A finance blog that aims to simplify the complicated, and to bring Bay Street and Main Street a little closer together. In this blog you will find posts on topics that include strategy, corporate finance, and value investing. About Frank: Frank Luengo is the Chief Operating Officer of Sonora Foods Ltd., a Canadian company specializing in flour and corn tortillas (Sonora Tortillas) and other Mexican and southwest ingredients used in the Canadian foodservice and retail food sectors.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

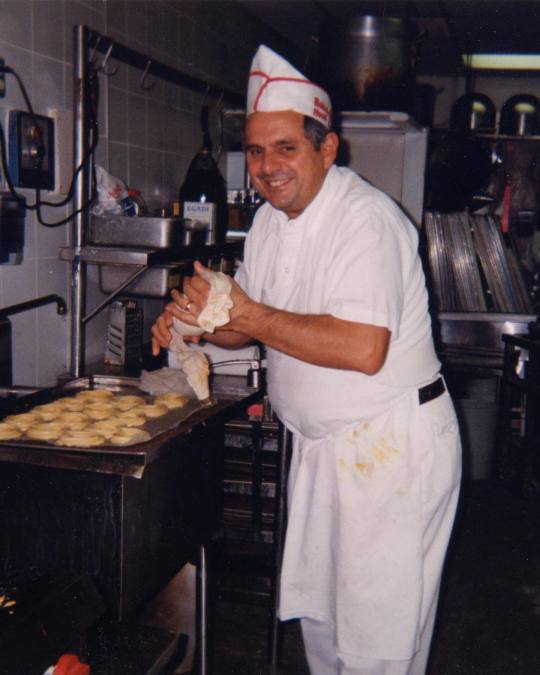

Honouring a Fellow Baker: Natale Bozzo of SanRemo Bakery

Why do we bake, or cook, or farm? Why do we get up before dawn, or work by 600 degree ovens, or in a 100 degree line kitchen? Companies love to come up with grandiose mission statements: Change the world, disrupt industries, take down the establishment. But whenever someone asks me fundamentally why we do what we do in the food industry, it’s simple. We feed people and we try to give them a great experience at the same time. There’s plenty of purpose there to go around.

No purpose has been more obvious to me, without the need for any statements, than my neighbourhood SanRemo Bakery and Cafe in Etobicoke. Go there on a Sunday morning and you’ll find crowds of people getting fresh baked bread, veal sandwiches, Italian pastries, and a little espresso to kickstart the day. It’s a magical place with great food, and the crowded market feel makes for an uplifting experience. I’m always in a great mood walking home with my loot of sandwiches and desserts. Founded in 1969 by Natale Bozzo, today SanRemo is an institution and an integral part of the Mimico and Queensway communities.

On Thursday, the Bozzo family announced on the SanRemo Bakery and Cafe’s Instagram page that Mr. Natale Bozzo had passed away after battling COVID-19 for the past 6 weeks. He was 75.

I did not know Mr. Bozzo personally, but this one hit close to home, both geographically and because baking is work that does not stop because there is a pandemic. It cannot be done remotely. Essential workers have put themselves in harm’s way throughout this pandemic and some of the hardest hit industries have been farming, food manufacturing, and distribution. For that sacrifice, and for the joy and nourishment they bring to their community, Mr. Bozo and his family have my respect.

Baking is an endeavor that is as old as farming itself. Civilizations have been built on bread. Revolutions have been fought over the people’s right to eat it. Religions view it as a metaphorical sacrament, nourishing not just the body but the soul too. Breaking bread together is making peace.

My sincere condolences go out to the Bozzo family. From one baker to another, rest in peace Mr. Natale.

*Image Credit: SanRemoBakery/Instagram

0 notes

Text

GameStop, Robinhood, and the Moral Hazard of Democratized Retail Investing

“Gamestonk!” On January 26th, 2021, Elon Musk sent out this one-word tweet. The next day, shares of GameStop doubled in value, opening at almost $279. A couple of weeks earlier, the stock was priced at around $20. Today, it is sitting at the overvalued but much diminished price of $53.

Elon, of course, was only one player in this saga. It all started with some smart quantitative analysis by members of the online reddit group WallStreetBets. Essentially, retail investor analysts discovered that hedge funds shorting GameStop (GME) shares had somehow managed to borrow more than 140% of all the shares outstanding. If this seems nonsensical, it is. How do you borrow what doesn’t exist? Also note that “naked shorting”, shorting without any of the underlying asset as collateral is illegal.

In the well documented frenzy that followed, retail investors loosely organized on social media began buying up GME and driving up the share price. This had the intended consequence of instigating margin calls for the hedge funds who had to start buying up GME shares to cover their short positions or exiting altogether. This not only created heavy losses for the hedge funds, but it created a positive feedback loop that kept driving up the price of the stock.

It also had some unintended consequences, such as the financial failure of Robinhood, a popular retail trading platform that played a central role in GME trading, which forced them to halt trading on GME and other similarly popular stocks for about 24 hours. It also exposed an ugly underbelly of no-fee or discount online trading where brokerages commonly buy or sell shares on the investor’s behalf at prices marginally higher or lower than the investor is willing to transact at and keep the difference. These types of flow-through fees are non-transparent, and create a large incentive for online brokerages to maximize trading volume at the expense of the investor.

However, this whole event was largely seen as a massive win for retail investors, many of whom bet their life’s savings on the momentum trade and made a considerable profit. Chamath Palihapitiya, the founder and CEO of Social Capital and an ex-executive at Facebook, saw this as a revolution from retail investors which gave them new agency to make or lose money on their own accord and to fight back against the financial establishment. The financial establishment, including newcomers like Robinhood, is the villain in this story, considering a history of financial profits when the economy, jobs, and families suffer and bailouts by taxpayers when the system breaks down due to the very negligence of its institutional participants.

While Chamath makes a compelling argument, I see things a little bit different. If the proponents of the WSB-GameStop chapter see this as a perfectly executed short-squeeze, I see it as the most perfectly executed pump-and-dump scheme I’ve ever heard of. You may recall one famous pump-and-dump case portrayed in the movie The Wolf of Wall Street. In the movie, the brokerage responsible for the Steve Madden IPO purchased a large block of shares of the stock to create a temporary buying trend and upward price momentum. Once a certain profit was achieved, the brokerage sold their shares, short-circuiting the price momentum and driving the shares back down. This kind of trading mechanism is illegal and one of the reasons the real-life protagonist of our movie ended up in jail.

The moral hazard of pump-and-dump schemes and hidden fees come from the inherent conflict of interest among participants who are supposed to be acting on behalf of the investor. In this case however, the perpetrator was not a hedge fund or brokerage, but the analysts and investors who created the GME frenzy to begin with (who, by the way, had no fiduciary duty to other participants). They were able to invest early, convince others to join in, and cash out at the right time. After all, GME shares were never really worth more that the $20 or so they were trading at at the beginning of the year. The company’s business model of selling consoles and video games makes it a much more likely Blockbuster Video than a Netflix.

That is, by trying to convince my neighbour that we’re both taking down the establishment and that they can have ultimate control of their financial fortunes, I am using a slight of hand to hand off my shares at an inflated price to that very neighbour and keep the profits. Thousands of proverbial neghbours undoubtedly bought into the hype when GME shares were artificially inflated at $400. Now most of them are seeing their limited wealth evaporate and many of them probably have new heavy debts to pay.

I’m not certain how this will play out from a regulatory standpoint. On one hand, freedom of information and agency suggests that retail investors should be free to get into whatever trouble they want. In fact, financial industry insiders often talk among themselves about what stocks to buy, so why not retail investors? Also, any regulations that look like they are trying to stifle retail investors and technological innovation will be met with some resistance. Certainly, something has to be done about fee transparency. And I believe something needs to be done to warn investors when they’ve left the investment room and entered the casino floor. Trader beware!

*Image: An artist's rendering of Northrop Grumman's OmegA rocket. (Image credit: Northrop Grumman)

0 notes

Text

Resilience and Combat Psychology: How Canada’s Food Sector Will Emerge From This Pandemic

As we enter the holiday season with both the incredibly positive news of new vaccines starting to be rolled out across Canada, tempered by the devastating surges in infections and hospitalizations, we find ourselves taking stock of 2020 and planning for 2021.

This week I sat with my team and reviewed our 2020 strategic plan and reflected on where we are, what progress we’ve made, and what we need to do over the next 12 months. Our dashboard had a lot of red: Revenue, profitability, cash flow, and operating metrics, all down. By any measure, 2020 has been the most challenging year in our 27-year history.

However, there were some very positive trends to carry in the new year. We improved safety and drove the transformation of a safety culture across the entire company. We met targets for new products and new retail listings. We maintained positive engagement among employees and we kept all our customer relationships as we worked together through all the challenges of regulatory changes, lockdowns, logistics disruptions, restaurant closings and openings, demand surges, and demand drops. Our operating metrics are trending positive. We are hiring and building the team again.

Throughout all of this, we’ve never stopped working the problem and working the plan. Our communication cadence has been relentless: 7:30 am daily we discuss production attainment and shipments. 9:30 am: Safety, people, production schedule. 3:30 pm: Sales outlook and progress against the day’s plan. Daily production staff standups. Weekly scorecard reviews with the management team. And so on. We just finished our last engagement survey and virtual town hall, which are critical to our ongoing conversation with all our employees.

And I think we’re not alone. The overwhelming feeling in the food industry is commitment around our shared purpose: To feed Canadians and ensure the safety and continuity of the food supply chain. It’s a sense of purpose and resilience I see across the country. Everyone has chipped in, from consumers to restaurant operators, distributors, workers, and all levels of government.

It is also, curiously, an example of a sustained combat mentality. In the face of extreme and sudden danger, we are subject to an innate and evolutionary response of fight, flight, or freeze: Our brains divert control to our limbic system, which allows us to respond quickly and instinctively to either avoid, hide from, or face danger. And while this response has successfully saved our ancestors from the metaphorical “rustling in the bushes” or attack from a predator, it comes at a very high cost. While a fight or flight response gives us a sudden rush of adrenaline and strength, it also takes away much of our dexterity, peripheral vision, and ability to think. It is well researched that in real combat situations, we must learn to face danger without giving way to our emotions and to constantly ask 3 questions: What is the threat? What are my options? What should I do? Fail to do so and you can quickly run out of options, or may fail to react at all. For businesses operating during a pandemic, this is an important concept to keep in mind.

And while it is unfortunate that we have to continue to work through this pandemic, we are fortunate to be able to do this work at all. Our customers continue open and close restaurants as needed, launch new products, simplify menus, build robust safety protocols, and communicate internally and externally to ensure continued operations.

We will eventually (hopefully soon) reach an inflection point, where the threats of infections, hospital capacity constraints, and fatalities will be overtaken by the benefits of the most massive vaccination effort of our generation. The collective fight for our lives, both literally and metaphorically, will give way to a new and cautious economic recovery where Canadians get back to work, people socialize and travel, entrepreneurs rebuild, and main street becomes strong again.

The dawn is coming. Let’s all work collectively now so that we can meet it together.

Happy holidays and may you have a prosperous and healthy 2021.

Image credit: erhui1979 | Getty Images

0 notes

Text

Freefall. Stand Up. Pivot. Walk.

Much ink will be spilled before this COVID-19 crisis is done. Pundits occupy a 24 hour news cycle with projections and daily reports of infections, fatalities, unemployment, and loss of GDP. We also hear the heartbreaking stories of healthcare workers, front-line workers, and family members of those who have died from this virus. This is the center of the crisis, around which we all have to rally. After all, those front line and healthcare workers, and those who have gotten sick are our family members, friends, and neighbours.

For my part, I would like to share with you how my industry, Canada’s foodservice sector, has experienced this crisis so far. My focus, and that of this blog, is business, economics, and investing. I feel that once we tackle the fundamental healthcare crisis we are facing, we will have to tackle a very difficult and likely protracted economic and social challenge.

Also, while the experiences of business owners and operators are very different from the more direct stories we see on the news and social media, they are also intense and highly personal. Most managers, young and old, have never experienced a crisis like this. Sure, we prepare for accidents, fires, earthquakes, terrorism, cyber attacks, and the like, but I’m sure that in most crisis plans the scenario that certain industries around the planet would be all but shut down for an indefinite period was unthinkable.

Freefall.

The story of this coronavirus started some time in December or January, depending on where you look. It evolved slowly at first, as a remote challenge across the world. But then suddenly and in waves at the beginning of March, many businesses watched in disbelief as a cascade of cancellations, closures, and states of emergency started to pour in. It escalated from calls to practice voluntary social distancing, to cancellations of sports, theaters, air travel, and festivals. In provinces across Canada this was followed by emergency declarations and shut downs of non-essential businesses.

The entire period of cancellations to shutdowns took about 10 days. This period was marked by urgent questions from managers that needed immediate answers, but answers were often not forthcoming. How long will this last? How far is the bottom? Who is going to help? What options do we have? For many business owners, especially restaurant operators, the answer was often to just shut the doors. Tragically, workers also started getting sick. Warehouses and factories struggled to secure protective equipment for their employees, and many businesses that were deemed essential (such as the food supply chain), had to implement new policies and protocols as best they could. And at every step along the way, there was a supervisor, manager, or owner that felt personally responsible for what was happening to their teams.

By the time the dust had somewhat settled, there was what I can only describe as business silence. The system had essentially shut down. Restaurants across the country shut down completely and those that could still do takeout remained open at a small fraction of where they were only a few days earlier. Factories shuttered. Warehouses sat full of product. Commerce had stopped.

Standup. Pivot.

During the freefall stage, businesses made several difficult decisions in order to keep running. Most notably, businesses laid off a record number of employees in a matter of days. During the week of March 23-27, roughly 1 million Canadians filed for unemployment. That alone is roughly 5% of our workforce. The Canadian government and Bank of Canada listened closely to industry groups and worked quickly to shore up both the financial system and social safety nets. Over the past couple of weeks the Canadian government has announced massive programs like the Canada Emergency Response Benefit and the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy. While those programs are still being rolled out as of the time of this writing, it allowed a lot of businesses to rehire employees and concentrate on getting back to work.

While the challenge of the freefall stage was understanding the threat and immediate options at our disposal, the next challenge is to define a path forward. Here we must stand up as a business. We have to establish a new communication cadence with our teams, put aside projects that are no longer relevant or possible, and define a new agenda and new projects moving forward.

There’s an adage in the foodservice industry: People have to eat. It means that while there is a lot of innovation and jostling with consumer brands and novel ways of creating, packaging, and delivering food, people need to eat. It creates a certain stability in the work we do. If we can figure out consumer trends and the needs of the supply chain, we will move forward. It felt strange then thinking, hey, here is a situation where people are just not eating, at least not in restaurants. What is the fundamental challenge and what is the opportunity?

What it really comes down to is distribution. The foodservice sector is essentially a separate distribution channel for people to get the food they want. There are manufacturers, food producers, distributors, and of course restaurants, that create an entirely separate system to feed people. This is where I am seeing lots of businesses pivoting, and fast.

Restaurants are starting to add grocery items to their menus and adding those to restaurant delivery services. Several brands have launched e-commerce initiatives. Established and other loosely formed industry groups are working together to promote food takeout in various forms. Distributors are starting to divert overstock items that happen to be in very short supply in grocery stores. Even regulatory bodies like the CFIA have provided guidance to facilitate this.

It’s important to note that these changes in business plans are not just necessary for the companies implementing them, but also for other companies that have had to pick up the slack. Grocery retail is under severe strain, and getting foodservice back up and running is an endeavour that helps everyone.

Walk.

I’m still often asked the question, when are we getting back to normal? My answer is that this is the new normal. We have to operate with this, what we have today. We also have to be open to the idea that the future will not look like the past, and that dwelling on the future return to normal can paralyze a business. Instead, we have to take stock of what we have, dust ourselves off, and begin to walk before we have an opportunity to run again. Take an opportunity to overcome adversity with your team. Figure our new products, get lean, find new forms of distribution and placement, get scrappy.

But also be realistic. Your business is smaller now. Maybe much smaller. If you and your teams can come together now, when things get better you will fly.

PS: I encourage industry insiders and consumers to rally around takeout initiatives happening in your markets. A couple that I’m aware of is #OneTable and #TakeoutDay. Become involved and help in any way you can.

About the author: Frank is the Chief Operating Officer of Sonora Foods Ltd., a Canadian company specializing in flour and corn tortillas (Sonora Tortillas) and other Mexican and southwest ingredients used in the Canadian foodservice and retail industries.

0 notes

Text

Who Pays for COVID-19?

A friend of mine put the COVID-19 pandemic in perspective for me: “Generations ago Canadians were called to war. Today, Canadians are called to stay home.”

While a much less violent call to action, there are a lot of similarities between a pandemic and war. Like in war, there will be casualties. Like in war, some volunteers such as healthcare workers will put their health and lives at risk. Like in war, societies will have to divert, or in many cases mothball, factors of production. Like a war, it will be expensive.

The focus of this war effort is clear: Mitigate casualties and avoid overwhelming the healthcare system. That is priority number 1.

The second priority for government is figuring out how much this is going to cost and how we pay for it. There are two areas of deep concern: First, we are seeing the deepest and fastest loss of jobs on record. Worse than the Great Depression. In one week between March 16-22, Canadians saw close to 1 million new applications for EI. That effectively doubled our unemployment rate. On March 26, the US reported weekly jobless claims jump to 3.28 million. These kinds of numbers mean that we are already in a deep recession and effectively this pulls the rug from under the economy. The only silver lining is that this unemployment is not caused by structural issues in the economy, but by an externality. Think of this as a worldwide hurricane disaster. This means that if we can overcome the disaster, we may be able to get confidence back more quickly than we did during the Depression.

Secondly, there are parts of the market that are disproportionately affected, and many businesses that were otherwise healthy before the pandemic will cease to exist. If this happens, you will not only have unemployment but a loss of economic output that could be felt for the next decade. These industries include tourism, restaurants, hospitality, air travel, sports, theaters, and festivals, to name a few. Such businesses in turn are supplied and serviced by a vast supply chain of distributors, manufacturers, staffing agencies, marketers, consultants, engineers, and builders. Revenues in these industries have plummeted in ways never seen before. When numbers come in, they will be grim, with revenue losses of 70%-100% for thousands of businesses during this lockdown.

Conversely, there are industries that are likely experiencing a boom. The legal field will no doubt have to provide guidance to businesses and individuals in the wake of this disaster. The grocery retail sector, including distribution and e-commerce, are overwhelmed with demand. Shelves are empty while some manufacturers and distributors ramp up capacity.

The Canadian government is undoubtedly trying to navigate this. There is a common understanding that we will have to incur debt, just like during a war, to combat this virus. However, while effort is being put forward to support unemployed workers through structural changes to our EI system, not enough is being done to make sure those workers have jobs to which they can return. Restaurants and theaters can only stay closed for so long, airplanes can only be parked for so long, before the entire supply chain starts to break down and create ripple effects.

The Canadian government did unveil a wage subsidy program of 10% over three months which will cover up to $1,375 per employee and 25,000 per employer. However, business groups have criticized this measure as the proverbial drop in the bucket. In contrast, countries like the UK and Denmark have unveiled wage subsidy programs of 75% for affected businesses. The hope is that this measure is much more effective at bootstrapping the economy after the crisis is over compared to mass unemployment and business failures.

As with previous wars, the effort must be unified across an entire nation. A crisis of this magnitude should not be a boon to some and a catastrophe to others. While we all hunker down and work through this impossible puzzle, I hope all levels of government will make the right decision to get us all back up an running as quickly as possible once this monster is slain.

0 notes

Text

The Future of “What’s for Dinner?”

I’m going to depart briefly from corporate finance and strategy posts to talk about the core of my business: food. It’s something I’m passionate about and I believe our relationship with food is about to take significant leaps forward. For Canada specifically, we are going to have to decide where we want to be in this new future: Do we want to be the provider resources and raw materials? Do we want to become low cost processors? Do we want to be brand innovators? Or do we want to be at the forefront of technologies that will define our relationship with food? You probably guessed my bias, that we need to and have an opportunity to be leaders in all of the above.

I have focused a significant amount of time over the past 6 months on food and consumer trends in the US, and I’ve come out with a view that we have a nexus of cultures, social media, technology, and health and wellness trends that are already changing and will continue to rapidly change the food industry. In February I attended the National Grocers Association show in San Diego, and last week I was in Chicago at the NPD Food Summit, where I got to hear insights and trends affecting the North American food industry.

Of particular interest to me regarding these trends is that little question my wife often asks me around 3pm on a typical weekday: “What should we make for dinner?” It’s a simple question, and one that we should be prepared for. You would think that between pantry and fridge we have our bases covered so that we don’t have to think about it, that we can just come home and throw a meal together for the whole family.

But statistically speaking, the majority of us aren’t ready. It is well documented now that most households start to make the dinner decision around 4pm. In my opinion this is for various reasons, including the fact that our days are dynamic and it’s hard to know exactly what dinner “moment” we need to have until we’re there. Sometimes we’ll need something really quick and practical and sometimes we’ll want to get involved in preparing a full meal mostly from scratch. Sometimes we’ll want a blend, where we mix wholesome, handy, and a little bit of prep to get a full dinner experience, but with less work. From a generational standpoint, we are also at different levels of expertise, with research showing that most of us learn how to cook between the ages of 25 and 35. We also tend to use recipes and to try new things. If our baby boomer parents had a go-to list of ingredients and traditional home recipes, we now have an expectation that for anything we want to eat, we can find the recipe and technique to make it ourselves or just order it online.

So what’s my answer? As you might have guessed, it depends. Most days we briefly review what ingredients we think we have at home. Do we have a protein? Veggies? Sides? We ask ourselves how we feel about cooking and how involved we want to get in the kitchen. A stressful or really busy day means we’ll want to spend less effort in the kitchen. We also gauge how likely all of our kids (we have 4 between the two of us) are going to enthusiastically eat what we make. Then we decide if we should stop at a local supermarket on the way home to buy anything we’re missing, or if we should order some UberEats, or if we should take the family out for dinner.

This is the moment that I think will continue drastically change. On the technology front companies are solving both the last mile problem and the market “pit stop” problem. Artificial intelligence is already making a huge impact. In Chicago I visited an Amazon Go store, where various sensors and artificial intelligence allow you to just walk in with your Amazon Go app, pick whatever you want from the shelves and walk out. There are no cashiers, no point of sale systems, no checkout. Try as you might to fool the system by switching your selections or putting things back in the wrong shelf, the AI will still charge you the correct amount.

youtube

Grocery delivery is getting better and faster. Most metropolitan areas now have next day grocery delivery to your door. UberEats and other meal delivery platforms provide delivery within 50 minutes. I expect this level of convenience to continue to improve.

Recipe websites, blogs, together with celebrity chefs and online media personalities are providing us with unlimited options for what to make. I’ve learned cooking techniques and different ethnic cuisines just by watching online videos and downloading the recipe. I don’t always get it right, but it gives me the freedom to experiment.

Finally, smart appliances and the internet of things (IOT) is already transforming the smart home. The first time I looked at the smart home and smart kitchen was back in 2001 during a computer science project. Back then very few technologies existed. Wireless technologies were slow, artificial intelligence was far far behind, and online shopping platforms were still in the post-bubble infancy, with no real grocery online shopping to speak of.

Today, all of these technologies are mature. It is a matter of putting them together to create a seamless “what’s for dinner?” experience. Pretty soon, next time the question comes up, an app on my phone will make a suggestion on the types of food I should consider tonight based on my cooking habits. My pantry, fridge, and freezer will keep perpetual inventory of everything I have, so that the app can improve its suggestions based on what I have at home. Based on my schedule, it may be able to guess as to my disposition and how much effort I want to expend on dinner.

Once I pick what I want to do, the app will automatically shop for the missing ingredients based on my preferred grocer and shopping habits. And by the time I come home, the ingredients will be waiting for me. The recipe I need will be pre-loaded on my tablet, and all I have to do is prepare and eat.

This future is already here. What we as Canadians need to do is decide if we want to take a leadership role and be innovators or if we’ll let this future pass us by.

0 notes

Text

Our Misguided Conversation on Universal Income

Those who know me well know I’m generally a centrist. As a business owner, I believe there’s a place for capitalism and efficient financial markets, for business-friendly regulation, and smaller government. I also believe there’s a place for a social safety net, that only by protecting the most vulnerable in society can we really thrive. I chose Canada for these reasons, because I believe this is a country where we continually strive to find this balance.

For those of you who follow technology and innovation, you know that the future of labour markets will be vastly different from today, and that even today’s labour markets are very different from 10 years ago. Technology adoption is accelerating, and while minimum wage is increasing through government policy, businesses are mitigating higher costs through automation and artificial intelligence. Pundits say the future will have plenty of jobs, but that the nature of those jobs will be vastly different from what we have learned to do until now. Future jobs will require empathy, judgement, critical thinking, and relationships among people.

This leaves us with fundamental questions about our future. As one generation adjusts to new work environments and career paths, other generations will be left behind. How do we make sure we all move forward and avoid the type of polarization in politics we are seeing in North America and Europe? How will we afford it and who is going to pay for it?

It is against this backdrop that I ponder about a yet largely untested concept: Universal Income. I say untested because we haven’t yet been able to have an honest conversation about what universal income really is and what kind of society is required to make it work. We have dabbled in it. We’ve run experiments with unclear objectives and outcomes that are widely open to interpretation.

Before I get into it, I’d like to point out that economists followed by the most ardent libertarians have been in favour of universal income or social safety nets. Both Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman have opined on the subject, with Friedman even proposing a model that could work. Fundamentally they both believed that there should be a floor (a minimum) to the level of suffering and deprivation any society should allow. Libertarians seem to forget this.

There are really two models for universal income. In one model, the government guarantees every citizen an ongoing payment if they don’t meet certain income levels. As the citizen makes more income, the guaranteed payment is clawed back. The other model is negative taxation, whereby citizens require to meet a certain income threshold in order to owe any income tax.

My preferred model is universal income through taxation, primarily because it is fairly simple to implement and we already have a system of taxation and refunds. In a 1968 interview, Friedman explained this concept (ignore, if you can, the idiot interviewing Friedman). In modern income terms, imagine a person with an income tax exemption of $20,000. That is, any person earning this amount pays zero taxes. Imagine as well, a marginal tax rate which is the same for every citizen of 50%. Friedman’s idea was that a person earning less than $20,000, say $15,000, should receive an income tax refund for the difference between their income and the tax exemption amount. In this case, the person would receive a tax refund of $2,500. A person earning $25,000 in this case, would pay a tax amount of $2,500. The reason Friedman liked this model is because it was efficient, treated everyone equally, and gave everyone the exact same incentive to make an incrementally higher income. Every extra $1 in income would result in a higher total income of $0.50.

Now, before you react with shock, remember that we are used to a concept called progressive taxes, where people in higher income brackets pay a higher percentage of income tax, presumably because they either don’t need the money or don’t deserve it as much as someone in a lower income bracket. The irony of progressive taxes and the vast network of social programs we have available today is that they often amount to a much higher tax rate to the people who they are supposed to help. In fact, many programs, such as welfare and employment insurance tax the low income earner at a rate of 100%! What is the incentive, for example, to earn a few extra bucks driving an Uber while on employment insurance if the government will just take away 100% of what you make?

This is what is fundamentally broken with current experiments or discussions on universal income. They are generally structured as an added safety net, ignoring the web of programs, administration, and bureaucracy that already exist. They also ignore the complicated tax laws and rebates used to attract votes from specific demographics during an election cycle. They ignore the immense difficulty people have today in getting out of EI, welfare, and other subsidies whey they are heavily taxed when they earn more income. In order for any universal income to work we must have an honest conversation about what it really means to treat each other equally and about how much things cost and who is going to pay for them. Ardent socialists tend to forget this.

0 notes

Text

The Unmaking of Kraft-Heinz, and That Funny Thing Called Goodwill

In a casual conversation about valuation and finding the intrinsic value of firms, a friend told me that the only value that matters is when someone writes a cheque and puts it in your pocket.

Touche.

Well, in 2015, after board and regulatory approvals, and much fanfare, Kraft and Heinz corporations merged and listed in the Nasdaq at KHC, a mega merger made possible by cheques by Berkshire Hathaway and 3G Capital. The promise: Take companies with powerful brands and lots of cash and marry them with 3G Capital’s prowess in cost cutting and zero-based budgeting. The assumption was that the new firm would continue to have very successful brands that lived indefinitely, but at a lower cost.

Investors loved the idea, and for about two years, shares of KHC went from about $80 at listing in 2015, to almost $100 in 2017. Today the stock sits at $35 after falling 27% on Friday, February 22nd. The shocking news at the investor call was a $15 billion write down of goodwill and other intangible assets related to the Kraft cheese brands, Oscar Mayer, and the Canada retail business.

But how does a balance sheet item write down relate to a sudden 27% drop in stock price? After all, earnings should be enough to give investors the data they need.

It comes down to how these balance sheet assets work.

If you ever look at a balance sheet and find goodwill or other intangible assets, they represent the excess of the purchase price of the firm over its book value when someone purchased it. That is, if a company has $10 billion in equity and a company buys it for $15 billion (I’m simplifying), you’ll see the excess $5 billion in the balance sheet as “goodwill”. For some value investors, goodwill is the exact amount someone overpaid for the firm. The fact that the “someone” was Warren Buffet makes for some very bitter irony.

Under IFRS rules, companies have to do annual tests on goodwill and other indefinite intangible assets to determine if the value of the firm is still in line with the amount originally paid. If it is determined that the future cash flows of the firm (or business unit or brand) add up to a lower value than what’s represented in the balance sheet goodwill amount, the asset needs to be impaired. This is done so that investors have a more clear view of the book value of the firm. The calculation of the impairment amount requires a new set of assumptions and forecasts which should make any investor weary. It is a sort of financial sausage making. The trouble with this exercise is that once you come up with an impairment amount, there is no money that actually has to change hands. It is therefore difficult to determine if the amount is a good indicator of the actual change in value.

In my view, the new $35 share price is a combination of two sets of opinions: First is the opinion that after adjusting the KHC aggregate future cash flows by the impairment cash flow assumption (ie: how much less cash will be received by Kraft cheese products than previously thought), investors found that the new intrinsic value of KHC is only $35. Secondly, other investors may have become concerned that the intrinsic risk of the firm, the discount that represents the likelihood that the investor will suffer a permanent loss of capital, has increased.

Whether or not this represents a deal for the value investor, or a strong signal to cut losses and run, depends on your opinion of the logic above. To what degree the loss from $100 to $35 in share price represents irrational investor fear rather than logical valuation will determine in your mind if this is a deal or not. Personally, and without trying to give you advice, it sounds like a rational acceptance of the disruption caused by new food trends and the real threat to food staples brands we previously thought would last indefinitely.

0 notes

Text

Share Buybacks Are Not What You Think

What is a share buyback, and why should you care to know?

While having my morning coffee I came across an article in the Globe and Mail written by Eric Reguly (Twitter @ereguly) which talks about the wealth effect in the US stock market caused by Trump’s tax policies and how that effect is about to run out. The article is not bad, in that it explains in layman’s terms the effect of a one-time tax windfall for companies, but it conflates economics and politics when talking about share buybacks, which he describes as a slight of hand perpetrated by large companies to artificially inflate share prices.

Sigh.

I prefer to keep economics and politics separate because, in my opinion, if you understand the former, you can make a value judgement on the latter.

My definition of a share buyback is: A transaction in which corporations execute a tax-deferred transfer of wealth to shareholders by using excess cash to reduce the number of shares outstanding (repurchase), thus increasing earnings per share. The Investopedia definition (which you can find here) is technically correct and more complete than my definition, but is introduced in such a way that perpetuates the idea of a nefarious share price manipulation by corporations. Note that any attempt by corporations to manipulate share prices is both an ethical and legal no-no, even if we cannot always catch or prosecute such behaviour. To be clear, the share price inflation caused by a share buyback is 100% transparent and legitimate and does not change in any way the fundamental value of the firm.

To help explain this, let’s use the fictitious example of ACME Corp. ACME has projected annual earnings of $1,000 for the foreseeable future, a cost of equity capital of 10%, and 100 shares outstanding. Using a simple perpetuity equation, the value of the equity of ACME Corp is:

P = D/r

1,000/0.1 = 10,000

Since ACME Corp has 100 shares outstanding, the market will value each share at $100.

Now, let’s say that ACME Corp came into a one-time tax windfall of $1,000. This means that the total value of the firm is the value of all future earning plus the $1,000, or $11,000. This assumes that ACME Corp doesn’t know where it could deploy the $1,000 in order to produce more earnings per share, so that the cash would sit idle for the foreseeable future. Under this scenario, each share of ACME Corp should be worth $110. Without doing anything, that tax windfall has increased the wealth of each shareholder.

But why?

The reason is plainly that cash is cash, and shareholders are claimants on that cash. Moreover, I assume that shareholders can see what cash is necessary and what cash is held in excess, which creates an expectation that the excess cash would be paid out as a dividend.

Following this logic, let’s say that ACME Corp doesn’t want that cash to sit around idle and it doesn’t have growth projects that will give current shareholders at least their expected 10% return on equity. It then has two options: It can pay out a $10 dividend for each share (hence the $110 expected share price above), or it can repurchase $1,000 worth of shares. In the dividend case, each shareholder would end up with $10 in cash, and their original $100 share. The repurchase option would see the firm buy back 10 shares at $100, bringing the total shares outstanding from 100 to 90. Note that the value of the firm remains the same as the annuity equation above. But this time, with only 90 shares outstanding, the market value of each share 10,000/90 or $111.

But the two outcomes are not the same, you say. The reason is that in the previous example each shareholder is responsible for $10 which have not been deployed to earn more income. If they get it as a dividend (or dividend in excess of what they currently get), they have to figure out how to reinvest it. In the latter example, those $10 went to other investors (who sold back their shares) to redeploy as they see fit. Hence it’s more valuable for ACME shareholders to get rid of undeployed cash through share buybacks.

Furthermore, if all the shareholders had to take a dividend, they might have to pay taxes on the dividend. In the buyback example, the gains of share price are unrealized until the shares are sold, therefore the shareholder enjoys a tax shield until they choose to sell their shares.

What I like about this approach is that it’s virtually frictionless, allows for efficient redeployment of cash by investors, and defers taxes until each investor chooses to sell their shares.

Back to Eric Reguly and his article, one might have a political opinion on Trump’s tax policy and the social benefit of allowing investors to redeploy that cash. However, from an economic standpoint, the use of share buybacks is a transparent, efficient, and sound way to make use of this change in tax policy.

* Image credit: https://sloanreview.mit.edu

0 notes

Text

Two Questions I Ask Myself Every Year

This week I launch our annual planning cycle, where I meet with the entire management team and we start to draw up initiatives and projects for the upcoming year. The final deliverables at the beginning of the year are 1-3-5 year goals, an operating budget, a capital expenditure budget, a set of KPIs for all managers, and a list of critical projects that we will be working on.

Oh, and I have to put it all on one page. That’s right: A strategic plan needs to be simple, clear, and easy to understand. Surely, there are sales forecasts, profit and loss statements, depreciation schedules, project estimates, and other tools that back-up the plan. But in order to get everyone on board, the message needs to be clear.

This implies that the thinking that drives the plan also needs to be clear. That’s why every year, I ask myself two simple questions in preparation*. First, I ask myself “what is the top opportunity we have in front of us?” Maybe it’s related to cost reduction and consolidation, maybe it’s growth and new markets, or maybe it’s disruption and innovation. This is not to say we only have one opportunity, but in order to provide some focus we need to concentrate on the biggest, overarching opportunity.

Secondly, I have to overcome a few challenges that come from opportunity brainstorming. It’s easy to think of a great outcome, like “reduce costs” or “gain new customers”. But it can lead to the “rose coloured glasses” problem. If the opportunities are too vague or untested, it may lead to a disengaged team. Worse, it can lead to cynicism, with leaders thinking that it’s too risky, too unrealistic, too complicated, or just not very inspiring. They may fill in the blanks with all the reasons why you can’t (or shouldn’t try to) get there.

There’s a nuance here that I’d like to point out. And I’m reminded of it through an old poem I learned in high school:

“Twixt optimist and pessimist the difference is droll. The optimist sees the doughnut. The pessimist sees the hole.” -- Oscar Wilde

To me, it’s not that optimism is better than pessimism, but rather that you are always better off by trying to get a complete and objective picture. After all, the hole is part of the doughnut, no? Just looking at opportunities is naive. Only focusing on obstacles is paralyzing. Pragmatism requires a bit of both.

This leads to my second question: What is the biggest obstacle preventing us from realizing our opportunity? This of course may lead to more than one obstacle, but I try to simplify it to as few as possible.

For example, early stage startup companies might have a great product and a few customers. Their opportunity is fast growth. Their biggest problem is capital. Growth requires cash and it’s very difficult to bootstrap fast growth. A lack of history of financial performance makes it more difficult to raise capital, and the capital that is available is likely to be very expensive. Mid-stage companies may have a similar opportunity but a different problem. They might have the ability to raise capital, but they might not have the team to execute the next phase in growth. Their biggest obstacle is attracting and retaining great talent.

Of course, you can pick one of many analysis tools to figure this out, such as Porter Five Forces, SWOT, Gap Analysis, and you can back it all up with data and market studies if you’d like. But fundamentally, you need to know what is your biggest opportunity, and what is your biggest obstacle.

If you get this far, you’ll be able to derive the same questions in context for each member of your management team. What do they see as their big opportunity and their big obstacle? How can they align that with the direction of the company?

Now, the whiteboard awaits. Wish me luck.

*Prerequisite: You know what business you’re in and have a vision for your company. If you don’t, start there, then ask yourself the above questions.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Art of Forecasting, 6 Tips to Create Awesome Forecasts

There are many things I love about my job, but the nerd in me enjoys forecasting the most. In some ways, it is equivalent to design in other fields of study. The forecast is not the main thing, it is not your actual business, but it gives you a view of how your business may perform in the future. There are a myriad of advantages to having and maintaining great forecasts, from managing cash, raising capital, evaluating projects, and financial planning. Without it, the future of your business is a set of scattered puzzle pieces, not a big picture. I am a big believer that a solid strategic plan is just not complete with great forecasting.

To be fair, forecasting is detailed work. It requires understanding how your business works, from sales to manufacturing, operations to administration. As such, it’s not for everyone. But if you want to create great forecasts, there are few things that you need to keep in mind.

Focus on the Objective First

Every part of your business can benefit from some form of planning, and planning will require some form of forecasting. Marketing, human resources, operations, manufacturing, and sales, can all set internal targets and metrics based on what the business needs to achieve. If a forecast assumes or calls for 10% sales growth, or a 1% improvement in EBITDA, or a 3% improvement in cash to sales, different departments can start to plan an implement initiatives to meet targets. Similarly, if an investor wants to know the intrinsic value of a company or project, they’ll need forward looking statements that they can rely on.

However, not every forecast answers the same question, so you have to understand exactly what you’re looking for before you start. For example, if I’m evaluating a capital project, I will look at a simple “as-is” forecast and I will overlay it with a forecast for the capital project. This gives me the intrinsic value of the project, separate from the status quo. On the other hand, tax planning may require detailed forecasting of asset depreciation and financing flows. A payroll forecast may require other forecasts as inputs, such as production, distribution, and sales forecasts.

Pick Appropriate Time Intervals

The time horizon and periodicity of a forecast is also important. Capital projects often need to be evaluated on annual periods, typically 3-5 years out, depending on the nature of the project. Working capital (cash, receivables, payables, inventory) management needs monthly forecasting and targets, typically 12 months out or current fiscal year. Sales forecasts need to take into account seasonality and the user needs to decide if a month over month forecast is more or less informative than a year over year forecast. For example, I forecast monthly top line sales as year over year, but I forecast production targets and capacity based on seasonality adjusted trends. This is because an annual growth trend might give you a great high level view, but products can change significantly from one year to the next, so a more current view is needed.

Lastly, one has to remember that the further out you look, the less information you have and the more you’re likely to be off. Do not pick a time horizon that is longer than necessary, and put less weight on it the further out you go.

Make a Model

We will sometimes see a forecast as a set of numbers on a page. That will give us the impression that each of those numbers was calculated separately and scrutinized separately. This is not so, as it would make forecasting a somewhat intractable problem. Instead, forecasts rely on models and those models rely on assumptions.

Whenever I make a forecast, I try to make sure that the model has internal consistency. When this involves financial forecasts, I also make sure that they are integrated. That is, your income statement forecast should match your balance sheet and cash flow forecast. Assumptions on capital expenditures and depreciation should match long term assets in your balance sheet. Debt financing flows should match interest and cash, to name a few. This can be done without too many assumptions if you do the following:

Use formulas that can be carried across the time horizon. If formulas need to change, your model will become overly complex.

Understand which numbers will be driven by sales, or by the size of your balance sheet, for example.

Use a plug to close your model. In financial forecasts, your balance sheet needs to, well, balance. You can and should use one variable such as cash to be dependent on the rest of your balance sheet assumptions so that your model always balances.

Make Few but Sound Assumptions

Closely related to the choice of time horizon is the choice of assumptions. It is impossible to tell the exact future of a business, and knowing that your forecast will be wrong in one way or another is a great starting assumption. Remember that you’re trying to provide guidance based on what is likely to happen, not to tell the future. But a common temptation when building a forecast is to make many assumptions over a long time horizon. This will quickly undo a forecast because it becomes indefensible. For example, is it possible that you will know the average cost of all your product inputs 10 years out, or even that you will be selling the same products as today? Will you know your general administration costs 5 years out, or your marketing budget?

It is tempting to dive into every line in your income statement and balance sheet and try to answer all questions. Instead, focus on the few assumptions that drive the model. In your income statement, focus on sales, cost of goods sold, and EBITDA to cancel out some of the noise. Make an assumption for tactical capital expenditures instead of figuring out an exact depreciation amount far into the future. Use inventory days, receivable days, and payable days for shorter balance sheet forecasts, but consolidate non-cash working capital for longer forecasts.

As a rule of thumb, if you are making more than half a dozen assumptions, consider the scope of your model or the questions you’re trying to answer. If possible, simplify the model.

Don’t Forget about the Physical World

People tend to forget this when they are working with numbers on a computer: The business is affected by the physical world. While this sounds cynical, consider these examples:

If a retail brand is expected to grow at X% per year, how many stores are opening up? Where? Does it have a physical distribution network to support sales growth?

If a resources company is going to grow, does it have a pipeline of new production sites? How much gold/oil/potash is it able to extract from its current sites?

If a car company will make more cars, what is its current capacity to do so? Will new factories be required? Are new acquisitions taking place?

So while you have have a simple assumption for growth in your forecast and model, you need to understand both the capacity of the firm and how its physical footprint matches your model.

Beware the Fly in the Ointment

Lastly, and this is very important, don’t make a technical mistake in your forecast. Don’t, as the Simpsons scientist says, forget to carry the one. Let’s say you picked the right time horizon, and you made the necessary assumptions, you also need to make sure that you can back up everything you put into your model. Make sure that your assumptions are backed by the correct data and make sure that every formula and calculation is correct.

If you forget this and someone finds an error in your forecast, it will bring into question everything else in your forecast, much like the proverbial fly in the ointment.

* Image: Getty Images.

0 notes

Text

Financing Startups - Panel Discussion with Entrepreneurs at Accelerator Guelph

It’s not easy being an entrepreneur: Big vision, high stress, no time, and little money. And it’s up to you to get it all done. If you’re past the earliest stages you have a viable product and some customers, and you have formed a small core team of like minded individuals with different skills and expertise to bring to the table.

And still you have to balance two conflicting ideas: You can solve a big problem that people need (or will need) you to solve and, the odds are stacked heavily against you. There are incumbents and other startups potentially working on the same idea. Intellectual property can be stolen. Key staff can be lost. You can run out of money and have to close your doors. But if you persevere, a big payoff. You’ve built a viable business.

The Panel

It is against this backdrop that I was able to meet with a group of bright, young agri-food entrepreneurs last week at the University of Guelph as part of Accelerator Guelph (AG) and the University of Guelph Research Innovation Office. These entrepreneurs are leaders in their fields of study, some working on bringing product designs to market and others with products already in a commercial stage. All of them had a project within the AG workshop to develop a financial plan for the next phase in their startup growth. The question that was on everyone’s mind was “how do I raise the funds to grow my business?”

To help answer that question, and others, we had three finance professionals provide their insights and tips within their respective financial fields. We had Johanna Franz from Export Development Canada (EDC) representing debt financing, Garry Chan from Maple Leaf Angels representing angel investing and equity financing, and myself providing an insider perspective on corporate financing and financial management.

The panel was structured as a conversation and question and answer format and the entrepreneurs were encouraged to gather as much information as possible for the next stage in their startups. The entrepreneurs represented a wide variety of projects ranging from food production, DNA sequencing, process engineering, 3D printing, ingredient development, and plant tissue and culture vessels for agriculture. All attendees were developing or had developed their own intellectual property.

Questions and Insights Shared

There were a variety of questions asked during the session, mostly to do with finding and securing financing. Some, for example, wanted to know what requirements must be met to raise debt financing, while others wanted more specific advice on how to approach early stage equity investors.

One of a few notable insights that the group was able to take away was the requirements one must meet to raise debt. Debt is often desirable in that it is cheaper than equity and does not dilute the existing equity in the firm. This is very important, especially in growth stages. However, low cost debt is typically only raised by those firms that can demonstrate a low enough risk for the underwriter. In the case of a traditional bank, a company must show at least two or three years of financial history and ability to make and meet forecasts. This is a high bar to meet, but if it’s met, it can allow firms access to capital at costs between prime plus 1%-3%. If the firm has a track record but is slightly more risky than what a traditional bank can absorb, companies like the EDC, a crown corporation, can provide slightly more expensive debt financing, especially if there is a significant export component to the business. The ECD tackles insurance and foreign capital issues that traditional banks and insurers might not.

The attendees also learned about different kinds of debt financing, such as short term debt against receivables or recurring Saas (software as a service) revenue, versus long term debt, secured against hard capital assets such as property, plants, and equipment. We were also able to provide some information about how debt contracts are structured, including covenants that the lender might impose on the borrower that can limit the borrower’s ability to pay bonuses and dividends, for example. Covenants are important in that they give the lender the ability to demand full and immediate repayment of their loan if the covenants are not met.

On the equity front, attendees were very interested in learning what angel investing was (as opposed to VC investing) and the process that they could follow to raise equity capital in very early stages. Here Garry provided a very concise and simple explanation of what angel investing in this context actually is:

Very early equity financing

Typically less than $150,000 per investment

Expected exits of roughly 10x of what was invested

Everyone agreed that angel investors are not necessarily angels!

Garry also provided some useful advise as to what entrepreneurs would have to demonstrate when asking for equity financing. In particular, he stressed that the entrepreneur should know three things very well:

How much money they need to raise

What problem they’re trying to solve

Why should the investor invest in them

Most importantly however, was the fact that the entrepreneur, either on their own or as part of a team must make a compelling pitch and close a deal. And while expertise in a product or market go a long way to answer the second question, sound financial planning and business analysis is needed to answer the first. A balanced pitch that shows a solid grasp of strategy, product, market, and finance also tell the investor the answer to the third.

This leads us to the last insight for the group: The need of a team. We tend to think of an entrepreneur as “one”, but in fact it can and should be a closely knit multi-disciplinary team. In preparation of a business strategy, a well formed team provides much needed perspectives, and during a pitch for financing it can show your own ability to work as part of a team, the kind of chemistry your team has, and most importantly, if you can sell.

I hope we were able to provide useful insights to these early stage companies and look forward to hearing about the next stages in their journeys.

About Accelerator Guelph

Accelerator Guelph is a new program offered by the Research Innovation Office at the University of Guelph. It is an entrepreneurship training program offered to researcher-led teams who want to explore the commercial value of their research. As the University of Guelph pipeline of start-up companies matures, we anticipate partnerships will be formed with investors and small and medium-sized companies that need to innovate to scale their businesses. We licensed the Waterloo Accelerator Centre’s program because it was designed for university based entrepreneurs. The program is divided into workshops, pitch coaching, and business plan development exercises offered in an online platform called Pathfinder that guides teams through doing a business model forecast, primary research plan and forecast development exercise.

About the Entrepreneurs

Arrell Scholar Team: Led by Amberley Ruetz and Leah Blechschmidt. Developing a shelf stable local fruit product that matches the guidelines that school lunch and snack programs must follow. (premarket)

FloNergia Team: Led by Dr. Wael Ahmed, this team wants to create a company that delivers energy efficient agri-food technology to producers. Their first product is an airlift pump that is designed to make aquaculture and aquaponics more sustainable. http://www.flonergia.com/ (in market)

Lifescanner: led by Sujeevan Ratnasingham, this team is housed in our Biodiversity Institute and sells DNA kits for home and school use as well as more complex systems that can be used by border protection agencies, wildlife enforcement officers, etc… http://lifescanner.net/ (in market)

We Vitro: Born in the lab of researcher Max Jones, this team is led by grad student Kevin Piunno. Their product is a vessel that optimizes how plant tissue cultures are grown in laboratories. (Beta testing in process.) http://www.wevitro.com

Maple Sugar Team: Led by researcher Mannick Annamalai, this start up wants to specialize in manufacturing ingredients that are healthier and more local alternatives to commonly used items. Their first product is being developed and optimized for nutrition and flavour. It will be a crystalized maple sugar product that will replace imported cane sugar and deliver the mineral and micronutrient benefits of fresh maple sap. (premarket)

Additive Manufacturing Team: From the lab of researcher Dr. Ibrahim Deiab, this team is led by John Clouthier, a PhD student in the department of engineering. This team is hoping to create a metal fabrication solution that will make if much faster for manufacturers to test new tooling quickly and inexpensively. (prototype machinery in development. Industry partners secured for beta testing)

* Image credit: https://venitism.wordpress.com/2017/05/04/agribusiness-innovation/

#createdatguelph#corporate finance#corporate financing#financial management#startups#angel investing#entrepreneur#entrepreneurship#university of guelph

0 notes

Text

Espresso Capital, Making a Case for Debt and Equity in Tech Startups

Charlie Munger, the renowned value investor and vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, used to have a tricky test for aspiring analysts that wanted to join his firm: Find the intrinsic value of an internet startup. The trick was that if the analyst came up with any value at all, they would fail the test. Charlie’s point: There is no reasonable way to determine the intrinsic value of an internet startup.

Fast forward almost two decades, an internet bubble, and a lot of evolution in the tech market place, and you have Berkshire Hathaway actively investing in tech companies. Now, to be clear, in order to attract Berkshire’s interest, you have to be an elephant, tech or not tech. It’s not surprising then, that the two tech stocks owned by Berkshire are IBM and Apple. To be fair, the basic tenet of value investing is still being followed since IBM and Apple are both companies with a demonstrated ability to generate cash in the long term, but there has definitely been a shift in how even the most conservative value investor approaches tech companies.

Banks face similar challenges. They think of companies as a set of long term assets (property, plants, and equipment), short term assets (receivables and inventory), and positive cash flows that can justify loans at low interest rates. Viewed through this lens, it’s difficult for a risk analyst at a major bank to evaluate the risk of lending money to a tech startup - companies that often have little in the way of tangible assets and are consuming, not generating, cash. The problem is not just that the risk is high, it’s that it’s also really hard to measure.

This poses an immense challenge to tech startups. Much like pharmaceutical companies, tech companies need to invest a significant amount of money in research and development and can go years with negative cash flows before making a significant profit. During this time, they need to raise capital, which, given the level of risk, comes at a great cost.

If you talk to an aspiring tech entrepreneur, they might talk about raising series A or series B venture capital, and headlines are made when the amounts raised are significant. One detail that is often missed however, is that each of these rounds of equity financing can significantly reduce both the value of the founders’ equity (dilution) as well as their ability to control the company.

Just to put things in perspective: I work for a privately held 25-year-old food manufacturing company. Our cost of equity is somewhere around 15% and our cost of debt capital is very low, comparable to an A or BBB+ corporate bond. A tech startup faces equity costs of upwards of 40% and in most instances won’t have have access to any traditional sources of debt - eg, bank debt.

This begs the question: What would happen if you could significantly lower the cost of capital for a tech startup?

I recently explored this question at a dinner with Espresso Capital a few weeks ago, where I was able to hear from Espresso’s management team as well as some Espresso clients. What I came away with was a new understanding of how growing tech companies can raise debt capital and significantly lower their cost of capital, especially during those tough early years when a company needs to invest heavily to drive growth.

Espresso Capital is a lender to tech companies. Their corporate mission is to “keep founders in control”, but practically speaking, they can lend money to revenue generating tech startups to help fund growth while decreasing their cost of capital, limiting equity dilution, and helping founders retain corporate control.

More specifically, Espresso has found a way to lend money to Software-as-a-service (Saas) companies that have stable and recurring revenues. Saas companies, instead of selling software licenses and support contracts, sell hosted software that requires monthly or annual fees instead. Think of Dropbox, Smartsheet, Shopify, Salesforce, or Hootsuite, to name a few.

While this was all an interesting concept, I tend to understand better when I see the numbers, so I decided to model two scenarios where a fictitious tech startup goes through a 5 year period with negative cash flows as it grows dramatically, followed by 5 years of positive cash flows. In one scenario, the startup has to raise all its cash shortfalls for the first five years through equity capital. In the second scenario, that same firm raises 50% of their capital through debt, and the other 50% through equity.

In each scenario, the firm had to raise similar amounts of capital and had the same cash from operations. During the first 5 years, the firm is cash flow negative, and for the subsequent 5 years, it is cash flow positive. In both scenarios, the founder injects the first $500,000 of capital. In both scenarios, the company is valued at $112 million at year 10. I assumed a 40% cost of VC equity capital and a 15% cost of debt capital. These numbers are for illustration purposes only, as both venture investors and lenders will set their own rates.

The results are striking, but not surprising. In the first scenario, the firm has equity valued at $112 million, but the founder(s) only owns $27 million, or roughly 24% of the equity. Note that this also means that the founder(s) control roughly 24% of the votes on the board. In the second scenario, the founder(s) owns 45% of the equity, or roughly $50 million. In the second scenario, I assumed that one of the positive cash flow years was used to pay off the debt. This temporarily lowered the value of the firm. A case could be made for establishing an optimal and ongoing debt to equity ratio.

This all makes for an interesting shift in how we view debt with tech startups. As with Charlie Munger and Berkshire Hathaway, banks are used to determining value (and risk) based on tried and true historical data such as revenues, earnings, and short and long term assets. Tech startups make this job notoriously difficult due to negative cash flows early on, untested revenue and earnings histories, and no long term assets. Software-as-a-service companies are helping to bridge this gap by providing steady recurring revenue streams that can serve as both collateral and forecasting tools. Lenders like Espresso are able to model risk in innovative ways and significantly lower the cost of capital for these firms. In turn, entrepreneurs have access to more financing options, can reduce their overall cost of capital, benefit from improved negotiating power with equity investors, retain greater control of their firms, and achieve higher value of equity upon exit.

The real question for me is if this model can work in the long term. There is a lot of potential, but in the past 8 years we have not experienced a shock to financial markets like we saw in 2008, or the tech bubble that popped back in 2000. On the contrary, we are currently enjoying the benefits of a sustained bull market which has helped the tech sector attract significant amounts of capital. I would be interested to see what would happen when capital for startups becomes more scarce. If it does work however, it has the potential to create a whole new face of early stage investing.

It’s an exciting market, and I can’t wait to see what’s next.

0 notes

Text

Bitcoin Freefall: A Craps Table Gone Cold

About 6 weeks ago, Bitcoin hit an important milestone: It hit the $10,000 mark. Immediately the talking heads started speculating that the sky is the limit for Bitcoin, that $10,000 is just the beginning. Stories of Bitcoin millionaires and billionaires started to pop up and suddenly Bitcoin speculative euphoria was at an all time high and Bitcoin quickly hit $19,000. If I had a dollar for every time someone said “If you had bought Bitcoin some time ago, you’d be rich today”, I’d have about $10. Ok, so that’s not very much, but you get the point.

This week, after several reports of possible government crackdowns on the cryptocurrency, fear has take over. Today, Bitcoin is well below $10,000 once again. Just to let it sink in, anyone who purchased Bitcoin at $19,000 has lost nearly 50% of the value of their investment in one month. I’m sure many of those investors bought on margin (with debt), which means they may have wiped out their entire equity.

If there is a lesson here, it’s this: Investing is a very different beast from speculating or gambling, but many people can’t tell the difference. To help, I’ll state a few characteristics of investing. Not all need to be true, but most of them should:

You are able to determine the intrinsic value of a security or asset

You assume an optimal amount of risk through diversification

You expect to get a reasonable return for the risk you are taking

You assume a long investment period (years)

You have better data than others, or can interpret the data better than others

Investors are generally divided into two groups; growth, and value. Growth investors look for assets that have greater and more rapid growth potential, while value investors look for assets that are proven and can be purchased at a discount. Regardless of which group a real investor falls into, their investment methods are likely to exhibit the characteristics stated above.

If they don’t, then they no longer fall under the category of investors. Rather, they are considered speculators. People who poured their money into the tech bubble of the late nineties, the gold rush of the 2000′s, or now Bitcoin, fall under this category. Speculating is a more viral, emotional process where people buy assets because they believe they can make a greater than reasonable return for their investment, in a short period of time, while assuming (unknowingly) a massive amount of risk.

Now, this does not mean that an investor can’t lose money, or that a speculator can’t make money. The difference is in the expectation one should have about the potential outcomes. In this sense, I like to use a casino metaphor. Every now and then you, or maybe a friend, will hear about or experience a euphoric and profitable run at the Black Jack or Craps table at the casino. This friend will inevitable tell you they had a great experience and made lots of money and whether you realize it or not, you will have a desire to try your luck at the casino yourself. The delusion does not come from the desire to play, it comes from the idea that playing at the casino is a form of investing. You wouldn’t, for example, recommend that someone go to the casino in order to make a return on their investment, because you know that the odds are not in their favour. If, on the other hand, you suggest that someone go spend their money, have a good time, and nurse their hangover the next day, then you’d at least be realistic.

Investors will disagree on the finer points of their investment strategies, the intrinsic value of assets, the economy, or even the fate of the market. However, all investors, the real ones, will have in common a long term view and a sober approach to the deployment of capital. They will exhibit the characteristics mentioned above.

Does this mean that I have a pessimistic view on Bitcoin, blockchain, or financial technology in general? No. Well, on Bitcoin, yes. I do believe that Bitcoin has no intrinsic value, and because it cannot be used to transact for goods and services and is not backed by anything, it is not a currency. To me, it is only a vehicle for speculation. However, I think blockchain is a very innovative technology and I believe that banks will eventually find a way to derive value from it. Anthony Lacavera, for example, recently announced a $10 million blockchain investment he plans to take public this year. But I argue that Anthony is investing in technology and the potential uses and value that can be created from said technology. He is not suggesting we all go blow our money at the casino.

0 notes

Text

First Mover Strategies and Network Effects

Hootsuite’s Ryan Holmes wrote an interesting piece in Betakit around the myths behind first mover advantage. His point is that there are certain advantages of being second, third, or even simultaneously developing a product or idea with other “first movers”, and that one shouldn’t be discouraged in being second-to-market. Summarized, the advantages he brings up are:

Easier to identify what you’re after (the incumbent)

Less effort developing technology

Market already has proof of concept

Availability of technologies to satisfy customer needs

While I do not disagree with his main arguments, I disagree with the framing that first mover advantage is a myth. My take on this is that you have to be clear what your strategy is, and that will dictate whether you have to be first or not. On the technology front, I have to give him full credit. Trying to go to market with bleeding edge technology is enormously difficult, expensive, and risky. Sometimes you will have success developing the technology but will suffer from lack of supporting technology or will miss what the customer needs are.