#'logic' is about not responding to emotional stimuli and not acting based on emotions - it does not mean you're smart

Text

Vulcan Dumb & Dumber

#T'Meni-bu#Movik#doodle page#bee doodles#suggestive#sveyko (guest appearance) <- she's talking about something she's writing#T'Meni calls Movik 'yam' ... if she were human she'd be a 'pookie bear <3' type of girl#I thought it'd be fun to see a Vulcan who's straight up an idiot#logical thinker - follower of Surakian principals etc etc but just also not smart <3#both T'Meni & Movik grew up sheltered and didn't try very hard in school. Movik's life plan was to get into Starfleet#and when he failed to do that his dad just made him the owner of one of his hot spring hotels. T'Meni's life plan was to marry Movik#and be beautiful and she succeeded! Now they both run that hot springs hotel and everyone who visits loves T'Meni#Nothing bad has ever happened to T'Meni and nothing bad ever WILL happen to T'Meni <3#beas ocs#star trek oc#vulcan oc#'logic' is about not responding to emotional stimuli and not acting based on emotions - it does not mean you're smart#and Movik & T'Meni are here to prove that to the world <3

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Using MBTI for your character (p1)

take the mbti test and answer like your character would, write down the answer you put.

what's the mbti type of your character?

what is their archetypal story role?

don't forget that your character doesn't have to be perfectly like the mbti type.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator

Based on Carl Jung's theory and determine 16 personality types, derived from four dichotomies:

extraversion vs introversion (focusing on the world outside vs focusing on mental world),

thinking vs feeling (acts based on reason vs acts based on heart),

sensation vs intuitive (led by external sensory stimuli vs led by undefinable internal feelings).

judging vs perceiving (structured and organized life vs freewheeling and spontaneous life).

The Sensing-Judging Types

Introverted Sensing Thinking Judgment (ISTJ)

energized by time spent alone, focuses on facts and details, makes decision based on logic and reason, prefers to be planned and organized.

detail-oriented, realistic, present-focused, observant, logical and practical, orderly and organized.

judgmental, subjective, tend to blame others, insensitive.

dominant: introverted sensing, focused on the present moment but rely on the memories of experiences to form expectations for the future.

auxiliary: extraverted thinking, looking for rational explanation for events, focus on details, appreciate knowledge that has immediate practical application.

tertiary: introverted feeling, make personal interpretation based on their internal set of values.

inferior: extraverted intuition, enjoys new ideas and experiences.

Introverted Sensing Feeling Judging (ISFJ)

enjoy structure, observers, focused on other people.

reliable, practical, sensitive, eye for detail.

dislikes abstract concepts, avoid confrontation, dislike change, neglects own needs.

dominant: introverted sensing, focus on details and facts, prefer concrete information, attuned to immediate environment and firmly grounded in reality, recall past experience to predict outcome of future choice/event.

auxiliary: extraverted feeling, focused on developing social harmony and connection which is accomplished by socially appropriate behaviors. try to fill the wants and needs of others.

tertiary: introverted thinking, tend to be very organized, prefers to see how things fit together and how it functions as a whole.

inferior: extraverted intuition, taking in facts and then exploring the what-if.

Extraverted Sensing Thinking Judging (ESTJ)

high value on tradition, rules and security. often become involved in civic duties, government branches and community organizations.

can be seen as predictable, stable, committed and practical. tend to be frank and honest about their opinions.

practical, realistic, dependable, self-confident, hard-working, traditional, strong leadership skills.

insensitive, inflexible, not good at expressing feeling, argumentative, bossy.

dominant: extraverted thinking, objective information and logic to make decisions. enjoy learning about things that they can see an immediate use for but tend to lose interest in abstract and theoretical things. good at making fast and decisive choice but may rush to judgment.

auxiliary: introverted sensing, good at remembering things with details, utilize past experiences to make connections with present events. more focused on familiarity. enjoy habits and routines.

tertiary: extraverted intuition, seek out novel ideals and possibilities. may explore the possible meanings in order to spot new connections or patterns.

inferior: introverted feeling, make decisions based on feeling, tend to give much thought to their emotions.

Extraverted Sensing Feeling Judging (ESFJ)

sensitive to the needs and feelings of others and are good at responding to the care the people need. want to be liked and can be easily hurt by unkindness/indifference.

derive their value system from external sources including the community at large. strong desire to exert control over their environment. careful observers of others and are adept at supporting and bringing the best in people.

kind, loyal, outgoing, organized, practical, enjoy helping others.

approval seeking, sensitive to criticism.

dominant: extraverted feeling, tend to make decisions based on personal feeling, tend to judge people and situation based on it.

auxiliary: introverted sensing, focused on the present and interested in concrete and immediate details.

tertiary: extraverted intuition, make connections and find creative solutions to problems, known to explore the possibilities when looking at a situation.

inferior: introverted thinking, organized and like to plan things in advance.

sources

https://www.truity.com/myers-briggs/judging-vs-perceiving

verywellmind.com

https://www.toolshero.com/psychology/jung-personality-types/

https://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/mbti-basics/the-16-mbti-types.htm

https://www.arcstudiopro.com/blog/myers-briggs-characters/

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

What kind of strengths and weaknesses do the Hymns os Struggle cast have? I think my Bioshock Au Henrietta's strength is kindness,but she is too honest as a flaw,Josephine Drew is intelligent and polite,but tends to come off as flinty and insensitive and Joshua is determined,but tends to over-empathise with other people.

Really lovely question! Here’s my best ideas at the moment. Heads up, there’s spoilers for the series throughout so I’ll tag it as “hymns spoilers,” but I think by this point most people that care about spoilers for the story have read it and I’m not super concerned about talking freely below.

Francine: She’s definitely not an illogical person, but she tends to go with her gut and heart. She also has to work to find the line between caring for someone and not taking care of herself. Her strengths are determination and compassion, and whether she likes it or not she’s a natural leader. While it’s a constant struggle on her mind, having to address boundaries with caring for others also means she’s very mature in finding things that bother her and figuring out what to do about it. She wants to understand other people, and while that often puts her at risk, the reward of companionship and others’ (if not begrudging) admiration of her genuine self is what keeps her alive in the unforgiving studio.

In a literal sense, she’s an educated sociology student as a strength. Her weaknesses in the studio are that she’s physically the weakest and she doesn’t know much about the studio and it’s story at all. As a human of flesh and blood- soul still attached- she’s in a fragile state here and constantly has to watch for dangers that would cause her to join the ink as everyone else has.

Gingie (Joey): A bit of a subversion of Francine. He cares a lot about others, but he also tends to make himself the responsible entity involved. He makes assumptions and decisions for others that aren’t his to make. He’s also very much in denial about aspects of himself that are negative, and finds them as things to ignore or eliminate rather than accept. He has as much strength for his weakness, though, in that he is extremely charismatic, especially thanks to his genuine front. He’s a dreamer, and a believer, and can and *will* make you believe you can do whatever it is ahead of you; same applies to himself.

In a literal sense, he’s immortalized by the studio and granted control over all of its supernatural abilities. He sees all of the studio through the eyes of any image of Bendy, such as on posters and dolls. Downside is that it’s based on his own (uncontrolled, ironically) emotions and thoughts, so things don’t always go as he plans. He has no choice but to see everything in the studio, and he has only limited say in what he causes.

Sammy: My interpretation of Sammy frames it so that his faith and sense of religion is a double edged sword, and he has to figure out how to navigate in a positive direction. He wants to be better, he wants to be helped, at worst he very easily becomes resigned to what seems to be fate (and given the studio I can’t blame him too much). However, this makes him excellent at finding things to hope in, the lights at the end of the tunnel. He *will* fight tooth and nail for what he believes in. He also doesn’t remember any of his past unless prompted, and often times doesn’t wish to know.

In a literal sense, as with other ink creatures in Hymns, if injured he can be reformed from the puddles. Not fun, at all, but doable. He’s stronger than searchers, but otherwise “on the bottom of the food chain.”

Alice: She is very easily provoked. This would make her predictable, if not for the fact that she has the bite to back it up. She embodies independence, for better or worse, and loathes reliance on others even emotionally. When she recognizes her own emotional attachments, she’s at least at first very uncomfortable. Her full memory of before the studio’s downfall is the most extensive, besides Joey’s, and can be used both as an advantage and disadvantage. As a strength, she recognizes beauty in humanity despite being away from it for so long. She’s plausibly the smartest person in the studio as well as the most practical and pessimistic.

In a literal sense, she knows both how to fight the “lesser” ink creatures and hide from the ink demon. Her ultimate goal is to obtain perfection and protect her progress on looking more and more like the original Alice cartoon, so while she likes to threaten and can follow through, she prefers not to put herself in a position with risk unless given no choice.

The Projectionist: If he has memories, in this form you can’t tell. He’s largely in his own dismal routine, pacing the halls and responding to stimuli as it engages with his senses. He has empathy and enjoys interaction, but it’s difficult to engage with unless you first put yourself at risk, as he is volatile at first contact. He is difficult to persuade, but has unbreakable loyalty if you have it.

In a literal sense, he’s deaf, but if standing in ink, he can feel the vibrations sound makes. His strength rivals the ink demon’s, and he can travel through the walls, although rarely.

The Ink Demon: Like the projectionist, but much less approachable and gives the studio residents an impression of godliness. He terrifies, and clearly he has power and control. In truth, he is the part of Joey that Joey cannot help- sort of like how one thinks they’d like to do something, but they wouldn’t; the ink demon does what Joey wants deep down, regardless of logic. The ink demon gives no impression of actual intelligent thought of his own, as he acts only as if puppeteered.

In a literal sense, interacting with Joey either directly or indirectly will influence the behavior of the ink demon. As in the case of Francine, her accidentally showing Joey her purpose for being in the studio and reminding him more and more of his son Henry caused the ink demon to not only spare her but often times help her, even when it went against what Joey was trying to accomplish.

#writing musings#batim#bendy#bendy headcanons#bendy and the ink machine#bendy au#bendy oc#joey drew#gingie#sammy lawrence#alice angel#malice angel#the projectionist#the ink demon#hymns of struggle#hymns spoilers#long post#Anonymous

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Diane E. Hoffmann & Anita J. Tarzian, The Girl Who Cried Pain: A Bias Against Women in the Treatment of Pain, 29 J Law, Med & Ethics 13 (2001)

To the woman, God said, “I will greatly multiply your pain in child bearing; in pain you shall bring forth children, yet your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you.” --Genesis 3:16

There is now a well-established body of literature documenting the pervasive inadequate treatment of pain in this country.1 There have also been allegations, and some data, supporting the notion that women are more likely than men to be undertreated or inappropriately diagnosed and treated for their pain.

One particularly troublesome study indicated that women are more likely to be given sedatives for their pain and men to be given pain medication.2 Speculation as to why this difference might exist has included the following: Women complain more than men; women are not accurate reporters of their pain; men are more stoic so that when they do complain of pain, “it’s real”; and women are better able to tolerate pain or have better coping skills than men.

In this article, we report on the biological studies that have looked at differences in how men and women report and experience pain to determine if there is sufficient evidence to show that gender3 differences in pain perception have biological origins. We then explore the influence of cognition and emotions on pain perception and how socialized gender differences may influence the way men and women perceive pain. Next, we review the literature on how men and women are diagnosed and treated for their pain to determine whether differences exist here as well. Finally, we discuss some of the underlying assumptions regarding why treatment differences might exist, looking to the sociologic and feminist literature for a framework to explain these assumptions.

We conclude, from the research reviewed, that men and women appear to experience and respond to pain differently, but that determining whether this difference is due to bio- logical versus psychosocial origins is difficult due to the complex, multicausal nature of the pain experience. Women are more likely to seek treatment for chronic pain, but are also more likely to be inadequately treated by health-care providers, who, at least initially, discount women’s verbal pain reports and attribute more import to biological pain contributors than emotional or psychological pain contributors. We suggest ways in which the health-care system and health-care providers might better respond to both women and men who experience persistent pain.

Do Men and Women Experience Pain Differently?

The question of whether men and women experience pain differently is a relatively recent one. Until about a decade ago, many clinical research studies excluded women, resulting in a lack of information about gender differences in disease prevalence, progression, and response to treatment.4 Research on sex-based and gender-based differences in pain response has mounted over the past several years, partially motivated by 1993 legislation mandating the inclusion of women in research sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.5

Three review articles summarized the research findings on sex-based differences in pain response through the mid- 1990s, with most research focusing on sensory (often laboratory-induced) pain. Unruh examined variations between men and women in clinical pain experience through an extensive review of available research.6 She found, in general, that women reported more severe levels of pain, more frequent pain, and pain of longer duration than men. Women were more likely than men to report migraines and chronic tension headaches, facial pain, musculoskeletal pain, and pain from osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia. Women were also more likely than men to develop a chronic pain syndrome after experiencing trauma similar to that experienced by men.

Berkley drew similar conclusions — that for experimentally delivered somatic (skin or deep tissue) stimuli, females have lower pain thresholds, greater ability to discriminate pain, higher pain ratings, and less tolerance of noxious stimuli than males.7 Berkley, however, cautioned that these differences were small and affected by many variables, such as type of pain stimulus, timing of the stimulus, size or bodily locus of the stimulus, and experimental setting. For example, more reliable differences between the sexes have been found when patients are exposed to electrical and pressure stimuli as opposed to thermal stimuli, and when pain is induced in experimental settings as opposed to clinical settings.

Lastly, Fillingim and Maixner reviewed research on sex-based differences in response to noxious stimuli.8 The studies they reviewed also indicated that although pain responses were highly variable among individuals, females exhibited greater sensitivity to laboratory-induced pain than males. They concluded that “it seems plausible that such disparity in the experience of clinical pain [between men and women] could be explained, at least in part, by enhanced pain sensitivity among females.”9

While approximately half of all existing studies prior to 1997 found no difference between men and women in their response to experimental pain, of those studies that did, all were in the same direction: “lower pain threshold, higher pain ratings, and lower pain tolerance for women.”10

More recent studies have contributed further empirical evidence of a difference between men and women in pain response.11 Much of this research has focused on a search for biological differences. Although these early findings do suggest biologically based differences, there remain many research questions yet to be answered.

Biological differences

A number of scientists have hypothesized about potential biological explanations for gender pain differences. Berkley described three aspects of male and female biology that plainly differ: the pelvic reproductive organs, types of circulating hormones, and cyclical changes in hormone levels.12

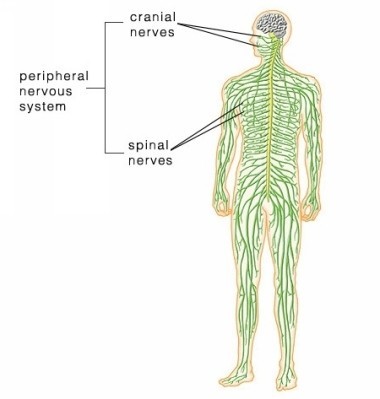

Other biological explanations for the differences in pain response include mechanisms of analgesia having to do with opioid receptors in the body, mechanisms of nerve growth factor, and sex-based differences in sympathetic nervous system function (e.g., sex-based differences in areas of the brain associated with reproduction). Berkley stated that these differences could result in men and women experiencing different emotional responses to pain13 (e.g., anxiety, fear, depression, or hostility).

Reproductive hormones

A number of studies have added to the body of literature on the influence of reproductive hormones on biological pain differences. Berkley concluded that the reproductive hormones appear to influence sex-based pain differences through the action of a number of neuroactive agents, such as dopamine and serotonin.14

Giamberardino and colleagues found that a woman’s pain sensitivity increases and decreases throughout her menstrual cycle, with skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscles being affected differently by female hormonal fluctuations.15 They also found that sex-based differences in pain response may depend on the proximity of the stimulus to external reproductive organs. Fillingim and colleagues found that the menstrual cycle produced greater effects on ischemic (i.e., lack of blood flow and oxygen), compared with thermal, pain sensitivity.16 The authors suggest that opiate receptors could be desensitized by reproductive hormones during certain phases of a woman’s menstrual cycle, thus increasing pain sensitivity (particularly ischemic pain sensitivity) at those times.

Glaros, Baharloo, and Glass found that lower levels of circulating estrogens may be associated with higher levels of temporomandibular disorder (TMD) pain and other joint pain in women.17 Dao, Knight, and Ton-That studied the influence of reproductive hormones on TMD.18 They hypothesized that there is a link between reproductive hormones and inflammation and pain — that the hormones may “act directly in the muscles to modulate the release of nitric oxide,” which causes vasodilation (blood vessel dilation), inflammation, and pain.19 In addition, estrogen may interact with various mediators of inflammation (i.e., swelling) and increase pain sensation.20

Stress-induced analgesia responses

Differences have been found between male and female rats for “stress-induced analgesia” responses.21 Stress-induced analgesia involves activation of an intrinsic pain inhibitory system by a noxious stressor, such as exercise-induced stress or predator-evoked stress.

Mogil and colleagues report on a sex-specific stress-induced analgesia mechanism in female mice that is known to be estrogen-dependent and to vary with reproductive status, but for which the neurochemical identity has remained obscure.22 The authors performed genetic mapping experiments to identify the gene underlying stress-induced analgesia in both sexes and found a specific genetic component in female mice but not in male mice.

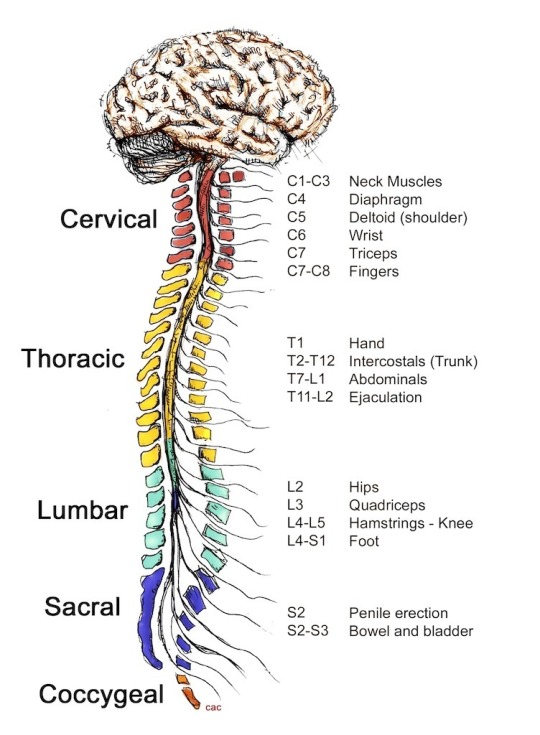

Brain and central nervous system

Some research has shown differences in the brain and central nervous system of men and women that may contribute to differences in pain response. For example, Fillingim and Maixner describe neural mechanisms that contribute to sex-based differences in the perceptual, emotional, and behavioral responses to noxious stimuli.23 These include peripheral afferents (impulses sent to the brain), brain and central nervous system networks, and peripheral efferents (commands sent from the brain to the muscles). The authors note differences in female tissue thickness and sensory receptor density as one example of structural differences in females that may contribute to enhanced perception of sensation to the skin.

Animal studies provide some evidence that sex-based differences in pain response have biological and genetic origins. Aloisi, Zimmermann, and Herdegen found differences in immune chemicals in the hippocampus and septum of male and female rats that were subjected to a persistent pain- ful stimulus and restraint stress.24 The authors hypothesized that hormonal and behavioral differences between the sexes are accompanied by genetic differences in the limbic system — an area of the brain that, in humans, is involved in cognition and emotion.

Other researchers have probed the human brain for sex- based differences that influence pain responses. Mayer and colleagues found that, compared to male patients with irritable bowel syndrome, female patients with the same syndrome showed specific perceptual alterations in response to rectosigmoid (intestinal) balloon distension and differences in regional brain activation measured by positron emission tomography (PET).25 Findings suggest that physiological sex-related differences in the experience of pain exist in irritable bowel syndrome patients and can be detected using specific stimulation models and brain imaging techniques.

Paulson and colleagues studied cerebral blood flow through PET imaging in normal right-handed male and female subjects as the subjects discriminated differences in the intensity of painless and painful heat stimuli applied to the left forearm.26 Females had significantly greater activation of the contralateral prefrontal cortex, the contralateral insula, and the thalamus when compared to the males. The authors surmised that the differences between men and women in their response to pain were (1) a direct result of physiological differences between men’s and women’s brains; (2) mediated by emotional or cognitive responses that are different between men and women and are responsible for brain activation differences between men and women; or (3) a result of both (1) and (2).

Biology as explaining too much, too little

Given the physiological sex differences reviewed thus far, one might expect the gap in pain responses between men and women to be greater than the research evidence indicates.27 This paradox in the research has led Unruh — commenting on Berkley’s conclusion that differences between men and women in pain perception and response exist but are small and highly variable28 — to argue for a “conceptual shift” in “our efforts to understand the relationships between sex and pain experience”:

The question changes from “Why do women and men differ in their experiences of pain?” to “How do women dampen the effect of powerful sex differences in physiological pain mechanisms to achieve only small sex difference in their actual pain experience?”29

Consequently, researchers must look not only at why women may experience more pain than men, but also at why the difference in experience is not greater than recent findings regarding physiological pain-related differences would indicate. One answer to this paradox may be that some physiological differences between men and women actually make their pain responses similar. For example, De Vries and Boyle concluded that despite major differences in physiological and hormonal conditions, differences between the sexes in the brain create a mediating effect on pain, perhaps resulting in men and women displaying remarkably similar behaviors.30 Another explanation is that more than physiological differences are at work.

What is clear is that the research to date provides ample evidence that differences between men and women in pain response exist.31 What is unclear is whether the reasons for these findings are grounded in differences in biology or differences in coping and expression, or both.

The mind-body connection

Although modern scientists have attempted to identify and localize specific pathophysiological mechanisms that produce and influence pain sensations, progress on this front is advancing slowly. Most experimental pain research has focused on laboratory-induced noxious sensory stimuli, such as heat, cold, pressure, and shock. Subjects report the level at which they detect pain (“threshold”) and the level at which they can no longer tolerate pain (“tolerance”). Bendelow writes: “The experimental nature of these studies does not allow the social context to be taken into account and the psychological research on pain perception is weighted heavily towards sensory cues, with little emphasis on the subjectivity, or indeed any recognition of models of perception that emphasise interaction between sensory cues and expectations or prior experience.”32

The focus on a physiological basis for pain has ignored the findings that one’s response to pain is influenced by a multitude of factors, which may include the biological, psychological, and cultural differences between men and women.

External stimuli may set off a biological cascade that contributes to the sensation of pain, but cognition and emotion also contribute to the experience of pain. Cognitive awareness of and emotional response to pain (which are affected by psychosocial and cultural influences) in turn influence the brain’s and body’s subsequent physiological responses. Unlike the “Cartesian” approach that views pain as a product of either biology (body) or psychology (mind), a more informed approach is to acknowledge the interdependence of the two, in addition to cultural influences.33

Psychological and cultural gender differences

Psychological factors influencing the pain response include cognitive appraisal of pain (i.e., meaning-making), behavioral coping mechanisms, and cultural influences. According to Unruh, “[u]nderlying biological differences in pain mechanisms may predispose women to have more pain and may affect recovery from pain but sociological [i.e., cultural] and psychological factors also influence pain perception and behavior.”34

Cognitive appraisal and meaning-making

Cognitive appraisal refers to the process of attributing meaning to an event, which then influences one’s behavioral response to that event.35 For various reasons, men and women may attribute different meanings to their pain experiences.

For one, the types of pain that men and women experience tend to be different. Women more often experience pain that is part of their normal biological processes (e.g., menstruation and childbirth), in addition to pain that may be a sign of injury or disease. Women may thus learn to attend to mild or moderate pain in order to sort normal biological pain out from potentially pathological pain, whereas men do not need to go through this sorting process.36

In addition, men’s and women’s different gender role expectations may influence how they attribute meaning to their pain. Women have been found, for example, to describe their pain by giving more contextual information, such as impact on personal relationships and child-care duties. Men, on the other hand, are more likely to wait to attend to pain until it threatens to interfere with their work duties. Their pain reports are more likely to be an objective report- ing of physical symptoms or functional limitations, and to lack reference to contextual factors such as impact on personal relationships.37

According to one study, factors that influenced women’s likelihood of seeking health care for their pain included a predisposition to “resilience or positive regard for their ability to handle the problem.” Men, in contrast, were influenced to seek health care by “a negative attitude about the condition in terms of its harmfulness, loss or threat.”38 Thus, gender differences in cognitive appraisal and meaning-making of pain may explain some of the differences between men and women in pain response.

Behavioral coping

Prompted by one’s cognitive appraisal of a stressor like pain, individuals respond using various coping mechanisms. Researchers have found that men and women differ in their mechanisms of coping with stress — particularly, coping with pain. Unruh, citing other studies, reported that women more frequently use coping strategies that include “active behavioral and cognitive coping, avoidance, emotion-focused coping, seeking social support, relaxation, and distraction, whereas men rely on direct action, problem-focused coping, talking problems down, denial, looking at the bright side of life and tension-reducing activities such as alcohol consumption, smoking and drug abuse.”39 Thoits found that women’s ways of coping involved more expression of feelings and seeking social support, whereas men’s ways of coping “were more rational and stoic (e.g., accepting the situation, engaging in exercise).”40 Unruh, Ritchie, and Merskey found that in response to pain, women reported significantly more problem-solving, social support, positive self-statements, and palliative behaviors than men.41 Jensen and colleagues found that among individuals with long-term intractable pain in the neck, shoulder, or back, women increased their behavioral activity (e.g., household chores and social activities) as a coping strategy more often than men.42 Other studies suggest that coping strategies are influenced more by the type and duration of pain than by whether the person is a man or a woman.43

Research has also shown that women, as compared to men, respond more aggressively to pain through health-related activities (e.g., taking medications or consulting a healthcare provider).44 This is consistent with studies that have shown that women tend to report more health-care utilization for treatment of pain than do men.45

Culture, gender, and pain

The interplay between behavior and the value systems of a culture is complex and may influence pain perception in many ways. Children are socialized from a very young age to think about pain and to react to painful events in certain ways. In many societies, boys are actively discouraged from expressing emotions.46 Pollack reports that in the United States, “[r]esearchers have found that at birth, and for several months afterward, male infants are actually more emotionally expressive than female babies. But by the time boys reach elementary school much of their emotional expressiveness has been lost or has gone underground. Boys at five or six become less likely than girls to express hurt or distress, either to their teachers or to their own parents.”47 Pollack attributes this change to attitudes toward boys that are “deeply ingrained in the codes of our society” and as a result of which “boys are made to feel ashamed of their feelings, guilty especially about feelings of weakness, vulnerability, fear, and despair.” Male pain research participants have reported that they “felt an obligation to display stoicism in response to pain.”48 Other investigators found that whether the researcher was a man or a woman influenced male pain response in a laboratory setting, with males reporting less pain in front of a female researcher than a male researcher, whereas the researcher’s sex did not affect the responses of female subjects.49

Culture and socialization may also account for the differences in pain reporting between men and women. Women have been found to adopt a more “relational, community-based perception of the world” that allows them to form more extended social support networks and to express their emotions more than men.50 Because of these different socialization experiences, women’s and men’s styles of communication differ,51 which most likely influence how they report their pain to each other and to health-care providers. Miaskowski noted that “women are better able to fully describe their pain sensations than men, or are more willing to describe them, especially to female nurses.”52 In addition, as already mentioned, women tend to describe their pain to a health-care provider by including contextual information, like the pain’s effect on their personal relationships.53

Differences in treatment

The literature suggests not only that men and women communicate differently to health-care providers about their pain, but that health-care providers may respond differently to them. Miaskowski reported on several studies that identified such differences in response and treatment.54 Faherty and Grier studied the administration of pain medication after abdominal surgery and found that, controlling for patient weight, physicians prescribed less pain medication for women aged 55 or older than for men in the same age group, and that nurses gave less pain medication to women aged 25 to 54.55

Calderone found that male patients undergoing a coronary artery bypass graft received narcotics more often than female patients, although the female patients received sedative agents more often, suggesting that female patients were more often perceived as anxious rather than in pain.56 An- other study, examining post-operative pain in children, found that significantly more codeine was given to boys than girls and that girls were more likely to be given acetaminophen.57

Miaskowski further reported on two more recent studies. In a 1994 study of 1,308 outpatients with metastatic cancer, Cleeland and colleagues found that of the 42 percent who were not adequately treated for their pain, women were significantly more likely than men to be undertreated (an odds ratio of 1:5).58 In another study of 366 AIDS patients, Breitbart and colleagues found that women were significantly more likely than men to receive inadequate analgesic therapy.59 The assessment of undertreatment in both studies was based on guidelines developed by the World Health Organization for prescribing analgesics.

Other studies also indicate differences in how men and women are treated by health-care providers for their pain. In a retrospective chart review of male and female post-operative appendectomy patients without complications, McDonald found that in the immediate post-operative period, males received significantly more narcotic analgesics than females.60 However, differences were not significant when taking into account the whole post-operative period. McDonald suggested that these differences might be due to gender-stereotyping during the initial post-operative period when the patient is still drowsy from anesthesia and not always able to make his or her pain needs known. The nurse may respond differently to male and female patients during this time, as compared to later in the post-surgical recovery period when patients are more fully awake and able to report their pain.61

A recent prospective study of patients with chest pain found that women were less likely than men to be admitted to the hospital. Of those hospitalized, women were just as likely to receive a stress test as men, but of those not hospitalized, women were less likely to have received a stress test at a one month follow-up appointment.62 The authors attributed the differences in treatment to the “Yentl Syndrome,” i.e., women are more likely to be treated less aggressively in their initial encounters with the health-care system until they “prove that they are as sick as male patients.” Once they are perceived to be as ill as similarly situated males, they are likely to be treated similarly.63

The “Yentl Syndrome” hypothesis fits well with the results of a study by Weir and colleagues, which found that of chronic pain patients who were referred to a specialty pain clinic, men were more likely to have been referred by a general practitioner, and women, by a specialist.64 The results suggest that women experience disbelief or other obstacles at their initial encounters with health-care providers. An older study (1982) also found that of 188 patients treated at a pain clinic, the women were older and had experienced pain for a longer duration prior to being referred to the clinic than the men. In addition, the researchers found that women were given “more minor tranquilizers, antidepressants, and non-opioid analgesics than men. Men received more opioids than did women.”65 These findings are consistent with those reported by Elderkin-Thompson and Waitzkin, who reviewed evidence from the American Medical Association’s Task Force on Gender Disparities in Clinical Decision-Making. Physicians were found to consistently view women’s (but not men’s) symptom reports as caused by emotional factors, even in the presence of positive clinical tests.66

In addition to actual differences in treatment, studies have also shown differences in health-care providers’ perceptions of men’s and women’s experiences of pain. McCaffery and Ferrell, using a questionnaire administered to more than 300 nurses, found that nurses perceived differences between men and women in sensitivity to pain, pain tolerance, pain distress, willingness to report pain, exaggeration of pain, and nonverbal pain expressions.67 More respondents felt that women, as compared to men, were less sensitive to pain, more tolerant of pain, less distressed as a result of pain, and more likely to report pain and express pain through nonverbal gestures. In another study, nurses were given vignettes describing a particular patient and situation, and were asked to estimate the minutes needed for specific nursing interventions for each patient. In their estimations, the nurses planned significantly more analgesic administration time (as well as ambulation and emotional sup- port time) for male patients than for female patients.68

In addition to whether the patient is a man or a woman, physical attractiveness and nonverbal expressions of pain have been found to influence a health-care provider’s response to the patient’s pain. Hadjistavropoulos and colleagues found that physically unattractive patients were more likely to be perceived as experiencing greater pain than more attractive patients and that the more attractive patients were more likely to be viewed as able to cope with their pain.69 These differences in perception were more likely to be true for female patients than male patients — that is, the effect of the patient’s attractiveness (or lack thereof) on a health-care provider’s perception of the patient’s pain sensitivity was not significant for male patients but it was for female patients. Attractive female patients were thought to be experiencing less pain than unattractive female patients. The authors concluded that a “strong ‘beautiful is healthy’ stereotype” was used by health-care providers in assessing patient pain and that attractive persons “were perceived to be experiencing less pain intensity and unpleasantness, less anxiety and less disability than physically unattractive persons.”70 The authors further concluded that such stereotypes have a negative effect for both attractive and unattractive individuals.71

What Accounts for Differences in Treatment?

The available literature indicates that women receive less treatment for their pain than men. These findings raise the question of whether such a difference in treatment is justified or whether the differences are the result of unproven assumptions and biases about men and women and their sensitivity toward pain or their credibility in reporting pain.

Rationales supported by the data

Treating men and women differently for their pain might be justified if they experience pain differently or respond differently to pain treatment modalities. As for the latter argument, previous research has shown that men and women metabolize medication differently.72 In response to pain medications specifically, Gear and colleagues showed that women experience significantly greater analgesia from kappa-opioids like pentazocine than males.73 Others have predicted that genetic research will lead to identifying drugs for pain that are specific to men’s and women’s biological needs.74

In addition, evidence indicates that men and women do experience pain differently. There is no consensus, however, whether this difference in experience is because women are biologically more sensitive to pain than men, although recent studies provide evidence to support this explanation.75 What is clear is that women in clinical studies often report greater sensitivity than men in response to the same noxious stimuli. This could mean that, in fact, there is a biological difference between men and women that results in women experiencing greater pain than men when exposed to the same stimulus. Or, it could mean that women do not tolerate pain as well as men, or that women are more likely to report pain than men are.

The difficulty in concluding much from existing studies is the subjective nature of pain. While some researchers are exploring the development of diagnostic techniques to validate patients’ pain reports, there are currently no reliable, objective, clinical indicators for pain, e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, temperature.76 Although men’s and women’s brain and central nervous system functioning have been found to respond differently to laboratory-induced pain, the degree to which cognition and emotion influence these pathways is unclear. Animal studies provide compelling evidence that basic biological differences do exist; however, pain in these studies is measured differently from how it is measured in humans (e.g., time to paw withdrawal or tail lick in rats versus self-report in humans). Because diagnostic techniques are not available to accurately “measure” pain and because pain perception is affected by psychological and cultural factors, patient self-reporting remains the basis for diagnosis.

The data support the assertion that women are more likely to report pain than are men in response to the same stimuli. Apart from differences in pain sensitivity, this could be attributed to differences in coping. The literature on coping appears to indicate that women tend to cope in more constructive ways, such as seeing a health-care provider, reaching out to others, and/or praying, whereas men tend to accept the pain, ignore it, or resort to drugs or alcohol rather than consult with a health-care provider.77 These strategies are consistent with cultural mores that discourage men from expressing weakness or vulnerability.

An alternative hypothesis that may explain why men’s pain complaints evoke more medical and nursing interventions is that men wait longer than women to seek medical assistance for their pain and thus are at a stage where their pain characteristics are more extreme and in need of more immediate care. But while there is some evidence that men are less likely to seek medical care for their pain at early stages (or until it interferes with their ability to work),78 there is no evidence that they are in need of more aggressive care than women when they enter the health-care system for pain relief.79 Rather, study findings suggest that women report more severe pain symptoms than men because they suffer from more severe pain-related diseases. For example, in a telephone survey of those with rheumatoid arthritis, researchers found that women reported more severe symptoms than men and that this difference was due to “more severe disease rather than a tendency by women to over-report symptoms or over-rate symptom severity.”80

The perception of women by health-care providers

Given that women experience pain more frequently, are more sensitive to pain, or are more likely to report pain, it seems appropriate that they be treated at least as thoroughly as men and that their reports of pain be taken seriously. The data do not indicate that this is the case. Women who seek help are less likely than men to be taken seriously when they report pain and are less likely to have their pain adequately treated.81

This conclusion raises the question of what accounts for this difference in treatment. In light of the apparent lack of objective data supporting lesser treatment of women for pain, a likely explanation is the health-care provider’s attitudes regarding male and female sensitivity to or tolerance of pain and the validity of their self-reports. There are, in fact, data to support the hypothesis of this attitude or bias by health-care providers. The study by McCaffery and Ferrell of 362 nurses and their views about patients’ experiences of pain found that while most of the nurses (63 percent) agreed that men and women have the same perception of pain, 27 percent thought that men felt greater pain than women. Only 10 percent thought that women experienced greater pain than men in response to comparable stimuli.82 This result has no justification in the literature (and, as discussed above, is actually contradicted by it). The authors do not speculate as to what might contribute to this difference in attitude.

The same study also found that almost half of the respondents (47 percent) thought that women were able to tolerate more pain than men as compared to 15 percent who felt that men were able to tolerate more pain than women. This result, although consistent with other studies,83 seems at odds with our societal notions that men are stronger and tougher than women and better able to withstand physical discomfort. McCaffery and Ferrell explained this seeming contradiction by speculating that while society attributes strength and bravery to men, these characteristics are dis- played by an unwillingness to complain or express discomfort rather than by an actual tolerance of discomfort.

Other researchers offer alternative explanations for this perceived difference in tolerance. Some have asserted that as a result of women’s biological role in childbirth, women are capable of withstanding significantly more pain than men.84

Fillingim and Maixner postulate that the sum of men’s and women’s differences in pain response exist as a consequence of evolutionary pressures that increase reproductive potential and species survival.85 In her study of the interplay of pain, gender, and culture, Bendelow found that women were frequently thought to be equipped with a “natural capacity to endure pain,” in part linked to their reproductive functioning.86 This attitude does appear to be somewhat common among certain groups, as conveyed by offhand remarks such as, “if men had to bear children, there wouldn’t be any.”87

Bendelow found that “the perceived superiority of capacities of endurance is double-edged for women — the assumption that they may be able to ‘cope’ better may lead to the expectation that they can put up with more pain, that their pain does not need to be taken so seriously.”88 Crook and Tunks point to the influence of the psychoprophylaxis movement in the United States with its implicit assumption that it is good to experience childbirth without the aid of analgesia. As a result, some women who have “gone through psychoprophylaxis classes, feel guilty if they relent at the last minute and ask for an epidural”; according to the authors, “these attitudes imply that we have a value system endorsed by some parts of our population that suggest women should be encouraged to keep a stiff upper lip.”89

Another possible explanation of why health-care providers view women as better able to tolerate pain and thus in need of less treatment is that women have better coping mechanisms than men for dealing with pain. The literature confirms that women in fact have a greater repertoire of coping skills to deal with their pain. These include a greater ability to verbally acknowledge and describe their pain, to seek health-care intervention, and to gain emotional support. Men, in contrast, are likely to ignore the pain or delay seeking treatment.90 Yet this reluctance on the part of men does not lead to the conclusion that women, as not reluctant, must therefore be less in need of adequate treatment. Rather, a request for medical care would seem to imply that the person perceives her pain as real and enough of a threat to her lifestyle to seek outside assistance.

What men’s reluctance says — if anything at all — is that they are perhaps, as a whole, more undertreated than we think. While their complaints of pain appear to be taken more seriously than women’s pain complaints when they initially enter the health-care system, many may not seek medical assistance for their pain and, as a result, may be disadvantaged in getting relief from their painful symptoms.

A third possible explanation of why health-care providers might view men as less tolerant of pain than women may be a projection that men need more assistance with their pain because they are the household breadwinners. In their study, McCaffery and Ferrell found that nurses tended to equate “day-to-day physical functioning with pain tolerance” and that nurses believed men were more likely to stop functioning when they were in pain whereas women would continue their role as homemaker in addition to working outside the home. Another study similarly found that men were “more likely to be referred earlier for active treatment with a combination of therapies because of the demands of their bread- winner roles.”91 Again, such reasoning is unfounded. Unruh argued that women may, in fact, more readily attend to pain and more aggressively manage it because they assume more role responsibilities than men.92 As a result, they “may have more complex concerns about managing the interference of pain in the activities and responsibilities of daily life.” Given this possibility, it would again make more sense for health-care providers to at least be as aggressive in treating women for pain as they are in treating men.

Another factor that may play a key role in explaining the different treatment of men and women for pain and the tendency to treat women less aggressively is the subjective nature of pain and the credibility given to women’s self-reports of pain. These two factors perhaps exacerbate the likely undertreatment of women for pain.

Western medicine discounts female pain expression

In Western medicine, health-care providers are trained to rely predominantly on objective evidence of disease and injury. This is not only true of physicians but also nurses. One study of nurses found that they incorrectly expect patients who report moderate to severe pain to have elevated vital signs or behavioral expressions of pain.93 The medical model overemphasizes objective, biological indicators of pain and underacknowledges women’s subjective, experiential reports. Johansson and colleagues state, “medical models often end up in reductionism and medico-centrism, since they look for expert explanations in biological facts.”94 They cite a study by Baszanger which revealed that physicians attempting to make a diagnosis after consulting with a patient considered “cellular pathology as ‘something,’ whereas illness-provoking, psycho-social circumstances were ‘nothing.’”95

The subjective nature of pain requires health-care providers to view the patient as a credible reporter, and stereo- types or assumptions about behavior in such circumstances (oversensitivity, complaining, stoicism) add to the likelihood of undertreatment of some groups and overtreatment of others.96 The feminist literature is rife with examples and criticism of women’s voices not being heard or considered credible in the male-dominated health-care system. Sherwin de- scribes physicians as frequently “patronizing, detached, disrespectful, ... and unwilling to trust the reports of their women patients.”97 Dresser, in characterizing the literature on women’s health care, finds that women’s “[s]ubjective experiences of illness and treatment are frequently ignored.”98

A deeper examination of why women are treated this way is explored by several feminist authors. They attribute it to a long history within our culture of regarding women’s reasoning capacity as limited99 and of viewing women’s opinions as “unreflective, emotional, or immature.”100 In particular, in relation to medical decision-making, women’s moral identity is “often not recognized.”101 In a recent article, Parks argued that women’s requests for physician assisted suicide (PAS) are likely to be ignored. Parks reasoned that while a man’s request for help in ending his life is likely to be considered a “rational self-evaluation” if marked by “intolerable pain, personal suffering or terminal illness, ... women’s similar experiences are much more likely to be rejected, discounted, or unheeded because their capacity for such determinations of personal suffering are questioned.”102

Evidence of health-care providers’ doubting the pain experience of women with chronic pain is provided by Grace. She found that women with pelvic pain expressed difficulty communicating with their general practitioner about their pain, and some difficulty communicating with their gynecologist.103 A significant number of the women “did not think the doctor (GP) really understood what they said and left the doctor’s office feeling that there were things about their pelvic pain that they hadn’t talked about.”104 These women had received seventy-three different diagnoses to explain the cause of their pain, and reported that their physician implied “nothing was wrong” if no physical cause of pain could be identified.105 More than half of the women said that on occasion they felt that the doctor was not taking their pain seriously or that the doctor expected them to put up with their pain.

Women are also portrayed as hysterical or emotional in much of the medical and other literature. While men may be seen as forceful or aggressive, women are perceived as hysterical for the same behavior.106 Physicians have found women to have more “psychosomatic illnesses, more emotional lability and more complaints due to emotional factors” than men.107 In a frequently cited paper by Engel, “the majority of the case histories presented to illustrate ‘psychogenic pain and the pain prone patient’ are histories of females.”108 Fishbain and colleagues found that female chronic pain patients were more likely to be diagnosed with histrionic disorder (excessive emotionality and attention-seeking behavior) compared to male chronic pain patients.

Some researchers have argued that a “bias toward psychogenic causation for disorders in women has occurred even in well defined painful biological processes: ‘Despite the well documented presence of organic etiologic factors, the therapeutic literature is characterized by an unscientific recourse to psychogenesis and a correspondingly inadequate, even derisive approach to their management.’”109 These findings are consistent with studies reporting that female pain patients are less likely than their male counterparts to be taken seriously or are more likely to receive sedatives than opioids for the treatment of their pain.

The health-care provider’s bias toward psychogenic causes of women’s pain is problematic on two levels. First, women are more likely than men to have their pain attributed to psychogenesis whether or not that is in fact a cause of their pain. Second, for those women whose pain is exacerbated by emotional disorders, the health-care provider’s bias against psychological contributors to pain may lead them to undertreat the pain. Some claim that health-care providers’ predisposition toward attributing women’s pain to emotional causes is related to the higher prevalence of emotional problems (e.g., depression and anxiety) among women.110 However, it is possible that a gender bias exists in the processes by which women are evaluated for and diagnosed with these psychological disorders. What is clear is that women are more likely than men to express their feelings and more likely than men to have their symptoms (including pain) attributed to emotional factors. What is unknown is the degree to which emotional factors actually contribute to women’s and men’s pain experiences.

The tendency of health-care providers to discredit women’s pain reports may, in part, be rooted in communication differences between men and women. Vallerand argues that “[b]ecause pain is a subjective phenomenon that can be assessed most reliably from the patient’s self-report, the ability to communicate the discomfort of pain to a HCP [health- care provider] should be an advantage.” In contrast, it appears that “women’s ability to verbalize their emotions causes their responses to be viewed with suspicion [e.g., considered psychologically based] and treated less aggressively.”111 Alternatively, women’s style of communication may simply not fit neatly into the traditional medical interview model adopted by most physicians. In this model, Smith writes:

[the] physician controls the entry and exit of topics and controls the time devoted to a certain topic. By interrogative speech acts, ... the physician also controls the introduction and timing of topics. Through interruptions, the physician allows or cuts off patient lines of questioning. Several studies have shown that the physician-led medical interview is confined mainly to the question-and-answer mode of speech and that patient-initiated questions are often “dispreferred” in medical interviews.112

In general, women in Western societies are socialized to take turns in conversation, to downplay their own status, and to demonstrate behaviors that communicate more accessibility and friendliness.113 While both men and women might benefit from a more humanistic approach to physician-patient communication,114 it is likely that women are more likely to be disadvantaged by the traditional medical interview model. Women with chronic pain may be particularly vulnerable in this traditional communication style and re- buffed by physicians in their attempts to express the multiple ways in which their pain affects the quality of their lives and their ability to function.115

Lastly, patient characteristics and behaviors may also play a role in how female pain patients are perceived and, thus, how they are treated by their physicians. To the extent that women are culturally influenced to try to look good, even on visits to their physician, they may be viewed by their physician as attractive and thus not really in pain.116 Alternatively, if female patients present with hostility, they may not receive appropriate treatment. Patient hostility has been reported as an obstacle to establishing a rapport with a healthcare provider. A few studies have indicated a correlation between female pain patients and high levels of hostility.117 Such hostility, however, may be the result of frustration with the medical system and difficulty finding a sympathetic health-care provider. There is evidence that chronic pain patients must see dozens of physicians before finding one that is willing and/or able to treat their pain.118

Summary, Implications, and Recommendations

The research findings point to several troubling inconsistencies or paradoxes regarding the differences between men and women in pain response and treatment:

While women have a higher prevalence of chronic pain syndromes and diseases associated with chronic pain than men, and women are biologically more sensitive to pain than men and respond differently to certain analgesics, women’s pain reports are taken less seriously than men’s, and women receive less aggressive treatment than men for their pain.

Although women have more coping mechanisms to deal with pain, this may contribute to a general perception that they can put up with more pain and that their pain does not need to be taken as seriously.

Although women more frequently report pain to a health-care provider, they are more likely to have their pain reports discounted as “emotional” or “psychogenic” and, therefore, “not real.”

Women, being socialized to attend more to their physical appearance, are more likely than men to have health-care providers assume they are not in pain if they look more physically attractive.

Men with chronic pain are more likely to delay seeking treatment, but generally receive a more aggressive response by health-care providers once they enter the health-care system.

Both men and women are more likely to have the emotional or psychological component of their pain experience suppressed due to Western medicine’s tendency to separate mind and body and to view objective, biological “facts” as more credible than subjective feelings.

If one examines these findings from different ethical perspectives, they are deeply problematic. From a justice perspective, for example, there exists a strong argument that individuals should be treated equally effectively according to their needs. Thus, a just approach to providing sex-specific, gender-sensitive pain management treatments acknowledges that men and women in pain may have different needs. The current situation, in which women are more likely than men to be undertreated for their pain, is ethically unjustifiable.

From a utilitarian perspective, undertreating women who have persistent pain is likely to have negative outcomes not only for productivity in the workforce but also for families and children. While undertreating men for pain has implications for their role as monetary providers, the implications of undertreating women are perhaps more far-reaching. In many families, the woman is now the breadwinner or one of the breadwinners.119 In addition, the woman typically takes on the primary role of family caretaker, making sure the household runs well, there is food on the table, and the children are cared for. If women are unable to function because of their pain, the possibility of extensive harm to families and children is very real.

The consequences for our health-care system are also potentially negative. A health-care system that continues to discriminate in its treatment of women is also likely to lose the confidence of its female patrons. There is, in fact, evidence that more women than men use alternative therapies for health-care treatment.120 While the loss of confidence in the conventional health-care system is a threat to its continued well-being, the elevated interest in complementary121 and holistic therapies may be a positive side effect of female patients’ dissatisfaction with the traditional medical system. The question of whether such therapies will be alternative or complementary to conventional medical therapies will be influenced by how conventional health-care providers respond to the demand for a more holistic approach to pain management.

From a perspective of narrative or care ethics, the fact that pain defies mind-body dichotomization and that women, in general, tend to adopt a more holistic approach to health and illness122 might provide justification for a female-specific approach to pain treatment — one that explores etiologies of pain without bias for or against biology, psychology, or other affective contributors, and one that acknowledges context and lived experiences.

Although the growth of holistic medicine may be one silver lining of conventional medicine’s gender-biased approach to pain treatment, this does not change the ethical imperative to rectify our mainstream health-care system’s unjust treatment of women with pain. It is necessary to begin educating health-care providers and those who train them to expose biases that lead to the undertreatment of women. Some research has shown that efforts at educating and enlightening health-care providers regarding women’s health needs has positive effects.123 Moreover, the bias against psychological or emotional pain contributors adversely affects both women and men. Women’s pain tends to be viewed as more emotionally based and thus less credible — or, likewise, less credible if indeed it is emotionally based.124 Men’s pain is more likely to be acknowledged strictly as a physical symptom, thus reinforcing the societal expectation that men suppress their emotions, even if it impedes their pain treatment and recovery.125 Medical schools must endorse, and teach students, an approach that best elicits the concerns of any patient in pain — an approach that does not discount the patient’s subjective reports of pain. This will require attentiveness to the emotional aspects of a patient’s reports of pain. As Johansson and colleagues state:

A purely diagnosis-oriented approach is not enough, and an attitude of healing through adaptation must be completed with a gender perspective on women’s actual circumstances. The medical encounter ought to provide possibilities for the patient to express psychosocial problems. Physicians must have a chance to listen, voice concern, discuss solutions and offer remedies such as counseling as well as medication to empower the patient.126

In addition to more attention to this issue in the medical school curriculum by modeling effective physician-patient communication with respect to pain management, there needs to be scrutiny on the part of quality care evaluators such as the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), as well as ethical awareness-raising by institutional ethics committees about the current bias in the pain treatment of women. Without this pressure, change is unlikely. The fact that JCAHO has established new pain management standards for the institutions that they accredit is a step in the right direction.127 Perhaps inclusion of evaluative mechanisms to ensure that vulnerable populations are not undertreated for pain due to a health-care provider’s gender, ethnic, age, or racial biases will contribute to a more just approach to pain management. In addition to JCAHO’s regulatory approach, institutional ethics committees have a role in educating and enlightening health-care providers regarding unjust pain treatment. Indeed, future JCAHO standards that address organizational ethics may dovetail into the same arena.

Conclusion

Research indicates that differences between men and women exist in the experience of pain, with women experiencing and reporting both more frequent and greater pain. Yet rather than receiving greater or at least as effective treatment for their pain as men, women are more likely to be less well treated than men for their painful symptoms. There are numerous factors that contribute to this undertreatment, but the literature supports the conclusion that there are gender-based biases regarding women’s pain experiences. These biases have led health-care providers to discount women’s self-reports of pain at least until there is objective evidence for the pain’s cause. Medicine’s focus on objective factors and its cultural stereotypes of women combine insidiously, leaving women at greater risk for inadequate pain relief and continued suffering. Greater awareness among health-care providers of this injustice, a readjustment of medicine’s preoccupation with objective factors through education about alternative approaches, and scrutiny by quality and ethical reviewers within health-care institutions are necessary to change health-care providers’ behavior and ensure that women’s voices regarding treatment of their pain are heard.

References

1. See R. Payne, “Practice Guidelines for Cancer Pain Treatment: Issues Pertinent to the Revision of National Guidelines,” Oncology, 12, no. 11A (1998): 169–75; M. McCaffery, “Pain Control: Barriers to the Use of Available Information,” Cancer, 70, no. 5 (supplement) (1992): 1438–49; R. Bernabei et al., “Managing Pain in Elderly Patients with Cancer,” JAMA, 279, no. 23 (1998): 1877–82. See also P. Wall and M. Jones, Defeating Pain, The War Against a Silent Epidemic (New York: Plenum, 1991).

2. See K.L. Calderone, “The Influence of Gender on the Frequency of Pain and Sedative Medication Administered to Postoperative Patients,” Sex Roles, 23 (1990):11–12, 713–25.

3. See P.L. Walker and D.C. Cook, “Brief Communication: Gender and Sex: Vive la Difference,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 106, no. 2 (1998): 255–59, who underscore maintaining the distinction between “sex” (the anatomical or chromosomal categories of male and female) and “gender” (socially constructed roles that are related to sex distinctions). It should be noted that while isolating the influence of sex and gender on pain response and treatment is the focus of this article, we do not mean to dismiss the powerful influence of class, race, culture, education, and other such variables that likely affect pain response and treatment.

4. See S.J. Blumenthal and S.F. Wood, “Women’s Health Care: Federal Initiatives, Policies, and Directions,” in S. Gallant and G.P. Keita, eds., Health Care for Women: Psychological, Social & Behavioral Influences (Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 1997): 57–71.

5. See National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993, Pub. L. No. 103-43, 107 Stat. 22 (June 10, 1993).

6. A.M. Unruh, “Gender Variations in Clinical Pain Experience,” Pain, 65 (1996): 123–67.

7. See K.J. Berkley, “Sex Differences in Pain,” Behavioral & Brain Sciences, 20, no. 3 (1997): 371–80.

8. See R.B. Fillingim and W. Maixner, “Gender Differences in the Responses to Noxious Stimuli,” Pain Forum, 4, no. 4 (1995), 209–21.

9. Id. at 209.

10. A.M. Unruh, “Why Can’t a Woman Be More Like a Man?,” Behavioral & Brain Sciences, 20, no. 3 (1997): at 467.

11. See T.D. Carr, K.L. Lemanek, and F.D. Armstrong, “Pain and Fear Ratings: Clinical Implications of Age and Gender Differences,” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 15, no. 5 (1998): 305–13; B.S. Krogstad, A. Jokstad, and O. Vassend, “The Reporting of Pain, Somatic Complaints, and Anxiety in a Group of Patients with TMD Before and 2 Years After Treatment. Sex Differences,” Journal of Orofacial Pain, 10, no. 3 (1996): 263– 69; O. Plesh et al., “Gender Difference in Jaw Pain by Clench- ing,” Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 25, no. 4 (1998): 258–63 (corroborating that women have a higher incidence than men of temporomandibular pain). See also C.R. France and S. Suchowiecki, “A Comparison of Diffuse Noxious Inhibitory Controls in Men and Women,” Pain, 81, no. 1–2 (1999): 77–84 (finding that women exhibited significantly lower pain thresh- olds than men and reported significantly greater pain in response to both ischemia and electrocutaneous noxious stimulation).

12. See Berkley, supra note 7.

13. Id.

14. Id.

15. See M.A. Giamberardino et al., “Pain Threshold Variations in Somatic Wall Tissues as a Function of Menstrual Cycle, Segmental Site and Tissue Depth in Non-Dysmenorrheic Women, Dysmenorrheic Women and Men,” Pain, 71 (1997): 187–97.

16. SeeR.B.Fillingimetal.,“IschemicButNotThermalPain Sensitivity Varies Across the Menstrual Cycle,” Psychosomatic Medicine, 59 (1997): 512–20.

17. See A.G. Glaros, L. Baharloo, and E.G. Glass, “Effect of Parafunctional Clenching and Estrogen on Temporomandibular Disorder Pain,” Journal of Craniomandibular Practice, 16, no. 2 (1998): 78–83.

18. See T.T. Dao, K. Knight, and V. Ton-That, “Modulation of Myofascial Pain by the Reproductive Hormones: A Preliminary Report,” The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 79 (1998): 663– 70.

19. Id. at 667.

20. Id.

21. See B.S. McEwen, S.E. Alves, K. Bulloch, and N.G. Weiland, “Clinically Relevant Basic Science Studies of Gender Differences and Sex Hormone Effects,” Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 34, no. 3 (1998), 251–59, in which the authors present a review of studies depicting the array of neurochemical and structural effects of ovarian hormones, including their influence on cognitive function and pain sensitivity. Female rats showed less opioid-mediated stress-induced analgesia than male rats when exposed to a variety of stressors, and male rats demonstrated greater swim stress analgesia and less predator-evoked analgesia than females.

22. See J. S. Mogil et al., “Identification of a Sex-Specific Quantitative Trait Locus Mediating Nonopioid Stress-Induced Analgesia in Female Mice,” The Journal of Neuroscience, 17, no. 20 (1997): 7995–8002.

23. Fillingim and Maixner, supra note 8, at 214.

24. See A.M. Aloisi, M. Zimmermann, and T. Herdegen, “Sex-Dependent Effects of Formalin and Restraint on c-Fos Expression in the Septum and Hippocampus of the Rat,” Neuroscience, 81, no. 4 (1997): 951–958. See also A.M. Aloisi, “Sex Differences in Pain-Induced Effects on the Septo-Hippocampal System,” Brain Research Reviews, 25, no. 3 (1997): 397–406.

25. See E.A. Mayer et al., “Review Article: Gender-Related Differences in Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders,” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 13, no. 2 (supplement) (1999): 65–69.

26. See P.E. Paulson et al., “Gender Differences in Pain Perception and Patterns of Cerebral Activation During Noxious Heat Stimulation in Humans,” Pain, 76 (1998), 223–29.

27. Berkley, supra note 7.

28. Berkley, supra note 7.

29. Unruh, supra note 6.

30. See G.J. De Vries and P.A. Boyle, “Double Duty for Sex Differences in the Brain,” Behavioral & Brain Sciences, 92, no. 2 (1998): 205–13.

31. One difficulty in interpreting evidence from research studies is the individual variability of the pain response. Greater variability makes research on pain responses more difficult, as it decreases power and thus increases the likelihood of having in- significant results due to an insufficient number of subjects studied. This has been recently corroborated in a meta-analysis by Riley and colleagues, who determined that only seven of thirty-four studies reviewed on gender differences in pain response had adequate sample sizes. This implies that gender differences have been underestimated rather than overestimated in pain research. See J.L. Riley III et al., “Sex Differences in the Perception of Noxious Experimental Stimuli: A Meta-Analysis,” Pain, 74 (1998): 181–87.

32. G. Bendelow, Pain and Gender (New York: Prentice Hall, 2000): at 17, citing V. Neisser, Cognition and Reality (San Francisco: Freeman, 1976): at 214.

33. Duncan describes how Cartesian (i.e., Descartes’) mind-body dualism is inaccurately equated with medical reductionism, the latter of which tends to dismiss mind (psychology) and favor body (physiology) in the diagnostic encounter. See G. Duncan, “Mind-Body Dualism and the Biopsychosocial Model of Pain: What Did Descartes Really Say?,” Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 25, no. 4 (2000): 485–513. A more holistic approach is supported somewhat by Melzack and Wall’s gate-control theory of pain, in which a neural mechanism in the spinal cord is thought to function like a gate to control the flow of nerve impulses into the central nervous system. Whether sensory transmission is in- creased or decreased (causing, respectively, a greater or lesser pain intensity perception) is influenced by cognitive and emotional input such as anxiety, mood state, attention, and past experiences. Bendelow and Williams state that the gate-control theory “signals the end of the mind/body split with regard to pain.” However, these authors acknowledge that currently “the biological remains dominant over the social.” Indeed, Duncan points out that the contemporary biopsychosocial model of pain does not entirely escape mind-body dualism. See also R. Melzack and P. Wall, The Challenge of Pain (Harmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1988); G.A. Bendelow and S.J. Williams, “Transcending the Dualisms: Towards a Sociology of Pain,” Sociology of Health and Illness, 17, no. 2 (1995): 139–65, at 143.

34. Unruh, supra note 6, at 157.

35. See R.S. Lazarus and S. Folkman, Stress, Appraisal, and Coping (New York: Springer, 1984), as cited in A. O’Leary and V.S. Helgeson, “Psychosocial Factors and Women’s Health: Integrating Mind, Heart, and Body,” in S.J. Gallant, G.P. Keita, and R. Royak-Shaler, eds., Health Care for Women: Psychological, Social and Behavioral Influences (Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 1997): 25–71.

36. Unruh, supra note 6.

37. Id. at 158.

38. R. Weir et al., “Gender Differences in Psychosocial Adjustment to Chronic Pain and Expenditures for Health Care Services Used,” The Clinical Journal of Pain, 12 (1996): 277–90, at 287.