#Brazilian Supreme Court judge

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Democracy Dies in Darkness" – WaPo

Alexandre de Moraes: “If Goebbels were alive and had access to X, we would be doomed,” de Moraes said. “The Nazis would have conquered the world.”

For the few ("hoi oligoi" < "ὀλίγος") who are subscribed, the link leads directly to the New Yorker's full article.

Source: The New Yorker, via LinkedIn

© The New Yorker 2025 (no copyright infringement intended)

#Democracy Dies in Darkness#WaPo is not what it used to be ?#The New Yorker Magazine#The New Yorker article#Alexandre de Moraes#Brazilian Supreme Court judge

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Woah woah woah. Twitter is shutting down in Brasil? I'm thankful for your mental health but what?

Yep.

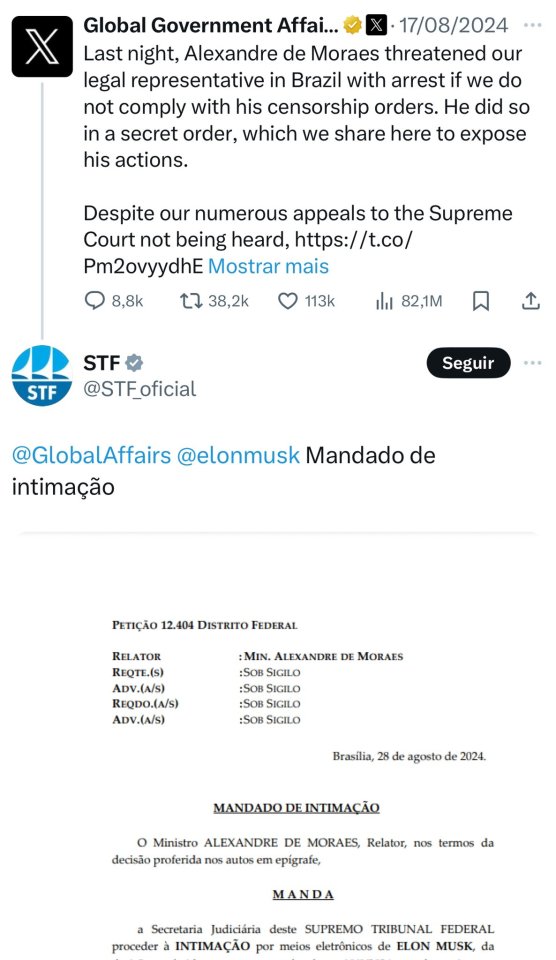

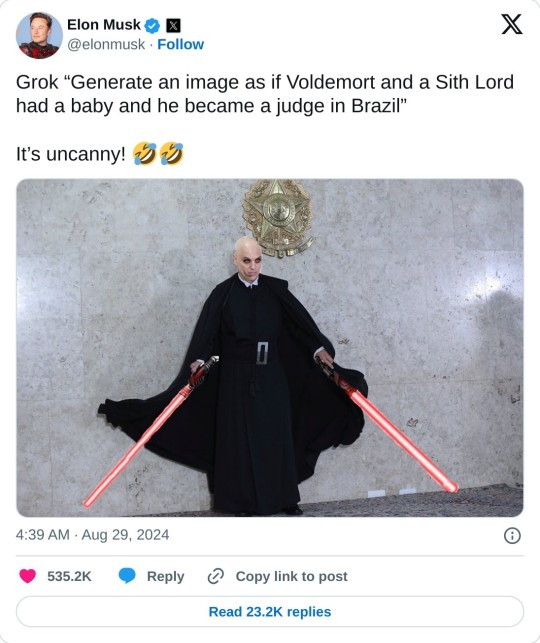

TLDR: Elon fired everyone in the Brazilian offices of twitter but legally Twitter can't continue existing in Brazil WITHOUT a legal representative. So now our Federal Supreme Court subpoened him to apoint a new representative or the website is getting shut down in the country

The long version with the context about the fight:

It all started when the supreme court started to shut down in the country profiles of brazilian people who had commited crimes using the website (an example is Monark, a dude who literally used his profile to say we should give n*zis and racists unlimited freedom of speech [he fled to the US to escape prison btw]).

Elon caught wind of this and decided to threaten our constitution and said that he would get the profiles back on because he wouldn't accept a government restricting "freedom of speech" on his platform. The supreme court issued a statement that if he did that, he would face a fee everyday for every account reactivated. It was money so he didn't do that (or maybe turns out he couldn't do it anyway and he was just lying for his lil fanboys).

This was all back at the start of the year but suddenly almost two weeks ago it was reported he fired every single employee in the offices of brazil, including the legal representative.

Then tonight, around two hours ago the official profile of STF replied and tagged elon with the doc of the subpoena because since they didn't have a legal representative, they couldn't do it in the proper way. The subpoena says that Elon has 24 hours to appoint a new guy for the job or the social is getting shut down in brazilian territory.

So we have 3 options for whats gonna happen in the next 24 hours:

Alexandre de Moraes (The guy who Elon started a one-sided beef with) backs down and doesnt shut down the website (highly unlikely)

Elon backs down and appoints a new guy so he doesnt lose the 4th biggest public of his site

Twitter gets shut down until Elon's manchild's ego gives in

thats all <3

Edit:

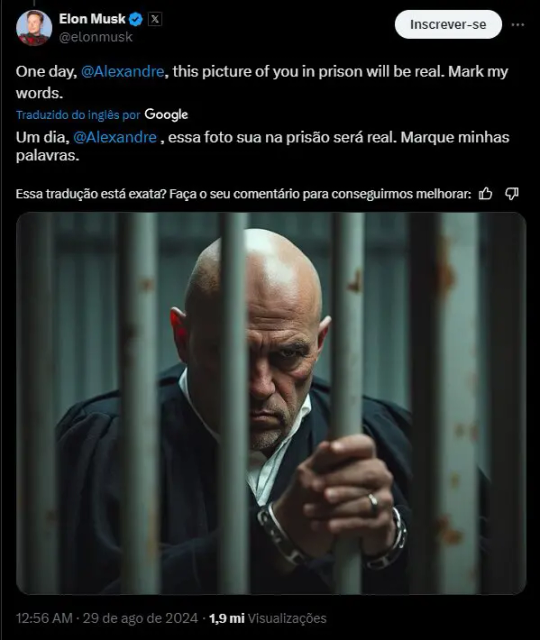

This was Elon's reply to the tweet. YES he is pathetic like that

Edit 2: it's currently 17:38 brasilia time of 30/08 and Twitter is bound to get disconnected soon, the order has been given by Moraes. People who use a VPN to access Twitter will get fined 50k reais (almost 9k dollars).

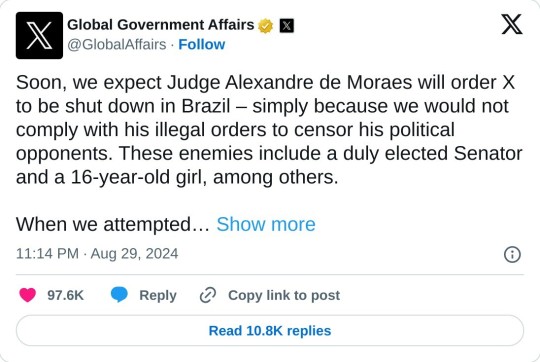

Yesterday a note was posted lying about Brazil being a dictatorship and saying that one of the people being censored is a 16yr old girl. The truth is that it's a grown ass man that use his daughters account to promote attacks on delegates, ministers, judges and other politicians. They also call orders to ban n*zi accounts "illegal orders" (WHICH ARE VERY LEGAL UNDER THE CONSTITUTION OF BRAZIL). They also say "we don't want every other country to have the freedom of speech laws the US has" meanwhile they've been trying to impose them in a sovereign state.

I would say what I want to say to Elon but unfortunately my mother taught me to keep those kinds of thoughts inside. Just know they're three letters <3

edit 3: twitter was officially unavailable on brazilian territory by the time it struck midnight of the 31st

Edit 4:

Translation: 🚨 NOW: Elon Musk is looking for executives to represent Twitter/X in Brazil, to negotiate the platform's RETURN in the country, reports Correio Braziliense.

he's going to do what cellbit said kkkmk he purposely let them suspend it, then after a few days he'll come out and be the savior of the brazilian people and say he only did it for us

Don't let elon fool you. He doesn't care and is probably only doing it because his investors are threatening him with money

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Elon Musk blinks first, bowing to pressure in Brazil to reopen X

The impasse had blocked the social media company from one of its most active markets.

For more than three weeks, a question has loomed over Brazil and much of the tech world: Who would back down first?

Would it be Elon Musk, whose refusal to comply with orders from a Brazilian judge had resulted in the suspension of the social network in one of its largest markets?

Or would it be Alexandre de Moraes, the taciturn jurist who issued the order?

This weekend appears to have brought an answer.

The social network X, formerly known as Twitter, said Friday that it had taken steps to comply with demands issued by the Brazilian Supreme Court to end the impasse that has severed the company from one of its most active markets. These included naming a representative in the country and blocking accounts that Moraes had accused of propagating misinformation and undermining Brazilian democracy. Much of the company’s fines have also been paid off.

Continue reading.

#brazil#brazilian politics#politics#twitter#elon musk#supreme federal court#alexandre de moraes#image description in alt#mod nise da silveira

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xandão (Chrome Period Drawing #20, based on a photograph of Alexandre de Moraes, the Brazilian Supreme Court Judge that banned Xwitter and Starlink), Deluxe Paint IV, 2024

#gif#art#xandao#black and white#pixel art#illustration#judge#brasil#STF#dpaint#amiga#webcore#color cycles#deluxe paint#pixels

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

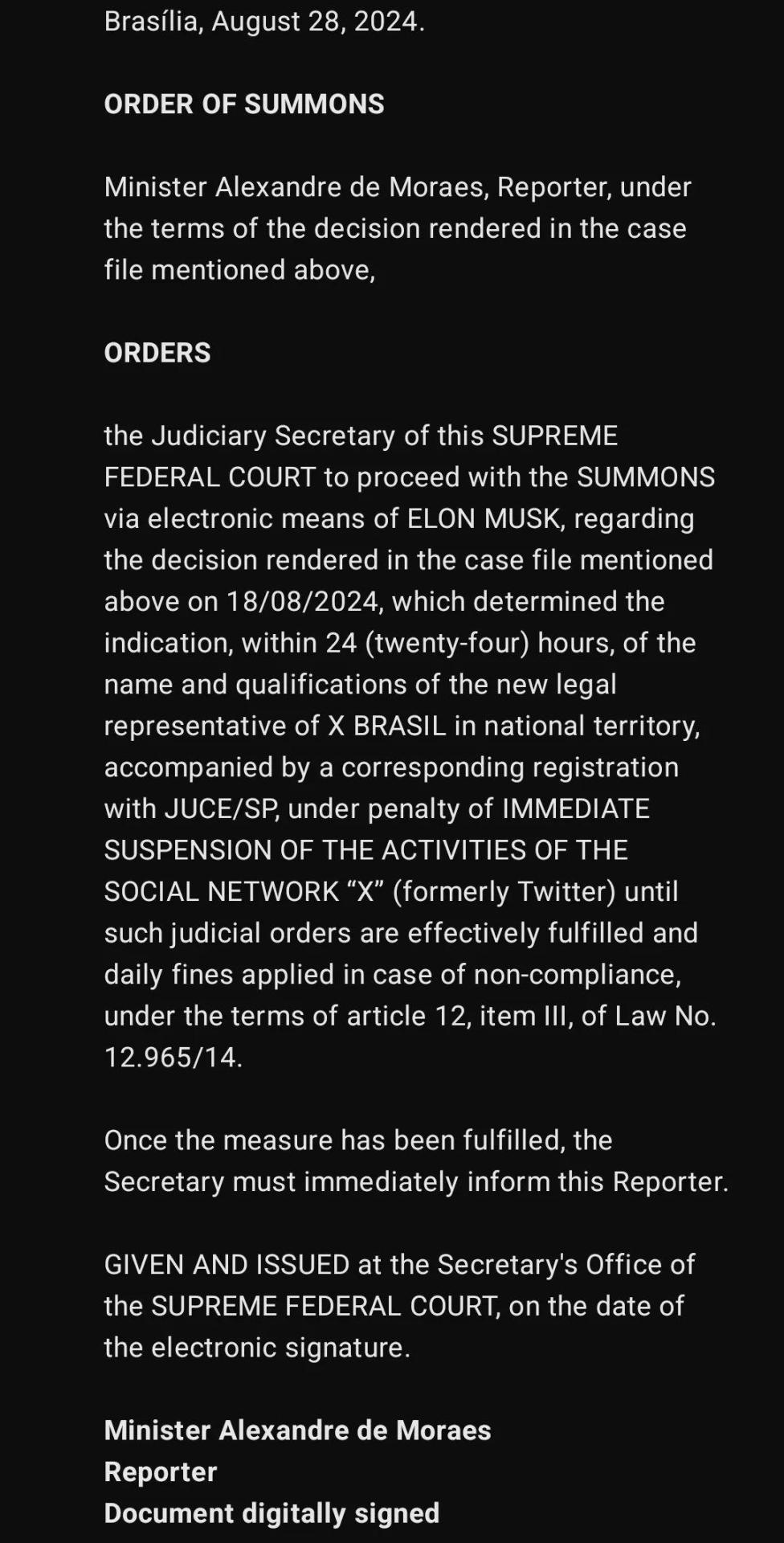

Elon Musk is threatening a Brazilian Supreme Court justice after the court issued a summons to him which threatens the suspension of Twitter if he does not comply within 24 hours.

To combat disinformation, Brazil gave a Supreme Court justice sweeping powers to order social networks to take down content he believed threatened democracy. Here's how the experiment led to a ban on X, the social network owned by Elon Musk.

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/31/world/americas/brazil-x-ban-free-speech.html?smid=threads-nytimes

Elon Musk claims this is a censorship, because previously he was ordered to ban and close a lot of far-rights account that spread fake news and hate online by that same judge. As protest, Musk closed X offices in Brazil - which means people losing their job or their income.

When free speech is interpreted as anything which matches the law (and viceversa). Under Elon Musk's Leadership, Twitter has approved 83% of censorship requests by authoritarian governments globally. The social network has restricted and withdrawn content critical of the ruling parties in Turkey and India, among other countries, including during electoral campaigns.

Since Musk assumed control in October 2022, the platform has received a total of 971 government requests, a significant increase compared to the 338 received between October 2021 and April 2022.

Prior to Musk's takeover, Twitter had agreed to 50 per cent of such requests, as indicated in their last transparency report. However, no transparency reports have been published since October 2022, making it challenging to assess the current situation. Nevertheless, data from the technology information portal Rest of World suggests that the compliance rate has risen to 83 per cent following Musk's leadership, which again contribute to detect what Elon Musk REALLY think about free-speech: this right is granted only if comply to what oppressive governments and far-right politician approves. Discrimination and criminal behavior are allowed and protected under Musk's Leadership, because targets minorities, immigrants and political oppositors. Musk is a conservative and apply censorship, he isn't the victim of a 'woke' complot lead against him. Musk is receiving the payment for his unlawful action.

Source: El Pais English

As far I can understand, without having many clues here, this order of summon says that Elon Musk refused to appoint a legal rapresentative for X Brasil. For some typology of corporates Brazil require a % of residents in management or a legal rapresentative, with power to vote and deliberate in meetings, to operate online in the country. Yeah. Law apparently seems to be applied to everyone except him.

Summons with translation.

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/28/technology/brazil-x-ban-elon-musk.html

Edit: A legal rapresentative is more a managerial position than what do you think of. Yes, it could be an attorney or a lawyer too, but still isn't simply the guy who defend the corporate's interests in court. In Brazil you need a % of residents in management position to operate. This was a problem issued also with WhatsApp and Telegram.

Edit 2 - 31th August 2024: I was curious about the consequences of Musk's decision to close X's offices in Brazil for his employees. Have they been fired? Suspended with or without salary? I didn't find anything. However, I found this article that adds some informations, like Musk declaring he did this to "protect his staff". However, his legal rapresentative is impossible to be found.

Edit 3 - 31th August 2024: Another article of NY Times that analyzes the matter.

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/18/world/americas/elon-musk-x-brazil.html

Update - 31th August 2024: Brazil has turned off Twitter. Musk’s genius is again on glorious display in losing the 7th most populous country in the world. Oh well. At least the Cybertruck is doing awesome.

Another Update - 31th August 2024: Musk is freaking out right now. He knows if he gets blocked in Brazil it is just a matter of time before other countries follow suit.

However, someone forgot to tell Musk that you get fined for using VPNs to access Twitter in Brazil before he posted this.

Also seems that for a tech genius Musk isn't very smart though, doesn't he know using a VPN will worth the same with apps as it does with a browser?

However, The Brazilian Supreme Court has moderated its first rule. First, even the VPN apps were targeted and should be banned from App store and Google Store to prevent people getting access to Twitter exclusively. Now, the Court realized that banning VPNs is too extreme, so they will only apply a 50k (about $8,900) fine for those caught accessing the platform.

Basically, you don't get fined for using VPNs, that would be too 1984. You might get fined if they FIND OUT that you're accessing X via VPNs, and this is exactly the kind of thing VPNs are designed to prevent.

Just a reminder, you can always access better platform than X, even on your phone. No app is needed.

VPNs are great tools to use worldwide to get around authoritarian and abusive government surveillance and blocking. Zero to do with Musk. And they can only catch you if you aren't savvy.

In a perfect world you shouldn't need to download any VPNs to access innocent contents, because democratic countries will never block a platform that gives informations and entertainment to people. In a perfect world you won't be stuck with platforms that are not free from disinformation and neo-nazi posts.

3rd Update - 31th August 2024:

Musk owns more of SpaceX than Zuck owns of Meta or Bezos owns of Amazon, fwiw. For all intents and purposes, Musk is Twitter, SpaceX, Neuralink and X.

I'm gonna add some technicalities here:

In Brazil there is something called "Corporate Personality" that protects the shareholders patrimony from the company's debts.

But... If you hide behind legal shenanigans in a fraudulent manner, "corporate personality" is bypassed and thus the court moves into your personal patrimony.

Elon is, personally and fraudulently, removing X office from Brazil so they don't obey Brazilian laws.

So the judges target him on his other shares: SpaceX and Starlink.

#vavuskapakage#elon musk#all my homies hate elon musk#elongated muskrat#fuck elon musk#fuck em#fuck elongated muskrat#elon musk is an idiot#elon musk is a fraud#elon musk is a moron#brazil twitter#twitter#x twitter#twitter x#twitter brazil#twitter ban#twitter brasil#fuck twitter#elon musk is an asshole#elon mask

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brazil’s supreme court has blocked efforts to dramatically strip back Indigenous land rights in what activists called a historic victory for the South American country’s original inhabitants.

Indigenous people celebrate the ruling in Brasilia. Photograph: Gustavo Moreno/AP

[…] Similar scenes played out across the Amazon region, which is home to about half of Brazil’s 1.7 million Indigenous citizens.

“[This is a] victory for struggle, a victory for rights, a victory for our history,” the Indigenous congresswoman Célia Xakriabá tweeted. “[All of] Brazil is Indigenous territory and the future is ancestral.”

[…] Casting her vote against a thesis a majority of justices decided was unconstitutional, judge Cármen Lúcia Antunes Rocha said: “We are caring for the ethnic dignity of a people who have been decimated and oppressed during five centuries of history.”

Brazilian society had “an unpayable debt” to the country’s native peoples, Rocha said.

The Indigenous rights group Survival International commemorated the defeat of what it called an attempt “to legalize the theft of huge areas of Indigenous lands”. Dozens of uncontacted tribes could have been wiped out had such efforts prospered, the group claimed.

Source: the guardian

#an anon asked me about this a few months ago#and maybe some of you want good news today#protecting indigenous people protects the Amazon from deforestation by the agricultural sector that proposed this change to strip the land#from the indigenous groups who actually own it

281 notes

·

View notes

Text

Former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro has been charged by prosecutors over an alleged coup plot to poison his successor. In an attempt to stay in office after his 2022 election defeat, the right-wing politician was allegedly involved in a plan to poison current President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, commonly known as Lula, and kill a Supreme Court judge. Prosecutor general Paulo Gonet said that Mr Bolsonaro and 33 others participated in the plan to keep him in power.

Continue Reading

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tom Phillips and Tiago Rogero at The Guardian:

Brazil’s former president Jair Bolsonaro has been charged with allegedly masterminding and leading a far-right conspiracy to cling to power through a military coup. The South American country’s attorney general, Paulo Gonet, levelled the charges against the radical rightwing populist and several key allies on Tuesday night. He accused Bolsonaro and six key associates of leading a criminal organization with an “authoritarian power project”. The alleged plot, he wrote, included a plan to poison Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and shoot dead Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes, a foe of the former president. Bolsonaro, who experts say could face between 38 and 43 years in jail if convicted, stands accused of crimes including being involved in an attempted coup d’état and an armed criminal association and the violent abolition of the rule of law. He has repeatedly denied breaking any laws and on Tuesday told reporters he was “not at all worried about these accusations”. The charges come three months after a bombshell 884-page federal police report accused Bolsonaro, who governed Brazil from 2019 until 2022, of playing a lead role in planning and organising a conspiracy designed to stop the leftwing victor of Brazil’s 2022 presidential election, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, taking power. Bolsonaro lost that vote to Lula but refused to accept defeat and on 8 January 2023 his hardcore supporters ran riot in the capital Brasília, trashing the presidential palace, congress and the supreme court in a bid to overturn the internationally accepted result. The attorney general’s office accused another 33 people of being part of the alleged plot including Bolsonaro’s former spy chief, the far-right congressman Alexandre Ramagem; his former defense ministers Gen Walter Braga Netto and Gen Paulo Sérgio Nogueira de Oliveira; his former minister of justice and public security, Anderson Torres; his former minister of institutional security Gen Augusto Heleno, and the former navy commander Adm Almir Garnier Santos. Netto has denied involvement in a coup plot. The other men are yet to publicly comment on the allegations. Perhaps most shockingly, the attorney general’s 272-page report claimed Bolsonaro had been aware of an alleged plot - which it said had “received the sinister name of ‘Green and Yellow Dagger’” - to sow political chaos by assassinating top authorities including Lula and the supreme court judge Alexandre de Moraes. “The plan was thought up and brought to the attention of the president of the republic [Bolsonaro], who agreed to it,” the document claimed. “[The plot] cogitated using weapons against the minister Alexandre de Moraes and killing Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva with poison.” News that Bolsonaro had been officially charged was welcomed by opposition politicians and progressive Brazilians who despise the former president for his anti-scientific handling of the Covid pandemic, his hostility to minorities, Indigenous communities and the environment, and his relentless attacks on Brazil’s democratic system. Gleisi Hoffmann, the president of Lula’s Worker’s party, called the formal accusations, “a crucial step in the defense of democracy and the rule of law”.

See what happens when far-right insurrectionists actually get held truly accountable? Former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro got charged with allegedly masterminding and leading a far-right conspiracy to cling to power through a military coup.

See Also:

AP, via HuffPost: Brazil’s Former President Bolsonaro Charged Over Alleged Coup That Included A Plan To Poison Lula

#Jair Bolsonaro#Brazil#Praça dos Três Poderes Storming#2022 Brazilian Elections#World News#Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva#Alexandre de Moraes

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Brazilian Supreme Court, a wide, low, glass-faced building with swooping colonnades, sits near the national legislature and the Presidential palace, on a vast paved expanse known as the Three Powers Plaza. It is as public a place as you can find in Brasília. Still, few people seemed to notice when, on November 13th, a middle-aged man dressed like the Joker parked near the court, walked a few paces away, and set off an improvised explosive device inside his car, igniting a fireball that rose above the pavement. He made his way to the front of the court, where a sculpture of blindfolded Justice sits holding a sword across her lap. The man reached into a backpack, removed a cloth, and threw it at the statue, apparently intending to set it on fire. Then, as security guards approached, he hurled two more bombs at the building and opened his jacket to show that he was wearing a suicide vest. While the guards looked on, he lay down in front of Justice and triggered another explosion, which thundered across the plaza, killing the man but leaving the statue unharmed.

The bomber was Francisco Wanderley Luiz, a fifty-nine-year-old locksmith from a small city in southern Brazil. When a police search team located the apartment where he had been staying, they sent in a remote-controlled robot first—a wise precaution, as it turned out. Wanderley had rigged a cabinet with another explosive device, which blew up when the robot approached.

In the febrile political atmosphere of Brazil, Wanderley’s public suicide inevitably had partisan implications. Investigators found that he had once run unsuccessfully for city council, as a member of the party dominated by the right-wing former President Jair Bolsonaro. For several years, Bolsonaro had engaged in a ferocious feud with the Supreme Court—and particularly with Alexandre de Moraes, a pugnacious jurist who is sometimes described as the second most powerful man in Brazil. After Bolsonaro took office, in 2019, de Moraes led an ever-expanding series of investigations into him and his family. As Bolsonaro’s supporters formed “digital militias” that flooded the internet with disinformation—claiming that political opponents were pedophiles, spreading blatant lies about their policies, inventing conspiracies—de Moraes fought to force them offline. Granted special powers by the judiciary, he suspended accounts belonging to legislators, business magnates, and political commentators for posts that he described as harmful to Brazilian democracy. His detractors called him a tyrant and an authoritarian, claiming that he was violating their rights.

In the fall of 2022, Bolsonaro ran for reëlection against Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a political veteran who has been the mainstay of the Brazilian left for decades. Bolsonaro insisted throughout the campaign, without evidence, that security flaws in voting machines made it possible to steal the election. At one point, he warned, “If need be, we will go to war.” After Lula took office, a mob of some four thousand Bolsonaro supporters gathered in the same plaza where Wanderley later blew himself up. In a spasm of rage, they trashed the Supreme Court, the legislature, and the Presidential palace—an uncanny reprise of the assault on the U.S. Capitol two years before.

Bolsonaro denied any involvement, and his supporters protested that he wasn’t even in Brazil at the time. But, to investigators, even his absence from Lula’s inauguration, the week before, seemed suspicious. Rather than observing the custom of handing the sash of office to the new President, Bolsonaro had flown to Florida, where he remained for three seemingly aimless months, meandering through Orlando malls and taking selfies with Brazilian expats.

Eventually, Bolsonaro returned to Brazil, and in June, 2023, he was found guilty of “abuse of political power” and the “improper use of communication channels” to sow distrust in the electoral system—not jailable offenses, but ones that barred him from office for eight years. His followers complained that he was the victim of a “lawfare” campaign, and Elon Musk took up the cause. On X, Musk repeatedly attacked de Moraes, referring to him as an “evil dictator cosplaying as a judge,” and calling for his impeachment. At rallies, Bolsonaro’s supporters waved banners with Musk’s image and chanted, “Thank you, Elon!”

After Wanderley carried out his suicide attack, de Moraes described it as yet another manifestation of the virulent rhetoric that had permeated the Brazilian internet. “It grew under the guise of a criminal use of freedom of speech to offend, threaten, coerce,” he said. The chief of the federal police, Andrei Passos Rodrigues, made it clear that he agreed. “Even if the visible action is individual, there is never just one person behind that action,” he said. “It’s always a group, or ideas of a group, or extremism, radicalism.” Both suggested that Brazil was engaged in a war over who held the power to determine political reality. On one side were de Moraes and his allies. On the other was an international coalition of right-wing influencers, including Bolsonaro, Musk, and, increasingly, President Donald Trump.

De Moraes rarely speaks to journalists, but he agreed to meet with me to talk about what he calls “the new extremist digital populism.” The first interview took place six weeks before Wanderley’s attack, in de Moraes’s office—an airy space with a wall of windows that look out toward Lake Paranoá. Since the spring, he had been clashing with Musk over social-media accounts that de Moraes said spread hate speech and malicious propaganda. When de Moraes called for their removal, X refused. When he imposed fines, they went unpaid, and eventually he froze bank accounts belonging to X and Starlink, Musk’s satellite network. In August, de Moraes increased the financial penalties and implemented a nationwide ban on X. Musk briefly circumvented the ban through Starlink, which provides internet service to many Brazilians, but he was evidently rattled. His representatives soon assented to de Moraes’s orders, including taking down the offending accounts and paying the fines. De Moraes collected five million dollars and lifted the ban. Still, he knew that the battle with Big Tech was not over.

In his view, the fight over the internet began a decade and a half ago. “The far right noticed, during the Arab Spring, that social media could mobilize people without intermediaries,” he said. “At first, algorithms were refined for economic purposes, to captivate consumers. Then people realized how easy it was to redirect this toward political power.” He cast social media as a defining force of our time. “If Goebbels were alive and had access to X, we would be doomed,” he said. “The Nazis would have conquered the world.”

De Moraes told me that Brazil offered a significant testing ground for efforts to assert political power through the internet. Brazilians are particularly active online—they are among the world’s heaviest users of X and WhatsApp. And, unlike in other countries, the judiciary runs elections. “The far right wants to seize power—not by saying they oppose democracy, because that wouldn’t gain public support, but by claiming that democratic institutions are rigged,” de Moraes said. “It’s a highly structured, highly intelligent populism. Unfortunately, in Brazil and in the U.S., we haven’t yet learned how to fight back.”

Brazilians often refer to de Moraes as Xandão, or Big Alex, but he is not especially tall. He is, however, conspicuously fit; he runs, lifts weights, and spars with a Muay Thai partner several times a week. At fifty-six, he has a shaved head and a face that seems made for cross-examination, with a heavy brow, sharp cheekbones, and a jutting chin. He stares without appearing to care whether he’s being rude.

In our first meeting, de Moraes recalled that Musk had described him as “a cross between Voldemort and a Sith”—that is, between the bald “Harry Potter” villain and a bald “Star Wars” villain. “He mixed the two and said that’s me,” de Moraes told me, and laughed. “To be honest, I find it amusing.” He did seem offended, however, by Musk’s refusal to obey his orders: “Like all other companies, this one must comply with Brazilian law. The one who escalated the disobedience was the company under the direct command of its largest shareholder. And at that moment Musk became personally responsible as well.”

In conversation, de Moraes often veers between jokes and brusque legal assertions. He grew up in São Paulo, in a middle-class family; his father was a businessman and his mother was a professor. As a young man, he attended law school at the University of São Paulo—a training ground for the Brazilian political class which, over the centuries, has educated a third of the country’s Presidents. De Moraes was ambitious, and he rose quickly. By his late twenties, he had become a prosecutor and written a best-selling book on constitutional law. In his thirties and forties, he held a series of government postings in São Paulo, as the city’s secretary of transportation and as the state’s secretary of justice and eventually its head of public security—essentially, the police commissioner. At the time, no one would have accused him of left-wing sympathies. He was a law-and-order advocate who professed zero tolerance for crime. “The most developed countries are those where people respect the law—where people know that if they break the law there will be consequences,” he told me. He commanded a vast force of more than a hundred thousand officers, and sometimes sent in uniformed men and armored vehicles to disperse protests.

Then as now, de Moraes tended to shrug off criticism. “To be honest, I’ve always been controversial,” he told me. Yet there are moments in his career that seem questionable even to his supporters. One was his leap to national politics. In 2016, President Dilma Rousseff, a protégée of Lula’s, was impeached by a group of right-wing legislators who included Bolsonaro. Vice-President Michel Temer took over, but his tenure was shadowed by a potential scandal: a blackmailer had hacked his wife’s phone and threatened to release compromising photographs of her. The story was made for the tabloids—Temer was seventy-five years old, and his wife, a former beauty queen, was thirty-two. When Temer explained his predicament, de Moraes quickly assembled a team of investigators to track down the blackmailer and arrest him. As if in gratitude, Temer named him Brazil’s minister of justice.

In office, de Moraes had a performative flair that did little to calm his detractors. Video from the time shows him striding through a field of illegal marijuana, slashing down the plants with a machete. “When I became minister of justice, the entire left called me a coup plotter,” he told me, with a shrug. “They hated me. Now the far right hates me.” A popular social-media meme plays on the change in his public image. It shows the footage of him hacking through the field of pot—but in reverse, so that his machete seems to make plants spring up from the ground.

De Moraes had been the justice minister for less than a year when a vacancy opened on the Supreme Court, and Temer made him a justice. The court has eleven members, each serving until the age of seventy-five, and they wield extraordinary power. “When it comes to the extent of authority of the Supreme Court, we have no clear limits,” Felipe Recondo, a Brazilian journalist who has written several books on the court, told me. “They argue everything of importance, from taxes to racial issues to abortion.” Unlike in the U.S., many consequential cases go directly to the court, without needing to pass through appeals. De Moraes expected to attract controversy again; perhaps he even welcomed it. But, he said, “neither my colleagues nor I could have predicted that Brazilian democracy would be at risk. It reached a level that was unimaginable.”

Before Bolsonaro entered the 2018 Presidential election, few political observers took him seriously. After retiring from the Army, having risen no higher than captain, he had spent decades in the legislature, where he was distinguished mostly by his vitriol. He once described a female political opponent as too ugly to rape. Another time, he said that he would rather have a dead son than a gay one. Perhaps most alarming, he was openly nostalgic for the brutal military dictatorship that ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985.

That regime began with a coup that ousted the left-wing President João Goulart. It was backed by the Lyndon Johnson Administration, during a grim era of U.S. support for Latin American dictatorships that purported to fight Communism. Brazil’s was particularly zealous. In twenty-one years, tens of thousands of citizens were detained and tortured, more than two hundred were killed, and another two hundred or so were disappeared.

In March, a panel was convened at the University of São Paulo’s law school to commemorate the fortieth anniversary of Brazil’s restoration of democracy. (De Moraes teaches a weekly course at the school, which occupies a neoclassical edifice in the city’s dilapidated downtown.) There were a half-dozen speakers, nearly all women, including a historian and two law professors. As an audience of about five hundred listened intently, they recalled their own youthful efforts to restore democracy and insisted on the importance of preserving it.

Cármen Lúcia Antunes Rocha, the country’s only female Supreme Court justice, linked the fight against the regime with the current conflict over social media. “To be free is to be unshackled, to move beyond the conditions of oppression that marked our past,” she said. “Instead of machines being subject to humans, humans are becoming subject to machines, and this brings new forms of tyranny. We are at risk of being chained by algorithms—by systems that know very well whom they serve.”

The final speaker was Marcelo Rubens Paiva, a prominent writer whose father was among the regime’s victims. In 1971, Rubens Paiva, a forty-one-year-old civil engineer and politician, was abducted from his home in Rio de Janeiro and tortured to death, leaving his family bereft. Marcelo, one of his five children, recounted the story in his memoir “I’m Still Here,” which inspired this year’s Academy Award winner for Best International Feature.

The men who abducted Paiva were indicted by federal prosecutors in 2014—but they have been protected by an amnesty law, passed as the regime was coming to an end, which has effectively kept the country from reckoning with the savagery of military rule. When Paiva spoke against the amnesty at the event, he received a standing ovation. “It’s the law that my mother fought for decades to overturn—not for revenge, but for justice,” he said. “And to this day we are still fighting for the truth.”

Part of what shocked people about Bolsonaro’s candidacy was that he didn’t just refuse to disavow the military regime; he called for it to return and finish remaking Brazilian society. “If a few innocent people die, that’s all right,” he said. The reverence for Paiva seemed to bother him particularly. When a statue was erected in Paiva’s memory, Bolsonaro spat on it—the kind of provocation that would eventually make him a star on social media.

Bolsonaro’s biggest advantage in the 2018 election, other than his gift for trolling, was that Lula was unable to run: he had been imprisoned on corruption charges, which were later reversed. Bolsonaro won by a wide margin, and took office promising to be a “defender of freedom.” Two of his sons also won seats in the legislature. But there were questions from the start about how online disinformation had skewed the results.

In the run-up to the election, the Brazilian internet was filled with an incredible volume of false and inflammatory claims. People passed around images purporting to show boxes of illicit ballots on a truck bed, or a left-wing politician posing with Fidel Castro. An analysis by Agência Lupa, a prominent Brazilian fact-checking organization, found that only four of the fifty most shared images were legitimate. Many of the most outrageous falsehoods were aimed at Bolsonaro’s opponent, Fernando Haddad. One meme showed a check for millions of dollars, ostensibly paid to Haddad by a criminal gang. Another, particularly widespread one claimed that he was distributing penis-shaped baby bottles in elementary schools, as part of a “gay kit.” A study published later found that almost eighty-four per cent of Bolsonaro voters believed it.

Those who called attention to disinformation became targets. Agência Lupa recorded as many as fifty-six thousand threats a month. Among the bolsonaristas’ greatest antagonists was Patrícia Campos Mello, a reporter at Brazil’s foremost newspaper, Folha de São Paulo. Campos Mello, now fifty-one years old, has spent decades covering major events in Brazil and around the world, including the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and Syria. When I got in touch to ask about her reporting on Bolsonaro, she responded from a frontline bivouac in eastern Ukraine.

During Bolsonaro’s campaign, the Brazilian press began reporting on how a group of his close advisers, including his son Carlos, established what they called the “hate cabinet,” which generated online propaganda and disseminated it through a network of supporters and bots. (Carlos and other associates have denied this.) Campos Mello broke a series of stories about businessmen who were financing a torrent of WhatsApp messages that denigrated Haddad. “They were hiring marketing agencies that offered assembly lines of disinformation,” she told me. “They had dozens of people inside rooms, sending thousands of messages to databases of voters they bought on the gray market.”

Campos Mello secured overwhelming evidence of how the firms operated, including photos, messages, and testimony from former employees. When the stories were published, she told me, “the Bolsonaro trolls went nuts.” They spread claims that she had been fined by the Supreme Court for spreading false information, that the story had been paid for by Lula’s party, and that she was a Communist. Strangers called her phone, shouting insults and warning that they would attack her. “Then they started sending messages threatening my son, who was six at the time,” she recalled. “People yelled at me in the street, hacked my phone.”

She cancelled public appearances, and the newspaper hired her a bodyguard. But she published more stories, showing how Bolsonaro’s social-media operation had gained access to voter databases and hired foreign agencies to promote falsehoods online. Bolsonaro sued for defamation. The suit failed, but the campaign of intimidation only grew more intense.

In February, 2020, Campos Mello had just returned from covering Bolsonaro’s visit with the Indian Prime Minister when the Brazilian legislature convened a hearing about disinformation in the electoral campaign. At the hearing, one of her sources testified—but with representation from a lawyer with ties to the far-right party of Bolsonaro’s Vice-President. To her astonishment, the source claimed that she had offered sex in exchange for information. His testimony also included pictures of the social-media operation, which inadvertently confirmed her reporting, but that fact was quickly overshadowed. Soon after the hearing, Bolsonaro’s son Eduardo gave a speech from the floor of the legislature, accusing her of seducing sources to entrap his father.

“It was the end of the world,” Campos Mello said. Bolsonaro supporters in the legislature and on the internet called her a whore. The worst invective was fuelled by an influencer named Allan dos Santos, she said: “He posted porn stuff about me, tagged me, and called on his supporters to make memes.” Trolls created fake pornographic images of her, and some threatened rape. A few days after the hearing, Bolsonaro told a group of supporters that Campos Mello “wanted to get the scoop at any price.” In Portuguese, the word for “scoop” also means “anus.” After that, the memes and rape threats began referring to anal sex.

Finally, Campos Mello decided to sue Bolsonaro and a group of his supporters, including Eduardo and dos Santos. She also published recordings of the interviews with her source, to demonstrate that there was no sex involved. Meanwhile, Lula’s Workers’ Party filed a suit, based on her reporting, that argued that Bolsonaro’s online manipulations disqualified his candidacy. The case eventually landed before de Moraes and his fellow-justices, who ruled unanimously against overturning the election—though de Moraes warned that such tactics could be disqualifying in the future. “Justice is blind, but it is not foolish,” he said.

Over time, Campos Mello was largely vindicated. WhatsApp acknowledged the irregular use of its platform during the election and promised to take legal action against the marketing agencies involved. New laws were passed to prohibit mass messaging on behalf of candidates. And all the men Campos Mello accused of slandering her were found guilty. “So far, Allan dos Santos lost the lawsuit, and owes me money, but he is currently hiding in the U.S.,” she told me. “Eduardo Bolsonaro lost in several courts and is now appealing to the Supreme Court, saying that he has parliamentary immunity. But immunity to suggest that journalists are basically whores?”

The right to free speech is guaranteed by Brazilian law, but it is less absolute than in the United States. As de Moraes notes, the country’s constitution, ratified in 1988 after a history of coups and the recent military dictatorship, was designed in part to “resist anti-democratic movements.” Racist speech is forbidden. So are “crimes against the democratic rule of law” (such as spreading falsehoods about the electoral system) and “crimes against honor” (such as claiming that your opponents are raping children).

Among the messages spread by Bolsonaro’s “hate cabinet” were insistent accusations that the Supreme Court was illegitimate. Before long, threats began circulating online about kidnapping or killing justices. Ordinarily, the prosecutor general’s office would investigate such threats, but it apparently never did. So the Supreme Court, invoking a statute that empowered it to investigate any “violation of criminal law within the premises of the Court,” opened its own inquiry—essentially becoming victim, prosecutor, and judge. De Moraes was put in charge of the effort. He was experienced in police work, and, unlike most of the other justices, he was adept at political maneuvering. As Recondo pointed out, he was also unusually tenacious. “If you give him a mission, he’ll pursue it to the end,” he said. “And, for him, this case was like blood in front of a shark.”

Bolsonaro was already surrounded by scandal. His son Flávio had been found to be paying a salary to the wife and the mother of a fugitive policeman who was wanted for running a murder-for-hire operation. There were questions about the family’s real-estate holdings, which included some fifty properties around Rio—purchased, implausibly, on Bolsonaro’s government salary. De Moraes began to investigate, and, Recondo said, he never really stopped: “Bolsonaro kept committing crimes, and so Xandão kept leading new investigations.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Bolsonaro dismissed the danger, even as the country endured one of the highest death tolls in the world. When the health ministry stopped publishing daily statistics on the spread of the disease, de Moraes ordered it to begin releasing the data within forty-eight hours. Eventually, demonstrators began to gather outside the Supreme Court, angry about the investigations into Bolsonaro and about pandemic restrictions. Bolsonaro sometimes made appearances. On one occasion, he rode into the crowd on a horse, giving a jaunty thumbs-up; on another, he buzzed overhead in a military helicopter, waving from the window. Protesters insisted that they were fighting for freedom, which frustrated de Moraes. “The far right has successfully manipulated these words to make people believe that they are the true defenders of democracy,” he told me. “It’s an impressive feat of brainwashing.”

At times, though, de Moraes’s investigations strained the limits of his authority. He blocked more than a hundred social-media accounts without providing explanations to the platform. After he banned X, he imposed a fine of almost nine thousand dollars a day on anyone who accessed the platform through a V.P.N.

In one controversial case, eight businessmen were griping about the government in a WhatsApp group, and one of them wrote, “I prefer a coup to the return of the Workers’ Party.” De Moraes had their homes searched and their bank accounts frozen. (Two of the men are still under investigation, but the cases against the other six have been abandoned, for lack of evidence.) Rafael Mafei, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s law school, said that the decision was “on the razor’s edge of legality.” Yet the justices had reason for concern. One official told the Times that extremists had been found to be talking about assaulting justices, tracking their movements, and examining a floor plan of a judicial building.

The court that de Moraes had joined was not particularly liberal. The justices had resisted taking up the decriminalization of abortion, which is largely illegal in Brazil. They had ruled both for and against Lula in cases concerning corruption allegations and his eligibility for office. But during the Bolsonaro years the justices came together in support of de Moraes. “The court has always been like a weathervane—flexible, adaptable, basically a reflection of most of Brazilian society,” Recondo said. “The Supreme Court was eleven islands. Bolsonaro united them.”

In June, 2022, Brazil’s judiciary elected de Moraes to lead the Superior Electoral Court, which oversees the country’s general elections. At his inauguration—held in a formally decorated chamber, with several Presidential candidates present—he set out guidelines for the campaign. His speech contained an unmistakable warning for Bolsonaro. “Freedom of speech is not freedom to destroy democracy,” he said. “Freedom of speech is not freedom to spread hatred and prejudice. Freedom of speech does not allow the spreading of hate speech and ideas contrary to the constitutional order.” Bolsonaro, who had sat apart from the other candidates, frowned furiously. When de Moraes praised the integrity of the electoral system, he pointedly refused to applaud.

Bolsonaro’s efforts to discredit the election had already found allies abroad. His son Eduardo had travelled to the United States, where the businessman and Trump ally Mike Lindell helped him stage a presentation about electoral fraud in Brazil. Steve Bannon amplified the accusations. De Moraes told me that the right wing used similar tactics in both countries: “In the U.S., Trump accused mail-in voting of being fraudulent. In Brazil, Bolsonaro accused electronic voting machines of being fraudulent.” (De Moraes likes to joke that, if Brazilians voted by sending smoke signals, the right would claim that the Electoral Court was blowing the smoke off track.) “It’s not about the voting method,” he said. “It’s about declaring the system rigged, to justify seizing power to ‘fix democracy.’ ”

To an alarming extent, Bolsonaro’s campaign worked. Reports of disinformation on the internet increased more than sixteen thousand per cent from the previous election. Three-quarters of Bolsonaro supporters told pollsters that the results of the vote could not be trusted. De Moraes scrambled to respond. The Electoral Court expanded his authority to shut down online attacks on the integrity of the election. He and his fellow-jurists issued dozens of decisions, restricting political propaganda, disqualifying candidates who misrepresented themselves, and deploying federal agents to insure safety on election day. When highway police stopped buses carrying voters from leftist strongholds to polling places, he ordered them to desist.

On election night, de Moraes went on television to announce that Lula had won. To demonstrate unity, he had assembled senior officials from around the country to stand with him. He told an elated crowd, “I hope from this election onward the attacks on the electoral system will finally stop—the delusional speeches, the fraudulent news.”

Yet many Brazilians remained anxious. In an interview with me at the time, Lula expressed concern that Bolsonaro’s efforts to retain the Presidency had powerful supporters. I had recently visited an Army garrison outside São Paulo where hundreds of loyalists, many of them wearing the yellow and green of the Brazilian flag, thronged the entrance, praying, banging drums, and demanding that the military intervene to keep Lula from office. Similar protests were taking place at garrisons across Brazil, and it seemed obvious that they had at least the passive acquiescence of the armed forces. “We need to find out who is financing them,” Lula told me, “because this is not spontaneous.”

Bolsonaro’s allies rejected warnings that the protests would turn violent. His son Flávio, borrowing a tactic from the right wing’s response to the January 6th attacks, told a Brazilian newspaper that in the U.S. “people followed the problems in the electoral system, were outraged, and did what they did. There was no command from President Trump, and there will be no command from President Bolsonaro.” But de Moraes knew that Bolsonaro was determined not to give up. “We suspected that something might happen during the inauguration—especially because, just a few days earlier, there had been a bomb attempt at the Brasília airport,” he told me. “And on December 12th, after the certification of the election results, rioters stormed the federal-police headquarters. So we were prepared to insure that nothing would happen on inauguration day.” After the ceremony passed without incident, the security forces felt that the threat was over, he said. “But a week later it happened—the January 8th attack.”

During the riots, vandals breached the Supreme Court building, broke open a cabinet containing de Moraes’s robe, and carried the door into the crowd as a trophy. De Moraes seemed personally affronted. “These people are not civilized,” he said in a speech later. “Just look what they did.” He began issuing arrest warrants within hours of the attack; more than a thousand people were eventually detained. “The biggest risk was the possibility of a domino effect,” he told me. “Would military police forces in other states—some of which supported Bolsonaro—also rise up? Would certain governors support the coup attempt?” He went on, “I had to act immediately, in the middle of the night.” To neutralize officials whom he suspected of aiding the uprising, he suspended the governor of the Federal District and ordered the arrest of the district’s secretary of security and the commander of its military police. (The case against the governor has been shelved; the two other men deny wrongdoing.) “This sent a clear message to the entire country,” de Moraes said. “We will not tolerate chaos in Brazil.”

Elon Musk, without apparent irony, has accused de Moraes of being an unelected autocrat. “How did Alexandre de Moraes become the dictator of Brazil?” he tweeted. “He has Lula on a leash.” More thoughtful critics note that de Moraes leads far more inquiries than any other justice, and that many are kept sealed, making them difficult to assess. Certainly, some of the inquiries into Bolsonaro are for trivial offenses. One accused him of illegally pawning luxury watches given to him by Middle Eastern governments.

Recondo said that de Moraes had benefitted from Brazilians’ affinity for tough guys: “We revere caudillos—strongmen who make decisions that go beyond the limits of the law.” Yet he believed that de Moraes’s campaign against disinformation was neither personal nor ideological. “Xandão really believes in the importance of the case, and moreover he is supported by his fellow-justices.” The risk was in creating unaccountable authority. “I personally can’t say whether it’s a good thing that one man has so much power,” he told me. “Because in the end we don’t really know who de Moraes is and what he might do.”

Some Brazilians argue that the concerns about social media should be addressed through legislation rather than litigation. “I do not believe this discussion should be taking place in the Supreme Court,” the congresswoman Tabata Amaral told me. “It should be taking place in Congress, where the public can discuss and debate the issues.”

Amaral, who is thirty-one, has been in the legislature for six years. After studying government and astrophysics at Harvard, she joined a center-left party and built a reputation as an advocate for public education. She achieved early prominence for a hearing in which she questioned Bolsonaro’s hapless education minister—a six-minute interrogation so embarrassing that he was fired soon afterward.

Together with another legislator, Amaral spent several years promoting legislation to hold social-media companies responsible for fake news and hate speech. But, each time they presented the bill, the tech platforms came after them, she told me. Spotify and Instagram spread critical messages, and YouTube displayed an “urgent alert,” warning content creators that the bill would harm them. Google took out full-page newspaper ads and put a link on its home page, just below the search bar, claiming that the legislation “could increase confusion about what is true or false in Brazil.” Eventually, the bill was pulled, and now Amaral and her allies were focussed on smaller initiatives. They had recently succeeded in restricting cellphones in schools, a modest step toward reducing social media’s power over children.

Part of the problem is that, in the Brazilian legislature, corruption and criminality are so endemic as to be inextricable from the job of governance. Amaral lamented that the failures of Congress had left the Supreme Court to intervene. “There is something fundamental about the democratic process,” she said. But she acknowledged that, without the court’s actions, Brazil’s democracy would be at much greater risk.

In some ways, Brazil has stronger legal guardrails than the United States. “If you are convicted of a criminal offense, you cannot run for political office,” Amaral said. “Trump would not have been reëlected here.” But, even though Bolsonaro was forbidden to seek reëlection, he could still do a lot of damage. He had already wrested a significant constituency from Brazil’s traditional conservatives. “Now you have to go to the extreme right if you want to be a bolsonarista,” she said. Amaral opposes expanding abortion rights, so the left doesn’t always see her as a natural ally, but her views on social media make her a target of the right. She has been called “Xandão with a skirt,” and her opponent in the most recent election launched social-media attacks blaming Amaral for her own father’s suicide. “The reality is that, as with Trump, if Bolsonaro is against you, you’re fucked,” she said.

Amaral’s co-sponsor on the Fake News Law, as it became known, was Alessandro Vieira, a fifty-year-old former state police chief from the rural northeast. Vieira, elected as an anti-corruption crusader, had supported Bolsonaro in 2018. After witnessing his social-media abuses, though, he began working on the bill. In the 2022 election, he supported Lula.

Vieira told me that the goal of legislation should be to hold platforms accountable, not to penalize users. “There’s not a single comma in the text of the law criminalizing freedom of expression,” he said. But he’d found the bill impossible to pass. Brazil had devised a framework of internet law “in a more romantic era, when people still thought of the internet as a neutral, democratic space,” he said. “Now the vast majority of Congress is afraid of Big Tech’s retaliation. Imagine running for office with the algorithm working against you!” In his view, the court’s efforts to control social media were an uncomfortable necessity. “This ongoing inquiry is authoritarian, and authoritarian tools should always be fought,” he said. Yet, for now, “it’s the only possible solution.”

The issue was a global one, he added: “I think all countries will face it, and none of them are prepared—except maybe dictatorships like China or Russia, which have their own information ecosystems.” Democracies would be more vulnerable. Gesturing at his phone, he said, “The venom of communication from this little device makes part of the population applaud it and agree.”

After the January 8th attack on the Brazilian capital, Bolsonaro ridiculed the idea that the riots represented a coup attempt. The protesters, he said, were nothing more than “little old women with Brazilian flags and Bibles under their arms.” Later, investigators found that several of his close associates had documents outlining schemes to forcibly keep him in office.

I asked de Moraes how close democracy had come to falling in Brazil. “There was definitely a risk,” he replied. “And there still is.” He noted that military officers were involved, along with senior commanders of the military police who guard the capital. All were now facing prosecution. “The strategy was to occupy government buildings—not necessarily to destroy them,” he said. “But you can’t control a mob. Their real goal was to enter the buildings, refuse to leave, and create a crisis so severe that the Army would be forced to intervene. Once the military arrived, they would request support for a coup. But the plan failed. Even though some military leaders supported the coup, the armed forces as an institution realized that no other power would side with them.”

When I asked de Moraes if he believed that Bolsonaro had masterminded the uprising, he dodged the question, saying that the investigation was in the hands of the federal police, which is independent from the Supreme Court. “Since I may have to rule on this case, I can’t comment,” he told me. Weeks later, the findings became public, in an eight-hundred-and-eighty-four-page report that cited Bolsonaro as a direct participant in a coup plot. The objective was not just to take over the government; there was also an operation, code-named Green and Yellow Dagger, to kill Lula and his running mate and to “neutralize” de Moraes. So far, five men, including police and military officers and a close Bolsonaro confidant, have been arrested. (They have all denied wrongdoing.)

The plotters coördinated through a Signal chat, called World Cup 2022, in which each identified himself as a national team: Austria, Germany, Ghana. They tracked de Moraes’s movements for weeks—during which, he told me, he attended a ceremony with Lula and travelled to São Paulo for a birthday lunch with his family. On December 15th, after he returned to Brasília, a group of heavily armed assailants surrounded his house, planning to kill or kidnap him, discard their phones, and escape. At the last minute, though, a message went out to the chat group, calling off the strike. (“Abort . . . Austria.”) De Moraes surmised that they had failed to secure support from the military; the day before, a proposal to annul the election and announce a state of siege had circulated among the leaders of the armed forces, but several had refused to sign on. De Moraes suggested that his life had been saved by connections in the armed forces, forged during his time as justice minister. “I joke with my security team that I couldn’t die,” he told me. “The hero of the movie has to continue.”

After Bolsonaro became a suspect in a coup plot, authorities seized his passport, to prevent him from leaving the country. But he and his allies hoped to get help from abroad. When Trump won reëlection, last November, Bolsonaro told the Wall Street Journal, “Trump is back, and it’s a sign we’ll be back, too.” Before Trump’s Inauguration, video circulated of Bolsonaro seeing off his wife at the airport and explaining morosely that she would attend in his place.

Trump has made few public statements about the situation in Brazil, but there are hints that he shares Bolsonaro’s frustrations with being censured for lying on social media. On January 20th, the White House released a statement complaining that the Biden Administration had “trampled free speech rights by censoring Americans’ speech on online platforms . . . under the guise of combatting ‘misinformation,’ ‘disinformation,’ and ‘malinformation.’ ”

On February 19th, Trump Media filed suit against de Moraes in the U.S., accusing him of censorship for ordering the social-media platform Rumble to remove the account of Allan dos Santos, the Bolsonaro supporter who helped lead the campaign against Campos Mello. (The Brazilian government has unsuccessfully sought to have dos Santos extradited from the U.S.) De Moraes described the lawsuit as “completely baseless,” adding, “Just as I cannot, here in Brazil, issue a ruling that mandates something in the United States, no judge there can declare that my order in Brazil is invalid. But it’s a political maneuver, which ended up getting press coverage.”

Later that month, the Georgia congressman Rich McCormick released a statement that aligned Bolsonaro with Trump and Musk. “The indictment of former President Jair Bolsonaro is not about justice—it is about eliminating political competition through judicial lawfare, just as President Trump was targeted before making the greatest political comeback in history,” he wrote. McCormick also argued that, by placing limits on Musk’s business in Brazil, de Moraes was violating Americans’ rights to free speech: “The United States cannot allow foreign judges to dictate what Americans can say, read, or publish.” He called for Trump and Congress to take action, writing, “Moraes and his enablers must face real consequences, including Magnitsky sanctions, immediate visa bans, and economic penalties.”

Other Republicans soon convened a hearing, in which the C.E.O. of Rumble and other speakers were invited to discuss a “crisis of democracy, freedom, and rule of law” in Brazil. Representative Chris Smith, of New Jersey, accused Lula and de Moraes of “the political abuse of legal procedures to persecute political opposition,” adding, “Friends don’t let friends commit human-rights abuses.” During the testimony, Bolsonaro’s son Eduardo led a rowdy contingent of Brazilian sympathizers in the audience.

Eduardo, who spent the night of Trump’s election at Mar-a-Lago, cheering along with the crowd, has increasingly presented himself as an adjunct of the Administration. Last month, he announced that he would take a leave of absence from his congressional seat to move to the U.S., so that he can urge Trump to intervene on his father’s behalf.

He already has an ally in Musk, who has stirred up the Brazilian right by claiming that it is suffering some of the most severe censorship in the world, at the hands of “an outright criminal of the worst kind.” Last April, Jair Bolsonaro held a rally on the beach at Copacabana, where an enormous crowd gathered to applaud his calls for “free expression.” Bolsonaro urged his supporters to give Musk a special ovation. “He’s a man who’s had the courage to show—already with some evidence, and more will surely come—where our democracy is heading and how much freedom we’ve lost,” he said. Later, when an X user asked archly why there had been no such rallies for de Moraes, Musk replied, “Because he is against the will of the people and, therefore, democracy.”

In the days after Wanderley blew himself up outside the Supreme Court, Lula began receiving foreign dignitaries at the G-20 summit, in Rio. At an event that week, the First Lady, Janja Lula da Silva, spoke about the imperative of fighting misinformation. When her speech was interrupted by the sound of a ship’s horn from a nearby harbor, she cracked, “I think it’s Elon Musk. I’m not afraid of you.” Then she added, in English, “Fuck you, Elon Musk.”

Janja’s comment caused a brief media sensation, and Musk responded, on X, “They will lose the next election.” But little else came of it, at least publicly. While Trump aimed threats and ultimatums at Mexico, Canada, and Panama, he was quiet about Brazil. In mid-March, the new Administration levied tariffs on steel, a major Brazilian export, but the announcement was made without commentary.

Still, when I saw Lula the morning after the tariffs took effect, he suggested that a showdown was coming. “There’s something in the air that worries me, which is the weakening of the democratic system,” he said. “In Europe, half of the twenty-seven countries already have right-wing authoritarian regimes. In Latin America, we see that anti-democratic, anti-institutional movements are also growing, and half of society is in favor of this.”

He suggested that the internet made it nearly impossible to govern. “I don’t think that in any country in the world we still have a sophisticated way to insure sovereignty,” he said. “The nation-state is very weakened, and it’s not just Brazil. It’s the U.S., China, everyone.” In a previous era, he said, “authoritarianism meant closing Congress, shutting down the judiciary, or putting troops in the streets. Now someone can speak to two hundred and thirteen million Brazilians without ever having been to Brazil.” When I mentioned that Musk’s Starlink satellite system was being used extensively by illegal gold miners who are devastating the Brazilian Amazon, Lula nodded grimly. “I visited the region and saw the predominance of Musk’s antennas,” he said. “We will not let someone who hates our administration, who hates democracy and our justice system, take control of the information of a country and a region like the Amazon.” Slapping the table, he said, “No company, no matter how powerful it is, will put our democracy at risk.”

Lula said that Brazil was working with the U.N. Secretary-General to devise a proposal for an international treaty on regulating social media. Less promisingly, he said that Brazil would raise the issue at a summit this July for the BRICS nations, with representatives attending from China, India, South Africa, Russia, and Indonesia—countries that have largely addressed their problems with online discourse by criminalizing dissent.

In March, I met de Moraes again at his office. He seemed more relaxed than he had five months before. By then, the prosecutor general had charged Bolsonaro and thirty-three others with fomenting a coup. (Bolsonaro denies the charges, claiming political persecution.) “The responsibility of each person now has to be determined in court, because this is when they will present their defense,” de Moraes said. “But the entire narrative of political persecution, the claim of personal enmity, all of that has collapsed, because it wasn’t just the federal police that accused them—the prosecutor general himself decided to press charges.”

I asked whether there was a scenario in which Bolsonaro could regain power. “It’s possible that Bolsonaro will be acquitted in the criminal case, because the trial is only just beginning,” de Moraes said. “But he has two convictions from the Superior Electoral Court for ineligibility. So there’s no possibility of his return—because both cases have already been appealed and are now in the Supreme Court. Only the Supreme Court could reverse them, and I don’t see the slightest possibility of that happening.” De Moraes acknowledged that Bolsonaro’s wife or one of his sons could run for President, with his endorsement. But, he said, “none of them—whether his children or his wife—have the same relationships with the armed forces that he had.”

In the coming months, the court will issue a momentous ruling on internet regulation. Under current laws, digital platforms are liable for users’ content only if they have ignored a court order to remove it. The court now has to decide whether they can be held liable before such an order is issued—obliging internet companies to carry out exhaustive policing of their users.

De Moraes cast such regulations as a means of taking back control. Social media is “now the greatest power of all,” he said. “Not only does it influence people, but it generates the most advertising revenue in the world, giving it the financial strength to influence elections.” He compared tech corporations to the East India Company, the colonial-age trading firm that dominated many of the countries where it operated. “They want to create a new East India Company to control the world,” he said. “They don’t want to respect any country’s jurisdiction, because, in reality, they seek to be immune to nations.”

De Moraes’s most stringent actions have only inflamed Bolsonaro’s followers. In the streets, it has become common to hear complaints that free speech is dead and that the Supreme Court has dictatorial power. Oliver Stuenkel, a prominent political scientist in São Paulo, largely supports the court’s actions, but says that its assertiveness carries risks. “Brazil ended up being the poster child for how you protect democracy over the past few years,” he said. “The challenge is how to insure that the court goes back to normal, because I think it’s not healthy for any democracy to have the Supreme Court be a key political actor all the time.”

But de Moraes does not regard the crisis as over. “I believe President Trump’s recent actions will push governments to realize that if they don’t act now to control social media it will be too late,” he said. European leaders were already considering stricter rules. In August, French officials arrested the founder of Telegram, for allowing his platform to host criminal endeavors that ranged from drug trafficking to terrorism. (Telegram denies wrongdoing.) De Moraes noted that he had suspended Telegram three years ago, after it repeatedly flouted court orders. More recently, he suspended Rumble, for failing to maintain a legal representative in Brazil. “People are going to start saying I’m persecuting everyone now,” he joked. “At this rate, I’ll be accused of persecuting Trump, too.” He seemed unconcerned by the prospect of pressure from the U.S. “They can file lawsuits, they can have Trump speak,” he said. “If they send an aircraft carrier, then we’ll see. If the aircraft carrier doesn’t reach Lake Paranoá, it won’t influence the ruling here in Brazil.”

As we finished talking, de Moraes walked me out past a display of a few prized objects. They included a jersey from his beloved Corinthians soccer team and two wooden effigies of Afro-Brazilian deities. He explained that they were Xangô and Exu—“law and order,” he said. Wait, I said. Isn’t Xangô a war god? De Moraes just smiled and ushered me through the door.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

To anybody wondering what exactly happened to twitter on Brazil here's the full version of the story coming from a brazilian:

-Elon closes the branch offices in Brazil as some sort of protest.

-Supreme court sends an email to the legal representative to ask for the removal of about 14 far right/nazi accounts.

-Twitter doesn't respond, a daily fine of 20.000 reais and an arrest warrent for the national administrator (15 days to 6 months + fine).

-Elon takes away the coutry's legal representative. Foreign companies need an office and/or a legal rep to be allowed to operate in Brazil.

-The official twitter account posts about being censored in Brazil, mentioning by name the judge who had sent the intimation and arguing that it wasn't made public. The judge in question then commented under the post, leaving the whole document for anyone to read as they like. Twitter has 24 hours to appoint a new rep and pay their more then 150 million reais in accumulated fines or it'll be blocked in Brazil.

-Elon says he will not comply with the Supreme court's decisions and instead resorts t posting corny AI generated images on his account.

-24 hours pass with no other negotiations from Twitter and as such the process of blocking the site as well as shutting down related Starlink accounts and freezing both of their bank assets starts. (https://noticias-stf-wp-prd.s3.sa-east-1.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/wpallimport/uploads/2024/08/30171714/PET-12404-Assinada.pdf)

-At this point the brazilian army sends a message to the supreme court stating that they were using Starlink for their own communications.

Elon had no problems with blocking accounts in other countries like in India but he had long been attacking the brazilian government since the 2022 election where former far-right president Jair Bolsonaro lost. Elon had been eyeing up brazilian lithium, Starlink was primarily sold to illegal miners in the Amazon and the military had been using it to coordinate about mineral deposits. Anyone can clearly see Elon's true intentions were to spread misinformation and destabilize the country for his own gain, we already know what his position with South America is when Bolivia nationalized it's lithium. Please spread the truth and don't believe this coward's lies, Brazil is a free, democratic sovereign country and he will stop at nothing until it's back at where it was in the 60's if it meas he'll have to spend slightly less money to make his stupid cars.

#brazil#elon musk#twitter#tesla#starlink#spacex#alexandre de moraes#to the americans reading please for the love of god don't let Trump win#It'll only make things worse for everyone who lives in the global south#look up about the brazilian military dictatorship

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Im coming back to Tumblr, and as much as it's not important to anyone, the reason is actually socially and politically interesting and i wanna explain it.

So, some context before anything, im Brazilian, grew up a Tumblr kid in from 2016 to about 2018, left for a good while, then i got a Twitter ( i refuse to call it X ) cause of Animation School during 2022, and now im migrating back to Tumblr, and it's cause Brazil is actually banning Twitter, giving a 8,912 dollar fine to anyone who uses a VPN to acess it and to top it off blocked Starlink's financial resourses in Brazil, the reason being justified and absolutely nuts that it happened too, at least in my conception.

So, from 2018 to 2022 the Brazilian president was Jair Bolsonaro, basically the dummer and more openly facist Brazilian version of Trump ( and that's a whole can of worms that im not gonna get into cause this post is already bound to be massive ), and on the end of 2022 presidental elections were held and Bolsonaro lost to Lula, a left leaning guy that will 100% sacrifice his morals for money and power ( but ended up being, sadly, the least worst option on that election, kinda like Biden ). So Bolsonaro started discrediting the electoral results on the internet with the help of other far-right politians and surprisingly ( or not ) Elon Musk. Following these series of inflamatory accusations from Bolsonaro and the far-right there were a few riots and then his following ( and most recent facist movement of Brazil ) stormed the Capitol in January 8th 2023 with enabling from the Brazilian police and military forces ( which sadly kinda work as it's own conservative cell seperate from the government due to Brazil's badly resolved Military Dictatorship issues ), politicians were evactuated before they entered, but when they did they tore down and stole priceless diplomatic gifts and works of art all over, but since it was mostly elderly people they were detained and jailed pretty quickly, even with the police's unwillingness allowing tons of them to escape.

And a huge investigation was open to see if the Coup was organized by political figures or not, led by supreme court judge Alexandre de Moraes. And well, from the involvement of the police force blocking highways so rural and poor communities couldn't vote, to a general testifying that Bolsonaro presented him papers detailing a organized planned Coup that didn't happen ( that were later found to be in a liutenant-colonel's house ), to Musk stepping in himself to discredit a deny Judge Moraes' requests to ban the accounts of people involved in the coup and in spreading missinformation about the Covid-19 vaccines back in the pandemic, it was obvious political figure's were neck in deep in shit, and Musk's box-shapped visage was no different.

So, cause of his involvement in this crazy mess, various personal attacks on Judge Moraes and the fact that brazilian facist cells are finding refuge on Twitter without any sort of reprimanding from the plataform, Judge Moraes threatened arresting Twitter's Brazilian representative. Elon Musk's response was to completely shut down Twitter's offices in Brazil, leaving them as a rougue agent with no representative on the eyes lf the law, and so Moraes responded by blocking Starlink's financial resources here and threatening to shut down Twitter for good in Brazil if Elon keeps disrespecting and delegitimazing Brazilian democracy and law, Musk responded to this by throwing more anti-democratic tamper tantrums and posting edited pics of Moraes as Darth Vader or someone of the sort ( i don't watch Star Wars ) like the little facist troll he is. And that's why Brazil ( Twitter's 6th biggest userbase ) is just gonna vanish from there today or soon enough, and why im here now again! And let me tell you something, not having character limitations and being able to say "FUCK YOU ELON MUSK" without getting kicked to the curb is absolutely FREEING.

So, prehaps expect a influx of Brazilians even though most will go to Bluesky, and don't expect me to cover politics anytime soon, maybe expect me to cover history though.

Thanks for reading. ♡

#brazil#politics#twitter#X#geopolitics#world news#brasil#noticias#política#semi serious#elongated muskrat

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

X has clashed with de Moraes over its reluctance to comply with orders to block users. "Brazil blocks Musk’s X after company refuses to name local representative amid feud with judge"

"The justice said the platform will stay suspended until it complies with his orders, and also set a daily fine of 50,000 reais ($8,900) for people or companies using VPNs to access it."

“When we attempted to defend ourselves in court, Judge de Moraes threatened our Brazilian legal representative with imprisonment. Even after she resigned, he froze all of her bank accounts,” the company wrote.

X has clashed with de Moraes over its reluctance to comply with orders to block users.

The looming shutdown is not unprecedented in Brazil.

Lone Brazilian judges shut down Meta’s WhatsApp, the nation’s most widely used messaging app, several times in 2015 and 2016 due to the company’s refusal to comply with police requests for user data. In 2022, de Moraes threatened the messaging app Telegram with a nationwide shutdown, arguing it had repeatedly ignored Brazilian authorities’ requests to block profiles and provide information. He ordered Telegram to appoint a local representative; the company ultimately complied and stayed online.

X and its former incarnation, Twitter, have been banned in several countries — mostly authoritarian regimes such as Russia, China, Iran, Myanmar, North Korea, Venezuela and Turkmenistan. Other countries, such as Pakistan, Turkey and Egypt, have also temporarily suspended X before, usually to quell dissent and unrest. Twitter was banned in Egypt after the Arab Spring uprisings, which some dubbed the "Twitter revolution," but it has since been restored.

A search Friday on X showed hundreds of Brazilian users inquiring about VPNs that could potentially enable them to continue using the platform by making it appear they were logging on from outside the country. It was not immediately clear how Brazilian authorities would police this practice and impose fines cited by de Moraes.

By GABRIELA SÁ PESSOA, BARBARA ORTUTAY and DAVID BILLERAugust 30, 2024