#Jacques Rancière

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Currently reading: Jacques Rancière, The Intervals of Cinema

#study#studyblr#studygram#studyspo#book#books#bookblr#booklr#bookstagram#books & libraries#reading#books and reading#booklover#bookworm#inspiration#jacques rancière#cinema#philosophy#film#films#film studies

261 notes

·

View notes

Text

La distraite, Jacques Rancière

#La distraite#Jacques Rancière#Jean Siméon Chardin#La ratisseuse de navets#Dziga Vertov#L'homme à la caméra

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In Borges, as in Plato, there is a good way and a bad way for words to circulate. The bad way is the way of literature, which only circulates in order to block exchange: an interminable book, words that try to say everything. The good way is no longer, as in Plato, the way of the master’s words. It is the way of the shared dream. The sterile imagination is the imagination that produces a dream no one else can dream. Flaubert likes to enter into Emma’s ‘young girl’s dreams,’ but he refuses to be dreamed by her in turn, just as the Proustian narrator refuses to be dreamed by Charlus or Swann. The good way is the way of a dream that can be dreamed in turn, that already has been dreamed an incalculable number of times because it is itself a bit of the dream that is the world.” – Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Literature

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rhetoric is perverted poetry.

Jacques Rancière, The Ignorant Schoolmaster

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not me realising my last post could be read as making this mistake and then seeing this post right afterwards. 🫣 Angst and the ✨drama✨ that comes with it crosses all class boundaries, including the effeminate foppish variety. The need to agonise about our meaning and significance is universal, just as alienation is universal. The difference in how angst presents itself though depends on the type of alienation. People with no need to work or maintain close relationships are more likely to be alienated from others and so look for some significance to their existence in isolation or seek to overcome their isolation, whereas those forced to work for others are more likely to valorise work itself or seek to gain independence.

Both of these can involve looking to become more like people of other classes to overcome the disadvantages of your own position, and everyone is more (innately?) predisposed to certain traits which may not fit with the social position they’re assigned (this is obviously true of other things like gender, too), so anyone from anywhere could potentially act contrary to our simplistic stereotypes. One of the evils of capitalism and other structures like it is that it represses people who want to resist those stereotypes.

Anyway here is your reminder that poor effeminate men existed in the 18th century and any reading of class that acts as tho every poor man was a hyper masculine rugged labourer and every rich man was a effeminate fop is an inherently flawed reading of class 🙃

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

Jacques Rancière - Sanatın Yolculukları (2024)

Jacques Rancière’in sanat üzerine yazılarını bir araya getiren bu koleksiyonun merkezinde modern sanatın kurucu paradoksu yer alıyor. Düşünür burada, Hegel ve Kant’a da uzanarak modern, çağdaş sanatın doğuşuna ve evrimine derinlemesine bakıyor. Sanat özerk bir deneyim alanı olarak kurulup müzelere veya konser salonlarına yerleştiği zaman, kendi dışına çıkma, yani sanattan başka bir şey olma…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Car la question politique est d'abord celle de la capacité des corps quelconques à s'emparer de leur destin.

For the political question is first and foremost the ability of any body to take control of their destiny.

Jacques Rancière, Les paradoxes de l'art esthétique, in Le spectateur émancipé, 2008.

1 note

·

View note

Text

<< Le prétendu "effet de réel" est bien plutôt un effet d'égalité. Mais cette égalité n'est pas l'équivalence de tous les individus, les objets et les sensations sous la plume de l'écrivain. Il n'est pas vrai que toutes les sensations soient équivalentes, mais il est vrai que n'importe laquelle d'entre elles peut provoquer pour n'importe quelle femme des classes inférieures la vertigineuse accélération qui la rend susceptible d'éprouver les abîmes de la passion. >> --- Jacques Rancière, Le Fil perdu (2014), La Fabrique, p. 26

1 note

·

View note

Text

“So the first point for me is that what was true in my study of workers education in the 19th century is this simple notion: everybody thinks. And so you do not have two categories of individuals: individuals really entrapped in the universe of pain, suffering, and emotion, and individuals situated on the side of knowledge. And what I tried to show, for instance in my study of Louis-Gabriel Gauny’s reconstruction of the working day, out of his own experience, is that it was not the expression of a pain and suffering. It is already a kind of intellectual construction, a way of understanding what happens, what happens in the working day, what it consists of, etc. And it's always a form of knowledge of a system of domination. I would say that Gauny’s intellectual reconstruction of the working day is a form of knowledge, while Marx's analysis of the working day as a kind of matrix of capitalism, capitalistic dynamics, is another form of knowledge.

We have not knowledge on this side and ignorance on the other side. We have two forms of knowledge about education and domination, and two forms of knowledge about how a system of domination takes its grip on time. For me, this is the first point. The second point is that you do not have knowledge on this side and feeling on the other side, that in fact, every form of knowledge is also tainted by a certain regime of affect.”

Jacques Rancière

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jacques Rancière’s essay Figures of History makes many arguments that seem urgent for our times. He says, for example, that the artist’s duty is to show ‘what can’t be seen, what lies beneath the visible’. This pleases me, because the late Russian poet Grigory Dashevsky always saw this as the role of poetry, to bring the invisible to the point of visibility. Rancière’s most important point is this: in his writing about history, he contrasts ‘document’ and ‘monument’. A ‘document,’ for him, is any record of an event that aims to be exhaustive, to tell history, to make ‘a memory official’. A ‘monument’ is the opposite of ‘document’, in ‘the primary sense of the term’: “that which preserves memory through its very being, that which speaks directly, through the fact that it was not intended to speak – the layout of a territory that testifies to the past activity of human beings better than any chronicle of their endeavours; a household object, a piece of fabric, a piece of pottery, a stele, a pattern painted on a chest or a contract between two people we know nothing about…”

—Maria Stepanova, In Memory of Memory, tr. Sasha Dugdale

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robert Beavers' Listening to the Space in my Room proposes the idea that space is nothing but a stratified zone of receptivity, of permeability into which the tremblings of the heart reach and find just as many resonances as they send out for. We inhabit space; according to the rhythmicality, the tonality of our lives, space becomes our sojourn. Yet cinema invokes a curious doubling of what we call space, making it uninhabitable, always from a distance, before making it ours again, though this time as space lived from afar, as if I would become the dreamer of another's sleep. As Jacques Rancière suggests, the image is always a third still, impossible to reduce to the intention of the imagemaker nor to the interpretation of the spectator — it is always, invariably, a third, meaning that I could never hope to occupy it, to make it my own. I cannot but watch the image from a distance. Cinematic space is categorically uninhabitable; it opens itself up by the same breathturn according to which it encloses itself again. And yet it is infinitely open, too. But only if we ourselves are prepared to become equally open and meet the image somewhere halfway, always halfway. Serge Daney wrote that the cinema taught him where his gaze ends and the gaze of another begins. Could it be however that what separates my gaze and the gaze of another is exactly this meeting of two gazes, each belonging to the ontological density of a visage, infinitely distanced from one another? If so, cinema is always a matter of ethics — and I, I can only hope to inhabit cinematic space to the extent that I, too, become the sojourn for its image, and we together come to sound in the same yellow note of light. When Robert Beavers set out to put to image the surrounding space of his room, he could perhaps not have envisioned that he would capture a glimpse of cinematic space altogether and the space of our hearts. And when the final image turned to black, I had seen and heard it all (sound having become vision, the image become song) — every single gesture, turn of light, or change of season, all of them, all of us cosmic bodies continuously, unendingly crashing into one another, and I became aware of every trembling as I trembled concurrently, and still I sound, always still I sound for in the image I become space and I become time, and we together, if only for a little while, if only for the impossible duration of an instant, come to share in the same breathturn where nothing endures except the utter fact of our having met in spite of all.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Such people use obscure words to disguise the triteness of what they have to say and retort that there has been a misunderstanding as soon as you think you have understood what they are saying – that is, precisely, something trite.” – Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Literature

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hell Without Poetry

I started reading Proletarian Nights by Jacques Rancière, about contradictory aspirations held by artisanal workers in early 19th century France. One of the most interesting points so far are the fact that some workers had a culture of emulating bourgeoise fashion and not saving money, both to differentiate themselves from the domestic servants they felt they were superior to, and to signal that they deserved the same privileges as the bourgeoisie but rejected capitalist ethics of accumulating in order to exploit others.

I’ve just gotten into the famous Gauny section, where Rancière goes off an a tangent about this philosophical joiner (someone who makes wooden building components). The first of his books I read was The Ignorant Schoolmaster, which similarly takes up a single historical figure in order to develop their ideas into a universal, ahistorical frame by blending his voice with theirs. I find the idea really interesting, and it makes me wonder if I could do the same for the people I interviewed for my dissertation. I like how it deconstructs the boundary between historical actor and theorist, emphasising that all people are both, but it only works of course if the people you’re quoting are doing a substantial amount of philosophising. I also don’t want to lose marks for a stylistic gambit.

One of Gauny’s ideas is that work is work, always demeaning no matter what its content is. Rancière points out that this is similar to the philosophy of a preacher at the time, who valorised work for its essential self-sacrifice (Max Weber pricks up his ears), because it allows our body to fulfil its debt created by the wage given by the employer. This is obviously ideologically beneficial to the status quo because valuing just particular aspects of work rather than work it and of itself would suggest that those parts should be expanded i.e. that work can be better or worse and might be improved.

However, Gauny twists the message by separating the effect it has on the body from the effect on the soul. He admits that there is a pleasure to physical self-sacrifice - even though hard work of the sort he was doing can have awful long-term consequences, there’s pleasure in the oblivion you can reach in the arduous routine of it - but he emphasises that it kills the soul by not giving you breathing time to sit and contemplate, discuss ideas, and make art. There’s a beautiful section where Gauny says

“Ah, Dante, you old devil, you never traveled to the real hell, the hell without poetry!”

This speaks to the ideas at the heart of Rancière’s entire project: that everyone aspires to critically engage in the arts, and that the extent to which do is not overdetermined by class position. His project in this book in particular is to demonstrate that there is no pure working class - there is frequent infighting within and between professions and genders, and their morality is often inspired by the bourgeoisie.

In fact, one of the most interesting parts is that many of the workers start seriously questioning the status quo only after they’re visited by bourgeois do-gooders, but rather than take on the ideas of these champagne socialists uncritically, they use them to inspire new ideas. Rather than expecting a new world to come from one place, we should recognise that novelty is always a result of the melding of difference. It actually makes me think of the fact that so many of the progressive ideas developed in Europe, from Rousseau to Marx, were inspired by Native American philosophies (David Graeber & David Wengrow’s book, The Dawn of Everything, has a great section on the possible influence on Rousseau).

The aspirations of people like Gauny to write poetry, to come up with new ideas based on a variety of sources, was largely unrecognised or dismissed when Rancière wrote this in the ‘80s. He was frustrated that not only did capitalists view working people as beneath of that sort of thought, but Marxists saw it as counter-revolutionary and therefore unbecoming. Rancière was disillusioned with Althusser, who’s structuralist Marxism he saw as not leaving any space for people to resist their circumstances, instead being overdetermined by class. I don’t know Rancière’s stance on free will, but as a rather dogmatic determinist even I find that frustrating, as if we aren’t influenced by so much else which can give rise to disruptive convergences. Basically, people are more complicated than that! Any supposedly emancipatory philosophy with a single vision of what the working-class should be is doomed to failure, as Rancière well knew from witnessing the dismissal of the student protests of ‘68 be dismissed as “not real revolution”.

Rancière saw in Gauny a way out of this structuralist trap, where by taking on the high-minded ideas of the more romantic bourgeoisie and reinterpreting them with a personal need to act against the system, new ideas could be created and used to disrupt the distribution of the sensible, or the matrix of acceptable ideas - most important of which was the idea of who is capable of having such ideas. This concept is actually where my name comes from!

I wonder if we’re losing this time to contemplate even more today, with the spectacle invading so much of our lives - social media being the quintessential example. This is not such a danger if we’re using it to chat to people, but if we’re just scrolling… there’s not much thinking going on there. 😅 Guy Debord, in the ‘50s, was already talking about capital colonising our everyday life, and this stealing of attention, our time to think and talk and create and have ideas, seems to be the worst consequence of it.

#jacques rancière#marxism#karl marx#david graeber#capitalism#alienation#philosophy#social theory#sociology#history#france#french history#poetry#dante#work#equality#social media#guy debord#spectacle#society of the spectacle

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jacques Rancière Interview with Daniel Tutt

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#La Petite école : lucioles - loutchina

Mais Tchekhov ne fait pas de la littérature à coups de marteau. Et il lui déplaît même d'employer, pour ce qu'il veut montrer, une lumière trop brutale. Il préfère user, lui aussi, de cette loutchina dont la flamme fragile semble être la réponse anticipée à la "lampe de Lénine" qui, dans les années 1920, symbolisera la lumière du progrès apportée par l"industrie sociale dans les demeures paysannes. La loutchina de l'écrivain n'apporte pas la conscience aux ignorants, elle se contente de rappeler qu'il y a une promesse d'une vie claire, une vie on l'on saura pourquoi on vit. Elle fait trembler en une même vibration les larmes de la tristesse et celles de la consolation.

Car le problème n'est pas de faire comprendre les causes du malheur, il est plutôt d'en faire sentir autrement la tristesse. (...)

L'écrivain à la loutchina ne prétend pas changer la pensée de ses lecteurs pour les conduire à l'action qui engendrera une société plus juste. Il veut changer la modalité de leur chagrin et pour cela exercer une justice au présent. "Il faut être juste, tout le reste suivra", dit-il à son éditeur. (...)

Il faut trouver le ton juste pour rendre sensible à tous le chagrin d'un seul et à chacun le malheur de tous (...)

Pour briser le cercle, pour former des hommes capables de transformer en réalité l'appel de la vie nouvelle, il faut d'abord changer les manières de sentir. C'est une révolution des affects que s'emploie l'écrivain.

Jacques Rancière, Au loin la liberté, Essai sur Tchekov, 2024, pp. 67-69

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

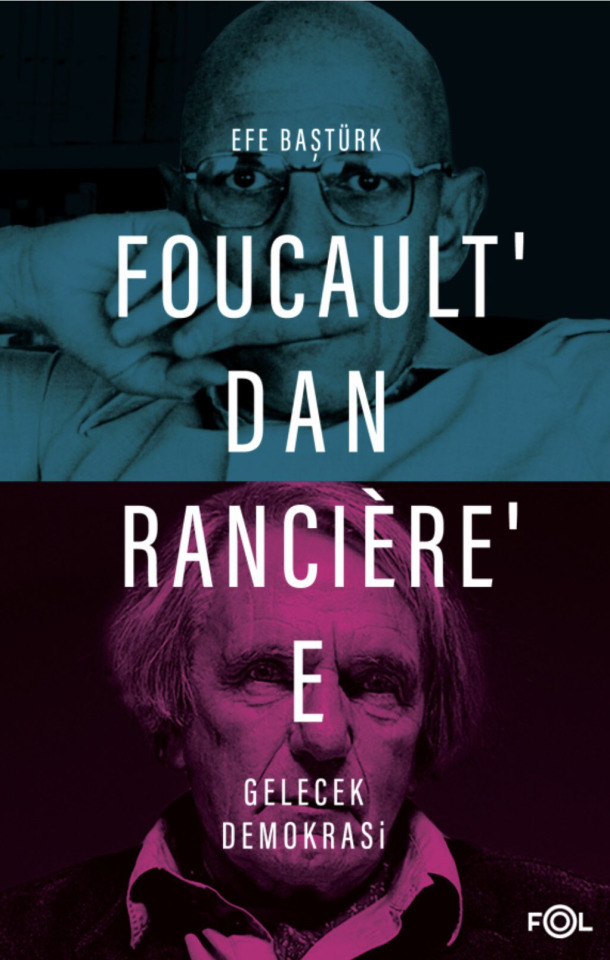

Efe Baştürk – Foucault’dan Rancière’e Gelecek Demokrasi (2023)

Bu kitap çağdaş felsefenin mimarları Foucault, Derrida, Agamben, Rancière ve Nancy’nin politik düşüncesinin izini sürüyor. Foucault’da delilik ve kapatılmadan Rancière’in ‘Cahil Hoca’sına, Derrida’da tekillik ve konukseverlikten Agamben’de dil ve sessizliğe uzanan bir yol izliyor. Bu kitaptaki ‘çağdaş’ düşünürlerin ortak problemi, polisin (kent devletinin) başlangıçtan beri idealize edilmiş…

View On WordPress

#2023#Efe Baştürk#Fol Kitap#Foucault’dan Rancière’e Gelecek Demokrasi#Giorgio Agamben#Jacques Derrida#Jacques Rancière#Jean-Luc Nancy#Michel Foucault

0 notes