#Stone of Scone

Text

With the Stone of Scone leaving it is a good time to remind everyone that it was stolen from Scotland by King Edward I and kept for centuries until 1950 when a group of four Glasgow University students snuck in to Westminster Abbey and took it back. It’s an amazing story and a miracle they managed to pull it off given how absolutely terrible their plan was (for example, before they even got out of the Abbey they dropped the stone on the ground and it split in two):

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

On 11th of April 1951 The Stone of Scone, the stone upon which Scottish monarchs were traditionally crowned, was found on the site of the altar of Arbroath Abbey.

It’s always good to get details from the era in posts, this is a contemporary newspaper report of the event.

Three and a half months after its removal from the Coronation Chair in Westminster Abbey early on Christmas morning, the Stone of Scone was to-day deposited in Arbroath Abbey in Scotland. Three men drove up to the abbey and carried the stone, which was draped in a St. Andrew’s flag along the main aisle before laying it at the high altar, on the grave of King William the Lion of Scotland.

The stone was handed over to Mr. James Wishart, custodian of the abbey, who remained with it until a detachment from Angus County Police took possession. Afterwards it was removed to Forfar, where it lay in a locked cell at police headquarters for the night. On top of the stone two unsigned letters were left: one addressed to the King and the other to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland as “successor to the Abbots of Scone.”

The letter to the King read:

“Unto his Majesty King George VI, the address of his Majesty’s Scottish subjects who removed the Stone of Destiny from Westminster Abbey and have since retained it in Scotland, humbly showeth.

"That in their actions they, as loyal subjects, have intended no indignity or injury to his Majesty or to the Royal Family.

"That they have been inspired in all they have done by their deep love of his Majesty’s realm of Scotland and by their desire to compel the attention of his Majesty’s Minister to the widely expressed demand of Scottish people for a measure of self-government.

"That in removing the Stone of Destiny they were restoring to the people of Scotland the most ancient and most honourable part of the Scottish regalia, which for many centuries was venerated as the palladium of their liberty and which in 1296 was violently pillaged from Scotland in the false hope that it would be the symbol of their humiliation and conquest.

"That the stone was kept in Westminster Abbey in defiance of a royal command and despite the promise of its return to Scotland.

"That by no other means than the forceful removal of the stone from Westminster Abbey was it possible even to secure discussion as to its rightful resting place.

"That it is the earnest hope of his Majesty’s Scottish people that arrangements for the proper disposition of the stone may now be made after consultation with the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland who as successors of the Abbots of Scone are its natural guardians.

"That it is the earnest prayer of his Majesty’s loyal subjects who have served his Majesty both in peace and war that the blessing of Almighty God be with the King and all his peoples so that in peace they may enjoy the freedom which sustains the loyalty of affection rather than the obedience of servility. God save the King.”

The letter which was addressed to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland asked that the representatives of the Church should “speak for the whole people and arrange with the public authorities in England that the Stone of Destiny will be retained in Scotland.”

wo Arbroath town councillors, Mr. D.A. Gardner and Mr. F.W.A. Thornton, both of whom are prominently associated with the Scottish Convention movement, were waiting at the entrance to the abbey when the three men arrived. Mr. Thornton helped them to carry the stone in, and Mr. Gardner went to Arbroath police station to inform the police that the stone was lying in the abbey.

Mr. Wishart, who is 63 and has been custodian at the abbey for nine years, told a reporter that the men got out of the car and started to take a heavy object from the back seat. Councillor Gardner came up and said: “Is that the Stone of Destiny you have?”

Mr. Wishart said that Mr. Thornton and three men carried the stone on a wooden litter up what used to be the nave of the abbey between the ruins of the pillars. “They laid it at the three stones which marked the site of the high altar. They carried the stone in a reverent manner, their heads were uncovered, and it was a solemn and impressive little ceremony. The men shook hands with me and wished me the best of luck and then went. As soon as I knew that the Stone of Destiny had been placed in my charge I locked the gates.”

Mr. Wishart said that the three men were “young well set-up lads,” but apart from that he was unable to give a description of them. The car was big and dark-coloured, but he did not note the registration number. “I have always told visitors that one day the Stone of Destiny would come to this historic spot,” he said, “and I am glad that my words have come true.”

On 13 April the Stone was returned to Westminster Abbey.

A wee bit history behind the stone, the first Scottish monarch to be crowned atop the stone in the 11th century, with John Balliol the last King to use the stone on Scottish soil in 1292.

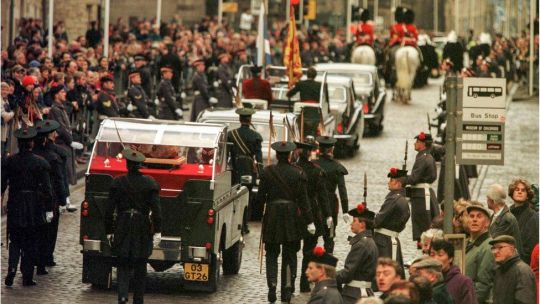

In 1296, the stone was captured by Edward I as spoils of war and taken to Westminster Abbey. On St Andrews Day 1996, the Stone of Destiny was legally returned to Scotland with a ceremony and celebration befitting its status. Since that day, it has remained within the confines of Edinburgh Castle alongside the Honours of Scotland. Thousands lined the Royal Mile to see the stone escorted from the Palace of Holyrood House to the castle.

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

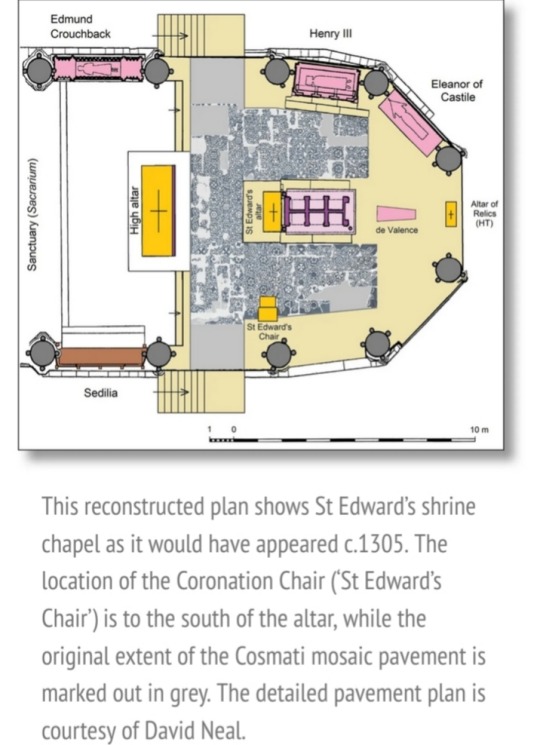

The Coronation Chair: Anatomy of a Medieval throne

The Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II prompted the first comprehensive archaeological study of the Medieval throne on which British monarchs are crowned.

It has been battered and vandalised over the ages, but unpicking this majestic artefact’s evolution shed new light on both its original form and that of the enigmatic Stone of Scone, as Warwick Rodwell reveals.

10 August 2013

The Coronation Chair has been illustrated and described since the 14th century, and is renowned the world over.

For hundreds of years, this piece of Medieval furniture has played a seminal role in the anointing and crowning of English monarchs.

It was last used at the coronation of HM The Queen on 2 June 1953, the Diamond Jubilee of which was celebrated this year.

To mark the occasion in 2010-2012, the Chair underwent a long-overdue programme of cleaning, conservation and redisplay in Westminster Abbey.

Concurrently, a detailed archaeological study was carried out and the Chair was comprehensively recorded for the first time.

The project led to a radically new understanding of its construction and decoration, and of its relationship to the Stone of Scone, which was embodied in its seat.

Spoils of war

The origins of the Chair are well known. Indeed, the documentation accompanying its manufacture in the 1290s is still preserved.

Following Edward I’s victory over the Scots in 1296, state documents and items of regalia were surrendered and taken to London as spoils of war.

One of those items was a ceremonial block of sandstone upon which Scottish kings had hitherto been inaugurated at Scone Abbey in Perthshire, the last being John Balliol in 1292.

The Coronation Chair and Stone of Scone.

Constructed in the 1290s on the orders of Edward I, this famous throne recently received its first comprehensive archaeological study.

The results emphasise how the current form of the Stone of Scone can only be understood alongside the evolution of the chair that held it.

Edward I treated the Stone of Scone as a relic and presented it, along with the Scottish crown and sceptre, to the shrine of St Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey on 18 June 1297.

He ordered the construction of a great gilt-bronze chair to incorporate the Stone as its seat.

The chair was cast but was scrapped before it was finished and a new one made of oak, thereby reducing its weight from three-quarters of a ton to one-quarter.

St Edward’s Chair, as it is properly known (‘Coronation Chair’ is a relatively recent naming), was designed as a liturgical furnishing that would stand close to the shrine altar, where it served as a seat for priests officiating at masses.

Opinion is divided as to when the Chair was first used in the coronation ritual, but it was no later than 1399, when Henry IV was crowned.

A manuscript illustration of the coronation of Edward II in 1308, however, shows the king seated in what is almost certainly the Coronation Chair.

It is an extraordinary fact that, like a surprising number of artefacts and structures of first-rank importance, the Coronation Chair had never been systematically studied and recorded until now.

John Carter’s sketches of 1767 provided the basis for all known drawings but neither he nor any other antiquary recorded how the Chair was constructed or unravelled the vicissitudes of its later history.

Like most ancient artefacts of complex construction, it has undergone fundamental alterations as well as suffered deterioration over the centuries.

In fact, very little has been written about the Chair at all, as opposed to the Stone that it encapsulated.

The Chair has been the subject of a dozen books, scores of articles, Parliamentary debates, a commercial film, theft, hoaxes, and much political posturing.

Myths and misdirection

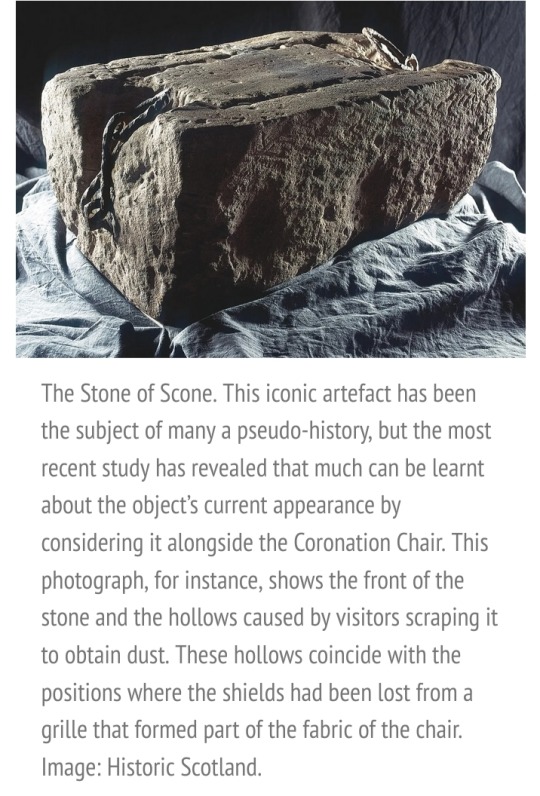

The Stone has accrued a huge mythology, but that is wholly of Medieval or later invention, as Nick Aitchison demonstrated in his study Scotland’s Stone of Destiny (2000).

The block is made of Lower Old Red Sandstone and has a geological signature that confirms it derives from the Scone Formation.

It did not originate in Egypt, Ireland or the west of Scotland, as the Romantic tales would have led us to believe.

Indeed, the Stone’s spurious biblical connection (as ‘Jacob’s Pillow’ – the stone on which, according to the Book of Genesis, the sleeping Jacob had a vision) was already being ridiculed in 1600 by William Camden.

Much of the Stone’s pseudo-history is of even more recent invention.

The first archaeologically objective study of the Stone took place in 1996, when it was removed from the Coronation Chair and sent to Edinburgh Castle, where it currently resides on loan from the Crown.

Under the direction of David Breeze and Richard Welander, Historic Scotland carried out a detailed examination, the findings of which were published by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland: The Stone of Destiny: artefact and icon (2003).

The Stone’s intimate relationship to the Chair has never been explored, however, resulting in the wholly unwarranted assumption by past commentators that the physical features exhibited by the block today relate to its pre-1296 history in Scotland.

This in turn has given rise to the invention of historical scenarios to explain these features.

Some writers have pronounced the block to be a Roman building stone or part of a pagan altar; others have claimed a Bronze Age or Pictish ancestry.

The iron links and rings that are attached to the two ends of the block have given rise to much comment, as well as claims that they were inserted for the purpose of carrying the Stone from site to site in Scotland, or alternatively for transporting it to London.

Finally, there are the conspiracy theorists who would have us believe that the Stone is fake.

These contentions can be refuted without exception. When we study the Chair and the Stone as archaeological artefacts, not just individually but jointly, and marry the findings with reliable historical evidence, a clear picture emerges.

The most fundamental misapprehension is that the Stone (as we see it today) was brought from Scone and placed in a made-to-measure compartment under the seat of the Chair, and that it simply sat there for the next 700 years.

In reality, the Chair and the Stone were made for one another, and both have been subjected to significant change over the centuries.

Made for each other

There is no basis for casting doubt on the authenticity of the Stone of Scone, or for claiming it as a Roman ashlar or a Pictish symbol-stone.

The upper and lower faces are natural bedding planes and are untooled, although the former is well worn through its prolonged use as a seat.

The four vertical edges were all crisply dressed in 1297 to create a close-fitting, rectangular seat for the new Chair.

One of the revelations of the 2010 study was the fact that the Coronation Chair did not have a wooden seat-board until the 16th or 17th century: the Stone itself was the seat.

The Chair frame is made of oak and comprises four corner-posts, and a series of moulded horizontal rails.

The sides of the Chair have upswept arms, which were originally decorated with carved lions.

The joints are mortised-and-tenoned but are inherently weak. The frame gets its structural strength from the lining of thick planks.

Below seat level, the sides are pierced by large quatrefoils – that is, four partially overlapping circles creating a shape akin to a stylised four-leaf clover – each of which originally had a painted heraldic shield at its centre.

By the 1820s, the shields had all been lost, and the quatrefoil grille at the front had gone too.

The gang that stole the Stone in 1950 also smashed the front rail and further weakened the frame. A replacement grille has now been fitted to restore its structural strength.

The Stone of Scone rested in this compartment and could be glimpsed on all sides; its top was fully exposed.

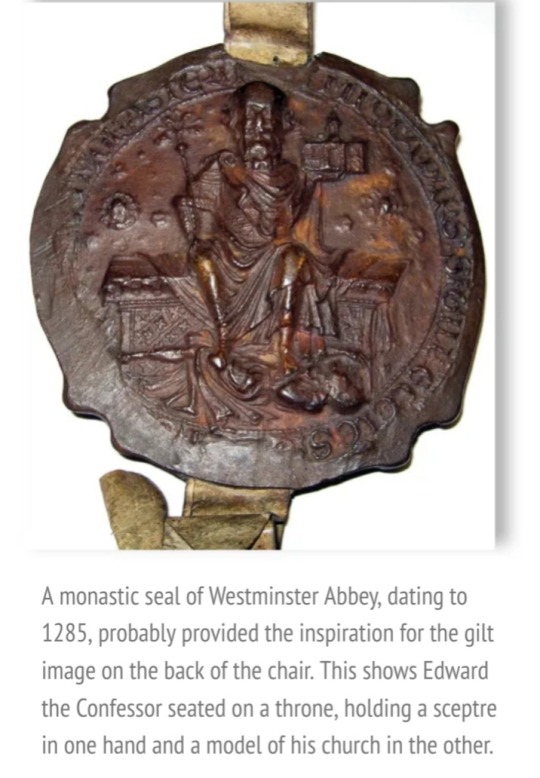

William Lethaby’s 1906 reconstruction of the gilt figure of a king in the back of the Chair. He is depicted seated on a low throne, with his feet resting on a lion. Only the lower part of this image survives today.

Externally, the sides and back of the Chair were carved and moulded with Gothic arcades.

The corner-posts too were embellished with blind, pointed – lancet – arches, and surmounted by pinnacles from which decorative foliage or ‘crockets’ sprouted.

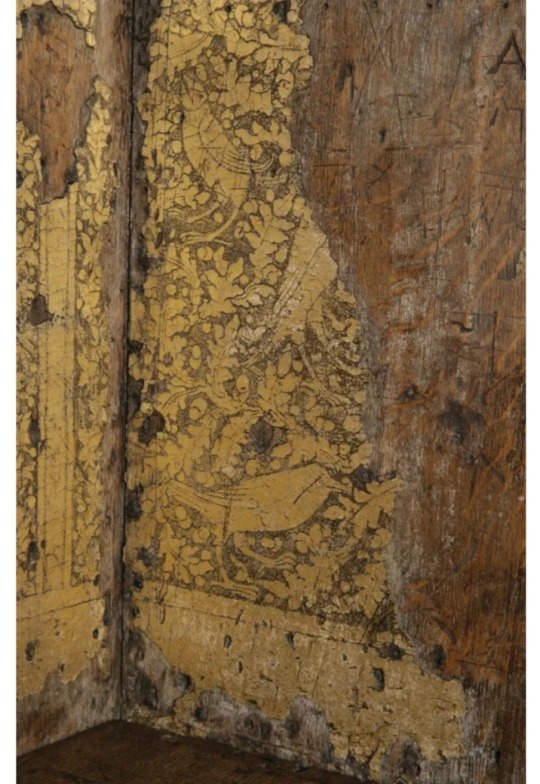

No timber was originally visible, though, as the surfaces were entirely covered with decoratively punched gilding and pseudo-enamels.

There were also many pieces of coloured glass inlaid into the carved decoration. These inserts would have carried painted and gilded motifs, similar to those found in profusion on the altarpiece of Henry III known as the Westminster Retable (c. 1270).

Internally, the Chair was uncarved but was covered with gold leaf. It bore finely punched decoration - showing birds, animals, vegetation, and Gothic motifs.

Dominating the centre of the back was the seated figure of a king with his feet resting on a lion, almost certainly Edward the Confessor.

It was the work of Walter of Durham, principal painter to the court of Edward I. Unfortunately, most of this impressive display has been lost over time.

A detail of the punch-decorated gilding surviving inside the Chair’s left arm, showing birds amid vegetation.

The conservation programme of 2010-2012 was undertaken by Marie Louise Sauerberg, then of the Hamilton Kerr Institute, but now Westminster Abbey’s Senior Conservator.

Her work was key to unlocking the history of the Chair’s decoration, particularly by demonstrating that the all-over gilded appearance was primary.

In the 1950s, it had been suggested that the Chair was initially white in colour, emulating King Solomon’s ivory throne.

Royal pride

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the Coronation Chair today is the gilt plinth on which it is raised, comprising four magnificent lions with Oriental features.

These were fitted in 1727 by the royal furniture-maker for the coronation of George II and replaced an earlier plinth, which also incorporated lions.

That plinth may have been made in 1509 for the coronation of Henry VIII.

Since both lion-plinths were fixed to the Chair frame, the Stone could only be inserted into the seat compartment from above, but this was not the original arrangement.

Walter of Durham’s exquisite gilt decoration would have been wrecked by manhandling a close-fitting, 3-cwt block of sandstone through the seat compartment.

Every time the Chair was required for a coronation, it had to be taken from the Confessor’s chapel through a narrow doorway, carried down steps, and repositioned in the Abbey.

Four operations were involved in extricating and replacing the Stone.

Almost certainly, the original plinth was a separate construction that rested on the floor. The Stone was placed on it and the Chair lowered over that.

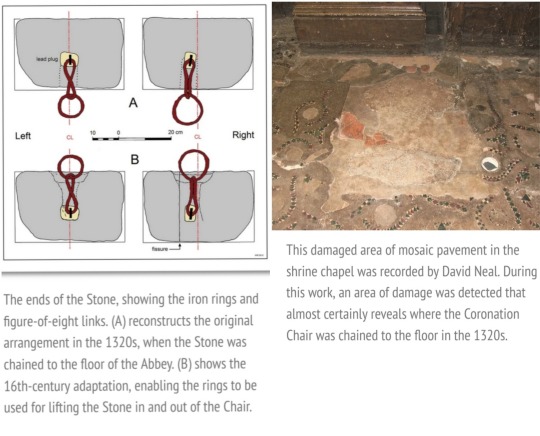

Iron links and rings are attached to the ends of the Stone by staples set into lead plugs.

Various theories about their date and purpose have been advanced, all based on the assumption that they were used for lifting or carrying.

But nobody seems to have noticed that their fixing points are below the Stone’s centre-of-gravity, which means that it would instantly rotate when lifted.

Also, the links are not long enough for the rings to clear the top of the Stone, making it impossible to thread a carrying-pole of adequate diameter through them.

It is now clear that the ironwork was attached to the block in c. 1324-1327, on the instruction of Abbot Curtlyngton, expressly for the purpose of chaining it to the floor of the chapel.

At the time, he was under pressure from Edward III to relinquish the Stone so that it could be used as a bargaining counter with the Scots.

The abbot refused and the chronicler Geoffrey le Baker tells us that ‘the stone was now fixed by iron chains to the floor of Westminster Abbey under the royal throne’.

Since enforced removal of an object gifted to a shrine would have constituted sacrilege, the king backed down.

The 13th-century marble and glass mosaic pavement in the Shrine chapel has been meticulously recorded by David Neal.

During his work, we noticed that a square area to the south of the altar, where the mass priest’s seat would have stood, had been destroyed.

Almost certainly, this marks the place where the pavement was broken through in the 1320s to embed anchors in the floor for the chains that secured the Stone.

When the Chair was fitted with the first of the lion plinths, a new means of manoeuvring the Stone in and out of the seat compartment had to be found: the only route was from above.

The iron fittings were now pressed into service as lifting devices. Channels were crudely cut into the ends of the Stone so that the links could stand up, rather than hang down, and ropes could be passed through the rings.

The tendency for the unbalanced Stone to rotate was largely mitigated by the links being constrained in channels.

It was a clumsy compromise but it worked, albeit inflicting damage on the gilded interior of the Chair, as the Stone was hauled in and out.

The institutional history of Westminster Abbey in the two decades following its dissolution in 1540 is complex, but remarkably, the shrine of St Edward and the royal tombs survived.

The later 16th century saw a fashion for attaching historical labels (tabulae) to features around the Abbey, including the shrine, tombs and St Edward’s Chair.

These were generally painted either directly on the object or on a board, but in the case of the Chair, it seems that there was initially an intention to insert an inscribed brass plate in the upper face of the Stone.

The rectangular outline for the plate was roughly chiselled. The matrix was never fully cut and the project aborted. A painted label on a board was provided instead.

The change of plan most likely resulted from a decision to fit a timber seat-board over the Stone that had two further consequences.

First, battens had to be fitted to the sides of the Chair to support the seat-board, thereby reducing the size of the Stone compartment opening.

The block had to be shortened, and both ends were cut back by c. 15mm.

Second, the iron rings projected above the top of the Stone, obstructing the fixing of the seat.

To solve this problem, housings were hacked into the top of the Stone, allowing the rings to lie flat.

13th-century survival

Since the late 16th century, travellers and antiquaries have written accounts of the Chair, from which we learn that it suffered casual abuse until Queen Victoria came to the throne.

All the glass inserts were prised out, scores of slices were removed from the frame with pocket-knives and taken as souvenirs, names and initials were liberally carved in the wood, and the shields were stolen from the quatrefoils, exposing the sides of the Stone, which was then scraped with knives to acquire samples of its dust.

Three shallow scoops scored into the front edge result from this activity.

In the 18th century, when the second lion-plinth and new seat-board were fitted, further modifications to both the Chair and Stone occurred.

Although the latter had been shortened, the iron staples to which the rings were attached projected awkwardly, gouging the sides of the Chair every time the Stone was moved.

To ease this, the crowns of the staples were filed down. Something even more barbaric happened between 1727 and 1821: the lower edges of the Stone were broken away with nine hammer-blows.

There is no obvious explanation for this – perhaps the pieces were sold as souvenirs.

Even in more recent times, the Chair has suffered periodically.

In 1887, the Office of Works painted it brown for the celebration of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee.

A public outcry ensued and great damage was done to the gilt decoration when trying to remove the paint.

In 1914, Suffragettes attached a home-made bomb to one of the Chair’s pinnacles, causing more damage.

In 1939-1945, the Chair was stored in the crypt of Gloucester Cathedral, where it narrowly escaped destruction by an infestation of dry rot.

Finally, as well as vandalising the Chair, the gang that stole the Stone in 1950 dropped it and broke it.

Given this long and varied history, it is perhaps remarkable that the Chair survives at all.

Yet our study makes it clear that, despite having fallen victim to neglect, politics and the whims of fashion, St Edward’s Chair and the Stone of Scone – in the form we know it today – are two components of a single artefact, made in the 1290s.

They have an integrated physical history, and shared archaeology: one cannot be understood without the other.

#Coronation Chair#St Edward's Chair#King Edward's Chair#Stone of Scone#Coronation Stone#King Edward I#British History#British Royal Family#Queen Victoria#Queen Elizabeth II#medieval throne#Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria (1887)#Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II (2012)

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐉𝐎𝐋𝐘𝐍𝐄

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the occasion of the coronation of the King of England& what is Stone of Scone.

The legend of the Stone of Destiny goes back to the foundation myth of Scotland. In about 1400BC, an Egyptian Pharaoh had a daughter called Scota, who married Goídel Glas. They were exiled from Egypt and eventuallty settled in north-west Spain. Their descendents later conquered Ireland and became the Scotii, who also in time came to rule Scotland.

I doubt this story because the English stole thousands of Egyptian artifacts and create stories as usual

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are people who seem interested in tying the coronation ceremony to pre-Christian rites. I've seen Francis Young claim that it emerged as a Christian compromise with earlier pagan rites of investiture... without actually describing what those pagan rites were or their relationship to the Christian coronation. One thing that gets brought up though is the so-called Stone of Destiny. I'm guessing that's this thing:

From what I can gather, it's supposed to be an ancient ritual stone that was used by the Scottish monarchy to inaugurate new kings/queens, and was later used for the kings/queens of Britain as a whole. Supposedly, this stone has been in use since the pre-Christian era, but the thing is, no one really knows where it came from or when it first used.

And I'm thinking, has anyone ever actually dated the Stone of Destiny for its origin? Do we know that it was actually part of a series of ancient pre-Christian rites, or is this just a convenient mythology for the British monarchy? But even if it was, it wouldn't make the British coronation rites somehow non-Christian. It would simply be Christian ceremony incorporating pre-existing elements, not unlike what the Catholic Church had already done.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

The specifics of the rock’s creation are unknown. But the Telegraph reports that the stone “is rumored to have biblical connections” and may have been used in Scottish rulers’ coronations more than a century before its first recorded use, in 1057, when Lulach, stepson of Macbeth, was crowned king at Scone Abbey. (The Shakespeare character was based on a real ruler, but the early 17th-century play that bears Macbeth’s name has little in common with his actual life.) During these early coronations, the stone “was believed to roar with joy when it recognized the right monarch,” writes Steven Brocklehurst for BBC News.

#archaeology#british history#charles iii#england#history#macbeth#scone#stone of scone#stone of destiny#lulach#scotland#scottish

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Replica Coronation Throne & Stone of Scone

The Crown

Gold-painted and simulated oak fibre-glass throne faithfully recreated after the Gothic original, the arched panelled back with downswept arms mounted with tan leather, with Gothic arched panelled sides above a solid seat and pierced quatre-foil frieze enclosing a fibreglass copy of the Coronation Stone of Scone (Stone of Destiny), supported by four lions on a plinth base, with red velvet upholstered squab cushions, together with golden canopy used during the filming of the scene, with turned handles, to be held by bearers; and the Art Department design drawing for the Coronation canopy, the chair: 117cm wide x 72cm deep x 211cm high, (46in wide x 28in deep x 83in high) (3)

via: https://www.bonhams.com/auction/29243/lot/20/a-reproduction-of-saint-edwards-chair-the-coronation-chairseason-1-episode-5-smoke-and-mirrors-3/

0 notes

Text

watched "the stone of destiny" today

I am so fucking angry, if you couldn't tell from my reblogs

1 note

·

View note

Note

Makes you think they should have left the stone in Westminster if they broke it within hours of taking it.

Nah, it’s fine now and I think the breakage is now part of its story, part of the long journey to get it back home. Plus it wouldn’t have been broken by a bunch of overly enthusiastic amateur burglars in their 20s if Edward hadn’t taken it in the first place so 🤷🏻♀️

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On November 30th 1996 thousands lined The Royal Mile in Edinburgh to see the Stone of Destiny, stolen from Scone by King Edward I of England in 1296, returned to Scotland and installed in the Castle.

At first, the Stone of Destiny appears to be little more than a simple stone, but no other stone could carry so much history and tradition than this one. Despite its simplicity, it has quite a colourful and surprising history.

The Stone of Destiny goes by many names, sometimes called the Stone of Scone, The Coronation Stone , An Lia Fàil or Jacob’s Pillow. It is a simple block of red sandstone that measures about 26 inches by 17 inches.

Both Scottish, English and British monarchs have been crowned on this stone since the ninth century.

Legend dates back to biblical times; the stone is said to have been the pillow Jacob used, where he dreamed of Jacob’s Ladder. It was seen as a sacred object and first went to Ireland and then to Scotland.

No one can pinpoint exactly where the stone came from, with origin stories mentioning biblical stories or the stone being quarried in Scotland. However, geologists proved that the stone was quarried somewhere around Scone, the historical site of the Scottish Kingdom. There is a theory that the Augustine Monks, learning that an English Army was on it’s way to Perth and fashioned a replica from a block of stone quarried nearby, the real stone was either hidden in the River Tay or Dunsinane Hill, my subject of last weeks post, Nigel Tranter himself believed the object Edward took to London was "a lump of Scone sandstone".

As I mentioned in a previous post today, the last Scottish King to receive his coronation on the stone is John Balliol, who is said to have lost the stone to Edward I “Hammer of the Scots” when he invaded Scotland in 1296 The stone was taken as spoils of war where Edward fitted it to his chair in order to try and secure his role as Lord Paramount of Scotland.

In 1328 England promised to return the stone to Scotland. However, angry English crowds stopped it from actually leaving Westminster Abbey. It remained in England for another six centuries.

The stone was liberated by four nationalist students in 1950, during the theft, they broke the stone into two pieces. Despite this, they managed to bring it back into Scotland when they passed both halves to a senior Glasgow politician; the stone was then repaired by a stonemason.

The government ordered a search for the stone, and the search was unsuccessful. The custodians left the stone in Arbroath Abbey in April 1951. When it was discovered, it was returned to Westminster.

In 1996, the government returned the stone to Scotland. A handover ceremony took place in November 1996 between the Home Office and the Scottish Office. It arrived at Edinburgh Castle to a crowd of around 10,000 people. To this day it sits alongside the crown jewels of Scotland when not used in coronations.

Doubt surrounds the stone all throughout its history, and it is said there are many points in which the stone could have been swapped or lost.

Another belief is that the stonemason who repaired the stone after its damage made several copies and the one returned was, in fact one of his forgeries. The big thing, in my opinion that lets this theory down is would a typical Glesga stonemason take the trouble top venture north to Perth to find a lump of stone?

The true history of the stone and whether or not the one in Edinburgh Castle is the correct stone will never fully be known. I myself tend to believe the story, that the Monks hid the original stone.

The Stone will soon be taken down to Westminster Abbey once more and placed on Edward’s Coronation Chair before being returned to Edinburgh, it will then be moved, eventually to the new Perth City Hall museum, the museum is due to open some time in 2024. The last pic is an artists impression of how it could look.

#Scotland#scottish#England#english#stone of destiny#stone of scone#st andrews day#perth#history#medieval history#theft

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

The new King has to be crowned on a 700 year old wooden chair with a rock underneath it. The rock is something his people stole from other people they used to beat up and eventually conquered. But they gave the stone back awhile ago, only if the other people agreed to let them borrow it any time they need to crown a new king, to put underneath his 700 year old wooden chair. To remind them they were conquered by his ancestors.

And they agreed to this.

No this isn't from a fantasy story this is from THE UK, the place that considers itself (along with America) the leading light of democracy in the world.

And this is what they spend taxpayer money on. Moving a rock so a new hereditary monarch with zero power can metaphorically call 5 and a half million people his bitches.

youtube

And people think the Met Gala is pointless opulent bullshit.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Is the Real Stone of Scone Hidden at Finlaggan?

That’s definitely not the real Stone of Scone above. It’s an ancient standing stone at Finlaggan on the Isle of Islay.

But is the official stone, the one pictured below, the real stone? See BBC article about this stone as it heads south to be used in the latest coronation.

History of the Real Stone of Scone

The Stone of Scone, or Stone of Destiny, was used in the inauguration of Scottish Kings…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

so exited for the scottish wars of independence part 2: electric bogaloo

#I will personally ensure Mary Queen of Scotland and the Isle’s body is safe when we go to steal the#stone of scone

0 notes

Text

Peach Scones

#peach#fruit#scones#food#summer#dessert#stone fruit#recipe#breakfast#tea time#snack#buttermik#thesaltymarshmallow

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

Honestly feeling kinda meh about it but I'm still happy I experimented a bit with the weird lineart

106 notes

·

View notes