copywriting/online content/journalism tweets@logicandmagic

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

It was the same anticipation every time.

The excitement rose and rose in the final mile or so before we arrived, past the cross-roads with the big pub and bottle store, then past the big blue gum trees on the left, hiding our final destination.

I would open the car window and see if I could hear something, perhaps the howl of an engine at speed down the long back straight of our destination. Perhaps a whiff of burnt racing oil. The crackle of the pa system. All sending off that tingle of anticipation. Every single time.

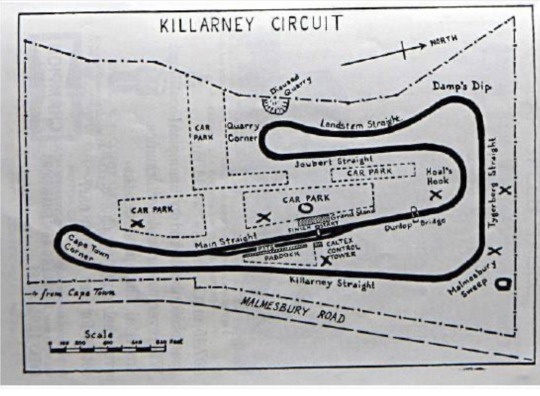

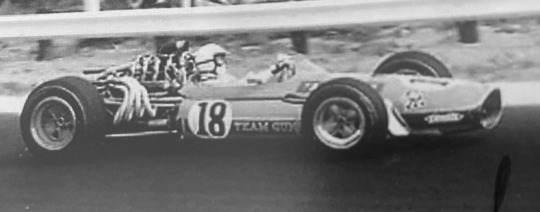

Killarney was a racing circuit built out of the sands that had once been at sea bottom when Cape Town and its surroundings had a very different shape. It was rough and ready, with minimal comforts for the spectator. But this was South Africa in the 1970s and the mostly-white spectators took care of their own comforts with braais and their own hand-built grandstands. And beer, loads of beer.

The first time I went to Killarney was with my father. He chose to stand at what I later discovered was a pretty poor viewing spot, on a straight where there was never much action. I don’t remember much about that day, just hanging on the fence watching cars and bikes whizz past in a bit of a blur, and my father mocking the accent of the commentator and his excited announcement of “here come the bikes!”

I can hear that voice today as clear as a bell and it’s probably more of a memory than any of the racing that first day.

I went back to the circuit a few times with my father, once most memorably to witness a bad crash for veteran Rhodesian driver Sam Tingle who went off into a sand-bank almost directly in front of us.

Thankfully, he had only superficial cuts and bruises, but it seemed to take forever to extract him from his F1 Brabham and I was wise enough even at that stage to know that fire was always the potential dreaded consequence of bad crashes.

The real shock came the next day when the local newspaper published a large picture of Sam trapped in the car. Even though it was in black and white, the dark splashes on his race-suit were so obviously blood that it brought the reality home.

As it said on the admission ticket: ‘Motor racing is dangeroues’, underlining that this was the most unpredictable of sports and who knew what the next incident would be. For Sam, it clearly was dangerous and unpredictable, although thankfully he was soon back competing.

Soon, I wasn’t relying on my Dad to get to Killarney any more. Together with a pal, I discovered that two buses could get me the two or so miles to that cross-roads near Killarney and then it was just a ten minute walk. That was the pattern for many of my school years until I could drive myself. These were mostly solo journeys, and to this day, it’s the way I go to events in the UK.

Of course, it’s a long way from the wind-blasted sand-basted track at the tip of Africa to the green and pleasant woodland that surrounds circuits like Brands Hatch and Oulton Park, but the anticipation is still the same. The quiet before the storm of racing. Finding the best vantage point, reading the programme.

And best of all having the knowledge that, as that commentator at Killarney also said, fifty years ago, “Anything can happen, and probably will.”

0 notes

Text

Three bites of home.

They are the holy trinity of my eating in Cape Town.

Cling peaches. Pickled fish. Koeksisters.

Until I have tasted them, I am not really home. And that was confirmed once more on a recent visit to the city of my first 31 years.

To me, they are as Cape Town as Table Mountain, Camps Bay Beach, the howling South Easterly wind, or, more recently, loadshedding (the South African euphemism for power cuts).

First, the peach.

The flesh of a cling peach does exactly that, it clings to the stone like a baboon to a towering mountainside. An orangey shade of yellow, with a silky smooth skin, they are firm to the bite, but juicey still. And they are sweet, oh so sweet, when properly ripe.

One deep bite is an instant transport back to breathless hot days sitting on hot slate next to cool swimming pools with the juice of peaches covering my hands as I took hungry bite after bite. My teenage kick.

Pickled fish is another local favourite that sings a siren song of home. Pickled is a bit of a misnomer, as it is not actually pickled, but rather the chunks of firm battered fish are sauced with a light, sweet-sour curry marinade, full of rings of onion. (See above.)

A deep local tradition as a picnic food, often connected to long Easter weekend picnic excursions to the beach, the history of pickled fish is, like many SA food traditions, a tangled one, adopted by many communities, and now an all-year-round feature on supermarket shelves and home cooking tables alike.

But for me, the true pleasure comes when the fish is all gone, and just a deep pool of the yellowy turmericy sauce and onion rings are left. Scooped up with good bread, it is the anytime-you-look-in-the-fridge snack deluxe.

The final part of this tasty tryptich is the sugar-rush to end them all: a twisted plait of deep-fried dough that drips with syrup.

‘Koeksister’ was strangely one of the nicknames I was given at school, even though I was more of a tuckshop doughnut person at the time. Maybe I was sweet and twisted, but maybe it was just a nice play on my surname.

Part of the great Afrikaans baking tradition, the koeksister apparently has its own monument in the Afrikaner community of Orania. Someone is on to something there, I think. Because when you bite into the koeksister’s collision of all the things the health police warn you against, you will understand, deeply.

So, my big three. My memory food. Still connecting taste buds to heartstrings and memory banks. Still reminding me of a time when anything seemed possible in a land that once promised so much. I will end here. After all, why spoil a memory so sweet with the sour taste of too much reality?

0 notes

Text

My Dad and Peter Stuyvesant.

The Venezia was a much-loved Italian restaurant, with the most delicious ice cream, in Sea Point, one block from my High School.

Every other Friday, I would meet my father there after school for lunch. My parents were long since divorced and these Friday lunch dates alternated with the weekends I would spend with him and his new Austrian wife.

I would order a toasted cheese and tomato, and a strawberry milkshake, he would have something more substantial, along with cigarette after cigarette. I can still smell the acrid burning of his Peter Stuyvesants, a brand named after the Dutch peg-legged former governor of colonial New Amsterdam (New York) until he lost it to the British.

The slogan for this oddly-named cigarette was ‘Your International Passport to Smoking Pleasure’. The cinema ads depicted jet-setters touching down in New York on a luxury airliner in what seemed like some weird modernisation of the governor’s original colonial conquests. For white South Africans, it all made perfect sense.

So, after my father had asked me the same questions he asked every week, ‘how was school/rugby/that friend of yours etc’, things would lapse into silence and I would watch the ash on the end of his cigarette grow longer and longer and hope it wouldn’t fall into his coffee.

His habit was to stare at any woman in the restaurant that caught his eye. He wasn’t subtle, but preferred direct and continuing eye contact until I would tell him to stop, my cheeks blushing and wishing the red leather seats would swallow me up. He would pull his gaze away, mumble something, light another Stuyvesant, and then start staring again.

My Dad was tall, thin, with prematurely grey hair, lots of it. A teenager during the war, too young to join up, his height meant he was handed white feathers when walking in town with his mother by those thinking he was shirking his duty. When he did join up, as a dispatch rider, it ended up with him crashing his bike (allegedly forced off the road by pro-Hitler Afrikaners) and spending a long time in bed with broken legs. He never talked about it. In fact, now that I come to think about it, he never talked about anything much. He was from that ‘action, not words’ generation of men, the bread-winners, the head of the family, the kings of their Castle lagers. A man of action.

He did talk a lot to people in America, though. In fact, he hardly ever stopped. He was ZS1JD, his call sign as an amateur radio operator, or a HAM, as it was known. He bought and built huge pieces of radio equipment, receivers, transmitters, amplifiers, filled with transistors and glowing globes that smelled like burnt dust when they fired up. He would have long chats about whatever men of his 30-something age talked about.

In the age before TV came to South Africa, it was a crackly confirmation that there was another world out there, maybe the same place where the men in the Peter Stuyvesant advert cavorted with young women who wouldn’t mind you staring at them one little bit, in fact, they might invite you over to their table and light your cigarette for you.

These were the days of Vietnam, the Six Day War, space walks, and moon shots, so there was always something to talk about. But really the thing they all loved to talk about was their equipment, which model of this, the performance of that, tech talk turned them on.

One part of his ‘rig’ was the outside aerial that carried their signals through the atmosphere. This was nothing subtle again. In his case, he had a 50-foot iron tower standing on a reinforced concrete base constructed in our back garden, topped with a multi-pronged horizontal aerial.

The radio tower built by a crew of black labourers with a white boss man to oversee it all. As we watched the workers in their blue overalls swarm up into the sky, finishing off this grey metal edifice, suddenly a worker fell. He landed in the deep grass, winded and groaning. After a few moments, he got up and went back to work. Shocked at the violence of his fall, I looked at my Dad for reassurance. “Don’t worry, John,” he said, “you know they don’t feel pain like us.” The trouble is, he believed it. As a seven-year-old at the time, I had no reason not to.

As a travelling commercial salesman, he travelled throughout the Western Cape, hawking watches, crockery, cutlery and jewellery to small businesses. He stayed away for a week at a time, at least twice a month. Then, it was just me and my Mom in the house, and the ‘maid’, as domestic workers were called in those days. Things were a lot more relaxed with him away. We didn’t have to wait till his car finally pulled up outside in the evenings and we could eat our supper, now with meat grey from overcooking and vegetables equally worse for wear.

I don’t remember much about those meals, eaten at the open window that looked over Table Bay, with Robben Island in the distance, with its prisoner who would eventually challenge those who thought ‘they don’t feel pain like us’. I do remember how I mixed my mashed potato together with the gem squash to make something more palatable, and the tinned guavas covered with sweet evaporated milk that would be dessert.

Some nights, after supper, he would pull on a pair of grey trousers and a black polo neck, pack his drum kit and head out to play in various jazz bands. He wasn’t bad at it, he could hold a beat, but I think the point was to get out of the house, away from my mother and I.

It was such a strong urge that not much stood in his way. One evening, he managed to drop a carving knife into his calf, a deep wound that spurted blood, quickly staining his handkerchief and first one dish towel and then another one. Clearly, this was a wound that needed stitching and some rest. But no, the show must go on, so he bandaged himself as best he could and limped out of the house Did he play that night? I don’t know, but he definitely got out of the house.

My Dad eventually left the house permanently when I was about nine, and then it was just me, my Mom, and Elsie the elderly, often tipsy, ‘maid’. She was there when I got home from school with sardines on toast, or baked beans, or toasted cheese and tomato.

I don’t think I missed him really, though I must have felt something. He was just gone, and became the Dad I would meet at Venezia every second Friday.

He stopped playing the drums from what I remember, he remarried (that lasted ten years or so), he built a large sprawling house in the Durbanville countryside, with a swimming pool and a bull terrier, and another aerial, even higher than the first one.

He still smoked Peter Stuyvesants, the butts piling up in his ashtray as he sat at his radio and called out to the world, “This is ZSIJD, how do you copy, who’s out there? This is ZS1JD.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fire. Meat. Learn. Repeat.

A recent blog from a South African friend about growing up puzzled got me thinking about food and how it can both divide and unite.

His puzzlement was triggered as a young boy when he saw bags of samp and beans in the kitchen cupboard. Samp and beans is a traditional mixture of dry ‘stamped’ corn and beans, eaten pretty much exclusively in Black households. South Africa’s polenta or tortilla, if you will, a staple cheap filling food.

Samp and beans wasn’t found in many white households those days, though now it can be bought from South Africa’s biggest up-market food supermarket. In the 70′s, the nearest thing for white communities was ‘pap’, or mieliepap, a maize porridge traditionally eaten with the traditional South African sausage, boerewors. In another culinary division, this was more likely to be found in Afrikaans white households than those speaking English.

Spool forward a few years and I’m about to have a puzzlement of my own. It’s a Friday in 1976, payday for my black co-workers in a newspaper distribution business. (It also happens to be a momentous year for the black liberation struggle, but that’s another story.)

It’s time for lunch too. Cash in pocket, what about a little TGIF luxury? Out back of the office, in the parking lot, the trio of lunchers break up some wooden fruit boxes and make a quick fire. Then, on go some cheap off-cuts of meat, straight onto the flames.

I remember being taken aback, what were they doing? Why weren’t they waiting for the fire to die down to proper cookable coals, where was the braai grid to hold the meat? It was all wrong. Too fast, too basic, too....you know, not like how ‘we’ do it.

But then someone offered me a piece of cooked meat, and my questions disappeared in a bite full of smoky, charred flavour. It was delicious. And, so I stood, in a laughing group of men, biting into cheap beef, sharing lunch with people I had never socialised with, whose homes and lives were a foreign land. Men my parents would have described as ‘boys’ and certainly not encouraged any social mixing.

Some months later, on the day I left the company, two of those men persuaded me to eat meat again, but this time from my side of the fence. So, we piled into my orange VW Beetle and headed to a famed local steakhouse.Places like this were strictly off-limits to black South Africans, as were all restaurants, bars, hotels and clubs in the so-called white areas.

So, I went inside, to order our three steak rolls. Only the best beef, of course, in a big chunky roll, wrapped in tin foil. Back in the car, we sat together, unrolled our feast, the windows fogging up from the hot food, as we wolfed down the rolls. I’m not sure who paid, probably me. Now that I think about it, definitely me.

I drove my colleagues home into the local black township, the first time I had ever set foot into their world.

We said goodbye on a street corner, and I drove home alone, back to my world of prime cuts, proper coals, and braai grids. Well-fed, and a little bit wiser.

In my life, food, in all its endless variety, has continued to be the gateway into many amazing encounters with people with whom I might normally have never spent time. Rastafarian farmers in Kenya, Bulgarian market gardeners, Italian giant garlic growers, Scottish wild salmon netters, Chinese noodle makers, and so many others.

And it continues to do so. For that, I am certainly partly in the debt of three men in a Cape Town parking lot who started a fire.

0 notes

Text

April seems so long ago.

I saw a newspaper the other day, yellowed and forlorn at the reception of the deserted five-storey City office block where I used to work. It was dated Monday 16th March. The main picture was a supermarket trolley overflowing with toilet paper. Say no more. The COVID shit, as they say, was about to hit the fan, but at least we would have the double-quilted to wipe it up.

Looking back, it was all a little giddy, exciting even, back then in the COVID Spring. At least for those spared its horrible, lung-destroying grasp.

Working from home, no problem, how novel. I made a video, full of wisecracks, it’ll be three weeks tops, then back to normal (no-one had invented the dreaded ’new normal’ yet).

Food became very, very important. Where to get it, what was available, delivery slots and bulk buys (20kg of flour, that sounds reasonable).

I worried about farmers, small food producers who had suddenly lost their market. No visitors to their farm shops, no restaurants for their produce, no customers.

I made a Face Book group to spread the word about local producers, the small businesses still making the food chain work. Not the big boys who had discovered their limitations very quickly, but the nimble people who had retooled their shops, deliveries and social media fast.

Looking back, those months from March to May seem an awful long time ago. A different decade, even. Things were deadly clear then - be afraid, stay in, and you’ll be safe. One nation under a lockdown. Do, or die.

Now, chaos reigns. Governments reel in confusion from an impossible-to-control situation. Health measures have joined the dirty Spitting Imageland of politics.

It’s every person for themselves, or so it seems. There’s a tension in the air. On the bus, down the shops. Behind our masks, we bite our lips and mutter at those who thumb their noses at social distancing.

We talked about the second wave during the first one, and now it’s here, but in a splintered, hard-to-pin-down form, in some cities, in certain towns, dodging and weaving itself to start hitting Universities, homes and hospitals again.

It’s complicated. One size of restriction doesn’t fit all.

So, what happens next? No-one is stupid enough to predict anything anymore. We might dream of a vaccine, but only an idiot (or a President) will bet their life on it.

The nights are drawing in. April seems a long, long time ago.

0 notes

Text

The hunger that goes beyond food.

Food is important.

Food is important because it drives the climate crisis. It creates both disease and, in its absence, famine. It is a market of commodities reduced to noughts and ones. It is a weapon of war, a tool of the state. It is an entertainment and a status symbol. A pillar of consumerism, and a driver of globalisation.

It has been, give or take technologies, always so.

We eat, we live. We don’t eat, we die.

But wait, it is something else.

What about its purpose as social glue, the sharing and passing around, the communal dish and the family meal, the seder and the Easter lamb, the Christmas nosh-up and the birthday bash, these have perhaps been its most powerful roles.

For we were not meant to eat alone, however much a Sainsbury’s Meal for One might try to legitimise loneliness.

And now? In this time of ‘social distancing’ it is that table hug we crave. Light a candle, throw on some clean linen, bring the soup pot to the table, rally the kids, the elders, the stranger, the friends, that is all mostly out of our reach.

Mostly, because some of us do have loved ones, flatmates, lodgers, kids and elders with us under lockdown and that is their blessing.

But many eat alone, perhaps how they have eaten for years, perhaps how they have chosen to live and eat. Some others might not have chosen that way, some might hunger for a face across the table, someone to dish up for, or to wash dishes for.

The locked-down singletons of Wuhan used food to connect with others in the same position. They shared recipes and their results, tips on how to make humble ingredients seem more noble. It was their table to sit around, their signal that you don’t have to eat alone.

Not everyone is so digital savvy or connected, so all praise to the neighbours, volunteers and services that are bringing a connection to the isolated through food or meal delivery.

No, it’s not like cooking together or eating together, but it is one little crack in this firmament of viral grey that lets in a little light. And, oh, do we not need all the light we can get right now.

0 notes

Text

Terra Madre Tales Part 1

This is my fourth visit to Turin for Terra Madre/Salone De Gusto, the biggest food gathering on the planet.

I remember my first experience in 2012 very clearly. It was very nearly my last.

For a few hours on that first day, I’d wished I was somewhere else - anywhere else, in fact.

I was leading a group of eight or so Scottish food producers to an event in Turin I knew almost nothing about. Impulsively, I had stuck my hand up in May when someone had asked for a volunteer to organise the whole shooting match. Travel, logistics, funding, everything. The most I had organised thus far was a kids’ birthday party, and even that wasn’t completely solo.

Over the next few months, I learned a lot, spent hours on the phone, emailed and emailed, and eventually thought I had it all sorted.

Then, on a lovely late-September we arrived and all seemed to be going swimmingly. All our party had arrived, two vans of fresh food (including 350 pork pies) had turned-up, what could possibly go wrong? Just one fairly major thing; the refrigerated storage for five days’ worth of perishables wasn’t booked as I thought it was. Ooops (or language a bit more colourful).

But an event as crazy as Terra Madre, drawing up to 750 000 people and organised in the main by a skeleton crew of sleep-deprived volunteers, is full of people eager to help, even if they don’t speak a word of English.

So, after two hours sitting outside in the sun feeling miserable, wishing I was somewhere else entirely, and many meetings, phone calls and special pleadings, I found myself walking wordlessly through the vast exhibitor’s hall with an Italian woman who had a big fridge for hire. The deal was done, and the food was saved.

After that, it was all, as they say, gravy. Like serving samples of organic beef, breads, fish, cheese and whisky to discerning Italians, and others from across the world, and seeing the delight on their faces. The pork pies, however, were a bit of a puzzle for most. “You eat them cold? You don’t put them in the oven?” But, in four days, they were gone, along with everything else.

I loved playing foodie matchmaker, introducing one of the UK’s most acclaimed bakers, proud of his glossy, multi-page cookbook, to an Ethiopian baker who had brought her now-wilting circle of spongy injera on a 25-hour journey from high in the mountains, along with her black and white, photocopied cookbook. Through the language of bread, they bonded in a way no other words could express.

The Scottish dairy farmer whom I introduced to his South African counterpart summed up the profound connections that happen when you throw together hundreds of food producers, activists, academics, food nerds, indigenous communities, chefs, eaters and others into a great whirling, five-day melting pot. After the two farmers spent an hour and a few beers together, my Scottish friend put it perfectly: “Different places, same shit.”

It’s that common understanding that spans the globe that reminds people that they are not some single individual ploughing their lonely furrow, often against the odds, driven by conviction, sometimes on the edge of survival, always burning with a desire to find a better way.

There is natural solidarity released when stories are shared, food is tasted, memories are created, and we go home to field, forest, kitchen, village, ocean, city or wherever we call home, with lives changed forever.

In a world that seems increasingly fragmented, events like Terra Madre have an importance that goes beyond the numbers who attend, or the tons of food tasted. It reminds us that we always have much more in common than anything that might temporarily drive us apart.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why don’t I eat KFC, even though I really, really want to?

There’s a very enticing KFC chicken poster at the bus stop I use regularly.

The deep-fried batter looks crisp and frilly, the chips alongside are golden, and the gravy rich. All for a ridiculously low price.

Every time I see that poster, a little voice in my head says: “go on, grab some, no-one will know.”

That voice has spoken maybe once a day for over two months. But I’ve never popped into the nearby KFC and handed over my £3.75.

Why don’t I? Like the little voice says, no-one need find out my dirty, little secret, and heaven forbid, it’s not as if I eat some kind of perfect, clean diet as it is.

I could point to the source of the chicken. Factory-raised in some giant, stinking barn somewhere.

I could question how any food could be so cheap. Surely, someone or something is paying the price for cheapness at the KFC counter.

I could fret about the effect on my health of high-fat, cholesterol-boosting food.

Or the impact on the planet of industrial fast food.

But come on, surely it won’t hurt to give in just once.

It’s not exactly crack. (Though the reaction to the recent KFC chicken ‘drought’ might suggest otherwise.)

I’m not going to be mugging old ladies to feed my KFC habit.

Go on, go on, go on, go on, as Mrs Doyle used to say.

The thing is, I do really love chicken.

Enough to buy a £14 Rhu Estate organic chicken from Borough Market, as I did recently, and eat from its flesh for at least five (shared) meals. (See, economical too.)

Or go to some ethical, bare-bricked cafe and pay over the odds for buttermilk-battered chicken that ticks all the righteous, sustainable boxes.

But still that KFC poster sings its siren song.

Is it just the power of advertising and branding that makes my mouth water on an icy January night? Or something else?

I can feel the pull between so many conflicting feelings, generating what seems to be like some moral choice.

My God, when did food become so difficult? When did we start seeing it as either ‘good’ or ‘bad’?

Yes, there have been media headlines about ‘food scandals’, but are we so easily spooked and thrown off kilter? Netflix might run gruesome documentaries about the horrors of hellish abattoirs. But is that it? Are we that easily corralled into a mass of neurotic eaters?

Of course, when I say ‘we’, I mean the types, the class who can afford to cut up all righteous about topside versus tofu. Not the parent choosing between heating or eating on an austerity-bombed estate. (One that’s inevitably rich in fried chicken parlours.)

Nor am I talking about a Kenyan pastoralist staring at his dying cattle as climate change starves the land of rain.

No, I mean those who can afford to choose what they eat tonight.

They’ve had a hard time recently, Trump, Brexit, Weinstein….oh dear. It’s all a bit out-of-control, however many nasty types you block online or #mettos we share. There’s too much bad in the world. Or at least that’s what we tell ourselves.

It’s so hard to be good.

Perhaps the primal act of eating is our last defiant act against a world gone mad.

My food is good, therefore I am. Or maybe that’s just battered-cod psychology.

I read a published thesis recently about why people decided to switch to vegetarianism or veganism.

What triggered it?

The interesting thing was how personal the motivations were. Only around two of the twelve interviewees even mentioned animal suffering or rights/the planet/environmentalism.

Most of the explanations were related to identity. A food choice somehow reflected who they were as people, at a much deeper level, or at a critical time in their lives.

One spoke about how a bereavement set off a change of eating choices.

What we choose to eat, or not eat, does seem to resonate on so many levels; it lays bare class, education, upbringing, income and much more.

It can bring comfort, express freedom or status, provide control, and be a strong bond with others.

Please don’t tell me “it’s just bloody food”. You’re simply not paying enough attention.

I’m reminded of that every time I wait for a bus.

Do I still stare at that poster and crave KFC? Of course, I do.

Why don’t I just go and bloody buy some, then?

What’s stopping me?

Go on then, I know what you’re thinking.

‘He’s chicken.’

1 note

·

View note

Text

An evening with Leonard Cohen.

When I told my flatmates that my first social engagement after moving to London was going to be a Leonard Cohen evening, they asked the obvious question.

What is a Leonard Cohen evening?

On the surface, it seemed a fairly simple idea: you turn up with an anecdote about your favourite ditty by the lately-lamented Mr Cohen, and after a pot-luck supper, share them.

But when I saw my girlfriend, whose invite this was, doing an hour’s web research and typing copious notes for her contribution, the whole thing took on a far more daunting quality.

I needn’t have worried really.

It was a bit like going back to school, but with most of the swats in the same class. Not that there weren’t a few dissenters, one of whom spent a great deal of the evening staring up at the ceiling, presumably hoping it would tumble down and put them out of their misery.

I was off the hook contribution-wise, since my partner had chosen a song, and provided a long and extremely detailed rationale for her choice: ‘Alexandra Leaving’. (Not Alexandra Levy, as I had misheard.)

She also assured the crowd that I had once cried when played that very song, an incident that I willed myself to remember so as to feel included.

I tried to be a smart-arse by asking what people thought Leonard Cohen’s computer password might be. I didn’t understand any of the answers, so the in-joke was on me.

The solemnity of the occasion really only lasted for the first hour, or at least until the trainee Rabbi had done her deeply-insightful, thoughtful thing.

I think it rapidly dawned on everyone that the best way to make the evening a success was to be open to angles on the Cohen oeuvre that didn’t sound like a cross between a psycho-analysis session and a Saturday morning down the funeral parlour.

There followed some great contributions.

There was at least one attempt to demonstrate a six-degrees-of-separation connection to the great man. They got within two degrees, via some distant relative of a music producer, I think.

There was many a concert anecdote. At least one contributor could have made ‘The Concerts of Leonard Cohen’ his MasterMind subject, and not dropped a point.

There was an intriguing schoolgirl romance with a teacher that played out to the background of some very raunchy Cohenian lyrics. Several of us wanted to know more than what she revealed. I could imagine more than a few people on the way home turned to their partner and said: “So she was fifteen and the teacher was twenty-four and they kissed!”

Someone with a lateral (and literary) bent read several very moving stanzas by John Donne, written on his deathbed. They showed that John Donne was a poet in a way that Lenny Baby never was.

There were numerous cover versions of Cohen classics via You Tube, and, of course there was ‘Hallelujah’, now the song that is to Leonard Cohen what the Parrot Sketch is to Monty Python.

Hailing from South Africa, where Leonard Cohen had been popular amongst sensitive youths in the 70’s, I loved the complete CD of Afrikaans cover versions. (Afrikaans being the Dutch-derived language sadly-blemished by its association with the apartheid days.) The combination of this richly-guttural language and Cohen’s lyrics is an unlikely, but successful marriage.

And then it ended, an evening devoted to a talent that continues to have a bit of a Marmite effect.

Everyone brought a dish, a song, a story, a piece of their heart and personal history. Everyone, enthusiast or ceiling gazer, made space for one another, a little silence to enjoy the songs and hear the stories they carried.

I left thinking I still didn’t like Leonard Cohen very much, but I did like the people who like him.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Christmas dinner too far.

The army is not the place to find fine food.

Maybe French recruits eat well, but not South African national servicemen in the 1970s.

It was uniformly awful, but sadly the only comfort when you were far from home and being abused by sadistic young Corporals trying to convince us we were the last bulwark of Western civilisation against the Soviet-backed forces of darkness.

The shiny silver, compartmentalised metal trays on which your food was served was called tellingly, a ‘varkpan’, or ‘pig pan’.

Every meal seemed to come with pickled beetroot, like some catering sergeant had done a crooked deal and bought up the entire stock south of the Sahara.

The coffee, served in a big metal canteen, was rumoured to contain bromide to suppress 18-year-old libidos.

Despite it all, mealtimes were bliss. The only waking respite from a thinly-moustached, pimply-faced instructor yelling obscenities so close to your face that you could tell how much beetroot he’d had for breakfast.

Later, in a smaller, more rural posting, the food improved. Most of the ingredients came direct from the local farms. The bread was fresh every day, still warm at breakfast. The milk was delivered in large metal churns, direct from the cow, utterly fresh and full-creamy. We would down pint after pint, until you had to stretch your arm right to the bottom of the churn to scoop the final drops.

Later still, the rations became a lot more meagre on four-day foot patrols into the Caprivi Strip bush, the long finger-like piece of what was then South West Africa (now Namibia), illegally occupied by South Africa.

Here, you carried and cooked all your own food. The ‘rat packs’, as combat rations were known, needed a little imagination to be edible. So, to a miniature tin of braised steak, you added another of baked beans, and if you were smart, a touch of curry powder from home. Heat that on a small square of solid fuel and life was good for the next two minutes. Especially after instant coffee sweetened with condensed milk.

You forgot you hadn’t washed for days so clothes had a white crust of dried sweat from walking 10 miles a day with a heavy pack in 35C heat, seeing no-one except the occasional elephant.

That heat also meant we all had to line up to take salt tablets to put back what the heat took out. Possibly the worst thing that has ever passed my lips (beating even pickled beetroot).

One day, we returned from a baking hot march, an exercise on which one deranged, home-sick boy had collapsed after deliberately wearing a whole extra set of clothes beneath his uniform.

As we stumbled back into our bush base, everyone was handed two ice-cold cans of fizzy drink. Slumped under the shade, I remember downing the first in a single, frantic gulp, grateful for the rush of cold liquid down my throat. I rubbed the other cold can against my burning face.

When Christmas came around, the cooks told us about the menu to be served at our remote base. A proper feast, with all the trimmings. The only snag: we’d be away on patrol, only arriving back after Christmas lunch. Rest assured they said, there’ll be plenty left over.

So, we woke on Christmas morning amongst the thorn trees and patchy scrub, deep in the uninhabited bush, away from family and the familiar. It seemed a little sad to shake hands with the rest of the patrol, wishing them Merry Christmas, but at least we had lunch to look forward to.

After a five-mile walk to the pick-up point, and an hour’s bumpy armoured truck ride back to base, we were ready to eat.

It was after three o’clock, and the place was quiet as the rest of the camp slept off their feast.

My buddy and I headed for the mess tent and set about the spread.

The cooks had been right, there was turkey, chicken, ham, stuffing and gravy, roast potatoes, cauliflower cheese, more veg, and desserts too. Christmas pudding, trifle, fruit salad, mince pies and custard and cream. And a cold beer each.

We left the tent to eat outside, each carrying a varkpan that would have done any hungry pig proud.

Snout-down, I set about it. Then, quickly hit a snag. The thing is, when you’ve been existing on meagre rations for nearly a week, your appetite adjusts, you just can’t eat as much.

I managed a few mouthfuls. Then, not another morsel. Not even, as the corpulent diner man in Monty Python’s Meaning Of Life says, a wafer-thin mint.

I could see my buddy had hit the same wall. We looked at each other, sitting in the sun, staring stupidly at mounds of delicious, uneaten food.

I’ve had a few Christmas dinners since then, mostly pretty damn good, some exceptional. But it’s that one in the Caprivi sunshine I remember most. The one I couldn’t eat.

0 notes

Text

How I learned to eat my eggs.

I hated the whites of fried eggs as a kid. I couldn’t bear the texture, the taste - for me, they were impossible to eat without retching.

I would carefully cut the offending part away and just eat the yellow centre.

That was how I ate my eggs, until my Mum went away to the hospital again and I was farmed out to family friends.

Dr Ailie Key was a single parent like my Mum, a widow. She was an orthopaedic doctor with three daughters. Her husband had died of a heart attack on the way to work at the wheel of his VW stationwagen. She was also an avid radio ham, speaking to other amateur radio operators around the world.

Ailie’s house was big and sprawling, untidy, but comfortable, with a big swimming pool out the back, just like most of the Cape Town suburbs us white kids grew up in.

My parents had been friendly with them for years, and when my Dad left and Aili’s husband died, there was solidarity between these two women holding down jobs and bringing up kids alone.

So, it was natural that when my Mum’s demons got the best of her, Ailie took me in temporarily.

I’d grown accustomed to fitting into another family’s routines and ways, since this wasn’t the first time that my mother had been treated for what she called ‘my nerves’.

I’d learned how to be a good guest, to blend in like I belonged, as if I was one of the family. It’s the kind of thing you do when you’re a confused little boy and your world gets turned upside down.

Better be on your best behaviour till the storm blows over and you get your real Mum back. Otherwise who’ll look after you?

The first morning of my stay, we sat down for breakfast before school and I did as I usually did. Ate the yolk, left the white.

Ailie asked me what was wrong. I said I didn’t like the white, thank you. Ok, she said.

But the next morning, I found out that the rules in this house were a little different. I wasn’t at home.

Before I began eating, Ailie made a suggestion. “Why don’t you cut up the yolk and the white bit, and mix it all together and eat it like that?”

Without waiting for an answer, she did it for me, knife and fork clattering as she cut and mixed.

I stared down at the plate in front of me, my breakfast now a pile of the dreaded white covered with the runny yellow yolk, all mixed together in one eggy mess. The choice was clear, it was all or nothing, no chance to be picky anymore.

Now, Dr Ailie Key was a gruff-voiced, strong person who would go to be the first woman and first African to receive the Medal of the International Medical Society of Paraplegia. She was used to dealing with the terrible, incapacitating wounds that township gangsters inflicted on their prey. One weapon of choice was a sharpened bicycle spoke that was thrust into the spine to paralyse the victim.

I wasn’t about to argue with Ailie, I wanted to stay, I wanted to be a good, little guest. No fuss, no bother.

So, I had a mouthful, and swallowed quickly, and convinced myself that I was tasting the yolk because it was all over the white and so it would be ok. And it was, and there were no leftovers that morning, or the next.

When my Mum was well enough to come home, and we were back together in our little family unit, I carried on cutting up my egg and eating the yolky mixture.

My mother made no comment on my new habit, and I didn’t say anything.

I didn’t tell her how her friend had gently persuaded me to change my ways, or how I had swallowed my fears and followed her suggestion, because deep down I was afraid of how even a tiny disobedience might mark me out as not fitting in, the cuckoo in the nest.

0 notes

Text

My ride on a garlic time machine.

Some meals stay with you. They are truly unforgettable.

Not the flashy, Michelin-starred, trend-setting meals in a restaurant. Or the odd ingredient that’s as rare as hen’s teeth.

Something far more precious. The meals that form the building blocks of your eating history, personal tastes, the deep, enduring imprints on your memory.

Every Saturday lunch, my Mum made a great big lasagne. It came to the table still bubbling like lava in a deep brown earthenware dish.

The cheese was perfectly browned on top, the béchamel sauce and meat ragu blended together into layer after layer of unctuous delight. The aroma filled our little house with the promise of the pleasure to come.

An Italian would probably have found so many things wrong with this lasagne, the pasta overcooked, and so on, but to me it was perfect.

I was back from Saturday morning school rugby or cricket, my mother was back from work, the weekend had truly begun as we sat down together.

At the time, I didn’t realise the effort that had gone into this meal. Mum worked five and a half days a week, since Dad’s alimony was tiny and irregular. Her mental health had its ups and severe downs leading to absences when she was ‘not well’.

Of course, I was oblivious to this.

All that mattered was on the plate in front of me on Saturday after Saturday.

It was so good, so rich and savoury, comforting soul food. I remember the constant struggle to slow down enough not to scald a layer inside of my mouth. A fight I often lost.

Later, living away from home, I regularly made my own lasagnes. I tried to recreate that special Saturday taste, especially the meat sauce.

Mine never quite hit the mark. Good yes, but not great like my mother’s. I quizzed her and asked for the recipe, but like so much of her cooking there was none. She just did it, she said. I continued to experiment, without ultimate success.

Then, many years later, when Mum was no longer with us, I was stirring a pan of meat sauce on the stove. It was nearly ready and I don’t know why, but I took a clove of fresh garlic and grated it into the sauce. Just one of those ‘let’s see what happens’ moments.

Like magic, the pan became a time machine. And the slivers of garlic transformed the dish to the one I remembered.

I’ve never seen the addition of freshly-grated garlic at the end of cooking mentioned in any recipe for meat ragu, and I couldn’t ask my mother if it was her secret ingredient. But really, at that moment of perfect memory, it didn’t matter one little bit.

That’s the thing about memory, it is never quite predictable - it can come crashing down on you like a wave out of a calm sea.

When those memories are good, when the smell and taste of them go to your very core, they are truly unforgettable, truly yours.

Thanks for the memories, Mum, for your days at the office, for struggling with your demons, for keeping on and on. I promise your special lasagne will live on, and so will you in a way. I’ll see to that.

0 notes

Text

The world around a fire.

You probably know the marmot as the furry star of the movie ‘Groundhog Day’. In Mongolia, they play a slightly different role when someone suggests a barbecue.

The nomadic herders of Mongolia have a very distinctive way of cooking one of these oversized ground squirrels (or a goat if it’s a big party). Essentially, it means super-heating some stones to go into the stomach of the animal to cook it from the inside, whilst a blow-torch takes care of the outside.

Not your average family barbecue.

But then, that’s the point of the recent Australian documentary ‘Barbecue’. It takes in the very many different ways that people in a dozen countries apply fire to all kinds of meat.

Smoking, searing, burying in fire pits, stuck on skewers, fired by gas, wood or charcoal, marinated, basted, rubbed, chicken, brisket, whole pigs, steaks, ribs, chops, sausages………it’s all here, a rich, delicious symphony of diversity spun around a universal theme.

No matter what their method, I felt an instant connection with these cooks. Especially when the familiar South African ‘braai’ (our term for BBQ) appeared on-screen, full of beer-fuelled, full-gutted white guys cooking coils of boerewors sausage, and entrepreneurial, black street-food braaiers serving up cheap, charred meats to passing township commuters.

This was the barbecue tradition I grew up in. And I had to grow up quickly. My Dad left us when I was ten, and so I became our household’s braaier. In the little Cape Town house I shared with my Mum and two dogs, I had a man’s job to do, and I relished very minute of the ritual.

At least once a week, I’d collect the wood on the hill above our house, stacking it in our roughly-made stone backyard barbecue, then lighting the dry leaf kindling and watching the flames build and build. Adding thicker and thicker pieces of wood till the night lit up with yellow flames.

It taught me the patience to wait for the coals to be just right, with the slightest coating of white dust, and absolutely no naked flames. The test was whether you could just about hold your hand over the fire for a second or two.

Then came the magic moment when you carefully placed the metal grid holding the meat in place at just the right height above the coals. The rising sizzle and the smell of spitting fat confirmed all was good in the world.

Just like the fire-wielding citizens of the world in the film ‘Barbecue’, even at the age of ten, I had my beliefs on the right way to get things cooked.

The best fuel was definitely rooikrans (wattle tree), or vine stumps if you were lucky, no fire lighters should be used, only one person could turn the meat, you didn’t criticise anyone’s bbq technique, and if you should need to damp down an unruly flame, it should be with beer, not mere water.

This was a very conservative world: gas-powered bbq’s were maybe ok for making camping breakfasts, women stayed mostly in the kitchen making salads, charcoal was just about acceptable if you were a bit lazy or pissed, and a half-oil barrel on four legs was a much better bbq than a fancy Weber.

There was definitely something primal about it all. Stripped-down and basic. That approach all came to a beautiful conclusion, late one summer’s day on a deserted beach near Cape Town. Friends had been diving amongst the Atlantic kelp-beds and emerged from the freezing waters with a couple of rock lobsters for supper. It was not exactly legal, though someone said it was ok to consume what you caught if it stayed on the beach.

We conjured up a quick driftwood fire, split and cleaned the lobsters and cooked them on the shell, directly on the coals.

We ate with our fingers, picking out the white, briny flesh from the tails, then breaking the legs and sucking out the elusive slivers of muscle, sweet and delicate. My idea of heaven.

I just wonder what a marmot-eating Mongolian would have thought, if he’d seen us there, down on our haunches in the warm sand by our seaside fire, all sunburned, half-naked, salt-skinned, sucking the last morsel of those crustaceans from our fingers?

We all grow up with our different traditions, especially around food. As a child you believe it's the right way, the better way, the only way. Until you slowly learn it isn't.

One man’s marmot is another’s rock lobster, you might say.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Friday night cooking lesson.

There are two ways of cooking for a group of others.

The first way is to think about your guests and what they might like to eat. Or, the other way, the school to which I belong is: ‘just cook it and they will love it’.

So, I have catered for a football team fundraiser, making mounds of tapas, and then taken home enough leftovers to feed half of Barcelona.

I have attempted to barbecue an entire, big salmon in Scottish mid-winter and landed up with half-sushi, half-smoked fish. And still my approach didn’t change. Thankfully, the results got better, and hundreds of good meals later, I knew my tagine from my taglierini, my umami from my pastrami etc etc.

But last week my cooking ego hit a wall. The occasion was a Friday night supper, the Jewish kind, for the dozen or so family members of my new girlfriend.

I was eager to cook, eager to impress – hey no problem, I know you guys don’t do pork, shellfish, no meat with dairy, that kind of thing. I’d wheel out my organic, fresh, local, Italian-influenced shtick and all would bow before kitchen genius. Glory, accolades and instant acceptance.

Not exactly.

What I began to realise was that this family had been doing Friday night suppers for a long, long time. Together.

There were unwritten rules, unspoken preferences, nods and winks and glares that went clean over my head.

They had a tradition - I had much to learn.

Plus, there were also vegetarians in the mix, and teenagers who ate like they were carbo loading for the London Marathon, and a child who only ate food that was white.

As I watched the Whatsapp messages flowing back and forth, the menu negotiated, who was bringing what, who was buying what, I slowly started to relax.

Gradually, I began to see that this meal wasn’t about the food, or religion, for that matter, it was about something else entirely.

The warmth and comfort of tradition, the bonds and responsibilities of family, compromise and reward, co-operation and care.

There is a beautiful part of the Jewish Shabbat ritual at the table before the meal, when parents bless their children, saying the kind of things every parent would, whoever their God.

May god bless you and keep you. May God show you favour and be gracious to you. May God show you kindness and grant you peace.

It is an intimate, deeply personal moment.

As I stood there, I stopped worrying that my kippah was going to fall from my head, and that I didn’t understand Hebrew. I stopped fretting about needing to dazzle them with my incredible cooking skills.

The only thing I got to cook that night was the roast potatoes. (They were well-received, obviously). It was a small contribution and a big lesson.

At some meals, the best nourishment isn’t found on a plate.

0 notes

Text

Dining out with the old man and a big fish.

In my high school years, eating out with my father was a regular Friday lunch appointment.

I would stand outside the school gates awaiting the arrival of the cream Mercedes Benz that was his transport and his office.

George Cooke was a commercial traveller, a salesman hawking around trays of watches, pens, rings, canteens of cutlery, that sort of thing. He’d go from town to town, store to store, showing off the latest and greatest stock. (Like the ‘unbreakable’ cups that cracked into pieces when he eagerly demonstrated them to my mother and myself.)

It wasn’t a glamorous life, so when he entered a restaurant with me in tow, maybe he felt like someone just a little bit special as the owner or maitre’d greeted him like a long-lost brother.

The truth was, we had probably been to that same restaurant the previous week, and the one before that…

The thing is my Dad would settle on one restaurant and go no-where else for months. Eating pretty much the same dish, at the same table, at least two or three times a week.

“The best food in Cape Town!”, he would tell anyone who cared to listen about his latest find.

Then, with predictable regularity, that particular love affair would be over. It was never clear why they fell out: simple boredom, not enough attention, who knows what would break the spell. But the next week, when the Mercedes arrived, we would be off to dine at his latest new love.

Of course, it did mean that I got to sample a fair number of restaurants, and bask in Dad’s favoured status glory whilst it lasted, and we were shown to ‘his’ table.

Honestly, as long as the establishment did a decent toasted cheese sandwich, I was a pretty happy 14-year-old. At that stage, the food was not so important.

But then one day, something happened in Mario’s Ristorante in Green Point. It was a stinking hot Cape Town summer’s day. The kind of hot that comes radiating up from the pavements, bouncing off the walls, burning down from a pale blue sky, inescapable.

Inside Mario’s, everything was cool, the curtains closed against the heat, the standing electric fans swishing back and forth, offering blessed relief.

Slowly, our sweat dried as we sucked on ice-cold cokes and waited to order.

This was the first place where I had encountered the ‘special of the day’, those secret choices that could not be found on the menu. Mario Marzagalli always delivered the description of whatever it was that day, in enthusiastic, accented detail.

On that Friday, it was the perfect dish for the inferno from which we had just escaped. Cold stock-fish.

I can still see that whole, huge cod on a silver platter. The theatre of Mario’s fork and spoon skilfully removing the grey skin, easing firm, white flesh from bones and placing my portion neatly on my waiting plate. Then the perfect taste of it too, clean and delicate, and cool, so cool.

After Mario had left my Dad and I to our fish, I began to feel different. It felt that I had somehow graduated from a world of toasted cheese sandwiches, milk shakes and ice cream. I was now part of a whole new world of grown-ups, Dad’s world, off-the-menu world. It felt very good.

Sadly, Mario died not too long after that searing February day. His wife Pina continued to run the restaurant faithfully in his spirit (and still does so today). The food remained freshly-cooked, delicious and with a homely touch that the best Italian food seems to have at its heart.

I continued to be a regular customer at Mario’s, with friends, work colleagues, girlfriends and, eventually, my own family. The daily specials continued too, but somehow cold stock-fish was never one of them.

Somehow, I didn’t mind that at all. The thing about special moments is that they can’t be repeated, and it’s foolish to try.

0 notes

Text

Growing up, throwing up and learning to love food.

My restaurant eating history didn’t get off to a good start.

My parents loved to dine out with only-child-me along for the evening.

There was one slight problem. My 10-year-old only-child digestion didn’t like this arrangement. Not one little bit.

After a couple of bites, whatever I ordered (or rather had been ordered for me) soon returned to spoil the evening.

I reckoned I must have thrown up in most of the restaurants in Cape Town’s Atlantic suburb of Sea Point.

Italian, steak house, café, posh hotel, it made no difference.

No doubt, my mother was getting a little sick of escorting me to the toilet by the time the umpteenth eruption happened in a rather nice trattoria with a prophetic mural of Vesuvius on the wall. (It was still there when I checked a year ago.)

After the Italian restaurant’s long, highly- polished corridor had been thoroughly retched over, the owner suggested “why not try a nice omelette?”

Bravo, no more quick exits with my hand to my mouth. Just a safe, warm and satisfying plain envelope of well-cooked egg. I don’t think anyone suggested a filling. Too much like playing with a loaded revolver in a small, crowded room.

It must have been a real relief for my parents. Nothing spoils your spaghetti bolognaise or T-bone steak like a sick-reeking, small child blubbing away at your table.

I have absolutely no idea why restaurants made me throw up with such desperate, violent regularity. I had no obvious allergies (hay-fever doesn’t really count). I wasn’t always ordering the same thing, and I had no problem eating just about anything that my mother cooked up.

Perhaps it was all too much of an occasion. The lowered lights, the Sinatra on the soundtrack, the waiters in their starched whites, all that jazz. I did at the same time find it impossible to sit through the American road safety films we were shown at junior school, and must be the first person to demand to be taken out, all-trembling in terror, from a matinee screening of The Sound of Music, that well-known horror film.

Oh well, that was then, thankfully. Many, many omelettes later, I grew to love restaurants more and more, and so did my digestion. My father, now divorced, used to meet me every single Friday after school to go to whichever eating place he favoured that month.

We would sit awkwardly, mostly in silence, as I would tuck into a toasted cheese (no tomato) sandwich, with a strawberry milkshake, and he would light another cigarette.

It was a nice moment, one that we repeated for years. I figured he had forgotten and forgiven me for spoiling those early nights out with my technicolour yawns.

I certainly hope so, but even then, did I see detect a tiny glance of concern as I took my first bite of my sandwich? And just a hint of relief when it stayed down?

My restaurant eating history has clocked up many a meal since those Fridays with my father. But whatever exotic dish is placed before me now, the wisdom of that Italian restaurant owner still rings true. Sometimes, a simple omelette is all you need.

0 notes

Text

Lark’s tongues with chips, please.

I continue to be amazed at our ability to make choices that hurt us. And I don’t just mean voting for Trump or Brexit.

I’m thinking more about what we put in our mouths.

You’ve probably seen the torrent of diet books, the eating rules, the trends, no this, no that, only this, only that.

You can’t ignore the rise of the gluten-free juggernaut, the clean-eating evangelists, vegetarianism and veganism, locavores and fussyvores, gut gurus, paleomeisters, fasters and detoxers.

Sip that beef broth, cut those carbs...choose what’s right for you and only you, because you’re special – so very special you have to have a special diet.

It’s a jungle out there about something essentially simple. Eating food.

Not surprisingly, there has been a backlash against the faddish and the fake, most recently in the form of The Angry Chef, a book by chef and biochemistry graduate Anthony Warner. His fury, in some cases utterly justified, is directed against the charlatans and quacks who peddle a wholly unscientific route to health, happiness, inner peace, a great night’s rest, firm stools, bright eyes and whatever else they can dream up.

In most cases, the prescriptions of these latter-day snake oil salesperson share certain similarities.

One, the limiting of some ingredients because they are ‘bad’, and the exultations of others as ‘good’. Beyond this introduction of a twisted morality, losing weight seems universally agreed to be a sign of improving health. And, hey ho, whichever food excluding plan you do choose, chances are there will always be some weight loss in the very short term. Hooray, success! Look, it worked for me the convert will confirm ad infinitum.

A scientific thrashing of the deeply dodgy and the proper recognition of what is an actual medical condition (and what is not) is not all this book seems to be about.

For me, the book vibrates with the sheer power of our relationship with food and what seems like our insatiable need to define it, frame it, control it. Until food, in its turn, defines, controls and frames us.

There seems so little room for pleasure and conviviality. Food beyond fuel or virtue signalling, beyond Instagram, food porn, restaurant bagging and gastronomic decadence, yes, even beyond science occasionally.

Instead, we so often seem to slump back to the same inability to make good choices. In this, is food merely one arena for this tendency to shoot ourselves in the foot (or mouth)?

One theory is that we are now prone to trusting the self-proclaimed expert, corporation or political leader because there is simply too much we don’t, or can’t, understand anymore.

Ever since our technology evolved beyond axe and spear, we’ve gradually out-sourced so many decisions because we’ve outsourced our understanding of a world that’s simply too hard for any one individual to comprehend.

Add to that the human need to go along with the crowd, and it’s easy to see that going out on a limb and having a minority opinion is highly unlikely.

So, if there’s a clean-skinned, glowing young person preaching the consumption of obscure ingredients in implausible combinations with seemingly desirable outcomes, some otherwise intelligent people will follow, RT and eat accordingly. Or, if it’s a supermarket with food that is cheap and plentiful, and usually safe - well, they’ll set the agenda too.

For me, life is self-evidently, beautifully diverse and complex, and all the better for it. Only a Brexiteer or Trumpeteer would deny that.

Food is the same. It is simply more interesting and rewarding if we don’t make it dance to some health or ideological narrow-minded, single-note dirge.

Eat and drink merrily and widely. Let there be joy, let there be sensuality, let there be freedom, adventure and exploration, comfort and guilty pleasures, and plenty of veg. And if it’s all in some kind of balance, all the better for our bodies and minds.

Right, who’s having the lark’s tongues with chips?

0 notes