#Negro Anthology

Text

Nancy Cunard, of the English shipping family, announced on May 2, 1932 that she had been disinherited by her mother for her relationship with Henry Crowder, an African-American jazz musician. Cunard was a famously flamboyant bohemian writer and political activist whose best-known work was editing Negro Anthology, a huge compendium of work by Black writers. The photo shows Cunard with John Banting, left, a painter, and Taylor Gordon, right, a writer, in front of the Harlem hotel.

Photo: Associated Press via the NY Times

#vintage New York#1930s#Nancy Cunard#racism#Negro Anthology#Harlem Renaissance#2 May#John Banting#Taylor Gordon#May 2#vintage Harlem#British aristocracy

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sorry about the outdated language; this album is from 1954.

0 notes

Text

Today We Honor Alain LeRoy Locke

Alain LeRoy Locke is heralded as the “Father of the Harlem Renaissance” for his publication in 1925 of The New Negro—an anthology of poetry, essays, plays, music and portraiture by white and black artists.

Locke is best known as a theorist, critic, and interpreter of African-American literature and art. He was also a creative and systematic philosopher who developed theories of value, pluralism and cultural relativism that informed and were reinforced by his work on aesthetics.

CARTER™️ Magazine

#wherehistoryandhiphopmeet#historyandhiphop365#cartermagazine#carter#staywoke#alainlocke#blackhistory#blackhistorymonth#history

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

At present, it is standard among practically all communities to fête the family as a bastion of relative safety from state persecution and market coercion, and as a space for nurturing subordinated cultural practices, languages, and traditions. But this is not enough of a reason to spare the family. Frustratedly, Hazel Carby stressed the fact (for the benefit of her white sisters) that many racially, economically, and patriarchally oppressed people cleave proudly and fervently to the family. She was right; nevertheless, as Kathi Weeks puts it: “the model of the nuclear family that has served subordinated groups as a fence against the state, society and capital is the very same white, settler, bourgeois, heterosexual, and patriarchal institution that was imposed by the state, society, and capital on the formerly enslaved, indigenous peoples, and waves of immigrants, all of whom continue to be at once in need of its meagre protections and marginalized by its legacies and prescriptions” (emphasis mine). The family is a shield that human beings have taken up, quite rightly, to survive a war. If we cannot countenance ever putting down that shield, perhaps we have forgotten that the war does not have to go on forever.

This is why Paul Gilroy remarked in his 1993 essay “It’s A Family Affair,” “even the best of this discourse of the familialization of politics is still a problem.” Gilroy is grappling with the reality that, in the United Kingdom as in the United States, the state’s constant disrespect of the Black home and transgression of Black households’ boundaries, as well as its disproportionate removal of Black children into the foster-care industry, understandably inspires an urgent anti-racist politics of “familialization” in defense of Black families. Both the British and American netherworlds of supposedly “broken” homes (milieus that are then exoticized, and seen as efflorescing creatively against all odds), have posed an obstinate threat to the legitimacy of the family regime simply by existing, Gilroy suggests. The paradox is that the “broken” remnant sustains the bourgeois regime insofar as it supplies the culture, inspiration, and oftentimes the surrogate care labor that allows the white household to imagine itself as whole. As a dialectician, “I want to have it both ways,” writes Gilroy, closing out his essay. “I want to be able to valorize what we can recover, but also to cite the disastrous consequences that follow when the family supplies the only symbols of political agency we can find in the culture and the only object upon which that agency can be seen to operate. Let us remind ourselves that there are other possibilities.

There are other possibilities! Traces of the desire for them can be found in Toni Cade (later Toni Cade Bambara)’s anthology The Black Woman, published in America in 1970, not long after the publication of the US labor secretariat’s “Moynihan report,” The Negro Family: The Case for National Action. The open season on the Black Matriarch was in full swing. And certainly not all of the anthology’s feminists, in their valiant effort to beat back societal anti-maternal sentiment (matrophobia) and the hatred of Black women specifically (more recently known as “misogynoir”), make the additional step of criticizing familism within their Black communities. But one or two contributors do flatly reject the notion that the family could ever be a part of Black (collective human) liberation. Kay Lindsey, in her piece “The Black Woman as a Woman,” lays out her analysis that: “If all white institutions with the exception of the family were destroyed, the state could also rise again, but Black rather than white.” In other words: the only way to ensure the destruction of the patriarchal state is for the institution of the family to be destroyed. “And I mean destroyed,” echoes the feminist women’s health center representative Pat Parker in 1980, in a speech she delivered at ¡Basta! Women’s Conference on Imperialism and Third World War in Oakland, California. Parker speaks in the name of The Black Women’s Revolutionary Council, among other organizations, and her wide- ranging statement (which addresses imperialism, the Klan, and movement- building) purposively ends with the family: “As long as women are bound by the nuclear family structure we cannot effectively move toward revolution. And if women don’t move, it will not happen.” The left, along with women especially of the upper and middle classes, “must give up ... undying loyalty to the nuclear family,” Parker charges. It is “the basic unit of capitalism and in order for us to move to revolution it has to be destroyed.”

Forty years later, the British writer Lola Olufemi is among those reminding us that there are other possibilities: “abolishing the family...” she tweets, “that’s light work. You’re crying over whether or not Engels said it when it’s been focal to black studies/black feminism for decades.” For Olufemi as for Parker and Lindsey, abolishing marriage, private property, white supremacy, and capitalism are projects that cannot be disentangled from one another. She is no lone voice, either. Annie Olaloku-Teriba, a British scholar of “Blackness” in theory and history, is another contemporary exponent of the rich Black family-abolitionist tradition Olufemi names. In 2021, Olaloku-Teriba surprised and unsettled some of her followers by publishing a thread animated by a commitment to the overthrow of “familial relations” as a key goal of her antipatriarchal socialism. These posts point to the striking absence of the child from contemporary theorizations of patriarchal domesticity, and criticize radicals’ reluctance to call mothers who “violently discipline [Black] boys into masculinity” patriarchal. “The adult/child relation is as central to patriarchy as ‘man’/‘woman,’” Olaloku-Teriba affirms: “The domination of the boy by the woman is a very routine and potent expression of patriarchal power.” These observations reopen horizons. What would it mean for Black caregivers (of all genders) not to fear the absence of family in the lives of Black children? What would it mean not to need the Black family?

Sophie Lewis in “Abolish Which Family?” from Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation, 2022.

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

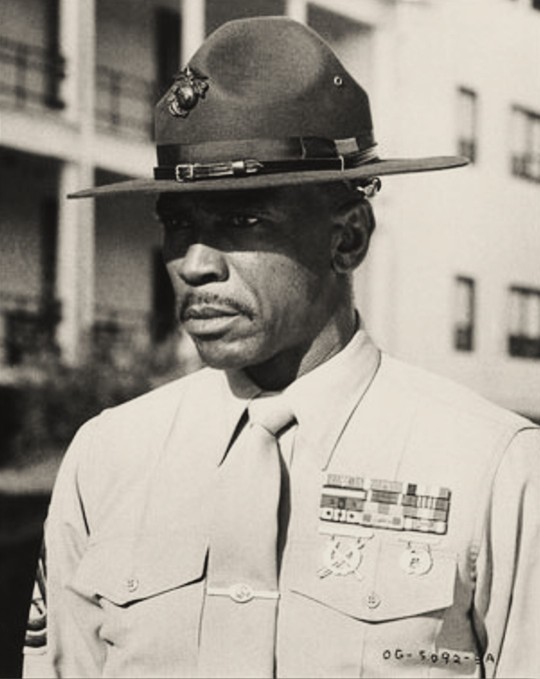

The actor Lou Gossett Jr, who has died aged 87, is best known for his performance in An Officer and A Gentleman (1982) as Gunnery Sergeant Emil Foley, whose tough training transforms recruit Richard Gere into the man of the film’s title. He was the first black winner of an Academy Award for best supporting actor, and only the third black actor (after Hattie McDaniel and Sidney Poitier) to take home any Oscar.

The director, Taylor Hackford, said he cast Gossett in a role written for a white actor, following a familiar Hollywood trope played by John Wayne, Burt Lancaster, Victor McLaglen or R Lee Ermey, because while researching he realised the tension of “black enlisted men having make-or-break control over whether white college graduates would become officers���. Gossett had already won an Emmy award playing a different sort of mentor, the slave Fiddler who teaches Kunta Kinte the ropes in Roots (1977), but he was still a relatively unknown 46-year-old when he got his breakthrough role, despite a long history of success on stage and in music as well as on screen.

Born in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, Louis was the son of Helen (nee Wray), a nurse, and Louis Sr, a porter. As a child he suffered from polio, but became a high school athlete before a basketball injury led to his joining the drama club. His teacher encouraged him to audition professionally, and at 17 he was on Broadway playing a troubled child in Take a Giant Step, which won him a Donaldson award for best newcomer.

He won a drama scholarship to New York University, but continued working, in The Desk Set (1955), and made his television debut in two episodes of the NBC anthology show The Big Story. In 1959 he was cast with Poitier and Ruby Dee in Raisin in the Sun, and made his film debut reprising his role in 1961. On Broadway that year he played in Jean Genet’s The Blacks, in an all-star cast with James Earl Jones, Cicely Tyson, Roscoe Lee Brown, Godfrey Cambridge and a young Maya Angelou; it was the decade’s longest-running show.

Gossett was also active in the Greenwich Village folk music scene. He released his first single Hooka Dooka, Green Green in 1964, followed by See See Rider, and co-wrote the anti-war hit Handsome Johnny with Richie Havens. In 1967 he released another single, a drums and horns version of Pete Seeger’s anti-war hymn Where Have All the Flowers Gone. He was in the gospel musical Tambourines to Glory (1963) and in producer Mike Todd’s America, Be Seated at the 1964 New York World’s Fair.

His plays became more limited: The Zulu and the Zayda and My Sweet Charlie; the very short run of Carry Me Back to Morningside Heights, in which he played a black man owning a white slave; and a revival of Golden Boy (1964), with Sammy Davis Jr. His final Broadway part was as the murdered Congolese leader Patrice Lamumba, in Conor Cruise O’Brien’s Murderous Angels (1971). Gossett had played roles in New York-set TV series such as The Naked City, but he began to make a mark in Hollywood, despite LAPD officers having handcuffed him to a tree, on “suspicion”, in 1966.

On TV he starred in The Young Rebels (1970-71) set in the American revolution. In film, he was good as a desperate tenant in Hal Ashby’s Landlord (1970) and brilliant with James Garner in Skin Game (1971), taking part in a con trick in which Garner sells him repeatedly into slavery then helps him to escape.

In 1977, alongside Roots, he attracted attention as a memorable villain in Peter Yates’s hit The Deep, and got artistic revenge on the LAPD in Robert Aldrich’s The Choirboys. The TV movie of The Lazarus Syndrome (1979) became a series in which Gossett played a realistic hospital chief of staff set against an idealistic younger doctor. He played the black baseball star Satchel Paige in the TV movie Don’t Look Back (1981); years later he had a small part as another Negro League star, Cool Papa Bell, in The Perfect Game (2009).

After his Oscar, he played another assassinated African leader, in the TV mini-series Sadat, reportedly approved for the role by Anwar Sadat’s widow Jihan. Though he remained a busy working actor, good starring roles in major productions eluded him, as producers fell back on his drill sergeant image. He was Colonel “Chappy” Sinclair in Iron Eagle (1986) and its three dismal sequels.

But in 1989 he starred in Dick Wolf’s TV series Gideon Oliver, as an anthropology professor solving crimes in New York. And he won a best supporting actor Golden Globe for his role in the TV movie The Josephine Baker Story (1991). He revisited the stage in the film adaptation of Sam Shepard’s Curse of the Starving Class (1994).

Gossett twice received the NAACP’s Image Award, and another Emmy for producing a children’s special, In His Father’s Shoes (1997). In 2006 he founded the Eracism Foundation, providing programmes to foster “cultural diversity, historical enrichment and anti-violence initiatives”. Despite an illness eventually linked to toxic mould in his Santa Monica home, he kept working with a recurring part in Stargate SG-1 (2005-06). A diagnosis of prostate cancer in 2010 hardly slowed him down.

Most recently, he played Will “Hooded Justice” Reeves in the TV series Watchmen (2019), in the series Kingdom Business, about the gospel music industry, and in the 2023 musical remake of The Color Purple.

His first marriage, to Hattie Glascoe, in 1967, was annulled after five months; his second, to Christina Mangosing, lasted for two years from 1973; and his third, to Cyndi (Cynthia) James, from 1987 to 1992. He is survived by two sons, Satie, from his second marriage, and Sharron, from his third.

🔔 Louis Cameron Gossett Jr, actor, born 27 May 1936; died 28 March 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Little Sister of the Giants

(Brazilian folktale collected by Elsie Spicer Eells for her second anthology book, Tales of Giants from Brazil)

@themousefromfantasyland @princesssarisa @adarkrainbow

@faintingheroine @thealmightyemprex @the-blue-fairie @amalthea9 @professorlehnsherr-almashy @angelixgutz @tamisdava2 @grimoireoffolkloreandfairytales @softlytowardthesun

Once upon a time there was a little girl who was very beautiful. Her eyes were like the eyes of the gazelle; her hair hid in its soft waves the deep shadows of the night; her smile was like the sunrise. Each year as she grew older she grew also more and more beautiful. Her name was Angelita.

The little girl’s mother was dead, and her father, the image-maker, had married a second time. The step-mother was a woman who was renowned in the city for her great beauty. As her little step-daughter grew more and more lovely each day of her life she soon became jealous of the child. Each night she asked the image-maker, “Who is more beautiful, your wife or your child?”

The image-maker was a wise man and knew all too well his wife’s jealous disposition. He always responded, “You, my wife, are absolutely peerless.”

One day the image-maker suddenly died, and the step-mother and step-daughter were left alone in the world. They both mourned deeply the passing of the kind image-maker.

One day as they were leaning over the balcony two passers-by observed them, and one said to the other, “Do you notice those beautiful women in the balcony? The mother is beautiful, but the daughter is far more beautiful.” The step-mother had always been jealous of the daughter’s loveliness, but now her jealousy was fanned into a burning flame. The wise image-maker was no longer there to tell her that she was peerless.

The next day the mother and daughter again leaned over the balcony. Two soldiers passed by and one said to the other: “Do you observe those two beautiful women in the balcony? The mother is beautiful, but the daughter is far more beautiful.” The step-mother flew into a terrible rage. She now knew that it was true as she had long feared. The girl was more beautiful than she. Her jealousy knew no bounds. She seized her step-daughter roughly and shut her up in a little room in the attic.

The little room in the attic had just one tiny window high up in the wall. The window was shut, but Angelita climbed up to open it in order to get a little air. The next afternoon she grew weary of the confinement of the little room, so she dug a foothold in the wall where she could stand and look out of the window. Her step-mother was leaning over the balcony all alone when two cavalheiros passed by. One said to the other, “Do you observe the beautiful woman in the balcony?” “Yes,” replied the other. “She is a beautiful woman, but the little maid who is kept a prisoner in the attic is far more beautiful.”

The step-mother became desperate. She ordered the old negro servant to carry the girl into the jungle and kill her. “Be sure that you bring back the tip of Angelita’s tongue, so that I may know that you have obeyed my order,” she said.

Angelita was very happy to be taken out of the little attic room, and set out for a walk with the old negro with a light heart. They walked through the city streets and out into the open country. Soon they had reached the deep jungle. “Where are we going?” the girl asked in surprise.

“We are taking a walk for our health, yayazinha,” replied the old negro.

Soon they were so far in the jungle that the path was entirely overgrown. No ray of light penetrated through the deep foliage. Angelita became frightened. “I’ll not go another step if you do not tell me where you are taking me,” she said as she stamped her little foot upon the ground.

The old negro burst into tears and told Angelita all that her step-mother had commanded. “I could not hurt one hair of your lovely head, much less cut off the tip of your little tongue, yayazinha,” sobbed the old man.

Angelita stood still and thought. “Go back to my step-mother,” she said to the old man. “On the way you will see plenty of dogs. Cut off the tip of a little dog’s tongue and carry it home to my step-mother.”

This is what the old negro did. The step-mother believed him and thought that he had slain her step-daughter according to her command.

Angelita, in the meantime, wandered on and on through the jungle. The big snakes glided swiftly out of her path. The monkeys and the parrots chattered to keep her from being lonely. She wandered on and on until finally she came to an enormous palace. The front door was wide open. She went from room to room, but the palace was entirely deserted. There was not a neat, orderly room in the entire palace.

“I can make these lovely rooms neat and clean,” said Angelita. “They surely need some one to do it!” She found a broom and went to work at once. Soon the whole palace was in order once more. Everything was clean and bright.

Just as Angelita was finishing her task she heard a great noise. She looked out of the door, and there were three enormous giants entering the house. She had never dreamed that giants could be so big. She was frightened nearly to death and scrambled under a chair as fast as she could.

When the giants came into the house they were amazed to find everything in such splendid order. “This is a different looking place from what we left,” said the biggest giant.

“What dirty, disorderly giants we have been, living here all by ourselves,” said the middle-sized giant. “I just realize it, now that I see what our house looks like when it is neat and clean.”

“What kind fairy could have done all this work while we were away?” said the littlest giant, who was not little at all, but almost as big as his enormous brothers.

The three giants fell to discussing the question. They could not guess how their house could have been made so clean. Their voices were so very kind, in spite of being so loud and heavy, that Angelita decided she dare come out from under the chair and let them see who had done the work for them. She quickly crawled out from her hiding place.

“What lovely fairy is this?” asked the biggest giant, looking at her kindly. He thought that she really was a fairy.

“This is the loveliest fairy I ever saw in all my life,” said the middle-sized giant.

“How did such a lovely fairy ever happen to find our dirty, disorderly palace?” asked the littlest giant who was not little at all.

Angelita told the three giants her story. Her beauty and her sweet ways completely entranced them.

“Please live with us always here in our palace in the jungle and be our little sister,” said the biggest giant, and the middle-sized giant and the littlest giant, speaking all at once. Their three big deep voices all together made a noise like thunder.

Angelita lived in the palace with the three giants after that. Every day when they went out to hunt she would take the broom and make the palace neat and clean. They called her “little sister” and loved her with all their big giant hearts.

All was well until a little bird went and told Angelita’s step-mother that she was alive and living in the depths of the jungle with the three giants. When the step-mother heard about it she was so angry that she thought she could never be happy as long as Angelita was living in the world. She consulted a wicked witch as soon as she could find her shawl.

The wicked witch gave the step-mother some poisoned slippers. “These will cause the immediate death of any person who puts them on,” said the wicked witch. Then she showed the step-mother just how to reach the palace where Angelita lived in the depths of the jungle with the three giants.

Angelita’s step-mother followed the directions which the witch had given her and easily found the giants’ palace. Angelita was so happy living with the giants and keeping house for them that she had forgotten what fear was like. She was not frightened at all when she heard some one clap hands before the door one day when the giants were away. She went to the door; and, though she was very much surprised to see her step-mother, she invited her into the house. Her step-mother gave her a loving embrace and kissed her upon both cheeks. “Dear child, it is a long time since I have seen you,” she said. “I have brought you a little gift to show you that I have not forgotten you. It is only a poor, mean little gift, but it is the best I could bring.”

Angelita was touched at her step-mother’s gift and accepted it with hearty thanks. As soon as her step-mother had gone she untied the red ribbon around the package and opened it. Inside was a pair of leather slippers. Angelita looked at the little slippers. They were like the slippers which her dear father, the image-maker, had once brought home to her. “How kind it was in my step-mother to bring these slippers to me,” she said as she put them on.

As soon as the slippers were on Angelita’s feet, she fell dead just as the wicked witch had promised the step-mother she would do. Her step-mother was watching through the window, and when she saw Angelita dead she hurried home in joy. “Now I, alone, am the peerless beauty,” she said.

When the three giants came home to dinner they knew at once that there was something wrong. There were dirty tracks on the floor and dirty finger prints upon the door. “Who made these dirty marks?” said the biggest giant.

“What has happened to our dear little sister that she has not cleaned them away?” asked the middle-sized giant.

“I am afraid there is something wrong with little sister,” said the littlest giant who was not little at all.

They clapped their big hands before the door, but no smiling little sister ran to meet them. They entered the big hall of the palace with a bound. There in the middle of the floor lay Angelita, just as she had fallen when she put on the poisoned slippers which her step-mother had given her.

“What evil, has befallen our dear little sister?” said the biggest giant.

“Who could have slain our little sister whom we loved so much?” said the middle-sized giant.

“Who will keep house for us now that our dear little sister is dead?” asked the littlest giant.

Then the biggest giant and the middle-sized giant and the littlest giant all began to sob so loud that it shook the earth. “Our dear little sister is dead! What shall we do! What shall we do!”

The giants could not go into the city to give their little sister Christian burial, but they built a beautiful casket out of silver and carried it to the path which led to the city. Then they hid themselves to watch and make sure that some one found it to carry to the burying place.

Soon a handsome prince passed by on horseback. He noticed the silver casket at once and opened it. The girl whose still form lay inside was the most beautiful maid he had ever gazed upon. “This dead maid is my own true love,” he said and he carried the silver casket home to his own palace.

He commanded that no one should enter the room where he placed the silver casket, and this aroused the curiosity of his little sister at once. At the very first opportunity she slipped into the room. She opened the casket and was surprised to see the beautiful quiet maid. “You are very lovely,” she said to the still form, “all except your slippers. I think they are very ugly.” With these words she pulled off the leather slippers.

Angelita gave a deep sigh, opened her beautiful eyes, and asked for a drink of water.

The little sister called the prince at once. When he saw Angelita was really alive he could hardly believe the good fortune. He asked that the wedding night be celebrated immediately.

Angelita begged that she might go back into the deep jungle and invite the three giants to the wedding. The biggest giant, the middle-sized giant, and the littlest giant who was not little at all, came to the wedding feast. After that they visited their little sister often at her new home; and, when she had children of her own, it was the funniest sight one ever saw to see the biggest giant hold the tiny babes upon his knee.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

OUT THERE SCREAMING edited by JORDAN PEELE (REVIEW)

quickly: the ‘horrors’ of blackness have its natural and supernatural roots revealed (bad cop with a third eye / grandma’s love is deadly / wandering man running from nothing / in vivo alien invasion / unstable ex’s / sea siren with your sister’s face / dead man’s swamp revenge / serial killer targeting black robots / white men ruining the atmosphere / daddy’s secret / chaos in the dark / part woman part fish-devil / black magic as an HOA / grief and its blindness / games that ghosts play / negro folk tales as an american requiem / prison industrial complex goes A.I. / black magic as an addiction / whiteness as psyche and psychosis)

A fantastically original collection of short horror stories that span quite a range of horror sub-genres (sci-fi, thriller, romance, and even americana). All unapologetically Black. A superb addition to the limited number of Black horror anthologies (Tales from the Hood, anyone?).

My favorites were Wandering Devil (loverboy with wandering feet can outrun everyone but himself), The Rider (a dead man intervenes on behalf of two black women traveling alone), Flicker (an intermittent darkness unleashes chaos from the shadows), The Norwood Trouble (a group of black ‘practitioners’ will be damned if white rioters try to destroy their town), A Grief of The Dead (grief separates and reunites a pair of twin brothers), Your Happy Place (an incarcerated man must decide his reality after having it stolen from him), Hide & Seek (brothers learn to protect themselves with the same magic that wants to harm them).

★★★★★ Superb.

#out there screaming#jordan peele#5 stars#john joseph adams#anthology#horror#books & libraries#currently reading#booklover#booklr#booksbooksbooks#fiction#literature#book review#suspense#mystery#thriller#crime thriller#sci fi thriller#psychological thriller

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Arthur Baldwin (August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) was a novelist, playwright, and activist. His essays, as collected in Notes of a Native Son, explore intricacies of racial, sexual, and class distinctions in Western societies, most notably in mid-20th-century North America. Some of his essays are book-length, including The Fire Next Time, No Name in the Street, and The Devil Finds Work. An unfinished manuscript, Remember This House, was expanded and adapted for cinema as the Academy Award-nominated documentary film I Am Not Your Negro. One of his novels, If Beale Street Could Talk, was adapted into an Academy Award-winning dramatic film.

His novels and plays fictionalize fundamental personal questions and dilemmas amid complex social and psychological pressures thwarting the equitable integration of not only African Americans but Gay and bisexual men while depicting some internalized obstacles to such individuals’ quests for acceptance. Such dynamics are prominent in his second novel, Giovanni’s Room, well before the Gay Liberation Movement.

His influence on other writers has been profound: Toni Morrison edited the Library of America’s first two volumes of his fiction and essays: Early Novels & Stories and Collected Essays. A third volume, Later Novels, was edited by Darryl Pinckney, who had delivered a talk on him in February 2013 to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of The New York Review of Books, during which he stated: “No other Black writer I’d read was as literary as Baldwin in his early essays, not even Ralph Ellison. There is something wild in the beauty of Baldwin’s sentences and the cool of his tone, something improbable, too, this meeting of Henry James, the Bible, and Harlem.”

One of his richest short stories, “Sonny’s Blues,” appears in many anthologies of short fiction used in introductory college literature classes. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I put together some resources including videos, news articles, and books. These are not strictly confined to Arab/SWANA/Muslim studies but several of the issues discussed still directly affect these communities. Hoping that the below resources will prove valuable to others.

youtube

Arabs and Muslims in the Media: Race and Representation after 9/11

Arabs and Muslims in the Media after 9/11: Representational Strategies for a “Postrace” Era

Broken: The Failed Promise of Muslim Inclusion - By Evelyn Aulsultany

Orientalism - Edward Said

Terrorist Assemblages - Homonationalism in Queer Times - Jasbir K. Puar

A people's History of the United States

Arab Women Writers - an Anthology of Short Stories

Arab Women's lives retold - Exploring Identity through writing

Covering Islam - Edward Said

Culture and Imperialism - Edward Said

Asian American Feminisms and Women of Color Politics

I, Rigoberta Menchú An Indian Woman in Guatemala

The Wretched of the Earth - Frantz Fanon

Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo powers our lives - Siddharth Kara

Dancing in the Glory of Monsters - The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa

A history of Disability - Henri-Jacques Stiker

Black Disability Politics - Sami Schalk

Black on Both Sides - A racial History of Trans Identity - Riley Snorton

Black Trans Feminism - Marquis Bey

Black Women in White - Racial Conflict and Cooperation in the Nursing Profession

Crip Theory - Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability

Deaf in Japan - Signing and the politics of Identity - Karen Nakamura

Fearing the Black Body - The Racial Origins of Fatphobia - Sabrina Strings

The Female Malady: Women, Madness, and English Culture - https://archive.org/details/femalemalady00elai

It was Vulgar and It was Beautiful - How AIDS Activists used Art to Fight a Pandemic

Killing the Black Body - Race, Reproduction and the Meaning of Liberty - Dorothy Roberts

Mad in America - Bad Science, Bad Medicine, and the Enduring Mistreatment of the mentally ill

Madness and Civilization - A history of Insanity in the Age of Reason

Maladies of Empire - How Colonialism, Slavery and War Transformed Medicine

Medical Apartheid - The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans

The Delectable Negro - Vincent Woodard

The Protest Psychosis - How Schizophrenia became a Black Disease

There's Something in the Water - Environmental Racism in Indigenous Black communities

Violence Against Black Bodies - an Intersectional analysis of how Black lives continue to matter

Violence against queer People - Race, class, gender and the persistance of Anti-LGBT discrimination

The Right to Maim - Debility, Capacity, Disability Jasbir Puar

Palestine Speaks: Narratives of Life Under Occupation

Palestine - A socialist Introduction

Light in Gaza: Writings Born of Fire

Born Palestinian, Born Black - the Gaza Suite

BDS Boycott - Divestment, Sanctions, and the Global Struggle for Palestinian Rights

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books Read In 2023

Beowulf: A New Translation by Maria Dahvana Headley (1/3/23)

East by Edith Pattou (1/4/23)

Midnight on the Moon by Mary Pope Osbourn (1/16/23)

The Lady or The Tiger?, and The Discourager of Hesitancy by Frank R. Stockton (1/17/23)

The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1/21/23)

Goblin Market by Christina Rossetti (1/22/23)

Tiger Queen by Annie Sullivan (1/22/23)

The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe by C. S. Lewis (1/26/23)

Batgirl, vol. 1: The Silent Knight (1/27/23)

Batgirl, vol. 2: To The Death (1/27/23)

Batgirl, vol. 3: Point Blank (1/28/23)

The Female of the Species by Rudyard Kipling (2/17/23)

Batgirl: Stephanie Brown, vol. 1 by Bryan Q. Miller (2/19/23)

Batgirl, Stephanie Brown, vol. 2 by Bryan Q. Miller (3/4/23)

Christmas in Noisy Village by Astrid Lindgren (3/4/23)

The Queen’s Blade by T C Southwell (3/5/23)

Sacrifice, The Queen’s Blade #2 by T C Southwell (3/9/23)

The Invisible Assassin, The Queen’s Blade #3 by T C Southwell (3/13/23)

Mermaids by Patty Dann (3/14/23) X

The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám translated by Edward FitzGerald (3/19/23)

The Mirror Visitor by Christelle Dabos (3/21/23) X

The Missing of Clairedelune by Christelle Dabos (3/22/23) X

I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jeannette McCurdy (3/24/23) X

Ronia, The Robber’s Daughter by Astrid Lindgren (3/27/23)

Kiki’s Delivery Service by Eiko Kadono (3/30/23)

Brine and Bone by Kate Stradling (4/10/23)

Green Arrow: Quiver by Kevin Smith (4/17/23) X

Eugene Onegin by Alexander Pushkin, translated by Stanley Mitchell (4/22/23)

When Patty Went to College by Jean Webster (4/23/23)

The Princess and The Pea by Hans Christian Anderson (4/23/23)

Deathmark by Kate Stradling (4/25/23)

Without Blood by Alessandro Baricco (5/5/23)

River Secrets by Shannon Hale (5/6/23)

The Fairy’s Return and Other Princess Tales by Gail Carson Levine (5/8/22)

Batman Adventures: Cat Got Your Tongue? by Steve Vance (5/14/23)

Batman Adventures: Batgirl — A League of Her Own by Paul Dini (5/17/23)

The Girl From The Other Side: Siúil a Rún, Vol. 1 by Nagabe (5/19/23)

Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair by Pablo Neruda. Translated by W. S. Merwin (5/26/23)

Other-Wordly: Words Both Strange and Lovely from Around the World by Yee-Lum Mak (6/21/23)

A Bride’s Story, vol. 1 by Kaoru Mori (6/25/23) X

La Dame aux Camélias by Alexandre Dumas fils (7/17/2023)

Storefront Church by William Waring Cuney (7/24/23)

Golden Slippers: An Anthology of Negro Poetry for Young Readers (1941), compiled by Arnas Bontemps (7/28/23)

Because of Winn-Dixie by Kate DiCamillo (7/29/23)

Strawberry’s New Friend (Flower Fairy Friends series) by Pippa Le Quesne (7/29/23)

Clementine by Sara Pennypacker (8/11/23)

The Whipping Boy by Sid Fleischman (8/18/23)

Convent Boarding School by Virginia Arville Kenny (9/05/23)

The Screwtape Letters by C. S. Lewis (09/18/23)

The Betsy Tacy Treasury by Maud Hart Lovelace (09/27/23)

Sarah, Plain and Tall by Patricia MacLachlan (09/27/23)

Skylark (Sarah, Plain and Tall #2) by Patricia MacLachlan (09/27/23)

Caleb’s Story (Sarah, Plain and Tall #3) by Patricia MacLachlan (09/27/23)

Maelyn by Anita Halle (10/06/23)

Imani All Mine by Connie Porter (10/15/23)

The Perilous Gard (10/22/23)

Enemy Brothers by Constance Savery (10/29/23)

Sadako and the 1000 Paper Cranes by Eleanor Coerr (11/19/23)

Gone By Nightfall by Dee Garretson (12/02/23)

The Dragon’s Promise by Elizabeth Lim (12/08/23)

A Lion to Guard Us by Clyde Robert Bulla (12/10/23)

The Thirteenth Princess by Diane Zahler (12/23/23)

The Hollow Kingdom by Clare B. Dunkle (12/26/23

The Wasteland by T. S. Eliot (12/31/23)

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

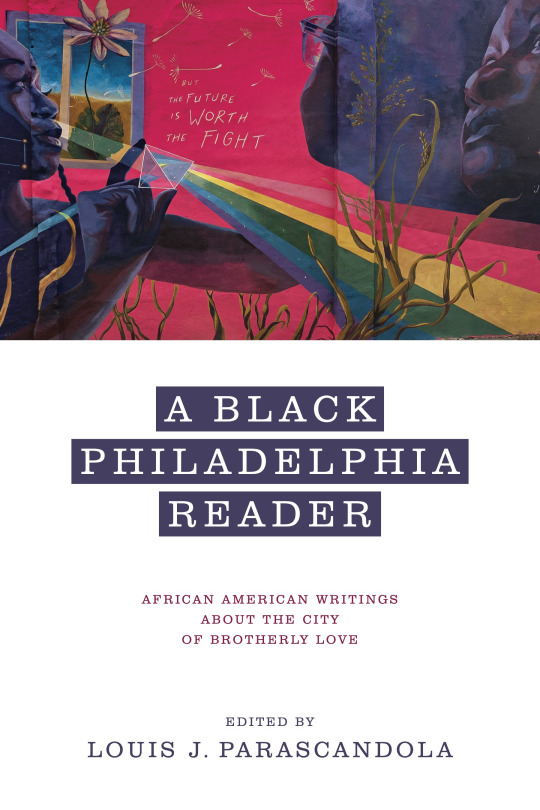

A Black Philadelphia Reader: An exerpt

The common date given for the settlement of Philadelphia is 1682, when William Penn established a Quaker colony, providing it with a name that means “one who loves his brother.” Penn intended an idyllic “greene country towne,” one that was well ordered, with large open spaces within its twelve hundred acres. It “was the first major American town to be planned.” Penn envisioned his “towne” as a place of freedom, particularly in terms of religion. As with a certain amount of history, much of this is myth. The land, of course, had been settled by the Lenape Indians long before the Europeans arrived. Additionally, Penn’s “greene country towne” soon became a highly congested city, plagued by disease, crime, and fires. Its vaunted freedom was largely limited to White Protestants, and its “brotherly love” certainly did not extend to most immigrants, to non-Christians, or, in particular, to its Black residents.

Blacks have been at the center of Philadelphia’s history since before it was even known by that name. More than two thousand Blacks lived in the area once called New Sweden between 1638 and 1655. The fledgling colony encompassed parts of western Delaware and parts of Pennsylvania that now include Philadelphia. One of the most famous of these settlers was Antoni Swart (Black Anthony), a West Indian who arrived in the colony in 1639 aboard a Swedish vessel. Though initially enslaved, records indicate he eventually became free and was employed by Governor Johan Printz.

The history of Black Philadelphians has been one fraught with both great promise and shattered dreams from its beginnings until today. Philadelphia was, as historian Gary Nash observes, “created in an atmosphere of growing Negrophobia”; still, despite ongoing racial prejudice, “it continues to this day to be one of the vital urban locations of black Americans.” It is this paradoxical condition that is the most characteristic dynamic of the city’s relationship with its Black citizens. One facet of this relationship has been constant: whether African Americans have thrived here or suffered egregious oppression, they have never remained silent, never letting anyone else define their situation for them. They have always voiced their own opinions about their condition in their city through fiction, poetry, plays, essays, diaries, letters, or memoirs. The city has been blessed with a number of significant authors, ranging, among others, from Richard Allen to W. E. B. Du Bois to Jessie Fauset to Sonia Sanchez to John Edgar Wideman to Lorene Cary. In addition, there have been numerous lesser known but also forceful figures as well, including the enslaved people Alice and Cato, who were only known by those names. Whether they were native sons and daughters or spent significant time in the city or were there only long enough to experience the city in an impactful moment, Philadelphia has touched them all deeply. This anthology is a documentation of and a tribute to their collective voice. The focus here is not just on writers with a Philadelphia connection but on the authors’ views on the city itself. The hope is to provide a wide variety of Black perspectives on the city.

There is something special about what leading African American intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois once labeled “the Philadelphia Negro.” One reason for this uniqueness is the city’s relationship to its Black inhabitants, in part caused by their intertwined, virtually symbiotic, history. No other major Northern city in the country has had such a long connection with African Americans, one forged in the seventeenth century, and Blacks have never stopped coming. They first settled largely in what are now called the Old City and Center City, where some Blacks still live. They have since scattered throughout the city, sometimes by choice but often by necessity and force, today mostly residing in Northern and Western Philadelphia. Migration patterns have changed over the years, as in other cities, but the Black population in the city has rarely declined and has often increased in number. Philadelphia was, as of 2020, the sixth-largest metropolis in the nation, and Blacks make up more than 40 percent of the population there, more than the percentage of any of the other top ten cities in the country.

Philadelphia has a vibrant and culturally rich history, offering enormous promise to its inhabitants since its beginnings. It was founded with the premise of religious freedom and steeped in the radical independence movement that created this country. The city was settled by Quakers, perhaps the religious group that, in popular opinion if not always in fact, has most vociferously been associated with opposition to slavery. The “peculiar institution” was, in fact, almost nonexistent there by the early years of the nineteenth century. Philadelphia was the center of the Underground Railroad, with such legendary conductors as William Still. As the closest major city situated above the Mason-Dixon line, symbolically separating the North from the South, many fugitives from enslavement passed through Philadelphia. Some moved on, but a large number stayed, as the city seemed like the promised land for many African Americans. This is the powerful narrative of the city’s history that still holds true for numerous people today when they think of Philadelphia.

There is also something unique about the Black experience in this city. Blacks have had a nominal freedom throughout most of their existence in Philadelphia, yet when we look under the surface, Philadelphia’s treatment of African Americans has hardly been benign. The city has held out promises, but unfortunately many of these promises were not kept. Philadelphia may be situated in the North, but as Sonia Sanchez so eloquently writes in her poem “elegy (For MOVE and Philadelphia),” in many ways “philadelphia / [is] a disguised southern city.” There were Quakers, many of whom were abolitionists and worked for the Underground Railroad, but there were many others of the faith who were slaveholders, including the colony’s founder, William Penn. And even if the city was replete with abolitionists, it did not ensure that they viewed African Americans as equals. Blacks were, in fact, disfranchised from the vote in 1838, never to regain it until the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870. Although the city was the center of the antislavery movement, not all of its White residents opposed slavery, and even if they did, the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850 hampered efforts to keep Blacks out of bondage. Before and after the Civil War, as demonstrated throughout this text, the city experienced a series of violent racial conflicts and has continue to practice an ugly pattern of segregation in housing, transportation, education, and employment, severely limiting the prospects of improvement for its Black citizens. There is a long history of racial injustice practiced by Philadelphia’s police as well as Black residents being ignored, at best, by the city government.

A Black Philadelphia Reader: African American Writings About the City of Brotherly Love is available for pre-order from Penn State University Press. Learn more and order the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-09731-2.html. Take 30% off with discount code NR24.

#Philadelphia#Philly#Pennsylvania#African American#African American History#PA History#Pennsylvania History#City of Brotherly Love#Black Writers#Black Authors#Black Writer#Black Author#W. E. B. Du Bois#Harriet Jacobs#Sonia Sanchez#John Edgar Wideman#Public Health#Housing#Policing#Criminal Justice#Public Transportation#Urban Studies

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The New Negro: An Interpretation, edited by Alain Locke, cover by Winold Reiss, 1925.

The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925) was an anthology of fiction, poetry, and essays on African and African-American art and literature. It was edited by Alain Locke, the first African-American Rhodes Scholar, who obtained a Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard and who taught at Howard University for 35 years. The book is considered by literary scholars and critics to be the definitive text of the Harlem Renaissance. It included Locke's title essay, "The New Negro," as well as nonfiction essays, poetry, and fiction by Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, and Eric Walrond, among others. The anthology showed how Blacks sought social, political, and artistic change. Instead of accepting their position in society, Locke saw the "New Negro" as championing and demanding civil rights. His anthology also sought to change old stereotypes and replace them with new visions of Black identity that resisted simplification. The essays and poems in the anthology mirrored real-life events and experiences.

Photo: winoldreiss.org

#vintage New York#vintage Harlem#Harlem Renaissance#1920s#Alain Locke#The New Negro#Winold Reiss#civil rights#African-American literature#Black literature#books#social change

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

#PBSwednesday Hollywood Television Theatre, an anthology series produced by KCET in Los Angeles, aired between 1970 and 1978. "Day of Absence" (1971), a reverse minstrel show played in white-face by members of the Negro Ensemble Company, concerned a small Southern town where the black population disappears overnight and the resulting chaos. The 1971-72 season offered 18 plays. By the final seasons, production had dwindled to only three or four.

Special Collections in Mass Media and Culture | Tumblr Archive

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today We Honor Alain LeRoy Locke

Alain LeRoy Locke is heralded as the “Father of the Harlem Renaissance” for his publication in 1925 of The New Negro—an anthology of poetry, essays, plays, music and portraiture by white and black artists.

Locke is best known as a theorist, critic, and interpreter of African-American literature and art. He was also a creative and systematic philosopher who developed theories of value, pluralism and cultural relativism that informed and were reinforced by his work on aesthetics.

CARTER™️ Magazine carter-mag.com #wherehistoryandhiphopmeet #historyandhiphop365 #cartermagazine #carter #staywoke #alainlocke #blackhistory #blackhistorymonth #history

#carter magazine#carter#historyandhiphop365#wherehistoryandhiphopmeet#history#cartermagazine#today in history#staywoke#blackhistory#blackhistorymonth

41 notes

·

View notes

Link

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

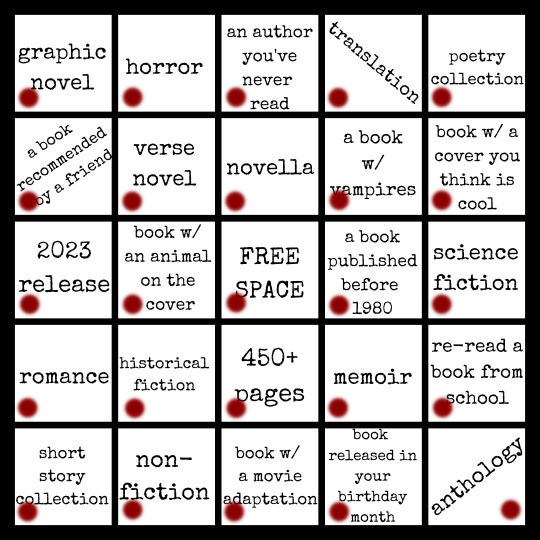

Once again I aimed for complete blackouts on @batmanisagatewaydrug's and @macrolit's reading bingos and this time, I actually succeded! (Even if I took some liberties with the term 'novel' on the macrolit one, mostly focused on the 'classics' aspect.) Lowkey proud of myself ngl.

Titles for both under the cut, full reading list here.

batmanisagatewaydrug:

graphic novel: Christopher Tauber, Hanna Wenzel: Rocky Beach. Eine Interpretation. [no english title]

horror: Jáchym Topol: Die Teufelswerkstatt [org. title: Chladnou zemí/engl. title: The Devil’s Workshop]

author you’ve never read before: David Henry Hwang: M Butterfly

translation: Władysław Szlengel: Was ich den Toten las [org. title: Co czytałem umarłym/engl. title: What I Read to the Dead]

poetry collection: Richard Siken: Crush

a book recommended by a friend: James Oswald: Natural Causes. An Inspector McLean Novel.

verse novel: Alexander F. Spreng: Der Fluch [no english title]

novella: Thomas Mann: Der Tod in Venedig [engl. title: Death in Venice]

a book w/ vampires: Michael Scott: The Secrets of the Immortal Nicholas Flamel #2. The Magician.

book w/ a cover you think is cool: Cornelia Funke: Tintenwelt #4. Die Farbe der Rache. [engl. title: The Color of Revenge]

2023 release: Jonathan Kellerman: Unnatural History. An Alex Delaware Novel

book w/ an animal on the cover: Faye Kellerman: Der Zorn sei dein Ende [org. title: The Hunt]

book published before 1980: Josef Bor: Die verlassene Puppe [org. title: Opuštěná panenka/engl. title: The Abandoned Doll]

science fiction: Ursula K. Le Guin: The Dispossessed

romance: Akwaeke Emezi: You made a Fool of Death with your Beauty

historical fiction: Alena Mornštajnová: Hana [org. title: Hana/engl. title: Hannah]

450+ pages: James Ellroy: Die Schwarze Dahlie [org. title: The Black Dahlia]

memoir: Jeanette McCurdy: I‘m Glad My Mom Died

re-read a book from school: Frank Wedekind: Frühlings Erwachen [engl. title: Spring Awakening]

short story collection: John Barth: Lost in the Funhouse

non-fiction: Vera Schiff: The Theresienstadt Deception. The Concentration Camp the Nazis Created to Deceive the World.

book w/ a movie adaption: Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita

book published in your birthday month: Jan T. Gross: Neighbors. The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland.

anthology: Alain Locke: The New Negro

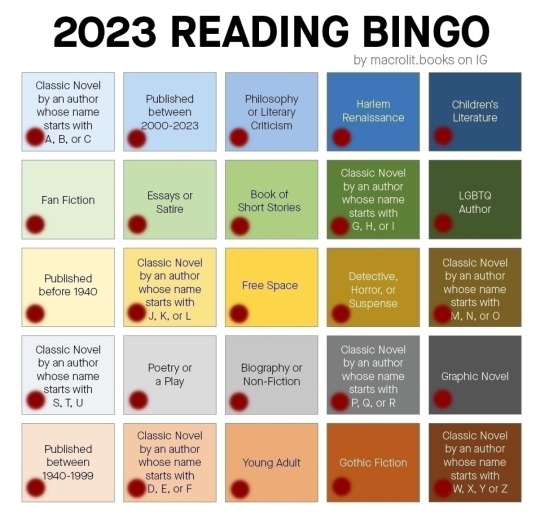

macrolit:

Classic Author A/B/C: James Baldwin: Giovanni‘s Room

Published between 2000-2023: Kim Newman: Professor Moriarty. The Hound of the D‘Urbervilles

Philosophy or Literary Criticism: [various books and essays for three literature courses]

Harlem Renaissance: Claude McKay: Harlem Shadows

Children’s Literature: [various Three Investigators books]

Fan Fiction: [various works]

Essays or Satire: Mark Thompson: Leatherfolk. Radical Sex, People, Politics and Practice.

Book of Short Stories: John Barth: Lost in the Funhouse

Classic Author G/H/I: Lorraine Vivian Hansberry: A Raisin in the Sun

LGBTQ+ Author: Ocean Vuong: Time is a Mother

Published before 1940: Friedrich Schiller: Maria Stuart

Classic Author J/K/L: Ursula K. Le Guin: The Dispossessed

Detective, Horror, or Suspense: Maurice Leblanc: Arsène Lupin und der Schatz der Könige von Frankreich [org. title: L'Aiguille creuse/engl. title: The Hollow Needle]

Classic Author M/N/O: Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita

Classic Author S/T/U: J.D. Salinger: The Catcher in the Rye

Poetry or Play: Arthur Schnitzler: Reigen [engl. title: La Ronde]

Biography or Non-Fiction: Peter Hallama: Nationale Helden und jüdische Opfer. Tschechische Repräsentationen des Holocaust. [no english title]

Classic Author P/Q/R: Sylvia Plath: The Bell Jar

Graphic Novel: Christopher Tauber, Hanna Wenzel: Rocky Beach. Eine Interpretation. [no english title]

Published between 1940-1999: Hanna Krall: Dem Herrgott Zuvorkommen [org. title: Zdążyć przed Panem Bogiem/engl. title: Shielding the Flame]

Classic Author D/E/F: Bret Easton Ellis: American Psycho

Young Adult: Kathy Reichs: Virals #1. Tote können nicht mehr reden. [org. title: Virals]

Gothic Fiction: E.T.A. Hoffmann: Nussknacker und Mausekönig [engl. title: The Nutcracker and the Mouse King]

Classic Author V/W/X/Y/Z: Frank Wedekind: Frühlings Erwachen [engl. title: Spring Awakening]

#end of 2023#reading list#2023 reading bingo#had a lot of fun with these#actually fit my reading goals pretty much perfectly#challenged my just enough to have to actively broaden my horizon#almost drew a blank on the verse novel but then asp finally released his reading of der fluch and of course i read along while listening#also had to get pointers for the romance and it was sooooooo worth stepping out of my comfort zone

4 notes

·

View notes