#Coronation stone

Text

On August 9th or 9th 1296 the Scottish Coronation Stone was removed from Scone Abbey.

The Stone of Destiny was taken on the orders of King Edward I of England, and was transported to Westminster Abbey, where it was used to crown English monarchs until it was returned to Scotland in 1996.

The Celtic name of the stone upon which the true kings of Scotland have traditionally been crowned is Lia Fail, “the speaking stone,” or the stone which would proclaim the chosen king.

Originally, the stone played a part in the crowning ceremonies of the Scots kings of Dalriada, in the west of Scotland, an area just north of Glasgow now called Argyll.

Kenneth I, the 36th king of Dalriada, united the Scots and Picts kingdoms and moved his capital to Scone from western Scotland around 840 AD. The Stone of Destiny moved there too. All future Scottish kings would henceforth be enthroned on the Stone of Destiny atop Moot Hill at Scone Palace in Perthshire.

The stone in question is no ornately carved megalith; just a simple, oblong block of red sandstone. It measures 650 mm in length by 400 mm wide, and 27 mm deep, with chisel marks apparent on its flat top.

So where did this magical or mythical stone originate from, and why was it held in such reverence by the kings of old?

One legend dates back to biblical times and states that it is the same stone which Jacob used as a pillow at Bethel. Later, according to Jewish legend, it became the pedestal of the ark in the temple. The stone was brought from Syria to Egypt by King Gathelus. He then fled to Spain following the defeat of the Egyptian army. A descendant of Gathelus brought the stone to Ireland, and was crowned on it as King of Ireland. And from Ireland, the stone moved with the invading Scots to Argyll.

What is sure, however, is that the Stone of Destiny remained at Scone until it was forcibly removed by English King Edward I (“Hammer of the Scots”) after his Scottish victories in 1296, and taken to Westminster Abbey in London.

Still another interesting legend surrounds this mystical stone. This one suggests that as King Edward I approached the Abbot of Perth, the monks of Scone hurriedly removed the Stone of Destiny and hid it. He replaced it with a drainage cover stone of similar size and hid the real stone on Dunsinnan Hill. It was the drainage cover which the English king carried off in triumph back to London.

Perhaps this legend is not so far-fetched. It could help to explain why the coronation stone is so geologically similar to the sandstone commonly found around Scone.

On St. Andrew’s Day, on November 30th, 1996, ten thousand people lined Edinburgh’s Royal Mile to witness the return of the Stone of Destiny to Scotland. It had been away for 700 years.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coronation Stone of Moctezuma II (Stone of the Five Suns). Aztec, 1503

#coronation stone#stone of the five suns#moctezuma ii#Aztec#1500s#archeology#Mexico#History#art#folk art

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Coronation Chair: Anatomy of a Medieval throne

The Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II prompted the first comprehensive archaeological study of the Medieval throne on which British monarchs are crowned.

It has been battered and vandalised over the ages, but unpicking this majestic artefact’s evolution shed new light on both its original form and that of the enigmatic Stone of Scone, as Warwick Rodwell reveals.

10 August 2013

The Coronation Chair has been illustrated and described since the 14th century, and is renowned the world over.

For hundreds of years, this piece of Medieval furniture has played a seminal role in the anointing and crowning of English monarchs.

It was last used at the coronation of HM The Queen on 2 June 1953, the Diamond Jubilee of which was celebrated this year.

To mark the occasion in 2010-2012, the Chair underwent a long-overdue programme of cleaning, conservation and redisplay in Westminster Abbey.

Concurrently, a detailed archaeological study was carried out and the Chair was comprehensively recorded for the first time.

The project led to a radically new understanding of its construction and decoration, and of its relationship to the Stone of Scone, which was embodied in its seat.

Spoils of war

The origins of the Chair are well known. Indeed, the documentation accompanying its manufacture in the 1290s is still preserved.

Following Edward I’s victory over the Scots in 1296, state documents and items of regalia were surrendered and taken to London as spoils of war.

One of those items was a ceremonial block of sandstone upon which Scottish kings had hitherto been inaugurated at Scone Abbey in Perthshire, the last being John Balliol in 1292.

The Coronation Chair and Stone of Scone.

Constructed in the 1290s on the orders of Edward I, this famous throne recently received its first comprehensive archaeological study.

The results emphasise how the current form of the Stone of Scone can only be understood alongside the evolution of the chair that held it.

Edward I treated the Stone of Scone as a relic and presented it, along with the Scottish crown and sceptre, to the shrine of St Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey on 18 June 1297.

He ordered the construction of a great gilt-bronze chair to incorporate the Stone as its seat.

The chair was cast but was scrapped before it was finished and a new one made of oak, thereby reducing its weight from three-quarters of a ton to one-quarter.

St Edward’s Chair, as it is properly known (‘Coronation Chair’ is a relatively recent naming), was designed as a liturgical furnishing that would stand close to the shrine altar, where it served as a seat for priests officiating at masses.

Opinion is divided as to when the Chair was first used in the coronation ritual, but it was no later than 1399, when Henry IV was crowned.

A manuscript illustration of the coronation of Edward II in 1308, however, shows the king seated in what is almost certainly the Coronation Chair.

It is an extraordinary fact that, like a surprising number of artefacts and structures of first-rank importance, the Coronation Chair had never been systematically studied and recorded until now.

John Carter’s sketches of 1767 provided the basis for all known drawings but neither he nor any other antiquary recorded how the Chair was constructed or unravelled the vicissitudes of its later history.

Like most ancient artefacts of complex construction, it has undergone fundamental alterations as well as suffered deterioration over the centuries.

In fact, very little has been written about the Chair at all, as opposed to the Stone that it encapsulated.

The Chair has been the subject of a dozen books, scores of articles, Parliamentary debates, a commercial film, theft, hoaxes, and much political posturing.

Myths and misdirection

The Stone has accrued a huge mythology, but that is wholly of Medieval or later invention, as Nick Aitchison demonstrated in his study Scotland’s Stone of Destiny (2000).

The block is made of Lower Old Red Sandstone and has a geological signature that confirms it derives from the Scone Formation.

It did not originate in Egypt, Ireland or the west of Scotland, as the Romantic tales would have led us to believe.

Indeed, the Stone’s spurious biblical connection (as ‘Jacob’s Pillow’ – the stone on which, according to the Book of Genesis, the sleeping Jacob had a vision) was already being ridiculed in 1600 by William Camden.

Much of the Stone’s pseudo-history is of even more recent invention.

The first archaeologically objective study of the Stone took place in 1996, when it was removed from the Coronation Chair and sent to Edinburgh Castle, where it currently resides on loan from the Crown.

Under the direction of David Breeze and Richard Welander, Historic Scotland carried out a detailed examination, the findings of which were published by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland: The Stone of Destiny: artefact and icon (2003).

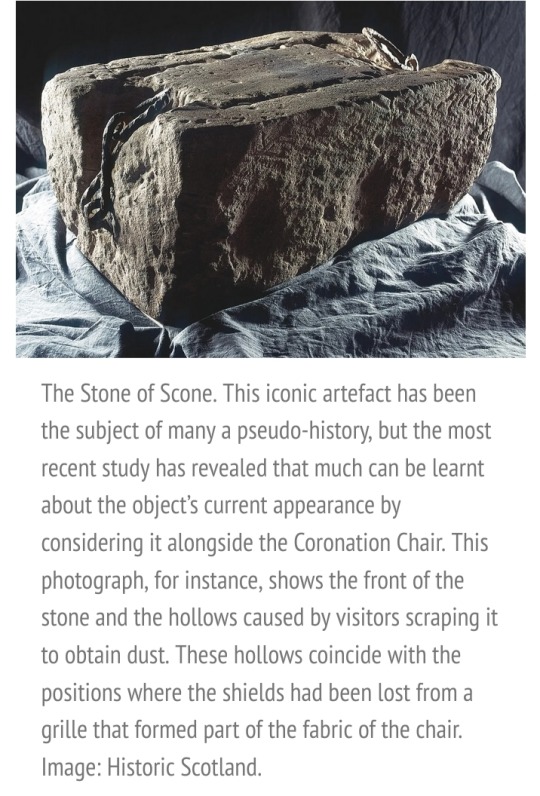

The Stone’s intimate relationship to the Chair has never been explored, however, resulting in the wholly unwarranted assumption by past commentators that the physical features exhibited by the block today relate to its pre-1296 history in Scotland.

This in turn has given rise to the invention of historical scenarios to explain these features.

Some writers have pronounced the block to be a Roman building stone or part of a pagan altar; others have claimed a Bronze Age or Pictish ancestry.

The iron links and rings that are attached to the two ends of the block have given rise to much comment, as well as claims that they were inserted for the purpose of carrying the Stone from site to site in Scotland, or alternatively for transporting it to London.

Finally, there are the conspiracy theorists who would have us believe that the Stone is fake.

These contentions can be refuted without exception. When we study the Chair and the Stone as archaeological artefacts, not just individually but jointly, and marry the findings with reliable historical evidence, a clear picture emerges.

The most fundamental misapprehension is that the Stone (as we see it today) was brought from Scone and placed in a made-to-measure compartment under the seat of the Chair, and that it simply sat there for the next 700 years.

In reality, the Chair and the Stone were made for one another, and both have been subjected to significant change over the centuries.

Made for each other

There is no basis for casting doubt on the authenticity of the Stone of Scone, or for claiming it as a Roman ashlar or a Pictish symbol-stone.

The upper and lower faces are natural bedding planes and are untooled, although the former is well worn through its prolonged use as a seat.

The four vertical edges were all crisply dressed in 1297 to create a close-fitting, rectangular seat for the new Chair.

One of the revelations of the 2010 study was the fact that the Coronation Chair did not have a wooden seat-board until the 16th or 17th century: the Stone itself was the seat.

The Chair frame is made of oak and comprises four corner-posts, and a series of moulded horizontal rails.

The sides of the Chair have upswept arms, which were originally decorated with carved lions.

The joints are mortised-and-tenoned but are inherently weak. The frame gets its structural strength from the lining of thick planks.

Below seat level, the sides are pierced by large quatrefoils – that is, four partially overlapping circles creating a shape akin to a stylised four-leaf clover – each of which originally had a painted heraldic shield at its centre.

By the 1820s, the shields had all been lost, and the quatrefoil grille at the front had gone too.

The gang that stole the Stone in 1950 also smashed the front rail and further weakened the frame. A replacement grille has now been fitted to restore its structural strength.

The Stone of Scone rested in this compartment and could be glimpsed on all sides; its top was fully exposed.

William Lethaby’s 1906 reconstruction of the gilt figure of a king in the back of the Chair. He is depicted seated on a low throne, with his feet resting on a lion. Only the lower part of this image survives today.

Externally, the sides and back of the Chair were carved and moulded with Gothic arcades.

The corner-posts too were embellished with blind, pointed – lancet – arches, and surmounted by pinnacles from which decorative foliage or ‘crockets’ sprouted.

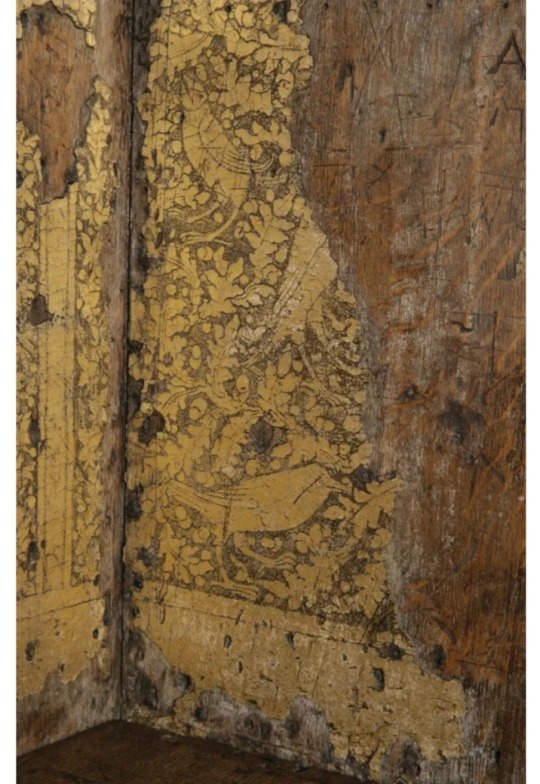

No timber was originally visible, though, as the surfaces were entirely covered with decoratively punched gilding and pseudo-enamels.

There were also many pieces of coloured glass inlaid into the carved decoration. These inserts would have carried painted and gilded motifs, similar to those found in profusion on the altarpiece of Henry III known as the Westminster Retable (c. 1270).

Internally, the Chair was uncarved but was covered with gold leaf. It bore finely punched decoration - showing birds, animals, vegetation, and Gothic motifs.

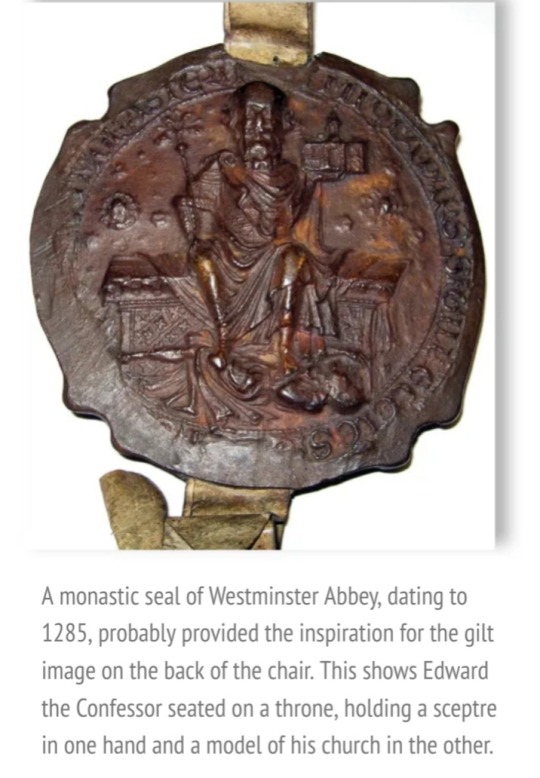

Dominating the centre of the back was the seated figure of a king with his feet resting on a lion, almost certainly Edward the Confessor.

It was the work of Walter of Durham, principal painter to the court of Edward I. Unfortunately, most of this impressive display has been lost over time.

A detail of the punch-decorated gilding surviving inside the Chair’s left arm, showing birds amid vegetation.

The conservation programme of 2010-2012 was undertaken by Marie Louise Sauerberg, then of the Hamilton Kerr Institute, but now Westminster Abbey’s Senior Conservator.

Her work was key to unlocking the history of the Chair’s decoration, particularly by demonstrating that the all-over gilded appearance was primary.

In the 1950s, it had been suggested that the Chair was initially white in colour, emulating King Solomon’s ivory throne.

Royal pride

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the Coronation Chair today is the gilt plinth on which it is raised, comprising four magnificent lions with Oriental features.

These were fitted in 1727 by the royal furniture-maker for the coronation of George II and replaced an earlier plinth, which also incorporated lions.

That plinth may have been made in 1509 for the coronation of Henry VIII.

Since both lion-plinths were fixed to the Chair frame, the Stone could only be inserted into the seat compartment from above, but this was not the original arrangement.

Walter of Durham’s exquisite gilt decoration would have been wrecked by manhandling a close-fitting, 3-cwt block of sandstone through the seat compartment.

Every time the Chair was required for a coronation, it had to be taken from the Confessor’s chapel through a narrow doorway, carried down steps, and repositioned in the Abbey.

Four operations were involved in extricating and replacing the Stone.

Almost certainly, the original plinth was a separate construction that rested on the floor. The Stone was placed on it and the Chair lowered over that.

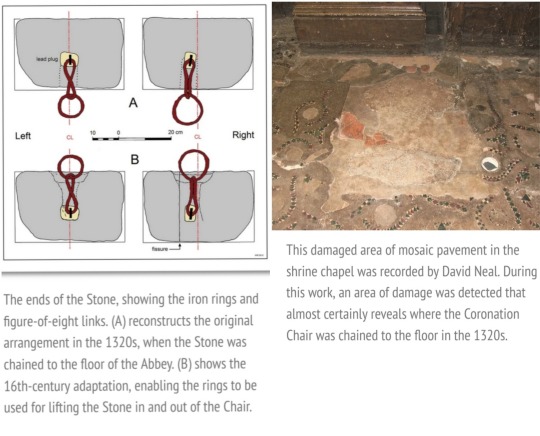

Iron links and rings are attached to the ends of the Stone by staples set into lead plugs.

Various theories about their date and purpose have been advanced, all based on the assumption that they were used for lifting or carrying.

But nobody seems to have noticed that their fixing points are below the Stone’s centre-of-gravity, which means that it would instantly rotate when lifted.

Also, the links are not long enough for the rings to clear the top of the Stone, making it impossible to thread a carrying-pole of adequate diameter through them.

It is now clear that the ironwork was attached to the block in c. 1324-1327, on the instruction of Abbot Curtlyngton, expressly for the purpose of chaining it to the floor of the chapel.

At the time, he was under pressure from Edward III to relinquish the Stone so that it could be used as a bargaining counter with the Scots.

The abbot refused and the chronicler Geoffrey le Baker tells us that ‘the stone was now fixed by iron chains to the floor of Westminster Abbey under the royal throne’.

Since enforced removal of an object gifted to a shrine would have constituted sacrilege, the king backed down.

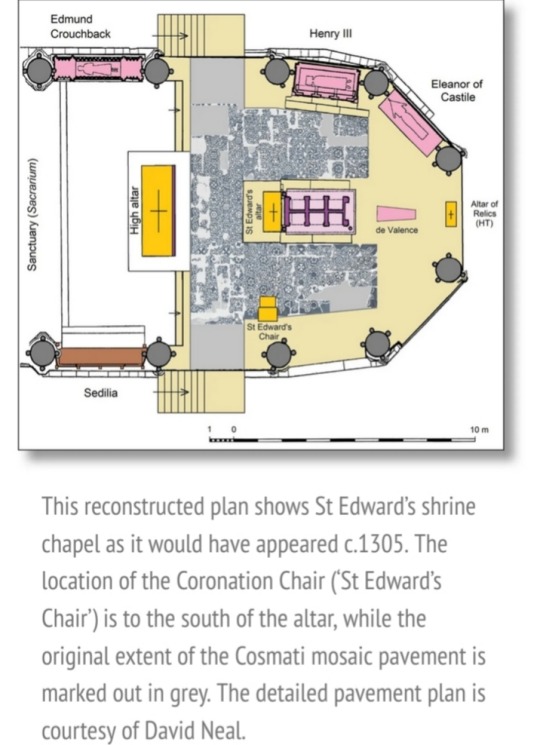

The 13th-century marble and glass mosaic pavement in the Shrine chapel has been meticulously recorded by David Neal.

During his work, we noticed that a square area to the south of the altar, where the mass priest’s seat would have stood, had been destroyed.

Almost certainly, this marks the place where the pavement was broken through in the 1320s to embed anchors in the floor for the chains that secured the Stone.

When the Chair was fitted with the first of the lion plinths, a new means of manoeuvring the Stone in and out of the seat compartment had to be found: the only route was from above.

The iron fittings were now pressed into service as lifting devices. Channels were crudely cut into the ends of the Stone so that the links could stand up, rather than hang down, and ropes could be passed through the rings.

The tendency for the unbalanced Stone to rotate was largely mitigated by the links being constrained in channels.

It was a clumsy compromise but it worked, albeit inflicting damage on the gilded interior of the Chair, as the Stone was hauled in and out.

The institutional history of Westminster Abbey in the two decades following its dissolution in 1540 is complex, but remarkably, the shrine of St Edward and the royal tombs survived.

The later 16th century saw a fashion for attaching historical labels (tabulae) to features around the Abbey, including the shrine, tombs and St Edward’s Chair.

These were generally painted either directly on the object or on a board, but in the case of the Chair, it seems that there was initially an intention to insert an inscribed brass plate in the upper face of the Stone.

The rectangular outline for the plate was roughly chiselled. The matrix was never fully cut and the project aborted. A painted label on a board was provided instead.

The change of plan most likely resulted from a decision to fit a timber seat-board over the Stone that had two further consequences.

First, battens had to be fitted to the sides of the Chair to support the seat-board, thereby reducing the size of the Stone compartment opening.

The block had to be shortened, and both ends were cut back by c. 15mm.

Second, the iron rings projected above the top of the Stone, obstructing the fixing of the seat.

To solve this problem, housings were hacked into the top of the Stone, allowing the rings to lie flat.

13th-century survival

Since the late 16th century, travellers and antiquaries have written accounts of the Chair, from which we learn that it suffered casual abuse until Queen Victoria came to the throne.

All the glass inserts were prised out, scores of slices were removed from the frame with pocket-knives and taken as souvenirs, names and initials were liberally carved in the wood, and the shields were stolen from the quatrefoils, exposing the sides of the Stone, which was then scraped with knives to acquire samples of its dust.

Three shallow scoops scored into the front edge result from this activity.

In the 18th century, when the second lion-plinth and new seat-board were fitted, further modifications to both the Chair and Stone occurred.

Although the latter had been shortened, the iron staples to which the rings were attached projected awkwardly, gouging the sides of the Chair every time the Stone was moved.

To ease this, the crowns of the staples were filed down. Something even more barbaric happened between 1727 and 1821: the lower edges of the Stone were broken away with nine hammer-blows.

There is no obvious explanation for this – perhaps the pieces were sold as souvenirs.

Even in more recent times, the Chair has suffered periodically.

In 1887, the Office of Works painted it brown for the celebration of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee.

A public outcry ensued and great damage was done to the gilt decoration when trying to remove the paint.

In 1914, Suffragettes attached a home-made bomb to one of the Chair’s pinnacles, causing more damage.

In 1939-1945, the Chair was stored in the crypt of Gloucester Cathedral, where it narrowly escaped destruction by an infestation of dry rot.

Finally, as well as vandalising the Chair, the gang that stole the Stone in 1950 dropped it and broke it.

Given this long and varied history, it is perhaps remarkable that the Chair survives at all.

Yet our study makes it clear that, despite having fallen victim to neglect, politics and the whims of fashion, St Edward’s Chair and the Stone of Scone – in the form we know it today – are two components of a single artefact, made in the 1290s.

They have an integrated physical history, and shared archaeology: one cannot be understood without the other.

#Coronation Chair#St Edward's Chair#King Edward's Chair#Stone of Scone#Coronation Stone#King Edward I#British History#British Royal Family#Queen Victoria#Queen Elizabeth II#medieval throne#Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria (1887)#Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II (2012)

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

'uh but the coronation has brought in money' of course it has, to london, where wealth and tourism is centralised, where multiple millionaires live. it's not going to magically alleviate the cost of living crisis around the rest of the country.

#uk politics#the coronation#everything is horrible and tiring#i would like to advocate for the return to stone age

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

ghetsis back when he tried to become the modern day hero of truth but the light stone thought his aura was rancid and flashbanged him instead

#n harmonia#ghetsis#ghetsis harmonia#unova#pokemon#sketches#pokemon bw#if you put baby ghetsis and baby n in a vacuum they would grow up to be nearly identical. For reasons#also the monarch of team plasma is a generational thing with the descendant of harmonia being crowned as soon as theyre deemed an adult (18)#the light stone was rediscovered by team plasma when ghetsis was young so on his very coronation day he tried to reawaken reshiram himself.#as previously stated it failed to devastating results. so when ghetsis ‘had’ his own kid he not only groomed him to be the perfect candidate#but also had him go out on his journey to prove to reshiram that n would do whatever it took to pursue the truth. even participating in the#gym challenge he detested. only then could he earn reshiram’s favor

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

I keep thinking about how from all of the Dead Three' Chosen, Gortash is the only one offering an alliance, and why is that.

It stirs from their goals, I believe.

Orin's ultimate goal is Bhaal's goal, i.e. the destruction of the world.

What is Ketheric's ultimate goal I know not, but I suspect his ultimate goal has been achieved already - Isobel is alive, and now all what's left for him is to serve Myrkul for the miracle of bringing his daughter back.

Gortash's goal is world domination. And, as we could see in Control the Elder Brain ending, world domination is a...lonely thing.

In the end there is no one but you and your army of thralls. No one to see you shine, no one to bask in your glory.

And if there's no one to see you rule, then are you even ruling?

I think of Jaheira's comment about what "of course Gortash is genuine, he needs someone to bask in his glory".

And this is why he ultimately seeks an alliance with Tav/Durge, this is why he specifically requires his ally to be his equal.

Because, maybe subconsciously, but he knows what the power he seeks is a lonely business. And he wants, no, needs someone to witness his greatness, someone he can share it with, someone who could GET it.

He genuinely plans to share his rule and power with another person because he needs someone - equal to him - to see and acknowledge his success. That's why, ironically, he can be a legit ally if your actions and goals do not contradict his.

This is why it's "our tyranny".

And that's so fucking sad.

#something something power is loneliness#ultimate power doubly so#something something gortash if doesn't know then at least suspects it#he needs an equal by his side#this is why he doesn't try to take the stones from you without genuinely trying to make this 'working together' thing real#this is why his coronation is practically a showing off to durge (esp durge) or tav#witness me see my glory#i am emotional about this rat ass of a tyrant#lord enver gortash#enver gortash#bg3 spoilers#baldurs gate 3

475 notes

·

View notes

Text

Master Eight Arc may have been done poorly, but at least it had the biggest all-star crossover in the series

#Pokemon#anipoke#pokeani#Master 8#Master Eight#Pokemon Master Eight#World Coronation Series#Pokemon World Coronation Series#Pokemon Master Tournament#Ash Ketchum#Lance#Steven Stone#Cynthia#Diantha#Iris#Leon#Champion Lance#Champion Steven#Champion Cynthia#Champion Diantha#Champion Leon#Champion Iris#Pocket Monsters

140 notes

·

View notes

Video

undefined

tumblr

The Stone of Destiny being transported from Edinburgh Castle for the coronation of Charles III.

#stone of destiny#scotland#scottish#history#charles iii#coronation#royal family#king charles#king charles iii

397 notes

·

View notes

Text

With the Stone of Scone leaving it is a good time to remind everyone that it was stolen from Scotland by King Edward I and kept for centuries until 1950 when a group of four Glasgow University students snuck in to Westminster Abbey and took it back. It’s an amazing story and a miracle they managed to pull it off given how absolutely terrible their plan was (for example, before they even got out of the Abbey they dropped the stone on the ground and it split in two):

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

King Gustav III's King's Sword

The sword was commissioned by King Gustav III for his coronation in 1772. The rapier is signed Weilm Klein, the signature of its maker.

Courtesy: Royalpalaces.se

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

On December 25th 1950 four young Scots liberated the Stone of Destiny from Westminster Abbey.

Here is a report from The newspaper The Guardian of the story that was enfolding.

“Scotland Yard had no further news last night of the Coronation Stone, the Stone of Scone, or the Stone of Destiny as it is variously called. There is "absolutely no trace” of it, but the police are still busy all over the country - especially on northward routes - looking for it. The stone was stolen in the early hours of Christmas Day from Westminster Abbey.

One theory is that the thieves - or from the point of view of certain Scotsmen, “liberator” - hid in a chapel overnight in readiness for their coup. They had first to prise the stone out of its housing under the Coronation Chair, which is behind the high altar. Then the stone - which weighs four hundredweight and measures roughly 26 inches by 16 inches by 11 inches - had to be carried round to the Poet’s Corner door where, presumably, it was loaded into a car. The police are looking for a man and a woman in a Ford Anglia car which was seen near the abbey in the small hours of the morning.

Descriptions of them have been circulated, and the police say they speak with Scottish accents. It is taken for granted that the stone has been stolen by Scottish Nationalists. The stone, which is rectangular and is of yellowish sandstone, has two rings let into it and normally lies behind a grille under the Coronation Chair. In 1940 it was buried in the abbey and the secret position marked on the chart which was sent to Canada for safety.

It is believed to have left the abbey only once, when it was taken across to Westminster Hall and used for the installation of Cromwell as Lord Protector in 1657. It has been “attacked” before and was once slightly damaged (in 1914), when a bomb was placed under the Coronation Chair during the woman suffrage agitation. Twenty-five years ago, Mr David Kirkwood was given permission to bring a bill for the removal of the stone to Holyrood Palace, but the bill went no farther.

The Coronation Chair is the oldest piece of furniture in the abbey, and has been used for 27 coronations. It was damaged by the removal of the stone; part of it was broken and a strip of wood from the grille was found lying on the floor. Scotland Yard sent a number of CID men, including fingerprint experts, to the abbey and have circulated a description of the stone.

There is no official confirmation of a rumour that a wristwatch was found near the Coronation Chair, but it has been stated that freshly carved initials “JFS” have been found in the gilding on the front of the chair. It seemed evident that the intruders were amateurs, for they made little attempt to hide their tracks. Whether or not they will make straight for Scotland with the stone is doubtful, though one Scottish paper said this morning that the stone might already have crossed the border.

It should not prove a difficult object to hide once it can be taken out of the car which is carrying it, and the police of the two countries are likely to find themselves with a difficult job - not so much in finding the culprits but in finding the stone. If anybody is brought to court either on a charge of stealing or of sacrilege, the case should produce some fine legal and historical points.“

In addition to numerous road blocks, a special watch was kept at docks and airports, while hundreds of CID officers checked hotels and B&Bs in the North of England. Following the delivery of an anonymous petition promising the “return” of the Stone – on condition that it would remain in Scotland – to a Glasgow newspaper, Special Branch officers soon started making enquiries about student political bodies at Glasgow University.

The liberators were indeed Scots, four students from The University of Glasgow, from the University of Glasgow (Ian Hamilton, Gavin Vernon, Kay Matheson and Alan Stuart, travelled to London, entered the Abbey in the small hours of Christmas Day and nabbed the Stone from beneath the coronation throne. They dropped it by accident and it broke in two. They loaded the Stone into their car boot and brought it back to Scotland – despite roadblocks and police searches.

The four became notorious for the daring heist and in Scotland they achieved nigh-on hero status, while in contrast the English were somewhat bewildered. All four of the group were interviewed and all later confessed to their involvement with the exception of Ian Hamilton. The authorities decided not to prosecute as the potential for the event to become politicised was far too great.

At the time, the leader of Scottish Covenant Association, Nigel Tranter commented

“This venture may appear foolish and childish on the surface, but it will have the effect down South of focusing attention on Scotland’s complaints. It takes a lot to get any news of Scotland’s national existence into the English Press, and this sort of thing is the only type of Home Rule story that gets a break in the English newspapers.”

Mungo Murray, 7th Earl of Mansfield and Lord of Scone, the spiritual home of the stone waded in with how he would be “extremely reluctant” to hand the Stone “to the English authorities,” assuming it should be returned to his property at Scone Palace. “In view of the fact that the Stone undoubtedly pertains to the line of Scottish kings, it belongs to the King as King of Scotland, not as King of England,” he said. “In the future the Stone should be kept at Scone or Holyrood instead of Westminster.”

Despite their best efforts, the authorities on both sides of the Border were unable to trace the Stone, at least until April 1951 when – draped in the Scottish Saltire – it was ceremonially deposited at the site of the high altar within the ruins of Arbroath Abbey. The Stone was accompanied by two unsigned letters, one addressed to the King, the other to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, described as “successor to the Abbots of Scone” and therefore the Stone’s “natural guardians”.

It would be a further 43 years before a UK Government agreed that the Stone. when not required for use in such ceremonies, I covered this in depth on St Andrews Day.

Church-bells across Scotland didn’t ring out in celebration – as portrayed in the 2008 film, The Stone of Destiny – yet Ian Hamilton and his friends nevertheless showed how what had seemed permanent and immutable could be changed.

The Stone of Destiny will again be on the move and will be the centrepiece of a new £26.5m museum, in Perth. Construction work on the new museum at Perth City Hall is due to start in February, with it scheduled to open in 2024. The third pic shows an artist impression of how it might look.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

/ If your muse had to share the bus seat with one of my servant muses, who would it be-

#GOING TO THE MUSEUM!!!#but also imagine a condition of the trip is that u have to stay with ur pair to not get completely lost#ngl i would be like haha oops this museum is so stacked oh nooo -spiritually clinging to c.onstantine-/J#imagine ur muse get stuck with my c.asgil and they are forced to stay on the stamps and seals section of the museum for 3 hours IUYTRITUYR#or a.vicebron just -stares at rocks in the geology section for hours-#personally speaking i think going with d.aybit would be the most fun; bc he would go straight to the dinosaurs section#and i love seeing dinosaur fossils and displays; natural science museums my beloveds#i think it would also be very funny with certain servants like imagine seeing that one golden gauntlet said to belong to king charlemagne#and charlie just; :TURNS AROUND: !!!!#t.ezca seeing the t.ezcatlipoca mask and just: -peace sign-#m.octezuma seeing his coronation stone;#o.dy seeing the vases depicting his story; etc etc#and and matching souvenir shirts yes#;ooc#ooc

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

At work and suddenly remembered that the Regalians started stoning Gregor and Ares to death with random stuff bc Gregor didn’t murder a toddler???

#like hello small boy and already ostracized friend of said boy#time to throw stone coronation presents at ur heads#tuc#the underland chronicles#al chatters

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

DM: You've just finished your road trip to see all your families. Once you get back to the city you chill for a few days. Maybe take part in a few games of Persia's national sport, volleyball...

Party: *laugh*

DM: And then Vikavar, the Master of Ceremonies, pays you a visit at TTC manor to discuss Billie's coronation.

Adam (playing Billie): Does he need the Gand?

DM: No, he borrowed it before you left and he's already familiarized himself with the ancient ceremonies of Gandarall recorded in it. The next step before you can be officially recognised - and you're not going to like this - is you have to surrender the crown of Gandarall and the Herald of Mercy sword to him for three days.

Adam: I stiffen at this news.

DM: According to Gandarall custom, when a new ruler is chosen the sword and crown must be put on display for three days. Anyone in the kingdom can try them on, to strengthen the conviction that you are the only legitimate heir. They'll be under the highest protection available to the throne of Persia.

Adam: Ugh... I guess I have no choice. I hand them over.

#funny#dnd#coronation#sword in the stone#Billie#Lyra DM#just little d&d things#ooc#NPCs#Vikavar#volleyball#the Gand#Gandarall#travelling trauma centre

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

If only the Master Tournament also included a special double battle exhibition match between these four fan favorite Champions before the finals

#pokemon#champion lance#champion steven#champion cynthia#champion diantha#lance#steven stone#cynthia#diantha#master 8#master eight#pokemon master 8#pokemon master eight#world coronation series#pokemon world coronation series#pokemon master tournament#pokemon journeys#pokemon ultimate journeys#mega evolution#dynamax#anipoke#pokeani

155 notes

·

View notes