Text

Social Classes and The Imperial Examinations

There's a common stereotype that East Asians (specifically the Chinese) are scholastically inclined. In particular, there's the idea that the Asians are particularly good at standardized tests. Oddly enough there's a sound cultural basis for this view.

There are three broad ways to describe ancient China. The first is that it was an agricultural society, where farming was considered the root of a nation. One of the major roles of the Chinese central bureaucracy was the matter of grain distribution and, in the case of the Emperor, performing ritual ceremonies to maintain good weather and bountiful harvests. After all, you can't have order without well-fed and happy people.

Second, China was an imperial bureaucracy. It was run by local governors and reams of paperwork, processes, and procedures. This concept of bureaucracy was so central to the Chinese identity that, as I've pointed out earlier, even the religious pantheon and the afterlife are viewed as grand bureaucracies in which gods are paper-pushers.

Third, China was, in theory, a meritocracy. It was a society of marked class distinctions, with merchants on the bottom, peasants and farmers in the middle, and scholars and bureaucrats at the top. Yet in theory anyone, even the lowest peasant, could become accepted as a bureaucratic official, or even the Emperor himself. In fact, the first emperor of the Ming Dynasty, Zhu Yuanzhang, was born to a peasant family in a region that suffered from famine, flooding, and plague. And the best method of climbing the socioeconomic ladder? Standardized Testing.

The first Emperor of the Ming dynasty, of peasant stock.

The earliest form of the Imperial Examinations occurred in the Han Dynasty, stretching back to the earliest days of the Empire. However it was mainly under the Sui and Tang dynasties that the Examinations grew prominent. By the Song dynasty, the use of the Examination system to select government officials was widespread in order to counteract the influence of the military in the central government. This led to the rise of the popular image of China as one ruled by scholar-officials, in which the literati was the highest class.

The Examinations were tiered systems, with examinations at the local level, the provincial level, and the national level. Topics included cultural and militaristic studies packaged into the Six Arts (music, arithmetic, writing, rituals/ceremonies, archery, and horsemanship) or the Five Studies (military strategy, civil law, taxation, agriculture/geography, and the Confucian Classics). The actual test could take up to three days to complete, and the rooms and cubicles were furnished with makeshift beds for this purpose.

Examinees about to take the civil service exam.

In good eras the Imperial Examinations were very fair in execution. Test-takers were completely isolated in their rooms. You ate there, you slept there, you did you sinful business there for three whole days. If you happened to die in the middle of taking the exam, the proctors would just wrap your body in straw and toss your corpse over the wall for your family to collect. To keep down the threat of nepotism or favoritism, measures were taken to ensure double-blindness. Test-takers were identified by number rather than name, and an intermediary would recopy the examinee's essays before sending it off to be evaluated by an official. Anyone, even the lowest peasant, could take the test. The main exception in some eras was that the merchant class, scorned as one of greedy and corrupt profiteers, was sometimes barred from taking the Exam.

If you had a good performance on an exam, you could be well on your way to becoming an official.

Unfortunately there was also a dark side to the Imperial Examinations. While it is true that many low-class peasants rose to power through their excellent performances on the Examinations and their demonstrations of devout filial piety, in truth the system was built to favor the wealthy. The poor, after all, could not afford the good tutors the wealthy had access to. Nor could they invest nearly as much time in studying that children from the upper classes could, since a large hunk of their lives had to be devoted to working the farm.

A Ming Dynasty official. The seal on his chest of two cranes indicates an Official of the First Rank.

By the time of the Qing dynasty, when the Manchurian ethnic group invaded and seized power from the Han majority, the examinations were used more as a social pressure valve rather than a pure method of selecting eminent scholars to populate the bureaucracy. By advertising the generic idea that hard work and study lead to success, the Manchurian rulers were able to, for the most part, suppress the bulk of ethnic and social dissent. Instead of revolting against the tyrannical system, peasants were thus encouraged to refocus their energies towards studying in order to change things, even if their chances of doing so were slim to none.

What the Imperial Examinations did then was provide an illusion of meritocracy for the lower classes, a placebo to their socioeconomic inequality. If their success was solely in their own hands, then they couldn't blame the central government for their lack of social mobility, could they?

“Filthy Peasants.” Azula is often referred to as a “classist.” While class divisions certainly did exist, in principle so did social mobility.

This all came to a head in the mid-1800s, when the schoolteacher Hong Xiuquan failed the examinations five times in a row due to the internal corruption of the Examination system. Suffering a nervous breakdown, Hong Xiuquan came across some Christian pamphlets left behind by a missionary and began suffering from religious hallucinations. Believing himself to be the younger brother of Jesus Christ, Hong burned all his Confucian and Buddhist books and statues, and started preaching to the public about his insane, crazy-filled craziness. Over time this movement expanded into a major anti-Manchu movement, the Taiping Rebellion, a 15-year revolt that claimed the lives of 20-30 million civilians and soldiers. This dwarfs the death toll of the American Civil War, which was a small fraction of that.

Hong Xiuquan, who initiated the Taiping Rebellion. His story is a lesson on how corrupt and false meritocratic systems can only stave off civil dissent for so long. That, and Chick Tracts fuck over everything.

Over time the Chinese began to view the Confucian Classics as archaic teachings that no longer had any relevance to the post-industrial era, and the society moved on. Despite this the Chinese view of education is to this day deeply ingrained. In the 2nd major wave of Chinese immigration in the 20th century, despite rampant racism and ethnic marginalization, immigrant parents told their American-born children to focus on getting good grades and on getting into good schools. “They can take away your dignity, but they cannot take away your education” was an important motto. To this day East Asian families still emphasize good scholastic performance, to the point that despite being a minority group, Asian students (especially the Chinese) disproportionately fill the rosters of American universities.

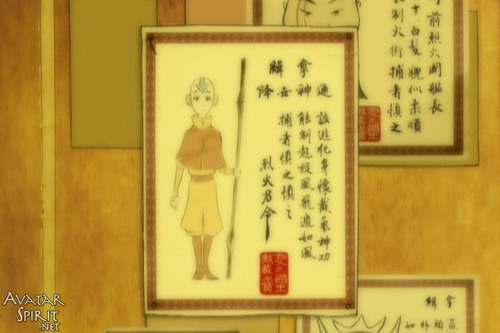

Much as in China, in the world of Avatar the most respected individuals are of high education.

#avatar#last airbender#ATLA#chinese history#imperial examinations#chinese culture#Hong Xiuquan#taiping rebellion

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pacifism and the Spread of Chinese Culture

Unlike the West which glorified warfare (a sentiment drawn from ancient Greek warrior epics and its heritage from the Roman empire’s military culture), China disdained the act of war. It is true that from China we get Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War,” the enduring manual detailing military strategy, yet China was for the most part was ruled by the literati, not by generals. War was certainly important to repel invaders and secure the nation’s borders, but ultimately Emperors sought peace, harmony, and balance with the world. Agriculture was the strength of a nation, not the sword.

From this sentiment comes the ancient adage, “An empire can be conquered on horseback, but an empire cannot be ruled from it.”

Instead China often chose to dominate by exuding its cultural superiority over the foreign nations: displaying its superior art, literature, history, philosophy, cuisine, fashion, medicine, mysticism, and rare goods. Even when China was invaded its culture allowed it to absorb its conquerers for a time when they weren’t expelled. This pervading effect of Chinese culture can be seen in how China influenced the artistic styles of other East Asian nations, such as Vietnam, Korea, and Japan.

Even today China’s power stems from assimilating the barbarians of the West.

One amusing detail of note is that some Koreans recognize the great impact of China, and apparently in a fit of culture-envy have produced the greatest East-Asian troll ever: Some Korean nationalists insist that everything Chinese came from Korea: Han calligraphy, Chinese herbalism, chopsticks, Dragon Boat festivals, even Confucius, are all said to be Korean in origin. Chinese people consider this a nationwide joke.

Lavish festivals similarly showcase and extend the culture of the Fire Nation.

To this day China demonstrates its cultural might through grand theatrical displays that few nations are capable of, or even willing to match. This not only shows its many millenia of heritage and its multitude of assimilated cultures, but the incredible ability to control and mobilize workers and resources in a highly efficient and effective manner.

Possibly the greatest example of this sentiment that one can “awe others into submission with culture” would be the journey of the great admiral Zheng He. A Muslim born in China’s Yunnan province, Zheng He lived when the Mongolian occupation of China (the Yuan dynasty) was in decline, and the new Ming dynasty (Ming meant “Brilliant,” a reference to the hope that the golden ages of the Tang and Song dynasties would be revived) was on the rise. As a boy Zheng He was made into a eunuch by the Ming officials, and sent to the Imperial court where he eventually became a trusted favorite of the Emperor.

The great naval explorer Zheng He.

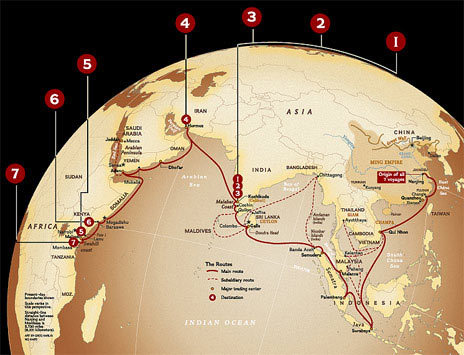

Because the Ming wanted to purge foreign influence and reestablish China’s central identity, the central government sponsored a series of naval expeditions to the far reaches of the globe. In contrast to European expeditions around the world these journeys were not to conquer, nor colonize, nor even to establish trade routes. Zheng He’s journeys were purely diplomatic, stretching from Egypt and the coast of Africa (perhaps even beyond the Cape of Good Hope according to some sources) to the West, and the Indonesian Islands to the southeast.

The estimated routes of Zheng He’s expeditions.

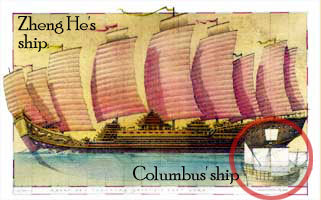

Grand armadas of “Treasure Ships,” the largest said to span the size of a football field, had holds filled with gold, silver, porcelain, and silk, all to be presented as gifts to foreign kingdoms to form diplomatic ties.

The massive treasure-ships that showcased the might of the Empire, many times greater than the puny little scouts sent by the West. However it is important to note that architecturally speaking, it is unlikely that these ships were truly of such a massive size.

There’s a Freudian joke buried in here somewhere.

Mountains of treasure flowed out in a grand program of cultural gift-giving, and in return China received awesome things like giraffes. I’m not being snarky here, the giraffe was a very big sensation when it was brought back to the Empire, since it bore a great resemblance to a mythical beast, the Qilin: a peaceful creature of good omens and prosperity that is so gentle it can only eat leaves after they fall from trees (rather than violently tearing them from the branches like asshole vegetarians). The discovery of the giraffe inspired shock and awe in the Imperial court, and the Emperor celebrated its arrival as an extension of his power.

Above: Giraffe brought back as a gift to the Emperor from the expedition to Africa. Note its strong resemblance to the mythical Qilin pictured below it. The giraffe’s hexagon-patterned coat resembled the “scales” of a Qilin, with matching horns and gentle vegetarian demeanor.

Sadly with the threat of barbarian incursions on land, subsequent Emperors decided not to fund further expeditions. Indeed, the later Ming Dynasty Emperors actually reduced the navy and instituted a ban on shipping, which ultimately fucked them since this reduced tax revenue, cut off their relationships with these foreign kingdoms, and resulted in the proliferation of pirates and smugglers which would prowl China’s seas and further inhibit Ming naval power. Some believe that these Emperors were jealous of the achievements that Emperor Yongle made by sponsoring these expeditions (if a dim memory serves, I believe the subsequent Emperors destroyed the great vessels). By smothering the Treasure Ship expeditions from most recorded history, subsequent rulers would not have to live in the shadow of Yongle and Zheng He. The 16th century Ming Dynasty was weakened as a result.

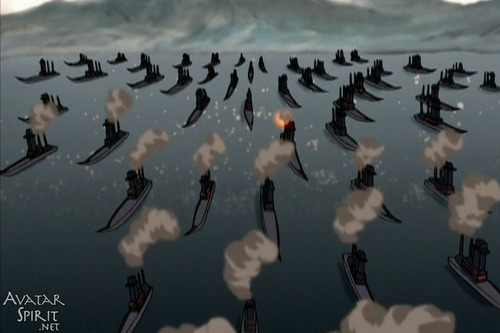

Control of the seas is of utmost importance to the security, economy, and power of a nation.

Never underestimate the power of a navy, the importance of diplomacy, or the significance of strong peaceful relationships with foreign powers.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chang'e

Welp, the Moon Festival is coming up next week so we might as well have a relevant Avatar cultural update! Happy Moon Festival, everyone!

Whereas Yang is masculine, projective, and hot, Yin is feminine, receptive, and cool. Siege of the North shows a great dichotomy of Yin & Yang in more ways than one, which barely need mentioning.

You rise with the moon. I rise with the sun.

Here, however, I want to discuss the tale of the Chinese Moon Goddess.

The tale of Chang’e has two versions, but they both end in the same way.

Version 1: Long ago the immortal Chang’e and her husband Houyi (a master archer) dwelled in the celestial realm. One day however, the Jade Emperor’s ten sons grew bored and descended to the mortal realm to frolic and play. Unfortunately their divine forms were each a radiant burning sun, and as they raced around the sky their horseplay caused the earth to scorch. The waters of the land evaporated, the soil became baked like clay, and the creatures of the world were sweltering and burning to death.

To fix this the Jade Emperor sent Houyi to the mortal realm to retrieve his boys. The archer called to the young gods, but they simply ignored his pleas. Now Houyi wouldn’t take any of this shit, so he nocked his arrow and slew the suns one by one, each sun snuffed out until he left only one to keep the lands warm during the day. This solution did not please the Jade Emperor at all, and so Houyi and Chang’e were banished to Earth.

The archer Houyi shoots down nine of the Ten Suns to save the world.

Houyi saw how miserable Chang’e was as a human, so he went on a quest to retrieve a pill of immortality from the Queen Mother of the West. She granted Houyi the pill, but warned him that only half was needed to become immortal. So Houyi hid it in a box and brought it home, warning his wife not to open it while he went out on an errand.

Unfortunately, one of Houyi's rivals heard about the immortality pill he had acquired, and confronted Chang'e at their home and demended it for himself. To keep the immortality pill away from him, Chang'e swallowed the whole thing herself. While half would make one immortal, a whole pill was too much immortality for a body to take, and this caused her to float off toward the heavens. Upon seeing this, Houyi was tempted to shoot her down to keep her from ascending further (how the hell this was to work is beyond me) but couldn’t bear to do it.

Chang’e continued to float upwards until she reached the moon, where she resides to this day.

Version 2: Chang’e was an immortal servant girl in the Jade Emperor’s celestial palace, when one day she accidentally broke a valuable vase. As punishment the Emperor banished her to Earth. It was here that she met the archer Houyi, who vanquished the ten suns as described above. However, this version paints a less charitable view of Houyi, who was more selfish and greedy.

After Earth was restored from the ten suns fiasco, Houyi commissioned an elixir of immortality to be developed out of the desire for his own divinity. Chang’e came across it, and swallowed the pill. Fearing for her life as Houyi chased her down, Chang’e leaped from a window and floated off to the moon.

Eventually Houyi would acquire immortality himself and become the Sun, and he and Chang’e would balance each other out as the celestial manifestation of Yin and Yang.

Luckily Chang’e wouldn’t be too lonely on the moon, as she would have as her companion an immortal Moon Rabbit who owns a mortar and pestle that he uses to pound out the elixir of immortality.

Yo, whassup.

The idea of a Moon Rabbit is drawn from an ancient Buddhist tale, where four animals were bringing food to an old man who was going hungry. The monkey climbed trees to get fruit, the otter brought fish, and the jackal stole meat and milk. The rabbit, himself eating only herbs and leaves, made the only offering of food he could by leaping into a fire, roasting himself so that the old man could eat his body.

To the rabbit’s surprise, he wasn’t burnt by the flames. As a reward for his immense act of generosity the rabbit would from then on live on the moon grinding medicine.

Some believe that the sweet little moon bunny does not pound out medicine using a rabbit-sized pestle with his teeny paws. Instead, he is said to be pounding out rice flour or mixing dough for delicious mochi.

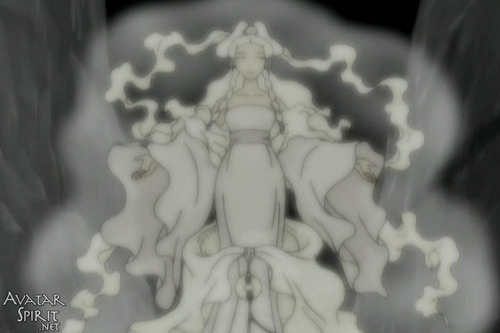

I’ve heard that a lot of people were confused by the ending of Siege of the North, in that they didn’t understand how Yue could become “a ghost.” This is a misunderstanding really… Yue’s transformation into the Moon Spirit is a direct reference to the story of Chang’e, who herself became the goddess of the moon. There has always been a certain element of loss to the story of Chang’e, since in a way her floating off to the moon is considered a sort of banishment: being unintentionally torn away from either her love (Houyi) or the home she always wanted to return to (Heaven). We definitely get that same impact with Yue’s sacrifice.

The Yin is strong with this scene since I always tear up like a woman when I watch it.

Yue’s transformation into the Moon Spirit is reminiscent of the story of Chang’e: loss, separation, and apotheosis. I’m probably reading too much into it, but I suspect that Yue’s own hair-loopies may be a reference to rabbit ears.

Of course, Chang’e is familiar to the West too. During the first Apollo-11 moon mission, the following conversation occurred between Houston and the Apollo-11 crew:

Houston: Among the large headlines concerning Apollo this morning there’s one asking that you watch for a lovely girl with a big rabbit. An ancient legend says a beautiful Chinese girl called Chang-o has been living there for 4000 years. It seems she was banished to the Moon because she stole the pill for immortality from her husband. You might also look for her companion, a large Chinese rabbit, who is easy to spot since he is only standing on his hind feet in the shade of a cinnamon tree. The name of the rabbit is not recorded.

Collins: Okay, we’ll keep a close eye for the bunny girl.

How Shyamalan changed it: I’m not sure I can say that Shyamalan “fucked it up,” since if a cultural reference is too obscure you might as well not include it and go with something with more emotional impact to your audience. On the other hand, this sort of reasoning was used to justify the whitewashing of Avatar in everything else so I’m hesitant to use it in this case.

In “The Last Airbender,” Yue lays down into the spirit oasis and dies (after that horrible “believe in our beliefs” line), the white in her hair flows over to the dead moon fish and her hair becomes black again. It’s a nice, intuitive effect, and I can’t blame a western audience for applauding this version as better since they found the whole “Yue Ghost” ending of the series to be too confusing and contrived.

Still, I can’t help but feel a bit pissed that this mythological reference was excised. Out of either ignorance over the cultural roots of Yue’s original death, or intentional director’s choice, this sort of cultural sterilization really bugs me since the original series was so deeply connected to East Asian history on so many levels. This was just yet another element that Shyamalan snipped away.

Oddly enough, despite Shyamalan’s fetish for “proper” pronunciation, Yue is still pronounced the Americanized way in the movie. “Yue” is literally “Moon,” but in Mandarin is pronounced more like “Reh,” with the fourth intonation. In any case:

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Holy crap. I would LOVE to see a fantasy animated series based on Native American cultures.

Worldbending | North America (Tarahumara; Hochunk; Tohono O’odham; Potawatomi.)

87K notes

·

View notes

Text

Qi and Martial Arts

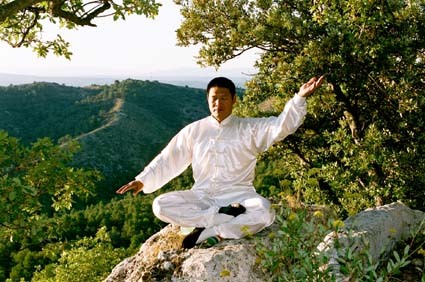

In parallel to a humoral paradigm of medicine, the Chinese believed in the concept of Qi: literally, “Breath,” or “Air.” Qi is the life-force or energy of the world, the flow of which is important to health, power, and even destiny. A proper understanding of Qi flow is considered critical for practicing Chinese medicine as well as martial arts.

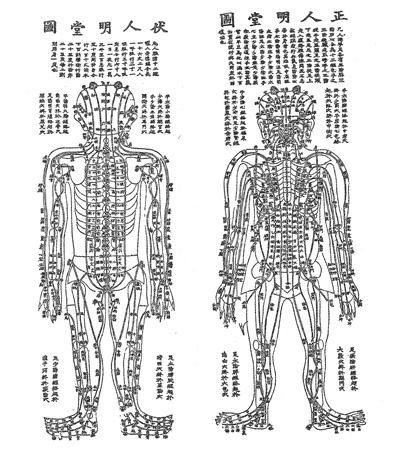

Qigong is the practice of manipulating the flow of energy in others for medicinal purposes, akin to an Eastern form of faith healing. Because Qi flows through a system of meridians like arteries and veins, blockage was believed to result in known sicknesses. By restoring proper energy flow (either through acupuncture or Qigong), it is thought that one could cure the disease. There also appears to be some relationship between Qi meridians and chakras, a concept borrowed from India.

When I was a kid my mother sent me to classes to learn this stuff, and lots of middle-aged Asian women would gather in formal sessions where more experienced practitioners would help “heal” those who weren’t themselves practitioners. When healing another, a qigong practitioner will usually sit next to the patient and place one hand on the wrist, one on the back, and meditate on the flow of stagnant Qi being expelled. When it’s “working” both practitioner and patient feel heat radiating from the practitioner’s hands, and the practitioner usually feels a sort of numbness in the extremities as stagnant Qi flows out, or when they wave their hands over the patient’s body to feel out the trouble spots. Frankly the benefits are likely just psychosomatic and these symptoms are probably just the result of biofeedback training.

Qi meridians dictate the flow of energy in the body, and can be manipulated for healing as well as harm. The healing ability that some Waterbenders manifest is based directly on qigong: the art of manipulating a patient's energy flow through a system of "meridians" to facilitate recovery. The first image is a traditional Chinese chart of Qi meridians. The second is a practice dummy that healers-in-training use in the Northern Water Tribe.

The study of Qi is also integral to martial arts in several ways. First, the flow of Qi is central to the practice of Tai Chi, which requires mastery of internal energy and breath. This is reflected in Waterbending, which requires one to feel the fluid “push and pull” of water.

Another major focal point of Chi flow in the body is the “triple warmer” region, three subdivisions of the thoracic cavity which act as “furnaces:” the source of energy transformation and metabolism. This is the root of Firebending.

"No! Power in firebending comes from the breath. Not the muscles. The breath becomes energy in the body. The energy extends past your limbs and becomes FIRE."

Third, martial artists whose styles emphasize hard strikes, great endurance, and immense strength must learn how to harness and focus Qi to the relevant body parts. By manipulating Qi in this fashion, coupled with severe endurance training, one can become resistant to the heavy blows, immense pressures, and high tensile forces. This is the basis of Earthbending, wherein practitioners can punch/kick through stone and take heavy blows without any damage.

Mastery of Qi control is also used to toughen the body against great stress. This is the basis of Earthbending.

One historical note of interest on this subject is the Iron Palm (and related Iron Vest) technique: the practice of conditioning one’s hands to become iron-hard so that they can endure heavier strikes and blows. This involves stuffing a canvas bag full of mung beans and having a session where you repeatedly strike it dozens of times each day. One added benefit of this is that as the mung beans pulverize, the powder seeps through the bag and is absorbed by the hands, which is believed to have a medicinal effect. After mung beans one moves onto filling the punching bag with gravel, then with iron beads. One must also apply Dit Da Jow after each session, a liniment that is supposed to support healing and recovery of the fists.

One variant of Iron Palm training involves striking into barrels filled with sand to toughen up the palms and fingers.

There are many romantic stories involving martial artists who have mastered Iron Palm. I remember my old Kung Fu teacher telling a story of a friend of his who once scared off a pair of robbers by ripping a brick out of a wall with his bare hand. One historical master I know of (but whose name I cannot remember- google fails me) is known to keep his fists in rigid condition by striking an iron plate he hangs on the wall a thousand times a day. His knuckles are heavily callused, but one smack from him can knock a person unconscious. This particular master, IIRC, took it upon himself to make citizens arrests of dozens of criminals in the 70s or so when weapons were banned in China, meaning he could only resort to his (heavily trained) fists. He was featured in a couple documentaries and a couple movies, I believe.

I tried training in Iron Palm myself when I was a teenager, but stopped once I started getting paranoid about nerve damage and fucked up bones. It’s not something to take lightly, though at least I was able to win some matches of Bloody Knuckles for a time.

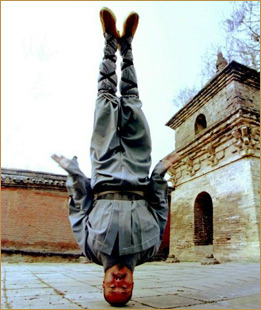

In any case, the conditioning doesn’t just focus on the fists. The Iron Vest technique is all about training the torso to resist blows. Some masters train their skulls and necks to the point that they can stand on their heads, unsupported.

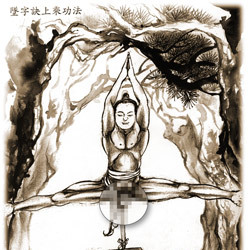

Some masters use Qigong to train… other parts… to be particularly robust.

Yes, this is exactly what it looks like.

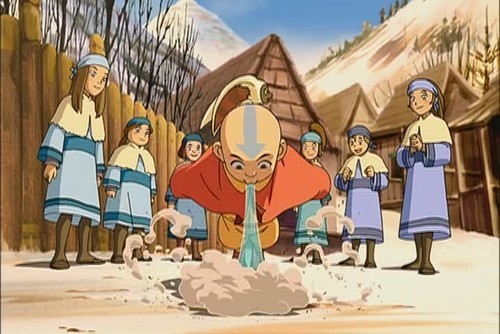

As for Airbending, the closest martial arts analogue is Qinggong: "the discipline of lightness," where balance training, climbing, and acrobatics are combined with the discipline of redistributing one's Qi to make the practitioner exceptionally quick and agile to the point that he is capable of balancing on small or narrow points, such as the lip of a large jug. Think of it as the ancient Chinese version of parkour. An exaggerated form of this is also seen in many modern martial arts films as "wire-fu."

One traditional Qinggong training technique in Ba Gua (the style of kung fu that Airbending is based on) involves running up a plank. Over time, the plank is set at a steeper and steeper angle, so that the practitioner can train himself to fight gravity and make steeper ascents. The mythology surrounding Qinggong holds that masters are so light that they can walk on walls and run unsupported on water.

Airbending, based on Ba Gua, also has some influence from Qinggong, the discipline of lightness. Note how Aang's movements (particularly when he jumps or falls) imply he's light as a feather. The delicate agility he exhibits is a common trope in modern Wuxia films.

Lastly, since Qi travels along specific meridians along the body, it is believed that striking the appropriate spots can paralyze an individual, or even kill him. This is where the romanticized “touch of death” comes from, and again legends abound of guys who pissed off martial arts masters enough that said masters used the Touch of Death on them. One legend describes how a brush of a palm against an individual’s body seemed to be ineffective at first, but days later the subject found a strange red mark where the master had touched him. Consulting a physician he met with dire news: the mark was fatal, and he would die only a week later.

When it comes to the film however, another notable change that Shyamalan made is that Waterbending is based on emotions more than anything else. Why? Not a fucking clue. As was mentioned in a deleted scene, “Water is the element change. It teaches us acceptance. Let your emotions flow like water.” Thus, if you aren’t in the right state of effusive emotions (like Aang since he was bottling up his guilt), proper waterbending is nigh impossible. Because of this a lot of points in the movie came off as maudlin, contrived, or just plain emo.

"I just thought about mom (while I was waterbending). Isn’t that strange?"

"You aren’t dealing with what happened to your people!" (only when Aang starts to feel weepysad over the Air Nomad genocide can he enter the Avatar State and make a giant ocean wave)

*sigh*

Additionally, most reviewers noted that the Bending in Shyamalan’s film seemed very discoordinated: there was little if any synchronization between the martial arts movements and the animation in a lot of cases. This has been described as “waving your hands like you’re casting a spell” or “doing a little dance to bend an element.” Here’s Shyamalan’s quote on exactly why:

But what it did, I think, was hone my timing on when I wanted the effect to happen based on movement and things like that. But it was “take”-specific for the animator, so the character would be doing part of a form and I’d say, “I’m not feeling the chi right yet, and when he releases the chi, that’s when I want the event to happen.” You know, that kind of thing. And it would be different for each actor and each take because I would believe it [only] at a certain moment. Part of it was just like pumping an air gun and the pressing the trigger was the moment the chi came out. And so I was like, “No, no, no, he’s still pumping and then there — there’s where he throws the element.” And we would look for it with each actor and each moment. Most of the background was all martial arts experts, so it was much easier. But with the actors I would spend a lot of time in the warehouse with them, getting them to understand what each move was if they weren’t martial artists, and what was meant behind each one.

There you have it. Shyamalan’s vision of Bending was less “elements move and are shot with the motion of the body” and more “you do these forms, backflips, and hand motions to build up your chi like you’re pumping an air gun, and THAT’s when the earth/water start moving.”

~*~*~ Fuck you Shyamalan ~*~*~ <3

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oracle Bones and Chinese Calligraphy

When I first studied Chinese history, one of the initial questions asked of our class was: "What is the difference between a language and a dialect?" Historians often answer that a language has the backing of an army behind it, and for the Qin dynasty this was very much true. Language is of profound importance to the Chinese since it was one of the great unifying features of China: a single written script enforced by the dictatorial Qin served to ultimately bind dozens of smaller, linguistically distinct nations together. Many of those dialects would otherwise be considered different languages, though they all share the same script. Try to get a person speaking in Cantonese to communicate with a person speaking in the Shanghai dialect, and you’ll see the difference. Thus, by standardizing the written language, the Qin was able to bind all the distinct subcultures of the surrounding kingdoms to him.

One very important point of focus for the show’s creators was thus the calligraphy. However there are many different calligraphy styles, many of which are variants on the Qin imperial system. To make their lives easier then Mike and Bryan hired calligraphy expert Siu-Leung Lee, who recommended several styles to be used.

Oracle Bone Script: For hundreds of years it was quite common for farmers to dig up “Dragon Bones” for medicine, grinding them up into powder for applying to wounds and mixing in potions. In 1899, a Qing dynasty official was sick with malaria and his friend sought some medicine for him. The man purchased a “Dragon Bone” at a local market and just as they were about to grind it up, the Qing official noticed that strange marks were carved into the surface. He soon realized that this was ancient Chinese writing.

Further research revealed that these bones dated back to the Shang Dynasty, the Chinese Bronze Age. Now China has shitloads of divination methods from I Ching to face-reading to psychic birds trained to pluck fortune cards from a box. One of the earliest divination methods was the use of what are now called “Oracle Bones,” which are either tortoise shells or the shoulder blade of an ox.

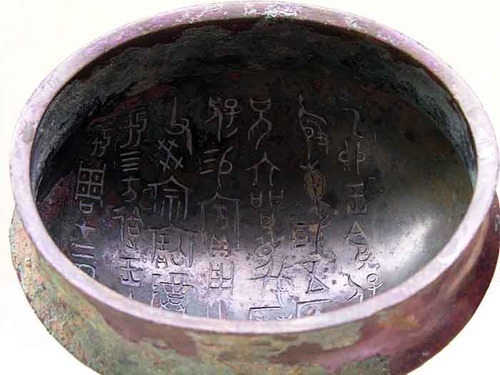

An Oracle Bone from the shoulder blade of an ox, dating back to the Shang dynasty, as far back as 3500 years ago. Note the descending lines of calligraphy carved into the bone.

The diviner would carve a message or question on the bone, drill a hole in a part of it, then insert a heated iron into the hole (I think they may have soaked the bone in water first as well). With the sudden intense heat, the bone would crack, and the radiating fractures would spread along the writing. The diviner would then read the cracks and interpret what they foretold. The method was actually quite systematic, because not only did the bones record the diviner’s concerns and questions, the diviner would often also inscribe whether or not the fortune came true and what was the final result before putting the oracle bone in storage.

Aunt Wu’s divination method using bones is based on the use of Oracle Bone osteomancy.

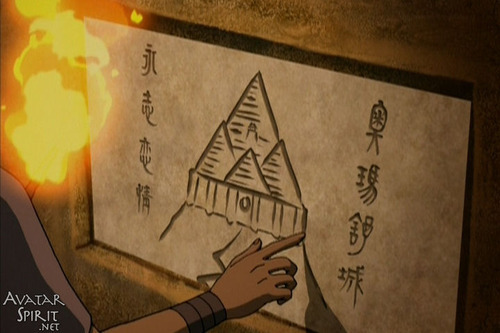

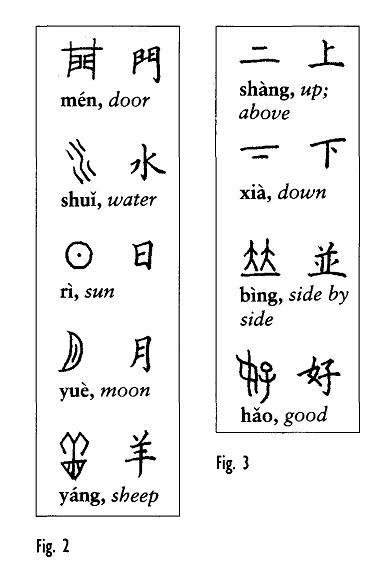

Through the Shang and Zhou dynasties or so, the Oracle Bone style of script (and related scripts) was still very pictorial in nature. The word “Eye” would be a sideways image of an eye. The word “Moon” would be a drawing of a moon. We see Oracle Bone and archaic script being used in Avatar on many occasions, when the animators want to portray an ancient site or a venerable legend, or simply for decor.

Writing from the Cave of Two Lovers, Zuko's dagger, and a Zhou-dynasty bronze of the pre-Qin era, 2500 to 3000 years old. Note the sinuous and more rounded lines, akin to cursive.

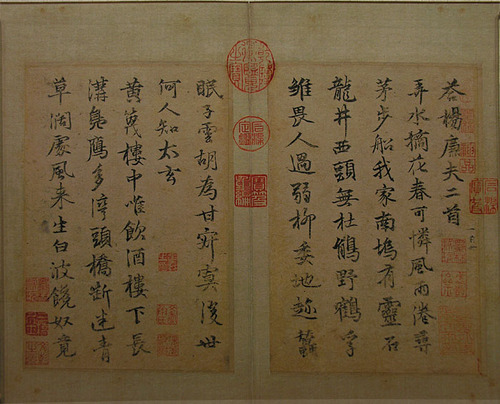

Traditional Style: Even up to the Qin dynasty the style was somewhat archaic, with sinuous lines and curves. Things changed as the Han dynasty took over, and the style became much more regimented and graceful, and would remain this way for the next two thousand years as “Traditional Style.”

Traditional style is the language of everyday use, from letters to posters to official court documents, and is also the most widely used style in Avatar.

Until the modernization efforts into making “simplified Chinese,” the traditional style from the Han era onwards was essentially unchanged. It is characterized by straight lines with slightly knobbed ends like bamboo sections, and graceful swoops of the brush. Stylistically it is much more regimented than Oracle Bone script. However because it evolved from the pictorial language of Oracle Bone and other archaic scripts, one can recognize how certain individual components (each with elementary meanings called “radicals”) can combine to form whole words.

The evolution of ancient script into traditional calligraphy. Many of the simpler words can be used as "radicals:" subcomponents of more complex characters. For example, the word on the lower right there is “Hao,” or “Good,” and contains the radicals for “Woman” and “Man” together. “Man” + “Woman” = “Good.”

The word “Guo” or “Nation” for example, consists of an internal radical for “weapon” and an outer radical of a large square, representing a wall enclosing it. Thus “Guo” shows what a nation is quite literally: it is military strength surrounded by a wall. The Chinese did so love their walls, without which a city was not a truly civilized city.

The word for “Nation” is the radical for “weapon” surrounded by a wall.

When writing Chinese calligraphy, one must also pay attention to the stroke order: each individual line must be written in a particular sequence, otherwise the resulting character will look warped or strange.

One more thing to note is that traditional Chinese writing is written up-to-down for a line, and right-to-left for each passage. This seems to be a very counterintuitive method for writing… after all, if you write from your right to your left, your sleeve or palm would smudge the ink. The art of Chinese calligraphy thus may seem rather awkward to a Wegsterner, as the calligrapher must pull up his sleeve with one hand and keep his grip on the brush a few inches away from the brush itself to protect the page from smudges.

This is an artifact of how Chinese writing evolved. In the most ancient days paper had yet to be invented. Instead, scribes would write each line top-to-bottom on a strip of wood. Once he was done with the line, he would place the strip on the table a little ahead of his writing area, and the strips would be arranged right-to-left as he finished with each. Once he was done he would wait for it all to dry, and then string them together and roll up the bundle.

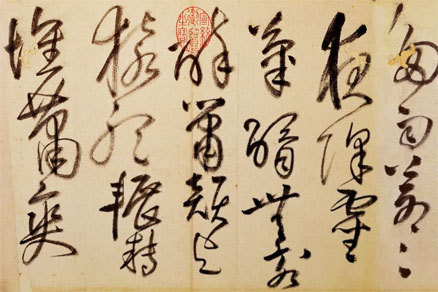

Grass Style: Of course, writing for the Chinese wasn’t just about communication. Calligraphy was and still is a high art, and any man of taste would have at least a few wall scrolls with a blessing or motto written by a master calligrapher. Oftentimes such wall hangings are written in Chinese cursive, or the “grass style.” This is typified by a certain spontaneity in writing, where fast swoops of the brush would produce stylized and elegant words. It is an exercise in pure art. You also can see this style of script imprinted on silk and other fabrics for decoration. I’ve even got a Japanese yukata decorated in grass script in a message wishing good health, and two shirts decorated in the same manner.

As an artistic style rather than a functional one, it is in the Grass Style of calligraphy that artists would prefer to tattoo “I Love Cock” on the shoulders of white boys. Traditional is more popular for this function however.

A little hard to see, but the writing on the screen behind Sokka’s right foot is in the grass style.

Of note also is the importance of poetry in China. Not only were words written with rhyme in mind, but as a tonal language Chinese poetry can also take on a musical quality. There are many factors in a work of Chinese literature: as a syllabic language homonyms are very prevalent, and thus puns and wordplay are a major feature of cleverness and humor. Metaphor also plays a remarkably strong role in crafting profound statements. The script is also very regimented and characters are written as blocks on a grid. This, however, can lead to dangerous territory.

Never insult a Chinese calligrapher when asking for a commission, because they can use these nuances to hide double entendres. Poems have been written where, if read “properly,” from up to down and right to left, sound quite nice, but if read backwards ends up to be some grave insult. One particularly cheeky client was too curt with one calligrapher, and upon receiving the wall scrolls was initially quite happy. Years passed before a visiting friend looked at the scrolls and burst out laughing. The owner of the scrolls asked what was wrong, but his friend was too embarrassed to say. It was only when he was about to leave that the friend recommended the owner rearrange the scrolls, and upon doing so the owner discovered a hidden message condemning the occupants of the household as idiots.

Where Shyamalan Fucked Up: It’s easy to see then why Chinese calligraphy is of deep cultural importance. It is a direct connection with the distant past and the heritage of the Empire. It is one of the highest and most nuanced arts in Chinese culture. It represents the unification of the Chinese people.

Shyamalan decided to give about 1 billion people a huge kick in the nuts by asking his artists to invent a random bullshit scribble-language that he pulled out of his ass that looks marginally Chinese. Fuck you, Shyamalan.

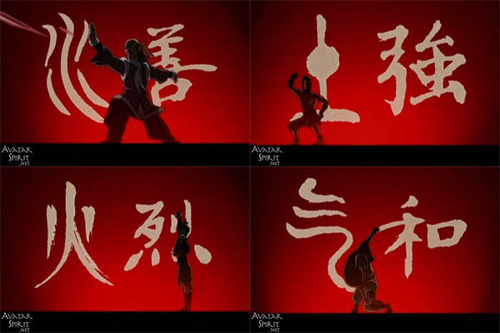

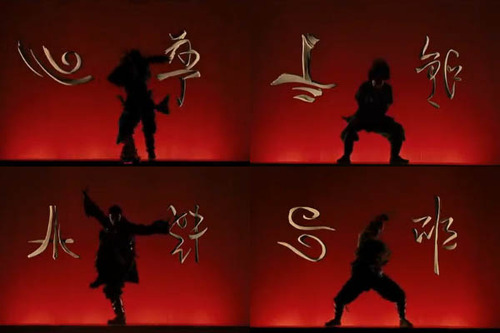

The series intro makes use of ancient script on the left of each screen (the elements), and traditional style on the right (a trait associated with each element) of each screen. "The benevolence of water." "The strength of earth." "The ferocity of fire." "The harmony of air."

The visual equivalent of "ching chong wing wong." Thanks for the offensive gibberish, Shyamalan.

“Eh, so long as white people don’t care, let’s just do something that looks Chinesey. It’s not like our audience can read it anyway.”

Also instead of the Oracle Bone thing, the Fortuneteller in Shyamalan’s shitfest is some wacky incompetent Jamaican lady:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=22MN9oPC7Pg

Double fucks to you, Shyamalan.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chinese Herbalism

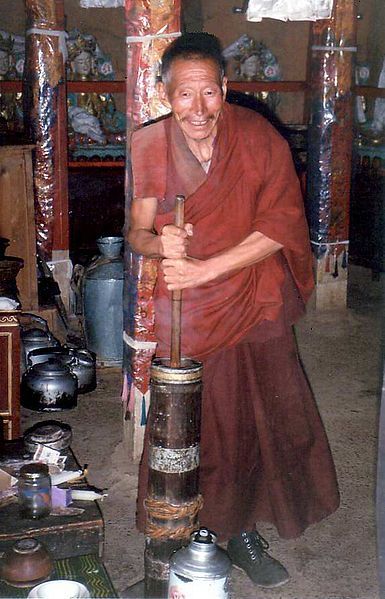

It is said that in the era of the San Huang Wu Di period and before the advent of civilization, the great Sovereign Shennong came to power. He saw how his people suffered from great sicknesses and lamented their notable lack of erections. Thus, he took it upon himself to alleviate these problems by personally tasting hundreds of herbs to discover their properties.

And so Chinese herbalism was born.

The great Sovereign Shennong, father of agriculture and herbalism and inventor of tea, samples hundreds of plants to determine their properties. You don’t want to know what this one does.

Much like the West the Chinese had a humoral understanding of medicine and believed that disease was caused by imbalances of these humors: sickness arises because certain organs are too hot, too cold, too moist, too dry. Herbs possessed these humoral elements and could bolster deficiencies and counteract excesses. Despite this bullshit foundation there are some herbal treatments that do have genuine therapeutic properties. Cotton seeds, for example, can be an effective male contraceptive. Ephedra was traditionally used for respiratory ailments, and its use in fact became quite widespread in the West as genuine medication, until it found to have to adverse side effects popping up from casual use.

“You’re insane, aren’t you?”

“That’s riiiiight.”

Chinese medicines tend to be composed of powerfully concentrated (and usually very bitter) infusions of many herbs. Yet simpler home remedies are also quite common. Parents often treat children suffering from colds with a very spicy “tea” rich with fresh ginger and brown sugar (though boiling ginger with coke is a more modern remedy). Mung bean soup, served hot or cold, is considered cleansing and diminishes “huo chi,” excess heat (perhaps a reference to inflammation).

The border between Chinese cuisine and Chinese medicine is a bit blurry. One is supposed to avoid spicy foods when you have a cough, cold foods when you are phelgmey. Indeed, the idea of drinking ice water is a very foreign concept in China, as it’s believed that icy cold beverages are bad for your health. I once had a dinner guest chide us for drinking ice water because they felt it would lead to headaches and stomach cramps. One of my buddies has a Taiwanese girlfriend who was shocked when she saw how people would casually drink ice water in restaurants here in the States. Additionally, many restaurants advertise soups which contain dozens of herbs and spices which are not only tasty, but also happen to promote good health. I once had a fantastic Hot Pot meal in Taiwan like this. My mom also makes a very tasty chicken soup with slices of ginseng and these little red berry pods, for good health.

“Suck on them?!”

In principle the idea of sucking on Frozen Wood Frogs isn’t all that strange (though I suspect the Wood Frog thing is more a reference to bufotenin, the toad-skin hallucinogen). Herbalism in China wasn’t limited to plant matter, and included plenty of animal parts like ground-up bones, dried seahorses, and some pretty horrible things like human urine or feces. Probably the most notorious of herbal treatments would be the aphrodisiacs that are so popular in China. Dozens of herbs and endangered animal parts could go into “Master Yen’s Auspicious Happy Fortune Boner Pills.”

I’ll leave you with this image.

The Guo-Li-Zhang Penis Restaurant in China serves a large variety of shlong-derived dishes meant to provide its customers with magnificent erections. Here is a plate of tasty penis cold cuts.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chinese Spirituality Part 2: Three Schools of Thought

There was a great deal of intellectual expansion in the Zhou Dynasty, and while a lot of literature was preserved as “The Classics,” three schools of thought held the biggest influence over Chinese beliefs: Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism.

Taoism: Often translated as “The Way,” it is an abstract set of metaphysical beliefs with an emphasis on alchemy and the quest for immortality. This is where you get the concept of Yin and Yang. Taoism didn’t emphasize a system of ethics so much as it described a natural flow of the world such that human actions result in harmony when they work in balance to nature rather than in conflict with it. This is carried over as the underlying story of Avatar: In trying to assert its dominance as the singular “superior element,” the Fire Nation has disrupted the balance of the world and created a long era of war and strife.

As the Avatar, Aang is in part representative of the Taoist pursuit of balance, where his duty is the understand, restore, and maintain the natural balance of the world.

Because a Taoist wanted to work in harmony with nature there was a great need to understand the world. This was the root of Chinese interest in alchemy, divination, and astrology. One of the greatest goals for a Taoist was immortality. Many Immortality Pills were developed, some of which contained poisonous compounds like mercury or arsenic (as you might recall, the First Emperor of Qin died due to mercury poisoning), and those credulous enough to consume them often met with results as expected from the ingredients. Of course, this was sometimes written off by the alchemist as “Ah but after you die, the pill will take effect and your soul will be reborn as an immortal.” Clients had difficulty obtaining refunds if this was not the case.

Confucianism: In contrast to Taoism (which sought to understand man’s relationship with nature), Confucianism is concerned strictly with ethical and political theory and how human beings should relate to one another. Born in the Spring and Autumn era, Confucius saw a great deal of war and strife and sought to develop a philosophy that would bring peace and harmony to the world. His was a school of thought that survived the Qin censors, and its main emphasis was the importance of the family unit and the duties and obligations thereof.

This reflected not only the obligations of direct blood kinship, but was an analogy to the government and to the greater society as a whole. The Emperor was considered the great patriarch of the Empire, for example. When children play together they often refer to each other as “big/little brother” or “big/little sister” regardless of blood kinship. Even among criminal gangs the subordinates will address their superiors as “Da Ge,” or “Eldest Brother.” You also see this sort of reference to familial relationships (even outside of blood kinship) in Korea and Japan.

"Inu no nii-chan!" Even though the kid isn't related to Inuyasha whatsoever, Souta nonetheless refers to him as "Doggy Big Brother."

Central to Confucianism is the concept of "shao shuen," or "filial piety." Is it the virtue of obedience, respect, and deference to one's elders. Chinese kids are taught to cultivate this virtue from an early age. For example, at the dinner table the grandparents are traditionally served first, then guests are allowed to take their share along with very young children. Finally, older children and the adults are left to serve themselves. Elders are also spoken to using special pronouns: the word "ni" ("you") is used to talk to any old schlub on the street. However, it is traditional to use "ning" to one's elders: more formal and respectful, though a little archaic these days.

In short, there is a certain separation between the older generation and the younger, and there are many unspoken and unwritten rules as to how one treats one's elders with respect.

This is of ultimate relevance in “The Storm” as Zuko represents the filial son of the Fire Lord: ever loyal, trying his best to please his father. In showing disrespect in Ozai's war room, Zuko believed he had broken the sacred covenant between Father and Son, and now seeks to “restore his honor.” In this way Zuko demonstrates some very heroic aspects. His goal isn’t glory, fame, or power. He simply wants to return home and earn his father’s love, because he feels that somehow he has disgraced himself. Stories like this are incredibly appealing in Chinese culture, and East Asian cultures in general, especially when they involve the complex interplay of loyalty and treachery where one must ask “What does it mean to be loyal to one’s patriarch?” “Does a father figure deserve such devotion in the first place?” and “How do I maintain my honor when my dad is some stupid crazy asshole?”

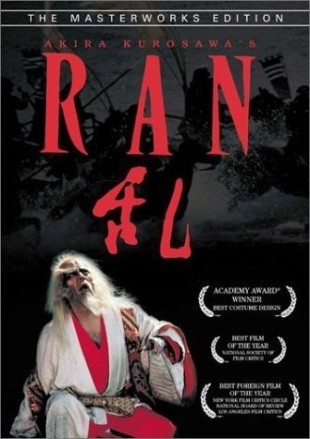

The Japanese film “Ran” and an image from a Chinese adaptation of King Lear, both inspired by Shakespeare’s classic play involving the fuckwit of a dad Lear, his two treacherous daughters, and the one good one that still loves him despite him being a fuckwit. The calligraphy painted on the forehead of Lear in the second image is “Wang,” or “King.”

One detail of note is the sanctity of the body in Confucian teachings. In Chinese culture the human body isn’t so much a vessel for the individual. Instead, in a way it’s considered a gift from the parents and ancestors. Mothers sometimes tell their children, “Take care of your body. It is the flesh I gave you.” It sounds a bit less creepy in Mandarin.

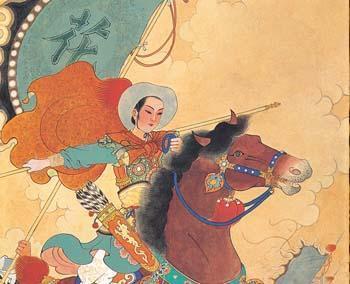

Another popular tale involves Hua Mulan, who joined the military in the place of her father who was too old to fight.

Thus, traditional Han Chinese never engaged in tattooing, because it would be vandalizing something your ancestors gave you. Even when executing a criminal it was considered more merciful to strangle them to death than behead them, even though the former was slower and more painful. This was because unlike decapitation, strangulation kept the body intact so that it might be returned to the earth (and to one’s ancestors) whole. There were no autopsies of course, which hindered the development of Chinese medicine. Even to this day medical students in China do not study cadavers in anatomy courses because traditional Han Chinese would never donate their bodies to what they saw as a violation of something sacred. Up to a few hundred years ago, even cutting one’s hair could be considered a rejection of one’s ancestral line, or a grave insult to the parents. This was a very big deal, and I will be referring to this much later on.

In this light, the fact that Fire Lord Ozai scarred his own son is very profound. Burning a young boy is bad enough in any sane culture, but doing so to one’s own son, when the body is the sacred vessel given by the parents, implies heavily that Ozai doesn’t even think of Zuko as his own flesh and blood.

Zuko, the dutiful son, is an exemplar of "shao shuen," the Confucian virtue of respect and obedience towards one's elders, though taken to an extreme.

Buddhism: Following the Qin was the Han Dynasty, which was built on the foundations that Qin laid out. It was the first Golden Age of Imperial Chinese history, and it was from here that the Han ethnic majority gets its name, as well as the Chinese name for calligraphy, Hanzi. Yet as all dynasties do the Han fell into decline due to internal power struggles (eunuch advisors getting grabby for power) and revolts from without. In this era of strife Confucian ideals didn’t seem to be enough to handle the political and economic troubles of the world, and Buddhism (imported from India via the Silk Road) began to grow popular as a form of spiritual escapism.

The Air Nomads are based heavily on Tibetan Buddhists.

Buddhism is the quest for inner peace by detaching oneself from the world, breaking the cycle of reincarnation, and attaining enlightenment where one’s spirit would forever exist far past the joys and pains of the world. Yet while in the West practitioners of Christianity seek salvation and a return to God, many devoted Buddhist practitioners felt that the opposite was the path of a true Buddhist:

“Great master, I wish to know what will happen when you die.”

“Why, when I die I will go to Hell, of course.”

“But you are a kind and gentle monk! Why would you possibly go to Hell?!”

“If I did not go to Hell, how could I possibly teach you when you arrive?”

Many Buddhists felt that one’s own salvation was not enough, and that instead they had a duty to help others find salvation as well. This was the goal of such monks who would willingly enter Hell (who else could need salvation more than those suffering as the damned?) as well as Bodhisattvas, who are on the edge of Enlightenment but refuse to cross, instead lingering behind in a semi-divine state to aid others on the path to inner peace. Their duty is to the world, not to their own spiritual progress (again, Hint!).

East Asian spirituality and philosophy also glorified in paradoxical thought. One such story involves a philosopher-linguist who rode up on a white horse to a gatehouse:

“Sir! Horses are not permitted past the gate!”

“Don’t be ridiculous! A white horse is not a horse!”

The actual statement was “Bai Ma Fei Ma Yeh,” which expressed the idea that “White Horse” is in a different conceptual category as “Horse.” As a result the philosopher rode past a very flummoxed gate guard. This sort of paradoxical reasoning is the source of the Buddhist Koan, which is a statement that cannot be understood by reason. Rather, their meaning is felt through intuition.

So many hands, and not a one to wank with.

Despite the fact that Buddhism became quite popular in China, in some dynasties it was vilified as a subversive cult. This is because Buddhism emphasized asceticism and detachment from the natural cycle of having children and raising families (a most worldly concern indeed), putting it directly at odds to the Confucian ideals which were so central to Chinese culture and the workings of the Empire.

Yet over time many Chinese grew to respect the Buddhist sense of inner peace and the freedom of spirit one cultivated through its practice. In fact, the Buddhist ideal of enlightenment was very close to the Taoist sense of “Wu,” or “Emptiness,” and these schools of thought comingled quite nicely. Buddhist practitioners learned to find contentment in whatever lot that life hands to them, whether it be wealth or poverty, sickness or health. Iroh can be thus be considered a strong manifestation of Buddhist and Taoist wisdom: he tries to teach Zuko to find peace and understand the path of his own natural destiny rather than the destiny that others may try to force on him. Jolly, friendly, and free of concern or hatred, Iroh tries to show others how to enjoy the simple pleasures in life rather than obsess over what may be unattainable.

Iroh’s possesses a deep sense of peace with himself and who he is, no matter what his situation. Others would be proud, standing stiff against the winds of destiny and end up breaking like fragile trees in the storm. Iroh on the other hand is humble and kind, and knows how to bend with adversity and flow with what he encounters. As the ideal Buddhist/Taoist he tries to teach others to do the same.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chinese Spirituality Part 1: Eastern Mysticism and the Underworld

I wrote this update in preparation for “The Storm,” but this part got too long and tangeatal. So I’m just putting it here for kicks.

Chinese religion is quite different from the modern Western sense of religion, as the East doesn’t have quite so stark a separation between the natural and supernatural realms. It’s important to keep this in mind and not let Western sentiments trickle through when studying Eastern mysticism. For example, the Japanese term “Youkai” is often translated to “demon” or “ghost,” which has certain alien connotations from the West that don’t really apply very well. I once overheard a girl gushing about Inuyasha to her mother saying how it’s a story about a demon and blah blah blah, and her mother seemed a little shocked. “Why would you watch a series about demons?!”

In a way Chinese religion was shamanistic: one individual or group of individuals (often the Emperor) was in charge of annual rituals in order to bless the Empire for peace, good weather, and bountiful harvests. Kinda like the Avatar, who is supposed to be the link between the Spirit World and the world of Man. Note that in East Asian cultures, spirits weren’t believed to be as otherworldly as we see in contemporary Western religion. In many ways the spirit world was believed to overlap with ours, as it was believed that climbing the right mountaintop or exploring the right cave could lead to dealing with spirits. Xi You Ji is chock full of nuggets like this. This may also explain Iroh’s journey to the Spirit World, perhaps seeking his lost son Lu Ten as Orpheus sought his wife in Greek myth.

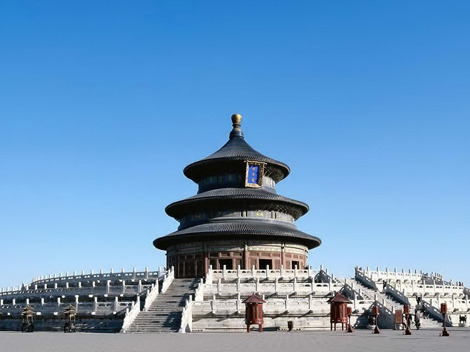

The Temple of Heaven in Beijing was one of the centers of Imperial worship in the Ming and Qing dynasties, along with the Temple of the Sun, Temple of the Earth, and Temple of the Moon.

Spirituality wasn’t limited to a caste of clergy either: individuals were expected to engage in ancestor-worship and make offerings on their own. I guess the best that can be said is that the transition between the world of man and the world of spirits is a lot more fluid, and the divine wasn’t considered to be all that different from the material, especially since it was believed that the proper rituals and substances could transform one into a divine being.

In fact, not only does the mundane world contain aspects of the spiritual. The spiritual world could contain aspects of the mundane. One such example would be that since the Imperial Bureaucracy which ran the Empire was very familiar to the world of man, the ancient Chinese naturally assumed that otherworldly realms functioned the same way. The realm of the dead was itself a bureaucracy headed by Yan Luo Wang, on assignment there at the command of the Jade Emperor. His duty was to ensure that the underworld was run in an efficient, orderly manner and that punishments and rewards in the form of nice reincarnations were issued properly.

Yan Luo Wang acting as the judge of the underworld, with its ten districts sorting mountains of paperwork for the dead.

Oftentimes the underworld paperwork was a bitch, and errors cropped up occasionally. There is one story of a man who had been collected for death, but once he arrived in the underworld the officials discovered that he was taken prematurely due to a clerical error. They apologized, then sent him back to the land of the living much to the shock of his mourning family. Sun Wukong was said to have descended to the underworld, and after driving off the divine guardians Niu Tou (Ox Head) and Ma Mien (Horse Face), he scribbled his name out of the official ledgers, as well as the names of all his monkey followers, so that from that day on they were immortal (The Monkey King was like, super duper immortal).

In funeral ceremonies or the Chinese Day of the Dead (Qing Ming Jie) it is customary to make offerings of food and burn “Hell Bank Note” money or folded gold paper ingots for the deceased to use in the underworld. This ultimately has the effect of decimating the Underworld economy due to massive hyperinflation, as the dead must now truck around wagonloads of bills with the value of “100,000,000” yuan for a couple of apples. Despite this, children find the festival highly amusing as this is the perfect opportunity to burn stuff with their parents’ approval for once.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xi You Ji: The Journey to the West

Much as the epic of King Arthur had a profound influence on literature in the West, China had its own ancient epic whose influence would permeate Eastern literature for centuries. This would be Xi You Ji (“The Journey to the West”) which details the adventures of the Monkey King and his travels with the Tang monk.

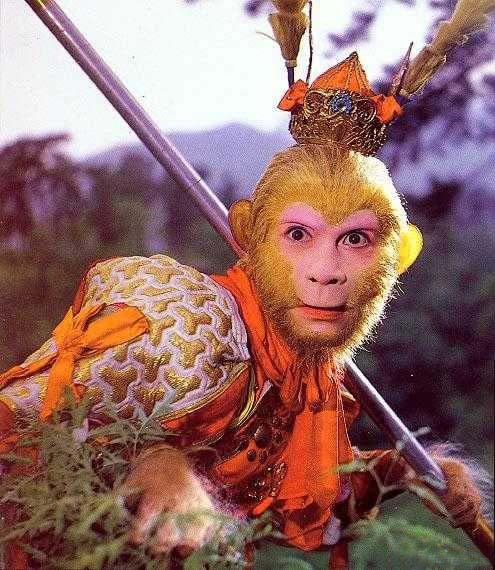

Written in the vernacular, Xi You Ji became a hit in the late 16th century and is still widely read. As a kid, we would read simplified passages of the epic in Chinese School, and every student would be as familiar with the tale as most Westerners are with the Bible. So profound was the influence of the novel that we still see its influence to this day in anime, live action TV shows, and movies.

Screenshot from a live-action TV series based on Xi You Ji that I enjoyed as a kid.

The main protagonist in the epic is the Monkey King, Sun Wukong. Born from a massive stone from pure primal force and chaos on the Blossom-Fruit Mountain (Hua Guo San), Sun Wukong immediately earned the respect of the tribe of monkeys there. He was cocksure and arrogant his entire life because he was stronger, smarter, and faster than anyone, and was overall an entitled little shit. His monkey minions addressed him as Mei Hou Wang, or “Handsome Monkey King.”

Of course bossing around a bunch of monkeys can only be fun for so long, so Sun Wukong decided to leave the idyllic mountaintop and travel the lands of mankind seeking better, more awesome things. In his travels he met the Taoist immortal Bodhi, who took him in as a disciple and taught him the ways of sorcery. Sun Wukong became so adept at magic that, entitled little shit that he was, he began boasting about his awesomeness. Bodhi immediately exiled Sun Wukong.

Sun Wukong continued his adventures and acquired the Grand Metal-Bound Cudgel, an immense 8-ton staff originally used to measure the depths of the oceans. This was retrieved from the palace of the Dragon King of the Eastern Sea and it could grow or shrink as Sun Wukong wished. He was able to wield it due to his immense strength, but when not in use he’d shrink it to the size of a needle and tuck it behind his ear. He also beat the shit out of the dragons of the four seas as well as an assortment of entities from the underworld.

Of course the Dragon Kings and the gods of the underworld wouldn’t abide by this crap, so they approached the Jade Emperor (ruler of the Heavenly Bureaucracy) and pleaded with him to do something about this troublemaker. Hoping that some responsibility would help the Monkey King settle down, the Jade Emperor gave Sun Wukong a position in his palace… as the royal stable boy.

I once heard an old story detailing how while he was in Heaven, the Monkey King greatly enjoyed one of the celestial foods only available to the gods. This culinary treat was known for its richness of flavor: Garlic. Of course he could hardly leave this tasty morsel behind, so he brought it to Earth by smuggling it past the gates of Heaven on his person, in a manner that is hardly to be spoken of in polite conversation, but suffice it to say that this explains garlic's pungent quality.

(He hid it in his ass)

Now at first Sun Wukong was pretty impressed with himself, but once he realized he’d been made a laughingstock he threw a huge tantrum and declared himself the “Great Sage, Equal of Heaven,” then wrought havoc in the heavenly kingdom first by setting the celestial horses free. Since he was too powerful to pacify with force, the Jade Emperor decided to give Sun Wukong a more honored position as the divine guardian of an orchard where the Peaches of Immortality grew.

Unfortunately, they neglected to invite him to a royal banquet.

Again throwing a shitfit Sun Wukong decided that if he couldn’t eat all that tasty spirit food, he’d devour all the Peaches of Longevity instead. The real pisser is that they only ripened once every three thousand years, and the celestial hosts were waiting for them to be juuust right. Sun Wukong then stole Lao Tzu’s Pills of Immortality and guzzled them as a chaser.

Go ahead. Eat it. It’ll do nothing to fill the emptiness inside.

Okay, now the Jade Emperor was pissed. This time there would be no mercy, and the Emperor sent 100,000 celestial warriors against Sun Wukong. Though he defeated every single one, he was eventually captured and sentenced to death. Every attempt to kill Sun Wukong failed since he’d eaten every immortality elixer available, so as a last resort the hosts of Heaven stuck him in Lao Tzu’s “Eight-Way Trigram Cauldron” to boil him down to the elixer of immortality. This had an unintended side effect, as when the cauldron was opened, Sun Wukong leapt out more powerful than ever.

Gnashing his teeth in frustration the Jade Emperor appealed to the last authority available, Buddha himself. Calmly Buddha approached the Monkey King and made a wager that Sun Wukong couldn’t leap out of Buddha’s palm. Now, Sun Wukong knew that he was adept at cloudwalking, so he took the wager and leapt to the ends of the earth. There he found five pillars, and to prove that he’d been here Sun Wukon vandalized the pillars and urinated at their base.

Well, turns out those pillars were Buddha’s five fingers.

At this point Buddha trapped the Monkey King under a mountain for five hundred years as punishment, and once he was freed by the goddess Kuanyin he became the disciple of a Tang Dynasty monk. This time he would be bound by a crown that could cause immense pain if the monk repeated a mantra, and thus the Monkey King was tamed. From this point on he would travel and protect the monk on his journey to India to retrieve the scriptures, along with a lecherous warrior pig-man and the Sand Friar. Despite this the hosts of Heaven would forever remember his power, and still refer to him as “Great Sage” when addressing him.

There’s a lot more to be said here but I’ve already gone on long enough on the juiciest bits. Needless to say there are a lot of parallels between the Monkey King and Avatar:

1 - Both the Monkey King and Aang are precocious tricksters.

2 - Both the Monkey King and Aang wear yellow as their predominant color (yellow and orange are Air Nomad colors, the Monkey King acquired a set of golden chain mail in his adventures).

3 - Sun Wukong and Aang both carry staves as their main weapon.

4 - Sun Wukong and Aang were both trapped for generations before being freed.

5 - The Tang Monk’s protectors include a hideous lecherous pig-creature. Likewise, we have the guttonous and (initially) misogynistic lovebender Sokka.

6 - As an Airbender, Aang can fly and leap to great heights. The Monkey King is likewise graceful and a master of the cloud-step.

7 - The Monkey King is adept at shapeshifting, a master of the 72 Transformations. Likewise, Aang is a master of disguise.

8 - Once they commit themselves to their missions, Aang and the Monkey King both (more or less) become tamed, accept their responsibilities, and become enlightened.

In fact, you might recognize the influence of Journey to the West from a lot of anime:

Dragonball: A story about a monkey-tailed, mischievous kid who wields an extending staff and can travel by riding on a cloud.

Inuyasha: A story about a wild youkai who is trapped for decades on a sacred tree, eventually freed and tamed by a priestess with a necklace that causes him great pain if she repeats a mantra. Wields a blade that expands in size and one of their companions is a lecherous monk.

Naruto: A story about a cat-faced fox-person thing that is a prankster and is himself the vessel that imprisons a troublesome, havoc-wreaking spirit. Also, poopy humor, which Xi You Ji also openly embraces.

Saiyuki: Basically a modern Japanese retelling of the epic.

Now as a final note, we must recognize that once again this is another thing that Shyamalan stripped from the film. Ever since Xi You Ji, the fun-loving/arrogant trickster-hero has become a very common trope in Eastern stories and is often considered an integral component of good fantasy. Shyamalan decided to make Aang into a dour, more “grounded” and sober character. He’s pretty much shat over this ancient literary device. Fuck you, Shyamalan.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beginnings of the Empire: The Qin Dynasty/The Fire Nation

The earliest days of pre-Imperial Chinese history (as traditionally held) can be summed up in short for some basic background:

San Huang Wu Di Period (The Period of Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors – before 2100 BCE): This period is firmly in the category of myth-history. Long-lived and godlike entities developed the core elements of civilization (agriculture, writing, the compass, herbalism, etc) and ruled over the core of China.

The Xia Dynasty (2100-1600 BCE): The neolithic era. The Xia isn’t truly a “dynasty” in and of itself, because there wasn’t a centralized system of governance. A multitude of tribal kingdoms existed in these Stone Age societies. Some of the artistic styles of this period would, however, integrate and develop into the general Chinese aesthetic sense, such as the love of intricate and delicate forms and the reverence of Jade as a sacred/mystical substance.

The Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE): The bronze age. Many of the artistic forms developed in the Xia carried over into the Shang dynasty. Two extremely important elements should be noted from this era. First, the development of highly decorated bronze vessels which were composed of modular components and were constructed in an assembly-line fashion. These were often used for ritual purposes. Second is the use of “oracle bones” for divination purposes, which also act as the first written record of Chinese history. I’ll post about this a bit more when we get to The Fortuneteller.

Left: Xia Dynasty pot. Right: Shang Dynasty bronze vessel. Some of the Xia pottery/stonework styles became incorporated into Shang Dynasty bronzes.

The Zhou Dynasty (1045-256 BCE): In short it’s probably best described as the “feudal era.” The Zhou propagated the idea of the “Mandate of Heaven:” the idea that a dynasty serves to rule only when it has the favor of destiny. If the Emperor does not serve well or does not perform the appropriate rites and offerings, the empire may lose the favor of fate and collapse through rebellion or natural disasters. This is often used to justify conquest ex post facto: “See the previous dynasty before us? Yeah we kicked their ass because they lost the Mandate of Heaven, and the fact that they lost to us proves that we possess the favor of destiny and the right to rule.” Eventually the Zhou collapsed and devolved into a long period of division and conflict known as the Spring and Autumn era and the Warring States period. The Zhou is where we really begin to transition from myth-history to actual history.

The Qin Dynasty (221 BCE-206 BCE): This is where the relationship to Avatar really comes in, and what the Fire Nation was based off of. Those of you who have finished the series will probably pick up on the parallels.

The Qin kingdom rose to power in a time of strife and upheaval. It was a heavily militaristic society, built around the school of Legalism which emphasized rigid, brutal adherence to order under the assumption that humanity was inherently selfish and wicked. The ruler of the Qin (known as the Tiger of Qin) was a feared and hated tyrant, and began a brutal war of unification to bring the surrounding nations to heel by sword and arrow. Once this was done, the King created a new title, naming himself Qin Shi Huang Di (the title Huang Di is the same as the combined words “Sovereign” and “Emperor” from the San Huang Wu Di period, and would become the official title of subsequent god-emperors). Donning a veil of stars, he was now referred to as the official Son of Heaven.

Qin Shi Huang’s war of conquest can be likened to the war started by the Fire Nation. The cap with the dangly beads in front of it is supposed to be the “Veil of Stars” worn by the Emperor representing his status as the Son of Heaven.

Rule by power alone, however, doesn’t make a unified nation.

Before the conquest the nations that stretched across East Asia were composed of a multitude of different cultures. The Qin obliterated these differences, enforcing a dress code, standardizing currencies as well as weights and measures, and conforming the writing system that would become the modern Chinese language. He also commissioned several large construction projects: the first Great Wall, as well as a system of roads throughout the Empire.

One thing that subsequent historians would never forgive the Qin for though was the burning of the classics. Yes, Qin Shi Huang Di was a book-burner, an advocate of a thought police society, and a historical revisionist. In order to unify all political and intellectual thought, he committed to the flames any texts he found subversive to public order, commanded almost 500 scholars (some say 1200) be buried alive, and decimated the Hundred Schools of Thought (Zhu Zi Bai Jia. Bai Jia literally means “Hundred Houses,” which represented the era of intellectual expansion that occurred in the Zhou dynasty). Only histories written by the Qin would be taught.

This couldn’t last long however. In the middle of his war of conquest, the then-King of Qin was beset by assassins from the Kingdom of Yen who came disguised as diplomats. In a surprise attack they were able to get within a few paces of him before his guards could save his life. This was a pivotal event, because it catalyzed his descent into paranoia and mental instability.

For the rest of his life Qin Shi Huang Di became excessively paranoid over his wellbeing, and obsessed over the idea of immortality. He had conquered the known world, but all of this power meant nothing if he was going to age and die. Qin Shi Huang Di consulted alchemists for potions of longevity and sent expeditions to the East to retrieve the Elixer of Immortality from the sacred mountains where dragons and spirits lived. Ironically, this obsession was precisely what drove him to an early grave.

Though Firebender armor seems to be styled more like Japanese Samurai armor, there is a lot of similarity between Fire Nation clothing and Qin imperial fashion. Left is Qin Shi Huangdi, First Emperor of Qin. Iroh is to the right.

At the recommendation of alchemists, Qin Shi Huang Di began to consume a mystical substance that was believed to have properties conferring the quality of Chan Sheng Bu Lao (“Long Life and Agelessness”): Mercury. Alchemists to the West also believe mercury held mystic properties, but the Imperial Alchemists Qin had hired apparently developed a way to complex this metal with compounds making it more easily absorbed by the body. Qin consumed mercury pills frequently, which only fueled his dementia and sped him towards an early grave.

Qin Shi Huang Di died in the middle of a journey to tour the Empire. It is said that his advisors kept two carts full of rotting fish ahead of and behind his carriage to cover up the stench of his decaying body (it was summer), hiding the Emperor’s death as they rushed to the capital.

His son would fail to secure the throne. Though Qin Shi Huang Di declared that his empire would last 10,000 generations, the Qin dynasty lasted only 15 years. Despite this, its process of forced unification provided the backbone for what would become the Chinese empire.

Qin Shi Huang Di is said to have been buried in a grand tomb, his sarcophagus in the center of a topographical map of the known world, where the rivers, lakes, and seas of the map were hollows filled with mercury.

The initial sketches for the Fire Nation showed a more Japanese style to it. Here’s a picture of soldiers from the pilot episode compared to Japanese armor:

It’s the helmet spikes that really give it that appearance. Mike and Bryan eventually opted for a more Chinese look, which you see from the mooky non-bender soldiers. They look rather similar to the soldiers of Qin (lower image from the movie Hero, sorry for the shit resolution).

A bit of the samurai helmet influence was retained for the firebenders though. Note also the stylized facemask for samurai helmets and firebenders which are supposed to inspire terror in their foes. You can also draw a parallel to Japan’s industrialization, expansionism, and naval force in World War II.

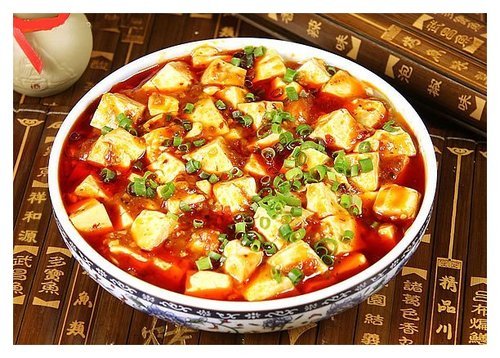

Still, I’m a little bit put off when people immediately jump to the conclusion that the Fire Nation is Japanese. Japanese and Chinese aesthetic senses are extremely different, if not starkly opposed. Japan seems to emphasize more minimalist approaches in a lot of things: their architecture tends to be more straight, simple, and rigid emphasizing clean lines and forms. Their cuisine focuses on a certain cleanliness and pureness of flavor. A lot of their ceramics are also earthy and elegant in form, though somewhat simple in patterning.

As an Imperial culture, China tends towards almost disgustingly baroque designs, intricate paintings, ornately carved buttresses and door screens, and complicated cuisines that can sometimes include dozens of carefully balanced spices (a feature of herbalism to promote health). It’s extremely gaudy and showy. Japanese art certainly does have many complex elements, but I suspect these were more influences they drew when they took cultural elements of Tang Dynasty China and did their own thing with it.