#Shakespeare First Folio Reception

Text

Shakespeare First Folio Reception, 2023

with David Mills and King Charles III

Photographer: Andrew Matthews

#judi daily!#Shakespeare First Folio Reception#judi dench#dame judi dench#Photographer: Andrew Matthews#with david mills#with King Charles III

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Side note and kind of curious. I know now we revere shakespeare today and romeo and juliet has become so engrained in culture but Im curious what was the reception when romeo and juliet was first releas? Did people at the time predict or think shakespeare would become as big as he is today?

This is such a complex question, but I love it!

First Romeo & Juliet—

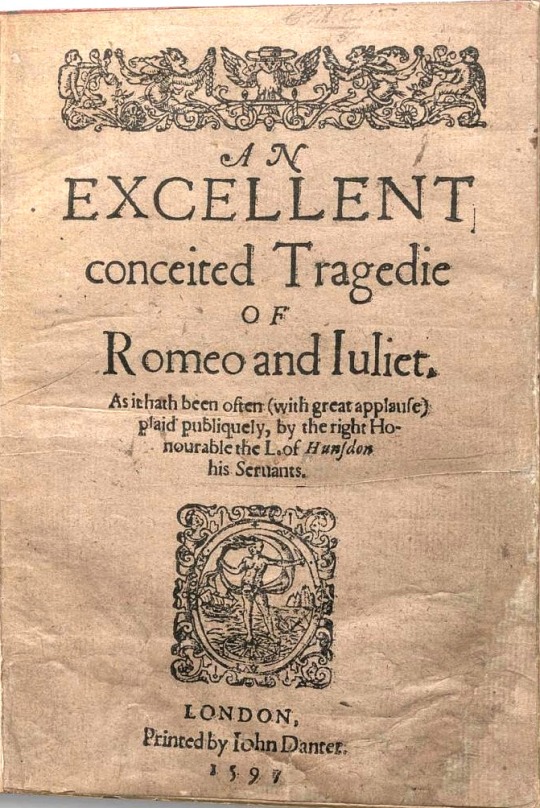

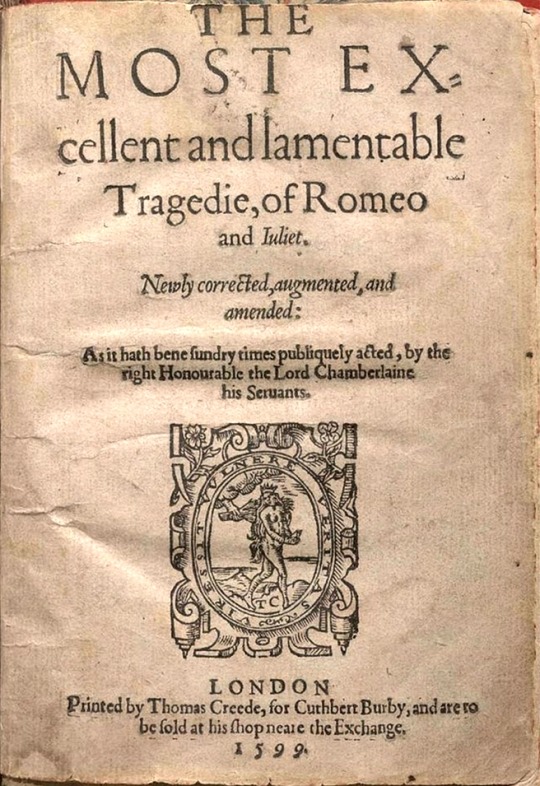

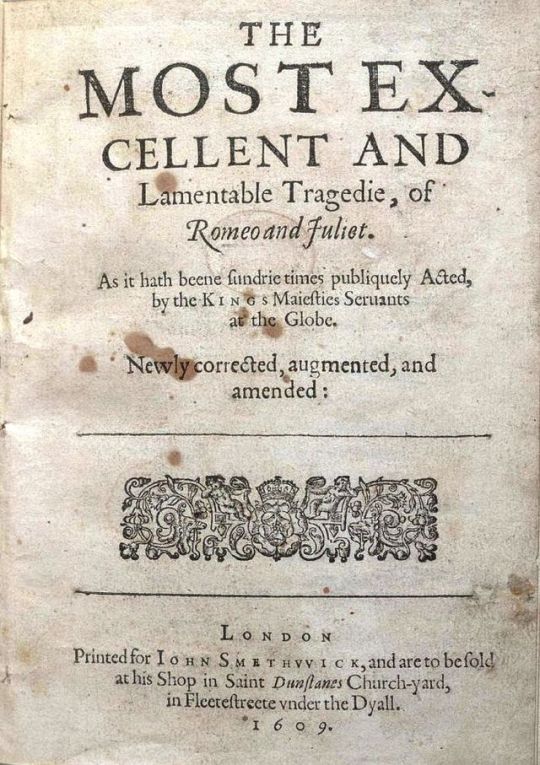

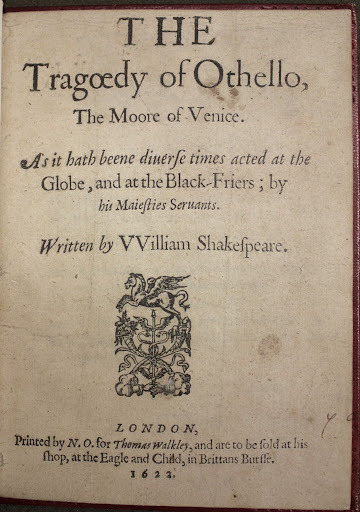

One piece of evidence that contemporaries loved this play is that fact that it was printed at least three times during Shakespeare’s own lifetime, in 1597 when the play was first staged, in 1599, and in 1609. The texts of plays were usually printed in “quarto” form, a term that denotes the size of the book.

You can see that the printer of the first edition advertises the text by blurbing “As it hath been often (with great applause) [played publically].” You want to buy this book because people are loving this play! (This first edition is much shorter than subsequent editions, leading some scholars to speculate that an actor, maybe one who played the nurse, took what he remembered from his own “role” to a printer to set out and publish.

That this play was republished twice more and then a fourth time in quarto in 1623 and a fifth time in folio (a big coffee table book) in 1623 suggests that there was continuing interest in it and that it probably came back to the stage repeatedly.

Now Shakespeare—

Here’s a really quick overview.

William Shakespeare was one of many excellent early modern English playwrights, working during one of, if not thee, most exciting, creative, dynamic eras of English theater. He was lucky to have lived when he did.

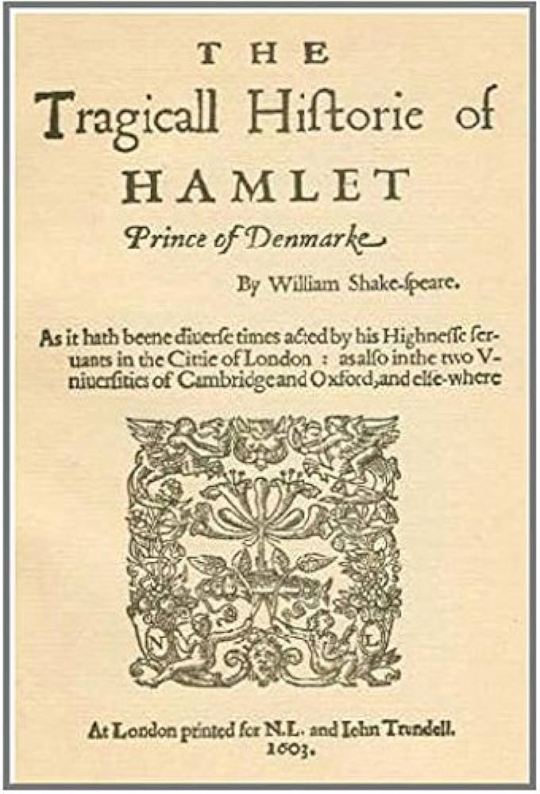

You can see on the covers of some early editions of his other plays that his name gets bigger as time moves on, suggesting that there was increasingly a market for Shakespeare’s works in particular.

This wasn’t typical at all. Generally people didn’t care who wrote the plays; typically early modern plays were the products of collaboration anyway. There certainly wasn’t copyright. Usually the theaters owned the text.

But the idea of the “Author” was emerging during this era, and due in parts to the wild popularity of the theaters, changing market systems, and Shakespeare’s contemporary Ben Jonson’s sheer force of will, that idea of the Author began to attach to playwrights, too.

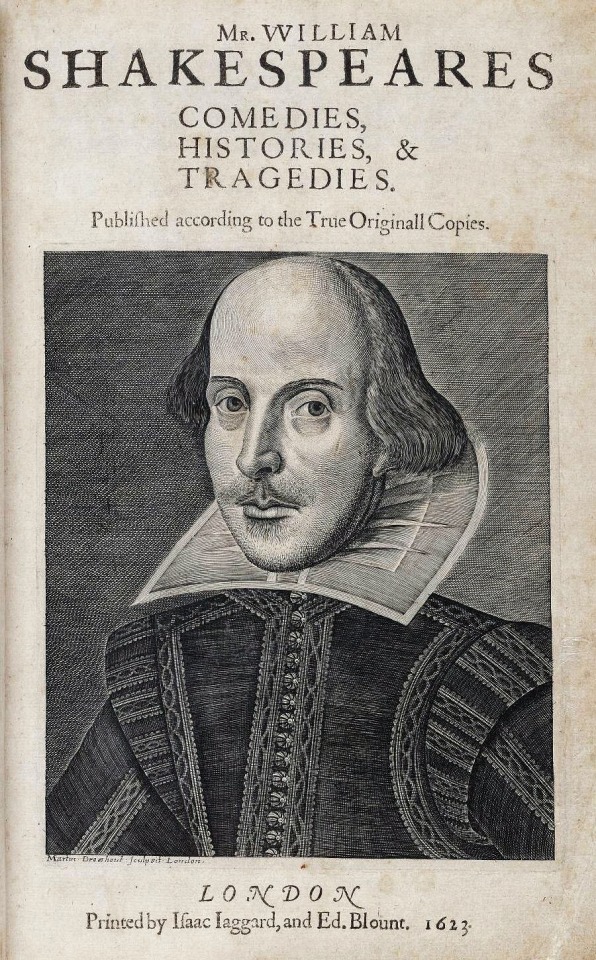

By 1623, Jonson (who had already collected and published his own plays in folio under his name seven years earlier) helped to bring all of Shakespeare’s works together in one expensive volume known today to the First Folio.

Jonson wrote a poem as a preface that included these lines—

Tri'umph, my Britain, thou hast one to show

To whom all scenes of Europe homage owe.

He was not of an age but for all time!

(Link to the whole poem)

Check out the whole poem if you want to see more about how Jonson, with the support of this First Folio, made his contemporary and one-time rival into Shakespeare™️, the one we still know today.

So it’s not only that people predicted Shakespeare would become big; it’s that they set out to make him become big—likely as a way to celebrate British culture, which in the early 17c was still an underdog relative to French, Italian, and the ancient cultures.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Duchess of Edinburgh and The Duchess of Gloucester attend a reception hosted by King Charles III and Queen Camilla at Windsor Castle in Berkshire, to celebrate the work of William Shakespeare, on the 400th anniversary of the publication of the first Shakespeare Folio. July 18, 2023.

📷 getty

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

King Charles III and Queen Camilla host a reception at Windsor Castle to celebrate the work of William Shakespeare,on the 400th anniversary of the publication of the first Shakespeare Folio, 18.072023

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

18 July 2023

Birgitte, Duchess of Gloucester and Sophie, Duchess of Edinburgh attend a reception hosted by King Charles III and Queen Camilla at Windsor Castle in Berkshire, to celebrate the work of William Shakespeare, on the 400th anniversary of the publication of the first Shakespeare Folio at Windsor Castle.

Photos by Andrew Matthews - Pool/Getty Images

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Helena Bonham Carter speaks with King Charles III during a reception at Windsor Castle in Berkshire, to celebrate the work of William Shakespeare on the 400th anniversary of the publication of the first Shakespeare Folio at Windsor Castle on July 18, 2023 in Windsor, England.

#helena bonham carter#king charles iii#appearances#2023#appearances: 2023#shakespeare windsor castle reception 2023#queen camilla

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sir Simon Russell Beale and Dame Harriet Walter performing during a reception hosted by King Charles III and Queen Camilla to celebrate the work of William Shakespeare, on the 400th anniversary of the publication of the first Shakespeare Folio at Windsor Castle on July 18, 2023 in Windsor, England.

Photo by Andrew Matthews - Pool / Getty Images

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

And I gather from your book that Oxford’s Bodleian Library didn’t have any Shakespeare plays before the First Folio because its founder, Thomas Bodley (1545-1613), thought having plays would bring it into disrepute.

Yes, absolutely. The Bodleian Library in Oxford had a deal with the Stationers’ Company that they could have a copy of any book published. But they didn’t take the play books, because Thomas Bodley was explicit in excluding them saying that everybody would laugh at his new library if it was filled with plays.

One of the things the First Folio was trying to do when it was first printed—and it was a bit of an uphill struggle—was to reframe drama as serious literature. It does that by printing it in a format that looks like a Bible rather than like a pamphlet. This isn’t convincing, necessarily, to everybody, but the Bodleian Library do take the First Folio. The format perhaps already makes it looks a bit more respectable than other versions.

Then there’s a hiccup in this story, because probably when the third edition of the book was published with some extra plays in 1663, the Bodleian got rid of its First Folio. It was probably a textbook updating move which, of course, in retrospect looks like a terrible mistake, but was completely a standard thing to do at the time.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Long Post quoting) NY Review of Books:

This year marks exactly four centuries since the publication of William Shakespeare’s First Folio, the giant two-volume set of thirty-six plays that reframed his work in “overtly literary terms,” as Catherine Nicholson puts it in our Sixtieth Anniversary Issue. Nicholson’s writing about Renaissance literature—including in books on the formation of a vernacular tradition (Uncommon Tongues: Eloquence and Eccentricity in the English Renaissance) and on The Faerie Queene (Reading and Not Reading The Faerie Queene: Spenser and the Making of Literary Criticism)—flashes with a rare combination of historical precision and fresh insight. Her essays for the Review so far include considerations of Edmund Spenser, John Milton, and what we’re able to know about childhood in the sixteenth century; a characteristically sharp line on Milton notes that his “nonchronological narrative design” in Paradise Lost “teases us to think, perhaps God is Eve-like.”

Nicholson’s essay on the First Folio, “Theater for a New Audience,” traces the contingencies that have helped to shape our idea of Shakespeare through the big posthumous book of his plays, revealing among other things how our understanding of foundational texts can be enlarged by studying the history of their reception. It also touches on a number of literary questions that could have formed a separate essay on their own, and this week she discussed a few of them with me via e-mail.

-Catherine Nicholson

Jana Prikryl: We have no evidence that Shakespeare, who died in 1616, had anything to do with the First Folio, which was published in 1623. In your essay you criticize Chris Laoutaris’s Shakespeare’s Book for speculating that the Bard himself instigated the folio project. It’s tempting to imagine something of the sort, since otherwise we have a Shakespeare who was recklessly indifferent to the survival of his own work. What’s your own theory for why he, as you put it, “seems to have had no such ambition”?

Catherine Nicholson: I’m not sure we need to think of Shakespeare as recklessly indifferent to the survival of his plays so much as possessed of a different sense of what survival might mean—firstly in the repertory of the King’s Men, and only secondly in the market for print. And survival within a theatrical repertory often entailed a great deal of change: lines, scenes, characters, and so on might be altered, cut, or added as a script was adapted to the resources of the playing company, the shifting tastes of audiences, and the demands of a particular performance occasion. The playwright might be enlisted in making those changes, or he might have no say at all. Since, at the time, playscripts were the legal property of playing companies, publication happened at a still further remove from authorial control. The version of a play fixed in a printed edition might be the one the playwright intended or preferred, or it might simply be the one the printer could get his hands on. And many, many plays never made it into the hands of any printer: the diary of the Elizabethan impresario Philip Henslowe mentions 280 plays, of which thirty survive in print. Some may have been printed and then lost, but it seems clear that most plays written in Shakespeare’s lifetime lived exclusively in the theaters.

That environment must have shaped Shakespeare’s relationship to his work. No doubt he did sometimes find it frustrating to have his words altered without his say-so. Hamlet’s irritable injunction to the players—“let those that play your clowns speak no more than is set down for them”—gives us a glimpse of the sometimes fraught relations between writers and performers, especially those with the most license to improvise on stage. But that speech itself runs quite a bit longer in the 1603 quarto (Q1) than it does in the 1623 folio: in 1603 Hamlet goes on to recite a string of random comic catchphrases exactly like the ones he doesn’t want forced into his own play. I don’t have an opinion on which version of the speech belongs in a modern edition or performance: the folio version is certainly more elegant and concise, but the ironic effect in Q1 is one I cherish; it suggests that Shakespeare was wont to poke fun at any impulse toward authorial control, even his own.

I have a similar response to, say, Sonnet 55, which begins, “Not marble nor the gilded monuments/Of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme….” That poem channels the voices of Ovid and Horace to make an extravagant claim for the undying power of Shakespeare’s verse, and it’s hard to read today without a shiver of appreciation and awe: he was right (so far)! But when I teach the Sonnets, I always point out to students that these are poems that circulated in manuscript for over a decade before making their way (with or without Shakespeare’s knowledge and approval) into print; moreover, they are in a poetic form that already, in the mid-1590s, was a bit passé and in a vernacular almost no one outside of England spoke or read. The idea that these verses would retain their meaning and value for all time—“Even in the eyes of all posterity/That wear this world out to the ending doom”—has got to be shot through with some pathos, implausibility, or even humor.

Can you talk a bit about the kinds of new readings that became available after the plays moved from performance to the page?

In some sense, the shift from playhouse to page must have seemed like an impoverishment: the media of performance are so vivid and multisensory in comparison to the medium of text. One of my favorite recent works of scholarship on early modern drama is Claire Bourne’s Typographies of Performance in Early Modern England (2020), which reveals how painstaking and ingenious early modern printers were in devising typographic conventions to make playbooks legible both as books and as plays. At the turn of the sixteenth century, the resources for communicating dramatic structure and dramatic action were limited: the first playbook printed in England, a Latin edition of Terence’s Comedies, included an editorial note telling readers what an act and a scene were and urging them to imagine actors moving on- and off-stage as they read. By the time Shakespeare’s plays were being published, printers had devised an incredibly sophisticated repertoire of typographic conventions, from act and scene divisions to speech tags, italicized stage directions, printed marks like dashes and pilcrows (the symbol that marks a paragraph break), and woodcut illustrations, all of which helped readers to imagine the text in performance.

But printing a play also creates all sorts of new opportunities for engaging with it, beyond the shared temporality of performance: reading a bit at a time, for instance; stopping to look something up; marking and returning to a favorite passage; noticing the recurrence of an image, phrase, or word across a wide expanse of text; annotating in the margins or copying passages out into a commonplace book. Add those modes of readerly engagement together, and you begin to get something like literary criticism: an approach to a play that can coordinate character and plot with features of the text that would be hard to pause over or even register in performance.

To what degree Shakespeare anticipated or sought that kind of engagement from readers of his plays is an open question. In his 2003 book Shakespeare as Literary Dramatist, the scholar Lukas Erne argues that the length of a number of Shakespeare’s plays suggests he wrote them, at least in part, with print publication in mind, lavishing care on passages he knew would likely never make it on stage. On the other hand, maybe the length of the plays as written reveals that Shakespeare was far less precious about his own words than we tend to be; he knew they might be cut and adapted for performance, and he wrote freely in expectation of that winnowing. In either case, the looser, nonlinear, potentially discontinuous temporality of reading allows for all sorts of lingering and reading across or against the narrative grain that I, at least, can’t fathom doing without. And the First Folio encourages that kind of reading—not simply of each play, but of the plays as a dynamic and interrelated whole.

In the first piece you wrote for the Review, on Edmund Spenser, you called The Faerie Queene “the emblematic textual commodity of an age in which book ownership expanded from the domain of aristocrats and scholars to become a bourgeois expression of taste.” When the First Folio was published twenty-six years later, would you say it was comparable in status?

I’d guess that both the 1590/1596 quartos of The Faerie Queene and the 1611 folio of Spenser’s Works were more immediately recognizable to readers and book buyers as prestige literary commodities. The full title of the latter—The Faerie Queen: The Shepheardes Calender: Together with the other Works of England’s Arch-Poët, Edm. Spenser: Collected into one Volume—takes for granted both the author’s preeminence among English poets and the value of assembling his writings into a unified corpus. Contrast that with the mocking reception in some quarters of the 1616 folio of Ben Jonson’s Works (“Pray tell me Ben, where doth the mistery lurke?” inquired one anonymous wit, “What others call a play you call a work”), which suggests the difficulty seventeenth-century readers still had in conceiving of vernacular stage plays as literature.

But there’s a nearly seventy-year gap between the first and second folios of Spenser’s Works, while the Second Folio of Shakespeare’s plays appears just nine years after the first, in 1632. And by the middle of the eighteenth century, their fortunes have decisively crossed: The Faerie Queene is, increasingly, a book to own—or, perhaps, to study—but not to read, while editions and adaptations of Shakespeare sell in a wide variety of formats and at a range of price points. In that sense, too, textual fixity or bibliographic iconicity isn’t the same as influence or survival: change remains the lifeblood of literary tradition.

I don’t want to give away the brilliant ending of your piece, but its reading of The Tempest made me think of other times in the plays when characters rely overmuch on textual sources: the several letters intercepted in King Lear, the fatefully undelivered letter from Friar Laurence in Romeo and Juliet, the comically bad poems Orlando pins to trees in As You Like It…. Is it too much to say that it seems, in Shakespeare’s worlds, as if things written down are inferior to those acted out?

I don’t know about inferior—Shakespeare is keenly alert to the perils and pitfalls of dramatic reenactment—but certainly subject to error and misapprehension. Sometimes those misapprehensions are disastrous; other times (I’m thinking of poor Malvolio deciphering what he believes to be a love letter from Olivia, in Twelfth Night) they are deliciously comic; occasionally, as with the letter that mysteriously surfaces in the final moments of The Merchant of Venice, restoring Antonio’s lost fortune, they are redemptive. Like Spenser, Shakespeare seems to delight in scripting encounters that anticipate the possibility of his own misreading by others, and misreading is not always figured as a catastrophe; sometimes it offers the wayward path to a happy ending.

#refrigeratormagnets

#shakespeare#william shakespeare#playwright#first folio#plays#dramatist#refrigerator magnets#refrigerator magnet#for educational purposes only

1 note

·

View note

Note

Here's a fun question. In Hamlet's first soliloquy (1.2), which do you prefer: sullied, solid, or sallied? (I've always preferred "solid" (First Folio) myself, but the New Oxford reads "sullied," while the Norton 3rd reads "sallied" (Second Quarto).) Would love to hear your opinion!

Ah, a classic question.

To add to your little list, Q1 has ‘sallied’, the Arden Shakespeare has ‘sallied’ (because it’s the Q2 version), the Oxford Shakespeare has ‘solid’, The New Cambridge has ‘solid’.

My general preference is also for ‘solid’ – It’s the simplest option, and it works best with the rest of the melting and liquid imagery: ‘O that this too too solid flesh would melt, / Thaw, and resolve itself into a dew’ (1.2.129-30).

I wouldn’t preclude the other possibilities though. ‘Sallied’ usefully conveys the sense that Hamlet feels besieged, which fits with my general understanding of his unenviable position. ‘Sullied’, is a possibility because it’s a variant spelling of ‘sallied’, found in other early modern texts of the time (Love’s Labours Lost is one). ‘Sullied’ is often preferred by psychoanalytic readings because it focuses on Hamlet’s sense of contamination by his mother’s remarriage, but for me, it also adds to the sense of being infected by the rotten state of Denmark. Once again, it emphasises Hamlet’s inextricable complicity with his situation.

The benefit of texts written for a predominantly aural reception in an age when not everyone was literate is that homophones are fluid, expansive rather than restrictive. It’s worth remembering that Shakespeare generally writes ‘hearing a play’, not ‘seeing a play’ (reading always came afterwards). And we are talking about the master of puns here. It’s part of the beauty and difficulty of Shakespeare that multiple meanings can exist at once, or each audience member can make up their mind on what meaning they prefer. Naturally, editors have to make a decision and settle for one to put in print, but on some level, it’s not necessary to privilege one meaning over the other.

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter III: My Reading Machine

The word “readies” suggests to me a moving type spectacle, reading at the speed – rate of the present day with the aid of a machine, a method of enjoying literature in a manner as up to date as the lively talkies. In selecting “The Readies” as a title for what I have to say about modern reading and writing I hope to catch the reader in a receptive progressive mood, I ask him to forget for the moment the existing medievalism of the BOOK [God bless it, it’s staggering on its last leg and about to fall] as a conveyor of reading matter. I request the reader to fix his mental eye for a moment on the ever-present future and contemplate a reading machine which will revitalize his interest in the Optical Art of Writing. In our aeroplane age radio is rushing in television, tomorrow it will be a commonplace. All the arts are having their faces lifted, painting, [Picasso], sculpture [Brancussi], music [Antheil], architecture [zoning law], drama [Strange Interlude], dancing [just look around you tonight] writing [Joyce, Stein, Cummings, Hemingway]. Only the reading half of Literature lags behind, stays old-fashioned, frumpish, beskirted. Present day reading methods are as cumbersome as they were in the time of Caxton and Jimmy the Ink. Though we have advanced from Gutenberg’s movable type through the linotype and monotype to photo-composing we still consult the book in its original archaic form as the only oracular means we know for carrying the word mystically to the eye. Writing has been bottled up in books since the start. It is time to pull out the stopper. To continue reading at today’s speed I must have a machine. A simple reading machine which I can carry or move around, attach to any old electric light plug and read hundred thousand word novels in ten minutes if I want to, and I want to. A machine as handy as a portable phonograph, typewriter or radio, compact, minute, operated by electricity, the printing done microscopically by the new photographic process on a transparent tough tissue roll which carries the entire content of a book and yet is no bigger than a typewriter ribbon, a roll like a miniature serpentine that can be put in a pill box. This reading film unrolls beneath a narrow strip of strong magnifying glass five or six inches long set in a reading slit, the glass brings up the otherwise unreadable type to comfortable reading size, and the reader is rid at last of the cumbersome book, the inconvenience of holding its bulk, turning its pages, keeping them clean, jiggling his weary eyes back and forth in the awkward pursuit of words from the upper left hand corner to the lower right, all over the vast confusing reading surface of a columned page.

Extracting the dainty reading roll from its pill box container the reader slips it smoothly into its slot in the machine, sets the speed regulator, turns on the electric current and the whole 100 000; 200 000; 300 000 or million words spills out before his eyes and rolls on restfully or restlessly as he wills, in one continuous line of type, its meaning accelerated by the natural celerity of the eye and mind, [both of which today are quicker than the clumsy hand] one moving line of type before the eye, not blurred by the presence of lines above and below as they are confusing placed on a columned page.

My machine is equipped with controls so the reading record can be turned back or shot ahead, a chapter reread or the happy ending anticipated. The magnifying glass is so set that it can be moved nearer to or farther from the type, so the reader may browse in 6 point, 8, 10, 12, 16 or any size that suits him. Many books remain unread today owing to the unsuitable size of type in which they are printed. Many readers cannot stand the strain of small type and other intellectual prowlers are offended by greater primer. My reading machine allows the reader free choice in type-point, type seen through a movable magnifying glass is not the arbitrarily fixed, bound object we see imprisoned in books, but an adaptable carrier of flexible, flowing reading matter. Master compositors have impressed upon apprentices for years that there is no rubber type. Well, now that the reading machine exists with a strong glass to expand or contract the size of letters, compositors can’t ding on that anymore. Type today can be pulled out and pushed in as easily as an accordion.

My machine for reading eye-adjustable type is equipped with all modern improvements. By pressing a button the reading roll slows down so an interesting part can be read leisurely, over and over again, if need be, or by speeding up a dozen books can be skimmed through in an afternoon without soiling the fingers, cutting a page or losing a dust wrapper. Taken at high gear ordinary literature may be optically absorbed at the rate of full length novels in half hours or at slow speed great pieces of writing may be reread and mused over in half life times if necessary. One so minded may continue to take his reading matter as slowly and dully as he does today in books. The underlying principle of reading remains unaffected, merely its scope is enlarged and its latent possibilities pointed.

To save the labor of changing rolls or records, a clip of a dozen assorted may be put in at one time and automatically fed to the machine as phonograph discs are changed at present. The Book of the Day or Book of the Hour Club could sell its output in clips of a dozen ready to slip into the reading machine. Maybe a bookclub offering a dozen new titles a day would result. Reading by machinery will be as simple and painless as shaving with a Schick razor and refills may be had at corner drug stores, cigar stores, or telephone booths from dawn to midnight.

With the present speeding up of publishing a machine is needed to handle the bulk and cut down the quantity of paper, ink, binding and manual labor now wasted in getting out twentieth century reading matter in fifteenth century book form. The material advantages of my reading machine are obvious: paper saving by condensation and elimination of waste margin space, [which alone needlessly takes up a fifth or a sixth of the bulk of the present day book]; ink saving in proportion, a much smaller surface needs to be covered, the magnifying glass multiplies both paper and ink at no additional cost, the ratio is one part paper and ink to ten parts magnifier. Binding will become unnecessary, small paper pill boxes are produced at a fraction of the cost of large cloth covers; American publishers are discarding covers now to produce more and cheaper books, their next step will be to discard the Book itself in favor of the reading roll. Manual labor will be minimized. Reading will be less costly and may even become independent of advertising which today carries the cost of the cheap reading matter purveyed exclusively in the interests of the advertiser.

All that is needed to modernize reading is a little imagination and a high powered magnifying glass. The Lord’s Prayer has been printed in type an inch high with illuminated initials as long as your nose and bound in plush in elephant folio; also, it has been etched on the head of a pin. Personally I should have been better pleased if Anthony Trollope had etched his three volume classics on the head of a pin. Maybe no more trilogies will be written when Readies are in vogue. Anyway, if they are, they may be read at one sitting.

By photographic composition, which is rapidly taking the place of antiquated methods, type since 1925 has been turned out which is not readable without the aid of a magnifying glass. The English August-Hunter Camera Composing Machine fired the first gun in this revolution five years ago. Experiments with diamond type, like the old Chiswick PreB Shakespeare Complete in one and miniature books of the 64mo Clubs have already shown what a multitude of words can be printed in a minimum of space and yet be readable to the naked eye. Even Cicero mentions having seen a copy of the Iliad no bigger than his finger-nail. Publishers of our day have perfected Oxford Bibles and compressed all the short stories of De Maupassant, Balzac and other voluminous writers into single volumes by using thin paper. Dumb, inarticulate efforts have been made for centuries to squeeze more reading matter into less space, (the Germans since the war publish miniature Z e i t u n g s in eye-aching type to save paper and ink costs) but the only hint I have found of Moving Reading is in Stephen Crane’s title, “Black Riders”, which suggests the dash of inky words at full gallop across the plains of pure white pages. Roger Babson recently listed the needed invention of a Talking Book in a group of a score of ways to make a million. But he missed the point. What’s needed is a Bookless Book and certainly a silent one, because reading is for the eye and the INNER Ear. Literature is essentially Optical — — — not Vocal. Primarily, written words stand distinct from spoken ones as a colorful medium of Optical Art.

Reading is intrinsically for the eye, but not necessarily for the naked optic alone. Sight can be comfortable clothed in an enlarging lens and the light on a moving tape-line of words may be adjusted to personal taste in intensity and tint, so the eye may be soothed and civilized and eventually become ashamed of its former nakedness. Opticians have given many people additional reading comfort through lenses.

We are familiar with news and advertisements reeling off before our eyes in huge illuminated letters from the ops of corner buildings, and smaller propaganda machines tick off tales of commercial prowess before our eyes in shop windows. All that is needed is to bring these electric street signs down to the ground, move the show-window reading device into the library, living and bed-rooms by reducing the size of the letter photographically and refining it to the need of an intimate, handy portable, rapid reading conveyor.

In New York a retired Admiral by the name of Fiske has patents on a hand reading machine which sells for a dollar; it is used in reading microscopic type through a magnifier. Admiral Fiske states: “I find that it is entirely feasible, by suitable photographic or other process, to reduce a two and one-half inch column of typewritten or printed matter to a column one-quarter of an inch wide, so that by arranging five of such columns side by side and on both sides of a paper tape, which need not have a width greater than one and one-half inches, it becomes possible to present one hundred thousand words, the length of an average book, on a tape slightly longer than forty inches”.

Recently the publishers of the New York telephone book owing to the unwieldy increase in the ponderosity of its tomes, considered the idea of using the Fiske machine and printing its product, advertisements and all, in pages three inches tall, in type unreadable by the naked eye. The idea is excellent and eventually will force its way into universal acceptance because the present bulk of phone directories hardly can be expanded unless hotel rooms and booths are enlarged. The inconvenience of searching through the massive volumes of several boroughs has brought New York to the necessity of giving birth to an invention.

But book me no books! In the Fiske Machine we have still with us the preposterous page and the fixity of columns. It is stationary, static, antiquated already before its acceptance, merely a condensed unbound book.

The accumulating pressure of reading and writing alone will budge type into motion, force it to flow over the column, off the page, out of the book where it has snoozed in apathetic contentment for half a thousand years. The only apparent change the amateur reader may bemoan is that he might not fall asleep as promptly before a spinning reading roll as over a droning book in his lap, but again necessity may come to the rescue with a radio attachment which will shut off the current and automatically stop the type-flow on receipt of the first sensitive vibration of a literary snore.

0 notes

Text

Chapter III: My Reading Machine

The word “readies” suggests to me a moving type spectacle, reading at the speed – rate of the present day with the aid of a machine, a method of enjoying literature in a manner as up to date as the lively talkies. In selecting “The Readies” as a title for what I have to say about modern reading and writing I hope to catch the reader in a receptive progressive mood, I ask him to forget for the moment the existing medievalism of the BOOK [God bless it, it’s staggering on its last leg and about to fall] as a conveyor of reading matter. I request the reader to fix his mental eye for a moment on the ever-present future and contemplate a reading machine which will revitalize his interest in the Optical Art of Writing. In our aeroplane age radio is rushing in television, tomorrow it will be a commonplace. All the arts are having their faces lifted, painting, [Picasso], sculpture [Brancussi], music [Antheil], architecture [zoning law], drama [Strange Interlude], dancing [just look around you tonight] writing [Joyce, Stein, Cummings, Hemingway]. Only the reading half of Literature lags behind, stays old-fashioned, frumpish, beskirted. Present day reading methods are as cumbersome as they were in the time of Caxton and Jimmy the Ink. Though we have advanced from Gutenberg’s movable type through the linotype and monotype to photo-composing we still consult the book in its original archaic form as the only oracular means we know for carrying the word mystically to the eye. Writing has been bottled up in books since the start. It is time to pull out the stopper. To continue reading at today’s speed I must have a machine. A simple reading machine which I can carry or move around, attach to any old electric light plug and read hundred thousand word novels in ten minutes if I want to, and I want to. A machine as handy as a portable phonograph, typewriter or radio, compact, minute, operated by electricity, the printing done microscopically by the new photographic process on a transparent tough tissue roll which carries the entire content of a book and yet is no bigger than a typewriter ribbon, a roll like a miniature serpentine that can be put in a pill box. This reading film unrolls beneath a narrow strip of strong magnifying glass five or six inches long set in a reading slit, the glass brings up the otherwise unreadable type to comfortable reading size, and the reader is rid at last of the cumbersome book, the inconvenience of holding its bulk, turning its pages, keeping them clean, jiggling his weary eyes back and forth in the awkward pursuit of words from the upper left hand corner to the lower right, all over the vast confusing reading surface of a columned page.

Extracting the dainty reading roll from its pill box container the reader slips it smoothly into its slot in the machine, sets the speed regulator, turns on the electric current and the whole 100 000; 200 000; 300 000 or million words spills out before his eyes and rolls on restfully or restlessly as he wills, in one continuous line of type, its meaning accelerated by the natural celerity of the eye and mind, [both of which today are quicker than the clumsy hand] one moving line of type before the eye, not blurred by the presence of lines above and below as they are confusing placed on a columned page.

My machine is equipped with controls so the reading record can be turned back or shot ahead, a chapter reread or the happy ending anticipated. The magnifying glass is so set that it can be moved nearer to or farther from the type, so the reader may browse in 6 point, 8, 10, 12, 16 or any size that suits him. Many books remain unread today owing to the unsuitable size of type in which they are printed. Many readers cannot stand the strain of small type and other intellectual prowlers are offended by greater primer. My reading machine allows the reader free choice in type-point, type seen through a movable magnifying glass is not the arbitrarily fixed, bound object we see imprisoned in books, but an adaptable carrier of flexible, flowing reading matter. Master compositors have impressed upon apprentices for years that there is no rubber type. Well, now that the reading machine exists with a strong glass to expand or contract the size of letters, compositors can’t ding on that anymore. Type today can be pulled out and pushed in as easily as an accordion.

My machine for reading eye-adjustable type is equipped with all modern improvements. By pressing a button the reading roll slows down so an interesting part can be read leisurely, over and over again, if need be, or by speeding up a dozen books can be skimmed through in an afternoon without soiling the fingers, cutting a page or losing a dust wrapper. Taken at high gear ordinary literature may be optically absorbed at the rate of full length novels in half hours or at slow speed great pieces of writing may be reread and mused over in half life times if necessary. One so minded may continue to take his reading matter as slowly and dully as he does today in books. The underlying principle of reading remains unaffected, merely its scope is enlarged and its latent possibilities pointed.

To save the labor of changing rolls or records, a clip of a dozen assorted may be put in at one time and automatically fed to the machine as phonograph discs are changed at present. The Book of the Day or Book of the Hour Club could sell its output in clips of a dozen ready to slip into the reading machine. Maybe a bookclub offering a dozen new titles a day would result. Reading by machinery will be as simple and painless as shaving with a Schick razor and refills may be had at corner drug stores, cigar stores, or telephone booths from dawn to midnight.

With the present speeding up of publishing a machine is needed to handle the bulk and cut down the quantity of paper, ink, binding and manual labor now wasted in getting out twentieth century reading matter in fifteenth century book form. The material advantages of my reading machine are obvious: paper saving by condensation and elimination of waste margin space, [which alone needlessly takes up a fifth or a sixth of the bulk of the present day book]; ink saving in proportion, a much smaller surface needs to be covered, the magnifying glass multiplies both paper and ink at no additional cost, the ratio is one part paper and ink to ten parts magnifier. Binding will become unnecessary, small paper pill boxes are produced at a fraction of the cost of large cloth covers; American publishers are discarding covers now to produce more and cheaper books, their next step will be to discard the Book itself in favor of the reading roll. Manual labor will be minimized. Reading will be less costly and may even become independent of advertising which today carries the cost of the cheap reading matter purveyed exclusively in the interests of the advertiser. All that is needed to modernize reading is a little imagination and a high powered magnifying glass. The Lord’s Prayer has been printed in type an inch high with illuminated initials as long as your nose and bound in plush in elephant folio; also, it has been etched on the head of a pin. Personally I should have been better pleased if Anthony Trollope had etched his three volume classics on the head of a pin. Maybe no more trilogies will be written when Readies are in vogue. Anyway, if they are, they may be read at one sitting. By photographic composition, which is rapidly taking the place of antiquated methods, type since 1925 has been turned out which is not readable without the aid of a magnifying glass. The English August-Hunter Camera Composing Machine fired the first gun in this revolution five years ago. Experiments with diamond type, like the old Chiswick PreB Shakespeare Complete in one and miniature books of the 64mo Clubs have already shown what a multitude of words can be printed in a minimum of space and yet be readable to the naked eye. Even Cicero mentions having seen a copy of the Iliad no bigger than his finger-nail. Publishers of our day have perfected Oxford Bibles and compressed all the short stories of De Maupassant, Balzac and other voluminous writers into single volumes by using thin paper. Dumb, inarticulate efforts have been made for centuries to squeeze more reading matter into less space, (the Germans since the war publish miniature Z e i t u n g s in eye-aching type to save paper and ink costs) but the only hint I have found of Moving Reading is in Stephen Crane’s title, “Black Riders”, which suggests the dash of inky words at full gallop across the plains of pure white pages. Roger Babson recently listed the needed invention of a Talking Book in a group of a score of ways to make a million. But he missed the point. What’s needed is a Bookless Book and certainly a silent one, because reading is for the eye and the INNER Ear. Literature is essentially Optical — — — not Vocal. Primarily, written words stand distinct from spoken ones as a colorful medium of Optical Art. Reading is intrinsically for the eye, but not necessarily for the naked optic alone. Sight can be comfortable clothed in an enlarging lens and the light on a moving tape-line of words may be adjusted to personal taste in intensity and tint, so the eye may be soothed and civilized and eventually become ashamed of its former nakedness. Opticians have given many people additional reading comfort through lenses. We are familiar with news and advertisements reeling off before our eyes in huge illuminated letters from the ops of corner buildings, and smaller propaganda machines tick off tales of commercial prowess before our eyes in shop windows. All that is needed is to bring these electric street signs down to the ground, move the show-window reading device into the library, living and bed-rooms by reducing the size of the letter photographically and refining it to the need of an intimate, handy portable, rapid reading conveyor. In New York a retired Admiral by the name of Fiske has patents on a hand reading machine which sells for a dollar; it is used in reading microscopic type through a magnifier. Admiral Fiske states: “I find that it is entirely feasible, by suitable photographic or other process, to reduce a two and one-half inch column of typewritten or printed matter to a column one-quarter of an inch wide, so that by arranging five of such columns side by side and on both sides of a paper tape, which need not have a width greater than one and one-half inches, it becomes possible to present one hundred thousand words, the length of an average book, on a tape slightly longer than forty inches”. Recently the publishers of the New York telephone book owing to the unwieldy increase in the ponderosity of its tomes, considered the idea of using the Fiske machine and printing its product, advertisements and all, in pages three inches tall, in type unreadable by the naked eye. The idea is excellent and eventually will force its way into universal acceptance because the present bulk of phone directories hardly can be expanded unless hotel rooms and booths are enlarged. The inconvenience of searching through the massive volumes of several boroughs has brought New York to the necessity of giving birth to an invention. But book me no books! In the Fiske Machine we have still with us the preposterous page and the fixity of columns. It is stationary, static, antiquated already before its acceptance, merely a condensed unbound book. The accumulating pressure of reading and writing alone will budge type into motion, force it to flow over the column, off the page, out of the book where it has snoozed in apathetic contentment for half a thousand years. The only apparent change the amateur reader may bemoan is that he might not fall asleep as promptly before a spinning reading roll as over a droning book in his lap, but again necessity may come to the rescue with a radio attachment which will shut off the current and automatically stop the type-flow on receipt of the first sensitive vibration of a literary snore.

0 notes

Text

Helena Bonham Carter attends a reception to celebrate the work of William Shakespeare, on the 400th anniversary of the publication of the first Shakespeare Folio at Windsor Castle on July 18, 2023 in Windsor, England.

5 notes

·

View notes