#Georgia Sea Islands

Text

Black Residents Of Gullah-Geechee Enclave In Georgia Angered After Zoning Changes Pose Threat To Their Community

This small enclave is home to a majority of Black residents who are members of the Hogg Hummock community, which is also sometimes referred to as Hog Hammock. According to The Cultural Landscape Foundation, “Hog Hammock was one of fifteen African American Saltwater Geechee settlements on Sapelo Island, Georgia.

The Geechee are descendants of enslaved West Africans brought to work on Sea Island plantations along the Atlantic coast.” Sapelo island is located approximately 60 miles south of Savannah, Georgia and is only reachable by boat.

Almost three decades ago, the county adopted the zoning restrictions, “with the stated intent to help Hogg Hummock’s 30 to 50 residents hold on to their land,” the Associated Press reports.

But the McIntosh County’s elected commissioners recently voted 3-2 vote to change the restrictions. Now, Black residents fear that wealthy buyers will be prioritized over them, which could lead to increases in taxes.

Residents also anticipate this could cause them to be pressured to sell their land, most of which has been in their family for generations. Atlanta resident Yolanda Grovner originally had a plan where she would ultimately retire on her island native father’s land that he owns in Hogg Hummock, but now she worries this might not be able to happen. Yolanda’s father George Grovner attended the meeting wearing a sticker, which read “Keep Sapelo Geechee,” in defiance of these planned zoning changes.

“It’s going to be very, very difficult,” said Yolanda, continuing, “I think this is their way of pushing residents off the island.”

In recent years, the population on Hogg Hummock has been shrinking because some families have sold their land to outsiders. David Stevens, Chairman of the Commission, said he’s been a visitor on Sapelo Island since the 1980s, and places the blame for these changes on those who are selling their land.

This could be partly true, as the vote followed new construction builds. The commissioners ruling “raised the maximum size of a home in Hogg Hummock to 3,000 square feet (278 square meters) of total enclosed space. The previous limit was 1,400 square feet (130 square meters) of heated and air-conditioned space,” per the Associated Press.

Stevens stated, “I don’t need anybody to lecture me on the culture of Sapelo Island.” “If you don’t want these outsiders, if you don’t want these new homes being built...don’t sell your land,” Stevens concluded.

But the remaining residents have vowed to keep fighting these ordinance changes, and it’s not a new phenomenon for them to fight with the local government either. In 2012, dozens of residents and landowners were able to successfully appeal property tax increases.

In addition, many have spent years “fighting the county in federal court for basic services such as firefighting equipment and trash collection before county officials settled last year,” writes the Associated Press.

Maurice Bailey is a native of Hogg Hummock whose mother Cornelia Bailey had deep roots to the island. Bailey was a Sapelo Island celebrity, keeping the community’s voice alive with her storytelling before she died in 2017. Maurice said, “We’re still fighting all the time,” adding, “They’re not going to stop. The people moving in don’t respect us as people. They love our food, they love our culture. But they don’t love us.”

Some legal experts have hinted at due process violations as well as concerns about encroachment under the equal protection clause.

This issue becomes more complicated given the racial demographics of the county. Hogg Hummock is on the National Register of Historic Places, and in order for the Gullah-Geechee community to receive protections “to preserve the community, residents depend on the local government in McIntosh County, where 65% of the 11,100 residents are white,” says the Associated Press.

#Black Residents Of Gullah-Geechee Enclave In Georgia Angered After Zoning Changes Pose Threat To Their Community#sapelo#georgia sea islands#Gullah Geechee#Lowlands#Hogg Hummock#Sapelo Island#Gullah Geechee community

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

some photos from the ferry

#west coast#vancouver island#yyj#yyjphotographer#bc#nature#victoria bc#ocean#vancouver#Tsawwassen#sun spots#horizon#sea#island#georgia strait#bc ferries#british columbia#explore bc#pnwexplored#pnwonderland#pnw aesthetic#oceancore

367 notes

·

View notes

Text

A story from a former slave, Mary Middleton, a Gullah woman from the South Carolina Sea Islands, told of an incident of a slaveholder who was physically weakened from conjure. A slaveholder beat one his slaves badly. The slave he beat went to a conjurer and the conjurer made the slaveholder weak by sunset. Middleton said, "As soon as the sun was down, he was down too, he down yet. De witch done dat." Bishop Jamison was born enslaved in Georgia in 1848 and wrote an autobiographical account of his life. On a plantation in Georgia there was an enslaved Hoodoo man named Uncle Charles Hall who prescribed herbs and charms for slaves to protect themselves from European people.

Hall instructed the slaves to anoint roots three times daily and chew and spit roots towards their enslavers for their protection. Another slave story talked about an enslaved woman named Old Julie who was a conjure woman and was known among the slaves on the plantation to conjure death. Old Julie conjured so much death, her slaveholder sold her away to stop her from killing people on the plantation with conjure. Her enslaver put her on a steamboat to take her to her new slaveholder in the Deep South. According to the stories of freedmen after the Civil War, Old Julie used her conjure powers to turn the steamboat around back to where the boat was docked, which forced her slaveholder who tried to sell her away to keep her.

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#afrakans#brown skin#african culture#afrakan spirituality#gullah geechee#gullah gullah island#mary middleton#civil war#old julie#deep south#freedman#south carolina island#sea islands#georgia

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Sea Island Series) Plate 15, 1991-92.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I really need to listen to some more Gullah-Geechee music

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

WHAT DO YOU MEAN THE BOATS LEAKING YALL OKAY??? I DONT WANNA GO TO OUR THINGY ALONE MITHERFUCKER YOU BETTER REMEMBER HOW TO SWIM AND SEE IN THE DARK TO MAKE OT TO LAND /j /lh (for people who might read this there was a wind warning out for tonight so this was probably to be expected)

DAN HOWELL THIS ONES FOR YOU (Swims the entire Georgia Straight)

Also yeah it was like a cooler or fridge or smthn in the kitchen that got rattled around by the waves and started to leak

Either way I would much prefer a leak on the top deck as opposed to the lower decks lmao

#rambles#okay context quickly I’m taking a ferry to see Daniel Howell in Vancouver tomorrow lol#oh and the Georgia straight/Salish sea is the waterway between the island and the mainland here lol#answered asks#jackie-mae#mae#also as if I would forget how to see in the dark 😒 who do you think I am?#personal I suppose

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Made in 2017

If you’ve seen this anywhere else, I posted it back on my deviantArt when it was made.

Mario girls cosplaying as characters from the Pokemon anime

1. Georgia

2. Katie

3. Lisa

4. Mairin

5. Melody

6. Meredith

7. Neesha

8. Sara Lee

9. Shauna

10. Trinity

#pokemon#pokemon anime#nintendo#unova#kalos#mewtwo strikes back#pokemon the first movie#kanto#orange islands#hoenn#johto#Pokémon the Movie 2000#the power of one#pokémon ranger and the temple of the sea#spell of the unown: entei#pokémon 3: the movie#princess daisy#daisy#georgia#katie#lisa#mairin#melody#meredith#neesha#sara lee#shauna#trinity

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#Luxury Resort in Saint Simons Island#homes for sale in south carolina#new homes for sale#sea island golf#the lodge at sea island#the cloister at sea island#homes for sale in bluffton#hilton head real estate#sun city hilton head#bluffton sc real estate#buyers real estate agent#bluffton gated communities#new homes for sale in georgia#bluffton Real Estate#Exploring Sea Island#John Weber#st simon island#Saint Simons Island Georiga#georgia#homes for sale#Youtube

0 notes

Text

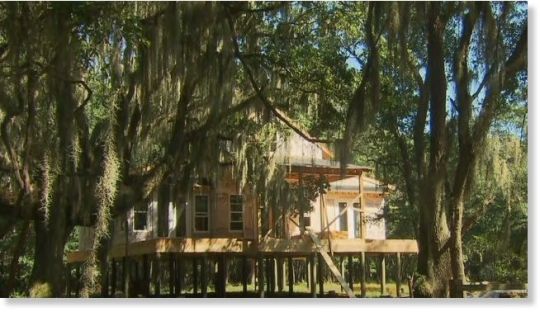

The residence of William Frank McCall, Jr. also known as “The Hedges” in Sea Island, Georgia, 1976.

#Frank McCall#architecture#70s#interior#interiors#interior design#sea island#beach house#home#the hedges#georgia

0 notes

Text

Sea Island Georgia

On the southeastern coast of the Atlantic Ocean, there is a glamorous and luxurious Georgian seaside resort called Sea Island. With world-renowned accommodation and chefs, not to mention the beach club, spa and 3 golf courses, a trip to the island is sure to be colorful and relaxing. But with its many activities for kids, it’s also an ideal year-round family destination. The only resort in the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

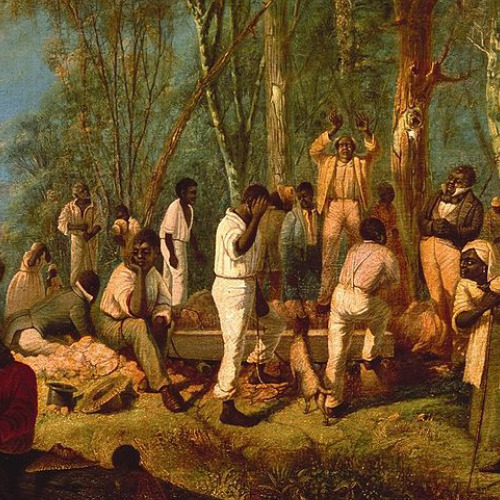

The Gullah and Geechee culture on the Sea Islands of Georgia has retained ethnic traditions from West Africa since the mid-1700s. Although the islands along the southeastern U.S. coast harbor the same collective of West Africans, the name Gullah has come to be the accepted name of the islanders in South Carolina, while Geechee refers to the islanders of Georgia. Modern-day researchers designate the region stretching from Sandy Island, South Carolina, to Amelia Island, Florida, as the Gullah Coast—the locale of the culture that built some of the richest plantations in the South.

Many traditions of the Gullah and Geechee culture were passed from one generation to the next through language, agriculture, and spirituality. The culture has been linked to specific West African ethnic groups who were enslaved on island plantations to grow rice, indigo, and cotton starting in 1750, when antislavery laws ended in the Georgia colony.

Enslavement

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Rice plantations fostered Georgia’s successful economic competition with other slave-based rice economies along the Eastern Seaboard. Coastal plantations invested primarily in rice, and plantation owners sought out Africans from the Windward Coast of West Africa (Senegambia [later Senegal and the Gambia], Sierra Leone, and Liberia), where rice, indigo, and cotton were indigenous to the region. Over the ensuing centuries, the isolation of the rice-growing ethnic groups, who re-created their native cultures and traditions on the coastal Sea Islands, led to the formation of an identity recognized as Geechee/Gullah.

There is no single West African contribution to Geechee/Gullah culture, although dominant cultural patterns often correspond to various agricultural investments. For example, Africa’s Windward Coast was later commonly referred to as the Rice Coast in recognition of the large numbers of Africans enslaved from that area who worked on rice plantations in America.

Language

Photograph by WIDTTF

Gullah is thought to be a shortened form of Angola, the name of the group first imported to the Carolinas during the early colonial period. Geechee, historically considered a negative word identifying Sea Islanders, became an acceptable term in light of contemporary evidence linking it to West Africa. Although the origins of the two words are not definitive, some enslaved Africans along the coast had names that were linked to the Kissi group, leading to speculation that the terms may also derive from that particular culture.

Linguist Lorenzo Dow Turner researched and documented spoken words on the coast during the 1930s, traced similarities to ethnic groups in West Africa, then published the Gullah dialect lexicon, Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect (1949). His research confirms the evolution of a new language based on West African influences and English. Many words in the coastal culture could be matched to ethnic groups in West Africa, thereby linking the Geechee/Gullah people to their origins. Margaret Washington Creel in A Peculiar People: Slave Religion and Community-Culture among the Gullahs (1988) identifies cultural and spiritual habits that relate to similar ethnic groups of West Africans who are linked by language. Her research on the coastal culture complements Turner’s findings that Africans on the Sea Islands created a new identity despite the tragic conditions of slavery.

Cultural Heritage

Documentation of the developing culture on the Georgia islands dates to the nineteenth century. By the late twentieth century, researchers and scholars had confirmed a distinctive group and identified specific commonalities with locations in West Africa. The rice growers’ cultural retention has been studied through language, cultural habits, and spirituality. The research of Mary A. Twining and Keith E. Baird in Sea Island Roots: African Presence in the Carolinas and Georgia (1991) investigates the common links of islanders to specific West African ethnicities.

The enslaved rice growers from West Africa brought with them knowledge of how to make tools needed for rice harvesting, including fanner baskets for winnowing rice. The sweetgrass baskets found on the coastal islands were made in the same styles as baskets found in the rice culture of West Africa. Sweetgrass baskets also were used for carrying laundry and storing food or firewood. Few present-day members of the Geechee/Gullah culture remember how to select palmetto, sweetgrass, and pine straw to create baskets, and the remaining weavers now make baskets as decorative art, primarily for tourists.

Image from Richard N Horne

Photograph by Sharon Maybarduk

In 1997 the two women met in the African village to share and reenact what was understood as a Mende funeral song, sung only by the women of Jabati’s family lineage, who conducted the funerals of the village. Evidence suggests that a female member of Moran’s family had been forced into captivity from the village nearly 200 years before. The return of the song and the visit from the Moran family led to a countrywide celebration that can be viewed in the documentary The Language You Cry In (1998). The discovery of the song and subsequent linguistic research confirmed yet another link between the cultures of West Africa and the Georgia coast.

Such corresponding practices as similar names, language structures, folktales, kinship patterns, and spiritual transference are but a few areas that suggest a particular link between the southeastern coastal culture of the United States and Sierra Leone in West Africa.

Migration

Thousands of enslaved laborers from Georgia and South Carolina who remained loyal to the British at the end of the American Revolution (1775-83) found safe haven in Nova Scotia in Canada and thus gained their freedom. Many returned to Sierra Leone in 1791 and the following year established Freetown, the capital city. Members of that group are identified today as Krio.

Fugitives from slavery were also harbored under Spanish protection in Florida prior to the Second Seminole War (1835-42). Native American refugees from around the South formed an alliance with self-emancipated Africans to create the Seminole Nation. The name Seminole is from the Spanish word cimarrón, meaning runaway. The 1842 agreement between the United States and Spain, which ended the Seminole hold on Florida, caused a migration to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Some Seminoles followed Spanish protectors to Cuba and to Andros Island in the Bahamas.

Photograph by Jennifer Cruse Sanders

During the 1900s, land on some of the islands—Cumberland, Jekyll, Ossabaw, Sapelo, and St. Simons —became resort locations and reserves for natural resources. The modern-day conflict over resort development on the islands presents yet another survival test for the Geechee/Gullah culture, the most intact West African culture in the United States. Efforts to educate the public by surviving members of the Geechee/Gullah community, including Cornelia Bailey of Sapelo Island and the Georgia Sea Island Singers, help to maintain and protect the culture’s unique heritage in the face of such challenges.

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Across the Strait of Georgia

Across the Strait of Georgia

When you visit the Surf Lodge Pub on Gabriola Island, you will be amazed by the massive size and beauty of the wooden joists and beams that support the roof above you.

When you leave the Surf Lodge Pub on Gabriola Island, you will be in awe of the view of the Strait of Georgia that greets you. In the distance are pastel suggestions of the mainland, and in between there and you is the deceptively…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

My mom wanting to help me make prompts for my blog. She has no clue what I do on my blog but is enthusiastic and wants to encourage my creativity. She’s a bit confused on what writing prompts are but she has the spirit. I need you all to let my mom know how wonderful her ideas are:

- “the pink cat screamed out loud” “the fox skipped through the orchard and came across the pink cat.”

- “The wind whipped through her hair on the top level of the ferry that took them to spookatron island”

- She looked down at the sea and saw the Georgia’s cliffs and crashing waves below her. At least a thousand feet below

- She yelled for the life preserver as the cliffs fell away from her feet.

- The undulating sea roiled against her face, flattening for decades.

- She lept over the bridge with no concern in mind, lunging to grab the flailing glove.

- Loose helmets and no goggles, plus three mopeds equals = help me in crying.

- The sky was painting in gorgeous colors but oh no! There’s something in the sky. What is it?

Also

My mother: “do you get paid for your work?”

Me: “ i mean I have a Ko-Fi? There’s legal issues with getting money from licensed products”

My mother: “You still should get paid.”

#bones prompts#behold my lovely mother. not at all really knowing what a writing prompt is#i love her dearly

411 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irish seaman and Antarctic explorer Thomas Crean photographed in 1915 aboard the Endurance in Antarctica during the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917 led by Ernest Shackleton.

The Endurance was trapped in ice for 492 days and sank, so the 28-man crew had to use lifeboats to reach the uninhabited Elephant Island. Crean was one of 6 members of the crew to make the 800 miles (1300 km) journey from Elephant Island to South Georgia in the small-boat James Caird to seek rescue for the rest of the crew. Once they reached South Georgia after 17 days at sea, 3 of the men, including Tom Crean, trekked across the island to a whaling station on the north side of South Georgia. There they were able to organize rescue efforts for the 3 men left on the south of the island and the remaining crew on Elephant Island. The entire crew of the Endurance returned home without loss of life.

Credit: polar_history_in_colour on Instagram

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading list for Afro-Herbalism:

A Healing Grove: African Tree Remedies and Rituals for the Body and Spirit by Stephanie Rose Bird

Affrilachia: Poems by Frank X Walker

African American Medicine in Washington, D.C.: Healing the Capital During the Civil War Era by Heather Butts

African American Midwifery in the South: Dialogues of Birth, Race, and Memory by Gertrude Jacinta Fraser

African American Slave Medicine: Herbal and Non-Herbal Treatments by Herbert Covey

African Ethnobotany in the Americas edited by Robert Voeks and John Rashford

Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect by Lorenzo Dow Turner

Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples by Jack Forbes

African Medicine: A Complete Guide to Yoruba Healing Science and African Herbal Remedies by Dr. Tariq M. Sawandi, PhD

Afro-Vegan: Farm-Fresh, African, Caribbean, and Southern Flavors Remixed by Bryant Terry

Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” by Zora Neale Hurston

Big Mama’s Back in the Kitchen by Charlene Johnson

Big Mama’s Old Black Pot by Ethel Dixon

Black Belief: Folk Beliefs of Blacks in America and West Africa by Henry H. Mitchell

Black Diamonds, Vol. 1 No. 1 and Vol. 1 Nos. 2–3 edited by Edward J. Cabbell

Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors by Carolyn Finney

Black Food Geographies: Race, Self-Reliance, and Food Access in Washington, D.C. by Ashanté M. Reese

Black Indian Slave Narratives edited by Patrick Minges

Black Magic: Religion and the African American Conjuring Tradition by Yvonne P. Chireau

Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry edited by Camille T. Dungy

Blacks in Appalachia edited by William Turner and Edward J. Cabbell

Caribbean Vegan: Meat-Free, Egg-Free, Dairy-Free Authentic Island Cuisine for Every Occasion by Taymer Mason

Dreams of Africa in Alabama: The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Story of the Last Africans Brought to America by Sylviane Diouf

Faith, Health, and Healing in African American Life by Emilie Townes and Stephanie Y. Mitchem

Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land by Leah Penniman

Folk Wisdom and Mother Wit: John Lee – An African American Herbal Healer by John Lee and Arvilla Payne-Jackson

Four Seasons of Mojo: An Herbal Guide to Natural Living by Stephanie Rose Bird

Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement by Monica White

Fruits of the Harvest: Recipes to Celebrate Kwanzaa and Other Holidays by Eric Copage

George Washington Carver by Tonya Bolden

George Washington Carver: In His Own Words edited by Gary Kremer

God, Dr. Buzzard, and the Bolito Man: A Saltwater Geechee Talks About Life on Sapelo Island, Georgia by Cornelia Bailey

Gone Home: Race and Roots through Appalachia by Karida Brown

Ethno-Botany of the Black Americans by William Ed Grime

Gullah Cuisine: By Land and by Sea by Charlotte Jenkins and William Baldwin

Gullah Culture in America by Emory Shaw Campbell and Wilbur Cross

Gullah/Geechee: Africa’s Seeds in the Winds of the Diaspora-St. Helena’s Serenity by Queen Quet Marquetta Goodwine

High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America by Jessica Harris and Maya Angelou

Homecoming: The Story of African-American Farmers by Charlene Gilbert

Hoodoo Medicine: Gullah Herbal Remedies by Faith Mitchell

Jambalaya: The Natural Woman’s Book of Personal Charms and Practical Rituals by Luisah Teish

Just Medicine: A Cure for Racial Inequality in American Health Care by Dayna Bowen Matthew

Leaves of Green: A Handbook of Herbal Remedies by Maude E. Scott

Like a Weaving: References and Resources on Black Appalachians by Edward J. Cabbell

Listen to Me Good: The Story of an Alabama Midwife by Margaret Charles Smith and Linda Janet Holmes

Making Gullah: A History of Sapelo Islanders, Race, and the American Imagination by Melissa Cooper

Mandy’s Favorite Louisiana Recipes by Natalie V. Scott

Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present by Harriet Washington

Mojo Workin’: The Old African American Hoodoo System by Katrina Hazzard-Donald

Motherwit: An Alabama Midwife’s Story by Onnie Lee Logan as told to Katherine Clark

My Bag Was Always Packed: The Life and Times of a Virginia Midwife by Claudine Curry Smith and Mildred Hopkins Baker Roberson

My Face Is Black Is True: Callie House and the Struggle for Ex-Slave Reparations by Mary Frances Berry

My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies by Resmaa Menakem

On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker by A'Lelia Bundles

Papa Jim’s Herbal Magic Workbook by Papa Jim

Places for the Spirit: Traditional African American Gardens by Vaughn Sills (Photographer), Hilton Als (Foreword), Lowry Pei (Introduction)

Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome by Dr. Joy DeGruy

Rooted in the Earth: Reclaiming the African American Environmental Heritage by Diane Glave

Rufus Estes’ Good Things to Eat: The First Cookbook by an African-American Chef by Rufus Estes

Secret Doctors: Ethnomedicine of African Americans by Wonda Fontenot

Sex, Sickness, and Slavery: Illness in the Antebellum South by Marli Weiner with Mayzie Hough

Slavery’s Exiles: The Story of the American Maroons by Sylviane Diouf

Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time by Adrian Miller

Spirituality and the Black Helping Tradition in Social Work by Elmer P. Martin Jr. and Joanne Mitchell Martin

Sticks, Stones, Roots & Bones: Hoodoo, Mojo & Conjuring with Herbs by Stephanie Rose Bird

The African-American Heritage Cookbook: Traditional Recipes and Fond Remembrances from Alabama’s Renowned Tuskegee Institute by Carolyn Quick Tillery

The Black Family Reunion Cookbook (Recipes and Food Memories from the National Council of Negro Women) edited by Libby Clark

The Conjure Woman and Other Conjure Tales by Charles Chesnutt

The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature by J. Drew Lanham

The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks by Toni Tipton-Martin

The President’s Kitchen Cabinet: The Story of the African Americans Who Have Fed Our First Families, from the Washingtons to the Obamas by Adrian Miller

The Taste of Country Cooking: The 30th Anniversary Edition of a Great Classic Southern Cookbook by Edna Lewis

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: An Insiders’ Account of the Shocking Medical Experiment Conducted by Government Doctors Against African American Men by Fred D. Gray

Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape by Lauret E. Savoy

Vegan Soul Kitchen: Fresh, Healthy, and Creative African-American Cuisine by Bryant Terry

Vibration Cooking: Or, The Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl by Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor

Voodoo and Hoodoo: The Craft as Revealed by Traditional Practitioners by Jim Haskins

When Roots Die: Endangered Traditions on the Sea Islands by Patricia Jones-Jackson

Working Conjure: A Guide to Hoodoo Folk Magic by Hoodoo Sen Moise

Working the Roots: Over 400 Years of Traditional African American Healing by Michelle Lee

Wurkn Dem Rootz: Ancestral Hoodoo by Medicine Man

Zora Neale Hurston: Folklore, Memoirs, and Other Writings: Mules and Men, Tell My Horse, Dust Tracks on a Road, Selected Articles by Zora Neale Hurston

The Ways of Herbalism in the African World with Olatokunboh Obasi MSc, RH (webinar via The American Herbalists Guild)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Special Field Orders, No. 15 (series 1865) were military orders issued during the American Civil War, on January 16, 1865, by General William Tecumseh Sherman, commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi of the United States Army. They provided for the confiscation of 400,000 acres (160,000 ha) of land along the Atlantic coast of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida and the dividing of it into parcels of not more than 40 acres (16 ha), on which were to be settled approximately 18,000 formerly enslaved families and other black people then living in the area.

The orders were issued following Sherman's March to the Sea. They were intended to address the immediate problem of dealing with the tens of thousands of black refugees who had joined Sherman's march in search of protection and sustenance, and “to assure the harmony of action in the area of operations.” Critics allege that his intention was for the order to be a temporary measure to address an immediate problem, and not to grant permanent ownership of the land to the freedmen, although most of the recipients assumed otherwise. General Sherman issued his orders four days after meeting with twenty local black ministers and lay leaders and with U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton in Savannah, Georgia. Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton, an abolitionist from Massachusetts who had previously organized the recruitment of black soldiers for the Union Army, was put in charge of implementing the orders. Freedmen were settled in Georgia, particularly along the Savannah River, in the Ogeechee district of Chatham County, and on islands off of the coast of Savannah.

In the end, the orders had little concrete effect because President Andrew Johnson issued a proclamation that returned the lands to southern owners who took a loyalty oath. Johnson granted amnesty to most former Confederates and allowed the rebel states to elect new governments. These governments, which often included ex-Confederate officials, soon enacted black codes, measures designed to control and repress the recently freed slave population. General Saxton and his staff at the Charleston SC Freedmen Bureau's office refused to carry out President Johnson's wishes and denied all applications to have lands returned. In the end, Johnson and his allies removed General Saxton and his staff, but not before Congress was able to provide legislation to assist some families in keeping their lands.

Although mules are not mentioned in the orders, they were a main source for the expression “forty acres and a mule.” A historical marker commemorating the order was erected by the Georgia Historical Society in Savannah, near the corner of Harris and Bull streets, in Madison Square. (source)

👉🏿 40 Acres & A Lie (podcast)

#politics#slavery#reparations#black history#juneteenth#racism#40 acres and a mule#special field order 15#american history#civil war#reconstruction#40 acres and a lie#black codes

57 notes

·

View notes