#Resource allocation solutions

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

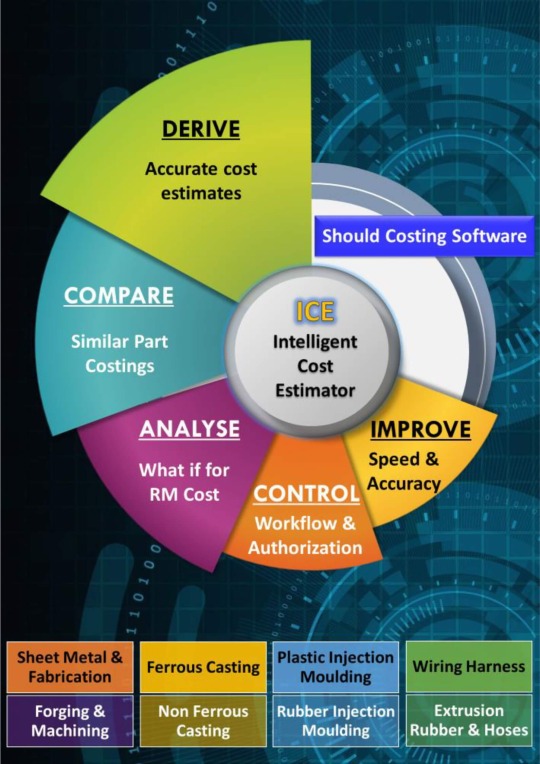

Best Estimating and Costing Software - Cost Masters

Find reliable project cost estimation and optimization with Cost Masters – a trusted provider of estimating and costing software. Streamline your budgeting process with our precise and efficient tools. Eliminate errors and simplify cost management. Learn more about Cost Masters today.

#Estimation and costing software#Cost management tools#Project cost estimation software#Budgeting software solutions#Cost optimization software#Price tracking and analysis tools#Procurement management software#Material cost estimation solutions#Cost calculation software#Project budgeting solutions#Pricing analysis tools#Expense management software#Cost forecasting and planning tools#Profitability analysis software#Resource allocation solutions#Financial planning and analysis software#Cost control and management tools#Spend analysis software

1 note

·

View note

Text

Construction Management Software: A Comprehensive Overview

Construction management software (CMS) is a vital tool for modern construction projects, enabling professionals to manage various aspects of project execution efficiently. With the construction industry facing increasing complexities and demands, CMS has become essential for improving productivity, reducing costs, and enhancing collaboration among stakeholders. Courtesy: CRM.org Key Features of…

#cloud-based construction software#construction efficiency tools#construction industry software#construction management software#construction project planning#construction scheduling software#document management systems#field management solutions#mobile construction apps#project management tools#project tracking software#real-time collaboration tools#resource allocation software#risk management in construction

0 notes

Text

Overcoming the 60% Struggle with ML Adoption: Key Insights

In the race to stay competitive, companies are turning to machine learning (ML) to unlock new levels of efficiency and innovation. But what does it take to successfully adopt ML?

Machine learning (ML) is a transformative technology offering personalized customer experiences, predictive analytics, operational efficiency, fraud detection, and enhanced decision-making. Despite its potential, many companies struggle with ML adoption due to data quality challenges, a lack of skilled talent, high costs, and resistance to change.

Effective ML implementation requires robust data management practices, investment in training, and a culture that embraces innovation. Intelisync provides comprehensive ML services, including strategy development, model building, deployment, and integration, helping companies overcome these hurdles and leverage ML for success.

Overcoming data quality and availability challenges is crucial for building effective ML models. Implementing robust data management practices, including data cleaning and governance, ensures consistency and accuracy, leading to reliable ML models and better decision-making. Addressing the talent gap through training programs and partnerships with experts like Intelisync can accelerate ML project implementation. Intelisync’s end-to-end ML solutions help businesses navigate the complexities of ML adoption, ensuring seamless integration with existing systems and maximizing efficiency. Fostering a culture of innovation and providing clear communication and leadership support are vital to overcoming resistance and promoting successful ML adoption.

Successful ML adoption involves careful planning, strategic execution, and continuous improvement. Companies must perform detailed cost-benefit analyses, start with manageable pilot projects, and regularly review and optimize their AI processes. Leadership support and clear communication are crucial to fostering a culture that values technological advancement. With Intelisync’s expert guidance, businesses can bridge the talent gap, ensure smooth integration, and unlock the full potential of machine learning for their growth and success. Transform your business with Intelisync’s comprehensive ML services and stay ahead in the competitive Learn more....

#5 Top Reasons Companies Struggle with Machine Learning Adoption#Boost your business efficiency and innovation with Intelisync’s expert ML solutions#Change Management and Organizational Resistance#Data Quality and Availability Challenges#Developing an ML Strategy for Your Business#High Costs and Resource Allocation#How can companies measure the ROI of their ML projects?#Machine learning#ML adoption#Personalized Customer Experiences#Predictive Analytics#Time-Consuming Implementation#What are some common misconceptions about machine learning adoption?#What are the benefits of partnering with a machine learning service provider?#What are the benefits of starting with pilot projects for ML adoption?#What are the main challenges companies face when adopting machine learning (ML)#What is Machine Learning?#Why Is ML Important for Companies?#Why Do 60% of Companies Struggle with ML Adoption?

0 notes

Note

Hello, can I ask how difficult is for developers to add accessibility features to games? I am aware it probably varies by type. Recently, I asked if a sound only minigame in one video game could be reworked to add visual cues, as I am deaf. Lot of other fans harped on me its too much work for little gain, too difficult, that it takes away precious developers time, etc. So now I wonder how complicated such thing actually is and how devs view it. Thank you.

They're not wrong in that building such things isn't free. However, you're also right in that we on the dev side should be thinking about better ways of doing this - there isn't only one solution to these problems. Whatever final solution we implement doesn't have to be the most expensive means of doing so. It's actually up to us to think of better/more efficient ways of doing the things we want to do. Adding accessibility options is often a worthy goal, not only to the players who need those options to be able to play, but also for general quality-of-life. If we're making changes after the fact, of course they're super expensive. If accessibility options are a production goal that we plan for, they're much cheaper because we don't have to redo work - we do it with accessibility in mind in the first place.

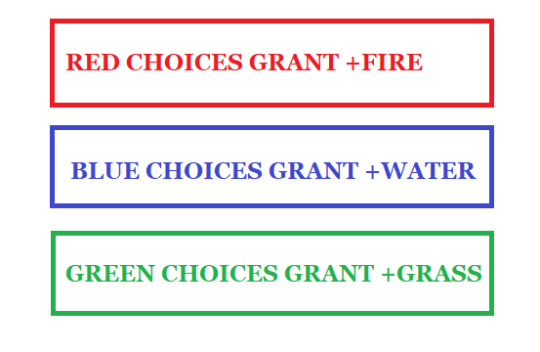

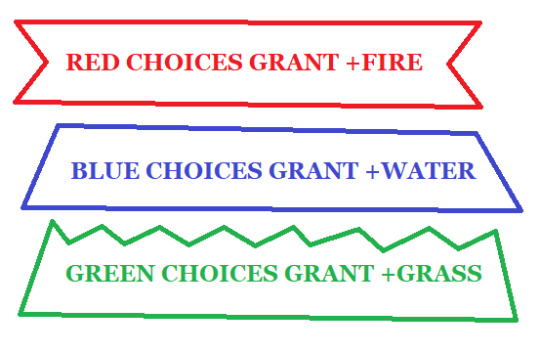

For example - let's say that we're working on UI and we have this system:

Let's say that we want to improve things for colorblind players. If we wanted to make this more accessible, instead of just using color to differentiate the choices, we could also add different border visuals to provide additional context.

In such a situation, the difference in choices is still obvious if you're colorblind and it helps legibility for non-colorblind players as well.

These kinds of UX changes can be expensive if we decide to do it after the fact, but if it's something we decide is important to us from the jump we can compensate for those costs by creating efficient and smart solutions early. Remember, the cost of any change in game development is directly proportional to how close that change is to shipping the game. The earlier the change is made, the cheaper it is. Furthermore, we make resource allocation choices based on our goals. If we want to make a game more accessible, we will figure out a way to do so that fits within our budget and provides a good player experience. Players don't really have a say in how we allocate our resources and that kind of armchair producer talk isn't particularly constructive anyway. Telling us what's important to you and why (including accessibility requests) is really the best kind of feedback we can hope for. Don't sweat coming up with the solutions or fretting about where we spend resources, that's our job.

[Join us on Discord] and/or [Support us on Patreon]

Got a burning question you want answered?

Short questions: Ask a Game Dev on Twitter

Long questions: Ask a Game Dev on Tumblr

Frequent Questions: The FAQ

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is what the utopian vision of the future so often misses: if and when change happens, the questions at play will be about if and how certain technology gets distributed, deployed, taken up. It will be about how governments decide to allocate resources, how the interests of various parties affected will be balanced, how an idea is sold and promulgated, and more. It will, in short, be about political will, resources, and the contest between competing ideologies and interests. The problems facing the world – not just climate breakdown but the housing crisis, the toxic drug crisis, or growing anti-immigrant sentiment – aren’t problems caused by a lack of intelligence or computing power. In some cases, the solutions to these problems are superficially simple. Homelessness, for example, is reduced when there are more and cheaper homes. But the fixes are difficult to implement because of social and political forces, not a lack of insight, thinking, or novelty. In other words, what will hold progress on these issues back will ultimately be what holds everything back: us.

8 August 2024

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

赤羽業 & 浅野学秀: the Venus de Milo problem

The results of the second semester finals between Gakushū and Karma were a convergence of their respective narratives throughout the school year—two students molded by opposing forces. Their teachers, reflections of each other’s antithesis, shaped their worldviews, while their relationships with those around them sculpted their distinct approaches to solving the final math problem. The infamous image of Venus de Milo was not just an emblem for the question; it was the perfect metaphor for the philosophical gap between the opposing sides in the academics area of Assassination Classroom.

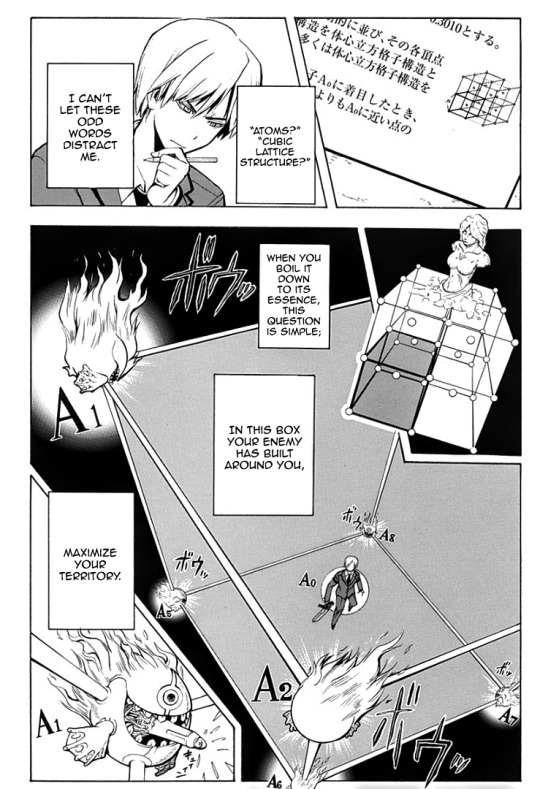

"Atoms" and "body-centered cubic structures"... I can't let those terms throw me. The question itself is quite simple. "You are inside a box surrounded by enemies... calculate the volume of your territory". Since our powers are equal, our attacks nullify each other. In other words, everything on the inside is my territory.

I'm surrounded by eight enemies inside this cube. Which means I need to calculate the volume of eight seals... and deduct that from the entire cube to get the volume of A0!

For Gakushu, the math problem was a test of control, an exercise in subjugating chaos to rationality. His solution was methodical, precise, and insular. To him, the box was a microcosm of his reality: a confined space where the rules are absolute, and success is achieved by bending those rules to one’s will. His focus on the “body-centered cubic structure” was emblematic of his fixation on the quantifiable. Pareto efficiency: Gakushu operates under the assumption that resources (or, in this case, space) must be allocated with optimal precision, leaving no room for inefficiency or external variables.

Yet, his flaw lies in his refusal to acknowledge the world outside the box. His worldview, while brilliant, is fundamentally limited by its rigidity. Gakushu does not look beyond the immediate; his vision, though sharp, is narrow.

Occam’s Razor is a philosophical principle suggests that the simplest solution is often the correct one. Gakushu eliminated extraneous elements, breaking the problem into its most essential parts to focus on what can be controlled within the given parameters. This is not to say he was wrong- we know that Gakushu's solution was correct. What decided the exam results was the race against time, which all comes back to how fast they arrive to the answer. Gakushu shaved down the details of the problem to maximize time and efficiency. In his own words: "The question itself is quite simple". Yet in his haste to simplify the problem, he unknowingly complicated it unnecessarily for himself, which ended in his loss.

The animation captures Gakushu’s mindset perfectly: his field of vision narrows, spotlighting only the part of the question he deems essential, with the rest fading into darkness. While his approach is flawless in theory and execution, it leaves no room for alternative interpretations or broader connections, leading to that inadvertent inefficiency. In another context, his approach would have been unbeatable.

I was only looking at this single small cube, but... since this is a crystal structure built from atoms... that means the same structure continues on the outside. In other words... there is more to this world than this single cube.

And if I look around me, I can see that everyone has their own unique talent... their own territory. And everyone else can see that too!

"Everyone has their own unique talent… their own territory," is an example of moral relativism, the idea that no single territory, talent, or solution is inherently superior to another.

Karma initially approached the question with the mental schema that it required extraordinary talent or effort to solve. By rereading and reframing the problem, he adjusted his schema to understand that the solution lay in simplicity and clarity, rather than overthinking or exceptional skill.

In contrast to Gakushu's animation, Karma’s mental process is visually chaotic, the animation mirroring his initial overwhelm. The camera pans dizzyingly across the paper, as if he’s grappling with the sheer surface-level complexity of the problem. But this momentary disorientation sparks something critical: a shift in perspective.

His realization has the essence of metacognition, which is the ability to think about one’s own thinking. He steps back from the problem, recognizing its context within a larger framework. This is the dialectical opposition between them: while Gakushu seeks to rule the box, Karma understands that the box is merely one part of a vast, interconnected world. His solution acknowledges the multiplicity of perspectives, valuing the contributions of others as integral to his own success.

Rather than avoiding the problem’s complexity, he embraces it (literally opening his arms lmao) using his own experiences and relationships as a lens to find clarity. Karma’s breakthrough is not his alone. It’s a culmination of the lessons from Korosensei and the camaraderie of Class E. These influences allow him to reframe the problem, breaking through its apparent complexity and arrive at an easy solution. Gakushu just didn't have that luxury from his father and Class A.

The Venus de Milo as a Metaphor

The Venus de Milo is known for its iconic missing arms, which were long gone before the statue was even discovered. Because of this, many interpretations of how the statue of Venus was posing and what the artist was trying to portray arose. In the same way, the final question symbolized a challenge that was both finite in its mathematical boundaries yet infinite in the ways it could be perceived. Here lies the thematic brilliance of the sculpture and the exam question: both demand the solver to confront the known and the unknown simultaneously.

#浅野学秀#赤羽業#暗殺教室#karma akabane#akabane karma#asano gakushuu#asano gakushu#assassination classroom#ansatsu kyoushitsu

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Universal housing won't work, because some homeless people want to be homeless! They don't want to be confined inside walls!"

Okay, suppose that's true. If every person were allocated their own house/apartment/unit, they wouldn't necessarily have to stay there. If they're more comfortable in the great outdoors, they could still sleep outside, hang out outside, spend their time outside. But they would still have a housing unit of their own, in case they wanted it. They could stay there occasionally, maybe when the weather was bad. They could take a shower there, receive mail there, have family and friends over there. Even if they chose not to use it as most housed people use our homes, they would still benefit from having it.

All of this, of course, is beside the point that the overwhelming majority of unhoused people do, in fact, want housing, and even the people who supposedly "turn down housing" or "don't want housing" are actually turning down the intense social control they're supposed to submit to in exchange for housing. There's a world of difference between "I'd rather sleep outside than live in a prison where I'm denied basic human rights and dignity" and "I actively like sleeping outside."

"But sometimes people in subsidized housing leave behind messes of blood and vomit and feces!"

Yes. Humans are animals, made of flesh and bone and gooey bits. Animals have gross bodily functions. We bleed and vomit and pee and poop. All of us do those things.

Sometimes, people -- especially poor people, who may have gone years without basic healthcare, or even decent food or hygiene -- have health issues or disabilities that prevent them from things like making it to the toilet in time, or cleaning up after themselves. Sometimes assigned housing for poor people is badly maintained, and may not even have things like a working flush toilet.

So yes, people have gross bodily functions, and some people -- especially if poor and/or sick and/or disabled -- may not have the ability or resources to deal with that issue in a hygienic way.

So what, exactly, is your solution?

Because my solution is to make sure that everyone has housing with adequate, working plumbing, and that everyone has access to voluntary healthcare to address chronic medical issues like vomiting or diarrhea, to provide needed adaptive equipment like a bedside commode, and, if needed, to hire personal care attendants to help people with things like cleaning, bathing, and toileting.

Your solution is what? That people with digestive issues should have to live outside? So they don't throw up on your nice floor? Do you have any idea how inhumane that sounds?

Or that they should be subjected to some type of coercive "behavior" program, because untreated Crohn's disease is a bad habit that they have to be tough-loved out of?

Because you think poor people are... just sitting there soiling themselves because they're too lazy to go to the toilet? That's actually what you think, isn't it? It follows logically from the assumption that poor people are poor in the first place because they're "lazy." But two seconds of thought would show that it couldn't possibly be true. You just think of poor people as less than human.

You are also gross and leaky and fleshy. You also poop and pee and barf and fart and sneeze. You are, through no virtue of your own, able to manage your bodily grossness. You are no better than someone who can't.

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHICAGO – Community activist and Chicago Against Violence founder Andre Smith may be a Democrat, but he says he's willing to work with incoming Trump border czar Tom Homan to deport illegal immigrants from the Windy City.

"I welcome in Chicago the border czar [Tom Homan]," Smith told Fox News Digital in an interview. "And [truth] be told, I wouldn't mind working with him seeing that I was the first person in Chicago to stand up and fight against the migrants."

Smith, who is also a preacher, has been on the front line of helping his community in Chicago, from helping the homeless population to fighting against local efforts by Mayor Brandon Johnson to disperse migrants throughout the city.

"I would love when he come[s] to Chicago to work with him, and getting them expedited back where they came from," Smith said of Homan. "Because to lie to a federal official is a federal offense, and if they came over on the pretenses of they are in fear of their life, then you have women, you have men, and all of them said they're in fear for their life because someone is going trying to kill them, and lying, you have to make examples."

Smith's comments come as many Chicago residents have been outraged by "sanctuary city" policies that have brought in thousands of migrants to a city already plagued by one of the highest violent crime rates in the U.S.

"Here we are in Chicago, where we [are] supposed to be celebrating a season of joy, love and happiness," Smith continued. "And a lot of people have Christmas trees and under their trees in Chicago. We are unwrapping gifts of neglect. We are unwrapping gifts of disappointment and heartaches. We are unwrapping gifts of $575 million of taxpayer dollars given to and misallocated to give to illegal migrants. We need solutions, and we need change."

Following President-elect Donald Trump's re-election, Johnson — who allocated millions of dollars to migrant resources — vowed to defend the illegal migrants residing in Chicago, saying "we will not bend or break," according to local news outlet WTTW.

"Our values will remain strong and firm. We will face likely hurdles in our work over the next four years, but we will not be stopped, and we will not go back," Johnson said.

Meanwhile, Homan spoke in Chicago last week and told local Republicans he wanted Illinois Democrats to "come to the table," but if not to "get the hell out of the way."

That comment sparked a fiery response from Rep. Delia Ramirez, D-Ill.

"Tom Homan, the next time you come to #IL03 — a district made stronger and more powerful by immigrants — you better be ready to meet the resistance," she warned.

"You may think Chicago needs to get out of the way of Trump's plans for mass deportation, but we plan to get ALL UP IN YOUR WAY."

Ramirez's comments add to a growing number of statements from Democratic leaders nationwide vowing to oppose or refuse cooperation with Trump's mass deportation plans.

But while Homan may face opposition from Illinois Democrats, there's one Democratic leader willing to work with him: Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker.

"Violent criminals who are undocumented and convicted of violent crime should be deported," Pritzker said at a Northwest Side GOP gathering last week. "I do not want them in my state, I don't think they should be in the United States."

Pritzker, 59, is considered a potential 2028 Democratic presidential hopeful.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think there are three large classes of socialist concern, which are not reducible to each other and which require different types of solutions. I would describe them as follows:

Distributional concerns — Markets tend towards inequality, and thus even in times of abundance fail to allocate resources to people who need them.

Concerns over autonomy — Private control of resources, especially when it is highly concentrated, comes at the cost of the autonomy of those who don't control the resources. As a significant special case of this, private control of the means of production deprives workers of autonomy over their own work, which constitutes most of their waking lives. Concentration of property in the hands of the few leaves most people with no choice but to sell their labor, turning them into workers deprived of autonomy in the above sense.

Humanistic concerns — Markets optimize for specific outcomes and, furthermore, the desirable properties of market economies are predicated on the existence of firms which optimize for profit. In both cases these optimization procedures are premature; they do not factor in the full human condition and thus come at the cost of many things which people find desirable.

In my view, a successful socialist program must at least attempt to address all three of these concerns. Often when debating other socialists, I feel that they err by focusing on some of these concerns to the exclusion of the others.

I have listed these concerns in order of how difficult I believe them to be to solve. Concern (1) can, in fact, be solved relatively easily even within a liberal economic system, by implementing massive redistributive taxes that equalize wealth. I want to stress that this proposal is still radical by the standards of any nation on earth today, but a solution is easy to imagine. And all these problems are interrelated; solving (1), for instance, would go a long way towards remedying (2).

Concern (2) can also, I think, be solved or at least greatly mitigated under a market framework, though not a classical liberal one. Replacing private firms wholesale with worker co-ops would go along way towards addressing (2), and in combination with the above solution for (1) provides I think the easiest to conceptualize vision of what a workable socialist (socialist enough) economy might look like.

Concern (3) is by far the hardest to address—it is in essence just the alignment problem as applied to economic systems. Suffice it to say, the problem remains open.

A common theme I see in debates between certain (usually more liberal-leaning) practically-minded socialists and certain (usually more radical) utopian-minded socialists is that the practical socialist will propose some solution that aims to address (1) and (2), and the more utopian-minded socialist will respond with vague and often not particularly coherent accusations of insufficient radicalism. The practical socialist will often then reply by dismissing the utopian's criticisms as nothing but hot air, as unserious radical posturing. But I think this represents an unfortunate misunderstanding. That utopian is often pointing at something real, even if it is articulated in a way that offends more pragmatic sensibilities. Concern (3) touches on every part of human life, I think it's fair to say, and though the habit of incoherently blaming everything that goes wrong on capitalism is not that useful, it doesn't point at nothing.

The alignment problem is not solved in the general case, but there are things we can change about a system to try and make it more aligned with specific, known goals. So the job of a good socialist (or really, anyone interested in any kind of political reform) should then be to listen to the ways in which people are dissatisfied with their lives, even when articulated poorly, and try to accrue an understanding of the most recurrent and significant ways in which the present system fails to satisfy people. Then you can look for specific tweaks that will more readily accommodate the things people in fact seem to want. But crucially, this task in empirical—you cannot come upon the most desirable tweaks rationally. It's also empirical in a way that is difficult to approach with any kind of scientific rigor. You have to listen to people, and try to understand them on their own terms. You have to try to understand where people are coming from even if they phrase things in a way that you very much dislike, a way that irritates you or makes you feel threatened.

As I've said before, "listen to marginalized voices" is oft-misused, but not actually incorrect as a description of the practical obligations of anyone who wants to consider themself a leftist.

252 notes

·

View notes

Text

when people blame homelessness on "the rich" and propose individualistic solutions that you personally can do to help them I get the sentiment but that understanding is all wrong.

homelessness is a necessity under capitalism. the bourgeoisie and the governments that cater to them want there to be some amount of homelessness because being reminded that you could end up living in squalor and starving to death on the streets keeps the proletariat in check. if you're constantly aware that at any time, your means of sustaining yourself could be ripped away from you without warning, you're much more likely to be an obedient and productive worker who will tolerate any abuse from your employer if it means you can continue to afford a roof over your head when you sleep. as long as our governments are organs of the bourgeoisie which serve their class interests, homelessness will continue to exist.

that's not to say that while we continue living under capitalism, you shouldn't try to help homeless people. giving them however much money you can part with could very well be the difference between life and death for them, but it will not fundamentally change their situation. in order to stop homelessness, we need to forcibly seize control of the means of production and take control of the state to use its powers to improve the material conditions of the proletariat. it is only under a dictatorship of the proletariat that we could allocate the necessary resources to efficiently build free housing for everyone, as under socialism, housing would no longer be a commodity constructed for the purpose of turning a profit, but a necessary piece of infrastructure to provide the people with their basic need of shelter.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

One thought i have about the "students using AI in education" thing is that I think there's two somewhat conflicting impulses here, where our brains are generally quite curious and like to gather knowledge in general ("curiosity"), but also love to find the most resource-saving solution to any task (which some might call "laziness" and others may call "efficiency"). My feeling is that the curiosity-impulse gets activated by unstructured aimless information-gathering, like when you're listening to a lecture on something that you won't be tested on. The "efficiency" mode gets activated when you have a task, and especially if you have time pressure. This is generally a good and useful thing from the perspective of mental resource allocation, but not when the deeper purpose of a task would be "learn more about this topic than what you would strictly need to fulfill the task". To the efficiency-mode, it's always beneficial to take shortcuts, which can include cheating.

I don't think the activation of the efficiency-mode can be prevented in an education system that is task-based and usually puts students under time pressure. I think the education system has to somehow grapple with the fact that our brains in general will always tend towards taking the easiest route and this isnt something you can educate out of people... I don't know how this can be dealt with and what approaches probably already exist somewhere, I don't know anything about pedagogy...

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The AI Revolution in Remote Monitoring and Management is Here!

The RMM Software Market is projected to grow at an astonishing 15.4% CAGR from 2023 to 2030. This rapid growth is driven by the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into remote monitoring and management solutions.

Key benefits of AI-powered RMM:

Real-time monitoring and analysis

Predictive analytics for proactive maintenance

Automated incident response systems

Enhanced security measures

Improved IT efficiency and productivity

As a professional in the IT industry, it's crucial to understand how AI is transforming RMM. By embracing these technologies, organizations can: ✅ Reduce mean time to detect and respond to incidents ✅ Improve predictive analytics for equipment failures ✅ Optimize resource allocation and utilization ✅ Enhance threat detection and security capabilities

Are you ready to leverage AI in your RMM strategy? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments below!

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brazilian cities pursue sustainable strategies to confront climate crisis

Expert argues that tackling the issue demands urban reorganization and the decentralization of economic activity

The announcement by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) at the end of last year that 2024 was the hottest year on record—with the planet’s average temperature now exceeding 1.5ºC above pre-industrial levels—reinforced a critical warning: climate change is no longer just a subject for scientific debate. It must now be embedded in public policy and private-sector action at every level, including local governments and corporations. In Brazil, there is a broad consensus that many municipalities most affected by the climate crisis lack the resources for large-scale interventions. Still, experts interviewed for this report emphasize that cost-effective alternatives are proving successful, and that municipal leaders have a wide range of tools they can deploy in partnership with the private sector and local communities.

As Igor Pantoja, institutional relations coordinator at the Sustainable Cities Institute, explains, a full climate adaptation strategy requires more complex structural changes, particularly for large urban centers. These include reducing emissions through transportation reform, such as electrifying bus fleets and expanding the use of renewable fuels in private vehicles. It also calls for urban reorganization that decentralizes economic activity toward outlying neighborhoods, easing mobility demands and naturally cutting back on transportation-related emissions. However, that doesn’t mean cities need to delay action until such large-scale transformations are in place.

“There are architectural solutions that can be advanced through incentives for designs that favor natural lighting and ventilation, the use of heat-adaptive materials, and even replacing asphalt with cement-based sidewalks in areas that are becoming urban heat islands as temperatures rise,” says Mr. Pantoja. “These are more palliative measures, but they make a real difference, especially when paired with an effective urban tree-planting plan.”

According to Mr. Pantoja, it’s not uncommon to see major cities such as São Paulo announcing bold public transportation electrification goals while simultaneously allocating large sums to outdated infrastructure practices. He points to the R$105 million São Paulo’s city hall spent last year to pave over 19th-century cobblestone streets—an approach he considers misguided. From a climate adaptation perspective, he argues, cobblestone streets are far superior: they retain less heat than asphalt and provide better drainage during heavy rainfall. Unlike impermeable asphalt, the gaps between stones allow water to seep into the soil.

Continue reading.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

In some of the work you’ve done on data centers, you talk about how AI is presented as a climate solution, even as it requires resource-intensive data centers and computing to power it. What do you think is the risk of presenting resource-intensive AI as a solution to climate change? This is something that’s already happening, which is basically the imposition of ecological visions of a few, especially in the Global North with private interests, onto the rest of the world. We can see this operating not only when it comes to data centers, but also lithium extraction. Lithium is used for rechargeable batteries, which is a key component of so-called transition technologies, such as electric vehicles. If we want to design a transition towards new forms of energy or less carbon-intensive energies, we need to cooperate with these communities and a very important actor are the ones that are participating in the AI value chain. Companies have a big interest in hiding this value chain, in making sure that these communities don’t have a voice in the media, in regulatory discussions, and so on, because this is crucial for their business model and for the technical capacities that they need. There is a big interest in silencing them. This is why they don’t provide information about what they do. It’s also very important that as we discuss AI governance or regulation, we ask how we can incorporate these communities. If you look at what’s happening in Europe, there is upcoming regulation that is going to request that companies provide some transparency when it comes to energy use. But what about something more radical? What about incorporating these communities in the very governance of data centers? Or if we really want more just technologies for environmental transition, why not have a collective discussion, incorporating actors from different contexts and regions of the world to discuss what will be the most efficient — if you want to use that word — way of allocating data centers. In the case of indigenous communities in the Atacama Desert, water is sacred. They have a special relationship with water. One of the few words that they still have is uma, which stands for water. So how do we make sure that these companies respect the way these communities relate to the environment? It’s impossible to think of any kind of transition without considering and respecting the ecological visions of these groups. I don’t really believe in any technologically intensive form of transition that’s made by technocrats in the Global North and that ignores the effects that these infrastructures are having in the rest of the world and the visions of these communities.

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

hmm. disco elysium

I liked it less than I thought I would.

I guess that's a shame. with the amount of praise the game gets I expected it to absolutely blow me out of the water so even though I did like the game, it's weighed down by the fact that, like, I expected to get a new favourite game, but instead I just... had a pretty good time.

I definitely got pretty frustrated with it during my ongoing thoughts post and I'm not sure how I feel about that frustration in retrospect - in one way it was an expression of my investment in the narrative. in another way it was me being immature and expecting the game to give me what I demanded, and in yet another way it was the game seeming to punish me continuously for making mistakes I didn't even realise were mistakes

it's kinda hard to talk about the game as a whole cause it feels so split between stuff like the character writing, which is really good, and the more "gamified" aspects like the skill checks, which feel... clunky in my opinion, due to the chance-based nature of them. it feels like I'm enjoying an incredibly good visual novel which I then occasionally have to pause in order to allocate some skills or change my clothes in order to optimise for skill checks, and if I fail a white skill check it can feel like that entire storyline gets put on hold until I find a way to unlock it unless I want to potentially waste skill points (which I didn't want to do, since they felt like an extremely limited resource). the skills themselves are as wonderfully written as everything else and I'm glad they're in the game, but the %-based checks - particularly the white checks - just feel... rough. I struggle to come up with a solution here though outside of "rewrite the entire game to basically just be a visual novel in which the player is guided by the skills and must use that plus their own brain to try to figure out the right thing to do in any situation rather than just levelling them up". even then you miss out on the red checks which, on the one hand, avoids the horrible feeling of failing them, but on the other hand, balancing red checks feels like the intended source of most of the game's tension. I got shot twice during the confrontation with the mercs due to ignoring reaction speed my entire playthrough, which frustrated me massively - but I think the single most standout moment of my entire playthrough was having the check to warn kim about the woman attacking him appear, seeing a 97% chance of success, and feeling, for the second time in my entire playthrough, that I'd actually made the right choice in picking the purple starting class.

(the first time was when breaking the news to the wife of the man who fell through the pier and broke his skull on the bench. the third time was when meeting the phasmid at the very end.)

so, idk. frustration getting through one blue check to proceed the story only to be hit by another after getting a tantalising taste of plot progression. relief at being able to succeed at the red checks that really mattered. in retrospect the only red check I'm genuinely upset to have failed is the karaoke. that one hurt

anyway I already mentioned but the character writing is absolutely excellent. not a single miss. kim is my #1 boy (I want to marry him). evrart was a real standout, he's just so slimy but so likeable. I wish we got to talk to ruby more, she seemed really interesting. klaasje is a disaster and I wish her the best after I didn't arrest her (much to kim's frustration). titus took such an interesting swing from basically an antagonist to a friend as both he and I began to trust each other's intentions more. also shoutout to garte I like him he funny

the worldbuilding is also incredible. every time the details of any kind of technology or part of the world was mentioned, I was hanging on and absorbing how cool it all was. the pale absolutely FUCKS as a concept, like, fuck yeah the continents in this world are separated by a giant barrier of... nothing??? that's awesome.

which is why it's kinda weird to me that the story didn't like... do more. the murder mystery aspect was lovely, I love the feeling of having each part of the puzzle slowly slot together, but there's also the whole memory loss kind of part of the plot, and outside of being a framing device for why you, the player, don't know anything about the world, that plot kinda just... goes nowhere? you get told straight away "you are sad and drunk and miss your wife" and then nothing about that fact changes aside from the fact that she was actually your girlfriend. the sheer grief harry seemed to be feeling had me convinced that she'd actually died but like... no, she just left. maybe the entire point is that he really was just an extremely shitty person before his memory got wiped? or maybe I just don't understand romance enough and this is actually meant to be understandable or relatable

I also find the ending to the mystery a little unsatisfying but pretty much better any other possible ending I guess. I'd have disliked if it was ruby, I'd have disliked if it were klaasje, I'd have disliked if it were titus, and the other mercs doing it wouldn't have made sense. so whatever. random guy on an island go

I think, to me, the ending felt like it should have been an inevitable tragedy, or at least deeply bittersweet - maybe I undercut it for myself by taking a 2 day break in between the encounter with the mercs (which felt to me like a horrific disaster that would inevitably result in the union being wiped out by the mercenary company, even though we managed to kill the 3 of them that were there) and actually finishing the game? idk man, I was expecting the ending to be, like, another violent revolution has been inevitably set into motion, the forces of capital are gearing up to attempt to put it down whatever the cost, best case scenario is kim and harry just riding it out somewhere in obscurity after bringing the person responsible for kicking it all off to justice. and then instead I got you did it you arrested the murderer :) good job :) there's some societal unrest but we get to just keep on copper-ing with kim :)

speaking of which I think I largely struggled with the game cause I didn't go in with the mindset of it being a cop game, which it very much is. you can play it unlike a cop (I at least tried to avoid being too much of a cop for most of the playthrough) but the game does expect you to be down with some level of cop-ing. I'm not upset over this but I will admit I was expecting it to be more... subversive I guess? I was expecting it to be cop-critical but instead it's pretty much cop-positive, albeit in a kinda sam vimes discworld way.

not much else to say. art pretty. music good though idk if I'll listen to it much after this? it's mostly very ambient which doesn't tend to hold my attention well. probably not gonna become a hyperfixation but it's not impossible. kim kitsuragi beautiful please marry me. disco/10

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Breaking Down Your Holiday Budget: Where to Spend, Where to Save

The holiday season is a time of joy and celebration, but it can also bring financial stress if you’re not careful. From gifts and decorations to travel and entertainment, the expenses can quickly add up.

However, with the right approach, you can create a holiday budget that allows you to enjoy the festivities without the burden of debt.

Set a Realistic Budget from the Start

Before diving into holiday spending, it’s essential to set a realistic budget. Take a close look at your overall financial situation, including your income, expenses, and any upcoming bills. Factor in your usual monthly costs, such as rent or mortgage payments, utilities, groceries, and insurance, so you have a clear understanding of your financial limits.

Once you’ve established your financial boundaries, work with a financial advisor Sydney to determine how much you can comfortably allocate to holiday spending. Setting a budget will prevent you from overspending and help you avoid financial stress come January.

Where to Spend: Invest in Meaningful Gifts

When it comes to spending during the holidays, gifts are often the biggest expense. However, you don’t need to spend a fortune to show your loved ones you care. Focus on purchasing gifts that are thoughtful and meaningful rather than expensive or extravagant. Personalized items, such as custom jewelry, monogrammed accessories, or handmade gifts, often feel more special than store-bought items and can be purchased within a modest budget.

If you’re worried about overspending on gifts, consider setting a spending limit for each person on your list and stick to it. This will help you avoid the temptation of buying more than you can afford. For bigger family gifts or group presents, consider pooling resources with others to reduce individual costs.

Travel can also be a significant holiday expense. If you plan to travel to visit family or take a vacation, budgeting for airfare, accommodation, and meals is crucial. Early booking can often lead to discounts, so plan ahead to take advantage of lower prices. For a more cost-effective solution, consider staying with friends or family or exploring local travel options rather than flying.

Where to Save: Cut Back on Extras

While it’s important to spend thoughtfully on gifts and travel, there are plenty of areas where you can cut back and still enjoy the season. Here are some tips for saving without missing out on holiday fun:

Decorations

Holiday decorations can be beautiful, but they can also be expensive. Rather than buying all-new decor every year, try reusing items you already own, or make your own decorations. DIY holiday crafts can be a fun, creative way to add festive touches to your home without breaking the bank.

Entertainment

While holiday parties and gatherings are a great way to celebrate, they can also come with added costs, such as catering or buying drinks. Instead of hosting a big, expensive party, consider a potluck-style gathering where guests bring their favorite dishes. You could also opt for low-cost entertainment, such as game nights, movie marathons, or a holiday scavenger hunt.

Dining Out

If dining out is part of your holiday tradition, keep your budget in mind when choosing restaurants. Instead of going to expensive venues for every meal, mix in some home-cooked meals or casual dining experiences. You can still enjoy delicious food and create special moments without the high price tag.

Track Your Spending Throughout the Season

One of the most effective ways to stay on top of your holiday budget is by tracking your spending. This may seem like a small step, but it can have a big impact. Use budgeting apps or spreadsheets to monitor your expenses as you go. By entering your purchases as you make them, you’ll be able to easily see how much you’ve spent in each category and whether you’re staying on track.

If you’re finding that you’re going over budget in one area, like gifts or dining, you can adjust your spending in other areas to make up for it. Consistent tracking ensures that you don’t lose sight of your budget and helps you avoid unnecessary debt after the holiday season.

Consider a Holiday Savings Fund

To avoid financial stress when the holiday season rolls around, start planning ahead by setting up a holiday savings fund. Even a small amount saved each month leading up to the holidays can add up and make a significant difference in your overall budget. Working with a financial advisor Sydney can help you determine a savings plan that works for your lifestyle and goals.

A savings fund will allow you to spread out your holiday expenses and ensure you don’t have to rely on credit cards or loans. This way, you can enjoy the holidays without worrying about paying off debt in the new year.

Creating a holiday budget doesn’t have to mean cutting out all the fun. By spending thoughtfully and saving in areas that don’t compromise your enjoyment, you can have a wonderful holiday season without the financial hangover. Whether it’s investing in meaningful gifts or cutting back on unnecessary extras, staying mindful of your spending will help you end the year on a positive note.

If you need help setting up a realistic budget or managing your finances during the holidays, consulting a financial advisor Sydney can provide you with the expertise and guidance you need. With careful planning, you can ensure a debt-free, stress-free holiday season and set yourself up for a strong financial start to the new year.

8 notes

·

View notes