#central asian literature

Text

My Love for Central Asian Literature Part 1 – Abdurauf Fitrat, Abdulla Qodiry, and Cho’lpon

I’m currently working on a script for my history podcast, the Art of Asymmetrical Warfare, about three Central Asian literary giants: Abdurauf Fitrat, Abdulla Qodiry, and Abdulhamid Sulayman o’g’li Yusunov also known as Cho’lpon and it got me thinking about their influence on my historical interests, reading tastes, and writing style.

If you’re wondering why a podcast about asymmetrical warfare is talking about three Central Asian writers, you should check out my upcoming podcast episode. 😉

How I Became Interested in Central Asian Literature

My interest in Central Asia has been a long time percolating and it was just waiting for the right combination of sparks to turn it into a hyperfixation (sort of like my interest in the IRA). I went to the Virginia Military Institute for undergrad and majored in International Relations with a minor in National Security and my focus was on terrorism. So, I knew a lot about Afghanistan and Pakistan and the “classic” “terrorists” like the IRA, the FLN, Hamas, etc. and I knew of the five Central Asian states (one of my professors was banned for life from either Turkmenistan or Tajikistan and sort of life goals, but also please don’t ban me haha), but my brain bookmarked it, and I went on my merry way.

Then I went to University of Chicago for my masters, and I took my favorite class: Crime, the State, and Terrorism which focused on moments when crime, government, and terrorism intersect. This brought me back to Pakistan and Afghanistan, but this time focusing on the drug trade which led me to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan and their ties to the Taliban and it was sort of like an awakening. I suddenly had five post-Soviet states (if you know me, you’ll know I’m fascinated by post-Soviet states) with connections to the drug trade (another interest of mine) and influenced by Persian and Turkic identities. I was also writing a scifi series at the time that included a team of Russian, Eastern European, and Central Asian scientists and officers, so the interest came at the right time to hook my brain. Actually, if you buy my friend’s EzraArndtWrites upcoming “My Say in the Matter” anthology, you’ll read a short story featuring Ruslan, my bisexual, Sunni Muslim, Uzbek doctor who was inspired by my sudden interest in Central Asia.

Hamid Ismailov’s the Devils’ Dance

I wanted to know more beyond the drug trade and usually when I try to learn about a place whether it be Poland, Ireland, or Uzbekistan, I go to their music and literature. This led me to one of my all-time favorite writers Hamid Ismailov and my favorite publishers Tilted Axis Press.

Tilted Axis Press is a British publisher who specializes in publishing works by mainly Asian, although not only Asian writers, translated into English. They publish about six books a year and you can purchase their yearly bundle which guarantees you’ll get all six books plus whatever else they publish throughout the year. I’ve purchased the bundle two years in a row, and I haven’t regretted it. The literature and writers you’re introduced to are amazing and you probably won’t normally have found unless you were looking specifically for these types of books.

Hamid Ismailov is an Uzbek writer who was banished from Uzbekistan for “overly democratic tendencies”. He wrote for BBC for years and published several books in Russian and Uzbek. A good number of his books have been translated into English and can be found either through Tilted Axis or any other bookstore/bookseller. Some of my favorites include Dead Lake, the Manaschi, the Underground, and the book that inspired everything the Devils’ Dance.

Tilted Axis’ translation of The Devils’ Dance came out the same year I was working on my masters, and I bought it because it is a fictional account of Abdulla Qodiriy’s last days while in a Soviet prison. He goes through several interrogations and runs into his fellow writers and friends: Fitrat and Cho’lpon. Qodiriy is written as detached from events while Cho’lpon comes across as very sarcastic, as if this is all a game, and Fitrat is interestingly resigned to the Soviet’s games but seems to have some fight in him. Qodiry distracts himself from the horrors around him by thinking about his unwritten novel (which he really was working on when he was arrested by the NVKD). His novel focuses on Oyxon, a young woman forced to marry three khans during the Great Game. His daydreaming takes a power of its own and he occasionally slips back to talk with historical figures such as Charles Stoddart and Arthur Connolly-two British officers who were murdered by the Khan of Bukhara (not a 100% convinced they didn’t have it coming).

We spend half of the narrative with Qodiriy and the other half with Oyxon as she is taken from her home and thrown into the royal court of Kokand’s khans where she is raped and mistreated and has to survive the uncertain times of Central Asia during the Great Game. She is passed from Umar, the father, to Madali, the son, to the conquering Khan of Bukhara, Nasrullah who eventually murders her and her children. From a historical perspective, I have a lot of questions about Nasrullah because a lot of sources write him off as a cruel tyrant and nothing more which usually means there’s more…Before Oyxon and Qodiriy are taken to their deaths, there is a poignant scene where the two timelines merge into one that will stay with you long after the novel is over.

The book is a masterpiece exploring themes of colonialism, liberty, powerlessness in face of overwhelming might, the power of the human mind and spirit, the endurance of ideas, even when burned and “lost”, as well as being a powerful historical fiction about two disruptive periods in Central Asian history. It’s also a love letter to the three literary giants of Uzbek fiction: Abdurauf Fitrat: a statesmen who crafted the Turkic identity of Uzbekistan, a playwright and statesmen, Abdulla Qodiriy who created the first Uzbek novel (O’tgan Kunar which was recently translated by Mark Reese and can be bought in most bookstores), and Cho’lpon who created modern Uzbek poetry (you can buy his only novel Night translated by Christopher Fort and a collection of his poems 12 Ghazals by Alisher Navoiy and 14 Poems by Abdulhamid Cho’lpon translated by Andrew Staniland, Aidakhon Bumatova, and Avazkhon Khaydarov in any bookstore).

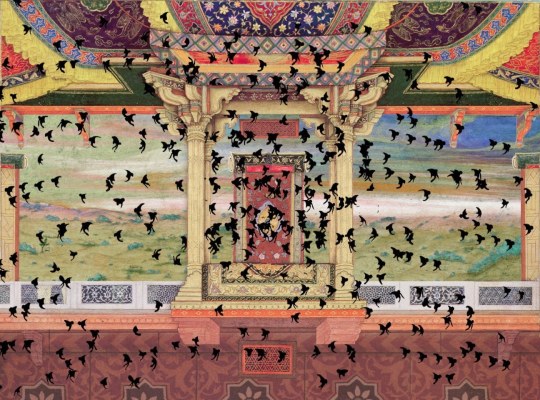

City of Kokand circa 1840-1888, thanks to Wikicommons

All three men were Jadids (modern Muslim reformers) who worked with the Bolsheviks to stabilize Central Asia, helped create the borders of the five modern Central Asian states, and were murdered by the Soviets during Stalin’s Great Purge of the 1930s. It was illegal to publish their work until the glasnost. Check out my history podcast to learn more about the Jadids and the Russian and Central Asian Civil Wars.

From a literary perspective however, Ismailov wrote the Devils’ Dance similarly to Qodiriy’s own O’tgan Kunlar and Cho’lpon’s Night (whereas Ismailov’s other books: Dead Lake and the Underground are more Soviet era Central Asian literature and his newest book the Manaschi is more post-Soviet). Like Qodiriy and Cho’lpon, Ismailov writes about MCs who are not the master of his own fate, but instead are going through the motions of a fate already written, one of his MCs is a woman unfairly caught in a misogynistic system that uses women as it sees fit (although I would argue that Hamid gives his women characters more agency than either Qodiry and Cho’lpon), and he writes about the corruption and inefficiencies of whatever government agency is in control at the time – whether it be a Russian, a Khan, or an indigenous agent of said government. All three books end in death, although only Cho’lpon’s Night and Ismailov’s the Devils’ Dance end in a farce of a trial. Even stylistically Ismailov mimics the rich and dense language of Qodiriy whereas I find Cho’lpon’s style crisper although no less rich for it.

Abdurauf Fitrat’s Downfall of Shaytan

While Ismailov led me down a historical rabbit hole which is captured on my history podcast, I also wanted to see if any of Fitrat’s, Qodiry’s, or Cho’lpon’s work had been translated into English.

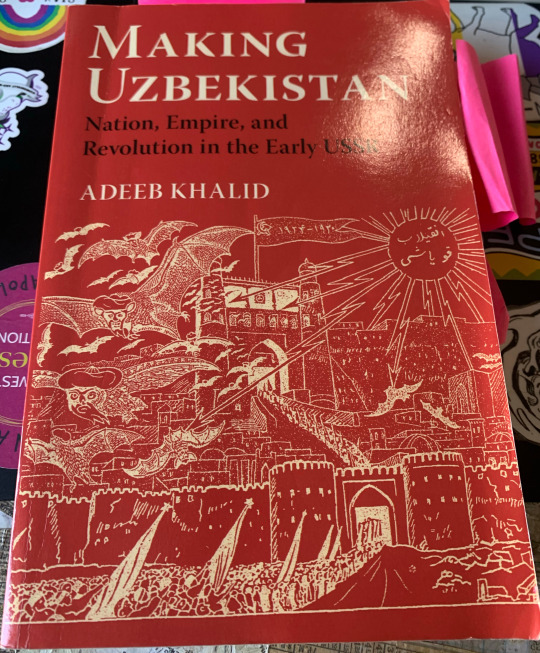

So far, I can’t find anything by Fitrat except excerpts in the Devils’ Dance and Making Uzbekistan by Adeeb Khalid (one of my all-time favorite history books by one of my favorite scholars who also happens to be very kind and patience and I still can’t believe I interviewed him for my podcast).

Fitrat wrote a specific play I really want to read called Shaytonning Tangriga Isyoni which Dr. Khalid translated as Shaytan’s Revolt Against God. According to the summary provided by Dr. Khalid it is a challenging take on the Islamic version of Satan’s downfall.

According to Dr. Khalid, in Islamic cosmology God created angels from light and jinns from fire and they could only worship God. When God made Adam, He commanded all angels and jinn to bow before him. Azazel (who would become Shaytan) refused claiming he was better than Adam who was made out of clay. He was cast out of heaven and became Shaytan/Iblis.

Fitrat reimagines Shaytan’s defiance as heroic. He is disgusted by the angels’ submissive nature and God’s ability to create anything and yet he chooses to create servants. Azazel has seen God’s plan to create another being out of clay and have the angels worship him as well, which Azazel sees as a betrayal on God’s part. Gabriel, Michael, and Azrael try to convince Azazel to see reason and instead he brings his grievance to the other angels who are confused. God intervenes and the angels give in, but Azazel continues to defy God. God strips him of his angelic nature, and he turns into Shaytan who warns Adam of God’s treacherous nature and vows to free him and all other creatures from God’s trickery.

Doesn’t it sound amazing?! Fitrat has outdone Milton in terms of completely overturning God’s and Satan/Shaytan’s rules (also no wonder he was marked for execution right? Complete firebrand and pain in the ass (and I mean that with love)) and I really want to read it. So, either someone needs to translate this into English, or I need to learn Persian/Uzbek, which ever happens first, haha (judging on how my Russian is going…)

Abdulla Qodiry’s O’tgan Kunlar

While I can’t find any of Fitrat’s work in English, there have been two translations of Abdulla Qodiriy’s novel and the first ever Uzbek novel O’tgan Kunlar. In English, the title translates as Days Gone By or Bygone Days. There are two translates out there: Days Gone By translated by Carol Ermakova, which is the version I’ve read, and Otgun Kunlar by Mark Reese, which I haven’t read yet but I’ve heard him speak (and actually spoke to him about his translation – thank you Oxus Society) so you can’t go wrong with either one.

O’tgan Kunlar is an epic novel set in the Kokand Khanate in the 18th century and is about Otabek and his love Kumush. There’s also a corrupt official, Hamid who hates Otabek because Otabek is a former who wants to change the society Hamid benefits from. Hamid tries to get Otabek killed for treason because of his reformist believes, but the overthrow of the corrupt leader of Tashkent (who Otabek worked for) saves Otabek’s life. However, the corrupt leader’s machinations convince the Khan to declare war against the Kipchaks people, who are massacred. Otabek and his father vehemently disagree with the massacre of the Kipchaks.

Once Otabek is released and gets revenge against Hamid, he marries Kumush without his parent’s approval and is torn between the two families. His mother hates Kumush and forces him to take a second wife, Zainab. Obviously, things go terribly wrong as Otabek doesn’t even like Zainab and Kumush doesn’t know how to feel about her husband having a second wife. Zainab hates her position within the household and eventually poisons Kumush.

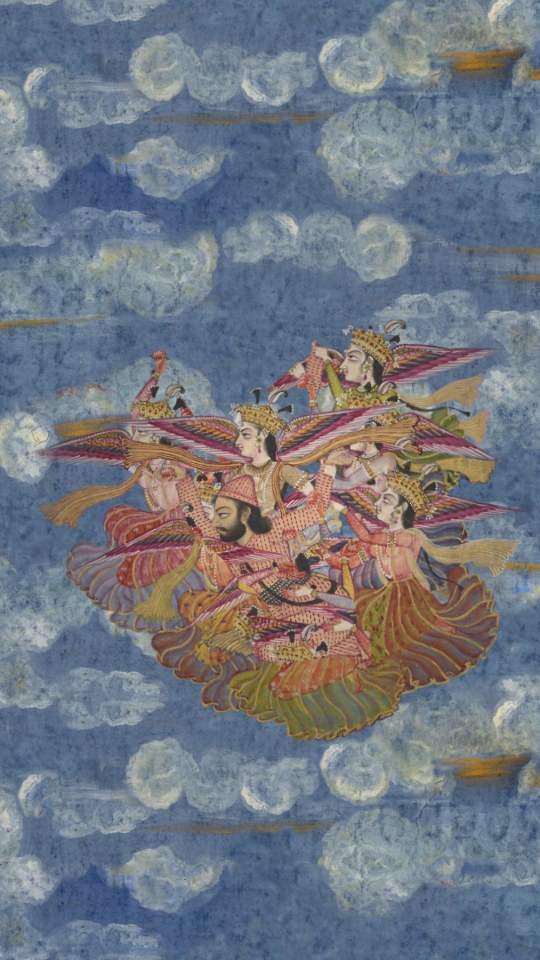

Abdulla Qodiriy thanks to Wikicommons

O’tgan Kunlar is considered to be an Uzbek masterpiece that is central to understanding Uzbekistan. Not only is it a great tragic love story, but it also highlights some of the things Qodiriy was thinking about as he engaged with other Jadids. Just as Otabek argued for reforms especially in the educational, social, and familial realms, the Jadids were making the same arguments. We can also see the Jadid’s struggle with the ulama and the merchants in Otabek’s struggle with Hamid. Qodiry attempts to capture the struggle women went through by writing about the horrors for arrange marriages and polygamy, but Kumush is an idealized version of a woman. She is the pure “virgin” like Margarete from Faust while the other two female characters; Otabek’s mother and Zainab are twisted, bitter woman who hurt those they “love”. One could argue they’ve been corrupted by the society they live in, but they also lack the depth of Otabek and even his father.

One of the most interesting parts of the novel is the massacre of the Kipchaks because it is written as the horror it was and both Otabek and his father condemn the action. His father even claims that there is no sense if hating a whole race for aren’t we all human? Central Asia is a vast land full of different peoples who share common, but divergent histories and while these differences have led to massacres, there have also been moments of living peacefully together. It’s interesting that Qodiriy would pick up that thread and make it a major part of his novel because this was written during the Russian Civil Wars and the attempts to create modern states in Central Asia. The Bolsheviks really pushed the indigenous people of Central Asia to create ethnic and racial identities they could then use to better manage the region and so one wonders if Qodiriy is responding to this idea of dividing the region instead of uniting it.

Cho’lpon’s Night

While O’tgan Kunlar is a beautiful book and Qodiriy is a masterful writer, I prefer Cho’lpon’s Night (although don’t tell anyone). Night was supposed to be a duology, but Cho’lpon was murdered before he could finish the second book. Cho’lpon wrote Night in 1934, after years of being attacked as a nationalist. It was a seemingly earnest attempt to get into the Soviet’s good graces. Instead, he would be murdered along with Qodiriy and Fitrat in 1938.

Night is about Zebi, a young woman, who is forced to marry the Russian affiliated colonial official Akbarali mingboshi. The marriage is arranged by Miryoqub, Akbarali’s retainer. Akbarali already has three wives and, like in O’tgan Kunlar, adding a new wife causes lots of problems in the household. Meanwhile Miryoqub falls in love with a Russian prostitute named Maria and they plan to flee together. While they are fleeing they met a Jadid named Sharafuddin Xo’Jaev and Miryoqub becomes a Jadids. Meanwhile Akbarali’s wives conspire against Zebi and attempt to poison her but she unwittingly gives it to Akbarali instead. Zebi is arrested and found guilty of murdering her husband and sentenced to exile in Siberia. The book ends with Zebi’s father, who encouraged her marriage to Akbarali, is driven made by his daughters fate and murders a sufi master while Zebi’s mother goes mad, wandering the streets and singing about her daughter.

Like Qodiriy, Cho’lpon is interested in examining governmental corruption, the need for reform, and women’s plight, but Cho’lpon is less resolute than Qodiriy. Cho’lpon’s novel is constructed similar to poetry: an indirect attempt to capture something that is concrete only for a moment.

His characters are own irresolute or ignorant of important pieces of information meaning they are never truly in full control of their fates. Even Miryoqub’s conversion to Jadidism is to be understood as a step in his self-discovery. In Cho’lpon’s world, no one is ever truly done discovering aspects of themselves and no one will ever have true knowledge to avoid tragedy.

Cho'lpon courtesy of Wikicommons

It is interesting to read Night as Cho’lpon’s own insecurity and anxiety about his own fate and the fate of his fellow countrymen as Stalin seemingly paused persecuting those who displeased him. While Qodiriy crafted and wrote O’tgan Kunlar in the 1920s, which were unstable because of civil war, but promised something greater as the Jadids and Bolsheviks regained control over the region, Cho’lpon wrote Night during the height of Stalin’s Great Terror, most likely knowing he would be arrested and executed soon.

Both novels are beautifully written historical novels about a beautiful region, but I prefer Cho’lpon’s poetic prose and uncertainty.

Conclusion

Reading the works of Fitrat, Qodiriy, and Cho'lpon not only introduced me to a history I knew little about, but also introduced me to a whole literature I never knew existed. The books mentioned in this blog post are beautiful pieces literature and will challenge how you see the world and how much literature we miss out on when we don't read beyond authors who work in our native tongues.

The canon of Central Asian literature is immense, with only a handful of books and poems translated into English. I hope more works are translated so other people can engage with these books and poems and learn about these writers and the circumstances that shaped them. And, if you haven't, go check out Tilted Axis who are doing amazing work translating books so people can engage with them.

If you're enjoying this blog, please join my patreon or donate to my ko-fi

#central asian history#central asian literature#abdurauf fitrat#abdulla qodiriy#cho'lpon#O'tgan Kunlar#Days Gone by#Night#Hamid Ismailov#the Devils' Dance#Soviet Union#Soviet Central Asia#Uzbekistan

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Boğaç's Triumph & Dirse Han's Betrayal

Book of Dede Korkut: Boğaç, swiftly recovered, excelling in skills. Forty traitors plotted against Dirse Han, aiming to sell him to infidels.

With swift steed and a poet’s tongue, Boğaç recovered in forty days. Excelling in horsemanship, archery, and marksmanship, he surpassed his former self. Learning this, forty traitors schemed: “Dirse Han, if he learns his son is well, won’t spare us. Best to seize him, sell to infidels.” They deviously approached, capturing a pale Dirse Han. Tying his hands, they led him toward heathen lands. The…

View On WordPress

#Book of Dede Korkut#Central Asia#Central Asian literature#cultural heritage#Dede Korkut#Epic tales#Folklore#Oral tradition#Turkic mythology#Turkish folklore

0 notes

Text

Cho’lpon and Abdulla Qodiriy

If you didn’t listen to our podcast episode on Abdurauf Fitrat, you may be wondering why a podcast about asymmetrical warfare is talking about two writers. There’s the personal reason and the “academic” reason.

On the personal side: Abdurauf Fitrat, Cho’lpon, and Abdulla Qodiriy are why I became interested in Central Asian history, particular during the Russian Civil War and the Sovietization of the Central Asian States. So, this episode is a chance for me to highlight fascinating people who inspired this podcast.

Academically, Cho’lpon, Qodiriy, and Fitrat were key members of the Jadid movement who shaped the cultural landscape of Turkestan during the civil war. They are representative of the people the Soviets found threatening as they tried to solidify their hold on the region. So, even if they weren’t physically fighting, they were building a cultural and social framework that fundamentally threatened the Soviet dream projects for the region.

Cho’lpon

Cho’lpon, also known as Abdulhamid Sulaymon ogli Yunusov is considered to be one of the great Uzbek poets of the 20th century. He fundamentally reshaped poetry while also working as a playwright, novelist, translator, and political activist. He was born in Andijan to a wealthy merchant in the 1890s and started his education in a Russian school. His father wanted him to attend a madrasa and he ran away to Tashkent, where he tried to make it as a writer. While in Tashkent, he became involved in editing and writing for Jadid journals and in their intellectual and literary circles. He was close to both Mahmud Xo’ja Behbudiy (who was murdered by the Bukharan Emir during the Russian/Central Asian Civil Wars) and Abdurauf Fitrat, who became his mentor, pushed him to focus on poetry, and gave him his penname: Cho’lpon which translates to morning star.

Russian Civil War

When the Russian Revolution occurred, there were mixed reactions within the Jadids. Fitrat would write that this was just one more calamity to afflict the Russians, but Chol’pon wrote a poem called the Red Banner, celebrating the Revolution. This excerpt translated by Christopher Fort gives you a sense of how that poem went:

“Red banner!

There, look how it waves in the wind,

As if the qibla wind is greeting it!

It is not glad to see the poor in this state,

For the poor man has the right because it is his.

Has the red blood of the poor not flown like rivers

To take the banner from the darkness into the light?

Are there no workers left in Siberian exile

To take the banner to the oppressed and weak people?

You, bourgeoisie, conceited upper classes, don’t approach the red banner!

Were you not its bloodsucking enemy?

Now the black will not approach those white rays of light,

Now those black forces’ time has pass!” - Cho’lpon, Night, pg. 8-9

Cho’lpon was involved in the creation of the Kokand Autonomy and even wrote a poem to celebrate its creation and mourned its destruction by the Tashkent Soviet. When the Bolsheviks entered the region, the Jadids welcomed them because they had no one else to support their work. The Jadids had always been a minority in the region and remained powerless and isolated as Turkestan succumbed to civil war. Working with the Bolsheviks, the Jadids helped overthrow the emirs, the Russian settlers, and the Basmachi.

For his part, Cho’lpon lived a wandering life after the fall of the Kokand Autonomy, apparently working at a theater briefly, but he still mourned the devastation the wars imparted on Turkestan, publishing a poem “To the Despoiled Land.” The excerpt I read is from Adeeb Khalid’s Book Making Uzbekistan

“O mighty land whose mountains salute the sky,

Why are there dark clouds over your head?

“Your beautiful green pastures have been trampled,

They have no cattle, no horses.

Which gallows have the shepherds been hanged from?

Why, instead of neighing and bleating,

There are only mournful cries?

Why is this?

Where are the beautiful girls, the youthful brides?

Is there no answer from heaven or earth?

Or from the despoiled land?!

Why is the poisoned arrow

Of the plundered, heavy crown still in your breast?

Why don’t you have the iron revenge

That once destroyed your enemies?

O, free land that has never put up with slavery,

Why does a shadow lie throttling you?” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 217

As we can tell from this poem, Cho’lpon was deeply affected by the destruction that was unleashed to the region. I don’t think anyone can blame him for, as we have mentioned many times in this podcast, the destruction was devastating and afflicted the indigenous populations the hardest. However, the Soviets would use these poems and this “anti-Bolshevik” sentiment against Cho’lpon in the 30s when Stalin’s Purge sought to break the Central Asian intelligentsia.

Crafting a Literary and Cultural Legacy

Cho’lpon returned to Bukhara in 1920 after Fitrat offered him a job to work at Axbori Buxoro the main newspaper of the People’s Soviet Republic of Bukhara

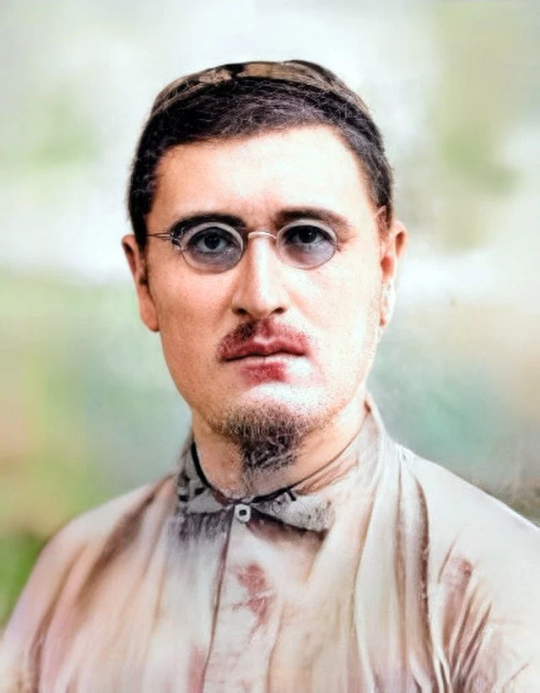

Cho'lpon

[Image Description: A color photo of a man wearing a skull cap, round wire frame glasses, and a tan shirt. He has short brown hair and a short, closely clipped mustache, and goatee. Behind him are out of focus trees]

Cho’lpon, like Fitrat, was heavily involved in crafting a Turkic specific identity for Turkestan, no longer writing in Persian, but in a Turkic language crafted by Fitrat, Cho’lpon introduced the Turkic meter to local poetry. He was a main contributor to the anthology Young Uzbek Poets and produced three collections of poems. He also translated several works in Persian and Russian, and introduced many Uzbeks to Shakespeare, Chekhov, and Gogol. He was a big supporter of rejuvenating the theater scene in Tashkent and wrote many plays. As the horrors of the war passed and the region entered a new decade, Cho’lpon and many Jadids saw the 1920s as a chance to rebuild. Cho’lpon believed that the revolution and civil war had created the conditions needed for the Uzbek state to take its place in the world. He would write in 1922:

“The famous Pobedonostsev, champion of the Christianizing policies of Il’minskii – who (himself) was a Rustam in the matter of Christianizing the Muslims of inner Russia and the teacher of our own Ostroumov to’ra – once wrote, “Among the natives, the people most useful, or at any rate the most harmless, for us are those who can speak Russian with some embarrassment and write it with many mistakes, and who are therefore afraid not just of our governors but of any functionary sitting behind a desk” Now we are earning the right to answer back not just in Russian, but in the languages of the civilized nations of Europe…I the free young men of the Uzbek [nation] and even its unfree young girls begin a revolt against the legacy of Il’minskii,…then we too can win our right to join the community of peoples without being beaten and humiliated” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 179

Cho’lpon was also involved in the “liberation” of women – although the Jadid’s definition of women’s liberation was different from the Bolshevik’s definition. The Bolsheviks pushed the unveiling of women and wanted to “Europeanify” Muslim women. This was partially a result of their own efforts to end gender standards, but it was also a direct assault on Islam. The Jadids support women’s rights and many unveiled their own wives. Cho’lpon wrote a play about the veil and his book Night is about the cruel fate of a girl forced to marry an official who already has three other wives and how the justice system fails its people, especially women. He was also against the practice to seclude women, believing it contributed to their lack of education and “backwardness.” Like other Jadids, Cho’lpon found it hard to align liberation in the theoretical realm and how it was implemented in the real world, especially when there was this undercurrent of “attacking” Islam. Many people in the rural areas and women did unveil were murdered by angry mobs. Cho’lpon would have several wives and it seems he struggled with maintaining relationships with women. I think it’s also fair to say that he had considerable trauma from the civil wars and the destruction he witnessed, and it most likely affected his relationship with those closest to him.

The Fall

The Jadids exercised considerable local power free in the early 1920s and were in the process of creating their own nationalistic Islamic, modern government. The Bolsheviks distrusted this government because it didn’t match Communist principles. In 1923, they struck fast and hard, forcing the Xojaev’ government to oust four of its own members, including Abdurauf Fitrat who was discussed last episode. Fitrat went into exile in Moscow in 1923. In 1924, Cho’lpon traveled to Moscow to study at the Uzbek Drama studio. At this point, he was still tolerated in Central Asia and the Soviets weren’t yet attacking him outright.

By 1927, several Russian writers and Central Asia leaders who wanted to establish their pro-Communist credentials were attacking Fitrat, Cho’lpon, Qodiriy, among others. One indigenous Communist would complain in 1927 that

“the Uzbek literary language of today is doubtless Cho’lpon’s language. Who is Cho’lpon? Whose poet is he? Cho’lpon…is a poet of the nationalist, patriotic, pessimist, intelligentsia. His ideology is the ideology of this group” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 334

He was also

“an idealist and an individualist, and therefore sees every political and social event not from the side of the masses but of his own personal point of view” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 334

In 1927, people were still brave enough to defend Cho’lpon. An indigenous writer, Oybek, wrote that Cho’lpon was like “Pushkin” who the young generation loved because of “his simple language, his delicious style, his technique” he was like Pushkin who “remained Pushkin even after the revolution because his works created the immortal richness of Russian literature” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 335). As the decade came to a close, Fitrat and Cho’lpon were used as a litmus test for whether someone was truly communist or not. If you defended Cho’lpon, you were lacking in your communist understanding and credentials. If you attacked him, you were safe from Stalin’s purge…for a time.

Pravda Vostoka, the Russian-language paper of the Central Committee of Communist Party of Uzbekistan published a news article titled “The Bark of the Chained Dogs of the Khan of Kokand.” It was one of the vilest attacks against Cho’lpon and other members of the Uzbek intelligentsia. The attack was written by El’ Registan, the future author of the Soviet national anthem of 1943. He claimed that Cho’lpon was a “prostitute of the pen…a stoker of chauvinism” whose anti-Soviet works were recited “in chorus by Basmachis taken prisoner and could now be heard all across Uzbekistan in any teahouse” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 372). The article went on to attack other writers, including Qodiriy and Fitrat, and was the first nail in Cho’lpon’s coffin.

For his part, Cho’lpon wrote that El’ Registan’s criticism was “an old matter, for which I was abused plenty then. Now it’s necessary to abuse me for new misdeeds, if there are any” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 372)

Why attack Cho’lpon? He was only a poet and playwright. What made him so threatening to the Soviet project? The answer may lie in his poem, Autumn in which he wrote:

“O you who come from cold places, clothed in ice

May that grating voice of yours be lost in the snow.

O you who pick the fruits of my garden,

May your dark heads be buried in the earth.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 217

Cho’lpon’s poems, while simple, were gut-wrenching and easy to understand and read. He was able to capture complex thoughts and translate them into the simplest of imagery and feelings for people to latch onto. Cho’lpon had a visceral reaction to the destruction of the civil war and channeled it into his writing and the Bolsheviks knew he wasn’t the only one upset about what had happened to the region. While the Basmachis contributed to the death and violence, it was also easy to blame the Russians for bringing the horrors with them, as they had done in the 1800s, with their colonial projects. Additionally, Cho’lpon was a Jadid, many of whom made up the current government of the Soviet republics. The reforms he and other Jadids fought for not only conflicted with Communist reforms, it was another option. Historically, the Communists have never tolerated dissent or other governmental options and so the Jadids had to go.

Cho’lpon’s greatest power though, may have been his own sarcasm. I mean this with all the love in the word but Cho’lpon was a sarcastic little bitch. In 1937, he was called before the Writer’s Union to answer charges of nationalism leveled against him and he replied,

“I have many mistakes, but I will correct them with your help. But what training have you given me in these years?”

and when they published his book without an explanatory preface he pointed it out, saying

“Abuse was required here, for the youth should not be allowed to read Cho’lpon’s work without an intermediary…Why did the work of this nationalist appear without a preface?” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 382

He seemingly didn’t take the criticism seriously and so had the potential to undermine the power of the various organizations put in place to keep writers and intellectuals in control.

Finally, and most damningly, Cho’lpon was a member of the old guard. He was part of a world that could not exist comfortably alongside Communism. He thought about government and the world with the bias and frameworks of a world that no longer existed. The Bolsheviks didn’t care if he could change his way of thinking or if he even wanted to. All that mattered was that he represented an old world and a potential new world that didn’t rely on Communist principles. That, in itself, was enough to murder him.

Arrest and Execution

Cho’lpon returned from Moscow in 1927 to stage plays around Uzbekistan, but returned to Moscow in 1932 when he could no longer tolerate being the Bolshevik’s favorite punching bag. While in Moscow he focused on translating European writers in Uzbek. He returned to Central Asia in 1934 and wrote his first and only novel Night. Whether he wrote it to earn the Bolshevik’s good graces, to write a final, scathing indictment of Communism, or just to play with the novel structure, is still up for debate. It is a challenging, but beautifully written and engaging book (I like it better than O’tkan Kunlar, but don’t tell anyone). It is supposedly the first book in a duology (Christopher Fort writes a great paragraph in his introduction to Night that this missing second book may have never even existed in any written format, but more of a thought in Cho’lpon’s head). It is about the horrors of a young woman faces when forced to marry an older man in the 1910s Central Asia. In the novel, he attacked the powerlessness of women in Turkestani society and the old practices of polygamy and forced marriages, but also corruption local rulers, the ulama, and even the Jadids themselves. You can buy Night translated by Christopher Fort from any bookstore. The book wasn’t hated by the Bolsheviks and Cho’lpon was arrested on July 13th, 1937.

He was charged as a nationalist and for being part of a secret society known as Milliy Ittihod (National Union) which we’ll cover in our next episode. Instead of denying the fake charges, Cho’lpon “confessed,” most likely because he was smart enough to understand there was no salvation possible. He was a dead man the moment he was arrested. The NKVD murdered him, alongside Fitrat and Qodiriy on October 4, 1938.

After he was murdered during the Stalinist purges, Cho’lpon’s works were never published or discussed until a brave editor attempted to include his poems in an anthology of Uzbek poetry in 1968 and was severely reprehended by the Soviet government. His work was passed around secretly, but he remained persona non grata until the fall of the Soviet Union. He has now been rehabilitated as a hero of Uzbekistan.

Abdulla Qodiriy

Abdulla Qodiriy was born in Tashkent in 1894 to a family of modest means. He attended a Russian-native class and worked several odd jobs before publishing his first piece in 1915. He did not reach critical fame until the 1920s, when he became an editor for the satirical magazine: Mushtum (the Fist). His work with Mushtum was groundbreaking. He took the living language he heard on the street and immortalized it in writing while perfecting satire in Uzbek literature.

Attacking the ulama

While he was a brilliant satirist, he could also be quite cruel and his favorite targets were the ulama, eshons, and bureaucrats. He often depicted the ulama as traditionalists and conservative who were narrow-minded and unable to understand the world and Islam. Despite this, he was well versed in Islam. He studied at the Beglarbegi Madara in Tashkent, he spoke Arabic, Persian, and Turkic. He even took part in discussions with ulama while he wrote Mushtum.

Abdulla Qodiriy

[Image Description: A green staamp with a black adn white photo of a man with short dark hair and a short mustache. He is wearing a black shirt and a grey suit coat. The stamp says 2004 125-00 on top, Abdulla Qodiriy (1894-1938) along the side, and O'zbekiston on the bottom]

An example of his wit can be found in his piece called Shayxontahur mausoleum. These mausoleums or shrines were an integral part of Central Asian life. The leaders of the Bukharan Soviet tour down shrines or mausoleums because they thought the ulama and eschons who cared for the shrine took advantage of the faith of the people and that the act of paying respects to the dead was “backwards.” So, they tore down the shrines and replaced them with schools. Qodiriy’s piece memorialized the demolition of the Shayxontahur mausoleum. It was a drawing of two devils: Iblis and Azazel, bemoaning the fact that “our house is being destroyed, the customs of our ancestors are being trampled” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 225). An accompanying article compared the two demons to certain ulama who had opposed the destruction. It is almost as scathing as some of Fitrat’s works deconstructing Islamic beliefs and traditions.

Qodiriy was a faithful Muslim who saw no contradiction between being a practicing Muslim and criticizing the ulama. During one of his interrogations with the NKVD, he said

“I am a reformist, a proponent of renewal. In Islam, I only recognize faith in God the munificent as the highest reality. As for the other innovations, most of them I consider to be the work of Muslim clerics - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 225

Success as a Novelist

In 1925, he published O’tgun Kunlar, his first novel and the first prose novel written in the Uzbek language. It is about Atabek and the love of his life Kumush. They marry, but Atabek’s mother hates Kumush and forces Atabek to take a second wife, Zainab. Things go terribly and people die. It sold 10,000 copies and his second novel, also a historical fiction, Mehrobdan Choyon (Scorpion in the Altar) which was published in 1928, sold 7000 copies.

In 1932, Qodiriy was admitted to the Uzbekistan Writer’s Union and two years later was actually elected as one of its delegates to the First Congress of the All-Union organization (where he and Sadriddin Ayni met Maxim Gorky and a picture was taken of the trio).

Despite finding success in the literary world, Qodiriy’s satire got him in trouble with the Bolshevik authorities and he was arrested in 1926 for making fun of Akmal Ikromov, a Communist Uzbek vying with Fazulla Xojaev for leadership over the Bukharan Soviet Republic. The Soviets had grown weary of Mushtum and used this as an excuse to get rid of its editor. He was thrown in jail for six months before being released – this time – but was banned from writing for the press. Instead, he a living writing original work and translating. He also found odd jobs such as writing the letter P in the first major Russian-Uzbek dictionary in 1934, translated a collection of antireligious essays, and worked on a film script based on Chekhov’s Cherry Orchard.

Arrest and Execution

Fayzulla Xojaev commissioned Qodiriy to write about the Uzbek peasantry which would be published as a serialized piece called Obid Ketmon. This worked was vilified for being anti-Soviet and Qodiriy was accused of being antisocial and apolitical. He, like Cho’lpon and Fitrat, became the favorite punching bag of anyone trying to prove their Communist credentials. He watched as Fitrat was arrested in July 1937, Cho’lpon was arrested on July 13th, 1937, and Qodiriy was finally arrested on the last day of 1937. Qodiriy was accused of being a member of a counter revolutionary organization that collaborated with Trotskyites, of carrying out anti-Soviet work in the press, and have direct relations with Xojaev and Ikromov (who were dead at the time of Qodiriy’s arrest). Qodiriy admitted to being a nationalist until 1932, but then mended his ways. According to his son, when Qodiriy was given his “confession” to sign (and would serve as his death warrant) he wrote:

“This resolution was announced me to (I read it); I do not agree to the charges contained in it and do not accept them” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 386

He, along with Fitrat and Cho’lpon, were murdered on October 4th, 1938.

References

Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR by Adeeb Khalid

Night by Cho’lpon, translated by Christopher Fort

Days Gone By by Abdull Qodiriy, translated by Carol Ermakova

#queer historian#history blog#central asia#central asian history#queer podcaster#spotify#cho'lpon#abdulla qodiriy#central asian literature#Spotify

0 notes

Text

honestly what an experience I just finished “Bygone Days: O’tkan kunlar” by Abdullah Qodiriy and my heart. That was a whole journey, a story about a young Uzbek man and his love and the obstacles life throws at them… a beautiful description of Uzbek culture in the 19th century… and I am REELING from the ending. There’s nothing quite like experiencing heart wrenching emotions caused by a good book with stunning writing! 😭

#uzbekistan#literature#booklr#abdullah qodiriy#central Asia#central asian literature#sam’s reading adventures#i am SOBBING

1 note

·

View note

Text

When earphones entangle in jhumke <<<<<<

#desicore#desi#desi struggles#desi academia#aesthetic#op#original post#nakhodeh#aayatunnisa#Indian academia#brown#brown mb#indian#india#pakistani#pakistan#South Asian art#central asian#south asian literature#south asian fashion#south asian aesthetic#south indian movies#asian

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

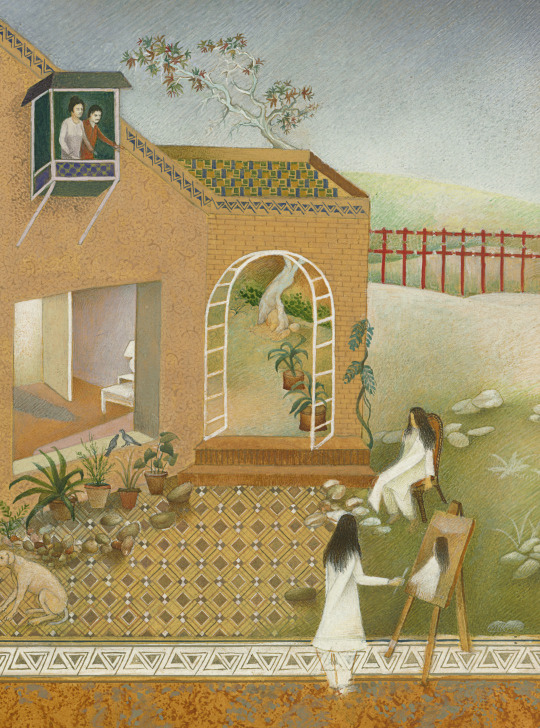

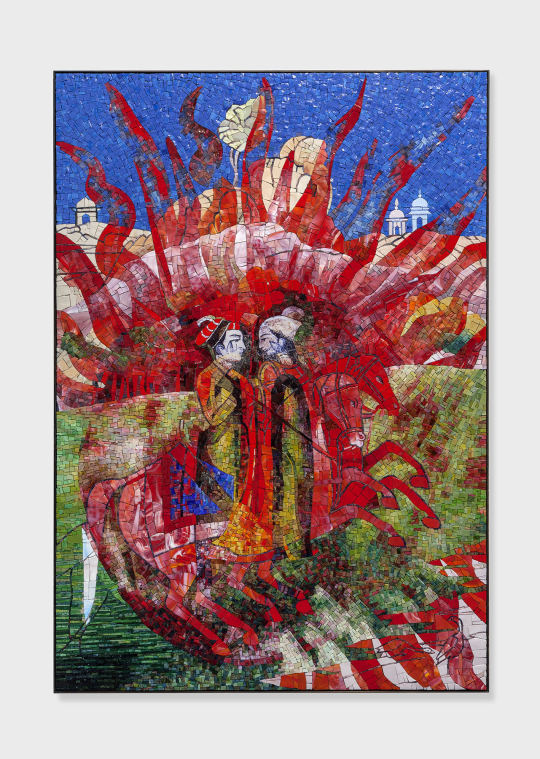

Discovering the Multifaceted World of Persian Art and its Significance – the 1001 Treasures

Discovering the Multifaceted World of Persian Art and its Significance – the 1001 Treasures

View On WordPress

#Archaeology#Architecture#Art#Asia#Asian Art#Asian Art Books#asian cultures#book#Central Asia#culture#decorative#Decorative Art#Eastern#ebook#fabric#frescoes#history#iconography#indian art#Iran#Islam#Islamic art#kindle book#Literature#middle ages#miniature#mosque#Museum#Ornaments#painting

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Literature produced in the ex-colonial countries but produced directly in languages which had been imported initially from Europe provides one kind of archive for the metropolitan university to construe the textual formation of ‘Third World Literature’; but this is not the only archive available, for the period after decolonization has also witnessed great expansion and consolidation of literary traditions in a number of indigenous languages as well [...] Not much of this kind of literature is directly available to the metropolitan literary theorists because, erudite as they usually are in metropolitan languages, hardly any of them has ever bothered with an Asian or African language. But parts and shades of these literatures also become available in the West, essentially in the following three ways. By far the greater part of the archive through which knowledge about the so-called Third World is generated in the metropolises has traditionally been, and continues to be, assembled within the metropolitan institutions of research and explication, which are characteristically administered and occupied by overwhelmingly Western personnel. Non-Western individuals have also been employed in these same institutions – more and more so during the more recent, post-colonial period, although still almost always in subordinate positions. The archive itself is dispersed through myriad academic disciplines and genres of writing – from philological reconstruction of the classics to lowbrow reports by missionaries and administrators; from Area Study Programmes and even the central fields of the Humanities to translation projects sponsored by Foundations and private publishing houses alike – generating all kinds of classificatory practices. A particularly large mechanism in the assembly of this archive has been the institutionalized symbiosis between the Western scholar and the local informant, which is frequently re-enacted now – no doubt in far more subtle ways –between the contemporary literary theorist of the West, who typically does not know a non-Western language, and the indigenous translator or essayist, who typically knows one or two. This older, multidisciplinary and somewhat chaotic archive is greatly expanded in our own time, especially in the area of literary studies, by a developing machinery of specifically literary translations – a machinery not nearly as highly developed as the one that exists for the circulation of texts among the metropolitan countries themselves, but not inconsiderable on its own terms. Apart from the private publishing houses and the university presses which may publish such translations of their own volition or under sponsorship programmes, there are state institutions such as the Sahitya Akademi in India, as well as international agencies such as UNESCO, not to speak of the American ‘philanthropic’foundations such as the Rockefeller-funded Asia Society, which have extensive programmes for such publications. Supplementing these translations are the critical essay and its associated genres, usually produced by an indigenous intellectual who reads the indigenous language but writes in one of the metropolitan ones. Some of this kind of writing becomes available in the metropolises, creating versions and shadows of texts produced in other spaces of the globe, but texts which frequently come with the authority of the indigenous informant.

Aijaz Ahmed, In Theory: Nations, Classes, Literatures

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is May 31, remembrance day for victims of repressions and acarcılıq, the famines of 1920-1921 and 1931-1933. The former saw a million Qazaqs perish, and the latter between 1.3 to 1.5 million. By 1939, Qazaqs had lost more than a quarter of their population in a decade.

Moreover, Qazaqstan had lost most of its intelligentsia due to political repressions. A short list under the link.

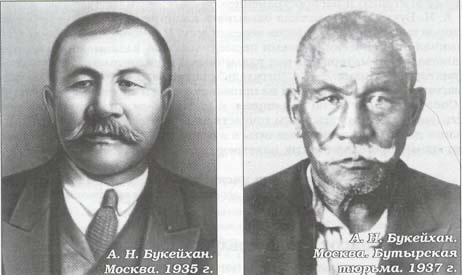

• Äliyhan Bökeyhan (1866-1937) — leader of the Alac Party and editor of the Qazaq newspaper, which ran from 1913 until 1918. He stood for an independent and democratic Qazaq state. In 1917, he was elected president of the newly-formed Alac Autonomy, but the republic was crushed in 1920 by the Bolsheviks. In 1937 he was arrested and executed in Moscow.

Bökeyhan in 1935 and 1937.

• Ahmet Baytursınulı (1872-1937) — linguist and author of the reformed Arabic alphabet called töte jazıw, which adapted the writing system to be more accessible and accounting for the Qazaq language's unique features. He is also responsible for coining new terms for Qazaq grammar and literature. In 1937 he was accused of being an "enemy of the people" and was shot by a firing squad.

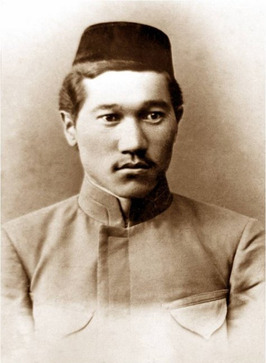

A. Baytursınulı in 1913.

Mirjaqıp Dulatulı (1885-1935) — poet and writer, author of the poem Oyan, Qazaq! (Wake up, Qazaq!) and the first Qazaq novel Baqıtsız Jamal (Unhappy Jamal), which brings to light the sad fate of women in patriarchal Qazaq society. The lines of Oyan, Qazaq! go thus:

Open your eyes; wake up, Qazaq; raise your head,

Don't waste your years in the darkness.

When the land is lost, faith corrupted, and the situation's getting worse,

My dear, there's no time to rest.

Oyan, Qazaq! has become a slogan for a free Qazaqstan in modern times.

M. Dulatulı in 1916.

In 1928 he was accused of "Qazaq nationalism" and was arrested. He spent two years in Butyrka prison, then was transferred to Solovki prison camp. He died in Sosnovka in 1935.

Turar Rısqulov (1894-1938) — chairman of the Central Electoral Committee of the Turkestan ASSR, founder of the "Bukhara" society, and participant in the 1916 Central Asian revolt. He supported the agency of indigenous Turkic peoples, viewing revolution along national lines as a fight against colonial exploitation and settler violence. He was charged with Pan-Turkism and was executed in 1938.

Portrait of T. Rısqulov.

İliyas Jansügirov (1894-1938) — poet, writer, and translator. He's the author of the famous poem Qulager about the death of Aqın-Seri's beloved horse; he also translated countless works of Pushkin, Gorky, Mayakovsky, Hugo, Heine, and other foreign classics. He was executed without trial in 1938.

İ. Jansügirov, presumably in the 1920s.

There were many more bright people who were imprisoned and executed by the Soviet regime, such as writers Mağjan Jumabay, Säken Seyfullin, Beyimbet Maylin; doctor Sanjar Asfendiyarov, linguists Qudaybergen Jubanov, Teljan Conanov, Näzir Törequlov.

The forced settlement of nomads led to Qazaqs being ripped away from their traditional life and culture, the mass repressions of the intelligentsia silenced people's voices. This day is as important as ever in light of the situation in Qazaqstan, where the government still imprisons journalists and activists; where the 200+ people killed during Bloody January and their families still haven't seen justice; and where, in the world, Russia denies Qazaqstan's history and territorial integrity, and still dreams of rebuilding the Russian Empire.

137 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is your opinion on the article "Mesopotamian or Iranian? A New Investigation on the Origin of the Goddess Anāhitā" by Alireza Qaderi?

He proposes that Anahita is possibly the syncretism of an Iranian Water goddess with Annunitum, and while it largely makes a lot of sense to me, especially with how it points out that we can't treat the Avesta as we know it as identical to the Avesta in Zarathustra's time,

it also assumes the Central Asian goddess Ardokhsho comes from Aredvi Sura instead of Arti, and everything else I've seen just says Ardokhsho comes from Arti, although I haven't seen much literature on either deity tbh

Sorry it took me a few days to answer this ask even though it’s basically laser focused on my interests. I had some other stuff to read and unpleasant work duties to perform and couldn’t properly go through the recommended paper.

My feelings about the paper are mixed. I think anyone who remembers Annunitum was a distinct deity as early as in the late third millennium BCE deserves at least some credit. The notion of interchangeability of goddesses still haunts the field, fueled by Bible scholars, Helsinki hyperdiffusionists and the like. Overall the author shines in the sections dedicated only to the evaluation of the broadly Iranian material, but as soon as the focus switches to Mesopotamia things fall apart, sadly.

More under the cut. Hope you don’t mind that I’ll also use this as an opportunity to talk about Annunitum in Sippar in general. I've been gathering sources to improve her wiki article further (don’t expect that any time soon though).

The Iranian material

Criticizing the vintage attempts at equating Anahita with Sarasvati is sound and sensible. Same with stressing that she is distinct from Nanaya and Oxus. The criticism of theories depending on lack of familiarity with the historical range of the beaver was a nice touch too, it demonstrates well that the author wanted to cover as much previous literature as possible. However, I also have no clue what’s up with “ΑΡΔΟΧΡΟ has an ambiguous relationship with Arədvī Sūrā”, I’ve also only ever seen this name explained as a derivative of Ashi/Arti save for a single paper trying to force a link to Oxus which was met with critical responses. It’s entirely possible this is an argument I simply haven’t seen though, I’m also not really familiar with this matter.

Overall the arguments against seeking Anahita’s origin in the east are perfectly sensible, and line up with the evidence well - no issues at all with this part of the paper. Following a more detailed list of Anahita’s easter attestations from Shenkar’s Intangible spirits and graven images. She appears on some Kushano-Sasanian coins, but this seems to reflect importing her from the west relatively late on since she appears in neither Kushan nor Bactrian sources. The coins are even exclusively inscribed in Middle Persian, with no trace of the local vernacular.

For unclear reasons Anahita caught on to a degree even further east in Sogdia, but attestations are limited to the period between fourth and sixth centuries. Since they’re largely just generic theophoric names, it is hard to call her anything but a minor deity of indeterminate character in this context, though. I’ve seen the argument that the popularity of Oxus in the east might have been the obstacle to introducing her. Oxus was a bigger deal in Bactria than in Sogdia so it could even explain why Sogdians were slightly more keen on her, arguably, even if they and Bactrians came into contact with her cult under similar circumstances.

Back to the article, the section dealing with the western attestations starts on a pretty strong note too. The need for reevaluation if it’s fair to talk about Achaemenid rulers as “Zoroastrian” is a mainstay of studies published over the past 10-15 years or so. I can’t weigh on the linguistic arguments because I know next to nothing about that.

I’m not sure if I follow the argument that it makes no sense Iranian population wouldn’t need a royal order to start worshipping a new deity as long as they were Iranian, tbh - linguistic or cultural affiliation doesn’t come prepackaged with automatically updated list of deities one is obliged to instantly adopt as soon as they pop up into existence. Following this logic, why didn’t Sargon’s Akkadian speaking subjects in Syria just adopt Ilaba before being obliged to do so? You will find literally hundreds of cases like this, it’s a very weird argument to me.

The Mesopotamian material

The biggest problems start once the coverage of Mesopotamia begins. The rigor evident in the strictly Iranian sections of the article just… vanishes and it’s incredibly weird.

Herodotus as a source is… quite something. The phrase “ a goddess with a Semitic character” is… well, quite something too (Reallexikon generally advises against defining anything but languages as “Semitic” in Mesopotamian context - Mesopotamian is a perfectly fine label to use, and accounts for the fact that Sumerian, Hurrian and Kassite are not a part of the Semitic language family). It keeps repeating later and admittedly I’m not very fond of this. Especially when it pertains to the west of Iran, where deities originating in Mesopotamia were worshiped since the late third millennium BCE - they were more Elamite than Mesopotamian by the time Persians showed up, really. The matter is covered in detail in Wouter Henkelman’s Other Gods who Are with Adad in the Persepolis Fortification Archive as a case study.

Cybele was by no means Mesopotamian (with each new study she keeps becoming more strictly Phrygian, with earlier Anatolian, let alone Mesopotamian, influence becoming less and less likely) so I'm not sure what she's doing here, Nanaya’s associations with lions is almost definitely an Iranian innovation and not attested before the late first millennium BCE; despite earlier sound arguments against ascribing strictly Avestan Zoroastrian sensibilities to people in the late first millennium BCE, that’s basically what happens here. Lions were evidently viewed favorably by at least some Persians and especially Bactrians and Sogdians.

The less said about the part trying to link evidence from Palmyra to Inanna and Dumuzi (what does a marginal spouse deity like Dumuzi, entirely absent from Palmyra, have to do with Sabazius, a veritable pantheon head equated with Zeus?), the better. Frazerian bit, if I have to be honest.

I’m not sure about the enthusiasm for Boyce’s argument that it makes little sense for Anahita to simultaneously be a river goddess and to bestow victory in battle. The latter characteristic lines up well with her elevation to the position of a deity tied to investiture of kings, which in turn is something which boils down to personal preference of a given dynasty. The character of deities isn’t necessarily supposed to be one-dimensional and having distinct spheres of activity because of historical factors is hardly unusual.

Stressing that it’s not possible to treat Anahita and Ishtar as interchangeable is commendable. However, I don’t think it’s possible to claim continuity between the religious beliefs reflected in the relief of Anubanini and first millennium BCE Media. The argument is not pursued further, to be fair, but it’s still weird.

The next huge issue is the treatment of the late “Anu theology”. A good recent overview of this matter can be found in Krul’s 2018 monograph (shared by the author herself here).

For starters, it’s completely baffling to declare Anu had no spouse at first; Urash and Ki are both attested in the Early Dynastic period already - and the former appears reasonably commonly in this role in literary texts and god lists. Even Antu might already be present in the Abu Salabikh list.

Attributing Inanna prominence in Uruk and in the Eanna in particular to identification with Antu is utterly nightmarish and one of the worst Inanna takes I’ve ever seen; the fact it’s contradicted by information of the same page makes it pretty funny, admittedly. Inanna’s ties to the city go back literally to the beginning of recorded history (some of the oldest texts in the world are demands aimed at cities under the control of Uruk to provide offerings for Inanna ffs), and probably even further back. Meanwhile, Anu for most of his history was an abstract hardly worshiped deity; Krul stresses this in the beginning of her book linked above. I’m not a fan of ancient matriarchy takes which are often lurking in the background when the cases of earliest city goddesses like Inanna, Nisaba and Nanshe are discussed but I do think the need to downplay Inanna’s prominence and elevate Anu which pops up every few years in scholarship is suspect and probably motivated by sexism, consciously or not, tbh.

Trying to make the “Anu theology” which developed in the late first millennium BCE an influence on the entirety of Mesopotamia and beyond is puzzling. Sabazius appearing in Palmyra with a spouse is tied to Anu, somehow? The fact that deities had spouses is? Atargatis ties into this somehow? I’m sorry, but I’m not following. Also, Uruk was no longer a theological center of the Mesopotamian world in the first millennium BCE. Babylon was, and before that Nippur. There is no need to speculate, there are thousands of texts to back it up. The late sources from Uruk in particular show that Babylon was somewhat forcefully influencing the city, not the other way around.

The Anu theology was a display of local “nationalism” of Uruk and had a very limited impact. There is evidence for some degree of late theological cooperation between Uruk and Nippur, and possibly Der as well (Der itself despite being located with certainty has yet to be excavated, though, so caution is necessary), but nothing of this sort is to be found in the late sources from other locations.

Annunitum = Anahita?

Finally, let’s look at the core idea behind the article.

Right off the bat I feel it’s necessary to stress Annunitum generally wasn’t regarded as an astral deity. In the Old Babylonian period, the Venus role was evidently handled by Ninsianna in Sippar; later on they aren’t even attested there but the regular Ishtar is. Seems doubtful it would actually be Annunitum who got to be an astral deity there at any point in time.

This claim is also highly dubious. There is no evidence that Antu was ever worshiped in Sippar, let alone that she was equated there with Annunitum; she doesn’t show up at all in Jennie Myers’ 2002 thesis The Sippar pantheon: a diachronic study. Paul-Alain Beaulieu stresses her lack of importance all across Mesopotamia save for first millennium BCE Uruk here. There is also no evidence that the late Anu theology impacted Sippar in any capacity. Shamash retained his position in the city until the death of cuneiform. Even in Uruk, Annunitum in the late sources appears only in association with Ishtar and Nanaya, not Anu and Antu. I will repeat how I feel about the need to assert Anu’s importance where there is no trace of it.

Overall it feels like unrelated Mesopotamian and adjacent sources from different areas and time periods are used indiscriminately; which is ironically the criticism employed in the article wrt the treatment of Iranian textual sources by other researchers.

The Assyriological sources employed leave a bit to be desired, too. In particular Abusch’s Ishtar entry in the Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible is a nightmare (he’s good when he covers incantations but his broader “theological” proposals are… quite something), here are some quotes from it to show how awful it is is a central point of reference:

Of the other authors cited, Jacobsen is Jacobsen and a lot changed since the 1960s. Roberts was criticized right after his study was published by researchers like Aage Westenholz. Langdon’s study from the early 1900s is an outdated nightmare, I guess we know what’s up with the Dumuzi hot takes now. Beaulieu is great but his papers and monographs aren’t really utilized to any meaningful extent, I feel.

Other criticisms aside, I’m unsure if Annunitum was important enough in the fifth century BCE to be noticed by Artaxerxes II as postulated here, especially since Shamash was right next door and definitely retained some degree of prominence. Most if not all cases of Mesopotamian deities influencing Persian or broader Iranian tradition reflect widespread cults of popular deities - Nanaya, Nabu (via influence on Tishtrya), Nergal (in the west, around Harran) - as opposed to a b-list strictly local deity. And it’s really hard to refer to Annunitum differently. Let’s take a quick look at her position in the twin cities of Sippar - as far as I am aware, the most recent treatment of this matter is still Myers’ thesis, and that’s what I will rely on here.

Annunitum is first attested in Sippar in the Old Babylonian period, during the reign of Sabium, though as a deity already locally major enough to appear in an oath formula alongside Shamash. In the Early Dynastic period Sippar-Amnanum was likely associated with an enigmatic figure designated by the logogram ÉREN+X who doesn’t seem to be related to her. When and how exactly the tutelary deity change occurred is not presently possible to determine and admittedly of no real relevance here.

Evidently Annunitum’s cult in Sippar was influenced to some degree by the Sargonic tradition she originated in, her temple was even called Eulmaš just like that in Akkad. It’s not impossible it was even originally founded by one of the members of the Sargonic dynasty, but in absence of pre-OB evidence caution is necessary. There is no shortage of later rulers who wanted to partake in the Sargonic legacy, after all. By the earliest documented times, it was the second most important temple in the Sippar agglomeration, and the only one beside the Ebabbar to have its own administrative structure.

Annunitum was even referred to as the “queen of Sippar” (Šarrat Sippar; note that by the Neo-Babylonian period this title came to function as a distinct goddess, though). In Sippar-Amnanum there was a street, a gate and a canal named after her. A bit over 6% of the inhabitants of both cities bore theophoric names invoking her, also.

Sippar-Amnanum was abandoned for some 200 years after the reign of Ammi-saduqa, but it seems the clergy simply moved to the other Sippar next door. Next few centuries are very sparsely documented at this site, but supposedly Shagarakti-Shuriash rebuilt Annunitum’s temple (the matter is discussed in detail here).

Inscriptions of Tiglath-pileser I dealing with the conquest of northern Babylonia affirm that Annunitum continued to be viewed as the goddess of Sippar through the Neo-Assyrian period. According to an inscription of Nabonidus her temple, and Sippar-Amnanum as a whole, were razed by Sennacherib (he also blames “Gutians” for it though by then this is a label as generic as “barbarian”). This might be why her cult had to be relocated to the other part of Sippar again. In the Neo-Babylonian period it returned to Sippar-Amnanum under Neriglissar, though her temple was only rebuilt by Nabonidus. It survived at least until the reign of Darius, though it was only a small sanctuary (É.KUR.RA.MEŠ) like those of Adad and Gula.

There is very little evidence for popular worship of her so late on: only two theophoric names have been identified…. For comparison, Shamash appears in 208 (out of 823 theophoric names, out of a total of 1243 total). Nergal, Gula, Adad and even Amurru are all more common. Aya is also absent, but unlike Annunitum despite her prominence in earlier periods she was actually never common in theophoric names, save for the names of naditu; and naditu ceased to be a thing after the OB period.

Offering lists complicate the matter further. From the reign of Nebuchadnezzar, Annunitum started to lose ground to a duo introduced from Dur-Kurigalzu: a manifestation of Nanaya associated with this city and Ishtar-tashme. Why they suddenly appeared in Sippar and why they overshadowed Annunitum is uncertain, perhaps Dur-Kurigalzu just failed to recover from decline after the end of the Kassite period and eventually the decision was made to start transferring local deities to other nearby major urban centers. The process reversed during the reign of Nabonidus, who ordered an increase in offerings made to her. This might’ve been motivated by his general concern for Sin and any deities considered members of his immediate family - essentially, a display of personal devotion. This elevation is still evident in offering lists from the reign of Cyrus, though.

Overall the paper is quite convincing - outstanding, even - when it comes to the Iranian material alone, and between mediocre and nightmarish once the author shifts to Mesopotamia.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

feeling enthusiastic tonight so i wanted to talk about my favourite things about the languages i speak/am studying!

mandarin chinese:

singular character words are fairly rare! unlike english, due to the high number of homophones in the spoken language, most words are comprised of two or more characters for clarity's sake. for example, while 孩 does by itself mean child, usually it's combined with another character (ie 孩子,小孩儿,etc.) due to it sounding similar to other words (还,骸).

in spoken language, you often need the entire context to understand the meaning. due to homophones, if you're missing the surrounding context, then it can be easy to misunderstand what someone's saying.

homophones generally! i've been known to love a good tongue-twister, and being a native chinese speaker is definitely part of that—there's just so many good ones! this also crops up in social media/memes, where a homophone is substituted for the original character(s).

the written language! i'm definitely more biased towards simplified chinese, but i can still read traditional chinese, and i think chinese is one of the most beautifully-written languages. it's just so logical! the strokes follow a certain order, and everything is contained in "boxed" that are very pleasing.

german:

poetry! german is known for literature, and i love reading poetry in german, even if not having studied it in a while means i have to look things up pretty frequenty ^^°°

the pronunciation! while i'm definitely at an advantage since i have an ear for languages and can nail german pronunciation at a natural level, i love speaking german—especially the longer words! i love the way the letters sound together (i'm definitely biased towards the eu/äu combination haha).

the ß!

gothic script—this appears a lot in historical german print, and i love it, even if it does make it a bit of a challenge to read anything haha.

kurmanji:

the various possessiveness contructions—there is no verb corresponding to the english to have, so instead you have to use the verb hebûn, to exist, so for example, two brothers of me exist (du birayên min hene, using the izafe construction) or for me two brothers exist (min du bira hene, without izafe, possessor is in the oblique case at the start of the clause) would be used instead of "i have two brothers".

the xw dipthong—i'm probably biased because i love "uncommon" sounds and letter combinations, but not only does the x in kurmanji sound nice (it's sort of like the ch in bach, or the ch in loch), when combined with the w it makes a sort of hissing sound which i'm very partially to.

mongolian:

sounds absolutely gorgeous!! central asian languages generally sound very pleasing to me, but i especially love the guttural sounds in mongolian.

the traditional script is one of the most beautiful things i've ever seen. i have yet to learn how to write in it (at least without a lot of tears on my part), but there's a user on xhs that writes in traditional script, and it's just. stunning. it's fluid, and curling, and just! aaaa!!! i love it. also it's written vertically, which is a fairly uncommon thing as far as languages go.

it's got a ton of different dialects! i'm a known enjoyer of dialects and regional language variations, so of course this is like a goldmine to me.

korean:

i know i said that the mongolian script is gorgeous, but look, i love writing systems in general, and korean is just. so orderly! so perfect for my pattern-obsessed little mind! also, it only takes, like, half an hour to memorise. 12/10 i love it.

a very specific point, but the various ways to say goodbye! you specify whether the person you're speaking to are staying or leaving.

turkish:

probably the most agglutinative language i'm aware of—a lot of words, especially more "modern" (ie new) words are formed by taking a base word and then adding on "meaning" or semantics to it, for example the word for a shoe cabinet is literally "that which stores the covers for the feet".

neutral pronouns! spoken mandarin is also neutral in pronouns, but in turkish both the written and spoken form of the third person pronoun is neutral. while it does make it a little bit frustrating if you're trying to, say, discuss feminist theory, it does mean that no gendered assumptions are made about, for example, a job position.

that's all i can think of right now! if anyone else wants to ramble excitedly about the languages they're studying/speak, please feel free to add on!

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reference to Alexander the Great, his General, Antigonus, and the Battle of Gabiene.

The "Treasures of the Aegean Sea" tells the saga of a family of Western arcanists whose journey spans thousands of miles and over two millennia. Their ancestors fought alongside a Macedonian God-King (possibly Alexander the Great), shifting their loyalties after his death to the one-eyed general (possibly Antigonus). These war-hardened veterans joined his army after the Battle of Gabiene and formed a powerful but volatile force.

The arcanists within this army were eventually sent east, where they blended into the Sogdian tribes and thrived along the Central Asian trade routes. Over time, they settled near the ancient Hellenistic city of Ai-Khanoum, establishing a small arcanist commune. However, the turbulence of early conflicts eventually scattered them once again, leaving behind only fragments of their story—maps, diaries, epitaphs, and archives that tell the tale of their incredible adventure.

Alexander the Great (356–323 BC), king of Macedon, succeeded his father Philip II at age 20 and embarked on a decade-long military campaign, creating one of the largest empires in history, stretching from Greece to India. Undefeated in battle, he conquered the Achaemenid Persian Empire and expanded Macedonian control across Western and Central Asia, Egypt, and parts of South Asia. After defeating Indian king Porus, Alexander’s army refused to advance further, leading him to turn back. He died in 323 BC in Babylon. His conquests spread Greek culture widely, marking the start of the Hellenistic period. Alexander’s military legacy influenced later leaders and became legendary, inspiring literature across many cultures. source

Antigonus I Monophthalmus aka "Antigonus the One-Eyed"; 382 – 301 BC) was a Macedonian general and a key successor to Alexander the Great. After serving in Alexander's army, he became satrap of Phrygia and later assumed control over large parts of Alexander’s former empire. He declared himself king (basileus) in 306 BC and founded the Antigonid dynasty. Following a series of wars among Alexander’s successors, Antigonus became one of the most powerful Diadochi, ruling over Greece, Asia Minor, and parts of the Near East. However, he was defeated and killed at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC, leading to the division of his kingdom. His son Demetrius later took control of Macedonia. source

Gabiene: After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, his generals immediately began squabbling over his empire. Soon it degenerated into open warfare, with each general attempting to claim a portion of Alexander's vast kingdom. One of the most talented generals among the Diadochi was Antigonus Monophthalmus (Antigonus the One-eyed), so called because of an eye he lost in a siege. During the early years of warfare between the Successors, he faced Eumenes, a capable general who had already crushed Craterus. The two Diadochi fought a series of actions across Asia Minor, and Persia and Media before finally meeting in what was to be a decisive battle at Gabiene (Greek: Γαβιηνή). source

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I’m interested in reading Uzbek literature and just came across an old post of yours, so I hope it’s okay I’m barging into your ask box to ask questions! 😅 I coincidentally went to two museum exhibitions in Paris about Uzbekistan, and now I need to Read Books About It. I am particularly interested in anything pre-1920s, and I came across Days Gone By by Abdulla Qodiriy. I struggled to find a comprehensive summary that didn’t spoil the story, so I wanted to ask if it’s a good book that depicts pre-Russian (or at least pre-Stalinist) Uzbek culture? I would be super grateful for any other recommendations. Did Hamid Ismailov write anything that’s set pre 1920s? Anyway, please feel free to only answer as much or as little as you’re in the mood for, sorry to bother you!! 💕

Oh wow thank you so much for this ask! I love talking about Central Asian literature. I will confess that most of the books I've read so far deal with Central Asian life either during or after the Soviet Union and that is a bias reflective of my time period of interest (Central Asia during WWI and the Russian Civil War) and the fact that I only read and speak English and most of the books translated into English are either Soviet or post-Soviet literature. So my recommends are in no way exhaustive, but they should be a good place to start your journey.

The first book I'd recommend is Days Gone By by Abdulla Qodiriy. it's set in the 1800s, so the Russians haven't fully colonized the region yet, but they have taken a lot of land in the Steppe and relations with the khans are growing tense. It takes place in Turkestan and is about Atabek, a wealthy merchant, and the love of his life, Kumush, and the many struggles they face to be together. It's a fascinating read as it gives great insight into life before 1920 and how the Jadid's felt about women's rights and issues. I'm not sure what is your preferred language, but there are two English translations. One by Carol Ermakova, which is the one I read and enjoyed and one by Mark Reese, which I haven't read yet, but I got to speak to him about translating the book and I really liked his passion for the story and Central Asia.

The other book I'd recommend is Night by Cho'lpon (which I actually like better than Days Gone By, but don't tell anyone ;)). It's set in the 1900s, so much later than Days Gone By, but before the Russian Revolution or WWI. It's about a young woman who is married to an official who is also a sexual glutton and the chaos it causes in his household. Even though it is a Tsarist Central Asia, the focus is on the Central Asian people and life in Central Asia and again it provides an interesting look at how the Jadids felt about women's rights and the issues they faced (and Cho'lpon gets to poke some fun at the Jadids themselves which is fascinating). Christopher Fort did a masterful job with the translation and provided an phenomenal introduction that explores Cho'lpon's life and provides a great analysis of the novel itself.

If you like poetry, I'd also recommend the book 12 Ghazals by Alisher Navoiy and 14 Poems by Abdulhamid Cho'lpon. The poems were translated by Andrew Staniland, Aidakhon Bumatova, and Avazkhon Khaydarov. Navoiy was a poet who write in the 1400s and is considered a father of Central Asian poetry. Cho'lpon, of course, is the father of modern Central Asian poetry.

Actually, Staniland just came out with another poetry collection I haven't read it (but i've just ordered it). It's called Nodira and Uvaysiy: Selected Poems. Nodira was a Central Asian Queen in the 1800s famous for her poetry and Uvaysiy was a woman poet who lived in the palace with Nodira.

For a more contemporary writer, Hamid Ismailov wrote two books that deal with multiple timelines, including a pre-1920 Central Asia. The first book of his I'd recommend is one of my favorites. It's called The Devils' Dance and it is about the last days of Abdulla Qodiriy, Cho'lpon, and Abdurauf Fitrat, as well as Central Asia during the Great Game. It follows the fate of Emir Nasrullah and Madali's Khanates as the Russians and British start to infiltrate the region (the connection between the two story lines is that Qodiriy, in real life and in Hamid's book, was working on a novel about Madali's wife: Oyxon before Qodiriy was arrested and murdered by the Soviets). Actually, Nodira and Uvaysiy, who I mentioned above, play a prominent role in this book as well.

Hamid also wrote a book called Of Strangers and Bees. it's about a modern day Central Asian expat and his connection with a charming bee and the famous physician Ibn Sina. It jumps from the 1000s Central Asia with Ibn Sina and modern day with the expat. I'll admit I've had to reread this book many times because it borrows heavily from Sufism and there are a lot of references that I'm still trying to catch and understand simply because I'm not as familiar with Sufism as I'd like to be.