#Clemence Housman

Text

Frontispiece for The Field of Clover by Laurence Housman, illustrated by Clemence Housman (1899)

451 notes

·

View notes

Note

So if you don't mind me asking, whats your stance on Halloween? Is that acceptable?

Gee! This is one of my favorite topics! For a more succinct, well-written response to it, with pictures and Halloween story recommendations, look at this post. Otherwise, I’m just going to ramble 😅

I’m going to answer this as if you’re asking me about the holiday, not the Michael Myers movie series (which I believe are stupid, including the original.)

Anyway, I guess the real question is…”acceptable” for what?

Acceptable as a fun thing to do? Sure. But like…do you ever stop and think about why you enjoy the things you enjoy? What makes them fun, and whether they should be treated as fun?

Not to be that person.

But what I’m saying is, you can make Christmas unacceptable. Anything can be “unacceptable” if you celebrate them the wrong way, for the wrong reasons. If you’re celebrating them flippantly, with no thought behind it.

Christmas, for example, is about celebrating the end of four dark millennia, when, in the coldest, deadest time, the Light came back and promised to stay and fix everything. It’s the end of a long, hard wait. It’s celebrating the gift of that Light. You’re allowed to be extravagant at Christmas, as long as you connect it in your mind and your heart with that idea—“I’m being extravagant to show how wonderful and worthy of specialness this occasion is.”

But check the other side of the coin. You could do Christmas wrong. Then Christmas becomes “unacceptable.” You could make Christmas about the presents; about you; about turning a profit; about making yourself feel better; about escape. You could even make it about “specialness” but you don’t know why it’s special, just that stupid phrase, “that Christmas feeling.”

If you don’t have the “why” behind the celebration, OR your “why” is something you shouldn’t even be celebrating, then the celebration becomes “unacceptable.”

Now.

Some Christians (I assume you’re asking me because I’m a Christian, otherwise most people don’t bat an eye at celebrating Halloween) take one look at a holiday that’s been kidnapped by non-Christians and turned into a celebration of something incorrect—they take one look—and they say, “no children, we don’t celebrate Christmas. We don’t celebrate that holiday. No presents, no tree, no commercialism; it’s about JESUS!” And then they like, metaphorically shut their blinds and hunker down until the world quits celebrating. (Of course, they do the same thing, but much more often, with Halloween.)

That’s basically the same thought process as the monks who, instead of going out and changing the world, instead of correcting wrong thinking by reminding humans of the God that created their correct but corrupted impulses, they hide from the world.

You know what that teaches kids? That brightness and fun and merriment is not something Christians do. Even though everything that is good, including fun, and laughter, and light, and gift-giving, originally was invented by God.

You know what that implies? If it was made by God, it should be tied back to Him at every opportunity. As long as you do it the right way. Why do we just let our godless culture hijack everything that originally belongs to God? Why don’t we get in there, roll up our sleeves, and do it the right way?

Don’t get me started. (If you’re not enjoying this ramble just go up and click the link to the other post, it’s less rambly and answers your question more succinctly 😅)

That’s why I’m talking about Christmas. Christmas was invented by Christians. No, they did not “steal it from the pagans.” (Anyone who thinks that hasn’t seriously reviewed history.)

God invented hope and merriment, which are the main themes of Christmas. Without the context for that hope, or that merriment, celebrating in the darkest time of year made no sense, even in Greek and Roman ages.

So the pagans were getting drunk and giving each other little effigies of human sacrifices and going door-to-door singing while naked for what?!

To make merry, and feel good, for no logical reason in winter. Without God, there’s no reason to do anything in the dead, dark time of year other than huddle up and wait for it to be over. There’s no reason to have the hope that creates “the Christmas feeling.”

But Christians came along and said, “hey. We have a real reason for feeling hopeful and celebrating something in the hardest time of year. Let us show you how to give that urge it’s proper context.” And instead of human-sacrifice-shaped gifts, they gave gifts that reminded them of Christ’s coming; instead of singing door-to-door naked and drunk, they sang sweet carols like the ones the angels sang, Etc.

Took a bone that was painfully trying to move while out-of-joint, and popped it back into its proper socket. It was always supposed to move. It just couldn’t do it right when it was out of the proper place. Put it back where it belongs, and Ta daaa. Christmas.

Think about that. If we didn’t have those ancient Christians who were already celebrating hope and light during the winter for the right reasons, stepping into the culture and redeeming things that were almost-right, almost-fun, but twisted by the wrong reasons—we wouldn’t have the Christmas we have today. No caroling. No lights. No trees. No Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Most importantly, no real, eternal value to make the holiday as sacred and timeless as it is.

So, with Halloween being my favorite holiday, my point is:

Why aren’t we doing that for Halloween?

You can’t argue that “it isn’t like what we did with pagan traditions and Christmas—it’s pure evil, there’s nothing to redeem.” Because Halloween, even as we know it today, has it’s roots in Christianity, too.

Even more broadly than having its roots in Christian “practices,” it has its roots in natural human tendencies. Which point back to God and the story He’s telling, whether they like it or not. The fact that humans wanted to celebrate something in the darkest, coldest time of year to make them hopeful in the winter points to the fact that we were created for light and hope. Animals don’t do that; they hibernate. Humans don’t hibernate; they look for hope, as if there’s some source for it outside themselves.

It’s the same with Halloween. Correct impulses—wrong expression.

At harvest time, humans saw that leaves were dying and there was this fear that they wouldn’t harvest enough—they didn’t prepare enough—they might die like the leaves around them. They might not make it through winter. On comes the imagery of death, and the idea of consequences for your actions coming back to get you—hello, goblins, ghouls, werewolves, even vampires. (I don’t care where it was being celebrated: Ireland, Guatemala, America, who cares, same impulses for the same reasons for humans around the globe.)

No wonder we started thinking up those dark creatures around that time of year. It makes sense.

NOW. Be a Christian. Put that feeling in it’s proper, truthful context—stop letting the culture define what you should do with those feelings.

Are there darkness and horrible things in the world? Yes. Sin. The consequences of sin. Can those monsters be killed? Yes. They’re scary and stronger than you, but they’re not all-powerful. What can the monsters be killed by? Christ’s sacrifice.

(Now I’m repeating what’s in the post I linked to, but I don’t care, this is one of my favorite topics, I’ll repeat myself:)

Monsters are always killed by the sacrifice of something pure, in the old stories. That’s why:

Vampires can’t see their reflection, because old mirrors had pure silver in them. The pure blood of Ellen in Nosferatu kills the vampire because she willingly sacrifices it to him.

Werewolves are slain by pure silver, or, in old stories, the blood of an innocent person, slain for others.

Frankenstein’s monster finally gives up being a creature of hate and goes to his death when he sees that his Creator was willing to sacrifice his life to right the wrong of his creation.

That’s like, handed to us on a silver platter. And you know what’s even better?

Usually the monsters were once human. We are the monsters.

Which is biblical. We’re enemies of God, incapable of good, incapable of purity, without Him. Until His pure sacrifice literally kills the monstrous part of us.

So yeah, dress up like a monster. Not just because it’s fun, but because it ends. You get to take the costume off. The scariness goes away. You’re not a monster anymore.

As long as you make that the point? Do it. I mean, jeez, the Bible uses “walking dead” imagery to refer to Christians. Monsters and monster fiction could go back to being a tool to point to truth. Halloween could be a holiday that reminds us of what we once were, and the darkness we’re saved from.

I really like Halloween. I got connected with the studio I work for by showing them a pitchbook of a Halloween-monster-themed story concept. I also love the Lord. If you can’t find a way to genuinely link the things you enjoy back to God, and the story He’s telling, take a good hard look at what you enjoy and course-correct. That goes for Halloween, or anything in life.

#bigfrozensix#Credit for the gif#Halloween#all hallow’s Eve#all saints day#Irish history#halloween#October#halloween franchise#Frankenstein#Dracula#Nosferatu#the werewolf#Clemence Housman#werewolf#werewolves#classic horror#gothic horror#monsters of the id#monsters#Christianity#controversy#discourse#asked#answered#thanks

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Life of Sir Aglovale de Galis by Clemence Housman

#Arthurian legend#Arthuriana#sir aglovale#aglovale#the life of sir aglovale de galis#clemence housman#quotes#look my theory continues to prove true & that is:#we all just have our special guy & then we obsess about him & make him the center of our world#aglovale pov!!!!! love it#he is talking about how his mother loves lamorak more btw…..sob#Arthuriana daily#my post

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Werewolf White Fell in Her Wolf Skin, from The Were-Wolf by Clemence Housman, illustrated by Laurence Housman.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Were-Wolf (1896) - Laurence Housman

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

[book review] "the were-wolf" by clemence housman (1896)

this short story is styled as something rather like a fairytale, with a timeless and placeless quality to it. the titular werewolf (or were-wolf i guess) is a seductress who effortlessly bends people to her will while also being an absolutely terrifying combatant in both her human and wolf forms. this mirrors the way the story has room for both genuinely erotic tension and some downright gnarly violence.

i think the werewolf genre does just fine without one super obvious ur-text to hold up… but if you had to pick something to enjoy that honor, i think this would be a better fit than guy endore’s more widely-cited the werewolf of paris.

b-rank

#reviews#book review#books#short story#werewolf#werewolves#the were-wolf#clemence housman#werewolf books

1 note

·

View note

Text

Typography Tuesday

Last week we presented a 1900 edition of The Confessions of St. Augustine with illustrations by Paul Woodroffe (1875-1954) and a title-page border designed by Laurence Housman (1865-1959), all engraved in wood by Houseman's sister Clemence Houseman (1861-1955). Another visual element in the book is the use of elaborate, wood-engraved, Arts and Crafts-style initials found throughout the book. Today we are showcasing all the initial letters used in the publication.

Their design is uncredited, but it is possible that they could have been designed by Woodroffe as he was deeply influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement. Two years after illustrating this book, Woodroffe was elected a member of the Art Workers' Guild, an organization of artist and designers associated with the ideas of William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement, and in the same year he became closely associated with Charles Robert Ashbee and his Guild of Handicraft and Essex House Press, institutions closely allied with the movement. Again, it's conjecture, but we would like to think that Clemence Houseman had a hand in engraving these initials.

View more posts with wood engravings by Clemence Houseman.

View other posts with illustrations by Paul Woodroffe.

View a few other posts with books in the Arts & Crafts style.

View more Typography Tuesday posts.

#Typography Tuesday#typetuesday#initials#wood engraved initials#Arts and Crafts movement#Paul Woodroffe#Clemence Houseman#The Confessions of St. Augustine#fancy initials

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

"She was a maiden, tall and very fair. The fashion of her dress was strange, half masculine, yet not un-womanly. A fine fur tunic, reaching but little below the knee, was all the skirt she wore; below were the cross-bound shoes and leggings that a hunter wears.

A white fur cap was set low upon the brows, and from its edge strips of fur fell lappet-wise about her shoulders; two of these at her entrance had been drawn forward and crossed about her throat, but now, loosened and thrust back, left unhidden long plaits of fair hair that lay forward on shoulder and breast, down to the ivory-studded girdle where the axe gleamed."

from The Werewolf by Clemence Housman, 1896

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Overview and Criteria for Gothic Fiction

Gothic as a genre of fiction novel emerged in the late 18th century and early 19th century. Modern scholars frame these works as part of a Romanticist pushback against the Enlightenment era of calculated, scientific rationalism. In English literature, these may also have been artistic expressions of the collective anxieties of British people regarding the French Revolution. The term hearkens back to the destruction of the Roman Empire in the 5th century CE at the effect of Gothic peoples, an event that marks the beginning of the medieval era. As early as the year 1530 CE, Giorgio Vasari criticized medieval architecture as gothic, that is "monstrous", "barbarous", and "disordered" contrasted against the elegant and progressive neoclassical architecture reconstructions. In the late 20th century, a subculture of post-punk horror rockers began to be described as Gothic as well. This subcultural goth variation characterized itself by an aesthetic of counter-cultural macabre and "enjoyable fear".

Notable early works of what would become the gothic literary "canon" are listed as follows: The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole (1764), The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne by Ann Radcliffe (1789), The Castle of Wolfenbach by Eliza Parsons (1793), and The Mysteries of Udolpho by Ann Radcliffe (1794). Udolpho is the name of a castle. Early gothic literature was intertwined with an admiration for gothic architecture, sorry to Vasari Giorgio who hated that sort of thing so much but is an outlier and should not be counted.

One example of French gothic literature in this vein is Notre-Dame de Paris by Victor Hugo, published in 1831 although the story is set in 1482 and it was about a gothic cathedral rather than a gothic castle. Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen is an affectionate parody of the gothic literature genre and a staunch defense of the gothic novels' artistic merits. It was completed in 1803 but not published until 1818 after the author's death.

In Northanger Abbey, a character recommends to her friend a list of books in this genre, all the titles of which were publications contemporary to the time the author was writing about them: The Italian by Ann Radcliffe, Clermont by Regina Maria Roche, The Mysterious Warning by Eliza Parsons, Necromancer of the Black Forest by Lawrence Flammenberg, The Midnight Bell by Francis Lathorn, Orphan of the Rhine by Eleanor Sleath, and Horrid Mysteries by Carl Grosse.

The appeal of these stories was less the architecture itself and more the emotions evoked by being haunted by the past, threatened by unknown histories, frightened by misunderstood monsters, and in awe of wilderness and nature. All of this would be set at or relative to a location: a gothic building. Heroines in gothic stories would commonly be abducted from convents that they sought refuge in, or confined to convents or other locations against their will when they try to exercise their freedoms. Other common tropes became the journey of a gothic heroine in an unfamiliar country, and the horrors of being made to rely on guardians who make impositions against her wishes or best interests. In other cases, the gothic horror mixed with gothic infatuation would be shown by an invasion of sorts by a foreigner in the heroine's home country, person of color, or the occupation of a disabled person. These works frequently lend themselves to queer readings.

The common and notable qualities of what works came to be considered gothic literature between the 1819 publication of The Vampyre by John William Polidori and the 1896 publication of The Werewolf by Clemence Housman, naturally expanded and evolved with the inclusion of more works within this genre. Even now in the 21st century the continued recognizability of the gothic applies to new additions to the genre. The criteria for what qualifies a gothic story follows:

Ill-Reputed Work. The story is accused of being degrading to high culture, bad for society, immoral, populist or counter-cultural. At the very least, it's considered bad art and ugly.

Haunted by the Past. This can be found in a work framed accordingly in the cultural context that inspired the authors, such as early 19th century English literature of this genre as a response to the French Revolution. Works emblematic of the Southern Gothic in the United States could be framed in the context of the anxieties surrounding the Civil War. More often, however, it is personal history that haunts a gothic character.

Architecture. This is not necessarily mere mention of a building, or even a lush description of literally gothic architecture. This is more a sense of location. While it stands to reason that confined locations are buildings, the narrative function of architecture can be served by themes of isolation and confinement. Social consensus that is impossible to navigate or escape is a gothic sentiment. This is, of course, more clearly qualified if the architecture is literally a building.

Wilderness. This is not necessarily natural environments, but rather situations that are unpredictable and overwhelming. Storms can be similarly admired, those "dark and stormy night"s. The anxiety invoked by nautical horror emerges from the contrast between a human being made to feel small and out of control when situated on the open ocean and all its depths and mysteries. The gothic simplicity of fairy tales relies on the inhospitable and chaotic woods full of bandits, wolves, and maybe even witches. Logically, a city should be more architecture than wilderness, but if the narrative purpose is chaotic unpredictable vastness horror rather than confinement horror then the city can become a gothic wilderness. This is, of course, more clearly qualified if the wilderness is literally the weather.

Big Mood Energy. This is what I call a collection of emotions evoked by the design of gothic literature. The sense of vulnerability in the face of grandeur, or overwhelming emotion, is known as Sublime. The betrayal of that which is supposed to be familiar is known as the Uncanny. A disruption or disrespect of identity, order, or security is known as the Abject. Gothic literature often evokes disgust and discomfort with ambiguity, or showcases melodramatic sentimentality, or includes heavyhanded symbolism. Gothic literature explores boundaries and deconstructs the rules that keep readers comfortable.

Optionally, Supernatural. As a response to Enlightenment-era science and rationalism, the supernatural found new importance in gothic literature, symbolically and in the evocative emotions it wrought.

The growing edge of genre gothic I think can be found in genre overlap with picaresque stories, detective mysteries, works of libertine sensationalism, science fiction, fairy tales, and dark academia. Quaint tropes are subverted or transformed, and new ones can emerge in the symbolic conversation that works of fiction can strike up with one another. I hope the above criteria remains a useful guide.

Sources:

Peake, Jak. “Representing the Gothic.” 30 April 2013, University of Essex. Lecture. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B51o-1KTJhw

Nixon, Lauren. “Exploring the Gothic in Contemporary Culture and Criticism.” 4 August 2017, University of Sheffield. Lecture. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JZP4g0eZmo8

"Why Are Goths? History of the Gothic 18th Century to Now". Wright, Carrie. 17 December 2022. www.youtube.com/watch?v=TrIK6pBj4f8

"8 Aspects of Gothic Books". Teed, Tristan. 19 June 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NULLOYGiSDI

Burke, Edmund. A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. London, Vernor & Hood, etc., 1798. Originally published in 1756.

Freud, Sigmund. The Uncanny, Penguin Books, New York, 2003. Originally published in 1919.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, translated by Leon Roudiez, Columbia University Press, New York, NY, 2010. Originally published in 1984.

Commentary and reading list under Read More.

Commentary

I owe to Tristan Teed the idea of framing emergent gothic literature as countercultural to Enlightenment rationalism and science, and this pushback symbolized by wilderness; Dr. Jak Peake for contextualizing gothic literature as an artistic response to civic unrest in general, and highlighting the fear of seductive immigrants in Bram Stroker's Dracula more specifically; Carrie Wright for the feminist readings of the literary references in Jane Austen's Northanger Abbey, and Dr. Lauren Nixon framing the term gothic as originally meaning bad art—the lattermost aspect I personally consider integral to the genre as it must remain a constant interrogation of what artistic expression we as a society consider "bad art" and why. Both Wright and Teed inspired the aspects list applied to an otherwise categorization-defiant genre that gothic literature is. Critical Race Theory readings and Queer Theory readings of works considered part of gothic literature canon, I would say are informed by the works themselves being very suggestive of these readings. Sheridan Le Fanu's 1872 Carmilla influenced Rachel Klein's 2002 The Moth Diaries that blurred the lines between the homosocial and the homoerotic at a girl's boarding school. Florian Tacorian (not listed in these citations, but go watch his videos) highlighted Romani presence in adaptations of Victor Hugo's Notre-Dame de Paris, as well as Emily Brontë's 1847 novel Wuthering Heights. The work of another Brontë sister, Charlotte Brontë, is more often mentioned as though closer to the core canon gothic literature, and the eponymous Jane Eyre contends with a Creole woman confined to the attic of her new home (this was written in 1847, the race issue was made explicit in Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys published in 1966 that was a retelling of Jane Eyre.)

Notes on the works of gothic literature mentioned: As of this writing, I have read Northanger Abbey, The Vampyre, Carmilla, Dracula, and only half of Notre-Dame de Paris. I have only watched a movie adaptation of The Moth Diaries. (Update as of the 8th of October 2023: I finished reading The Moth Diaries by Rachel Klein. This whole essay was posted on the 1st of October 2023.) (Update as of December 2023: I finished reading Jane Eyre.) Despite taking the internet handle Poe, American gothic literature is pretty much completely alien to me. I might have read a handful of other works that might be arguably gothic, but have not mentioned them here so I would not count them in a list of works that are mentioned in this essay and that I have personally read. The initial list was a semi-facetious argument for the presence of gothic architecture in gothic literature based on the titles alone. Note also my focus on gothic literature from the British Isles, with a mention of only two titles from Germany (Der Genius by Carl Grosse, translated into the English The Horrid Mysteries by Peter Will; and Der Geisterbanner: Eine Wundergeschichte aus mündlichen und schriftlichen Traditionen by Karl Friedrich Kahlert under the pen name Lawrence Flammenberg, translated into the English Necromancer of the Black Forest by Peter Teuthold that was first published in 1794) and only one from France (Notre-Dame de Paris 1482 by Victor Hugo). This is not to say that there was little to no Romanticist movement in Germany or France in the 18th and 19th centuries compared to Britain. Friedrich Maximilian Klinger's stageplay Sturm und Drang premiered in 1777 and lent its name to a proto-Romantic artistic era that was supremely Sublime and Big Mood Energy. The earliest French gothic novel I could find via a cursory search engine search was Jacques Cazotte's Le Diable Amoureux, 1772, and I deliberately selected Notre-Dame de Paris for mention instead to demonstrate the continued theme of architecture and variety in architecture: churches as well as castles, and to affirm the representation of disability in gothic literature because Quasimodo (a character in the book) is deaf and according to John Green had contacted spinal tuburculosis that left the character hunchbacked. I have not read any of Le Diable Amoureux, let alone the half that gave me the temerity to list Notre-Dame de Paris among these gothic works.

This sparseness is due to my own interest in the emergence of English-language gothic literature focused on Britain between the years 1789 and 1830, in keeping with Ian Mortimer's definition of the Regency era in Britain. That, and the information from the sources I have cited, are what I based the criteria that I offer for what makes a novel genre-compliant to gothic. The narrative psychology and historicist analyses of The Castle of Otranto as an outlier published earlier than the timeframe I confine myself to, is for another essay perhaps written by somebody else. Similarly, my argument for the lineage of picaresque heroes from Paul Clifford to The Scarlet Pimpernel, Don Diego "Zorro" de la Vega, and ultimately the angst-filled cinematic version of Bruce Wayne as overlapping the picaresque with the gothic is a blog post for another time. I have read some works by the Maquis Donatien Alphonse François de Sade and I utterly and unutterably abhor all of it, will the spectre of his abysmal depravity ever cease to haunt me—but I think I can make an argument for his works being gothic even as he argued for himself that they were not; I have no plans of doing so.

My main intention in writing this overview and criteria is to lay the groundwork for examining the overlap between Gothic as a genre and Dark Academia as a genre, which I aim to evaluate in future essays by using this criteria.

List of Works Mentioned Above

The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole (1764)

Le Diable Amoureux by Jacques Cazotte (1772)

The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne by Ann Radcliffe (1789)

The Castle of Wolfenbach by Eliza Parsons (1793)

The Mysteries of Udolpho by Ann Radcliffe (1794)

Necromancer of the Black Forest by Lawrence Flammenberg (translated by Peter Teuthold, 1794)

The Horrid Mysteries by Carl Grosse (translated by Peter Will, 1796)

The Italian by Ann Radcliffe (1796)

The Mysterious Warning by Eliza Parsons (1796)

Clermont by Regina Maria Roche (1798)

The Midnight Bell by Francis Lathorn (1798)

Orphan of the Rhine by Eleanor Sleath (1798)

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen (1818)

The Vampyre by John William Polidori (1819)

Paul Clifford by Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1830)

Notre-Dame de Paris 1482 by Victor Hugo (1831)

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë (1847)

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (1847)

Carmilla by Sheridan Le Fanu (1872)

Dracula by Bram Stroker (1897)

The Werewolf by Clemence Housman (1896)

The Scarlet Pimpernel by Emma Orczy (1905)

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys (1966)

The Moth Diaries by Rachel Klein (2002)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earlier in the month I made a post expressing my interest in making a South Park Monster High AU, as they're the top two media I'm the most invested in at the moment. I've since expanded on that through different characters and what monsters I'd like them to be, so all of that is below ⇩.

I didn't want to force myself to make a decision on some, so some more prevalent characters don't have a monster type yet!

Kyle: Vampire

I wanted to make Kyle a vampire, as I have a fondness of vampires and a strong favoritism toward Kyle... so he gets my favorite monster! As you'll find out throughout my headcanons here, I love it when there are contrasting themes and subverted expectations, so another reason I like Kyle as a vampire is because, much like Draculaura, he wouldn't like blood! He wouldn't be a vegetarian like her, but I just feel that he would have an aversion to blood, given his aversion to germs throughout the series (primarily shown in "Pee" and "Turd Burglars"). I think it would be true to canon to have him dislike blood and find it gross to consume. It would also shake things up a bit with the vampire trope and find some resemble to Draculaura, the most prominent vampire character in Monster High!

If Kyle is a vampire, it would mean one or two of his parents would have to be as well... Both! I really like the idea of a vampire Sheila and Gerald. If you're not familiar with Monster High lore, it's sort of built into canon that vampires are more respected monsters and ... upper class citizens, in a way? I thought this would be a nice parallel to "Chicken Pox" with what Gerald was telling Kyle about gods and clods (more on this later).

Ike: Sea Serpent

Ike isn't a vampire like the rest of his family, as he's adopted. I did consider making him human, but I grew very attached to the idea of him as a sea creature. While vampires tend to emulate humans more in appearance, I wanted Ike to look more monstrous - I want it to show in his features. I imagine him to be a different color, perhaps a greenish blue, with gils on his face, horns, webbed hands and feet, and a long tail. His difference in appearance from his family would represent his Canadian heritage. It's a common joke in South Park that Canadians look different from everyone else, so I want this to show with Ike's more monstrous appearance compared to his family.

Ike has also shown a love for pirates at points in the series, and sea serpents are always closely related to pirates. Of course, most often, they're seen as the enemy of pirates, but I feel as if in a monster world, sea serpents would be the pirates... so it would be very cool to see Ike as a sea serpent with that in mind!

Stan: Werewolf

The majority of this is based on vibes. Stan is just... a dog person, so why not make him a dog-person? I also like the idea of the two main characters being the most culturally prominent monsters (I blame 2000s YA novels for that). He's very dogish in personality, and tends to be a follower rather than a leader, which emulates a canine's desire to please.

With Stan comes his parents and his sister... I see them as werewolves, too. I especially like the idea of Shelley as a werewolf, as I think it fits her well. Again, bringing the subversion of expectations back, some braces come in silver... and... werewolves do not like silver. I think it would be funny to give a werewolf Shelley silver braces. Maybe that's why she's so easy to anger...? Werewolves are also physically strong, which Shelley definitely is. Last semester, I also took a class on paranormal stories from the Victorian era and found out about the existence of a novel: "The Were-Wolf" written by Clemence Housman. It's a story published in 1896 and, as the title suggests, features a werewolf... but the werewolf was a woman! Themes of woman's suffrage and Victorian-age feminism were incorporated into the book, as well as the female werewolf. Werewolves are definitely what people would consider more masculine, so it was really interesting to see a novel subverting these expectations (!) so long ago. That being said, this is kind of why I have more of an explanation for werewolf Shelley than Stan. It could also apply to Sharon as well. I just love the idea of a traditionally male or female monster being portrayed by the opposite or in-between (which I'll also discuss later).

Kenny: Zombie

How could Kenny be anything but a Zombie? It fits far too well. Zombies are dead and are able to rise again after 'death', and that strongly emulates what Kenny is. The first Halloween episode of the show also featured Kenny as a zombie!

In Monster High, zombies don't really speak the same language as the others. They communicate in groans and moans. The audience can't understand them, but the other characters are able to understand and communicate easily with them. That just sounds so much like Kenny! He has his muffled speech that the audience (generally) can't understand, but other characters are able to understand and communicate with easily!

Going back to what I said about "Chicken Pox" in Kyle's section, in the Monster High universe (primarily expressed in the webisodes), zombies aren't seen as higher class citizens as some of the other monsters. In fact, they're often looked down upon and not taken as seriously because they're zombies. I found this to be a nice parallel to what Gerald was saying in that episode, as he expressed that he felt he was more important because of who he was (having a "slightly higher intellect than others") compared to Stuart. With vampires being higher class in the MH universe and zombies traditionally being lower... the comparison was too good not to make.

Craig: Ccoa

I wanted to find something unique for Craig... not just something related to guinea pigs. So, much like the others, I sought after canon. Ccoas are catlike creatures hailing from Quechuan (indigenous people of Peru) folklore. They're more so spirits than anything, and are closely related with constellations and the stars. I would recommend clicking the link for more information!

In Monster High, there are numerous characters represented with monsters from their culture, so, as Craig canonically has something to do with Peru... I really wanted to give him a Peruvian creature, and what better than a cat involved in the stars? He gives me more catlike vibes - his whole family does! - and he loves space, so this really was a good match.

I like the headcanon that Laura is Peruvian, so I think what I would do is make Laura and Craig Ccoas, but make Thomas and Tricia regular cat-people. The thought of Thomas as a catboy is really funny to me because he's kind of goofy looking! I think I would want him to be an orange Scottish Fold. He has that big bald spot, and Scottish Folds are known for having their ears down, so I thought it fit well! Laura, a ccoa, married a werecat (in Monster High terms... but still a catboy, techincally), Thomas, and they had two children: Craig (a ccoa like his mother) and Tricia (a werecat like her father).

Tweek: Ghost

I love this one. I love the thought of Tweek as a ghost. Once again with the subversion of expectations, the thought of a ghost that's easily startled is appealing to me. I think it makes for a more interesting character... kind of like an inner conflict to pass! The other reason I have for this is his hair... Tweek's hair would translate visually well into wisps. It would be an easy design to create.

Clyde: Banshee

A banshee is a spirit originating from Irish folklore. They're traditionally women, however, I feel as if the description fits Clyde - as well as his family - well. First and foremost, I'd like to compare this illustration of a banshee to Betsy after her death. They're very similar, so this way, Betsy wouldn't have to 'die' at all - she's a banshee! Interestingly enough, one of the primary connections of banshees are dead family members... They're known to scream, wail, or shriek in lamenting the dead. They tend to be emotional creatures, which, again, I feel captures Clyde well. He's much more rooted in emotion than anything else - it's a prime characteristic of his, after all.

Bebe: Centaur

I have the design in my head, and I love it. I imagine Bebe to be a horse girl, and I headcanon her as such, so the idea of her being a centaur is appealing to me. When I think of centaurs, I often imagine long, luscious hair and a tail. Bebe has very recognizable hair - I would say it's her strongest physical trait, so it makes sense for her to be a creature with such emphasis put on the hair/mane.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queer Fiction, day 3/30

I want to talk about some books that aren't romance novels. Let's look at

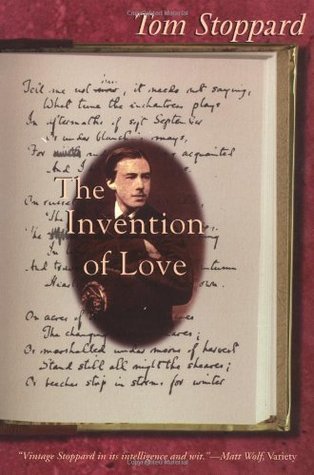

Tom Stoppard is a genius and this play is hilarious. Also, I'm going to say right off the bat that either you're the type of person who likes wordy intellectual plays full of meta-comedy or you're not. Some people prefer gritty realist drama, or in-yer-face plays, or experimental plays like Suzan-Lori Parks does, and that's fine. Some people like Sarah Ruhl, and we just ask them politely but firmly to leave. (Sorry, that's my controversial opinion for the day.)

The Invention of Love is about a late Victorian poet (A.E. Housman, 1859–1936) who fell in love with one of his roommates at university, confessed, was rejected, and spent the rest of his life alone. (Although other research suggests he wasn't the celibate type of alone. Just not in a relationship.)

A lot of it is about language, translation, knowledge, and ways of knowing, and it made me super obsessed with one of Horace's odes (book IV, poem 1). I am learning Latin now and it is Stoppard's fault. It's actually a super fascinating question, how do you look at a corrupted manuscript and figure out what it actually means? Is that even possible after 1,500 years?

(In a few spots in Dionysus in Wisconsin, both Sam and Ulysses grumble about scribal errors and trying to decipher manuscripts, and they're only really working with things from the late Middle Ages. Like. Guys, come on.)

Key Quote:

Ruskin: When I am at Paddington [train station] I feel like I am in hell.

Jowett: You must not go about telling everyone, Dr Ruskin. It will not do for the moral education of Oxford undergraduates that the wages of sin may be no more than the sense of being stranded at one of the larger railway stations.

Ruskin: To be morally educated is to realize that such would be a terrible price. Mechanical advance is the slack taken up of our failing humanity. Hell is very likely to be modernization infinitely extended. [...]

[Later]

Pollard: Ruskin said, when he's at Paddington he feels he is in hell--and this man Oscar Wilde says, "Ah, but--"

Housman: "--When he's in hell he'll think he's only at Paddington."

At various stages of the play, an aged Housman observes and comments on himself and his contemporaries at different times in their lives. They also have a discussion with Charon at one point. It's just tremendous fun.

In real life, Housman's younger brother Lawrence was also gay and founded a secret society for gay men called the Order of Chaeronea. He was also a suffragist (cofounded the Men's League for Women's Suffrage), and a humanist. (I think he founded a few other societies and leagues too.) Housman's younger sister Clemence wrote novels, including one about a female werewolf that is noted on Wikipedia as being an "allegoric, erotic fantasy." I hear that kind of thing is big right now. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL13492113M/The_were-wolf

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great short story, especially in winter

1 note

·

View note

Text

Books I Cycle Through Every Year

The Chronicles of Narnia

Little Women

The Anne of Green Gables Series

Frankenstein

The Were-Wolf

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

The Lord of the Rings & The Hobbit

A Christmas Carol

#One of the first three is always on my person#the last five I re-read only after September starts#middle of Frankenstein now#Mary Shelley#C.S. Lewis#Escapism#J. R. R. Tolkien#Tolkien#l. m. montgomery#Louisa may Alcott#bisclavret#the were-wolf#Clemence Housman#dr. jekyll and mr. hyde#arobert Louis Stevenson#Arthur Conan Doyle

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Life of Sir Aglovale de Galis by Clemence Housman | More quotes at Arthuriana Daily

#arthuriana daily#arthuriana#arthurian mythology#arthurian literature#arthurian legend#sir aglovale#sir percival#sir perceval#the life of sir aglovale de galis#clemence housman#quotes#my post

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was researching something about the use of doubles in fiction and found out The Were-Wolf by Clemence Housman alongside analysis on the text on some weird site. Very interesting so far.

#bla bla#it's one of my favorite media themes mostly because of how highly explorable it can be#but also the perfect excuse for straight people to dismiss queer readings it seems

0 notes

Text

i can't believe i've picked up 19 king arthur related books in a row (and only dnf'd 4 of them!!) and read whole sections of the Vulgate cycle since late nov and i'm not sick of the topic yet. amazing.

i am nearing the end of my reading challenge though so i have these 4 to go:

The Life of Sir Aglovale de Galis by Clemence Housman (1905)

Blackheart Knights by Laure Eve (2021)

Le crépuscule des elfes by Jean-Louis Fetjaine (1999) (he has a bunch more in his arthurian world but i only need one)

The Doom of Camelot anthology ed. James Lowder (2000)

but lots more that i haven't been able to get around to in time

0 notes