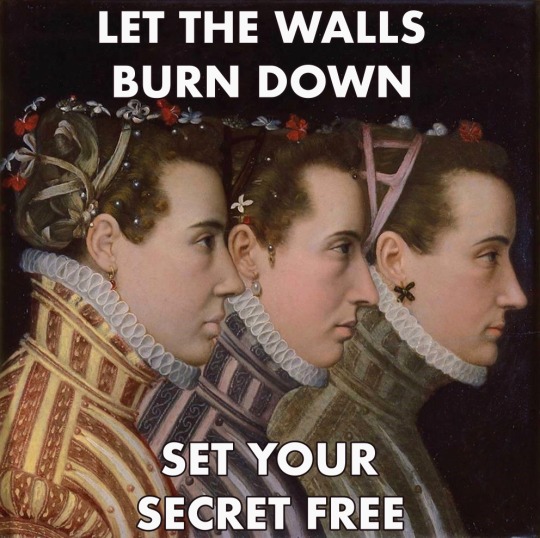

#Lucas de Heere

Text

Lucas de Heere, Wives and daughters. En 1560 ce peintre flamand originaire de Gand visite Londres et y dessine les autochtones qu'il observe dans la rue. Nous aimons particulièrement chez lui cette œuvre qui représente de gauche à droite trois dames de haute lignée et à droite une femme d'extraction plus modeste, épouse d'un commerçant. Cette dernière est plus distinguée, plus pudique, mieux habillée, les traits de son visage sont plus fins que ceux des dames nobles qui ont les yeux globuleux et la tête ronde. La vraie noblesse se cache parfois chez les gens les plus simples, l'élégance aussi. C'est encore le substrat du merveilleux film Gosford Park.

#Lucas de Heere#London#Ghent#Modest clothing#Christian clothing#Noble#Tradition#Europe#European#refined#posh#Aryan#beauty#style#street style

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

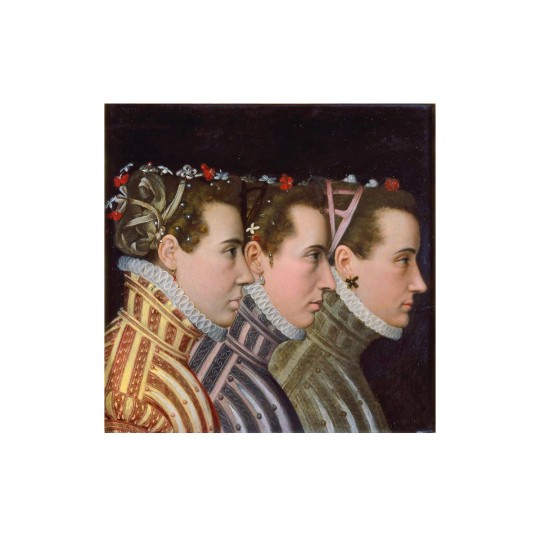

Lucas de Heere (1534-1584)

Triple profile portrait, 1570.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

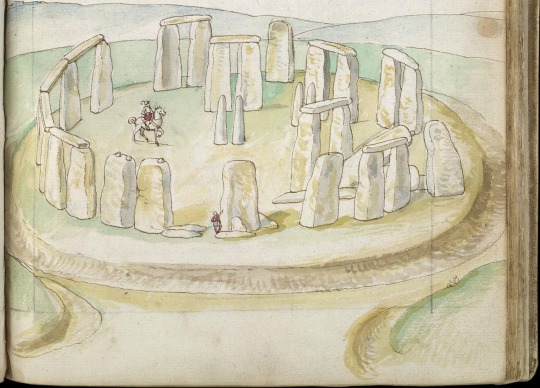

This is the earliest known realistic depiction of Stonehenge. It was painted in watercolour by Flemish artist Lucas de Heere some time between 1573 and 1575.

0 notes

Text

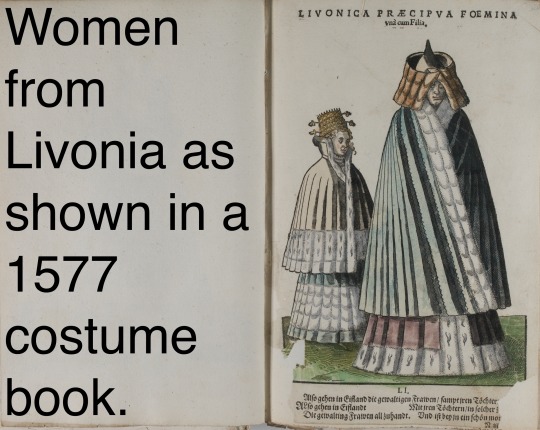

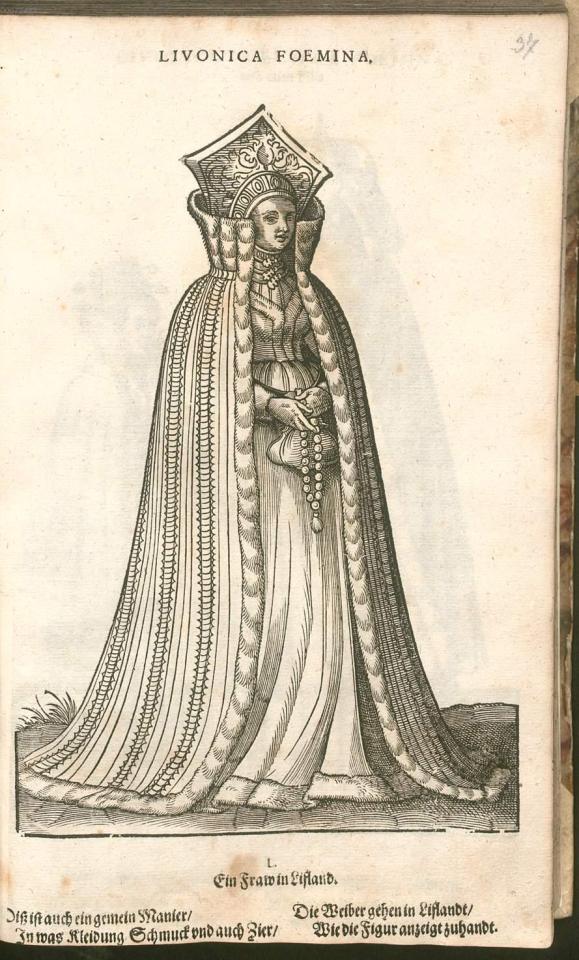

16th c. Costume Books, a Problematic Source for Dress History

But did they really dress like this?

Costume books and costume albums are a popular source for dress historians, historical costumers, and reenactors researching 16th and early 17th c. Europe. There are good reasons for this. They are primary source documents (at least sometimes), and they show the clothing of cultures and social groups that are difficult-to-impossible to find in other types of period art, like the Irish and rural peasants. Examples of these books include Trachtenbuch des Christoph Weiditz, Habiti antichi et moderni di tutto il Mondo di Cesare Vecellio, and Théâtre de tous les peuples et nations de la terre avec leurs habits et ornemens divers. These books are, however, deeply problematic as a dress history source for several reasons. In this post, I will discuss the ways they are problematic and how those of us researching historical dress can gain a better understanding of what the people shown in these books were actually wearing. I have broken down the problems with using these images into 4 areas.

Embodied biases:

The creators of these books were, at least sometimes, prejudiced against the cultures they were portraying, and these biases may have affected how they characterized these cultures. Hans Weigel, author of Habitus praecipuorum populorum, characterized his native German fashion as modest and virtuous and characterized elaborate Italian fashions as decadent and corrupt. Weigel considered these 'strange' foreign fashions a threat to the 'civilized' German fashion he favored (Bond 2018). This bias might have motivated Weigel to idealize his portrayal of German fashion or to exaggerate the strangeness of Italian fashion in order to scare his readers away from trying it.

Weigel's dislike of flashy foreign fashions seems mild in comparison to the bigotry of some of his peers. Flemish artist Lucas de Heere and French artist François Desprez both labeled the Scottish 'savages' in their books. Jost Amman's description of a purported Turkish sex worker in the German edition of Gynaeceum, sive Theatrum mulierum, is appallingly bigoted:

"A Turkish Wh*re: This is a prostitute, who sells her impure body for dirty money to a lover that pleases her. With the earnings of this sin she dresses herself prettily and beautifully, in order to attract the Turks even more easily with her false ornaments." (translation from Ilg 2004)

Considering the blatant bigotry he shows here, I wouldn't anything about trust Amman's depictions of sex workers, Turks, or any other non-Western Europeans. Or any other women, really.

Sights unseen:

Even when costume book creators weren't actively trying to perpetuate their biases through their work, their ignorance could still cause problems. These artists did not always visit the countries whose costumes they painted. They relied on other artists' work or even just verbal descriptions to fill in the gaps in their knowledge. The resulting images can distort the cut, construction, and material of the clothing.

For example, the Turkish women in this original woodcut by Pieter Coecke van Aelst are wearing shawls or scarves with long fringe wrapped around their heads and shoulders. In the Christoph von Sternsee costume album's illustration based off Coecke van Aelst's print, the fringed shawl has become a strange, tailored hood with a panel of pleated cloth attached to either it or the gown below.

(Coecke van Aelst's woodcuts were identified as the source for the von Sternsee album's illustration in Katherine Bond's 2018 dissertation.)

Copy of a copy of what?

In spite of the problems it causes, copying from other artists' work was common in costume albums (Bond 2018). Considering that the artists did not visit all the cultures they illustrated, this is unsurprising. Some images were copied repeatedly, and the artist misunderstanding the source material wasn't the only source of distortion. Artists also made up details to compensate for bare-bones source material.

This simple line black-and-white print of an Irish woman wearing a léine (linen tunic), brat (Irish mantle), and headwear was used by several artists, all of whom made changes and additions. The first copy in this post is the most faithful to the original, but it still adds long sleeves and eyelet holes on the neckline to the léine. The coloring of the headwear suggests a wool hat crested with a tuft of horsehair and having a linen roll at the bottom. The coloring also gives the brat a contrasting lining.

The second knockoff is the most famous. It comes from Lucas De Heere's illustration which purportedly shows Irish people in service to King Henry VIII. This is some thing De Heere couldn't have actually seen, as he moved to England 20 years after Henry VIII died and never went to Ireland at all. De Heere took the most liberties with his version. His Irish woman appears to be topless under her brat. The bottom of her léine has much less volume than the original, and De Heere has added an apron. For the hat, De Heere has replaced the crest with triangles of green wool.

Unlike De Heere's version, the final version is mostly loyal to the cut shown in the original, but it makes some unlikely suggestions for the materials. The léine appears to be green silk brocade. The brat also appears to be silk. Accounts from people who actually went to Ireland in the 16th and early 17th centuries state that these garments were made of linen and wool, respectively. Both the hat and its crest are now completely made of linen.

Chronological distortion:

The heavy use of copying in costume books also has the potential to mislead us in terms of when these fashions were worn, because the original images may be significantly older than publication year of the books that copy them. For example, the dress of Livonian women shown in Hans Weigel's 1577 book was almost certainly copied from Albrecht Dürer's 1521 watercolors. Weigel used references that were more than half a century old, but described them as if they were contemporary fashion in 1577.

Even when costume book images are accurate portrayals of their source material, many of them lack the detail needed to identify seams, fabric types, or garment understructures. How do we deal with these problems when attempting to reconstruct what the people shown in these books actually wore?

What do we do about it?

I am not saying that we should discard these things completely as sources. Dress historians as respected as Patterns of Fashion author Janet Arnold and The Tudor Tailor authors Jane Malcolm and Ninya Mikhaila have used costume book illustrations. I definitely know less about 16th c. dress history than Jane and Ninya. I am just saying we shouldn't use them uncritically.

First, do some research on the costume book you're looking at. When was it created? Do the illustrations look suspiciously similar to those in other books? (Google image search and pinterest can be helpful for identifying this.) Did the creator, like Hans Weigel, have a particular bias they were advancing? Did they actually visit the cultures they portrayed? Christoph Weiditz actually traveled quite a bit, but he did not visit the British Isles, so his Irish and English women are probably based on someone else's art (Bond 2018). A lot of the scholarly publications about costume books are frustratingly paywalled, but some of them can be accessed for free via researchgate or academia.edu.

Avoid using copies when possible, even if the copies are more realistic-looking or more detailed art. As I discussed in the examples above, artists change things when they copy. Publication dates of copies can also be misleading in terms of dating clothing styles.

Find other sources such as: written descriptions from the time period, extant historical garments, more detailed art depicting similar fashions in related cultures, and art made by people from the culture you are studying. Period written descriptions can yield information about materials used, colors, and other details. Extant garments are your best source for information on cut and construction (unless you are lucky enough to have an extant tailor's manual from your period and culture). Detailed art depicting similar fashions can offer suggestions to fill in for missing information on construction, materials, and embellishments. Art created by the culture is valuable for identifying inaccuracies created by bigoted or ignorant artists.

Finally, remember that it's okay to not know everything. There are gaps in our knowledge about what people wore 500 years ago that will probably never be filled without a time machine. Sometimes you just have to make a plausible guess and move on. Don't let yourself get so paralyzed by doing research that you never complete the garment reconstruction/art/tumblr post you were doing the research for.

Bibliography:

Bond, K. L. (2018). Costume Albums in Charles V’s Habsburg Empire (1528-1549). https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.25054

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

Ilg, Ulrike. (2004). The Cultural Significance of Costume Books Sixteenth-Century Europe. In Catherine Richardson (ed.), Clothing Culture, 1350-1650 (p. 29-47). Ashgate.

McClintock, H. F. (1943). Old Irish and Highland Dress. Dundalgan Press, Dundalk.

McClintock, H. F. (1953). Some Hitherto Unpublished Pictures of Sixteenth Century Irish People, and the Costumes Appearing in Them. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 83(2), 150-155. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25510871

Costume Books mentioned:

Amman, Jost. Gynaeceum, sive Theatrum mulierum.

The Costume Album of Christoph von Sternsee. not available on-line. Katherine Bond's research is your best source for this one.

Desprez, François. Recueil de la diversité des habits.

De Heere, Lucas. Corte Beschryvinghe van Engheland, Schotland, ende Irland.

Théâtre de tous les peuples et nations de la terre avec leurs habits et ornemens divers, tant anciens que modernes, diligemment depeints au naturel par Luc Dheere peintre et sculpteur Gantois.

Vecellio, Cesare, and Gratilianus, Sulstatius. Habiti antichi et moderni di tutto il Mondo di Cesare Vecellio.

Trachtenbuch des Christoph Weiditz

Weigel, Hans, and Amman, Jost. Habitus praecipuorum populorum, tam virorum quam foeminarum singulari arte depicti.

Kostüme der Männer und Frauen in Augsburg und Nürnberg, Deutschland, Europa, Orient und Afrika

Kostüme und Sittenbilder des 16. Jahrhunderts aus West- und Osteuropa, Orient, der Neuen Welt und Afrika

costume prints by an unknown artist, in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Cabinet des Estampes. I cannot find this one online. image taken from McClintock 1953.

#dress history#historical fashion#art#16th century#17th century#historical costuming#historical dress#cw whorephobia#cw racism#irish dress#leine#irish mantle#reenactment#costume album

194 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good Omens fans…

Caption this!

(Our ineffable husbands spotted in the wild?! Check out the snake tattoos, and the blue tattoos plus sword combo! ❤️ …Plus, epic matching mullets and moustaches 😄)

My caption offering…

Flashback to England, circa 1573, returning from a lovely walk in the countryside:

“Honestly, Crowley, this is the *last* time I let you convince me to try out ‘the latest fashions’ for clothing, or, should I say, lack thereof. Oh, dear Lord, is that chap over there *drawing us??* ”

“Don’t worry, Angel, I’ll *shield* your honour, geddit?” (Raises a rudimentary shield, his eyebrows, and a cheeky grin) “And relaaax, it’s not as if some random bloke’s doodle is gonna end up *miraculously preserved* and on display to the masses!”

📌 Images taken in The British Library’s “Treasures” collection (which is beautiful, highly recommend a visit for anyone in reach of London)

📷 Illustration by Flemish artist Lucas De Heere (with The British Library’s official caption included!)

#good omens#is this good omens? yes#good omens fandom#aziraphale#crowley#ineffable husbands#out for a walk#caption this#potential flashback scene#british library#neil gaiman#michael sheen#david tennant#good omens 3#flashback scenes we’d like to see#guy with a snake tattoo#angelic mullet#tasteful nude#museum lovers

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Detail of Queen Mary I from Allegory of the Tudor Succession (1570s) by Lucas de Heere

#mary i#queen mary#mary i of england#mary tudor#art#art history#history of art#tudor history#henry viii#the tudors#english history#tudor era#tudor england#tudor period#house of tudor#tudor dynasty#tudor#tudors#british history#english monarchy#elizabethan england#elizabethan#elizabethan era#16th century art#16th century#sixteenth century#1500s#renaissance art#renaissance#renaissance history

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elephant, circa 1576

detail: Francis, Duke of Anjou, Margaret of Valois, Henry II, Duke of Lorraine

Quintain, circa 1576, Henry III in the foreground

Polish Ambassadors, circa 1576

Tournament, circa 1576

Barriers, circa 1576

Journey, circa 1576

Fontainebleau, circa 1580, Henry III and Queen Louise of Lorraine in the foreground

Water Festival at Bayonne, circa 1580-81, depicts festivities at the summit meeting between the French and Spanish courts at Bayonne in 1565

The Valois Tapestries

“The series is composed of eight tapestries, woven with wool, silk, silver and gilt metal-wrapped thread, commissioned around 1575 by Catherine de’ Medici to an unidentified Brussels atelier, based on cartoons by Lucas de Heere from drawings by court painter Antoine Caron.” (x)

The tapestries are in the Uffizi Museum in Florence (x)

#history#history of france#catherine de' medici#the valois dynasty#henry iii of france#art#tapestries

30 notes

·

View notes

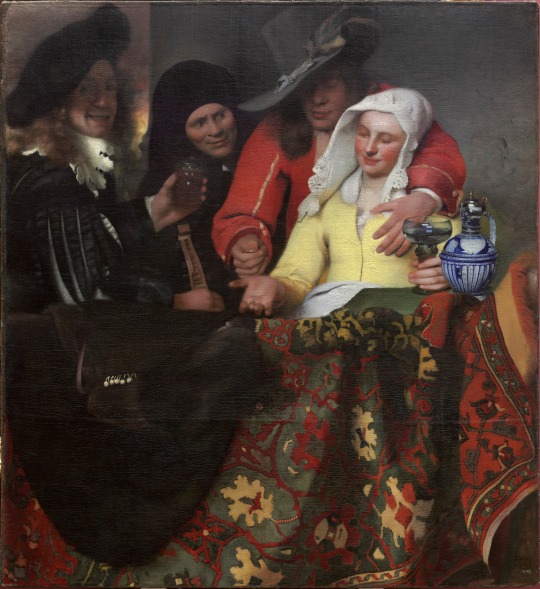

Photo

Wat? Gezicht op Delft (1660-1661), Gezicht op huizen in Delft, bekend als Het straatje (1658-1659), Sint Praxedis (1655), Christus in het huis van Maria en Martha (1654-1655) en De koppelaarster(1656) door Johannes Vermeer

Waar? Tentoonstelling Vermeer in het Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Wanneer? 10 februari 2023

Maar liefst vierhonderdzestigduizend bezoekers kwamen in 1996 naar het Haagse Mauritshuis voor een tentoonstelling met tweeëntwintig werken van Johannes Vermeer. Ik was op 19 april van dat jaar één van de vele bezoekers die hun entree maakten in een speciaal voor de gelegenheid over de Hofvijver gebouwde tent. De Volkskrant (9 november 1995) opende een artikel over deze expositie met de zin: “Volgens kenners is het een gebeurtenis van eens in de paar honderd jaar.” En daarmee is maar weer eens aangetoond dat kenners er soms verschrikkelijk naast kunnen zitten. We zijn inmiddels ‘slechts’ zevenentwintig jaar verder en in het Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam start opnieuw een tentoonstelling met uitsluitend werk van Vermeer. Dit keer zijn er maar liefst achtentwintig werken te zien. Daaronder bevindt zich een drietal werken uit de New Yorkse Frick Collectie die normaal nooit worden uitgeleend. Een grootscheepse verbouwing van dit museum zorgt voor de unieke uitzondering op de regel. De verbouwing was voor Rijksmuseum-directeur Taco Dibbits aanleiding om te proberen zoveel mogelijk werken van de zeventiende-eeuwse meester bij elkaar te brengen in Amsterdam. En dat is gelukt!

Als ik de expositie binnenkom, tref ik in de eerste zaal gelijk twee bekende werken aan: Gezicht op Delft uit het Mauritshuis en Het straatje uit het Rijksmuseum. We beginnen onze tocht langs het werk van Vermeer in zijn thuisstad Delft. Hoewel ik vaak in zowel het Rijksmuseum als in het Mauritshuis kom en beide werken goed ken, zorgt het feit dat ze in een andere context hangen ervoor dat ik met nieuwe ogen naar de werken ga kijken. Over Het straatje schreef ik eerder in dit dagboek: “In mijn jeugd was kunst niet alom aanwezig. Al mijn kunstervaringen dateren dan ook van mijn studententijd en daarna. Allemaal, behalve één. Ooit hadden we bij ons thuis een kunstkalender. Waarschijnlijk hadden we die als presentje voor Nieuwjaar gekregen van een verzekeringsmaatschappij of zo. Nu zouden we zoiets een ‘premium’ noemen, maar die term was toen (goddank!) nog niet uitgevonden. Enfin, hoe de kalender in ons huis terecht kwam doet voor dit verhaal ook niet echt ter zake. Wél het feit dat één van de reproducties grote indruk op mij maakte. Zo sterk zelfs dat ik nu, pakweg vijftig jaar na dato, nog steeds weet welk schilderij op de kalender was afgebeeld.” Wat bij zowel Het straatje als bij Gezicht op Delft onmiddellijk in het oog valt is de geweldige manier waarop Vermeer licht weergeeft.

Johannes Vermeer werd in 1632 geboren in Delft, waar hij in 1675 overleed. Hij was 21 jaar oud toen hij trouwde met Catharina Bolnes, met wie hij veertien of vijftien kinderen kreeg, van wie er bij zijn overlijden nog elf in leven waren. Aanvankelijk was Vermeer gereformeerd, maar bij zijn huwelijk trad hij toe tot de katholieke kerk. Behalve schilder was hij ook kunsthandelaar en voorman van het Lucasgilde.

Na zijn huwelijk schilderde Vermeer een aantal grote werken met historische verhalen. Het werk dat mij het minst aan Vermeer doet denken is Sint Praxedis. Praxedis was een Romeinse adellijke dame die in de tweede eeuw lichamen van christelijke martelaren verzorgde. Vermeer schilderde dit werk naar voorbeeld van een Florentijnse schilder

Christus in het huis van Maria en Martha is al veel meer een ‘echte’ Vermeer. Het schilderij is gebaseerd op een verhaal uit het Evangelie van Lucas: “Toen ze verder trokken ging Hij een dorp in, waar Hij gastvrij werd ontvangen door een vrouw die Marta heette. Haar zus, Maria, ging aan de voeten van de Heer zitten en luisterde naar zijn woorden. Maar Marta werd helemaal in beslag genomen door de zorg voor haar gasten. Ze ging naar Jezus toe en zei: ‘Heer, kan het U niet schelen dat mijn zus mij al het werk laat doen? Zeg tegen haar dat zij mij moet helpen. De Heer zei tegen haar: ‘Marta, Marta, je bent zo bezorgd en je maakt je druk over zoveel dingen. Er is maar één ding noodzakelijk. Maria heeft het juiste gekozen, en dat zal haar niet worden ontnomen” (Lucas 10:38-02 NBV21). Je ziet aan Vermeers Martha dat ze het eigenlijk te druk heeft om zich ook nog eens druk te moeten maken over de luiheid van haar zuster. Een beetje gehaast zet ze een mand met brood op tafel, terwijl ze Jezus vraagt Maria een standje te geven. Jezus straalt volkomen rust uit. Terwijl hij reageert op Martha’s klacht, wijst hij op Maria die stil luisterend aan zijn voeten zit. De drie protagonisten van het verhaal staan centraal. Bijfiguren ontbreken en ook is er nauwelijks iets van de omgeving te zien. Vermeer richt zich volledig op de kern van het verhaal. De verstilling die de latere werken van de schilder zal kenmerken, is ook hier al volop aanwezig.

Een omslagpunt in het werk van Vermeer is De koppelaarster. Religie en mythologie maken plaats voor een bordeelscène. Daarna zal Vermeer zich vooral richten op verstilde huiselijke taferelen en tronies van vrouwen.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Triple Profile Portrait by Lucas de Heere // “Talk To Me” by Stevie Nicks

#fly art#stevie nicks#chas sandford#talk to me#rock a little#1985#please don't remove caption#she pays this song dust bc she didn't write it but it's so good......

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medelijden

Toen leverde hij Hem dan aan hen over om gekruisigd te worden. En zij namen Jezus mee en leidden Hem weg. Johannes 19:16

Terwijl Christus door de straten trok, keek een grote menigte toe. In de menigte bevond zich een klein aantal teerhartige vrouwen, waarschijnlijk zij die genezen waren of wier kinderen door Hem gezegend waren. Zij slaakten een zeer luide en bittere kreet, zoals Rachel die weende om haar kinderen, en weigerde getroost te worden omdat zij er niet meer waren. (Jeremia 31:15). De stem van medelijden won het van de stem van verachting. Maar Jezus stond stil en zei: 'Dochters van Jeruzalem, huil niet over Mij, maar huil over uzelf en over uw kinderen' (Lucas 23:28b). Het verdriet van deze goede vrouwen was een zeer gepast verdriet; Jezus verbood het hen op geen enkele manier, Hij raadde hen alleen een ander verdriet aan dat beter zou zijn. De meest Bijbelse manier om het lijden van Christus te beschrijven is niet door te proberen medelijden op te wekken door middel van kleurrijke beschrijvingen van Zijn bloed en wonden. Welke droefheid, beste vrienden, moet dan worden opgewekt door een blik op het lijden van Christus? Het is dit - huil niet omdat de Heiland bloedde, maar omdat jouw zonden Hem lieten bloeden.

"'Het waren mijn zonden, mijn wrede zonden,

Zij verergerden Zijn pijnen meer en meer;

Elk van mijn misdaden werd een nagel,

Mijn ongeloof een speer."

Als een mens zijn overtredingen belijdt en zich met tranen op zijn knieën voor God vernedert, dan weet ik zeker dat de Heer de tranen van berouw veel meer waardeert dan de tranen van medelijden. "Huil liever om jezelf," zegt Christus, "dan om Mij." Als we naar het lijden van Jezus kijken, zien we tranen van berouw. Bedenk, beste vrienden, dat als deze onbekeerde mensen hun vertrouwen niet op Christus stellen, zij zelf moeten lijden voor wat Christus voor ons heeft geleden. Het verdriet dat het hart van de Heiland brak, zal hun harten verpletteren. Of Christus sterft voor mij, of ik sterf de tweede dood voor mijzelf; als Hij de vloek niet voor mij heeft gedragen, zal die voor eeuwig en altijd op mij blijven rusten. Bedenk, beste vrienden, dat er mensen in deze gemeente zijn die nog geen deel hebben gehad aan het bloed van Jezus. Er zitten sommigen naast jullie die, als de dood hun ogen nu zou sluiten, deze in de hel weer zullen openen! Denk daaraan! Huil niet om Hem, maar om hen. Misschien zijn het je kinderen, je geliefden, die geen interesse in Christus hebben; ze zijn zonder God en zonder hoop in de wereld! Bewaar je tranen voor hen; Christus verlangt geen medelijden voor Zichzelf.

Denk eens aan de miljoenen mensen in deze donkere wereld! Er is berekend dat elke keer dat de klok tikt, één ziel van de tijd naar de eeuwigheid gaat! De mensheid is nu zo talrijk geworden dat er elke seconde een dode valt; wat een afschuwelijke gedachte om te weten hoe weinigen van het menselijk ras Christus hebben aangenomen. 'Want er is onder de hemel geen andere Naam onder de mensen gegeven waardoor wij zalig moeten worden' (Handelingen 4:12b). Oh, wat een akelige gedachte! Hoeveel onsterfelijke zielen dalen elk uur af naar de diepten van de hel. Daarom zegt de Meester: "Huil toch niet om Mij, maar huil om jezelf." Als er geen sympathie is voor de mensen die zielen willen winnen voor Christus, dan is er ook geen sprake van oprechte sympathie voor Christus. Je kunt onder een preek zitten en veel voelen, maar je gevoel is waardeloos als het je niet in tranen brengt voor jezelf en voor je kinderen. Hoe is het met jou gesteld? Heb je berouw gehad over je zonden? Heb je gebeden voor je medemensen? Zo niet, laat dan de gedachte aan Christus die op straat bezweek je aansporen om dat vandaag wel te doen.

Vertaald uit: Het kruis, 40 overdenkingen over de kruisiging van Christus. Door Charles Haddon Spurgeon.

0 notes

Text

Homilie voor de Kerstvieringen in WCZ Ter Vest Balen (27 december 2023) en WCZ De Berk Meerhout (29 december 2023)

lezingen:Ter Vest: 1 Johannes 1,1-4 Lucas 2,1-14De Berk: 1 Johannes 2,3-11 Lucas 2,1-14

Ik verkondig u een vreugdevolle boodschap die bestemd is voor heel het volk. Heden is u een Redder geboren, Christus de Heer, in de stad van David.

Broeders en zusters, de woorden van de engel aan de herders, zijn naar diens eigen zeggen een boodschap voor heel het volk. We zouden kunnen…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Lucas de Heere, Wives and daughters (détail), 1568.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Acuarela titulada ‘Irlandeses equipados para el servicio del último rey Enrique’ (c. 1575), obra de Lucas de Heere.

0 notes

Text

Triple portrait of minions of Henri III by Lucas de Heere (circa 1570).

1 note

·

View note

Text

Patterning a 16th c. Irish léine sleeve

Mid-16th c. images of the léine from "Drawn after the Quick" and Codice de Trajes

The léine of 16th century Ireland had huge, iconic sleeves. Sadly, we have neither surviving examples of this garment, nor detailed period documentation, so we don't know how these sleeves were made. I have seen a couple different sewing patterns purposed, but none of these match the voluminous, gathered sleeves shown in the Codice de Trajes and the costume album of Christoph von Sternsee. This is my attempt to create a sleeve pattern that better matches the surviving evidence.

The cut of léine sleeves probably varied across 16th c. Ireland, potentially impacted by factors like a person's wealth or where in Ireland they lived. It almost certainly changed over time as more of Ireland fell to English colonial conquest. The wearing of the large-sleeved léine was banned by King Henry VIII (McClintock 1943). Lucas de Heere’s circa 1575 illustrations show women with much smaller sleeves than earlier images. However, at least during the early part of the century, sleeves did not vary by gender. According to Laurent Vital, the only difference between a man's léine and a woman's léine was that the woman's had gores in the bottom it make it fuller (Vital 1518).

My goal with this project is to create a léine sleeve pattern for an early to mid-16th c. Irish person living outside of the Pale. Since none of the period images or texts are very detailed, I am combining information from several sources.

Englishman Edmund Campion who visited Ireland in 1569 gave the following derisive description of the léine: “Linnen shirts the rich doe weare for wantonnes and bravery, with wide hanging sleeves playted, thirtie yards are little enough for one of them” (Campion 1571).

Campion’s claim that the sleeves were pleated initially struck me as strange. English and continental European shirts from this period frequently had gathered sleeves (Mikhaila and Malcolm-Davies 2006, Arnold, Tiramani and Levey 2008), but pleating isn’t the same thing as gathering. However, other period writers made similar claims. Writing in 1596, Edmund Spenser mentioned "thicke foulded lynnen shirtes” as a garment worn by the Irish (Spencer 1633).

Similarly, Fynes Moryson described the léine as being made of “thirty or forty ells [of linen] in a shirt all gathered and wrinkled,” elsewhere he described it as “folded in wrinckles” (Moryson 1617).

In The Image of Irelande, John Derricke gave the following description of the léine:

Their shirtes be verie straunge,/ not reachyng paste the thie:/ With pleates on pleates thei pleated are,/ as thicke as pleates maie lye./ Whose sleves hang trailing doune/ almoste unto the Shoe (Derricke 1581)

Assuming that Derricke’s description is not just poetic license, I know of one 16th century construction method that matches the description “pleats on pleats [. . .] as thick as pleats may lie,” and that is cartridge pleating. Cartridge pleating is a technique that is more commonly used on thick fabrics like woolens, because a lot of fabric bulk is needed to keep the pleats standing properly, but extant 16th and early 17th c. neck ruffs use cartridge pleating to join massive lengths of fine linen to a neck band (Arnold, Tiramani and Levey 2008).

Cartridge pleating on a thick woolen fabric

A person unfamiliar with sewing methods and terms might well describe cartridge pleating as looking like folds, gathers, or wrinkles.

The léine sleeve patterns commonly used in modern reconstructions are completely flat, like a Japanese kimono sleeve with rounded corners. (There’s also a version which has a drawstring or gathering running along the top of the sleeve. This is a 20th c. Ren Fair invention which has no historical basis.)

The end-on views of the sleeve openings in the recently-discovered images from Codice de Trajes and the costume album of Christoph von Sternsee clearly show that this is not correct. The rounded shape they show for the sleeve end can only be achieved through gathering.

Archer from the von Sternsee costume album and the O’Brien messenger from The Image of Irelande

The best illustration of a léine in The Image of Irelande, the messenger on plate 7, also provides evidence for a gathered sleeve. The way the fabric drapes in the middle of the sleeve suggests that the sleeve is gathered at both ends. Furthermore, the way the mass of a léine sleeve centers under the wearer’s arm when the wearer holds their arm out straight, like the O’Brien messenger, but hangs down like a trumpet when the wearer lowers their arm, like on von Sternsee’s archer also suggests that the sleeve is a symmetrical shape that is gathered at both ends and not a trumpet shape that is only gathered at the wrist end.

With these elements in mind, I went looking for a pattern which would create the correct shape. I used Jean Hunnisett's 15th c. bagpipe sleeve pattern from Period Costume for Stage and Screen and the sleeve pattern from this 1630s English waistcoat (published in Seventeenth-Century Women’s Dress Patterns) as a starting point.

1630s waistcoat sleeve pattern

I replaced the curved sleeve heads in these patterns with the straight sleeve end and square underarm gusset typical of mid-16th-18th c. shirts, since the léine, like the shirt, is an unfitted linen garment, and because the straight edge is much easier to gather all the way around. I don't have any actual evidence for square gussets in 16th c. Ireland, but this pattern definitely needs an ungathered piece at the underarm. Anyone who is bothered by the lack of evidence can use a triangular gusset like the one on the 15th c. Moy gown instead.

After that, I experimented with mock-ups until I figured out how to get the correct proportions. I don't have any training in patterning or draping, so this took several tries. I used my 1/3 scale ball-jointed doll (24 inches tall) as model, because he required a lot less fabric and sewing. Since this was just a mock-up, I used random linen remnants from my stash, and I didn't bother to finish most of the edges.

Here is the final sleeve with the seams sewn together, but before doing the gathering:

This sleeve, on his right arm, is based on the gathered-wrist cuff version of the léine from Codice de Trajes, the von Sternsee album, and The Image of Irelande.

This sleeve ended up with me having to gather 31 inches of fabric into a 5-inch armscye. So yeah, cartridge pleating became necessary, because there is no way to make that kind of reduction work with regular gathering. I also had to do some smocking to get the giant mass of fabric better controlled before I could attach it to the body of the léine.

While this pattern might seem absurd, (it does call for a sleeve end wider than the wear is tall to be pleated into the armscye,) a close examination of John Michael Wright's 1680 portrait of Sir Neil O'Neill shows remarkably similar sleeves.

While this painting is from a century later than my target time period and the clothing clearly shows changes like the addition of English-style shirt sleeve ruffles, the shirt still has elements which I have seen no where else in late 17th c. fashion that are probably derived from earlier Irish dress.

The doublet worn over top prevents it from hanging down properly, but this shirt sleeve has the same bagpipe shape as the 16th c. léine. I have highlighted it in magenta to make this easier to see. The fine, regular folds near the top of the sleeve (highlighted in yellow) are probably the result of smocking or cartridge pleating, indicating that this sleeve, like my purposed pattern, has a large amount of fabric gathered or pleated to the armscye. The wrist end of the sleeve has 3 rows of smocking stitches sewn with silk thread, which shows that the sleeve cuff has a huge amount of fabric gathered into it.

Historically, silk was the thread of choice for smocking, because it is smoother and has greater tensile strength than wool, linen, or cotton. Several 16th c. sources note that the Irish used silk thread when making their léinte (Gresh 2021). Laurent Vital described Irish women as wearing, "chemises with wide sleeves, worked around the collar and in the seams with silk needlework of different colours" (1518). The presence of smocking on O'Neill's shirt combined with my experience trying to recreate this sleeve makes me think that at least some of that 16th c. silk needlework was smocking.

For the left sleeve of my mock-up, I tried to recreate the flatter sleeves from "Drawn After the Quicke". These sleeves do not have a gathered wristband.

This sleeve used basically the same pattern, but the lack of gathering at the wrist opening meant that the whole sleeve was slightly smaller, so I only had to pleat 26 in of fabric into the armscye instead of 31 in. This was just enough of a difference that I could set the sleeve without smocking it first, unlike the right sleeve. I guess this is the more budget-friendly option for your less wealthy kern.

I also made the curve at the bottom of the sleeve wider to give this one a more square shape.

Some of my failed experiments:

I would like to thank my friend Nikki for loaning me her smocking machine. This project would have been a much bigger pain if I had to do all those gathering stitches by hand.

Since this post has gotten rather long, I am putting the actual drafting instruction for this sleeve pattern in a separate post.

If anyone would like to support my work financially, I now have a ko-fi page.

Bibliography:

Arnold, Janet, Tiramani, J., & Levey, S. (2008). Patterns of Fashion 4. Macmillan, London.

Campion, Edmund. (1571). A Historie of Ireland, Written in the Yeare 1571. Dublin. https://archive.org/details/historieofirelan00campuoft/historieofirelan00campuoft/page/n5/mode/2up

Derricke, John. (1581). The Image of Irelande, with the discoverie of a Woodkarne. John Daie, London. https://archive.org/details/imageofirelandew00derr/page/n29/mode/2up?view=theater

Hunnisett, Jean. (1996). Period Costume for Stage & Screen: Patterns for Women's Dress, Medieval-1500. Players Press, Inc, Studio City.

Gresh, Robert. (2021). The Saffron Shirt, Part 1: Saffron and Silk, Urine and Grease. Wilde Irish. https://www.wildeirishe.com/post/the-saffron-shirt-part-1-saffron-and-silk-urine-and-grease

McClintock, H. F. (1943). Old Irish and Highland Dress. Dundalgan Press, Dundalk.

McGann, K. (2008). The Invention of Drawstrings and Pleated Sleeves. Reconstructing History. https://reconstructinghistory.com/blogs/irish/the-invention-of-drawstrings-and-pleated-sleeves-1

Mikhaila, Ninya, & Malcolm-Davies, Jane (2006). The Tudor Tailor. Quite Specific Media Group, Ltd, London.

Moryson, Fynes. (1617). An Itinerary Containing His Ten Yeeres Travell through the Twelve Dominions of Germany, Bohmerland, Sweitzerland, Netherland, Denmarke, Poland, Italy, Turky, France, England, Scotland & Ireland. volume 4. https://ia801307.us.archive.org/16/items/fynesmorysons04moryuoft/fynesmorysons04moryuoft.pdf

North, Susan and Jenny Tiramani, eds. (2011). Seventeenth-Century Women’s Dress Patterns, vol.1, V&A Publishing, London.

Spencer, Edmund. (1633). A View of the present State of Ireland. https://celt.ucc.ie/published/E500000-001/index.html

Vital, Laurent (1518). Archduke Ferdinand's visit to Kinsale in Ireland, an extract from Le Premier Voyage de Charles-Quint en Espagne, de 1517 à 1518. translated by Dorothy Convery. https://irish-dress-history.tumblr.com/post/721163132699131904/laurent-vitals-1518-description-of-ireland

#16th century#irish dress#dress history#leine#art#gaelic ireland#irish history#historical men's fashion#historical dress#historical women's fashion#sewing

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hij kwam op aarde voor ons allemaal

Enkele gedachten over Lucas 2:1-20

Kerst is bij uitstek een feest van licht en gezelligheid. We zoeken elkaar op, we zitten rond de kerstboom, we eten en drinken lekker. We genieten van het feest.

Maar we weten ook dat het lang niet altijd gezellig is in de wereld. We horen van oorlog en geweld, uitbuiting en discriminatie. We accepteren de ander niet altijd zoals hij of zij is. We staan gauw klaar met ons oordeel. We zetten de ander in de hoek.

Is het in onze tijd erger dan vroeger? Waren de mensen vroeger beter? Ik denk van niet. In feite is de mens al die eeuwen door niet veranderd. Wel zijn de omstandigheden waarin we leven veranderd.

In Jezus’ tijd heerste het Romeinse rijk rond de Middellandse Zee. De Romeinse keizers waren oppermachtig en ze heersten over de toenmalige wereld door hun legioenen. Ze legden andere volken hun wil op.

Er bestond in die tijd ook slavernij. Meesters waren in het bezit van slaven. Die werden verhandeld op slavenmarkten. Slaven moesten doen wat hun heer zei. Ze hadden geen rechten, alleen plichten.

In de tijd dat Jezus geboren werd in Israël voelden sommigen zich beter dan de ander. De Farizeeën en Sadduceeën, de godsdienstige leiders, zagen neer op het volk dat de wet niet kende.

Onder aan de maatschappelijke ladder stonden ook de herders. Ze hoedden de schapen van anderen. Het waren ruwe, onbehouwen kerels. Vaak nemen ze een loopje met de waarheid, vond men. Hun woord was voor de rechtbank niet geldig. Ze mochten niet getuigen.

Iets daarvan lezen we in Lucas 2. We lezen van de Romeinse keizer die het volk zijn wil oplegde. Zo schreef hij een volkstelling uit. Hij wilde de belastingheffing verbeteren. Daarom moest iedereen zich laten inschrijven in de plaats waar zijn familie vandaan kwam. Zo moesten ook Jozef en Maria zich laten inschrijven in Bethlehem. Ze stamden namelijk af van David, en u weet: die kwam uit Bethlehem.

Zo gaan ze op weg voor een moeilijke en lange reis. Maria is in verwachting en haar kindje kan elk moment komen. Als ze in Bethlehem aankomen is er geen plaats voor hen in de herberg. We weten niet waarom er geen plaats was. Misschien was het druk. Maar het is tekenend. Vaak sluiten we de ander uit. Er is voor hem of haar geen plaats in ons midden.

Als Jozef en Maria in Bethlehem zijn, wordt hun kindje geboren, waarschijnlijk in een stal, want Maria moet haar kindje leggen in een voederbak voor dieren. Onopgemerkt door de wereld wordt hun kindje geboren. De wereld weet niet dat dit een bijzonder kind is. Het is de lang beloofde Messias die vrede zou brengen tussen God en mensen en vrede op aarde.

Hoe zal de wereld dit ooit te weten komen? Hoe zal God zijn boodschap van vrede en heil aan de wereld bekend maken? Zal Hij die bekendmaken via keizers en koningen, via Farizeeën en Sadduceeën, via rijken en hooggeplaatsten? Nee, Hij maakt zijn boodschap bekend via herders.

Als de herders op de velden van Bethlehem hun schapen hoeden, verschijnt er een engel. Hij heeft namens God een geweldige boodschap voor de herders, ja, voor de wereld. We lezen die boodschap in de tekst van vanmorgen: “Vandaag is in de stad van David voor jullie een redder geboren. Hij is de Messias, de Heer”. Uitgerekend aan herders, die door iedereen veracht en genegeerd werden, verkondigt de engel zijn blijde boodschap. Hi zegt: ”Voor jullie is een redder geboren”.

Wat betekent dit? Dit betekent dat de herders niet uitgesloten worden, maar ingesloten worden door God. Dat betekent dat armen, onaanzienlijken, verachten door God niet uitgesloten worden, maar ingesloten. De Messias, Jezus, kwam voor ons allemaal. God zondert niemand uit. Hij wil iedereen bereiken met zijn blijde boodschap, met vrede, verzoening en heil.

Ook al zijn we zondige mensen, Hij sluit ons niet uit, maar in. Hij heeft ons allemaal op het oog. Voor iedereen is de Redder geboren. Voor iedereen zou Jezus sterven aan het kruis. God wil vrede met iedereen. Ja, God accepteert ons zoals we zijn. Niet dat Hij onze zonden accepteert, maar wel ons als mensen.

Als God ons accepteert zoals we zijn, waarom accepteren wij elkaar niet?

De boodschap van kerst is: Vrede op aarde voor alle mensen. Daar is God op uit. Geven wij die vrede door aan elkaar? Accepteren wij elkaar?

Alanya, 25 december 2022

0 notes