#Priscian

Text

youtube

0 notes

Text

Irish scribes & margins

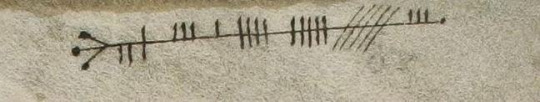

Found in the margin of a ninth-century copy of Institutiones grammaticae by Priscian by Irish scribes; marginal note in ogham script that reads Ale [Lait] + killed [ort], i.e. an ale-induced hangover. St Gall, Cod. Sang. 904, p. 204. CC-BY-NC

‘the cat has gone astray’

Leabar Breac, RIA MS p. 164. Historical miscellany.

‘blood from the finger of Maelaghlin’

Note beside a blood stain, Dublin, Kings Inns MS 16, fol 5v. 16th century Irish medical text.

‘New parchment, bad ink, O I say nothing more’

St Gallen Priscian St Gall, Cod. Sang. 904, p. 214.

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is customary to think of the Renaissance as a time of great flowering. There is no doubt that linguistic and philological developments of this period are interesting and significant. Two new sets of data that modern linguists tend to take for granted became available to grammarians during this period: (1) the newly recognized vernacular languages of Europe, for the protection and cultivation of which there subsequently arose national academies and learned institutions that live down to the present day; and (2) the languages of Africa, East Asia, the New World, and, later, of Siberia, Central Asia, New Guinea, Oceania, the Arctic, and Australia, which the voyages of discovery opened up. Earlier, the only non-Indo-European grammar at all widely accessible was that of the Hebrews (and to some extent Arabic); Semitic in fact shares many categories with Indo-European in its grammar. Indeed, for many of the exotic languages, scholarship barely passed beyond the most rudimentary initial collection of word lists; grammatical analysis was scarcely approached.

In the field of grammar, the Renaissance did not produce notable innovation or advance. Generally speaking, there was a strong rejection of speculative grammar and a relatively uncritical resumption of late Roman views (as stated by Priscian). This was somewhat understandable in the case of Latin or Greek grammars, since here the task was less evidently that of intellectual inquiry and more that of the schools, with the practical aim of gaining access to the newly discovered ancients. But, aside from the fact that, beginning in the 15th century, serious grammars of European vernaculars were actually written, it is only in particular cases and for specific details (e.g., a mild alteration in the number of parts of speech or cases of nouns) that real departures from Roman grammar can be noted. Likewise, until the end of the 19th century, grammars of the exotic languages, written largely by missionaries and traders, were cast almost entirely in the Roman model, to which the Renaissance had added a limited medieval syntactic ingredient.

From time to time a degree of boldness may be seen in France: Petrus Ramus, a 16th-century logician, worked within a taxonomic framework of the surface shapes of words and inflections, such work entailing some of the attendant trivialities that modern linguistics has experienced (e.g., by dividing up Latin nouns on the basis of equivalence of syllable count among their case forms). In the 17th century a group of Jansenists (followers of the Flemish Roman Catholic reformer Cornelius Otto Jansen) associated with the abbey of Port-Royal in France produced a grammar that has exerted noteworthy continuing influence, even in contemporary theoretical discussion. Drawing their basic view from scholastic logic as modified by rationalism, these people aimed to produce a philosophical grammar that would capture what was common to the grammars of languages—a general grammar, but not aprioristically universalist. This grammar attracted attention from the mid-20th century because it employs certain syntactic formulations that resemble rules of modern transformational grammar.

Roughly from the 15th century to World War II, however, the version of grammar available to the Western public (together with its colonial expansion) remained basically that of Priscian with only occasional and subsidiary modifications, and the knowledge of new languages brought only minor adjustments to the serious study of grammar. As education became more broadly disseminated throughout society by the schools, attention shifted from theoretical or technical grammar as an intellectual preoccupation to prescriptive grammar suited to pedagogical purposes, which started with Renaissance vernacular nationalism. Grammar increasingly parted company with its older fellow disciplines within philosophy as they moved over to the domain known as natural science, and technical academic grammatical study increasingly became involved with issues represented by empiricism versus rationalism and their successor manifestations on the academic scene.

Nearly down to the present day, the grammar of the schools has had only tangential connections with the studies pursued by professional linguists; for most people prescriptive grammar has become synonymous with “grammar,” and the prevailing view held by educated people regards grammar as an item of folk knowledge open to speculation by all, and in nowise a formal science requiring adequate preparation such as is assumed for chemistry.

This is Eric P Hamp in the Britannica. Hamp (1920 - 2019) was of the same generation as Burgess (1917 - 1993), educated in philology around the time of the World Wars. This is the generation suceeding that of Tolkien (1892 - 1973).

I have highlighted two bits of temporal deixis. He sees, correctly, there having been a sort of scientific watershed around the period of the Wars.

"Nearly down to the present day" I interpret as being more metaphorical than temporal -- the hope of the postwar scientists was that in "the present day" of peace, the bright light of linguistic science would illuminate the world more than tangentially. Since he lived to 2019 he will have been well aware that this failed to happen despite his efforts, and therefore the Priscian darkness continues to hang around -- but "nearly" almost not.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shopee Lucrativo por Prisciane Pereira - "Como ganhar dinheiro na Shopee" Onde encontrar?

Para quem deseja explorar todo o potencial da Shopee e se destacar nesse mercado competitivo, o curso Método Shopee Lucrativo, criado por Prisciane Pereira, é a solução ideal. Você pode encontrar o curso disponível para compra no site oficial da Prisciane Pereira. CUPOM DESCONTO JÁ APLICADO NO LINK

Para que é indicado e para o que serve?

O Método Shopee Lucrativo é indicado para empreendedores…

0 notes

Text

Anco ,anche LT. Die "ook" twee vorme in Botswana gebruik hulle meer van die anco en hier meer van die anche wissel mekaar af in Dante se leksikon sonder oënskynlike differensiasie van funksie of betekenis, in prosa en in poësie, in rym al dan nie, geplaas voor of na die elemente van die sin waarna hulle verwys, of daarvan geskei met die tussenplasing van ander woorde, aan die begin van die tydperk of in 'n tussenposisie, dikwels voorafgegaan deur die voegwoord en 'altyd volgens 'n keuse of stylisties: ‛, soms in styl. Voorbeelde kom terug met oorvloed as 'n voegwoord wat 'n diskoers hervat of voortsit, wat ander dinge byvoeg by wat reeds gesê is, dit wil sê met die waarde van “ buitendien “, “ suiwer “: L'angs, wat nie van binne verstaan nie, spira / uit die mond ... / e anche a li occhi lor merito weergee (Rime CVI); En laat die arme vulgêre selfs nie deur hierdie woord mislei word nie (Cv II X 7); En hierdie figuur in retoriek is baie lofwaardig, en selfs nodig (III X 6); Priscian sen va con quel turba grama, / en Francesco d'Accorso ook (If XV 110), waar die bepaalde energie wat die sin gee die uitgestelde en finale posisie van die a. (in die 1921-uitgawe wysig die verskil in leestekens - en Francesco d'Accorso; ook vedervi / ... quelo potei - die betekenis van die sin, maar verander nie die waarde van die voegwoord nie); Ek hou ook hiervan / omdat jy dit onderskei deur na God te kyk (Pd VIII 89); Maar hulle was nie eens haatlik nie (Fiore XCV 6).

Ander voorbeelde in Vn XV 3, XIX 16, XXIV 5, XXXVI 3; CV II II 4, VI 9, XIII 5, III V 12 (twee voorbeelde), V 20, IX 12, XIII 5, IV V 5, IX 3 en 7, XIV 2, XXII 15, XXV 11, XXVIII 11 en 14; Indien VII 33 en 117, XII 2, XVIII 96, XXII 73 en 86, XXVIII 77 en 106, Bl VII 124, XII 60, XXIX 69, XXXIII 76, Pd XI 34, XXIX 43, XXXII 47; Blom LXXXIII 10). In die obskure gedeelte van Cv IV XV 9 [waarvan] die sinne anco [nie] teen [is] nie, is dit nie moontlik om te erken of dit hierdie waarde het nie, of eerder dié van "weer" (sien die kommentaar deur Busnelli-Vandelli).

Met die betekenis van " bowendien ", " verder ", " daarby ", nie verskillend van die vorige een nie, word dit dikwels aan die begin van 'n sin of sin aangetref, of verwys in elk geval nie na 'n enkele element van die proposisie nie, maar na die hele sin, of ten minste na die werkwoord, met die veronderstelling in sulke gevalle 'n bepaalde versterkende waarde, soos in Vn XXV 2 Dico anche; Cv I XIII 6 Ook was hy saam met my op dieselfde studie, en dit kan ek so aantoon; Bl III 144 Kyk vandag of jy my gelukkig kan maak, / deur te openbaar ... / soos jy my gesien het, en ook hierdie verbod; Pd XIX 10 Ek het die rostrum gesien en ook hoor praat; XXIV 129 wil jy hê dat ek / hier die vorm van my bereidwillige geloof moet openbaar, / en ook die oorsaak van hom wat jy gevra het. Flower CCXIII 7 Paura daardie kudde het gewen, / en ook 'n ander, as daar was; sien ook Vn XV 8, XXIV 4, XXV 2, XXVI 9; Cv I II 17, VII 13, XIII 8, II IV 7, X 7, III II 11, V 18 (Dit is ook raadsaam dat ek dit omkring...), X 9, XI 8 (twee keer), XIII 14, IV XXVII 10, 12 en 16; Pd XXI 31; Blom LIII 4, CLII 7.

'n Enkele voorbeeld van 'n kontraposisionele konstruksie word in Pd XXIV 135 gedokumenteer in so 'n oortuiging dat ek geen bewyse / fisies en metafisies het nie, maar ek gee / ook die waarheid dat dit hier reën / vir Moïsè, vir profete en vir psalms.

Op twee plekke van die Fiore, voorafgegaan deur die bywoord ‛ non ', verkry dit die waarde van "nie een nie", "nie eens nie": 'n ben far non fu anche kennismaking (CXCIII 7), en 'non also done verontwaardiging (CXCVII 12).

Voorafgegaan deur die werkwoord ‛ krag, dit versterk die konmissiewe waarde daarvan in Cv III IX 13 Dit kan egter ook so lyk vir die visuele orgaan, dit is die oog, en IX 15 En daarom kan die ster ook versteur lyk.

Aan die kant van Bl XXX 56 Dante, sodat Vergilius kan weggaan, / moenie weer huil nie, moenie weer huil nie; / aangesien huil vir 'n ander swaard vir jou gepas is, gee die meeste tolke die waarde van "weer", en die herhaling van die bywoord anker, gekombineer met dié van die werkwoord ween, is baie effektief in die eerste woorde, van verwyt, wat Beatrice aan haar minnaar spreek wat nie altyd aan haar getrou gebly het nie: om haar weer te sien, hy sou eerder uit sy verlede gelyk het om 'n skaamte te hê om te c, sou ook vir Beatrice gepas het, meer welkom was as om te huil vir Vergilius se verlating. Maar miskien selfs meer oortuigend is Cesari se verduideliking: “ ‛ Moenie so haastig wees om hieroor te huil nie: iets anders wag op jou. En hier is die anker wat gebruik word vir 'so badass'”. Verder, onmiddellik nadat sy die diskoers (v. 73) met innige opgewondenheid hervat het, versterk Beatrice weer die woorde deur dit te herhaal: Kyk mooi na ons! Wel ek is, wel ek is Beatrice. Ander kommentators sien in die konstruk anco... weer 'n opskorting van die diskoers en dus die hervatting daarvan (Lombardi), of hulle gee liewer aan anco die waarde van "ook", "vir meer", "bykomend", wat die onvanpasheid, op daardie oomblik, van daardie geween onderstreep, en sien in anco die dringende vermaning om op te hou (Mattalia).

0 notes

Video

youtube

Liked on YouTube: What Do We Mean by Hermetic? How the early printing of the Hermetica Shaped our Idea of Hermeticism || https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7JDEP3y9SdY || "Hermeticism" and "Hermetic" are exceedingly elastic concepts capturing a wide and disparate range of ideas - what explains the conceptual elasticity of the concept of something being "hermetic." This episode offers a suggestion that the some of the valances of the term are literally bound up with the texts that were often printed alongside the Corpus Hermeticum. Thus by exploring the printing history of the Corpus Hermeticum we may come to better understand how we conceive of what is and is not 'hermetic.' Consider Supporting Esoterica! Patreon - https://ift.tt/eTKcdkZ Paypal Donation - https://ift.tt/fNwR5OF Merch - https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCoydhtfFSk1fZXNRnkGnneQ/store @TheModernHermeticist - Is the Kybalion Really Hermetic? - https://youtu.be/7rCF6vSeZ3k Sam Block on the Kybalion - https://ift.tt/TiXoZEB 1497 - https://ift.tt/U5QbXi0 1516 - https://ift.tt/TNMDVRC 1532 - https://ift.tt/qhutaXe 1549 - https://ift.tt/Sw2s5zY 1497 Reading List: 1) 'On the mysteries of the Aegyptians, Chaldeans, and Assyrians' by Iamblichus (250-325 CE) (Iamblichus de mysteriis Aegyptiorum. Chaldærum. Assyriorum); 2) 'Commentary on Plato's Alcibiades – on the soul and daimones' by Proclus (412-84 CE) (Proclus in alcibiadem de anima atque dæmone); 3) 'On sacrifice and magic' by the same author (Proclus de sacrificio et magia); 4) 'On deities and daimons' by Porphyrius (c 234-c. 304 CE) (Porphyrius de diuinis atque dæmonibus); 5) 'On dreams' by Synesius (5th century CE) (Synesius Platonicus de somniis); 6) 'On daimons' by Michael Psellus (1018-78 CE) (Psellus de dæmonibus); 7) 'The commentary on Theophrastos's On the senses' by Priscian (6th century CE) and Marsilius (Expositio Prisciani et Marsilii in Theophrastum de sensu. phantasia et intellectu); 8) 'An introduction to the Philosophy of Plato' by Alcinus (2nd century CE) (Alcinoi philosophi liber de doctoria Platonis); 9) 'On Plato's Definitions' by Speusippos, Plato's disciple, (407 BCE-339 BCE) (Speusippi Platonis discipuli liber de Platonis difinitionibus); 10) 'Maxims' and 'Symbols' by Pythagoras (560 BCE-480 BCE) (Pythagoræ philosophi aurea uerba; Symbola); 11) 'On Death' by Xenocrates (c. 396 BCE-34 BCE) (Xenocratis philosophi platonici liber de morte); and 12) 'On pleasure' by Marcilius Ficino (Marcilius ficini liber de uoluptate). 16th Century Reading List: 1) 'On the mysteries of the Aegyptians, Chaldeans, and Assyrians' by Iamblichus (250-325 CE) (Iamblichus de mysteriis Aegyptiorum. Chaldærum. Assyriorum); 2) 'Commentary on Plato's Alcibiades – on the soul and daimones' by Proclus (412-84 CE) (Proclus in alcibiadem de anima atque dæmone); (see O’Neill translation) 3) 'On sacrifice and magic' by the same author (Proclus de sacrificio et magia); 4) 'On deities and daimons' by Porphyrius (c 234-c. 304 CE) (Porphyrius de diuinis atque dæmonibus); 5) 'On daimons' by Michael Psellus (1018-78 CE) (Psellus de dæmonibus) 6) 'Corpus Hermeticum, Asclepius' by Hermes Trismegistus (early c's CE) (Mercurii Trismegisti Pimander. Eiusdem Asclepius)

0 notes

Text

youtube

No vídeo de hoje, trazemos uma análise completa do Método Shopee Lucrativo desenvolvido pela renomada especialista em e-commerce, Prisciane Pereira. Você está curioso para saber se esse método realmente funciona e pode impulsionar seus resultados no Shopee? Então, você está no lugar certo!

Nossa revisão imparcial abordará todos os detalhes essenciais desse método inovador. Descubra como a Prisciane Pereira utiliza estratégias eficazes para obter lucros sólidos no Shopee, e como você pode aplicá-las em seu próprio negócio.

0 notes

Text

"OMG I'm So Hungover" - Ogham Annotations in a 9th century copy of Priscian

“OMG I’m So Hungover” – Ogham Annotations in a 9th century copy of Priscian

The Anglandicus blog has an amusing 2014 article on Massive Scribal Hangovers: One Ninth Century Confession. The whole post is well worth a read on Irish marginal notes in manuscripts.

One such manuscript has a great number of these marginalia. Below is the upper portion of folio 204 in St. Gall 904 (or Codex Sangallensis 204, if we choose to be formal). This was written in Ireland in 851 AD. …

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

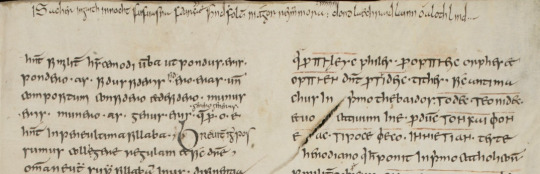

#ManuscriptMonday: The oldest complete manuscript in Special Collections, a copy of Priscian's De Constructione written at Lambach Abbey in Austria sometime in the middle of the 12th century.⠀ ⠀ PA6642 .A4 1150 ⠀ ⠀ #manuscript #manuscripts #medievalmanuscripts #latin #grammar #priscian #lambach #handwritten #calligraphy #medieval #middleages #rarebooks #specialcollections #libraries #librariesofinstagram #iglibraries #universityofmissouri #ellislibrary #columbiamo (at Ellis Library)

#middleages#iglibraries#medievalmanuscripts#ellislibrary#manuscript#lambach#columbiamo#grammar#rarebooks#latin#specialcollections#calligraphy#medieval#universityofmissouri#manuscripts#manuscriptmonday#priscian#libraries#librariesofinstagram#handwritten

111 notes

·

View notes

Photo

from page 112 of a mid-ninth century manuscript of Priscian’s Institutes of Grammar; at the top of this page is a poem written by an Irish monk. Source. English translation by Kuno Meyer.

Original Irish

Is acher ingáith innocht

fufuasna faircggae findḟolt

ni ágor réimm mora minn

dondláechraid lainn oua lothlind

English Translation

Bitter is the wind tonight;

It tosses the ocean’s white hair.

Tonight I fear not the fierce warriors of Norway

Coursing on the Irish sea.

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today's #ManuscriptOfTheDay is Ms. Codex 1243, a 13th c. copy of parts of Priscian's Institutiones grammaticae, also known as De constructione, a guide to Latin grammar popular in Medieval Europe. There are extensive annotations, as here on f. 5v #medieval #manuscript #france #french #latin #gloss #annotation #grammar #syntax #bookhistory #bookstagram #librariesofinstagram https://instagr.am/p/CXgsZChsaYZ/

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yield Loose Chippings

‘A hedge of trees surrounds me: a blackbird’s lay sings to me –

praise which I will not hide –

above my booklet the lined

one the trilling of the birds sings to me.

In the grey mantle of the beautiful chant

sings to me from the top of the bushes:

may the Lord protect me from Doom.

I write under the greenwood’.

Day of arrangements comes round quick:

ecg. dazzlertron trials. q & a penury…

all in…

View On WordPress

#Beehive Hairdos#Cod. Sang. 904#Especially When the October Wind#p. 203. Ninth-century copy of Institutiones grammaticae by Priscian by Irish scribes.#Runesmith#St Gall

0 notes

Text

Shopee Lucrativo por Prisciane Pereira - "Como ganhar dinheiro na Shopee" Onde encontrar?

Para quem deseja explorar todo o potencial da Shopee e se destacar nesse mercado competitivo, o curso Método Shopee Lucrativo, criado por Prisciane Pereira, é a solução ideal. Você pode encontrar o curso disponível para compra no site oficial da Prisciane Pereira. CUPOM DESCONTO JÁ APLICADO NO LINK

Para que é indicado e para o que serve?

O Método Shopee Lucrativo é indicado para empreendedores…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Suffixa Nominum Agentium Sunt “-tor” et “-trix” neque “-or” et “-rix” / The Agent Noun Suffixes Are “-tor” and “-trix” and Not “-or” and “-rix”

There is the common idea that -or and -rix are the agent-noun-forming suffixes in Latin. In this essay I explain why exactly we should consider -tor and -trix the proper forms of Latin’s agent-noun-forming suffixes.

(The original version of this essay is here.)

Contents

Apparent Formation Procedures

Problems with the Apparent Formation Procedures

Feminine Agent Nouns Differ

No or Different Perfect Participles

-or and -rix Are Not Independent

No Real Derivational Link

What All This Means

Why the Suffixes Are Actually -tor and -trix

The Suffixes with Verb Stems and Roots

Verb-Suffix Interactions

Structure of Suffixes

“Families” of Suffixes

Suffixes, Parts of Verbs, and Actual Procedures

Stems Ending in Long -a-, -e-, -i-

Roots with Added Short -i-

Roots with Added Long -i-

U-Final Stems and Roots

Other Vowel-Final Roots

Consonant-Final Roots: Overview

Consonant-Final Roots: No Phonetic Changes

Consonant-Final Roots: Phonetic Change Types

Consonant-Final Roots: More about Assimilation

Consonant-Final Roots: S-Initial Suffixes

Consonant-Final Roots: The -tr- Combination

Analogical Forms with Short -i-

Compound Suffixes

Verb Roots Not Easily Discernible

What the Phonetic Concepts and Examples Show

My Idea Explains the Material Better

Examples of Words Which We Can Create

Sources

1. Apparent Formation Procedures

The Latin language has many nouns that denote the agent of an action. Examples of such words appear below (and throughout this article) in red:

altrix, “nourisher,” “one who nourishes”;

amator, “lover,” “one who loves”;

auditor, “hearer,” “one who hears”;

victrix, “winner,” “victress,” “one who is victorious.”

The agent nouns that end in -or are mostly masculine, but a few like auctor can be masculine or feminine. Those that end in -rix are all feminine.

The four agent nouns which I cited above appear to have been created by removing the -us ending of a perfect participle (p.p.) and then adding either -or or -rix to the base of the perfect participle which ends in -t. So:

altrix = alt- (from altus, p.p. of alere, “to nourish”) + -rix;

amator = amat- (from amatus, p.p. of amare, “to love”) + -or;

auditor = audit- (from auditus, p.p. of audire, “to hear”) + -or;

victrix = vict- (from victus, p.p. of vincere, “to conquer”) + -rix.

Other agent nouns appear to have been created in the same way:

actor and actrix, “driver,” “one who drives,”

actor = act- (from actus, p.p. of agere, “to drive”) + -or,

actrix = act- (from actus, p.p. of agere, “to drive”) + -rix;

rector and rectrix, “leader,” “one who leads,”

rector = rect- (from rectus, p.p. of regere, “to lead”) + -or,

rectrix = rect- (from rectus, p.p. of regere, “to lead”) + -rix.

When the base of a perfect participle ends in -s instead of -t, the -or appears to have been added to that base of that participle in the same way as usual, and so the masculine agent noun has an -s- before -or instead of -t. Moreover, the feminine agent nouns corresponding to these masculine agent nouns ending in -sor appear to have been created the same way as the other feminine agent nouns in -rix, except a -t- was added either because of euphony or because there is a -t- in words like altrix and victrix.

defensor and defenstrix, “defender,” “one who defends,”

defensor = defens- (from defensus, p.p. of defendere, “to defend”) + -or,

defenstrix = defens- (from defensus, p.p. of defendere, “to defend”) + -t- + -rix;

tonsor and tonstrix, “shearer,” “one who shears,”

tonsor = tons- (from tonsus, p.p. of tondere, “to shear”) + -or,

tonstrix = tons- (from tonsus, p.p. of tondere, “to shear”) + -t- + -rix.

We may ask ourselves: “What do the Latin grammarians themselves have to say about the formation of such agent nouns?” We can cite the Late Latin grammarian Priscian, who discusses this subject in the Partitiones:

Fac nomen verbale a participio praeteriti temporis. Armator et armatrix. Cur? Quia omnia participia praeteriti temporis us in or convertentia faciunt nomen verbale in omni coniugatione masculinum ex quo iterum or in rix mutantes facimus femininum, nisi euphonia, id est sonus, prohibeat, quod evenit in illis quae in sor desinunt ut pransor, cursor, tonsor. Nemo enim dicit pransrix, cursrix, tonsrix, propter asperitatem pronuntiationis. Unde et Terentius tonstrina dixit euphoniae causa addens contra regulam t. sicut enim a doctore doctrina consonantes eas habuit quas suum primitivum, sic debuit etiam tonstrina absque t esse nisi sonoritas coegisset. Defenstrix quoque Cicero in Timaeo protulit addita t.

Make a verbal noun from the perfect participle. Armator and armatrix. Why? Because all perfect participles, when converting -us to -or, make a masculine verbal noun in every conjugation, from which, in turn, when changing -or to -trix, we make a feminine one, unless euphony, in other words sound, prevents it, which happens in those nouns which end in -sor, as pransor, cursor, tonsor. For no one says pransrix, cursrix, tonsrix on account of the harshness of pronunciation. Because of this Terence even said tonstrina, adding -t- against the rule for the sake of euphony. For just as doctrina had gotten from doctor those consonants which its primitive had, so tonstrina also should have been without a -t- if sound had not made it a necessity. Cicero produced the word defenstrix also in the Timaeus after adding a -t-.

This passage shows us that Priscian basically agrees with the formation procedures which I discussed above. He, however, promotes the particular view that the -or nouns are created from the perfect participles of verbs while the -rix nouns are in turn created from the -or ones in the following ways:

pransor and pranstrix, “one who eats breakfast,” where

pransor came from pransus (p.p. of prandere, “to have breakfast”), and

pranstrix came from pransor;

cursor and curstrix, “runner,” where

cursor came from cursus (p.p. of currere, “to run”), and

curstrix came from cursor;

tonsor and tonstrix, “shearer,” where

tonsor came from tonsus (p.p. of tondere, “to shear”), and

tonstrix came from tonsor.

In any case, this “add -or and -rix to the participial bases” idea appears to be accurate in describing the creation of these agent nouns in Latin.

2. Problems with the Apparent Formation Procedures

That “add -or and -rix to the participial bases” idea is neat, tidy, straightforward—and wrong. I see four major problems with it.

2.A. Feminine Agent Nouns Differ

First, that idea cannot account for the forms of feminine agent nouns when both the corresponding masculine agent nouns and the corresponding participial bases show -s- or -ss- while the feminine agent nouns themselves do not also show that letter or letter combination. Some examples are:

assestrix, “assessor,” but we also have

assessor, and

assessus, p.p. of assidere, “to sit near”;

expultrix, “expeller,” but we also have

expulsor, and

expulsus, p.p. of expellere, “to expel”;

possestrix, “possessor,” but we also have

possessor, and

possessus, p.p. of possidere, “to possess.”

Since we have assessor and assessus, and possessor and possessus, the “add -or and -rix to the participial bases” idea tells us that we surely should have *assesstrix and *possesstrix instead of the existing words assestrix and possestrix. In reality, however, feminine agent nouns never end in -sstrix. While the “add -or and -rix to the participial bases” idea can account for repulstrix (the feminine of repulsor, corresponding to the perfect participle repulsus, from repellere, “to repel”), it cannot explain the feminine agent noun expultrix when the masculine agent noun expulsor and the perfect participle expulsus (from expellere, “to expel”) indicate an *expulstrix.

2.B. No or Different Perfect Participles

The second problem with the “add -or and -rix to the participial bases” idea is that it cannot account for agent nouns which either a) come from verbs that lack perfect participles or b) have different letters corresponding to the final letters of the bases of perfect participles. Some examples are:

converritor, “one who sweeps together,” where

*converritus is implied, but

conversus is the p.p. of converrere, “to sweep together”;

bibitor, “drinker,” where

*bibitus is implied, but

there is no p.p. of bibere, “to drink”;

delitor, “obliterator,” where

delitus is implied, but

deletus is the usual p.p. of delere, “to obliterate”;

favitor, “supporter,” where

*favitus is implied, but

there is no p.p. of favere, “to support,” although

fautum is the verb’s accusative supine;

fugitor, “one who flees,” where

*fugitus is implied, but

there is no p.p. of fugere, “to flee”;

libritor, “hurler,” where

*libritus is implied, but

libratus is the p.p. of librare, “to hurl.”

The “add -or and -rix to the participial bases” idea fails once again because bibere and fugere lack perfect participles, and so there is no base to which -or and -rix can attach. Converrere and librare have the participles conversus and libratus, respectively, not *converritus and *libritus, as converritor and libritor seem to suggest according to the “add -or and -rix to the participial bases” idea. Although delere does have the participle form delitus, it is by no means as commonly used as the typical form deletus. Favere does not have a perfect participle, so there is again a lack of a base to which -or and -rix can attach. But it is astounding that favere provides us with the agent nouns fautor and favitor, the former suggesting an imaginary perfect participle *fautus, which looks similar to fautum, the verb’s actual accusative supine.

Two other words are relevant here:

meretrix, “courtesan,” where

*meretus is implied, but

meritus is the p.p. of merere, “to merit”;

obstetrix, “midwife,” where

*obstetus is implied, but

there is no p.p. of obstare, “to stand before,” although

obstatum is the verb’s accusative supine.

These also either come from verbs that lack perfect participles or have different letters corresponding to the final letters of the bases of perfect participles. Merere uses the perfect participle meritus, not meretus as meretrix seems to suggest. I could not find an attestation for *obstatus as the perfect participle of obstare, but the accusative supine is obstatum and not *obstetum as one might think after looking at obstetrix and using the “add -or and -rix to the participial bases” idea to suggest a participle *obstetus. What is also interesting about the words meretrix and obstetrix is that they lack masculine forms in -or. These two words are relevant to professions that were restricted to women, so it is not likely that the masculine words existed. If such masculine words in fact did not ever exist, then these two words in -rix were created on their own without corresponding words in -or. The independent creation of these words goes against Priscian’s particular view of the “add -or and -rix to the participial bases” idea which says that the feminine agent nouns in -rix derive from the masculine ones in -or.

2.C. -or and -rix Are Not Independent

A third problem with the “add -or and -rix to the participial bases” idea is that it cannot account for the lack of clear uses of -or and -rix as entirely independent suffixes. Whenever these suffixes appear, some form of -t- or -s- (even hidden in the combination -x-) always appears right before them.

While we do have the agent nouns actor, possestrix, and converritor, we do not have *agor, *possidrix, or *converror, which we would expect to exist if the suffixes were independent. The latter three forms are not entirely farfetched when we consider that another suffix which also appears to be attached to participial bases, -io, can even be attached to the present stems of verbs. For example, regere, “to lead,” yields both rectio, “a guiding,” and regio, “a direction.” Agent nouns like *regor and *regrix therefore seem plausible, but they are not found. We have just the words rector and rectrix.

One might argue that ludor is indeed an agent noun which was created by attaching the (apparently) independent agent-noun-forming suffix -or to the present stem of the verb ludere. There are good reasons to reject this claim, however. The passage in which this ludor appears (Schol. ad Iuven. 6, 105) is unclear and doubtful. There is also the issue of whether the word actually comes from ludere. It may well derive from the noun ludus, which appears in the phrase in ludo which appears in the passage. Even if the word did come from ludere, there is the possibility that the -or is not the agent-noun-forming suffix at all. There is a suffix -or that is attached to the roots or present stems of verbs, but it is entirely different from the agent-noun-forming suffix because it forms abstract nouns, as seen in amor, “love,” from amare, “to love.” Ludor looks less like an agent noun and more like an abstract noun that means “play” or “playing.” These uncertainties concerning the suffixal identity and meaning of this ludor are enough to reject it as a clear example of -or as an independent agent-noun-forming suffix.

We have seen the suffixes -or and -rix appear in agent nouns which derive from verbs, but we should understand that they also appear in agent nouns which derive from nominal stems. When these suffixes interact with nominal stems, they never appear just as -or and -rix. They actually all have -t-:

ficitor, “fig planter” (from ficus, “fig”);

funditor, “slinger” (from funda, “sling”);

ianitor, “gatekeeper” (from ianus, “covered passageway”);

ianitrix, “gatekeeper” (from ianus, “covered passageway”);

olivitor, “olive tree planter” (from oliva, “olive”).

We do not find agent nouns like *ficor, *fundor, and *iantrix. We would surely expect these forms, or forms like it, if -or and -rix were independent suffixes attached to parts of words which are not participial bases.

Someone could argue that ficitor, funditor, ianitrix, and the others were not created by adding the suffixes to nominal bases, but actually came from attested, unattested, or imagined denominative verbs just like these three:

finitor, “limiter” (from finire, “to limit,” from finis);

gladiator, “gladiator” (from *gladiare, “to wield a sword,” from gladius);

viator, “traveller” (from viare, “to travel,” from via).

And yet there is a difference between these three agent nouns and the ones in the group which includes ficitor, funditor, and ianitrix. In finitor, gladiator, and viator, the i or a before the -tor part is long, indicating the long stem vowels used in the denominative-verb-forming suffixes -are and -ire:

finīre = fini- + denominative-verb-forming suffix -ī-re;

*gladiāre = gladio- + denominative-verb-forming suffix -ā-re;

viāre = via- + denominative-verb-forming suffix -ā-re.

Ficitor, funditor, ianitrix, and the others have a short i before the -tor part, and this -i- corresponds to no stem vowel used in any of the denominative-verb-forming suffixes. Instead, this -i- is a connecting vowel that is also sometimes found before other consonant-initial derivational suffixes which are added to nouns, as seen in words like Ianiculum (broken down into Ian-i-culum), from Ianus, and olivitas (broken down into oliv-i-tas), from oliva.

2.D. No Real Derivational Link

Finally, the “add -or and -rix to the participial bases” idea cannot explain how there is any derivational link between the agent nouns formed from these -or and -rix suffixes and the corresponding perfect participles from which those agent nouns derive. This is the case whether we want to look at this alleged derivational link either in terms of semantics or morphology.

Let us look at the semantic aspect first. While deponent verbs typically do have active perfect participles (e.g., locutus, “having spoken”), non-deponent verbs have perfect participles which are passive (e.g., amatus, “having been loved”), and yet the agent nouns always have active or causative meanings but never passive meanings. Thus, for example, the active participle locutus seems to correspond to the active-in-meaning locutor, but the passive amatus does not correspond to the active-in-meaning amator. Moreover, locutor cannot mean “he who is spoken of,” nor can amator mean “he who is loved.” The temporal significance between the agent nouns and the participles also do not match. The words do not mean, respectively, “he who has been spoken of” and “he who has been loved,” according to the perfect-tense meaning of the participles. The agent noun suffixes then have semantic meanings which are irrelevant to the significance of the perfect participles.

Now let us consider the morphological aspect. Although -or can be added to the stem of a perfect participle such that the stem vowel -o- is elided to form a typical agent noun, things are not so tidy when -rix is added to the stem of a perfect participle. When suffixes beginning with consonants are added to o-stem nouns and adjectives, there is typically a connecting vowel between the remaining part of the stem of the noun or adjective and the suffix. Thus, for example, amato- and -or can plausibly yield amator (i.e., amat-or, -o- elided), but amato- and -rix would yield *amaterix (i.e., amato-rix, -o- becoming -e- before -r-). The combination -eri- is entirely allowable in Latin (e.g., aperis), and so there would not be any need for a euphonic -t- in words like tonstrix. Neither Latin phonetics in general nor the “add -or and -rix to the participial bases” idea itself offers any rationale for that lack of -e-.

2.E. What All This Means

What then do these four problems suggest to us? My argument here is that this “add -or and -rix to the participial bases” idea must be rejected because the suffixes in Latin are not actually -or and -rix. The suffixes are in fact -tor and -trix. I shall now cite several ways to show that this is the case.

3. Why the Suffixes Are Actually -tor and -trix

That -t- element is historically a part of the suffixes -tor and -trix. Agentive nouns in Indo-European ended in either -tor or -ter (see: Miller, Latin Suffixal Derivatives in English, section 3.7). The -ter version appears in Latin within the words mater, pater, and frater, but the -tor became the basis of the -tor and -trix suffixes. Figuring out where the suffixes came from is simple enough, but in order to show that the suffixes are actually -tor and -trix, I must show how the Romans actually used them to form words.

3.A. The Suffixes with Verb Stems and Roots

Let us begin by becoming acquainted with the types of word parts to which the Romans typically attached these suffixes. While it was possible in Latin to add the agent-forming suffixes -tor or -trix to nominal stems, the suffixes were much more usually added to verb stems and roots, hence the large class of verb-derived words which includes altrix, amator, auditor, and victrix.

In theory, any verb could interact with the suffixes to produce agent nouns in -tor and -trix, but according to a formal understanding of “agent,” only eventive verbs whose semantics allow for an agent noun can produce such words, while stative and unaccusative verbs cannot produce them because they do not have agents (Miller, Latin Suffixal Derivatives in English, section 3.7). Even so, it is difficult to determine whether the Romans themselves consciously classified verbs in such ways or viewed the idea of “agent” so narrowly instead of interpreting the agent nouns in -tor and -trix simply as “individual who relates to the verbal notion of the word from which it derives.” (In fact, as we have seen, Priscian refers to each of these words as a nomen verbale, “verbal noun,” rather than, say, a nomen agentis, “agent noun.” Moreover, Priscian’s omnia participia description suggests that any verb can interact with the agent noun suffixes.) This looser understanding of “agent” is sufficient when analyzing any agent noun in -tor or trix. This helps us analyze a word like senator (“he who is a magistrate in the senate”) whose base word, senatus, suggests a more obvious stative notion (i.e., *senare, “to be a magistrate in the senate”) than an eventive one. It also allows us to work with non-eventive verbs to produce words like *sordetor or *sorditor (“one who is filthy,” from sordere), *putetor or *putretor (“rotter,” from putere and putrere, respectively), *collapsor (“collapser,” from collabi), *exsistitor (“ariser,” from exsistitere), and even *futor (“one who exists,” from esse).

3.B. Verb-Suffix Interactions

The true nature of the -tor and -trix suffixes will become clear once I have explained how they actually interacted with their respective verbs to create the various agent nouns. Such interactions involve three important concepts:

the structure of the suffixes themselves,

the relationship between these suffixes and several other suffixes, and

the actual parts of the verbs to which these suffixes are added.

I shall explain all three of these in detail below.

3.B.a. Structure of Suffixes

First, we should get to understand the structure of the suffixes themselves. While it is the case that the suffixes are exactly -tor and -trix, the Romans used them in such a way that they are bipartite in a certain sense—they comprise the -or and -rix elements on the one hand, and the -t- section on the other hand. That bipartite nature, however, does not imply that the two parts are wholly discrete or independent. The parts are ultimately indivisible because each part relies on the existence of the other. The -or and -rix elements themselves have no meaning at all and need their initial -t- to be complete, and the -t- element cannot stand alone nor can it readily function as an infix. That bipartite nature of the suffixes explains Priscian’s misinterpretation of their forms. He mistakingly interprets that nature as implying that the two parts of the suffixes are entirely separate entities.

The -t- section of the suffixes in fact was used as a linguistic marker common to the perfect-participle-forming suffix -tus. What this means is that -or and -rix are not separate extensions of the bases of perfect participles, as Priscian and others believe, but rather the suffixes are -tor and -trix and are parallel to the suffix -tus, which is involved in the creation of those participles.

3.B.b. “Families” of Suffixes

Next, we must understand the relationship between the suffixes -tor and -trix and several other suffixes. The -tor and -trix, and even the perfect-participle-forming -tus, are members of a “family” of t-initial suffixes that were regularly attached to the same parts of verbs to create different sorts of words. Some important members of this “family” of suffixes are:

-tus, creating the perfect participle, e.g., amatus from amare;

-tum, creating the supine, e.g., amatum from amare;

-turus, creating the future active participle, e.g., amaturus from amare;

-tor, creating the masculine agent noun, e.g., amator from amare;

-trix, creating the feminine agent noun, e.g., amatrix from amare;

-tus, creating a noun denoting action or result, e.g., ornatus from onare;

-tio, creating a noun denoting quality, e.g., amatio from amare;

-tura, creating a noun denoting result, e.g., creatura from creare;

-turire, creating a desiderative verb, e.g., amaturire from amare;

-tare, creating an intensive or iterative verb, e.g., iactare from iacere;

-tivus, creating a verbal adjective, e.g., indicativus from indicare;

-tim, creating an adverb, e.g., certatim from certare;

-trum, creating a noun denoting instrument, e.g., aratrum from arare;

-trina, creating a noun denoting activity or locality, e.g., lavatrina from lavare.

When these suffixes are added to certain parts of a verb, they produce the corresponding verb-derived forms and words in the follow ways:

ama- + -tus → amatus;

ama- + -tum → amatum;

ama- + -turus → amaturus;

ama- + -tor → amator;

ama- + -trix → amatrix;

and so on.

It is crucial that we notice that these suffixes were all added to the same particular part of their respective verb to create those forms and words.

Various sorts of phonetic changes occurred to produce an s-initial variant of this “family” of suffixes, and this variant is used for certain verbs. Thus, for example, the verb manere, “to remain,” uses suffixes that begin with -s-:

man- + -sus → mansus;

man- + -sum → mansum;

man- + -surus → mansurus;

man- + -sor → mansor;

man- + -sio → mansio.

3.B.c. Suffixes, Parts of Verbs, and Actual Procedures

Let us now study the third important concept: the question of which actual parts of the verbs Latin uses when adding on these suffixes. It turns out that these suffixes are not added indiscriminately to verb stems and roots. On the contrary, there is a complex system of interaction between these word-forming suffixes and verbs. The next few sections provide explanations of the actual procedures of how such interaction occurs. A complete list of the minutiae relevant to these procedures would be very long, but there are some typical key facts which we should learn about and then keep in mind.

3.B.c.i. Stems Ending in Long -a-, -e-, -i-

The members of the “family” of t-initial suffixes are simply added to the stems of most verbs of the first conjugation, a few verbs of the second conjugation, and many verbs of the fourth conjugation, and the long stem vowels, a and e and i, remain unchanged before the suffixes:

amare, “to love,” stem ama-, which yields

ama- + -tus → amatus,

ama- + -turus → amaturus,

ama- + -tor → amator,

ama- + -trix → amatrix;

complere, “to fulfill,” stem comple-, which yields

comple- + -tus → completus,

comple- + -turus → completurus,

comple- + -tor → completor,

comple- + -tio → completio;

finire, “to limit,” stem fini-, which yields

fini- + -tus → finitus,

fini- + -turus → finiturus,

fini- + -tor → finitor,

fini- + -tio → finitio.

3.B.c.ii. Roots with Added Short -i-

For some verbs, a short -i- appears after the root of the verbs, and then those members of the “family” of t-initial suffixes appear after that vowel:

domare, “to tame,” stem domare, root DOM, which yields

DOM + -i- + -tus → domitus,

DOM + -i- + -turus → domiturus,

DOM + -i- + -tor → domitor,

DOM + -i- + -trix → domitrix;

monere, “to warn,” stem mone-, root MON, which yields

MON + -i- + -tus → monitus,

MON + -i- + -turus → moniturus,

MON + -i- + -tor → monitor,

MON + -i- + -tio → monitio.

3.B.c.iii. Roots with Added Long -i-

For some verbs which are not of the fourth conjugation, a long -i- appears before the suffixes, on the analogy of the usual fourth-conjugation verbs:

cupere, “to desire,” stem cupe-, root CUP, which yields

CUP + -i- + -tus → cupitus,

CUP + -i- + -turus → cupiturus,

CUP + -i- + -tor → cupitor;

petere, “to seek,” stem pete-, root PET, which yields

PET + -i- + -tus → petitus,

PET + -i- + -turus → petiturus,

PET + -i- + -tor → petitor,

PET + -i- + -tio → petitio.

3.B.c.iv. U-Final Stems and Roots

In third-conjugation verbs made from u-stem nouns, and primary verbs whose roots end in -u-, the suffixes are added, and the -u- appears long:

statuere, “to set up,” stem statue-, root STATU, which yields

STATU + -tus → statutus,

STATU + -turus → statuturus,

STATU + -tio → statutio;

suere, “to sew,” stem sue-, root SU, which yields

SU + -tus → sutus,

SU + -turus → suturus,

SU + -tor → sutor,

SU + -tura → sutura;

tribuere, “to allot,” stem tribue-, root TRIBU, which yields

TRIBU + -tus → tributus,

TRIBU + -turus → tributurus,

TRIBU + -tor → tributor,

TRIBU + -tio → tributio.

3.B.c.v. Other Vowel-Final Roots

Verb roots ending in a vowel other than -u- may keep that vowel or change it (i.e., by weakening it to another vowel), and then add the suffixes:

dare, “to give,” stem da-, root DA, which yields

DA + -tum → datum,

DA + -turus → daturus,

DA + -tor → dator;

ire, “to go,” stem i-, roots EI and I, which yields

I + -tum → itum,

I + -turus → iturus,

I + -tare → itare;

prodere, “to betray,” stem prode-, root PRODA, which yields

PRODA + -tus → *prodatus → proditus,

PRODA + -turus → *prodaturus → proditurus,

PRODA + -tor → *prodator → proditor,

PRODA + -trix → *prodatrix → proditrix;

praestare, “to give,” stem praesta-, root PRAESTA, which yields

PRAESTA + -tum → *praestatum → praestitum,

PRAESTA + -turus → *praestaturus → praestiturus,

PRAESTA + -tor → *praestator → praestitor.

3.B.c.vi. Consonant-Final Roots: Overview

When the suffixes are added to verb roots ending in a consonant, various consonant-based phonetic changes may or may not occur within the verb root and the suffixes. These phonetic changes, when they do occur, involve one or more of the consonants of the root and the first letter of the suffixes.

3.B.c.vii. Consonant-Final Roots: No Phonetic Changes

Here are some examples of consonant-final verbs for which the addition of the suffixes does not produce consonant-based phonetic changes:

capere, “to take,” stem cape-, root CAP, which yields

CAP + -tus → captus,

CAP + -turus → capturus,

CAP + -tor → captor,

CAP + -tio → captio;

ducere, “to lead,” stem duce-, root DUC, which yields

DUC + -tus → ductus,

DUC + -turus → ducturus,

DUC + -tor → ductor,

DUC + -tio → ductio.

3.B.c.viii. Consonant-Final Roots: Phonetic Change Types

When phonetic changes do occur, they can be of various types. Some especially important and typical types of phonetic changes are:

assimilation of consonants (i.e., sounds becoming more similar), e.g.,

FRAG (root of frangere, “to break”) + -tus → fractus,

SCRIB (root of scribere, “to write”) + -tus → scriptus;

loss of letters, e.g.,

TORCV (root of torquere, “to twist”) + -tus → *torcutus → tortus,

SPARG (root of spargere, “to scatter”) + -sus → *spargsus → sparsus;

addition of letters, e.g.,

EM (root of emere, “to buy”) + -p- + -tus → emptus,

CONTEM (root of contemnere, “to despise”) + -p- + -tus → contemptus;

metathesis (i.e., rearrangement of letters), e.g.,

MISC (root of miscere, “to mix”) + -tus → *misctus → mixtus,

STER (root of sternere, “to spread”) + -tus → *stertus → stratus;

change from [q]u/v to u, e.g.,

LOQU (root of loqui, “to talk”) + -tus → *loqutus → locutus,

VOLV (root of volvere, “to roll”) + -tus → *volvtus → volutus;

suppletion (i.e., use of different roots), e.g.,

FU (root of esse, “to be”) + -turus → futurus,

TLA (root of ferre, “to bear”) + -tus → *tlatus → latus;

-c- or -g- and -s- combining into -x-, e.g.,

FIG (root of figere, “to fix”) + -sus → *figsus → fixus,

NEC (root of nectere, “to weave”) + -sus → *necsus → nexus;

combinations of any of the above, e.g.,

FLUGV (root of fluere, “to flow”) + -sus → *flugvsus → *flugsus → fluxus,

PLAG (root of plangere, “to beat”) + -n- + -tus → *plangtus → planctus,

STRUGV (root of struere, “to build”) + -tus → *strugvtus → *strugtus → structus,

TUD (root of tundere, “to beat”) + -n- + -tus → *tundtus → *tunssus → tunsus,

VID (root of videre, “to see”) + -tus → *vidtus → *vissus → visus.

3.B.c.ix. Consonant-Final Roots: More about Assimilation

Among these phonetic change types, assimilation is an especially notable one not only because of its ubiquity, but also because of the apparently drastic changes in sounds which occur. So, for example, a -g- becomes -c- before -t-, but this apparently strange sort of change is natural because a voiced mute becomes unvoiced when it appears before another unvoiced mute. Moreover, the loss of a letter or letters may accompany assimilation. So, -ss- (which came about from the assimiliation of consonants) is often simplified to just -s-. Here are some examples which feature the relevant phonetic changes:

agere, “to drive,” stem age-, root AG, which yields

AG + -tus → *agtus → actus,

AG + -turus → *agturus → acturus,

AG + -tor → *agtor → actor,

AG + -tio → *agtio → actio;

caedere, “to cut,” stem caede-, root CAED, which yields

CAED + -tus → *caedtus → *caessus → caesus,

CAED + -turus → *caedturus → *caessurus → caesurus,

CAED + -tor → *caedtor → *caessor → caesor,

CAED + -tio → *caedtio → *caessio → caesio;

possidere, “to possess,” stem posside-, root POSSID, which yields

POSSID + -tus → *possidtus → *possissus → possessus,

POSSID + -turus → *possidturus → *possissurus → possessurus,

POSSID + -tor → *possidtor → *possissor → possessor,

POSSID + -tio → *possidtio → *possissio → possessio;

regere, “to direct,” stem rege-, root REG, which yields

REG + -tus → *regtus → rectus,

REG + -turus → *regturus → recturus,

REG + -tor → *regtor → rector,

REG + -trix → *regtrix → rectrix;

scribere, “to write,” stem scribe-, root SCRIB, which yields

SCRIB + -tus → *scribtus → scriptus,

SCRIB + -turus → *scribturus → scripturus,

SCRIB + -tor → *scribtor → scriptor,

SCRIB + -tura → *scribtura → scriptura;

videre, “to see,” stem vide-, root VID, which yields

VID + -tus → *vidtus → *vissus → visus,

VID + -turus → *vidturus → *vissurus → visurus,

VID + -tor → *vidtor → *vissor → visor,

VID + -tio → *vidtio → *vissio → visio.

3.B.c.x. Consonant-Final Roots: S-Initial Suffixes

Because of the ubiquity of the change of the initial -t- of the suffixes to -s- through assimilation, there was produced the s-initial variants of the “family” of suffixes. These s-initial variants, much like the original t-initial ones, are liable to bring about other types of phonetic change. Some examples of verbs which use these s-initial variants are:

censere, “to assess,” stem cense-, root CENS, which yields

CENS + -sus → *censsus → census,

CENS + -surus → *censsurus → censurus,

CENS + -sor → *censsor → censor,

CENS + -sio → *censsio → censio;

fallere, “to deceive,” stem falle-, root FAL, which yields

FAL + -sus → falsus,

FAL + -surus → falsurus,

FAL + -sor → falsor,

FAL + -sum → falsum;

figere, “to fix,” stem fige-, root FIG, which yields

FIG + -sus → *figsus → fixus,

FIG + -surus → *figsurus → fixurus,

FIG + -sor → *figsor → -fixor in crucifixor,

FIG + -sura → *figsura → fixura.

3.B.c.xi. Consonant-Final Roots: The -tr- Combination

There is one notable combination of consonants in which one consonant keeps another consonant from changing. Latin does not allow a -t- to become -s- when an -r- appears immediately after that -t-. We can see this when the stems equit- and -tri- produced equestri-, the stem of equester, instead of equessri-. Due to such phonetic behavior, in the formation of derivative words, the final letters of a root may change before members of this “family” of t-initial suffixes, but the -tr- part which appears in members of this “family” (e.g., -trix, -trina, and -trum) does not change to -sr-.

edere, “to eat,” stem ede-, root ED, which yields

ED + -tor → *edtor → *essor → esor,

ED + -trix → *edtrix → estrix;

pinsere, “to bruise,” stem pinse-, root PIS, which yields

PIS + -tor → pistor,

PIS + -n- + -tor → *pinstor → *pinssor → pinsor,

PIS + -trina → pistrina;

radere, “to shave,” stem rade-, root RAD, which yields

RAD + -tor → *radtor → *rassor → rasor,

RAD + -trum → *radtrum → rastrum.

3.B.c.xii. Analogical Forms with Short -i-

Words like domare and monere are the basis of the analogy where a connecting vowel -i- appears between the present stem of a verb and one of the members of a “family” of t-initial suffixes. This irregular and optional procedure can apply even if the suffixes normally attach to different parts of a particular verb, or if the verb does not normally even use the suffixes at all.

agere, “to drive,” stem age-, root AG, which yields

age- + -i- + -tare → agitare;

converrere, “to sweep together,” stem converre-, root CONVERS, which yields

converr- + -i- + -tor → converritor;

pavere, “to be struck with fear,” stem pave-, root PAV, which yields

pave- + -i- + -tare → pavitare.

According to the standard rules, agere yields words like actus, actio, and actor, but this analogous procedure brought about agitare, which implies imaginary words like the participle *agitus, the supine *agitum, the agent nouns *agitor and *agitrix, and the noun *agitio. Pavere does not normally take any of these suffixes, and yet this analogical procedure has produced pavitare, which itself implies other words produced from the “family” of t-initial suffixes such as *pavitus, *pavitum, *pavitor, *pavitrix, and *pavitio.

This is the procedure which produced words like converritor and favitor. Such forms, of course, imply words like *converritus, and *favitio.

This procedure was not especially common, but it had enough productivity to move its focus of application from verb stems to noun stems, and so it produced noun-derived words like ficitor, ianitor, and olivitor.

3.B.c.xiii. Compound Suffixes

The -str- combination of letters appears so often in such derivative words that the -s- was thought to be part of the suffix, and so compound suffixes such as -strix and -strum were created though resegmentation. These suffixes were then added to the relevant stem or root of the verb.

capere, “to take,” stem cape-, root CAP, which yields

cape- + -i- + -strum → capistrum;

impellere, “to impel,” stem impelle-, root IMPUL, which yields

IMPUL + -strix → impulstrix;

monere, “to warn,” stem mone-, root MON, which yields

MON + -strum → monstrum.

The use of these compound suffixes with the verbs is not at all common. Capere, impellere, and monere would have yielded the words *captrum, *impultrix, and *montrum, respectively, according to the more typical rules.

3.B.c.xiv. Verb Roots Not Easily Discernible

Very often the root of a verb is not easily discernible from the principal parts of that verb. I have decided to include many examples of such roots here:

currere, “to run,” stem curre-, root CURS, which yields

CURS + -sum → *curssum → cursum,

CURS + -surus → *curssurus → cursurus,

CURS + -sor → *curssor → cursor,

CURS + -sio → *curssio → cursio;

emere, “to buy,” stem eme-, root EM, which yields

EM + -p- + -tus → emptus,

EM + -p- + -turus → empturus,

EM + -p- + -tor → emptor,

EM + -p- + -tio → emptio;

esse, “to be,” stem es-/s-, roots ES and FU, which yields

FU + -turus → futurus;

ferre, “to bear,” stem fer-, roots FER and TLA, which yields

TLA + -tus → *tlatus → latus,

TLA + -turus → *tlaturus → laturus,

TLA + -tura → *tlatura → latura,

TLA + -tio → *tlatio → latio;

flectere, “to bend,” stem flecte-, root FLEC, which yields

FLEC + -sus → *flecsus → flexus,

FLEC + -surus → *flecsurus → flexurus,

FLEC + -sor → *flecsor → flexor,

FLEC + -sio → *flecsio → flexio;

fluere, “to flow,” stem flue-, root FLUGV, which yields

FLUGV + -sum → *flugvsum → *flugsum → fluxum,

FLUGV + -sus → *flugvsus → *flugsus → fluxus,

FLUGV + -sura → *flugvsura → *flugsura → fluxura,

FLUGV + -sio → *flugvsio → *flugsio → fluxio;

frangere, “to break,” stem frange-, root FRAG, which yields

FRAG + -tus → *fragtus → fractus,

FRAG + -turus → *fragturus → fracturus,

FRAG + -tor → *fragtor → fractor,

FRAG + -tura → *fragtura → fractura;

fulcire, “to support,” stem fulci-, root FULC, which yields

FULC + -tus → *fulctus → fultus,

FULC + -turus → *fulcturus → fulturus,

FULC + -tor → *fulctor → fultor,

FULC + -tura → *fulctura → fultura;

gerere, “to carry,” stem gere-, root GES, which yields

GES + -tus → gestus,

GES + -turus → gesturus,

GES + -tor → gestor,

GES + -tio → gestio;

iubere, “to order,” stem iube-, root IUD, which yields

IUD + -tus → *iudtus → iussus,

IUD + -tum → *iudtum → iussum,

IUD + -turus → *iudturus → iussurus;

labi, “to slip,” stem labe-, root LAB, which yields

LAB + -sus → *labsus → lapsus,

LAB + -surus → *labsurus → lapsurus,

LAB + -sio → *labsio → lapsio;

loqui, “to talk,” stem loque-, root LOQU, which yields

LOQU + -tus → *loqutus → locutus,

LOQU + -turus → *loquturus → locuturus,

LOQU + -tor → *loqutor → locutor,

LOQU + -tio → *loqutio → locutio;

miscere, “to mix,” stem misce-, root MISC, which yields

MISC + -tus → *misctus → *micstus → mixtus,

MISC + -turus → *miscturus → *micsturus → mixturus,

MISC + -tor → *misctor → *micstor → mixtor,

MISC + -tura → *misctura → *micstura → mixtura;

mulcere, “to stroke,” stem mulce-, root MULC, which yields

MULC + -sus → *mulcsus → mulsus,

MULC + -tus → mulctus,

MULC + -tus → *mulctus → multus,

MULC + -surus → *mulcsurus → mulsurus,

MULC + -turus → mulcturus,

MULC + -turus → *mulcturus → multurus;

mulgere, “to milk,” stem mulge-, root MULG, which yields

MULG + -sus → *mulgsus → mulsus,

MULG + -tus → *mulgtus → mulctus,

MULG + -surus → *mulgsurus → mulsurus,

MULG + -turus → *mulgturus → mulcturus,

MULG + -trum → *mulgtrum → mulctrum,

MULG + -sura → *mulgsura → mulsura;

noscere, “to get to know,” stem nosce-, root NO, which yields

NO + -tus → notus,

NO + -turus → noturus,

NO + -tor → notor,

NO + -tio → notio;

pellere, “to push,” stem pelle-, root PUL, which yields

PUL + -sus → pulsus,

PUL + -surus → pulsurus,

PUL + -sor → pulsor,

PUL + -sio → pulsio;

percellere, “to beat down,” stem percelle-, root PERCUL, which yields

PERCUL + -sus → perculsus,

PERCUL + -surus → perculsurus;

pinsere, “to bruise,” stem pinse-, root PIS, which yields

PIS + -tus → pistus,

PIS + -n- + -tus → *pinstus → *pinssus → pinsus,

PIS + -n- + -i- + -tus → pinsitus,

PIS + -turus → pisturus,

PIS + -n- + -turus → *pinsturus → *pinssurus → pinsurus,

PIS + -n- + -i- + -turus → pinsiturus,

PIS + -tor → pistor,

PIS + -n- + -tor → *pinstor → *pinssor → pinsor;

plangere, “to beat,” stem plange-, root PLAG, which yields

PLAG + -n- + -tus → planctus,

PLAG + -n- + -turus → plancturus;

potare, “to drink,” stem pota-, root PO, which yields

pota- + -tus → potatus,

pota- + -turus → potaturus,

PO + -tus → potus,

PO + -tor → potor;

premere, “to press,” stem preme-, root PRES, which yields

PRES + -sus → pressus,

PRES + -surus → pressurus,

PRES + -sor → pressor,

PRES + -sura → pressura;

scire, “to know,” stem sci-, root SCI, which yields

sci- + -tum → scitum,

sci- + -turus → sciturus,

sci- + -tari → scitari;

sequi, “to follow,” stem seque-, root SEQU, which yields

SEQU + -tus → *sequtus → secutus,

SEQU + -turus → *sequturus → secuturus,

SEQU + -tor → *sequtor → secutor,

SEQU + -tio → *sequtio → secutio;

solvere, “to loosen,” stem solve-, root SOLV, which yields

SOLV + -tus → *solvtus → solutus,

SOLV + -turus → *solvturus → soluturus,

SOLV + -tor → *solvtor → solutor,

SOLV + -tio → *solvtio → solutio;

spargere, “to scatter,” stem sparge-, root SPARG, which yields

SPARG + -sus → *spargsus → sparsus,

SPARG + -surus → *spargsurus → sparsurus,

SPARG + -sor → *spargsor → sparsor,

SPARG + -sio → *spargsio → sparsio;

sternere, “to spread,” stem sterne-, root STER, which yields

STER + -tus → *stertus → stratus,

STER + -turus → *sterturus → straturus,

STER + -tor → *stertor → strator,

STER + -tura → *stertura → stratura;

struere, “to build,” stem strue-, root STRUGV, which yields

STRUGV + -tus → *strugvtus → *strugtus → structus,

STRUGV + -turus → *strugvturus → *strugturus → structurus,

STRUGV + -tor → *strugvtor → *strugtor → structor,

STRUGV + -tura → *strugvtura → *strugtura → structura;

torquere, “to twist,” stem torque-, root TORCU, which yields

TORCU + -tus → *torcutus → tortus,

TORCU + -turus → *torcuturus → torturus,

TORCU + -tor → *torcutor → tortor,

TORCU + -tura → *torcutura → tortura;

trahere, “to drag,” stem trahe-, root TRAGH, which yields

TRAGH + -tus → *traghtus → *tragtus → tractus,

TRAGH + -turus → *traghturus → *tragturus → tracturus,

TRAGH + -tor → *traghtor → *tragtor → tractor,

TRAGH + -tim → *traghtim → *tragtim → tractim;

unguere, “to anoint,” stem ungue-, root UNGV, which yields

UNGV + -tus → *ungutus → *ungtus → unctus,

UNGV + -turus → *unguturus → *ungturus → uncturus,

UNGV + -tor → *ungutor → *ungtor → unctor,

UNGV + -tio → *ungutio → *ungtio → unctio;

urere, “to burn,” stem ure-, root US, which yields

US + -tus → ustus,

US + -turus → usturus,

US + -tor → ustor,

US + -tio → ustio;

vehere, “to carry,” stem vehe-, root VEGH, which yields

VEGH + -tus → *veghtus → *vegtus → vectus,

VEGH + -turus → *veghturus → *vegturus → vecturus,

VEGH + -tor → *veghtor → *vegtor → vector,

VEGH + -tura → *veghtura → *vegtura → vectura;

vellere, “to pull,” stem velle-, root VUL, which yields

VUL + -sus → vulsus,

VUL + -surus → vulsurus,

VUL + -sor → vulsor,

VUL + -sura → vulsura;

volvere, “to roll,” stem volve-, root VOLV, which yields

VOLV + -tus → *volvtus → volutus,

VOLV + -turus → *volvturus → voluturus.

3.C. What the Phonetic Concepts and Examples Show

Having shown how the -tor and -trix suffixes interacted with their respective verbs, I believe my explanations of the phonetic concepts and my many examples should now have revealed the true nature of the suffixes.

4. My Idea Explains the Material Better

My “add -tor and -trix to verb stems and roots” idea can explain everything that the “add -or and -rix to the participial bases” one can and cannot. We should note these words and the processes through which they were formed:

assidere, “to sit near,” stem asside-, root ASSID, which yields

ASSID + -tor → *assidtor → *assissor → assessor,

ASSID + -trix → *assidtrix → *assistrix → assestrix;

expellere, “to expel,” stem expelle-, root EXPUL, which yields

EXPUL + -sor → expulsor,

EXPUL + -trix → expultrix;

possidere, “to possess,” stem posside-, root POSSID, which yields

POSSID + -tor → *possidtor → *possissor → possessor,

POSSID + -trix → *possidtrix → *possistrix → possestrix;

converrere, “to sweep together,” stem converre-, root CONVERS, which yields

converre- + -i- + -tor → converritor;

bibere, “to drink,” stem bibe-, root BIB, which yields

bibe- + -i- + -tor → bibitor;

delere, “to obliterate,” stem dele-, root DEL, which yields

dele- + -i- + -tor → delitor;

favere, “to support,” stem fave-, root FAV, which yields

fave- + -i- + -tor → favitor;

fugere, “to flee,” stem fuge-, FUG, which yields

fuge- + -i- + -tor → fugitor;

librare, “to hurl,” stem libra-, which yields

libra- + -i- + -tor → libritor;

merere, “to merit,” stem mere-, root MER, which yields

mere- + -trix → meretrix;

obstare, “to stand before,” stem obsta-, root OBSTA, which yields

OBSTA + -trix → *obstatrix → obstetrix;

ficus, “fig,” stem fico-/ficu-, which yields

fico-/ficu- + -i- + -tor → ficitor;

funda, “sling,” stem funda-, which yields

funda- + -i- + -tor → funditor;

ianus, “covered passageway,” stem iano-, which yields

iano- + -i- + -tor → ianitor,

iano- + -i- + -trix → ianitrix;

oliva, “olive,” stem oliva-, which yields

oliva- + -i- + -tor → olivitor.

My idea can also explain the forms that Priscian mentions:

armare, “to arm,” stem arma-, root ARM, which yields

arma- + -tor → armator,

arma- + -trix → armatrix;

prandere, “to have breakfast,” stem prande-, root PRAND, which yields

PRAND + -tor → *prandtor → *pranssor → pransor,

PRAND + -trix → *prandtrix → pranstrix;

currere, “to run,” stem curre-, root CURS, which yields

CURS + -sor → *curssor → cursor,

CURS + -trix → curstrix;

tondere, “to shear,” stem tonde-, root TOND, which yields

TOND + -tor → *tondtor → *tonssor → tonsor,

TOND + -trix → *tondtrix → tonstrix,

TOND + -trina → *tondtrina → tonstrina;

docere, “to teach,” stem doce-, root DOC, which yields

DOC + -tor → doctor,

DOC + -trix → doctrix,

DOC + -trina → doctrina;

defendere, “to defend,” stem defende-, root DEFEND, which yields

DEFEND + -tor → *defendtor → *defenssor → defensor,

DEFEND + -trix → *defendtrix → defenstrix.

5. Examples of Words Which We Can Create

We can use my “add -tor and -trix to verb stems and roots” idea to create the agent nouns from the other verbs. Below is a long list of agent nouns which either indeed already exist or can be produced by using my idea.

Neologisms with a † were created through a particular analogy.

alere, “to nourish,” stem ale-, root AL, which yields

AL + -tor → altor,

ale- + -i- + -tor → *†alitor,

AL + -trix → altrix,

ale- + -i- + -trix → *†alitrix;

audire, “to hear,” stem audi-, which yields

audi- + -tor → audītor,

audi- + -i- + -tor → *†audĭtor,

audi- + -trix → *audītrix,

audi- + -i- + -trix → *†audĭtrix;

bibere, “to drink,” stem bibe-, root BIB, which yields

bibe- + -i- + -tor → bibitor,

bibe- + -i- + -trix → *†bibitrix;

caedere, “to cut,” stem caede-, root CAED, which yields

CAED + -tor → *caedtor → *caessor → caesor,

caede- + -i- + -tor → *†caeditor,

CAED + -trix → *caedtrix → *caestrix,

caede- + -i- + -trix → *†caeditrix;

capere, “to take,” stem cape-, root CAP, which yields

CAP + -tor → captor,

cape- + -i- + -tor → *†capitor,

CAP + -trix → captrix,

cape- + -i- + -trix → *†capitrix;

censere, “to assess,” stem cense-, root CENS, which yields

CENS + -sor → *censsor → censor,

cense- + -i- + -tor → *†censitor,

CENS + -trix → *censtrix,

cense- + -i- + -trix → *†censitrix;

converrere, “to sweep together,” stem converre-, root CONVERS, which yields

CONVERS + -sor → *converssor → *conversor,

converre- + -i- + -tor → converritor,

CONVERS + -trix → *converstrix,

converre- + -i- + -trix → *†converritrix;

cupere, “to desire,” stem cupe-, root CUP, which yields

CUP + -i- + -tor → cupītor,

cupe- + -i- + -tor → *†cupĭtor,

CUP + -i- + -trix → *cupītrix,

cupe- + -i- + -trix → *†cupĭtrix;

delere, “to obliterate,” stem dele-, root DEL, which yields

dele- + -tor → *deletor,

dele- + -i- + -tor → delitor,

dele- + -trix → deletrix,

dele- + -i- + -trix → *†delitrix;

ducere, “to lead,” stem duce-, root DUC, which yields

DUC + -tor → ductor,

duce- + -i- + -tor → *†ducitor,

DUC + -trix → ductrix,

duce- + -i- + -trix → *†ducitrix;

emere, “to buy,” stem eme-, root EM, which yields

EM + -p- + -tor → emptor,

eme- + -i- + -tor → *†emitor,

EM + -p- + -trix → emptrix,

eme- + -i- + -trix → *†emitrix;

eradere, “to rub away,” stem erade-, root ERAD, which yields

ERAD + -tor → *eradtor → *erassor → *erasor,

erade- + -i- + -tor → *†eraditor,

ERAD + -trix → *eradtrix → *erastrix,

erade- + -i- + -trix → *†eraditrix;

esse, “to be,” stem es-/s-, roots ES and FU, which yields

FU + -tor → *futor,

s- + -i- + -tor → *†sitor,

FU + -trix → *futrix,

s- + -i- + -trix → *†sitrix;

expellere, “to expel,” stem expelle-, root EXPUL, which yields

EXPUL + -sor → expulsor,

expelle- + -i- + -tor → *†expellitor,

EXPUL + -trix → expultrix,

EXPUL + -strix → *expulstrix,

expelle- + -i- + -trix → *†expellitrix;

favere, “to support,” stem fave-, root FAV, which yields

FAV + -tor → fautor,

fave- + -i- + -tor → favitor,

FAV + -trix → fautrix,

fave- + -i- + -trix → *†favitrix;

fallere, “to deceive,” stem falle-, root FAL, which yields

FAL + -sor → *falsor,

falle- + -i- + -tor → *†fallitor,

FAL + -trix → *faltrix,

FAL + -strix → *falstrix,

falle- + -i- + -trix → *†fallitrix;

figere, “to fix,” stem fige-, root FIG, which yields

FIG + -sor → *figsor → *fixor,

fige- + -i- + -tor → *†figitor,

FIG + -trix → *figtrix → *fictrix,

fige- + -i- + -trix → *†figitrix;

finire, “to limit,” stem fini-, which yields

fini- + -tor → finītor,

fini- + -i- + -tor → *†finĭtor,

fini- + -trix → *finītrix,

fini- + -i- + -trix → *†finĭtrix;

ferre, “to bear,” stem fer-, roots FER and TLA, which yields

TLA + -tor → *tlator → lator,

fer- + -i- + -tor → *†feritor,

TLA + -trix → *tlatrix → *latrix,

fer- + -i- + -trix → *†feritrix;

flectere, “to bend,” stem flecte-, root FLEC, which yields

FLEC + -sor → *flecsor → *flexor,

flecte- + -i- + -tor → *†flectitor,

FLEC + -trix → *flectrix,

flecte- + -i- + -trix → *†flectitrix;

fluere, “to flow,” stem flue-, root FLUGV, which yields

FLUGV + -sor → *flugvsor → *flugsor → *fluxor,

flue- + -i- + -tor → *†fluitor,

FLUGV + -trix → *flugvtrix → *flugtrix → *fluctrix,

flue- + -i- + -trix → *†fluitrix;

frangere, “to break,” stem frange-, root FRAG, which yields

FRAG + -tor → *fragtor → fractor,

frange- + -i- + -tor → *†frangitor,

FRAG + -trix → *fragtrix → *fractrix,

frange- + -i- + -trix → *†frangitrix;

fugere, “to flee,” stem fuge-, FUG, which yields

fuge- + -i- + -tor → fugitor,

fuge- + -i- + -trix → *†fugitrix;

fulcire, “to support,” stem fulci-, root FULC, which yields

FULC + -tor → *fulctor → fultor,

fulci- + -i- + -tor → *†fulcitor,

FULC + -trix → *fulctrix → *fultrix,

FULC + -strix → *fulcstrix → *fulstrix,

fulci- + -i- + -trix → *†fulcitrix;

gerere, “to carry,” stem gere-, root GES, which yields

GES + -tor → gestor,

gere + -i- + -tor → *†geritor,

GES + -trix → *gestrix,

gere- + -i- + -trix → *†geritrix;

*gladiare, “to wield a sword,” stem gladia-, which yields

gladia- + -tor → gladiator,

gladia- + -trix → *gladiatrix;

impellere, “to impel,” stem impelle-, root IMPUL, which yields

IMPUL + -sor → impulsor,

impelle- + -i- + -tor → *†impellitor,

IMPUL + -trix → *impultrix,

IMPUL + -strix → impulstrix,

impelle- + -i- + -trix → *†impellitrix;

ire, “to go,” stem i-, roots EI and I, which yields

I + -tor → *itor,

I + -trix → *itrix;

iubere, “to order,” stem iube-, root IUD, which yields

IUD + -tor → *iudtor → *iussor,

iube- + -i- + -tor → *†iubitor,

IUD + -trix → *iudtrix → *iustrix,

iube- + -i- + -trix → *†iubitrix;

labi, “to slip,” stem labe-, root LAB, which yields

LAB + -sor → *labsor → *lapsor,

labe- + -i- + -tor → *†labitor,

LAB + -trix → *labtrix → *laptrix,

LAB + -strix → *labstrix → *lapstrix,

labe- + -i- + -trix → *†labitrix;

librare, “to hurl,” stem libra-, which yields

libra- + -tor → librator,

libra- + -i- + -tor → libritor,

libra- + -trix → *libratrix,

libra- + -i- + -trix → *†libritrix;

loqui, “to talk,” stem loque-, root LOQU, which yields

LOQU + -tor → *loqutor → locutor,

loque + -i- + -tor → *†loquitor,

LOQU + -trix → *loqutrix → *locutrix,

loque + -i- + -trix → *†loquitrix;

manere, “to remain,” stem mane-, root MAN, which yields

MAN + -sor → mansor,

mane- + -i- + -tor → *†manitor,

MAN + -trix → *mantrix,

MAN + -strix → *manstrix,

mane- + -i- + -trix → *†manitrix;

merere, “to merit,” stem mere-, root MER, which yields

mere- + -i- + -tor → *meritor,

mere- + -tor → *meretor,

mere- + -i- + -trix → *meritrix,

mere- + -trix → meretrix;

miscere, “to mix,” stem misce-, root MISC, which yields

MISC + -tor → *misctor → *micstor → *mixtor,

misce- + -i- + -tor → *†miscitor,

MISC + -trix → *misctrix → *micstrix → *mixtrix,

misce- + -i- + -trix → *†miscitrix;

monere, “to warn,” stem mone-, root MON, which yields

MON + -i- + -tor → monitor,

MON + -i- + -trix → *monitrix,

MON + -trix → *montrix,

MON + -strix → *monstrix;

mori, “to die,” stem more-, root MOR, which yields

MOR + -tor → *mortor,

more- + -i- + -tor → *†moritor,

MOR + -trix → *mortrix,

more- + -i- + -trix → *†moritrix;

movere, “to move,” stem move-, root MOV, which yields

MOV + -tor → *movtor → motor,

move- + -i- + -tor → *†movitor,

MOV + -trix → *movtrix → *motrix,

move- + -i- + -trix → *†movitrix;

mulcere, “to stroke,” stem mulce-, root MULC, which yields

MULC + -sor → *mulcsor → *mulsor,

MULC + -tor → *mulctor,

MULC + -tor → *mulctor → *multor,

mulce- + -i- + -tor → *†mulcitor,

MULC + -trix → *mulctrix → *multrix,

MULC + -trix → *mulctrix,

MULC + -strix → *mulcstrix → *mulstrix,

mulce- + -i- + -trix → *†mulcitrix;

mulgere, “to milk,” stem mulge-, root MULG, which yields

MULG + -sor → *mulgsor → *mulsor,

MULG + -tor → *mulgtor → *mulctor,

mulge- + -i- + -tor → *†mulgitor,

MULG + -trix → *mulgtrix → *multrix,

MULG + -trix → *mulgtrix → *mulctrix,

MULG + -strix → *mulgstrix → *mulstrix,

mulge- + -i- + -trix → *†mulgitrix;

noscere, “to get to know,” stem nosce-, root NO, which yields

NO + -tor → notor,

nosce- + -i- + -tor → *†noscitor,

NO + -trix → *notrix,

nosce- + -i- + -trix → *†noscitrix;

obstare, “to stand before,” stem obsta-, root OBSTA, which yields

OBSTA + -tor → *obstator,

OBSTA + -tor → *obstator → *obstetor,

OBSTA + -trix → *obstatrix,

OBSTA + -trix → *obstatrix → obstetrix;

pavere, “to be struck with fear,” stem pave-, root PAV, which yields

pave- + -i- + -tor → *†pavitor,

pave- + -i- + -trix → *†pavitrix;

pellere, “to push,” stem pelle-, root PUL, which yields