#Cheyenne River Sioux

Text

Gov. Kristi Noem, a Trump lickspittle, is banned from 15% of her state of South Dakota. She is one of the contestants for the number two position on Trump's national ticket.

As South Dakota governor Kristi Noem vies for a top position in a second Trump White House, she appears to be more focused on shoring up her vice-presidential chances than on making allies at home — to the point that she is no longer welcome in around 15 percent of the state she governs.

Over the past few months, Noem has made several comments about alleged drug trafficking on Native American reservation lands, infuriating a number tribes in the state. In February, the Oglala Sioux Tribe banned her from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, the fifth largest in the United States, for claiming without evidence that drug cartels were connected to murders on the reservation.

The ban did not dissuade her from making more incendiary remarks. In March, Noem said at a community forum in Winner that there are “some tribal leaders that I believe are personally benefiting from cartels being there and that’s why they attack me every day.” When tribal leaders demanded an apology, Noem doubled down, issuing a statement to the tribes to “banish the cartels.” In response, the Cheyenne River Sioux forbade Noem from setting foot on their reservation, the fourth largest in the U.S. On Wednesday, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, the sixth largest in the U.S., banned her as well. On Thursday, a fourth tribe, the Rosebud Sioux, followed suit.

So far, four tribes are banning Noem:

Oglala Sioux

Rosebud Sioux

Cheyenne River Sioux

Standing Rock Sioux

Alleged drug cartels on tribal lands in South Dakota are the local equivalent of millions of migrants illegally voting in 2020. Bullshit is not just a GOP specialty but a dedicated lifestyle.

#south dakota#kristi noem#drug cartels#bullshit#tribal lands#native americans#noem banned on tribal lands#oglala sioux#standing rock sioux#rosebud sioux#cheyenne river sioux#donald trump#trump running mate#election 2024#vote blue no matter who

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem (R) is now banned from all tribal lands in the state after the Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe voted to bar her from their reservation Wednesday, citing her repeated claims that tribal leaders work with drug cartels.

Noem sparked the controversy in March when she said tribal leaders benefit from the presence of cartels operating on their land.

“We’ve got some tribal leaders that I believe are personally benefiting from the cartels being there, and that’s why they attack me every day,” the governor said at a forum in March. “But I’m going to fight for the people who actually live in those situations, who call me and text me every day and say, ‘Please, dear governor, please come help us in Pine Ridge. We are scared.’”

#Kristi Noem puppy killer#Kristi Noem dog killer#Kristi Noem goat killer#kristi noem#Cheyenne River Sioux#Crow Creek Sioux#Flandreau Santee Sioux#Lower Brule Sioux#Oglala Sioux#Rosebud Sioux#Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate#Standing Rock Sioux#Yankton Sioux#south dakota#typical lying republican#typical republican#sioux

1 note

·

View note

Text

It’s official: All nine of South Dakota’s tribes have now voted to ban Gov. Kristi Noem (R) from their lands.

The final tribe still holding out hope for a productive relationship with the state’s governor, the Flandreau Santee Sioux, made the decision to join their counterparts Tuesday, just a week after telling The Daily Beast that they had no plans to do so.

A tribal leader told the Argus Leader that the Flandreau Santee Sioux executive council made the decision after hearing from a number of citizens who urged them to banish Noem—saying that many on the reservation were “uncomfortable and upset” with the council’s decision to wait so long in the first place. One attendee of the council’s Tuesday meeting told the local newspaper that the matter led to a “pretty heated discussion.”

Noem angered Indigenous American communities earlier this year by suggesting that tribes in her state were in league with Mexican drug cartels and blaming Indigenous parents for their children’s poor academic performance—leaving them unemployed and with “no hope.”

The comments led to her to be rapidly declared persona non grata by most of the tribal nations in South Dakota, starting with the Crow Creek, Sisseton Wahpeton, Oglala, Cheyenne River, Standing Rock, and Rosebud Sioux tribes, which account for nearly all of the reservation land in the state—almost 20 percent of the its total area.

Leadership of the Yankton Sioux Tribe has also voted to express its support for a similar ban, though it has yet to make an official decision on the matter.

Prior to its decision, leaders of the Flandreau Santee Sioux tribe reportedly held one last meeting Sunday with Gov. Noem in the Capitol, one they described to the Argus Leader at the time as “respectful and productive.”

Noem released her own statement following the meeting, writing that it was “never my intent to cause offense by speaking truth to the real challenges that are being faced in some areas of Indian country.”

“It is my hope that the Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe will give us the opportunity to partner together in a way that can be an example for all,” she added.

But just two days later, the tribe’s leadership committee decided that it just could not let her comments go unpunished.

“We need to stand in solidarity with our fellow tribes in South Dakota, the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ,” Tyler Rambeau, a tribal leader, told the local newspaper during a recess in Tuesday’s meeting. “We do not want to come up on the wrong side of history in this moment.”

When reached for comment on her banishment from tribal lands, Gov. Noem told The Daily Beast: “I only want to speak truth to the real challenges that are being faced in some areas of Indian Country. I want to focus on solutions that lead to safer communities for all our families, educational outcomes for all our children, and declining addiction numbers for all our people. We cannot tackle these issues without addressing the problem: dangerous criminals who perpetuate violence and illegal activities in all areas of our state. We need to take action. It is my hope tribal leadership will take the opportunity to work with me to be an example of how cooperation is better for all people rather than political attacks.”

#us politics#news#republicans#conservatives#gov. kristi noem#south dakota#Indigenous Americans#Argus Leader#the daily beast#2024#Flandreau Santee Sioux#Crow Creek#Sisseton Wahpeton#Oglala#Cheyenne River#Standing Rock#Rosebud Sioux#Yankton Sioux Tribe#racism

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Corrine Skye Killsprettyenemy

Born July 10 1950 on the Standing Rock Reservation (Íŋyaŋ Woslál Háŋ) in Fort Yates, North Dakota

Oakland, California

#Corrine Killsprettyenemy#Corrine Skye Killsprettyenemy#Standing Rock Sioux Tribe#Standing Rock Reservation#Íŋyaŋ Woslál Háŋ#Fort Yates#North Dakota#Cheyenne River Reservation#Mobridge#South Dakota#Mobridge High School#Black Hills State University#Mary Mount University#project director#Bureau of Indian Affairs#owner of Takota International Org#Second Chance Employment Group#Red Feather Development Group#mother#grandmother#beloved aunt and sister#may she rest in peace#<3

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letters To The Editor Policy:

The West River Eagle welcomes letters up to 250 words. Letters to the editor are limited to one per month per person.

Profanity, name-calling, or personal attacks will not be published, nor will letters deemed to be in poor taste. Libelous or slanderous statements will also not be published.

Letters to the editor must be clear, accurate, and signed by the author. For verification purposes, letters to the editor must include full name, home address, and day and evening phone numbers. Contact information is for our purposes only – we will not share it with anyone else. Anonymous letters and letters written under a pseudonym will not be printed.

Letters may be edited for length, grammar, and accuracy. Letters will be published on a space-available basis, and there are no guarantees they will be published the week they are submitted.

The West River Eagle will not accept letters to or about political candidates 30 days before an election.

*Letters to the editor are not the views of the West River Eagle staff – they are solely the opinions of the author.

To submit a letter to the editor, send an email to [email protected]

Events, businesses, and human individuals or groups can be submitted with relevant story and contact information to [email protected] as well.

DISPLAY ADVERTISING DEADLINE: 12:00 NOON Monday

LEGAL ADVERTISING DEADLINE: 5:00 p.m. Friday

#westrivereagle #oglalalakota #lakota #cheyenneriversiouxtribe #cheyenneriver #eaglebutte #southdakota

#cheyenne river#eagle butte#oglala lakota#south dakota#westrivereagle#lakota#cheyenne river sioux tribe

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tribal Leaders Sign Historic Co-Stewardship Agreement with National Forest Service in the Black Hills

“This landmark co-stewardship effort will feature storytelling in various formats at the Pactola/He Sapa Visitor Center, educating the larger public and helping current and future generations of Native People connect with their own creation stories and cultural identities.

On June 6, leaders of the Cheyenne River, Standing Rock, Oglala, Rosebud, and Crow Creek Sioux Tribes gathered in the He Sapa — the Black Hills — to sign an historic Memorandum of Understanding at the newly renamed Pactola/He Sapa Visitor Center with U.S. Forest Service officials. Together, they’re beginning a process of sharing Indigenous cultural heritage with visitors from all over the world. Leaders said that they want to see young, Native children visit the Black Hills and experience the importance of the landscape with a deep understanding of their own heritage.

Previously known as the Pactola Visitor Center, the seasonal facility welcomes more than 40,000 visitors annually from Memorial Day through Labor Day — and approximately another three million people pass through the area each year.

This effort has been several years in the making, though the process hit a snag during the Trump years. When tribal leaders initially proposed the concept to the U.S. Forest Service in 2018, the idea was heard but not taken seriously. Persistence pays, however, and the efforts of many relatives and allies eventually led the Forest Service to agree.

We hope this is just the tip of the iceberg. It’s critical that Lakota — and all Indigenous — stories and history be shared from an authentic perspective with those who visit our homelands. To that end, please stay tuned this summer. I can’t tell you too much about it yet, but we’ll soon be launching an ambitious program that can help ensure Native stories are told — and Native tribes are funded — on occupied Indigenous homelands across Turtle Island. “

Via the Lakota People’s Law Project

#indigenous#native american#ndn#good news#nature#environmentalism#black hills#stewardship#lakota#dakota#nakota#oceti sakowin

267 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marcella Ryan LeBeau is a member of the Two Kettle Band of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe and lives in Eagle Butte, South Dakota. Her Lakota name is Wigmuke Waste Win (Pretty Rainbow Woman) Her great-grandfather, Chief Joseph Four Bear (Mato Topa), signed the Fort Laramie Treaty in 1868. Her grandmother, Louise Bear Face, was related to Rain In The Face who took part in the Battle of the Little Horn.

Marcella served as a nurse in WWII becoming a 1 st Lieutenant in the Army Nurse Corps. The army service took her from the USA to Wales, England, France, and Belgium. Since receiving the French Legion of Honor Award on June 6, 2004, in Paris France, on the occasion of the 60th Anniversary of D-Day, Marcella has been requested to participate at many Veterans’ events, speaking of her military experience in World War II. Marcella served one term as District 5 council representative for the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. She is also honored to speak to the youth at elementary, high school, and college venues when she is invited.

In 1992 and 1995 Marcella and her son, Richard went to Glasgow, Scotland with interest in the return of the Ghost Dance Shirt that was taken from Wounded Knee in 1890. After negotiations, the ghost shirt was returned by the Kelvin Grove Museum. George Craeger, with the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show, sold some artifacts to the museum and donated a Ghost Shirt. It’s now held at the Heritage Cultural Center at the South Dakota Historical Society in Pierre, South Dakota.

After retiring as the Director of Nursing from the Indian Health Service in Eagle Butte, Marcella, and her granddaughter, Bonnie opened a machine quilting shop located in Eagle Butte. They make a variety of quilts. The main feature of their shop is the star quilt frequently used by the Lakota people for honoring and naming ceremonies, memorial give-aways, etc. which are traditional of this area’s native people.

Marcella having raised a family of eight children is an advocate for the Lakota language and culture, youth, veterans, elderly, upholding treaties, and wellness.

Credit: text & photos from wisdomoftheelders.org

42 notes

·

View notes

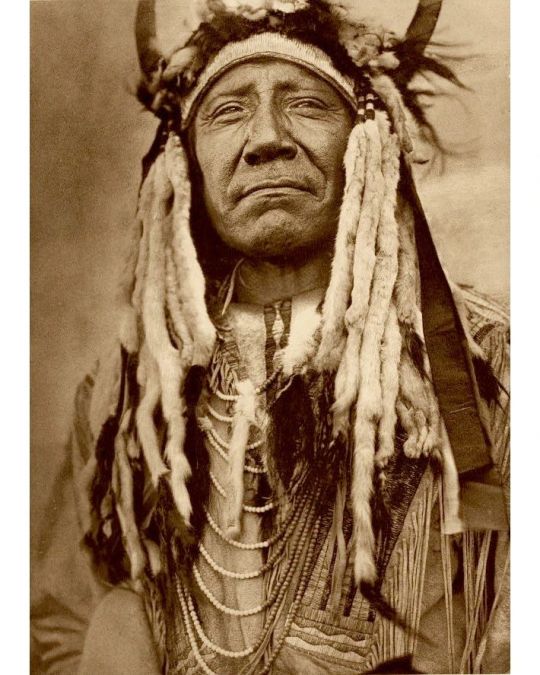

Photo

Morning Star (Dull Knife) - Eastman's Biography

Morning Star (Vooheheve, l. c. 1810-1883, better known as Dull Knife) was a Northern Cheyenne chief who led his people in resistance to the US government's policies of genocidal westward expansion. He participated in Red Cloud's War (1866-1868), various engagements between 1868-1876, and was defeated at the Battle on the Red Fork (the Dull Knife Fight) in 1876.

Afterwards, he and his people were forced from their homelands in the Dakota territories onto the reservation in modern-day Oklahoma. The conditions there were terrible and many died of disease and starvation. In 1878, Morning Star and Chief Little Wolf (also known as Little Coyote, l. c. 1820-1904) led their people out of the reservation in what has come to be known as the Northern Cheyenne Exodus, hoping to reach and reclaim their homelands in the region of modern-day Montana.

Little Wolf's band separated from the group, heading toward the Powder River territory, while Morning Star's band continued on, hoping to reach the Sioux chief Red Cloud (l. 1822-1909) and safety at the Red Cloud Agency (later the Pine Ridge Reservation). They were apprehended in October 1878 by the US Cavalry and brought to Fort Robinson where they were imprisoned and told they would have to return south to the reservation. Morning Star told the authorities:

All we ask is to be allowed to live, and live in peace…We bowed to the will of the Great Father and went south. There we found a Cheyenne cannot live. So we came home. Better it was, we thought, to die fighting than to perish of sickness…You may kill me here, but you cannot make me go back. We will not go. The only way to get us there is to come in here with clubs and knock us on the head and drag us out and take us down there dead. (Brown, 332)

Negotiations between Morning Star and authorities went nowhere, and, in early January 1879, it was decided food, water, and firewood rations would be withheld from the prisoners to force their compliance in returning south. The Cheyenne instead broke out, using weapons they had hidden in blankets and clothing, in an event later known as the Fort Robinson Breakout and Fort Robinson Massacre (9 January 1879). 60 Cheyenne were killed, 70 captured and returned to the fort, while Morning Star and a few others escaped and fled to the Red Cloud Agency where they were protected by Red Cloud.

Morning Star was then able to negotiate terms, which resulted in the establishment of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana in 1884, although he would not live to see that, dying in 1883.

Eastman's Biography & Omissions

The Sioux physician, lecturer, and author Charles A. Eastman (also known as Ohiyesa, l. 1858-1939), includes Morning Star in his Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains (1916) by his Sioux name "Dull Knife" (which he is better known by, largely due to Eastman's work). Almost nothing is known of Morning Star's life prior to his participation in Red Cloud's War, and Eastman's biography reflects that.

The work includes anecdotes of the chief's younger years but focuses on his life after 1875 and, especially, the Northern Cheyenne Exodus and Fort Robinson Massacre. For unknown reasons, considering the usual accuracy of Eastman's biographies, he claims that Morning Star (Dull Knife) was killed at Fort Robinson in 1879 when it is known he lived until 1883, dying of natural causes. No explanation for this is available. The rest of the work is considered accurate, however, especially regarding Cheyenne support for the Great Sioux War (1876-1877) and the Northern Cheyenne Exodus.

Many details are omitted, however, including how Morning Star was among the chiefs present at the signing of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which ended Red Cloud's War and promised the Sioux their ancestral lands in the region of modern-day South Dakota, part of North Dakota, and Nebraska. This treaty was not honored by the US government, leading to further hostilities and, eventually, the Great Sioux War.

Morning Star was not present at the Battle of the Little Bighorn (Battle of the Greasy Grass, 25-26 June 1876) but was inspired by the victory of Sitting Bull (l. c. 1837-1890), Crazy Horse (l. c. 1840-1877), and Sioux war chief Gall (l. c. 1840-1894) to again take up arms against the US military. He and Little Wolf were defeated by troops under the command of Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie (l. 1840-1889) and his Pawnee allies at the Battle on the Red Fork (the Dull Knife Fight) on 25 November 1876.

It was this defeat that led to the Northern Cheyenne being forcibly removed to the Southern Cheyenne Reservation in "Indian Territory" of modern-day Oklahoma in April 1877. The terrible conditions there then resulted in the Northern Cheyenne Exodus of 1878.

Continue reading...

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Telegram from Commander Alfred H. Terry to the Adjutant General of the Division of the Missouri

Record Group 393: Records of U.S. Army Continental CommandsSeries: Special Files of Letters ReceivedFile Unit: Sioux Indian Papers, 1879 - Brief and Letters Received 3721 (with enclosures to 3571) Thru 5219

[pre-printed form]

The Western Union Telegraph Company.

The rules of this company require that all messages received for transmission shall be written on the message blanks of the Company.

under and subject to the conditions printed thereon, which conditions have been agreed to by the sender of the following message.

A.R.Brewer, Secretary. William Orton, Prest.

No. [handwritten] 242 [/handwritten]

[handwritten at top of page] [illegible] / 36/ 29P [/[

[handwritten at right] 123 [ppw?] [/]

Dated [handwritten] At Paul/Minn/23 [/handwritten]

To [handwritten] Adjutant Gent Division [/handwritten]

Rec'd at cor. Lasalle and Washington Sts.,

Chicago, Ills. [handwritten] July 23, 1879 [/handwritten]

[handwritten] Missouri Chicago

On the seventeenth June the advance of [Mibs?] Column

under Lieutenant Clark second cavalry composed of

Lieutenant Bordens Company fifth infantry Lieutenant

Hoppins company second cavalry and fifty Indian scouts

had a sharp engagement between Beaver Creek + Mouth of

frenchmans Creek with four hundred Hostile Indians the

indians were pursued twelve miles when the troops in

advance became surrounded [illegible letters stricken through] Main Command was moved

forward rapidly + the Enemy fled North of Milk river

Colonel Miles reports that the troops engaged fought in

admirable order + are entitled to much credit that the action

of our Indians was quite satisfactory Cheyennes, Sioux,

Crows, Assiniboines and Bannacks fighting with the troops

Killing several Hostile Indians + forcing the enemy to

abandon a large amount of property. Our casualties are

two men Company Second Cavalry wounded two Cheyenne

and one Crow Indian Scouts killed and one Assiniboine

scout seriously wounded. A large scouting party sent

upon North side of Milk river near Head of

Porcupine reports to Colonel Miles that main

camp under Sitting Bull composed of sixteen

hundred lodges is on little rocky having moved over

from Frenchmans Creek Colonel Miles says this

report is corroborated by several others + by men

who were in the Hostile Camp as late as June Sixteenth

+ that he expects to move up between frenchmans Creek +

the Little Rocky where possibly the Main body of

Indians may be engaged

Terry Department Commander

246 paid Govt Rate

# 532

[stamped] RECEIVED

[stamped] JUL

[stamped] [2?] 23

[stamped] 1879

[stamped] MIL.DIV.,MO.

#245

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

6/24/24: Reflections on Visiting Homeland & Indian Policy

This will be a series of short essays about my experiences visiting CRST (Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe). Edited & posted 7/30/24.

Standing beside the graves of my great-grandparents, William Garreau and his wife On the Lead.

I've just returned from a trip to the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe (CRST), sovereign Lakota land surrounded by the state of South Dakota. This experience of going to this place where my ancestors lived was humbling, informative, and intense above all.

While I am an enrolled member of the Cheyenne River Lakota, I was born and raised in Maine; In many ways, this is where my heart is. I connect with the woodlands and the river that has been a constant companion to me through all my years. This, though, is not where my blood family or ancestors are from.

The sky here seems to stretch forever. You don't fully understand the enormity of it until you're under its expanse--But despite what you might hear about "prarie madness" in places where the "sky is too big", I felt comforted in knowing that this is where my family and ancestors lived, and continue to live.

Coming from Maine, tribal lands are handled differently. In traveling to a Native community here, you are very nearly assured that everyone living on reservation land is either Native themselves, or integrated into a Native family one way or another (married, adopted, etc). In off-reservation areas, there is still often recognition of the land's Indigenous roots, whether it be through place names or by signage. This is not to give too much credit to colonizers. The Wabanaki community has been steadfast in maintaining their cultural identity and asserting their presence. This is helped by the fact that these are truly ancestral lands; Wabanaki have lived here since time immemorial, and their archaeological record in the area goes back at least 5,000 years.

Indian policy in Maine also fundamentally differs from that out West. In my paper Triumph and Tribulation: Wabanaki Experiences, 1950-2020, I cover MICSA, perhaps the most significant Maine Indian land policy in recent years:

For the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot, their long battle with the State of Maine for land claims would bear fruit in 1980, with the passing of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act (MICSA).[1] MICSA was initially deemed a success and was the largest land claims settlement at the time, as well as the first to include provisions for land reacquisition.[2] The Act had tribes cede 12.5 million acres, or 60% of Maine, in exchange for $81.5 million divided between tribes.[3] The Houlton Band of Maliseets joined the settlement in 1979 and were provided with $900,000 for the purchase of a five-thousand-acre reservation, as well as federal recognition.[4] The breakdown of the $81.5 million between the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot was $26.8 million for each tribe, or 150,000 acres in unorganized territories—soft money.[5] The remaining $27 million would be split between the two with one million dollars set aside for infrastructure for elders.[6] MISCA also created the Maine Implementing Act (MIA) and the Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission (MITSC), which would define tribal-state relationships by establishing specific laws about Wabanaki peoples and their lands.[7] This served as a means to define and resolve discrepancies with MICSA, as it was largely considered much more legally rigid than the Wabanaki tribes had initially understood it to be.[8] This rigidity would ultimately be a major critique of MICSA and its associated provisions. There were concerns that MISCA did not respect Wabanaki tribes as sovereign nations but, rather, reduced reservation lands to municipality status.[9] State paternalism toward Indigenous peoples of Maine was effectively allowed to continue. Per-capita payments for MISCA were ultimately very little for many, hardly the windfall gain that many perceived it to be; additionally, many saw acceptance of the payments as agreement to the terms of MICSA, with which not all Wabanaki agreed.[10] Though MICSA was perhaps the first step in a road toward true self-determination, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, and Maliseet people continued to struggle. Fears surrounding termination still loomed in the minds of many

...

The 1990s would bring the Aroostook Band of Micmacs (or Mi’kmaq, now considered the correct spelling) into the MICSA agreement. Following the 1980 settlement, and with the MIA considered no longer necessary, the Mi’kmaq had been largely left to fend for themselves.[11] Their fellow Wabanaki found it inappropriate to speak on their behalf.[12] In 1991, Congress would seek to correct this oversight: similar to the Maliseet, Mi’kmaq would receive $900,000 for a five thousand acre reservation, federal recognition, as well as $50,000 in additional property funds in dispersed settlements.[13]

However, like many tribes in the West, my oyate were affected by the disastrous Dawes Severalty Act (also known as General Allotment Act) in 1887. In short, this act would give Indians an allotment of land to farm or ranch (regardless of traditional living and subsistence practices). "Surplus" land not allotted was then sold off cheaply to white farmers and ranchers, creating something of a checkerboard affect in Indian country. I talk more about this in reblog discussing the issues of cottagecore on my main blog back in January.

Because of this, Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe land is still inhabited by a minority of white farmers and ranchers. While we had no incidents while picking timpsula, traveling through fields to Thunder Butte, or otherwise exploring and learning, the discomfort my aunties (residents of CRST) felt when encountering white ranchers was palpable.

Digging timpsula at CRST with my thiwahe (family)

Reservation lands have historically been a place where Indians are cloistered away. My grandfather would recall times when there were curfews for when they had to be back (though he would gleefully recall violating this curfew and riding around with friends and getting up to all sorts of car-related hijinks); an extension of US paternalism towards Indians. In earlier times (though not in such a distant past), Indian agents policed and monitored Indian behavior. Nuns and priests evangelized and enforced the ban on Indigenous religious practice. The cultural devastation created by these systems is still felt today. My great auntie, who lived on the reservation, was very Christian until the day she died. Our language continues to be endangered. Efforts to revitalize and maintain our culture are critical and complicated by generations of racial shaming, residential schools, and forced US paternalism that has caused us to become unwilling dependents.

This is one of the biggest recurring themes in Indian policy in the United States. We are set up to fail, and when we do, the US government can swoop in and claim we can’t take care of ourselves.

I don’t mean to engender a sense of hopelessness within this essay, far from it. There is hope. I want to make those outside of Indigenous communities viscerally aware of our struggles and our existence in the current moment. We are here, we are not peoples of the past, and everything is not okay. There is pain, but how we navigate our cultural wounds is a testament to our resilience as a people.

Within the Lakota Nation, there have been a number of programs to preserve and revitalize the culture. The Lakota Cultural Center in Eagle Butte has recently experienced a massive overhaul under the leadership of Dave West, current program director.

Me and Até outside the Lakota Cultural Center in Eagle Butte after getting my tribal ID

We were lucky enough to catch Dave during his work day at the center, and he graciously gave us an extremely in-depth and powerful tour of the museum. What stood out to me during my conversation with him was a re-orientation of cultural knowledge.

The Lakota Cultural Center has been doing important work in facilitating community nights and days were our oyate can come together and share knowledge on more equal footing. Tables and chairs are set up in a circle, so that, as Dave put it, "A six year old child and seventy year old elder can both be heard." Workshops may range from traditional crafts to singing, story-telling, gathering, and language-sharing.

Elk hide prepared by CRST youth.

Community engagement with traditional practices is not only sacred, but helps heal and offers a healthy outlet for pain we may be feeling.

Something I've taken away from my work this summer, and what I intend with this blog is similar to the cultural center's message-- Knowledge sharing. Knowledge is power as much as it is healing. I believe it is critical to share knowledge not only without our own communities, but outside of them as well; To facilitate a conversation between Indigenous communities and our neighbors (all residents of Turtle Island).

I hope to share more about my trip in follow-up posts. This installment has been focused on Indian land policy and cultural revitalization. If you've made it to the end, I want to thank you for taking the time to read and engage. Please feel free to share your thoughts in comments! Respectful conversation around my posts is very encouraged. Have a wonderful day!

Check out my (free) substack!

Citations & References:

[1] Lecture NAS 222, 4/15/24.

[2] Girouard, 60. (Girouard, Maria L. 2012. “THE ORIGINAL MEANING AND INTENT OF THE MAINE INDIAN LAND CLAIMS: PENOBSCOT PERSPECTIVES.” Graduate School: University of Maine.)

[3] Lecture 4/15/24.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid; Girouard, 60.

[8] Girouard, 60.

[9] Lecture 4/15/24.

[10] 4/19/24.

[11] Brimley, Stephen. 2004. “Native American Sovereignty in Maine” Maine Policy Review 13.2 (2004) : 12 -26.

http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mpr/vol13/iss2/4., 22.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Lecture 4/19/24.

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On this day, 17 March 1876 US troops attacked sleeping Cheyenne and Oglala Lakota people in Montana in the Battle of Powder River, marking the beginning of the Great Sioux War. They destroyed the village and stole large amounts of the Native Americans' possessions. But despite firing nearly 2,000 bullets, US forces only managed to kill one Native American. On the other hand the Cheyenne and Lakota warriors, led by Éše'he Ôhnéšesêstse (Two Moons, pictured) with only around 200 bullets killed four and seriously wounded six soldiers. They also recaptured 500 of their horses the next morning. The US commanding officer, colonel Joseph Reynolds, was court-martialed following the failed assault and suspended from duty. The incident likely galvanised resistance to the enforced relocation of Native Americans from the Black Hills to a reservation. Learn more about Indigenous resistance in the Americas in this book: https://shop.workingclasshistory.com/collections/books/products/500-years-of-indigenous-resistance-gord-hill https://www.facebook.com/workingclasshistory/photos/a.1819457841572691/2232508416934296/?type=3

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Dec 10th, we venerate Elevated Ancestor & Saint Maȟpíya Lúta aka Chief Red Cloud on the 113th anniversary of his passing 🕊 [for our Hoodoos of First Nations descent]

Red Cloud, Chief of the Oglala Sioux, was a political leader, a negotiator of peace, & fierce warrior who fought tirelessly to save his people from colonizer expansion into the midwest.

Maȟpíya Lúta was born near the forks of the Platte River, in what was at the time known as the Nebraska Territory; to his Ogala Lakota mother & Brulé Lakota leader father.

He showed great courage, strength, & leadership in battles against the Oglala's traditional competitors once he came of age; the Pawnees, Crows, Shoshones, & Utes. This ultimately earned him Chiefdom. He also successfully killed the usurper rival to his uncle's political leadership. This divided the Oglala for years to come.

Once European invaders discovered gold in Montana in the 1860s, they began dessimating habitats, sacred lands, & territories to build a road from Fort Laramie in present-day Wyoming to the gold fields. They constructed a series of forts to protect the road from interference, which became known as the Bozeman Trail. In 1865, Chief Red Cloud led the Ogala & their Cheyenne allies into a 2-year war against the colonizers along the Bozeman Trail. They were successful. The soldiers, miners, & others were forced to abandon their operation.

Being the peaceful negotiator that he was, at the end of the war, Chief Red Cloud signed the Second Treaty of Fort Laramie, which bound the U.S. to the promise that it would abandon the Bozeman Trail & return - what is now the western half of South Dakota, along with large parts of Wyoming, & Montana - to Lakota Sioux possession. In return, Red Cloud agreed to end his assault & relocate to a reservation in Nebraska known as the Red Cloud Agency.

In his older age, the great warrior became a diplomat of peace. In 1870s, Chief Red Cloud, along with several other First Nations leaders, traveled to D.C. to meet with U.S. President Grant. He later met with Grant again in 1875, when Grant has the caucasity to offer $25K to the Lakota if they would give up their rights to hunt along the Platte River in the Dakota Territory. Red Cloud, and other leaders, vehemently refused.

While Red Cloud pursued the path of peaceful negotiation & passive tactics, many other Indian leaders (including his own son) wanted to fight for their territory & ways of life. Red Cloud & President Grant sought to avoid war, but it was inevitable. After Sitting Bull's crushing defeat of a U.S. 7th Calvary in June of 1876, Whites began perpetuating aggressively negative campaigns & propaganda against First Nations in the West. Even still, Red Cloud resisted the call to war. He pursued diplomacy. In 1878, he successfully lobbied for the removal of the Indian agent at Pine Ridge Agency due to poor treatment. He returned to D.C. several more times to lobby for his people & defend the rights of all First Nations. This led him to become the most photographed Native of the 19th Century.

Red Cloud continued his work to preserve native lands & to maintain the authority of traditional First Nations leader until he was removed from political power; this may have been influenced by his shifting views in favor colonialism via Christianity & adopted the first name, "John". He later died on the Pine Ridge Agency with his wife; blind & ailing. There he rests in the cemetery so named after him.

"The Whites are the same everywhere. I see them every day. They made us many promises, more than I can remember, but they never kept but one; they promised to take our land, and they took it. " - Chief Red Cloud.

We pour libations & give him💐 today as we celebrate him for his spirit of resistance & immense peace. May we look to him for wise counsel, peaceful resolutions, & as a lesson in the influential power of colonialism.

Offering suggestions: River water, peace pipe, Lakota music, bison meat served with wild potatoes & prairie turnips

‼️Note: offering suggestions are just that & strictly for veneration purposes only. Never attempt to conjure up any spirit or entity without proper divination/Mediumship counsel.‼️

#hoodoo#hoodoos#atr#the hoodoo calendar#ancestor veneration#Elevated Ancestors#Chief Red Cloud#Red cloud#Lakota#First Nations#Plains Indians#Oglala#Oglala Lakota#Lakota Nation

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

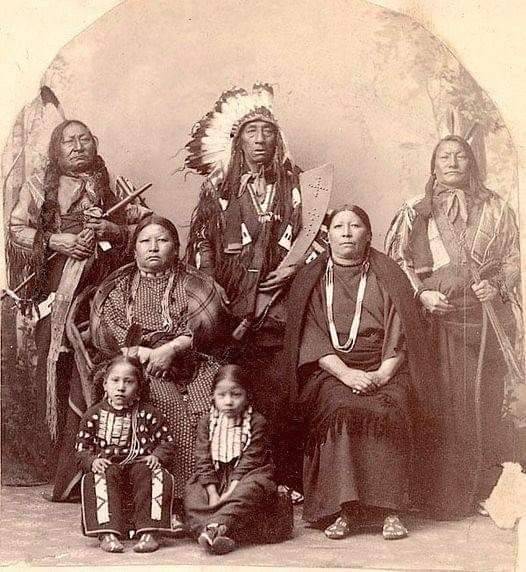

Fool Thunder and family. Hunkpapa Lakota. 1880 ❤

The Hunkpapa (Lakota: Húŋkpapȟa) are a Native American group, one of the seven council fires of the Lakota tribe. The name Húŋkpapȟa is a Lakota word, meaning "Head of the Circle" (at one time, the tribe's name was represented in European-American records as Honkpapa). By tradition, the Húŋkpapȟa set up their lodges at the entryway to the circle of the Great Council when the Sioux met in convocation. They speak Lakȟóta, one of the three dialects of the Sioux language.

Seven hundred and fifty mounted Yankton, Yanktonai and Lakota joined six companies of the Sixth Infantry and 80 fur trappers in an attack on an Arikara Indian village at Grand River (now South Dakota) in August 1823, named the Arikara War. Members of the Lakota, a part of them "Ankpapat", were the first Native Americans to fight in the American Indian Wars alongside US forces west of the Missouri.

They may have formed as a tribe within the Lakota relatively recently, as the first mention of the Hunkpapa in European-American historical records was from a treaty of 1825.

By signing the 1825 treaty, the Hunkpapa and the United States committed themselves to keep up the "friendship which has heretofore existed". With their x-mark, the chiefs also recognized the supremacy of the United States. It is not certain whether they really understood the text in the document. The US representatives gave a medal to Little White Bear, who they understood was the principal Hunkpapa chief; they did not realize how decentralized Native American authority was.

With the Indian Vaccination Act of 1832, the United States assumed responsibility for the inoculation of the Indians against smallpox. Some visiting Hunkpapa may have benefitted from Dr. M. Martin's vaccination of about 900 southern Lakota (no divisions named) at the head of Medicine Creek that autumn. When smallpox struck in 1837, it hit the Hunkpapa as the northernmost Lakota division. The loss, however, may have been fewer than one hundred people.Overall, the Hunkpapa seem to have suffered less from new diseases than many other tribes did.

The boundaries for the Lakota Indian territory were defined in the general peace treaty negotiated near Fort Laramie in the summer of 1851. Leaders of eight different tribes, often at odds with each other and each claiming large territories, signed the treaty. The United States was a ninth party to it. The Crow Indian territory included a tract of land north of the Yellowstone, while the Little Bighorn River ran through the heartland of the Crow country (now Montana). The treaty defines the land of the Arikara, the Hidatsa and the Mandan as a mutual area north of Heart River, partly encircled by the Missouri (now North Dakota).

Soon enough the Hunkpapa and other Sioux attacked the Arikara and the two other so-called village tribes, just as they had done in the past. By 1854, these three smallpox-devastated tribes called for protection from the U.S. Army, and they would repeatedly do so almost to the end of inter-tribal warfare. Eventually the Hunkpapa and other Lakota took control of the three tribes' area north of Heart River, forcing the village people to live in Like a Fishhook Village outside their treaty land. The Lakota were largely in control of the occupied area to 1876–1877.

The United States Army General Warren estimated the population of the Hunkpapa Lakota at about 2920 in 1855. He described their territory as ranging "from the Big Cheyenne up to the Yellowstone, and west to the Black Hills. He states that they formerly intermarried extensively with the Cheyenne." He noted that they raided settlers along the Platte River In addition to dealing with warfare, they suffered considerable losses due to contact with Europeans and contracting of Eurasian infectious diseases to which they had no immunity.

The Hunkpapa gave some of their remote relatives among the Santee Sioux armed support during a large-scale battle near Killdeer Mountain in 1864 with U.S. troops led by General A. Sully.

The Great Sioux Reservation was established with a new treaty in 1868. The Lakota agreed to the construction of "any railroad" outside their reservation. The United States recognized that "the country north of the North Platte River and east of the summits of the Big Horn Mountains" was unsold or unceded Indian territory. These hunting grounds in the south and in the west of the new Lakota domain were used mainly by the Sicangu (Brule-Sioux) and the Oglala, living nearby.

The "free bands" of Hunkpapa favored campsites outside the unsold areas. They took a leading part in the westward enlargement of the range used by the Lakota in the late 1860s and the early 1870s at the expense of other tribes. In search for buffalo, Lakota regularly occupied the eastern part of the Crow Indian Reservation as far west as the Bighorn River, sometimes even raiding the Crow Agency, as they did in 1873. The Lakota pressed the Crow Indians to the point that they reacted like other small tribes: they called for the U.S. Army to intervene and take actions against the intruders.

In the late summer of 1873, the Hunkpapa boldly attacked the Seventh Cavalry in United States territory north of the Yellowstone. Custer's troops escorted a railroad surveying party here, due to similar attacks the year before. Battles such as Honsinger Bluff and Pease Bottom took place on land purchased by the United States from the Crow tribe on May 7, 1868.These continual attacks, and complaints from American Natives, prompted the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to assess the full situation on the northern plains. He said that the unfriendly Lakota roaming the land of other people should "be forced by the military to come in to the Great Sioux Reservation". That was in 1873, notably one year before the discovery of gold in the Black Hills, but the US government did not take action on this concept until three years later.

The Hunkpapa were among the victors in the Battle of Little Bighorn in the Crow Indian Reservation in July 1876.

Since the 1880s, most Hunkpapa have lived in the Standing Rock Indian Reservation (in North and South Dakota). It comprises land along the Grand River which had been used by the Arikara Indians in 1823; the Hunkpapa "won the west" half a century before the whites.

During the 1870s, when the Native Americans of the Great Plains were fighting the United States, the Hunkpapa were led by Sitting Bull in the fighting, together with the Oglala Lakota. They were among the last of the tribes to go to the reservations. By 1891, the majority of Hunkpapa Lakota, about 571 people, resided in the Standing Rock Indian Reservation of North and South Dakota ...

Since then they have not been counted separately from the rest of the Lakota ...

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

CheyenneRiverSiouxTribe #Powwow 2024 #LatePost. #WelcomeHome! Editor Fran Carr driving into #EagleButte #SouthDakota and listening to our friends at #KIPIRadio and coming home for #wacipi! #CRST #CheyenneRiverSioux #CRST #WestRiverEagle #Lakota

#cheyenne river#westrivereagle#eagle butte#wacipi#south dakota#cheyenne river sioux tribe#powwow wacipi

0 notes

Text

"Our Matriarch" - Austin Sunka Luta/Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe

#Lakota #Matriarch

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tribes welcome return of ancestral lands

Tuesday, February 14, 2023

By Kevin Abourezk, Indianz.Com

Kimberly Morales Johnson can’t help but imagine the land that today is Los Angeles as her ancestors would have seen it centuries ago. The Tongva people used the canyons of the San Gabriel Mountains as trading routes with the indigenous people of the Mojave desert. Last year, the Tongva reclaimed land in Los Angeles for the first time in almost 200 years after being forced to give up their lands and having their federal status terminated by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1950.

Sharon Alexander, a non-Native woman, donated a one-acre property in Altadena, California, to the Tongva after learning about the #LandBack movement during the 2016 Democratic National Convention and discovering that the Tongva were the original inhabitants of Los Angeles.

Johnson, vice president of the Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy, a nonprofit set up by the community to receive the land, said the tribe has big plans for the property. “It needs a lot of work, but we’re all dedicated to it,” she said.

In 2022, thousands of acres of private and public land in America were returned to the care of Native peoples. Many of these lands were returned to their original inhabitants, including the one-acre property in Los Angeles.

A website called the Decolonial Atlas created a “Land Back” map charting the locations of land returns that occurred last year. Other land returns that occurred last year include 40 acres around the Wounded Knee National Historic Landmark, the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre. The Oglala Sioux Tribe and the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe bought the land for $500,000.

“It’s a small step towards healing and really making sure that we as a tribe are protecting our critical areas and assets,” Oglala Sioux Tribe President Kevin Killer told The Associated Press.

Although not a land return, the Biden administration last year signed an agreement giving five tribes – the Hopi, Navajo, Ute Mountain Ute, Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation, and Pueblo of Zuni – greater oversight of the 1.3-million acre Bears Ears National Monument in Utah.

Last year, the Rappahannock Tribe celebrated the return of more than 400 acres along the Rappahannock River that is home to a historic tribal village named Pissacoack and a four-mile stretch of white-colored cliffs.

“Your ancestors cherished these lands for many generations and despite centuries of land disputes and shifting policies, your connections to these cliffs and to this river remain unbroken,” Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland said at an event celebrating the land return. One of the largest land returns last year involved the purchase of more than 28,000 acres by the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa Tribe in Minnesota.

The Conservation Fund, an environmental nonprofit, sold the land to the tribe after purchasing the land from a lumber manufacturer in 2020. Emilee Nelson, Minnesota associate state director of The Conservation Fund, said her organization bought the land from the PotlatchDeltic Corporation after the company decided to divest of much of its Minnesota land holdings. The Conservation Fund bought 72,000 acres from the company, including 28,000 acres that were within the Bois Forte Reservation. The Boise Fort Band lost the land following passage of the Dawes Act of 1887, which led to the allotment of the land to private landowners. “Where this land was located made a lot of sense for the tribe to own it,” Nelson said.

However, he said, tribes don’t always want to purchase land or even accept a land donation, especially if they don’t think they’ll be able to put it into federal trust status. He offered advice to those considering donating their land to a tribe. “If you want to make a donation, sell the land and make a donation,” he said.

As for the one-acre land donation to the Tongva, Kimberly Morales Johnson said the tribe plans to use the land to create a community center where it will be able to host cultural workshops and where Tongva people will be able to gather plants sacred to their people, including the acorns from the oak trees on the property.

“This is about self-determination and sovereignty,” she said. The tribe is also allowing a tribal artist to live on the land and take care of it, she said. The Tongva have also begun working to return Native plants to the property and remove invasive species.

“This whole LandBack movement is rooted in healing, and instead of looking at land as a commodity, we’re looking at it as a way to have a relationship with the land and with each other and bringing back our traditions, our language, our food, our culture,” she said.

207 notes

·

View notes