#Pindar

Text

Fragments of perfection | Elysian Fields

#art#collage#core#emo#goth#drain gang#weirdcore#webcore#wound#ethel cain#utopia#eutopia#elysia#pindar#fragments#odin#poetry#prose

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

For neither the blaze-colored fox nor mighty-roaring lions change their inborn character.

τὸ γὰρ \ ἐμφυὲς οὔτ᾽ αἴθων ἀλώπηξ \

οὔτ᾽ ἐρίβρομοι λέοντες διαλλάξαντο ἦθος.

-Pindar, Olympian Ode 11.19-21

#quote#quotes#classics#tagamemnon#Greek#Greek language#Ancient Greek#Ancient Greek language#translation#Greek translation#Ancient Greek translation#poetry#lyric poetry#Greek poetry#Ancient Greek poetry#Pindar#victory ode#Ancient Greece#Classical Greece

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

The myth of Apollo (2)

This is a loose translation of Alain Moreau's article "The Antique Apollo: Shadow and Light".

II/ The ambiguous god

The mystery that shrouds Apollo’s origins, this enigma that disconcerts the scholars, had the advantage to allow the artists a freedom of imagination: since the shape of the primitive character of the god is drowned and blurred, he can be depicted as either a god of light, or a god of shadow and death; However, even within the most clear-cut portraits, his complexity remains. Apollo is never a god entirely just and good ; but he is never fully aligned with malevolent powers.

According to the beginning of the Iliad, Homer chose to depict the dreaded aspect of the go. Apollo, angered against Agamemnon’s army, hits them with a terrible disaster, (nousos, loimos), the plague: “A terrible sound came out of the silver bow. He first attacked the horses, like fast dogs. Then, it is men that are hit by his sharp arrow, and the funeral pyres burn hundreds ceaselessly.” Fervent enemy of the Greeks, it is Apollo that throws against the Achaean wall all the rivers of the Mount Ida ; it is also him that hits Patroclus in the back and offers him unarmed to the spear of Hector. And yet, this terrible god is also the one that brings a painless death, and then the cruel arrows become the “soft arrows”. He is hostile to the Achaeans, but he brings a tireless protection to the Trojans. Aeneas, Glaucos, Hector are all helped by him. He constantly assists them, recomforts them, stimulates them, saves them. If his shot brings death, it can also repel evil. Apollo is “the one that preserves” (hekaergos). Throughout the centuries, many epiclesis will attest this trait: alexikakos, apotropaios, epikourios…

In a reverse way, the “Homeric Hymn”, which is all about the glory of this conquering god who is eternally young and beautiful, oes not hide his “boundless pride”, and he is shown easily tricked. Young Apollo does not have the same temperance and moderation that will become the fundamentals of the Delphi wisdom, engraved on his very temple (“Know thyself”, “Never too much”) ; and young Apollo also lacks the omniscience of his father Zeus.

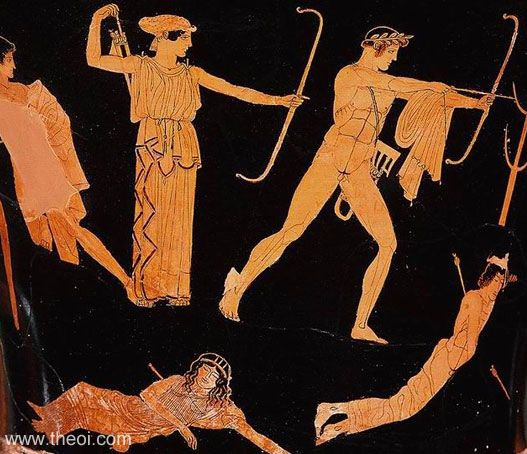

But with Pindar, at the beginning of the Classical age (5th century), he gains omniscience: in the “Pythics” he is described as “knowing the fatal term of all things and all the paths they take”, as “being able to count the leaves the earth grows during spring, and the grains of sand that roll under the waves of the sea or the river, and the flows of the wind” ; and as “you who sees clearly the future and its origin”… As a generous god, he also offers to humanity benevolent gifts, and maintains peace: “It is him that gives to men and to women the remedies that heal cruel diseases ; he gave us the cithara ; the Muse inspires those that please him ; he places in the hearts the love for concord and the horror of civil war. He rules the prophetic sanctuary.” As a son of Zeus, he himself becomes the embodiment of the divine, of the unnamed, of the celebrated “theos”. But Pindar didn’t go as far as to erase the other Apollo, the cruel god of destruction. Apollo takes his revenge over an unfaithful Coronis by sending Artemis, a merciless and blind executioner, to kill her with a brutal death – and so will perish numerous innocents whose sole crime was to live near the culprit.

Aeschylus’ Apollo, contemporary to the one of Pindar, brings a halt to the evolution of the god – and even a regression. In his tragedies, we have a bloodthirsty god that massacres with his arrows all of Niobe’s sons: his wrath is unflinching. Laios disobeyed the oracle: at the seventh door, the god will cause the fratricide of his grandsons Eteocle and Polynice (The Seven Against Thebes). Cassandra did not keep her promise: she will be mocked, captured and murdered. But the god, just like the perjury girl, does not hold his promises: after predicting to Thetis that all the gods will protect her bloodline with all of their love, he kills her son Achilles (The Judgement of Weapons). He is a god that scares people: “Phoibos” is close to “phobos”, fear and scare (The Persians). “Apollon” is close to “apollôn”, “he who destroys” (Agamemnon). The justice Apollo offers is an archaic justice, a vendetta logic: kill the one that killed. When he fights the Erynies within the play “The Eumenids”, he is not above them in any way: they have the same violence, the same bad faith, the same contradictions. And yet… this god is invoked by the messenger of Argos as the savior and the healer (Agamemnon). This imperfect god is the ambassador of Zeus, as it is highlighted many times during “The Eumenids”. This conquering god settles with pacifism on the ancient throne of Delphi: within “The Eumenids”, no murder of any dragon is mentioned. The god of darkness keeps some traits from the god of light.

The regression of Apollo within Aeschylus’ plays is explained by the turmoil of a world that was building: the Greek city was being born among a set of social and political tensions that impacted the way the thinkers saw the cosmos. Euripides’ own regression of Apollo can be explained by a world that is falling apart. The cities are fighting with each other, beliefs are weakening, the gods are falling from their pedestal and are lowered to the same level as mankind. It is the Dioscuri that absolve Orestes of the death of Clytemnestra. And the culprit of the crime is designated as Apollo, which gave “an unwise order” (Electra). A god full of grudges, he never forgives any offense. It is within his own sanctuary, in a treacherous way, by the arms of a thousand men, that he takes his revenge upon Pyrrhus, right as the latter was coming to make amends: “Here is how the Lord that gives oracles, the arbitrator of the law for all humankind, treats the son of Achilles as he was offering reparation! Just like a wicked man, he remembered old feuds. How could he then be wise?” (Andromache). Another proof of his lack of wisdom: he rapes Creusa. “Ah! Do not act in such a way ; if you have the power, practice the virtue! Because anyone who is wicked is punished by the gods. Then, how can we stand that yourselves, that make laws for the humans, be recognized of violating those laws? (Ion).

And yet, the Apollo of Euripides can also be as shining as the god of Pindar and of the Homeric Hymn: “How beautiful are the children of Leto, that she of Delos birthed in the fecund vales of the Isle – the golden-haired god, knowledgeable lyre-player, and the goddess proud in her talent at shooting with a bow!” (Iphigenia in Taurid). The bloodthirsty god can preach for peace: “Go you way, and may the most beautiful goddess, Peace, be in your home with honor.” (Orestes). And, while the poet is very critical of the god’s actions during “Ion”, he still sings the luminous and cosmic beauty of Delphi which, according to him, would have never been as great as it is if it wasn’t for the grace of its god: “Here is the brilliant four-horse chariot: Helios, already, sheds light upon the earth. And the stars flee the ether that is enflamed among the sacred night. The untouched peaks of the Parnassus, drowned in light, welcome for mankind the disc of the day.”

The ambiguity of the god, tied to his origins, is maintained as much within the works of those that criticized him, as in the texts of those that admired and respected him.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel like Sappho is probably going to come out on top here but I'm curious what everyone's Poetry Hot Takes are

#poetry#lyric poetry#classics#tagamemnon#alcman#sappho#alcaeus#anacreon#stesichorus#ibycus#simonides#baccylides#pindar#greek poetry#poll

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

σύμβολον δ’ οὔ πώ τις ἐπιχθονίων

πιστὸν ἀμφὶ πράξιος ἐσσομένας εὗρεν θεόθεν,

τῶν δὲ μελλόντων τετύφλωνται φραδαί

Pindar

No mortal has ever discovered a faithful sign of things to come from the gods: we are blind to the future.

Photo: Statues in the Tuileries gardens in Paris being protected from German air raids, 1940.

#pindar#greek#classical#quote#statues#foresight#signs#paris#second world war#arts#sculptures#war#tuileries gardens#future#culture

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

#the myth of sisyphus#pindar#albert camus#writing#literature#soul#quotes#english#poetry#poems and poetry

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

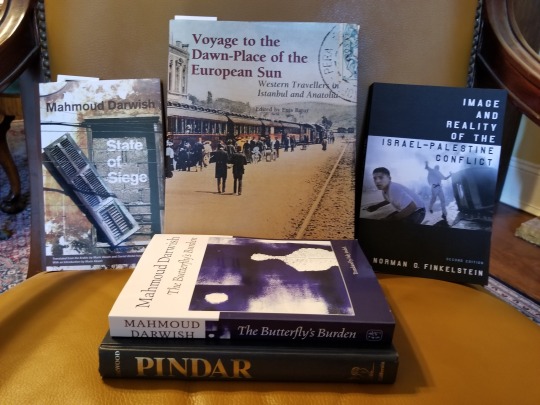

My favorite bookshop contacted me about two books of poetry by Mahmoud Darwish which I was interested in. So, today it was off to the French Quarter. Obviously I came home with more than just the two Darwish books. I hope that I live long enough to read these and others in my library.

#books#bookstores#bookworm#poetry#mahmoud darwish#pindar#norman finkelstein#istanbul#travellers#anatolia#palestine#israel

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Let us look one another in the face. We are Hyperboreans — we know well enough how much out of the way we live. ‘Neither by land nor sea shalt thou find the road to the Hyperboreans’: Pindar already knew that of us".

- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Antichrist.

#Friedrich Nietzsche#the antichrist#thus spoke zarathustra#beyond good and evil#the gay science#eternal return#carl Jung#julius evola#europe#european philosophy#philoshophy#ortega y gasset#traditionalism#european thought#nouvelle droite#alain de Benoist#hyperborea#hyperboreans#pindar#north wind

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herodotus' Proem and ancient Greek epinician poetry

"Thus the numerous points of contact between Sappho 16 and the prologue of the Histories suggest that, in addition to underscoring points of significant contrast with Homeric epic, Herodotus’ rhetorical strategy may also have evoked an especially well known poetic priamel, imitating its form while contesting its argument. Looking beyond Sappho, finally, I would like to propose that epinician poetry also contributes important elements to the intertextual background against which Herodotus’ original audience may have understood Histories 1.1-5. Here I refer to both the use of the priamel in epinician and to the portrayal of Croesus in that genre. Bundy has described the priamel as manifesting ‘perhaps the most important structural principle known to choral poetry, in particular to those forms devoted to praise’.81 Race has described Pindar, the most accomplished of the Greek epinician poets, as ‘the indisputed master of the priamel’.82 Now a common function of the priamel in epinician is to intensify praise of the laudandus and his achievements—as seen, for example, in the pair of priamels that frame Pindar’s Olympian 1. The first of these (lines 1-7) addresses what is ‘best’ (ἄριστον, 1) in various spheres, and culminates in acclaim of the Olympian games, where Hieron has won the single horse race; the second (lines 113-4) considers ‘greatness’ (µεγάλοι, 113) and finds its ultimate manifestation in kingship, the political pinnacle that Hieron has scaled in Syracuse.83 Viewed against this background of epinician priamels that enhance the praise of the laudandus, Herodotus’ use of the form in 1.1-5 takes on an ironic colouring, since the general context or category of this opening is blame rather than praise—seeking the αἰτίη of the Greco-Persian wars, Herodotus proclaims Croesus responsible for initiating, within historical memory, the sequence of injustices that characterise the contentious relationship between Europe and Asia, the Greeks and the Persians.

This assessment of blame not only inverts a common use of the priamel in epinician, but also anticipates a radical departure from the portrayal of Croesus himself in the genre, where despite his foreign origins he serves as a positive paradigm of prosperity (ὄλβος) and generosity for the Greek aristocrat.84 [Note 84: Croesus makes only two appearances in extant epinician poetry (Pi. Pyth. 1.94,

Bacch. 3.23-62), and his Pindaric appearance is very brief indeed. Nonetheless, several scholars have characterised the king’s generosity as a traditional theme of epinician: cf. Nagy (1990) 276; Crane (1996) 58; Kurke (1999) 131] By dramatic contrast, in his programmatic confrontation with Solon (1.29-33), the Herodotean Croesus is portrayed as a non-Greek, Asiatic ‘other’85 with a perspective on material wealth that (for all his generosity to

Delphic Apollo) proves disastrously shortsighted [Note 85: This is not to deny the point made by Pelling (1997) that in some important ways Herodotus presents Croesus and Lydia as ‘on the cusp’ between East and West, and by no means straightforwardly Asiatic. Nonetheless, I would argue that in the discussion of what constitutes olbos Croesus’ focus on money (after giving Solon a tour of his treasuries, 1.30.1) allies him with the ‘objectification or reification of value among the Persians’ that Konstan ((1987) 6a) has discerned in the Histories. At the same time, and as Pelling himself ((2006a) 143) observes, much of Solon’s moralising is recognisable as ‘conventional Greek wisdom’. Only over time does Croesus come to recognise the wisdom of this Greek sage and ‘the god of the Greeks’, Apollo (1.87.3, 90.2: for these scornful references to Apollo bya still unenlightened Croesus, cf. Harrison (2000) 215)]. For as long as Croesus possesses his Eastern riches and monarchy, he is unable to appreciate the Hellenic wisdom expounded by Solon, who defines ὄλβος from the perspective of a moderately wealthy citizen of a Greek polis, while warning of the threat to human prosperity posed by the resentful deity. Only after losing his riches and power with the fall of Sardis, as his funeral pyre burns, does Croesus recognise the truth of Solon’s words (1.86.3-5), anticipated in Herodotus’ own observation of the transience of human success at the end of the prologue (1.5.4). Gregory Crane has demonstrated the rarity of the term ὄλβος and its derivatives in Greek prose; concluding that ὄλβος is a marked poetic term with specifically epinician associations, he argues that in his presentation of Croesus Herodotus ‘is exploring and redefining in prose the assumptions which underlay epinician poetry’.86 In other words, one function of the Herodotean scenes involving Croesus and Solon is to explore the complex attitudes towards luxury and wealth in archaic and classical Greek culture. If I am right to suggest that the prefatory priamel of the Histories evokes the use of that structure and the characterisation of Croesus in epinician lyric, Herodotus anticipates from the outset of his work a dialogue with one branch of the poetic tradition that engages issues of profound social, political, and historical importance."

From the article of Charles C. Chiasson “Herodotus’ Prologue and the Greek Poetic Tradition”, Histos 6 (2012), 114-143.

Source:

My only comment to this excerpt from a very good text of Pr. Chiasson on Herodotus' Proem and its relation with the Greek poetic tradition is that, if it is totally true that the opposition between on the one hand the constitutional structures and the civic virtues of the ancient Greek poleis and on the other hand the overconcentration of power and wealth in the Eastern monarchies is a central theme in Herodotus' Histories and that the dialogue between Croesus and Solon is indeed emblematic for this opposition, things are as always more complicated in Herodotus: Croesus is described in the Histories not as just a wealthy foolish Asiatic "other", but as a complex personality, not without virtues, but doomed like a tragic hero by hereditary sin and his own mistakes and blindness, who eventually loses throne and wealth, but is saved in extremis by the favor of the god to become the wise councelor of his victor. Moreover, greed is presented in Herodotus' work as a vice to which Greeks are not at all immune and which may lead important Greek figures to their doom (with most conspicuous example that of Polycrates, tyrant of Samos).

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Here dwells Eunomia and that unsullied fountain Dike, her sister, sure support of cities; and Eirene of the same kin, who are the stewards of wealth for mankind--three glorious daughters of wise-counselled Themis." - Pindar, Olympian Ode 13.

14 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Honeybee, what do you know,

you that are all honey and antique gold?

What do you know, Hellenic bee?

“I know of Pindar.”

Lion with fetid mane,

pensive lion,

perhaps you know of Hercules?

“Yes. And of Job.”

Viper among the sandalwood

and the lotus, magic viper,

have you worshipped Cleopatra?

“Yes. And Petronius.”

Rose that the courtesan wore

on her blue silk gown,

have you loved Mary Magdalen?

“And Jesus, too.”

Rubén Darío, Selected Poems of Rubén Darío

#Nicaraguan#Rubén Darío#Pindar#The Nemean Lion#Hercules#Job#Cleopatra#Petronius#Gaius Petronius Arbiter#Magdalene#Jesus#Jesus of Nazareth

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

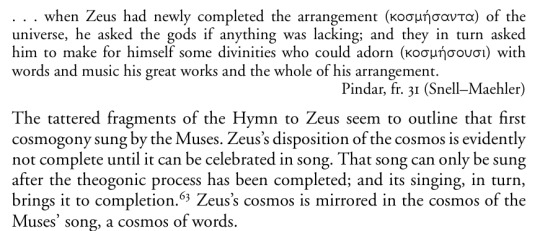

". . . when Zeus had newly completed the arrangement of the universe, he asked the gods if anything was lacking; and they in turn asked him to make for himself some divinities who could adorn with words and music his great works and the whole of his arrangement."

Pindar, fr. 31 (Snell–Maehler)

The tattered fragments of the Hymn to Zeus seem to outline that first cosmogony sung by the Muses. Zeus’s disposition of the cosmos is evidently not complete until it can be celebrated in song. That song can only be sung after the theogonic process has been completed; and its singing, in turn, brings it to completion. Zeus’ cosmos is mirrored in the cosmos of the Muses’ song, a cosmos of words.

Jenny Strauss Clay, Hesiod's Cosmos

#jenny strauss clay#hesiod's cosmos#mousai#the muses#pindar#zeus#hellenic deities#creation#cosmos#music#sacred sound#quotes

1 note

·

View note

Text

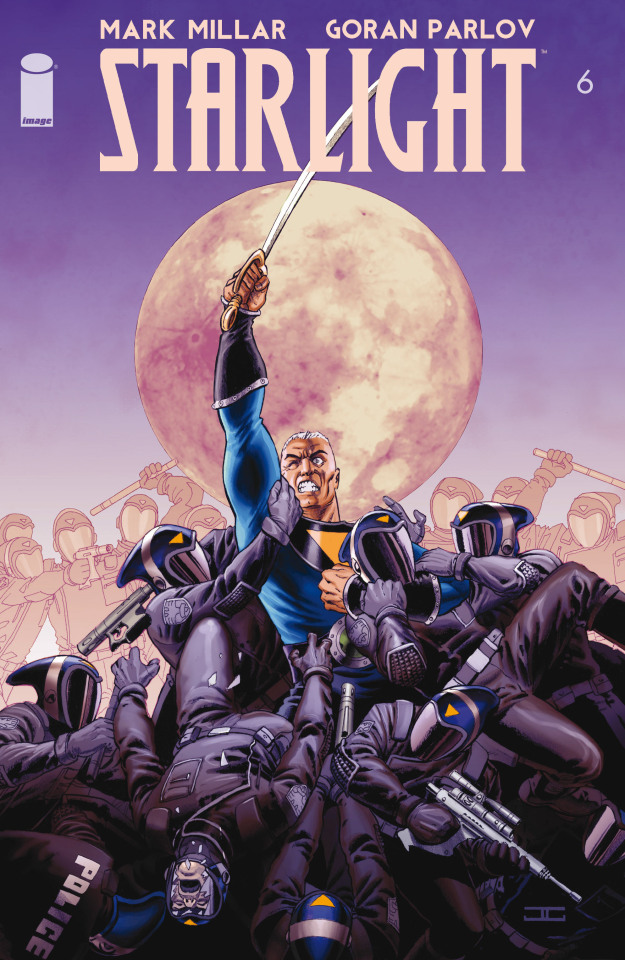

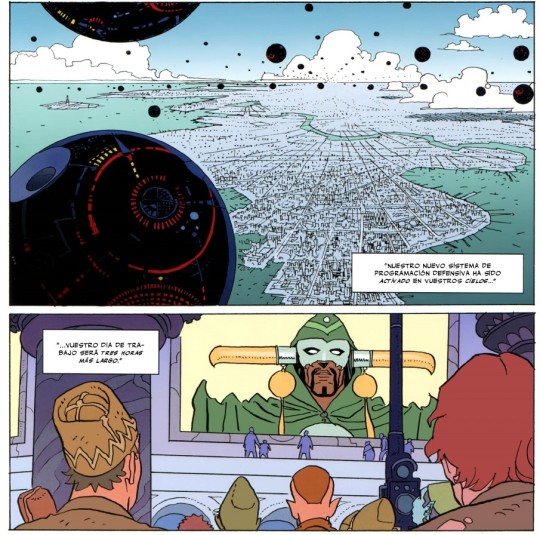

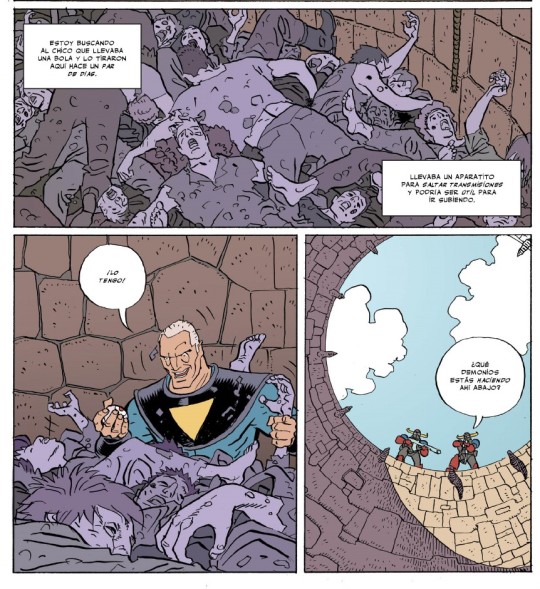

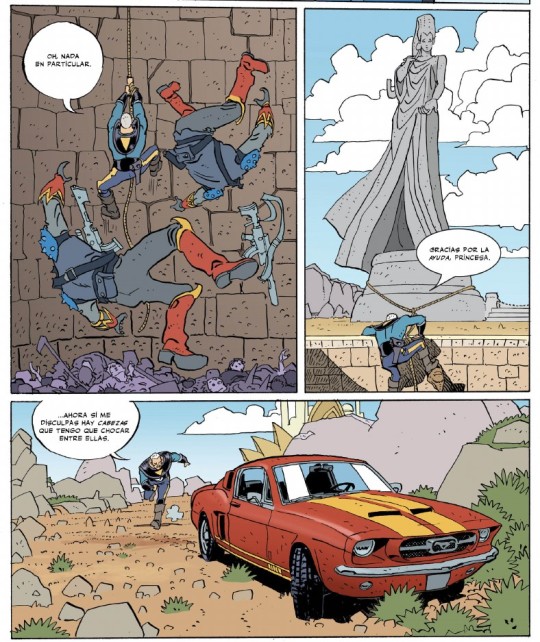

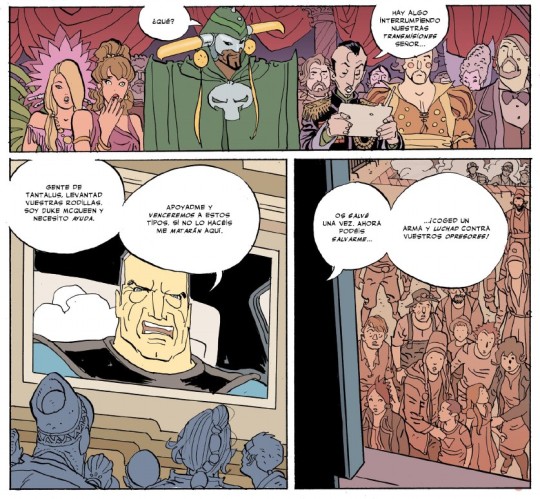

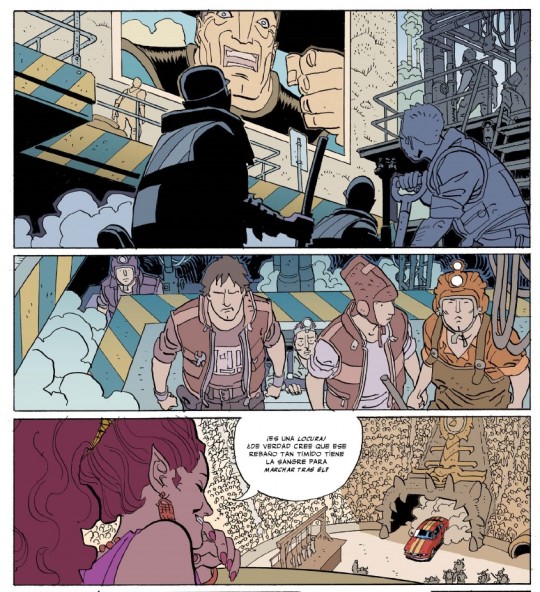

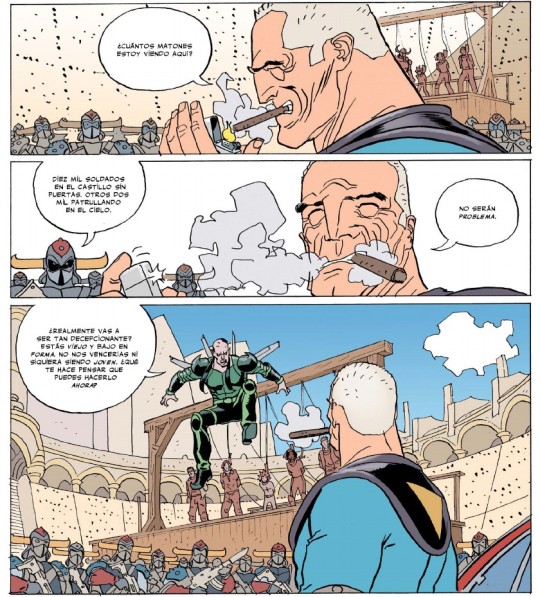

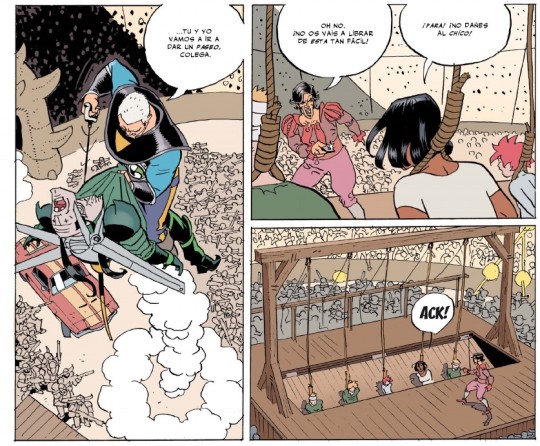

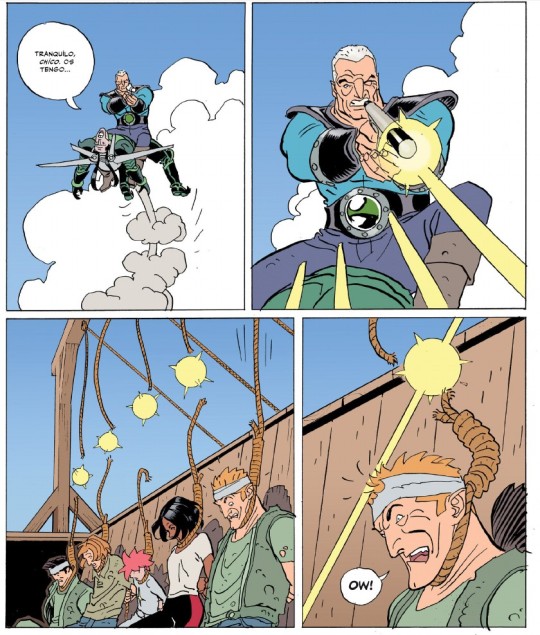

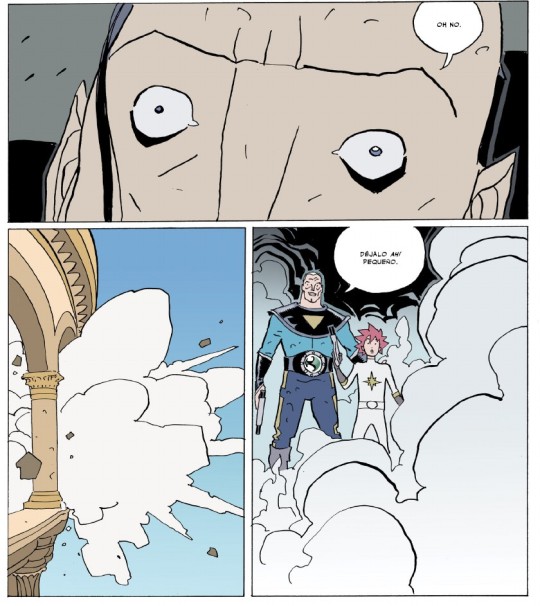

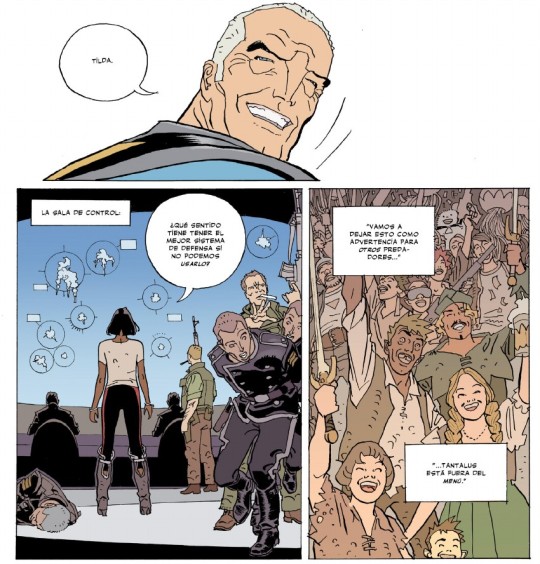

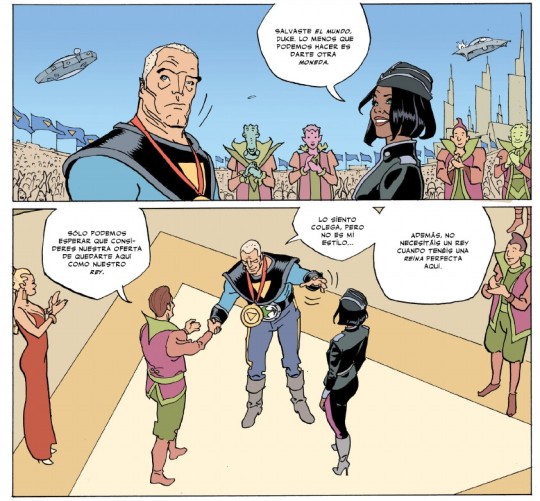

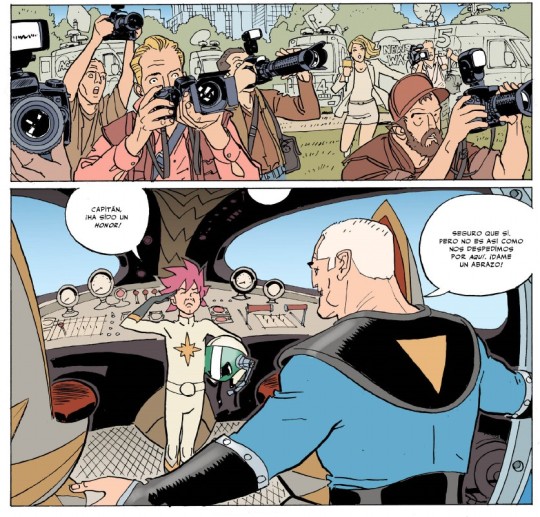

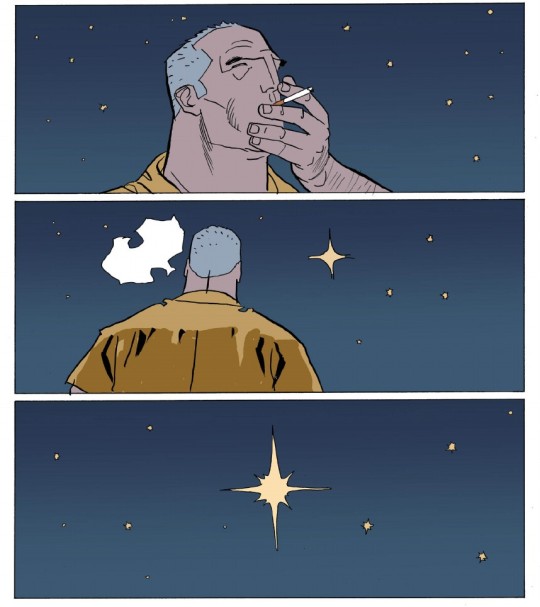

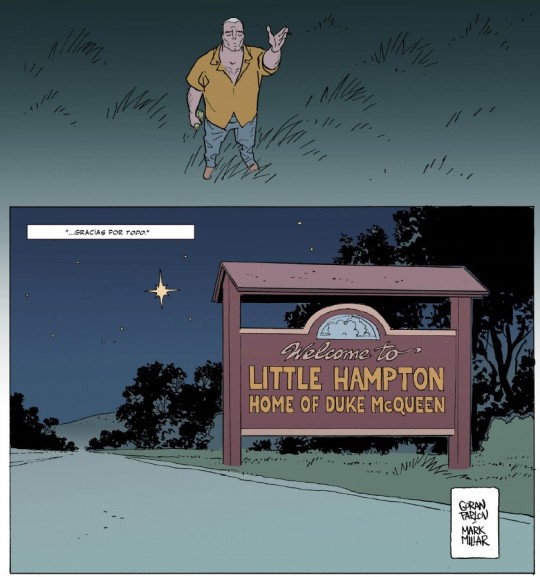

Starlight #6

Image

#Starlight#image#image comics#comic books#comic cover#cover comics#sci-fi#scifi#comics en español#comics#Duke McQueen#Krish Moore#Tilda Starr#Pindar#Wes Adams#Antaeus#Broteans#Goran Parlov#Mark Millar

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I shall now mount the prow of a garlanded ship, in order to celebrate your valour. Indeed, the courage of youth aids in frightful war, from which I say, you find boundless glory, doing battle both with horsemen and on foot. Your counsels, wise beyond your years, allow me to laud you fearlessly and on every account.

Farewell! This strain is sent, like Phoenician wares, over the hoary sea. And as for Castor's melody, upon Aeolian seas, look earnestly upon it, and the grace of the seven-stringed lyre, when you come upon it.

Become who you are - who you've learned to be.

Pindar, Pythian Ode #2, verses 62-71, c.420BC

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

γλυκὺ δὲ πόλεμος ἀπείροισιν, ἐμπείρων δέ τις ταρβεῖ προσιόντα νιν καρδίᾳ περισσῶς

- Pindar

War is sweet to the inexperienced but someone who knows trembles awfully in their heart at its approach.

#pindar#greek#classical#quote#war#battle#war is hell#society#culture#politics#band of brothers#dedicate this to my fellow veterans

101 notes

·

View notes