#- Sustainable Agriculture

Text

"The transformation of ancestral lands into intensive monoculture plantations has led to the destruction of Guatemala’s native forests and traditional practices, as well as loss of livelihoods and damage to local health and the environment.

A network of more than 40 Indigenous and local communities and farmer associations are developing agroecology schools across the country to promote the recovery of ancestral practices, educate communities on agroecology and teach them how to build their own local economies.

Based on the traditional “campesino a campesino” (from farmer to farmer) method, the organization says it has improved the livelihoods of 33,000 families who use only organic farming techniques and collectively protect 74,000 hectares (182,858 acres) of forest across Guatemala.

Every Friday at 7:30 a.m., María Isabel Aguilar sells her organic produce in an artisanal market in Totonicapán, a city located in the western highlands of Guatemala. Presented on a handwoven multicolor blanket, her broccoli, cabbage, potatoes and fruits are neatly organized into handmade baskets.

Aguilar is in a cohort of campesinos, or small-scale farmers, who took part in farmer-led agroecology schools in her community. As a way out of the cycle of hunger and poverty, she learned ecological principles of sowing, soil conservation, seed storage, propagation and other agroecological practices that have provided her with greater autonomy, self-sufficiency and improved health.

“We learned how to develop insecticides to fend off pests,” she said. The process, she explained, involves a purely organic cocktail of garlic, chile, horsetail and other weeds and leaves, depending on what type of insecticide is needed. “You want to put this all together and let it settle for several days before applying it, and then the pests won’t come.”

“We also learned how to prepare fertilizer that helps improve the health of our plants,” she added. “Using leaves from trees or medicinal plants we have in our gardens, we apply this to our crops and trees so they give us good fruit.”

The expansion of large-scale agriculture has transformed Guatemala’s ancestral lands into intensive monoculture plantations, leading to the destruction of forests and traditional practices. The use of harmful chemical fertilizers, including glyphosate, which is prohibited in many countries, has destroyed some livelihoods and resulted in serious health and environmental damage.

To combat these trends, organizations across the country have been building a practice called campesino a campesino (from farmer to farmer) to revive the ancient traditions of peasant families in Guatemala. Through the implementation of agroecology schools in communities, they have helped Indigenous and local communities tackle modern-day rural development issues by exchanging wisdom, experiences and resources with other farmers participating in the program.

Keeping ancestral traditions alive

The agroecology schools are organized by a network of more than 40 Indigenous and local communities and farmer associations operating under the Utz Che’ Community Forestry Association. Since 2006, they have spread across several departments, including Totonicapán, Quiché, Quetzaltenango, Sololá and Huehuetenango, representing about 200,000 people — 90% of them Indigenous.

“An important part of this process is the economic autonomy and productive capacity installed in the communities,” said Ilse De León Gramajo, project coordinator at Utz Che’. “How we generate this capacity and knowledge is through the schools and the exchange of experiences that are facilitated by the network.”

Utz Che’, which means “good tree” in the K’iche’ Mayan language, identifies communities in need of support and sends a representative to set up the schools. Around 30-35 people participate in each school, including women and men of all ages. The aim is to facilitate co-learning rather than invite an “expert” to lead the classes.

The purpose of these schools is to help farmers identify problems and opportunities, propose possible solutions and receive technical support that can later be shared with other farmers.

The participants decide what they want to learn. Together, they exchange knowledge and experiment with different solutions to thorny problems. If no one in the class knows how to deal with a certain issue, Utz Che’ will invite someone from another community to come in and teach...

Part of what Utz Che’ does is document ancestral practices to disseminate among schools. Over time, the group has compiled a list of basics that it considers to be fundamental to all the farming communities, most of which respond to the needs and requests that have surfaced in the schools.

Agroecology schools transform lives

Claudia Irene Calderón, based at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is an expert in agroecology and sustainable food systems in Guatemala. She said she believes the co-creation of knowledge is “key to balance the decision-making power that corporations have, which focus on profit maximization and not on climate change mitigation and adaptation.”

“The recovery and, I would add, revalorization of ancestral practices is essential to diversify fields and diets and to enhance planetary health,” she said. “Recognizing the value of ancestral practices that are rooted in communality and that foster solidarity and mutual aid is instrumental to strengthen the social fabric of Indigenous and small-scale farmers in Guatemala.”

Through the implementation of agroecology schools across the country, Utz Che’ says it has improved the livelihoods of 33,000 families. In total, these farmers also report that they collectively protect 74,000 hectares (182,858 acres) of forest across Guatemala by fighting fires, monitoring illegal logging and practicing reforestation.

In 2022, Utz Che’ surveyed 32 women who had taken part in the agroecology school. All the women had become fully responsible for the production, distribution and commercialization of their products, which was taught to them in agroecology schools. Today, they sell their produce at the artisanal market in Totonicapán.

The findings, which highlight the many ways the schools helped them improve their knowledge, also demonstrate the power and potential of these schools to increase opportunities and strengthen the independence of women producers across the country...

The schools are centered around the idea that people are responsible for protecting their natural resources and, through the revitalization of ancestral practices, can help safeguard the environment and strengthen livelihoods."

-via Mongabay News, July 7, 2023

#a little older but still very good!#indigenous#farming#agriculture#sustainable agriculture#agroecology#land back#guatemala#latin america#north america#central america#indigenous knowledge#indigenous peoples#good news#hope

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every once in a while I’ll see some posts about everyone should become vegan in order to help the environment. And that… sounds kinda rude. I’m sure they don’t mean to come off that way but like, humans are omnivores. Yes there are people who won’t have any animal products be it meat or otherwise either due to personal beliefs or because their body physically cannot handle it, and that’s okay! You don’t have to change your diet to include those products if you don’t want to or you physically can’t.

But there’s indigenous communities that hunt and farm animals sustainably and have been doing so for generations. And these animals are a primary source of food for them. Look to the bison of North America. The settlers nearly caused an extinction as a part of a genocide. Because once the Bison were gone it caused an even sharper decline of the indigenous population. Now thankfully Bison did not go extinct and are actively being shared with other groups across America.

Now if we look outside of indigenous communities we have people who are doing sustainable farming as well as hunting. We have hunting seasons for a reason, mostly because we killed a lot of the predators. As any hunter and they will tell you how bad the deer population can get. (Also America has this whole thing about bird feathers and bird hunting, like it was bad until they laid down some laws. People went absolutely nuts on having feathers be a part of fashion like holy cow.)

We’re slowly getting better with having gardens and vertical farms within cities, and there’s some laws on being able to have a chicken or two at your house or what-have-you in the city for some eggs. (Or maybe some quails since they’re smaller than chickens it’s something that you’d might have to check in your area.) Maybe you would be able to raise some honey bees or rent them out because each honey tastes different from different plants. But ultimately when it comes to meat or cheese? Go to your local farmers. Go to farmers markets, meet with the people there, become friends, go actively check out their farm. See how the animal lives are and if the farmer is willing, talk to them about sustainable agriculture. See what they can change if they’re willing. Support indigenous communities and buy their food and products, especially if you’re close enough that the food won’t spoil on its way to you. (Like imagine living in Texas and you want whale meat from Alaska and you buy it from an indigenous community. I would imagine that would be pretty hard to get.)

Either way everything dies in the end. Do we shame scavengers for eating corpses they found before it could rot and spread disease? Do we shame the animals that hunt other animals to survive? Yes factory farming should no longer exist. So let’s give the animals the best life we can give them. If there’s babies born that the farmer doesn’t want, give them away to someone who wants them as a pet. Or someone who wants to raise them for something else. Not everyone can raise animals for their meat. I know I can’t I would get to emotionally attached. I’d only be able to raise them for their eggs and milk.

Yeah this was pretty much thrown together, and I just wanted to say my thoughts and throw them into the void. If you have some examples of sustainable farming/agriculture, please share them because while I got some stuff I posted from YouTube, I’m still interested to see what stuff I might’ve missed!

#solarpunk#farming#hunting#agriculture#sustainability#sustainable farming#sustainable agriculture#like Rewilding farm land is pretty interesting and trying to replicate an ecosystem with farm animals but also allowing wild animals#to make homes in the rewild farm land is pretty cool#and I have an absolute love for food/garden forests#and hydroponics have shown to be really great for communities in the winter time and they want to have fresh produce#all sorts of cool stuff

921 notes

·

View notes

Text

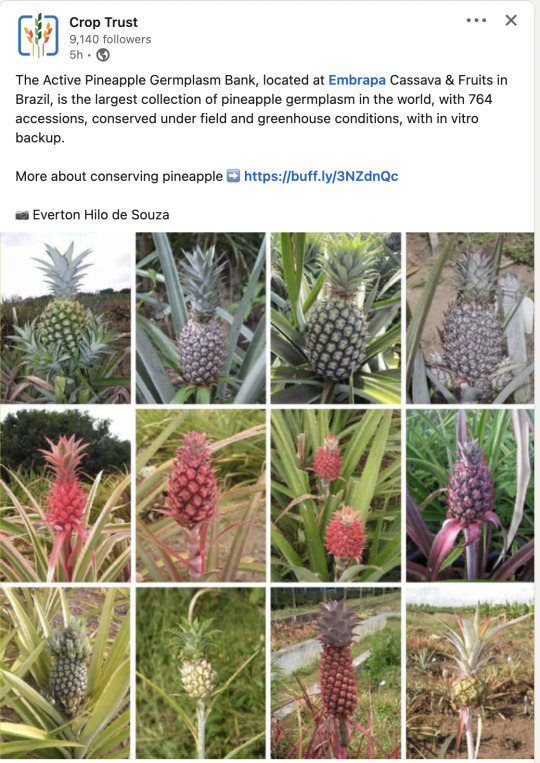

The surprising diversity of Pineapples (Ananas comosus).

The Active Pineapple Germplasm Bank (Pineapple AGB) of Embrapa Cassava & Fruits (Embrapa/ CNPMF) has more than 700 accessions under field conditions. As backups, there are copies kept in a greenhouse, with one or two plants per accession, cultivated in plastic pots with commercial substrate. An in vitro gene bank was established in 2003, and during the past few years, several studies have been carried out to improve the in vitro conservation protocol. Currently, about 60% of the AGB’s accessions are preserved by this protocol. Another conservation strategy used is cryopreservation of shoot tips and pollen grains, with well-defined methods. One of the most significant advances in the pineapple germplasm conservation has been the implementation of a quality control system, which enabled to define standard operation procedures (SOP) towards a more efficient and safer germplasm conservation.

Source:

Vidigal Souza, Fernanda & Souza, Everton & Aud, Fabiana & Costa, Eva & Silva, Paulo & Andrade, Eduardo & Rebouças, Danilo & Andrade, Danilo & Sousa, Andressa & Pugas, Carlos & Rebouças, Érica & França, Beatriz & França, Rivã. (2022). Advances in the conservation of pineapple genetic resources at Embrapa Cassava and Fruits. 28. 28-33.

#katia plant scientist#botany#plant biology#plant science#plants#fruit#pineapple#pineapples#biodiversity#agriculture#conservation#genetic diversity#sustainable agriculture#tropical plants#science#biology

325 notes

·

View notes

Text

9/19/23 ~ Hydroponics at school. Those cucumbers grew super fast 😳 and some Romaine Lettuce!

#indoor garden#container gardening#sustainable gardening#vegetable gardening#starting seeds#grow organic#grow your own food#organic gardening#tomato garden#green witch#greenhouse#greenhouse nursery#plant nursery#hydroponics#growing cucumbers#romaine lettuce#sustainable agriculture

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you like goats? Sure, we all do. But how about a trans-owned goat farm? Now that's something special.

For Pride this month, please consider making a small donation to Moxie Ridge Farm. This trans-owned sustainable goat farm not only makes incredible soap, but also supports agricultural education to teach the next generation of queer farmers!

The GoFundMe is located here: https://gofund.me/b1df9b1b

Every little bit helps! Happy Pride!

#moxie ridge farm#queer community#lgbtqia#pride month#trans pride#support your queer farmers#and also your cute goats#sustainable agriculture#upstate NY#upstate NY farming

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

So happy to have found this blog!

But any chance do you listen to the podcast "How to Save a Planet" by Gimlet? It's focused on climate change solutions, and seems like something you and your followers might be into.

One of my favorite episodes of theirs is Sheep + Solar, a Love Story: which talks dual purpose solar farms, which can be used to graze animals/grow crops at the same time they provide solar power. :)

I do not currently listen to that podcast, but I just downloaded a few episodes to try out--thanks for the recommendation! Here's a link to the podcast for anyone else who is interested.

The sheep + solar combination is such an ingenious win-win situation. For those not familiar: if you have a solar farm, you don't want plants to grow high enough to shade your solar panels and a great way to prevent this (and make your farm even more productive) is to keep grazing animals around. Cows are too large to graze under most solar panels (as well as being large and destructive) and goats will climb on the solar panels and chew the wires, but sheep are perfect. The space under the panels is also great for growing certain crops that prefer shade.

Sustainable agriculture + sustainable energy.

#ask#submission#sustainable agriculture#sustainable energy#green energy#renewable energy#solar panels#solar energy#solar farms#sheep#good news#climate change#climate change adaptation

227 notes

·

View notes

Text

Intro to U.S. Agriculture Book Recommendations

Requested by @languagesandpain

Healing Grounds by Liz Carlisle

If you're interested in agroecology this is a great place to start. It highlights a handful of Black, Latino, and Asian American farmers and their lives, history, and research. It's a great all-around book too because it touches on animal agriculture, produce, and mushrooms (which I don't see get talked about much), and also different methods like agroforestry and pasture systems.

Grain by Grain by Bob Quinn and Liz Carlisle

This book is basically the story of Bob Quinn and his farm, there's a lot of good info in it. This is the first book that really struck home to me that I need to listen to people in conventional agriculture even if I personally don't like it, because there's important experiences that need to be heard. It touches on topics like converting farms to more sustainable methods, heirloom crops, and how we deal with food/diet related science in the US. I don't have any health issues of note, but after reading this book I found an organic bread with Kamut wheat in it to see how it was, and it totally takes away any white on my tongue when I'm eating it daily. Pretty fascinating.

Perilous Bounty by Tom Philpott

This book widely covers major problems in US conventional agriculture, mostly covering major agriculture corporations and environmental impacts but also some labor issues, and small/mid size farm struggles. I'm not going to lie, this one is depressing. I generally do well with tough topics but near the end I had to put it down a few times because it was making me feel a bit hopeless. Which I fault the author with a bit for not dealing with better, because we need more hope to be able to believe these problems are fixable. He also doesn't cover the eastern US which irks me a bit because the south is a major agricultural region. But overall, a lot of great info and some interesting ideas for solutions near the end.

With These Hands by Daniel Rothenberg

I haven't actually read this one yet, but I've read sections. It looks like another tough read, but covers the experiences of migrant farmworkers across the US. Definitely trigger warnings for modern day slavery, racism, abuse, and more.

Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations

I found this one to be a bit pessimistic honestly, but I read it a while ago so I dont remember what exactly bothered me. But it's a good overview of agricultural collapse through history, soil science, and issues in soil today.

Lentil Underground by Liz Carlisle

(Can you tell I've read all of Carlisle's books yet). So this book didn't really make much of an impression on me. But I'm recommending it because if anything it kind of illustrates the tediousness of policy change, changing people's minds, running an unconventional farm. It's a bit boring compared to the other recommendations but if you're in the industry there's things to think about in it.

Non-book recommendations

For a while was listening to Real Organic Podcast. After about 10 episodes (not in order) you notice they start to really repeat a lot of ideas. But they have a lot of episodes that highlight problems with chemical use, water use, how movements like organic get co-opted by big corporations, and more.

I also recommend the news website Civil Eats. They post a lot of book recommendations, as well as cover a whole variety of agricultural issues across the world.

If anyone has any additional recommendations feel free to add on! I'm always looking for more books >:)

#not langblr#agriculture#agroecology#sustainable agriculture#regenerative agriculture#environmentalism#environmental justice#book recommendations

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

LOCAL FARMS >>>>> pt. 2

Guys they sell food. And it's affordable. And sustainable. And the money they get from you buying their food sustains them and their business and allows them to keep growing and selling affordable food and create a small community that appreciates local sustainable farming and their wonderful food.

BUY FROM THEM RAGAHSGAJG

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

So on dendryte's suggestion, I read a paper called "Feed your friends: do plant exudates shape the root microbiome?", and it is awesome and filled with ideas that were new to me, and all in all was very exciting. Like, I didn't even know about/remember border cells, and they apparently do a whole lot! I'm back from work now, so now I'm going to share the Questions I have, and am going to spend the weekend looking for sources on:

1. As crop rotation was developed for a tilled, monoculture system as a way to address the disease issues that pop up in such a system, is crop rotation actually beneficial in a no-till, truly polyculture setting where care is taken to support mycorrhizae?

As we know know that plants alter the population of bacteria in the soil, and that these population compositions differ between plant species, is it possible that there might be some benefits to planting the same crop in the same location if you're not disrupting microbe populations through tilling?

2. Since we know that applications of nitrogen can cause plants to kick out their symbiotic fungal partners, increasing their vulnerability to pathogenic fungi & drought, might it be better to place fertilizer outside of the root zone so as to force the plant to use the mycelium to get at it?

How far can mycorrhizal networks transport mineral nutrients? Are they capable of transporting all the mineral nutrients plants need? In other words, can I make a compost pile in the middle of the garden and be lazy and depend on the fungal network to distribute the goods?

3. How deep can fungal hyphe go? In other words, in areas with shallow wells, and thus fairly shallow water tables, can we encourage mycorrhizae enough to be able to depend on them for irrigation?

4. For folks on city water, does the chlorine effect plants' microbiome both above and below ground?

5. When do plants start producing exudates? If you had soil from around actively growing plants of the same species you're sowing, could the bacteria and fungi play a role in early seedling vigor & health?

6. Has anyone directly compared the micronutrient profiles of the same crop grown in organic but tilled settings against those grown in no-till, mycorrhizae-friendly settings?

7. Since we know that larger molecules, such as sugar, can be transported across fungal networks between different species (Suzanne Simard is where I first food this info) , have we checked for other compounds created by plants? Say, compounds used by plants to protect against insect herbivory?

8. Since we know blueberries use ericoid mycorrhizae rather than endo- or ectomycorrhizae (which are the two types used by most plants), but gaultheria (salal & winter green) use both ericoid & ectomycorrhizae, and alder uses both endo & ectomycorrhizae (and fix nitrogen too!), and clover use endomycorrhizae, might blueberries be more productive if there's a nearby hedge of salal/wintergreen, alder, and clover? Willows and aspens also both use endo & ecto, so they could be included, and the trees could also be coppiced for firewood or basketry supplies.

I'm going to spend some time this weekend reading research papers. If anyone happens to know any that address these (or related questions), please send them my way!

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm curious as to how well known these services are outside of ag communities.

The food distribution thing may or may not be less well-known because it is typically done through a government service or non-profit, but not always! And it is a service lots of small farm owners are doing.

#had to remake cause i always accidentally let the poll only be for a day. augh.#agroecology#sustainable agriculture#food justice

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Despite the Central Appalachia ecosystem being historically famous as coal country, under this diverse broadleaf canopy lies a rich, biodiverse world of native plants helping to fill North America’s medicinal herb cabinet.

And it turns out that the very communities once reliant on the coalfields are now bringing this botanical diversity to the country.

“Many different Appalachian people, stretching from pre-colonization to today, have tended, harvested, sold, and used a vast number of forest botanicals like American ginseng, ramps, black cohosh, and goldenseal,” said Shannon Bell, Virginia Tech professor in the Dept. of Sociology. “These plants have long been integral to many Appalachians’ livelihoods and traditions.”

50% of the medicinal herbs, roots, and barks in the North American herbal supply chain are native to the Appalachian Mountains, and the bulk of these species are harvested or grown in Central Appalachia, which includes southern West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, far-southwest Virginia, and east Tennessee.

The United Plant Savers, a nonprofit with a focus on native medicinal plants and their habitats, has identified many of the most popular forest medicinals as species of concern due to their declining populations.

Along with the herbal supply chain being largely native to Appalachia, the herb gatherers themselves are also native [to Appalachia, not Native American specifically], but because processing into medicine and seasonings takes place outside the region, the majority of the profits from the industry do too.

In a press release on Bell’s superb research and advocacy work within Appalachia’s botanical communities, she refers back to the moment that her interest in the industry and the region sprouted; when like many of us, she was out in a nearby woods waiting out the pandemic.

“My family and I spent a lot of time in the woods behind our house during quarantine,” Bell said. “We observed the emergence of all the spring ephemerals in the forest understory – hepatica, spring beauty, bloodroot, trillium, mayapple. I came to appreciate the importance of the region’s botanical biodiversity more than ever, and realized I wanted to incorporate this new part of my life into my research.”

With co-investigator, John Munsell at VA Tech’s College of Natural Resources and Environment, Bell’s project sought to identify ways that Central Appalachian communities could retain more of the profits from the herbal industry while simultaneously ensuring that populations of at-risk forest botanicals not only survive, but thrive and expand in the region.

Bell conducted participant observation and interviews with wild harvesters and is currently working on a mail survey with local herb buyers. She also piloted a ginseng seed distribution program, and helped a wild harvester write a grant proposal to start a forest farm.

“Economic development in post-coal communities often focuses on other types of energy development, like fracking and natural gas pipelines, or on building prisons and landfills. Central Appalachia is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. I think that placing a greater value on this biodiversity is key to promoting a more sustainable future for the region,” Bell told VA Tech press.

Armed with a planning grant of nearly half a million dollars, Bell and collaborators are specifically targeting forest farming as a way to achieve that sustainable future.

Finally, enlisting support from the nonprofit organization Appalachian Sustainable Development, Virginia Tech, the City of Norton, a sculpture artist team, and various forest botanicals practitioners in her rolodex, Bell organized the creation of a ‘living monument’ along Flag Rock Recreation Area in Norton, Virginia.

An interpretive trail, the monument tells the story of the historic uses that these wild botanicals had for the various societies that have inhabited Appalachia, and the contemporary value they still hold for people today."

-via Good News Network, September 12, 2024

#appalachia#united states#biodiversity#herbs#herbal medicine#herbalism#native plants#conservation#sustainability#sustainable agriculture#solarpunk#good news#hope

479 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Ladybugs aren’t just cute nursery rhyme stars. Beneath the charming spots and vibrant colors lie killer instincts. They’re effective predators and sometime agricultural allies in their hunger for plant pests like aphids. Entomologist Sara Hermann, Ph.D. is investigating how ladybugs’ “perfume”—the chemical cocktail that makes up their odor—might even become a tool for sustainable agriculture.

Join our host and museum curator Jessica Ware, Ph.D., to find out how the delicate dance of predator-prey interactions in the insect world could help protect our crops and gardens. The series is produced for PBS by the American Museum of Natural History.

#PBS Terra#solarpunk#ladybug#bug#bugs#aphids#Sara Hermann#sustainable agriculture#gardening#garden#farm#farming#Youtube

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s been lovely lately

#goats#cheese#sustainable agriculture#sustainability#Vermont#farm animals#cute goats#farming#farm core#cottagecore#cottage aesthetic#farm

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

⭐️Currently reading: The One-Straw Revolution by Masanobu Fukuoka ⭐️

‘Just playing or doing nothing at all, children are happy. A discriminating adult, on the other hand, decides what will make him happy, and when these conditions are met he feels satisfied.’

The synopsis calls it ‘Zen and the Art of Farming.’ This book is about his experience over 30 years of using the ‘do-nothing’ farming method. He lets his orchard and rice/barley fields grow wild without any pest controls or fertilizers. That’s the basis of it (kinda?) — but what makes this book amazing is that he goes deep into why it works for him. Explaining why he doesn’t have to use chemicals to treat weeds and pests. Into the full circle of life & how to actually grow ‘natural’ food. We always want bigger and better quality & focus on high yields and money. How disconnected we really are growing from nature in agriculture.

If you aren’t into agriculture or learning about the exact ‘whys’ of his experiences from growing rice, barley & citrus on his personal field —- skip to part 2 of the book. I honestly wouldn’t recommend skipping(it holds a lot of useful information), but after part 2 is where I really got interested.

It’s not only about farming though - it also incorporates our health, diet and how basic our knowledge is as humans. It makes you think.

Even this book being written in 1978 - it still holds up to today. We’ve had all this knowledge since then and we still continue to do industrial agriculture and live/eat the way we do. It’s eye opening, for sure.

I’m not completely finished yet - I have about 40 pages left - but that’s what I think so far ☺️ You should definitely give it a try.

#one straw revolution#sustainable agriculture#natural farming#masanobu fukuoka#agriculture#agriculture books#currently reading#sustainable gardening#grow organic#organic gardening#green manure#farming#eat locals#grow your own food#food not lawns#ecology#guerrilla gardening#indoor garden#container gardening#vegetable gardening#starting seeds#growing food#gardening blog#gardening tips#plant mom#plant life#homesteading#growing grains

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

22 ways to Go Organic on a Budget article

One of my constant goals is to increase how much of our food is organic. I'm no where near perfect at this (pregnancy cravings just had me ordering gluten free mint Oreos and Arizona green tea from Walmart lol), but in the spring and summer when most produce is in season I try to buy as much of our produce organic as we can afford. When I'm home with my parents the majority of my produce comes from their massive garden, all of our eggs come from their chickens, and all of our pork from their pigs. None of this is certified organic obviously, and they don't use organic animal feed, but I honestly still prefer these things. I love knowing exactly where my food comes from and how my meat was raised before harvest.

#organic#holistic#holistichealth#holisticwellness#crunchy mom#hippie mom#holistic health#holistic home#natural living#natural home#simple life#simple living#slow living#sustainable#sustainability#sustainable living#sustainable agriculture#ecofriendly#gogreen#sustainable home#homesteading#gardening#homemaker#homemaking#housewife#stay at home mom#traditional femininity#traditional gender roles#tradwife#tradfem

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Growing Microgreens: The Benefits of an Organic Edible Garden

This comprehensive ebook is your one-stop guide to cultivating a bounty of goodness on your windowsill or patio.

Inside, you'll discover:

• The magic of microgreens: Learn why these tiny powerhouses are packed with flavor and nutrition, and how to easily grow them year-round in minimal space.

• Organic gardening essentials: Master the fundamentals of creating a healthy and sustainable growing environment for your microgreens and edible plants.

• Step-by-step guidance: From sowing seeds to harvesting your bounty, we'll walk you through every step of the microgreen and organic gardening process.

• Gardening made simple: Design your dream organic edible garden, whether it's a windowsill box or a sprawling backyard plot.

• Plant power: Explore a variety of popular edible plants that thrive in organic gardens, along with harvesting and storage tips to enjoy your fresh produce for longer.

• Troubleshooting made easy: Learn how to identify and overcome common gardening challenges, ensuring your microgreens and plants flourish.

Go green and grow healthy with this empowering guide!

Bonus: Discover sustainable practices for an eco-friendly garden and tips for maximizing your harvest throughout the year.

Embrace the joy of growing your own food and unlock the vibrant world of microgreens and organic gardening today!

Unleash the Power of Tiny Greens: Growing Microgreens & Organic Gardening Success. Grow fresh, nutrient-packed microgreens and a thriving organic edible garden – right at home. Embrace the joy of growing your own food and unlock the vibrant world of microgreens and organic gardening today!

#books#nature#farming#science#agriculture#farm#skill#career#growing microgreens#organic gardening#edible garden#microgreen farming#sustainable gardening#homegrown produce#healthy living#indoor gardening#gardening tips#DIY gardening#nutrient-dense foods#fresh produce#natural food#eco-friendly gardening#sustainable agriculture#backyard farming#urban gardening

2 notes

·

View notes