based design acts as a positive reinforcement system that consistently pushes users to showcase themselves.

In addition, users know that their post might be seen by more people than just their friends and family on Instagram because accounts are set to public by default. This creates a paradox in which Instagram serves to promote and encourage self-presentation. Fundamentally, the accessibility of images to unfamiliar individuals on the internet has led to heightened societal expectations regarding one's self-presentation. Simultaneously, the increased engagement with strangers online facilitates a more calculated and idealised self-presentation by eliminating social responsibility (Walther, Slovacek & Tidwell 2001). Since Instagram allows users to communicate with people outside of their personal social circle on a regular basis, it stands to reason that users will continue to showcase themselves on the platform. On the surface, Instagram is unique among social media platforms because it encourages users to promote themselves while offering a veneer of anonymity, which sets it apart from other platforms.

Recognising the Purpose: What Makes Us Apply Filters?

For example, when people use social media to reveal secret parts of themselves or to help them explore their identity, it can have a positive effect on their mental health (Yau, Marder & O'Donohoe 2019). Users initiate an intricate process of visually representing themselves when they virtually alter their physical attributes in instantaneously for the purpose of self-presentation. This transformation is motivated by their aspirations, authentic selves, and evolved selves. When it comes to the self, research has shown that users are more likely to visually associate with other entities when using augmented reality filters. This supports the idea that AR overlays are a powerful tool for online activities that have personal significance (Rifkin & Etkin 2019). Additionally, augmented reality can be used to engage users in cause-related activities and raise awareness (Kristofferson, White & Peloza 2014).

Although creativity has been found to be a common motivation for social media use (Sheldon et al., 2017), Javornik et al. (2022) found that augmented reality face filters encourage a particular form of creativity. In particular, augmented reality filters facilitate and encourage originality in the selection of aesthetically pleasing interactive material for social networking platforms. Instagram, like other social media platforms, relies on user-generated content (UGC) to function (Kostyk & Huhmann, 2021). This content can range from dramatic displays of admiration or preferences to more subtle attempts to get attention (Bigley & Leonhardt, 2018). Because of their one-of-a-kind properties, augmented reality filters offer a fresh platform for content creation. These filters allow for the seamless and realistic overlay of virtual objects in real-time.

As previously stated reasons for augmented reality adoption (Jang & Liu 2018), AR face filters are mostly driven by fun and social interactions. Recognising enjoyment as a key factor in both exploratory and frequent use of digital technology highlights the significance of hedonic satisfaction in this context (McLean & Osei-Frimpong 2019). The ability to facilitate communication with others is yet another important factor in the widespread adoption of various forms of electronic media (Sheldon et al. 2017). Particularly, augmented reality filters are employed to start conversations, attract people' interest, and commence social connections. The complexities of online social psychology are growing as users engage in virtual self-augmentation in pursuit of social relationships (Turkle 2009). Additionally, one utilitarian incentive for augmented reality filter interactions is ease. This finding aligns with previous research that has identified efficiency, convenience, and simplicity of use as utilitarian motivations that take precedence over the utilisation of platforms and features (Rauschnabel 2018).

The well-being effects of augmented reality facial filters: how do users feel?

The ramifications of digitally altering one's appearance transcend superficial aesthetics (Lee & Lee 2021). It intersects with the intricate phenomenon known as digitised dysmorphia, which functions on a continuum with body dysmorphic disorder. Perceived social constraints, cultural beauty standards and the availability of image-editing technologies shape this form of socially conditioned dysmorphia (Coy-Dibley 2016). This dysmorphic perspective, especially when it comes to female bodies, has been made easier and more intense by advances in picture technology. The prevalence of digitally changed depictions in modern fashion and advertising has skewed public views of women's bodies negatively.

Selfie enhancement can lead to "Selfie dysmorphia," a related phenomena in which users report low self-esteem and an exaggerated sense of their own body (Rajanala, Maymone & Vashi 2018). AR filters may amplify this issue, given that virtual modifications transpire in real time and possess a greater degree of realism. It has been found to drive some individuals to seek out cosmetic surgery in extreme instances (Hunt 2019). This supports the idea that augmented reality makeup try-on can alter people's ideal-actual gap and reduce their tolerance for perceived appearance defects, and it also shows how this popular social media feature can influence a user's self-concept and, by extension, their subjective well-being (Ryff 1989; Javornik et al. 2021). Additionally, users' self-perceptions can be negatively impacted by idealising or fabricating their online personas. This highlights the negative effects of social media on promoting unrealistic expectations of body image (Hogue & Mills 2019) and continual comparison to others (Chae 2017).

Nevertheless, Javornik et al. (2022) demonstrated through their thorough research that using AR filters for self-transformation or authentic self-presentation might result in good consequences. Pera, Quinton, and Baima (2020) found a positive correlation between social media use and self-acceptance among members of the LGBT community and the elderly. Creative content curation, genuine and altered self-presentation, enjoyment, and social engagement all contributed to an uplifted mood. On the flip side, data that are just marginally significant provide some evidence that an idealised version of oneself may reduce good emotion.

Javornik et al. (2022) found that users' moods can be lifted by utilising filters to increase social engagement, despite previous research showing that users can be anxious about how their content will be perceived by their social contacts (Alkis, Kadirhan & Sat 2017). Filters enhance users' sense of connection with others by facilitating additional online social interactions such as comments, likes, and emoticons (Sheldon et al. 2017). As a result, filters function as a social lubricant.

Future Implications for Digital Citizens

When thinking about how to promote responsible and ethical behaviour online, the ubiquitous use of AR effects and Instagram filters brings up fundamental questions about digital citizenship. Several outcomes arise as individuals interact with these technologies to improve their online presence and communication:

Promoting Media Literacy: The capacity to understand and effectively use digital media is a cornerstone of digital citizenship. Stressing the significance of media literacy skills to social media users is crucial in light of the proliferation of digitally altered photographs and the pressure to conform to unattainable beauty standards. Users can be empowered to make better-informed judgements online by being educated about the potential implications of excessive filter use and encouraged to critically reflect on digitally modified content (Kozyreva et al. 2023).

Advocating for Ethical Technology Use: Promoting responsible and ethical use of technology that acknowledges and protects the rights and welfare of others is an important part of being a good digital citizen. Jhaver et al. (2022) assert that it is the duty of social media platforms and their developers to ensure that the design and regulation of filters foster constructive online interactions while mitigating potential negative consequences. In addition to upholding the principles of integrity, empathy, and respect in their online interactions, users ought to be motivated to contemplate the ethical ramifications of their digital behaviours, such as the implementation of filters.

Empowering Responsible Digital Choices: At its core, digital citizenship is all about giving people the tools they need to live their digital lives responsibly and ethically. A more welcoming and supportive online community can be achieved when people are more educated about the consequences of filter use, develop their capacity for critical thinking, and work to establish a culture of digital empathy and respect. Together, we can protect ourselves and others from the worst aspects of social media while also taking use of its many great features, such as the ability to express ourselves creatively and make meaningful connections with others.

In summary, the proliferation of Instagram filters and augmented reality (AR) effects highlights the criticality of advocating for conscientious digital citizenship behaviours that place emphasis on media literacy, appropriate self-perception, ethical utilisation of technology, genuine online persona, and empowered decision-making in the digital realm. A more welcoming, considerate, and egalitarian online community can be achieved through critical discourse and joint initiatives to encourage beneficial digital behaviours.

Conclusion

In the vibrant social media maze, Instagram filters and augmented reality effects have replaced real-life artists with virtual ones, letting us create vivid, enhanced selves. Amidst the charm of flawless pictures and magical makeovers, it's important to stop and think about the bigger picture of our digital beauty quests.

Recognising the possible pitfalls of delving into a healthy connection with digital aesthetic identity and self-perception via the lens of the pathologization of women's bodies is crucial. Staying alert against the spread of damaging stereotypes and unattainable beauty standards is essential as we explore this online space for self-expression and beauty.

Let us not forget to embrace diversity, celebrate imperfection, and cultivate true connections beyond the glossy sheen of our online personalities as we strive for authenticity in the middle of pixels and filters. We should work towards a world where people are empowered rather than insecure, and where they are valued for who they are rather than how they look on screen.

Additional Resources:

"THE PROBLEM WITH SOCIAL MEDIA FILTERS (mental health, colourism, unhealthy beauty standards)”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wByiJGw7Z7o

"influencers aren't to blame for the toxic beauty standards. we are.”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NgKbO-eT3oQ

References

Alkis, Y, Kadirhan, Z & Sat, M 2017, ‘Development and Validation of Social Anxiety Scale for Social Media Users’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 72, Elsevier BV, pp. 296–303.

Anderson, M 2023, ‘Teens, Social Media and Technology 2023’, Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, 11 December, viewed 12 March 2024, <https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2023/12/11/teens-social-media-and-technology-2023/>.

Bigley, IP & Leonhardt, JM 2018, ‘Extremity Bias in User-Generated Content Creation and Consumption in Social Media’, Journal of Interactive Advertising, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 125–135.

Chae, J 2017, ‘Virtual makeover: Selfie-taking and Social Media Use Increase selfie-editing Frequency through Social Comparison’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 66, Elsevier BV, pp. 370–376.

Choi, TR & Sung, Y 2018, ‘Instagram versus Snapchat: Self-expression and Privacy Concern on Social Media’, Telematics and Informatics, vol. 35, no. 8, Elsevier BV, pp. 2289–2298.

Coy-Dibley, I 2016, ‘“Digitized Dysmorphia” of the Female body: The re/disfigurement of the Image’, Palgrave Communications, vol. 2, no. 1, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 16040.

Dumas, TM, Maxwell-Smith, M, Davis, JP & Giulietti, PA 2017, ‘Lying or Longing for likes? Narcissism, Peer belonging, Loneliness and Normative versus Deceptive like-seeking on Instagram in Emerging Adulthood’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 71, Elsevier BV, pp. 1–10.

Erz, A, Marder, B & Osadchaya, E 2018, ‘Hashtags: Motivational drivers, Their use, and Differences between Influencers and Followers’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 89, Elsevier BV, pp. 48–60.

Hancock, JT & Toma, CL 2009, ‘Putting Your Best Face Forward: the Accuracy of Online Dating Photographs’, Journal of Communication, vol. 59, no. 2, Oxford University Press, pp. 367–386.

Hilken, T, Ruyter, K de, Chylinski, M, Mahr, D & Keeling, DI 2017, ‘Augmenting the Eye of the beholder: Exploring the Strategic Potential of Augmented Reality to Enhance Online Service Experiences’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, vol. 45, no. 6, Springer Science+Business Media, pp. 884–905.

Hogue, JV & Mills, JS 2019, ‘The Effects of Active Social Media Engagement with Peers on Body Image in Young Women’, Body Image, vol. 28, Elsevier BV, pp. 1–5.

Hu, Y, Manikonda, L & Kambhampati, S 2014, ‘View of What We Instagram: A First Analysis of Instagram Photo Content and User Types’, Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, pp. 595–598.

Hunt, E 2019, ‘Faking it: How Selfie Dysmorphia Is Driving People to Seek Surgery’, The Guardian, The Guardian, viewed 7 March 2024, <https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/jan/23/faking-it-how-selfie-dysmorphia-is-driving-people-to-seek-surgery>.

Jang, S & Liu, Y 2018, ‘Continuance Use Intention with Mobile Augmented Reality games: Overall and Multigroup Analyses on Pokémon Go’, Information Technology & People, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 37–55.

Javornik, A, Marder, B, Barhorst, JB, McLean, G, Rogers, Y, Marshall, P & Warlop, L 2022, ‘“What Lies behind the filter?” Uncovering the Motivations for Using Augmented Reality (AR) Face Filters on Social Media and Their Effect on well-being’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 128, Elsevier BV, pp. 107126–107126.

Javornik, A, Marder, B, Pizzetti, M & Warlop, L 2021, ‘Augmented Self - the Effects of Virtual Face Augmentation on consumers’ self-concept’, Journal of Business Research, vol. 130, Elsevier BV, pp. 170–187.

Jhaver, S, Chen, QZ, Knauss, D & Zhang, AX 2022, ‘CHI ’22: Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems’, ACM Conferences, pp. 1–21.

Kostyk, A & Huhmann, BA 2021, ‘Perfect Social Media Image posts: Symmetry and Contrast Influence Consumer Response’, European Journal of Marketing, vol. 55, no. 6, pp. 1747–1779.

Kozyreva, A, Wineburg, S, Lewandowsky, S & Hertwig, R 2023, ‘Critical Ignoring as a Core Competence for Digital Citizens’, Current Directions in Psychological Science, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 81–88.

Kristofferson, K, White, K & Peloza, J 2014, ‘The Nature of Slacktivism: How the Social Observability of an Initial Act of Token Support Affects Subsequent Prosocial Action’, Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 40, no. 6, Oxford University Press, pp. 1149–1166.

Lee, M & Lee, H-H 2021, ‘Social Media Photo activity, internalization, Appearance comparison, and Body satisfaction: the Moderating Role of photo-editing Behavior’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 114, Elsevier BV, p. 106579.

McLean, G & Osei-Frimpong, K 2019, ‘Hey Alexa … Examine the Variables Influencing the Use of Artificial Intelligent in-home Voice Assistants’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 99, Elsevier BV, pp. 28–37.

Pera, R, Quinton, S & Baima, G 2020, ‘I Am Who I am: Sharing Photos on Social Media by Older Consumers and Its Influence on Subjective Well‐being’, Psychology & Marketing, vol. 37, no. 6, Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 782–795.

Rajanala, S, Maymone, MBC & Vashi, NA 2018, ‘Selfies—Living in the Era of Filtered Photographs’, JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 443–444.

Rauschnabel, PA 2018, ‘Virtually Enhancing the Real World with Holograms: An Exploration of Expected Gratifications of Using Augmented Reality Smart Glasses’, Psychology & Marketing, vol. 35, no. 8, Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 557–572.

Rifkin, JR & Etkin, J 2019, ‘Variety in Self-Expression Undermines Self-Continuity’, Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 46, no. 4, Oxford University Press, pp. 725–749.

Ryff, C 1989, ‘Happiness Is everything, or Is it? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological well-being’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 57, no. 6, pp. 1069–1081.

Sheldon, P & Bryant, K 2016, ‘Instagram: Motives for Its Use and Relationship to Narcissism and Contextual Age’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 58, Elsevier BV, pp. 89–97.

Sheldon, P, Rauschnabel, PA, Antony, MG & Car, S 2017, ‘A cross-cultural Comparison of Croatian and American Social Network sites: Exploring Cultural Differences in Motives for Instagram Use’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 75, Elsevier BV, pp. 643–651.

Turkle, S 2009, ‘Constructions and Reconstructions of Self in Virtual reality: Playing in the MUDs’, Mind, Culture, and Activity, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 158–167.

Vendemia, MA & DeAndrea, DC 2018, ‘The Effects of Viewing thin, Sexualized Selfies on Instagram: Investigating the Role of Image Source and Awareness of Photo Editing Practices’, Body Image, vol. 27, Elsevier BV, pp. 118–127.

Walther, JB, Slovacek, CL & Tidwell, LC 2001, ‘Is a Picture Worth a Thousand Words?: Photographic Images in Long-Term and Short-Term Computer-Mediated Communication’, Communication Research, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 105–134.

Yau, A, Marder, B & O’Donohoe, S 2019, ‘The Role of Social Media in Negotiating Identity during the Process of Acculturation’, Information Technology & People, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 554–575.w

#digital communities#mda20009#filter#instagram#selfie dysmorphia#digital dysmorphia#digital well being#creativity#week 8

0 notes

Text

// Week 7: Body Modification //

Exploring the Effects of Social Media on Body Image: An Analysis and Potential Solutions

Returning to our humble online abode, I, Phuong Linh, will be shedding light on the intricate web of modern body image. The relationship between our self-perception and the digital sphere gets more complex in a world where social media bombards us with filtered perfection and idealised norms. Come along as I take you on a tour of the empowering concept of body neutrality, the rise of digital health solutions, and the influence of social media on body image. 💋👀

The Role of Social Media on the Perception of One's Body

As pointed out by Cohen et al. (2019), social media platforms expose users to an endless flow of well-selected physical pictures and appearances, which promote unrealistic ideals like the slender ideal for women and the muscular ideal for men. These platforms have a big impact on how people see their bodies and how they think about what it means to be beautiful and desirable.

Two important processes that media body image influences people's body dissatisfaction have been identified by research in media effects: social comparison with one's own body and internalisation of the shown standards (Fardouly & Holland 2018). Tiggemann and Zaccardo (2018) found that the majority of social media material reflects unrealistically high standards of beauty and promotes the purchase of goods and services to help one attain these unrealistic standards. There is a dearth of diversity in terms of gender presentation, aptitude, and youthfulness, and these notions of beauty revolve around slenderness, musculature, fairness, whiteness, and youth (Lazuka et al. 2020). Due to the prevalence of heavily manipulated photos depicting such features, the visual environment on social media only reflects a small portion of the diversity observed in the real world. Because of this, people are more likely to compare themselves to these unrealistic standards, which can cause them to struggle with their body image and even try to alter their appearance to fit in.

Damage to Self-Concept from Social Media

The complex contextual impacts of exposure to body image on social media have been recently studied. For example, Veldhuis, Konijn, and Knobloch-Westerwick (2016) showed that when seen as chances for self-improvement instead of rigid self-evaluation, contextualising body pictures can lead to positive results like greater body satisfaction. Similarly, Veldhuis, Konijn, and Seidell (2014) discovered that when unrealistically slim bodies were portrayed as attractive and within reach, young adults, especially teenage girls, were more prone to idealise such bodies, which in turn led to improvements in their views and attitudes towards weight. The significance of comprehending how the setting of body images affects people's views and anxieties about their bodies is highlighted by these results.

The already convoluted discourse surrounding body image is further complicated by the participatory character of social media, where users' remarks are widely visible alongside posted content. Social media comments have the power to reinforce or challenge cultural norms of beauty, as seen in Kim's (2021) research on the topic. It is worth mentioning that negative comments can help with body image issues by encouraging a broader definition of beauty. This is in keeping with prior research by Waddell and Sundar (2017) that highlights the bandwagon effects of comments in different media contexts, indicating that comments have the power to impact views that match the sentiments expressed. Peer pressure on social media may be a powerful tool for positive body image promotion, and it can also open doors to research into how people's everyday remarks affect their self-perception.

Furthermore, it has been said that social media platforms create a highly objectifying atmosphere, where people diminish their identity to self-portraits in search of monetary and social capital through favourable comments and attention from others (Salomon & Brown 2020). There is an inherent objectification in the act of building self-images and maintaining an online presence, which reduces people's subjectivity regarding their bodies and looks. According to Fardouly and Vartanian (2016), people's self-perceptions are further influenced by social reinforcement, also known as social grooming, which occurs through both explicit (comments) and implicit (likes or lack thereof) peer feedback. The pressure to adhere to social media beauty standards influences individuals' self-perception, leading to the objectification and commodification of the body in the online space.

Media platforms are also part of the larger neoliberal social framework. Jin, Muqaddam, and Ryu (2019) note that this is evident in the ubiquitous sponsorship, media personalities, and brand presence that characterise social media. As a result, the role of social media in the capitalist market has been acknowledged. This is on top of the actual physical capital that comes from being in close proximity to beauty standards, which in turn provides opportunities for social advancement and financial gain. Participation in modern society can be characterised through the curating of online displays and engagement in the process of making the body hypervisible on websites and apps (Rodgers & Rousseau 2022).

That being said, values presented in the media have the potential to be internalised, or cognitively endorsed, by individuals, particularly women, and therefore become ingrained in their belief systems (Calogero, Davis & Thompson 2005). Women may come to see themselves as something whose primary value is in how they look, a phenomenon known as self-objectification (Fredrickson & Roberts 1997). Additionally, Frederick and Roberts (1997) also postulated that women and girls are more likely to suffer from mental health issues like body image issues and anxiety when they perpetually fret about how other people will judge them. This compels them to monitor their own body and engage in vigilant self-surveillance constantly.

Emergence of Digital Health Interventions

Next, I want you to take a look at the survey below:

Krause, whose applications like Worth Warrior can help young people with their body image and eating problems, said, "The findings of this survey are deeply worrying." Her apps have been authorised by the NHS and are based on evidence. She brought attention to the troubling effects of social media on young people by saying, "When young people seek advice and information on social media, they find a warped and damaging reality." (Hill 2023). The problem is worsened because their internet searches frequently lead to disturbing material. These findings highlight the critical importance of finding answers and ways to cope with the detrimental impacts of social media on mental health and body image.

There has been a recent uptick in the use of digital health interventions as powerful means of improving women's physical and mental health as well as their perceptions of their own bodies. Many of these programmes take advantage of the widespread reach of the internet and social media to spread health-related messages and resources. However, there are complicated issues that arise from the interconnected dynamics of digital well-being, health, and appearance standards that must be thoughtfully considered and analysed (Monks et al. 2020).

To evaluate the efficacy of digital health interventions, it is essential to comprehend the societal influences on health and body image. According to Tiggemann and McGill (2005), negative effects like body shame and worry over one's appearance can be caused by media portrayals of idealised beauty standards, especially when viewed through the lens of social comparison. Even while most women may see these norms as unattainable, many nonetheless hold them in high regard, which leads to constant self-criticism and unhappiness (Buote et al. 2011). The importance of digital health treatments in promoting health while addressing unrealistic standards of beauty is highlighted by this pervasive influence.

By taking a more integrative view of health and wellness, digital health treatments may help people feel better about their bodies. According to Tylka and Wood-Barcalow (2015), a positive body image includes more than just how one feels about one's physical self; it also includes one's social connections, spirituality, and level of self-care. Similarly, according to Barker (2014), holistic health care places an emphasis on the interdependence of a person's mental, emotional, and physical health. Digital interventions can help reduce the negative effects of media-driven standards of beauty and encourage healthier self-perceptions by shifting the emphasis from superficial beauty standards to more holistic health and wellness.

Despite the impressive growth of mental health support through the Internet and apps in recent years, many of these programmes do not include components that are supported by evidence-based interventions (Palmer & Burrows 2020; Wasil et al. 2019). The sad truth is that within two weeks of using mental health applications, 96% of users stop using them, which just makes the problem worse (Baumel et al. 2019). Given these obstacles, there is a dire requirement for digital mental health treatments that combine evidence-based information and maximise the possibility that even short involvement might result in long-term, beneficial change.

The advent of digital health interventions does, however, offer new obstacles, most notably in relation to the sharing of health-related content on social media. According to Festinger (1954), women who strive to fulfil unrealistic standards may have heightened feelings of inadequacy due to the attractiveness of holistic health messages promoted by celebrities. These messages combine health ideals with appearance aspirations. Also, people may have inflated expectations and end up disappointed because the personal aspect of social media communication makes it hard to see the big picture when it comes to attaining holistic health.

In light of the growing influence of digital health treatments on how people view their health and wellness, it is critical to look for new models that take a more complex view of body image and self-esteem. The notion of body neutrality arises as an enticing paradigm change in view of the problems caused by digital media's impact and societal beauty standards. One potential way to promote holistic well-being in the digital era is through the practice of body neutrality, which involves cultivating an accepting and neutral relationship with one's body rather than aspirations centred upon one's appearance. In light of the difficulties associated with managing one's body image in the modern, media-saturated society, the investigation of body neutrality as it pertains to digital health interventions provides an authoritative and relevant discussion.

Body Neutrality in the Digital Age

"Body neutrality" is a new theory that's gaining traction in the field of self-esteem boosting. Body neutrality is a viewpoint that opposes the dominant body positivity trend; it emerged in the middle of the 2010s and has since gained support from the media (Khan 2022). Body neutrality, in contrast to body positivity, which stresses the importance of liking one's physical appearance, moves the emphasis from loving one's aesthetics to loving one's functionality (Butterfly Foundation 2023). Alleva, Tylka, and Kroon (2017) state that this involves recognising the body's abilities in areas including self-care, creativity, physical capacities, and internal processes.

Notably, functional appreciation holds that one should value one's body for what it can do rather than how it looks (Alleva & Tylka 2021). This view is consistent with body neutrality. Enhanced body satisfaction and a more positive body image may result from procedures that emphasise the usefulness of one's physical attributes. Bodily neutrality provides a sophisticated method of encouraging a positive self-image by making functional appreciation a main principle.

Concerns about body image and symptoms of eating disorders can be effectively addressed by the incorporation of body neutrality into digital health treatments. Implementing accessible interventions that adhere to the principles of body neutrality is possible due to the pervasive utilisation of digital platforms. Additionally, single-session techniques are attractive for eliminating barriers to access related to protracted treatments because they are scalable and cost-effective (Smith et al. 2023).

It is important to acknowledge that both body positivity and body neutrality have their advantages, even if the former has received more media attention (Cowles, 2022). While many people have benefited from body positivity's message of self-love and acceptance, some have argued that it fails to elevate marginalised communities since it targets only certain body types (Rodgers et al., 2022; Darwin & Miller 2021).

Incorporating concepts of body neutrality into digital health interventions offers a potential way to promote good body image and tackle related mental health issues. This intervention can help people develop a healthier and more compassionate connection with their physical selves in this digital age by moving the emphasis from how they look to how they work.

Conclusion

We have seen how body neutrality, social media, digital health, and one's perception of one's own body interact with one another throughout this conversation. We've discussed how artificial beauty standards on social media worsen body image issues. Nevertheless, we have also acknowledged the possibility of digital health treatments to lessen these impacts and encourage healthy self-perception and general wellness.

It's important to recognise social media's powerful influence on body image and use digital health tools to improve body image. By adopting body neutrality, which promotes acceptance and appreciation of the body's functionality rather than its looks, people can actively fight social media's false beauty standards.

In the end, we can build a culture that embraces diversity, encourages self-acceptance, and promotes holistic well-being despite the ever-changing influence of social media by putting an emphasis on body neutrality and making use of digital health tools.

References

Alleva, JM & Tylka, TL 2021, ‘Body functionality: a Review of the Literature’, Body Image, vol. 36, Elsevier BV, pp. 149–171.

Alleva, JM, Tylka, TL & Kroon, AM 2017, ‘The Functionality Appreciation Scale (FAS): Development and Psychometric Evaluation in U.S. Community Women and Men’, Body Image, vol. 23, Elsevier BV, pp. 28–44.

Barker, KK 2014, ‘Mindfulness meditation: Do-it-yourself Medicalization of Every Moment’, Social Science & Medicine, vol. 106, Elsevier BV, pp. 168–176.

Baumel, A, Muench, F, Edan, S & Kane, JM 2019, ‘Objective User Engagement with Mental Health Apps: Systematic Search and Panel-Based Usage Analysis’, Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 21, no. 9, JMIR Publications, p. 14567.

Buote, VM, Wilson, AE, Strahan, EJ, Gazzola, SB & Papps, F 2011, ‘Setting the bar: Divergent Sociocultural Norms for women’s and men’s Ideal Appearance in real-world Contexts’, Body Image, vol. 8, no. 4, Elsevier BV, pp. 322–334.

Butterfly Foundation 2023, ‘Body Neutrality: What Is It and Why Is It important?’, Butterfly Foundation, viewed 12 March 2024, <https://butterfly.org.au/body-neutrality-what-is-it-and-why-is-it-important/>.

Calogero, RM, Davis, WN & Thompson, J, Kevin 2005, ‘The Role of Self-Objectification in the Experience of Women with Eating Disorders’, Sex Roles, vol. 52, no. 1-2, Springer Science+Business Media, pp. 43–50.

Cohen, R, Fardouly, J, Newton-John, T & Slater, A 2019, ‘#BoPo on Instagram: an Experimental Investigation of the Effects of Viewing Body Positive Content on Young Women’s Mood and Body Image’, New Media & Society, vol. 21, no. 7, pp. 1546–1564.

Cowles, C 2022, ‘Can “Body Neutrality” Change the Way You Work Out? (Published 2022)’, The New York Times, viewed 14 March 2024, <https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/02/well/move/body-neutrality-exercise.html>.

Darwin, H & Miller, A 2021, ‘Factions, frames, and postfeminism(s) in the Body Positive Movement’, Feminist Media Studies, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 873–890.

Fardouly, J & Holland, E 2018, ‘Social Media Is Not Real life: the Effect of Attaching disclaimer-type Labels to Idealized Social Media Images on Women’s Body Image and Mood’, New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 11, pp. 4311–4328.

Fardouly, J & Vartanian, LR 2016, ‘Social Media and Body Image Concerns: Current Research and Future Directions’, Current Opinion in Psychology, vol. 9, Elsevier BV, pp. 1–5.

Festinger, L 1954, ‘A Theory of Social Comparison Processes’, Human Relations, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 117–140.

Fredrickson, BL & Roberts, T-A 1997, ‘Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks’, Psychology of Women Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 173–206.

Hill, A 2023, ‘Social Media Triggers Children to Dislike Their Own bodies, Says Study’, The Guardian, The Guardian, viewed 13 March 2024, <https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jan/01/social-media-triggers-children-to-dislike-their-own-bodies-says-study>.

Jin, SV, Muqaddam, A & Ryu, E 2019, ‘Instafamous and Social Media Influencer Marketing’, Marketing Intelligence & Planning, vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 567–579.

Khan, A 2022, ‘The “Body Neutrality” Movement Wants You to Care Less about How You Look’, Vice.com, 18 May.

Kim, HM 2021, ‘What Do Others’ Reactions to Body Posting on Instagram Tell us? the Effects of Social Media Comments on Viewers’ Body Image Perception’, New Media & Society, vol. 23, no. 12, pp. 3448–3465.

Lazuka, RF, Wick, MR, Keel, PK & Harriger, JA 2020, ‘Are We There Yet? Progress in Depicting Diverse Images of Beauty in Instagram’s Body Positivity Movement’, Body Image, vol. 34, Elsevier BV, pp. 85–93.

Monks, H, Costello, L, Dare, J & Elizabeth Reid Boyd 2020, ‘“We’re Continually Comparing Ourselves to Something”: Navigating Body Image, Media, and Social Media Ideals at the Nexus of Appearance, Health, and Wellness’, Sex Roles, vol. 84, no. 3-4, Springer Science+Business Media, pp. 221–237.

Palmer, KM & Burrows, V 2020, ‘Ethical and Safety Concerns regarding the Use of Mental Health–Related Apps in Counseling: Considerations for Counselors’, Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, vol. 6, no. 1, Springer Science+Business Media, pp. 137–150.

Rodgers, RF & Rousseau, A 2022, ‘Social Media and Body image: Modulating Effects of Social Identities and User Characteristics’, Body Image, vol. 41, Elsevier BV, pp. 284–291.

Rodgers, RF, Wertheim, EH, Paxton, SJ, Tylka, TL & Harriger, JA 2022, ‘#Bopo: Enhancing Body Image through Body Positive Social media- Evidence to Date and Research Directions’, Body Image, vol. 41, Elsevier BV, pp. 367–374.

Salomon, I & Brown, CS 2020, ‘That Selfie Becomes you: Examining Taking and Posting Selfies as Forms of self-objectification’, Media Psychology, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 847–865.

Smith, AC, Ahuvia, I, Ito, S & Schleider, JL 2023, ‘Project Body Neutrality: Piloting a Digital Single‐session Intervention for Adolescent Body Image and Depression’, International Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 56, no. 8, pp. 1461–1680.