Text

Backblog #18 - Suishou no Dragon (FDS)

Because it is a pre-Final Fantasy SquareSoft title, I had a feeling that this next game I played, Suishou no Dragon (or Crystal Dragon in the English fan translation) would be rough. Turns out I was right. It was developed by Square and published under their Disk Original Group (DOG) imprint for the Famicom Disk System on December 15, 1986. It was never released in English, of course, since there was never a non-Japanese equivalent of the Famicom Disk System at all, but I was able to play it in English courtesy of Mute’s translation patch. It is a science fiction-themed visual novel; visual novels being the genre that Square got its start with, with The Death Trap as their first game in late 1984.

The story of the game is very simple for a visual novel and I’m assuming there has to be some more context given in the manual (which I wasn’t able to find any scans of) since the game starts you off in the middle of the action and never really fully tells you what’s going on. The notes that came with the fan translation establish that you are searching for your two friends, whose interstellar shuttle has mysteriously disappeared. While searching for them, you are ambushed by a space dragon (which is where the game picks up) and rescued by a mysterious woman named Jean. You spend the game traveling between a few different planets searching for your friends. It’s an extremely short and bare-bones story, almost feeling like they established the framework for a story and never really filled it out with anything substantial. You can see everything the game has to offer in terms of its script inside of an hour. It’s honestly pretty bad.

More than any of the other games I’ve played so far, this one makes use of a point-and-click interface. All of the commands (look, talk, use, etc.) are executed based on the position of your cursor on the screen. The commands themselves are toggled by holding the B button and using the D-pad. It’s a bit clunky but not nearly as unintuitive as the controls for the move command. When you select move you can toggle between different destinations represented as arrows on the screen. You’re actually meant to press B to cycle through these, but when I first started the game and was trying to figure the controls out, I thought that maybe you need to hold B and use the D-pad (since the D-pad by itself does nothing). And this does actually visually cycle between the different destinations but does not actually select them, leading to a confusing moment where I thought both exits from one of the early areas led to the same place.

As I stated above, the game is very short and it seems like the strategy Square used to pad out the length is a couple of maze sections (one when navigating the depths of space and one when navigating Alias’s desert moon). But they aren’t real mazes like the ones in Portopia or Princess Tomato. It’s more like a series of screens that look exactly the same that give you three directions to go in. Since you can’t really tell where you are or where you’re supposed to be going, you just kind of have to bumble around until you find your destination. The closest thing it really has to tough puzzles is a sequence where if you do anything but use your gun on a character, they immediately kill you. But you can continue again from right outside the room where that takes place so it’s no big deal anyway.

The character designs of the game were actually done by none other than Sunrise (known for Gundam, Cowboy Bebop, etc.) and they look fine for the most part. The character portraits are the only thing in the game that look halfway decent. All of the background art, which is what you’re looking at for most of the game, looks very crude. The only character graphics which I don’t like at all are Jean’s, which have an atrocious white and bright teal color palette. The game has only minimal sound effects and only one song that plays during the title screen. The sole piece of music in the game is actually pretty good though, one of Nobuo Uematsu’s earliest music credits.

So, obviously I don’t care for this game very much. But it’s just because there’s nothing to it. It offers nothing substantial in terms of story, characters, gameplay, graphics, sound, or anything else. Hell, I barely have anything to say about it at all. But it’s short and it’s one of Square’s earliest games, so maybe it’s interesting as an oddity? I dunno, but next time I’ll be playing something with much more meat to it, mostly because it’s actually a compilation including six different games - Jake Hunter Detective Story: Memories of the Past. Until then, take it easy~

#text post#backblog#backlog#backloggery#video games#suishou no dragon#crystal dragon#squaresoft#disk original group#nintendo entertainment system#famicom#famicom disk system#adventure#visual novel

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Backblog #17 - J.B. Harold Murder Club (TCD)

After Princess Tomato, I decided to play J.B. Harold Murder Club, a game that I knew pretty much nothing about and kind of added on a whim. It was developed by Riverhillsoft, former members of which went on to form Level-5 and Cing (who ended up making their own series of mystery games: the Kyle Hyde series). It was originally self-published by them in August of 1986 for the NEC PC-88 and various other Japanese PCs. This was then followed by a number of other ports published by various parties, including SETA Corporation for the Famicom, Broderbund for MS-DOS, Hudson Soft for the TurboGrafx-CD, and eventually FonFun for the Nintendo DS and Mebius for the Nintendo Switch as full remakes. It is a mystery visual novel, similar in a lot of ways to Portopia. It is also known for its localization. Even many of the Japanese releases (starting with the DX release for the Sharp X68000) have dual-language options which can be switched on the fly, but only the MS-DOS and TurboGrafx-CD versions were actually released in English-speaking territories. The TurboGrafx-CD version is the version I played.

The setup of the game is a simple murder mystery: Bill Robbins, a wealthy businessman in the town of Liberty, was found dead of multiple stab wounds to the back and it’s up to J.B. Harold to bring the perpetrator of this brutal crime to justice. The manual provides a bit more context, adding that it was Jad Gregory, a retired detective who acted as J.B.’s mentor, who asked him to take the case. The game itself cold opens into a protracted noir-soaked opening set to some sexy sax music then plays some narration providing the details of the murder and pretty much throws you into the deep end. There’s not even a title screen really, which is pretty strange. Every time you boot up the game, you need to skip the opening cutscene, after which you’ll be in a new game. And from there you go into the options screen and load your save file. You also need to turn on the voice acting from here every time, since it’s off by default and the option does not save.

The majority of the game is spent traveling the city and interviewing the many, many people that are connected to the murder, many of which are Bill’s extended family and friends. You can ask them about their personal details (name, occupation, blood type, alibi, etc.), their relationship with any of the other characters you know of, and about any other miscellaneous topics you’ve learned about, such as other crimes that have taken place. Eventually, you’ll learn something through these interviews, such as that a character was sighted near the murder site near the time of the murder, that will justify a search warrant, which you need to request from the prosecutor’s office. This will allow you to actually find evidence in the various locations which may allow you to request an arrest warrant. And once you start making arrests and further pressing people in the interrogation room, you gain even more information and are able to start the cycle all over again until you are able to finally piece together who the true culprit behind the murder is.

It’s an extremely open-ended game, almost to the point of seeming structure-less. Unlike in Portopia, where you can go pretty much anywhere from the start but are kept steered in the right direction by events that occur at the police station, everything in Murder Club comes down to the player’s own intuition. At no point after learning a piece of information during an interview does J.B. narrate to himself that this makes such-and-such seem suspicious enough to justify a search or anything like that, you the player have to reach that conclusion on your own. This is both good and bad. It makes the game very difficult without brute forcing it (ask everyone about everything then request search/arrest warrants for everything, rinse, repeat). The analysis and investigation screens (accessed from the options menu in the police station) provide some automated notes: a character relationship chart and metrics on how much evidence, information, etc. you have (as well as a vague hint from Jad Gregory) respectively, but they’re not really helpful.

But on the flip-side, the lack of feedback from J.B. as a character or from the game at all makes it feel somewhat empty. The majority of the game is spent interviewing suspects, but because J.B. lacks any dialogue of his own and you’re just hearing a one-sided conversation, it feels a bit dull, like you might as well just be reading their LinkedIn profiles or something. It really feels like it would benefit from some dialogue to characterize J.B. or at least an intermediary character who is with you throughout the game, adding a bit of flavor, like Yasu or Percy from Portopia and Princess Tomato respectively. The fact that they give him a name and establish that this is his first case (as if setting up that this is the prologue to the career of a legendary detective) rather than just having him be a nameless detective for the player to project onto (like Boss in Portopia) and then having him act like a blank slate anyway seems weird.

It’s a shame, because despite the somewhat flawed execution, the twists and turns and ultimate conclusion of the case are very good. It’s a classic example of a murder mystery going deep enough to become tangled in another unsolved mystery which must also be solved to bring both cases to a close (think the DL-6 Incident in Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney). Of course, this conspiracy involves the titular Murder Club. While the game is difficult, its title provides a bit of meta-knowledge that gives the player sort of an artificial lead early on. Anytime a character mentioned that they were a part of some strange club I had never heard of, I immediately became suspicious of that. But I’m sure the writers accounted for this, since there are multiple suspicious sounding clubs like this in the game, only one of which is the Murder Club.

Unfortunately, the graphics and sound of the game (at least this version) also leave a bit to be desired. The majority of the graphics in the game resemble digitized photographs of the various locations and characters you meet, with the only outlier being the map of the city which resembles a map in a strategy game more than anything. The photorealistic look is an obvious choice to make, since the game is going for a more serious noir feel, but the TurboGrafx doesn’t really have the color depth to do this justice, so the character portraits often end up looking somewhat washed out and bland.

The game has three CD audio music tracks: "Quivive” which plays during the opening, “Gimlet” which plays on the options menu, and “The Long Good-Bye” which plays during the end credits. All three of these songs are pretty good and wholly appropriate for the genre, with “Quivive” sounding exactly as moody as a noir game needs to and “Gimlet” resembling lounge music. However, the majority of the time you’ll be hearing the various PSG tracks played elsewhere in the game, which get pretty repetitive. The voice acting, on the other hand, isn’t half bad, especially for the time. In 1991, the game was light years ahead of some of its peers in this regard.

Ultimately, while I did enjoy the narrative that this game laid out and the challenge it presented, I felt myself wanting to know more about this J.B. Harold guy, since the game is named after him after all. But really, it’s pointless to wonder about how the game would be if it were written in a completely different manner. I just wish some of the later versions, like the ones for the DS and Switch, were released here, since the audiovisual presentation of those looks much better from what I’ve seen. Unfortunately, because the English release of this game was on the TurboGrafx-CD and the English release of its sequel, Manhattan Requiem, was on the Pioneer LaserActive, the series was doomed to obscurity in the West. So, this will probably be the last I see of old J.B. Harold. Next time, I’ll be covering Squaresoft’s Crystal Dragon. Until then, take it easy~

#text post#backblog#backlog#backloggery#video games#j.b. harold#j.b. harold no jikenbo#j.b. harold murder club#murder club#riverhillsoft#hudson soft#turbografx-cd#pc engine#adventure#visual novel

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Backblog #16 - Princess Tomato in the Salad Kingdom (NES)

The game I played immediately after Portopia was Princess Tomato in the Salad Kingdom. Developed and published by Hudson Soft in July of 1984, a little over a year after Portopia, it was originally released for various Japanese PCs before being ported to the Famicom in 1988, which itself got an English release for the NES in 1991. The NES/Famicom version which I played is really almost a completely different game compared to the PC versions, featuring completely redrawn graphics and over twice the amount of chapters. The Famicom version later received a straight port to the GBA in 2005 as a part of the Hudson Best Collection Vol. 4: Nazotoki Collection, which includes a couple of puzzle games, Nuts & Milk and Binary Land, as well (Nazotoki means to solve a mystery or riddle). There was also a mobile version released in 2004 with further improved graphics. I don’t know much else about it beyond that, but I imagine it probably plays the same as the Famicom version.

The story of the game goes that, one day in the Salad Kingdom (which is, uh... mostly inhabited by anthropomorphic fruits and vegetables), Minister Pumpkin betrayed King Broccoli, kidnapping his daughter, Princess Tomato, and stealing the Turnip Emblem, which gives the right to rule. He then retreated to his castle in the Zucchini Mountains and sent out his farmies (human farmers who eat vegetables, which of course makes them the bad guys) to terrorize the citizens. It’s up to you, Sir Cucumber, the bravest knight in the land to rescue Princess Tomato and restore peace to the land. Along to help you is Percy, a young persimmon who you help in the first chapter and becomes your squire, essentially fulfilling the some of the same role as Yasu in Portopia by acting as your narrator and sometimes giving you advice.

You spend the game traveling from location to location, gathering clues and talking to various cute and wacky characters. Structurally, the game is a lot more linear than Portopia, being divided into nine chapters (or four in the PC versions). It’s a much longer game too, but thankfully there’s a password system you can use to resume your progress from the beginning of whichever chapter you last reached. Each chapter takes you to a different location in the Salad Kingdom, from the Celery Forest to the capital city of Saladoria to the resistance base (where you meet Princess Tomato’s sister, who is a regular human for some reason) and eventually to Minister Pumpkin’s castle itself where you finally meet the princess and have a showdown with the villain.

Obviously, it’s a very lighthearted and cutesy game, especially in the Famicom version, which probably contributed to its success with a female audience in Japan (I remember Arino mentioning a few female celebrities that considered this game a favorite of their childhood in the game’s GameCenter CX episode). It’s also a pretty humorous game, with a few gags that actually made me laugh out loud. While Sir Cucumber acts as the silent protagonist, Percy actually has a fairly fleshed out personality thanks to all of his dialogue over the course of the game, coming across as a bit cowardly. There’s also a gameplay purpose he serves at the end of every chapter where he gets rid of all the items in your inventory that are no longer necessary. But because of the way its presented, usually as him losing the items, it makes him seem like a bit of a fuck up.

The game itself plays very similarly to Portopia, seeming to wear the influence on its sleeve in a couple of ways. The original PC versions, like the PC versions of Portopia, featured a simple “verb noun” text parser. And like the Famicom version of Portopia, the Famicom version of this game replaced that with a menu, with the overall HUD even looking kinda similar.. Also like Portopia, the Famicom version added a few first-person mazes, but apart from the third one they’re actually much simpler to navigate than the one in Portopia, though it can still be somewhat easy to become disoriented.

Another thing the Famicom version added, which is very strange, is the combat system. The combat, or finger wars as the game calls them, plays out as rock-paper-scissors. Specifically it uses what I’m assuming is an additional Japanese rule where, after somebody loses the toss, the winner points in a certain direction and at the same time the loser looks in a certain direction, and if the loser looked in the same direction as the winner pointed then they actually fully lose the point. It’s a pretty strange addition, but most encounters have some sort of pattern you can exploit or a weakness such as always throwing the same sign or looking in the same direction. If not, then it really just comes down to luck, which can be a bit frustrating.

The graphics of the PC versions have a somewhat similar style to the PC versions of Portopia in how they’re drawn, with very simple lineart with solid fills. But the sillier tone of this game allows that graphical style to work very much to its advantage compared to Portopia. The characters are very colorfully drawn with some really out there designs. Overall the game looks very stylish but also completely weird and crazy, similar to a couple of Hudson’s other visual novels from this era: Dezeni Land and Dezeni World. The Famicom version on the other hand ended up having to redraw the graphics, mostly due to the fact that they had to be crammed into a smaller area to make room for the new menu elements. The graphics in this version turned down the crazy and turned up the cute, which I’m sure gave it some wider appeal. And the characters really do look cute, especially Princess Tomato herself, who is just precious.

The game, at least the Famicom version, also has a huge leg up on Portopia in that it features music. It’s pretty serviceable and mostly has the same cute feel as the rest of the game, with the exception of the music used in the maze sequences which sounds appropriately mysterious and the music that plays in chapter 5 (the resistance base) which sounds way overly dramatic for some reason. My favorite tracks are probably the songs that play in chapter 2 (Saladoria) and chapter 8 (Minister Pumpkin’s castle).

I think this is a pretty good game and actually wish the PC versions of it or even the two Dezeni games had translations so I could check them out more fully and see just how weird Hudson got with them. Before playing it, my only experience with the game was the GameCenter CX episode, where it became known as “the game that made Arino fall asleep,” but it probably just isn’t his cup of tea, who knows. Anyway, next time I’ll be tackling either J.B. Harold Murder Club or Crystal Dragon, neither of which I really know anything about. Until then, take it easy~

#text post#backblog#backlog#backloggery#video games#princess tomato in the salad kingdom#salad no kuni no tomato-hime#hudson soft#nintendo entertainment system#famicom#adventure#visual novel

1 note

·

View note

Text

Backblog #15 - Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken (NES)

As mentioned previously, this time we have Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken, known in English as The Portopia Serial Murder Case. Developed by Yuji Horii of Dragon Quest fame (and the Famicom version by Chunsoft) and published by Enix in June of 1983, it was originally released on the NEC PC-6001 before being ported to numerous other Japanese PCs and then eventually the Famicom (the version I played, thanks to a translation patch from DvD Translations), all in Japan only, of course. More recently, a full remake was released on Japanese mobile phones alongside two other games (Hokkaido Rensa Satsujin: Ohotsk ni Kiyu and Karuizawa Yuukai Annai) from the Yuji Horii. It is among the earliest games in the visual novel genre (the only games on vndb.org actually listed as being released earlier are Lolita: Yakyuuken and Lolita 2 by PSK and only the second one of those is anything more than strip rock-paper-scissors). For this and a litany of other reasons, it is among the most important early releases in Japanese gaming history.

During his time as a journalist for a video game column for Shonen Jump, Yuji Horii entered a game programming contest held by the then brand new company, Enix, in order to source talented developers and build their initial library of games. Horii managed to place in this contest with Love Match Tennis. Another big player also came out of the contest in the form of Koichi Nakamura with his puzzle game, Door Door, which featured a player character named Chun, who ended up becoming the namesake of Nakamura’s development contracting company, Chunsoft. Together, the winners of the contest all used their prize, a trip to the United States, to attend the 1983 Applefest in San Francisco. It was here that Horii encountered the western computer RPG, Wizardry, which proves to be very important later.

Soon after Enix’s initial spree of releasing all of the contest games for a wide variety of Japanese PCs, Horii ended up working on Portopia. He derived the concept of the game after reading in a PC magazine about interactive fiction games in the west, such as Zork, and deciding it was an untapped market in Japan. Portopia was designed to be his take on that genre, even featuring a simple “verb noun” text parser. One of his major additions to that style of game was graphics depicting the current scene in the story: the “visual” part of “visual novel.” He also wanted to use the opportunity to experiment with more non-linear storytelling, which was sorely lacking in Japanese games at the time. The game was programmed in BASIC and released for various Japanese PCs over the course of 1983 and 1984 to great success, laying the foundation for the entire visual novel genre. A lot of early visual novels even share the mystery theme of this one.

After the Famicom was released and Enix started porting some of their games to it, Horii wanted to make a game in the style of Wizardry for it. However, Enix felt that the Famicom was still too much of an action platform compared to PCs and they weren’t sure how well a game of that type would do. So, it was decided to first go with the cheaper option of porting Portopia to the Famicom to see how a more adventure-oriented game fared in that market. Horii teamed up with Nakamura’s Chunsoft and work on the port began. One of the major additions to this version was an underground maze section in the style of the Wizardry games used to test the Famicom’s ability to handle something like this. Upon release, the Famicom version of Portopia, of course, also did extremely well and Horii was allowed to work on Dragon Quest along with Chunsoft, which itself became the template for all future JRPGs. So, in addition to kicking off the visual novel genre, its continued success ultimately led to what we now think of as a JRPG. Granted, Dragon Quest isn’t the very first Japanese RPG, The Black Onyx predates it by a few years for example, but it was certainly the most influential. And hell, if that weren’t enough, Portopia is also one of the games that inspired Hideo Kojima of Metal Gear fame to enter the game development scene after he was moved by its storytelling.

The story of the game itself (as told in the manual, since the game itself starts off with the case already having begun with no immediate context) is that Kouzou Yamakawa, the president of a loan shark company in Kobe, was found in his home by his secretary and security guard, dead from a stab wound to the neck. Because he was found in a room that was locked from the inside, the obvious conclusion is that it was a suicide, but owing to his position, the man did have a lot of enemies, so it falls to you, an unnamed veteran homicide detective to investigate. You spend the game searching the murder site and the surrounding cities, gathering clues, interviewing suspects, and establishing motives, hoping to determine the culprit of the crime, if there even is one. It’s a classic sealed-room murder mystery.

As you explore the game and perform your investigation, it is actually your subordinate Yasuhiko Mano (or Yasu for short) through whom you interact with the world by commanding him to perform various functions. In the original game, as mentioned above, this is done by a simple text parser, but since this isn’t really a possibility for the Famicom, that version instead has a large menu of all of the actions you can ask Yasu to perform. The actions include: move, ask, investigate someone, show item, look for someone, call out, arrest, investigate thing, evidence, hit, take, theorize, dial phone, and close case. Some of these are more important than others. For example, I don’t remember “look for someone” ever being successful over the course of the whole game, whereas investigate someone is important for learning new bits of information and investigate thing is important for gathering new clues. Theorize is another command that’s never technically necessary during the game but it can serve to give the player some hints.

Possibly the most frustrating facet of the game is the fact that selecting investigate thing and then selecting magnifying glass brings up a magnifying glass cursor that you use to actually select a point on the screen. I would say this creates an irritating example of pixel-hunting but I can’t even really call it that because sometimes there isn’t even a pixel. Sometimes when this needs to be done to find a new piece of evidence, you’re required to select a spot on the screen where there doesn’t appear to be anything at all. Adding to this is the fact that it can be pretty specific where you actually need to search. It might not be enough to search under a table, instead requiring you to search a pretty small region under the table. I obviously wouldn’t mind this if there were any visual cue, but sometimes there just isn’t. It isn’t a huge aspect of the game by any means, but whenever I did get stuck, it was almost always because I didn’t meticulously comb every inch of some screen. To be fair, I believe every time this comes up is on one of the locations in or around the house where the victim was found dead, so it does make sense that I should have been much more thorough with the magnifying glass there of all places.

The structure of the game is actually surprisingly open. You can more or less go anywhere in the game and find clues there or interact with the characters at any time. However, you still have to proceed with the main story linearly. Oftentimes, the aspect of the game that controls the flow of the story is events that occur in the police station at different times. For example, one of the suspects is one of Yamakawa’s clients that has been reported as missing and you can learn about him and start to follow that lead pretty early on. However, until you eliminate suspect of the first act of the game you can’t trigger the flag for the event in the police station that gives you the clue to find out where the missing client is and eliminate him. This structure is something I experimented with for a while during my playthroughs of the game. Even though you can almost completely set up the chain of events that ultimately leads to solving the case from the very beginning of the game, you end up missing one tiny little thing that lets you completely follow through with that lead until you proceed as normal.

Another big new aspect of the Famicom version of the game, as mentioned above, is the large Wizardry-style first-person maze located underneath the Yamakawa mansion. Like a lot of the game, you can access this pretty early on, but the most important part of it is still inaccessible, again via an event at the police station, until you complete the rest of the story. It’s a fairly complex maze and can be pretty easy to get lost in. This is mostly because of the sudden transition as you move square to square. It looks pretty natural when you’re just moving forward, but when doing turns, especially 180-degree turns, you can get pretty disoriented. To be fair, the same can be said of Wizardry, but it can be pretty hard to get used to after playing something like Phantasy Star where the animation for moving through the maze is much smoother and feels more intuitive. The maze does contain a Wizardry-style message (that turns out to be graffiti) saying that you were surprised by a monster, which is pretty amusing.

The true culprit, once you finally do cross off all the other suspects and find out who it is, is actually a pretty neat twist. It was considered so shocking at the time that it pretty quickly became a meme, even appearing as a gag in the manga, Rozen Maiden. It also served as the namesake for a character in another well-respected mystery visual novel, which I won’t reveal the name of, lest I spoil both of them. Unfortunately for me, I did go into the game already knowing the identity of the culprit, having been spoiled on it ages before ever even intending to play the game just due to how much of a cultural phenomenon it is, but it’s still a good story, with well thought out character motivations, and the lead-up to that revelation is cool nonetheless.

As mentioned above the graphics pretty much just consist of simple illustrations of the current scene of the story, with minor additions for some scenes, such as the ability for multiple characters to show up in the interview room in the police station. In the original PC versions, these graphics were drawn using lines and fills, looking somewhat like MS Paint drawings that took quite a while to be drawn on the screen, probably due to having to read from the disk. The graphics of the Famicom version are still crude (owing to not using any mapper chips to extend the Famicom’s graphical capabilities, which did make the game extremely cheap to produce), but less so, and loaded much faster. And I can certainly forgive crude graphics for such an early title. Probably the more unfortunate fact is that the game contains zero music. The only sound effects in the game at all are the sirens at the beginning and end, the noise that plays for the text scrolling, and a few sound effects in the maze. It makes the whole thing feel pretty lonely, which may or may not be intentional. The mobile phone versions did add music though, so there is that if you can find it.

Overall, apart from being an extremely important game it actually is a fun game with a good story. I’d definitely recommend it, especially if you’ve managed to avoid spoilers. It’s pretty short and can be beaten in a couple of hours at most, which is good since there’s no save function of any kind. Up next is a game that I’ve already finished just the other day, Princess Tomato in the Salad Kingdom, so the write-up should be rolling out pretty shortly.

Links:

DvD Translations’ Fan Translation - In addition to containing the translation patch itself, the readme also included a lot of contextual information on the game, much of which made it into this post.

#text post#backblog#backlog#backloggery#video games#yuji horii gekijou#yuji horii theater#yuji horii mysteries#portopia renzoku satsujin jiken#the portopia serial murder case#chunsoft#enix#yuji horii#koichi nakamura#nintendo entertainment system#famicom#adventure#visual novel

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Megaman 3

Hmm…

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Backblog #14 - Zoda's Revenge: Star Tropics II (NES)

Of course, my followup to StarTropics is its one and only sequel, Zoda's Revenge: StarTropics II. Developed by Nintendo R&D3 and published by Nintendo in March of 1994 in North America only for the Nintendo Entertainment System, StarTropics II is among the final games released on the console, along with the likes of Wario’s Woods and Adventure Island IV. Like the first game, it was never released in Japan, even for the Virtual Console releases. Also like the first game, it is an action-adventure game, but this one arguably trends even more toward the action side of the scale.

The story picks up very shortly after the end of the first game, with Mike back in his hometown of Seattle. The ending of the first game reveals that the three MacGuffins that Zoda was after contained a time frozen group of children of the alien race he sought to exterminate, the Argonians, including their princess, Mica. At the beginning of the the second game, Mike is telepathically contacted by Mica and she gives him a clue that she received from her father, Hirocon, in a dream that may help solve the cipher that was etched into the escape pod they were sent away in. Mike immediately goes to see his uncle, the archaeologist from the first game, Dr. Jones, and relays the clue to him. After they solve the cipher, Mike reads it aloud and is flung by its power into the distant past, into the Stone Ages.

Here, Mike is able to help a group of friendly cavemen he meets by defeating a gigantic beast that had been plotting to eat their children, and finds a strange object shaped like a Tetris piece in the beast’s cave. Mica manages to contact Mike again and informs him that the object is called is called a tetrad (or a “block” in the Virtual Console releases, which is a change that certainly makes more sense than calling a yo-yo an “island star”). She postulates that Hirocon probably intended for Mike to seek all seven of them out and that they are hidden across the Earth throughout time.

And this is the basic structure of them game. Each chapter (nine in total including the first one which just comprises the intro cutscene with Mike in Seattle) has Mike jumping to a different time, fighting his way through one to two dungeons, and retrieving a tetrad. The time periods represented range from Ancient Egypt to the Wild West to Renaissance Italy. You also meet a handful of historical (and one fictional and two legendary) figures in the various time periods: Cleopatra, Sherlock Holmes, Leonardo da Vinci, King Arthur, and Merlin, who all help to guide you through your quest. At some point you figure out that there is more than one Zoda (Zoda-X, Zoda-Y, and Zoda-Z) and they are all competing with you to find the tetrads.

The game also isn’t without the lighthearted charm that was present in the first game. The interactions with the historical figures are often comical, with Cleopatra refusing to help until you find out what’s taking her pizza delivery so long (turns out the delivery man was using a koopa instead of a camel) and Leonardo da Vinci changing the Mona Lisa’s hairstyle to one that Mike comments is “radical” in extremely 90s fashion. There’s also, of course, the infamous Cactus Dance craze that has been sweeping all the nations of the world since this game was released and continues to do so to this day.

The idea of traveling to different time period setpieces is one that I like a lot in concept, but I don’t think it’s quite used to its full potential here. Some of the dungeons and bosses feel a little bit disconnected from their time periods. The dungeons in Renaissance Italy could really just be any castle anywhere and I really don’t know what a rock-throwing cyclops has to do with the Wild West. The worst offender for this is probably the Sherlock Holmes-era one in London. This chapter would be a great set-up for a segment that’s more focused on a longer travel stage rather than the action stages, maybe with a very simple mystery for the player to solve. But instead of anything like that, most of it is two very irritating sewer levels.

However, the setpieces are mostly fine outside of this and they do give the dungeons that little bit more of character I thought they needed in the first game. That, and the game ends on a very strong note, with you returning to present day C-Island to delve into the first dungeon of the first game and fight a skeletal version of its first boss, followed by a boss rush leading to Zoda-Z. It’s a pretty cool moment and I like it a lot when games do things like that in general (Dragon Quests II and III do this, for example). The only damper on this is that I don’t care too much for the remix of the dungeon music from the first game that is used here. It’s a lot more downbeat and doesn’t sound nearly as exciting as it probably should.

The gameplay of each individual chapter is pretty much structured the same as the first game with travel stages where you adventure around and find your way to action stages where you fight your way through dungeons. The travel stages feel a bit more pushed to the side in this one, however, with more of them feeling like straight shots to the action stage. And more often than not, the the travel stage bridging the first and second actions stages really are just short hallways, becoming more like checkpoints. One somewhat large change to the travel stages is that there are a few chapters that have areas where you will fall into a pit leading to a random miniature action stage in the middle of a travel stage. This comes to a head in the Renaissance Italy chapter, which is full of this.

The action stages themselves feel very similar to the first game though, being mostly linear gauntlets, and are often pretty challenging. Their design in general feels more streamlined and includes some new elements. There is now verticality to their design, or as much are there can be in an overhead game. You sometimes have to jump up a couple of levels higher to cross a series of gaps or are forced to come back into a room from a different, higher up, entrance in order to proceed. There’s also added elements such as moving platforms (more on those below) and arrow tiles that either move you slightly or sometimes send you hurtling in the direction of the arrow. There is also even less puzzles to solve now. The action stages really live up to their name here.

Unlike the first game, instead of the yo-yo you have that gets upgraded over the course of the game, Mike is armed with a regular weapon (initially a stone axe, then a bronze dagger, then a katana) that he just throws infinite amounts of and a psychic shock wave that upgrades twice over the course of the game. The shock waves are typically the better choice due to being faster and having longer range and even feels more like the yo-yo and its upgrades. Although, neither of them have as much charm as using a yo-yo as a weapon, I feel. There also isn’t as much of a variety of subweapons as in the first game, but I guess this is really because you usually have two primary weapons.

The biggest and most frustrating change is, ironically, the fact that the controls are not as rigid as they were in the first game. Unlike the first game, the movement is no longer tile-based, with Mike able to move pixel-by-pixel and even move diagonally. He generally feels a lot swifter and it’s easier to out-maneuver enemies. Which all sounds great, until you factor in the jumping. The jumping is also a lot less rigid and you are able to adjust jumps in midair, which somehow makes the platforming (which there is a larger emphasis on here) much more irritating to do. Overhead platforming is already a bit of a pain to judge correctly compared to side-scrolling and the first game gets around this by making it all tile-based. As long as you’re actually jumping to a tile you can reach and the tile doesn’t disappear, you’re fine.

But here that’s not exactly the case, and the collision for this feels a lot more sensitive than it needs to be. Oftentimes, the falling to your death animation appears to be overlapping the platform you were attempting to jump to. At one point I even slipped through a one-pixel gap between a moving platform and the floor because I guess even that much of a pit was enough for Mike to fall into. The trick to get around this (for non-moving platform jumps at least) is to just completely ignore the fact that you can adjust at all. If you press a direction and jump, Mike still jumps across a tile just like the first game. Any aerial adjustments that happen after this can often be fatal and there’s no point really to making them. But moving platforms throw a wrench into this since you might actually need to adjust in order to account for their movement. Additionally, they’re the only platforms in the game you’re able to walk off of to your death, compounding the annoyance that comes from them.

Graphically, the game has more or less the same look as the first one, but generally the sprites look a little bit better, especially in the travel stages, which was graphically the weakest part of the first game. And Mike now even sports a denim jacket instead of just a blue shirt, for maximum 90s aesthetic. The CGs used during cutscenes have an identical artstyle to the first game, which is fine because they did and still do look great. Also, the gripe I had about the dungeons mostly looking the same in the first game is mostly solved here, as I mentioned above. There’s also a lot more of a variety of music which is generally pretty good, outside of the somewhat lame remixes of music from the first game in the final chapter.

There’s often a debate on whether or not this game or the first one is better, and I think it’s probably pretty clear which side of that debate I’m on. I ultimately prefer the first game and don’t think this one fully stacks up to it. But this is still worth checking out. It’s also worth noting, going back to the Zelda comparison I made when talking about the first game, that this game postdates both A Link to the Past and Link’s Awakening and certainly feels nothing like either of those games. Even if the first game could be considered vaguely a Zelda clone, this one didn’t follow through on that at all and continued to just go more in the direction the first game established.

Unfortunately, this pretty much closes the book on this series for me (not counting the StarTropics III fangame which probably won’t ever be finished anyway). It’s most likely that the game’s very late inclusion in the NES lineup is what ultimately contributed to the downfall of both it and the series as a whole, which is a shame because I do like these games overall. Oh well. The next thing on my list is, as of it being translated at the end of this August, Metal Slader Glory. And it being an early visual novel, of course means I’m going to do another little genre detour. So, the next game I’m actually going to play is most likely going to be Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken. Until then, take it easy~

#text post#backblog#backlog#backloggery#video games#startropics#zoda's revenge: startropics ii#nintendo#nintendo entertainment system#action-adventure

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Backblog #13 - StarTropics (NES)

The game I played for this entry is StarTropics. StarTropics is somewhat unique in that it was developed in Japan by Nintendo R&D3, but was made specifically for western audiences. It was published by Nintendo on December 1, 1990 in North America and a couple of years later in Europe. It actually was never released in Japan at all, even when the game was re-released on the Virtual Console for Wii and Wii U. It is an action-adventure game, but more specifically, it is often considered to be Nintendo’s clone of their own game: The Legend of Zelda.

The story of the game sees you as Mike Jones, a high school student in Seattle and ace pitcher for his baseball team, visiting his uncle Dr. Steven Jones, a famous archaeologist, on his tropical island home on C-Island in the South Seas. Upon arriving you are informed by the chief of the nearby village of Coralcola that your uncle has been kidnapped. The chief gives you your primary weapon, an island yo-yo (renamed an “island star” in the Virtual Console releases, strangely), warning you that the underground regions of the islands have been full of monsters recently. Later, Dr. Jones’s assistant, Baboo, grants you use of his submarine, the Sub-C (which contains a navigational computer named Nav-Com that resembles Nintendo's R.O.B. peripheral), to aid you in your search for your uncle.

Throughout his journey across eight chapters and numerous tropical islands, Mike ends up on many little misadventures. These include rescuing a young dolphin from a monster (which definitely pays off for him during the ending), needing to dress in drag to enter a castle populated entirely by female warriors, and even finding himself swallowed by an immense whale. Ultimately, you discover that the kidnapping was done by a race of evil aliens led by a tyrant named Zoda and end up both rescuing your uncle and foiling their plans. It’s a pretty simple setup and is executed in a pretty lighthearted and goofy manner, with lots of silly interactions with NPCs. There’s even a weird running joke about Mike putting bananas in his ears. At first, when characters bring it up early on, it’s just referring to him not listening and things like that, but at the end of the game he literally shoves bananas in his ears to prevent Zoda from invading his mind. There's also numerous little details that make clear the game's intent to appeal to a western audience. These range from little things like Nav-Com codes being important dates from American history (1492 and 1776) to the multiple references to cola to a reference to Nester from Nintendo Power.

Each of the chapters is split into adventure segments (which the manual refers to as travel stages) where you move around the overworld, talk to friendly NPCs, and gather clues, and one or more action segments (referred to as battle stages) where you fight your way through dungeons. The sole chapter to not have a single battle stage is chapter four, where you just need to find your way out of the inside of a whale. But the chapter directly prior to that one is the longest in the game, with a total of five dungeons, so that’s okay. The overall structure of the game is much, much more linear than the original Zelda, which is the biggest and most important difference between the two. The game being structured into different chapters (each with their own locales, no less) means that the game only ever moves forward. The only way to revisit locations from previous chapters is to select them via a “Review Mode” from the file select menu. However, doing this doesn’t let you collect optional items (such as heart containers) that you missed on your first time through. Even if you collect them during your Review Mode replay, they aren’t saved, so it really is just for if you want to replay a certain part.

The travel stages are very straightforward. You usually just have a single little village to visit and one or two NPCs you need to talk to and key items to get that separate you from the next dungeon. There are a few puzzles here such as hidden passages in walls, a music puzzle, and an infamous one that requires you to physically dip a letter that came with the game in water to reveal a frequency you need (747). Digital versions of the game on Virtual Console or NES Classic luckily include a little animation of the letter being dipped in the digital manual to accommodate this puzzle. You’re also never in any danger on the overworld, unlike in Zelda. Likewise, the battle stages are typically structured more like linear gauntlets, with most of the difficulty coming from dealing with the enemies and platforming (more on that later). There is some minor puzzle solving here and there. If the path forward isn’t immediately apparent you might have to step on a hidden switch or use an item to reveal a hidden ghost that you need to defeat for a door to open. Granted, Zelda’s dungeons didn’t start to get particularly complicated with the puzzles until A Link to the Past. In the first one if killing all the enemies or pushing a block didn’t work, you probably just need to check to see if the walls can be bombed or walked through and that’s about it. But the original Zelda’s dungeons were structured more like labyrinths than linear gauntlets so that’s where their complexity came from.

But this game’s lack of the original Zelda’s nonlinearity or obtuseness doesn’t mean it’s an easy game. It just puts more of its chips into the action side of things. There are a couple of comically unfair traps early on (walk into the wrong room or go north to the next screen in the wrong way to just die immediately), but a lot of this difficulty can come from trying to get used to the strange, almost restrictive, controls at first. Unlike a lot of games, even for that era, Mike’s movement is entirely based around tiles. He can’t slightly move forward a mere partial tile’s distance and furthermore, once you perform the input to trigger the movement, you’re stuck in the animation until he walks that entire tile. You can actually turn during the walk animation which you can use to orient yourself in the next direction you want to walk (which is kinda fun, because it feels like you’re making Mike drift) or to attack enemies as you walk by them. You also have to hold the direction down for a split second before Mike actually starts moving, since it’s also possible to turn in place, which is useful in its own right, but adds to the overall sluggish feeling of the movement.

Most of the time though, even though the movement takes a lot of getting used to, it feels like the game is balanced around it. Mike also has a very useful jump he can use which really helps in this regard. Usually, if an enemy is too swift for Mike’s slow ass or has a very quick projectile, you’re meant to neutral jump over it to dodge. But more than being used a defensive move, the jump is used for the game’s basic platforming. Mike can jump over one tile wide gaps (or more, but only with the help of a certain item) and you often find yourself jumping between the game’s many tiles looking for hidden switches. It’s also possible to turn in midair in order to attack enemies to your sides, which is sometimes necessary. Also, if you mess up the platforming by jumping in the wrong direction or attempting to jump on a platform after it’s disappeared or something like that, Mike will die instantly, so caution is advised.

Mike’s health is represented through hearts, the maximum of which increase after each dungeon and by finding heart containers on the overworld, again like in Zelda. The hearts can be restored either by enemies either dropping them directly (which is quite rare) or dropping stars, five of which restore a single heart. But more often than not, they’re restored by just finding them in the dungeon or using potions. Mike also has a stock of lives that allow him to continue from checkpoints within the dungeon, but running out kicks him all the way to the beginning of it. Your primary method of attack is with your yo-yo/island star which is relatively weak and short-ranged. You get a couple of upgrades over the course of the game, the Shooting Star and then the Super Nova, but they only work if you have enough health. If your health drops below the threshold, your weapon will be downgraded. In the later stages of the game, losing enough health to get dropped all the way back to the yo-yo can feel like a death sentence if you don’t have any special weapons and you may as well just reset.

The special weapons include things such as baseball bats, bolas, and even laser guns. All of them have ammunition, even where it doesn’t make sense like the baseball bat (maybe it breaks after so many swings?), so use them wisely. There are also magic items that need to be used from the pause screen such as the aforementioned potions, snowmen that freeze all enemies onscreen, or rods of sight that reveal the locations of otherwise invisible ghosts. It’s also noteworthy that these items do not transfer from dungeon to dungeon or even life to life (so don’t bother trying to save them, use them if you need them!). This is another thing that makes the game not really feel much like Zelda to me. Unlike that game where you’re slowly building a large stock of weapons and items that you sometimes need to go out of your way to get, the only thing Mike really permanently gets to keep is his primary weapon and hearts.

The graphics of the game also differentiate the adventure and action segments of the gameplay. The travel stages actually resemble early 8-bit JRPGs more than anything and honestly could probably look a better for as late in the NES’s lifecycle as the game released. Once you enter a dungeon, however, the game adopts a more zoomed-in perspective and looks a ton better. In particular, the monsters and especially the bosses all look great, with special commendations to Maxie the Ghost and the second form of Zoda. The only problem I have with the dungeons is, save for the ones in the final two chapters, that they all look very samey visually, with nearly all of them just resembling green caves. One major graphical nicety the game has is CGs for when you’re talking to important NPCs (such as Chief Coralcola or your uncle) and during the ending, all of which look very impressive and showcase the more western artstyle they were going for. The music in the game is one of its strongest assets, with the standout track being the primary dungeon theme, which is extremely catchy and even sounds kind of cute (the same could even be said of the sound effects). However, like the visual feel of the dungeons, it can get a little old since it’s used in all of them except the ones in the final two chapters.

I mentioned a few times that the game has major differences from the original Zelda that almost make it feel like a different kind of game. The superficial similarities are definitely there for a reason though, the developers clearly set out to make a Zelda clone (this is clear from the moment you hit the file select screen, which looks almost exactly the same), but maybe didn’t understand exactly what it was that made the original Zelda so special. It could also be argued, of course, that while the first Zelda obviously wasn’t even close to being the first action-adventure game or even the first action-RPG, it made such waves in the genre that everything we think of as just being a staple of the genre now was more or less pioneered by Zelda, so that all you really needed to be considered a clone is to just be in the same genre. I’m honestly not sure, because I don’t really have enough pre-Zelda action-adventure context to know. Either way, even though I feel like this game is actually pretty different, it’s definitely a great game in its own right, if a bit frustrating in some spots with its difficulty. It’s a shame it didn’t catch on as well as Nintendo seemed to want it to, but this is probably due to its very late release. In any case, next time I’ll be closing the book on this sadly short-lived series with Zoda's Revenge: StarTropics II.

#text post#backblog#backlog#backloggery#video games#startropics#nintendo#nintendo entertainment system#action-adventure

1 note

·

View note

Text

Backblog #12 - Dr. Mario (NES)

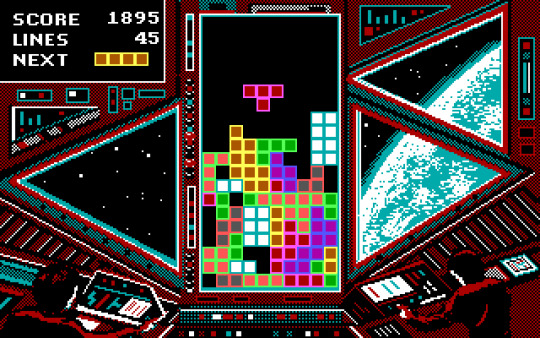

Finally, I’m back to the game that led me down this puzzle gauntlet in the first place: Dr. Mario. Dr. Mario is a falling block puzzle game developed by Nintendo R&D1 for the Famicom and published by Nintendo in Japan on July 27, 1990. It was released for the NES in other regions and ported to many other Nintendo systems (such as the Nintendo Vs. and PlayChoice-10 arcade systems, the Game Boy, and even as part of an SNES compilation with the Nintendo version of Tetris) soon after. I ended up playing the original NES version, although I did consider the SNES compilation, since it would’ve been fun to briefly revisit Tetris, since I did essentially play all of those Tetris versions because of this game being on my list.

Like most games of this type, it is a very simple game. In it you play as Mario assuming the role of a doctor. Dr. Mario continually throws bicolored pills called megavitamins into the pill bottle shaped playing field. The field also contains three different colored viruses (blue, red, and yellow which were named Chill, Fever, and Weird respectively in a Nintendo comic) up to a certain height, depending on what level you select, similar to the height option found in other games like this. The objective of each level is to completely eliminate all of the viruses using the megavitamins by lining up four of the same color in a row horizontally or vertically (no diagonals). If a megavitamin ends up blocking the opening of the bottle then it’s game over. Like Columns and Klax, combos are possible, but, amusingly, clearing too many blocks at once causes the game to crash.

When the game starts, you are given the option to select a 1 player or 2 player game. Both modes begin with an options screen where the player(s) can select from 21 virus levels (from 0 to 20) which determines how many viruses there are in the field, the game speed from low to high (though the speed does gradually increase as you play no matter what starting speed you select), and the music selection. Although on two player mode, both players can select virus levels and speed independently of one another, in case one player requires a handicap or something like that.

In single player mode, completing each level allows you to proceed to the next one, with every fifth level cleared showing a short cutscene of the three viruses sitting in a tree and some kind of object flying by. After the final cutscene that plays after level 20, the game does continue but only goes up to level 24 and loops that level from there. Two player is a head-to-head versus mode seen in other games like this where the objective is to either clear your screen of viruses first or to just outlast the other player. Getting combos causes garbage blocks to drop on the opposing player’s field (although the system doesn’t always place the garbage intelligently and it is possible for these blocks to clear something for the other player). The versus matches are best of five so they can run a little long and the number of rounds unfortunately cannot be adjusted in the options.

The game is pretty appealing visually. As mentioned above, the playing field is supposed to be a pill bottle, though I always thought it was supposed to be the inside of whatever person you’re trying to cure (in fact, beta versions of the game, known as Virus, seem to support this by showing a sick animal that you’re supposed to be curing). In the top right, you can see Dr. Mario himself in a typical doctor getup actually throwing the pills into the field. And in the bottom left you can see the viruses themselves, which have very cute classic alien or monster designs, dancing around and taunting you (until you gradually get rid of all of the viruses of a certain color, which removes them from this view). The viruses are seen under a magnifying glass instead of something like a microscope, implying that they’re enormous. I guess this is true, since they can be seen from the naked eye in a tree in the endings. Also, in the level 20 ending, the thing which flies by the tree is a UFO, which picks the viruses up. So, I guess they actually are aliens. Maybe Tatanga did Dr. Mario.

Of the two selectable songs in the game that play during actual gameplay, “Fever”, with its upbeat and extremely catchy tune, is by far the more recognizable song and is generally thought of as being the Dr. Mario theme. “Chill” is a much more downtempo theme and, although I don’t think it exactly works for something that gets as fast paced as this game often does, I think it’s a fine song in its own right. And the verses of it where the tempo picks up sound pretty, uh... cool. Both songs have moments where they sound sort of deliberately chaotic or off-key, which works since they’re supposed to be the theme songs of these weird alien viruses that I guess are causing havoc on some dogs or something if the aforementioned beta version is anything to go by. Unfortunately, there isn’t a third song called “Weird” for the yellow virus. It’s a shame, because I really would’ve liked to hear a song like that.

Overall, this is a very good game, though simple like all games of this type. Not that its simplicity is a bad thing in the least. That’s actually the greatest strength of games like this. Anyone can pick them up and instantly understand the rules. It’s easy to learn but hard to master, which is pretty much exactly where you want a game to be, especially if it has a multiplayer versus mode like this one does. Though this game, being height based, is very easy in the early levels when there are barely any viruses. Even in later levels where there are quite a few more, it gets much easier as soon as you are able to break through the first layer or so of viruses. But level 19 is about where I fall apart completely and am barely able to progress in eliminating viruses at all, so it’s definitely no cakewalk, it just feels a little easier than similar games. Next time, I’ll finally be moving past puzzle games and to one that I’ve been looking forward to for a while now: StarTropics.

#text post#backblog#backlog#backloggery#video games#mario#dr. mario#nintendo#nintendo entertainment system#famicom#puzzle#falling block

1 note

·

View note

Text

Backblog #11 - Klax (Lynx)

It is the nineties and there is time for...

Klax is the game I played this time (and so soon after the last one!). It is a falling block puzzle game developed and published by Atari for the arcades on June 4, 1990. The arcade release was followed by a large number of ports, many of which were handled by Atari’s console/computer game publishing division, Tengen. Among the systems it came out for were the Atari 2600 (in fact, it was the last game officially published for the platform), the NES, the Genesis / Mega Drive, the TurboGrafx-16, the Lynx, the Atari ST and many others. It also had fanmade and prototype versions made for the Atari 5200 and 7800 repsectively. The version I ended up playing was the Lynx version, both because it’s one of the better versions and it’s one on one of Atari’s own consoles, so it just seemed right.

Klax was originally meant to be the follow-up to Atari’s popular arcade conversion of Tetris, but ended up becoming more of its own thing due to the legal dispute. Like Tetris and Columns, Klax has tiles coming from the top of the screen (though it’s a bit visually distinct from the others in that they’re actually tumbling down a conveyor belt). The difference is how you control them, and it is actually a pretty major difference. You don’t have any control over the tiles until they land on the paddle you control at the bottom of the screen.

You use this to catch them and arrange them in the 5 by 5 well below. The paddle can hold up to five tiles at once and places them starting from the top of the stack. It is also possible to bounce pieces back up the conveyor belt and catch them again if you need to shift your pieces around, but attempting to juggle them this way can cause further complications if you’re not careful. Any pieces that aren’t caught by the paddle are considered drops. Running out of drops or completely filling up the well results in a game over.

The paddle is used to create vertical, horizontal, or diagonal lines of at least three, known as a Klax. Verticals are worth the least amount of points and diagonals are worth the most. Certain moves such as getting lines of four or five or getting multiple lines (such two diagonals at once) with one piece counts for more Klaxes than normal. Also like in Columns, it is possible to achieve combos, though because of the smaller well of pieces they can’t be quite as long. Of course, the longer you play the faster and more numerous the pieces get. They also start appearing in more colors. There are also flashing wildcard pieces that can easily be used to get multiple Klaxes in one move.

The major gameplay distinction Klax has over Tetris is the way it is structured overall. The gameplay is divided into 100 waves (making this a rare puzzle game that doesn’t actually go on forever). Each wave is cleared by fulfilling a set goal, such as getting a certain number of Klaxes or getting a certain number of points. After clearing a wave, you are awarded bonus points for the amount of pieces remaining on the conveyor belt and the paddle and for the amount of empty space you left in the well. Before the first wave and every five waves after, you’re given the option to skip five or ten waves. Doing so gives you a point bonus and more drops. Also, during a couple of the early waves, you are given the opportunity to skip 45 entire waves by creating a large X (five piece long diagonal lines going in both directions). Doing so is easier said than done, of course.

Visually, this has got to be the most 90s puzzle game of all time. Many versions of the game even open with the quote at the top of the article. The title screen of the Lynx version has the hand that is typically the K in the logo signing the rest of the letters to make the colorful, multi-hued logo appear before assuming its place as the K. The background of the title screen consists of a pattern of shapes typical of 90s visuals. As mentioned above, instead of just dropping down a well like many other games of this type, Klax has the pieces tumbling end over end down a conveyor belt toward your paddle. The backgrounds, which change after every wave, are sometimes abstract and psychedelic. My favorite of the early ones is the one that has a large hand wrapping around the bottom of the conveyor belt as if it were the neck of a guitar. It’s also definitely worth noting that this is one of the games that requires you to rotate your Lynx so that it is in a portrait aspect ratio, which makes sense considering how the screen is laid out.

Unfortunately, in most of the versions I’ve seen including the Lynx version, there is no music during the gameplay. The sole song seems to be the bassy track that plays during the title screen. It’s a different song than the one that plays on the NES one for example, and not as good in my opinion. But it does somewhat make up for the lack of music with a wider array of sound effects than one might expect from a game of this type. Each different color of piece also makes a different sound as it makes its way down the belt. The brown pieces even make kind of a splat sound, which I’m not sure was intended as a joke or not. There’s also voice clips that play announcing what type of wave the upcoming one is and reacting when you pull off long Klaxes or combos. For such a small system, these voice samples actually sound very impressive.

Overall, this definitely one of the most unique and enjoyable puzzle games I’ve played so far. It does get pretty hectic very quickly though, since in addition to the pieces coming down you also have to pay attention not only to the pieces already in the well but also the way the pieces on your paddle are arranged. It’s just a little bit more to keep track of that makes the game that much more difficult. But hey, I’m not great at these games as it is, so maybe it’s just me. Anyway, for the next entry, we’ll be moving to the game that sent us through this puzzle game gauntlet in the first place: Dr. Mario.

#text post#backblog#backlog#backloggery#video games#klax#atari#tengen#arcade#atari lynx#puzzle#falling block

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Backblog #10 - Columns (Genesis)

Hey, it’s my tenth one of these things. And of all the games for it to cover, we have Columns. Columns is a falling block puzzle game originally developed in 1989 by a Hewlett-Packard employee by the name of Jay Geertsen for their proprietary HP-UX operating system. Of course, it was later ported to several other home computer systems, where it was eventually discovered by Sega. Sega managed to buy the rights from him and unlike some other puzzle games I could mention, everything went perfectly smoothly. Sega AM1 went on to develop an arcade port for the Sega System C arcade hardware which was published by Sega in March of 1990 and soon followed by numerous official ports, sequels, and unlicensed clones.

However, the version I played was the Genesis/Mega Drive version. This version was the first home console version and is a very accurate representation of Sega’s arcade version which it released only months after. Released very early in the console’s lifetime, it is one of the very first puzzle games on the system, due to the fact that Sega’s earlier Mega Drive port of Tetris ended up being shelved due to the legal issues surrounding it. This version in particular has appeared in many Genesis compilations including Steam’s SEGA Mega Drive & Genesis Classics, which is how I played it (hence the nice grid borders that actually perfectly match the playfield).

Of these tile-matching puzzle games, Columns is actually one of the earliest, along with Atari’s Klax. This is especially true when you only consider those in which the tiles are falling from the top of the screen. The earlier game, SameGame, for example, has you removing a finite number of matching tiles from the screen in an attempt to empty it completely. So I tend to think of that game as a tile removal puzzle game rather than a falling block puzzle game, but it’s all semantics.

Like Tetris, Columns has tiles falling from the top of the screen in stacks of three. You can change the order of the tiles within the vertical stack, but you cannot rotate it like you can in say, Puyo Puyo. It's called Columns after all. The goal is to match at least three of the same tile either horizontally, vertically, or diagonally to remove them before the playfield fills up completely. However, unlike the games Hatris and Faces..tris from the previous entry, this game has more of a chain combo focus. If you manage to arrange the tiles in such a way that removing one row causes another row to be formed after the first set disappears then you have a combo. It’s possible to get very long combos in this game, but I’m not especially good at them, and it felt like most of the really long ones I got were mostly luck.

The main mode in all versions is Arcade, which is the typical endurance mode where you just need to survive as long as possible. There are different levels of speed that rise as you play the game, similarly to Tetris. Unlike Tetris, however, starting from higher levels (the game gives you the option to start from levels 5 and 10 as the medium and hard difficulties respectively) awards you a starting bonus. Typically though, I like to start from level 0 even though it is technically the easy mode, just because I like to start from the bottom and try to work my way up as much as possible in these types of games.

The other two major modes, exclusive to the later ports, are Original Game and Flash Columns. Original Game is pretty much the console version of Arcade mode where you have more options. It has different difficulty classes: Novice, Amateur, and Pro, which seem to just affect how often you get pieces with more than one of the same color, which makes it much easier to build large combos. You can select any level from 0 to 9, instead of just 0, 5, or 10. You have the option to enable a time trial, which gives you three minutes to build as high a score as possible instead of just until the screen fills up. This option is actually a blessing on lower difficulties since those games can run for so long. And finally, you are actually given the option to change the music between the three possible tracks.

The second console exclusive mode, Flash Columns, is similar to Sega’s earlier Tetris sequel, Flash Point. Like in Flash Point, the object is to eliminate a single flashing gem. The difficulty class and music selection options are present here too, as well as a height option between 2 and 9 that determines how filled the screen is when you begin. Unlike Flash Point, the levels are not pre-built, but randomly generated based on the height you select. Also unlike in Flash Point, the score doesn’t really matter at all, since it only keeps track of your best time, so there’s no point in building up toward unnecessary combos that don’t get you any closer to the flashing gem.

Both Original Game and Flash Columns mode have 2-player versus and doubles modes. Strangely, during the versus mode, it is not possible to attack your opponent using garbage blocks at all, despite the fact that this was present is Sega’s earlier Bloxeed. This ends up making the multiplayer games feel somewhat slow-paced and boring since you’re just trying to outlast your opponent, especially compared to later games in the series where attacking with the crush bar became a major part of the game. The doubles mode simply has each player controlling every other piece. So compared to Atari Tetris where you both control pieces at the same time, it’s a bit easier to cooperate. But I still like the weirdness of Atari Tetris’s co-op mode.

Visually, the theme of the game is ancient civilizations. This is appropriate, since columns are often associated with classical architecture. This game specifically is associated with Ancient Phoenicia (the manual claims this is a game Ancient Phoenician merchants played with gems). However, later games are just based around the ancient world in general and have you traveling into Ancient Egyptian pyramids and locales like that. The title screen depicts vase art of two soldiers holding a bag of gems and the alternative title screen depicts two angels playing the game. The in-game pieces are all represented by different colored gems. Graphically, the game looks very accurate to the arcade version.

The three music tracks available during play are called “Clotho”, “Lathesis”, and “Atropos”, after the Moirae Sisters of Greek mythology. While they do capture the theme of ancient civilization pretty well in the way they sound, none of them really do it for me. And they definitely get old after playing for as long as some games can last. The one I come closest to liking is Atropos, which has kind of a nice melody in its intro, but loses me pretty soon after. Part of it could be the sometimes bad sound emulation in the emulator built into the SEGA Mega Drive & Genesis Classics collection, which sometimes makes the songs sound like they’re descending into complete lunacy to the point of almost being charmingly bad. But I have heard them properly emulated too and they’re not much better then.

Speaking of that collection, it did receive a pretty major update recently. I guess they didn’t fix the emulation issues, which obviously should be priority one, but they did add some fun extras. The games now have achievements and challenges (unfortunately just one of each per game at most) as well as online multiplayer, leaderboards, and region switching where possible. This game did have a single achievement (getting 5000 points on the novice difficulty class) and a challenge (getting 5000 points from a mid-game save where the gems are nearly at the top of the screen), both of which were fairly easy. The game also has the leaderboard and online multiplayer functionality. Unfortunately, the leaderboard is only for the easy difficulty, for some reason. Probably due both to these features being fairly new and this game being relatively unpopular compared to the others in the collection, my rank on the leaderboard as of now is actually pretty decent. When I told a friend of mine this, he said I was a real pillar of the Columns community, and I was furious.

Anyway, like all early puzzle games, this one really is a slim package. Despite having three major modes, there’s really not much to it and you can see everything it has to offer in a single session. But like all of these games, if the main gameplay entices you enough, then the lasting appeal becomes chasing higher and higher scores. Unfortunately, like a lot of early console puzzle games, this game lacks a battery save, so your high scores won’t last beyond a single session anyway. But it’s still a decent enough foundation for the series. I do like the later ones, though not as much as Puyo Puyo. Next time, rather than going after the other early Columns games (hitting this one did take me out of my current console generation, after all), I’ll be playing Atari’s Klax. Until then, take it easy~

#text post#backblog#backlog#backloggery#video games#columns#sega#arcade#sega genesis#sega mega drive#puzzle#falling block

0 notes

Text

New post, new computer #2

About SEVEN FUCKING YEARS AGO I made this post about putting together a new computer. It was my first one and it had some issues, but it lasted me that entire time. Recently though, it started to show its age, so I figured it was about time for a new one. So here it is (minus side panels for the case):

Specs are:

Graphics: EVGA GeForce GTX 1080 Ti SC2

CPU: Intel Core i7-8700K @ 3.70GHz

HSF: be Quiet! BK021 Dark Rock 4

Motherboard: ASUS ROG Strix Z370-E Gaming LGA1151

RAM: G.SKILL 16GB (2 x 8GB) Ripjaws V Series DDR4

Storage

SSD: Samsung 970 EVO 1TB

HDD1: Western Digital Red 6TB NAS

HDD2: Seagate Barracuda 1TB (pulled from the old computer and repartitioned after I got everything I need from it)

External HDD: Western Digital MyBook 3TB (also something I’ve had since the old computer)

Optical Drive: LG Electronics 14x SATA Blu-ray Internal Rewriter

Power Supply: CORSAIR HX850

Case: be quiet! BGW12 Dark Base PRO 900

Operating System: Windows 10 Home 64-bit