Text

Eugène Lepoittevin (1806–1870) - illustration from the series ‘Les Diables de Lithographies’, 1832

907 notes

·

View notes

Text

MAIL-COACH TIE. Two things are absolutely requisite, rather out of the common course, to form this tie, which should resemble a waterfall. In the first place, the cloth should be immensely large; in the second, it should have no starch. The tie is made by folding the cloth loosely round the neck, and fastening it with a common knot, over which the folds of the cloth should be spread, so as entirely to conceal it.

— The Whole Art of Dress! or, The Road to Elegance and Fashion (1830) (full text online)

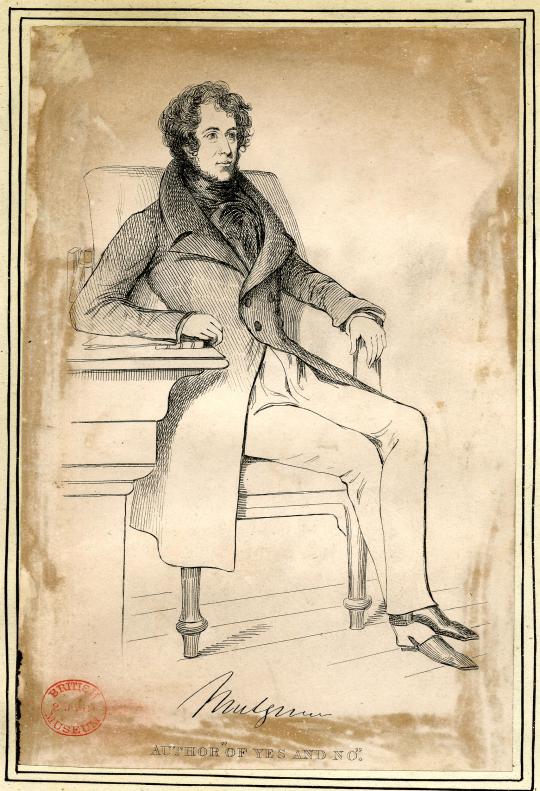

A focus on neckwear for Eighteen-Thirties Thursday: the mail-coach tie. I am indebted to Handbook of English Costume in the 19th Century for the examples of the two Men of Fashion for today's post—and both by the same artist, Daniel Maclise. Descriptions of the clothes by C. Willett and Phillis Cunnington:

Benjamin Disraeli, 1830. Morning coat, strapped pantaloons, pumps with ribbon bows. Frilled shirt with wrist ruffles and 'mailcoach' neckcloth. (National Portrait Gallery)

Henry Phipps, 1st Earl of Mulgrave, etching dated 1830-1838. Frock coat, double-breasted; strapped pantaloons; 'mail-coach' or 'waterfall' neckcloth. (British Museum)

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

(L-R) Benjamin West by John Downman; Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex by Guy Head; Mrs John Montresor by John Singleton Copley; Bertrand Barere de Vieuzac by Jean-Louis Laneuville; Jacques Louis David Self Portrait; Man attributed to Francis Alleyne; Marie-Jean Herault by Jean-Louis Laneuville; Gulian Verplanck by John Singleton Copley; General Jozef Kossakowski by Kazimierz Wojniakowski

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul Gavarni — Fashionables of 1832

508 notes

·

View notes

Text

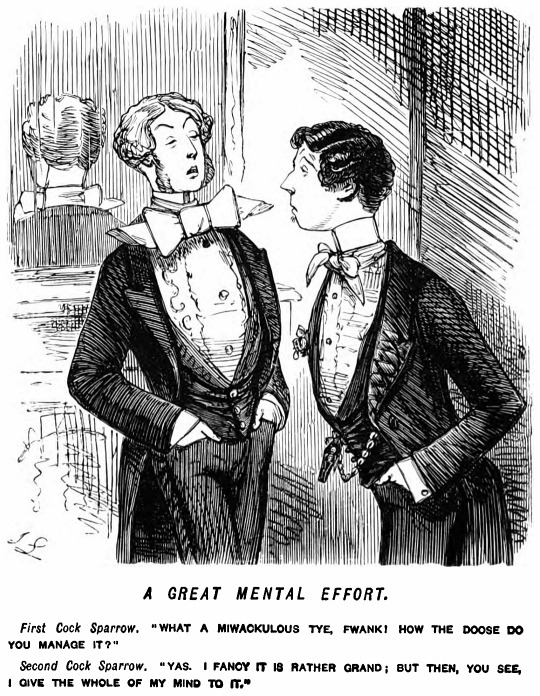

Miwackulous Tye Monday

HOW THE DOOSE DOES HE MANAGE IT ?

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm reading this history book about Victorian Era gay sailors (Unruly Desires: American Sailors and Homosexualities in the Age of Sail) and one chapter is about sailors' tattoos, and specifically ones that can be interpreted now, or were understood then, as queer tattoos. A lot of the tattoos described in the book are filthy, absolutely meant to be seen, interpreted, and enjoyed in a sexual context (which i have included under the cut). But there's also some very sweet and romantic ones. The French Victorian criminologist Alexandre Lacassagne found a few themes among the queer criminals he researched:

"Two times the interlaced hands were surmounted by initials. Below 'Friendship Unites Hearts', hands holding a pansy, over and above were initials. Hands holding a dagger with the inscription 'To Life To Death.' Four times there were initials below a flaming heart or a pansy with the word 'Friendship.' Four times there was the name of the 'friend' written out entirely. In one case it was surmounted with a portrait."

And Unruly Desire's author found other sweet ones recorded in the US Navy's Enlistment Rendezvous records of tattoos of enlisting men from the 1800s:

"The only tattoo that appeared on the body of Richard Devine, a 25 year old former barber from Aberdeen, Maryland, was a flower on his right forearm above the unexpected name of 'Jose Peralta.' William Young, from Marine City, Michigan, was more straightforward; on his right forearm appeared the declaration: 'I love Wilkerson J. Perry.'"

and now onto the debauchery:

"Perhaps the most overtly homosexual tattoo of any recruit listed in the [US Naval Enlistment] Rendezvous records could be found on Charles D. Moore, a 23 year old former bricklayer from Indiana. Moore had the words "Ticket Office" tattooed on his lower back, with a drawing of a downward pointing arrow "directly above anus." The [Tattooing Among] Prostitutes and Perverts article describes a similar decoration, an American sailor had a tattooed arrow on his back, along the spine, pointing to the anus and an accompanying inscription that said "For Men Only." Another man [...] had on his buttocks two inscriptions: "Open All Night" and "Pay as You Enter."

It should be noted that despite the provocative and explicit advertisement for his proclivities that his "Ticket Office" tattoo presented to the recruiting officers, Charles D. Moore was welcomed into the United States Navy on 29 of December 1864." - Unruly Desires

The criminologist Alexandre Lacassagne also found queer tattoos on penises, including quite a few of boots, which the men told him were related to the French phrase "Je vais te mettre ma botte au..." (basically, 'I'm going to put my boot up your ass and fuck you with it.")

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

Try Green's Dictionary of Slang, the advanced search, set up with the search terms 'meaning' and 'date in use between 1600 and 1799':

You may need a few searches of synonyms, as the entries can be a bit all over, but it's an incredible resource I wish more people knew about.

You can also search by geographical location, subculture, type of speech, origin language of word, and many more settings with the "add search term" button.

this is a weird question but I think you'd know the answer, given the word horny is at the latest from the late 19th century, how can one "translate" 'im horny' to 18th or even 17th (given how slow everything was at the time) century speech?

well if you're maybe working on writing something, i would just do the good old Thesaurus Dot Com for this one. try to find synonyms that predate "horny" and the 19th century. anyway, the problem with trying to translate a specific modern word into something in 18th century parlance is that there often isn't really an exact one for one stand-in. (just like they wouldn't call themselves terms like 'homosexual' but rather they'd use different phrases to express the same sentiment, to put it simply)

i'm afraid i don't have handy a list of words for you, but i know for a fact terms like 'making love', 'pleasing a woman/man', 'radical/unnatural vices', 'amorous', 'enflamed', 'aroused' and 'lustful' existed, as well as terms like 'defile', 'fuck' and more abstract ones like 'being pricked'. the phrase 'burn for one another', or the idea of longing and pining for another was also used. in fact they had a lot of .. wild terms .. the feel almost modern lmfao

(note, this is referring to a different hamilton. not alexander.) (source.) this passage refers explicitly to a trial for sodomy between two men, but i use it as an example of how graphic and explicit their language could actually be.

126 notes

·

View notes

Photo

To help meet the need for content related to racism, anti-racism, and Black voices, JSTOR has created free open library as a companion to the Schomburg Center’s Black Reading List.

Explore the list of more than 2k BIPOC+Q-authored resources today.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Also please enjoy these horrible hand people from another issue. Or don't. I can't make you.

This week, I've been fascinated by type specimens, issued by type manufacturers for printers to use in their publications.

I'm in the process of laying out a website for some original fiction set in the mid-19th century, and I can't believe I didn't think to look to these in the past. They're really incredible.

Often in small units that can be combined to bigger designs, I'm struck by the potential for these in the hands of digital artists. There are, of course, already plenty of such artists who have turned them into stamps or vectors for people to use, but I did not realise these were the origins.

I've made a small list of some of my favourites on archive.org here, but the linked one - MacKellar, Smiths and Jordan Co's collection from 1891 - is one of my top faves. Please enjoy.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This week, I've been fascinated by type specimens, issued by type manufacturers for printers to use in their publications.

I'm in the process of laying out a website for some original fiction set in the mid-19th century, and I can't believe I didn't think to look to these in the past. They're really incredible.

Often in small units that can be combined to bigger designs, I'm struck by the potential for these in the hands of digital artists. There are, of course, already plenty of such artists who have turned them into stamps or vectors for people to use, but I did not realise these were the origins.

I've made a small list of some of my favourites on archive.org here, but the linked one - MacKellar, Smiths and Jordan Co's collection from 1891 - is one of my top faves. Please enjoy.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Morning Calls." - Mistress of the house greeting visitor, taking a seat

If the mistress of the house is in the drawing-room when the visitor is announced, and she should so arrange her occupations as always to be found there on the afternoons when she intends being "at home" should visitors call—she would rise, come forward, and shake hands with her visitor. She would not ask her visitor to be seated, or to "take a seat," or "where she would like to sit?" or "which seat she would prefer?" &c.; but would at once sit down and expect her visitor to do the same, which, if she were well bred, she would at once do, as near to the hostess as possible.

Manners and Tone of Good Society; or Solecisms to be Avoided, A Member of the Aristocracy, c.1886 (13th edition) [x]

#author: a member of the aristocracy#publication: manners and tone of good society#etiquette#19th century#etiquette: calling cards#1800s#1880s#1886#victorian era#morning calls#etiquette: greetings#etiquette: faux pas

0 notes

Text

"Morning Calls." - "Not at home" and servants greeting visitors.

The mistress of a house should be especially careful to let her servant know, after luncheon, or before the hours of calling, whether she intends to be "at home" to visitors or not during the afternoon. "Not at home" is the understood formula expressive of not wishing to see visitors. "Not at home" is not intended to imply an untruth, but rather to signify that for some reason, or reasons, it is not desirable to see visitors; and as it would be impossible to explain to acquaintances the why and the wherefore of its being inconvenient to receive visitors, the formula of "Not at home" is all-sufficient explanation, provided always that the servant is able to give a direct answer at once of "Not at home" when the query is put to him. If, on the contrary, the servant is not sure as to whether his mistress wishes to see visitors or not, it is almost a direct offence to the lady calling if the servant hesitates as to his answer, and leaves her either sitting in her carriage or standing in the hall, while He will see if his mistress is 'at home,'" perhaps returning with the unsatisfactory answer that she is "not at home;" in which case the intimation is partly received as a personal exclusion rather than as a general exclusion of visitors. If a lady is dressing to go out when a visitor calls, the servant can mention that fact to a visitor calling, and offer to ascertain if his mistress will see the caller; and the caller would use her own discretion as to whether she will allow him to do so or not; but unless the visit is one of importance, it wold be best in such a case only to leave cards. A servant must never be permitted to say that his mistress is "engaged with a lady," or "with a gentleman," when a second visitor calls; but usher the second caller into the drawing-room, as he had previously done the first caller. He must on no account inquire as to whether his mistress will see the second caller or not. Neither must he inform the second caller as to whether any one is or is not with his mistress, as ignorant servants are too apt to do. These rules apply equally to a very small establishment, where perhaps only a parlour-maid is kept, as to an establishment where two or more men servants are kept. The etiquette as to what a servant should or should not do, is precisely the same whether the servant be a parlour-maid, a page, a footman, or a butler.

Manners and Tone of Good Society; or Solecisms to be Avoided, A Member of the Aristocracy, c.1886 (13th edition) [x] (Paragraphing added.)

#author: a member of the aristocracy#publication: manners and tone of good society#etiquette#19th century#etiquette: calling cards#1800s#1880s#1886#victorian era#morning calls#etiquette: servants#etiquette: faux pas#servants: parlour-maids#servants: pages#servants: footmen#servants: manservants#servants: butlers

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Apologies if you have answered that before, but I´m dealing with a potential etiquette conondrum for a scene set in 1899 in London. For plot reasons, I´d like to have character A sit beside character B during a dinner hosted by character B´s mother (who hopes her son will propose to character A shortly). All advice from the era I can find indicates that the host is supposed to escort the highest ranking lady to dinner - which character A isn´t and therefore I would have a plot problem- but I´m unclear on whether character B would have been considered the host in the first place, as an unmarried son still living under his widowed mother´s roof. If you could point me in the right direction with that question it would be much appreciated!

Anonymous, you are my first asker, ever, and I am equipped to answer your question at present, so I am more than happy to do so.

Let us take Manners and Tone of Good Society (c.1886, and continued being published into the 90s I believe) as our key text on this - and I see no reason why not, although I encourage a pinch of salt with this text as it was produced for a 'common' or at least middle-class audience, not for other elites. But regardless, so far I have found it accords with all my other research, so we will accept it for our purposes.

The relevant chapter, by the way, is Chapter VI, 'Dinner-Parties'. You can find it here.

You are correct that by MaToGS the host would escort the highest ranking lady to dinner, however you're in luck for reasons I will get into in a little bit.

Let us, for the sake of the exercise, call character A, 'Young Lady A'; character B, 'Young Gentleman B'; and character B's mother 'the Hostess'.

On page 61, MaToGS implies that where the hostess is a widow or 'maiden lady', 'a gentleman of the family' would then act as the host. In this case, we're assuming this is Young Gentleman B.

Young Gentleman B would be obliged to accompany the woman of the highest rank to the dining room (his mother, our Hostess, would bring up the rear with the gentleman of highest rank). At the dining table, the woman he accompanied would place herself on his right hand side. He then remains standing at his place at the bottom of the table until all the guests have taken their seats.

Seating places are pre-decided, and while the linked copy of MaToGS (second edition) says that putting a slip of paper with a guest's name upon it is 'old-fashioned' and 'never followed in good society', my version, thirteenth edition and much more likely to be closer to your era, corrects that this custom 'is now somewhat revived in good society'.

The following passage makes clear that the priority in seating guests is not precedency of rank, but rather everyone having a nice time:

Though precedency must be strictly followed in sending guests in to dinner, it may be departed from, in placing the guests at the dinner table, if by adhering strictly to the order of precedence, husbands and wives, or other relatives, would become placed in too close a proximity to one another, as it is not etiquette to place husbands and wives, side by side, neither is it desirable that a brilliant conversationalist, should be seated next to or between two dull and unappreciative persons.

Of course rank precedency should be used as a guide, and is preferable where practicable, but in your instance it seems it could be departed from for the interests of the Hostess.

So Young Gentleman B is seated at the bottom of the table, and to his right is the lady of highest rank. His mother, the Hostess, is seated opposite him at the head of the table, and to her left is the gentleman of the highest rank (I am here assured in the footnote that '"Long tables" are the most fashionable dinner-tables.' Good to know.)

Gentlemen and ladies who have gone in to dinner together are not required to converse with each other - it is purely by inclination.

Your solution would seem to be:

The Hostess has pre-decided seating and marked them with names.

Young Gentleman B is the host, and takes the lady of highest rank in to dinner; he sits at the bottom of the table, her to his right.

Young Lady A is seated as per her pre-designated spot on Young Gentleman B's left-hand side.

A brilliant conversationalist, or someone she knows, is placed to the right of the lady of highest rank to distract her.

And perhaps someone boring to Young Lady A's left to avoid distractions.

The Hostess sits at the top of the table opposite and stares expectantly at our couple wiggling her eyebrows and mouthing ask her! at Young Gentleman B.

I do recommend the linked book. It will take you through a dinner-party from top to bottom, including my favourite line in the whole thing, 'Pines are eaten with both knife and fork.' It will follow, however, here on Glossa Historica, in due time.

Good luck with your scene.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Morning Calls." - Hats, gloves, accessories and their wearing or leaving, for men.

A gentleman, when calling, as a matter of course, takes his hat in his hand with him into the drawing-room, and holds it until he has seen the mistress of the house, and shaken hands with her. He would either then place his hat on a chair or table near at hand or hold it until he took his leave, according as to whether he felt at ease or the reverse. He would not put his hat on until in the hall; as, in the house, a gentleman never puts on his hat in the presence of its mistress. To leave his hat in the hall would be considered a liberty, and in very bad taste; only the members of a family residing in the same house would leave their hats in the hall, or enter the drawing-room without their hats in their hands. The fact of hanging up the hat in the hall proves that the owner of the hat is at home there. At "at homes," small five o'clock teas, luncheons, dinners, &c., the rule is reversed, and hats are left in the hall by invited guests; the invitation constituting the difference. A gentleman would take his stick with him into the drawing room, or a small umbrella, if it answered the purpose of a stick. When gentlemen wear gloves, which in the country they seldom or never do, except when driving, and in town almost as seldom, they would draw off the right hand glove at least before entering the drawing-room; but if they preferred to remain gloved—although it is not so courteous to do so—they need offer no apology when shaking hands with the lady, or allude to their gloves in any way.

Manners and Tone of Good Society; or Solecisms to be Avoided, A Member of the Aristocracy, c.1886 (13th edition) [x] (Paragraphing added.)

Please note that this advice accords with the late part of the century, and social mores with regards to the frequency of glove wearing among men changed significantly over the period; ie. men of earlier decades wore gloves more often, and likewise following.

Also worth bearing in mind, the etiquette may have been modified for Jewish men. Yarmulke/kippah-wearing customs varied widely in the 19th century (see this great page for more) and many Jews, particularly in the emerging reform movement, seem to have not worn kippot at all, or only for religious services, but for those who did wear them, the kippot of the time were often larger than the skull-caps of today, and were not easily kept underneath a hat. According to illustrations and accounts of the time, Jewish men in Britain typically wore their top hats indoors to synagogue services.

A flow-chart for your hat quandaries follows.

#author: a member of the aristocracy#publication: manners and tone of good society#etiquette#19th century#etiquette: calling cards#1800s#1880s#1886#victorian era#morning calls#etiquette: gentlemen#etiquette: hats#etiquette: canes#etiquette: umbrellas#etiquette: gloves#etiquette: accessories#etiquette: at homes#etiquette: five o'clock teas#etiquette: luncheons#etiquette: dinners#etiquette: country#etiquette: driving#glossa diagrams#etiquette: jewish

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Morning Calls." - The proceedings of "morning calls" in full, pt.2.

Read Part 1 here.

At the drawing-room door the servant waits for a moment until the visitor has reached the landing, when she or he would say to the servant, "Mrs. A——," or "Mr. A——." [here meaning their own name; the visitor introduces themselves.] It would be very vulgar were either to say, "My name is 'Smith,'" and to omit the prefix of "Mr." or "Mrs." If the visitor calling bears the title of "Honourable," it is not mentioned by her or him to the servant when giving the name; neither is it mentioned by the servant when announcing the visitor. To be announced as "The Honourable Mrs. Smith" would be a solecism. All other titles are in force when announcing persons of rank; for instance, "Sir George Smith," "Lady Smith," "Lady Mary East;" but a Countess, or a Viscountess, in giving her name to a servant, would say, "Lady West," instead of "the Countess of West," and "Lady Smith," instead of the "Viscountess South." An Earl or Viscount would style themselves "Lord West," or "Lord South." The full title is printed on a visiting card, as has already been mentioned in the chapter on "Card-leaving." A lady or gentleman must on no account give her, or his, visiting card to the servant when the mistress of the house is at home, it would be a vulgarism to do so under ordinary circumstances. If the visitor does not give his or her name to the servant, taking it for granted that he already knows it, the servant, if he does not know it, would say to the visitor, "What name, if you please, ma'am?" and upon being told, he would open the drawing-room door without knocking. To knock at the door of a drawing-room or dining-room would be considered very vulgar, and should never be permitted. The only doors in a house at which it is proper for servants to knock before entering, are those of a bed-room or dressing-room. The servant, on opening the drawing-room door, would stand inside the doorway, but on one side. Having thrown the door wide open, he would not stand behind the door, but well into the room; facing the mistress of the house if possible, and would say, "Mrs. A——," or "Mr. A——." [i.e. the name of the visitor.] If the mistress of the house should not be in the drawing-room, the servant would say, instead of announcing the name of the visitor, "My mistress will be here directly, ma'am." He would then close the door, and the visitor would await her coming in the drawing-room. It would be ill-bred of a visitor to make any inquiries of the servant as to "how long his mistress will be," or "where she is," or "what she is doing," &c. Visitors are not expected to converse with the servants of their acquaintances on any topic whatever, and should never attempt to enter into conversation with them.

Manners and Tone of Good Society; or Solecisms to be Avoided, A Member of the Aristocracy, c.1886 (13th edition) [x] (Paragraphing and explanatory notes added.)

#author: a member of the aristocracy#publication: manners and tone of good society#etiquette#19th century#etiquette: calling cards#1800s#1880s#1886#victorian era#morning calls#etiquette: ladies#etiquette: gentlemen#etiquette: servants#etiquette: the honourable#etiquette: titled persons#etiquette: titled ladies#etiquette: titled gentlemen#etiquette: knights#etiquette: countesses#etiquette: viscountesses#etiquette: earls#etiquette: viscounts#etiquette: faux pas

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Morning Calls." - The proceedings of "morning calls" in full, pt.1.

Read Part 2 here.

When a lady calls at the house of an acquaintance—if driving—her [the woman who is calling] servant would then ask, "Is Mrs. A—— at home?" [to the servant of Mrs A.] If walking, she would ask the question herself. If the answer were in the affirmative, the servant [of Mrs A.] in reply would answer, "Yes, ma'am;" if in the negative, the answer would be, "Not at home, ma'am." Nothing further would be said by a well-mannered servant as to the whereabouts of the mistress of the house; and the lady calling must ask no questions as to when the lady, on whom she is calling, will be at home, as it is not considered good taste to cross-question servants as to their master's or mistress's movements. If "not at home," the lady would leave cards in the order as described in the chapter on "Card-leaving." If the lady of the house were "at home," the visitor would enter the house without further remark; the servant would close the door, and would then lead the way upstairs, the lady [who is calling] following the servant, not walking before him; he would walk slowly upstairs a few steps in advance of her, or of him—if the visitor were a gentleman. If the drawing-room were on the ground-floor, and the visitor were unacquainted with the house, the servant would say, "This way, if you please, ma'am," still leading the way. The servant goes before the visitor that he may show the way to the drawing-room; and, however accustomed a visitor may be to a house, it is still proper etiquette for the servant to lead the way, and announce him or her to his mistress; and this rule can on no account be dispensed with, except in the case of very near relations—mothers or sisters, for instance—or very intimate friends.

Manners and Tone of Good Society; or Solecisms to be Avoided, A Member of the Aristocracy, c.1886 (13th edition) [x] (Paragraphing and explanatory notes added.)

I have tried to make sense of the very opaque way this is written, and am open to corrections.

#author: a member of the aristocracy#publication: manners and tone of good society#etiquette#19th century#etiquette: calling cards#1800s#1880s#1886#victorian era#morning calls#etiquette: ladies#etiquette: mothers#etiquette: sisters#etiquette: friends#etiquette: servants#etiquette: driving#etiquette: gentlemen

2 notes

·

View notes