#Lower Eocene fossil

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Aetobatus irregularis Fossil Ray Plate | Lower Eocene | Bracklesham Bay Sussex UK | Authentic Fossil with COA | Alice Purnell Collection

Aetobatus irregularis Fossil Ray Plate | Lower Eocene | Bracklesham Bay, Sussex, UK

Step back in time to the Lower Eocene Epoch with this exquisite Aetobatus irregularis Fossil Ray Plate, a testament to ancient marine ecosystems that thrived around 56 to 47.8 million years ago. Discovered in the fossil-rich strata of Bracklesham Bay, Sussex, UK, this rare specimen is part of the prestigious Alice Purnell Collection, one of the largest fossil collections globally.

Geology & Fossil Information:

Species: Aetobatus irregularis (Eagle Ray)

Fossil Type: Ray Plate

Geological Period: Lower Eocene (Ypresian Stage, ~56 - 47.8 million years ago)

Location Found: Bracklesham Bay, Sussex, United Kingdom

The Aetobatus irregularis is a member of the eagle ray family, known for its distinctive, flat body and broad dental plates adapted for crushing hard-shelled prey such as mollusks and crustaceans. This fossilized ray plate showcases the complex dentition that highlights the evolutionary sophistication of this ancient species.

Key Features:

100% Genuine Fossil Specimen

Includes a Certificate of Authenticity

From the prestigious Alice Purnell Collection

Actual specimen shown – Scale rule squares/cube = 1cm (full sizing available in the photo)

This fossil is perfect for collectors, educators, and enthusiasts of paleontology and natural history. The provided photograph depicts the exact specimen you will receive, ensuring complete transparency and authenticity.

Secure this rare Eocene fossil today and own a remarkable piece of prehistoric marine life!

#Aetobatus irregularis Fossil#Fossil Ray Plate#Eocene Fossil#Lower Eocene Fossil#Bracklesham Bay Fossil#Sussex Fossil#UK Fossils#Genuine Fossil#Fossil with Certificate#Alice Purnell Collection#Rare Eocene Fossil#Paleontology Collectible#Fossil Collector Item#Natural History Fossil#Fossil Ray Teeth#Marine Fossil#Prehistoric Fish Fossil

0 notes

Text

Round 3 - Reptilia - Psittaciformes

(Sources - 1, 2, 3, 4)

Our next order of birds are the Psittaciformes, commonly called “psittacines” or “parrots”. Psittaciformes contain the families Cacatuidae (“cockatoos”), Psittacidae (“holotropical parrots”), Psittrichasiidae (“black parrots” and “vasa parrots”), Psittaculidae (“Old World parrots”), and Strigopidae (“New Zealand parrots”).

Parrots are some of the most well known and recognized tropical birds. They have large, strong, sharply downcurved beaks, an upright stance, and clawed, zygodactyl feet (two toes facing forward and two back). They are the only animals that display true tripedalism, using their beak as an extra limb to generate propulsive forces equal to or greater than those generated by the limbs of primates when climbing vertical surfaces. They travel with cyclical tripedal gaits when climbing. Along with corvids, they are considered the most intelligent birds, and are able to use tools, solve puzzles, and mimic human speech; some have been shown to even associate meaning to human words. Most parrots feed on plant material like seeds, nuts, fruit, and buds. Some species eat small animals, eggs, and/or carrion, and lories and lorikeets are specialized for feeding on nectar and fruit juice. Parrots are found on all tropical and subtropical continents and regions including Australia and Oceania, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Central America, South America, and Africa, with the greatest diversity coming from Australasia and South America.

Most parrots are social animals which live in large flocks, and hold no territories other than their nesting sites. All are monogamous, and the pair bonds of the parrots and cockatoos are strong, with a pair remaining close during the nonbreeding season even if they join larger flocks. Almost all parrots nest in cavities such as tree hollows or termite mounds. In most cases, both parents excavate the nest, though in many, only the female incubates the eggs while the male brings her food and guards the nest. Their young are altricial, hatched naked and helpless.

A single 15 mm (0.6 in) fragment from a large lower bill (UCMP 143274), found in deposits from the Lance Creek Formation had been thought to be the oldest parrot fossil, having originated from the Late Cretaceous period. However, this fossil is more likely to have come from a parrot-like caenagnathid oviraptorosaur. It is still generally assumed that the Psittaciformes were present during the K-Pg extinction, 66 million years ago, with modern parrots evolving in the Eocene, around 50 million years ago.

Propaganda under the cut:

A large macaw can have a bite force of 35 kg/cm2 (500 lb/sq in), close to that of a large dog.

Most species are capable of using their feet to manipulate food and other objects with a high degree of dexterity, in a similar manner to a human using their hands. A study conducted with Australian parrots has demonstrated that they exhibit "handedness", a distinct preference with regards to the foot they use to pick up food, with adult parrots being almost exclusively "left-footed" or "right-footed", and with the prevalence of each preference within the population varying by species.

Parrots eat a lot of seeds, and in many cases where they are seen consuming fruit, they are actually just eating the fruit to get at the seed. As seeds often have poisons that protect them, parrots will carefully remove seed coats and other chemically defended fruit parts prior to ingestion. Many species in the Americas, Africa, and Papua New Guinea also consume clay, which releases minerals and absorbs toxic compounds from the gut.

The large, nocturnal, flightless Kākāpō (Strigops habroptilus) (see gif above) is the heaviest parrot, weighing around 4.0 kg (8.8 lb). They are world’s only living flightless parrots, having evolved in New Zealand where they did not have to worry about land predators. Today, the Kākāpō is critically endangered, due to the introduction of mammalian predators like domestic cats, rats, domestic ferrets, and stoats. The current total known population of living individuals is 244, with all known individuals being named and tagged.

The Kea (Nestor notabilis) (image 4), also from New Zealand, is the only alpine parrot, living in the forested and alpine regions of the South Island. Kea are known for their intelligence and curiosity, both vital to their survival in a harsh mountain environment. Kea can solve logical puzzles, such as pushing and pulling things in a certain order to get to food, and will work together to achieve objectives. They have been filmed preparing and using tools. Their natural curiosity and urge to explore and investigate makes this bird both a pest for residents and an attraction for tourists, and they are known to play with (and damage) backpacks, boots, skis, snowboards, and cars. They are known to “steal” unguarded items of clothing, car keys, passports, and rubber parts of cars. Unfortunately, this naturally curious and trusting behavior has led to the endangered bird being illegally killed by poachers in some instances.

Some parrots are active predators of other animals. Golden-winged Parakeets (Brotogeris chrysoptera) prey on aquatic snails. The bulk of the Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoo’s (Zanda funerea) diet consists of grubs. While the Kea’s main source of protein is carrion, it also uncommonly preys on Domestic Sheep (Ovis aries), as well as other birds (including shearwater chicks), and small mammals (including rabbits and mice). Another New Zealand parrot, the Antipodes Parakeet (Cyanoramphus unicolor) is known to prey on adult Grey-backed Storm Petrels (Garrodia nereis) by entering their burrows while they incubate their eggs.

Lories, lorikeets (tribe Loriini), Hanging Parrots (genus Loriculus), and Swift Parrots (Lathamus discolor) are primarily nectar and pollen eaters, having adaptations specifically for this diet, including tongues with brush-like tips.

The Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis) is an extinct species of conure that was once native to the Eastern, Midwest, and Plains states of the United States. It was the only indigenous parrot within its range, and one of only three parrot species native to the United States (the only remaining is the Green Parakeet [Psittacara holochlorus] in some parts of Texas, while the Thick-billed Parrot [Rhynchopsitta pachyrhyncha] has since been extirpated from the US). Carolina Parakeets were hunted, both for the decorative use of their colorful feathers in women's hats, and for reduction of crop predation. Deforestation in the 18th and 19th centuries also likely played a significant role. They were also captured for the pet trade and competed for nest sites with the introduced European Honeybee (Apis mellifera). The last confirmed sighting in the wild of a Carolina Parakeet was in 1910. The last known specimen, a male named Incas, died at the age of 33 at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918, and the species was declared extinct in 1939.

The endangered El Oro Parakeet (Pyrrhura orcesi) is one of the few parrot species known to breed cooperatively. One breeding pair may be accompanied by up to six helpers.

The Golden Parakeet (Guaruba guarouba) (image 3) is the only other parrot known to breed cooperatively, and they may also be polygamous breeders, with multiple females contributing to a clutch.

The Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus) is one of the very few parrots known to build a nest, and even among them it is unique. Monk Parakeets breed colonially, building a single huge nest, with separate entrances for each pair. These colonies can become quite large, with pairs occupying separate "apartments" in composite nests that can reach the size of a small car. These “apartments” may attract other tenants who will nest alongside the colony, such as pigeons, sparrows, American Kestrels (Falco sparverius), Yellow-billed Teals (Anas flavirostris), and mammals like squirrels.

The Burrowing Parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus) excavates burrows that can be as much as 3 m deep into a cliff-face, connecting with other tunnels to create a labyrinth, ending in a nesting chamber. They nest in large colonies, some of the largest of any parrots, up to 70,000 strong, creating “cities” in cliff faces during the breeding season.

Parrots do not have vocal cords, so sound is accomplished by expelling air across the mouth of the trachea in the organ called the syrinx. Different sounds are produced by changing the depth and shape of the trachea.

A study by scientist Irene Pepperberg suggested a high learning ability in a Grey Parrot (Psittacus erithacus) named Alex. Alex was trained to use words to identify objects, describe them, count them, and even answer complex questions such as "How many red squares?" with over 80% accuracy. N'kisi, another Grey Parrot, has been shown to have a vocabulary of around a thousand words, and has displayed an ability to invent and use words in context in correct tenses.

As parrots are highly intelligent and social, an absence of stimuli from members of their own kind can delay the development of young birds. This was demonstrated by a group of Vasa Parrots (genus Coracopsis) kept in tiny cages with Domestic Chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus) from the age of three months; at nine months, these birds still behaved in the same way as three-month-olds, but had adopted some chicken behaviour. Parrots kept as pets or in detrimental environments can, if deprived of stimuli, develop stereotyped and harmful behaviours like self-mutilating. Keepers working with parrots often have dedicated environmental enrichment plans to keep parrots stimulated.

One-third of all parrot species are threatened by extinction, with a higher aggregate extinction risk than any other comparable bird group. Parrots are subjected to more exploitation than any other group of wild birds, and their wild populations have been diminished by trapping both adults and chicks for the pet trade. Half of all parrots live in captivity, with the vast majority of these living as pets in people's homes. Despite many breeders existing, parrots are not domesticated, and very few make good pets as they have complex social, dietary, and enrichment needs, they have strong bites and need to chew, and are naturally very loud. They are also long-term commitments as, depending on species, they can live from 15 to 80+ years, all while requiring the same levels of attention, care, and intellectual stimulation akin to that required by a three-year-old child to survive. Parrot rescue groups estimate that most parrots are surrendered and rehomed through at least five homes before reaching their permanent destinations, or before dying prematurely from unintentional or intentional neglect and abuse. If considering a pet parrot, make sure you have the time, money, and emotional energy to devote to these wild animals, know what you’re getting into, and make sure you adopt from a rescue so as not to fuel this unethical pet trade.

#I say that last point as someone with a pet conure#I love her but if I ever get another bird it’s going to be one that’s actually domesticated#animal polls#round 3#reptilia#Psittaciformes

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apatemyids were a group of unique early placental mammals that lived during the first half of the Cenozoic, known from North America, Europe, and Asia. Due to their specialized anatomy their evolutionary relationships are rather murky (they were traditionally part of the convoluted mess that was "Insectivora"), but currently they're thought to be a very early offshoot of the Euarchontoglires, the branch of placentals that includes modern rodents, lagomorphs, treeshrews, colugos, and primates.

Living in what is now western Europe during the mid-Eocene, around 47 million years ago, Heterohyus nanus was a small apatemyid about 30cm long (~12") – although just over half of that length was made up of its tail.

Like other apatemyids it had a proportionally big boxy head, with large forward-pointing rodent-like incisors in its lower jaw and hooked "can-opener-shaped" incisors in its upper jaw.

Example of an apatemyid skull from the closely related American genus Sinclairella. From Samuels, Joshua X. "The first records of Sinclairella (Apatemyidae) from the Pacific Northwest, USA." PaleoBios 38.1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.5070/P9381053299

The rest of its body was rather slender, and fossils with soft tissue preservation from the Messel Pit in Germany show that it had a bushy tuft of longer fur at the end of its long tail.

But the most distinctive feature of apatemyids like Heterohyus were their fingers, with highly elongated second and third digits resembling those of modern striped possums and aye-ayes. This suggests they had a similar sort of woodpecker-like ecological role, climbing around in trees using their teeth to tear into bark and expose wood-boring insect holes, then probing around with their long fingers to extract their prey.

———

NixIllustration.com | Tumblr | Patreon

References:

Kalthoff, D. C., W. Von Koenigswald, and C. Kurz. "A new specimen of Heterohyus nanus (Apatemyidae, Mammalia) from the Eocene of Messel (Germany) with unusual soft part preservation." Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg 252 (2004): 1-12. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263714512_A_new_specimen_of_Heterohyus_nanus_Apatemyidae_Mammalia_from_the_Eocene_of_Messel_Germany_with_unusual_soft-part_preservation

Koenigswald, W. V., and H-P. Schierning. "The ecological niche of an extinct group of mammals, the early Tertiary apatemyids." Nature 326.6113 (1987): 595-597. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232761846_The_ecological_niche_of_early_Tertiary_apatemyids_-_extinct_group_of_mammals

Samuels, Joshua X. "The first records of Sinclairella (Apatemyidae) from the Pacific Northwest, USA." PaleoBios 38.1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.5070/P9381053299

Silcox, Mary T., et al. "Cranial anatomy of Paleocene and Eocene Labidolemur kayi (Mammalia: Apatotheria), and the relationships of the Apatemyidae to other mammals." Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 160.4 (2010): 773-825. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00614.x

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#heterohyus#apatemyidae#apatotheria#euarchontoglires#mammal#art#convergent evolution#exceptional preservation#it's like if a rat tried to become an aye-aye

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

Insular Sebecids of the Caribbean

Still catching up with posts I need to write given that the past two weeks were just major paper after major paper. Given that the last two I did were on the recently named sebecoid Tewkensuchus (more here) and on the unrecognized diversity that slumbers among modern American crocodiles (see here), it sure would be convenient if there was one that sorta ties into both of those....

Oh yeah, what convenient timing for "A South American sebecid from the Miocene of Hispaniola documents the presence of apex predators in early West Indies ecosystems", written by Lázaro W. Viñola López and colleagues and published literally just last night as of the time I'm writing this.

What's this paper about? Simple, the description of sebecid fossil remains from the island of Hispaniola. Sebecids of course being terrestrial crocodile relatives that lived throughout much of the early Cenozoic in South America. The remains admittedly aren't anything to write home about, consisting of two vertebrae and a tooth with the group's iconic blade-like serrated morphology (aka ziphodonty), but the implications are nonetheless quite interesting. Not only is it the best evidence we have for insular sebecids and would have been the islands apex predator, but it also extends the survival of Sebecidae by perhaps up to 5 million years. This means the group might have survived until the Early Pliocene.

The Hispaniola sebecid, tentatively assigned to Sebecus sp., as illustrated by Machuky Paleoart

Now full disclosure, these remains are NOT the first evidence of what could be sebecids from the Caribbean. Previous discoveries include teeth from the early Miocene of Cuba as well as the early Oligocene of Puerto Rico. However, what makes the Hispaniola remains so much more important is surprisingly the presence of vertebrae. Hear me out. Sure, the teeth are iconic and easily identifyable, however, ziphodont teeth are not unique to sebecids and have also evolved independently in more "modern" crocodiles such as planocraniids and mekosuchines. Sure, mekosuchines were definitely not hanging out on Hispaniola and planocraniids are accepted to have died out during the Eocene, but nonetheless this means that ziphodont teeth could also belong to another type of croc. HOWEVER, the vertebrae from Hispaniola are described as amphicoelous, while animals closer to todays crocs would have procoelous vertebrae. Ergo, ziphodont teeth + amphicoelous vertebrae = sebecid, making these remains the first unambiguous evidence for Caribbean sebecids.

A simplified phylogeny showing the repeated evolution of ziphodont teeth in crocodyliforms while also highlighting the diferences in notosuchian and eusuchian vertebrae.

Case and point for why thats important? Well while the remains from Cuba and Puerto Rico are most likely also sebecids based on their age and geography, there are even older fossil remains of a ziphodont croc from the Middle Eocene of Jamaica. While sebecids were already around back then, so were the planocraniids, hooved crocodile-relatives found across North America and Eurasia. And since Eocene Jamaica has faunal similarities with North America, this particular ziphodont is more likely to be a planocraniid than a sebecid.

While the Cuban and Puerto Rican teeth are likely those of sebecids, the Eocene Jaimacan ziphodont croc could have easily been a planocraniid similar to the widespread genus Boverisuchus, illustrated here by Corbin Rainbolt.

Those that read my post on Tewkensuchus might remember my barely coherent ramblings about how confusing and poorly understood the paleogeography of sebecids is. Well for what its worth, if we ignore all the chaos caused by Europe's part in the equation, the South American history is relatively straight forward. The Paleogene record spans both remains found in the far South as well as Eocene records further north at lower latitudes. It's not entirely clear how sebecids got to the islands, but it is speculated that they could have rafted or even traveled across temporary land bridges that formed at times of lower sea levels. Whatever the case, by the early Oligocene sebecids seem to have made it to Puerto Rico and would have likely been isolated from the mainland and from other island populations when various marine passages opened, splitting the island chains. This may have been a blessing in disguise, as by the Miocene sebecids were restricted to tropical environments at low and mid latitudes and further habitat collapse, tied in part to the disappearance of the Pebas Mega Wetlands, eventually lead to their extinction on the mainland by the early Late Miocene.

But if the fossils from Hispaniola are anything to go by, then they clung onto life for another 5 million years in the Caribbean, retaining their spot as the islands apex predators until possibly as late as the Early Pliocene. Alas, they couldn't evoid extinction forever and unless we find even younger remains the Hispaniola sebecid represents the last hold out of the once diverse group Notosuchia.

Predator guilds and their distribution in South America throughout the Paleogene (a), Neogene (b) and late Quaternary (c).

But in a way, they didn't go without leaving their mark on the island. After sebecids went extinct, there seems to have been a push by native birds towards more terrestrial life, with some species losing the ability to fly alltogether. Some birds of prey seem to have taken up the mantle of terrestrial predator, leading to owls like Ornimegalonyx on Cuba and even the only distantly related Cuban crocodile threw its hat into the ring when it came for the spot of apex predator.

Top: A cuban crocodile hunting a small species of ground sloth, illustrated by Manusuchus Bottom: A general overview of the fauna found on Cuba during the Pleistocene, including flightless birds, cuban crocodiles and terrestrial owls, illustrated by Joschua Knüppe

#sebecidae#sebecus#sebecosuchia#notosuchia#pliocene#palaeoblr#prehistory#croc#crocodile#cuban crocodile#planocraniidae#pseudosuchia#long post#science news

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

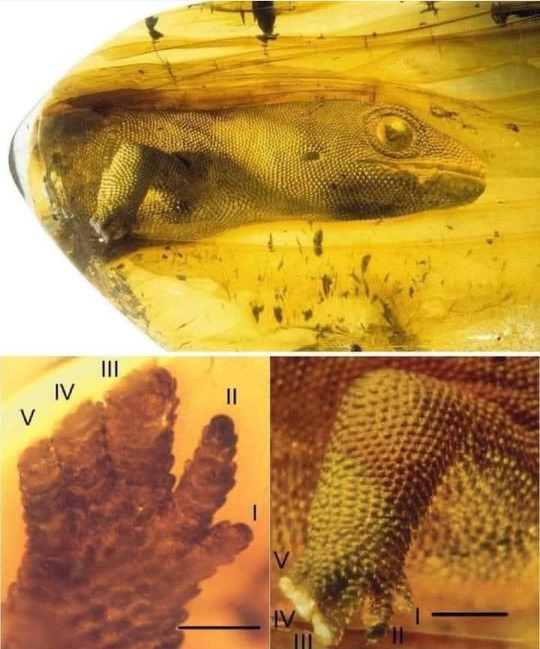

A 53-million-year-old gecko fossil was discovered almost perfectly preserved in Baltic amber. This Lower Eocene specimen represents a new genre and species, with a unique digital morphology, different from current geckos.

The 54-million-year-old Baltic Amber preserved key anatomical details, revealing surprising evolutionary adaptations. Unlike modern geckos, it displays primitive digital structures, which provides clues to the evolution of their locomotion.

They are believed to have developed adhesive pads multiple times in their evolutionary history, facilitating their adaptation to arboreal environments. This finding enriches our understanding of reptile evolution and past biological diversity.

The fossil highlights the importance of the Baltic amber as a window into the past, holding crucial evidence for science. A true treasure that connects modern biology to the origins of these fascinating creatures.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spectember D29: Speculative Biome

Is not an oddity for geologists to look at some strange landscape formations, many caused by singular events or just by erosion, but the most particularly perplexing ones have been made by what is not considered to be a thing from this world...

North America seems to be dotted with dozens of these structures and the remains of already fallen ones, looking like gigantic towers of more than a kilometer in height, structured like a strange tree shaped form, it rises like a testament of the biggest terrestrial organism known, a monster tree made of stone and shaped by the millions of years of constant growth by part of a singular organism.

In Wyoming there is the most intact and oldest specimen of such beings, bein nicknamed Heaven’s Tower, unique megaorganisms formed by thousands of individual slime like organisms that behave like a stromatolite as it accumulate over layers over layers of sediment and material it built its structure, the way it do it seems to comprehend a system of vessels that transport the material from the terrain, often hollowing the terrain below forming a large cave chamber system that accumulate water and organic matter, preserve itself from erosion protected by a microbial layer product of the same organism. The tower seems to often renovate itself by the use of a special slime covering every century based on studies of change of texture and viscosity in the tower surface, but from what accounts on different expeditions into the inner cave system denote that the whole Tower formed dozens of millions of years ago, from mining expeditions around the chamber as well drilling in the main structure it was found it preserved a decent amount of data in the form of layers created by the accumulation of minerals by the slime into the main structure like a terrestrial stromatolite, this giving a possible date of the formation of the original tree around the late Eocene or early Oligocene.

As well seems to be every 5 to 10 million years there is a process that allow the introduction of surface fauna that always ends up into the lower chamber, to be eventually isolated which seems to last for few million years until there is a occurring a total extinction of the inner fauna, caused by the replacement and collapse of a old layer as its being replaced by a new one of almost 20 m of thickness, so far from fossil record the last breach occurred around the late Pliocene, isolating the fauna that lived upon that time.

The way one of the Heaven’s Tower specimen grow or originate is pretty much unknown for the very long span of time it takes to even start forming, is believe one of these might find a specific and rich place to feed its structure, more or less an old volcanic region and slowly accumulate to form the megastructure that feed symbiotically by chemosynthesis from the igneous rocks and photosynthesis, as well there has been identified fossil remains of older already fallen Towers that also expose similar patterns of growing. The Heaven’s Tower of Wyoming is the last intact structure as many seems to have been destroyed by the last ice age, and will take millions of years to recover, this itself is a testament of a paradoxical being that is still investigated, as this being for many accounts seems to not share any significant relationship of any living organisms.

308 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Novembirb 15: Oasis in the Desert

Xenerodiops by @iguanodont

We FINALLY get to an ecosystem that isn't in Europe, North America, Antarctica, or Oceania - it's Jebel Qatrani Time!

(If you are as appalled as I am at the low sampling rates of fossil localities in Asia, South America, and Africa, welcome to the club, and support paleontologists who are from and work in countries from those continents!!!)

The Jebel Qatrani Formation is an ecosystem from Egypt at the end of the Eocene through the early Oligocene. It showcases the tropical forests, swamps, and marshes that existed at this time, emptying into the Tethys Sea. A wet and humid environment, it would have been a weird mixed ecosystem, with both the old and the new coexisting on the riverbanks. And, like in the forests and plains of Oligocene Europe, we see many modern bird groups show up for the first time here - and also very similar to their living relatives! This is a departure from the mammals in the region, which were unique and weird for the time period (though early members of modern groups are found here, too).

Palaeoephippiorhynchus by Bubblesorg

Being a wetland and humid environment, the main feature of the avifauna here are aquatic birds - many of which have close relatives today. Palaeoephippiorhynchus is the oldest known fossil stork, and was remarkably similar to the living Saddle-Billed Stork - even having the same upcurved bill. While it's uncertain if they're close relatives or not, it is possible that living Saddle-Bills are similar to this ancient form. There was also a mid-sized heron, a bird extremely similar to living Black-Crowned Night Herons, and Xenerodiops - a heron with a pointed and strong bill, curved downward - good for grabbing onto prey. It was a very sturdy, robust bird - even for a heron.

In addition, there was Goliathia - the fossil Shoebill! This bird had legs much like the living shoebill, and was similar enough in the limbs that it might be in the same genus! It probably lived very similarly to living shoebills, feeding on fish in the wetlands around it. What its beak would have looked like is uncertain - the closest living relative to the Shoebill is the Hammerkop, which has a very different skull. What their ancestral skull was, or what Goliathia's was, remains a mystery.

Goliathia by Antonio Rares Mihaila

But if you think I'm done with the water birds, you're very wrong - this is just the beginning! There was also an indeterminant cormorant, which had a very hooked and tapered beak; birds similar to living crowned cranes and others like living flufftails; early jacanas like Janipes which was bigger than all living jacanas but still had the large feet for floating on vegetation, showcasing the vegetation in these wetlands was sturdy enough to hold it up; other early jacanas smaller in size as well like Nupharanassa; and of course -

The Flamingos! Well, yes and no. There was an indeterminate crown-flamingo (ie in the group that all living flamingos are in), a bit bigger than a living lesser flamingo. But there was also Palaelodus - one of the "Grebe-Flamingos" or "Swimming-Flamingos", a long-lasting group of birds that first appear in the early Oligocene and lasted until possibly the Pleistocene! They looked superficially similar to living flamingos and were more closely related to them than to grebes, but they did have some similar characteristics to grebes as well - specifically having less of a kink in the neck, shorter lower legs, and flatter limb bones like those in grebes. They also had webbed feet, which would have allowed for diving or swimming. It also had a straight, conical bill, very unlike the bill of living flamingos.

Palaelodus by @alphynix

There were also perching birds, such as an early turaco very similar to the living genus Crinifer; and early eagles, ospreys, and other birds of prey that haven't really been named - mainly because they are very similar to living species, but so distant in time it seems unlikely they'd be in the same genus still... right? One, very similar to the living sea eagle, was found near the shore - indicating a similar ecology to its living relative. Another was almost identical to the living osprey, just smaller in size. And another was similar in size to living ospreys, but more robust than them. This place was filled with raptors!

Of course, I can't ignore the metaphorical elephant in the room. One of the most mysterious birds of the Jebel Qatrani is Eremopezus, a bird that has similarities to so many different groups of birds that its exact position is still a mystery. At this time it is thought to be a Palaeognath, possibly closely related to ostriches or maybe elephant birds - as the volant Lithornithids start to disappear, ratite-like Palaeognaths become more and more common. It was flightless, and probably lived similarly to modern ostriches and other ratites - as a a large herbivore, probably taking advantage of the wetland landscape and the abundance of food.

Eremopezus by @thewoodparable

Jebel Qatrani is such an important formation because it sheds light on the evolution of even more bird groups than those we see in former Laurasia (North America + Eurasia). And it is possible that many lineages we still have in Africa today have been around for thirty million years - and may have been very similar in ecology and appearance during that whole time. Given living birds react to changing climates by shifting with the ecosystems, it's possible that these lines of birds similarly followed the migration of wetlands and other habitats during the climate change to come, persisting to this day across the continent.

Sources:

Kampouridis, P., J. Hartung, F. J. Augustin. 2023. The Eocene-Oligocene Vertebrate Assemblages of the Fayum Depression, Egypt. The Phanerozoic Geology and Natural Resources of Egypt. Advances in Science, Technology, & Innovation. 373-405.

Mayr, 2022. Paleogene Fossil Birds, 2nd Edition. Springer Cham.

Mayr, 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance (TOPA Topics in Paleobiology). Wiley Blackwell.

Rasmussen, D. T., S. L. Olson, E. L. Simons. 1987. Fossil birds from the Oligocene Jebel Qatrani formation Fayum Province, Egypt. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 62(62): 1-20.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

A pair fossilized bird eggshell of a Gastornis sp. or the oospecies, Ornitholithus arcuatus from Bouches du Rhône, France. These Lower Eocene aged eggshells have a thickness of around 2 mm implying they were laid by giant birds like Gastornis which distinguishes it from smaller contemporary bird ootaxa like Ornitholithus biroi which has a 1mm thickness. The right specimen comes from Saint-Léger while the left comes from Saint-Antonin-sur-Bayon.

#fossils#bird#dinosaur#ootaxon#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#gastornis#ornitholithus#theropod#gastornithidae#ornitholithidae#eocene#cenozoic#prehistoric#science#paleoblr#ガストルニス#ガストルニス科#鳥#恐竜#化石#古生物学

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

From a 10 word prompt: tomato sunset fossil lute comparison sculpt tripartite egregious jaguar elongated

Ruins have been found in the depth of the south American jungle. A tripartite temple dedicated to a jaguar god, adorned with statues and bas-reliefs sculpted with great skills. The egregious scenes depict the slaughter of thousands men, women and children by what seems to be giant humanoid beings with elongated skulls. The sheer size of the temple and its adornments were the first signs of its non-human origins. One altar, standing in the midst of the bloody scene, had remain untouched and was still displaying a monstrous skull of an unknown creature. Twice the size of a Tyrannosaurus' skull, its bone structure has no known equivalent on earth and its chemical analysis point at an extraterrestrial origin. Later excavations revealed a lower chamber, located 300 meters under the temple. Accessible via a hidden door behind the altar and a steep tunnel. Three bodies, incredibly well preserved, were discovered encased in black pods made of highly polished crystal of unknown origin and composition. The bodies were the exact likeness of the giants depicted in the temple. Over 4 meters tall, with elongated skulls, no hair, a thick, rough greyish-red skin, four fingers and digitigrade feet. Wearing some tribal outfits made of unknown feathers, scaly leather and metal chains. Around the pods were carefully arranged a multitude of objects, all of them in a perfect state. Amongst them were a dozen of tomato like fruits, five time bigger than our largest species, still fresh and fragrant ; two astronomical models, one of our solar system and the other of an unknown system ; an impressive collection of animals skulls inhabiting the region in the Eocene, known to us by their fossils, but showing no sign of ageing in comparison to the specimens displayed in our museums ; and three musical instruments, a giant flute, a colossal musical horn of an unknown animal and a string instrument similar to a lute but designed for hands far larger than ours. Computers data show that the temple would have been aligned with the sun around 50 million years ago, letting its last rays drown the bas-reliefs in deep red at sunset. While waiting on adequate means to recover the bodies and transport them to be studied elsewhere, all contact with the scientific team was lost. When the recovery team arrived, nobody was present on the site and the three inhuman corpses were nowhere to be found and are still missing to this day.

#10 word prompt#short story#ancient civilizations#horror#south america#eocene#dinosaurs#extraterrestrial#elongated skulls#alien#ancient#archaeology

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Perplexicervix paucituberculata Mayr et al., 2023 (new species)

(Type specimen of Perplexicervix paucituberculata [scale bar = 10 mm], from Mayr et al., 2023)

Meaning of name: paucituberculata = little tuberculate [in Latin]

Age: Eocene (Ypresian), 54.6‒55 million years ago

Where found: London Clay Formation, Essex, U.K.

How much is known: Partial skeleton including vertebrae and fragments of the skull. Partial skeletons of two other individuals may also belong to this species.

Notes: P. paucituberculata was an unusual bird that had small bumps covering its neck vertebrae. This feature is shared with the only other species of Perplexicervix that had been previously named, P. microcephalon, as well as with Dynamopterus tuberculatus (a possible close relative to modern seriemas), both of which are from the Eocene of Germany. In fact, the neck vertebrae of P. microcephalon are even more extensively coated in these bumps than those of P. paucituberculata. Similar structures have not been observed in extant birds and their function is unknown. When they were first noticed in fossil birds, it was thought that they may have been the result of an ancient disease that no longer affects birds today. However, the fact that all known specimens of Perplexicervix preserving neck vertebrae have these bumps suggests that they were instead a typical part of their anatomy.

What type of extant bird Perplexicervix was most closely related to is also unclear. Similarities to waterfowl (specifically screamers) had been noted in earlier studies, and the type specimen of P. paucituberculata had been briefly mentioned in a previous paper as an early waterfowl. New specimens, however, indicate that Perplexicervix did not have the characteristic lower jaw anatomy shared by both waterfowl and landfowl. The describers of P. paucituberculata instead note that some of its bones bear noticeable resemblance to those of bustards, a group of often large, ground-dwelling birds that live in Afro-Eurasia and Australasia today. A close relationship with bustards would be very noteworthy if upheld by future research, given that early members of the bustard lineage are otherwise unknown from the Paleogene Period.

Reference: Mayr, G., V. Carrió, and A.C. Kitchener. 2023. On the "screamer-like" birds from the British London Clay: an archaic anseriform-galliform mosaic and a non-galloanserine "barb-necked" species of Perplexicervix. Palaeontologia Electronica 26: 33. doi: 10.26879/1301

#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Dinosaurs#Birds#Perplexicervix paucituberculata#Eocene#Europe#Neoaves#2023#Extinct

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

National Squirrel Appreciation Day

With their bushy tails and quick movements, these little creatures are a joy to watch as they scamper through the trees and hunt for nuts.

Squirrels are one of the most common animals that people see on a regular basis. These little creatures with a fluffy tail are practically everywhere–in cities, parks, college campuses and forests. They might live in trees or dig a hole in the ground to serve as a home. Some people might even say that squirrels are nuts for nuts, and can last through the harshest of winters without much trouble at all.

Squirrels have the ability to adapt to their environments quickly, they have a decent memory for some of the best locations for food, and they are super soft and fluffy. National Squirrel Appreciation Day encourages people to learn whatever they can about these creatures and admire them for their resilience in the wild.

History of National Squirrel Appreciation Day

With more than 250 species of squirrels that exist across five continents (excluding Australia and Antarctica), these little creatures are fairly prolific in most of the world. And that’s a great reason to appreciate them!

Squirrels are part of the Sciuridae family, which makes them cousins to a variety of rodents such as chipmunks, groundhogs, prairie dogs and other rodents. The earliest fossils of squirrels date back to the Eocene epoch which was perhaps more than 30 million years ago.

National Squirrel Appreciation Day was founded by wildlife rehabilitator Christy Hargrove, who is affiliated with the North Carolina Nature Center. According to Hargrove, people should consider helping to celebrate these creatures by putting out extra food and learning about the species.

Many rock funky hairstyles, survive rattlesnake bites and are extremely adorable, so appreciate the squirrels today by giving them some nuts to eat!

How to Celebrate National Squirrel Appreciation Day

National Squirrel Appreciation Day is a fun excuse to have a celebration on a random day in January. Share this holiday with friends and express that love for squirrels and try out some of these other ideas with the intention of enjoying the day and honoring squirrels:

Discover Fun Facts About Squirrels

Squirrels are considered by some to be beautiful creatures and, depending on the type of squirrel in question, it’s certainly possible to find out amazing facts about them. Try out some of these interesting facts and tidbits about squirrels to impress friends, family members and coworkers in honor of National Squirrel Appreciation Day:

An arctic squirrel can lower its temperature to below freezing to help survive the longest hibernation, which is over 8 months.

To survive in winter months, squirrels bury nuts and other treasures as a food source to come back to later. If they live in snowy climates, they may have to use their sense of smell to locate their stores, then dig through up to a foot of snow to retrieve the object.

The zig-zag patterns squirrels often run in usually means they are concerned about being chased by a predator. This clever little trick helps them to stay alive and avoid being caught by birds, foxes, cats, badgers and other predators.

Squirrels’ bodies are amazingly agile, which helps them run, climb, jump and more. They can turn their ankles 180 degrees while climbing, and can leap up to ten times the length of their own bodies.

Become More Knowledgeable About Squirrels

One great way to celebrate and appreciate squirrels is by learning more about the kinds of squirrels in each local area. Common squirrels in the United States, such as the American red squirrel, Eastern grey squirrel, and black squirrels all have their own habits and tricks that they do to survive. This is also a great day to take some time to learn about all kinds of other squirrels, even ones that are further away, especially the flying Japanese squirrels which are absolutely adorable.

Learn About Squirrel Eating Habits

It is obvious that squirrels, whether they’re ground, tree, or flying squirrels, all have their unique purpose in the global ecosystem. One way they do this is when squirrels work to bury nuts into the ground, which is a behavior called caching. This work they do not only allows them to save food for the winter months, but it also allows them to assist with fruit and tree renewal, because while some will be able to remember where they buried the nuts, others will not make it back to them.

Squirrels don’t just eat nuts and seeds, though, as their diet is much more diverse than many people think. They also eat many fruits, plants, insects, berries and vegetables. One interesting way squirrels contribute to the ecosystem is through eating mushroom spores. By eating the spores and then excreting them after they’re digested, the fungi help matter to decompose and give plants the nutrition they need to grow. Thus, squirrels help maintain the symbiotic relationship between plants and mushrooms and help spread the growth of plants all over the world.

Have a Squirrely Get-Together

For those who just love any reason to throw a party, this is a unique one! Host a squirrel-themed party in honor of the day. Have guests dress up as squirrels or other rodents, and give friends squirrel-themed gifts. Snacks and treats for the party could include squirrel shaped cookies decorated with icing, or really just about any type of food that is made out of nuts! Decorate with acorns, leaves and squirrels as well as other woodland creatures. It’s likely the guests will have never been to a party quite like this before!

Source

#Golden-mantled Ground Squirrel#California ground squirrel#California#USA#wildlife#original photography#flora#fauna#Pacific Ocean#Memphis#Charleston#Tennessee#South Carolina#Boston#Massachusetts#travel#Squirrel Appreciation Day#summer 2022#2018#2017#West Coast#SquirrelAppreciationDay#21 January#sand#meadow#tourist attraction#animal#Newberry National Volcanic Monument#Oregon#2023

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Aetobatus irregularis Fossil Ray Plate | Lower Eocene | Bracklesham Bay Sussex UK | Authentic Fossil with COA | Alice Purnell Collection

Aetobatus irregularis Fossil Ray Plate | Lower Eocene | Bracklesham Bay, Sussex, UK

Step back in time to the Lower Eocene Epoch with this exquisite Aetobatus irregularis Fossil Ray Plate, a testament to ancient marine ecosystems that thrived around 56 to 47.8 million years ago. Discovered in the fossil-rich strata of Bracklesham Bay, Sussex, UK, this rare specimen is part of the prestigious Alice Purnell Collection, one of the largest fossil collections globally.

Geology & Fossil Information:

Species: Aetobatus irregularis (Eagle Ray)

Fossil Type: Ray Plate

Geological Period: Lower Eocene (Ypresian Stage, ~56 - 47.8 million years ago)

Location Found: Bracklesham Bay, Sussex, United Kingdom

The Aetobatus irregularis is a member of the eagle ray family, known for its distinctive, flat body and broad dental plates adapted for crushing hard-shelled prey such as mollusks and crustaceans. This fossilized ray plate showcases the complex dentition that highlights the evolutionary sophistication of this ancient species.

Key Features:

100% Genuine Fossil Specimen

Includes a Certificate of Authenticity

From the prestigious Alice Purnell Collection

Actual specimen shown – Scale rule squares/cube = 1cm (full sizing available in the photo)

This fossil is perfect for collectors, educators, and enthusiasts of paleontology and natural history. The provided photograph depicts the exact specimen you will receive, ensuring complete transparency and authenticity.

Secure this rare Eocene fossil today and own a remarkable piece of prehistoric marine life!

#Aetobatus irregularis Fossil#Fossil Ray Plate#Eocene Fossil#Lower Eocene Fossil#Bracklesham Bay Fossil#Sussex Fossil#UK Fossils#Genuine Fossil#Fossil with Certificate#Alice Purnell Collection#Rare Eocene Fossil#Paleontology Collectible#Fossil Collector Item#Natural History Fossil#Fossil Ray Teeth#Marine Fossil#Prehistoric Fish Fossil

0 notes

Text

Round 3 - Reptilia - Phaethontiformes

(Sources - 1, 2, 3)

Our next order is Phaethontiformes, commonly known as “tropicbirds”. This is a small order, containing one living family, Phaethontidae, and three species within one genus: Phaethon.

Tropicbirds have predominantly white plumage with long, slender tail streamers which can be up to twice their body length. All four of their toes are connected with webbing. Their legs are small and weak, located far back on their body, making walking impossible, so they can only move on land by shuffling. Their bills are large, powerful and slightly downcurved. Tropicbirds frequently catch their prey by hovering and then plunge-diving, typically only into the surface-layer of the water. They eat mostly fish, especially flying fish (family Exocoetidae), and occasionally squid. Flying fish are usually caught in the air. They live on the open ocean, nesting on remote, rocky cliffs, or on offshore islands.

Tropicbirds are usually solitary or live in pairs in breeding colonies. Within breeding colonies, they engage in spectacular courtship displays. For several minutes, groups of 2–20 birds simultaneously and repeatedly fly around one another in large, vertical circles, while swinging their tail streamers from side to side. If the female likes the presentation of a male, she will join his flight display, and the pair will split off from the group to do a courtship display together. The pair will mate in the male’s prospective nest-site, usually a hole or crevice on the bare ground. The female will lay one white egg, which is spotted brown. Both parents incubate the egg, but mostly the female, while the male brings food to feed her. The chick will stay alone in the nest while both parents search for food, and they will feed the chick twice every three days until fledging, about 12–13 weeks after hatching. The parents will stop visiting the chick after it has fledged, and the chick will leave the nest on its own.

Tropicbirds are in the clade Eurypygimorphae, along with Eurypygiformes (“kagus” and “Sunbittern”). Tropicbirds were a very early branch of this clade, with well-preserved fossils known from the Early Paleocene. One waterbird, Novacaesareala hungerfordi, dates to the Late Cretaceous. If it is a tropicbird, that could put the origin of this order before the K-Pg extinction. Modern tropicbirds evolved in the Early Eocene.

(source)

Propaganda under the cut:

One of the Red-billed Tropicbirds’ (Phaethon aethereus) (image 1 and gif) aerial courtship displays involve a prospective pair gliding together, with one bird around 30 cm (12 in) above the other. The upper bird bends its wings down and the lower lifts its up, so they are almost touching. The two descend to about 6 meters (20 ft) above the sea before breaking off.

The ancient Chamorro People of the Mariana Islands called the White-tailed Tropicbird (Phaethon lepturus) (image 3) utak or itak, and believed that when it screamed over a house it meant that someone would soon die or that an unmarried girl was pregnant. Its call would kill anyone who didn't believe in it.

The Red-billed Tropicbird, a bird not native to Bermuda, was displayed in error on the $50 Bermudian dollar and was replaced in 2012 by the White-tailed Tropicbird, the tropicbird that can be found in Bermuda.

The Red-tailed Tropicbird’s (Phaethon rubricauda) (image 2) red tail streamers were highly prized by the Maori. The Ngāpuhi tribe of the Northland Region would look for and collect them off dead or stray birds blown ashore after easterly gales, trading them for greenstone with tribes from the south.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Massive asteroid impacts did not change Earth’s climate in the long term

Two massive asteroids hit Earth around 35.65 million years ago, but did not lead to any lasting changes in the Earth’s climate, according to a new study by UCL researchers.

The rocks, both several miles wide, hit Earth about 25,000 years apart, leaving the 60-mile (100km) Popigai crater in Siberia, Russia, and the 25-55 mile (40-85km) crater in the Chesapeake Bay, in the United States - the fourth and fifth largest known asteroid craters on Earth.

The new study, published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment, found no evidence of a lasting shift in climate in the 150,000 years that followed the impacts.

The researchers inferred the past climate by looking at isotopes (atom types) in the fossils of tiny, shelled organisms that lived in the sea or on the seafloor at the time. The pattern of isotopes reflects how warm the waters were when the organisms were alive.

Co-author Professor Bridget Wade (UCL Earth Sciences) said: “What is remarkable about our results is that there was no real change following the impacts. We expected the isotopes to shift in one direction or another, indicating warmer or cooler waters, but this did not happen. These large asteroid impacts occurred and, over the long term, our planet seemed to carry on as usual.

“However, our study would not have picked up shorter-term changes over tens or hundreds of years, as the samples were every 11,000 years. Over a human time scale, these asteroid impacts would be a disaster. They would create a massive shockwave and tsunami, there would be widespread fires, and large amounts of dust would be sent into the air, blocking out sunlight.

“Modelling studies of the larger Chicxulub impact, whichkilled off the dinosaurs,also suggest a shift in climate on a much smaller time scale of less than 25 years.

“So we still need to know what is coming and fund missions to prevent future collisions.”

The research team, including Professor Wade and MSc Geosciences student Natalie Cheng, analysed isotopes in over 1,500 fossils of single-celled organisms called foraminifera, both those that lived close to the surface of the ocean (planktonic foraminifera) and on the seafloor (benthic foraminifera).

These fossils ranged from 35.5 to 35.9 million years old and were found embedded within three metres of a rock core taken from underneath the Gulf of Mexico by the scientific Deep Sea Drilling Project.

The two major asteroids that hit during that time have been estimated to be 3-5 miles (5-8km) and 2-3 miles (3-5km) wide. The larger of the two, which created the Popigai crater, was about as wide as Everest is tall.

In addition to these two impacts, existing evidence suggests three smaller asteroids also hit Earth during this time – the late Eocene epoch – pointing to a disturbance in our solar system’s asteroid belt.

Previous investigations into the climate of the time had been inconclusive, the researchers noted, with some linking the asteroid impacts with accelerated cooling and others with episodes of warmer temperatures.

However, these studies were conducted at lower resolution, looking at samples at greater intervals than 11,000 years, and their analysis was more limited – for instance, only looking at species of benthic foraminifera that lived on the seafloor.

By using fossils that lived at different ocean depths, the new study provides a more complete picture of how the oceans responded to the impact events.

The researchers looked at carbon and oxygen isotopes in multiple species of planktonic and benthic foraminifera.

They found shifts in isotopes about 100,000 years prior to the two asteroid impacts, suggesting a warming of about 2 degrees C in the surface ocean and a 1 degree C cooling in deep water. But no shifts were found around the time of the impacts or afterwards.

Within the rock, the researchers also found evidence of the two major impacts in the form of thousands of tiny droplets of glass, or silica. These form after silica-containing rocks get vaporised by an asteroid. The silica end up in the atmosphere, but solidify into droplets as they cool.

Co-author and MSc Geosciences graduate Natalie Cheng said: “Given that the Chicxulub impact likely led to a major extinction event, we were curious to investigate whether what appeared as a series of sizeable asteroid impacts during the Eocene also caused long-lasting climate changes. We were surprised to discover that there were no significant climate responses to these impacts.

“It was fascinating to read Earth's climate history from the chemistry preserved in microfossils. It was especially interesting to work with our selection of foraminifera species and discover beautiful specimens of microspherules along the way.”

IMAGE: Microscope image of silica droplets, or microspherules, found in the rock. Credit Natalie Cheng / Bridget Wade

1 note

·

View note

Text

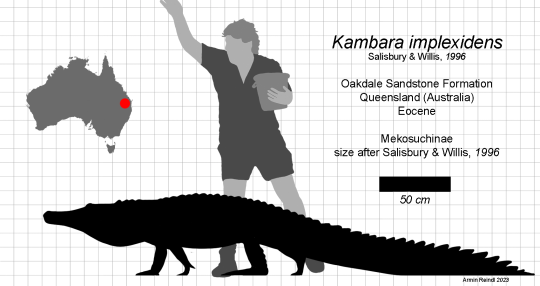

Kambara

Here I go again with croc stuff. Back to dealing with stuff thats longer established, let me tell you about Kambara, the oldest named mekosuchine and a genus that surprised me with the bulk of information behind it.

Kambara (which simply translates to "crocodile") is a genus of early mekosuchine that as of July 2023 contains four species, all from the Eocene of Queensland.

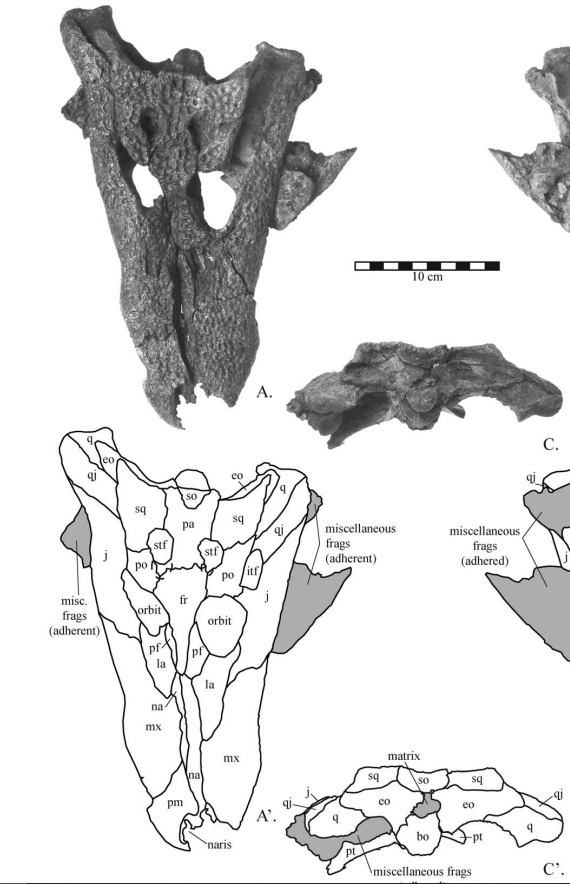

The first of these are Kambara murgonensis (Crocodile from Murgon) and Kambara implexidens (Interlocking Teeth Crocodile), both of which found at the same locality in Murgon, Queensland. The bones of both were in fact so intermingled that it was initially assumed that they represented a single species with highly variable anatomy, before the second species was recognized 3 years later.

There are a couple of differences between, but two are easiest to point out. For one, although being in the same size range (3-3.5 meters as adults), Kambara implexidens was a little more gracile. Furthermore, and the defining difference between them, K. implexidens (left) had interlocking teeth like a crocodile (bottom left), but K. murgonensis (right) had an overbite like an alligator (bottom right).

The next species named after these two was Kambara molnari (Molnar's Crocodile), but it's only known from much more limited material, the holotype being a lower jaw. Still some interesting information from this can be gathered. Which is that K. molnari seemingly represents an intermediate between interlocking dentition and an overbite. K. molnari wasn't found near Murgon, but in a different basin in Queensland, in the lower layers of the Rundle Formation.

Also from the Rundle Formation we have the most recently named and geologically youngest species, Kambara taraina (Crocodile Crocodile). Yeah the name is a bit redundant, but the logic of basing the species name on the Darumbal dialect as a proxy for language of the Bailai People is a nice one. Anyhow, K. taraina is a return to form as it is also known from good material like the first two, stemming from yet another large fossil bed possibly representing a mass death site. It had interlocking dentition like K. implexidens, BUT, unlike the oldest two species it did not coexist with the other Rundle Kambara. Instead, K. taraina came after K. molnari had presumably gone extinct.

Shown below the paratype of K. taraina, the holotype of K. implexidens and the holotype of K. molnari.

I won't get into phylogeny too much other than that its usually thought off as one of the earliest branching mekosuchines, but details vary. Lee and Yates found that Australosuchus may be more basal, while Ristevski et al. recover Kalthifrons as the earliest branch, in both cases Kambara is only the second branching. There is one slightly odd alternative. Rio and Mannion do find it as the oldest branching mekosuchine....but also regard neither Quinkana nor Australosuchus as members of the clade...and further seemingly find "Asiatosuchus" germanicus to nest within Kambara? And then there's 2 out of the 8 trees by Ristevski, which show Kambara as a close relative to modern Crocodylids. But neither of those results match the current concensus and Rio and Mannion in general has a lot I disagree with.

Much more interesting is the postcrania and the implications for the lifestyle of Kambara. Now while we have a lot of bones from the rest of the body, given they were found in literal bonebeds, we don't know much about it. Crocodile fossils that aren't skulls are rarely described in detail. But there's still some information out there. Important here are Stein et al. 2012 and Buchanan's PhD thesis (which included the description of K. taraina, the one part that was formally published). Both looked at the postcrania and found that there are some differences to modern crocs. To keep things brief, while the anatomy is not nearly as derived as in a fully terrestrial croc, it does seem to suggest that Kambara would have had an easier time performing the crocodilian highwalk (shown below).

Again, this does not necessarily mean it lived on land, if anything the circumstances of the animals death seems to imply the opposite, but its still interesting. Buchanan suggests that this could have been used to walk through shallow water or bottom walking, and Stein et al. do point out that some adaptations of the limbs could also be advantages while swimming. The most important part to suggest that Kambara still lived in the water is the skull tho (well and it being found in freshwater habitats). The skull looks still remarkably like that of your generalist croc, somewhat flattened, nostrils on top, raised eyes, all that kind of stuff. So it presumably hunted like a modern croc and lived like a modern croc.

The exact lifestyle remains obscure tho. Again, generalist seems like the best supported hypothesis, but we don't know what kind of difference interlocking teeth and the overbite make. Theres some speculation of course. Mook for example proposed that an overbite functions like carnassial teeth in mammals, slicing and breaking, whereas interlocking dentition is better for gripping. While the difference in robustness between K. murgonensis and K. implexidens isn't that great, it could be suggested that the more robust species sliced and broke larger prey while the more gracile one dealt with slippery fish or struggling animals. Muscle attachments are also important, and those seem to show that the most recent species, Kambara taraina with interlocking teeth, had the greatest bite force and thus may have fed on larger prey than all its predecessors. But again, a lot of this requires further looking into.

We do have one singular piece of evidence for diet. The shell of a turtle from the Rundle Formation clearly bearing the tooth marks of Kambara. The bite marks show that the turtle was bitten multiple times, likely in an attempt to position it better in the mouth to bring it into position with the crushing back teeth or to swallow. Fun fact, this behavior is referred to as "juggling". But as you can see from the first figure, the Kambara in question was a bit cocky and picked a turtle way too large, eventually giving up. Sadly the turtle was very injured, and tho the wounds healed slightly, it eventually died from an infection.

For the last section I briefly want to cover some last notes on Kambara murgonensis and Kambara implexidens, more specifically their coexistence. Now I covered the potential difference in hunting and prey preference already, but theres some other stuff to consider. For example, although found in the same locality, it is possible that this cohabitation was not the status quo. Given it is a mass death site at a locality that is known to have undergone wet and dry seasons, it is not unreasonable to assume that these animals died during a drought (another point against terrestrial life too, as they could have just left otherwise). Now even today crocs will gather in large groups in such situations, trying to make the most of dwindling water sources. This could mean that both species typically inhabited different biomes and only came together because they were forced to. The same might have also happend to Kambara taraina, causing increased aggression and explaining the many injured specimens found. Anyhow, it is also a possibility that they weren't divided by species, but by size, age and maturity. Buchanan points out that there are different habitat preferences between nesting females and juveniles, subadults and adult males in modern saltwater crocodiles. Big males prefer open water, nesting females areas with denser vegetation and subadults should avoid both as they threaten hatchlings and could be eaten by cannibalistic males. So that could also factor into the distribution of Kambara. And notably, it is pointed out that the Murgon site preserves both hachlings and egg shales, but seems to lack animals of intermediate size, which could suggest it was a nesting site. Below a picture of an American Alligator and an American crocodile, simply because they remind me of Kambara and are an example of crocodilians that overlap in range, yet aren't super different like lets say Muggers and Gharials.

Alas Kambara suffers the mekosuchine curse, which is to say even with overwhelming material not much is actually published. Two bonebeds with all sorts of material, yet only 5 papers to its name, generally just accounting for the type description of each species + the humerus paper. A lot of the info presented is actually from L.A. Buchanan's PhD thesis, which did include the description of Kambara taraina. However, since the completion of the thesis in 2008, only the description of the species was actually published. Entire chapters dealing with pathologies, postcrania and potential ecological inferrence are all are only present through the thesis, which has thankfully been uploaded in 2017.

Nevertheless, its a fascinating animal and I hope I made some people curious. Wikipedia page: Kambara - Wikipedia

#croc#crocodile#mekosuchinae#crocodilia#eocene#palaeoblr#prehistory#paleontology#long post#australia#skeletal#pseudosuchia#kambara#kambara implexidens#kambara murgonensis#kambara molnari#kambara taraina

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

#2556 - Nothofagus fusca - Red Beech

AKA Fuscospora fusca, and tawhai raunui.

A medium-sized evergreen tree growing to 35 m tall, usually on lower hills and inland valley floors where soil is fertile and well drained, on North and South Island.

Fossil pollen has been found in Antarctic Eocene strata.

Red beech hybridises with mountain beech (Nothofagus cliffortioides) to form the hybrid species Nothofagus ×blairii, with black beech (Nothofagus solandri) to form the hybrid species Nothofagus ×dubia, and the ruil tree (Nothofagus alessandrii) from Chile to form the hybrid species Nothofagus ×eugenananus.

Grown as an ornamental tree in regions with a mild oceanic climate. The timber is excellent if carefully dried, It was often used in flooring in many parts of New Zealand.

St. Arnaud, Southern Alps, New Zealand

#fuscospora#nothofagus#nothofagaceae#new zealand plant#antarctic beech#red beech#st arnaud#tawhai raunui

1 note

·

View note