#Huron University College at Western

Text

instagram

Adrienne Arsenault always is an inspiration!

Source: CBC's Instagram Page

#Adrienne Arsenault#Huron University College at Western#Huron University College#Huron University#London#Ontario#ON#Canada#Favorite Torontonian#Favorite Ontarian#Favorite Canadian#Favorite Human#Canadian Instagram#Canada Chronicles#Instagram

0 notes

Text

God Speaks to Each of Us in Our Own Love Language

The poignance of human longing, existential angst, and the intimacy of God with us

Photo credit to Carolyn Weber: author, speaker and professor

Carolyn Weber has always been an academic, but she is no longer an atheist. She has a B.A. Hon. from Huron College at Western University, Canada and a M.Phil. and D.Phil. from Oxford University, England. She has taught at faculty at Oxford University, Seattle University, University of San Francisco, Westmont College, Brescia University…

View On WordPress

#Bible#Carolyn Weber#Ecclesiastes#existential angst#God is love#intimacy#Jana Harman#longing#Shakespeare#Side B Stories

0 notes

Photo

#reading room#university#college#peaceful#cozy#sunset#Huron University College#Western University#UWO#Canada#Ontario#student#study#photography#original#silence

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lake Michigan, Chicago (No. 2)

Some of the earliest human inhabitants of the Lake Michigan region were the Hopewell Indians. Their culture declined after 800 AD, and for the next few hundred years, the region was the home of peoples known as the Late Woodland Indians. In the early 17th century, when western European explorers made their first forays into the region, they encountered descendants of the Late Woodland Indians: the Chippewa; Menominee; Sauk; Fox; Winnebago; Miami; Ottawa; and Potawatomi. The French explorer Jean Nicolet is believed to have been the first European to reach Lake Michigan, possibly in 1634 or 1638. In the earliest European maps of the region, the name of Lake Illinois has been found in addition to that of "Michigan", named for the Illinois Confederation of tribes.

Lake Michigan is joined via the narrow, open-water Straits of Mackinac with Lake Huron, and the combined body of water is sometimes called Michigan–Huron (also Huron–Michigan). The Straits of Mackinac were an important Native American and fur trade route. Located on the southern side of the Straits is the town of Mackinaw City, Michigan, the site of Fort Michilimackinac, a reconstructed French fort founded in 1715, and on the northern side is St. Ignace, Michigan, site of a French Catholic mission to the Indians, founded in 1671. In 1673, Jacques Marquette, Louis Joliet and their crew of five Métis voyageurs followed Lake Michigan to Green Bay and up the Fox River, nearly to its headwaters, in their search for the Mississippi River, cf. Fox–Wisconsin Waterway. The eastern end of the Straits was controlled by Fort Mackinac on Mackinac Island, a British colonial and early American military base and fur trade center, founded in 1781.

With the advent of European exploration into the area in the late 17th century, Lake Michigan became part of a line of waterways leading from the Saint Lawrence River to the Mississippi River and thence to the Gulf of Mexico. French coureurs des bois and voyageurs established small ports and trading communities, such as Green Bay, on the lake during the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

In the 19th century, Lake Michigan played a major role in the development of Chicago and the Midwestern United States west of the lake. For example, 90% of the grain shipped from Chicago travelled east over Lake Michigan during the antebellum years, and only rarely falling below 50% after the Civil War and the major expansion of railroad shipping.

The first person to reach the deep bottom of Lake Michigan was J. Val Klump, a scientist at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. Klump reached the bottom via submersible as part of a 1985 research expedition.

In 2007, a row of stones paralleling an ancient shoreline was discovered by Mark Holley, professor of underwater archeology at Northwestern Michigan College. This formation lies 40 feet (12 m) below the surface of the lake. One of the stones is said to have a carving resembling a mastodon. So far the formation has not been authenticated.

The warming of Lake Michigan was the subject of a report by Purdue University in 2018. In each decade since 1980, steady increases in obscure surface temperature have occurred. This is likely to lead to decreasing native habitat and to adversely affect native species survival.

Source: Wikipedia

#Lake Michigan#Lake Michigan Trail#Chicago Lakefront Trail#Chicago#USA#marina#water#nature#cityscape#original photography#summer 2019#Illinois#travel#vacation#skyline#Shedd Aquarium#architecture#night shot#reflection#evening light#landmark#tourist attraction#Great Lakes Region#Midwestern USA#Windy City#illuminated#Chitown

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Real Michigan MAC Trophy

Hello friends, we’re back to round out the hypothetical histories of the real life three-way rivalry trophies. Before we begin, if you’d like to check out my previous posts on the Florida Cup, Commander-in-Chief’s Trophy, or the Beehive Boot, click the links provided.

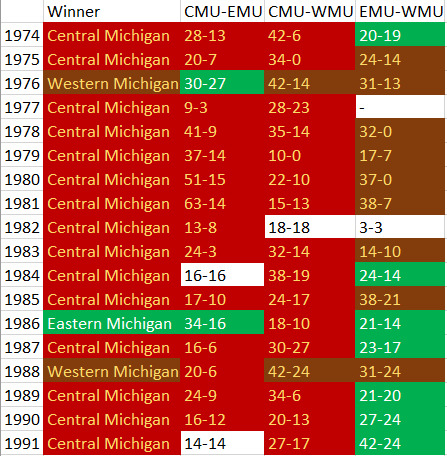

You probably saw this one coming, today’s the day for the Michigan MAC Trophy. What the name lacks in imagination it makes up for in specificity. The Michigan MAC Trophy is handed out every year to the head-to-head winner between Central Michigan, Eastern Michigan, and Western Michigan.

It’s a relatively new trophy, and has only been given out since 2005. But what if we wind the clock back to the beginning of the three-way rivalry, how would things be different?

The rules of the Michigan MAC Trophy are the same as the ones governing the Service Academies. The winner will retain possession of the trophy until another team claims it. In the event of a three-way tiebreaker, where all teams hold a 1-1 record against each other, the Trophy remains where it is.

So let’s jump in our time machines and head back to the beginning.

-

The proper year to begin giving out the Michigan MAC Trophy has to be 1974, the year all three schools began to play each other on an annual basis. There had been a handful of years when this had happened before, in 1907 and in the late 20′s, but for the most part Eastern and Western Michigan had nothing to do with each other.

For the first three-quarters of the 20th Century, WMU and CMU would play on a near-annual basis, as would CMU and EMU, but there was little to no overlap between the Eagles and the Broncos.

This makes more sense when you remember the conference situation. The MAC was founded all the way back in 1946, making it by far the oldest of the G5 conferences, predating the FBS designation by decades in fact. However, Western Michigan was the only school from the state in the conference for decades. The Broncos had middling success in the league, and were mostly overshadowed by higher powered opponents like Miami of Ohio.

Central and Eastern Michigan spent this time in lower divisions. It wasn’t until 1971 that those universities joined the MAC, but it took even longer for their football teams to get all of their ducks in a row to move up to D-I. CMU football officially joined the Mid-American in 1975, and EMU followed the year after.

However, it was in 1974, just before both schools joined the MAC, that EMU and WMU finally began playing yearly to close the loop and begin the three-way rivalry.

CMU Leads the Pack: 1974-1991

It was the perfect time to move up if you were a Central Michigan fan. The Chippewas won the Division II National Championship in the 1974 season. Central Michigan had been led by head coach Roy Kramer since 1967. It was Kramer who built Central Michigan into a D-II powerhouse and perfectly timed their jump. In their first three years in the MAC, CMU went 25-7-1. They didn’t claim any conference titles, but finished 2nd in 1975 and 1977.

Roy Kramer was replaced by longtime replacement Herb Deromedi in 1978. Central Michigan went from strength to strength, as Deromedi proved to be the perfect match. CMU finished ‘78 with a 9-2 record, finishing 2nd in the MAC once again. The next two years, the Chippewas would win the conference. In 1979, Central Michigan went undefeated with a 10-0-1 record. They didn’t play in a bowl or finish in the AP Poll because that’s just how things were back then.

CMU wouldn’t win the MAC again for another decade, but they were a player in the conference race every year and completely dominated their rivals. The Chippewas wouldn’t suffer a losing season through the entirety of Deromedi’s 16 year tenure.

The 1980′s weren’t as successful in Kalamazoo or Ypsilanti, but neither team was a real bottom-feeder.

Western Michigan likely assumed they’d be able to run roughshod over their newcomer brother programs, but were usurped. 1974 was the final year in Bill Doolittle’s decade long tenure, and the largely successful WMU coach faceplanted with a 3-8 record after seven winning seasons in his previous nine years.

Doolittle’s replacement was Elliot Uzelac (who would later coach Navy in the late 80′s). Uzelac did a good job for the most part. After a dreadful 1-10 first season, he coached the Broncos to a 37-29 record from 1976 to 1981. Jack Harbaugh coached Western Michigan from 1982 to 1986, but after a 2nd place finish in his first year WMU got worse each year.

Al Molde came in to take over from Harbaugh in 1987. Molde had coached his way up from D-III and quickly got the Broncos straightened out. In 1988, Western Michigan went 9-3, winning their first MAC title since 1966 but lost to Fresno State in the California Bowl. WMU remained a contender for the rest of Molde’s decade in Kalamazoo, finishing above .500 for the next six seasons.

Eastern Michigan hadn’t been a very successful D-II program, so hopes weren’t exactly high as they transitioned to the higher level. Ed Chlebek actually managed a surprise 8-3 record in 1977, but then left immediately for Boston College. Replacement Mike Stock was horrible, and he was fired only 3 games into the 1982 season after accruing a 6-38-1 record.

EMU hired Jim Harkema in 1983. Harkema was previously the head man at Grand Valley State in D-II and had led the Lakers to three conference titles in his ten years at the helm. Harkema would spend another ten years in Ypsilanti and would become the Hurons’ best coach since moving up to D-I.

It took some time to get things going, but by year 1986 Eastern Michigan had a winning record. In ‘87, EMU had their best year in modern history, going 10-2, earning their first every (and currently only) MAC Championship and a victory over San Jose State in the California Bowl. The Hurons finished with a winning record in the next two years, finishing 2nd in the MAC both times.

The magic didn’t last, and Harkema resigned midway through the 1992 season after several losing campaigns. The Hurons, now renamed the Eagles, would enter a brutal period of decline after this point.

Michigan MAC Trophy Record

Central Michigan: 15

Western Michigan: 2

Eastern Michigan: 1

Despite the relative parity between the programs, the Trophy was nearly always in Mount Pleasant. Central Michigan owned their rivals in the first two decades since they joined the MAC. The Chippewas would have won the Michigan MAC Trophy in the first 15 of 18 seasons since 1974. They never lost it for more than a year and never once kept it via tiebreaker.

It’s curious how dominant this stretch was considering that both Western and Eastern Michigan had periods of success, especially in the late 80′s. CMU still managed to outfox their rivals on almost every occasion. EMU didn’t manage to win the Trophy in 1987, their only 10 win season ever, because one of their two losses was to Central.

The Broncos only managed to win the Trophy twice. The first, in 1976 was during a down year for the Chippewas, and the second was WMU’s first 9 win season in program history.

-

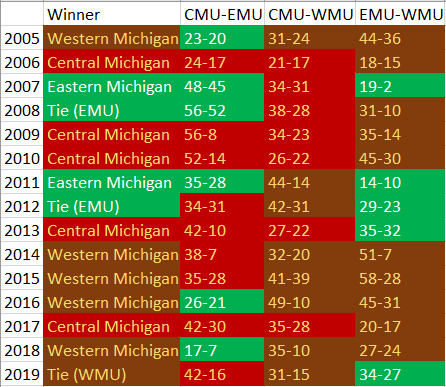

Western Michigan Strikes Back: 1992-2004

Jim Harkema and Herb Deromedi retired in 1992 and 1993 respectively. Harkema has been Eastern Michigan’s best coach since moving up to D-I. Deromedi was the MAC’s winningest head coach of all time before Frank Solich passed him last season.

Neither team was able to easily transition away from their best head coaches in recent memory. EMU was hit particularly hard. The Eagles went into a tailspin and would only have one winning season (6-5 in 1995) for the next two decades. CMU won the MAC in Dick Flynn’s first year as head coach in 1994, but then fell off into irrelevance for the next decade.

Western Michigan took charge of the rivalry. WMU remained strong under Al Molde, who stayed on as head coach until his retirement in 1996. Molde’s replacement, Gary Darnell, kept up the momentum at first. The Broncos went 31-15 in Darnell’s first four seasons with two MAC West Division titles.

Western Michigan began to flag around the turn of the decade. The Broncos were a dreadful 15-31 from 2001-2004, a perfectly horrific turnaround compared to the first half of Darnell’s tenure. Darnell was fired after a 1-10 collapse in ‘04.

Michigan MAC Trophy Record

Central Michigan: 18

Western Michigan: 11

Eastern Michigan: 2

Western Michigan was easily the strongest of the Michigan MAC programs in the 1990′s. From Al Molde to Gary Darnell, the Broncos routinely bested their rivals, especially Eastern Michigan.

Central Michigan was able to keep up with their rivals in the mid-90′s, but the Chippewas really fell off under Mike DeBord in the early 2000′s. Eastern Michigan was an afterthought for the most part, though they did manage to win one Trophy in 2004 when all three programs were in the toilet.

-

The Real Trophy Era: 2005-2019

So now we’re back to the beginning. In 2005 the *real* Michigan MAC Trophy began to pass between the three schools in that state in that conference. It was also somewhat of a turning point once more.

In 2004 Brian Kelly came to Central Michigan, reversing the fortunes of the Chippewas, who had been struggling for most of the previous decade. In 2006, CMU went 10-4 with a MAC Championship, which Kelly relayed into a job at Cincinnati. Central Michigan replaced Kelly with another ace hire in Butch Jones, who kept up the winning ways.

CMU won a second straight MAC title in 2007 and a third in 2009. The ‘09 season was a standout 12-2 campaign that saw the Chippewas finish 23rd in the AP Poll, their only final top 25 ranking. Following this extremely successful year, Jones was also poached by Cincinnati following Kelly’s departure to Notre Dame. Central Michigan became a middling program in the MAC West under first Dan Enos and then John Bonamego. Jim McElwain was hired to coach CMU starting in 2019 and went 8-6 in his first year.

Bill Cubit was hired by Western Michigan in 2005 and did a solid job for most of his 8 years in Kalamazoo. Cubit took the Broncos to three bowls, more than WMU had ever seen in total before that point. However, Cubit never was able to take the next step, and following a disappointing 4-8 season in 2012 Cubit was relieved of duty.

Cubit was replaced by PJ Fleck, who quickly transformed Western Michigan into the top program in the MAC. In 2016, the Broncos screamed out to finish the season 13-0 with a MAC Championship and the conference’s second ever berth in a NY6 Bowl. The dream ended in Dallas as #12 WMU lost to Wisconsin in the Cotton Bowl, but it was still the best ever season any Michigan MAC school has ever had. Fleck left following his triumphant ‘16 season. Tim Lester hasn’t done quite as good a job, but has kept Western Michigan relevant in the years since the breakout 2016 season.

Eastern Michigan was a different story. The Eagles were one of the worst teams in FBS football for most of the 2000′s. EMU was a bottom-feeder under Jeff Woodruff, Jeff Genck, and Ron English. They were considered a lost cause when they hired Chris Crieghton.

Creighton was a turnaround veteran, having clawed his way up from NAIA to D-III to non-scholarship FCS. It took a few years, but he even turned around Eastern Michigan. In 2016 the Eagles finished the year 7-6, their first winning season since 1995, and their first bowl since 1987. EMU went bowling in 2018 and 2019 as well.

Michigan MAC Trophy Record

Central Michigan: 23

Western Michigan: 17

Eastern Michigan: 6

Since the introduction of the real rivalry trophy, the standings have been much more competitive. Despite mostly being godawful in the 2000′s, Eastern Michigan somehow managed to keep (and retain) the trophy on four occasions.

Despite good seasons, WMU was unable to claim the trophy often during Bill Cubit’s tenure, but have done well for themselves since PJ Fleck came into town. The Broncos have won five of the last six Trophies. CMU remains a constant in the discussion, though they’ve only won five Trophies since the introduction of the real thing.

-

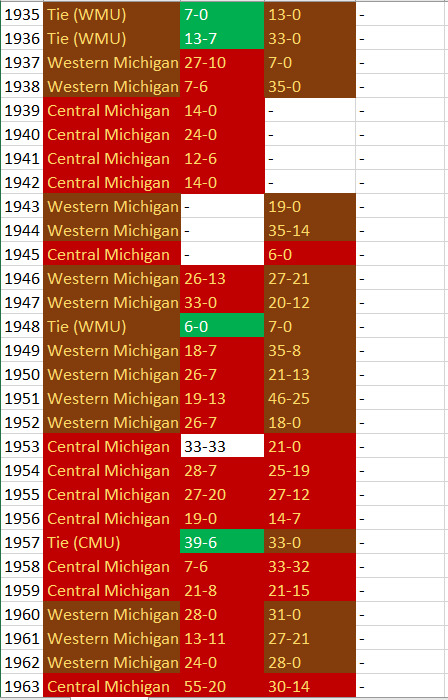

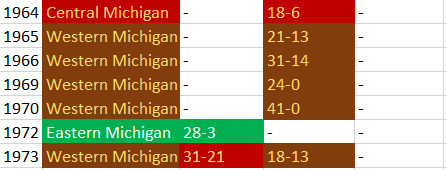

Prehistory: 1902-1973

I’m putting the other games on here just in case you were curious to see the full history of all three games.

Michigan MAC Trophy Record

Western Michigan: 49

Central Michigan: 42

Eastern Michigan: 19

As you can tell this isn’t quite a fair comparison. There were decades separating EMU-WMU games so for the most part the Michigan MAC Trophy would have been simply decided by the CMU-WMU game.

The Broncos definitely dominated the series before 1974, but this is to be expected when they were the only D-I program of the three for several decades.

Michigan MAC Trophy Record (Without Ties)

Central Michigan: 40

Western Michigan: 38

Eastern Michigan: 14

Without ties, Central Michigan regains its lead in the all-time standings. The Chippewas’ complete dominance in the 70′s and 80′s came without a single tie, giving them a slight edge over rival Western Michigan who benefited from 11 ties in the history of the series. The Eagles remain at the bottom. Can’t be helped.

-

I think it’s great that these smaller FBS teams have these interesting and unique rivalries and a Trophy series like this. I hope they continue to do it until the sun burns out. The MAC is one of those underfunded and low-resource conferences that soldiers on as the second choice underneath the Big Ten, providing real college football to the Midwest.

I’m cautiously optimistic about the future of the Michigan MAC Trophy. Obviously it’s got a stronger foundation than either the Beehive Boot or the Florida Cup, since every team actually plays each other every season. The only danger I can imagine is that one or more of these schools eventually drops down a level or drops football altogether for budget reasons. Lets hope it doesn’t happen.

-

Thanks for reading! I hope you enjoyed this little series of mine. Maybe I’ll do a few more exploring other rivalries that don’t have a trophy. Stay tuned!

-cfbguy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ralph W. Larkin, The Columbine Legacy Rampage Shootings as Political Acts, Am Behavioral Specialist (2009)

The purpose of this article is to explore how the Columbine shootings on April 20, 1999, influenced subsequent school rampage shootings. First, school rampage shootings are defined to distinguish them from other forms of school violence. Second, post-Columbine shootings and thwarted shootings are examined to determine how they were influenced by Columbine. Unlike prior rampage shooters, Harris and Klebold committed their rampage shooting as an overtly political act in the name of oppressed students victimized by their peers. Numerous post-Columbine rampage shooters referred directly to Columbine as their inspiration; others attempted to supersede the Columbine shootings in body count. In the wake of Columbine, conspiracies to blow up schools and kill their inhabitants by outcast students were uncovered by authorities. School rampage shootings, most of which referred back to Columbine as their inspiration, expanded beyond North America to Europe, Australia, and Argentina; they increased on college campuses and spread to nonschool venues. The Columbine shootings redefined such acts not merely as revenge but as a means of protest of bullying, intimidation, social isolation, and public rituals of humiliation.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Americans witnessed a new and disturbing social phenomenon: school rampage shootings executed by disturbed and alienated present or former male students who had decided to settle grudges against peers, teachers, or administrators with bullets and sometimes bombs. Such shootings seemed to culminate with the Columbine High School massacre on April 20, 1999, which had a toll of 15 dead and 23 wounded. Although school rampages have abated somewhat, numerous serious conspiracies have been uncovered. Rampage shooters have chosen other venues, such as shopping malls and churches. In addition, rampage shootings have spread from North America to the Western world and from secondary schools to university campuses. In this article, evidence will be presented on how the Columbine shootings have attained a mythical existence and have influenced subsequent rampages.

Rampage Shootings

What is a school rampage shooting? Muschert (2007b) described rampage shootings as “expressive non-targeted attacks on a school institution” (p. 63). Newman (2004) defined rampage shootings as follows:

Rampage shootings are defined by the fact that they involve attacks on multiple parties, selected almost at random. The shooters may have a specific target to begin with, but they let loose with a fusillade that hits others, and it is not unusual for the perpetrator to be unaware of who has been shot until long after the fact. These explosions are attacks on whole institutions—schools, teenage pecking orders, or communities. (pp. 14-15)

To further specify a school rampage shooting, I offer the following defining qualities: (a) A student or a former student brings a gun to school with the intention of shooting somebody, (b) the gun is discharged and at least one person is injured, and (c) the shooter attempts to shoot more than one person, at least one of whom was not specifically targeted. These specifications are in consonance with those of Newman (2004). The advantage of operationalizing the definition of rampage shootings makes it easy to distinguish them from other forms of assaults on schools and allows for classification based on the specific behaviors of the shooters. Muschert (2007b) included faculty, administration, and staff in his definition; however, for the purposes of this article, school employees will be excluded to distinguish school shootings from workplace shootings.

The specification of at least one injury is to distinguish rampage shootings from incidences where a desperate student brings a gun to school and discharges it as an attention getting device. It also excludes specifically targeted shootings, such as those that occurred at Thomas Jefferson High School in Brooklyn, New York, in 1991 and 1992, in which students in two separate incidences brought guns to school to settle a conflict they had with another student (Moore, Petrie, Braga, & McLaughlin, 2003). Also excluded are incidences such as the 1988 school shootings in Pinellas Park High School, Florida, and in 2005 at Campbell County High School in Jacksboro, Tennessee, in which boys brought guns to school to show them off to peers without the intention of shooting anybody. When confronted by school authorities, a weapon was discharged, killing an assistant principal and injuring others (Journey, 1989; Lampe, 2005). Also excluded from the analyses are all shootings related to gang violence and school invasions.

Research Methods

A database was built beginning with lists generated by academic researchers (Moore et al., 2003; Newman, 2004; Vossekuil, Reddy, Fein, Borum, & Modzeleski, 2000). In addition, lists generated by various media outlets (Bower, 2001; Dedman, 2000) and Internet sites of violent school incidents were examined.1 All documented school violence incidents were examined to see if they fit the definition of a school rampage shooting specified above. Once identified as a potential rampage shooting, the Internet was searched for information, including, where available, archives of local and regional newspapers. Potential rampage shootings were entered into an Excel database. All cases in the database were verified through media reports. In some of the more celebrated cases, books had been written about the events, which were read. In most cases, several sources were available describing the assaults on the school. It must be noted that different researchers and reporters used a variety of criteria in defining a rampage shooting, resulting in somewhat different lists among researchers and reporters. Incidences were winnowed down to a list of 55 rampage shootings worldwide engaged in by 57 shooters (Jonesboro and Columbine each had two shooters). The list begins with Charles Whitman at the University of Texas in 1966 and ends with Pekka-Eric Auvinen in Finland in November 2007.

In addition, several researchers (Daniels et al., 2007; Newman, 2004; Trump, 2006) supplied lists of “near misses” and “thwarted attempts” post-Columbine. This researcher also compiled a list of media reports of uncovered plots. Criteria were established to identify serious attempts from those in which there was no evidence of serious intent by the perpetrators. The culling of these lists resulted in the sample described later.

Although in nearly all cases data were able to be triangulated from several sources, in many cases, subsequent reports were based on an original news report, such as an Associated Press dispatch. Therefore, in some cases, although there were several reports, the data source was singular. The validity of the listings is based on the establishment of an objective definition and applying criteria from that definition to all incidences. However, the data are limited by virtue of lack of corroborative data and the lack of verifiability of some Internet sources.

The Cultural Significance of Columbine

Of all the rampage shootings, Columbine stands out as a cultural watershed. First, it was the second-most-covered emergent news event in the decade of the 1990s (Muschert, 2002), outdone only by the O. J. Simpson car chase. Second, at the time, it was the deadliest school rampage shooting in history. Third, Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris were themselves quite media savvy. Harris posted his writings on the Internet, developed “wads” (shooting environments) on the Internet for Doom video game players, and constructed the Trench Coat Mafia Website. There he posted rants, essays, descriptions of vandalism that were perpetrated by him and several friends, hate lists, death threats, and other miscellaneous documents. He and Dylan recorded their lives on video. They taped themselves testing their weapons in the Colorado mountains and made a film in which they starred as professional hit men who were hired by a bullied student to kill his “jock” persecutors. They recorded the so-called basement tapes, in which they revealed the reasons for the shooting, said goodbye to their parents, and vented their theories of revolution. Fourth, the shootings changed behaviors of school officials, police departments, students, and would-be rampage shooters.2

In the months following the Columbine shootings, many suburban and rural middle and high schools hardened their environments, strengthened their security forces, installed metal detectors and surveillance cameras, and instituted “zero- tolerance” antiviolence policies (R. W. Larkin, 2007). The American Civil Liberties Union was swamped with cases in which students were suspended or expelled for expressing sympathies with the Columbine shooters, joking about the Columbine shootings, or venting disapproval of administration security policies. Schools and police departments—including Columbine High School and the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department—increased cooperation and shared information about students who had confrontations with the law. Students who had heretofore ignored or disregarded threats of violence by their peers have become more willing to report them. This phenomenon has been called “the Columbine effect” by the media (Cloud, 1999). The Columbine rampage has become a cultural script for many subsequent rampage shooters. For some, it was a record to be exceeded (e.g., Port Huron, Michigan); for others, it was an incitement (e.g., Conyers, Georgia; Fort Gibson, Oklahoma); for others, it was emulated in their own rampages (e.g., DeAnza College; New Bedford High School; Red Lake, Minnesota); for still others, it was a tradition to be honored in their own attacks (e.g., Virginia Tech). Table 1 lists differences in rampage shootings prior to and following Columbine.

In the basement videotapes, Eric Harris opined that their actions would “kickstart a revolution” of oppressed students who had been victimized and bullied by their peers (Gibbs & Roche, 1999). Although they did not kick-start a revolution, Klebold and Harris established a new paradigm by which all subsequent rampage shootings must be measured. As shown in Table 1, motivations have become more complex and influenced by Columbine; rampage shooters have attempted to influence the media rather than merely be influenced by them. A plethora of thwarted attempts were reported post-Columbine, whereas they were absent from the media before. Students have shown a greater willingness to report threats by their peers, leading to a greater number of thwarted attempts.

Pre-Columbine School Rampage Shootings

Columbine provided a vocabulary and the rationale future rampage shootings. Prior to Columbine, even though revenge was the overwhelming rationale, perpetrators oftentimes were uncertain of their motivations or could not articulate them clearly. For example, Michael Carneal thought that shooting students in the prayer group at Heath High School would give him credibility among the Goth students (Newman, 2004). Because the Goths did not take him seriously, Carneal felt compelled to shoot students; otherwise, his fate would be sealed as a blowhard nerd who could not follow through on his threats. The motives of Kip Kinkel were never adequately ascertained (Lieberman, 2006). In 1998, he killed his parents in their Springfield, Oregon, home and the next day invaded the cafeteria of his high school, killed 4 students, and wounded 25 others. Kip was a member of the football team; other students identified him as a member of the leading crowd. Many students at Thurston High School feared him for his sharp tongue and his aggressiveness. The rampage in the cafeteria may have been part of a psychodrama generated by family conflicts. Both of his parents were teachers, and his father formerly taught at that school.

Pre-Columbine rampage shootings focused on perceived injustices, petty hatreds, perceived female rejections of male advances, misogyny, and revenge for bullying and public humiliation (Moore et al., 2003; Muschert, 2007b). Motivations were personal. The closest to a political rationale that pre-Columbine shooters articulated were the justifications of Luke Woodham and Marc Lépine. Woodham wrote a “manifesto,” a five-page rant that described his feelings of alienation, isolation, and persecution and his experiences of ridicule and humiliation (Bellini, 2001). In it, he stated, “People like me are mistreated every day. I do this to show society ‘push us, and we will push back’” (p. 127).[Aq:1] Lépine shot women as revenge for the feminist movement (Sourour, 1991). These two cases are the only known attempts by rampage shooters to put their motives in a larger context. Neither of these legitimations generated much interest; in the case of Lépine, it was used as evidence of his insanity. Therefore, Columbine became the new paradigm.

Post-Columbine Rampage Shootings

Of the 12 documented school rampage shootings in the United States between Columbine in 1999 and the end of 2007, eight (66.7%) of the rampagers directly referred to Columbine. Table 2 contains a listing of the post-Columbine rampage shootings in chronological order by the perpetrator’s age, racial-ethnic background, location, school, number of victims killed and wounded, whether the perpetrator committed suicide, and how he was influenced by Columbine. All rampage shooters were male. Ages ranged from 13 (Seth Trickey) to 62 (Biswanath Halder), with a median of 17. Of note is that during the year and a half between January 2002 and June 2003, the 2 rampage shootings that occurred were on college campuses; all 3 post-Columbine college campus rampage shootings were conducted by minority students, whereas only 2 secondary school rampages were conducted by minority students (John Wiese, Native American, and Alvaro Castillo, Latino). Of the 9 secondary school rampage shootings between Columbine and the end of 2007, 7 (77.7%) showed Columbine influences.

Columbine influenced subsequent rampage shootings in several ways. First, it provided a paradigm about how to plan and execute a high-profile school rampage shooting that could be imitated. Second, it gave inspiration to subsequent rampage shooters to exact revenge for past wrongs, humiliations, and social isolation. Third, it generated a “record” of carnage that subsequent rampagers sought to exceed. Fourth, Harris and Klebold have attained mythical status in the pantheon of outcast student subcultures. They have been honored and emulated in subsequent rampage shootings and attempts. In all cases, perpetrators either admitted links with Columbine or police found evidence of Columbine influences.

Shootings are identified in the table as “imitated” when the perpetrators copied aspects of the Columbine shooting in their own attempts. Imitations were evident in the attacks in Conyers, Georgia; Fort Gibson, Oklahoma; East Greenwich, New York; Red Lake, Minnesota; Hillsborough, North Carolina; and Virginia Tech University. Perhaps the most imitative shooting was by Jeffrey Weise at Red Lake Senior High School in Minnesota. This particular rampage shooting had several copycat earmarks. First, under the names Todesengel and NativeNazi, he posted rants and expressed admiration of Adolf Hitler on neo-Nazi Internet sites (Benson, 2005). Hitler was lionized by Eric Harris on his Trench Coat Mafia Website. Second, he wore a duster of similar style to those worn by Klebold and Harris (Wilogoren, 2005). Third, prior to shooting a fellow student, Weise asked him if he believed in God. This last act was a reference to one of the myths that emerged from the Columbine shootings that Cassie Bernall was asked whether she believed in God, to which she responded “yes” before she was shot. Although there was no evidence that this confrontation actually occurred, it became an article of faith within the evangelical community and was reported as fact nationwide for several months before it was debunked (Cullen, 1999b; Muschert, 2007a; Watson, 2002).

In numerous cases, students admitted studying or becoming obsessed with the Columbine shootings, which was identified as “study.” The Conyers, Georgia, shooter was obsessed with Columbine and studied it prior to his rampage (Sack, 1999). The shooters in Reno, Nevada, and Hillsborough, North Carolina, intensively studied the Columbine shootings during the weeks prior to their rampages (Blythe, 2004; Rocha, 2007).

Columbine was “referenced” when perpetrators identified the shootings as an inspiration; referred to Columbine before, during, or after the attack as a target to be exceeded; or described their own shooting as an homage to Columbine. References were found to the Columbine shootings in the shootings at Fort Gibson, Oklahoma; East Greenwich, New York; and Virginia Tech. In the weeks prior to the shooting in Santee, California, the shooter claimed that he was going to “pull a Columbine” on his school (McCarthy, 2001). The shooter in Hillsborough, North Carolina, sent an e-mail confession to the principal of Columbine High School prior to his rampage (Rocha, 2007). In his manifesto, the Virginia Tech shooter praised the Columbine killers as martyrs to the cause of the downtrodden (Kleinfield, 2007).

Emergent Phenomena

The significance of the Columbine shootings needs to be explained in light of three emergent phenomena: (a) the dramatic increase of rampage shootings internationally, (b) the expanding contexts of rampage shootings, and (a) the large number of foiled attempts. Rampage shootings since Columbine have gone international, with school shootings modeling Columbine in Canada, Sweden, Bosnia, Australia, Argentina, Germany, and Finland (Table 3). Prior to the Columbine shootings, the only other country to have experienced rampage shootings was Canada, with two in 1975, in Brampton and in Ottawa. In 1989, Mark Lépine targeted women in the École Polytechnic massacre in Montréal. He killed 14 women and wounded 27 before committing suicide.

Of the 11 rampage shootings outside the United States, 6 had direct references to Columbine. The shooting at W. R. Myers High School in Taber, Alberta, Canada, occurred 8 days after Columbine. The shooter, who had been fascinated by Columbine, carried a sawed-off .22-caliber rifle to school under a winter coat (McGee & DeBernardo, 1999). When he was asked by other students who were talking about Columbine if he had a gun under his coat, he pulled the rifle out and began shooting (Lampe, 2000). In 2002, Robert Steinhäuser attempted and achieved a death toll greater than Klebold and Harris in a rampage shooting in Erfurt, Germany, which would be his claim to fame (Gasser, Creutzfeldt, Naher, Rainer, & Wickler, 2004; Mendoza, 2002). Unlike Klebold and Harris, his major targets were teachers; he killed 13 in revenge for being expelled from the school. Sebastian Bosse, who bombed and shot up his school in Emsdetten, Germany, kept a diary in which he praised Eric Harris (“Gunman Praised,” 2006).

In November 2007, Pekka Eric Auvinen killed 8 students and staff and wounded 12 at Jokela High School in Tuusla, Finland, before committing suicide. Auvinen was an outcast at his high school who was harassed and bullied by his peers (DeJong, 2007). He wore a T-shirt during his rampage that said “Humanity is Overrated,” mimicking Klebold and Harris’s wearing of T-shirts that sent messages. Klebold’s T-shirt stated, “Wrath,” and Harris’s said, “Natural Selection.” Auvinen, in imitation of Eric Harris, claimed that he was an advocate of natural selection and that he had the right to rid the world of unfit human beings. He also claimed that he was a revolutionary against enslaving, corrupt, and totalitarian regimes. Auvinen discussed the Columbine shootings on YouTube.com with Dylan Crossey, who was arrested for planning a rampage shooting at Plymouth-Whitemarsh High School in the suburbs of Philadelphia (MacAskill, 2007).

Changing Contexts

The Columbine shootings changed the venue of rampage shootings. Rampage shooters beyond high school age attacked shopping malls in Tacoma, Omaha, and Salt Lake City (“Omaha Gunman,” 2007). The shooter in Tacoma claimed that he did not want to hurt anybody and that he was seeking media attention and wanted to be heard (“Ex-Girlfriend,” 2005). Similarly, the shooter in the Westroads Mall in Omaha thought that his act would make him famous (“Omaha Gunman,” 2007; “Westroads Mall Shooting,” 2007). The shooting at Trolley Square in Salt Lake City had no visible relationship to Columbine.

In December 2007, Matthew Murray was rejected as a missionary from an evangelical organization known as Youth With a Mission. He shot and killed two persons at its headquarters in Arvada, Colorado; on the next day, he killed himself after a rampage attack on the New Life Church, an evangelical megachurch in Colorado Springs, where he killed two more (Meyer, Migoya, & Osher, 2007; “Killer’s Rant,” 2007). During his rampage, Murray posted a rant online under the heading “Christianity this is YOUR Columbine,” in which he plagiarized Eric Harris’s rants.

Failed Attempts

The problem with reported thwarted attempts is the ability to determine whether the plots were serious or they were student fantasies, police overreactions, or media hyperbole. Therefore, to be verified as a serious attempt, two criteria needed to be met: (a) Perpetrators had to have actually amassed weaponry, and (b) evidence of an attack plan had to have been uncovered. To illustrate the difficulties, Daniels et al. (2007) compiled a list of 30 thwarted rampage shootings between 2001 and 2004. Of those threats, only 2 met the criteria. Similarly, of the 12 “near misses” reported by Newman (2004) in the wake of Columbine, 6 met the criteria of a serious threat. For example, Newman listed a plot in Anaheim, California, that occurred on May 19, 1999, less than a month after Columbine. Police working on a student tip uncovered a cache of weapons and Nazi paraphernalia collected by two eighth graders (Gottlieb & Kandel, 1999). However, there was no evidence that they had planned a shooting. No charges were filed.

Although students have made thousands of threats, compiled hit lists, dreamed Columbine fantasies, and accumulated arsenals, they cannot be verified as rampage shooting attempts. This researcher has compiled 11 planned school rampage shootings that were thwarted in the days before they were to be executed. These 11 were selected because there was evidence indicating that the perpetrators actually planned to carry them out, despite the protestations of their defense attorneys. Verified attempts are listed in Table 4.

All 11 reported attempts had earmarks of the Columbine shootings. For example, the students at Hollins Woods Middle School not only imitated the Columbine shooters; they wanted to have a greater body count (Associated Press, 1999). The prospective shooter at De Anza College created a Web site memorial to Klebold and Harris (Fayle, 2001; Gaura, Stannard, & Fin, 2001). One of the striking differences between reported thwarted attempts and actual shootings after Columbine is that all of the actual shootings were committed by individuals. Of the 11 reported thwarted shootings, only 4 were planned by individuals; the others were conspiracies that numbered between three and five students. As with actual shootings, perpetrators were overwhelmingly male, with the singular exception of a female in the conspiacy in New Bedford, Massachusetts (Butterfield & McFadden, 2001).

Reported thwarted attempts typically took their inspiration from Columbine. One or more students hatched a plan of attack on their school. In each case, with the possible exception of the De Anza College attempt, the motivation was to exact revenge against the jocks and/or preps[Aq:2] that had bullied and humiliated them. In the case of Al DeGuzman at De Anza College, a 2-year institution in California’s Silicon Valley, his motivation was more complicated. It involved a generalized hatred toward peers because of his isolation and a desire to commit suicide by police fire (Gaura et al., 2001).

Potential rampagers would begin collecting a cache of weaponry that they would use in their attacks. In many cases, the weaponry clearly imitated that used by Klebold and Harris in Columbine (Smith, 2001). With the singular exception of the Port Huron, Michigan, attack, students had assembled large arsenals that included shotguns, semiautomatic weapons, bombs, and stores of ammunition. In the Port Huron case, students had stolen a single gun and were planning to use it to steal other weaponry (Bower, 2001).

The incidences at Port Huron, Michigan (Bower, 2001), and Hoyt, Kansas (Gale Group, 2001), were uncovered by anonymous tips from uninvolved students. More typical have been conspirators who have revealed themselves electronically. The incident in Elmira, New York, was revealed when the perpetrator sent a suspicious text message to a female friend, who then alerted authorities. Others have revealed themselves on the Internet. Internet boasts thwarted the plans of the Riverton, Kansas, shooters (Kabel, 2006); the Chippewa Valley High School attempt (Kamarenko, 2004); and the Plymouth-Whitemarsh High School plans in the Philadelphia suburbs (“Police,” 2007). The attempted shooting at Malcolm, Nebraska, was uncovered by school authorities (Agence France Presse, 2004). The New Bedford, Massachusetts, attempt was revealed by the female participant (“Girl Arraigned,” 2001), who was afraid that her favorite teacher might be hurt.

Conclusion

Most rampage shootings are a form of retaliatory violence; they are revenge for perceived past wrongs. Columbine gave new meaning to school rampage shootings, especially to disaffected outcast students not only in America but throughout Western society. Rampage shootings were no longer the provenance of isolated, loner students who were psychologically deranged. Columbine raised rampage shootings in the public consciousness from mere revenge to a political act. Klebold and Harris were overtly political in their motivations to destroy their school (R. W. Larkin, 2007). In their own words, they wanted to “kick-start a revolution” among the dispossessed and despised students of the world (Gibbs & Roche, 1999). They understood that their pain and humiliation were shared by millions of others and conducted their assault in the name of a larger collectivity. Klebold and Harris identified the collectivity—outcast students—for which they were exacting revenge. That is what distinguishes Columbine from all previous rampage shootings.

The Columbine massacre, because of its spectacular and unprecedented nature, evoked a public awareness that included an address to the country by the president of the United States. It generated a national debate on numerous issues: school violence, gun control, bullying, child rearing, parental responsibility, school climates, video games, violent media, societal permissiveness, race, and religious values, to name the most obvious (Muschert, 2002). Muschert’s (in press) data clearly show that the focus of media coverage of the Columbine shootings was on the why rather than the what of the shootings. The Columbine shootings opened a huge gap in the hegemonic ideology that major media attempted to fill. They violated assumptions about the peacefulness of suburban schools and communities. Earlier school shootings raised the issue; Columbine brought it to a head. Such planned violence was unheard of even in urban ghettos. The shootings also raised issues about the mental and moral state of the perpetrators. Prior to the shootings, they were average teenagers; afterward, they became evil, mentally unbalanced monsters; psychopaths; and instruments of the devil (Cullen, 2004).

The function of the news media was to “normalize” the Columbine shootings (Croteau & Hoynes, 2002). An event that was shocking, “senseless,” and seemingly incomprehensible to the public had to be explained. Within the evangelical community, the Columbine shootings exemplified their persecution and were defined as the intrusion of Satan into human affairs (Cullen, 1999a; Epperhart, 2002; R. W. Larkin, 2007; Porter, 1999). However, the rest of America had to be pacified. The problem was that the perpetrators appeared to be “normal.” Blame could not be attributed to broken families, because the Klebold and Harris families were intact and the parents were caring about their children. It could not be attributed to drugs because toxicology screenings on both boys came back negative. Therefore, the media focused on their prior brush with the criminal justice system and Eric Harris’s use of Luvox for depression, his declared hatred for other races and religious groups, and his admiration for Adolf Hitler. Harris was identified as the more culpable leader and Klebold as the desperate, socially isolated follower (Muschert, 2002). Contextual issues, such as bullying and the cult of the athlete, that pervaded Columbine High School were raised by some journalists (Adams & Russakoff, 1999) and dismissed by others (Cullen, 2004). Bullying and alienation were ignored by the evangelical community and relegated to secondary status by the corporate media, which adopted psychological pathology as the major explanation (Muschert, 2002).

After it was reported that Klebold and Harris had made the basement tapes to explain their motivations, the media clamored for a viewing. The sheriff of Jefferson County allowed major media journalists to view the tapes at a one-time-only presentation. A synopsis was then published in the December 20, 1999, issue of Time magazine (Gibbs & Roche, 1999). Consequently, the motivations and intentions of Klebold and Harris became subjects of intense debate on the Internet. Many of those who were blogging did not accept the corporate media’s definition of the situation. Neo-Nazi sites posited a Jewish conspiracy because of Klebold’s Jewish roots; however, many others spoke sympathetically of Harris and Klebold and viewed them as martyrs to the cause of outcast students who had been victimized by their higher status peers (D. G. Larkin, 2000). Students arrested in “Columbine-style” rampage shooting conspiracies began emulating the behavior of Klebold and Harris shortly after the publication of the Time article (“3 Charged,” 2001).

As an immediate consequence of the spectacular worldwide news coverage of the Columbine massacre, within days, students were phoning in bomb hoaxes to their schools, drawing up enemies lists, issuing death threats, and bringing guns to school to shoot their peers (“Summary,” 1999). Most of the thwarted rampages were conspiracies among a number of students who had grievances against the school. These grievances centered on bullying, harassment, and the usual predatory violence directed against outsider students. Prior to Columbine, there was no evidence of conspiracies to bomb and shoot up one’s school.

One of the cultural scripts that is a consequence of the Columbine shootings is that the shooters engage in their rampages to “make a statement.” The body count, almost always innocent bystanders, exists primarily as a method of generating media attention. This was certainly the case in the most deadly rampage shootings of John Wiese at Red Lake and Cho Seung-Hui at Virginia Tech. It was also the case in 2007 with Robert Hawkins, who killed nine at the Westroads Mall in Omaha, Nebraska, and Matthew Murray, who attempted two rampage shootings on consecutive days in Colorado at Youth With a Mission and the New Life Church, both institutions of the evangelical community.

Killing for notoriety is the second outcome of the Columbine shootings. The media awareness of Klebold and Harris is discussed in detail elsewhere (R. W. Larkin, 2007). When a rampage shooting occurs in a community, it is overwhelmed by media (Lieberman, 2006; Muschert, 2002; Newman, 2004). The extent of media attention seems to be closely related to body count. The most spectacular shootings in Paducah, Jonesboro, Springfield, and Columbine and at Virginia Tech were characterized by media feeding frenzies in which news outlets oftentimes competed with police and emergency medical services for space and attention from victims. Local residents in Paducah and Jonesboro told stories of reporters who invaded their privacy, misrepresented themselves, and used various ruses to interview traumatized citizens (Newman, 2004). In the postmodern world, news has become entertainment. Tragedy has been converted to sensation and sensation is operationalized into viewership, Nielsen points, and market share, which is then materialized in advertising revenues. The communities in which rampage shootings occur are victimized twice: first by the shootings themselves and second by the media who rampage through their communities to get the story (Altheide, 2004). The sensationalism of a rampage shooting can provide headlines for 3 days of news cycles; Columbine was still headline news 3 weeks after the shootings, primarily because of copycat phenomena (Muschert, 2002).

Social structural and cultural characteristics that have led to rampage shootings, such as the toleration of predatory behaviors on the part of elite students, the lionization of winners and the punishment of losers, the male ethic of proving one’s masculinity through violence, the easy availability of assault weapons to just about anyone, and the media fascination and exploitation of violence, go far beyond the communities that experienced rampage shootings. Rampage shootings can occur in almost any community. Violence down the social system, especially in America’s high schools, is redefined as “fun” or “boys being boys” (Lefkowitz, 1997). Researchers have documented (Boney-McCoy & Finkelhor, 1996; Boulton & Hawker, 1997; Dukes & Stein, 2005; Kilpatrick et al., 2003) the deleterious consequences that the daily rituals of humiliation and bullying have on the victims. Klebold and Harris, in their spectacular assault on Columbine High School, gave voice to outsiders, to loser students, to those left out of the mainstream, to the victims of jock and prep[Aq:3] predation. Although there have been grassroots attempts to reduce violence in schools, since Columbine, the federal government has made assault weapons easier to obtain (Lawrence, 2004), and states have adopted more punitive juvenile justice sentencing guidelines (Mears, 2002). To a persecuted and angry student who wishes to attack his school and community, such social policies are an invitation and a dare. To such a student, payback consists of killing convenient targets, making a statement, and dying in a blaze of glory.

References

Adams, L., & Russakoff, D. (1999, 13 June). High schools’ “cult of the athlete” under scrutiny. The Washington Post, p. 1ff.

Agence France Presse. (2004). US teenager held over alleged school bomb plot. Retrieved February 4, 2008, from http://www.mywire.com/pubs/AFP/2004/03/19/398032/print

Altheide, D. L. (2004). Media logic and political communication. Political Communication, 21(3), 293-296.

American teen’s lawyer reveals computer links. Columbine massacre was one topic of discussion. Guardian. Retrieved March 7, 2008, from http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2007/nov/13/usa.schoolsworldwide

Associated Press. (1999, May 19). Michigan teenagers charged in plot. Retrieved January 11, 2008, from http://web.dailycamera.com/shooting/16cplot.html

Bellini, J. (2001). Child’s prey. New York: Pinnacle.

Benson, L. (2005, March 24). Web postings hold clues to Weise’s actions Retrieved January 4, 2008, from http://news.minnesota.publicradio.org/features/2005/03/24_ap_moreweise/

Blythe, B. (2004, November 22). Romano pleads guilty, facing 20 years. Retrieved January 5, 2008, from http://capitalnews9.com/shared/print/default.asp?ArID=105530

Boney-McCoy, S., & Finkelhor, D. (1996). Is youth victimization related to trauma symptoms and depression after controlling for prior symptoms and family relationships? A longitudinal, prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 1406-1416.

Boulton, M. J., & Hawker, D. S. (1997). Non-physical forms of bullying among school pupils: A cause for concern. Health Education, 2, 61-64.

Bower, A. (2001, January 5). Scorecard of hatred. Time Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.time.com/time/printout/0,8816,999476,00.html [Aq:4]

Butterfield, F., & McFadden, R. D. (2001, 26 November). 3 teenagers held in plot at Massachusetts school. The New York Times, p. 16.

Cloud, J. (1999). The Columbine effect. Time Magazine, 154(23), p. 12ff.

Croteau, D. R., & Hoynes, W. (2002). Media/Society: Industries, images, and audiences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge.

Cullen, D. (1999a, November 17 ). I smell the presence of Satan. Salon.com. Retrieved May 15, 2003, from http://archive.salon.com/news/feature/1999/05/15/evangelicals/index.html

Cullen, D. (1999b, September 30). Who said “yes”? Salon.com. Retrieved October 2, 2005, from http://www.salon.com/news/feature/1999/09/30/bernall/print.html

Cullen, D. (2004). The depressive and the psychopath. Slate. Retrieved September 18 2004, from http://slate.msn.com/id/2099203/

Daniels, J. A., Buck, I., Croxall, S., Gruber, J., Kime, P., & Govert, H. (2007). Content analysis of news reports of averted school rampages. Journal of School Violence, 6(1), 83-99.

Dedman, B. (2000, October 15). School shooters: Secret Service findings. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved from http://www.secretservice.gov/ntac/chicago_sun/find15.htm [Aq:5]

DeJong, P. (2007, November 8). Police say Finnish school gunman was bullied social outcast, picked on victims at random. ABC News. Retrieved March 7, 2008, from http://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory?id=3837063

Dukes, R. L., & Stein, J. A. (2005, August). Bullying during adolescence: Correlates, predictors, and outcomes among bullies and victims. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, San Francisco.

Epperhart, B. (2002). Columbine: Questions that demand an answer. Tulsa, OK: Insight.

Ex-girlfriend: Mall suspect wrote of anger before spree. (2005). USA Today. Retrieved from http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2005-11-21-text-mall-shooting_x.htm [Aq:6]

Fayle, K. (2001, January 14). Crisis averted: De Anza College students were spared what could have been a massacre. Cupertino Courier. Retrieved from http://www.community-newspapers.com/archives/cupertinocourier/02.07.01/cover-0106.html [Aq:7]

Gale Group. (2001, January 14). Safe school helpline credited with preventing Columbine-style plot at Kansas high school. Business Wire. Retrieved from http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0EIN/is_2001_Feb_21/ai_70703407/print

Gasser, K. H., Creutzfeldt, M., Naher, M., Rainer, R., & Wickler, P. (2004). Bericht der Kommission Gutenberg-Gymnasium. Erfurt, Germany. [Aq:8]

Gaura, M. A., Stannard, M. B., & Fin, S. (2001, January 31). De Anza College bloodbath foiled—Photo clerk calls cops. SFGate.com. Retrieved January 14, 2008, from http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2001/01/31/MNDEANZAPM.DTL

Gibbs, N., & Roche, T. (1999, December 20). The Columbine tapes. Time Magazine, p. 4ff.

Girl arraigned in Massachusetts school bomb plot. (2001, November 28). Cable News Network. Retrieved February 18, 2008, from http://archives.cnn.com/2001/LAW/11/28/school.plot/index.html

Gottlieb, J., & Kandel, J. (1999, January 11). Anaheim police find bombs in 2 boys’ homes. Los Angeles Times. Available from http://www.latimes.com

Gunmen praised Columbine killer. (2006). Independent. Retrieved from http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4158/is_20061123/ai_n16861198/print?tag=artBody [Aq:9]

Journey, M. (1989, January 16). Official tells of shooting at high school. St. Petersburg Times. Available from http://www.tampabay.com

Kabel, M. (2006, February 20). 5 Kansas students held in school shooting plot. Seattle Times. Available from http://seattletimes.nwsource.com

Kamarenko, D. (2004, February 19). Quiet teen’s terror plot stuns school Retrieved May 17, 2008, from http://www.crime-research.org/news/27.09.2004/665/

Killer’s rant filled with profanity, hate. (2007). Denver Post. Retrieved from http://www.denverpost.com/ ci_7691068 [Aq:10]

Kilpatrick, D. G., Ruggiero, K. J., Acierno, R., Saunders, B. E., Resnick, H. S., & Best, C. L. (2003). Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: Results from the national survey of adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(4), 692-700.

Kleinfield, N. R. (2007, April 22). Loner becomes a killer; before deadly rage, a lifetime consumed by a troubling silence. The New York Times, p. 1A.

Lampe, A. (2000). Violence in our schools: January 1, 1980 through December 31, 1999. Retrieved December 24, 2007, from http://www.columbine-angels.com/Shootings-1980-2000.htm

Lampe, A. (2005). Violence in our schools: January 1, 2000 through December 31, 2004. Retrieved December 24, 2007, from http://www.columbine-angels.com/Shootings-2005-2009.htm

Larkin, D. G. (2000). Views and trues. New York: La Guardia College.

Larkin, R. W. (2007). Comprehending Columbine. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Lawrence, J. (2004). Federal ban on assault weapons expires. USA Today. Retrieved from http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/2004-09-12-weapons-ban_x.htm [Aq:11]

Lefkowitz, B. (1997). Our guys. New York: Vintage.

Lieberman, J. (2006). The shooting game. Santa Ana, CA: Seven Locks.

MacAskill, E. (2007, November 13). Finnish school killer was in contact with US plotter: McCarthy, T. (2001, January 3). Warning: Andy Williams here. Unhappy kid. Tired of being picked on. Time Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.time.com/time/printout/0,8816,102077,00.html# [Aq:12]

McGee, J. P., & DeBernardo, C. R. (1999). The classroom avenger. Forensic Examiner, 8(5/6), 1-16.

Mears, D. (2002). Sentencing guidelines and the transformation of juvenile justice in the 21st century. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 18(1), 6-19.

Mendoza, A. (2002). Robert Steinhäuser. Retrieved November 28, 2007, from http://www.mayhem.net/Crime/steinhaeuser.html

Meyer, J. P., Migoya, D., & Osher, C. N. (2007, December 12). YOUR Columbine. Denver Post. Retrieved from http://www.denverpost.com/ci_7696043 [Aq:13]

Moore, M. H., Petrie, C. V., Braga, A. A., & McLaughlin, B. L. (2003). Deadly lessons: Understanding lethal school violence. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Muschert, G. W. (2002). Media and massacre: The social construction of the Columbine story. Boulder, CO: University of Colorado.

Muschert, G. W. (2007a). The Columbine victims and the myth of the juvenile superpredator. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 5(4), 351-366.

Muschert, G. W. (2007b). Research in school shootings. Sociology Compass, 1(1), 60-80.

Muschert, G. W. (in press). Frame-changing in the media coverage of a school shooting: The rise of Columbine as a national concern. Social Science Journal.

Newman, K. S. (2004). Rampage: The social roots of school shootings. New York: Basic Books.

Omaha gunman suicide notes. (2007). The Smoking Gun. Retrieved from http://www.thesmokinggun.com/archive/years/2007/12070720maha1.html [Aq:14]

Police: Team planning “Columbine-like” attack had weapons cache. (2007, October 12). NBC News. Retrieved February 20, 2008, from http://www.nbc10.com/news/14317753/detail.html#

Porter, B. (1999). Martyr’s torch: The message of the Columbine massacre. Shippensburg, PA: Destiny Image.

Rocha, J. (2007, May 24). Castillo won’t be executed. Raleigh News and Observer. Retrieved from http://www.newsobserver.com/news/crime_safety/castillo/story/578097.html [Aq:15]

Sack, K. (1999, May 21). Youth with 2 guns shoots 6 at Georgia school. The New York Times. Available from http://www.nytimes.com

Smith, Z. (2001, February 8). Middle school students’ conspiracy in Fort Collins. The Firing Line. Retrieved February 1, 2008, from http://www.thefiringline.com/forums/showthread.php?t=56650

Sourour, T. Z. (1991). Report of coroner’s investigation. Available from http://www.diarmani.com/Montreal_Coroners_Report.pdf

Summary of real-time reports concerning a shooting at the Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado. (1999). ERRI Emergency Services Report, 3.

3 charged in Columbine-style plot. (2001, February 6). CBS News. Retrieved January 11, 2008, from http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2001/02/06/national/printable269726.shtml

Trump, K. W. (2006). Columbine seventh anniversary: Seven foiled school violence plots since March [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.expertclick.com/NewsReleaseWire/default.cfm?Action=ReleaseDetail&ID=12365 [Aq:16]

Vossekuil, B., Reddy, M., Fein, R., Borum, R., & Modzeleski, W. (2000). U.S.S.S. Safe School Initiative: An interim report on the prevention of targeted violence in schools. Washington, DC: U.S. Secret Service, National Threat Assessment Center.

Watson, J. (2002). The martyrs of Columbine: Faith and the politics of tragedy. New York: Palgrave.

Westroads Mall shooting. (2007). Wikipedia. Retrieved December 26, 2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Westroads_Mall_shooting

Wilogoren, J. (2005, 22 March). Shooting rampage by student leaves 10 dead on reservation. The New York Times, p. A1.

#columbine#mass shootings#violence#school shootings#rampage shootings#school violence#bullying#media

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

2022 Person of the Year

Established in 1992, each year, this award is given to an individual or partner organization for their outstanding leadership and contributions in the field of nephrology, and their dedication and service to the mission of the Kidney Foundation of Ohio.

The 2022 Person of the Year is Hernan Rincon-Choles, MD, MS, MBA, FASN, Staff Nephrologist at the Cleveland Clinic Glickman Urological & Kidney Institute Department of Kidney Medicine and Assistant Professor of Medicine at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University.

Hernan Rincon-Choles was born in Cartagena, Colombia, South America. He is the eldest of 9 children. He obtained his medical degree from the Universidad de Cartagena, in Cartagena, Colombia, South America, in 1989 and practiced as a General Practitioner until 1992. He came to the United States and trained in Internal Medicine at New York Medical College, Our Lady of Mercy Medical Campus in the Bronx, New York, from 1993 to 1996. He practiced as a general internist in Corpus Christi, Texas until 1999 and then joined the nephrology fellowship program at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio and the South Texas Veterans Health Care System in San Antonio, Texas in 1999 where he did a basic science post-doctoral research fellowship investigating the pathobiology of diabetic nephropathy and mechanisms of proteinuria, participated in the development of animal models of diabetic nephropathy, joined as a Clinical Instructor of Medicine in 2002 and was then promoted to Assistant Professor of Medicine in 2003. He obtained a Master’s degree in Clinical Science in 2005, was the Medical Director for University Dialysis Southeast Dialysis Center from 2003 to 2004, and was co-Director of the Nephrology Fellowship Program from 2004 to 2006.

He then moved to Syracuse, New York, where he worked as a hospitalist at Saint Joseph’s Hospital in 2006, joined a private practice nephrology group from 2007 to 2010, participated in an academic hospitalist-nocturnist program at the Syracuse Veterans Administration Hospital from 2010 to 2013, joined the State University of New York Upstate Medical University as Assistant Professor of Medicine from 2010 to 2013, obtained the Satki Mookherjee Faculty Teaching Award 2011-2012 from the Department of Medicine, and participated as nocturnist for Crouse Hospital from 2011 to 2013.

Dr. Rincon-Choles receiving the 2022 Person of the Year Award at the 30th Annual Gala from Dr. Crystal Gadegbeku, Chair of the Glickman Urological and Kidney Institute Department of Kidney Medicine

He joined the Glickman Urological and Kidney Institute Department of Nephrology in 2013, pursuing his interest in critical care nephrology, health disparities, chronic kidney disease, and end-stage kidney disease. He is assistant Professor of Medicine at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of the Case Western Reserve University. He has research interest into the pathogenesis, epidemiology and treatment of chronic kidney disease and participates as a Co-Principal Investigator, event adjudicator, and writing committee member for the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study, Cleveland Clinic Site.

Dr. Hernan Rincon-Choles and Linda, a patient of his who he tirelessly worked to get on the kidney transplant list.

Hernan is interested in improving medical care for minority populations. He served as the Medical Director for the Ohio Renal Care Group Huron Dialysis Center and ran a renal clinic from 2014 to 2021 at Stephanie Tubbs Jones Family Health Center in East Cleveland, Ohio. He is currently running a renal clinic for the Hispanic community at Lutheran Hospital in Cleveland, Ohio. He helped run the annual Minority Men’s Health Fair at the Glickman Urological and Kidney Institute Department of Nephrology and Hypertension at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in Cleveland, OH, from 2014 to 2020.

He participates as an advisor on the Medical Advisory Board for the Kidney Foundation of Ohio, and the Patient Symposium Committee and Advocacy Committee of the National Kidney Foundation. He also served as the Medical Chairman of the Northeast Ohio National Kidney Foundation Kidney Walk from 2018 to 2022, and participated as an Advisor to the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s Chronic Kidney Disease Disparities: Guide for Primary Care, prepared for the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services in August 2019.

He is a reviewer for the Annals of Thoracic Surgery and for the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, ASN NEPHSAP and KSAP panel reviewer group, and completed a Healthcare MBA at Baldwin Wallace University in 2020.

He is married to Barbara (Rachel) Pollack-Rincon, and has a son, Hernan Benjamin Rincon, and a daughter, Jennifer Gloria Rincon.

Dr. Hernan Rincon-Choles and his wife, Rachel

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Video

ERGREIFEND: "ICH BIN SEIT 20 JAHREN PROFESSORIN FÜR ETHIK AM HURON COLLEGE DER UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO, EINER DER GRÖSSTEN UNIVERSITÄTEN IN KANADA. MEIN ARBEITGEBER HAT MIR GERADE VORGESCHRIEBEN, DASS ICH MICH GEGEN COVID IMPFEN LASSEN MUSS, WENN ICH MEINEN JOB ALS PROFESSOR WEITER AUSÜBEN WILL. ICH BIN HIER, UM EUCH ZU SAGEN, DASS ES ETHISCH FALSCH IST, JEMANDEN ZU EINER IMPFUNG ZU DRÄNGEN. WENN EUCH DAS PASSIERT, MÜSST IHR DAS NICHT TUN. Meine Aufgabe ist es, Studenten zu lehren, kritisch zu denken und Fragen zu stellen, die ein falsches Argument entlarven können.(...)" AM 07.09.2021 WURDE DR. JULIE PONESSE ENTLASSEN: IHRE KLARHEIT UND STANDHAFTIGKEIT SIND VORBILDLICH. SIE IST IM RECHT UND JEDER ETHISCH DENKENDE MENSCH WEISS DAS ! Quelle: https://www.bitchute.com https://www.instagram.com/p/CTo2hN0A75X/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Text

Western University professor refuses to abide by school’s vaccine mandate in the name of ethics

Western University professor refuses to abide by school’s vaccine mandate in the name of ethics

A Western University professor is speaking out against the institution’s vaccine mandate, questioning the ethics of “coercing people into medical procedures” for those refusing to get the COVID-19 vaccine. The professor states in the video, which has since been removed from YouTube, that she fears for her employment.

Julie Ponesse, an ethics professor at Western’s Huron University College,…

View On WordPress

#anti vaccine#BN1#coronavirus#covid-19#InHouseArticle_thestar#Julie Ponesse#KMI1#Maxime Bernier#professor#smg_gta#smg2_news#vaccination#Western University

0 notes

Photo

A rare, privately printed Canadian salmon work—a fly fishing guide with an emphasis on salmon fishing, including tackle, casting and fishing.

A rare, privately printed Canadian salmon work—a fly fishing guide with an emphasis on salmon fishing, including tackle, casting and fishing. ^Cronyn was a a British fighter pilot during WWI. He was involved in the dogfight that claimed the life of German ace, Werner Voss, recepient of the Blue Max. Voss was considered by some to be the one pilot who could match Baron Von Richthofen (Red Baron). Cronyn wrote a letter to his father telling him that his plane had been shot up so badly that it was written off and that he was lucky to be alive. He also wrote that he couldn't sleep that night because of his ordeal. Cronyn wrote of his experience in "Other Days," which he self published in 1976.

Cronyn as a part of an illustrious family. His great-grandfather was the first bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Huron. He founded Huron University College which grew into the secularized University of Western Ontario. His maternal grandfather was the founder of John Labatt, Ltd. (Labatt Brewing Company). His brother was the actor Hume Cronyn and his first cousin was the artist Hugh Cronyn.

“The author was the Chancellor of the University of Western Ontario. He fished the Restigouche and it is probably that river he refers to in The Fly Leaf. This little book is rare, charming, and very appealing". — From the Charles Wood's "Biobliotheca Salmo Salar.” The first edition was printed in 1959 in slightly larger format and thought to be limited to 25 copies. Not in Bruns

0 notes

Text

Honoring Nations 2020 Semifinalists

Agua Caliente People Curriculum -- Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians

The Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians have lived in, what is now known as, Palm Springs since time immemorial. However, the only public school lessons about the Agua Caliente were developed without input from the tribe, creating misinformation and stereotypes. To address this, the Agua Caliente partnered with the Palm Springs school district and the district’s philanthropic foundation to build a curriculum that reflects both the history and contemporary realities of the Band. Meeting the state of California’s educational standards and with the approval of the tribe, this elementary-level curriculum fosters greater community understanding by teaching the history and culture of the Agua Caliente people through their own words.

Learn more

Cherokee Nation Hepatitis C Elimination Program -- Cherokee Nation

Native communities face much higher rates of Hepatitis C (HCV) than the general US population, as well as some of the highest rates of HCV-induced mortality. In 2015, Cherokee Nation Health Services partnered with the Centers for Disease Control to pioneer the first HCV elimination program of its kind. By developing unique and effective screening processes, linking patients to care, the Cherokee Nation Hepatitis C Elimination Program improves health outcomes for citizens living with HCV. The program works with tribes and communities across the country to design their own HCV elimination programs, strengthening public health systems and creating a future where communities and cultures can thrive.

Learn more

Cherokee Nation ONE FIRE -- Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation established ONE FIRE Victim Services to address domestic and sexual violence in their community. ONE FIRE (Our Nation Ending Fear, Intimidation, Rape and Endangerment) functions with a streamlined, “one-stop” strategy to provide wraparound services to survivors of domestic abuse, sexual assault, and dating violence in the tribe’s 14-county jurisdiction, whether they be women or men, Native or not. Using a trauma-informed care model, ONE FIRE meets the immediate needs of those in crisis in the short-term while supporting the healing of survivors and their families and addressing the root causes of domestic violence and sexual assault in the long-term to create a safer community.

Learn more

Chickasaw Nation Medical Family Therapy -- Chickasaw Nation

The separation of physical health and behavioral health treatment is commonplace in the western health system. For Chickasaw Nation citizens, receiving care in this type of system meant many did not access the mental health care and social support they needed. In 2014, the Nation reconfigured its health service delivery to include behavioral health consultants called medical family therapists into every patient’s care team. Medical family therapy, which ranges from child welfare programs to substance abuse treatment, integrates behavioral health work into all medical visits throughout the Nation’s health care system so patients receive their care in a coordinated and holistic way, improving their overall quality of life.

Learn more

Chickasaw Nation Productions -- Chickasaw Nation

Carrying on a longstanding tradition of storytelling while also challenging the misrepresentation of Native peoples by outside media sources, Chickasaw Nation Productions produces feature-length films that preserve and share traditional and contemporary stories of the Chickasaw Nation and its people. Along with reinforcing positive representations, the program provides educational opportunities for Oklahoma public school students to meaningfully engage with Chickasaw history. It also creates avenues for tribal members to participate in every aspect of media production. Through empowered storytelling brought to life, each new film and documentary serves to keep the Nation’s stories, language, and traditions alive and relevant.

Learn more

D3WXbi Palil -- Squaxin Island Tribe

The Squaxin Island Tribe’s Northwest Indian Treatment Center is a residential chemical dependency treatment facility that serves American Indians with chronic substance abuse and relapse patterns related to unresolved grief and complex trauma. Given the spiritual name “D3WXbi Palil,” meaning “Returning from the Dark, Deep Waters to the Light,” the Center’s programs focus on supporting Native people with chemical dependency and chronic relapse issues to remember, relearn, and return to their true identities—who they were born to be. Using culturally adapted practices, D3WXbi Palil provides clinical, cultural, and support services to clients during a 45-day treatment program, intensive recovery support, and recovery coach programming to build supportive networks.

Learn more

didgwálic Wellness Center -- Swinomish Indian Tribal Community

The opioid epidemic has had devastating effects on Native and non-Native populations across the country. In response to a concerning rate of overdose deaths in their community in recent years, the Swinomish Indian Tribal Senate established the didgwálic Wellness Center. The Center is a holistic wellness program that improves health and social outcomes by removing barriers to treatment. Focusing on a whole-person service delivery model, didgwálic provides comprehensive, culturally relevant, and personalized care for each patient to sustain a life of recovery and healing with their broader community.

Learn more