#Soviet Central Asia

Text

My Love for Central Asian Literature Part 1 – Abdurauf Fitrat, Abdulla Qodiry, and Cho’lpon

I’m currently working on a script for my history podcast, the Art of Asymmetrical Warfare, about three Central Asian literary giants: Abdurauf Fitrat, Abdulla Qodiry, and Abdulhamid Sulayman o’g’li Yusunov also known as Cho’lpon and it got me thinking about their influence on my historical interests, reading tastes, and writing style.

If you’re wondering why a podcast about asymmetrical warfare is talking about three Central Asian writers, you should check out my upcoming podcast episode. 😉

How I Became Interested in Central Asian Literature

My interest in Central Asia has been a long time percolating and it was just waiting for the right combination of sparks to turn it into a hyperfixation (sort of like my interest in the IRA). I went to the Virginia Military Institute for undergrad and majored in International Relations with a minor in National Security and my focus was on terrorism. So, I knew a lot about Afghanistan and Pakistan and the “classic” “terrorists” like the IRA, the FLN, Hamas, etc. and I knew of the five Central Asian states (one of my professors was banned for life from either Turkmenistan or Tajikistan and sort of life goals, but also please don’t ban me haha), but my brain bookmarked it, and I went on my merry way.

Then I went to University of Chicago for my masters, and I took my favorite class: Crime, the State, and Terrorism which focused on moments when crime, government, and terrorism intersect. This brought me back to Pakistan and Afghanistan, but this time focusing on the drug trade which led me to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan and their ties to the Taliban and it was sort of like an awakening. I suddenly had five post-Soviet states (if you know me, you’ll know I’m fascinated by post-Soviet states) with connections to the drug trade (another interest of mine) and influenced by Persian and Turkic identities. I was also writing a scifi series at the time that included a team of Russian, Eastern European, and Central Asian scientists and officers, so the interest came at the right time to hook my brain. Actually, if you buy my friend’s EzraArndtWrites upcoming “My Say in the Matter” anthology, you’ll read a short story featuring Ruslan, my bisexual, Sunni Muslim, Uzbek doctor who was inspired by my sudden interest in Central Asia.

Hamid Ismailov’s the Devils’ Dance

I wanted to know more beyond the drug trade and usually when I try to learn about a place whether it be Poland, Ireland, or Uzbekistan, I go to their music and literature. This led me to one of my all-time favorite writers Hamid Ismailov and my favorite publishers Tilted Axis Press.

Tilted Axis Press is a British publisher who specializes in publishing works by mainly Asian, although not only Asian writers, translated into English. They publish about six books a year and you can purchase their yearly bundle which guarantees you’ll get all six books plus whatever else they publish throughout the year. I’ve purchased the bundle two years in a row, and I haven’t regretted it. The literature and writers you’re introduced to are amazing and you probably won’t normally have found unless you were looking specifically for these types of books.

Hamid Ismailov is an Uzbek writer who was banished from Uzbekistan for “overly democratic tendencies”. He wrote for BBC for years and published several books in Russian and Uzbek. A good number of his books have been translated into English and can be found either through Tilted Axis or any other bookstore/bookseller. Some of my favorites include Dead Lake, the Manaschi, the Underground, and the book that inspired everything the Devils’ Dance.

Tilted Axis’ translation of The Devils’ Dance came out the same year I was working on my masters, and I bought it because it is a fictional account of Abdulla Qodiriy’s last days while in a Soviet prison. He goes through several interrogations and runs into his fellow writers and friends: Fitrat and Cho’lpon. Qodiriy is written as detached from events while Cho’lpon comes across as very sarcastic, as if this is all a game, and Fitrat is interestingly resigned to the Soviet’s games but seems to have some fight in him. Qodiry distracts himself from the horrors around him by thinking about his unwritten novel (which he really was working on when he was arrested by the NVKD). His novel focuses on Oyxon, a young woman forced to marry three khans during the Great Game. His daydreaming takes a power of its own and he occasionally slips back to talk with historical figures such as Charles Stoddart and Arthur Connolly-two British officers who were murdered by the Khan of Bukhara (not a 100% convinced they didn’t have it coming).

We spend half of the narrative with Qodiriy and the other half with Oyxon as she is taken from her home and thrown into the royal court of Kokand’s khans where she is raped and mistreated and has to survive the uncertain times of Central Asia during the Great Game. She is passed from Umar, the father, to Madali, the son, to the conquering Khan of Bukhara, Nasrullah who eventually murders her and her children. From a historical perspective, I have a lot of questions about Nasrullah because a lot of sources write him off as a cruel tyrant and nothing more which usually means there’s more…Before Oyxon and Qodiriy are taken to their deaths, there is a poignant scene where the two timelines merge into one that will stay with you long after the novel is over.

The book is a masterpiece exploring themes of colonialism, liberty, powerlessness in face of overwhelming might, the power of the human mind and spirit, the endurance of ideas, even when burned and “lost”, as well as being a powerful historical fiction about two disruptive periods in Central Asian history. It’s also a love letter to the three literary giants of Uzbek fiction: Abdurauf Fitrat: a statesmen who crafted the Turkic identity of Uzbekistan, a playwright and statesmen, Abdulla Qodiriy who created the first Uzbek novel (O’tgan Kunar which was recently translated by Mark Reese and can be bought in most bookstores), and Cho’lpon who created modern Uzbek poetry (you can buy his only novel Night translated by Christopher Fort and a collection of his poems 12 Ghazals by Alisher Navoiy and 14 Poems by Abdulhamid Cho’lpon translated by Andrew Staniland, Aidakhon Bumatova, and Avazkhon Khaydarov in any bookstore).

City of Kokand circa 1840-1888, thanks to Wikicommons

All three men were Jadids (modern Muslim reformers) who worked with the Bolsheviks to stabilize Central Asia, helped create the borders of the five modern Central Asian states, and were murdered by the Soviets during Stalin’s Great Purge of the 1930s. It was illegal to publish their work until the glasnost. Check out my history podcast to learn more about the Jadids and the Russian and Central Asian Civil Wars.

From a literary perspective however, Ismailov wrote the Devils’ Dance similarly to Qodiriy’s own O’tgan Kunlar and Cho’lpon’s Night (whereas Ismailov’s other books: Dead Lake and the Underground are more Soviet era Central Asian literature and his newest book the Manaschi is more post-Soviet). Like Qodiriy and Cho’lpon, Ismailov writes about MCs who are not the master of his own fate, but instead are going through the motions of a fate already written, one of his MCs is a woman unfairly caught in a misogynistic system that uses women as it sees fit (although I would argue that Hamid gives his women characters more agency than either Qodiry and Cho’lpon), and he writes about the corruption and inefficiencies of whatever government agency is in control at the time – whether it be a Russian, a Khan, or an indigenous agent of said government. All three books end in death, although only Cho’lpon’s Night and Ismailov’s the Devils’ Dance end in a farce of a trial. Even stylistically Ismailov mimics the rich and dense language of Qodiriy whereas I find Cho’lpon’s style crisper although no less rich for it.

Abdurauf Fitrat’s Downfall of Shaytan

While Ismailov led me down a historical rabbit hole which is captured on my history podcast, I also wanted to see if any of Fitrat’s, Qodiry’s, or Cho’lpon’s work had been translated into English.

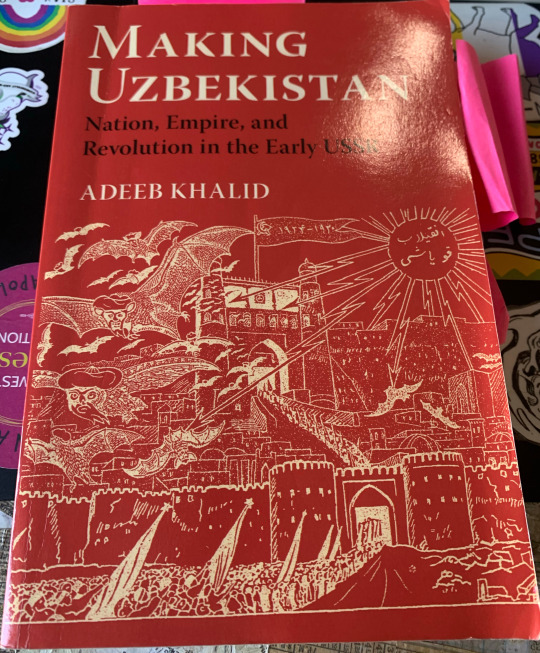

So far, I can’t find anything by Fitrat except excerpts in the Devils’ Dance and Making Uzbekistan by Adeeb Khalid (one of my all-time favorite history books by one of my favorite scholars who also happens to be very kind and patience and I still can’t believe I interviewed him for my podcast).

Fitrat wrote a specific play I really want to read called Shaytonning Tangriga Isyoni which Dr. Khalid translated as Shaytan’s Revolt Against God. According to the summary provided by Dr. Khalid it is a challenging take on the Islamic version of Satan’s downfall.

According to Dr. Khalid, in Islamic cosmology God created angels from light and jinns from fire and they could only worship God. When God made Adam, He commanded all angels and jinn to bow before him. Azazel (who would become Shaytan) refused claiming he was better than Adam who was made out of clay. He was cast out of heaven and became Shaytan/Iblis.

Fitrat reimagines Shaytan’s defiance as heroic. He is disgusted by the angels’ submissive nature and God’s ability to create anything and yet he chooses to create servants. Azazel has seen God’s plan to create another being out of clay and have the angels worship him as well, which Azazel sees as a betrayal on God’s part. Gabriel, Michael, and Azrael try to convince Azazel to see reason and instead he brings his grievance to the other angels who are confused. God intervenes and the angels give in, but Azazel continues to defy God. God strips him of his angelic nature, and he turns into Shaytan who warns Adam of God’s treacherous nature and vows to free him and all other creatures from God’s trickery.

Doesn’t it sound amazing?! Fitrat has outdone Milton in terms of completely overturning God’s and Satan/Shaytan’s rules (also no wonder he was marked for execution right? Complete firebrand and pain in the ass (and I mean that with love)) and I really want to read it. So, either someone needs to translate this into English, or I need to learn Persian/Uzbek, which ever happens first, haha (judging on how my Russian is going…)

Abdulla Qodiry’s O’tgan Kunlar

While I can’t find any of Fitrat’s work in English, there have been two translations of Abdulla Qodiriy’s novel and the first ever Uzbek novel O’tgan Kunlar. In English, the title translates as Days Gone By or Bygone Days. There are two translates out there: Days Gone By translated by Carol Ermakova, which is the version I’ve read, and Otgun Kunlar by Mark Reese, which I haven’t read yet but I’ve heard him speak (and actually spoke to him about his translation – thank you Oxus Society) so you can’t go wrong with either one.

O’tgan Kunlar is an epic novel set in the Kokand Khanate in the 18th century and is about Otabek and his love Kumush. There’s also a corrupt official, Hamid who hates Otabek because Otabek is a former who wants to change the society Hamid benefits from. Hamid tries to get Otabek killed for treason because of his reformist believes, but the overthrow of the corrupt leader of Tashkent (who Otabek worked for) saves Otabek’s life. However, the corrupt leader’s machinations convince the Khan to declare war against the Kipchaks people, who are massacred. Otabek and his father vehemently disagree with the massacre of the Kipchaks.

Once Otabek is released and gets revenge against Hamid, he marries Kumush without his parent’s approval and is torn between the two families. His mother hates Kumush and forces him to take a second wife, Zainab. Obviously, things go terribly wrong as Otabek doesn’t even like Zainab and Kumush doesn’t know how to feel about her husband having a second wife. Zainab hates her position within the household and eventually poisons Kumush.

Abdulla Qodiriy thanks to Wikicommons

O’tgan Kunlar is considered to be an Uzbek masterpiece that is central to understanding Uzbekistan. Not only is it a great tragic love story, but it also highlights some of the things Qodiriy was thinking about as he engaged with other Jadids. Just as Otabek argued for reforms especially in the educational, social, and familial realms, the Jadids were making the same arguments. We can also see the Jadid’s struggle with the ulama and the merchants in Otabek’s struggle with Hamid. Qodiry attempts to capture the struggle women went through by writing about the horrors for arrange marriages and polygamy, but Kumush is an idealized version of a woman. She is the pure “virgin” like Margarete from Faust while the other two female characters; Otabek’s mother and Zainab are twisted, bitter woman who hurt those they “love”. One could argue they’ve been corrupted by the society they live in, but they also lack the depth of Otabek and even his father.

One of the most interesting parts of the novel is the massacre of the Kipchaks because it is written as the horror it was and both Otabek and his father condemn the action. His father even claims that there is no sense if hating a whole race for aren’t we all human? Central Asia is a vast land full of different peoples who share common, but divergent histories and while these differences have led to massacres, there have also been moments of living peacefully together. It’s interesting that Qodiriy would pick up that thread and make it a major part of his novel because this was written during the Russian Civil Wars and the attempts to create modern states in Central Asia. The Bolsheviks really pushed the indigenous people of Central Asia to create ethnic and racial identities they could then use to better manage the region and so one wonders if Qodiriy is responding to this idea of dividing the region instead of uniting it.

Cho’lpon’s Night

While O’tgan Kunlar is a beautiful book and Qodiriy is a masterful writer, I prefer Cho’lpon’s Night (although don’t tell anyone). Night was supposed to be a duology, but Cho’lpon was murdered before he could finish the second book. Cho’lpon wrote Night in 1934, after years of being attacked as a nationalist. It was a seemingly earnest attempt to get into the Soviet’s good graces. Instead, he would be murdered along with Qodiriy and Fitrat in 1938.

Night is about Zebi, a young woman, who is forced to marry the Russian affiliated colonial official Akbarali mingboshi. The marriage is arranged by Miryoqub, Akbarali’s retainer. Akbarali already has three wives and, like in O’tgan Kunlar, adding a new wife causes lots of problems in the household. Meanwhile Miryoqub falls in love with a Russian prostitute named Maria and they plan to flee together. While they are fleeing they met a Jadid named Sharafuddin Xo’Jaev and Miryoqub becomes a Jadids. Meanwhile Akbarali’s wives conspire against Zebi and attempt to poison her but she unwittingly gives it to Akbarali instead. Zebi is arrested and found guilty of murdering her husband and sentenced to exile in Siberia. The book ends with Zebi’s father, who encouraged her marriage to Akbarali, is driven made by his daughters fate and murders a sufi master while Zebi’s mother goes mad, wandering the streets and singing about her daughter.

Like Qodiriy, Cho’lpon is interested in examining governmental corruption, the need for reform, and women’s plight, but Cho’lpon is less resolute than Qodiriy. Cho’lpon’s novel is constructed similar to poetry: an indirect attempt to capture something that is concrete only for a moment.

His characters are own irresolute or ignorant of important pieces of information meaning they are never truly in full control of their fates. Even Miryoqub’s conversion to Jadidism is to be understood as a step in his self-discovery. In Cho’lpon’s world, no one is ever truly done discovering aspects of themselves and no one will ever have true knowledge to avoid tragedy.

Cho'lpon courtesy of Wikicommons

It is interesting to read Night as Cho’lpon’s own insecurity and anxiety about his own fate and the fate of his fellow countrymen as Stalin seemingly paused persecuting those who displeased him. While Qodiriy crafted and wrote O’tgan Kunlar in the 1920s, which were unstable because of civil war, but promised something greater as the Jadids and Bolsheviks regained control over the region, Cho’lpon wrote Night during the height of Stalin’s Great Terror, most likely knowing he would be arrested and executed soon.

Both novels are beautifully written historical novels about a beautiful region, but I prefer Cho’lpon’s poetic prose and uncertainty.

Conclusion

Reading the works of Fitrat, Qodiriy, and Cho'lpon not only introduced me to a history I knew little about, but also introduced me to a whole literature I never knew existed. The books mentioned in this blog post are beautiful pieces literature and will challenge how you see the world and how much literature we miss out on when we don't read beyond authors who work in our native tongues.

The canon of Central Asian literature is immense, with only a handful of books and poems translated into English. I hope more works are translated so other people can engage with these books and poems and learn about these writers and the circumstances that shaped them. And, if you haven't, go check out Tilted Axis who are doing amazing work translating books so people can engage with them.

If you're enjoying this blog, please join my patreon or donate to my ko-fi

#central asian history#central asian literature#abdurauf fitrat#abdulla qodiriy#cho'lpon#O'tgan Kunlar#Days Gone by#Night#Hamid Ismailov#the Devils' Dance#Soviet Union#Soviet Central Asia#Uzbekistan

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

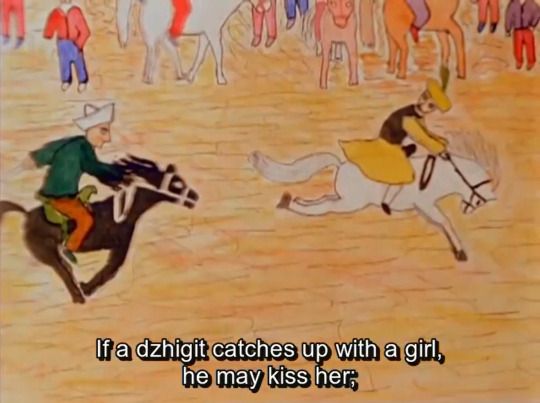

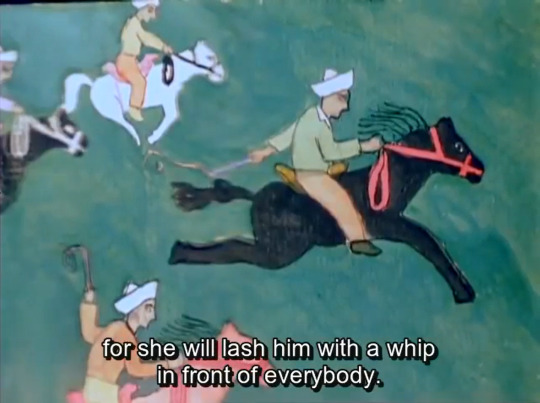

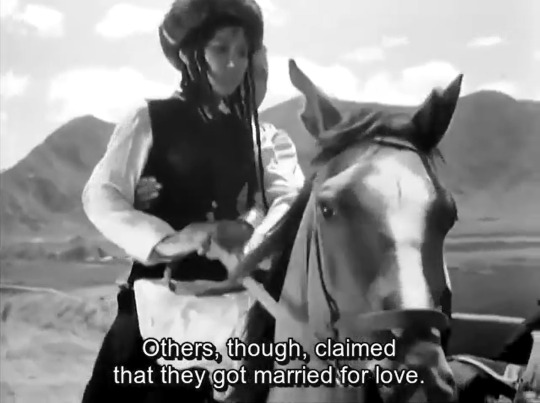

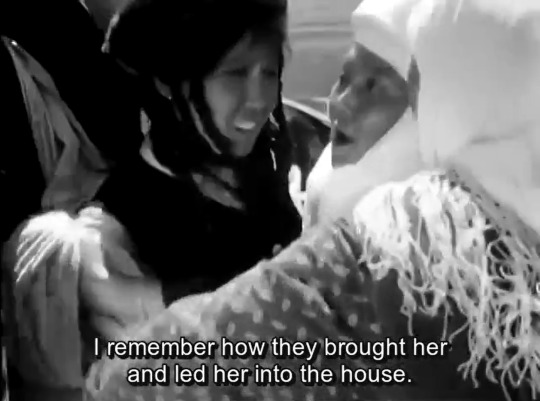

Movie: Jamilya (Джамиля)

Year: 1969

Location: Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republic, Soviet Union

Directors: Irina Poplavskaya and Sergei Yutkevich

The Second World War is raging, and Jamilya's husband is off fighting at the front. Accompanied by Daniyar, a sullen newcomer who was wounded on the battlefield, Jamilya spends her days hauling sacks of grain from the threshing floor to the train station in their village in Kyrgyzstan. Spurning men's advances and wincing at the dispassionate letters she receives from her husband, Jamilya falls helplessly in love with the mysterious Daniyar in this heartbreakingly beautiful tale.

#film#cinema#ussr#Kyrgyzstan#soviet#world cinema#Kyrgyzstani#Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republic#USSR#Soviet Union#Irina Poplavskaya#Sergei Yutkevich#Soviet films#Central Asia

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Photos of Soviet Kazakhstan from the Soviet Ukrainian photo book "Song of Our Native Land" a book dedicated to the 60-year anniversary of the USSR. 1982

"Alma-Ata, the capital city of the Kazakh SSR"

"Truckloads of grain from the virgin lands"

"At Dzhezkazgun Copper Smeltery"

"Medeo Winter Sports Complex"

"Kazakh melodies"

#communism#history#socialism#leftism#marxism#marxism leninism#asia#soviet union#ussr#ussr history#Kazakhstan#central asia

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 2172, 3 June 2024

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Former USSR GDP (PPP) per capita, 2021.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saryozek / Сарыөзек ( Kazakhstan )

#travelphotography#photooftheday#adventure#aroundtheworld#explore#landscape#saryozek#kazakhstantravel#soviet union#kazakhstan#architecture#cityscape#buildings#ussr#travel#trip#streets#ruins#pickoftheday#central asia#soviet town#soviet art#visitkazakhstan#red army#small town#Сарыөзек

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

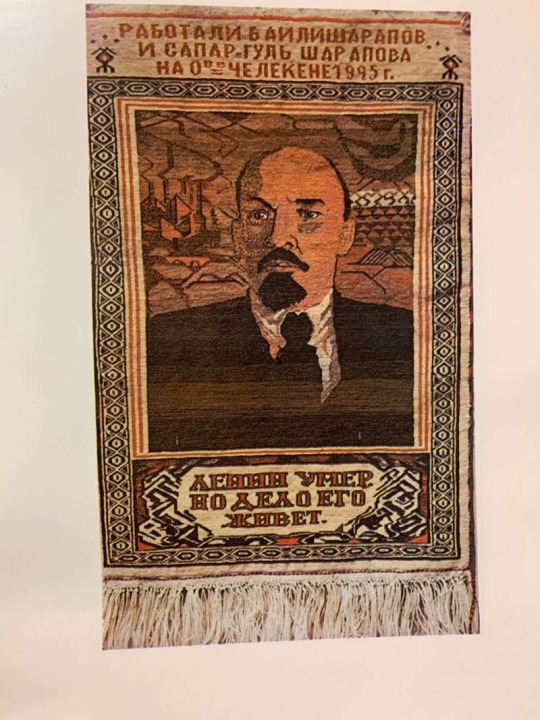

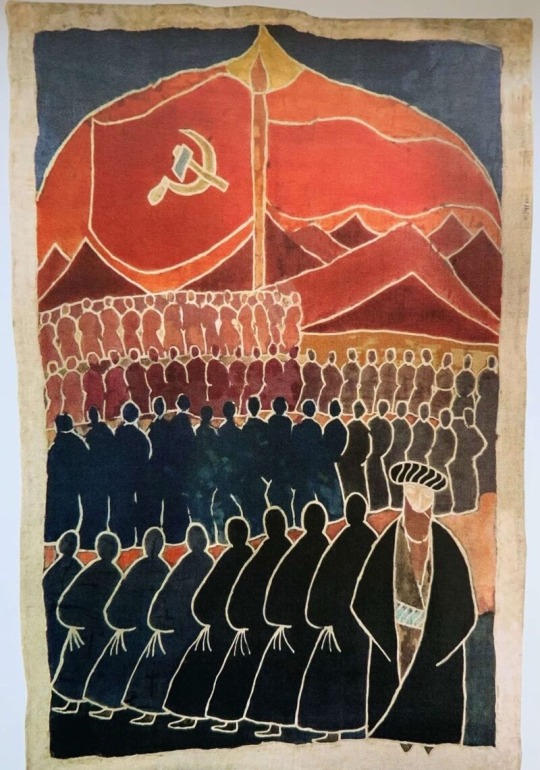

Soviet Central Asian carpet propaganda, from here

#carpet lenin sends me every time#honestly they’re exceedingly beautiful#especially before socialist realism really kicks in#Central Asia#soviet art

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

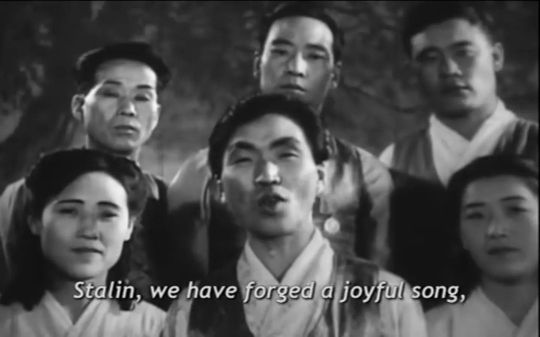

Koryo Saram - Korean Diaspora of the Soviet Union

In the late 1800s thousands of people mostly from Northern Korea went to East Russia to escape famine. Decades later another mass migration from Korea to Russia happened as people fled from Japanese invaders and were attracted by the Bolshevik's promise of free land for peasants. The Korean community thrived in the Soviet Union during the earlier years with many becoming high ranking Communist Party officials, but by 1937 even the family of these high ranking officials would be rounded up and shipped off in cattle trains to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan during Stalin's ethnic deportations. Some people did not survive the harsh conditions of this trip and their corpses would be left unburied at the train stops. Despite all of what they endured in the past, today majority of the Koryo Saram still live in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan where they've kept their traditional Korean customs mixed with the cultures of Central Asians, Russians and other ex-Soviet nationalities.

#Koryo Saram#Korean#Korea#South Korea#North Korea#USSR#Joseph Stalin#Soviet Union#Soviet History#Asia#Central Asia

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Contrast of eras, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

The Soviet style Hotel Uzbekistan and a statute of Amir Timur/Temur, founder of the Timurid Empire which comprised, in part, modern day Uzbekistan

#Tashkent#Uzbekistan#Soviet#hotel#statue#Amir Timur#Amir Temur#Timurid Empire#contrast#architecture#travel#travel photography#Central Asia

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

#infrared#red#aerochrome#digital infrared#kyrgyzstan#bishkek#around the world#moody nature#retro#post soviet#soviet aesthetic#central asia

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Turar Risqulov: A Kazakh Revolutionary Leader

Not only was Turar Risqulov instrumental in salvaging Central Asia after a near decade of civil war, establishing an indigenous government within Soviet Turkestan, and managing the Sovietization of Central Asia, but he was also a key member of the Soviet Union beyond Turkestan and formidable intellectual.

Turar and The Revolutions of Central Asia 1916-1918

Turar Risqulov was born in Semireche to a poor, but highly respect Kazakh family in 1894. His father worked for the Tsarist administration that managed the Semireche oblast. In 1904, his father and older brother had a dispute with one of the Tsarist administrators and murdered him. They were arrested and thrown into prison (Turar’s father would die in prison) and Turar moved in with his uncle in the town of Merke.

Turar would attend a Russo-native school, work for a Russian lawyer in 1910, before attending the agriculture school in Pishpek (not Bishkek). He doesn’t seem to have taken part in the Central Asia Revolt and responded to the Russian revolution by returning to his hometown of Merke and founding the Union of Revolutionary Kazakh Youth. When the Bolsheviks took over the Russian government following the October Revolution, Turar joined the Bolshevik administrative center for his uezd and focused on managing the 1918 famine.

The Russian solution was to requisition food from the population, claiming it would be redistributed as needed. The Russians did not trust the indigenous people with food or supplies, believing they were hoarding necessities and would refuse to share with their Russian counterparts. Risqulov despised the Russian’s attempts to take food, writing in May 1918, that the requisition squads were “drunk and violent…taking whatever suited them” and contributing to a “atmosphere of animosity” between indigenous party members and the Russians. (Jeff Sahadeo, Russian Colonial Society in Tashkent, 1865-1923, pg. 212) In November of 1918, he wrote to the Bolsheviks of the situation in the Avilyo Ota uezd where half of the 300,000 Kazakh peoples had starved to death. Despite this ghastly statistic, the Soviets in the area were still levying an additional tax of 5 million rubles from the survivors. Risqulov called it colonial exploitation, the very thing the Communist Party was supposed to be fighting against.

Turar Risqulov

[Image Description: A black and white photo of a man sitting down, resting his chin in his hand. He has black hair and is wearing round, wire frame glasses, a white collared button down shirt, a grey vest, and a grey suit jacket. He has a small, black mustache]

Turar was rewarded for his hard work by being named Turkestan’s Commissar for Health. He moved to Tashkent, but remained focused on the famine, creating the Central Commission for Struggle Against Hunger in November 1918. In an attempt to apply Communist language to the deteriorating situation, he would write that the “starving mass, being today a backwards and darkened population, is the real proletariat of Turkestan. (Xavier Hallez, Turar Ryskulov: the Career of a Kazakh Revolutionary Leader, pg. 127) His efforts were stymied by Russian settlers and Bolsheviks who believed they were better suited to manage the food supply.

From 1916 to 1918, Risqulov develops a political ideology for the first time. He wasn’t involved with the Jadids or Alash Orda and it doesn’t seem like he was involved with the Central Asian Revolt of 1916. When the February Revolution occurred in 1917, Risqulov returns to his hometown and tries to create a political entity, but it doesn’t get a lot of traction and at some point, he becomes involved with the Soviets in the region. As we’ve mentioned in other episodes, Risqulov is a nationalist-Communist. Someone who engages and seems to believe in Communist theory and values while also engaging in nationalism and nation-building. It’s this dual approach that allows me to form a working relationship with Bolshevik agent Pyotr Kobozev and the various Muslim reformists in Turkestan.

The Musburo

As we discussed in our last episode, Pyotr Kobozev went to Turkestan to end the strife between the Russian Settlers and Bolsheviks and the indigenous peoples. His record is mixed, but one of his most significant decisions was creating the Central Bureau of Muslim Communists organizations of Turkestan, also known as the Musburo.

The purpose of the Musburo was to organize the indigenous population around Communist principles. They created a network of organizations and conferences all over Turkestan, providing the indigenous peoples an institutional framework to wield governmental power. Basically, a Communist approved Kokand government. The Musburo had the right to communicate directly with Moscow and ran their own paper, the Ishtirokiyun.

Risqulov was named the chairman of the Musburo in 1919. He used this position to further develop his own theory of anticolonial communism and to address the famine and ethnic violence ravaging Turkestan. He also used the Musburo and, later, the Muslim majority in the Central Executive Committee, to create a network of indigenous communists and allies, empowering the indigenous population. Despite this new power, Risqulov still experienced great resistance and pettiness from the Russian Soviets and Settlers, particularly around matters of food and supplies.

In 1919, Risqulov estimated that half of the population of Turkestan was starving as food production had declined by half from two years earlier. The local Soviets responded by diverting grain to Russian cities in Turkestan, dissolving the Old city soviet provision committee, and banning non-Russians from seeking food from any state organ. They also organized new provision brigades composed of Russian workers to confiscation, purchase, or trade food from the countryside and encourage peasants to increase their yields for the following year. These brigades had the right to take all food beyond the peasant’s personal needs without compensation.

Turar Risqulov offers words of caution, even though he approved of the brigades for Russian villages, “the city must understand the Muslim mass has a different psychology than the Russian peasants…[We] need to keep in mind the fanaticism of the population and the danger of approaching them.” He wanted to protect the Muslim villages from the brigades and avoid feeding the flames that was the Basmachi. The Soviets agreed to send Muslim agents to Muslim villages when possible but otherwise dismissed Risqulov’s warning. Predictably, the requisitions failed, and the Soviets were forced to disband the brigades in October 1919. This didn’t prevent increased Basmachi activity or Russian peasant uprisings.

Ideological Development

While Risqulov was trying to manage a famine and develop indigenous power during a civil war, he was also developing a nationalist-communist ideology that centered a Turkic nationality and nation-state.

Risqulov believed that the best future for Turkestan was a region wide national identity, one that could unite all peoples of Central Asia. He wanted to re-establish Turkestan as the Turkic Soviet Republic, an identity that could encompass all Central Asian nationalities. He also wanted to remain the Communist Party of Turkestan (KPT) to the Communist Party or Turkic Peoples. He wrote that the

“Turkic Soviet Republic should fully answer to the customary, historical, and interests of the international unification of toiling and oppressed peoples” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 111

He wanted the already existing Turkic republics to unite with Turkestan and hoped that future republics (such as Bukhara, Khiva, Afghanistan, etc.) would join the republic as well.

He believed in Communism but was also keen to put out when the Bolsheviks failed to live up to their ideals. In 1920, he would write Lenin that:

“In Turkestan, there was no October Revolution. The Russians took power and that was the end of it, in the place of some governor sits a worker, and that’s all...the October Revolution in Turkestan should have been accomplished not only under the slogans of the overthrow of the existing bourgeois power, but also of the final destruction of all traces of the legacy of all possible colonialist efforts on the part of Turkist officialdom and kulaks” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, 108-109

Turar pulled out the Bolshevik’s mentions of self-determination, equality, and anti-colonial rhetoric and used to shape his own ideology of anticolonialism. He wrote that:

“One of the most important conditions for the achievement of the goal [of Communism] advanced by the Communist Party is the self-determination of oppressed…peoples…. If Soviet Russia needs to show the working class of Western capitalist countries the correctness of its system, then it needs even more to show the oppressed East the proper restricting of the social life of Muslim society in Turkestan and elsewhere.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 110-111

He would go even further stating that:

the crude colonialism of Tsarism produced hate and distrust toward the ruling nation. If the proletariat of the ruling nation now scorns the proletariat of the oppressed nations, it will only produce more distrust” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 110-111

Turar was basically arguing that for Communism to thrive in former and current colonies, then it needed to focus on anti-colonialism, holding up Turkestan as an example of how Communism restored rights to indigenous actors and implemented policies that would address harms caused by colonialism while also building the capacity and infrastructure to have a thriving future. He believed in a united republic that honored individual communities, traditions, and histories.

Turar wasn’t the only person arguing this, but he didn’t have the organizational ability to unite with other groups and Muslim intellects who were writing the same things. No was Moscow keen to create organizations or opportunities for Turkestani Communists to meet and interact with their other Muslim counterparts.

Risqulov vs Frunze

Despite Risqulov’s and Kobozev’s best efforts, Moscow believed a sterner hand was needed to restore order to Turkestan. Thus, in October 1919, they sent the Turkestan Commission also known as the Turkkomissa. This Commission consisted of plenipotentiaries supported by General Mikhail Frunze’s Red Army and were meant to govern the region. At first, the Musburo were hopefully that the Commission would be a stronger ally against the Russian settlers, but it quickly became clear that the Commission planned on being the ultimate authority in the region. This stance was solidified with the arrival of General Mikhail Frunze in Tashkent in February 1920. Born in Pishpek (now Bishkek), he was considered as a Turkestani, even though for the indigenous peoples he was just another settler. He attacked the Musburo for their “narrow petty bourgeois nationalism” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 114) and suggested abolishing the KPT and starting new.

Turar Risqulov

[Image Description: A sepia tone photo of a man with thick dark hair and a short dark mustache. He is wearing a round, wire frame glasses. He is looking down at a white paper. He is wearing a white, collared button down shirt, a black tie, a black vest, a black shirt jacket, and a dark coat that sits on his shoulders.]

For Frunze, the nationalist communists had grown too emboldened and needed to be reminded of their place. For Risqulov and the others, it was a matter of addressing the continued colonization of Tsarist Russia wearing the guise of Bolshevism. A war developed between the Commission and the Muslim Communists with the Muslim Communists refusing to follow any order from the Commission unless it had been approved by the Musburo. Furthermore, Risqulov threatened to expulse the Commission since it violated territorial integrity of Turkestan.

Eventually Risqulov decided to take his case to Lenin himself. In May 1920, he organized and led a delegation to Moscow, followed by a delegation sent by the Turkestan Commission, and pleaded his case. Risqulov reminded Lenin of Turkestan’s significance to the Soviet’s Eastern policy and the importance of dismantling colonialism in former colonies. Risqulov demanded that Turkestan be named an autonomous state with rights to conduct its own foreign policy and print its own money amongst other things.

Lenin refused and the Politburo published a resolution on June 22, 1920, announcing that Turkestan was an autonomous part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). Russia would manage its external relations, trade, and all military affairs and its internal economy had to operate within the framework of economic plans established by the center. The Commission was changed to the Turkestan Bureau (Turkburo) and would eventually become the Central Asia Bureau or Sredazburo in 1922. Finally, Moscow forced reelections in Turkestan, kicking Risqulov and his followers out of office. This was followed by a sweep of all nationalists in the region with nearly two thousand Europeans deported from Turkestan throughout the autumn of winter of 1920 into 1921. Risqulov, himself, was banished to a desk job first in Narkomnats, then Moscow (where he served as the Deputy People’s Commissar for Nationalities), and finally Baku.

Creation of Central Asian Nation State

Risqulov returned to Turkestan in 1922 because the Bolsheviks were terrified of the influence Turkish leader, Enver Pasha, and Bashkir nationalist Zeki Validov Togan were having on the people of Turkestan. Both leaders had sided with the Basmachi bringing them the legitimacy and organizational skills needed to defeat the Bolsheviks. While Enver Pasha would die in combat, Risqulov actually reached out to Togan to negotiate peace, but Togan refused to work with the Soviets and fled Turkestan.

Risqulov was named Chairman of the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Turkestan ASSR) in 1922 and sat on the Sredazburo.1922-1924 would be spent “Sovietizing” Turkestan after close to a decade of war, famine, and ethnic violence. This involved revolutionary education and social norms, redistributing land, destroying all sources of nationalism and anti-Bolshevism, and integrating the economy.

For Turkestan, the economy equaled cotton. In September 1921, the Council of Labor and Defense established the Main Cotton Committee (Glavkhlopkom) which was responsible for buying the entire cotton harvest in the USSR and ensure nothing disturbed the cotton market. For Central Asia, this meant that cotton was its number one product and everything else should be sacrificed to produce as much cotton as possible. Additionally, the price of cotton was indexed to the price of grain, which never covered the costs of production. Risqulov wrote in 1923 that the Soviets should pay Turkestan world prices for its cotton, but this was ignored.

While the struggle of ultimate control between the indigenous people and their Soviet partners would continue for most of the 1920s, they also supported many of the Soviet’s initiatives and Risqulov was no different. While he did resist measures he thought were harmful to Turkestan (such as the cotton price indexing), he also worked hard to bring about a socialist utopia to the region. He supported educational opportunities, such providing funds so students could study abroad, expanding the communist party within Turkestan, liberating women, and land redistribution.

However, his power within Turkestan was curbed by a growing distrust from Moscow and a new crop of true Muslim Communists who weren’t tainted by any nationalist inclinations. This new cadre pushed out the old Jadids, Alash Orda, and Nationalist-Communists and later their disagreements would turn deadly.

Later Life and Execution

Risqulov spent the last decade of his life serving the Soviet Union in several different capacities. He seems to have served a term as the Komintern’s representative to Mongolia in 1925 before returning to Turkestan. From 1926-1927 he served on a commission to study the relationship between the central organs of the Russian Republic and the national autonomous republics. He tried one last time to advocate a nationalistic policy that would unite the Turkic republics, but it didn’t go anywhere. He was also involved with the building of the Turkestan-Siberian Railway, a 1,520 mm broad gauge railway that connects Central Asia to Siberia, starting in Tashkent, making a detour to Almaty in Kazakhstan, and ending at Novosibirsk.

His most tragic assignment was managing the collectivization and sedentarization of Kazakhstan in the 1930s. The goal was to end nomadism in Kazakhstan and end, not only private property in the Steppe, but disrupt the relationship the Kazakhs had with their own land. Many Kazakhs appealed to Risqulov to assist with the famine (one can imagine not only how nightmarish this must have been him for him, but also the bitter taste of déjà vu as he was once again force to address a famine partially caused by Russian mismanagement). Despite his attempts to diminish the brutal affects of collectivization, approximately 1.3 million Kazakhs died from the famine.

Turar Risqulov was arrested in 1937 during Stalin’s Great Purge and was executed in 1938. His crime was being a nationalist communist.

Turar Risqulov is a perfect example of the contradictory nature of Soviet intervention in Central Asia from 1917 to the 1930s. The Soviets allowed for indigenous participation and culmination of power in their system of government, but the indigenous person in question had to be loyal to Communism and Communism alone. So, while the Bolsheviks created opportunities for Risqulov to exercise real political power and allowed him to join their party and ideology, the Soviets also marginalized that power and later turned against it. As the leadership changed in Moscow and new policies were put in place, the indigenous peoples of Central Asia felt their power shrink. Soon those, like Risqulov, who were instrumental in salvaging Central Asia from the violence of the Russian Civil War were marked as the Soviet’s greatest enemies and eliminated. Whatever little freedoms Risqulov and others like him tried to carve out of the Soviet Union were eliminated as well, replaced by sycophancy and corruption.

References

“Turar Ryskulov: the Career of a Kazakh Revolutionary Leader during the Construction of the New Soviet State, 1917-1926” by Xavier Hallez

Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR by Adeeb Khalid

Russian Colonial Society in Tashkent, 1865-1923 by Jeff Sahadeo

Central Asia: A History by Adeeb Khalid

#queer historian#history blog#central asia#central asian history#queer podcaster#spotify#turar risqulov#turkestan#kazakhstan#musburo#soviet union#Spotify

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tashkent, I love you

#cottagecore#forestcore#goblincore#nature#naturecore#forest#Central Asia#Tashkent#uzbekistan#uzbek#soviet#sovietcore#summer#food#garden#travelling#travel#jewelry#jewellery#craftmanship

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Photos of Soviet Turkmenistan from the Soviet Ukrainian photo book "Song of Our Native Land" a book dedicated to the 60-year anniversary of the USSR. 1982

1-2. "Ashgabat, the capital city of the Turkmen SSR"

3. "The blossoming orchards of Turkmenia"

4. "On Kara-Kum Canal"

5. "Gas complex preparation plant"

6. "Mechanized cotton-picking"

7. "Experts of golden patterns"

8. "A national dance"

#communism#history#socialism#leftism#marxism#marxism leninism#asia#soviet union#ussr#ussr history#turkmenistan#Turkmenia#central asia

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Traditional carpets depicting Soviet propaganda from the Caucasus region (primarily Azerbaijan) and Central Asia. Source:

#i hope that posting stuff related to azerbaijan isnt moraly murky#obviousy the unveiling ones are particularly bleak#azerbaijan#carpets and rugs#soviet#soviet union#soviet propaganda#caucasus#central asia#asian art#ussr#art history

1 note

·

View note

Text

mixing not just the histories but physical costumes and clothing of scotland and central asia sure was a ..... series of choices

#gd but the way that the local imperial officer talking about controlling the aldhanis and putting bars in the way of their sacred pilgrimage#... chilling#anyway its filmed in scotland and absolutely references the highland clearances (which you should read about)#but imho the costumes strongly reference central asia#where the soviet union forcibly cleared and resettled huge numbers of people and controlled their religious rites#andor thoughts

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saryozek / Сарыөзек ( Kazakhstan )

#Сарыөзек#soviet architecture#soviet art#soviet union#ussr#kazakhstan#kazakhstantravel#pickoftheday#explore#soviet#small town#streets#photooftheday#adventure#central asia#visitkazakhstan#kazakh history#travelphotography#buildings#aroundtheworld#architecture#travel#trip#cccp#world

18 notes

·

View notes