#Jean Améry

Text

«Por tanto me atrevo a afirmar que al abandonar Auschwitz no éramos ni más sabios ni más profundos, pero sí más avisados. “La profundidad de pensamiento jamás ha iluminado el mundo; pero la claridad de entendimiento lo penetra más profundamente”, dijo cierta vez Arthur Schnitzler. Para asimilar esta sagacidad el lugar más adecuado era el campo de concentración, sobre todo Auschwitz. Permítaseme citar, una vez más, a un austríaco, Karl Kraus, que en los primeros años del Tercer Reich pronunció las siguientes palabras: "El verbo expiró, cuando despertó aquel mundo". Ciertamente, Kraus hablaba como defensor de este "Verbo" metafísico, mientras nosotros, supervivientes del campo de concentración, retomamos esta sentencia y la reproducimos con escepticismo frente a las posibilidades verbales. La palabra cesa en cualquier lugar donde una realidad se impone como forma totalitaria. Para nosotros ha muerto hace mucho tiempo. Y ni siquiera nos ha quedado la sensación de que fuera menester lamentarnos por su pérdida.»

Jean Améry: Más allá de la culpa y la expiación. Pre-textos, pág. 80. Valencia, 2001.

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

@dias-de-la-ira-1

#jean améry#hans mayer#más allá de la culpa y de la expiación#tentativas de superación de una víctima de la violencia#auschwitz#arthur schnitzler#scnitzler#karl kraus#kraus#entendimiento#tercer reich#violencia#víctima#víctimas#victimario#palabra#palabras#verbo#campo de concentración#campo de exterminio#escepticismo#realidad#teo gómez otero

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

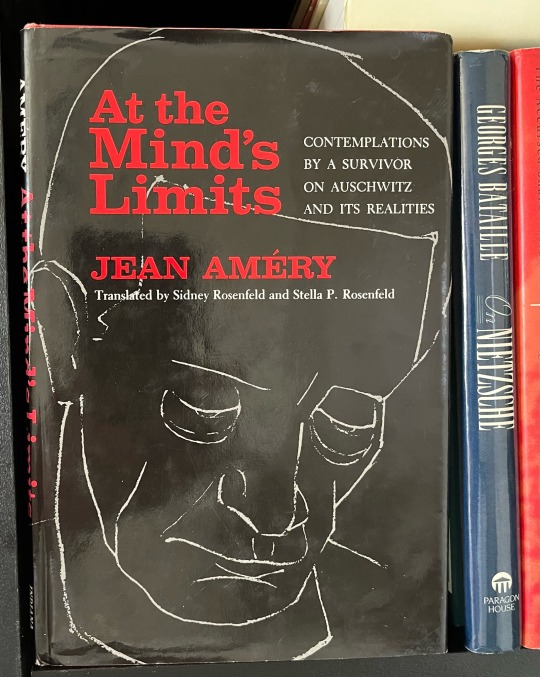

“The moment has come to make good a promise I gave. I must substantiate why, according to my firm conviction, torture was the essence of National Socialism - more accurately stated, why it was precisely in torture that the Third Reich materialized in all the density of its being. That torture was, and is, practiced elsewhere has already been dealt with. Certainly. In Vietnam since 1964. Algeria 1957. Russia probably between 1919 and 1953. In Hungary in 1919 the Whites and the Reds tortured. There was torture in Spanish prisons by the Falangists as well as the Republicans. Torturers were at work in the semifascist Eastern European states of the period between the two World Wars, in Poland, Romania, Yugoslavia. Torture was no invention of National Socialism. But it was its apotheosis. The Hitler vassal did not yet achieve his full identity if he was merely as quick as a weasel, tough as leather, hard as Krupp steel. No Golden Party Badge made of him a fully valid representative of the Führer and his ideology, nor did any Blood Order or Iron Cross. He had to torture, destroy, in order to be great in bearing the suffering of others. He had to be capable of handling torture instruments, so that Himmler would assure him his Certificate of Maturity in History; later generations would admire him for having obliterated his feelings of mercy.

Again I hear indignant objection being raised, hear it said that not Hitler embodied torture, but rather something unclear, "totalitarianism." I hear especially the example of Communism being shouted at me. And didn't I myself just say that in the Soviet Union torture was practiced for thirty-four years? And did not already Arthur Koestler . . . ? Oh yes, I know, I know. It is impossible to discuss here in detail the political "Operation Bewilderment" of the postwar period, which defined Communism and National Socialism for us as two not even very different manifestations of one and the same thing. Until it came out of our ears, Hitler and Stalin, Auschwitz, Siberia, the Warsaw Ghetto Wall and the Berlin Ulbricht-Wall were named together, like Goethe and Schiller, Klopstock and Wieland. As a hint, allow me to repeat here in my own name and at the risk of being denounced what Thomas Mann once said in a much attacked interview: namely, that no matter how terrible Communism may at times appear, it still symbolizes an idea of man, whereas Hitler-Fascism was not an idea at all, but depravity. Finally, it is undeniable that Communism could de-Stalinize itself and that today in the Soviet sphere of influence, if we can place trust in concurring reports, torture is no longer practiced. In Hungary a Party First Secretary can preside who was himself once the victim of Stalinist torture. But who is really able to imagine a de-Hitlerized National Socialism and, as a leading politician of a newly ordered Europe, a Röhm follower who in those days had been dragged through torture? No one can imagine it. It would have been impossible. For National Socialism - which, to be sure, could not claim a single idea, but did possess a whole arsenal of confused, crackbrained notions - was the only political system of this century that up to this point had not only practiced the rule of the antiman, as had other Red and White terror regimes also, but had expressly established it as a principle. It hated the word "humanity" like the pious man hates sin, and that is why it spoke of "sentimental humanitarianism." It exterminated and enslaved. This is evidenced not only by the corpora delicti, but also by a sufficient number of theoretical confrmations. The Nazis tortured, as did others, because by means of torture they wanted to obtain information important for national policy. But in addition they tortured with the good conscience of depravity. They martyred their prisoners for definite purposes, which in each instance were exactly specified. Above all, however, they tortured because they were torturers. They placed torture in their service. But even more fervently they were its servants.” - Jean Améry, ‘At the Mind's Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and Its Realities’ (1966) [pages 30, 31]

#amery#améry#jean amery#jean améry#at the mind’s limits#third reich#wwii#holocaust#torture#fascism#hitler#mengele

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Una cuchara tallada en madera era realidad o «naturaleza», como se decía antiguamente. Se oponía al temperamento. Algo por el estilo se vuelve imposible con una cuchara de plástico, y esto no lo digo por tozudez reaccionaria, sino por experiencia plástica. La lisura y la uniformidad de un objeto tal de uso corriente sugiere multiplicación; el temperamento se eriza, cuando pretende acercarse al objeto. Deniega. Renuncia. Se volatiliza sin dejar rastro. Y la monotonía de lo múltiple se impone y dice sarcásticamente que ella desenmascara el mundo, cuando, a todas luces, no es sino conformidad indolente.

Jean Améry, «Éxito» en Lefeu o la demolición. Traducción de Enrique Ocaña.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“ …L’histoire, ce mélange indécent de banalité e d’apocalypse…”

(Jean Améry)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Les Émotifs anonymes

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Une famille à louer [Family for rent] (Jean-Pierre Améris, 2015)

#comedy film#long métrage#Virginie Efira#France#Europe#Jean-Pierre Améris#François Morel#Philippe Rebbot#amour#Une famille à louer#Family for rent#Édith Scob#relationships#Benoît Poelvoorde#Belgium#famille#family#neurosis#life#cinema français#french movies#Pauline Serieys#motherhood#European cinema#single mother#shop lifting#entertainment#Familie zu vermieten#romance#Lucie Mandini

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

la joie de vivre (jean pierre améris, 2012)

#la joie de vivre#swann arlaud#watchlist#new motivation to start reading les rougon macquart books just dropped#this was in my drafts for so long it's time to share Him with the world

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

SARAH MOON & HERTA MÜLLER

Hay una película rumana de Lucian Pintilie llamada La reconstrucción. Un equipo de la policía y un equipo de cineastas obligan a un joven a reconstruir una pelea con su amigo con el fin de hacer una película. Han recibido el encargo de rodar una película juvenil propagandística que disuada de las peleas. Durante el rodaje, el equipo de cine y la policía luchan cada uno por una forma distinta de autenticidad: los cineastas, por la autenticidad del arte; los policías, por la autenticidad de la represión. El joven que se ha peleado está al margen de todo. Ninguna de las dos formas de autenticidad tiene nada que ver con la vida actual del chico. Ya no es el que era en el momento de pelearse. Lo que le mandan hacer ahora, a modo de repetición, es inane. Son necesarias constantes amenazas de la policía y toda suerte de técnicas de interpretación del lado de los cineastas para motivarle. Viéndose ahora frente a su amigo, carece de la rabia de aquel momento. Sin embargo, en su interior nace otro tipo de rabia azotada por la imposición. No tiene nada que ver con su amigo pero la canaliza en él. Y le golpea, le golpea y no tiene medida. Lo que hace resulta auténtico porque, en el interior de su mente, está dando golpes a los que le torturan. Los policías y el equipo de rodaje están contentos. Pero cuando apagan la cámara, el amigo está tumbado en el sueño y no se mueve. Está muerto. Horrorizado, el joven protagonista se aleja corriendo y pasa junto a un grupo de personas. Estas, al ver al otro muerto en el suelo. gritan “¡Asesino!” y comienzan a perseguirlo. La policía y los cineastas siguen allí tan tranquilos, ni se molestan en explicar a la masa lo que ha sucedido. El odio que se vuelve contra el chico, el sujeto del odio inicial, protege a los causantes del hecho. Al terminar la película se sabe que callarán para siempre. Jamás asumirán su responsabilidad. La película fue prohibida en Rumanía inmediatamente después de su estreno.

Me acuerdo de esa película a menudo. Lo que no sucede en el momento de los hechos sucede durante su reconstrucción.

La reconstrucción —aunque no tenga lugar por circunstancias externas (como en la película citada) sino por la propia necesidad de someterse al recuerdo— puede tener consecuencias similares. Supera la intensidad de los hechos de entonces y no puede agarrarse a sí misma, sino solo al daño que ha quedado. Para la persona que debe recordar es una recaída en su Yo de entonces y de ahora. Pero mientras que los hechos del pasado se encontraban en el plano de la defensiva, el daño hace que la reconstrucción se vuelva ofensiva. Agresiva incluso contra quien se ve obligado a recordar. El recuerdo llega a destrozar a personas que, habiendo visto la muerte de otros, fueron capaces de escapar de ella. La postura moral ante este “deber de recordar”, la angustia de buscar una escala para valorar los hechos se extiende a todo el cuerpo. No queda nada que pudiera medirse por esa escala. Paul Celan, Primo Levi, Jean Améry, Inge Müller… fueron considerados durante cierto tiempo como “personas salvadas”. Pero también eran personas destrozadas. Sus vidas terminaron en el suicidio. Con una postura moral tan contundente y tan sumamente personal ante los hechos como fue la suya, llegar a algún tipo de compromiso era impensable. Como si hiciesen un conjuro, dieron abrigo a los “perdidos” en la palabra escrita, y con este hilo atrajeron hacía sí a los muertos. Pero esto solo funcionaba porque del hilo se tiraba desde los dos extremos. Del otro lado, también los muertos tiraban. Al final ellos fueron más fuertes.

HertaMüller, En la trampa. Tres ensayos. Trad. Isabel García Adánez. Siruela: 2015.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whoever has succumbed to torture can no longer feel at home in the world. The shame of destruction cannot be erased. Trust in the world, which already collapsed in part at the first blow, but in the end, under torture, fully, will not be regained. That one's fellow man was experienced as the antiman remains in the tortured person as accumulated horror. It blocks the view into a world in which the principle of hope rules. One who was martyred is a defenseless prisoner of fear. It is fear that henceforth reigns over him.

Jean Améry, Indiana University Press. At the Mind's Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and Its Realities

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Über die Wiederkehr des Antiimperalismus im Postkolonialismus

Agitprop mit akademischem Antlitz

Wie der Antiimperialismus im Gewand des Postkolonialismus wiederkehrt.

Von

Marcel Matthies

Auf das Erschrecken über die Brutalität des antisemitischen Massenmords folgt das Erschrecken über den weltweiten Umgang damit. Der überwiegende Anteil der antiisraelischen Mobs auf den Straßen europäischer und nordamerikanischer Großstädte scheint sich längst von der politischen Wirklichkeit emanzipiert zu haben und für Erfahrungen nicht mehr empfänglich zu sein. Erkennbar ist das daran, dass der kollektive Mordrausch der Hamas bei den Unterstützern der palästinensischen Sache paradoxerweise keine Distanzierung von den Jihadisten bewirkt hat; vielmehr scheint es so, dass die Zusammenrottungen auf den Straßen den Kampf der Hamas gegen Israel legitimieren, wenn nicht gar feiern.

Der notorische Hinweis darauf, dass nicht jede Kritik an Israel antisemitisch sei, vernebelt dabei nur die Tatsache, dass sich der Antisemitismus global betrachtet heute vor allem in Form von Israelkritik zeigt. Kennzeichnend für eine übersteigerte Feindseligkeit gegenüber Israel sind die Entkoppelung der Bodenoffensive der IDF vom kriegsauslösenden Ereignis am 7. Oktober, die Androhung genozidaler Gewalt (»Tod, Tod Israel«) und die reflexionsfreie Projektion alles Bösen auf den Judenstaat (»Völkermörder«, »Kindermörder«). In der Phantasmagorie, Israel verübe einen Genozid an den Palästinensern, verschafft sich eine gegen Juden gerichtete genozidale Gewaltphantasie Geltung. Israel als Brückenkopf eines vom »Westen« gesteuerten kolonial-rassistischen Imperialismus darzustellen, ist das Anliegen derjenigen, die nicht darüber reden wollen, dass die Hamas die Schuld an der Eskalation trägt. Denn den meisten Feinden des Judenstaats ist nicht an einer Kritik der israelischen Politik gelegen, sondern daran, Israel als jenen Staat, der jüdische Souveränität garantiert, für illegitim zu erklären. Ziel ist die Auslöschung des Staates Israel.

Von alarmierender Aktualität ist daher Jean Amérys Bestandsaufnahme aus dem Jahr 1976, weil er darin die Variabilität der Erscheinungsformen ewig gleicher Ressentiments kenntlich macht: »Der Antisemit will (…) im Juden das radikal Böse sehen: und da ist ihm ein im fürstlichen Dienste stehender Zinswucherer als Haßobjekt ebenso recht wie ein israelischer General. Dem Antisemiten ist der Jude ein Wegwurf, wie immer er es anstelle: Ist er, gezwungenermaßen, Handelsmann, wird er zum Blutsauger. Ist er Intellektueller, dann steht er als diabolischer Zersetzer der bestehenden Weltordnung da. Als Bauer ist er Kolonialist, als Soldat grausamer Oppressor. Zeigt er sich zur Assimilation (…) bereit, ist er dem Antisemiten ein ehrvergessener Eindringling; verlangt es ihn nach jener (…) ›nationalen Identität‹, nennt man ihn einen Rassisten.«

Die Islamisten machen keinen Hehl daraus, dass die Auslöschung des jüdischen Staates, an dessen Stelle das Kalifat entstehen soll, nur der Anfang ist und andere westliche Demokratien folgen müssten. Als gar nicht mal heimlicher Verbündeter des islamistischen Mobs muss Putin gelten.

Dabei machen die Islamisten keinen Hehl daraus, dass die Auslöschung des jüdischen Staates, an dessen Stelle das Kalifat entstehen soll, nur der Anfang ist und andere westliche Demokratien folgen müssten. Als gar nicht mal heimlicher Verbündeter des islamistischen Mobs muss Putin gelten. Nicht zuletzt zeichnet sich vor dem Hintergrund des russischen Angriffskriegs auf die Ukraine das Drängen einer antiwestlichen Strömung auf eine weltpolitische Neuordnung ab. Was die Semantik postkolonialer Theorie und russländischer Doktrin eint, ist ihre obsessive Feindschaft gegen »den Westen« und alles, was mit diesem assoziiert wird. Es ist durchaus folgerichtig, dass der Putinismus über eine erstaunlich ähnliche Weltanschauung verfügt wie diejenigen, die im Namen des sogenannten Globalen Südens gegen alles »Westliche« kämpfen. Was beide Sichtweisen verbindet, ist eine nahezu identische Deutung des Zweiten Weltkriegs und deren Übertragung auf das historisch-politische Verständnis der Gegenwart.

Dieses Geschichtsbild ist dadurch gekennzeichnet, dass die Sicht auf den Nationalsozialismus sowohl im Putinismus als auch im Postkolonialismus bis heute primär durch ein kolonial-imperiales Paradigma bestimmt wird, das dem »Westen« genuin entsprungen sei und – als habe es nie eine Dekolonisierung gegeben – bis in die Gegenwart fortwirke. Dies geht mit der Überzeugung einher, der Westen sei sui generis kolonialistisch, rassistisch und imperialistisch. Hinzu kommt, dass der Putinismus und der Postkolonialismus insofern programmatische Überschneidungen aufweisen, als sie sich beide in einem Zustand quälender Ambiguität im Verhältnis zum Westen befinden: Die Ambiguität leitet sich aus einem starken Kränkungsgefühl her, das dadurch ausgelöst wird, dem Westen (insbesondere den USA) ökonomisch unterlegen zu sein, gleichzeitig aber moralische Überlegenheit über den Westen zu beanspruchen.

Mit als Theorie bemänteltem Agitprop wird indessen das verstaubte Weltbild des Antiimperialismus durch Ideologeme des Postkolonialismus restauriert. Der Zwergstaat Israel ist dabei zu der vielleicht wirkmächtigsten Projektionsfläche für Anhänger dieses bipolaren Weltbilds geworden, ermöglicht es doch, Gewalt zu legitimieren und Israel einen Kolonialcharakter anzudichten. Dieser mache den Zionismus wiederum wesensgleich mit dem Nationalsozialismus. So wird Israel zum »Kristallisationspunkt eines neuen Antisemitismus, der sich gleichwohl teils als antirassistisch und antikolonialistisch versteht«, so der österreichische Schriftsteller Doron Rabinovici.

Was die Semantik postkolonialer Theorie und russländischer Doktrin eint, ist ihre obsessive Feindschaft gegen »den Westen« und alles, was mit diesem assoziiert wird.

Gewiss gab es seit den achtziger Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts eine Kolonisierung auf einem bestimmten Gebiet im Osmanischen Reich, das damals dünn besiedelt war und überwiegend von Zionisten Palästina genannt wurde. Jedoch hat deren Kolonisierung nichts mit dem heutigen Verständnis von Kolonialismus gemeinsam: Die ersten Zionisten besetzten nicht etwa das Land, sondern erwarben es käuflich auf legale Weise. Sie knechteten nicht die einheimische Bevölkerung dieser Region. Sie wanderten nicht ein, weil sie von einem Mutterland dazu aufgefordert wurden, sondern beabsichtigten lange vor der Shoah die Neugründung einer nationalen Schutz- und Heimstätte. Sie handelten nicht aus wirtschaftlichen Interessen, sondern reagierten auf die Pogrome im Zarenreich und das Scheitern der Emanzipationsversprechen in Mittel- und Westeuropa. Das Hauptmerkmal des Kolonialismus, das der Historikerin Franziska Krah zufolge im Ziel der Ausbeutung an Ort und Stelle besteht, fehlt dem Zionismus.

Solcher Unterscheidungen unterschlagen die Anhänger des Postkolonialismus. Edward Saids an Manifeste erinnernde Schriften deuten den Zionismus zum Kolonialismus um: »Was auch immer der Zionismus für die Juden getan haben mag, er betrachtete Palästina im Wesentlichen wie die europäischen Imperialisten, als ein leeres Gebiet, das paradoxerweise mit unedlen oder vielleicht sogar entbehrlichen Einheimischen ›gefüllt‹ war; (…) darüber hinaus akzeptierte der Zionismus bei der Formulierung des Konzepts einer jüdischen Nation, die ihr eigenes Territorium ›zurückerobert‹, nicht nur die allgemeinen Rassenkonzepte der europäischen Kultur, sondern stützte sich auch auf die Tatsache, dass Palästina tatsächlich nicht von einem fortgeschrittenen, sondern von einem rückständigen Volk bevölkert war, über das es herrschen sollte«, schreibt Said in »The Question of Palestine« 1979.

Eine ähnliche Schablone bemüht Putin, wenn er, wie am 13. Oktober geschehen, die israelische Militäraktion in Gaza mit der von der Wehrmacht verübten Leningrader Blockade vergleicht. Putins übergeordnetes Ziel, die Zerschlagung der Ukraine, will er bekanntlich als »Entnazifizierung« verstanden wissen, weil »der kollektive Westen«, so Putin am 7. Juli 2022, »einen Genozid an den Menschen im Donbass befeuert und gerechtfertigt hat«. Dazu passt die Aussage seines Außenministers Sergej Lawrow, der auf die Frage, wie es eine Nazifizierung der Ukraine geben könne, wenn deren Präsident doch Jude sei, am 1. Mai 2022 erklärt hatte: »Ich kann mich irren. Aber Adolf Hitler hatte auch jüdisches Blut. Das heißt überhaupt nichts. Das weise jüdische Volk sagt, dass die eifrigsten Antisemiten in der Regel Juden sind.« Die Aussage Lawrows ist nicht nur wegen der Anspielung auf die »Protokolle der Weisen von Zion« gravierend, sondern auch, weil er Selenskyj mit Hitler vergleicht, weil er Hitler judaisiert und der Meinung ist, dass hinter dem Antisemitismus überwiegend Juden stecken. Keine Absurdität kann groß genug sein, solange sie sich nur gegen Juden richtet.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Shoah after Gaza

In 1977, a year before he killed himself, the Austrian writer Jean Améry came across press reports of the systematic torture of Arab prisoners in Israeli prisons. Arrested in Belgium in 1943 while distributing anti-Nazi pamphlets, Améry himself had been brutally tortured by the Gestapo, and then deported to Auschwitz. He managed to survive, but could never look at his torments as things of the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

“What, for example, was the attitude of the intellectual in Auschwitz toward death? A vast, unsurveyable topic, which can be covered here only fleetingly, in double time! I will assume it is known that the camp inmate did not live next door to, but in the same room with death. Death was omnipresent. The selections for the gas chambers took place at regular intervals. For a trifle prisoners were hanged on the roll call grounds, and to the beat of light march music their comrades had to file past the bodies - Eyes right! - that dangled from the gallows. Prisoners died by the score, at the work site, in the infirmary, in the bunker, within the block. I recall times when I climbed heedlessly over piled-up corpses and all of us were too weak or too indifferent even to drag the dead out of the barracks into the open. But as I have said, people have already heard far too much about this; it belongs to the category of the horrors mentioned at the outset, those which I was advised with good intentions not to discuss in detail.

Here and there someone will perhaps object that the front-line soldier was also constantly surrounded by death and that therefore death in the camp actually had no specific character and posed no incomparable ques: tions. Must I even say that the analogy is false? Just as the life of the front-line soldier, however he may have suffered at times, cannot be compared with that of the camp inmate, death in battle and the prisoner's death are two incommensurables. The soldier died the hero's or victim's death, the prisoner that of an animal intended for slaughter. The soldier was driven into the fire, and it is true that his life was not worth much. Still, the state did not order him to die, but to survive. The final duty of the prisoner, however, was death. The decisive difference lay in the fact that the front-line soldier, unlike the camp inmate, was not only the target, but also the bearer of death. Figuratively expressed: death was not only the ax that fell upon him, but it was also the sword in his hand. Even while he was suffering death, he was able to inflict it. Death approached him from without, as his fate, but it also forced its way from inside him as his own will. For him death was both a threat and an opportunity, while for the prisoner it assumed the form of a mathematically determined solution: the Final Solution! These were the conditions under which the intellectual collided with death. Death lay before him, and in him the spirit was still stirring; the latter confronted the former and tried - in vain, to say it straight off - to exemplify its dignity.

The first result was always the total collapse of the esthetic view of death. What I am saying is familiar. The intellectual, and especially the intellectual of German education and culture, bears this esthetic view of death within him. It was his legacy from the distant past, at the very latest from the time of German romanticism. It can be more or less characterized by the names Novalis, Schopenhauer, Wagner, and Thomas Mann. For death in its literary, philosophic, or musical form there was no place in Auschwitz. No bridge led from death in Auschwitz to Death in Venice. Every poetic evocation of death became intolerable, whether it was Hesse's "Dear Brother Death" or that of Rilke, who sang: "Oh Lord, give each his own death." The esthetic view of death had revealed itself to the intellectual as part of an esthetic mode of life; where the latter had been all but forgotten, the former was nothing but an elegant trifle. In the camp no Tristan music accompanied death, only the roaring of the SS and the Kapos. Since in the social sense the death of a human being was an occurrence that one merely registered in the so-called Political Section of the camp with the set phrase "subtraction due to death," it finally lost so much of its specific content that for the one expecting it, its esthetic embellishment in a way became a brazen demand and, in regard to his comrades, an indecent one.

After the esthetic view of death crumbled, the intellectual faced death defenselessly. If he attempted nonetheless to establish an intellectual and metaphysical relationship to it, he ran up against the reality of the camp, which doomed such an attempt to failure. How did it work in practice? To put it briefly and tritely: just like his unintellectual comrade, the intellectual inmate did not occupy himself with death, but with dying. Then, however, the entire problem was reduced to a number of concrete considerations. For example, there was once a conversation in the camp about an SS man who had slit open a prisoner's belly and filled it with sand. It is obvious that in view of such possibilities one was hardly concerned with whether, or that, one had to die, but only with how it would happen. Inmates carried on conversations about how long it probably takes for the gas in the gas chamber to do its job. One speculated on the painfulness of death by phenol injections. Were you to wish yourself a blow to the skull or a slow death through exhaustion in the infirmary? It was characteristic for the situation of the prisoner in regard to death that only a few decided to "run to the wire," as one said, that is, to commit suicide through contact with the highly electrified barbed wire. The wire was after all a good and rather certain thing, but it was possible that in the attempt to approach it one would be caught first and thrown into the bunker, and that led to a more difficult and more painful dying. Dying was omnipresent, death vanished from sight.

Now of course, no matter where you are, the fear of death is essentially the fear of dying, and Franz Borkenau's claim that the fear of death is the fear of suffocation holds true also for the camp. For all that, if one is free it is possible to entertain thoughts of death that at the same time are not also thoughts of dying, fears of dying. Death in freedom, at least in principle, can be intellectually detached from dying: socially, by infusing it with thoughts of the family that remains behind, of the profession one leaves, and mentally, through the effort, while still being, to feel a whiff of Nothingness. It goes without saying that such an attempt leads nowhere, that death's contradiction cannot be resolved. Still, the effort contains its own intrinsic dignity: the free person can assume a certain spiritual posture toward death, because for him death is not totally absorbed into the torment of dying. The free person can venture to the out most limit of thought, because within him there is still a space, however tiny, that is without fear. For the prisoner, however, death had no sting, not one that hurts, not one that stimulates you to think. Perhaps this explains why the camp inmate and it applies equally to the intellectual as well as to the unintellectual did experience agonizing fear of certain kinds of dying, but scarcely an actual fear of death. If I may speak of myself, then let me assert here that I never considered myself to be especially brave and probably also am not. Yet, when they once fetched me from my cell after I already had a few months of punitive camp behind me and the SS man gave me the friendly assurance that now I was to be shot, I accepted it with perfect equanimity. "Now you're afraid, aren't you?" the man - who was just having fun - said to me. "Yes," I answered, but more out of complaisance and in order not to provoke him to acts of brutality by disappointing his expectations. No, we were not afraid of death. I clearly recall how comrades in whose blocks selections for the gas chambers were expected did not talk about it, while with every sign of fear and hope they did talk about the consistency of the soup that was to be dispensed. The reality of the camp triumphed effortlessly over death and over the entire complex of the so-called ultimate questions. Here, too, the mind came up against its limits.

All those problems that one designates according to a linguistic convention as "metaphysical" became meaningless. But it was not apathy that made contemplating them impossible; on the contrary, it was the cruel sharpness of an intellect honed and hardened by camp reality. In addition, the emotional powers were lacking with which, if need be, one could have invested vague philosophic concepts and thereby made them subjectively and psychologically meaningful. Occasionally, perhaps that disquieting magus from Alemannic regions came to mind who said that beings appear to us only in the light of Being, but that man forgot Being by fixing on beings. Well now, Being. But in the camp it was more convincingly apparent than on the outside that beings and the light of Being get you nowhere. You could be hungry, be tired, be sick. To say that one purely and simply is, made no sense. And existence as such, to top it off, became definitively a totally abstract and thus empty concept. To reach out beyond concrete reality with words became before our very eyes a game that was not only worthless and an impermissible luxury but also mocking and evil. Hourly, the physical world delivered proof that its insufferableness could be coped with only through means inherent in that world. In other words: nowhere else in the world did reality have as much effective power as in the camp, nowhere else was reality so real. In no other place did the attempt to transcend it prove so hopeless and so shoddy. Like the lyric stanza about the silently standing walls and the flags clanking in the wind, the philosophic declarations also lost their transcendency and then and there became in part objective observations, in part dull chatter. Where they still meant something they appeared trivial, and where they were not trivial they no longer meant anything. We didn't require any semantic analysis or logical syntax to recognize this. A glance at the watchtowers, a sniff of burnt fat from the crematories sufficed.” (pages 15 - 19)

#amery#améry#jean amery#jean améry#at the mind���s limits#aushwitz#naziism#wwii#holocaust#bataille#georges bataille#nietzsche#books#bookshelf#library

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

„Wenn aus dem geschichtlichen Verhängnis der Juden- beziehungsweise Antisemitenfrage, zu dem durchaus auch die Stiftung des nun einmal bestehenden Staates Israel gehören mag, wiederum die Idee einer jüdischen Schuld konstruiert wird, dann trägt hierfür die Verantwortung eine Linke, die sich selber vergisst.“ — Jean Améry, Der ehrbare Antisemitismus (1969)

Postmoderner Antisemitismus – Judenfeindschaft als „Wokeness“

(Vortrag von Dr. Ingo Elbe; gehalten am 14. Juni 2022, 19.30 Uhr)

Seit einigen Jahren wird die Frage diskutiert, ob ein „neuer“ oder „ehrbarer Antisemitismus“ (Jean Améry) nicht längst zum festen Bestandteil eines postmodernen Antirassismus geworden ist. In diesem von Michel Foucault, Edward Said oder Judith Butler inspirierten postmodernen Diskurs findet sich nämlich ein systematischer Zusammenhang von begrifflicher Einebnung und Verleugnung des Antisemitismus, Relativierung des Holocaust, De-Thematisierung vor allem der islamischen Judenfeindschaft und Ressentiment gegen Israel. Dieser akademische Diskurs beeinflusst auch den politischen Aktivismus, den Kunstbetrieb, viele Medien und zivilgesellschaftliche Institutionen. Im Vortrag wird vor allem der genuin ‚anti-identitär‘ und pseudohumanistisch auftretende postmoderne Antisemitismus untersucht, der ein an den christlichen Judenhass erinnerndes „Jew-splitting“ (Bruno Chaouat) betreibt: Der „gute Jude“ ist neben dem toten Juden des Holocaust hier derjenige, der für Diaspora, Zerstreuung und Überschreitung der eigenen Identität durch gewaltlose Auslieferung an ‚den Anderen‘ steht, während der „böse Jude“ als verstockter zionistischer Nationalist und Siedlerkolonialist betrachtet wird, dessen Ideen souveräner Identität und Selbstverteidigung dem ewigen Frieden der postnationalen und multikulturellen Gesellschaft im Wege stehen. Juden dürfen hier nur noch existieren, wenn sie ‚konvertieren‘, ihre Identität negieren und auf Selbstverteidigung verzichten.

Dr. Ingo Elbe ist wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter und Privatdozent am Institut für Philosophie der Universität Oldenburg. Zum Thema publizierte er zuletzt: Postmoderner Antisemitismus auf haGalil.com – Jüdisches Leben online (https://www.hagalil.com/2022/03/postm...) sowie The Anguish of Freedom. Is Sartre’s existentialism an appropriate foundation for a theory of antisemitism? In: Antisemitism Studies/April 2020. Aktuelles Buch: Gestalten der Gegenaufklärung. Untersuchungen zu Konservatismus, politischem Existentialismus und Postmoderne. (2. Aufl. Würzburg 2021), in dem auch die Themen Antisemitismus und Holocaustrelativierung behandelt werden (daraus online zugänglich: “… it’s not systemic”. Antisemitismus im postmodernen Antirassismus. (https://www.rote-ruhr-uni.com/cms/tex...) sowie Die „Verschwörung der Asche von Zion“. Anmerkungen zum postkolonialen Angriff auf die Singularität des Holocaust (https://www.kritiknetz.de/antizionism...)

--- serious ! talk - Vortragsreihe der Jüdischen Gemeinde Kassel und des Sara Nussbaum Zentrums für Jüdisches Leben Wie geht man mit aktuellem Judenhass, gerade im künstlerischen Kontext, um? Die Anfang des Jahres geäußerten Vorwürfe gegen die documenta fifteen und die kürzlich angekündigte Gesprächsreihe der Kasseler Kunstschau machen diese Frage hoch aktuell. Die Jüdische Gemeinde Kassel und das Sara Nussbaum Zentrum für Jüdisches Leben veranstalteten vor diesem Hintergrund eine Vortragsreihe mit dem Titel „serious ! talk“ (engl. „ernsthaftes Gespräch“). Zu Wort kamen Experten zu gegenwärtigen Formen des Antisemitismus in der Kunst und im wissenschaftlichen Betrieb.

Hintergrund der Vortragsreihe: „Das Sara Nussbaum Zentrum beschäftigt sich in seiner Arbeit seit sechs Jahren erfolgreich in Ausstellungen, Bildungsarbeit, Veranstaltungen und Aktionen mit Themen rund um Antisemitismus und jüdisches Leben in Kassel und in der Region“, so Elena Padva, Leiterin des SNZ. Der Blick auf die Gästeliste der documenta-Reihe habe nun gezeigt, dass weitere personelle Schwerpunkte nötig und auch möglich seien. Auch Josef Schuster, Präsident des Zentralrats der Juden in Deutschland, hatte sich in dieser Woche in einem Brief an Kulturstaatsministerin Claudia Roth zur Debatte geäußert. „Gegen Antisemitismus helfen nur klare Bekenntnisse und noch viel mehr, entschlossenes politisches Handeln auf jeder Ebene von Politik, Kunst, Kultur und Gesellschaft“, schreibt Schuster. Von dieser Verantwortung dürfe sich niemand – auch nicht im Namen der Kunstfreiheit – freisprechen. „Wir können dieser Haltung nur vollumfänglich zustimmen“, sagt Ilana Katz, Vorsitzende der Jüdischen Gemeinde Kassel.

--- Hier könnt ihr unsere Arbeit weiterverfolgen: Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/saranussbaum...

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/saranussbau...

Website: https://sara-nussbaum-zentrum.de/

0 notes

Quote

The expectation of help, the certainty of help, is indeed one of the fundamental experiences of human beings, and probably also of animals.

Jean Améry, Die Tortur

Art by Shoko Uemura

1 note

·

View note

Text

Une famille à louer [Family for rent] (Jean-Pierre Améris, 2015)

#comedy film#long métrage#Virginie Efira#France#Europe#Jean-Pierre Améris#François Morel#Philippe Rebbot#amour#Une famille à louer#Family for rent#Édith Scob#relationships#Benoît Poelvoorde#Belgium#famille#family#laughters#life#cinema français#french movies#Pauline Serieys#motherhood#European cinema#single mother#shop lifting#entertainment#Familie zu vermieten#romance#Lucie Mandini

1 note

·

View note

Text

la joie de vivre (jean pierre améris, 2012)

30 notes

·

View notes