#Popular Sword and Sorcery Authors

Text

Exploring The Evolution of Sword and Sorcery Genre

[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ admin_label=”section” _builder_version=”4.16″ global_colors_info=”{}” theme_builder_area=”post_content”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row” _builder_version=”4.16″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” global_colors_info=”{}” theme_builder_area=”post_content”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”4.16″ custom_padding=”|||”…

View On WordPress

#Sword and Sorcery Evolution#Fantasy Genre Development#Sword and Sorcery Origins#Popular Sword and Sorcery Authors#Evolution of Hero Archetypes#Sword and Sorcery Themes#Swords and Magic Evolution#Historical Fantasy Trends#Sword and Sorcery Subgenres#Impact of Sword and Sorcery in Pop Culture

1 note

·

View note

Text

Manga Recommendation: Tower Dungeon

So looks like Arkus Rhapsode is here to recommend another fantasy manga after the last one. So this time we're going for a bit of a different flavor with the series Tower Dungeon by by Tsutomu Nihei who you may know as the creator of Blame! and Knights of Sidonia.

Now I've known about this series for a bit even though it is relatively new. Having only started last year in Monthly Shonen Sirius. But I remember its announcement from people like Manga Mogul and hearing Makoto Yukimura (Author of the incredible Vinland Saga) recommending it. Now I always loved Sword and sorcery so I was gonna read it eventually, but it just wasn't translated. However, now being able to read the available chapters, I can say this is a very different type of fantasy series.

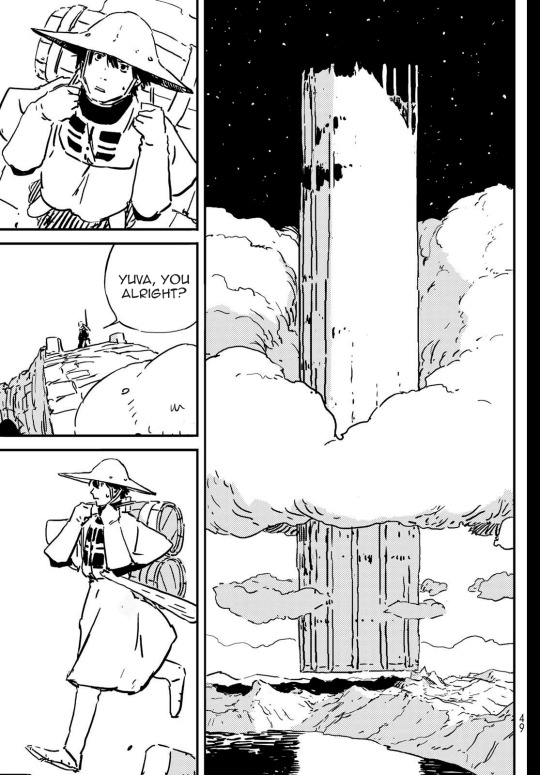

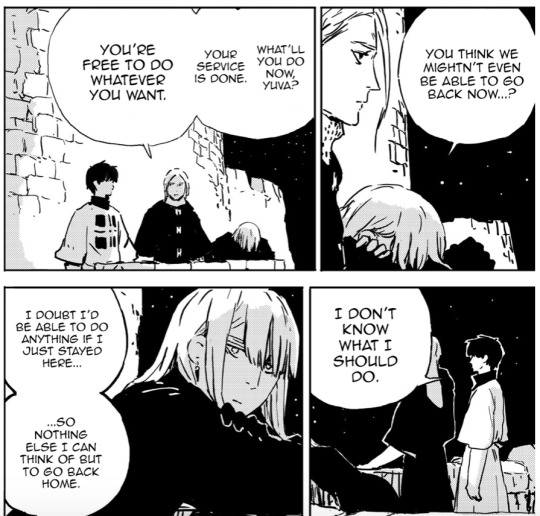

The premise is very basic: An evil sorcerer has killed a nation's king and kidnapped a Princess and now the royal knights need to ascend the "Dragon Tower" to save her. One battalion has conscripted a young man named Yuva for assisting troops medically has found he has impressive strength. Now Yuva must strengthen himself for the journey ahead as they explore the deadly tower.

Now like all simple premise stories, the real strength is in execution. And unlike the other fantasy series I've talked about before which have bucked the trend of "RPG fantasy" be leaning more into a traditionalist fantasy stories a la Tolkien, this goes for the more realist fantasy of something like Berserk or Dark Souls.

The world of Tower Dungeon may have things like magic and dragons, but it is a dingy, dirty, and lacks any frills. Knights wear heavy armor and people are covered in blood and scars from their adventures.

The mighty Dragon Tower itself? The most iconic thing about this series and the basis of the adventure? Looks like this. This isn't an opulent tower, this is a massive imposing structure where monsters dwell.

However, unlike some grim dark or edgy fantasies, this world isn't indulgent in its darkness. The violence and death are never cool or cheap. They are simply the way the world is. Even when magic exists, the world is still like Medieval Europe and all the "joys" that come from it.

The people as well are similar. These aren't romanticized or polished fantasy archetypes that often come with the idea of a Dungeons and Dragons style adventure, these feel like average joes plucked off the streets having to do a job. If you are say a fan of something like Chainsaw Man, this sort of post modern emphasis on people acting like regular weirdos and not some "anime characters." And I think that is something quite nice that even in a fantastical world, we can see our regular selves in them.

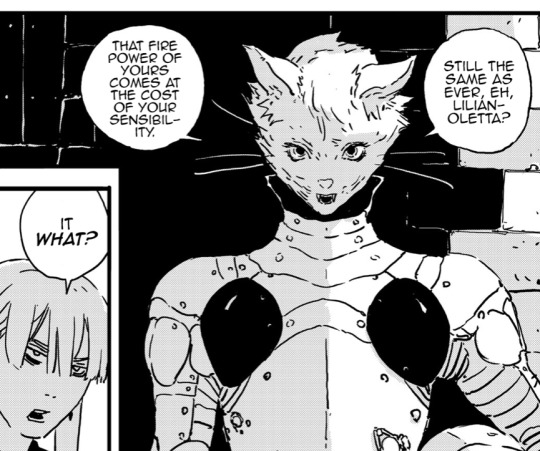

But that's just the story, what about the art? Well if you've noticed this series does have a very minimalist style. Something similar to that of Land of the Lustrous or Chainsaw Man. These almost scratchy and not the most detailed designs that make use of their simplicity to create this very unique atmosphere.

Creature designs themselves are less fantastical and more grody. Feeling as if they come from an off shoot of man rather than some majestic beast. Right down to the cat people.

This series is still new and sadly hasn't been officially translated yet. I've had to use mangadex to read this, so my heart goes out to the translator team. I can understand that this may be a niche that's not for everyone, but its something that feels like such a good sign for fantasy as a genre. A genre that I think has somewhat been stagnated in popular belief with the greater emphasis on Urban Action manga and the reliance on escapist fantasy anime like isekai. To see a more dirty but down to earth take on the premise, I highly recommend it.

#manga#manga recommendation#recommendation#tower dungeon#tsutomu nihei#nihei tsutomu#blame!#shonen sirius#chainsaw man#dark souls#knights of sidonia

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Literary references in Gale's selection remarks

I. Theatrical plays (Shakespeare & Walter Scott)

- A rough tempest I will raise. - Shakespeare - Tempest, - this is a mash-up of two quotes:

In Act V, Scene 1, Prospero uses the phrasing "when first I raised the Tempest". In the same scene, he recites a soliloquy about the great works of magic he has accomplished, before finally renouncing magic altogether: " ... But this rough magic I here abjure ..."

This is an incredibly apt sentence for Gale - one can interpret this tempest as his magical capabilities or just the calamity of the orb, or even his end game choice. The whole play which begins with a shipwreck might be compared to the plot of BG3.

- What fools these mortals be. - Puck - A Midsummer Night’s Dream

- All the world's my stage and you're just a player in it. Shakespeare, again. As You Like It Link

- Oh, what a tangled Weave we web! - riff on a quote from Sir Walter Scott's play Marmion.

The original quote is "Oh, what a tangled web we weave, when first we practice to deceive!"

II. Pop-cult

- Swords, meet sorcery!

This is a reference to the term "Swords & Sorcery" which was coined by F. Leiber (author of the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser series) in 1961. Quoting from wiki: Sword and sorcery (S&S) or heroic fantasy is a subgenre of fantasy characterized by sword-wielding heroes engaged in exciting and violent adventures. Elements of romance, magic, and the supernatural are also often present. Unlike works of high fantasy, the tales, though dramatic, focus on personal battles rather than world-endangering matters. Sword and Sorcery tales eschew overarching themes of 'good vs evil' in favor of situational conflicts that often pit morally gray characters against one another to enrich themselves, or to defy tyranny.

- Gone with the Weave.

I think this is just a reference to the term "Gone with the wind" but not infamous book, lol.

- No gloom, all doom.

Riff on the popular expression "gloom & doom".

III. Religion

- Seek and you shall find me.

Jeremiah 29:13 You will seek me and find me when you seek me with all your heart.

Matthew 7:7–8 "Ask, and it will be given you. Seek, and you will find. Knock, and it will be opened for you. For everyone who asks receives. He who seeks finds. To him who knocks it will be opened.

While I don't think Gale is our Lord and Saviour, this is an interesting line. I would not be surprised if the writers had also remarked on his peculiar resemblance to someone...so I think this is an inside joke.

- Let me recite their demise.

This alludes to the custom of reciting prayers for the dying and the dead (a common practice in Abrahamic religions).

IV. D&D homages & references

- Don't make me go all Edwin Odesseiron on you.

So Edwin was a possible companion in BG1 & 2. A lawful evil red wizard of Thay. If you have seen the new movie I don't need to explain further, but for those who don't: basically Lorroakan as a companion. He greets the protagonist with this: “ Greetings. I am Edwin Odesseiron. You simians may refer to me merely as "sir" if you prefer a less... syllable-intensive workout."

Gale basically threatens to go all power-hungry wizard on us - mind, this is a funny line you can only hear if you select him in combat over and over again (spamming).

- I hope Halaster takes good care of Tara while I'm away.

Halaster Blackcloak was was a notorious, ancient, and utterly insane wizard who resided within his lair, the infamous Undermountain ( located deep beneath the city of Waterdeep) and died in 1375, so circa 120 years before BG3 takes place (late 1492). As part of his many preparations to escape death, Halaster created a number of clone-bodies to receive his consciousness, which he kept locked in protective stasis and located throughout Undermountain and the lower reaches of Waterdeep. When Halaster died prior to the Spellplague, it was possible that one or more of these clones was activated and set free by 1479 DR, although this is not confirmed.

I guess this must be a joke in wizard's circle in Waterdeep :-) This is also a spam line, so one can only hear it if they really like to click on Gale.

- Coliar, Karpri, Anadia... So many worlds still to travel. One day. (looking at the astrolabe)

Coliar, Kapri, Anadia - are all planets in the system (Realmspace). Toril is the third planet, where Faerun is. To reach these places you need to use spelljammers. Gale needs to hitch a hike from Lae'zel I guess.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

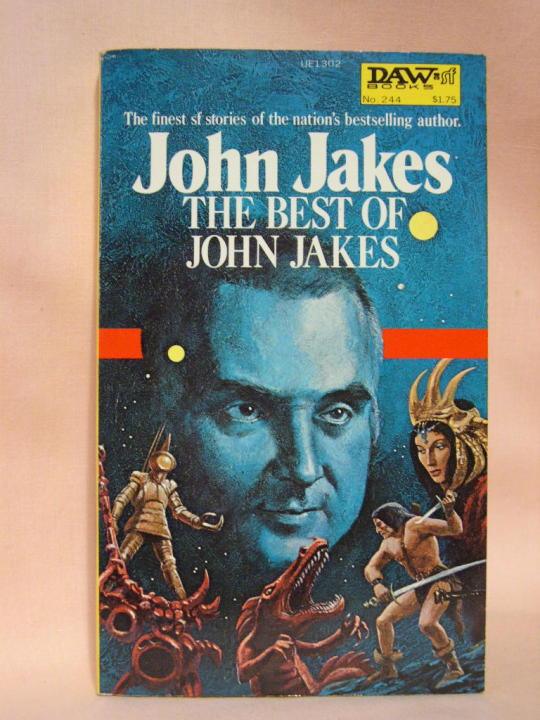

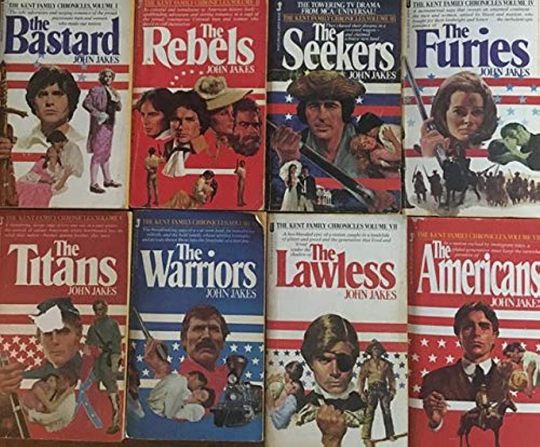

RIP John Jakes, Pulp and Fantasy Author

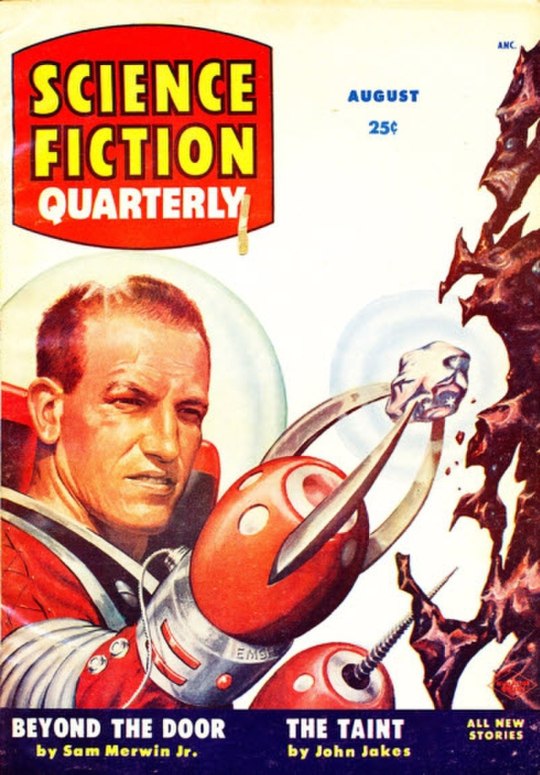

A man who’s career began in pulp scifi, then was one of the greatest group of fantasy fans turned authors, and who finally ended it as one of the most commercially successful “men’s adventure” paperback novels of the 1970s, John Jakes died at 90 last week. What a life! He started his career in scifi pulp of the 1950s, switching to sword and sorcery action in the 60s, and finally, ending the 70s as one of the top selling authors of the decade. In one guy’s life, you can see the ebb and flow of trends in men’s adventure fiction over the decades.

Let’s start the John Jakes story at the end, and then work our way back. Does this book series above look familiar to you at all?

If you have grandparents and they live in America, I 100% guarantee the Kent Family Chronicles (also called the Bicentennial Series) are in your Mee Maw and Pep Pep’s house right now. You probably handled them while visiting their house and went through their bookshelves as a child, right next to their Reader’s Digest condensed books, Tai-Pan and Shogun by James Clavell, copies of the endless sequels to Lonesome Dove, and old TV Guides they still have for some reason next to the backgammon set. If your grandparents are no longer with us, you probably found this series when selling their possessions after death. That’s because these things sold in the millions, back when the surest way to make money in writing was to write melodramatic, intergenerational family sagas of grandiose sweep set around historical events. Weighty family sagas, ones critics call bloated and self important instead of “epic,” were a major part of 70s fiction as they were four quadrant hits: men liked them for war, action, and history (every guy at some point must choose between being a civil war guy, or World War II guy) and ladies loved them for their romance and melodramatic love triangles (after all, the Ur-example of this kind of book is Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind). This was the kind of thing turned into TV event miniseries, and ably lampooned in the hilarious “Spoils of Babylon” series with Kristen Wiig and Toby McGwire, which, decades after the fact, did to this genre what Airplane! did for the formerly prolific airport disaster movie: it torpedoed it forever by making it impossible to take seriously.

This genre eventually went away because men stopped being reliable book buyers and book readers in the 1990s (or at least, were no longer marketed to as an audience), Lonesome Dove’s insane popularity was the last gasp of this audience. I’ve said this before, but men and boys no longer reading is the single most under remarked on social problem we have. “YA books” now basically mean “Girl Books.”

John Jakes did not suddenly come out of nowhere to write smash hit bestsellers set around a family during the American Revolution. He came from one of the weirdest places imaginable: a crony of L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter in fantasy and weird tales fanzines like Amra, he was one of the original “Gang of Eight,” people drawn from fantasy and horror fandom to become pro-writers now that fantasy fiction had a home at Ballantine Publishing, just before the rise of Lord of the Rings and the paperback pulp boom, which is an incredible case of being in the right place at the right time. There, John Jakes, a fanzine contributor and ERB fan, wrote “Brak the Barbarian,” which is amazing as L. Sprague de Camp and Ballantine hadn’t even reprinted the Conan stories yet and Conan was as well known as Jirel of Joiry or Jules de Grandin. Only superfans of pulp knew who that guy was at all, there was no audience for it. He wrote Brak the Barbarian as a superfan, and was lucky the paperback market found him.

The tireless work John Jakes, Lin Carter, L. Sprague de Camp, and the Gang of Eight did in preserving fantasy novelists of the pulp age into the 50s-60s is one of the great historic feats of preservation and keeping fandom flames alive. It’s no exaggeration to say that you know who Conan the Barbarian and HP Lovecraft are right now because of them, fans who kept the flame alive tirelessly and thanklessly in the ultra-rational 50s that had no place for dark horrific fantasy.

Like his friend in fantasy and pulp fandom, L. Sprague de Camp, John Jakes started as a scifi guy in the endless scifi pulp magazines of the 1950s. Unlike his friend de Camp or Hugh B. Cave, who were full of humor, characterization, and satire, Jakes was often pessimistic, dour, and downbeat, and he disliked to laugh.

It’s shocking to lose someone with a connection to, in one lifetime, the first great group of fantasy fandom, 50s scifi pulp, and 70s men’s adventure. John Jakes’ life spanned all of them.

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Liane The Wayfarer”: “Sword and Sorcery” Literature At Its Finest

Art Credit: Konstantin Koborov

Fantasy literature acts as a form of escapism for those who may find an ordinary life so mundane. “Liane The Wayfarer” by Jack Vance is an amazing example of this escapism. I found myself completely encapsulated in the world of the story through Vance’s writing, especially the ending which I will discuss later in this review. The story itself was published in a collection written by Vance of interconnected stories known as The Dying Earth. Vance holds an incredible legacy, publishing books and collections in science fiction and fantasy alike that are celebrated by multiple authors such as George R.R. Martin. The influence of Vance and The Dying Earth series can be seen today in multiple sources of media that aren’t just literature as well. Multiple video games, films, and television shows present references or homages to the works of this author. Having these influences shows the prowess of an amazing writer in fantasy literature, progressing the widespread popularity of the sub genre known as “sword and sorcery.”

This work follows Liane the Wayfarer, a young overconfident adventurer that travels for no apparent reason at first. As we are introduced to our character, the cocky young man finds a bronze ring that has the power to turn him invisible. He is unsure of the ability until he encounters a small creature riding a dragonfly only known as a Twk-man who tells the adventurer of a beautiful witch named Lith. Now setting off to find her, Liane finds the witch shortly who is immediately annoyed by his conceited personality and tries to ward him off. Not backing down from a challenge, Liane persists in his efforts to woo Lith until she pities him and gives him a quest to prove his love to her. The quest is simple enough: find who took the other half of a beautiful tapestry in Lith’s possession and return it to her. Seeing this as a simple task, Liane sets off on his journey. Along his path, Liane makes a stop at the Magician’s Inn to rest and drink. After a while of drinking with wizards and others, Liane accidentally lets his quest slip. At the mere mention of the name of Chun, the festivities stopped and the wizards retreated to their chambers while Liane sat dumbfounded. The next day, Liane sets back out on his quest for Lith and finally finds his destination. Upon entering the territory of Chun the Unavoidable, an old man warns the “hero” of his fate but ignores the advice and proceeds on. The fate of Liane is decided from there, presumably losing his life to Chun in his search. However, the story cuts back to the witch who now has threads of the tapestry on her doorstep, showing the symbiotic relationship of Chun and Lith.

As previously mentioned, the writing of Vance is masterful for such a short work with an excellent environment to match. Much like Michael Moorcock, Vance is very descriptive with the surroundings of the characters and makes one visualize what he is writing very well. This is done by using discussion of colors around the world of our characters and very precise details of certain objects and atmosphere. Fantasy is incorporated in this work in a way that is not overwhelming as well and somewhat easy to understand for a new fantasy reader. Even though one does not get much introduction to the world, the magical elements present feel very grounded in reality compared to higher fantasy works. The best example of this simple introduction to magic comes from the inn that Liane stays at with wizards. The scene essentially serves to show that there is magic in the world rather than to explain it, presenting wizards doing pseudo parlor tricks rather than using their abilities for battle. With the uncomplicated incorporation of magic comes a little confusion, however. The magical artifact held by Liane is the main source of my confusion due to this lack of rules present. What exactly is this artifact and how does it work? This gripe is mainly coming from a long-time enjoyer of “sword and sorcery” fantasy who wants to know more but isn’t that a tell of a great fantasy world?

The characters of the work are unlike anything I’ve seen before in fantasy literature. Liane serves as a critique of fantasy heroes, presenting a smug, overconfident, and self centered hero that thinks he’s larger than life. Usually, these heroes are admired in fantasy but Vance writes reactions to the character realistically. Those around Liane do not seem to like him and generally, he ruins the atmosphere of wherever he is with his cockiness. Lith serves originally as the object of Liane's desire but then transforms into the true protagonist by the end of the story with her own motivations that go against the norm of the male dominated world of fantasy. With the eye-opening twist that Lith and Chun are working together to a certain degree, it is clear that Lith has been our main character all along and Liane only served as a misdirect. The “antagonist” Chun the Unavoidable is the scariest character I have seen in any story. Killing countless individuals for no clear reason and demanding more, this character is a true embodiment of evil that scares those who even hear his name. Chun’s description further establishes just how feared he should be, adorning a cape of eyeballs and constantly being right behind any who enter his territory. The complexities of these characters further my love for the story and make “Liane The Wayfarer” so memorable.

To reiterate, I adore this story wholeheartedly. Vance has encouraged my love for heroic fantasy even further and did so in a shorter story that is not overwhelming to a general audience. The only issues I have with the work is the lack of nerdy details about the overall location and time where it takes place but this arguably makes it more accessible. Hopefully with reading more of Vance’s works, I can understand more of the world I crave but this was an excellent introduction to the creative mind of the author.

Works Cited

Vance, Jack. “Liane The Wayfarer” The Big Book of Modern Fantasy, edited by Ann VanderMeer and Jeff VanderMeer, Vintage Books, 2020, pp. 23-29

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Alex!! I loved your ask this week, so I'm pulling an uno reverse card and asking the same of you!!

What's the popular media like in your world(s)? What are they about? What made them popular? And, as a bonus: are any of them despised or deeply adored by your characters?

I hope you have a lovely day! - @magic-is-something-we-create

Happy belated wbw @magic-is-something-we-create ! I've been thinking for a week on how to answer lmao ummmm,,,

One I reference a lot is a poem/epic/tale that started off as factual and has since turned folktale-ish? I don't have a proper name for it so I tend to call it "The Ballad of Adrastos and Dione" which as it sounds is a writing about two Luricaen lovers who died during the Luricaen Wars. They spent a lot of their lives being hunted before hunkering down, holding their own for a couple of weeks, and eventually took each other's lives to avoid capture. Their sacrifice has since, obviously, been immortalized.

Said "ballad" is especially big during the times of TOOD but kind of has fallen out by the time of ASMLP. It's kind of been relegated to "child's song" status a la Ring Around the Rosie or London Bridge is Falling Down. There's been a couple of music groups who have since... remade? Retold? This Ballad, but it lacks the critical acclaim it once had.

There is also a niche in writing I'm as of now dubbing "prophet prose". Pioneered mostly by Diviners, this genre (?) of fiction aims to try to tell the future through its work. Of course, the real success and acclaim doesn't tend to come until after said author has passed. It's kind of like scifi, except instead of saying "hey wouldn't it be cool if we went to space" it was "I bet you my entire life's worth that this thing will happen by this time". Due to the somewhat uncertainty behind the genre, it has been relegated to the corners of the literary worlds. A lot of people hate it. Some people, like Nadia, eat that shit up like candy.

There's also a sort of weird mix between what we could consider sword and Sorcery and historical fiction? Since ASMLP takes place a couple hundred years after the events of TWEfA, there are historical texts of the times and magic was a lot different, but as history tends to the facts got a bit warped along the way.

Speaking of history and "prophet prose" there is a currently unnamed author who is highly divisive because they write a lot of... "anti-chosen one" literature? They are a priest of a God I haven't decided and since priests are sometimes chosen against their will this author writes a lot of "this person was chosen and it sucks" and "dude has a normal happy life and ignores the call of the gods"... due to the climate of the world, this unnamed author is so divisive because it's akin to like. Writing fanfic about you killing God and having it published by Pope Francis or smth. It's incredibly hubristic. Due to its kind of counter-culture flavor, tho, this Author's works are something of a cult classic.

Photography has also turned into an arms race of who can photograph the weirdest shit possible. Computers and photoshop don't exist so a lot of people spend their time trying to alter photos to look weird without completely ruining them. This brand of photography is called Arcane Abstractism and is incredibly popular. Simone doesn't like it. Nadia is,,, iffy.

Fair warning I did make a lot of this shit up just now but I'm sticking to it.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

With the idea of tbe multiverse becoming more and more popular in fiction, I'd like to suggest a property to whatever network company social media interns may be reading this: Michael Moorcock's Multiverse and the Eternal Champion.

Quick recap for those of you who don't know what I'm talking about - for essentially the latter half of the 20th Century, British author Michael Moorcock put out a bunch of novels that focused on different incarnations of the same figure - the Eternal Champion. The Eternal Champion was a figure who's purpose was to maintain the balance between Law and Chaos (the two major forces in the multiverse, either of who's victory spells the end of that universe), reincarnated over and over throughout time across the multiverse, damned to fight unending battles.

The Eternal Champion came in many forms in many genres, from the sword and sorcery of Elric and Corum to the secret agent Jerry Cornelius to airship pilot Oswald Bastable and more.

The way one could pull a series based on this figure off is to make it an anthology-driven franchise, with different arcs focusing on different incarnations until you eventually have some massive crossover or something. You can use a repeating set of imagery to convey to the audience what characters are incarnations, as many are unaware of the role they play.

You'd get all sorts of genres, so people who like dark fantasy get something, people who like spy media get something, people who like steampunk get something and so on and so forth.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

what a read but this section in particular, damn:

So, MZB deserves her own comment. And this is where my sarcasm comes from in my original comment. Because for almost 2 or 3 decades or more, authors and fandom existed pretty peacefully side by side. Authors would solicit stories to edit for anthologies of both the 'fan' nature, ie. Darkover, Asimov's Universe, and original nature ie. "Sword and Sorcery." You had scifi and fantasy magazines. Star Trek zines were really popular. So on and so forth. Really different time. But these were pathways to publishing and getting publishing deals. You got some short stories in anthologies, well, then publishing would take a chance on a longer book. See Mercedes Lackey, Tanya Huff... etc.

This was before MZB was known to be an awful person. She was a big fantasy author and a big editor. She put out she was doing an anthology again for Darkover. She had a book she was writing for the series at the time, a big one featuring a extremely popular character. She opens up a submission and there in the short story was the basic plot idea of her novel. She reaches out, offers the short story author 500 dollars and a byline on the copyright page. Her usual modus operendi when this happened, and the woman went "No. I want my name on the cover with yours and part of the royalties."

Well, DAW went. "This is a headache we don't want to deal with." And canned the entire novel. 4 years of work down the drain for MZB, because one fan author got entitled and DAW got scared. Be aware, this was entirely DAWs decision. It's publishers. It's always publishers.

The story went "viral" for the time. (This was before internet.) And it got blown up completely out of proportion to where MZB got SUED and a whole bunch of agents and publishers told their authors to come out against fanfic even if they weren't against it. Entire Zines got shut down. And MZB and others decided to stop soliciting short stories for anthologies. This false story is still swirling around there in the ether with popular youtubers talking about it without doing the research. (Argh.)

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is media like in the Rhine City verse? What are some recurring shows within a show?

We haven’t super got into it, and there’s quite a bit of media that’s fairly different too! A lot of in-universe series are based on scrapped story concepts, some of which long-time viewers of my blog might remember. Here’s a few things I came up with:

The Handy & Ydnah Show: The bastard child of Oobi and ATHF. It’s a PG show beloved by adults and stoners for it’s weird and surreal plots. The production of it is extremely mysterious; no one knows much about it even though it debuted in the 80s.

Tales of Aethra: Based on one of my oldest story ideas. It’s essentially a long-running multimedia fantasy franchise, though its popularity is comparable more to something like He-Man or Xanth than something like LotR. It has gotten a well-regarded animated series, several books, and a crossover set with MTG.

Mercenaries: Based on the story Eric originated from. Basically an over-the-top stunt-heavy action franchise a la John Wick, featuring a sendup of Snake Plissken as its lead (his name is Max Viper). Venus Crowley’s character Scarlet Love became a huge breakout and shot her to stardom.

Genesis: Based on the story David Paine originated from. A TV series about a future where some of the population have superpowers. It’s like Akira or Heroes back when the latter was good.

SafeWord: 90s cult classic comic about a queer S&M themed superhero. Was adapted into an equally cult classic film by Troma. Based on an old OC idea I had.

Virgin Killer: A more recent movie, an action-comedy about a young man who dresses in a Virgin killer and enacts vigilante justice on incel type guys. Based on a joke someone sent into my blog once.

Dick Kicker: Private Eye - A film noir parody series in the vein of Naked Gun. Very deadpan, very respectful of the genre.

Bottom Line: A blaxploitation series from the 70s about the eponymous martial arts hero who protected his community from various threats.

Arya Mournblade series: Long-running sword-and-sorcery fantasy series notable for consistently keeping the same actress from the original 80s film all the way to the 2017 finale. One of the films is infamous for featuring aliens as the antagonists.

Prudence Clay, Student Witch: A young adult fantasy book series by author Frida Spinney, which was hailed as the next Harry Potter by critics. The books have come under constant scrutiny for some extremely problematic elements, not helped at all by questionable comments she made online which inspired others to make similarly questionable comments (she’s friends with JKR if that tells you anything).

The Will of the Old Ones: A book by an author going by “Charlotte Webber.” It is a cosmic horror story whose content was overshadowed by a plagiarism lawsuit alleging the text was cobbled together from several unpublished manuscripts. The author making the claims of plagiarism was eventually found dead of an apparent suicide and the case ended up dropped. Hardly any discussion of the content of the book is made anymore, only the insanity around it.

Salty Steve’s Pirate Pizza Palace: A Charles Entertainment Cheese competitor founded in 1987. The discordant mashup of pirate and dinosaur theming has given it an odd charm that has helped it stay afloat, also helped by it getting a surprisingly good SNES game based around it.

Rubber Octopus: Popular mid 2000s indie rock band.

Six Shots: Based on an old scrapped superhero story idea. It’s not made yet, but it’s the next script James Gunn has for a movie, and Venus is gonna star in it.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantasy Authors' Names

At my writing tutor job one evening, I was bored out of my mind and looked up fantasy series. The catalyst for this was the recent Wheel of Time series. All the classic, most popular fantasy series are written by white male authors. Some people speculate that Sapkowski's Witcher was a ripoff of Moorcock's Elric. At first glance, it appears these series all have the same sword and sorcery tropes. This led me to create the uber-mensch fantasy author name:

Terrobandmich R.R. Goodbrookscocksapordanski

Breakdown of the combination of names is as follows:

Terry Brooks and Terry Goodkind - Ter

Robert Jordan - Rob

Andrzej Sapkowski - And

Michael Moorcock - Mich

J.R.R. Tolkien and George R.R. Martin - R.R.

Terry Goodkind - Good

Terry Brooks - Brooks

Michael Moorcock - Cock

Andrzej Sapkowski - Sap

Robert Jordan - Ordan

Andrzej Sapkowski - Ski

Their fantasy series:

Terry Brooks - The Sword of Shannara

Robert Jordan - The Wheel of Time

Michael Moorcock - The Elric Saga

Terry Goodkind - The Sword of Truth

J.R.R. Tolkien - The Lord of the Rings

George R.R. Martin - A Song of Ice and Fire

Andrzej Sapkowski - The Witcher

Based on a rerun from Facebook 29 Nov. 2021. Revised 5 May 2024.

#fantasy authors#authors names#fantasy books#fantasy books series#terry brooks#robert jordan#michael moorcock#terry goodkind#jrr tolkien#george rr martin#andrzej sapkowski#male authors

1 note

·

View note

Text

Writers say it's not easy writing new stories about popular characters. But in my new interview with author Davide Mana about "Descent: Dreams Of Fire," his Sword & Sorcery novel based on the fantasy board game "Descent," he talks about how eager he was to get to tell Vaerix what to do.

📖⚔️🪄🐲

#DavideMana#DavideManaInterview#DavideManaDescentDreamsOfFire#DavideManaDescentDreamsOfFireInterview#DavideManaDescentTheRaidersOfBloodwood#DavideManaDescent#Books#Reading#AuthorInterview#AuthorInterviews#Fantasy#SwordAndSorcery#DescentLegendsOfTheDark

1 note

·

View note

Text

REDEMPTION OF THE NATIONS

The nations and the kings of the earth are found in the city of New Jerusalem because of the redeeming work of the Lamb.

Revelation presents images that are jarring and paradoxical, visions that do not conform to popular expectations about how God works. His plans to subjugate His enemies and judge the nations differ radically from traditional notions. Just as his contemporaries did not understand Jesus, so we also fail to comprehend the “slain Lamb” who reigns from God’s throne.

For example, in the vision of the “rider on a white horse,” the figure’s robe is “sprinkled with blood” BEFORE he engages in “combat” with the “Beast” and its allies. Whose blood was it, and how did it get there?

The rider’s only weapon is the great “sword” that “proceeds out of his mouth.” Rather than a bloodstained blade hanging from his belt, on his thigh, it is written - “King of kings and Lord of lords.”

THE LAMB’S WAR

He is the “Word of God” sent to “judge and makes war IN RIGHTEOUSNESS,” NOT in rage. The men of his “army” are “clothed with fine linen, white and pure” with no weapon in sight. And his “sword” is used “to shepherd the nations,” not to crush or behead them.

At first glance, this “war” appears to result in the destruction of the “nations” and the “kings of the earth.” However, both groups reappear in the vision of New Jerusalem where the “nations” walk in the Lamb’s light, and the “kings of the earth bring their glory into” the city.

Rather than the aftermath of a great slaughter, the life-giving river flows from the throne. It is bordered on either side by the “tree of life,” and “its leaves are for the HEALING OF THE NATIONS” - (Revelation 21:24-26, 22:1-4).

In the book’s prologue, Jesus is identified as the “ruler of the kings of the earth,” the one who has redeemed us and made us a “kingdom of priests.” This statement uses past tense verbs to describe things achieved already by his death and resurrection.

Thus, already, the “saints” reign with him, and they do so as “priests,” not soldiers or conquerors. Instead, they mediate his light to a dark world. And they “overcome” and reign in the same manner as he did - by self-sacrificial service, perseverance, and yes, even martyrdom - (Revelation 1:4-6, 3:21, 12:11).

RULER OF NATIONS

If Jesus is the “ruler of the kings of the earth,” what kind of king would he be if he allowed Satan to deceive and conquer the “nations” for all time? After all, is he not the Messiah who overcame to “shepherd the nations”? What kind of shepherd allows a predatory beast to slaughter his sheep? - (Revelation 12:5, 19:15).

In the book,the term “nation” is fluid in its application. It is used both negatively and positively. For example, the “Beast” is granted authority over men from every “nation, people, tongue, and tribe.”

But far more often, it is the “Lamb” who is the one that purchased “men from every nation, people, tribe and tongue.” He is the king over his redeemed people, and they belong to him - (Revelation 5:6-10, 7:9-17, 13:7-10).

At times, the “nations” are victimized by the “Dragon” and his vassals. “Babylon” is condemned because “she made all nations drink of the wine of the wrath of her fornication.” She, “by her sorceries, deceived all the nations.”

Ultimately, it is Satan who “deceives all the nations.” How can Jesus “overcome” to “shepherd the nations” if he allows the Devil to keep his ill-gotten gains? - (Revelation 14:8, 18:3, 18:23, 20:3-8).

In the end, both the “nations” and their “kings” are found in “New Jerusalem” where they give honor and glory to the “Lamb” and the One who “sits on the Throne.” This happy result is predicted in the book:

(Revelation 15:4) - “Who shall in any way not be put in fear, O Lord, and glorify your name, alone, full of lovingkindness; because all the nations will come and do homage before you, because your righteous deeds were made manifest?”

And this last prediction finds its fulfillment in the city of “New Jerusalem” - “The nations of them which are saved will walk in the light of it: and the kings of the earth do bring their glory and honor into it…And they will bring the glory and honor of the nations into it” - (Revelation 21:24-22:4).

This is not to say that the “Lamb” has no human enemies. There are men and women whose “names are not written in the Lamb’s book of life.” Unrepentant sinners find themselves cast into the “Lake of Fire.”

[READ the entire post on the End-Time Insights blog at the link below]

0 notes

Text

The Green Knight and Medieval Metatextuality: An Essay

Right, so. Finally watched it last night, and I’ve been thinking about it literally ever since, except for the part where I was asleep. As I said to fellow medievalist and admirer of Dev Patel @oldshrewsburyian, it’s possibly the most fascinating piece of medieval-inspired media that I’ve seen in ages, and how refreshing to have something in this genre that actually rewards critical thought and deep analysis, rather than me just fulminating fruitlessly about how popular media thinks that slapping blood, filth, and misogyny onto some swords and castles is “historically accurate.” I read a review of TGK somewhere that described it as the anti-Game of Thrones, and I’m inclined to think that’s accurate. I didn’t agree with all of the film’s tonal, thematic, or interpretative choices, but I found them consistently stylish, compelling, and subversive in ways both small and large, and I’m gonna have to write about it or I’ll go crazy. So. Brace yourselves.

(Note: My PhD is in medieval history, not medieval literature, and I haven’t worked on SGGK specifically, but I am familiar with it, its general cultural context, and the historical influences, images, and debates that both the poem and the film referenced and drew upon, so that’s where this meta is coming from.)

First, obviously, while the film is not a straight-up text-to-screen version of the poem (though it is by and large relatively faithful), it is a multi-layered meta-text that comments on the original Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the archetypes of chivalric literature as a whole, modern expectations for medieval films, the hero’s journey, the requirements of being an “honorable knight,” and the nature of death, fate, magic, and religion, just to name a few. Given that the Arthurian legendarium, otherwise known as the Matter of Britain, was written and rewritten over several centuries by countless authors, drawing on and changing and hybridizing interpretations that sometimes challenged or outright contradicted earlier versions, it makes sense for the film to chart its own path and make its own adaptational decisions as part of this multivalent, multivocal literary canon. Sir Gawain himself is a canonically and textually inconsistent figure; in the movie, the characters merrily pronounce his name in several different ways, most notably as Sean Harris/King Arthur’s somewhat inexplicable “Garr-win.” He might be a man without a consistent identity, but that’s pointed out within the film itself. What has he done to define himself, aside from being the king’s nephew? Is his quixotic quest for the Green Knight actually going to resolve the question of his identity and his honor – and if so, is it even going to matter, given that successful completion of the “game” seemingly equates with death?

Likewise, as the anti-Game of Thrones, the film is deliberately and sometimes maddeningly non-commercial. For an adaptation coming from a studio known primarily for horror, it almost completely eschews the cliché that gory bloodshed equals authentic medievalism; the only graphic scene is the Green Knight’s original beheading. The violence is only hinted at, subtextual, suspenseful; it is kept out of sight, around the corner, never entirely played out or resolved. In other words, if anyone came in thinking that they were going to watch Dev Patel luridly swashbuckle his way through some CGI monsters like bad Beowulf adaptations of yore, they were swiftly disappointed. In fact, he seems to spend most of his time being wet, sad, and failing to meet the moment at hand (with a few important exceptions).

The film unhurriedly evokes a medieval setting that is both surreal and defiantly non-historical. We travel (in roughly chronological order) from Anglo-Saxon huts to Romanesque halls to high-Gothic cathedrals to Tudor villages and half-timbered houses, culminating in the eerie neo-Renaissance splendor of the Lord and Lady’s hall, before returning to the ancient trees of the Green Chapel and its immortal occupant: everything that has come before has now returned to dust. We have been removed even from imagined time and place and into a moment where it ceases to function altogether. We move forward, backward, and sideways, as Gawain experiences past, present, and future in unison. He is dislocated from his own sense of himself, just as we, the viewers, are dislocated from our sense of what is the “true” reality or filmic narrative; what we think is real turns out not to be the case at all. If, of course, such a thing even exists at all.

This visual evocation of the entire medieval era also creates a setting that, unlike GOT, takes pride in rejecting absolutely all political context or Machiavellian maneuvering. The film acknowledges its own cultural ubiquity and the question of whether we really need yet another King Arthur adaptation: none of the characters aside from Gawain himself are credited by name. We all know it’s Arthur, but he’s listed only as “king.” We know the spooky druid-like old man with the white beard is Merlin, but it’s never required to spell it out. The film gestures at our pre-existing understanding; it relies on us to fill in the gaps, cuing us to collaboratively produce the story with it, positioning us as listeners as if we were gathered to hear the original poem. Just like fanfiction, it knows that it doesn’t need to waste time introducing every single character or filling in ultimately unnecessary background knowledge, when the audience can be relied upon to bring their own.

As for that, the film explicitly frames itself as a “filmed adaptation of the chivalric romance” in its opening credits, and continues to play with textual referents and cues throughout: telling us where we are, what’s happening, or what’s coming next, rather like the rubrics or headings within a medieval manuscript. As noted, its historical/architectural references span the entire medieval European world, as does its costume design. I was particularly struck by the fact that Arthur and Guinevere’s crowns resemble those from illuminated monastic manuscripts or Eastern Orthodox iconography: they are both crown and halo, they confer an air of both secular kingship and religious sanctity. The question in the film’s imagined epilogue thus becomes one familiar to Shakespeare’s Henry V: heavy is the head that wears the crown. Does Gawain want to earn his uncle’s crown, take over his place as king, bear the fate of Camelot, become a great ruler, a husband and father in ways that even Arthur never did, only to see it all brought to dust by his cowardice, his reliance on unscrupulous sorcery, and his unfulfilled promise to the Green Knight? Is it better to have that entire life and then lose it, or to make the right choice now, even if it means death?

Likewise, Arthur’s kingly mantle is Byzantine in inspiration, as is the icon of the Virgin Mary-as-Theotokos painted on Gawain’s shield (which we see broken apart during the attack by the scavengers). The film only glances at its religious themes rather than harping on them explicitly; we do have the cliché scene of the male churchmen praying for Gawain’s safety, opposite Gawain’s mother and her female attendants working witchcraft to protect him. (When oh when will I get my film that treats medieval magic and medieval religion as the complementary and co-existing epistemological systems that they were, rather than portraying them as diametrically binary and disparagingly gendered opposites?) But despite the interim setbacks borne from the failure of Christian icons, the overall resolution of the film could serve as the culmination of a medieval Christian morality tale: Gawain can buy himself a great future in the short term if he relies on the protection of the enchanted green belt to avoid the Green Knight’s killing stroke, but then he will have to watch it all crumble until he is sitting alone in his own hall, his children dead and his kingdom destroyed, as a headless corpse who only now has been brave enough to accept his proper fate. By removing the belt from his person in the film’s Inception-like final scene, he relinquishes the taint of black magic and regains his religious honor, even at the likely cost of death. That, the medieval Christian morality tale would agree, is the correct course of action.

Gawain’s encounter with St. Winifred likewise presents a more subtle vision of medieval Christianity. Winifred was an eighth-century Welsh saint known for being beheaded, after which (by the power of another saint) her head was miraculously restored to her body and she went on to live a long and holy life. It doesn’t quite work that way in TGK. (St Winifred’s Well is mentioned in the original SGGK, but as far as I recall, Gawain doesn’t meet the saint in person.) In the film, Gawain encounters Winifred’s lifelike apparition, who begs him to dive into the mere and retrieve her head (despite appearances, she warns him, it is not attached to her body). This fits into the pattern of medieval ghost stories, where the dead often return to entreat the living to help them finish their business; they must be heeded, but when they are encountered in places they shouldn’t be, they must be put back into their proper physical space and reminded of their real fate. Gawain doesn’t follow William of Newburgh’s practical recommendation to just fetch some brawny young men with shovels to beat the wandering corpse back into its grave. Instead, in one of his few moments of unqualified heroism, he dives into the dark water and retrieves Winifred’s skull from the bottom of the lake. Then when he returns to the house, he finds the rest of her skeleton lying in the bed where he was earlier sleeping, and carefully reunites the skull with its body, finally allowing it to rest in peace.

However, Gawain’s involvement with Winifred doesn’t end there. The fox that he sees on the bank after emerging with her skull, who then accompanies him for the rest of the film, is strongly implied to be her spirit, or at least a companion that she has sent for him. Gawain has handled a saint’s holy bones; her relics, which were well known to grant protection in the medieval world. He has done the saint a service, and in return, she extends her favor to him. At the end of the film, the fox finally speaks in a human voice, warning him not to proceed to the fateful final encounter with the Green Knight; it will mean his death. The symbolism of having a beheaded saint serve as Gawain’s guide and protector is obvious, since it is the fate that may or may not lie in store for him. As I said, the ending is Inception-like in that it steadfastly refuses to tell you if the hero is alive (or will live) or dead (or will die). In the original SGGK, of course, the Green Knight and the Lord turn out to be the same person, Gawain survives, it was all just a test of chivalric will and honor, and a trap put together by Morgan Le Fay in an attempt to frighten Guinevere. It’s essentially able to be laughed off: a game, an adventure, not real. TGK takes this paradigm and flips it (to speak…) on its head.

Gawain’s rescue of Winifred’s head also rewards him in more immediate terms: his/the Green Knight’s axe, stolen by the scavengers, is miraculously restored to him in her cottage, immediately and concretely demonstrating the virtue of his actions. This is one of the points where the film most stubbornly resists modern storytelling conventions: it simply refuses to add in any kind of “rational” or “empirical” explanation of how else it got there, aside from the grace and intercession of the saint. This is indeed how it works in medieval hagiography: things simply reappear, are returned, reattached, repaired, made whole again, and Gawain’s lost weapon is thus restored, symbolizing that he has passed the test and is worthy to continue with the quest. The film’s narrative is not modernizing its underlying medieval logic here, and it doesn’t particularly care if a modern audience finds it “convincing” or not. As noted, the film never makes any attempt to temporalize or localize itself; it exists in a determinedly surrealist and ahistorical landscape, where naked female giants who look suspiciously like Tilda Swinton roam across the wild with no necessary explanation. While this might be frustrating for some people, I actually found it a huge relief that a clearly fantastic and fictional literary adaptation was not acting like it was qualified to teach “real history” to its audience. Nobody would come out of TGK thinking that they had seen the “actual” medieval world, and since we have enough of a problem with that sort of thing thanks to GOT, I for one welcome the creation of a medieval imaginative space that embraces its eccentric and unrealistic elements, rather than trying to fit them into the Real Life box.

This plays into the fact that the film, like a reused medieval manuscript containing more than one text, is a palimpsest: for one, it audaciously rewrites the entire Arthurian canon in the wordless vision of Gawain’s life after escaping the Green Knight (I could write another meta on that dream-epilogue alone). It moves fluidly through time and creates alternate universes in at least two major points: one, the scene where Gawain is tied up and abandoned by the scavengers and that long circling shot reveals his skeletal corpse rotting on the sward, only to return to our original universe as Gawain decides that he doesn’t want that fate, and two, Gawain as King. In this alternate ending, Arthur doesn’t die in battle with Mordred, but peaceably in bed, having anointed his worthy nephew as his heir. Gawain becomes king, has children, gets married, governs Camelot, becomes a ruler surpassing even Arthur, but then watches his son get killed in battle, his subjects turn on him, and his family vanish into the dust of his broken hall before he himself, in despair, pulls the enchanted scarf out of his clothing and succumbs to his fate.

In this version, Gawain takes on the responsibility for the fall of Camelot, not Arthur. This is the hero’s burden, but he’s obtained it dishonorably, by cheating. It is a vivid but mimetic future which Gawain (to all appearances) ultimately rejects, returning the film to the realm of traditional Arthurian canon – but not quite. After all, if Gawain does get beheaded after that final fade to black, it would represent a significant alteration from the poem and the character’s usual arc. Are we back in traditional canon or aren’t we? Did Gawain reject that future or didn’t he? Do all these alterities still exist within the visual medium of the meta-text, and have any of them been definitely foreclosed?

Furthermore, the film interrogates itself and its own tropes in explicit and overt ways. In Gawain’s conversation with the Lord, the Lord poses the question that many members of the audience might have: is Gawain going to carry out this potentially pointless and suicidal quest and then be an honorable hero, just like that? What is he actually getting by staggering through assorted Irish bogs and seeming to reject, rather than embrace, the paradigms of a proper quest and that of an honorable knight? He lies about being a knight to the scavengers, clearly out of fear, and ends up cravenly bound and robbed rather than fighting back. He denies knowing anything about love to the Lady (played by Alicia Vikander, who also plays his lover at the start of the film with a decidedly ropey Yorkshire accent, sorry to say). He seems to shrink from the responsibility thrust on him, rather than rise to meet it (his only honorable act, retrieving Winifred’s head, is discussed above) and yet here he still is, plugging away. Why is he doing this? What does he really stand to gain, other than accepting a choice and its consequences (somewhat?) The film raises these questions, but it has no plans to answer them. It’s going to leave you to think about them for yourself, and it isn’t going to spoon-feed you any ultimate moral or neat resolution. In this interchange, it’s easy to see both the echoes of a formal dialogue between two speakers (a favored medieval didactic tactic) and the broader purpose of chivalric literature: to interrogate what it actually means to be a knight, how personal honor is generated, acquired, and increased, and whether engaging in these pointless and bloody “war games” is actually any kind of real path to lasting glory.

The film’s treatment of race, gender, and queerness obviously also merits comment. By casting Dev Patel, an Indian-born actor, as an Arthurian hero, the film is… actually being quite accurate to the original legends, doubtless much to the disappointment of assorted internet racists. The thirteenth-century Arthurian romance Parzival (Percival) by the German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach notably features the character of Percival’s mixed-race half-brother, Feirefiz, son of their father by his first marriage to a Muslim princess. Feirefiz is just as heroic as Percival (Gawaine, for the record, also plays a major role in the story) and assists in the quest for the Holy Grail, though it takes his conversion to Christianity for him to properly behold it.

By introducing Patel (and Sarita Chowdhury as Morgause) to the visual representation of Arthuriana, the film quietly does away with the “white Middle Ages” cliché that I have complained about ad nauseam; we see background Asian and black members of Camelot, who just exist there without having to conjure up some complicated rationale to explain their presence. The Lady also uses a camera obscura to make Gawain’s portrait. Contrary to those who might howl about anachronism, this technique was known in China as early as the fourth century BCE and the tenth/eleventh century Islamic scholar Ibn al-Haytham was probably the best-known medieval authority to write on it extensively; Latin translations of his work inspired European scientists from Roger Bacon to Leonardo da Vinci. Aside from the symbolism of an upside-down Gawain (and when he sees the portrait again during the ‘fall of Camelot’, it is right-side-up, representing that Gawain himself is in an upside-down world), this presents a subtle challenge to the prevailing Eurocentric imagination of the medieval world, and draws on other global influences.

As for gender, we have briefly touched on it above; in the original SGGK, Gawain’s entire journey is revealed to be just a cruel trick of Morgan Le Fay, simply trying to destabilize Arthur’s court and upset his queen. (Morgan is the old blindfolded woman who appears in the Lord and Lady’s castle and briefly approaches Gawain, but her identity is never explicitly spelled out.) This is, obviously, an implicitly misogynistic setup: an evil woman plays a trick on honorable men for the purpose of upsetting another woman, the honorable men overcome it, the hero survives, and everyone presumably lives happily ever after (at least until Mordred arrives).

Instead, by plunging the outcome into doubt and the hero into a much darker and more fallible moral universe, TGK shifts the blame for Gawain’s adventure and ultimate fate from Morgan to Gawain himself. Likewise, Guinevere is not the passive recipient of an evil deception but in a way, the catalyst for the whole thing. She breaks the seal on the Green Knight’s message with a weighty snap; she becomes the oracle who reads it out, she is alarming rather than alarmed, she disrupts the complacency of the court and silently shows up all the other knights who refuse to step forward and answer the Green Knight’s challenge. Gawain is not given the ontological reassurance that it’s just a practical joke and he’s going to be fine (and thanks to the unresolved ending, neither are we). The film instead takes the concept at face value in order to push the envelope and ask the simple question: if a man was going to be actually-for-real beheaded in a year, why would he set out on a suicidal quest? Would you, in Gawain’s place, make the same decision to cast aside the enchanted belt and accept your fate? Has he made his name, will he be remembered well? What is his legacy?

Indeed, if there is any hint of feminine connivance and manipulation, it arrives in the form of the implication that Gawain’s mother has deliberately summoned the Green Knight to test her son, prove his worth, and position him as his childless uncle’s heir; she gives him the protective belt to make sure he won’t actually die, and her intention all along was for the future shown in the epilogue to truly play out (minus the collapse of Camelot). Only Gawain loses the belt thanks to his cowardice in the encounter with the scavengers, regains it in a somewhat underhanded and morally questionable way when the Lady is attempting to seduce him, and by ultimately rejecting it altogether and submitting to his uncertain fate, totally mucks up his mother’s painstaking dynastic plans for his future. In this reading, Gawain could be king, and his mother’s efforts are meant to achieve that goal, rather than thwart it. He is thus required to shoulder his own responsibility for this outcome, rather than conveniently pawning it off on an “evil woman,” and by extension, the film asks the question: What would the world be like if men, especially those who make war on others as a way of life, were actually forced to face the consequences of their reckless and violent actions? Is it actually a “game” in any sense of the word, especially when chivalric literature is constantly preoccupied with the question of how much glorious violence is too much glorious violence? If you structure social prestige for the king and the noble male elite entirely around winning battles and existing in a state of perpetual war, when does that begin to backfire and devour the knightly class – and the rest of society – instead?

This leads into the central theme of Gawain’s relationships with the Lord and Lady, and how they’re treated in the film. The poem has been repeatedly studied in terms of its latent (and sometimes… less than latent) queer subtext: when the Lord asks Gawain to pay back to him whatever he should receive from his wife, does he already know what this involves; i.e. a physical and romantic encounter? When the Lady gives kisses to Gawain, which he is then obliged to return to the Lord as a condition of the agreement, is this all part of a dastardly plot to seduce him into a kinky green-themed threesome with a probably-not-human married couple looking to spice up their sex life? Why do we read the Lady’s kisses to Gawain as romantic but Gawain’s kisses to the Lord as filial, fraternal, or the standard “kiss of peace” exchanged between a liege lord and his vassal? Is Gawain simply being a dutiful guest by honoring the bargain with his host, actually just kissing the Lady again via the proxy of her husband, or somewhat more into this whole thing with the Lord than he (or the poet) would like to admit? Is the homosocial turning homoerotic, and how is Gawain going to navigate this tension and temptation?

If the question is never resolved: well, welcome to one of the central medieval anxieties about chivalry, knighthood, and male bonds! As I have written about before, medieval society needed to simultaneously exalt this as the most honored and noble form of love, and make sure it didn’t accidentally turn sexual (once again: how much male love is too much male love?). Does the poem raise the possibility of serious disruption to the dominant heteronormative paradigm, only to solve the problem by interpreting the Gawain/Lady male/female kisses as romantic and sexual and the Gawain/Lord male/male kisses as chaste and formal? In other words, acknowledging the underlying anxiety of possible homoeroticism but ultimately reasserting the heterosexual norm? The answer: Probably?!?! Maybe?!?! Hell if we know??! To say the least, this has been argued over to no end, and if you locked a lot of medieval history/literature scholars into a room and told them that they couldn’t come out until they decided on one clear answer, they would be in there for a very long time. The poem seemingly invokes the possibility of a queer reading only to reject it – but once again, as in the question of which canon we end up in at the film’s end, does it?

In some lights, the film’s treatment of this potential queer reading comes off like a cop-out: there is only one kiss between Gawain and the Lord, and it is something that the Lord has to initiate after Gawain has already fled the hall. Gawain himself appears to reject it; he tells the Lord to let go of him and runs off into the wilderness, rather than deal with or accept whatever has been suggested to him. However, this fits with film!Gawain’s pattern of rejecting that which fundamentally makes him who he is; like Peter in the Bible, he has now denied the truth three times. With the scavengers he denies being a knight; with the Lady he denies knowing about courtly love; with the Lord he denies the central bond of brotherhood with his fellows, whether homosocial or homoerotic in nature. I would go so far as to argue that if Gawain does die at the end of the film, it is this rejected kiss which truly seals his fate. In the poem, the Lord and the Green Knight are revealed to be the same person; in the film, it’s not clear if that’s the case, or they are separate characters, even if thematically interrelated. If we assume, however, that the Lord is in fact still the human form of the Green Knight, then Gawain has rejected both his kiss of peace (the standard gesture of protection offered from lord to vassal) and any deeper emotional bond that it can be read to signify. The Green Knight could decide to spare Gawain in recognition of the courage he has shown in relinquishing the enchanted belt – or he could just as easily decide to kill him, which he is legally free to do since Gawain has symbolically rejected the offer of brotherhood, vassalage, or knight-bonding by his unwise denial of the Lord’s freely given kiss. Once again, the film raises the overall thematic and moral question and then doesn’t give one straight (ahem) answer. As with the medieval anxieties and chivalric texts that it is based on, it invokes the specter of queerness and then doesn’t neatly resolve it. As a modern audience, we find this unsatisfying, but once again, the film is refusing to conform to our expectations.

As has been said before, there is so much kissing between men in medieval contexts, both ceremonial and otherwise, that we’re left to wonder: “is it gay or is it feudalism?” Is there an overtly erotic element in Gawain and the Green Knight’s mutual “beheading” of each other (especially since in the original version, this frees the Lord from his curse, functioning like a true love’s kiss in a fairytale). While it is certainly possible to argue that the film has “straightwashed” its subject material by removing the entire sequence of kisses between Gawain and the Lord and the unresolved motives for their existence, it is a fairly accurate, if condensed, representation of the anxieties around medieval knightly bonds and whether, as Carolyn Dinshaw put it, a (male/male) “kiss is just a kiss.” After all, the kiss between Gawain and the Lady is uncomplicatedly read as sexual/romantic, and that context doesn’t go away when Gawain is kissing the Lord instead. Just as with its multiple futurities, the film leaves the question open-ended. Is it that third and final denial that seals Gawain’s fate, and if so, is it asking us to reflect on why, specifically, he does so?

The film could play with both this question and its overall tone quite a bit more: it sometimes comes off as a grim, wooden, over-directed Shakespearean tragedy, rather than incorporating the lively and irreverent tone that the poem often takes. It’s almost totally devoid of humor, which is unfortunate, and the Grim Middle Ages aesthetic is in definite evidence. Nonetheless, because of the comprehensive de-historicizing and the obvious lack of effort to claim the film as any sort of authentic representation of the medieval past, it works. We are not meant to understand this as a historical document, and so we have to treat it on its terms, by its own logic, and by its own frames of reference. In some ways, its consistent opacity and its refusal to abide by modern rules and common narrative conventions is deliberately meant to challenge us: as before, when we recognize Arthur, Merlin, the Round Table, and the other stock characters because we know them already and not because the film tells us so, we have to fill in the gaps ourselves. We are watching the film not because it tells us a simple adventure story – there is, as noted, shockingly little action overall – but because we have to piece together the metatext independently and ponder the philosophical questions that it leaves us with. What conclusion do we reach? What canon do we settle in? What future or resolution is ultimately made real? That, the film says, it can’t decide for us. As ever, it is up to future generations to carry on the story, and decide how, if at all, it is going to survive.

(And to close, I desperately want them to make my much-coveted Bisclavret adaptation now in more or less the same style, albeit with some tweaks. Please.)

Further Reading

Ailes, Marianne J. ‘The Medieval Male Couple and the Language of Homosociality’, in Masculinity in Medieval Europe, ed. by Dawn M. Hadley (Harlow: Longman, 1999), pp. 214–37.

Ashton, Gail. ‘The Perverse Dynamics of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’, Arthuriana 15 (2005), 51–74.

Boyd, David L. ‘Sodomy, Misogyny, and Displacement: Occluding Queer Desire in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’, Arthuriana 8 (1998), 77–113.

Busse, Peter. ‘The Poet as Spouse of his Patron: Homoerotic Love in Medieval Welsh and Irish Poetry?’, Studi Celtici 2 (2003), 175–92.

Dinshaw, Carolyn. ‘A Kiss Is Just a Kiss: Heterosexuality and Its Consolations in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’, Diacritics 24 (1994), 205–226.

Kocher, Suzanne. ‘Gay Knights in Medieval French Fiction: Constructs of Queerness and Non-Transgression’, Mediaevalia 29 (2008), 51–66.

Karras, Ruth Mazo. ‘Knighthood, Compulsory Heterosexuality, and Sodomy’ in The Boswell Thesis: Essays on Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, ed. Matthew Kuefler (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), pp. 273–86.

Kuefler, Matthew. ‘Male Friendship and the Suspicion of Sodomy in Twelfth-Century France’, in The Boswell Thesis: Essays on Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, ed. Matthew Kuefler (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), pp. 179–214.

McVitty, E. Amanda, ‘False Knights and True Men: Contesting Chivalric Masculinity in English Treason Trials, 1388–1415,’ Journal of Medieval History 40 (2014), 458–77.

Mieszkowski, Gretchen. ‘The Prose Lancelot's Galehot, Malory's Lavain, and the Queering of Late Medieval Literature’, Arthuriana 5 (1995), 21–51.

Moss, Rachel E. ‘ “And much more I am soryat for my good knyghts’ ”: Fainting, Homosociality, and Elite Male Culture in Middle English Romance’, Historical Reflections / Réflexions historiques 42 (2016), 101–13.

Zeikowitz, Richard E. ‘Befriending the Medieval Queer: A Pedagogy for Literature Classes’, College English 65 (2002), 67–80.

#the green knight#the green knight meta#sir gawain and the green knight#medieval literature#medieval history#this meta is goddamn 5.2k words#and has its own reading list#i uh#said i had a lot of thoughts?

2K notes

·

View notes

Link

Forge your legacy in the award-winning setting of the Iron Kingdoms with the celebrated 5th edition roleplaying game rules.

(Delivering September 2021)

Embark upon a journey of adventure and intrigue in a world where steam power and gunpowder meet sword and sorcery. Armed with mechanika and accompanied by mighty steamjacks, explore the soot-covered cities of the Iron Kingdoms and the aftermath of the otherworldly invasion of the infernals.

Take on the persona of unique character classes, like the gun mage, who combines powerful magic with a deadly acumen for firearms, or the steamjack-commanding warcaster, who can command 10-ton autonomous machines of war with just a thought. Explore a fantastic world rebuilding itself after an apocalypse as it marches onward with its industrial revolution.

The Iron Kingdoms possess a rich history—and a tumultuous future—full of unique monsters, deities, heroes, and villains.

More than a thousand years ago, the land that is now called the Iron Kingdoms was western Immoren, a mire of warring human city-states. Then came the Orgoth, conquest-driven imperialists from beyond the sea who laid low the cities of man with forbidden magic and changed the face of western Immoren forever. The Orgoth Empire occupied the land for six hundred years before the people of Immoren banded together to defeat the invaders and drive them back across the sea from whence they came. While the rebel armies kept the peace, their leaders convened in a city called Corvis. This Council of Ten drafted the Corvis Treaties after weeks of furious debate, and the Iron Kingdoms were born.

Strictly speaking, the term “Iron Kingdoms” refers to the lands of humanity, those five kingdoms that signed the Corvis Treaties: Cygnar, Khador, Llael, Ord, and the Protectorate of Menoth. Other nations of western Immoren are commonly included in that description, although they took no part in the treaties. In the frigid north is the dwarven kingdom of Rhul. To the northeast lies the mysterious homeland of the elves, Ios. The last kingdom informally included when speaking of the “Iron Kingdoms” is the hostile island nation of Cryx, ruled over by Lord Toruk, the Dragonfather. All these nations—and many more—share the continent of Immoren.

The Orgoth were driven from western Immoren more than four hundred years ago, but the decisions made during the rebellion still echo through the world. There are many strange legends from the last days of that war—tales of dark, mysterious allies who helped drive off the invaders. Some say it would have been impossible to defeat the Orgoth without this help, that the rebel leaders had to make dangerous deals with infernal powers. These tales have proven true, and the Iron Kingdoms have recently been irrevocably changed by the Claiming, an attempt by these infernal creatures to take the payment they have long been owed—an unfathomable number of souls.

Full. Metal. Fantasy.

Delve into the award-winning world of the Iron Kingdoms with the latest edition of the Iron Kingdoms Role Playing Game from Privateer Press. Iron Kingdoms: Requiem combines this fantastic setting with the newest edition of the world’s most popular roleplaying game.

Inside this book you’ll find the history of the Iron Kingdoms and information describing the current state of the world following the Claiming. Alongside these chapters is an extensive gazetteer providing detailed information on the most notable of the world’s unique and fascinating locations.

When making a character, you’ll be able to choose from many of the familiar countries and cultures of the setting. Whether you want to be a human, gobber, trollkin, Rhulic dwarf, ogrun, Iosan, or Nyss elf, this book provides all the rules that make these different peoples unique. When choosing a class, there are options for many you’re already familiar with, from the stalwart man-at-arms fighter to the free-flowing monk of the Order of the Fist. Beyond these are brand new rules for playing the characters that make the Iron Kingdoms such a memorable setting. These new classes include, among others, gun mages, arcane mechanics, combat alchemists, and warcasters.

Alongside these options are new feats, spells, and backgrounds to make your characters feel even more a part of the world of the Iron Kingdoms.

Finally, within the pages of Iron Kingdoms: Requiem are extensive rules for the arcane technologies of the setting. These rules cover subjects from firearms and mechanika, like the galvanic arms and armor of the storm knight, to the mighty warjacks that accompany warcasters into battle.

"Before the Iron Kingdoms became a land dominated by industry and machines, it was the monsters that defined it."

— Professor Viktor Pendrake, author of the Monsternomicon

In the Iron Kingdoms peril lurks at every turn, as fearsome and terrifying creatures both great and small look to turn unwary adventurers into their next meal or enslave them beyond death. From ferocious packs of ravenous burrow-mawgs to deadly ethereal pistol wraiths that haunt the back roads and forgotten cemeteries, and the fiendish Infernals that still stalk the shadows, the Monsternomicon is filled with creatures both mundane and supernatural to challenge even the most experienced adventuring parties.

This legendary tome includes over 80 monsters, new and old, steeped in over 20 years of worldbuilding, now appearing for the first time with 5th Edition rules.

Click to go to the Update featuring these two preview pages.

Discover the origins of the legend that started it all...

Twenty-one years ago, the Iron Kingdoms was introduced through an acclaimed series of adventures known as The Witchfire Trilogy. Now, the legend continues in the newest edition of the Iron Kingdoms RPG, written for 5e.

A girl, a sword, and a secret...

As a child, she lost everything when her mother was wrongfully executed for witchcraft and her soul was consumed by the most ancient of all weapons, the black blade known as the Witchfire. Hellbent to spare her mother an eternity of torture, Alexia Ciannor stole the accursed sword and set out to unlock its dark secrets. With the voices of the Witchfire's imprisoned souls raging in her mind, Alexia would eventually unlock the power of the Infernal artifact and command an army of undead to vanquish the villains seeking to use the sword to once again subjugate the Iron Kingdoms.

Nearly two decades later, the veteran of countless wars, Alexia returns to Corvis, the City of Ghosts, in search of help from the malignant forces that seek the return of the coveted sword. The Witchfire's true purpose is finally revealed, and only the courage and sacrifice of a small group of unlikely heroes can save Alexia from the brink of madness and prevent the infernal weapon from fulfilling its apocalyptic legacy.

The Legend of the Witchfire adventure will take players from level 1 to level 4, and is the perfect introduction to the action-packed and intrigue-filled world of the Iron Kingdoms!

==============================================

Kickstarter campaign ends: Fri, February 12 2021 7:59 AM UTC +00:00

Website: [Privateer Press] [facebook] [twitter] [instagram]

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

WOT Read Along Context

I’m really excited that people actually seem interested in this Wheel of Time reaction series. I don’t know anything about the online fandom because as someone who has barely started the series, I feel like the risk of spoilers is just too high to go poking around fandom just yet.

Just so everyone has an idea how this might go, I plan on posting my Eye of the World prologue reactions within the next few hours, and will try to post a chapter every 2-3 days. The schedule may vary however depending on the length of the chapters and what’s going on in my life. If there’s going to be a slow down or pause, I’ll let you know, but I am planning on trying to do all 15 books. It just may take a while.

For some background, I love fantasy, but have usually been more drawn to urban fantasy, instead of the classic sword and sorcery style. I’m trying to expand my reading comfort zone, so to speak, and have heard great things about Wheel of Time. It seems to be one of the bigger name series in the fantasy genre, and since I’m trying to get better versed in all aspects of fantasy, decided to start with Wheel of Time.

I’ll admit I don’t know a lot about the series at this point. I know there are 14 books plus some sort of prequel. It apparently has a deep mythology, and great world building which sounds fun. One criticism is that the author can get a little wordy at times, which doesn’t seem all that surprising given that book 1 alone is over 600 pages. And that it’s popular enough that even Google autofill can spoil you.

I’m really looking forward to going on this journey, and I hope that anyone who chooses to go on the journey with me has as much fun as I’m hoping to have!

26 notes

·

View notes

Text