#Manual Dyer

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

And then alternatively "it was just a phase, I talked to my father about another option" "car is waiting for me" my nepo baby🥺

Oh wait, is dyehard an anti-capitalist anarchist queer/overprivileged nepo baby trying to prove themselves. I'm dying.

Gwen said "Im gonna shoot the pilot of this crashing plane, clearly I deserve to be the pilot instead. No , I don't know how to fly a plane, why do you ask?"

#is there a manual somehwere?#tmagp#the magnus protocol#gwendolyn bouchard#what if#tmagp spoilers#alice dyer#dyehard

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

7 hours and 18 minutes on this fucking thing, all for Jonny Sims and Alex J Newall’s bastard child of a podcast (affectionate)

Close ups under the cut! DON’T READ CAPTIONS IF YOU DON’T WANT MAGNUS PROTOCOL SPOILERS!!!!!!!!!!

In my head this piece is a bunch of burner phones and devices that Alice has from Colin after he goes kayaking and some other bits and bobs that she already had!

Camera with a picture i stole from a BBC article which is meant to be a picture from the Institute ruins that RedCanary took in ep 1! And some Colin discard commands lol

The phone with the picture is a photo i stole from an ebay listing of a replica of the Hellraiser puzzle box and just distorted the fuck out of lmao. It’s meant to be the weird box that RedCanary takes from the Institute ruins! The Nokia has a bit of the resignation email from the woman who worked at The Hilltop Centre and the white phone has forum posts from ep 1 as well!

Thumbtacks and thread from the Conspiracy Cork Board that Alice has in my head (i’m so happy with those thumbtacks) and the phone i think Colin would’ve had after going all “technology is evil” with a message from Alice. I think Alice would’ve kept it.

Phone with a distorted pic of Bonzo, straight from the RQ website, again i just fucked around with the filters until it looked weird. Also an allen wrench (hex key) and some wired headphones cause i think Alice is a wired headphones girlie.

Ipod with the first song on the official Alice Dyer playlist and a floppy disc with “FR3-d1” written on it! Sam mentions the OIAR computers having floppy drives so it felt fitting! It could be info about how Freddy is evil, it could be an instruction manual for it, i’m not sure yet!

#tma#the magnus archives#the magnus protocol#tmagp spoilers#tmagp fanart#tma fanart#fanart#artists on tumblr#tma spoilers#tma podcast

255 notes

·

View notes

Text

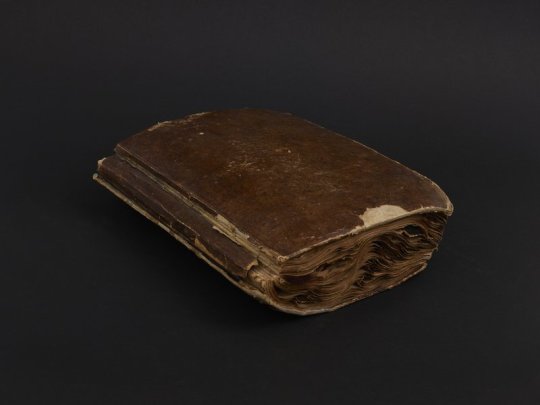

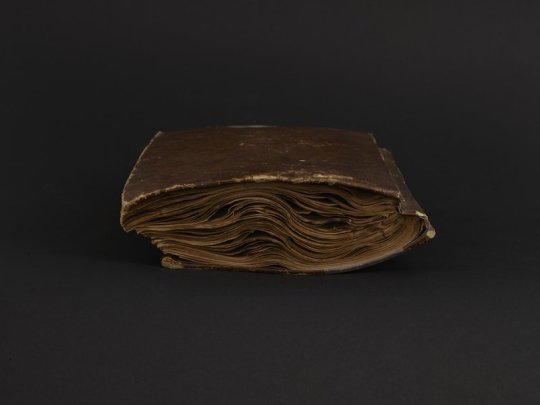

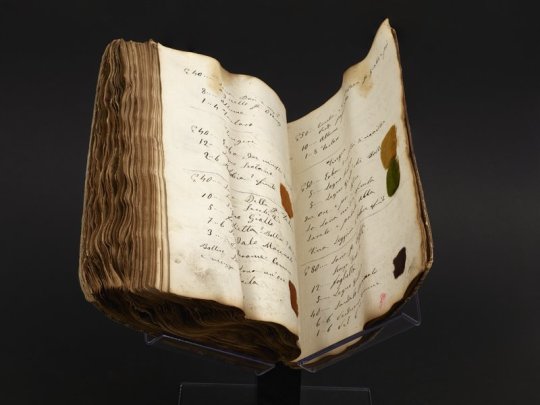

Italian Dyer's Notebook

Autograph manuscript, circa 1856-1866

This warped and worn nineteenth-century Italian manuscript appears to be a working manual and color inventory of a wool dyer in mid-nineteenth-century Italy. The handwritten entries are dated between 1856 and 1866, suggesting that the notebook was used and added to over a period of time. The work includes more than 500 numbered and itemized recipes for dyes. Recipes are illustrated with more than 800 wool and fabric samples adhered to the pages. The samples range in colors from shades of brown to vivid fuchsia, turquoise, and mustard. The samples include fabrics of wool, felt, and cotton, as well as raw wool and coils of yarn. Ingredients listed include mud, urine, arsenic, and vitriol. Pages 192-219 contain longer descriptions of dying processes, one attributed to Giacomo Udinese and another to Cesare Bizzi.

Check it out on our digital collections site.

#colors#colors in textiles#colorfastness#dyes#dyes and dyeing#textiles#wool#italian manuscripts#manuscripts#rare books#old books#rare book#dye samples#19th century#othmeralia

541 notes

·

View notes

Text

Noble girls received confusingly mixed messages about the clothing they should choose. The clearest Biblical guidance came from the author of 1 Timothy who had advised that ‘women should dress themselves modestly and decently in suitable clothing, not with their hair braided, or with gold, pearls or expensive clothes, but with good works’. This provided justification for generations of Christian authors who associated fine clothing with sinfulness. Jean de Meun, whose Roman de la Rose was to be found in many fifteenth-century noble houses, asserted that ‘a woman who wants to be beautiful . . . wants to wage war on Chastity’. Yet devotional books routinely indicated the high status of virgin martyrs and the Virgin Mary herself by depicting them in opulent and elegant garments, like the cloth of gold dress that St Cecilia wore over her hair shirt. The upper classes believed that ‘in a well-ordered society, consumption patterns would reflect the hierarchy of status’. In 1363 parliament had even introduced sumptuary laws outlining the types of clothing permissible to those of various stations. Gentlemen whose lands were worth less than £ 100 annually were forbidden to wear silk, embroidered clothing, gold jewellery ‘or any manner of fur’, and their wives and children likewise. Knights whose land was valued at less than 200 marks annually were forbidden to wear the most expensive wools and furs or cloth of gold, and even those receiving £ 1,000 a year could only wear ermine or cloth embroidered with jewels in their headwear. Although the legislation was repealed just over a year later, as Christopher Dyer has argued, it indicates the legislators’ ‘assumption that the higher aristocracy ought to wear’ opulent apparel that distinguished them from their inferiors.

One author who tried to steer a helpful middle course was Christine de Pisan, the daughter of an Italian physician and widow of one of the secretaries of Charles V of France...In her manual, Le Trésor de la Cité des Dames, Christine advised ‘the wise princess’ to ensure that ‘the clothing and the ornaments of her women, though they be appropriately beautiful and rich, be of a modest fashion, well-fitting and seemly, neat and properly cared for. There should be no deviation from this modesty nor any immodesty in the matter of plunging necklines or other excesses.'

J.L. Laynesmith, Cecily Duchess of York

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fascinating World of Medieval Fashion

Medieval fashion was a rich tapestry of color, texture, and symbolism, reflecting the social hierarchy and cultural values of the time. From the opulent attire of royalty to the humble garb of peasants, clothing played a vital role in expressing identity and status.

At the top of the social ladder, nobility flaunted their wealth and power through elaborate garments made from luxurious fabrics such as silk, velvet, and brocade. Men adorned themselves with intricately embroidered tunics, embellished with jewels and fur trimmings, while women wore voluminous gowns with tight-fitting bodices and flowing skirts. Sumptuary laws regulated who could wear certain fabrics and colors, ensuring that only the elite could flaunt their riches.

In contrast, peasants dressed in simple, practical attire suited to their daily tasks. Men wore tunics and breeches made from coarse wool or linen, while women donned plain dresses cinched at the waist with a simple belt. Clothing was primarily functional, designed to withstand the rigors of manual labor rather than making a fashion statement.

The medieval fashion industry was driven by skilled artisans and craftsmen who produced clothing, accessories, and textiles using traditional techniques passed down through generations. Tailors, weavers, and dyers worked tirelessly to create garments tailored to individual measurements and personal tastes.

Fashion trends were influenced by factors such as religion, politics, and cultural exchange. The Crusades, for example, introduced Europeans to the luxurious fabrics and intricate designs of the East, sparking a fascination with oriental motifs and textiles.

Despite the stark divide between the rich and the poor, medieval fashion provided a means of self-expression and identity for people from all walks of life. Whether dressing for a royal court or a village festival, clothing played a pivotal role in shaping medieval society and culture.

In today's world, the legacy of medieval fashion lives on in historical reenactments, period dramas, and fashion inspired by the elegance and grandeur of the Middle Ages.

#The fascinating world of medieval fashion review#Medieval fashion History#Facts about medieval fashion#Medieval fashion timeline

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Borderline Personality Disorder The following research report focuses on a population at risk, those diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder. The report is offered in three sections. Part I provides an examination which looks at statistics related to the disorder. A definition of the disorder is given, with implicit defining characteristics of the population at risk. Causes are discussed with a relevant literature review. Social justice issues are looked at, with a discourse offered on factors of social oppression related to the population at risk. Part II discusses two courses of treatment with associated issues related to Borderline Personality Disorder, with an in-depth review of Mentalization therapy Dialectical Behavior Therapy. Part III discusses the political and social context of the issues relevant to the population at risk. Research on the NASW Code of Ethics is offered. The strengths perspective is discussed and the role of the Advanced Generalist Model is examined for finding treatment solutions to the at-risk population of those diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder. A conclusion is offered to highlight the salient points of the report and to synthesize the topics. The At-Risk Population: Borderline Personality Disorder The population-at-risk chosen for the following report are those people that have been diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). This population was selected due to their high rates of hospitalization, suicide attempts, and suicide. Suicide rates for this population are estimated at 8-10% (Paris, 2002). People diagnosed with BPD typically face a chronic and long-term debilitating psychiatric condition, for which traditional therapies have proven of limited effectiveness. The lifetime prevalence of those diagnosed with BPD in the general population is approximately 5.9% according to a recent study (Grant, et al., 2008), being equally prevalent between men and women (Grant, et al., 2008). Extreme states of physical and mental disability are features of this disorder, especially among women. Psychiatric hospitalizations of those identified with Borderline Personality Disorder are on the magnitude of 20% (BPD Today, 2010). Borderline Personality Disorder Definitions Borderline Personality Disorder is a disorder of emotional regulation. People with this diagnosis have extreme difficulty regulating their emotions. Approximately 50% are clinically depressed, and 25% are classified with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder as well (BPD Today, 2010). Sexual abuse as a child is strongly associated with development of BPD, and some studies suggest between 40%-70% of those with BPD have been sexually abused (Bohus, Priebe, Dyer, & Steil, 2009). People with BPD often report severe childhood emotional trauma. Additionally, people with BPD may have predisposing factors, such as genetics, brain and neurobiological issues, and other environmental variables. Moreover, BPD may result from an inability to effectively deal with adolescent stress events (Zanarini & Frankenburg, 1997). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders defines Borderline Personality Disorder in Axis II, Cluster B Axis II disorders include personality disorders and mental retardation. Category B. includes dramatic, emotional and erratic disorders, such as BPD (American Psychiatric Disorders, 2000). Some critics have stated that BPD should not be on the Axis II disorders, but should instead be moved to Axis IV, which includes psychosocial and environmental issues that contribute to the disorder, or Axis I, which includes clinical, learning, and major mental disorders (New, Triebwasser, & Charney, 2008). People with BPD experience episodes of intense emotional instability, such as anger, anxiety, aggression, self-injury, or some type of substance abuse. These instances may last for a few hours to a day, yet be of a chronic, long-term nature. These people have distorted cognitions of themselves, and often view themselves as of low value, bad, and unworthy. Maintaining relationships is difficult for a person with Borderline Personality Disorder, and they may range from idealization of their significant other, to devaluation of that person, based upon some small infraction that is out of proportion to reality. Due to their intense emotional disregulation, people with BPD have trouble with social relationships as well. They are extremely sensitive to any criticism, perceiving these as some type of personal rejection. Responses to their emotional distortions on others are anger, distress, fear, aggression, and depression. The DSM-IV-TR gives the following diagnostic criteria for Borderline Personality Disorder (summarized): frantic efforts to avoid abandonment; a pattern of unstable relationships; unstable image of self; impulsive self-destructive behavior; recurrent low-injury threshold suicide attempts and self-mutilation; highly reactive mood states such as irritability; feelings of emptiness; frequent displays of temper; and stress-related ideation (American Psychiatric Disorders, 2000, p. 710). Causes Genetics Borderline Personality Disorder may be attributed to physiologic biochemical factors, brain abnormalities, environmental factors, or trauma-related issues. Abuse and neglect, often as a child, are strong predictors of developing Borderline Personality Disorder, especially if the child has been identified as ADD or ADHD, with increased risk if accompanied by factors of Conduct Disorder before age 15 (Zanarini & Frankenburg, 1997). A combination of genetics and environment is thought to contribute to BPD; first-degree biological relatives with BPD indicate a five-fold increase in the possibility of developing Borderline Personality Disorder than compared to the general populace (American Psychiatric Disorders, 2000). Being a victim of some type of violence, especially rape, is a strong predictor of an adult developing BPD. If the violent event has resulted due to poor judgment or risky behavior, these factors support a diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder as well (Bohus, Priebe, Dyer, & Steil, 2009). People diagnosed with BPD often display abnormal brain neural circuitry regulation in emotion regulation. The prefrontal cortex of the brain is involved in dampening fear and stress responses which originate in the amygdala, located in the deep brain structures. MRI imaging of people with BPD show a marked decrease in prefrontal regulation of amygdala-generated neural responses (Ruocco, Medaglia, Ayaz, & Chute, 2010). Additionally, people with BPD have decreased activity in certain brain neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, dopamine, acetylcholine, and norepinephrin, likely due to genetic factors that are aggravated in stress situations (Steele & Siever, 2010). Drugs that act to enhance and sustain levels of these neurotransmitters in the neuron's pre-synaptic gap for longer periods tend to reduce symptoms of Borderline Personality Disorder. Drugs that stabilize the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA are shown to help stabilize the mood of those with BPD as well, reducing the ideation-mood disturbance episodes common in BPD (Stoffers, Vollm, Rucker, Timmer, Huband, & Lieb, 2010). While there is a complex interplay of the causes and triggers of BPD, studies exist which attempt to explain discrete elements of the causes of the disorder. Distel et al. (2009) report that 35-45% of the variance in BPD can be explained by genetic factors, though the study did not find much evidence of the cultural transmission of the disorder from parent to offspring, suggesting a strong role for genetics (Distel, et al., 2009). Bornovalova et al. (2009) state that results from longitudinal twin studies supports a causal link for genetics and environment in BPD, with an overall decline of BPD characteristics with advancing age. This last factor also supports the role of genetics being influenced by the environment in BPD, as greater stability in work, social, and personal relationships tends to be increase in the fourth decade of life and beyond (Bornovalova, Hicks, Iacono, & McGue, 2009). Abuse, Neglect, Violence, and Trauma People with Borderline Personality Disorder have reported to be the victim of some type of traumatic event, most likely a violent abuse situation, with sexual abuse being the most commonly reported abuse for women. This event typically occurs in childhood, though BPD can result from adolescent and adult-related trauma as well (Paris, 2002). McLean and Gallop (2003) report that women who have experienced sexual abuse as a child had significantly higher associations of developing BPD than if they experienced the abuse as an adult, though both groups exhibited early symptoms of both Borderline Personality Disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (McLean & Gallop, 2003). People with BPD often verbally attack and verbally abuse those they have relationships with. Indeed, the BPD person was often similarly verbally abused in their past as well. Borderline Personality Disorder often follows the patterns of abuse that the person with BPD has experienced in the past, with the BPD person inflicting domestic (spousal) abuse, physical and emotional abuse of strangers, child abuse, and self-abuse. Breaking the cycle of pain and abuse entails a comprehensive therapeutic approach in both cognitive psychiatric services and pharmacological intervention (Grant, et al., 2008). Social Justice Issues The concept of social justice has different meanings in different paradigms of study and thought; for purposes of this report, social justice refers to those diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder who have experienced inequality and unfairness due to their disorder. This social justice aspect of the disorder contributes to the risk that this population is encountering. People who have BPD encounter difficulty in the work environment. This presents a challenge to employers as they struggle to deal with the disability issue at hand. The employee with BPD may not be recognized as having a mental illness, and instead seen as a disruptive element in the workplace. They may be ostracized, demoted, or even fired from employment (McDonald, 2002). People living with mental illness are often marginalized, demeaned, and seen as being outside the normal boundaries of society. For people with BPD, this is doubly painful as it reinforces their sense of worthlessness and victimization, and may even lead to suicide attempts. For those who can recognize they have BPD, yet not know how to deal with it, the social stigma may lead them to attempt to cope with the disorder on their own rather than seek medical treatment. This is a failed situation that has no good outcome (Paris, 2002). As chronic sufferers of BPD are often victims of abuse themselves, the pain associated with the early trauma may turn into a perpetuating cycle of repeated suffering as they struggle to cope with their disorder. As one doctor notes, there are nine potential symptoms of the disorder, and over 200 potential presentations; the possibility that the disorder may be misunderstood by society and by therapists is high (Hoffmann, 2007). A concept known as 'surplus stigma' is attached to the disorder, due to misunderstandings associated with the disorder. These misunderstandings resulting in surplus stigma include the schizophrenogenic-mother concept, a refusal by therapists to treat those with BPD, unfavorable public information about the disorder, and controversy over the legitimacy of the disorder as a true clinical disorder worthy of treatment (Hoffmann, 2007). Avirim et al. (2006) report that BPD is viewed negatively by therapists and clinicians. This negativity affects the treatment that the BPD sufferer receives. In society the person with mental illness is often marginalized and stigmatized, with great social distance put between them and the 'normal' population. Therapists may perpetuate this distancing by emotionally distancing themselves from their BPD patients. While the therapist's response may be one related to self-protection in dealing with the BPD patient, the response is one that may be expected when relating to the person with Borderline Personality Disorder who is unusually sensitive to criticism and rejection. Therefore the consequence of such a therapist/BPD patient relationship perpetuates the cycle of mental illness, as the BPD patient does not receive the treatment that they need and instead receive treatment that reinforces their mental illness due to the stigmatization given to them by their therapist (Avirim, Brodsky, & Stanley, 2006). Summary of Part I People who have been diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder have intense emotional disregulation and an inability to deal with relationships. They are often victims of abuse themselves, and causes of the disorder are a complex mix of environmental factors and genetic factors. A person may be predisposed to BPD if they are a first degree biological relative of someone who has BPD. Additionally, there may be inherent genetic factors that are aggravated by stress or trauma and that predispose a person to developing Borderline Personality Disorder. Sexual abuse in childhood is a predictor of developing BPD for abused women; Post Traumatic Stress Disorder may also accompany BPD, along with associated mood disorders such as depression and anxiety. People with BPD often act inappropriately with others, exhibiting aggression, irritability, disassociation, blame, and ideation. Social injustice issues related to those living with BPD relate to a misunderstanding by society of the disorder which contributes to marginalization and stigmatization. Therapists also may perpetuate the cycle of the mental illness by treating their patients with surplus stigma, and distancing themselves from their patient which exacerbates the condition. People with BPD have high suicide attempts and suicide rates, and often engage in self-mutilation and self-abuse. The need to find effective treatments for the population living with Borderline Personality Disorder is paramount. Effective treatment would result in better social outcomes for the BPD person and their families. Work relations would improve, and BPD patients could enjoy positive social experiences that are self-reinforcing. Rates of hospitalization would decrease for this population, resulting in a decrease in the burden on the healthcare system in treating these patients within a crisis situation, which is often costly. Decreasing suicide rates, enabling BPD patients to enjoy a life of optimum mental health and not just a life with minimized discomfort, and reducing hospitalizations would all benefit the social system within which this population resides. Part II: Practice Approaches in Treating Borderline Personality Disorder Traditional therapeutic approaches of cognitive behavioral therapy and medication management have proven to be of limited effectiveness is treating those with BPD. Low rates of compliance for pharmacological management and a tendency of this population as a whole to terminate psychotherapy have perpetuated the negative effects of this disorder for those diagnosed with the disorder and for those dealing with the person with BPD. There is a clear need for a better treatment approach, a best-practices model for treating Borderline Personality Disorder. Traditional approaches of limited efficacy include conflict resolution and social learning theory. A brief look at the role of conflict resolution in treating Borderline Personality Disorder is offered to set the stage for a discussion on more effective therapies. A discourse follows on the conflict resolution review, which examines two different practice approaches: Mentalization in the group approach, and dialectical behavior therapy at the individual level. Conflict Resolution This brief review is offered as contextual material for understanding the limitations of therapeutic approaches that do not deal with the base personality disorder, which relates to the distorted cognition of those with BPD. Conflict resolution has been used as treatment strategy in Borderline Personality Disorder to help people management their relationships better. The downside is that it ignores the root causes of the problem and so offers only a partially effective treatment with an unknown effective duration. However, conflict resolution can be very helpful in BPD patients to learn how to approach and effectively deal with issues arising in their relationships, with relevance to the nature of their disorder. A person with BPD encounters a base dysphoria that may be broken by episodes of anger, extreme sarcasm, or another marked reactivity of mood. This can cause a serious hardship in the relationships of the person with BPD, especially upon family, children, and co-workers. Using conflict resolution strategies can enable those with BPD to have an acceptable and appropriate framework for approaching relationships in a positive manner (Sperry, 2003). Not surprisingly, people with BPD are reported to have difficulties in attentional neural networks associated with the ability to resolve conflict. Posner et al. (2002) report that BPD patients showed greatly reduced ability to resolve conflict among various study stimulus dimensions than did temperament-matched controls, notably in the areas of a reaction-time task and self-reported effortful control (Posner, et al., 2002). Clearly there is a role for incorporating conflict resolution strategies within a larger therapeutic framework, yet this method should be seen as an adjunct to therapy which deals directly with the cognitive problem of the personality disorder. Mentalization Mentalization is a form of psychodynamic psychotherapy with an aim of revealing the underlying psychic tensions of Borderline Personality Disorder. It was developed especially for BPD patients, with a theory that BPD patients have not developed a normal Mentalization framework for attachment relationships (Bateman & Fonagy, 2008). Mentalization refers to the ability to understand oneself and others based on obvious behaviors; Mentalization is also seen as a form of mental activity that allows one to recognize behaviors based on internal mental states (Busch, 2008). Four major aims of Mentalization-based treatment are to improve behavior, mood stability in response to stimuli (affect regulation), have better relationships with others, and have the ability to go after goals in life (Bateman & Fonagy, 2008). Treatment typically involves a two-week cycle of treatment, with the therapist alternating the treatments between individual and group treatments. For purposes of this particular review of Mentalization, the focus will be on group treatment. In Mentalization therapy, the therapist attempts to form an attachment bond with the patient. This establishes a safe and appropriate attachment bond that the patient can relate to, thereby increasing their ability to understand their own behavior and the behavior of others; this process is increasing the patients Mentalization (Busch, 2008). In these safe attachment bonds the patient is encouraged to explore issues of their cognition, recognize those problems, and develop positive psychological mechanisms. Through the safe attachment bond, the affect recognition arousal issues can be moved from the state of dysfunctional disorganized attachment to positive and appropriate attachment Mentalizations (Bateman & Fonagy, 2008). In the group therapy sessions, the therapist guides the patient to form safe attachment bonds with members of the group. The group dynamic offers a way for the BPD patient to understand 'how' to form safe attachment bonds and understand their own distorted cognitive processes. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

When the monster Manual list a specific save do you add that to the monster's stat bonus?

@JeremyECrawford When the monster Manual list a specific save do you add that to the monster's stat bonus or is that the total save modifier — kent dyer (@saxononyx) November 15, 2016 Take a look at the Monster Manual introduction, specifically the section on saving throws (p. 8). In a stat block, save bonus = total. #DnD https://t.co/SXaO7XYHQG — Jeremy Crawford (@JeremyECrawford) November 15,…

0 notes

Text

I enjoy the way The Magnus Protocol, as of episode 5, keeps the oddness of the characters mostly within the bounds of normal office comedy tropes. (Longish bit of character analysis, vague spoilers).

Lena is robotically following a how-to-be-a-manager manual ("people like cake"), knocks back promotion ambitions from competent staff, and doesn't consider staff mental health to be her problem? Yeah sounds like a typical middle manager. Less so that she may have killed a previous employee but still. I have been a middle manager, maybe she had reasons. Also "had to kill someone" is potentially grounds to be emotionally distant have boundaries with the current crop. Managers should never get too attached to their teams and she's obviously overseen a lot of staff turnover, which is natural in some jobs - such as those with respectable wages but no advancement prospects or sense of purpose, as seems to be the case here. Lena could be evil, could just be tired. What does Lena want? For things to run smoothly.

Alice? The jokester, in it for the salary, cares about her colleagues but not emotionally involved in the job and considers this healthy. She's stuck around for ages because she's not going to fall for this "corporate ladder" or "taking work home mentally" nonsense. Given the work this may well be the perfect strategy. The entities, or grind culture, ain't getting no hold on Alice Dyer. What does Alice want? To get paid.

Colin, the IT manager who thinks the computer system is trying to kill itself and doesn't trust central support. Yeah yeah, we've all known IT managers, they're territorial and generally like that. And if you have ever worked for a big organisation, you know that involving central support is death to your chance of actually solving the problem. What does Colin want? To do his job properly.

Gwen, the ambitious overachiever clearly in the wrong place, who takes the crappy job ridiculously seriously. Understandably resents Alice for being more appreciated than she is with a fraction of the effort, but can't stop herself trying. What does Gwen want? Lena's job (the fool), to do things properly.

...and Sam, new, soaking up advice, still näive enough to tell the bosses that someone's upset. (What did he expect Lena to do about Colin? You can't force people to go to therapy for trying too hard at their job). What does Sam want? The most unclear of the lot right now.

#obviously some of these are likely to prove untrue#but they're all plausible#lena kelley#colin becher#character analysis as of episode 5#tmagp#tmagp spoilers

0 notes

Text

AMA CON LA CERTEZA DE QUE SERÁS AMADO, ama sin buscar sobras, amor que acepta no ser amado.

AMOR CON SEGURIDAD DE SI MISMO...

Dejo mis monstruos en papel.

Mis fantasmas se duermen en la poesía que sólo yo leo.

Mis traumas se están desmoronando a la edad que vivo.

"Aunque un hombre trabaje duro, guiado por la sabiduría, el conocimiento y la habilidad, tendrá que entregar todo lo que ha ganado a alguien que no ha trabajado por ello. Esto también es vanidad y una gran vergüenza".

(Manual de vida)

MIENTRAS QUEDE ALGO DE FUERZA.

Todavía continuaré.

Mientras quede un breve sueño, seguiré luchando.

Mientras quede algo de vigor es posible no darse por vencido.

“Te tratan como les has enseñado a otros a tratarte”.

(Wayne Dyer)

"Los pensamientos de los justos son rectos, pero las direcciones de los impíos son engañosas".

(Libro de la Sabiduría)

"Estas palabras transmiten una fuerte determinación y la importancia de persistir, incluso frente a los desafíos. Es como si fueran un recordatorio para seguir adelante, independientemente de las circunstancias. Y la frase sobre ser tratado de la manera en que enseñaste a otros a tratar Destacas la reciprocidad en las relaciones interpersonales. Es algo para reflexionar sobre cómo nuestro propio comportamiento influye en la forma en que los demás nos tratan."

(Comentario de Internet)

0 notes

Text

Martindale Abrasion and Pilling Tester - Everything You Need to Know

Durability, Functionality and Quality is the essence of every product performing to its best capacity. To make sure that the products meet the required quality and durability, a martindale abrasion tester is used in the textile industry. In this article, we will be covering all you need to know about the Martindale Abrasion and Pilling Tester, its history, working and how it benefits the garment and textile industry.

What is a Martindale Abrasion and Pilling Tester?

Martindale abrasion and pilling tester is a testing instrument that simulates the wear and tear of fabrics due to frequent usage. The martindale abrasion machine is a combination of two tests Martindale Abrasion Test and Martindale Pilling Test. This circular testing machine is used to determine how long fabrics will last by subjecting them to regulated abrasion forces. It is named after its inventor, Dr. James Graham Martindale.

The History of Martindale Abrasion and Pilling Tester

Martindale Abrasion and Pilling Tester that is used to test the abrasion and pilling properties of a fabric dates back to the early 1900. The Martindale abrasion test was developed in the early 1900s by Frank F. Martindale, a British engineer and member of the Society of Dyers and Colourists. The original version of the Martindale abrasion tester was a manually operated device that could test the abrasion resistance of fabrics. Over the years, the instrument underwent several improvements and modifications, and electronic versions were introduced in the 1950s, making testing more accurate and efficient.

The Martindale pilling test, on the other hand, was developed in the 1960s by Harold Francis, another British textile engineer. This test is used to determine the tendency of fabrics to form pills, or small balls of tangled fibres, due to wear and friction. The original version of the Martindale pilling tester was also a manually operated device, but electronic versions were later introduced, making testing more accurate and efficient.

Today, the Martindale Abrasion and Pilling tester is a highly advanced and efficient testing instrument that combines the Martindale Pilling test and the Martindale Abrasion test into one single instrument.

How Does a Martindale Abrasion and Pilling Tester Work?

Below, is a step by step working of a Digital Martindale Abrasion and Pilling Tester -

1. Preparation of the Sample: The fabric sample that is to be tested is prepared according to the desired shape and size.

2. Placing the Sample: The sample is subsequently clamped into place on the tester's testing platform.

3. Abrasion Test: The Martindale abrasion test, which gauges the fabric's abrasion resistance, makes up the first portion of the test. A set of abrasive felt on the tester rub against the fabric in a circular motion. Depending on the demands of the test, the operator sets the number of rubs, which can range from a few hundred to tens of thousands. The apparatus also gauges the sample's weight loss throughout the experiment.

4. Pilling Test: The Martindale pilling test, which is the second component of the test, gauges the fabric's propensity to create pills. A series of rotating brushes in the tester rub against the fabric in a circular motion. Depending on the demands of the test, the operator sets the number of rubs, which can range from a few hundred to tens of thousands. The equipment accurately counts the number of rubs required to form the pills on various types of fabrics.

5. Result Analysis: The Martindale abrasion machine gives a digital readout of the sample weight loss during the abrasion test, the number of pills generated during the pilling test, and other pertinent information when the test is over. This information is used to assess the fabric's strength and quality, as well as whether it complies with specific industry requirements.

The Benefits of Using a Martindale Abrasion and Pilling Tester

Martindale abrasion machine is a widely used testing instrument because of the numerous benefits it offers. Some of these benefits include -

It helps to evaluate the quality and durability of fabrics.

It is useful to determine the pilling tendency of fabrics.

It can be used to predict the fabric's behaviour during regular usage.

It identifies the abrasion resistance of fabrics.

It adheres to the required and necessary industry standards.

Overall, the martindale abrasion tester is an essential testing instrument in the textile industry to determine the longevity and quality of textiles.

#qualitycontrol#qualityassurance#martindale#abrasiontesting#pillingtesting#qualitycontrolassessment#testingequipments#performancetesting#paramountinstruments

0 notes

Text

Older!Horror Villains x Younger!Reader || Reactions

Reacting to: Someone at the store thinking that they're your grandparent- rather then your S/O. (Just something funny I was considering for Inkubus but decided to just do for all of them ^^ XD 😅)

Characters Included: The gilfs of the fandom 😅 ? I'm thinking 50 years and above. Captain Spaulding, Drayton Sawyer, Granny Boone, Inkubus, Jedidiah Sawyer, Luda Mae Hewitt, Mayor Buckman, Mental Manny / Manual Dyer, Peepaw Michael Myers, Norman Nordstrom, Otis B. Driftwood, Pamela Voorhees, Sheriff Hoyt / Charlie Hewitt Jr, Stuart Lloyd, the Taxidermist / Walter Harris and Winslow Foxworth Coltrane.

Warnings: Major age difference, bad language, sexual references, a really awkward misunderstanding...

Captain Spaulding: Spaulding's a pretty good sport about it XD In fact, he kinda enjoys it. Cuz then he gets to rub it in the persons face what a young, hot thing he's got going here with you and what- what did you say you had again?? Nothin'?? Yeahh, that's what I thought. Fuck right off, why dontcha?

Drayton Sawyer: Drayton goes so red and is about to blow his top. He gets enough shit from his brothers over this! He does not need one more moron bothering him about it! Fuck off! *Grabs you by the arm and storms off*

Granny Boone: "... Grandma, huh? Alright then!~ " *Turns to you* "Come here, sweetie, give grandmother a kiss~ " She's about to ruin that guys whole career 😅😅😅

Inkubus: Inkubus is not amused. Grandpa?? Absolutely not, no. He'll correct the person in the most embarrassing way possible.

Jedidiah Sawyer: Jed does not care at all 😅😅 The only person who's opinion matters to him is yours, so who cares if this guy thinks he's your grandpa? Fine then, he's your grandpa. So go and mow the lawn for him while he sits on the porch and has a sweet tea.

Luda Mae Hewitt: She's is gonna tear that guy a new one. Calling her old?? Son of a bitch, where is that persons manners?? She should set her damn sons on him.

Mayor Buckman: Sorry, Buckman cannot answer this question. He's too busy choking.

Mental Manny / Manual Dyer: Manny loves to correct people. He's got the biggest smile on his face as he goes oh you're mistaken- this is my beautiful partner. A little young, sure, but we sure don't mind~ Oh sweetheart, I think we're going be late for our dinner reservations. Shall we?

Peepaw Michael Myers: Like Jed he struggles to give a shit. Who cares??? He knows that he's not your grandfather and you know he's not your grandfather- that's all that matters. He doesn't care... but he does enjoy giving you a big kiss, with tongue, later when the guy sees you both again. He's a gremlin.

Norman Nordstrom: ... what? Norman is pissed at this idea, he hates it. He feels like a digusting predator (*cough* which he is, though not because you like him ^^) and it hits close to home. He's going to need you to set it straight.

Otis B. Driftwood: "... Ha! Okay, pal, check this out." He'll say, then turn around and basically make out with you right there in front of the guy. Otis is not amused at the poor insinuation and takes it out with lewd efficiency.

Pamela Voorhees: Again- not amused. As far as she's concerned, this total stranger has no business making disgusting insinuations about the two of you, anyway. So she'll ruthlessly take them down a notch with her words- and sweet smile.

Sheriff Hoyt / Charlie Hewitt Jr: "... you think you're funny? No I ain't their fucken grandpa. Didn't your bitch momma ever teach you to mind your business? Oh don't you worry, I can do it for her." Just- my friend- just keep him from taking out the damn shot gun.

Stuart Lloyd: "... oh... uh... n-no, actually- " Stuart forces himself to stutter through a quick explanation- but he wants to crawl into a whole and die (:

Taxidermist / Walter Harris: Gets the nervous giggles 😅😅😅 Doesn't correct them.

Winslow Foxworth Coltrane: Annnnd Foxy loves it XD He was already one kinky mother fucker- you can use this as foreplay. Let him smack your ass while they're still looking but call you 'Hon' or 'Sweetie'- he finds it funny and hot in equal measures.

#Older!Horror Villains x Younger!Reader Reactions#Older!Horror Villains x Younger!Reader#Horror Villains x Reader Reactions#Horror Villains x Reader#Winslow Foxworth Coltrane#Foxy Coltrane#Walter Harris#Stuart Lloyd#Sheriff Hoyt#Charlie Hewitt#Charlie Hewitt Jr#Pamela Voorhees#Otis B Driftwood#Norman Nordstrom#Michael Myers#Peepaw Michael Myers#Mental Manny#Manual Dyer#Mayor Buckman#Luda Mae Hewitt#Jedidiah Sawyer#Granny Boone#Inkubus#Drayton Sawyer#Captain Spaulding#x Reader#Reactions#Horror Villains#Slashers

583 notes

·

View notes

Note

Would you please do a Mental Manny X Reader? If you're comfortable with it of course. I love your writing 🖤

OOOOH my first funhouse request!! i’m so excited!! i freaking love this movie, though of course i adore all the slashers, these guys are just amongst my faves!

i wasn’t sure if you wanted me to include nsfw or had anything particular in mind but let me know if you do and i am happy to do more!

Manual “Mental Manny” Dyer x Reader

warnings for yandere content!

- Manny strikes me as a yandere-type partner, he just oozes possessiveness and manipulation, considering his previous crimes

- if he can convince a small army of people to do unspeakable things, he can work his magic on you and ramps up the charm to really draw you in

- don’t get me wrong, if you’re with him then he clearly cares about you, but he’s also stuck in the habits of needing control as well as the lingering anxiety over losing the one good thing he has

- you challenge him, keep him on his toes and it’s so foreign to him that at first he isn’t sure if he likes it or not (he does, he just won’t admit it)

- get ready for a lot of pda

- he’s a total showman in every social situation and your relationship is no exception; he’ll have his arms around you from behind, a hand in your hair, or his personal favourite is you on his lap

- big on respect though, if someone greets him but not you, he will pull them up on it

- pity the poor sucker who makes a move on you or hurts you in any way

- although he’s not very subtle about his violent capabilities, he doesn’t want you seeing that side of him too often. if someone is hitting on you or making you uncomfortable in general, he will wait like a hungry cat awaits his prey, until you’re busy or out of sight before he will “deal” with them

- loves when you reciprocate his advances & affection, dude’s been sat in a cell for goodness knows how long and you’re just different to have captivated him, so the most innocent of touches or that sultry little smile of yours switches something on in his brain - you can practically see the black of his pupils overwhelming the blue of his irises

- if you want to leave, guess who’s suddenly really sick?? bingo! he’s very good at showmanship, as mentioned, so he’s a fantastic actor and his poor-me-puppy-eyes penetrate your very soul

- likely the kind of partner to want to spoil his s/o

- will take the greatest of pleasures during times of rest with you when you can both just enjoy privacy, wrapped up in long conversations and mutual intrigue

#mental manny x reader#manual dyer x reader#funhouse massacre#reader insert#imagines#Headcanon#slashers#horror#yandere

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

I was hand dyeing a dress today and have come to the conclusion that the seamstresses/tailors dyers whoever would also have super buff/toned arms ( I was only doing a slip too!) and I feel like the more I think about it the keep would all be buff as hell , including the household every profession need manual labour

the point here being I love the idea of a lord or whatever seeing like a super buff person asking what witcher school they are then being told oh me? I'm human

I think most people in Kaer Morhen are in pretty good shape, yeah, if only because of all the stairs! But being a servant or craftsperson was probably very good for one's arm strength, yes.

(It doesn't help that the servants all wear medallions, too... XD)

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recommended Reading - Self-Help, Dating, Relationships

"The flame never dies because the commitment never ends."

1) Daniel Goleman – Emotional Intelligence, Social Intelligence, Primal Leadership

2) Anthony Robins – Awaken The Giant Within

3) David Deida – Way of the Superior Man

4) Dale Carnegie – How to Win Friends and Influence People

5) Robert B. Cialdini – Influence, Yes!

6) Paul Ekman – Emotions Revealed, Telling Lies

7) Barbara Pease, Allan Pease – The Definitive Book of Body Language

8) Michelle Lia Lewis – Flirting 101

9) Eve Eschner Hogan – Intellectual Foreplay

10) Gary Chapman – The Five Love Languages

11) Barbara De Angelis – What Women Want Men to Know, The Real Rules

12) Michael Webb – The RoMANtic’s Guide

13) Gregory Godek – 1001 Ways To Be Romantic

14) William Cane – The Art of Kissing

15) Nancy Friday – My Secret Garden

16) John Bridges – How to be a Gentlemen

17) Fonzworth Bentley – Advance Your Swagger

18) Steve Santagati – The Manual

19) Susan Page – If I’m So Wonderful? Why Am I Still Single?

20) Sherry Argov – Why Men Love Bitches

21) Matt Ridley – The Red Queen

22) Maxwell Maltz – The New Psycho-Cybernetics

23) Faye Flam – The Score

24) Janine Driver – You Say More Than You Think

25) Sakyong Mipham – Turning The Mind Into An Ally

26) Napoleon Hill – Think And Grow Rich, How To Be Rich

27) Geoff Colvin – Talent Is Overrated

28) Richard Templar – The Rules of Love

29) Robert T. Kiyosaki – Rich Dad Poor Dad, Increase Your Financial IQ, Unfair Advanage

30) Marshall B. Rosenberg Ph.D – Nonviolent Communication

31) Nathaniel Branden – The Six Pillars of Self-Esteem

32) Peter Green – Ovid The Erotic Poems

33) Don Miguel Ruiz – The Four Agreements, The Mastery of Love

34) Stefan Klein – The Science of Happiness

35) Brian Tracy – The Psychology of Achievement (Audio CD)

36) Wayne Dyer – Your Erroneous Zones, Pulling Your Own Strings

37) Geoffrey Miller – The Mating Mind

38) Mary D. Esselman – The Hell with Love

39) Douglas Carlton Abrams – The Lost Diary of Don Juan

40) John Assaraf – The Answer

41) Malcolm Gladwell – Blink

42) Neil Strauss' Crowdsourced Reading Project 2012 Compilation PDF: http://societyinfo(dot)s3(dot)amazonaws(dot)com/crp(dot)zip

43) Rowland S. Miller – Intimate Relationships 6th Edition

44) www.thegreatcourses.com – Effective Communication Skills, How Conversation Works, Influence, The Everyday Gourmet, Changing Body Composition through Diet and Exercise

45) Willard F. Harley, Jr. – Love Busters

46) Betsy Prioleau – Swoon, Seductress

47) The Attraction Forums – Classic Writings Archive: http://t.co/fNqvDHZ34t

48) Nick Savoy – It’s Your Move

49) Daniel Bergner – What Do Women Want?

50) Robin Dreeke – It’s Not All About Me

51) Olivia Cabane – The Charisma Myth

52) Steven J. Stein – The EQ Edge

53) Karl Albrecht – Social Intelligence

54) Guy Winch – Emotional First Aid

55) Aziz Ansari – Modern Romance

56) Ryan Holiday – Ego Is The Enemy

57) Tucker Max, Geoffrey Miller PhD – Mate

#dating#dating advice#datingadvice#self help#selfhelp#bookaddict#booklover#relationship#relationships#relationship advice#relationship building#relationshipadvice

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

Question: were medieval peasants always on the edge of starving, as in couldn't waste food? Or did that vary with time and place? Thanks in adavance!

Well, I have to say that it must be fairly obvious that when we’re talking about a span of roughly one thousand years in an entire continent, in multiple countries/kingdoms/geopolitical situations, and over the course of large-scale, macro-level geographical, climate, crisis, and cultural incidents, it would indeed vary, sometimes wildly, and this is the case for almost any factor that you could possibly think of. It will not surprise you to learn that “medieval peasants were always on the brink of starving” is yet another tired old cliche from the Bad Old Middle Ages grab bag, and while it reflects a different system from modernity, it is not necessarily the case that it was always worse (especially considering the prevalence of hunger in the modern world and the parallel universes in food access between rich and poor, which were simply never that extreme in the medieval era). Today, there’s no relationship whatsoever between how rich people eat and how poor people eat; they exist in completely separate realms. Rich people simply have no worry about disruption to food supply, reliance on local economy or agriculture, the impact of natural disasters, or anything else; globalization and worldwide supply chains means that they can be assured of whatever they want, whenever they want it. Even wealthy people in the Middle Ages did not exist in their own ecosystem the way modern rich people do. Their food was grown on the same land, was subject to the same possible impacts of famine or crop failure, was reliant on having farm labor to cultivate it, and otherwise came from the same place as the food of poor people. Obviously class, status, and money affected what goods a medieval citizen had access to, whether in food or anything else, but food inequality and disparity is WAY more of a thing in modernity than it was in the Middle Ages.

Next, when we say “medieval peasants,” do we mean literal peasants, i.e. manual laborers tied to a single plot of land who worked it, harvested its crop yields, owed rent to a local landlord, and were often rural and on the subsistence level? Because obviously, there are social differences among peasants too, and some of them could be quite wealthy. In his usefully titled “Did the Peasants Really Starve in Medieval England?”, Christopher Dyer points out that the upper class of peasants, who had about thirty acres of arable land and access to common pastures, would easily be able to provide themselves with bread, potage (soup) and ale on a daily basis, have consistent access to dairy and meat, and even enough money to buy extra fish, meat, and prepared foods like pudding and pie from the village or market town. It would be easy for them to eat the usual 2000 calories a day, and their diet would be relatively flavorful and nutritious even by modern standards. Poorer peasants would be more reliant on just bread, potage, and ale, and have less access to meat and dairy, but they still weren’t outright starving. Manual labor doesn’t go well if the laborers are constantly underfed and/or weak from malnutrition, and while the poorest peasants’ diet would have been fairly monotonous and carb-heavy, it still would provide raw calories for energy.

Nor were food economies exclusively local, as that equally tired cliche that people never traveled more than ten miles from home would have you believe (honestly, where did that even come from?) As Food in Medieval Times puts it, “A remarkably wide variety of foodstuffs was available to consumers in the Middle Ages. Besides homegrown and raised products, exotic fruits and spices were brought by Arab merchants into the Mediterranean markets and sold across Europe at premium prices. Although bad harvests resulting in famine and disease occurred periodically, the staple foods -- bread, dairy products, cheap cuts of meat, and preserved fish -- were usually available to the general population. In richer households the foodstuffs were more exclusive and the dishes more sophisticated and varied.” Regional differences would obviously thus play a part. Common people in Iberia, Italy, and southern Europe would be more easily able to access certain delicacies not available in relatively barren England and northern Europe, and would be geographically closer to the Mediterranean markets. They still would not be able to afford expensive delicacies like saffron or other fine spice, but that doesn’t mean they never had it at all. There were many feast days and festivals in the religious and liturgical calendar, and communities would come together with food just as they do now.

There were also social welfare systems and safety nets, wherein, for example, ageing peasants could retire and be provided with a food pension by their landlord (there are numerous legal contracts of this nature, which had to be written down since what a surprise, the landlords didn’t always keep their word or honor their obligations). Even serfs didn’t have to work until they keeled over; they could take retirement and be provided with a portion of the food yield of the estate from their working-age peers, indeed rather like Social Security. There were also almoners at churches, monasteries, and other religious houses, who relied on donations from rich patrons with guilty consciences in order to feed the destitute poor, like a modern-day soup kitchen. These arrangements would obviously not have covered everybody (once again, we note, food banks and food stamps and other arrangements don’t do that for modern people either), but it doesn’t mean there was no recourse.

Of course, the food economy was more perilous than it is now, and more prone to natural disasters and agricultural disruptions. There are certainly famines recorded throughout the medieval period (such as the Great Famine of 1315-18), and several years of bad harvests could have a devastating impact on rich and poor alike. (Since again, the rich didn’t have their own entirely separate ecosystem; their food had to come from the same place as their poorer counterparts.) Climate change, too little rain, too much rain, drought, fire, pestilence, or anything else, in the absence of industrialization, mass farming techniques, factories, or anything of the sort, meant that food supplies were vulnerable to the natural environment, and people did die of hunger in the bad years. While standards did also change and improve over time, the earlier (pre-11th century) medieval period was not necessarily always worse. After the Black Death, when there were simply much fewer people than before, and increasingly so in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, peasants usually had fairly reliable access both to raw food and cash to purchase prepared food. By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the threat of widespread food catastrophe had largely subsided; there aren’t any major famines recorded in Europe at this time, though we daresay they had plenty of other problems (not least the wars of religion). Of course, that little thing in 1492 had also happened, opening up the Columbian Exchange and new routes of supply to the New World, including large-scale transportation and trade of food.

As I’ve mentioned in at least one other ask, people also knew how to cook food properly; someone studied the latrines at Warkworth Castle in northern England (don’t ask me who thought that this is a fun research project, but it takes all kinds) and discovered a remarkable lack of food-borne pathogens. In other words, even without modern safety standards or exact temperature guidelines, people were well aware how to cook food so it tasted good and wouldn’t kill you. They also took pride in doing so. In “The Evolution of Culinary Techniques in the Medieval Era,” Barbara Santich explores the evolution of written recipes from a few notes intended to remind the chef of something they already knew, to a more detailed programmatic for someone who might not have actually made the dish before. Skilled cooks were highly prized members of middle-class and upper-class households, and people who had money to spend on food enjoyed banquets, diverse dishes, and whatever delicacies they could get from their local merchants and markets. The extensive system of medieval trade networks, as mentioned above, meant that consumer goods could travel a very long way indeed, and while you couldn’t walk into a supermarket and get whatever you wanted whenever you wanted it, there would be at least some opportunity for you to acquire something new.

Anyway, yes. Medieval peasants: usually not starving. There you have it.

220 notes

·

View notes