#insular celts

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Did the ancient Celts really paint themselves blue?

Part 2: Irish tattoos

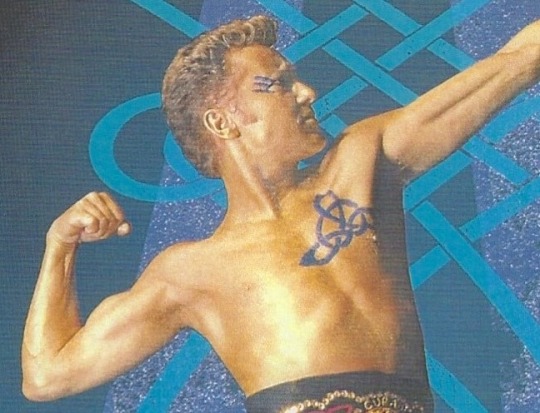

Clockwise from top left: Deirdre and Naoise from the Ulster Cycle by amylouioc, detail from The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife by Daniel Maclise, a modern Celtic revival tattoo, Michael Flatley in a promotional image for the Irish step dance show 'Lord of the Dance'

This is my second post exploring the historical evidence for our modern belief that the ancient and medieval Insular Celts painted or tattooed themselves with blue pigment. In the first post, I discussed the fact that body paint seems to have been used by residents of Great Britain between approximately 50 BCE to 100 CE. In this post, I will examine the evidence for tattooing.

Once again, I am looking at sources pertaining to any ethnic group who lived in the British Isles, this time from the Roman Era to the early Middle Ages. The relevant text sources range from approximately 200 CE to 900 CE. I am including all British Isles cultures, because a) determining exactly which Insular culture various writers mean by terms like ‘Briton’, ‘Scot’, and ‘Pict’ is sometimes impossible and b) I don’t want to risk excluding any relevant evidence.

Continental Written Sources:

The earliest written source to mention tattoos in the British Isles is Herodian of Antioch’s History of the Roman Empire written circa 208 CE. In it, Herodian says of the Britons, "They tattoo their bodies with colored designs and drawings of all kinds of animals; for this reason they do not wear clothes, which would conceal the decorations on their bodies" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). Herodian is probably reporting second-hand information given to him by soldiers who fought under Septimius Severus in Britain (MacQuarrie 1997) and shouldn't be considered a true primary source.

Also in the early 3rd century, Gaius Julius Solinus says in Collectanea Rerum Memorabilium 22.12, "regionem [Brittaniae] partim tenent barbari, quibus per artifices plagarum figuras iam inde a pueris variae animalium effigies incorporantur, inscriptisque visceribus hominis incremento pigmenti notae crescunt: nec quicquam mage patientiae loco nationes ferae ducunt, quam ut per memores cicatrices plurimum fuci artus bibant."

Translation: "The area [of Britain] is partly occupied by barbarians on whose bodies, from their childhood upwards, various forms of living creatures are represented by means of cunningly wrought marks: and when the flesh of the person has been deeply branded, then the marks of the pigment get larger as the man grows, and the barbaric nations regard it as the highest pitch of endurance to allow their limbs to drink in as much of the dye as possible through the scars which record this" (from MacQuarrie 1997).

This passage, like Herodian's, is clearly a description of tattooing, not body staining or painting. That said, I have no idea of tattoos actually work like this. I would think this would result in the adult having a faded, indistinct tattoo, but if anyone knows otherwise, please tell me.

The poet Claudian, writing in the early 5th c., is the first to specifically mention the Picts having tattoos (MacQuarrie 1997). In De Bello Gothico he says, "Venit & extremis legio praetenta Britannis,/ Quæ Scoto dat frena truci, ferroque notatas/ Perlegit exanimes Picto moriente figuras."

Translation: "The legion comes to make a trial of the most remote parts of Britain where it subdues the wild Scot and gazes on the iron-wrought figures on the face of the dying Pict" (from MacQuarrie 1997).

Last, and possibly least, of our Mediterranean sources is Isidore of Seville. In the early 7th c. he writes, "the Pictish race, their name derived from their body, which the efficient needle, with minute punctures, rubs in the juices squeezed from native plants so that it may bring these scars to its own fashion [. . .] The Scotti have their name from their own language by reason of [their] painted body, because they are marked by iron needles with dark coloring in the form of a marking of varying shapes." (translation from MacQuarrie 1997)

Isidore is the earliest writer to explicitly link the name 'Pict' to their 'painted' (Latin: pictus) i.e. tattooed bodies. Isidore probably borrowed information for his description from earlier writers like Claudian (MacQuarrie 1997).

In the 8th century, we have a source that definitely isn't Romans recycling old hearsay. In 786, a pair of papal legates visited the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria (Story 1995). In their report to Pope Hadrian, the legates condemn pagans who have "superimposed most hideous cicatrices" (i.e gotten tattoos), likening the pagan practice to coloring oneself "with dirty spots". The location of the visit indicates that these are Anglo-Saxon tattoos rather than Celtic, but some scholars have suggested that the Anglo-Saxons might have adopted the practice from the Brittonic Celts (MacQuarrie 1997).

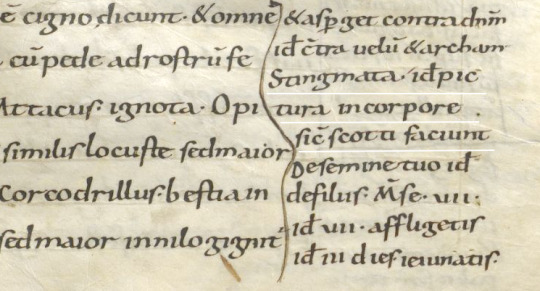

A gloss in the margin of the late 9th c. German manuscript Fulda Aa 2 defines Stingmata [sic] as "put pictures on the bodies as the Irish (Scotti) do." (translation from MacQuarrie 1997).

Fulda Aa 2 folio 43r The gloss is on the left underlined in white.

Irish Written Sources:

Irish texts that mention tattoos date to approximately 700-900 CE, although some of them have glosses that may be slightly later, and some of them cannot be precisely dated.

The first text source is a poem known in English as "The Caldron of Poesy," written in the early 8th c. (Breatnach 1981). The poem is purportedly the work of Amairgen, ollamh of the legendary Milesian kings. In the first stanza of the poem, he introduces himself saying, "I being white-kneed, blue-shanked, grey-bearded Amairgen." (translation from Breatnach 1981)

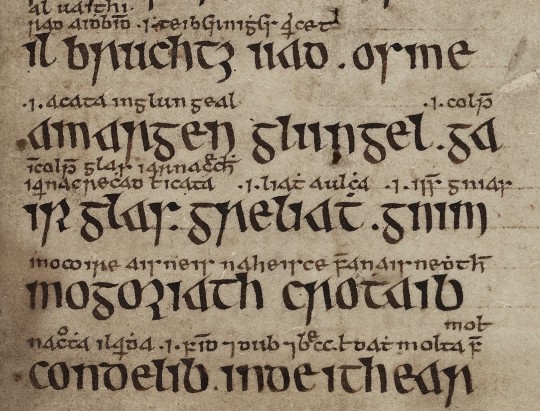

The text of the poem with interline glosses from Trinity College Dublin MS 1337/1

The word garrglas (blue-shanked) has a Middle Irish (c. 900-1200) gloss added by a later scribe, defining garrglas as: "a tattooed shank, or who has the blue tattooed shank" (Breatnach 1981).

Although Amairgen was a mythical figure, the position ollamh was not. An ollamh was the highest rank of poet in medieval Ireland, considered worthy of the same honor-price as a king (Carey 1997, Breatnach 1981). The fact that a man of such esteemed status introduces himself with the descriptor 'blue-shanked' suggests that tattoos were a respectable thing to have in early medieval Ireland.

The leg tattoos are also mentioned c. 900 CE in Cormac’s Glossary. It defines feirenn as "a thong which is about the calf of a man whence ‘a tattooed thong is tattooed about [the] calf’" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997)

The Irish legal text Uraicecht Becc, dated to the 9th or early 10th c., includes the word creccoire on a list of low-status occupations (Szacillo 2012, MacNeill 1924). A gloss defines it as: crechad glass ar na roscaib, a phrase which Szacillo interprets as meaning "making grey-blue sore (tattooing) on the eyes" (2012). This sounds rather strange, but another early Irish text clarifies it.

The Vita sancti Colmani abbatis de Land Elo written around the 8th-9th centuries (Szacillo 2012) contains the following episode:

On another time, St Colmán, looking upon his brother, who was the son of Beugne, saw that the lids of his eyes had been secretly painted with the hyacinth colour, as it was in the custom; and it was a great offence at St Colmán’s. He said to his brother: ‘May your eyes not see the light in your life (any more). And from that hour he was blind, seeing nothing until (his) death. (translation from Szacillo 2012).

The original Latin phrase describing what so offended St Colmán "palpebre oculorum illius latenter iacinto colore" does not contain the verb paint (pingo). It just says his eyelids were hyacinth (blue) colored. This passage together with the gloss from the Uraicecht Becc implies that there was a custom of tattooing people's eyelids blue in early medieval Ireland. A creccoire* was therefore a professional eyelid tattooer or a tattoo artist.

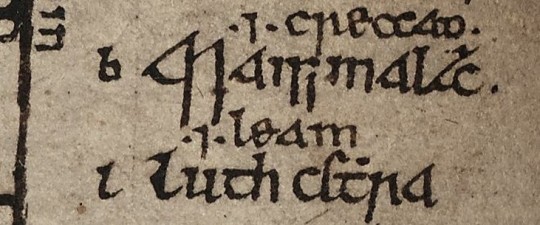

A possible third reference to tattooing the area around the eye is found in a list of Old Irish kennings. The kenning for the letter 'B' translates as 'Beauty of the eyebrow.' This kenning is glossed with the word crecad/creccad (McManus 1988). Crecad could be translated as cauterizing, branding, or tattooing (eDIL). McManus suggests "adornment (by tattooing) of the eyebrow" as a plausible interpretation of how crecad relates to the beauty of the eyebrow (1988). The precise date of this text is not known (McManus 1988), but Old Irish was used c. 600-900 CE, meaning this text is of a similar date to the other Irish references to tattoos.

Kenning of the letter 'b' with gloss from TCD MS 1337/1

There is a sharp contrast between the association of tattoos with a venerated figure in 'The Caldron of Poesy', and their association with low-status work and divine punishment in the Uraicecht Becc and the Vita. This indicates that there was a shift in the cultural attitude towards tattoos in Ireland during the 7th-9th centuries. The fact that a Christian saint considered getting tattoos a big enough offense to punish his own brother with blindness suggests that tattooing might have been a pagan practice which gradually got pushed out by the Catholic Church. This timeline is consistent with the 786 CE report of the papal legates condemning the pagan practice of tattooing in Great Britain (MacQuarrie 1997).

There are some mentions of tattooing in Lebor Gabála Érenn, but the information largely appears to be borrowed from Isidore of Seville (MacQuarrie 1997). The fact that the writers of LGE just regurgitated Isidore's meager descriptions of Pictish and Scottish (ie Irish) tattooing without adding any details, such as the designs used or which parts of the body were tattooed, makes me think that Insular tattooing practices had passed out of living memory by the time the book was written in the 11th century.

*There is some etymological controversy over this term. Some have suggested that the Old Irish word for eyelid-tattooer should actually be crechaire. more info Even if this hypothesis is correct, and the scribe who wrote the gloss on creccoire mistook it for crechaire, this doesn't contradict my argument. The scribe clearly believed that eyelid-tattooer belonged on a list of low-status occupations.

Discussion:

Like Julius Cesar in the last post, Herodian of Antioch c. 208 CE makes some dubious claims of Celtic barbarism, stating that the Britons were: "Strangers to clothing, the Britons wear ornaments of iron at their waists and throats; considering iron a symbol of wealth, they value this metal as other barbarians value gold" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). If the Britons wore nothing but iron jewelry, then why did they have brass torcs and 5,000 objects that look like they're meant to attach to fabric, Herodian?

Brass torc from Lochar Moss, Scotland c. 50-200 CE. Romano-British trumpet brooch from Cumbria c. 75-175 CE. image from the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

Trumpet brooches are a Roman Era artifact invented in Britain, that were probably pinned to people's clothing. more info

Although Herodian and Solinus both make dubious claims, there are enough differences between them to indicate that they had 2 separate sources of information, and one was not just parroting the other. This combined with the fact that we have more-reliable sources from later centuries confirming the existence of tattoos in the British Isles makes it probable that there was at least a grain of truth to their claims of tattooing.

There is a common belief that the name Pict originated from the Latin pictus (painted), because the Picts had 'painted' or tattooed bodies. The Romans first used the name Pict to refer to inhabitants of Britain in 297 CE (Ware 2021), but the first mention of Pictish tattoos came in 402 CE (Carr 2005), and the first explicit statement that the name Pict was derived from the Picts' tattooed bodies came from Isidore of Seville c. 600 CE (MacQuarrie 1997). Unless someone can find an earlier source for this alleged etymology than Isidore, I am extremely skeptical of it.

Summary of the written evidence:

Some time between c. 79 CE (Pliny the Elder) and c. 208 CE (Herodian of Antioch) the practice of body art in Great Britain changed from staining or painting the skin to tattooing. Third century Celtic Briton tattoo designs depicted animals. Pictish tattoos are first mentioned in the 5th century.

The earliest mention of Irish tattoos comes from Isidore of Seville in the early 6th c., but since it seems to have been a pre-Christian practice, it likely started earlier. Irish tattoos of the 8-9th centuries were placed on the area around the eye and on the legs. They were a bluish color. The 8th c. Anglo-Saxons also had tattoos.

Tattooing in Ireland probably ended by the early 10th c., possibly because of Christian condemnation. Exactly when tattooing ended in Great Britain is unclear, but in the 12th c., William of Malmesbury describes it as a thing of the past (MacQuarrie 1997). None of these sources give much detail as to what the tattoos looked like.

The Archaeology of Insular Ink:

In spite of the fact that tattooing was a longer-lasting, more wide-spread practice in the British Isles than body painting, there is less archaeological evidence for it. This may be because the common tools used for tattooing, needles or blades for puncturing the skin, pigments to make the ink, and dishes to hold the ink, all had other common uses in the Middle Ages that could make an archaeologist overlook their use in tattooing. The same needle that was used to sew a tunic could also have been used to tattoo a leg (Carr 2005). A group of small, toothed bronze plates from a Romano-British site at Chalton, Hampshire might have been tattoo chisels (Carr 2005) or they might have been used to make stitching holes in leather (Cunliffe 1977).

Although the pigment used to make tattoos may be difficult to identify at archaeological sites, other lines of evidence might give us an idea of what it was. Although the written sources tell us that Irish tattoos were blue, the popular modern belief that woad was the source of the tattoo pigment is, in my opinion, extremely unlikely for a couple of reasons:

1) Blue pigment from woad doesn't seem to work as tattoo ink. The modern tattoo artists who have tried to use it have found that it burns out of the person's skin, leaving a scar with no trace of blue in it (Lambert 2004).

2) None of the historical sources actually mention tattooing with woad. Julius Cesar and Pliny the Elder mention something that might have been woad, but they were talking about body paint, not tattoos. (see previous post) Isidore of Seville claimed that the Picts were tattooing themselves with "juices squeezed from native plants", but even assuming that Isidore is a reliable source, you can't get blue from woad by just squeezing the juice out of it. In order to get blue out of woad, you have to first steep the leaves, then discard the leaves and add a base like ammonia to the vat (Carr 2005). The resulting dye vat is not something any knowledgeable person would describe as plant juice, so either Isidore had no idea what he was talking about, or he is talking about something other than blue pigment from woad.

In my opinion, the most likely pigment for early Irish and British tattoos is charcoal. Early tattoos found on mummies from Europe and Siberia all contain charcoal and no other colored pigment. These tattoos range in date from c. 3300 BCE (Ötzi the Iceman) to c. 300 CE (Oglakhty grave 4) (Samadelli et al 2015, Pankova 2013).

Despite the fact that charcoal is black, it tends to look blueish when used in tattoos (Pankova 2013). Even modern black ink tattoos that use carbon black pigment (which is effectively a purer form of charcoal) tend to look increasingly blue as they age.

A 17-year-old tattoo in carbon black ink photographed with a swatch of black Sharpie on white printer paper.

The fact that charcoal-based tattoo inks continue to be used today, more than 5,000 years after the first charcoal tattoo was given, shows that charcoal is an effective, relatively safe tattoo pigment, unlike woad. Additionally, charcoal can be easily produced with wood fires, meaning it would have been a readily available material for tattoo artists in the early medieval British Isles. We would need more direct evidence, like a tattooed body from the British Isles, to confirm its use though.

As of June 2024, there have been at least 279 bog bodies* found in the British Isles (Ó Floinn 1995, Turner 1995, Cowie, Picken, Wallace 2011, Giles 2020, BBC 2024), a handful of which have made it into modern museum collections. Unfortunately, tattoos have not been found on any of them. (We don't have a full scientific analysis for the 2023 Bellaghy find yet though.)

*This number includes some finds from fens. It does not include the Cladh Hallan composite mummies.

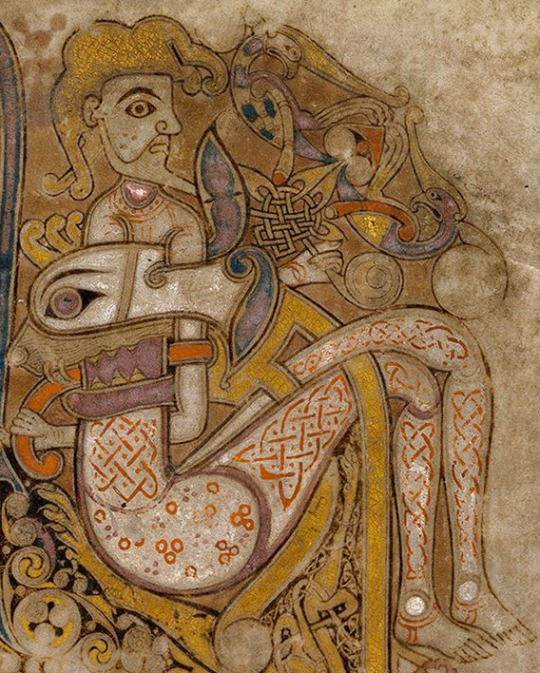

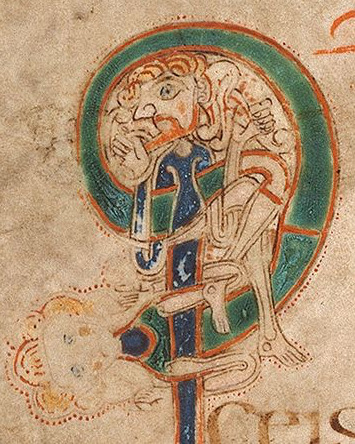

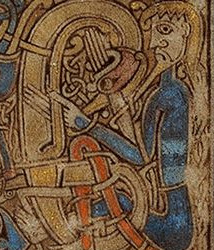

Tattoos in period art?

It has been suggested that the man fight a beast on Book of Kells f. 130r may be naked and covered in tattoos (MacQuarrie 1997). However, Dress in Ireland author Mairead Dunlevy interprets this illustration as a man wearing a jacket and trews (Dunlevy 1989). Looking at some of the other figures in the Book of Kells, I agree with Dunlevy. F. 97v shows the same long, fitted sleeves and round neckline. F. 292r has long, fitted leg coverings, presumably trews, and also long sleeves. The interlace and dot motifs on f. 130r's legs may be embroidery. Embroidered garments were a status symbol in early medieval Ireland (Dunlevy 1989).

Left to right: Book of Kells folios 130r, 97v, 292r

A couple of sculptures in County Fermanagh might sport depictions of Irish tattoos. The first, known as the Bishop stone, is in the Killadeas cemetery. It features a carved head with 2 marks on the left side of the face, a double line beside the mouth and a single line below the eye. These lines may represent tattoos.

The second sculpture is the Janus figure on Boa Island. (So named because it has 2 faces; it's not Roman.) It has marks under the right eye and extending from the corner of the left eye that may be tattoos.

I cannot find a definitive date for the Bishop stone head, but it bears a strong resemblance to the nearby White Island church figures. The White Island figures are stylistically dated to the 9th-10th centuries and may come from a church that was destroyed by Vikings in 837 CE (Halpin and Newman 2006, Lowry-Corry 1959). The Janus figure is believed to be Iron Age or early medieval (Halpin and Newman 2006).

Conclusions:

Despite the fact that tattooing as a custom in the British Isles lasted for more than 500 years and was practiced by at least 3 different cultures, written sources remain our only solid evidence for it. With only a dozen sources, some of which probably copied each other, to cover this time span, there are huge gaps in our knowledge. The 4th century Picts may not have had the same tattoo designs, placements or reasons for getting tattooed as the 8th c. Irish or Anglo-Saxons. These sources only give us fragments of information on who got tattooed, where the tattoos were placed, what they looked like, how the tattoos were done, and why people got tattooed. Further complicating our limited information is the fact that most of the text sources come from foreigners and/or people who were prejudiced against tattooing, which calls their accuracy into question.

'The Cauldron of Posey' is one source that provides some detail while not showing prejudice against tattoos. The author of the poem was probably Christian, but the poem appears to have been written at a time when Pagan practices were still tolerated in Ireland. I have a complete translation of the poem along with a longer discussion of religious elements here.

Leave me a tip?

Bibliography:

BBC (2024). Bellaghy bog body: Human remains are 2,000 years old https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-68092307

Breatnach, L. (1981). The Cauldron of Poesy. Ériu, 32(1981), 45-93. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007454

Carey, J. (1997). The Three Things Required of a Poet. Ériu, 48(1997), 41-58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007956

Carr, Gillian. (2005). Woad, Tattooing and Identity in Later Iron Age and Early Roman Britain. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 24(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0092.2005.00236.x

Cowie, T., Pickin, J. and Wallace, T. (2011). Bog bodies from Scotland: old finds, new records. Journal of Wetland Archaeology 10(1): 1–45.

Cunliffe, B. (1977) The Romano-British Village at Chalton, Hants. Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club and Archaeological Society, 33(1977), 45-67.

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

eDIL s.v. crechad https://dil.ie/12794

Giles, Melanie. (2020). Bog Bodies Face to face with the past. Manchester University Press, Manchester. https://library.oapen.org/viewer/web/viewer.html?file=/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/46717/9781526150196_fullhl.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Halpin, A., Newman, C. (2006). Ireland: An Oxford Archaeological Guide to Sites from Earliest Times to AD 1600. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://archive.org/details/irelandoxfordarc0000halp/page/n3/mode/2up

Hoecherl, M. (2016). Controlling Colours: Function and Meaning of Colour in the British Iron Age. Archaeopress Publishing LTD, Oxford. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Controlling_Colours/WRteEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Lambert, S. K. (2004). The Problem of the Woad. Dunsgathan.net. https://dunsgathan.net/essays/woad.htm

Lowry-Corry, D. (1959). A Newly Discovered Statue at the Church on White Island, County Fermanagh. Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 22(1959), 59-66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20567530

MacQuarrie, Charles. (1997). Insular Celtic tattooing: History, myth and metaphor. Etudes Celtiques, 33, 159-189. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2117

McManus, D. (1988). Irish Letter-Names and Their Kennings. Ériu, 39(1988), 127-168. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30024135

Ó Floinn, R. (1995). Recent research into Irish bog bodies. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 137–45). British Museum Press, London. ISBN: 9780714123059

Pankova, S. (2013). One More Culture with Ancient Tattoo Tradition in Southern Siberia: Tattoos on a Mummy from the Oglakhty Burial Ground, 3rd-4th century AD. Zurich Studies in Archaeology, 9(2013), 75-86.

Samadelli, M., Melisc, M., Miccolic, M., Vigld, E.E., Zinka, A.R. (2015). Complete mapping of the tattoos of the 5300-year-old Tyrolean Iceman. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 16(2015), 753–758.

Story, Joanna (1995). Charlemagne and Northumbria : the in

fluence of Francia on Northumbrian politics in the later eighth and early ninth centuries. [Doctoral Thesis]. Durham University. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1460/

Szacillo, J. (2012). Irish hagiography and its dating: a study of the O'Donohue group of Irish saints' lives. [Doctoral Thesis]. Queen's University Belfast.

Turner, R.C. (1995). Resent Research into British Bog Bodies. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 221–34). British Museum Press, London. ISBN: 9780714123059

Ware, C. (2021). A Literary Commentary on Panegyrici Latini VI(7) An Oration Delivered Before the Emperor Constantine in Trier, ca. AD 310. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_Literary_Commentary_on_Panegyrici_Lati/oEwMEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

#early medieval#roman era#pict#tattoos#ancient celts#apologies to people who wanted a shorter post#archaeology#art#anecdotes and observations#statutes and laws#irish history#gaelic ireland#medieval ireland#anglo saxon#insular celts#romano british

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also cause it might be confusing when people talk about it, there are two types of Celtic language groups and these are Gaelic and Brythonic. Gaelic languages are Irish, Scottish and Manx (from the Isle of Man) while Brythonic languages are Welsh, Cornish (from Cornwall) and Breton (from Brittany). So while saying irish is a Gaelic language is correct, the language isn’t called Gaelic and the word is more equivalent to calling something a Romance language. Like if someone was speaking French you wouldn’t say they were speaking romance but you could say that they’re speaking a Romance language. Although unless you were having a discussion about language groups it’d be a pretty strange way to refer to it, so normally you just call it French and the same should be done with Irish

Saying this as an Irish person since the new Hozier album just came out and there are lyrics in Irish; it’s Irish or Gaeilge (pronounced “gwhale-ga” or “gale-ga” depending on region), not Gaelic or Celtic or any other name people come up with.

It’s just a normal language that people speak in their everyday life. We learn it in school in the republic. People like myself are bilingual in Irish and English. It’s not a “fairy aesthetic cottage core leprechaun” language.

Please respect it. Our language is a touchy subject seen as how England tried to erase it by forcing English on us and severely punishing those who spoke Irish.

At the same time that does NOT mean it is a dead language. Our road and safety signs are in both Irish and English, same with legal documents. Our politicians speak it, and we are trying to preserve the language!

Anyways enjoy the album!

#Scottish not to be confused with Scots btw they’re two different languages#celtic groups are mainly defined by languages today#and the 6 mentioned above are the insular Celtic groups and are considered the official ones#although there are other groups mainly through Spain and Portugal which have strong Celtic cultures#and by many are considered Celtic although they’re not insular celts#there used to be 16 Celtic languages I believe so there’s lots of little groups dotted around with strong Celtic ties

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

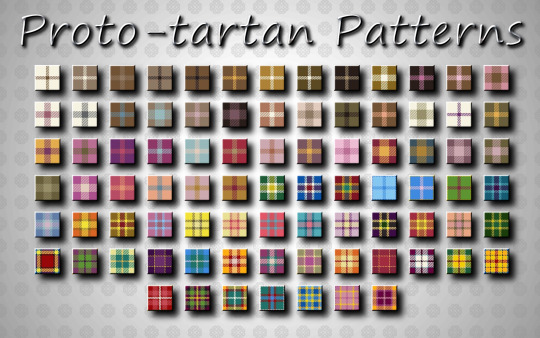

Proto-tartan Patterns

Once my new colour palettes were ready, I could finally move to the thing which prompted their remake in the first place: meaning, a total overhaul of the tartan(-esque?) swatches I use for recolouring stuff.

Remember my old set of tartan patterns? I've been gradually getting less and less happy with them. Sure, they were pretty, no doubt - a little bit too pretty. Kind of complex. Kind of time-consuming to make. Kind of... not screaming 'iron age'. And not at all consistent with the colour palette I was using at the time. So I decided to remake them.

Completely. From scratch.

This time I wanted to be smarter. This time I had a vision. And a plan.

Hear me out.

(or just DOWNLOAD them from my Patreon - as always all free from day one - if you don't feel like reading this dissertation; why does it always get so long ffs...)

So the thing is - we don't know much about how pre-Roman Britons dressed. They left no written records and, as their textiles were, obviously, organic, they decomposed long ago, so archaeology is of little help as well. However, there's one thing we do know, as all ancient writers agree on it: namely, that their clothing was strikingly 'colourful'. Considering Romans themselves had better access to vibrant dyes and textiles, that probably wasn't it; and so it's a truth universally acknowledged (or at least believed) that said 'colourfulness' was a result of insular Celts using multi-coloured patterns, as opposed to Roman monochrome style. How exactly those patterns looked, we have no way of knowing. Some interpret it simply as stripes; others as some chequered patterns; and others dare to call it proto-tartan. I went with the last one.

Trying to come up with swatches which would make sense for those times was a tricky task - you know? Because on the one hand, I didn't want them to be obviously anachronistic; and imagining a life of a Brittonic commoner woman, I could see that she'd have no time and energy left to make literally any of my old tartan swatches. What would a farmer's wife wear? She'd be making her clothes herself, of course - so what would she go for? Something simple, not that time-consuming, not requiring too much concentration. Maybe two shades of natural wool; maybe dyeing some skeins of white wool some easily accessible colour; maaaybe two dyed colours, if she liked to dress up. But dyeing her wool ten different colours and then weaving them into beautiful, perfectly symmetrical patterns, like the ones from my old set? I think not.

Then again, we have that ugly tendency of assuming people in the past were somehow 'lower' then us, especially when it's about illiterate societies. Yet every now and then archaeologists find old textiles which miraculously survived millennia, and time and time again we're flabbergasted by how intricate they are, how well-made, how fine, how... Damn expensive. I have no reason to believe it was any different in case of ancient Britons. Whatever a Celtic chieftess wore, she surely wasn't running around in a potato sack; and considering Roman officials would probably interact mostly with the richer members of the society, it makes sense that their 'wooooow, so colourful' comments were inspired mostly by those upper-class garments.

And so I decided to invent and implement a kind of class-stratification system, i.e. different pattern rules for different social classes. Totally arbitrary, totally made up, totally not backed by any sources - just a simple product of the time I spent wondering 'what would've made sense'. Oh, and this time all the colours come from my new palette(s), so it's all consistent. I found an online tartan maker and got to work.

See? I told you I had a plan.

The free version of the tartan maker let me mix maximum of 5 colours and I happily agreed to this limit, basing the bulk of my rigid social classes' system exactly on this: the number of colours used. Their provenience also played a role. And of course I went for the holy number of 85 swatches - divided into five groups:

Group I - lower class casual dress. Five patterns only in undyed wool, 20 patterns in one shade of undyed wool + one dyed colour. Altogether 25 swatches;

Group II - lower class fancy dress & middle class casual dress. Two dyed colours, only from the northern palette. 20 swatches;

Group III - middle class fancy dress & upper class casual dress. Three colours, whichever, including the imported ones, with the exception of Roman luxury dyes (kermes, turmeric, saffron, Tyrian purple). Again 20 swatches;

Group IV - upper class fancy dress. Four colours, whichever, even the luxury ones. I guess not too many sims could land so high on top, so it's only 10 swatches;

Group V - aka 'when you're the chief of the most powerful tribe on the isle and you've conquered anything of value so you're basically a king'. Five colours, whichever, most swatches with heavy emphasis on the luxury dyes. Another 10 swatches.

Here you can see the difference visualised on a dress I'm currently working on (don't pay too close attention to alignment and such, it's still a wip). For example, a progression of different purple & yellow combos:

See the difference? We went all the way from birch mixed with elderberry to Tyrian purple mixed with saffron. (Which, btw... Can you get any posher than that???)

Or the progression of reds and yellows. The last swatch looks almost like the first one from the old set (yup, I took lots of inspiration from it when I was struggling to design those 4 or 5 colour combos):

And here another swatch from group V, just because I love it. Perfect for a sim who's rich and not afraid to show it:

That's woad, kermes, saffron and turmeric you're seeing here. In your face peasants.

So. That was a very long post about a very niche thing that probably not many people care about 😅 But if you, dear gentle reader, do care and think you might find those patterns useful, grab that 7z package and enjoy! (download link, in case you missed it, HERE).

PS. They're all 64x64, so you should be able to safely use them as swatches' thumbnails too!

PS2. And of course they're seamless. That felt too obvious to need mentioning ;)

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you give an overview of your conworld and language for new people?

Absolutely! :D

The World

The setting I write in (hereafter "Boralverse") is an alternate history of Earth. The original difference from our own history (hereafter "IRL") is the existence of the island of Borland (Istr Boral) between Great Britain and Denmark, inspired by the IRL existence of Doggerland.

The human pre-classical history of Borland can be summarised as:

With sea level rise about 8k years ago, Borland was cut off from the continent and from Britain (this is when Doggerland was submerged IRL); some Stone Age people remain. They leave some monuments—burial mounds, the Çadrosc labyrinth—and were farmers, but they had no writing or ironworking.

The Celts arrive in Borland shortly before they settle Britain in the second millennium BCE, taking up iron tools and establishing many tribal groups. Due to some later migration from Britain to Borland, they speak a language (Borland Celtic) which is most closely related to Proto-Brythonic.

I assume that as far as possible the history of the rest of the world is indistinguishable from the IRL history up to this point. I continue to do so while the Romans invade and settle Borland shortly after Britain, despite conceding to credulity and allowing a few classical references:

...in Ptolemy's description of the Pritannoi we can understand he referred to the Insular Kelts of Ireland, Britain and Borland as a whole... ...contrasting Hadrian's policies in Britain and in Borland is vital for understanding their different fates in the post-Classical age...

where I admit that the Roman Empire having an entire additional province should probably have some observable effects.

Once the Western Roman Empire collapses, I start properly diverging Boralverse history from IRL history. This begins with a different pattern of Anglo-Saxon migration; the two petty kingdoms of Angland and Southbar arise in western Borland, while the settlement of England proceeds slightly slower than IRL.

Historical divergence spreads through western Europe over the next few centuries, and by 1000 CE things are beginning to go off the rails all across Eurasia and North Africa. I leave the history of the Americas the same until Old World contact (via Basque fishermen stumbling across Newfoundland in 1470 CE), and likewise with Australia.

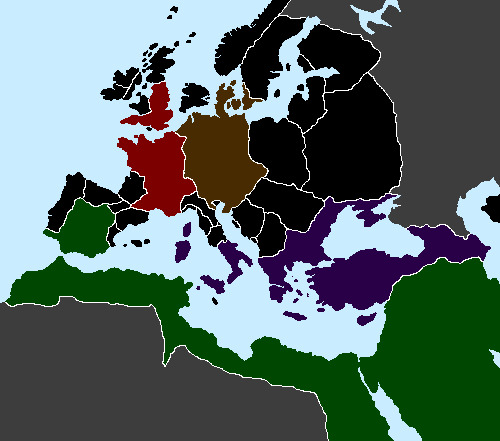

The map below shows Europe in 1120, during the Second Tetrarchy Period. At this time, Europe was unusually centralised, with four great empires: the First Drengot Empire (red), the German Empire (brown), the Second Roman Empire (purple) and the Single Caliphate (green).

In the modern era, my hope is that the Boralverse world feels fractally uncanny; at every scale something is unexpectedly different, from political borders and languages to fashion and pop culture references.

For clarity, I employ an inconsistent Translation Convention when writing from a Boralverse perspective, mostly using IRL English but peppering in calques of Boralverse English jargon for flavour, such as threshold force "nuclear power" or jalick "garment socially equivalent to a tuxedo".

The Language

The original motivation for this alternate history setting is Borlish (Borallesc), the Romance language spoken on Borland.

It picked up a few Borland Celtic loanwords from the existing population at the time of the conquest (macquar ~ Welsh magu "raise, rear"; vrug ~ Welsh grug "heather"), but was much more influenced through the first millennium by Anglo-Saxon settlement and then Norse conquest during the Viking Age. The following is an example of late Old Borlish (ca. 1240):

…sovravnt il deft nostre saȝntaðesem eð atavalesem n iȝ atrevre golfhavn seȝ hamar dont y verb divin ismetre ac povre paian. peðiv soul ez font istovent por vn nov cliȝs d istroienz istablir… …uphold our most sacred and ancient duty to let Gulfhaven be the centre from which we will send the Word of God to pagan lands. We ask only for the necessary funds for a new teachinghouse…

The Modern Borlish language has undergone spelling standardisation (most recently deprecated some irregular spellings in 1870), and contains many more Latin and Greek loanwords, along with borrowings from languages across the world.

Y stal zajadau dy marcað nogtorn accis par lamp fumer eð y lun fragnt de mar receven cos equal party a domn pescour pevr jarras e fenogl gostant tan eð eç nobr robað n'ornament fluibond ant queldin raut frigsað ne papir cerous. The night market's various stalls lit by smoky lamps and the sea-shattered moon welcomed flocks of fishwives sampling paprika and fennel as well as notables in flowing finery carrying stir-fried suppers in wax papers.

In terms of sound changes and grammatical developments, the major points include:

Intervocalic lenition /p t k b d g/ > /v ð j ∅ ∅ ∅/: catēna > caðen "chain", dēbēre > deïr "must".

The use of ç (and c before e i y) for /ts/, and the use of g in coda to represent /j/. Along with some vowel shifts, this leads to things like cigl /tsajl/ "darling".

Total loss of final consonants in multisyllable words, including -s, which leads to:

Collapse of noun declension, including number; Borlish does not mark number on nouns, and if it wants to it uses demonstratives or simply relies of verb agreement: l'oc scuir pasc, l'ec scuir pascn "this boy eats, these boys eat".

60 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! what would you say are red flags in books about Irish folklore? like things that will tell me this book is not a good source. thank you

I'd say the biggest red flag would be anyone who talks about the Celtic mythologies/pantheons/cultures as a monolith. While many of us talk about the Celts in a generalized way, an educated author should be able to point out the distinction between the Continental and Insular Celts or between say Irish traditions and Welsh traditions. I would side eye any author who talks about specific deities or traditions and doesn't note where specifically they are from and which (if any) other areas may have shared them.

Another red flag I've found is anyone claiming to be part of a long family line of druids. They very well may have come from a family that's passed down occult practices but I highly doubt those practices are 'authentic' pre-Christian druid practices and are much more likely to be cobbled together occult practices from the intellectual period of the 1800s. Possibly interesting in their own nature, but definitely not historical in the way they are trying to portray it as, and thats IF their claims themselves are authentic and not just to sound impressive.

Along the same lines, I'd avoid anything that has to do with Celtic 'Shamanism' or spells magic with a 'k' or if it equates the Irish trope of triple goddesses with the Wiccan concept of the mother, maiden and crone

#irish#paganism#irish mythology#celtic#irish paganism#pagan#irish polytheism#celtic paganism#ask#anon#red flags

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

there are a lot of crazy things about "celtic" neopaganism but asahistorian the craziest one is that like. ok. by "celtic" they usually mean "irish," ie famously one of the first european cultures to embrace catholicism, whose earliest saints are often saints bc they spread catholicism to other insular celts (maybe also scandinavia? idr), and whose people in diaspora are still heavily associated with catholicism. what are you even talking abt, "the christians destroyed the real celtic culture." the 'celts' chose to be christian

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everybody wants to talk about the Gaels when referencing Pan-Celtic cultures (a categorical term to group a large swath of historical ethnic groups with ties to each other genealogically and culturally) still they don't want to mention Celtiberians/Generally Continental Celts.

You guys want to post about Cernunnos and your pseudo-Wiccan pantheons? Don't look to Insular Celts. Portugal, Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, etc. have so many interesting cultures to examine! Not to mention you can look as far east as the Galatian Speakers in Anatolia? (And don't forget Italy...Slovenia...Austria...)

Celts were all over! That's why they are not One Thing at all. I see a lot of posts on here calling deities "Celtic". While this can be true (perhaps they share a lot of common roots in different historical Celtic groups) it's more accurate to assign them to the actual ethnic group(s) they originated from.

i.e: "Arwan is the King of the Otherworld in Welsh Mythology. He can be considered a Welsh and Brythonic Celtic figure."

Or consider: "Epona is an equine diety of Gallo-Roman origin that was worshiped by Celts as far west as Wales. She can be considered a Gallo-Celtic, Brythonic Celtic, Roman, and possibly Iberian Celtic deity."

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

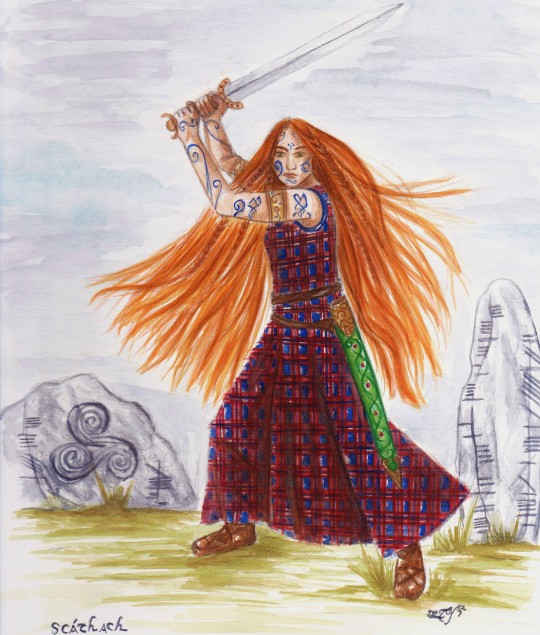

🎨♀Herstory+Celtic throwback♀🎨 - Graphite lineart and watercolour painting of the Scottish warrior-trainer Scáthach from Celtic myth for the 2014 FWW Stock Challenge on DeviantArt. I quite like how this painting turned out 😃 ! . . 🎨Media: Watercolours over graphite drawing . 🍀Other references: DeviantArt stock pic for the main pose, photographs of stones and Celtic swords and designs, self-picture for the skirt movement.

I wanted to draw a Celtic warrior-woman from Irish myth, so here is how I imagine Scáthach of Alba, a formidable warrior-woman with druidic skills who trained warriors in her renowned academy in the island of Skye in Alba (Scotland). She trained a lot of famous heroes, Cúchulainn among them. Her sister, Aoife, was also a great warrior-woman, even greater than herself. . . "If Cúchulainn would go to Scathach, the woman-warrior that lived in the east of Alban, his skill would be more wonderful still, for he could not have perfect knowledge of the feats of a warrior without that." (Lady Gregory's Cúchulainn of Muirthemne).

I wrote Scáthach's name and the names of some other famous warrior-women in Irish myth in the stones using the Celtic tree Ogham alphabet: The left stone includes the names of Nessa, Conchubar's mother, and queen Medb. The stone on the right has "Scáthach banlaoch" (Warrior-woman Scáthach), plus Ogarmach, the invader daughter of the King of Greece, and Macha. . I depicted Scáthach with woad skin-paint, flowing loose hair and a checked sleeveless, ankle-length dress. Although the Celts in Gaul, seemed to favour trousers when fighting, there is evidence that the Insular Celts often preferred dresses and short/long tunics to pants. The warrior-women of this time (c. 1st Century BC) are often described in the mythology as wearing long dresses and cloaks, loose hair, a great number of ornaments, and little to no armour. The same goes for the men (with short/long tunics instead of dresses), as Celts didn't seem to be great fans of wearing armour, preferring to go to battle fully decked in all their (often encumbering) finery and/or with bare chest or directly fully naked xD

🎨ArtStation

🎨Instagram

🎨 DeviantArt

#Celtic culture#Celtic mythology#scáthach#warrior women#My art#banlaoch#Celtic women#Celtic myth#Celts#Irish myth#Scotland#Ireland#cú chulainn#Scáthach of Alba#scathach#watercolours#graphite drawing#watercolour painting#Irish mythology#swordwoman#Celtic warrior#herstory#history#ancient times#ogham#aoife#medb#boudica#nessa#macha

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Scholars have divided Celtic languages into two groups: Insular Celtic and Continental Celtic. The latter group was no longer widely spoken after the Roman imperial period, and, unfortunately, the only surviving examples of it are mentions in the works of Greek and Roman writers and some short epigraphic remains such as pottery graffiti and votive and funerary stelae."

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

the celts didn't paint themselves blue, people made that up centuries later, just an FYI (your cover pic)

yup woad dye is caustic and never would have been used on skin however it looks extremely cool and has found its place in celtic culture regardless so I will sometimes use it in my art

kind of like how ogham was never used for divination historically, but in modern times its become widespread enough that it will be part of ogham's history going forward whether or not we all know Robert Graves was a hack. insular celts never painted themselves woad blue but so many artists in the last 2 centuries have depicted them that way that many Irish & Scottish people today wear blue paint or draw characters that do (St.Diabhal on IG is one of my favorite examples) as a symbol of pride in celtic culture

historical and cultural authenticity is important, but culture evolves every day and room should be made for that ((but as an American that's not really my call so feel free to tell me to stfu))

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

So let me add the European view here - as someone who is actually half-European, half-American.

I have an Americanised German surname. My surname is pretty much only found in America due to a few historical quirks. It's pretty cool, tbh.

Now in Europe, we would say that my US family is 'American, with German heritage'. We say this about ourselves, too -- because given we're all close neighbours & the borders have shifted over time, how many of us do you think are pure anything? My Italian friend has a German surname because his father is German, but he's not German, he's Italian, because he *acts* Italian. It's not exactly an ethnicity, because the lines are so blurred - if you want ethnicities you need to go further back, to the Celts, Gauls, Phoenicians etc.

So when we say 'but you're not German' it's because we recognise that the USA has a very distinct culture that is purely American. This "when American culture is treated as a rip-off of every other culture" view? Yeah, that's not us. That's your own image issues. Anyone who says America doesn't have its own culture is nuts (or American, funnily enough).

American culture is in the way you take cookies round to greet new neighbours, it's in the pride you take in your homes, in the way you engage in small talk, in the way you're so bloody touchy-feely and genuine about it ("I'm so thankful for..." "I really appreciate" "I feel so"). It's in the way you greet immigrants, tourists and strangers -- and as someone who's taken quite a few foreigners to visit in the Deep South, the way you greet foreigners is incredibly welcoming. Culture is in the way you relate to each other and frankly, the way Americans do their best to wear kindness on their sleeves is something to be proud of.

Hell, even if you use that narrow definition of culture as being 'the arts' -- the arts in the states is fluorishing!! Broadway, Hollywood, music, fashion, art -- the US is a cultural powerhouse in the snooty definition, too.

Sure, America has its problems - though sometimes I think that the internet amplifies them, simply because there's so many Americans. Europeans love to laugh at Americans for being a tad dumb, but frankly we're shit at American geography so it's glass houses, really (also have you heard what we say about each other? It's all meant in jest).

So I suppose, when we say "But you're not German!" We're really saying two things: (1) we know German people & they act *nothing* like you, culturally you're American through & through & (2) being American is something to be proud of; why aren't you proud of your culture?

(Having said all that, it sounds like your family is much more culturally German than mine and most Europeans would be (a) surprised & somewhat confused to hear that such communities exist in the US and (b) would probably label that as 'American-German' because it's its own unique thing (modern Europeai German culture has moved on & changed from the culture preserved by the community). Which, fun linguistic fact: did you know the insular American immigrant communities have become the last refuges of some dying European languages?)

"yOu'Re nOt GeRmAn, yOu'rE AmErIcAn"

Okay, bestie, let me explain something to you that is very important to American culture — very, very few of us are ethnically American. When an American says they are "German" or "Irish" or "Italian" they aren't talking about citizenship. They are talking about ethnicity.

The U.S. is primarily a country of immigrants. Everyone says we "don't have a culture" or we have a "bastardized version of *insert culture*" but that's not true!!!! Our culture is made up of American Immigrant Culture!!!! American Italian food isn't "fake Italian food" — it's the innovation of Italian Immigrants who used traditional Italian food along with the ingredients that were more accessible to them in the States. It might not be the food "of Italy" but it is the food of proud sons and daughters of Italy who are also proud Americans. And you can be both.

When American culture is treated as a rip-off of every other culture, we are essentially dishonoring the memory of very brave men and women who chose to leave their homelands under unfortunate circumstances. Men and women who didn't have much money, but did what they could. Used the materials they had. And still managed to make something beautiful out of it. When you leave your home, it doesn't stop being part of your identity — it just looks a little different now. You pass on your old traditions to your children and your children's children, and along the way, new ones are created. Cultures mix and create subcultures. And it's beautiful. It's good. It's primally human.

If I'm not "German" care to explain to me my pasty white skin? Or my last name? Or all the post cards written to and from Germany that we have upstairs in a box? Or the name of my town? Or my grandparents' first language? Or the fact that my American Church, in the year 2024, still sings "Stille Nacht" at every Christmas Eve mass? Sure, I'm not fully German, but the awareness of where I have come from makes up a huge part of my understanding of myself and my place in this world. I was raised in a German Catholic farmtown, and it shows. It shows in the way we worship, and our work ethic, and our reverence for family life.

When an American calls themselves "German" or "Irish" or "Italian" they mean that's where their blood comes from. And it's okay for them to care about that. It's okay for them to care about their roots. It's a major part of American culture.

If you want to "respect" world cultures, you can't just pick and choose which ones are "real" according to you.

#Off my soapbox I get#I love america#If it weren't for the poor social nets I'd live there#The people are amazing#And I've got mixed race kids and all my family is in the deep south so according to the internet it should be awful#Most americans are kind and unashamed of it in a way that's so uniquely american

880 notes

·

View notes

Text

Azerdbaijan, Turkey, Egypt, Insular Celts, French

race vs ethnicity

0 notes

Note

Hello! As an Irish reconstructionist, do you maybe know any specific traditions in celebrating Mean Geimhreadh (Alban Arthan?? Are these the same things??)

Ok, so for me personally this is a REALLY complicated question. I focus my reconstructionism on ~approximately~ Iron Age traditions (I feel this is an 'authentically' 'Celtic Irish' period being an age when there is abundant evidence of the Pre-Christian religion we know of as 'pagan Irish' being practiced and not yet being blended with Christian practices and beliefs).

So as such I don't do anything for Meán Geimhridh. That is not necessarily to say that the peoples of the Iron Age didn't recognize the long hours of darkness on this day, because I am certain they did, but that as far as the evidence that is available to us it was not something that held great religious importance. While the Stone Age religion being practiced seemed to place great importance on the solstices (marking them very clearly in the monolithic monuments and passage tombs they built) and later the dates held importance to the blended cultures of Irish/Scandinavian (yule) and Irish/Christian (Christmas), the period of time I focus on is oddly silent about these solar phenomenon. Apparently, only being noted by the classical writers as Alban Arthan.

However, even here there is a great level of debate. I subscribe to the theory that this particular description of religious activity was actually a case of mistaken identity and was actually speaking of, not the 'Keltoí' peoples, but the Germanic tribes further north (who we KNOW would have recognized this time of year and KNOW had a special religious connection with mistletoe). Furthermore, even IF this historical account WAS speaking of what we think of as the 'celtic' cultures it was obviously addressing an act preformed on the continent, which we know held similar but separate traditions from the insular 'Celts'.

Which brings us back to looking at any evidence for Pre-Christian/Post-Stone Age traditions that mark this time, and we do see some (just not in so much in Ireland). In the UK we see a widespread tradition at this time of year involving the Wren and straw boys, but as far as my research can tell it was likely spread through the UK in its Christian guise and any pagan roots it has are likely Welsh is origin.

Lastly, there is the widespread idea of the Mistletoe King and the Oak King.... this, in my opinion, is a jumbled fabrication of the pagan renaissance of the 1800s, and so while it can be considered 'traditional' at this point, holds no more historical weight then the Wiccan 'wheel of the year.'

At the end of the day, I don't hold any religious significance to the event BUT if I were to try doing something I felt was historically accurate I would keep a fire stoked, keep my family and friends close, eat and drink and share stories and songs to keep us all entertained as we enjoyed each others company (so the basic blueprint for any winter festival in most of the world 😅)

#Meán Geimhridh#Alban Arthan#ask#holidays#winter solstice#irish reconstructionist#irish reconstructionism#yule#Christmas

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yeah so Irish is a Celtic language but everything Irish should not be generalised to “Celt”. Post about Ireland are not the same as posts about Celtic nations. There are 6 insular Celtic groups and a couple other groups that aren’t technically counted cause the language wasn’t maintained but culturally they’re very similar to Celtic groups. It’s like if you’re talking about issues in your country and then someone comes along and applies that to your entire continent, essentially erasing your individual identity and inaccurately portraying struggles. Also the word “Celt” specifically has kinda been mystified on tumblr the same way words like fae and bog have been, it’s very weird and telling when someone comes onto a post about Ireland and starts talking like that

If you’re curious how insular celt groups are broken up so you can understand/identify stuff more accurately:

6 Insular Celtic nations:

Ireland (Irish)

Scotland (Scottish)

Wales (Welsh)

Cornwall (Cornish)

Brittany (Breton)

Isle of Man (Manx)

The first three are countries, the last three aren’t. Cornwall is part of England, Brittany is part of France and the Isle of Man is a self governing crown dependency of England. These are them further broken down into two other groups of Gaelic and Brythonic. Gaelic languages are Irish, Scottish Gaelic (not Scots, that’s a completely different thing) and Manx. Brythonic are Welsh, Cornish and Breton. They’re all their own distinct languages and belong to their own distinct cultures, with a bit of overlap in some places

A Celtic group is officially defined by language so there are some groups that have a lot in common culture wise with Celtic groups (genetics do not matter at all and the whole idea of of “being 1/64 Irish and therefore you are Irish” is based in racism). Galicia is the best known of these with others also around Spain

Hello, american tumblr user. before you is a post about ireland which does not mention anything about irish mythology. if you can reblog the post without making a comment about fairies, magic, the celts, or any associated concepts, you may go. if you cannot, this shillelagh I have in my hand will promptly turn YOU into the next unfortunate victim of stereotypical irish culture. choose wisely, american tumblr user, you will not be afforded a second chance

#it’s also particularly annoying when you’re trying to talk about the oppression you’ve faced#and people who know nothing about it involve themselves and get shit wrong#or make a joke out of it#cause yeah all Celtic nations have and still do face this shit#but each groups experience is unique

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

@ all of my pagan friends, can you give me some reputable sources on the pre Christian religion of the Insular Celts?

My focus has largely been in the Continental Celts but I want to make sure I have a well informed and accurate knowledge base for the Insular Celtic religious landscape as well.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I NEED to write some sort of essay dissecting how legends of the Otherworld traveled from Continental Celtic cultures to Insular Celtic cultures/Brythonic cultures. The similarities between the Gaullish Albios, Irish and Scottish Tir na Og/Mag Mell, Welsh Annwn, Breton Anaon, and Irish/Manx Emain Ablach. There is so much content and cross-contamination!! Not to mention parallels with Avalon!? The travel of the Celts from Iberia to the British Isles left behind few similarities (except for Brittany) so it is interesting to see that legends of the Otherworld stayed quite similar. Of course, Ireland and Scotland hold a higher emphasis on the fairy realm aspect of the Otherworld, but all mythologies have a strong ideal of "the West". That is still reflected in media today! (See: Valinor in JRR Toilken's work)

2 notes

·

View notes