#ISATIS

Text

This song uis literally isat

#my art#doodle#isat spoilers#in stars and time spoilers#in stars and time#isat#isat siffrin#isat mirabelle#isat isabeau#isat odile#isat boniface#isat loop#Theres already a small animation using the song but if I had a program to animate you BET i would also#it fits sooo well it hurts. I ACTUALLY DREW THIS AS LIKE MY THIRD PIECE FOR ISATY BUT I NEVER POSTED IT#cuz I didnt like it. I do now tho. So you get to see it after. what. a month? or two#you can see ive always liked pink#I cant explain a THING to yoooou I wouldnt know where to STAART#AAAAAAAAAAAGH

655 notes

·

View notes

Text

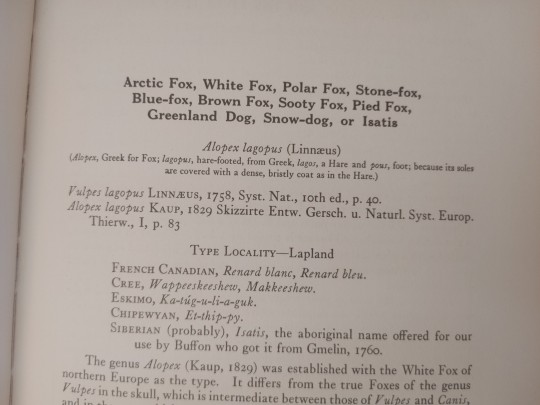

Arctic Fox aliases of Lives of Game Animals by Ernest Thompson Seton in the arctic fox chapter of Volume 1 part 2

Arctic Fox, White Fox, Polar Fox, Stone-Fox, Blue-Fox, Brown Fox, Sooty Fox, Pied Fox, Greenland Dog, Snow-Dog, or Isatis

Alopex lagopus or Vulpes lagopus

French Canadian; Renard blanc, Renard blue

Cree; Wappeeskeeshew, Makkeeshew

[Inuit]; Ka-túg-u-li-a-guk

Chipewyan; Et-thip-py

Siberian (probably); Isatis, the aboriginal name offered for our use by Buffon who got it from Gmelin, 1760.

#arctic fox#stars help me as i type these all out#i aint writing the slur for inuit though#greenland dog#which is INCREDIBLY funny to me who knows that as a dog breed#white fox#stone-fox#blue-fox#polar fox#brown fox#sooty fox#pied fox#snow-dog#isatis#alopex lagopus#vulpes lagopus#renard blanc#renard bleu#wappeeskeeshew#makkeeshew#ka-túg-a-li-a-guk#et-thip-py#cree#inuit#chippewa#siberian indigenous#sure would like to know who in siberia that came from#or if it just didnt lmfao#curious either way

1 note

·

View note

Text

#my art#pressure roblox#roblox pressure#sebastian solace#sky x pressure#sky children of the light#s: cotl#skycotl#thatskygame#isati makes a purchase! though maybe they shouldn’t recharge themself right in front of seb

381 notes

·

View notes

Video

n552_w1150 by Biodiversity Heritage Library

Via Flickr:

English botany, or, Coloured figures of British plants /. London :R. Hardwicke,1863-1886.. biodiversitylibrary.org/page/12445123

#Great Britain#Pictorial works#Plants#New York Botanical Garden#LuEsther T. Mertz Library#bhl:page=12445123#dc:identifier=https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/12445123#flickr#isatis tinctoria#woad#dyer's woad#glastum#Asp of Jerusalem#botanical illustration#scientific illustration

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

An anti-influenza virus compound, Gibberellin B

Isatis Radix, also known as the big blue heel, is the dried root of the plant woad or big blue-green, which can be used clinically for influenza, mumps, chickenpox, and measles.

The liver is the leading site of drug metabolism, and applying the liver microsomal model allows for metabolite analysis studies of drugs. Drug metabolite analysis has evolved rapidly to become an essential part of pharmacokinetic studies.

According to a study reported on the internet, it was found that based on the systematic screening of the active antiviral ingredients of radix isatidis, straight heliotropin B was the most abundant compound among the 31 compounds isolated from the aqueous extract of radix isatidis, and compound activity testing studies showed that it had significant antiviral and antioxidant activities.

Therefore, the lignan compound Gibberellin B contained in Isatidis Radix no toginseng is one of the critical active substance bases of Isatidis Radix no toginseng against viruses.

Larcholin-4,4'-di-O-β-D-diglucoside was the most abundant lignan-like compound isolated from the active antiviral site of Isatidis Radix no toginseng, accounting for about 2% of the active site and 0.04% of the raw drug amount.

In vitro anti-HSV viral activity showed some inhibitory effect on HSV-1 and HSV-2 type viruses. Moreover, it has been reported in the literature that Clemastanin B has antioxidant and free radical scavenging activity, has a superoxide dismutase-like effect and has a significant protective effect on cells.

In vitro metabolism studies of nematocysts B in human liver microsomes have been carried out, providing an essential basis for the preclinical evaluation of the efficacy of this compound. Because of the chemical stability of Clemastanin B, the study can be directly used to determine the content of Clemastanin B in Isatidis Radixquinquefolium by HPLC showed that the determination of Clemastanin B content can be used as a quality control method for Isatidis Radixquinquefolium granules.

1,Study on the metabolism of straight heliotrope in B in human-derived liver microsomal incubation system

Compared with traditional liquid chromatography techniques, LC-MS/MS has the advantages of high sensitivity, high throughput, and high accuracy and is widely used in drug metabolite analysis studies. Our Pharmacokinetics Lab has passed the GLP certification by NMPA. Following the guiding principles of ICH, NMPA and FDA. The lab offers in vivo and in vitro pharmacokinetic tests according to the needs of our clients and provides them with complete sets of pharmacokinetic evaluation and optimization services.

One investigator has applied a human-derived liver microsomal incubation system to investigate the in vitro metabolism of Clemastanin B. The method involves co-incubating Clemastanin B with human liver microsomes, processing the samples by protein precipitation, and qualitative and quantitative analysis of the metabolites by LC-MS/MS. Chromatographic conditions: PhenomenexLunaC18 column (100 mm×2.0 mm, five μm); mobile phase: acetonitrile (containing 0.1% formic acid)-water (containing 0.1% formic acid), gradient elution; flow rate 400 μL-min-1; injection volume 10 μL. Mass spectrometry conditions: electrospray ionization source, negative ion mode detection.

The results revealed that straight heliotrope in B (compound 1) could be metabolized to larixenol-4-O-β-D-glucoside (compound 2) and larixenol-4′-O-β-D-glucoside (compound 3) in the human liver particulate incubation system.

Therefore, it was found that in the incubation system of human liver particles, Clemastanin B could be partially metabolized to compound 2 with more vigorous anti-influenza activity, suggesting that the anti-influenza efficacy may be exerted in vivo through both the prototype and the active metabolite, providing an essential basis for the evaluation of the effectiveness of this compound.

2,The determination of straight iron Clemastanin B content can be used as a method for quality control of Isolariciresinol

The two compounds, Clemastanin B and Isorubicin, are lignan compounds isolated in relatively large amounts from the active antiviral parts of Isatidis Radix no toginseng, and some researchers have used high-performance liquid chromatography to determine their contents, which provides a basis for the quality evaluation of Isatidis Radix no toginseng.

To establish a method for determining the content of the active antiviral components of Isatidis Radixquinquefolium granules, Gibberellin B, and Isorubicin, the researchers used high-performance liquid chromatography[2]. The results showed good linearity with peak areas in the ranges of 0.1472 μg~1.7664 μg and 0.0608 μg~0.3648 μg for Clemastanin B and idarubicin, respectively, with r of 0.9999 and 0.9991, and the average recoveries of 95.76% and 97.94% with RSD of 2.76% and 1.69%, respectively. The method is simple, sensitive, and reliable in terms of results. It can be used as a quantitative method for the quality control of Isolariciresinol by analyzing the components of straight heliotropic B and idarubicin in different batches of Isolariciresinol from other manufacturers.

Isatidis Radix no toginseng has high clinical application value and is mainly used for the treatment of viral infectious diseases and has sound preventive and therapeutic effects on influenza. In addition, it is effective in treating acute pharyngitis, chronic pharyngitis, epidemic BSE, and chickenpox. The study of the components of Isatidis Radix no toginseng that exert their medicinal effects and the analysis of the content of the active therapeutic ingredients laid the foundation for the quality of Isatidis Radix no toginseng and its modern application.

[1] In vitro metabolism study of Clemastanin B in human liver microsomes [J].

[2] Determination of Gibberellin B and Isorubicin in Isolariciresinol by HPLC [J].

0 notes

Text

Did the ancient Celts really paint themselves blue?

Part 1: Brittonic Body Paint

Clockwise from top left: participants in the Picts Vs Romans 5k, a 16th c. painting of painted and tattooed ancient Britons, Boudica: Queen of War (2023), Brave (2012).

The idea that the ancient and medieval Insular Celts painted themselves blue or tattooed themselves with woad is common in modern culture. But where did this idea come from, and is there any evidence for it? In this post, I will examine the evidence for the use of body paint among the ancient peoples of the British Isles, including both written sources and archaeology.

For this post, I am looking at sources pertaining to any ethnic group that lived in the British Isles from the late Iron Age through the early Roman Era. (Later Roman and Medieval sources will be discussed in part 2.) The relevant text sources for Brittonic body paint date from approximately 50 BCE to 100 CE. I am including all British Isles cultures, because a) determining exactly which Insular culture various writers mean by terms like ‘Briton’ is sometimes impossible and b) I don’t want to risk excluding any relevant evidence.

Written Sources:

The earliest source for our notion of blue Celts is Julius Cesar's Gallic War book 5, written circa 50 BCE. In it he says, "Omnes vero se Britanni vitro inficiunt, quod caeruleum efficit colorem, atque hoc horridiores sunt in pugna aspectu," which translates as something like, "All the Britons stain themselves with woad, which produces a bluish colouring, and makes their appearance in battle more terrible" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). Hollywood sometimes interprets this passage as meaning that the Celts used war paint, but Cesar says that all Britons colored themselves, not just the warriors. The blue coloring just had the effect (on the Romans at least) of making the Briton warriors look scary. The verb inficiunt (infinitive inficio) is sometimes translated as 'paint', but it actually means dye or stain. The Latin verb for paint is pingo (MacQuarrie 1997).

The interpretation of vitro as woad is supported by Vitruvius' statements in De Architectura (7.14.2) that vitrum is called isatis by the Greeks and can be used as a substitute for indigo. Isatis is the Greek word for woad; this is where we get its modern scientific name Isatis tinctoria. Woad and indigo both contain the same blue dye pigment, hence woad can be used as a substitute for indigo (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016). The word vitro can also mean 'glass' in Latin, but as staining yourself with glass doesn't make much sense, it's more commonly interpreted here as woad (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016, MacQuarrie 1997). I will revisit this interpretation during my discussion of the archaeological evidence.

Almost a century later in De situ orbis, Pomponius Mela says that the Britons "whether for beauty or for some other reason — they have their bodies dyed blue," (translation by Frank E. Romer) using virtually identical language to Cesar, "vitro corpora infecti" (Lib. III Cap. VI p. 63). Pomponius Mela may have copied his information from Cesar (Hoecherl 2016).

Then in 79 CE, Pliny the Elder writes in Natural History book 22 ch 2, "There is a plant in Gaul, similar to the plantago in appearance, and known there by the name of "glastum:" with it both matrons and girls among the people of Britain are in the habit of staining the body all over, when taking part in the performance of certain sacred rites; rivalling hereby the swarthy hue of the Æthiopians, they go in a state of nature." In spite of the fact that glastum means woad in the Gaulish and Celtic languages, Pliny seems to think glastum is not woad. In Natural History book 20 ch 25, he describes different plant which is almost certainly woad, a “wild lettuce” called "isatis" which is "used by dyers of wool." (Woad is a well-known source of fabric dye (Speranza et al 2020)).

Of course, "rivaling the swarthy hue of the Æthiopians" doesn't necessarily mean blue. Pliny seems to think Ethiopians literally have coal-black skin (Latin ater). Additionally, Pliny is taking about a ritual done by women, where Cesar was talking about a practice done by everyone. Are they talking about 2 different cultural practices, or is one of them reporting misinformation? Or are both wrong? Unfortunately, there is no way to know.

The Roman poets Ovid, Propertius, and Marcus Valerius Martialis all make references to blue-colored Britons (Carr 2005), but these are literary allusions, not ethnographic reports. As such, they don't really provide additional evidence that the Britons were actually dyeing or painting themselves blue (Hoecherl 2016). These poetic references merely demonstrate that the Romans believed that the Britons were.

In the sources that come after Pliny the Elder, starting in the 3rd century, there is a shift in the terms used. Instead of inficio which means to dye or stain (Hoecherl 2016), probably a temporary application of color to the surface of the skin, later sources use words like cicatrices (scars) and stigma/stigmata (brand, scar, or tattoo) (Hoecherl 2016, MacQuarrie 1997, Carr 2005) which suggest a permanent placement of pigment under the skin, i.e. a tattoo. This evidence for tattooing will be discussed in a second post.

Discussion:

Although the Romans clearly believed that the Britons were coloring themselves with blue pigment, that doesn't necessarily mean that Julius Cesar, Pomponius Mela, or Pliny the Elder are reliable sources.

In the sentence before he claims that all Britons color themselves blue, Julius Cesar says that most inland Britons "do not sow corn [aka grain], but live on milk and flesh and clothe themselves in skins." (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). This is demonstrably false. Grains like wheat and barley and storage pits for grain have been found at multiple late Iron Age sites in inland Britain (van der Veen and Jones 2006, Lightfood and Stevens 2012, Lodwick et al 2021). This false characterization of Insular Celts as uncivilized savages would continue to show up more than a millennium later in English descriptions of the Irish.

Pomponius Mela, in addition to believing in blue-dyed Britons, also believed that there was an island off the coast of Scythia inhabited by a race called the Panotii "who for clothing have big ears broad enough to go around their whole body (they are otherwise naked)" (Chorographia Bk II 3.56 translation from Romer 1998). Pliny the Elder also believed in Panotii.

15th-century depiction of a Panotii from the Nuremberg Chronicle. Was Celtic body paint as real as these guys?

The Roman historians Tacitus and Cassius Dio make no mention of body paint in their coverage of Iron Age British history (Hoecherl 2016). Their silence on the subject suggests that, in spite of Cesar's claim that all Britons colored themselves blue, the custom of body staining or painting was not actually widespread.

Considering all of these issues, is any of this information trustworthy? Based on my experience studying 16th c. Irish dress, even bigoted sources based on second-hand information often have a grain of truth somewhere in them. Unfortunately, exactly which bit is true is hard to identify without other sources of evidence, and this far in the past we don't have much.

Archaeological Evidence:

There are no known artistic depictions of face paint or body art from Great Britain during this time period. There are some Iron Age continental European coins that show what may be face painting or tattoos, but no such images have been found on British coins (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016).

In order for the Britons to have dyed themselves blue, they needed to have had blue pigment. Woad is not native to Great Britain (Speranza et al 2020), but Woad seeds have been found in a pit at the late Iron Age site of Dragonby in England, so the Britons had access to woad as a potential pigment source in Julius Cesar's time (Van der Veen et al 1993). Egyptian blue is another possible source of blue pigment. A bead made of Egyptian blue was found at a late Bronze Age site in Runnymede, England. Pieces of Egyptian blue could have been powdered to produce a pigment for body paint. (Hoecherl 2016). Egyptian blue was also used by the Romans to make blue-colored glass (Fleming 1999). Perhaps this is what Cesar meant by 'vitro'.

Potential sources of blue: Isatis tinctoria (woad) leaves and a lump of Egyptian blue from New Kingdom Egypt

Modern experiments have found that reasonably effective body paint can be made by mixing indigo powder either with water, forming a runny paint which dries on the skin, or with beef drippings, forming a grease paint which needs soap to be removed (Carr 2005, reenactor description). The second recipe is very similar to one used by modern east African argo-pastoralists which consists of ground red ocher mixed with cow fat (unpublished interview*).

Finding blue pigment on the skin of a bog body might confirm Julius Cesar's claim, but unfortunately, the results here are far from conclusive. To my knowledge, Lindow II is the only British bog body that has been tested for indigotin, the dye pigment in woad and indigo. No indigotin was found (Taylor 1986).

The late Iron Age-early Roman era bog bodies Lindown II and Lindown III show some evidence of mineral-based body paint (Joy 2009, Giles 2020). Both of them have elevated levels of calcium, aluminum, silicon, iron, and copper in their skin. Lindow III also has elevated levels of titanium. The calcium levels may simply be the result the of the bog leeching calcium from their bones. Some researchers have suggested that the other elements may be from mineral-based paints applied to the skin. The aluminum and silicon may be from clay minerals. The iron and titanium could be from red ocher. The copper could be from malachite, azurite, or Egyptian blue (CuCaSiO4), pigments that would give a green or blue color (Pyatt et al 1995, Pyatt et al 1991). These elements may have other sources however, and are not present in large enough amounts to provide definitive proof of body paint (Cowell and Craddock 1995, Giles 2020). Testing done on the early Roman Era (80-220 CE) Worsley Man has found no evidence of mineral-based paint (Giles 2020).

One final type of artifact that provides some support for Julius Cesar's claim is a group of small cosmetic grinders from late Iron Age-Roman Era Britain. These mortar and pestle sets are found almost exclusively in Great Britain and are of a style which appears to be an indigenous British development. They are distinctly different from the stone palettes used by the Romans for grinding cosmetics which suggests that these British grinders were used for a different purpose than making Roman-style makeup (Carr 2005). Archaeologist Gillian Carr has suggested that these British grinders might have been used by the Britons for grinding, mixing, and applying a woad-based body paint (Carr 2005).

Left and center: Cosmetic grinder set from Kent. Right: Cosmetic mortar from Staffordshire. images from Portable Antiquities Scheme under CC attribution license

The mortars have a variety of styles of decoration, but the pestles (top left and top center) typically feature a pointed end which could be used for applying paint to the skin (Carr 2005). The grinders are quite small, (most are less than 11 cm (4.5 in) long), making them better suited to preparing paint for drawing small designs rather than for dyeing large areas of skin (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016).

Conclusions:

Admittedly, this post is a bit off-topic, since the Irish are not mentioned, but dress history is also about what people did not wear. Hollywood has a tendency to overgeneralize and expropriate, so I want to be clear: There is no known evidence that the ancient Irish used body paint.

So, who did? For the reasons I have already discussed, I don't consider any of the Roman writers particularly trustworthy, but I think the following conclusions are plausible:

A least a few people in Great Britain dyed/stained or painted their bodies between circa 50 BCE and perhaps 100 CE, after which mentions of it end. Written sources from c. 200 CE on talk about tattoos rather than painting or staining. The custom of body dyeing/painting may have started as something practiced by everyone and later changed to something practiced by just women.

None of the writers mention any designs being painted, but Julius Cesar's description could encompass designs or solid area of color. Pliny, on the other hand, states that women were coloring their entire bodies a solid color. The dye was probably blue, although Pliny implies it was black. (I know of no plants in northern Europe that resemble plantago and produce a black dye. I think Pliny was reporting misinformation.)

Archaeological evidence and experimental recreations support the possibility that woad was the source of the pigment, but they cannot confirm it. Data from bog bodies indicate that a mineral pigment like azurite or Egyptian blue is more likely, but these samples are too small to be conclusive.

The small cosmetic grinders are suitable for making designs which might match Cesar and Mela's descriptions, but not Pliny's description of all-over body dyeing.

*Interview with a Daasanach woman I participated in while doing field school in Kenya in 2015.

Leave me a tip?

Bibliography:

Carr, Gillian. (2005). Woad, Tattooing and Identity in Later Iron Age and Early Roman Britain. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 24(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0092.2005.00236.x

Cowell, M., and Craddock, P. (1995). Addendum: Copper in the Skin of Lindow Man. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 74-75). British Museum Press.

Fleming, S. J. (1999). Roman Glass; reflections on cultural change. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Roman_Glass/ONUFZfcEkBgC?hl=en&gbpv=0

Giles, Melanie. (2020). Bog Bodies Face to face with the past. Manchester University Press, Manchester. https://library.oapen.org/viewer/web/viewer.html?file=/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/46717/9781526150196_fullhl.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Hoecherl, M. (2016). Controlling Colours: Function and Meaning of Colour in the British Iron Age. Archaeopress Publishing LTD, Oxford. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Controlling_Colours/WRteEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Joy, J. (2009). Lindow Man. British Museum Press, London. https://archive.org/details/lindowman0000joyj/mode/2up

Lightfoot, E., and Stevens, R. E. (2012). Stable Isotope Investigations of Charred Barley (Hordeum vulgare) and Wheat (Triticum spelta) Grains from Danebury Hillfort: Implications for Palaeodietary Reconstructions. Journal of Archaeological Science, 39(3), 656–662. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.10.026

Lodwick, L., Campbell, G., Crosby, V., Müldner, G. (2021). Isotopic Evidence for Changes in Cereal Production Strategies in Iron Age and Roman Britain. Environmental Archaeology, 26(1), 13-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14614103.2020.1718852

MacQuarrie, Charles. (1997). Insular Celtic tattooing: History, myth and metaphor. Etudes Celtiques, 33, 159-189. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2117

Pomponius Mela. (1998). De situ orbis libri III (F. Romer, Trans.). University of Michigan Press. (Original work published ca. 43 CE) https://topostext.org/work/145

Pyatt, F.B., Beaumont, E.H., Buckland, P.C., Lacy, D., Magilton, J.R., and Storey, D.M. (1995). Mobilization of Elements from the Bog Bodies Lindow II and III and Some Observations on Body Painting. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 62-73). British Museum Press.

Pyatt, F.B., Beaumont, E.H., Lacy, D., Magilton, J.R., and Buckland, P.C. (1991) Non isatis sed vitrum or, the colour of Lindow Man. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 10(1), 61–73. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227808912_Non_Isatis_sed_Vitrum_or_the_colour_of_Lindow_Man

Speranza, J., Miceli, N., Taviano, M.F., Ragusa, S., Kwiecień, I., Szopa, A., Ekiert, H. (2020). Isatis Tinctoria L. (Woad): A Review of Its Botany, Ethnobotanical Uses, Phytochemistry, Biological Activities, and Biotechnical Studies. Plants, 9(3): 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9030298

Taylor, G. W. (1986). Tests for Dyes. In I. Stead, J. B. Bourke and D. Brothwell (eds) Lindow Man: the Body in the Bog (p. 41). British Museum Publications Ltd.

Van der Veen, M., and Jones, G. (2006). A Re-analysis of Agricultural Production and Consumption: Implications for Understanding the British Iron Age. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 15 (3), 217–228. doi:10.1007/s00334-006-0040-3 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/27247136

Van der Veen, M., Hall, A., and May, J. (1993). Woad and the Britons painted blue. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 12(3), 367-371. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249394983

#cw anti-black racism#romano-british#period typical bigotry#iron age#bog bodies#no photographs of bog bodies though#roman era#ancient celts#celtic#woad#insular celts#anecdotes and observations#body paint#brittonic#archaeology

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

Does your rewrite give an explanation as to how clan cats in the UK know what big cats like tigers and leopards are? Personally my headcannon is that big cats are seen as mythical creatures like unicorns or dragons and that kittypets introduced the idea of these giant ultra-powerful cats to the clan cats from seeing big cats in nature documentaries from twoleg's tvs

Anon, the answer will shock you

They don't actually know what leopards, tigers, or lions are. It's a translation 'error' the same way that we treat wyrms, longs, and nagas as "dragons" when they're completely different mythological reptiles.

The three Great Clans are mythologized versions of the three groups who once lived by the ancient lake, warping over time until they were unique fantastical creatures.

Behold, a "Leopard"!

[Image ID: A blue creature in the style of a medieval manuscript. It has the head of a pike, the tail of an otter, the ears and body of a cat, with scales spotting its back and tail.]

A "leopard" is a symbol of skill, beauty, and grace. In tales of the Great Clans, leopards are often used as the heroes that must overcome the trickery of "tigers" and the brutish honesty of "lions." Sometimes they are industrious like beavers and badgers, creating large structures that "tigers" must infiltrate.

They're usually described with colors like a northern pike, in various shades of brown, green, orange, black, and white. When they're drawn, blue pigment is taken from woad (isatis tinctora) to traditionally display them as blue in contrast to lions (yellow, weld dye) and tigers (red, madder dye)

282 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stickers for Isatis

A set of stickers for Isatis! She is a very cute bean <3

#my art#furry#furry art#unapanthera art#digital art#artists on tumblr#art#furryart#commission#telegram stickers#stickers

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Blue Dress

Between the 13th and 14th centuries, the blue dye was the most widely used. Obtaining the dye is rather simple, as the ford (Isatis Tinctoria) is a plant that is easily cultivated in Europe, but the dye thus obtained will later turn out dull and greyish. The ford-dyed clothes are in fact used by the low people. Those of the nobility, on the other hand, are dyed with indigo, which is expensive and difficult to obtain, and which produces a bright, brilliant blue so that the colour holds, a fundamental requirement for a garment intended for the nobility.

In the Late Middle Ages, blue replaced royal red in the Virgin Mary's cloak, becoming a colour symbol of justice, loyalty and spirituality. In the West it then became a symbol of royalty, used by nobles and sovereigns during important ceremonies and events. In the Renaissance it was the colour used by a young woman of marriageable age. Unlike the colour pink, which is particularly expensive and considered a manly colour due to its resemblance to the colour of blood, it is blue that dominates in women's wardrobes.

House of the Dragon is no exception, as most of the female characters wear a blue dress on at least one occasion. I had already talked in my previous posts on the clothing of Helaena, Alicent and Rhaenyra about the common thread of these three characters created by the use of the colour blue (if it had been used more judiciously), but this time I want to analyse its use in the series.

In fact, I found it extremely interesting to have the three green queens (i.e. Alicent, Helaena and Jaehaera) wear it, as it seems to be a well considered and precise choice, representing a breaking point for the character and an (unfortunately traumatic) loss of innocence.

Alicent Hightower

In the first scenes with Alicent, we meet her in a dress in shades of light blue. Considering then that Rhaenyra wears a yellow dress, it almost seems that the princess represents a sun, a fixed point in Alicent's life (unfortunately the series has made them best friends), whereas Alicent's dress has the colours of a spring sky.

Blue is a predominant colour in young Alicent's wardrobe, never used again after her marriage to Viserys, where in fact she wears Targaryen red and Hightower green. Alicent wears a blue dress twice, in a darker and deeper shade than her previous dress. In the first she is in the company of Viserys, in one of their private meetings, in the second she is at the session of the small council where her marriage to Viserys is announced.

As I mentioned in her posts, I associated the colour blue with her mother (a Redwyne from Arbor) but in the series it represents her breaking point, the transition from maiden to married woman sanctioned by marriage, in which a woman transitions to the role of wife and mother (a transition well rendered in the following episode, where we find Alicent mother of Aegon and pregnant with Helaena). In fact, we will never again see Alicent wearing blue in the series.

Rhaenyra Targaryen

Yes, it seemed right to talk about her as well. Even though the message conveyed is totally the opposite. There's only one scene in which we see her wearing a blue dress (light blue actually, but I'd say we can consider blue diluted with white, come on) and it's right after Joffrey's childbirth, when Rhaenyra decides to go herself to Alicent and Viserys with the newborn.

I've noticed that many associate that dress with the colours of the Arryns (coupled, among other things, with the strong physical resemblance between Rhaenyra's actress and Aemma's), but I actually think that the blue symbolizes instead Rhaenyra's bond with the Velaryons, and consequently the one that Joffrey has (or rather, should have) with his brothers.

Rhaenyra is perfectly aware of her precarious situation. Viserys can invent all the most ridiculous excuses to justify the children's (non) resemblance to Laenor, but Alicent as well as many other people are by no means blind or stupid. Wearing that dress is therefore a clear demonstration of power, a symbol of the bond with the Velaryons and of the affiliation of Rhaenyra's children to that house.

It is a diametrically opposed message to that of Alicent, where blue is the predominant colour in her youthful clothes. Rhaenyra, on the other hand, wears it as an adult, which is a pity because we never see her in the series emphasise her kinship with the Arryn through the colours of her mother's house.

Helaena Targaryen

Like Rhaenyra, Helaena also wears a single blue dress. Incidentally, this is a moment in which she should have been one of the undisputed protagonists, since it is Aegon's coronation scene and consequently should also have been hers, being his wife.

The choice of colour is very peculiar, especially considering the context (it is the moment of greatest emphasis and demonstration of power of the greens) and the colour choices of the other family members. Helaena is also positioned next to Aemond, who is dressed in black, so the subtlety of the colour particularly stands out and stands out as a touch of light, contrasting with the sombre tones of the other characters' clothes.

I have already spoken at length in her posts about why blue is Helaena's colour, as it is the colour of her dragon Dreamfyre, but given the colour choices of her previous outfits (as a child she wears pink and green, and as an adult she has a single gold dress) dressing Helaena in blue during Aegon's coronation makes her appear out of context.

I love that they dressed her in blue, but first of all the power of the scene is interrupted by Meleys and Rhaenys and it is not clear why of all colours Helaena wears blue (a green dress would have been more appropriate). At least at first glance, becausejust as with Alicent here is Helaena's breaking point, her transition from princess to queen.

Unfortunately, the series decided not to crown her, but Helaena is the queen. A queen whose power in fact turns out to be practically nil. In the series the characterization given to Helaena seems to render her incapable of making decisions in the political sphere, where instead in the books we see her attending councils and advising Aegon. Yet, we know very well what her fate will be, when she will be forced to choose which of her children shall die, a decision that will drive her to madness. Who knows, by the way, how they will decide to dress her for that scene…

Jaehaera Targaryen

Here we enter the realm of pure speculation, but I will say right away that I love this dress. I love that Helaena has dressed her daughter in blue and I love that the embroidery and motifs on the dress resemble those on her mother's dress. I find this extremely adorable and tender.

However, my likely theory is that Jaehaera wears this dress during that scene. My heart aches already. It is one of the most horrific moments in the Dance of Dragons, where Jaehaera is threatened with rape and witnesses the murder of her brother Jaehaerys.

Exactly as with her grandmother and mother, it is a breaking moment. We don't know how Jaehaera actually reacted to what is a real trauma, but certainly losing her (probably) only parental figure of reference and her twin, then having to flee her home to save her life, coupled with the fact that your family members are literally killing each other... No wonder then that during her marriage to Aegon III she spent her days locked in her rooms.

What about the loss of innocence?

Tragedy, help. Even Jaehaerys cover seems to have the same motifs as Helaena and Jaehaera's outfits. I'm going to go cry in a corner and recover from this decidedly delusional post, I confess.

#medieval dress#hotd#house of the dragon#fire and blood#alicent hightower#helaena targaryen#jaehaera targaryen#the green queen#asoiaf#rhaenyra targaryen#the greens

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leo: "Guess what I have!"

Leo: "ClownPierce."

Clown: "An insatiable desire for blood?"

Zam: "I know ClownPierce has that!"

Leo: "An isatiable..."

Leo: "An isatiable desire for..."

Leo: "...for Zam!" [laughs]

Zam: "Yeah!"

Zam: "This is so awesome."

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lorepost: Magic Weaving

As picked in my recent poll, here is the lore dump post about magic weaving! There's more below the cut, since it's a looong post without a read more. Hope you enjoy!

Overview and energy types

The art of weaving, in basic terms, is coaxing two or more separate forms of energy to work together. While mostly used in reference to the energies known as magic, it can be applied to the combination of technology with one or more other kinds. The weaver at work will make a connection with each separate energy they intend to weave, and gently encourage each one to connect with the others internally. The difficulty depends on both the weaver’s skill, and the temperament of the particular energy they are attempting to weave.

There were six distinct types of energy in Drenius: kolnis, uhila, vaiuji, habumi, isithi and tatain. Each energy can be used in whichever way the user wishes, given enough skill, but each lends itself more easily to certain things. Kolnis tends more towards light, warmth and joy, and can be unpredictable at times. Vaiuji is more cool, calm and introspective, taking a more measured approach to things. Habumi is a rather natural, restorative energy, once considered the healer’s friend, and can be more independent than kolnis or vaiuji.

Uhila is thought of as the energy of the sky, a wild and free thing that follows its own path. It is capable of taking a visible form of its own, as seen in the beings known as Colourless. Isithi was once known as dark energy, and is the most independent of the types. While it tends not to take a recognisable form of its own, it can do so in certain conditions, and may form close bonds with members of other species. Both uhila and isithi are the most difficult to weave, but can be the most powerful once the weaver has developed a connection to them.

Tatain is considered to be the weavers’ energy, thanks to its inherent openness and adaptability. Alone, it lends itself to subtle support and minor alterations more than flashy displays. When worked into a weaving, it helps to make connections between the other energies and strengthen the resulting cast, allowing for more powerful or longer lasting effects. Unfortunately, tatain’s accepting nature meant it was more easily overpowered by the arrival of risnat.

When the dragons came, bringing their own energy with them, they took an immediate dislike to the varied types of energy already existing on Drenius. Used to their own, which they called magic, being the only kind on their own world, they tried to rein in the others and co-opt them into risnat.

In history

Weaving was once considered a common, almost essential skill for mages. While no species was entirely limited to one kind of energy, each type was more common among certain peoples. The Isati, beings known as fire spirits or flame demons by some, have always been connected with kolnis. The Tengra, semi-aquatic people from the western continent, are similarly linked to vaiuji. Habumi and uhila are more intrinsic to the southern continent, linked to the Diyrae and Colourless respectively.

Of the two remaining types, only tatain is historically linked to any particular race. It was once considered the native energy of humankind. It is also highly useful as a base for weaving, being a very accepting and cooperative energy. Isithi, more commonly known as shadow magic, tends to stand alone, only working with those it takes a liking to. It is extremely averse to risnat, the seventh energy that arrived with the dragons.

In the days when many people were capable of weaving, there were also closer connections between the peoples of the world, at least partly because cooperation was needed for a greater understanding of their energies. When the western continent sank during the Great Melting, the Tengra in particular relied on the skill of weavers to rebuild their homes and adapt to their new situation.

Weaving changed when risnat was pushed onto humans, overriding their natural affinity with tatain and forcing them into the more rigid structure of dragon magic. With many skilled tatain practitioners now unable to weave, connections between energy types withered and failed, separating the different races once more.

Present day

Currently, weaving is a rare thing only truly practised by hybrids. With the near total loss of human mages in Trizes during the Exodus, much of their knowledge about weaving was also taken to Slokos, leaving those remaining in Trizes with little to work from. Hybrids themselves are also highly uncommon, and often separated from part of their heritage by one parent or the other.

Those few who do manage to avoid the constraints of risnat are often hounded by the dragons, who dislike any so-called ‘contamination of magic’ by other energies. The general draconic opinion (barring a handful of exceptions) is that all magic should be under their control, ie risnat. They have little understanding of other kinds, and have worked to block or otherwise suppress it in other species.

One of the few species still practising weaving as a common thing is the Li Buqu of Slokos. Since humans had their ties with tatain broken, the Li Buqu are the only ones who remain naturally attuned to it. Their way of defining magic is different to that of the Isati, whose language granted the energy types their names. As the Li Buqu’s natural energy is tatain, they are able to easily connect with and weave other kinds. Most of them feel no need to label the type of energy they use, as all of it seems normal to them.

The bahambi are more familiar with the energies of Drenius, and have attempted to throw off the dragons’ control. Recent events across the world have loosened the bindings over tatain in particular, and this has enabled more to begin weaving again. Time will tell if this also leads to closer relations between the races, as it did in the past.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

some fanart for @starrletnight’s sky x pressure artwork! It’s all really cute (and singlehandedly booted me back into my SCotL fixation)

Seems like someone’s watching…

And a ref for the skykid I’m throwing in! Their name is Isati- they’ve got a lute that I didn’t bother drawing yet and a makeshift spear in some rebar they were able to find in one of the more ruined parts of the Blacksite. It’s useless against most of the hazards down there but it makes them feel a bit better about things.

#my art#roblox pressure#pressure roblox#sky children of the light#s: cotl#skycotl#sky x pressure#thatskygame#i love sparrow and moth sm

192 notes

·

View notes

Video

n578_w1150 by Biodiversity Heritage Library

Via Flickr:

English botany, or, Coloured figures of British plants / London :R. Hardwicke,1863-1886. biodiversitylibrary.org/page/32601386

#Great Britain#Pictorial works#Plants#University Library#University of Illinois Urbana Champaign#bhl:page=32601386#dc:identifier=https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/32601386#flickr#botanical illustration#scientific illustration#dyer's woad#isatis tinctoria#woad#glastum#Asp of Jerusale

1 note

·

View note

Text

I – Isatis tinctoria L. – Guado (Brassicaceae)

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

9 and 12

wip ask game

🤔What’s a story you’d love to write but haven’t even started yet?

more stuff for my lonely!jon and eye!martin au. jons domain, mostly. i dont have strong enough ideas for what itd be like yet though.

for more isaty stuff i have a lot of osis stuff rattling in my brain that i havent started yet. kingquest..... the scene from it. you know the one.

❤️Not a question, just a second kudos to send.

thank you :}

6 notes

·

View notes