#Shanhaijing

Photo

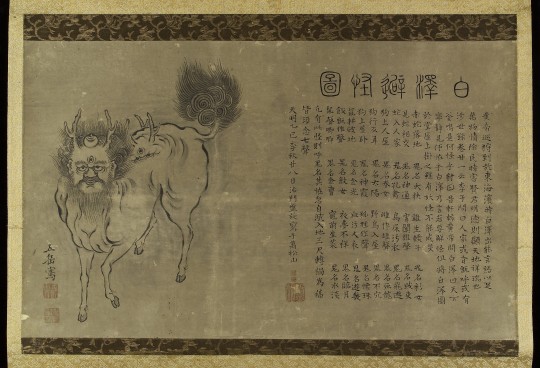

Haozhi (Brave pig), the 229th Known One.

“Fifty-two li west stands Bamboo Mountain, whose summit contains many tall trees. There is an abundance of iron on its northern slope and a plant here named the Yellow Guan-Plant. Its form ressembles that of an ailanthus, while it’s leaves ressemble those of the hemp plant with white flowers and blood-red fruit. Adding it to a bath will cure itching, and it can also cure tumors.

The Bamboo River emanates from here and flows northward into the Wei. Along its northern banks grows an abundance of arrow-bamboo and dark green jade. The Cinnabar River emanates from here and flows southeast into the Luo River. Much rock crystals and many Human-Fish are found in it. There is a beast here whose form resembles a pig with white bristles with black tips as large as hairpins. It is called the Haozhi.” - Guideways Through Mountains and Seas

#i love how reading this book feels like a map#full of adventure wildlife and ressources#Shanhaijing#folklore#China#Asia#Haozhi#Brave pig#pig#porcupine#chimera#monster#bestiary#creature design#ink#Guideways Through Mountains and Seas#916#octem 115#aqva 4#the Known Ones

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yu the Great and Sun Wukong's Staff

This is my answer to the following reddit question:

Did the Ruyi Jingu Bang, as a tool used by Da Yu, exist before the novel?

Monkey's golden-hoop iron staff can be traced to the khakkhara and iron rod respectively used by his precursor in the 13th-century JTTW. The story doesn't mention anything about Yu the Great. The demi-god's connection to the staff is, as far as I know, unique to the standard 1592 edition of JTTW.

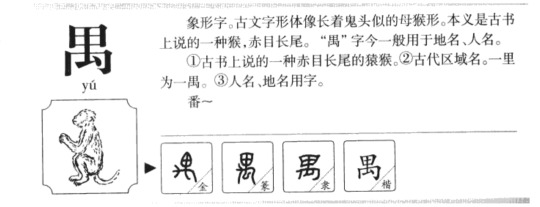

This association probably came about in a couple of ways. For example, there is a Chinese graphic similarity (and possible totemic connection) between Yu and a specific kind of monkey:

The generic Chinese primate names have identical pronunciations or spellings to those of the earliest Chinese emperors. For instance, the character 猱 (Nao) is considered as the ancestral name of the royal family of Shang dynasty (商朝 ca. 1600–1050 BCE) (Cao, 1997; Wang, 2001). This word is used to denote a primate species that is good at climbing. Similarly, the character 禺 (Yu) represents a long-tailed monkey. This word is the same as the character 禹 (Yu), a legendary emperor well known for his brilliance in regulating floodwater (Huang, 2011). This association between primates and the earliest emperors indicates a possible totemic status for primates (Niu, Ang, Xiao, et al., 2002, p. 91).

(The aforementioned Yu (禺) monkey was apparently well-known, for it is referenced several times in the Classic of Mountains and Seas (Shanhai jing, 山海經, c. 4th-century to 1st-century BCE), a popular Chinese bestiary, in order to indicate the shape and size of certain primate-like animals (Strassberg, 2002, pp. 83, 84, 91, 99, 104, 122, 123).)

Also, Yu is known for imprisoning Wuzhiqi (無支奇 / 巫支祇), a monkey flood demon, beneath a mountain in Tang and Song-era folklore. This likely influenced Sun Wukong's punishment under Five Elements Mountain.

Therefore, all of this probably led to the author-compiler of the 1592 JTTW associating Monkey's staff with Yu the Great and his efforts to end the world flood.

Sources:

Niu, K., Ang, A., Xiao, Z. et al. (2002). Is Yuan in China’s Three Gorges a Gibbon or a Langur? International Journal of Primatology, 43, 822–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-022-00302-1

Strassberg, R. (2002). A Chinese Bestiary: Strange Creatures from the Guideways Through Mountains and Seas. University of California Press.

#Da Yu#Yu the Great#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Journey to the West#JTTW#Wuzhiqi#flood demon#monkey#Shanhaijing#Classic of Mountains and Seas#Magic Staff#Ruyi jingu bang#Gold-banded staff#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

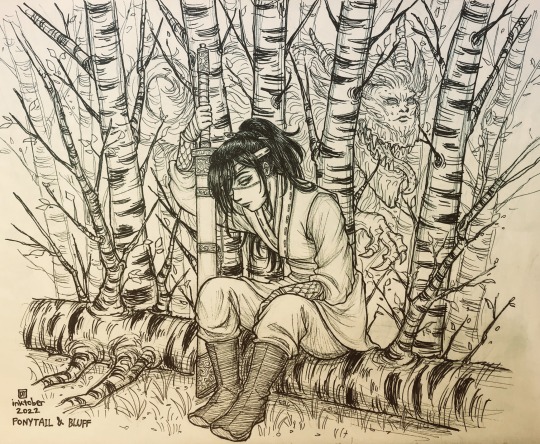

Inktober days 19 & 20: PONYTAIL and BLUFF

In the ancient Chinese text, Classic of Mountains and Seas (山海经), it’s written that on one remote northeastern mountain, there lives a beast that has the face of a human, with a body resembling a large yellow swine, swinging a long reddish tail…and this beasts’ human face can cry like a human baby, luring into its slavering jaws unwitting victims concerned about some lost child.

And this creeped the living daylights outta me when I first read it, so of course I had to draw something about it 😂 go slay the beast, bluffing ponytailed monster-slayer!

#inktober#inktober2022#art#illustration#drawing#inkart#inkdrawing#lineart#traditionalart#blackandwhiteart#sketchbookart#sketching#shanhaijing#山海經#山海经

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

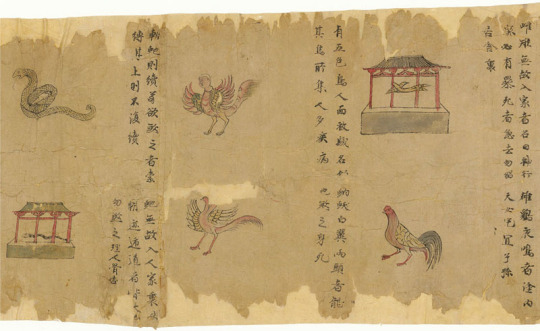

"Shan Hai Jing": a nine-headed phoenix (colored Qing dynasty edition)

#china#classicofmountainsandseas#cina#shanhaijing#librodeimontiedeimari#mythology#chinesemythology#liuxiang#phoenix#nineheadedphonenix#nine-headedphoenix#illustration#chinesemythologicalgeography#qingdynasty#qingdynastyedition

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

キサキ by 苏翼丶 on pixiv

1 note

·

View note

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

1000 followers special: the history of the hakutaku

I recently hit a major milestone. It would appear that over a thousand people apparently want to see more on their dashboards. To celebrate, I decided to go back to the roots of this blog. While I doubt many of you remember it, some of my first posts were complaints about Touhou fanworks failing to account for the fact that the hakutaku was not a boogeyman, but a good luck charm.

In this article, I will explain how come, what exactly the role of an "auspicious beast" entailed, and how different people utilized the story of the hakutaku through history. I will also check how does the Touhou portrayal compare to the historical sources - though that's not the only case of modern reception you will be able to learn about.

As usual, more under the cut.

The earliest history of the hakutaku

As in the case of many other Japanese mythological beings, the history of the hakutaku actually starts in China. The creature was originally known as baize (白澤); hakutaku is simply the Japanese reading. The name can be literally translated as “white marsh”, but how it initially developed is unknown.

Donald Harper argues that baize can effectively be considered a deity. For what it’s worth, there is clear evidence that it could be invoked in theophoric names in the first millennium. The first known case is a certain Zhang Zhongkui (張鍾葵; obviously, his old name is related to the well known figure of the demon queller Zhong Kui) from Northern Wei, who was renamed Zhang Baize (張白澤) by emperor Xianwen. Crown prince Xiao Zhangmao of the Southern Qi was nicknamed Baize, too. Multiple other examples are apparently known, but sadly I was unable to track down any information beyond a confirmation they existed.

Generally speaking, the baize played an apotropaic role. Bernard Faure argues that the creature effectively fulfilled many of the roles of the fangxiangshi, a class of ancient exorcists. Pictures of it could be hung in houses to ward off malign spirits and misfortune. Textual sources indicate this custom was widespread among various social strata. Images of the baize could also be embroidered on clothes, banners and other items. An interesting practice tied to this is documented in sources pertaining to the life of empress Wei from the Tang dynasty. Reportedly her younger sister Qiyi (七姨) slept on a pillow with a depiction of the baize to ward off malicious spirits.

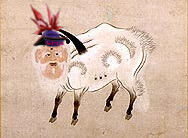

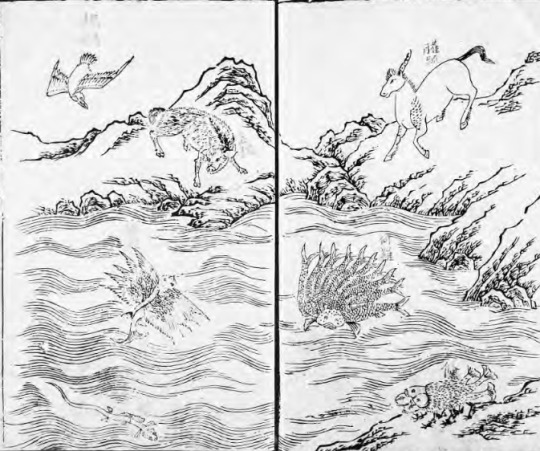

A typical illustration of various creatures from the Shanhaijing (from Richard E. Strassberg's translation; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

While the Tang period is when the belief in baize flourished, the creature was actually older. The first references have been dated to the fourth century. Sometimes even in academic publications you can find claims that it is as old as the Shanhaijing, but this is a mistake. It is true that copies of Shanhaijing which mention the baize exist, but they were only produced in the Ming period and the description was likely sourced from a contemporary encyclopedia, Sancai Tuhui. It is not impossible that the baize ultimately did originate before the Six Dynasties period, but this cannot be proven conclusively.

From Baopouzi to Dunhuang manuscripts: Baize, the Yellow Emperor and the Baize Tu

The first certain attestation of the baize has been identified in Ge Hong’s Baopuzi, which you might remember from my Ten Desires and Zanmu articles. In the section dedicated to the Yellow Emperor, the author states that in addition to his other famous deeds, this legendary ruler recorded the words of the baize.

A more detailed account of this event in preserved in a more recent source, the Yunji Qiqian, specifically in the chapter Xuanyuan benji (軒轅本紀; “Basic annals of Xuanyuan”, ie. the Yellow Emperor). It relays how the Yellow Emperor encountered the baize on Mount Huan (桓山) during a hunting expedition to the eastern frontiers of his kingdom, close to the sea. The creature appeared before him to share esoteric knowledge. It relayed that there are eleven thousand five hundred and twenty types of malign beings, the “spectral prodigies” (精怪, jing guai), in the world, and explained how people could protect themselves from each of them. There’s no real theme to the creatures mentioned: they include animal spirits, spirits of places and objects (for example a stove), as well as various beings which can be broadly described as genius loci. The key to overcoming them was to know their true names. This is not a belief unique to the baize tradition. The Yellow Emperor ordered this to be written down so that this knowledge can be preserved and further disseminated.

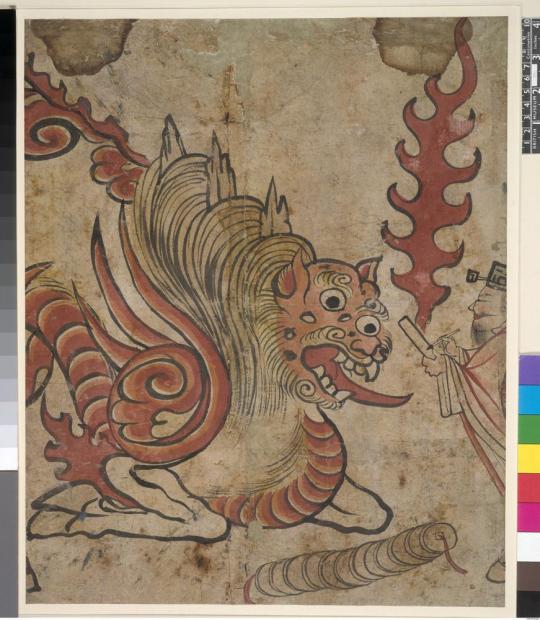

The compilation of baize’s advice came to be known as the Baize Tu (白澤圖), literally “Diagrams of White Marsh”. This tradition must predate Ge Hong, as he mentions the Baize Tu as a work which can be consulted to gain additional insights when it comes to repelling demons. However, he does not connect it with the Yellow Emperor legend directly. Multiple other sources attest that various variants of this treatise actually existed. Song shi (宋史; “History of the Song”), attributes its composition to a certain Li Chunfeng (李淳風; 602–670). Despite apparently relatively wide circulation, every single version of this work is now lost, save for a ninth or tenth century fragment discovered in Dunhuang, the so-called Baize Jingguai Tu (白澤精怪圖), “White Marsh Diagram of Spectral Prodigies”. It was originally identified by Jao Tsung-i in the 1960s, around 60 years after discovery. The surviving sections describe and depict some of the, well, “spectral prodigies”, as promised by the title, as you can see below:

Illustrations sourced from a recent reprint of Jao Tsung-i's article, via Brill; reproduced here for educational purposes only.

Other manuscripts from Dunhuang mention the baize alongside Zhong Kui in the context of new year celebrations. As both of them were believed to keep nefarious forces at bay through different methods, it presumably felt natural to invoke both at once.

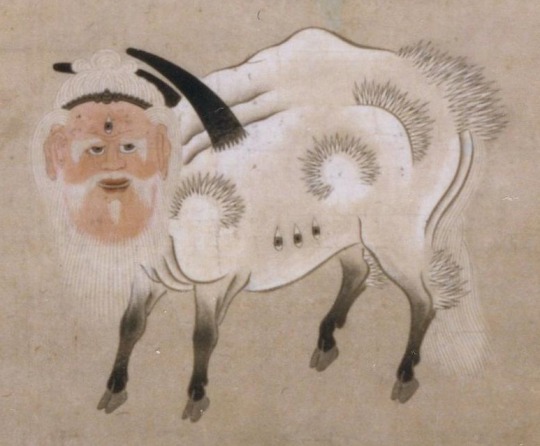

The Dunhuang texts discussing the baize do not contain any images of the creature. However, the exact same site did provide us with a depiction of it, most likely:

The supposed baize painting from Dunhuang (British Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

While the enormous creature in painting above was initially interpreted as some sort of longma, according to Donald Harper its distinctly cow-like shape indicates it should be interpreted baize. The human figure is presumably a scribe, which might indicate we’re dealing with a pictorial version of the legend about Yellow Emperor’s encounter with the baize. After all, someone had to be present to write the creature’s advice down, as requested. The string of coins might be there to provide the image with further apotropaic qualities - the use of coins as talismans is a well established part of new year customs dating as far back as the Tang period. That’s actually where the modern custom of giving kids money in red envelopes comes from.

While the supposed baize painting is a unique and remarkable work of art from a modern perspective, it was likely not regarded as such when originally made. At some point parts of it have been cut, and a Buddhist woodblock print has been pasted on top of it (obviously they were separated during restoration). Before that it was presumably meant to serve as an ephemeral amulet, discarded after it had served its purpose.

This obviously does not diminish its value as a historical source. History is not just just about grand codes of law or royal declarations, as the fact that the study of the culture of some of the oldest states rests largely on the equivalent of receipts and school exercises. I guarantee that in a few hundred years trivial newspaper articles will similarly be the subject of serious inquiries.

Buddhist reception of the baize

A Chinese depiction of Manjushri (wikimedia commons)

Baize also occurs in Buddhist sources from the Tang period, where the creature is linked to Manjushri. This was rooted in a new development, namely the reinterpretation of this bodhisattva as a figure associated with auspicious signs, rather than his traditional domain, wisdom. Additionally, it was presumably easy to link an at least semi-divine distinctly bovine creature with the custom of referring to certain buddhas and bodhisattvas with the title of “ox king” (牛王).

The first source to mention the association between the baize and Manjushri is a text written by the Buddhist monk Kuiji (632-682), a disciple of the famous Xuanzang. He states that a cow giving birth to a baize is one of the signs that the rebirth of Manjushri draws closer, similarly to a feng bird hatching from a chicken egg, a horse giving birth to a qilin, or an elephant with six tusks appearing. As you can see, the baize is in esteemed company here. For instance, the qilin was said to only appear to virtuous rulers, while the six-tusked elephant appears in the traditional account of the historical Buddha’s birth.

This tradition is also documented in the Sutra of Manjushri’s Auspicious Signs (文殊吉祥經,Wenshu Jixiang Jing), only known from a small fragment. Here the birth of the baize is actually elevated to the rank of the final omen in the cycle preceding the appearance of the eponymous bodhisattva. The text also alludes to the baize’s apotropaic role as a figure meant to ward off demons. Additionally it states that the creature normally lives in heaven, but can choose to reincarnate on earth, among humans - obviously to foretell the birth of Manjushri. Apparently all of the “auspicious beasts and numinous birds” rejoice when that happens.

The decline of baize in China

It seems that after the Tang period, the popularity of the baize declined in China, mostly at the expense of Zhong Kui. It was not a complete disappearance, but while the early baize largely belonged in the domain of popular belief, later on most attestations reflect courtly and scholarly interests only.

For unknown reasons at some point baize’s iconography was reinvented, with the ox-like form replaced by one with leonine features. The Southern Song encyclopedia Gujin Hebi Shilei Beiyao outright suggests baize is simply a term referring to lions. In a source from the Yuan period, a banner depicting the baize as a creature with “tiger head, red hair with horns, dragon body” is mentioned, though, so evidently not everyone accepted this rationalization.

Some references to the baize can still be found in texts from the Qing period. One example is a poem by a Tiantai Buddhist monk, Zhang Hengwu (張亨梧; 1633–1708), based on the well established Yellow Emperor narrative. In his version, the legendary ruler specifically seeks the baize while traveling to the east.

Japanese reception of the baize

The baize/hakutaku, as depicted by Gusukuma Seihō (wikimedia commons)

Baize’s illustrious career was not limited to one country. At some point, the creature was also introduced to Japan. Most likely it reached the archipelago either through Buddhist sources or Sa Shouzhen’s (薩守真) treatise Tiandi Ruixiang Zhi (天地瑞祥志; “Treatise on auspicious signs in heaven and earth”). The latter was transmitted to Japan as early as in the ninth century, and it is possible the baize - or rather the hakutaku, following the Japanese reading of the name - was already recognized as an apotropaic creature in Japan at this time. By the 1200s, the belief in its auspicious power was well established. Tachibana no Narisue states in Kokon Chomonjū (1254) that in the private chambers of the emperor (Seiryōden) there was an “oni room” (鬼の間, oni no ma) in which a painting of hakutaku repelling demons was displayed.

Japanese art did not adopt the younger Chinese convention of portraying the creature as leonine. It was not entirely unknown, with the best known example being an illustration from the Edo period encyclopedia Wakan Sansai Zue, but it never became popular. The ox-like shape remained the norm. The iconography of the hakutaku is thus pretty consistent: the body of a white ox, the head of an old man with a vertical third eye and sometimes a pair of horns, plus additional eyes and horns on the flanks. The human head might be a Japanese innovation, reflecting the ability of human speech ascribed to the creature.

Probably the single best known Japanese depiction of the hakutaku is that painted by Gusukuma Seihō (1614-1644). He was the official painter of the royal court of Ryukyu and somewhat of an international celebrity in his times, considering his work was renowned not just in his homeland, but also among Chinese envoys to Ryukyu and by the Tokugawa court. Sadly, this is his only surviving painting, unless there are more in private collections inaccessible to historians (this is not impossible, and reportedly a second hakutaku painting attributed to him belonged to a private Okinawan collector in the 1920s at the very least).

As noted by Bernard Faure, hakutaku was effectively a visual reversal of Gozu Tenno, who could be portrayed as a man with a bull’s head, and often played a similar apotropaic role. Additionally, through the title of “ox king”, which recurs in Japanese sources, hakutaku can be indirectly linked to many other major figures of esoteric Buddhism, including Daiitoku Myōō, Ishana and Yama. If you really want to stretch it you can even make a case for parallels with Matarajin, considering both his demon-repelling properties and his association with oxen.

Hakutaku and baku

The baku, as depicted by Hokusai (wikimedia commons)

As mentioned by the sixteenth century author Naotomo Isshiki (一色直朝), in addition to warding off demons hakutaku was also believed to eat bad dreams. This indicates confusion or conflation with the baku. The two are also treated as synonymous in Gen’i Nagoya’s (名古屋玄医; 1628-1696) Minkan Saijiki (民間歲時記 ; “Everyman’s record of the year and seasons”), which is about a century younger. He pretty clearly describes the hakutaku rather than the baku, since the “diagrams” known from Chinese sources and the Yellow Emperor legend are both mentioned. The original tradition must have been well known at least among

“King baku” (Gohyaku Rakanji website; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

By far the best example of this phenomenon of conflationg baku and hakutaku a statue from Gohyaku Rakanji (“Temple of the Five Hundred Arhats”) which depicts a hakutaku, but is referred to as “king baku” (獏王) today. It was originally sculpted by the monk Shōun (松雲; 1648 - 1710) in the late seventeenth century, much like the rest of the still displayed statuary. I actually first learned about the hakutaku in 2012 or so from the baku article on Zack Davidsson’s blog Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai, which mentions the Gohyaku Rakanji statue and the conflation between the two creatures. Lafcadio Hearn also asserted hakutaku is simply another name for baku.

Hakutaku in the Edo period

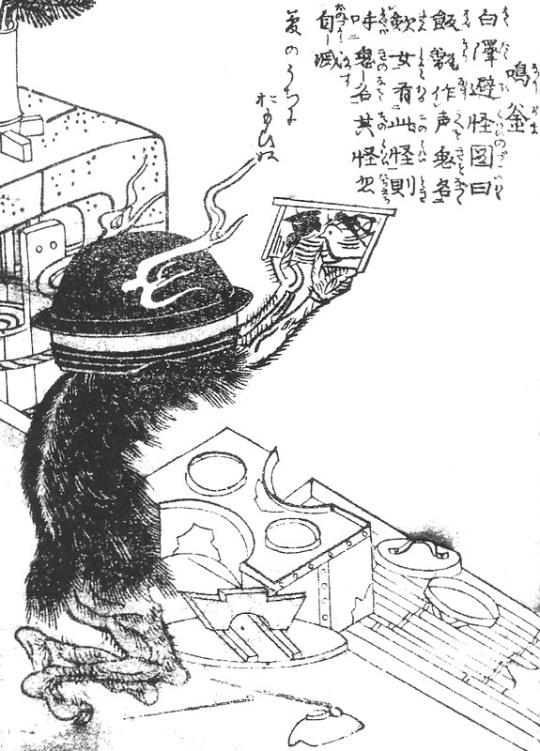

For unknown reasons the popularity of hakutaku increased in the Edo period, especially over the course of the eighteenth century. Sekien Toriyama included it in one of his compilations of yokai illustrations. He also refers to the hakutaku (or rather to baize, as the note is in Chinese) in his description of the narigama (a type of tsukomogami), stating that the way to get rid of this creature’s forerunner renjo was shared with humans by the auspicious beast.

The norigama illustration in mention (wikimedia commons)

Most importantly, amulets depicting hakutaku were used for protection while traveling and to ward off illness and misfortune. This custom relied on a Chinese source, the twelfth century treatise Sheshi lu (涉世錄), literally “Record of Experiencing the World” which prescribed hanging an image of the baize at home to prevent misfortune. This work is now lost and the relevant passage, known from quotations in Japanese sources, is its longest surviving section.

The increase in apotropaic usage of hakutaku images lead to the creation of the so-called White Marsh Diagram to Repel Ominous Prodigies (白澤避怪圖, Hakutaku Hikai Zu). This term refers to talismans consisting of a painting of the creature and a short version of the already discussed Yellow Emperor legend. It culminates in a scene with no Chinese forerunner, in which the hakutaku announces to the emperor that hanging an image representing it in a house protects from, well, “ominous prodigies”. A list of some of them was also provided.

The Zen monk Hakuin (白隱; 1686–1768) already describes the hakutaku talismans as popular, though he stresses neither he nor the people using them were aware of their origin. The precise history of their development remains unknown to researchers too. Seemingly they couldn’t be older than the seventeenth century at the earliest. Why did apotropaic images of hakutaku aimed at general population resurface in Japan centuries after their use ceased in China is unknown. Their spread might have been tied with the practices of the shugenja, as many of them were distributed among pilgrims visiting Mt. Togakushi, a well known center of the Shugendo tradition.

The most famous apotropaic depiction of hakutaku (wikimedia commons)

A well known example of the White Marsh Diagram to Repel Ominous Prodigies, presently in the collection of the British Museum, was painted by Gogaku Fukuhara, with the text provided by the Buddhist monk Bansen (盤旋). Based on the colophon of their work, it was completed on October 30, 1785. It’s worth highlighting that it situates the creature in Buddhist context (if that was not clear enough from the involvement of a monk), as the structure on its head is pretty clearly a wish-fulfilling jewel. To my best knowledge, this has no forerunners among Chinese depictions. This specific work of art has been characterized as a “deluxe” example of a talisman, painted and calligraphed by hand, presumably made with a connoisseur in mind. Most people relied on cheap woodblock prints instead for their hakutaku needs. These were obviously perishable, so few of them survive, though two of the woodblocks used to make them, both from Togakushi, have been preserved.

Notably, hakutaku talismans were employed during the cholera epidemic of 1858. Reportedly in Tokyo people placed them on their headrests before going to sleep. I sadly did not find any source explaining whether this was a conscious revival of the Tang custom discussed earlier, or if the similarity is entirely accidental.

Hakutaku talismans were also utilized by travelers. this custom is documented in an Edo period book which can be considered an early example of a travel guide, Ryokō yōjinshū (旅行用心集; “Precautions for travelers”) by Yasumi Roan (八隅蘆菴). It was published in 1810 as part of what can be described as an early case of a domestic tourism boom resulting in the flourishing of travel literature.

Much of the advice is surprisingly timeless, for example to abstain from leaving graffiti and stickers at landmarks such as temples and shrines, but also trees and sufficiently big rocks. I have to say the suggestion that a halberd is too heavy to carry around while on a trip is pretty solid too. Roan has many other great suggestions, but ultimately this is not an article about him, so they have to wait for another time. When it comes to the hakutaku, he states that travelers should equip themselves with images of this creature and the five great mountains of China (gogaku) to ward off spirits, but also wild animals and mundane accidents.

Last thing which needs to be discussed here is that in addition to the apotropaic paintings, hakutaku was also sometimes portrayed in the form of a netsuke. However, such depictions are apparently not common.

A hakutaku netsuke from the British Museum (photo proided by my friend Li)

The modern reception of the hakutaku

It remains unclear when apotropaic depictions of the hakutaku ceased to be made. It seems to me that it can be plausibly assumed it occurred in the Meiji period, but I have no solid evidence. However, the hakutaku was not entirely forgotten.

To my best knowledge, the single highest profile portrayal of a hakutaku in modern fiction is still Keine from Imperishable Night. What little spotlight she received paints an image remarkably close to the genuine accounts: as we learn from her bio, “she loves humans and always tries to help them” and she is pretty consistently portrayed as a staunch protector of the villagers and Mokou. The fact she’s not fully human doesn’t seem to be a mystery in-universe, and she is evidently accepted nonetheless. This doesn’t seem to be universally acknowledged in fanworks which is puzzling to me. There are dozens of yokai which are little more than boogeymen, but there are very few distinctly auspicious ones, and I prefer the canon approach of emphasizing that Keine and the village community mutually like each other.

Keine’s role as a teacher presumably is meant to be a nod to the lecture about malign spirits the baize delivered to the Yellow Emperor. I am a huge fan of specifying the school she teaches at is a terakoya; whether ZUN was aware of it or not, hakutaku talismans and temple schools are both expressions of Edo popular culture, so the theme does more or less fit together.

What little we learn about hakutaku in Touhou in general from Perfect Memento in Strict Sense also draws from historical sources. I will however note that as far as I can tell that revealing that a new ruler is going to be virtuous is a role assigned of various “auspicious beasts” like qilin, longma and so on in general rather than exclusively to the baize/hakutaku. There are also no legends about a hakutaku meeting with any Japanese rulers, even though most of Keine’s spellcards reference the imperial family (or attempts at overthrowing it; is she an anti-monarchist?).

The rest of Keine's character seems to be ZUN’s invention. The only account of the hakutaku (well, baize’s) origin makes it clear the creature is a type of supernatural cattle, not a human, and there is obviously no such a thing as a “were-hakutaku”. I presume this was meant to highlight her human side and tie her more closely to the moon theme of Imperishable Night, though I think her character would still work perfectly fine without that. At the same time, I won’t deny I wouldn’t mind getting some more insights into Keine’s backstory in the future. Nothing major, just something similar to the Ran hints we just got in Unfinished Dream of All Living Ghost.

There is also no strong connection between the hakutaku and recording history, though you can probably make a case that as a mainstay of chronicles and encyclopedias it does have a distinctly historical theme. I personally like this innovation, and especially how it is described in PMiSS.Touhou aside, it’s worth mentioning that a resurgence in the interest in hakutaku occurred in the early months of the covid pandemic. This is an example of a broader surge in interest in various apotropaic disease-repelling mythical and folkloric figures in response to the rise of the novel coronavirus (as you might remember, the amabie fad in particular even managed to cross language barriers). It probably helped that a statue representing the hakutaku was rediscovered in the Tennō-ji in Osaka recently.

The Tennō-ji hakutaku (Asahi Shimbun; source contains more photos and a video. Reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Some of the articles covering the brief hakutaku resurgence seemingly confuse it with the kutabe (kudan), but these are actually two separate creatures. The source of confusion is probably Shigeru Mizuki, who did depict kutabe as notably hakutaku-like, since he believed the it was a local adaptation of the standard hakutaku narrative.

Shigeru Mizuki’s kutabe (reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Mizuki’s portrayal in turn influenced figures of kutabe made by local craftsmen from Takaoka in 2020. The English edition of Asahi Shimbun covered this in some more detail here, though ultimately it is beyond the scope of this article. As far as I know the connection, while plausible, does not permit full conflation, and in particular kutabe never attained the sort of religious significance hakutaku once had.

Bibliography

Bernard Faure, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Donald Harper, 'Hakutaku hi kai zu' 白澤避怪図 (White Marsh Diagram to Repel Ominous Prodigies)

Donald Harper, Pictures of Baize / Hakutaku 白澤 (White Marsh): Ephemera and Popular Culture in Tang China and Edo Japan (not accessible online but there is a digital lecture version on youtube)

Jao Tsung-i, Postface to the Two Dunhuang Manuscript Fragments of the Baize jingguai tu 白澤精怪圖 (White Marsh’s Diagrams of Spectral Prodigies; P.2682, S.6261)

Richard E. Strassberg, A Chinese Bestiary: Strange Creatures from the Guideways Through Mountains and Seas

Kathryn Tanaka, Amabie as a Play in Kansai

Constantine N. Vaporis, Caveat Viator. Advice to Travelers in the Edo Period

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Resource List

List of freely-available online sources only, some of which are translated into English. Will be updated sporadically.

Last update: Nov 26, 2022.

GENERAL (English)

A Chinese Bestiary by Richard E. Strassberg

A nice if incomplete translation of the Classics of Mountains and Seas (Shanhaijing) that focuses on the creatures. It goes into considerable detail and background, unlike Anne Birell’s direct translation. It does not, however, translate the numerous sections listing mountains with no creatures.

The Nine Songs translation by Arthur Waley (Available on the Internet Archive)

A translation of the Nine Songs from the Songs of Chu.

Six Chinese Classics translation by A. Charles Muller

Consists of Analects of Confucius, Great Learning, Doctrine of the Mean, Mencius, Daode jing and Zhuangzi (Chapters One and Two)

Book of Poetry translation by James Legge

300 Tang Poems (Available online) (Alternate link)

“Sui-Tang Chang'an” by Xiong Cunrui

An unbelievable resource for anyone seeking information on the Chang’an city during the Sui and Tang dynasties. It has maps and fully listed names of all the wards and Imperial City interior buildings, and even a compiled list of known inhabitants of the city as well as which wards they were reportedly living in.

Brill Chinese Reference Library: Title of Officials translation by Michael Loewe

Translation of titles from the Hanshu, I believe.

The T'ang Code, Volume I: General Principles translated by Wallace Johnson

The T’ang Code, volume 2, Specific Articles translated by Wallace Johnson

Tang dynasty law code. Can probably also double as “tag yourself” meme if you want.

“Epidemic and population patterns in the Chinese Empire (243 B.C.E. to 1911 C.E.)” by A. Morabia

The Ideology of the Guqin

USEFUL SITES

cbaigui.com

A wonderful site compiling bestiary entries from many ancient Chinese texts, including but not limited to Diagrams of Bai Ze, Old Book of Tang, Book of Rites, etc. You can search them sorted by book or by dynasties, which is a feature I never knew I needed until I saw it.

ctext.org

We know it, we love it, the MVP that compiles so many of ancient texts, and some of them have translations (by James Legge) too.

In Conversation with China Youtube Channel

Collection of online talks/lectures on various topics, including Classic Chinese grammar, Dunhuang Cave Manuscripts, etc. Personal biases, but some of my favorites are the ones by Sarah Allan, Donald Harper, and the series that explores the definition, perception, and treatment towards those with disabilities in early China.

Wikisource 古文 Category

I really just stumbled upon this looking for 白泽精怪图 but it has a number of misc texts in Traditional Chinese.

chinaknowledge.de

Another classic. It’s an incredible site for anyone looking to jump into a specific topic; you can pick up from there.

100jia.net

It’s kind of a headache to navigate it at the start but the link provided should send you to a page with a long list of ancient Chinese classic texts as well as several existing online translations of them. It’s in German, yes, don’t mind it.

Resources on Chinese Legal Tradition

TANG DYNASTY SPECIFIC

"The Reconstruction of Yongning Ward" by Heng Chye Kiang and Chen Shuanglin

Details a theoretical and digital reconstruction of a particular ward of Chang’an during Tang dynasty, including population estimate.

The administrative divisions of the Tang dynasty

唐朝官员品级 Tang dynasty official positions ordered by rank

中国俸禄制度史 The history of China's salary system

CREATURES, FOLK RELIGION, ETC

"The Textual Form of Knowledge: Occult Miscellanies in Ancient and Medieval Chinese Manuscripts, 4th Century BCE to 10th Century CE" by Donald Harper

I’m not even gonna try to describe it right now you can figure it out by reading the title

Ho Peng Yoke books on Archive.org

Includes "Chinese Mathematical Astrology: Reaching out for the stars" and "Explorations in Daoism Medicine and Alchemy in Literature".

龙是如何进化的:龙纹史考 by 陈涤

A post that chronicles the development and changes to the form of the dragon across dynasties.

龙头鹿身的就是麒麟?都弄错了!麒麟的秘密大公开! by 天可汗文化

A post that chronicles the development and changes to the form of the qilin across dynasties.

“Bai Ze special” by 哀吾生之須臾

白泽特辑【一】「白泽」的传说

白泽特辑【二】「白泽」的形貌

白泽特辑【三】「白泽图」的相关概况

Bai Ze, Ephemera and Popular Culture by Donald Harper (paper available on the Methods on Sinology site, but site is under construction)

白泽志怪 by 白泽君

One man’s attempt to piece together Diagrams of Bai Ze and explore Bai Ze as a myth. This particular post attempts to put together the surviving entries of the lost text.

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

the Ruinous Quartet is based off the Four Perils in Chinese mythology: Taotie (Ting Lu), Qiongqi (Chien Pao), Taowu (Wo Chien), and Hundun (Chi Yu)

The Four Perils are like foils to the Four Auspicious Beasts (which the genie therian forms are based off of)

from the Zuo Zhuan, Shanhaijing, and Shenyijing:

the Hundun (渾敦, 渾沌; 'chaotic torrent') is a yellow winged creature of chaos with six legs and no face and sudden, destructive rage

the Qiongqi (窮奇; 'distressingly strange, thoroughly odd') is a monstrous creature that kills for pleasure and eats people

the Taowu (檮杌; 'block stump') a reckless, lazy, and stubborn creature

and the Taotie (饕餮; 'greedy glutton') is a gluttonous beast.

interestingly enough, Chien Pao’s design is also reminiscent of the weasel yokai Kamaitachi, which iirc was synonymous with Qiongqi in Japanese folklore

Chi Yu’s design also looks like a celestial eye, a goldfish known for big bulbous eyes, which isn’t exactly relevant to the mythology/folklore discussion but i looked up some pictures while doing some research and now i love Chi Yu even more

Wo Chien has 92 tablets. i found this out using Bulbapedia because i’m not nearly insane enough to try to count the tablets in game

the pot on Ting Lu’s head that makes it look funny is called a ding (鼎), an ancient Chinese cauldron that served as a symbol of imperial authority

i’m not totally sure what their names mean Wade-Giles formatting is used for romanization why isn’t it pinyin but according to Bulbapedia:

Wo-Chien may be a combination of 蝸 / 蜗 wō(Chinese for snail) and 簡 / 简 jiǎn (Chinese for bamboo slips)

Chien-Pao may be a combination of 劍 / 剑 jiàn (Chinese for sword) and 豹 bào (Chinese for leopard)

Ting-Lu may be a combination of 鼎 dǐng(ancient Chinese cauldron) and 鹿 lù (deer)

Chi-Yu may be a combination of 鯽魚 / 鲫魚 jìyú(Chinese for goldfish) and 玉 yù (Chinese for jade)

anyways, there’s some fun trivia on the Ruinous Quartet! i love these four funky little harbingers of disaster

thank you so much for going into all of this detail I appreciate it immeasurably 💖

This is all so cool??? I have always loved when games will put little nods to mythology or draw inspiration from real world myths -- especially when it means I get to learn something new!! I knew about the Four Auspicious Beasts and the link between them and the Therian forms of the Unova Trio (plus the new Hisuian one in Arceus), but I never knew they had counterparts! And all the trivia is amazing too thank you so much for digging it up I have learned so many things tonight I feel enriched

#answered#anonymous#pokemon scarvi#scarvi spoilers#of a sort#this is all so cool#i've been vibrating since it came in#and i keep reading it over and over it's just /so awesome/#thank you so much for sharing it i love all of this

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nian

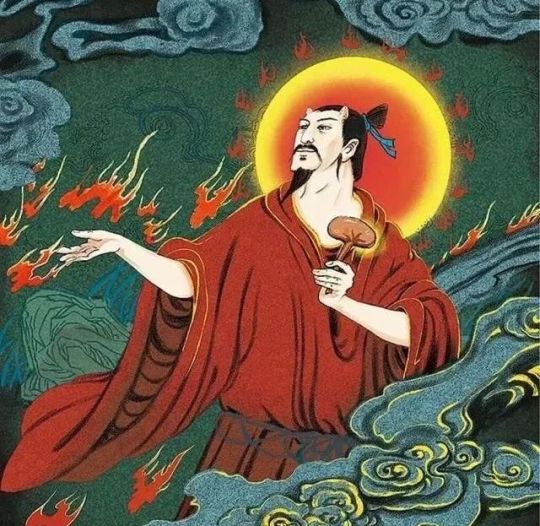

A nian is a beast in Chinese mythology. Nian live under the sea or in the mountains. The Chinese character nian more usually means "year" or "new year". The earliest written sources that refer to the nian as a creature date to the early 20th century. As a result, it is unclear whether the nian creature is an authentic part of traditional folk mythology, or a part of a local oral tradition that was recorded in the early 20th century. Nian is one of the key characters in the Chinese New Year. Scholars cite it as the reason behind several practices during the celebration, such as wearing red clothing and creating noise from drums and fireworks.

Once every year at the beginning of Chinese New Year, the nian would come out of its hiding place to feed, mostly on people and animals. During the winter, when food was scarce, it would raid villages, eating the crops and sometimes the villagers themselves - particularly their children. Several accounts describe its appearance, with some claiming that it resembles a flat-faced lion with the body of a dog and prominent incisors. Other authors described it as larger than an elephant with two long horns and many sharp teeth. The weaknesses of the nian are purported to be a sensitivity to loud noises, fire, and a fear of the color red.

Some local legends attribute the Chinese lion dance to the nian. The tradition has its origins in a story of a nian's attack on a village. After the attack, the villagers discussed how to make the nian leave them in peace. Since it was discovered that the beast was afraid of the color red, people put red lanterns and spring scrolls on their windows and doors. They would also leave food at their doorstep in a bid to divert it from eating humans. Other sources say that an old man who came to visit actually informed the villagers of the nian's weaknesses.

The traditions of firecrackers, red lanterns, and red robes found in many lion dance portrayals originate from the villagers' practice of hitting drums, plates, and empty bowls, wearing red robes, and throwing firecrackers, causing loud banging sounds to intimidate the nian. According to this same myth, it was captured by Hongjun Laozu, an ancient Taoist monk, and became his mount.

Various aspects of cultural practices relating to Chinese New Year are part of the nian legend. These cultural practices are recorded in ancient texts, though none of them refer to a creature called nian.

The Erya records that the character nian (年) was first used to mean "year" during the Zhou dynasty, replacing terms used in previous eras. The Shuowen Jiezi records that the character nian meant "ripeness of grains" and was composed of the character "he" (禾, rice plant) and "qian" (千, indicating the sound) and quotes the Chunqiu, which uses it in the sense of a great harvest.

The attributes of the nian creature in the modern legend, of fear of noise and fire, correlate with ancient legends relating to the use of firecrackers to drive off ape-like creatures in the mountains called shanxiao, first recorded in the Shanhaijing.

The practice of sweeping and cleaning at the start of the year is recorded in Zhou dynasty sources as intended to ward off plague spirits, and the practice of using music and drama to receive gods and ward off plague spirits is recorded from the same era. The creature's role in the celebration of the Chinese New Year is highlighted by the way the Chinese call this holiday Guo Nian, which means "pass over nian" or "overcome nian."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xiang Yao from Chinese mythology.

Xiangliu (Xiangyao) was a minister of the snake-like water deity Gonggong. Xiangliu devastated the ecology everywhere he went. He was so gluttonous that all nine heads would feed at the same meal. Everywhere he rested or breathed upon (or that his tongue touched, depending on the telling) became boggy with poisonously bitter water, devoid of human and animal life. When Gonggong received orders to punish people with floods, Xiangliu was proud to contribute to their troubles. Eventually, Xiangliu was killed, in some versions of the story by Yu the Great, whose other labors included ending the Great Flood of China, in others by Nüwa after he was defeated by Zhurong. The Shanhaijing says his blood stank to the point it was impossible to grow grain in the land it soaked and the area flooded, making it uninhabitable. Eventually Yu had to restrain the waters in a pond, over which the Sky Lords built their pavilions.

Follow @mecthology for more myths and lores.

DM for pic credit or removal.

Source: Wikipedia.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blue Archive: Dragon & Tortoise

A somewhat long overdue focus event on the Shanhaijing academy in BA, one of the factions/regions not really given any true time in the game so far outside of some early and short events. Hell, prior to this event, Shanhaijing had just five playable units and two of them were alts. The accompanying banner added two more (including the incredible dork above) and introduced some others for future use.

The story is simple and sweet, clearly serving practically as a re-introduction to Shanhaijing and its internal factions of Black Tortoise Promenade and Genryumon (the student council); it's very welcome, as the former in particular was last depicted as corrupt merchants not entirely distinct from the Kaiser Corp antagonists from the main story & Abydos events (that has now been said to be just one). We even get a stinger for the third of the Seven Prisoners, making that two events in a row to finally start making use of that whole early event plot beat.

The new characters are all great, Rumi's and Kisaki's little moments of wistful regret about the mantle of leadership and its responsibilities are nice, Saya getting some actual plot time was fun (all of her Relationship Story cutscenes were delightful before now, it's fun to see them pay off), Reijo's a good meathead and Mina is basically Shanhaijing's Aru, 1:1, only where Aru is constantly panicking about looking cool, Mina is, well, self-confident. She's the highlight by quite a bit, and I am fucking dying to see her and Aru in an event story sometime. It's just too obvious and good a set-up (Aru's even got a token drop buff for this event!) to let go to waste.

Shanhaijing could do with more focus at some point; I'd hope it'd get a main story volume as well (Hyakkiyako just got one, Volume 5, in Japan shortly ago), but even more events to flesh it out more would be nice. Even before its main story volume, Hyakkiyako had quite a few events between the Ninja Club and Momoyodou crew stories which also introduced a bevy of other clubs and elements of its academy; Shanhaijing needs some more of that, perhaps another Eastern Alchemy Society member or another club as well. They'll definitely come back around, the Shintai Kai stinger here ensures it, at least. As is, this is a real good first step to getting it in gear for more.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

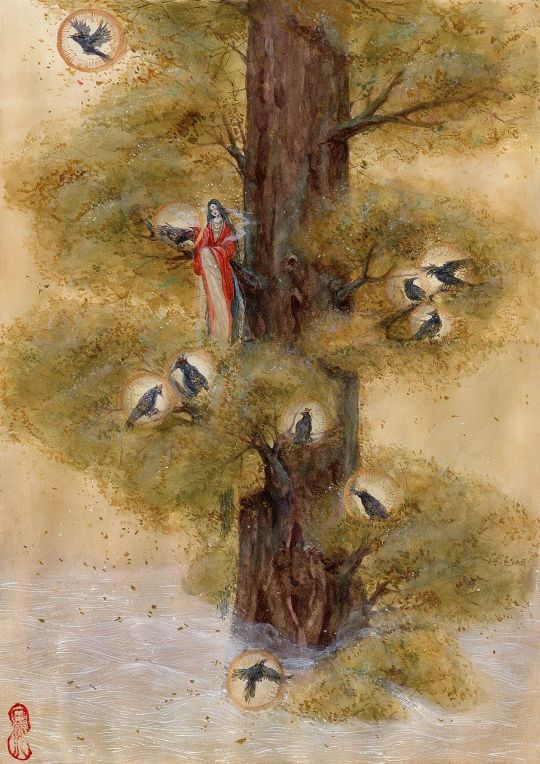

The Mysterious Sanxingdui(part2)

Another important belief of the ancient Shu people was sun worship.

古蜀人的另外一项重要信仰,是太阳崇拜。

Since ancient times, the ancestors believed that in the easternmost, central and westernmost parts of the sky, there were three sacred trees connecting heaven and earth, named Fusang, Jianmu and Ruomu.

从上古时代起,先民们就相信,在天的最东边、最中央和最西边,分别有三棵连通天地的神树,名为扶桑、建木和若木。

In the easternmost Fusang divine tree, there are ten more golden crows inhabiting the tree, which are ten suns.

在最东边的扶桑神树上,又栖息着十只金乌,这十只金乌,就是十个太阳。

Every day at dawn, one of the golden crows will rise from Fusang in a six-dragon chariot and sail to Jianmu, whereupon the sun rises in the east.

每天黎明时分,其中一只金乌会乘六龙车从扶桑起驾,驶往建木,于是太阳东升;

By the time the Golden Crow reached Jianmu, it was midday

当金乌到达建木时,就到了正午时分;

Then the golden crow sailed again from Jianmu to Ruomu, the sun set in the west, and the day thus turned into night.

随后,金乌又从建木驶往若木,太阳西落,白昼由此转入黑夜。

The sacred tree and the golden crow, together control the change of day and night, which for the first people who had to rely on the sun for their labors, meant life itself.

神树与金乌,共同掌控着昼夜更替,这对于必须依靠太阳进行劳作的先民来说,就意味着生命本身。

On the other hand, legend has it that in the location of the Fusang tree, a huge tribe was derived, named Dongyi, with the divine bird as a totem for generations, worshipping the sun god. The leader of the Dongyi tribe, Shao Hao, was also the ancestor of the ancient king of Shu, Cancong.

另一方面,传说在扶桑神树的所在地,衍生了一个庞大的部落,名为东夷,世代以神鸟为图腾,崇拜太阳神。而东夷部落的首领少昊,也正是古蜀王蚕丛的祖先。

So we can understand why such exquisite and huge bronze sacred trees, as well as a large number of sun-shaped artifacts, were unearthed from the site of Sanxingdui.

所以我们就能够理解,为什么从三星堆遗址中会出土如此精美、庞大的青铜神树,以及大量的太阳形器物了。

There are a total of eight bronze sacred trees, of which the most completely restored one is 4 meters high and is the world's largest known single bronze relic, named the "No. 1 sacred tree".

青铜神树一共有八棵,其中修复最完整的一棵高达4米,是目前全世界已知最大的单件青铜文物,被命名为“一号神树”。

On this bronze sacred tree, there are nine downward curving branches, and on each of them stands a divine bird with its head and wings spread, a metaphor for one of the ten golden crows flying from Fusang to Jianmu after the sun rises in the east.

在这棵青铜神树上,有九条向下弯曲的枝干,每条枝干上都伫立着一只昂首展翅的神鸟,喻示着十只金乌中的其中一只从扶桑飞往建木以后,太阳东升。

This is exactly the scene of "nine days in the lower branch and one day in the upper branch" as stated in the Shanhaijing.

这正是《山海经》所言“九日居下枝,一日居上枝”的场景。

There is another artifact that more directly reflects the sun worship of the ancient Shu ancestors, and it was just as stunning to everyone when it was unearthed: the gold leaf of the Sun God bird unearthed at the Jinsha site.

还有一件能更直接反映古蜀先民崇拜太阳的文物,它出土的时候,也同样惊艳了所有人,那就是出土于金沙遗址的太阳神鸟金箔。

We'll talk more about this next time

to be continued....

#ancient china#ancient culture#archaeology#anyang#sanxingdui#sacrificial pits#shu kingdom#relics#bronze#sculpture#sculpting#sculpedia#history#china#natural history#山海经#三星堆

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sul retro c'era una mappa pieghevole. Quando cercai di aprirla andò in briciole

"All'improvviso ricordo un'antica copia del Libro dei monti e dei mari che ho sfogiato in un negozio di libri usati di Guangzhou. Sul retro c'era una mappa pieghevole. Quando cercai di aprirla andò in briciole".

#letteratura#letteraturacinese#chineseliterature#china#cina#guangzhou#beijing#pechino#pechinoèincoma#beijingcoma#coma#tienanmen#majian#shanhaijing#librodeimontiedeimari#dinastiahan#dinastiahanoccidentale

0 notes

Note

"I-I've always wanted to...g-get stepped on my Boss." Haruka admits.

"S-Sorry, I shouldn't have said that!"

"It's only natural to want a great woman to establish her dominance." She thinks? That impressive (if barely clothed) woman from Shanhaijing often steps on people so maybe this is the same?

"If it'll ensure that you stay in line, happy and disciplined, then I'll step on you as much as you like, Haruka."

"We'll do that back at the office. I don't want to dirty your clothes with my heels."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zhenniao

Zhenniao

Description

Zhenniao (Chinese: 鴆鳥; pinyin: zhènniǎo) or sometimes translated as Zhen or Poison feather Birds is a name given to poisonous birds that are said to have existed in what is now Southern China during ancient times and is referenced in many Chinese myths, annals, and poetry. The Shanhaijing Chapter 5: Classic of the Mountains: Central describes the Zhen as resembling an eagle living in Girl's Tabletop Mountain, Lutemute Mountain, and Jade Mountain in Southern China.

In Guo Pu's (郭璞) commentaries of the Shanhaijing, he describes this bird as having a purple abdomen and green-tipped feathers with a long neck and a scarlet beak. This bird acquires its poisonous attributes from devouring poisonous viper heads. The male in the species is called Revolving Sun (Chinese: 迴陽; pinyin: huíyáng) and the female is called Yin Harmony (Chinese: 陰氳; pinyin: yīnyūn). Another description of the zhen however appears in the Song Dynasty dictionary Piya (Chinese: 埤雅; pinyin: Píyǎ), describing it as being goose like, colored dark-purple, and having a beak 7‑8 cun long and copper-colored.

As described in the Piya, from its very veins to the tips of its feathers, the zhen's body is said to be tainted with an unparalleled poison referred to as zhendu (Chinese: 鴆毒; pinyin: zhèndú) or zhen poison. The zhen's feathers were often dipped into liquor to create a poisonous draught that was often used to carry out assassinations. Its meat however was said to be overtly toxic and gave off a gamy odor that rendered it inadequate for surreptitious use and the zhen's excrement could dissolve stone. The zhen's poison was said to be so deadly that it needed only to pass through one's throat to kill a person. In the Baopuzi (Chinese: 抱樸子; pinyin: Bàopúzǐ) by Taoist adept Ge Hong, the only thing that was said to be able to neutralize the zhen's poison was the horn of Xiniu (犀牛) or the rhinoceros. Xiniu horns would be made into hairpins and when used to stir poisonous concoctions would foam and neutralize the poison.

Aside from the Shanhaijing, Piya, and Baopuzi, an entry for the zhen also appears in the Sancai Tuhui along with a woodblock print. In the historical records of ancient China, references to the zhen are usually in the form of the idiom "Drinking zhen to quench one's thirst" (Chinese: 飲鴆止渴; pinyin: yǐnzhènzhǐkě) or when comparing the zhendu to the poison from monkshood. Such references include "The Biography of Qi Huan Gong" from the Spring and Autumn Annals and "The Biography of Huo Xu" from the Book of the Later Han. The idiom is usually used to describe someone who merely considers the benefit for the time being and not contemplating the gravity of the consequence that his action will bring him. The following excerpt is from "The Biography of Qi Huan Gong":

"The nations of Rong (Chinese: 戎; pinyin: Róng)and Di (Chinese: 氐; pinyin: Dī) are as jackals and wolves, and they are never contented. All states of Huaxia are intimate, and every one should not be deserted. It is like drinking the bird Zhen's poison to seek momentary ease with no thought of the future, and this mind should not be kept."

In Chinese accounts, there are a number of mentions about zhendu poisoning used in failed and successful assassinations, but because "zhen" eventually became a metaphor for any type of poisoning in general, it is not always clear if the bird-poison was actually employed in each case. Various hagiographic sources allege that Wang Chuyi, a disciple of Wang Chongyang, was said to have been immune to poison and to have survived after drinking liquor containing poison from the zhen bird.

In the Japanese historical epic Taiheiki, Ashikaga Takauji and his brother Ashikaga Tadayoshi force Prince Morinaga to take zhendu (or chin doku as it's known in Japan). Tadayoshi later was himself captured and poisoned with zhendu.

Existence

Wild zhenniao were supposedly last seen in the Song dynasty when many farming Han Chinese moved to Guangdong and Guangxi. Humans are supposed to have killed them all. Chinese ornithologists have often theorized that the zhen was similar to the secretary bird or the crested serpent eagle (which happens to live in Southern China) and gained their toxicity from ingesting poisonous snakes, similar to how the poison dart frogs produce poison by ingesting poisonous insects. As a consequence, in some illustrated books, pictures very similar to these two birds have been used to depict the zhen.

However, throughout most modern history, zoologists knew of no poisonous birds and presumed the zhen to be a fabulous invention of the mind. But in 1992, an article was published in Science reporting that the hooded pitohui of New Guinea has poisonous feathers and since then a few other species of similarly poisonous birds have been discovered, most of which also gain their poison from their prey. A recent article in China has been published bringing up the question if the zhen bird could have really existed.

PS: Btw it really sucks that tumblr doesn’t let people upload gifs with less than 10mb, makes us optimize our gifs and even then it optimizes them even further in theyr servers to 3mb i believe

#Japanese#China#Mythology#song dynasty#toxicity#guangdong#history#poisonous#bird#ancient#chinese#myths#creature#legendary#legends#folklore#lore#artist#surrealism#macabre#psychadelic#creativity#avian#photomanipulation#fantasy#symbol#astrology#mythycal#.#experimentalart

5 notes

·

View notes